Abstract

The presence of Escherichia coli isolates in the environment is a potential source of contamination of food and water supplies. Moreover, these isolates may harbor virulence genes that can be a source of new forms of pathogenic strains. Here, using multiplex PCR, we examined the presence of virulence gene markers (stx1, stx2, eaeA, hlyA) in 1,698 environmental isolates of E. coli and 81 isolates from food and clinical sources. The PCR analysis showed that ∼5% (79 of 1,698) of the total environmental isolates and 96% (79 of 81) of the food and clinical isolates were positive for at least one of the genes. Of the food and clinical isolates, 84% (68 of 81 isolates) were positive for all four genes. Of the subset of environmental isolates chosen for further analysis, 16% (13 of 79 isolates) were positive for stx2 and 84% (66 of 79 isolates) were positive for eaeA; 16 of the latter strains were also positive for hlyA. The pathogenic potentials of 174 isolates (81 isolates from food and clinical sources and 93 isolates from environmental sources) were tested by using a cytotoxicity assay based on lactate dehydrogenase release from Vero cells. In general, 97% (79 of 81) of the food and clinical isolates and 41% (39 of 93) of the environmental isolates exhibited positive cytotoxicity. High cytotoxicity values correlated to the presence of stx genes. The majority of hly-positive but stx-negative environmental isolates also exhibited a certain degree of cytotoxicity. Isolates were also tested for sorbitol utilization and were genotyped by ribotyping and by repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (REP-PCR) as potential means of quickly identifying virulent strains from the environment, but none of these methods could be used to distinguish cytotoxic environmental isolates. Only 31% of the isolates were negative for sorbitol fermentation, and none of the isolates had common ribotypes or REP-PCR fingerprints. This study suggests that overall higher cytotoxicity values correlated with the production of stx genes, and the majority of hly-positive but stx-negative environmental isolates also exhibited a certain degree of cytotoxicity. This study demonstrated that there is widespread distribution of potentially virulent E. coli strains in the environment that may be a cause of concern for human health.

Escherichia coli is naturally present in the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and animals as part of the natural microflora. Some strains, however, are able to cause disease. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), also known as Shiga-toxin producing E. coli (STEC), is a group of well-recognized pathogens that are responsible for serious human infections like hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (26, 29). Serotype O157:H7 is the EHEC group that has been most frequently implicated in food-borne outbreaks worldwide (28). Production of Shiga toxins (encoded by the stx1 and stx2 genes) is a key feature of most EHEC (3). Other virulence-associated factors include a pO157 plasmid, which encodes hemolysin (hlyA) (42), and the enterocyte effacement locus containing the intimin gene (eaeA) (28). Cattle serve as a main reservoir for E. coli O157:H7 strains (10, 20, 38). Other nonbovine species, such as horses, dogs, birds, and flies, and even water have also been reported to be sources of these organisms (20). It is believed that shedding of the microorganisms into the environment may represent a direct link between food and water contamination and human infections (37).

The presence of pathogenic E. coli in the food and water supply is a significant public health concern. Transmission of virulence elements among E. coli strains contributes to their pathogenicity and increased diversity (14). Therefore, certain isolates can harbor a specific group of virulent genes that make them particularly dangerous to humans. Likewise, other strains may be reservoirs of a combination of virulence factors that do not belong to a specific pathotype (25). There are numerous methods for subtyping E. coli. These methods are useful for identification and tracking E. coli O157:H7 and other E. coli strains from different sources (19, 35); however, they do not assess the pathogenic potential of the strains. Research has shown that the prevalence of potentially virulent E. coli strains or their associated genes may in the environment may be greater than previously realized (9-11). However, none of these studies tested the virulence potential of environmental bacteria carrying these genes.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence of potentially virulent STEC environmental isolates in different animal and sewage sources (16). Potential STEC isolates were first identified by multiplex PCR of the stx1, stx2, hly, and eae genes. Then a previously described, modified, faster version of the traditional Vero cell assay (40) was used to assess the virulence potential of putative STEC strains. This cytotoxicity test was based on the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from Vero cells. Comparisons were made to O157:H7 isolates from food and clinical sources. Ribotyping and a genetic fingerprinting method, repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (REP-PCR) (12, 34), were tested to establish a possible correlation between genotypic and phenotypic virulence properties in order to develop an alternative means of rapidly identifying potentially virulent E. coli from the environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

A total of 1,698 environmental strains of E. coli were isolated from 100 individual animal feces or sewage samples in Indiana (16). From 10 to 15 isolates were taken from individual hosts, and up to 50 isolates were taken from composite samples (e.g., sewage). The sources of the isolates were as follows: 526 isolates from 11 cows, 214 isolates from 15 pigs, 372 isolates from 25 poultry, 275 isolates from 32 wildlife, 205 isolates from five sewage samples, 62 isolates from five humans, and 44 isolates from seven domestic animals (16). Isolates were identified as E. coli by selection on eosin methylene blue agar (Difco), and identities were confirmed by the citrate test (21). A subset of 93 environmental isolates was used for the cytotoxic potential analysis portion of this study (Table 1). This subset included 79 isolates from this study and an additional 14 environmental isolates from a previous study (19). Of these 93 isolates, 87 were positive for at least one toxin gene, and the remaining 6 were randomly picked to serve as controls (Table 1). Eighty-four E. coli strains with known serotypes, isolated from food or clinical sources, were kindly provided by other researchers or were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.) (Table 2). All isolates were maintained as 10% glycerol stock preparations at −80°C. For experimental purposes, isolates were grown in 5 ml of brain heart infusion (BHI) broth overnight at 37°C and were maintained in BHI soft agar in glass vials at 4°C. Bacterial strains (n = 174) were streaked onto sorbitol MacConkey agar (Difco) plates to determine their ability to ferment sorbitol (Tables 1 and 2). After 14 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were examined for the presence of colorless (sorbitol-negative) or pink (sorbitol-positive) colonies.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of and cytotoxicity assay for environmental E. coli isolates

