Abstract

The analysis of host immunity to mycobacteria and the development of discriminatory diagnostic reagents relies on the characterization of conserved and species-specific mycobacterial antigens. In this report, we have characterized the Mycobacterium avium homolog of the highly immunogenic M. leprae 35-kDa protein. The genes encoding these two proteins were well conserved, having 82% DNA identity and 90% identity at the amino acid level. Moreover both proteins, purified from the fast-growing host M. smegmatis, formed multimeric complexes of around 1000 kDa in size and were antigenically related as assessed through their recognition by antibodies and T cells from M. leprae-infected individuals. The 35-kDa protein exhibited significant sequence identity with proteins from Streptomyces griseus and the cyanobacterium Synechoccocus sp. strain PCC 7942 that are up-regulated under conditions of nutrient deprivation. The 67% amino acid identity between the M. avium 35-kDa protein and SrpI of Synechoccocus was spread across the sequences of both proteins, while the homologous regions of the 35-kDa protein and the P3 sporulation protein of S. griseus were interrupted in the P3 protein by a divergent central region. Assessment by PCR demonstrated that the gene encoding the M. avium 35-kDa protein was present in all 30 M. avium clinical isolates tested but absent from M. intracellulare, M. tuberculosis, or M. bovis BCG. Mice infected with M. avium, but not M. bovis BCG, developed specific immunoglobulin G antibodies to the 35-kDa protein, consistent with the observation that tuberculosis patients do not recognize the antigen. Strong delayed-type hypersensitivity was elicited by the protein in guinea pigs sensitized with M. avium.

The Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) consists predominantly of two species, M. avium and M. intracellulare (12). Members of the MAC are ubiquitous environmental organisms, present in soil, water, food, and a variety of animal species (12). Although human infection caused by MAC can be serious, they are rare in immunocompetent individuals. By contrast, disseminated MAC infection represents the major cause of systemic bacterial infection in AIDS patients (3). Up to 50% of AIDS patients may develop MAC infection, which contributes significantly to the morbidity and mortality of the disease (9). Owing to the increasing medical importance of the MAC, research has been directed toward understanding the immunopathology of infection caused by these organisms. These studies have included the identification a number of protein antigens of the MAC, through the screening of expression libraries with anti-MAC monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (18–20, 28, 29) or the identification of homologs of known antigens from other mycobacterial species (2, 23). Some of these antigens, such as the secreted antigen 85B, are common to all mycobacteria (23), while others, including the immunogenic 19- and 27-kDa lipoproteins of M. intracellulare, are restricted to a few mycobacterial species (19, 20) and as such may be useful candidates for the specific detection of MAC infection. While a number of these antigens were immunogenic, being recognized by the host immune response or able to elicit delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) in MAC-sensitized guinea pigs, none were able to show adequate immunological discrimination between the MAC and M. tuberculosis (1, 8, 15, 17, 19, 20, 28).

The 35-kDa protein of Mycobacterium leprae is one of two major membrane components of the leprosy bacillus (11). The other major membrane protein is a bacterioferritin, and its abundance within in vivo-grown M. leprae has been postulated to facilitate acquisition of iron by the bacillus within the nutrient-limited environment of the macrophage (25). The 35-kDa protein is also highly abundant within M. leprae, but its specific biological function is unknown, and further analysis is hindered by the inability to cultivate M. leprae in vitro. Nevertheless, the 35-kDa protein is a major antigenic component of the leprosy bacillus, as it is recognized by the majority of leprosy patients and healthy contacts of leprosy patients (referred to as healthy leprosy contacts) tested (37). By contrast, tuberculosis (TB) patients do not recognize the 35-kDa protein (37), consistent with previous genetic and serological evidence that the protein is absent from M. tuberculosis (31, 39). Furthermore, skin tests with the antigen distinguished between sensitization with M. leprae and M. tuberculosis in guinea pigs (37).

Hybridization studies with the gene encoding the M. leprae 35-kDa protein identified a homologous region in the genome of M. avium (38). In this study, we have characterized the gene encoding the M. avium 35-kDa protein and purified the protein from a rapidly growing mycobacterial host. Genetic, structural, and immunological analyses revealed a high degree of similarity between the M. avium 35-kDa protein and its M. leprae counterpart. Subsequent analyses revealed strong similarity of the M. avium and M. leprae 35-kDa proteins with two stress-induced proteins from distinct bacterial genera. Specific immune responses to the M. avium 35-kDa protein developed during experimental M. avium infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

M. avium IS94 (a clinical isolate from a human immunodeficiency virus-infected individual), M. avium MAC101 (provided by C. Cheers, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia), and M. tuberculosis H37Rv and M. bovis BCG CSL (Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Parkville, Victoria Australia) were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). M. smegmatis was grown in LB medium (30) supplemented with 0.05% Tyloxacol (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). MAC clinical isolates were provided by William Chu, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, New South Wales, Australia.

