Abstract

The management of cancer with alternative approaches is a matter of clinical interest worldwide. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) surgery is a noninvasive technique performed under US or MRI guidance. The most studied therapeutic uses of HIFU involve thermal tissue ablation, demonstrating both palliative and curative potential. However, concurrent mechanical bioeffects also provide opportunities in terms of augmented drug delivery and immunosensitization. The safety and efficacy of HIFU integration with current cancer treatment strategies are being actively investigated in managing primary and secondary tumors, including cancers of the breast, prostate, pancreas, liver, kidney, and bone. Current primary HIFU indications are pain palliation, complete ablation of localized earlystage tumors, or debulking of unresectable late-stage cancers. This review presents the latest HIFU applications, from investigational to clinically approved, in the field of tumor ablation.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Ultrasound–High Intensity Focused (HIFU), Interventional-MSK, Interventional-Body, Oncology, Technology Assessment, Tumor Response, MR Imaging

© RSNA, 2023

Keywords: Ultrasound, Ultrasound–High Intensity Focused (HIFU), Interventional-MSK, Interventional-Body, Oncology, Technology, Assessment, Tumor Response, MR Imaging

Summary

High-intensity focused ultrasound is an investigative but promising technology in the field of oncology, with potential for integration in current curative and palliative cancer treatment strategies.

Essentials

■ High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is an emerging approach to incisionless surgery that combines precise delivery of focused ultrasound (FUS) with MR or US image guidance.

■ Tumoral thermal ablation is currently the most common application of HIFU and is achieved by focusing ultrasound energy to induce a local rise in tissue temperatures greater than 55°C, causing coagulative necrosis within seconds of reaching these elevated temperatures.

■ HIFU surgery is commonly an outpatient procedure that can be repeated, if needed, over the short and long term and can be integrated with existing lines of treatment.

■ In the palliative treatment of bone metastases, HIFU can induce more rapid pain relief compared with radiation therapy, which may require up to 4 weeks to obtain a treatment response.

■ The results of HIFU for the ablation of uterine fibroids are comparable with surgery in terms of symptom reduction, resulting in a substantial improvement in quality of life after 12 months.

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide and presents an enormous socioeconomic challenge in pursuit of more effective integrative treatment strategies (1).

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is an emerging approach to noninvasive therapy combining precise delivery of focused ultrasound (FUS) with MR (MRI-guided FUS, MRgFUS) or US (US-guided FUS, USgFUS) image guidance.

The thermal ablation effect of HIFU has been the most widely explored and is the only mechanism of action that currently has regulatory approval and is commercially available for 32 indications (2). HIFU ablation is obtained by focusing ultrasound energy to induce a local rise in tissue temperatures greater than 55°C, causing coagulative necrosis within seconds of reaching these elevated temperatures. Such effects are obtained with either short or continuous ultrasound pulses over seconds to minutes, with delivered powers ramped up until target temperatures and image-monitored ablation are obtained. Additional mechanical (histotripsy, neuromodulation, drug delivery) and thermal effects (tissue priming to radiation therapy or drug delivery) are under clinical and preclinical investigation (2,3).

Treatment margins with adjacent healthy tissues are sharp because of temperature rises limited to focal spot sizes. Multiple sonications are thus necessary to cover each target lesion, with focal volumes ranging from 0.2 to 5 mm3, depending on transducer geometry, US frequencies, and tissue homogeneity. FUS devices are generally categorized according to their shape and clinical use (2). Extracorporeal transducers, which are available in compact flat, curved, and helmet-like designs, are the most versatile and allow for targeting of both superficial and deep structures that are easily accessible through the skin. Intracorporeal transducers are typically application-specific; transrectal or transurethral transducers are used for genitourinary lesions, while interstitial transducers are used for localized long-term therapy following surgical implantation. Electronic steering allows coverage of large treatment areas without moving the patient and is made possible via phased array transducers, with each element individually adjusted for phase and amplitude.

While image guidance is critical for initial targeting and patient positioning, real-time intraprocedural monitoring is necessary for ablation feedback and thermal dose prescription, which ensure safety and effectiveness. USgFUS transducers incorporate both imaging and therapeutic elements in a stereotactically controlled or handheld device. This enables rapid identification of target lesions and acoustic paths, though with poor quantitative feedback regarding temperatures and ablation necrosis, especially with increasing distances (4).