| Isolate(s) | Source | Sorbitol utilization | Ribotype (DUP label) | Presence of virulence genesa

|

Cytotoxicity

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 | stx2 | eaeA | hlyA | LDH (A490/655)b | %b | ||||

| F59c | Pig | + | 3036 | − | − | − | − | 0.08 ± 0.009 | −1 |

| F103c | Pig | + | 14217 | − | − | − | − | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 4 |

| F104c | Pig | + | 3003 | − | − | + | − | 0.07 ± 0.006 | 4 |

| F105c | Pig | + | 14215 | − | − | + | − | 0.08 ± 0.02 | −0.2 |

| F109c | Pig | + | 14217 | − | − | + | − | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 3 |

| F112c | Pig | + | 3015 | − | − | + | − | 0.07 ± 0.006 | −11 |

| F116c | Pig | + | 14147 | − | − | − | − | 0.08 ± 0.02 | −2 |

| F138-F172d | Pig (28 isolates) | + | 3021 | − | − | + | − | 0.07 ± 0.007 | 0-2 |

| F182 | Pig | − | NTf | − | + | − | − | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 42 |

| F183 | Pig | − | 15004 | − | + | − | − | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 76 |

| F188 | Pig | − | NT | − | + | − | − | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 38 |

| F189 | Pig | − | NT | + | − | − | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 16 | |

| F190 | Pig | − | NT | − | + | − | − | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 49 |

| F192 | Pig | − | NT | − | + | − | − | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 56 |

| F193 | Pig | − | NT | − | + | − | − | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 38 |

| F197 | Pig | − | NT | − | + | − | − | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 27 |

| F208 | Pig | − | NT | − | + | − | − | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 48 |

| F214 | Pig | + | 3011 | − | − | + | − | 0.06 ± 0.008 | −3 |

| F219 | Pig | + | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0 |

| F220 | Pig | + | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 2 |

| F227 | Pig | + | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 2 |

| F228 | Pig | − | 15004 | − | + | − | − | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 80 |

| F52c | Cow | + | 3015 | − | − | − | − | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 6 |

| F117c | Cow | + | 3015 | − | − | + | − | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.9 |

| F121c | Cow | + | 3021 | − | − | − | − | 0.07 ± 0.02 | −7 |

| F241 | Cow | + | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.08 ± 0.003 | −10 |

| F246 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 21 |

| F249 | Cow | + | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.09 ± 0.005 | −7 |

| F250 | Cow | + | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.09 ± 0.008 | −8 |

| F446 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.11 ± 0.01 | −2 |

| F447 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 8 |

| F448 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 9 |

| F449 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.11 ± 0.02 | −1 |

| F450 | Cow | − | 15105 | − | − | + | + | 0.1 ± 0.007 | −6 |

| F451 | Cow | − | 14147 | − | − | + | + | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 40 |

| F452 | Cow | − | 14147 | − | − | + | + | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 32 |

| F453 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 21 |

| F454 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 29 |

| F455 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 3 |

| F456 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 14 |

| F457 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 22 |

| F458 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 21 |

| F459 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 6 |

| F460 | Cow | − | NT | − | − | + | + | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 2 |

| F684 | Cow | + | 14157 | − | + | − | − | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 38 |

| F759 | Cow | − | 14157 | − | − | + | + | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 29 |

| W0375-W0389e | Cat (9 isolates) | + | 14009 | − | − | + | − | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0 |

| W0378 | Cat | + | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.26 ± 0.11 | 30 |

| F110c | Dog | + | 3015 | − | − | + | − | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.2 |

| W0061 | Deer | + | 3049 | − | + | − | − | 0.57 ± 0.03 | 111 |

| W0106 | Chipmunk | + | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 3 |

| W0108 | Chipmunk | + | 15106 | − | − | + | − | 0.09 ± 0.004 | −15 |

| W0134 | Raccoon | + | NT | − | − | + | − | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 9 |

| W0 135 | Raccoon | + | 14029 | − | − | + | − | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 29 |

| F113c | Sewage | + | 14183 | − | − | − | − | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 19 |

| F114c | Sewage | + | 14141 | − | − | + | − | 0.08 ± 0.01 | −3 |

| F115c | Sewage | + | 3015 | − | − | + | − | 0.07 ± 0.01 | −3 |

| W0331 | Sewage | + | 13803 | − | + | − | − | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 0 |

Virulence genes were detected by PCR. stx, Shiga-like toxin gene; eaeA, intimin gene; hlyA, enterohemorrhagic E. coli hemolysin gene.

The LDH values are averages ± standard deviations for six replicates, where percent cytotoxicity = (Aexp − AEDL933)/(AEDL933 − AK12) × 100.

Isolates previously studied by Hahm et al. (19).

Only F138 was ribotyped as DUP 3021.

Only W389 was ribotyped as DUP 14009.

NT, not tested.

TABLE 2.

Characterization of and cytotoxicity assay for enterohemorrhagic E. coli from food and clinical sources

| Isolatea | Serotype | Sorbitol utilization | Ribotype (DUP label) | Presence of virulence genesb

|

Cytotoxicity

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 | stx2 | eaeA | hlyA | LDH (A490/655)c | %d | ||||

| Outbreak-related or clinical isolates | |||||||||

| HSC27 | O111:H8 | + | 3006 | + | + | + | + | 0.37 ± 0.008 | 86 |

| HSC23 | O91:H21 | + | 3006 | − | + | − | + | 0.27 ± 0.008 | 94 |

| 6363 | O157:H7 | − | NTe | + | + | + | + | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 149 |

| 6364 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 131 |

| 6362 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.23 ± 0.007 | 77 |

| 6361 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 125 |

| 6458 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.36 ± 0.007 | 156 |

| 6460 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.32 ± 0.19 | 50 |

| 13B69 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 129 |

| 13B70 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 129 |

| 13B72 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 157 |

| 13B88 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 53 |

| 13B89 | O157:H7 | − | 3064f | + | + | + | + | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 48 |