Antigens and antibodies.

The recombinant M. leprae 35-kDa protein was purified by MAb affinity chromatography as described previously (37). Murine anti-M. leprae 35-kDa protein MAb CS-38 was a kind gift of P. J. Brennan (Colorado State University, Fort Collins), and murine anti-M. leprae 35-kDa protein MAb ML-03 was kindly supplied by J. Ivanyi (Hammersmith Hospital, London, England).

DNA manipulation.

DNA manipulations were carried out by using standard techniques (30). Sequence of double-stranded DNA templates were determined by the dideoxy-chain termination method with the use of Sequenase (United States Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequences were compared to those in the GenBank, EMBL, Genpeptide, PIR, and Swissprot databases, using the FASTA algorithm (25). M. leprae and M. avium NCTC 8559 DNAs were provided by M. J. Colston (National Institute for Medical Research, London, England) and K. Jackson (Victorian Infectious Disease Reference Laboratory, Fairfield, Victoria, Australia), respectively. PCR amplification of the 35-kDa protein-encoding gene from M. avium clinical isolates was performed with the primers JA8 (5′ GGCGCCGGCAGCGAAGAG 3′) and JA11 (5′ TCACTTGTACTCATGGAA 3′). Single M. avium colonies were resuspended in 100 μl of distilled water and boiled for 5 min, and 5 μl of the suspension was used for PCR (94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min; 30 cycles). The PCR-amplified product of primers JA7 (5′ CTCGGTACCATTTTTCGACC 3′) and JN9 (5′ CTAGAATTCGAGCTCAAGCTTTCACTTGTACTC 3′) was used in the construction of plasmid pAJ11.

Purification of the M. avium 35-kDa protein from M. smegmatis.

Plasmid DNA (1 μg) was electroporated into M. smegmatis mc2155 (31), using a gene pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Kanamycin-resistant colonies were screened for expression by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting with MAb CS-38 as previously described (26). Single recombinant M. smegmatis colonies were inoculated into 1 liter of LB medium supplemented with 0.05% Tyloxacol and incubated for 3 days at 37°C with shaking. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, and 1 M NaCl, and the suspension sonicated four time for 4 min each. Anti-35-kDa protein immunoglobulin G (IgG) was purified from MAb ML-03 ascites fluid and coupled to cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). M. smegmatis sonicate was passed over the affinity column; the column was washed with 10 volumes of sonication buffer without Triton X-100 and 5 volumes of PBS containing 0.5 M NaCl. Bound protein was eluted with 0.1 M diethylamine (pH 11.0) and dialyzed against PBS. Molecular mass estimation of the 35-kDa protein was performed by gel filtration using a Superose 6 fast performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) column (Pharmacia). The column was calibrated by using four standard proteins; aldolase (158 kDa), catalase (232 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), and thyroglobulin (669 kDa) (Pharmacia).

Detection of anti-35-kDa protein antibodies.

Microtiter plates were coated with antigen (100 pg/ml to 100 μg/ml) overnight at room temperature. Plates were washed and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin, and pooled sera (diluted 1:100) were added for 90 min at 37°C. Plates were washed, and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-human IgG (Sigma) was added for 60 min at 37°C. Binding was visualized by the addition of n-nitrophenyl phosphate (1 mg/ml), and absorbance was measured at 405 nm.

Lymphocyte proliferation assays.

Nepali subjects tested for cellular reactivity included 18 paucibacillary (PB) leprosy patients, 12 healthy leprosy contacts, and 10 patients with active TB. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) proliferation was performed and analyzed as described previously (37). The optimal protein concentrations were 10 μg/ml for M. leprae sonicate (MLS) and the M. leprae 35-kDa protein and 3 μg/ml for M. avium 35-kDa protein.

Infection of mice with M. avium.

Eight- to twelve-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were inoculated subcutaneously with PBS, 5 × 106 M. bovis BCG CSL, or M. avium MAC101. At 2 and 4 weeks, sera were collected and the presence of anti-35 kDa antibodies was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using 5 μg of the M. smegmatis-derived M. avium 35-kDa protein per ml. The reactivities of the sera were also tested with M. smegmatis sonicate (5 and 0.5 μg/ml), BCG sonicate (10 μg/ml), and M. avium sonicate (10 μg/ml) as antigens.

Measurement of DTH.

Outbred female guinea pigs, 10 to 12 weeks old, were sensitized intradermally with 0.5 mg (wet weight) of heat-killed M. avium IS94, M. bovis BCG CSL, or M. leprae or gamma-irradiated M. tuberculosis H37Rv. The guinea pigs were challenged intradermally 4 weeks later with 10 μg of MLS or the M. avium 35-kDa protein. The area of induration was measured 24 h later.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number for the gene encoding the M. avium 35-kDa protein is U43835.

RESULTS

Cloning of the gene encoding the M. avium 35-kDa protein.