MRgFUS transducers, which are more expensive and less readily available, are typically embedded in the MRI table of 1.5-T or 3.0-T scanners. The advantages of MRgFUS include higher spatial and tissue contrast resolution for treatment planning and proton resonance frequency shift thermometry for intraprocedural monitoring (5).

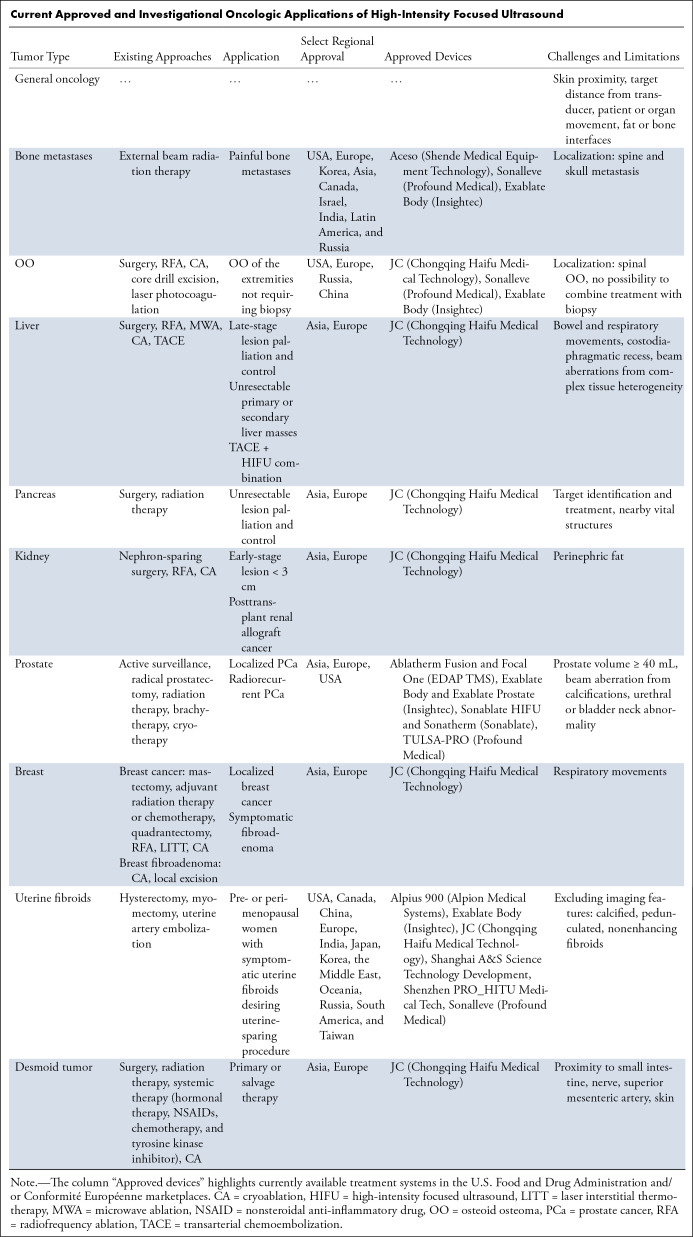

FUS surgery is commonly an incisionless outpatient procedure that can be repeated, if needed, over both short- and long-term periods. FUS can be integrated with existing lines of treatment to augment radio- or chemotherapeutic effects, shrink inaccessible or unresectable lesions, and even replace surgery in patients with suitable lesions or those unfit for major interventions (2,6). Regulatory approval is primarily device manufacturer–specific, with the widest adoption in Asia, followed by approvals in Europe and North America, including the recent expansion of treatment indications from pain palliation to curative ablation (Table).

Current Approved and Investigational Oncologic Applications of High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound

The following review will focus on the clinical applications of HIFU for cancer treatments, from early investigational to more established applications in the field.