| 13B66 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 93 |

| 13B65 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 75 |

| 13A40 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 118 |

| 13A42 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.37 ± 0.003 | 84 |

| 6393 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 55 |

| 6394 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.42 ± 0.18 | 70 |

| 6395 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 23 |

| G5295 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | − | + | + | + | 0.28 ± 0.003 | 45 |

| ATCC43895 (EDL933 P-) | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | − | 0.53 ± 0.06 | 68 |

| B1409-C1 | O157:H7 | − | NT | − | + | + | + | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 2 |

| Non-outbreak-related isolates | |||||||||

| DUP101 (control) | ATCC 51739 | + | 3036 | − | − | − | − | 0.12 ± 0.005 | 1 |

| 488 | O157:NM | − | 3064 | − | + | + | + | 0.16 ± 0.003 | 40 |

| 489 | O157:H12 | + | 3002 | − | − | − | − | 0.06 ± 0.001 | −9 |

| 490 | O157:H19 | + | 3010 | − | − | − | − | 0.09 ± 0.008 | −3 |

| 1880 | O55:H7 | + | 3064 | − | − | + | − | 0.09 ± 0.01 | −2 |

| HAL EC91011 | O111:H11 | − | 3021 | + | − | + | + | 0.38 ± 0.09 | 88 |

| ATCC 43890 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | − | + | + | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 36 |

| 204P | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 74 |

| N396-2-2 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 107 |

| N317-3-1 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.35 ± 0.003 | 79 |

| N996-2-1 | O157:H7 | − | NT | − | + | + | + | 0.34 ± 0.006 | 147 |

| N931-5-1 | O157:H7 | − | NT | − | + | + | + | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 107 |

| N192-5-1 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 95 |

| N1014-7-1 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.27 ± 0.006 | 99 |

| 726 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 86 |

| 301C | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 86 |

| 505B | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 107 |

| PT23 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 198 |

| SEA13A45 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.13 ± 0.009 | 6 |

| SEA13A39 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 128 |

| SEA13A15 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 141 |

| SEA13A53 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 15 |

| SEA13A44 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.31 ± 0.121 | 47 |

| SEA13A16 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | − | + | + | + | 0.14 ± 0.008 | 8 |

| SEA13A72 | O157:H7 | − | NT | − | + | + | + | 0.31 ± 0.10 | 33 |

| SEA13A73 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.24 ± 0.003 | 19 |

| K1 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 215 |

| K3 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 183 |

| K4 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.10 ± 0.04 | −8 |

| K5 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 56 |

| K6 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 46 |

| K7 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.42 ± 0.004 | 310 |

| K8 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.20 ± 0.004 | 82 |

| K10 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.20 ± 0.009 | 85 |

| O1 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 77 |

| O2 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 64 |

| O3 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 71 |

| O4 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 128 |

| O5 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 72 |

| O6 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 90 |

| O7 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.3 ± 0.05 | 80 |

| O8 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 66 |

| O9 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 89 |

| O10 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 65 |

| O11 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.31 ± 0.007 | 84 |

| O12 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.28 ± 0.008 | 73 |

| O13 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 70 |

| O14 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 80 |

| O15 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 53 |

| P1 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 68 |

| P2 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 35 |

| P3 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.22 ± 0.007 | 53 |

| P4 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.083 ± 0.01 | 9 |

| P5 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 7 |

| P6 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 7 |

| Q2 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 118 |

| Q3 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 94 |

| Q4 | O157:H7 | − | NT | + | + | + | + | 0.07 ± 0.009 | 4 |

| Q6 | O157:H7 | − | 3064 | + | + | + | + | 0.08 ± 0.009 | 10 |

Cultures were provided by B. Blais, Agri-Food Canada; R. Johnson, Health of Animals Laboratory, Canada; D. Conner, Auburn University, and J. Johnson, Food and Drug Administration, Seattle, Wash.; P. Fratamico, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Eastern Regional Research Center, Philadelphia, Pa.; S. Weagant, Food and Drug Administration Laboratory, Bothel, Wash.; R. Sanderson, Indiana State Department of Health, Indianapolis; National Veterinary State Laboratory, Ames, Iowa; and Leonard L. Williams, Alabama A&M University, Normal.

Virulence genes were detected by PCR. stx, Shiga-like toxin gene; eaeA, intimin gene; hlyA, enterohemorrhagic E. coli hemolysin gene.

The LDH values are averages ± standard deviations for one or two representative experiments performed in triplicate.

Percent cytotoxicity = (Aexp − AEDL933)/(AEDL933 − AK12) × 100.

NT, not tested.

DUP 3064 is E. coli O157:H7.

Multiplex PCR.

E. coli isolates were screened for the presence of the virulence genes stx1, stx2, eaeA, and hlyA. Template DNA from all strains was isolated by using a DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR assay for virulent genes was performed as described previously (19). Either E. coli strain EDL933 or serotype O157:H7 strain 204P was used as the positive control, since both of these strains carry all target genes. E. coli K-12 was used as a negative control.

Cell culture.

African green monkey kidney (Vero, CCL-81) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The cells were maintained in 25-cm2 flasks with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Sigma) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, Ga.). For cytotoxicity assays, confluent cell monolayers were trypsinized by using a standard procedure and were grown in 48-well plates at 37°C with 7% CO2 and humidity for 2 to 3 days.

Toxin preparation.

Toxins were prepared as described previously (40). Briefly, bacterial isolates were grown in 20 ml of BHI broth for 23 to 26 h at 37°C with constant shaking. Aliquots (1.5 ml) were centrifuged (9,279 × g, 3 min). Cell-free supernatants were stored in sterile tubes and maintained at 4°C until they were used. Each cell pellet was resuspended in 75 μl of a polymyxin B sulfate solution (2 mg/ml) in order to release cell-bound toxins (15) and was incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a shaker incubator. Samples were centrifuged (9,279 × g, 5 min) and combined with the original cell-free supernatants. Toxin preparations were filtered with 0.45-μm-pore-size syringe filters (Nalgene), and the filtrates were either used immediately or kept at 4°C for a maximum of 24 h.