We previously reported the identification of a 3-kb PstI M. avium chromosomal DNA fragment that hybridized with the gene encoding the M. leprae 35-kDa protein (39). Immunoblotting revealed the presence of a 35-kDa protein in the sonicate of M. avium IS94 that reacted with CS-38, a MAb raised against the M. leprae 35-kDa protein (Fig. 1). To isolate the gene encoding this protein, chromosomal DNA from M. avium IS94 was digested with PstI, and fragments in the range of 2.5 to 4 kb were ligated into pUC19 digested with PstI. Clones were chosen by screening with an α-32P-labeled PCR fragment of the entire M. leprae 35-kDa protein-encoding gene, and the positive clone chosen was termed pAJ6. Sequencing of the 3-kb insert of pAJ6 revealed a major open reading frame encoding a protein of 308 amino acids (Fig. 2). A putative ribosome binding site was identified 5 bp upstream of the predicted translational start codon. The gene was 82% identical to that encoding the M. leprae 35-kDa protein, which translated to 90% identity at the amino acid level (Fig. 3). The lengths and predicted molecular masses of the two proteins were essentially identical.

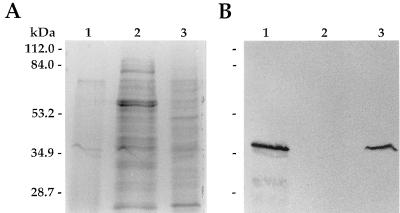

FIG. 1.

Identification of a homolog of the M. leprae 35-kDa protein in M. avium. Sonic extracts (15 μg) of M. avium (lane 1), M. tuberculosis (lane 2), and M. leprae (lane 3) were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (A) and then transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting with the anti-M. leprae 35-kDa protein MAb CS-38 (B).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the 35-kDa protein of M. avium. The nucleotide sequence of 962 bp of the insert of pAJ6 is shown. The deduced protein sequence of the 35-kDa protein is shown above the nucleotide sequence. A potential ribosome binding site is represented by boldface.

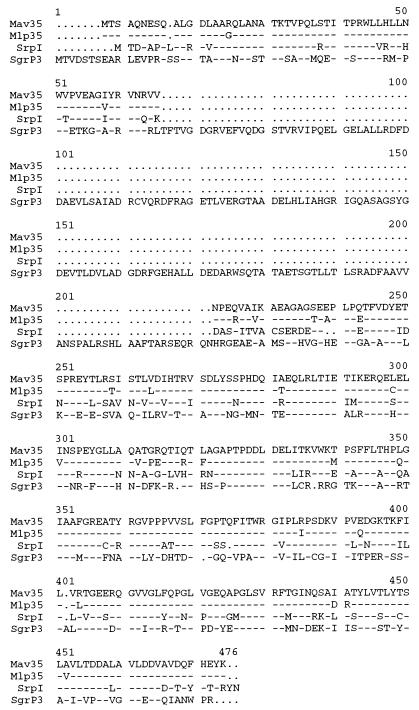

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of the M. avium 35-kDa protein (Mav35) with sequences of the M. leprae 35-kDa protein (Mlp35), Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 SrpI (SrpI), and S. griseus P3 (SgrP3). Amino acids identical to the M. avium 35-kDa protein are indicated by dashes; gaps in the sequence are represented by periods.

Homology searches of nucleotide and protein databases identified two proteins showing significant identity with the 35-kDa protein. The first was the SrpI of Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942, a protein of as yet unknown function induced under condition of sulfur stress and coordinately regulated with two proteins involved in cysteine metabolism by the organism (21, 22). The M. avium 35-kDa protein and SrpI were 67% identical at the amino acid level, with the similarity spread over the entire lengths of the two proteins (Fig. 3). The M. avium 35-kDa protein also showed significant identity with a 52-kDa protein, termed P3, that accumulates during sporulation in Streptomyces griseus under conditions of phosphate deprivation (14). P3 and the 35-kDa protein exhibited 49% amino acid identity, with the homology restricted to the initial 75 amino acids and the C-terminal 236 amino acids of P3 (Fig. 3). The remaining central region of 148 amino acids of P3 showed no similarity to the M. avium 35-kDa protein.

Distribution of the gene encoding the M. avium 35-kDa protein within the MAC.