HIFU Cancer Ablation

The performance of HIFU cancer ablation generally involves a diverse team of physicists, nurses, radiologic technologists, anesthesiologists, radiologists, and surgeons. The type of anesthesia, ranging from conscious sedation to peripheral, spinal, or general anesthesia, is prescribed according to lesion size, location (considering proximity to skin and bones and moving abdominal organs), patient preference, clinical condition, and procedural experience of the operators (6). Vital signs are monitored throughout the procedure with a stop button available for the patient and operator in case of mistargeting or unpleasant sensations. After proper positioning and application of US coupling gel, images are acquired, regions where ultrasound energy is to be limited (skin, bone, major nerves and vessels, bowels) are manually contoured, and treatment areas are highlighted to cover the lesion and margins. Anatomic fiducials are placed to estimate movement over time and target coregistration. A series of low-power exposures are prescribed to calibrate transducer focusing, and then high-power sonications are ramped up until ablation is obtained. Real-time feedback is monitored by a combination of local tissue thermometry, anatomic changes, and contrast media uptake at MRgFUS, or by lesion hypoechogenicity, color Doppler, and perfused volume evaluation at USgFUS.

Focusing ultrasound on the abdominal cavity presents a challenge in image-guided therapy, as peristaltic, respiratory, and voluntary movements can cause imaging artifacts or mistargeting. To ensure the safety and efficacy of the procedure, a comprehensive approach is adopted, including urinary catheter, bowel preparation, spinal or general anesthesia, and inspiratory phase–gated imaging.

Postablation care comprises neurologic examination and skin burn inspection while recovering from anesthesia, with close follow-up for 2 weeks to assess for severe burns, pain, and out-of-target damage. Pain is treated short term with medication, if needed.

Bone Metastases

One of the most promising applications of HIFU is pain palliation of bone metastases. Pain induced by bone metastases is a common complication in patients with cancer, impairing quality of life (QoL). Currently, external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) represents the standard of care for the palliative and curative treatment of cancer-induced bone pain. However, local radiation therapy is associated with a nonnegligible risk of delayed adverse effects, and about 45% of patients undergoing EBRT do not have substantial improvement in pain (7).

In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved MRgFUS for the palliative treatment of bone pain due to metastatic disease in patients who are unresponsive to standard radiation therapy, ineligible for radiation, or refuse radiation therapy. In these patients, MRgFUS is not used with a curative intent; instead, the overall goal of treatment is to obtain pain palliation, thus reducing patient dependence on opioids or other pain medication.

To date, one or more FUS devices to treat painful bone metastases have been approved in Europe, Korea, Asia, Canada, Israel, India, Latin America, and Russia. Metastases accessible to the US surgery device (ribs, extremities, pelvis, shoulders, or posterior aspects of spinal vertebra below L2) can be targeted; skull and spinal metastases (apart from the posterior elements below the level of the conus medullaris) are excluded because of the risk of injury to the brain and spinal cord. A single session is generally sufficient for treatment, although it can be repeated (8). In the palliative treatment of cancer-induced bone pain, MRgFUS takes advantage of the high ultrasound absorption rate of the bone cortex that causes critical thermal damage to the adjacent periosteum, the most innervated structure of mature bone responsible for pain signal conduction. Two different technical approaches can be used on bone metastases: (a) When the cortical bone is intact, the focus spot is positioned either on the cortical bone surface or behind it, with the ultrasound beam entirely absorbed by the cortex surface on its path toward the medullary cavity; in this approach (wide-beam approach), the amount of energy at the intersection between the ultrasound beam and the bone is not enough to create ablation in any other tissue—a limited amount of energy in bone is sufficient to create a wide area of temperature rise given its high acoustic absorption; or (b) when a bone metastasis features transcortical growth, the ultrasound beam is directly focused on the solid part of the tumor, as with the other soft-tissue targets (9).

MRgFUS can induce more rapid pain relief compared with radiation therapy, which may require up to 4 weeks to obtain a treatment response. In 2014, Hurwitz et al (10) reported the results of a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial of individuals with painful bone metastases nonresponsive to, unsuitable for, or refusing radiation therapy. A pain response was obtained in about two-thirds of patients within a few days after treatment. A more recent prospective nonrandomized phase 2 trial of 198 individuals compared the safety and effectiveness of MRgFUS with EBRT, with a reported response rate (pain reduction equal to or greater than two points from baseline on a numerical rating scale) at 1 month of 91% and 67%, respectively, and complete remission in 43% and 16% of individuals. The pain response was durable at 12 months in 92% of individuals treated with MRgFUS but in only 35% following EBRT (11).