Cytotoxicity assay.

The cytotoxic potential of E. coli strains was evaluated as previously described, with a few modifications (40). Vero cells (∼5 × 104cells/well) were grown in 48-well tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson) for 2 to 3 days, and cell monolayers were washed with serum-free DMEM (Sigma). The cells were exposed to 250 μl of a bacterial toxin preparation and 150 μl of serum-free DMEM. Each sample was examined in triplicate. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C in the presence of 7% CO2, Vero cell supernatants were centrifuged (300 × g, 5 min), and the release of endogenous LDH from the cytosol of damaged cells was measured by dispensing a 0.1-ml aliquot of cell supernatant combined with 0.1 ml of LDH substrate (diaphorase NAD+ mixture with iodotetrazolium chloride and sodium lactate) into each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. The LDH substrate was prepared by using the instructions for a cytotoxicity detection kit (LDH) (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Ind.). The plates were incubated at room temperature, and the absorbance at 490 and 655 nm was measured by using a plate reader (Bio-Rad) after 5 min and then every 3 min for a total of 20 min. E. coli strains EDL933 (O157:H7) and K-12 were used as positive and negative controls, respectively, for each experiment. Percent cytotoxicity values were determined based on the amount of LDH released from 17-min readings for the positive (E. coli EDL933) and negative (E. coli K-12) controls in each experiment, as follows: percent cytotoxicity = (Aexp − AK12)/AEDL933 − AK12) × 100, where Aexp is the absorbance of the sample, AK12 is the absorbance of E. coli K-12, and AEDL933 is the absorbance of E. coli EDL933.

Ribotyping.

Selected E. coli isolates were ribotyped (22) with the automated RiboPrinter microbial characterization system (Qualicon Inc., Wilmington, Del.) by following the manufacturer's directions.

REP-PCR.

E. coli O157:H7 isolates from food sources (Table 1) were grown in BHI broth, and DNA was extracted with a DNeasy tissue kit as described by the manufacturer (QIAGEN). Genotyping was performed by using two different primer sets for REP-PCR because all isolates could not be amplified with the initial REP-PCR primer set. The PCR reagents and amplification conditions used were those described previously (34). The primers used were REP IR (5′-III ICG ICG ICA TCI GGC-3′) and REP 2-I (5′-ICG ICT TAT CIG GCC TAC-3′) and/or Box A1R (5′-CTA CGG CAA GGC GAC GCT GAC G-3′) (12, 13). Amplified products (10 μl) were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer at a constant voltage of 70 V for 18 h. A 100-bp (100- to 3,000-bp) PCR molecular ruler (Bio-Rad) was used as a standard. Gel images were analyzed with the BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). The positions of the bands were normalized with respect to the molecular size standard. Bands were assigned manually to correct unsatisfactory detection. Only PCR products that were 0.3 to 1.2 kb long were considered for analysis in this study. Similarities between DNA fingerprints were determined on the basis of the Jaccard similarity coefficient. A cutoff factor of 80% was chosen to differentiate between groups. A dendrogram was generated by using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages.

RESULTS

Virulence gene profiles.

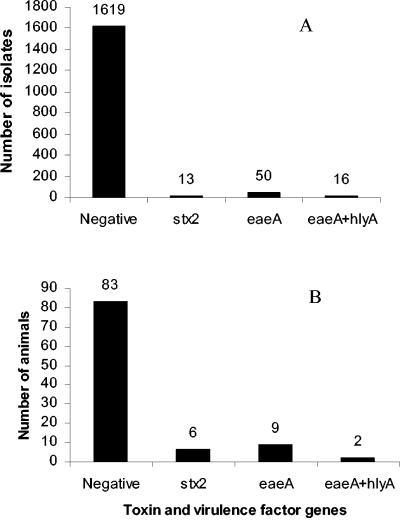

PCR analysis of 1,698 environmental isolates indicated that at least one of the virulence-associated genes was present in 79 (5%) of the sequences (Table 1 and Fig. 1). These genes were distributed among 16% (16 of 100) of the individual hosts that were sampled (Fig. 1) and were found mainly in cows (36%, 4 of 11 animals) and pigs (47%, 7 of 15 animals). The eaeA gene was the most commonly found of the four target genes (Table 1). It was present in 4% (66 of 1,698) of the isolates, whose hosts included one cat, one raccoon, one chipmunk, three cows, and five pigs (11% of the hosts). The hlyA gene was detected in 16 isolates derived from two cows and was found only in conjunction with the eaeA gene. The stx2 gene was found in 13 isolates collected from six hosts (one cow, three pigs, one wildlife, and one sewage). All stx2-positive isolates were negative for the other three genes. The stx1 gene was not found in any of the environmental isolates tested. The number of isolates obtained from an individual host that carried one of the target genes ranged from 1 to 15. Typically, the same target gene(s) was found in multiple isolates from the same individual, with the exception of one host, which yielded isolates with stx2 or the eaeA gene.

FIG. 1.

(A) Distribution of toxin and virulence factor genes in the environmental E. coli isolates examined. (B) Distribution of toxin and virulence factor genes in the host animals examined. A host animal was considered positive for a gene if at least one isolate collected from it was positive.

As expected, the majority of the food and clinical isolates (84%; 68 of 81 isolates) were positive for all four genes (stx1, stx2, eaeA, and hlyA) (Table 2). Six O157:H7 strains lacked stx1 but contained the other target genes, while in the O91:H21 strain only stx2 and hlyA were amplified by PCR. The O55:H7 strain, an E. coli O157:H7 ancestor, carried only the eaeA gene. Two strains belonging to serogroup O157 (O157:H12 strain 489 and O157:H19 strain 490), as well as the ATCC 51739 strain, did not produce any PCR products. In addition, two other non-O157:H7 isolates, O157:NM strain 488 and O111:H11 strain HAL EC91011, were positive for the eaeA and hlyA genes but lacked the stx1 and stx2 genes, respectively.