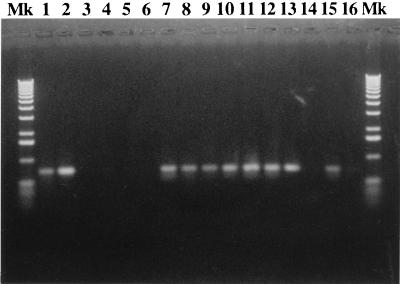

The MAC is composed of a large number of serologically distinct groups (serotypes). To evaluate the distribution of the gene encoding the M. avium 35-kDa protein within this complex, 32 clinical MAC isolates were screened by PCR for the presence or absence of the gene. Figure 4 shows a representative gel of the PCR products. A band of 750 bp indicates a positive result. All MAC isolates classified as M. avium (serovars 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 21) were positive for the gene encoding the M. avium 35-kDa protein (Table 1). The two M. intracellulare isolates (serovar 16) were negative for the gene. The primer combination used was specific to M. avium such that no amplification was detected on chromosomal DNA from M. leprae, M. tuberculosis, or M. bovis BCG (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Detection of the gene encoding the M. avium 35-kDa protein in members of the MAC. PCR was used to detect the 35-kDa protein-encoding gene in serotyped MAC clinical isolates. A 750-bp band indicates a positive result. Lanes: Mk, molecular weight markers; 1 and 15, M. avium IS94; 2 to 5, M. avium NCTC 8559, M. leprae, M. tuberculosis H37Rv, and M. bovis BCG CSL; 7 to 14, MAC serovars 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 21, and 16; 16, no-DNA control.

TABLE 1.

Detection of the gene encoding the M. avium 35-kDa protein in clinical MAC isolates

| Serovar | Classification | No. positive/no. testeda |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | M. avium | 6/6 |

| 2 | M. avium | 2/2 |

| 4 | M. avium | 4/4 |

| 5 | M. avium | 4/4 |

| 8 | M. avium | 7/7 |

| 9 | M. avium | 3/3 |

| 16 | M. intracellulare | 0/2 |

| 21 | M. avium | 4/4 |

Determined by PCR.

Purification of the M. avium 35-kDa protein from recombinant M. smegmatis and comparative analysis of the M. avium and M. leprae 35-kDa proteins.

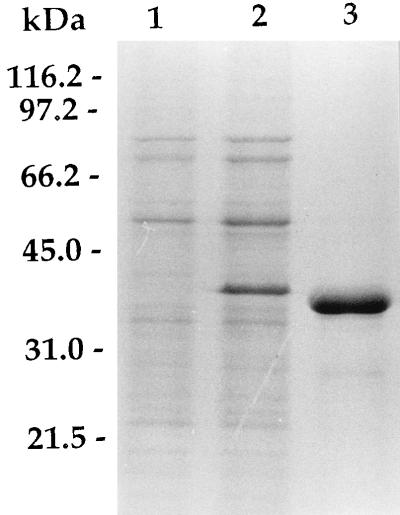

The 35-kDa protein-encoding gene was placed under the control of the strong β-lactamase promoter of M. fortuitum (36), yielding plasmid pAJ11. When pAJ11 was introduced into M. smegmatis, high-level expression of the M. avium 35-kDa protein-encoding gene was observed, such that the protein constituted one of the major protein bands of recombinant M. smegmatis (Fig. 5, lane 2). Recombinant product was efficiently purified from the sonicate of M. smegmatis/pAJ11 by single-step MAb affinity chromatography (Fig. 5, lane 3).

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE of recombinant M. avium 35-kDa proteins purified from M. smegmatis. Twenty micrograms of bacterial sonicate and 10 μg of purified proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lanes: 1, M. smegmatis/pJN30 sonicate; 2, M. smegmatis/pAJ11 sonicate; 3, M. avium 35-kDa protein.

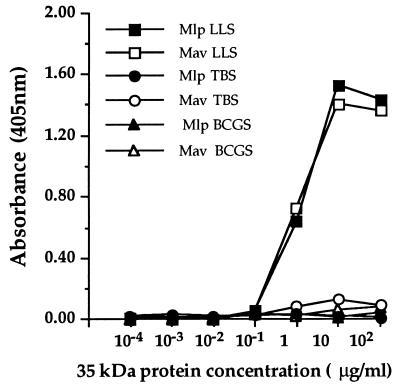

The native M. leprae 35-kDa protein and the recombinant product purified from M. smegmatis form multimeric complexes of around 1,000 kDa in size (37, 39). Superose 6 FPLC separation indicated that the M. avium 35-kDa protein also formed multimeric complexes, estimated at 987 ± 61 kDa (mean of three experiments). As maximal binding of the M. leprae homolog to leprosy sera relied on the protein maintaining a correct conformational state (37), the binding of pooled sera from 10 lepromatous leprosy patients to the M. leprae and M. avium 35-kDa proteins was assessed. Both proteins were equally reactive with these pooled sera over the range of concentrations tested (Fig. 6). By contrast, pooled sera from either 8 tuberculosis patients or 10 BCG vaccinees did not react significantly with either protein (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Recognition of recombinant 35-kDa proteins by leprosy, TB, and BCG vaccinee sera. The binding of pooled lepromatous leprosy sera (LLS), tuberculosis sera (TBS), and sera from BCG vaccinees (BCGS) to the M. avium (Mav) and M. leprae (Mlp) 35-kDa proteins was determined by ELISA.