One advantage of MRgFUS in the palliative treatment of bone metastasis is the low potential risk of adverse events. A recent meta-analysis of 799 patients from 26 studies showed overall rates of 0.9% for major adverse events (grade ≥ 3 according to the common terminology criteria for adverse events [CTCAE]) and 5.9% for adverse events with CTCAE grade of 2 or less (12).

Combined treatment with EBRT and MRgFUS is feasible and could have the advantage of obtaining a rapid pain response with MRgFUS while also achieving locoregional tumor control with EBRT. Only one feasibility study assessed the safety of the combined treatment in patients with bone metastases (13).

Unfortunately, there is still a lack of high-quality evidence regarding the role of MRgFUS as a first-line treatment in patients with pain due to bone metastases. An ongoing phase 3 multicenter three-armed randomized controlled trial comparing EBRT, MRgFUS only, or combined EBRT and MRgFUS aims to provide evidence to support the use of MRgFUS as a first-line treatment option, either alone or in combination with EBRT, in clinical guidelines for the treatment of pain due to bone metastases (7).

Bone Tumors

The benefit of MRgFUS in benign bone tumors relies mostly on its noninvasive nature. One of the most promising applications is for the treatment of osteoid osteoma (OO), which accounts for 11% of benign bone tumors. OO usually affects children, adolescents, and young adults. Traditionally, surgical resection has represented the therapeutic standard in patients with OO. Nevertheless, in the last decades, surgery has been largely replaced by image-guided procedures. Among these, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has achieved excellent results in terms of efficacy and safety (14) and currently represents the reference standard therapeutic technique for OO. RFA treatment requires CT guidance and is burdened with risk of complications, including bleeding, infection, skin and muscle burns, nerve injury, and material failure. MRgFUS represents a valuable alternative option to RFA in cases of typical OO that do not require biopsy and was approved by the FDA in 2020 for treating OO of the extremities. MRgFUS for OO was also approved in Europe, Russia, and China. As a noninvasive approach, MRgFUS offers clear advantages in this setting, considering the benign nature of the tumor. Beyond accurate temperature monitoring and the absence of mechanical penetration, another major advantage of MRgFUS in comparison with RFA is the absence of radiation exposure, considering that most patients with OO are children and young adults. The main drawback of MRgFUS is that it cannot be used on all lesion sites. Specifically, it has not received approval for the treatment of spinal lesions, which represent 10% of all cases, because of the theoretical risk of thermal damage to nerve roots. Moreover, in contrast to RFA, MRgFUS treatment cannot be combined with biopsy; however, this represents only a minor limitation considering that in many cases clinical presentation and radiologic features alone are highly suggestive, thus making histologic examination unnecessary before therapy. In the literature, the clinical success rate of MRgFUS for treating OO lies between 87% and 100% (14). One prospective two-center developmental trial reported results at 3 years of 50 participants treated with MRgFUS for nonspinal OO. At final follow-up, a complete clinical response (visual analog scale score 0) was observed in 87% of participants (15). A propensity score–matched study of 116 patients reported comparable efficacy between those treated with RFA versus MRgFUS (16). Considering these promising results and the advantages of MRgFUS over RFA, a comparative study with the actual therapeutic standard is needed to support the clinical use of this technique. In this regard, an ongoing phase 3 trial at the University of California San Francisco and Stanford University was designed to compare the effectiveness of RFA and MRgFUS techniques for OO (17).