Cytotoxicity profiles.

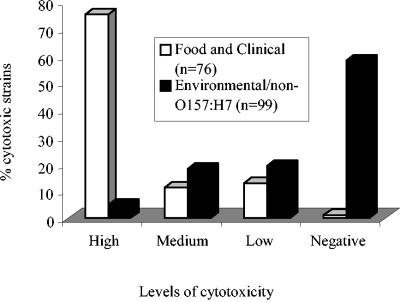

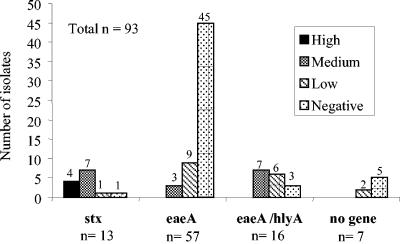

A total of 174 E. coli strains were examined for cytotoxicity and compared to the positive control O157:H7 strain EDL933 and the negative control K-12 strain (Tables 1 and 2). Only the 87 environmental isolates that were positive for at least one of four virulence gene markers (stx1, stx2, eaeA, and hlyA) and six isolates that showed no PCR product were tested for cytotoxicity. The LDH release values for EDL933 ranged from 0.21 to 0.73, and the LDH release values for K-12 ranged from 0.06 to 0.16. The percent cytotoxicity values were arbitrarily grouped into negative (<1%), low (1 to 20%), medium (21 to 49%), and high (>50%) categories. A small fraction of the environmental isolates (4%, 4 of 93 isolates) were in the high category, 18% (17 of 93 isolates) were in the medium category, 19% (18 of 93 isolates) were in the low category, and 58% (54 of 93 isolates) showed negative cytotoxicity (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 2). Two of the environmental isolates that were not PCR positive for any of the target genes, F52 and F113, showed low cytotoxicity. The cytotoxic potentials of environmental isolates correlated with the presence of the Shiga toxin genes (Fig. 3). As expected, the food and clinical isolates (from outbreak and nonoutbreak sources) in general induced greater LDH release from Vero cells than the environmental isolates induced. Of the 81 food and clinical isolates, 71% (58) fell into the high category, 12% (10) fell into the medium category, 13.5% (11) fell into the low category, and 4% (3) were negative.

FIG. 2.

Percentages of cytotoxic E. coli strains from food, clinical, and environmental sources. Cytotoxicity values were arbitrarily grouped into the following four categories: high (>50%), medium (21 to 49%), low (1 to 20%), and negative (<1%).

FIG. 3.

Distribution of E. coli isolates from the environment according to the virulence genes present and their cytotoxic effects. The number above each bar indicates the number of isolates in the cytotoxicity category.

Sorbitol utilization.

Sorbitol utilization was tested as a potential characterization tool for cytotoxic environmental isolates (Tables 1 and 2). Unlike the E. coli strains from clinical and food sources, these isolates were not serotyped when they were isolated. All O157:H7 isolates were unable to ferment sorbitol, producing colorless colonies on sorbitol MacConkey agar. Also, two non-O157:H7 isolates (O157:NM strain 488 and O111:H11 strain HAL EC91011) and 29% (27 of 93) of the environmental isolates were unable to ferment sorbitol. Positive fermentation of sorbitol (pink colonies) occurred in non-O157:H7 strains, as well as in 71% (66 of 93) of the environmental isolates.

Ribotyping.

The ribopatterns for all O157:H7 isolates from food and clinical sources were identical, matching the ribopattern for E. coli O157:H7 strain DUP 3064 in the database. The patterns of isolates serotyped as O157:NM strain 488 and O55:H7 also matched this pattern. The RiboPrinter identification guide indicated that these strains, along with O157:H- and O157:NM strains, have with the same DUP number as E. coli O157:H7. Ribotyping of selected environmental isolates revealed that they belonged to 18 distinct ribogroups of E. coli but did not belong to serotype O157:H7. The identification library for the RiboPrinter system includes 65 patterns for E. coli; however, except for O157:H7, no ribopatterns are provided for other serogroups.

REP-PCR.

There were no common REP-PCR fingerprint patterns that provided a means for differentiating either O157:H7 sources or environmental isolates carrying toxin or virulence genes. REP-PCR analyses of the O157:H7 isolates revealed the presence of three major genotypes (Fig. 4). However, similar genetic fingerprints were found in isolates from different sources, and differences among isolates obtained from the same source (e.g., ground beef) were also found. Many of the environmental isolates were not amplified with the REP primers and therefore were also genotyped by using the Box A1R primer, which produced a variety of Box-PCR fingerprint patterns (data not shown). Generally, all isolates positive for the stx2, eaeA, and hlyA genes that had the same Box-PCR fingerprint pattern were obtained from the same individual host animal. Often the fingerprint patterns were identical to those of isolates that did not carry the genes. The levels of similarity of the Box-PCR fingerprints of isolates that were positive for toxin or virulence factor genes to the Box-PCR fingerprint of the most similar isolate in the environmental collection without these genes ranged from 57 to 100%. This variability in fingerprint patterns suggest that REP-PCR is not a good means for differentiating environmental isolates that carry toxin or virulence genes.

FIG. 4.

REP-PCR analysis of E. coli O157:H7 isolated from food sources. BioNumerics software was used to determine Jaccard similarity coefficients in order to quantify the similarity between DNA fingerprints, and the data then were visualized by using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages. A cutoff factor of 80% was used, which classified O157:H7 isolates into three major groups (groups I, II, and III).