To determine if the sequence and serological similarities demonstrated between the two proteins could be extended to cellular recognition, the reactivity of the M. avium 35-kDa protein was assessed in leprosy patients and healthy leprosy contacts who recognized the M. leprae homolog, together with TB patients. PBMCs from the majority of healthy leprosy contacts and approximately half of the PB leprosy patients responded to the M. avium protein (Table 2). By contrast, none of the TB patients tested exhibited a positive proliferative response to the M. avium 35-kDa protein (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Proliferation of PBMCs from leprosy and TB patients and healthy leprosy contacts in response to the M. avium and M. leprae 35-kDa proteins

| Group (n) | MLS

|

M. leprae 35-kDa protein

|

M. avium 35-kDa protein

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Positivea | Mean Δcpm (SEM) | % Positive | Mean Δcpm (SEM) | % Positive | Mean Δcpm (SEM) | |

| Contacts (12) | 83 | 28,349 (7,135) | 83 | 19,495 (4,582) | 75 | 13,816 (4,465) |

| PB leprosy patients (18) | 89 | 15,499 (3,938) | 78 | 12,561 (2,193) | 56 | 5,423 (1,444) |

| TB patients (10) | 40 | 8,731 (3,161)b | 20 | 4,995 (2,661) | 0 | 2,242 (780) |

Positive responders are defined as subjects with a net proliferative response of >2,000 cpm and a stimulation index of >4 at 10 μg/ml (MLS and M. leprae 35-kDa protein) or 3 μg/ml (M. avium 35-kDa protein) of antigen.

Differences in the mean proliferative responses between TB and PB leprosy patient groups were compared by Student’s t test and were not significantly different.

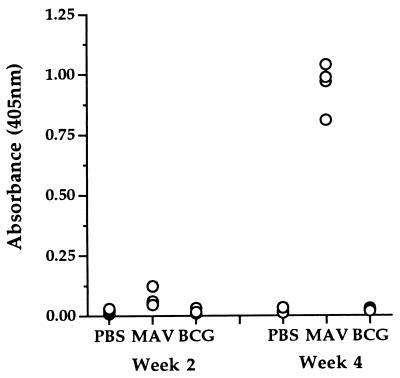

Immune recognition of the M. avium protein in M. avium-infected mice.

To determine if the M. avium 35-kDa protein is recognized during the course of a mycobacterial infection, mice were infected with the virulent MAC101 strain and the level of anti-35 kDa IgG antibodies was determined. The presence of the gene encoding the 35-kDa protein in this strain of M. avium was confirmed by PCR (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 7, all MAC101-immunized mice exhibited high anti-35-kDa IgG antibodies 4 weeks after infection (mean optical density ± standard deviation, 0.951 ± 0.099). These sera were not reactive with M. smegmatis sonicate at the same concentration (optical density of 0.083 ± 0.015), indicating that the reactivity was not directed to any M. smegmatis contaminants in the 35-kDa protein preparation. Furthermore, the immune response was specific, as mice immunized with M. bovis BCG exhibited no detectable antibodies directed against the M. avium 35-kDa protein (Fig. 7). Both M. avium- and M. bovis BCG-immunized mice developed antibodies to crude sonicates of either organism, indicating that both infections had stimulated an antibody response (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Detection of anti-M. avium 35-kDa protein antibodies in sera of M. avium-infected mice. C57BL/6 mice were immunized subcutaneously with PBS, M. bovis BCG CSL (BCG), or M. avium MAC101 (MAV), and the presence of anti-35-kDa antibodies was analyzed by ELISA at 2 and 4 weeks postinfection.

Elicitation of DTH by the M. avium 35-kDa protein.

The ability of the M. avium 35-kDa protein to elicit DTH in mycobacterium-sensitized guinea pigs was assessed. DTH was elicited by the M. avium 35-kDa protein in all M. avium- and M. leprae-sensitized animals tested (Table 3). The magnitude of this response was similar to that elicited by MLS in the same animals. A minority of animals sensitized with M. tuberculosis or M. bovis BCG also responded to the protein, and the level of DTH in the responding animals was comparable to that in M. avium- or M. leprae-sensitized animals. MLS elicited strong DTH in all M. tuberculosis- and M. bovis BCG-sensitized animals.

TABLE 3.

DTH elicited by the M. avium 35-kDa protein in mycobacterium-sensitized guinea pigsa

| Sensitizing organism |

M. leprae sonicate

|

M. avium 35-kDa protein

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. positive/no. tested | Mean induration (mm [range]) | No. positive/no. tested | Mean induration (mm [range]) | |

| Control | 0/4 | 0 | 0/6 | 0 |

| M. avium | 3/3 | 12.8 (12–14) | 3/3 | 11.7 (10–13) |

| M. leprae | 3/3 | 10.7 (10–12) | 3/3 | 10.3 (9–12) |

| M. tuberculosis | 5/5 | 11.4 (10–13) | 2/5 | 9 (0–10) |

| M. bovis BCG | 3/3 | 10.1 (9–11) | 1/3 | 9 (0–9) |

Guinea pigs were sensitized by intradermal injection of 0.5 mg of each mycobacterial species. Intradermal injection of 10 μg of each antigen was used for recall.