Liver

Liver cancer is a major cause of cancer death worldwide, with incidence rates and associated socioeconomic burden predicted to rise in the next decades. At diagnosis, 5-year survival is around 21%, decreasing to 14% and 3.5% in cases of regional and distant spread, respectively, representing half of all cases. While surgery, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), and liver transplantation constitute current standards of therapy, minimally invasive treatments can be used for palliation, curative intent, or downgrading lesions in preparation for more aggressive approaches. HIFU is an emerging technique in the field, comparable in principle to more established approaches like microwave ablation, RFA, and radioembolization for small lesion focal therapy, but further investigation is needed on the premise of safety and integration with existing strategies (18). A known limitation of RFA is the heat sink effect of thermal ablation because of the cooling effect of blood flow on adjacent cancer tissues; however, HIFU-related heating relies less on thermal conduction, enabling coagulative necrosis and cauterization of adjacent capillaries that yield sharper margins with lower risks of bleeding (18). Challenging aspects of HIFU ablation in liver tissues are bowel and respiratory movement, tissue heterogeneity (transitioning from fatty or fibrous to solid tumor), and beam obstruction from the ribs and costodiaphragmatic recess. Reported HIFU complications include self-resolving skin burns and abdominal pain, while severe adverse events include biliary obstruction, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, fistula formation, diaphragmatic rupture, and rib fracture. Although seldom encountered, such events were described mainly in surgically unresectable late-stage tumors with vascular and biliary invasion (18,19).

Currently, HIFU ablation is approved in Asia and Europe primarily for late-stage lesion palliation and control, indicated for unresectable primary and secondary liver masses. A retrospective analysis of 80 unresectable primary and 195 metastatic liver cancers reported objective response rates (comprising complete and partial ablation responses) of 71.8% and 63.7%, respectively, with significant decreases in α-fetoprotein level and pain from baseline (19). In complex cases, small colorectal cancer liver metastases, even if present in high numbers, may be unsuitable even for RFA because of their highly vascularized profile. A phase 1 trial of 13 patients (20) investigated USgFUS in such a population, documenting safe targeting with no severe adverse events, a complete response in 10 patients (absence of intratumoral arterial enhancement), and a partial response in the remaining three. Overall 2-year survival was 77.8%, with nine patients developing new metastases at follow-up with potential for repeated HIFU sessions. A meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials (total sample size: 488) on the integration of HIFU following TACE treatments found improvements in efficacy and 2-year survival rates (odds ratio 3.38 [95% CI: 1.71, 6.66]) compared with TACE alone, presumably because of the synergistic effects of controlled tumoral blood supply and facilitated margin identification with thermal damage (21). Last, a pilot study of individuals with hepatocellular carcinoma waitlisted for liver transplantation employed HIFU as a bridging therapy compared with TACE and best medical treatment (22). Safety and tumor necrosis rates were comparable with TACE, with broader lesion indications for HIFU (including Child-Pugh C), increasing the percentage of patients eligible for bridging therapy from 39.2% to 80.4%.

Pancreas

Despite advances in therapy and early-stage detection, more than 80% of pancreatic cancers are unresectable at diagnosis, with average 5-year survival decreasing from 44% in localized stages to less than 3.5% in advanced stages (23). Available treatment lines comprise partial excision, irreversible electroporation, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or combinations of these, but all treatments are limited by patient performance status. In patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer, HIFU is an investigational approach, although it has been approved in Asia and Europe for tumor ablation or pain palliation via mass control (24). A meta-analysis evaluating 19 studies (one randomized controlled study) with a total of 939 patients for the integration of HIFU with existing treatment protocols (25,26) demonstrated improvements in overall survival (odds ratio at 6 months, 2.31 [95% CI: 1.62, 3.30] and 12 months, 1.76 [95% CI: 1.08, 2.88]) and chronic pain relief (>80% responders), low risk of minor adverse events (skin burns, fever, vomiting, abdominal pain) that resolved in 6 weeks, and rare occurrence of major adverse events requiring hospitalization (portal vein thrombosis, fistulization).

The HIFU procedure acts as a thermal knife for partial or total mass ablation, facilitating systemic or intra-arterial chemotherapy administration, radiotherapeutic targeting in cases of regional spread, or surgical reintervention following FUS debulking. Pain control is complementary following mass reduction; however, palliation in late-stage cancer is achieved by partial ablation, presumably through a mechanism of abdominal pressure relief and thermal damage to nerve endings inactivating celiac plexus fibers.

Combination approaches of HIFU and chemotherapy have been shown to improve survival and QoL compared with chemotherapy alone (25), with US dose escalation to be further investigated for optimizing bulk ablation or, with lower intensities, for drug delivery and tumor immunization (27). Current evidence is limited by small prospective or retrospective studies, although data seem favorable for large randomized clinical trials integrating HIFU for unresectable pancreatic cancers.