DISCUSSION

In this study, a correlation between the virulence gene profiles and the cytotoxicity profiles for E. coli isolates obtained from food, clinical, and environmental sources was found. Of the ∼5% (79 of 1,698) of the environmental isolates that were shown to carry at least one of the virulence-associated genes tested, about 40% were cytotoxic (Fig. 3). Most of these isolates harbored either the stx2 gene or the eaeA and hlyA genes (Table 1). Most food and clinical isolates from outbreaks carried three or four of the virulence-associated genes (Table 2) and in general induced higher levels of cytotoxicity (Fig. 2). The presence of virulent strains of E. coli in the environment may be a potential source of contamination of food and the water supply. Moreover, these strains may comprise a potential reservoir of virulence genes acquired from different sources (e.g., bacteriophages and plasmids). E. coli is a very dynamic organism; it has a capacity for horizontal gene transfer to increase genetic diversity, and under certain circumstances this can lead to the emergence of new pathogenic strains (14, 25). In addition to E. coli O157:H7, which has been implicated in numerous food-borne and waterborne outbreaks (28, 32), non-O157:H7 STEC have also been implicated in human gastrointestinal disease and other serious complications (7, 41). A phenotypic trait, lack of sorbitol fermentation, and two genotypic methods, ribotyping and REP-PCR, did not distinguish cytotoxigenic strains from noncytotoxigenic strains. The prevalence of non-O157 strains is often underestimated because they do not have a recognized biological marker that facilitates the initial screening of these isolates (26). Therefore, alternative methods for recognizing potentially virulent bacteria are needed to control the spread of pathogens and to reduce the risk of infection.

The cytotoxicity assay based on LDH release from Vero cells was useful for determining the virulence potential of E. coli strains, especially food and environmental isolates which have not been involved in outbreaks. Although the percentages of cytotoxicity were arbitrarily categorized, this method is a more sensitive, rapid, and convenient approach for quantitating cytotoxicity than other assays (24, 36, 46). It is important to note that in our study the percent cytotoxicity values were not absolute, since they were calculated based on the LDH released by positive and negative controls for each experiment. A number of factors can result in variability between experiments, including the health of the Vero cells, the culture conditions, the stability of the LDH substrate, and sufficient protection of the substrate from light during incubation. During this study, a new batch of Vero cells was grown periodically to avoid changes in cell properties. The variability that was observed here is common for similar cytotoxicity-based assays and is within the acceptable range (4, 40).

The cytotoxic effects displayed by the environmental, food, and clinical isolates that were both outbreak-associated and non-outbreak-associated isolates indicate that the detection of stx (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 3) is an important indicator of virulence, and they contribute to cell damage and death in Vero cells (31, 45). The results imply that the ability of non-outbreak-associated isolates to cause human infection is equivalent to or greater than the ability of isolates associated with outbreaks to cause infection. A recent survey showed that about 7.4% of fecal and farm environmental samples from dairy, feedlot, and range cow calf operations were positive for STEC and that 9% of the isolates carried three main virulence markers (stx2, eae, and ehx) (10). In addition to cows, in our study we found that cytotoxic strains with virulence-associated genes (either stx2 alone or both eaeA and hlyA) were also present in isolates originating from sewage and fecal samples from pigs, a cat, a raccoon, a chipmunk, and deer (Table 1). This is an important consideration when sources of fecal contamination in the environment are being differentiated to assess the potential risk to human health (44).

Isolates that were stx positive were all cytotoxic, but the cytotoxicity categories ranged from low to high, indicating that gene presence alone cannot be used as a means to determine the virulence potential of strains. EHEC strains are characterized on the basis of their production of Shiga-like toxins, and although the pathogenic mechanisms are not completely understood, these toxins play an important role in the development of disease (31, 33). The expression of the stx1 and stx2 genes is regulated by environmental and genetic factors (31, 39). This may have led to the variability in the cytotoxic responses of isolates PCR positive for stx. Variation in toxin production can lead to differences in the cytopathic effects on Vero cells (30, 36). Isolates in which the stx genes were absent were also cytopathic, indicating that these diverse environmental strains may carry some other virulence factors, which result in cytotoxicity to Vero cells.

The majority of environmental strains that were eaeA and hly positive could induce low or medium cytotoxicity. In contrast, the majority of isolates that were positive for only the eaeA gene induced negative LDH release, suggesting that hlyA played a larger role in the induction of LDH release from Vero cells. We made several attempts to determine the hemolysin activity on blood agar plates (42) but failed. It appears that there is no reliable phenotypic test on blood agar plates for EHEC strains (R. Welch, personal communication). eaeA and EHEC hly have been found in non-O157 STEC isolates from cattle and humans implicated in human disease (1, 18). Bovine isolates carrying only the EHEC hly gene have also been reported (18). A low frequency of stx-deficient E. coli O157 strains has been associated with human disease (43). Enterohemolysin (EHEC Hly) is a pore-forming cytolysin that belongs to the RTX (repeats in toxin) family (2). EHEC hly is present in other E. coli serogroups, including O26:H11, O26:H-, O111:H-, and O111:H8 (18). EHEC hly has exhibited cytolytic activity against BL-3 cells (bovine lymphoma) and sheep and human erythrocytes (2). Nevertheless, EHEC hly has no direct role in bacterial pathogenesis, but it may facilitate bacterial survival by sequestering iron from erythrocytes (27), whereas it is known that the eaeA gene encoding intimin, an outer membrane protein, is associated with the formation of attaching and effacing lesions during the adhesion of STEC to enterocytes and has a strong association with disease (6, 26). This indicates again that the presence or absence of particular genes is insufficient for predicting the virulence potential and that more research is necessary in order to understand the factors that contribute to E. coli pathogenesis.

Sorbitol utilization is often used as a method to screen for pathogenic strains of E. coli, but our results demonstrate that there are cytopathic strains that are able to ferment sorbitol (Table 1). Other workers have also shown that production of Shiga toxins (a key factor defining EHEC O157:H7) does not necessarily correspond to the inability of certain environmental isolates to ferment sorbitol (17), and non-O157 E. coli serogroups associated with human disease, including O157:H- (43), have been shown to ferment sorbitol (23, 28). As a result, pathogenic strains might go undetected when this approach is used. Furthermore, we previously showed that serotyping could not be used to identify pathogenic strains (11). Also, the presence of the O157 antigen does not always indicate that the isolate in question is indeed an EHEC strain (5). These findings indicate that pathogenic isolates can be obtained by screening phenotypic traits, such as sorbitol fermentation, and by serotyping. However, they may also lead to exclusion of some equally or more harmful strains.