DISCUSSION

Characterization of members of the MAC has determined that many of the major antigens are shared with M. leprae and/or M. tuberculosis. These include the 18-kDa heat shock protein (2), the secreted antigen 85B (23), and the highly immunogenic 19-kDa lipoprotein (19). We have extended this list to include the 35-kDa protein of M. leprae, through identification of its M. avium homolog. The two antigens were closely related at the genetic level, showing 82% DNA and 90% amino acid identity. The proteins adopted similar conformation, both forming multimeric complexes of the same size and exhibiting similar serological determinants. The M. avium 35-kDa protein stimulated the proliferation of PBMCs from leprosy-infected and -exposed individuals, indicating that T-cell as well as B-cell epitopes are shared between the M. leprae and M. avium 35-kDa proteins.

The presence of the M. leprae 35-kDa antigen in M. avium indicates that both major membrane proteins (MMP) of M. leprae, MMPI, the 35-kDa protein, and MMPII, a 22-kDa bacterioferritin (25), have well-conserved homologs in M. avium (13). Added to this is the identification of antigens in M. avium which were initially described as M. leprae specific and absent from M. tuberculosis, such as the 12- and 18-kDa proteins (2, 5). This antigenic similarity between M. leprae and the MAC may explain why the ICRC bacillus and Mycobacterium w, organisms classified as belonging to the MAC complex, are being investigated for their antileprosy potential. Both organisms stimulate proliferative responses from the T cells of leprosy patients (7, 40) and evoke lepromin conversion in vaccinated lepromatous patients (4, 33).

Of the mycobacterial antigens isolated and characterized, only a few have identified functions (34, 41). The presence of a well-conserved homolog of the M. leprae 35-kDa protein in M. avium provides one avenue to explore the protein’s function, as it is possible to manipulate genetically members of the MAC (6, 16). Elucidation of the protein’s biological function will also be facilitated by the analogous SrpI of Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 and the P3 protein of S. griseus, both which show striking similarity with the M. avium and M. leprae 35-kDa proteins. The specific function of SrpI is unknown, but it is up-regulated under conditions of sulfur stress and coordinately regulated with SrpG and SrpH, two proteins together capable of cysteine biosynthesis (21, 22). Interestingly, where in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 the srpGHI genes from a tightly clustered operon (22), we found no evidence of adjacent homologs of srpG and srpH genes in M. avium or M. leprae by analysis of sequence around the 35-kDa protein-encoding gene. Furthermore, Southern blotting of chromosomal DNA with srpGH also failed to detect any homologous sequences (data not shown), indicating that these genes are not present in the mycobacteria studied or are too dissimilar to be detected by this technique. Where SrpI is induced under sulfur deprivation, P3 of S. griseus is induced by the deprivation of phosphate (14), suggesting that the 35-kDa protein may be involved in the response of M. avium and M. leprae to conditions of environmental stress, such as the lack of nutrients. Indeed, such conditions are prevalent in the macrophage, the preferred host microenvironment of M. avium and M. leprae. P3 also contains a proposed cyclic nucleotide binding domain between amino acids 100 to 220 (14), which is absent from the 35-kDa protein and SrpI (Fig. 3). Therefore, if P3, SrpI, and the 35-kDa protein do form a set of functionally related proteins spanning three bacterial genera, at least one functional process has been retained by P3 but lost by the other two proteins.

The 35-kDa protein of M. leprae is a major immunogenic antigenic component of the bacillus, recognized by the large majority of leprosy patients and healthy leprosy contacts (37). The recognition of the 35-kDa protein during experimental M. avium infection in mice confirms that the M. avium homolog is also immunogenic. Furthermore, the protein contains T-cell and B-cell epitopes recognized by the human immune response during mycobacterial infection (Table 2; Fig. 6). The gene for the M. avium 35-kDa protein is absent from the genomes of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG, and the protein does not appear to be recognized by TB patients. Although a number of MAC antigens were initially described as MAC specific, these were unable to distinguish between MAC and M. tuberculosis on an immunological basis (1, 8, 15, 17, 19, 20, 28). Such distinction would be of benefit in the early treatment of diseases caused by these organisms, as the currently used skin test reagents for detection of M. avium exposure lack specificity (10). Sensitization with M. avium stimulated a T-cell response to the 35-kDa protein as demonstrated by DTH (Table 3); however, a minority of M. bovis BCG- and M. tuberculosis-sensitized animals also responded to the protein. More extensive studies are required to determine if the M. avium 35-kDa protein can be used to distinguish between M. avium and M. tuberculosis infection in humans.