Kidney

Incidence of renal cancers has increased over the last 20 years, due in part to behavioral risk factors, but also to earlier (mainly incidental) diagnosis of smaller asymptomatic lesions (28). Two-thirds of tumors at diagnosis are localized, with an expected 93% 5-year survival rate. Treatments are therefore transitioning toward nephron-sparing approaches involving surgery, RFA or microwave ablation, cryoablation, and HIFU (29). Currently, HIFU is an investigational approach but has been approved in Asia and Europe for treatments with ablative and palliative intent via extracorporeal MRgFUS and USgFUS or laparoscopic devices. Early-stage cancers less than 3 cm in diameter are selected for total lesion ablation, as experience suggests comparable safety and efficacy profiles with RFA and cryoablation; however, more comparison studies are needed (29). In cases of tumor recurrence or familial cancers, and to accommodate repeatable therapies despite patient performance status, FUS is a viable noninvasive option for salvage therapy. Additionally, as adapted for late-stage cancers, FUS may also be used for tumor debulking aimed at improving QoL via symptom palliation (flank and back pain, hematuria).

Initial studies using USgFUS demonstrated feasibility of tumor ablation in 17 patients, with loss of postcontrast enhancement and central mass involution in eight cases (30); however, further experience is needed for margin targeting, considering the effects of perinephric fat on attenuation and defocusing following extracorporeal targeting. To overcome these limitations as well as lack of a safe passage for ultrasound waves because of the surrounding rib cage, minimally invasive laparoscopic HIFU devices have been used. The devices achieved homogeneous thermal ablation with low morbidity and ample safety margins from adjacent vital structures (31).

Post–renal transplant patients are three times more likely to develop malignancy because of their inherent clinical condition and immunosuppressed state. Focal therapy is a promising tool for such patients, with localized HIFU treatments performed both in posttransplant kidney and nonkidney cancers (32). The iliac positioning of the renal allograft enables easier and safer targeting, with reduced ultrasound beam aberration because of lower fat interface and skin proximity. A case study (32) investigated the use of US-guided RFA and HIFU in one and two patients, respectively, reporting improvements in the patients’ clinical condition and QoL, no procedural complications, and no lesion recurrence over more than 40 months of follow-up.

Prostate

The current standard of care for localized prostate cancer includes active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, or radiation. While surgery or radiation have the best cancer control outcomes, they are associated with high rates of adverse effects, such as urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction.

The aim of focal therapy is to achieve local tumor control while minimizing adverse effects (33). HIFU is approved by the FDA and European and Asian regulatory agencies for prostate tissue ablation in patients with prostate cancer who are ineligible for surgery or prefer an alternative option. Another application of HIFU is for the treatment of residual or recurrent prostate cancer after radiation therapy.

Multiparametric MRI is the reference standard for the detection, localization, and staging of prostate cancer. Regarding lesion targeting, transurethral and transrectal HIFU, under either MRI or US guidance, demonstrated more promising results compared with extracorporeal HIFU (33). The transurethral approach has several advantages over the transrectal approach, as no thermal energy passes through the rectal wall, thus preserving patient function; transurethral HIFU has been approved for the treatment of the whole and partial gland, not just focal ablation.

The first multicenter phase 2 study conducted by Ehdaie et al (34), including 101 men with prostate adenocarcinoma grade group 2 or 3 visible at MRI treated with transrectal MRgFUS, revealed no evidence of grade group 2 or greater prostate cancer in the treated area in 78 of 89 men at 24-month biopsy and no serious treatment-related adverse events. International Index of Erectile Function-15 (ie, IIEF-15) scores were slightly worse at 24 months than at baseline. By 24 months, no patient had reported urinary incontinence requiring pad use. Another systematic review including 20 case series of 4209 patients with prostate cancer treated with HIFU reported complication rates ranging from 13% to 40%, most of which were classified as minor (Clavien-Dindo grade I–II). Clinically significant in-field recurrence and out-of-field progression were detected in 22% and 29% of patients, respectively. Six months after focal HIFU therapy, 98% of patients were totally continent, and 80% of patients retained sufficient erections for sexual intercourse (35). A propensity score–matched analysis comparing HIFU (n = 188) or cryoablation (n = 48) with robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (n = 472) demonstrated that robot-assisted radical prostatectomy was associated with less continence recovery and lower potency rate 2, 6, and 12 months after surgery (36).