Neither ribotyping nor REP-PCR could be used to identify or differentiate the cytotoxic environmental E. coli strains. Certain E. coli strains having a ribopattern different from the DUP 3064 (O157:H7) pattern displayed cytotoxic effects comparable to those of the isolates obtained from outbreaks (Tables 1 and 2). While the ribotypes of food and clinical isolates were identical to the E. coli O157:H7 (DUP 3064) ribotype (Table 2), there were a variety of patterns among the environmental isolates that did not correlate with specific sources (Table 1). The REP-PCR results also showed there are extensive genotypic differences among these strains. REP-PCR is thought to distinguish among E. coli strains from different sources at a finer scale than ribotyping (8). A previous study in which several environmental isolates included in this research were used revealed that the REP-PCR fingerprint patterns for these isolates were diverse, and the method was able to differentiate them from the O157 group (19). However, a direct relationship between REP-PCR fingerprint patterns and cytotoxicity could not be established, indicating that an alternative means to rapidly differentiate potentially pathogenic strains of E. coli from a background in which nonpathogenic E. coli dominates is still needed.

In this study, we were able to compare the virulence potential of E. coli isolates from the environment to the virulence potential of strains that were obtained from outbreaks. Of the methods examined, PCR and the Vero cell assay were the two most effective methods for predicting the pathogenic potential of environmental E. coli. As expected, high levels of cytotoxicity occurred with outbreak isolates, as well as with the EHEC food isolates. The fact that a number of environmental isolates with at least one virulence gene, particularly an stx gene, caused a degree of cytotoxicity comparable to that of the isolates from outbreaks is a matter of concern. This suggests that the multiple virulence factors typically used to identify potentially virulent E. coli strains are insufficient for distinguishing cytopathic isolates. Also, the presence one isolate carrying a virulence gene makes the host animal a potential source of infectious strains, thus increasing the risk for human infection if the strains enter the food chain through fecal or water contamination. Further analysis of the pathogenic potential of E. coli strains should be valuable for assessing the prevalence and health risks of virulent strains in various sources, especially the isolates whose virulence gene profiles do not correspond to currently defined E. coli pathotypes.

Acknowledgments

Part of this research was supported by United States Environmental Protection Agency grant R-82833901-0, by U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service project 1935-42000-035, and by the Center for Food Safety and Engineering at Purdue University. Y. Maldonado was supported by a Minority Research Fellowship from Purdue University.

We thank Ron Turco for valuable discussions and Briana Bosse, Steven Yeary, Felipe Camacho, and Chaney Craft for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrett, T., J. Kaper, A. Jerse, and I. Wachsmuth. 1992. Virulence factors in Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from humans and cattle. J. Infect. Dis. 165:979-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer, M., and R. Welch. 1996. Characterization of an RTX toxin from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 64:167-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beutin, L., M. A. Montenegro, I Orskov, F Orskov, J. Prada, S Zimmermann, and R. Stephan. 1989. Close association of verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin) production with enterohemolysin production in strains of Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2559-2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhunia, A. K., and D. G. Westbrook. 1998. Alkaline phosphatase release assay to determine cytotoxicity for Listeria species. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 26:305-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blank, T. E., D. W. Lacher, I. C. A. Scaletsky, H. Zhong, T. S. Whittam, and M. S. Donnenberg. 2003. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O157 strains from Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:113-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boerlin, P., S. A., McEwen, F. Boerlin-Petzold, J. B. Wilson, R. P. Johnson, and C. L. Gyles. 1999. Association between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:497-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnet, R., B. Souweine, G. Gauthier, C. Rich, V. Livrelli, J. Sirot, B. Joly, and C. Forestier. 1998. Non-O157:H7 Stx2-producing Escherichia coli strains associated with sporadic cases of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in adults. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1777-1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carson, C. A., B. L. Shear, M. R. Ellersieck, and J. D. Schnell. 2003. Comparison of ribotyping and repetitive extragenic palindromic-PCR for identification of fecal Escherichia coli from humans and animals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1836-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chern, E. C., Y. L. Tsai, and B. H. Olson. 2004. Occurrence of genes associated with enterotoxigenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in agricultural waste lagoons. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:356-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cobbold, R. N., D. H. Rice, M Szymanski, D. R. Call, and D. D. Hancock. 2004. Comparison of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli prevalences among dairy, feedlot, and cow-calf herds in Washington state. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4375-4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis, K., C. Nakatsu, R. Turco, S. Weagant, and A. Bhunia. 2003. Analysis of environmental Escherichia coli isolates for virulence genes using the TaqMan PCR system. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95:612-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Bruijn, F. 1992. Use of repetitive (repetitive extragenic palindromic and enterobacterial repetitive intergeneric consensus) sequences and the polymerase chain reaction to fingerprint the genomes of Rhizobium meliloti isolates and other soil bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2180-2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dombek, P. E., L. K. Johnson, S. T. Zimmerley, and M. J. Sadowsky. 2000. Use of repetitive DNA sequences and the PCR to differentiate Escherichia coli isolates from human and animal sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2572-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnenberg, M. S., and T. S. Whittam. 2001. Pathogenesis and evolution of virulence in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Investig. 107:539-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donohue-Rolfe, A., and G. Keusch. 1983. Shigella dysenteriae 1 cytotoxin: periplasmic protein releasable by polymyxin B and osmotic shock. Infect. Immun. 39:270-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiser, J. C. 2004. Determination of Escherichia coli population genotypic variability within and between host animals using rep-PCR. M.S. thesis. Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind.