The rapid detection of MAC infection will be facilitated by the development of new PCR-based methods for the amplification of species-specific fragments. The gene for the M. avium 35-kDa protein offers the opportunity for the specific detection of M. avium infection, as it was detected by PCR in all MAC clinical isolates classified as M. avium. Isolates of M. avium usually account for the majority of MAC infections in AIDS patients, most frequently serovars 1, 4, and 8 (38). All isolates of these three serovars tested were positive for the gene. By contrast, the gene was absent from the one M. intracellulare serovar studied. The lack of other typed M. intracellulare isolates available for testing highlights the paucity of opportunistic infection by this subspecies in AIDS patients (38). The significance of the differential distribution of this gene within the MAC remains to be evaluated, but it is possible that a component of the differences in virulence and biochemistry between M. avium and M. intracellulare (reviewed in reference 13) can be attributed in part to the 35-kDa protein.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. J.A.T. was a recipient of an Australian postgraduate award, N.W. was supported by an INSERM postdoctoral fellowship, and P.W.R. was a recipient of an University of Sydney Medical Foundation research fellowship.

We are grateful for the assistance of C. R. Butlin and the staff and patients of Anandaban Leprosy Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal, which is fully supported by The Leprosy Mission International. We thank B. Gicquel of the Institut Pasteur, Paris, France, for providing plasmid pJN30 and W. Chu, Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia, for providing the typed MAC isolates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe C, Saito H, Tomiako H, Fukasawa Y. Production of a monoclonal antibody specific for Mycobacterium avium and immunological activity of the affinity-purified antigen. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1095–1099. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1095-1099.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Booth R J, Williams D L, Moudgil K D, Noonan L C, Grandison P M, McKee J J, Prestidge R L, Watson J D. Homologs of Mycobacterium leprae 18-kilodalton and Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19-kilodalton antigens in other mycobacteria. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1509–1515. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1509-1515.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coker R J, Hellyer T J, Brown I N, Weber J N. Clinical aspects of mycobacterial infections in HIV infections. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:377–381. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90049-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deo M G, Bapat C V, Bhalero V, Chaturvedi R M, Chulawala R G, Bhatki W S. Anti-leprosy potential of the ICRC vaccine: a study in patients and healthy volunteers. Int J Lepr. 1983;51:540–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshpande R G, Khan M B, Navalkar G. Comparative antigenic analysis of Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) isolates from AIDS patients. Tubercle. 1992;73:356–361. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90040-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foley-Thomas, E. M., D. L. Whipple, L. E. Bermudez, and R. G. Barletta. Phage infection, transfection and transformation of Mycobacterium avium complex and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 141:1173–1181. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gangal S G, Chiplunkar S V, Shinde S R, Samson P D, Deo M G. Immunoreactivity of T-cells from leprosy patients to ICRC and M. leprae antigens before and after vaccination. Trop Med Parasitol. 1990;41:314–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris D P, Vordermeier H M, Brett S J, Pasvol G, Moreno C, Ivanyi J. Epitope specificity and isoforms of the mycobacterial 19-kilodalton antigen. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2963–2972. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2963-2972.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horsburgh C R, Havlik J A, Ellis D A, Kennedy E, Fann S A, Dubois R E, Thompson S E. Survival of patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome and disseminated Mycobacterium avium-complex infections, with and without antimycobacterial chemotherapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:557–559. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.3_Pt_1.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huebner R, Schein M, Cauthen G, Geiter L, Selin M, Good R, O’Brien R. Evaluation of the clinical usefulness of mycobacterial skin test antigens in adults with pulmonary mycobacterioses. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1160–1166. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.5.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter S W, Rivoire B, Mehra V, Bloom B R, Brennan P J. The major native proteins of the leprosy bacillus. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14065–14068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inderlied C B, Kemper C A, Bermudez L E M. The Mycobacterium avium complex. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:266–310. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inglis N F, Stevenson K, Hosie A H, Sharp J M. Complete sequence of the gene encoding the bacterioferritin subunit of Mycobacterium avium subspecies silvaticum. Gene. 1994;150:205–206. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwak, J., and K. E. Kendrick. Unpublished data.