- 17.Fratamico, P. M., R. L. Buchanan, and P. H. Cooke. 1993. Virulence of an Escherichia coli O157:H7 sorbitol-positive mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:4245-4252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gyles, C., R. Johnson, A. Gao, K. Ziebell, D. Pierard, S. Aleksic, and P. Boerlin. 1998. Association of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli hemolysin with serotypes of Shiga-like-toxin-producing Escherichia coli of human and bovine origins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4134-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahm, B. K., Y. Maldonado, E. Schreiber, A. K. Bhunia, and C. H. Nakatsu. 2003. Subtyping of foodborne and environmental isolates of Escherichia coli by multiplex-PCR, rep-PCR, PFGE, ribotyping and AFLP. J. Microbiol. Methods 53:387-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hancock, D., T. Besser, D. Rice, E. Ebel, D. Herriott, and L. Carpenter. 1998. Multiple sources of Escherichia coli O157 in feedlots and dairy farms in the northwestern USA. Prev. Vet. Med. 35:11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard, B., J. Keiser, T. Smith, A. Weissfeld, and R. Tilton. 1994. Clinical and pathogenic microbiology, 2nd ed. Mosby-Year Book, St. Louis. Mo.

- 22.Jaradat, Z. W., G. E. Schutze, and A. K. Bhunia. 2002. Genetic homogeneity among Listeria monocytogenes from infected patients and meat products from two geographic locations determined by phenotyping, ribotyping and PCR analysis of virulence genes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 76:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, R. P., R. C. Clarke, J. B. Wilson, S. C. Read, K. Rahn, S. A. Renwick, K. A. Sandhu, D. Alves, M. A. Karmali, H. Lior, S. A. Mcewen, J. S. Spika, and C. L. Gyles. 1996. Growing concerns and recent outbreaks involving non-O157:H7 serotypes of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Food Prot. 59:1112-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konowalchuk, J., J. Speirs, and S. Stavric. 1977. Vero response to a cytotoxin of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 18:775-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhnert, P., P. Boerlin, and J. Frey. 2000. Target genes for virulence assessment of Escherichia coli isolates from water, food and the environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Law, D. 2000. Virulence factors of Escherichia coli O157 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88:729-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Law, D., and J. Kelly. 1995. Use of heme and hemoglobin by Escherichia coli O157 and other Shiga-like-toxin-producing E. coli serogroups. Infect. Immun. 63:700-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mead, P., and P. Griffin. 1998. Escherichia coli O157:H7. Lancet 352:1207-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Brien, A., G. LaVeck, M. Thompson, and S. Formal. 1982. Production of Shigella dysenteriae type 1-like cytotoxin by Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 146:763-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Loughlin, E. V., and R. M. Robins-Browneb. 2001. Effect of Shiga toxin and Shiga-like toxins on eukaryotic cells. Microbes Infect. 3:493-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsen, S., G. Miller, T. Breuer, M. Kennedy, C. Higgins, J. Walford, G. McKee, K. Fox, W. Bibb, and P. Mead. 2002. A waterborne outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections and hemolytic uremic syndrome: implications for rural water systems. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:370-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paton, J. C., and A. W. Paton. 1998. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:450-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rademaker, J. L. W., F. J. Louws, and F. J. de Bruijn. 1998. Characterization of the diversity of ecologically important microbes by rep-PCR genomic fingerprinting, p. 3.4.3:1-3.4.3:27. In A. D. L. Akkermans, J. D. van Elsas, and F. J. de Bruijn (ed.), Molecular microbial ecology manual. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 35.Radu, S., O. W. Linga, G. Rusulb, M. I. A. Karima, and M. Nishibuchi. 2001. Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by multiplex PCR and their characterization by plasmid profiling, antimicrobial resistance, RAPD and PFGE analyses. J. Microbiol. Methods 46:131-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahn, K., J. B. Wilson, K. A. McFadden, S. C. Read, A. G. Ellis, S. A. Renwick, R. C. Clarke, and R. P. Johnson. 1996. Comparison of Vero cell assay and PCR as indicators of the presence of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli in bovine and human fecal samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4314-4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rasmussen, M., and T. Casey. 2001. Environmental and food safety aspects of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections in cattle. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 27:57-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renter, D. G., J. M. Sargeant, R. D. Oberst, and M. Samadpour. 2003. Diversity, frequency, and persistence of Escherichia coli O157 strains from range cattle environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:542-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritchie, J. M., P. L. Wagner, D. W. K. Acheson, and M. K. Waldor. 2003. Comparison of Shiga toxin production by hemolytic-uremic syndrome-associated and bovine-associated Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1059-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts, P. H., K. C. Davis, W. R. Garstka, and A. K. Bhunia. 2001. Lactate dehydrogenase release assay from Vero cells to distinguish verotoxin producing Escherichia coli from non-verotoxin producing strains. J. Microbiol. Methods 43:171-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt, H., C. Geitz, P. I. Tarr, M. Frosch, and H. Karch. 1999. Non-O157:H7 pathogenic Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: phenotypic and genetic profiling of virulence traits and evidence for clonality. J. Infect. Dis. 179:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt, H., H. Karch, and L. Beutin. 1994. The large-sized plasmids of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 strains encode hemolysins which are presumably members of the E. coli alpha-hemolysin family. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 117:189-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt, H., J. Scheef, H. I. Huppertz, M. Frosch, and H. Karch. 1999. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and O157:H- strains that do not produce Shiga toxin: phenotypic and genetic characterization of isolates associated with diarrhea and hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3491-3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson, J. M., J. W. Santo Domingo, and D. J. Reasoner. 2002. Microbial source tracking: state of the science. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:5279-5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uchida, H., N. Kiyokawa, T. Taguchi, H. Horie, J. Fujimoto, and T. Takeda. 1999. Shiga toxins induce apoptosis in pulmonary epithelium-derived cells. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1902-1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valdivieso-Garcia, A., R. C. Clarke, K. Rahn, A. Durette, D. L. MacLeod, and C. L. Gyles. 1993. Neutral red assay for measurement of quantitative Vero cell cytotoxicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1981-1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]