- 15.Mackall J C, Bai G H, Rouse D A, Armoa G R, Chidian F, Nair J, Morris J. A comparison of the T-cell delayed-type hypersensitivity epitopes of the 19 kDa antigens from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium intracellulare using overlapping synthetic peptides. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;93:172–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb07961.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marklund B-I, Speert D P, Stokes R W. Gene replacement through homologous recombination in Mycobacterium intracellulare. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6100–6105. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6100-6105.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris S L, Mackall J C, Malik A, Rouse D A, Chaparas S D. Skin testing with recombinant Mycobacterium intracellulare antigens. Tubercle. 1992;73:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris S L, Rouse D A, Hussong D, Chaparas S D. Isolation and characterization of recombinant lambda gt11 bacteriophages expressing four different Mycobacterium intracellulare antigens. Infect Immun. 1990;58:17–20. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.17-20.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair J, Rouse D A, Morris S L. Nucleotide sequence analysis and serologic characterization of the Mycobacterium intracellulare homologue of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19 kDa antigen. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1431–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nair J, Rouse D A, Morris S L. Nucleotide sequence analysis and serologic characterization of a 27-kilodalton Mycobacterium intracellulare lipoprotein. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1074–1081. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.1074-1081.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson M L, Laudenbach D E. Genes encoded on a cyanobacterial plasmid that are transcriptionally regulated by sulfur availability and CysR. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2143–2150. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2143-2150.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholson M L, Gaasenbeek M, Laundenbach D E. Two enzymes together capable of cysteine biosynthesis are encoded on a cyanobacterial plasmid. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:623–632. doi: 10.1007/BF00290354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohara N, Matsuo K, Yamaguchi R, Yamazaki A, Tasaka H, Yamada T. Cloning and sequencing of the gene for the alpha antigen from Mycobacterium avium and mapping of B-cell epitopes. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1173–1179. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1173-1179.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequences comparisons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pessolani M C V, Smith D R, Rivoire B, McCormick J, Hefta S A, Cole S T, Brennan P J. Purification, characterisation, gene sequence and significance of a bacterioferritin from Mycobacterium leprae. J Exp Med. 1994;180:319–327. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roche P W, Peake P W, Billman-Jacobe H, Doran T, Britton W J. T-cell determinants and antibody binding sites on the major mycobacterial secretory protein MPB59 of Mycobacterium bovis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5319–5326. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5319-5326.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roche P W, Winter N, Triccas J A, Feng C, Britton W J. Expression of Mycobacterium tuberculosis MPT64 in recombinant M. smegmatis: purification, immunogenicity and application to skin tests for tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:226–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouse D A, Morris S L, Karpas A B, Mackall J C, Probst P G, Chaparas S D. Immunological characterization of recombinant antigens isolated from a Mycobacterium avium lambda gt11 expression library by using monoclonal antibody probes. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2595–2600. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2595-2600.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rouse D A, Morris S L, Karpas A B, Probst P G, Chaparas S D. Production, characterization, and species specificity of monoclonal antibodies to Mycobacterium avium complex protein antigens. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1445–1449. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1445-1449.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinha S, Sengupta U, Ramu G, Ivanyi J. Serological survey of leprosy and control subjects by a monoclonal antibody-based immunoassay. Int J Lepr. 1985;53:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snapper C K, Melton R E, Mustapha S, Kieser T, Jacobs W R. Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1990;11:1911–1919. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talwar G P, Zaheer S A, Mukherjee R, Walia R, Misera R S, Sharma A K, Kar H K, Mukherjee R, Pardia S K, Suresh N R, Nair S K, Pandey R M. Immunotherapeutic effects of an anti-leprosy vaccine based on a saprophytic cultivatable mycobacterium, Mycobacterium w, in multibacillary leprosy patients. Vaccine. 1990;8:121–129. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thole J E R, Wieles B, Clark-Curtiss J E, Ottenhoff T H M, Rinke de Wit T F. Immunological and functional characterization of Mycobacterium leprae protein antigens: an overview. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.18050791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timm J, Lim E M, Gicquel B. Escherichia coli-mycobacteria shuttle vectors for operon and gene fusions to lacZ: the pJEM series. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6749–6753. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6749-6753.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timm J, Perilli M G, Duez C, Trias J, Orefici G, Fattorini L, Amicosante G, Oratore A, Joris B, Frere J M, Pugsley A P, Gicquel B. Transcription and expression analysis, using lacZ and phoA gene fusions, of Mycobacterium fortuitum β-lactamase genes cloned from a natural isolate and a high-level β-lactamase producer. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:491–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Triccas J A, Roche P W, Winter N, Feng C G, Butlin C R, Britton W J. A 35-kilodalton protein is a major target of the human immune response to Mycobacterium leprae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5171–5177. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5171-5177.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsang A Y, Denner J C, Brennan P J, McClatchy K. Clinical and epidemiological importance of typing Mycobacterium avium by amplification of 16S rRNA sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;31:2509–2512. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winter N, Triccas J A, Rivoire B, Pessolani M C V, Eiglmeier K, Hunter S W, Brennan P J, Britton W J. Characterization of the gene encoding the immunodominant 35 kDa protein Mycobacterium leprae. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:865–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yadava A, Suresh N R, Zaheer S A, Talwar G P, Mukherjee R. T-cell responses to fractionated antigens of Mycobacterium w, a candidate anti-leprosy vaccine in leprosy patients. Scand J Immunol. 1991;34:23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1991.tb01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young D B, Kaufmann S H E, Hermans P W M, Thole J E R. Mycobacterial protein antigens: a compilation. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:133–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]