As a salvage therapy in radiorecurrent prostate cancer, HIFU showed 5-year overall and cancer-specific survival rates of 88% and 94.4%, respectively (37).

Breast

HIFU is approved for the treatment of benign and localized malignant breast tumors in Europe and Asia. In both cases, the treatment can be conducted under US or MRI guidance. An advantage of US guidance is that treatment is performed with the patient freely breathing in a comfortable position. MRI guidance has two main advantages over US guidance: (a) better visualization of tumor localization, size, and margins and (b) the possibility to assess temperature increases within the focal point thanks to proton resonance frequency thermometry, although possibly biased by the surrounding fat tissue (38). HIFU can be considered an option to treat symptomatic fibroadenoma in an outpatient setting. A multicentric prospective study conducted by Kovatcheva et al (39) demonstrated a mean volume reduction of 59.2% ± 18.2 [SD] and 72.5% ± 16.7 at 6 and 12 months, respectively, after whole-lesion ablation treatment with HIFU. Similarly, Cavallo Marincola et al (38) revealed a 50% reduction of the maximum diameter of fibroadenoma at 6 months after HIFU. A study conducted by Peek et al (40) investigated the effects of circumferential HIFU treatment around the fibroadenoma, ablating only its circumference and deselecting the center. The aim of circumferential HIFU surgery is to isolate the fibroadenoma from its blood supply, eventually resulting in necrosis of the tumor. Such a strategy led to a volume reduction of 43.2% 12 months after treatment.

As for malignant breast tumors, HIFU could be an option to obtain complete or partial tumor ablation, with the advantage of better cosmetic results, considering the absence of scarring, and less morbidity than traditional surgery. It may be used to treat any residual tumor after chemotherapy or as salvage therapy in case of recurrence after breast conservation therapy. In a systematic review of HIFU for breast cancer treatment, Peek et al (41) performed a histopathologic comparison based on specimens obtained from lumpectomy or mastectomy after HIFU ablative treatment, core-needle biopsy, or a combination of both. The studies showed no residual tumor in 46.2% of patients who underwent surgical treatment after HIFU. However, residual tumor less than 10% of the original lesion volume was found in 29.4% of patients, and residual tumor between 10% and 90% was found in 22.7%. USgFUS, although less commonly reported, revealed better results than MRgFUS; this is possibly due to wider treatment margins, approximated to 1.5–2 cm with USgFUS compared with more narrow margins of 0–1.5 cm as generally followed with MRgFUS. Regarding coagulative necrosis, 31 of 38 patients showed absence of contrast at the index tumor nodule and a thin rim of enhancement at the periphery after HIFU treatment. Only minor complications, such as regional edema and tenderness, skin burn, hyperpigmentation, and swelling or hardness of the area, were reported in a few patients. Cosmetic results were good to excellent in 25 of 27 patients and acceptable in the other two. However, the cosmetic outcome could not be evaluated in most of the studies because HIFU treatment was mostly followed by surgical resection (41).

For HIFU therapy to be comparable to surgical resection, HIFU should achieve complete tumor necrosis. Recent studies showed that complete tumor necrosis is achieved in 20% to 100% of patients. One of the main problems is the evaluation of proper ablation margins, which is key for long-term survival and local recurrence. However, neither MRI nor diagnostic US has satisfactory sensitivity for such precise visualization, although MRI yields more reproducible results. Another limitation is the need to proceed with axillary lymph node dissection in the case of positive findings from sentinel lymph node biopsy, contrasting with the noninvasiveness of HIFU therapy (42). HIFU may additionally serve as a nonablative treatment for breast cancer to induce systemic effects. Recent clinical trials revealed the potential of HIFU as an adjuvant to elicit proinflammatory immune responses in combination with immunotherapy and chemotherapy (43).

Uterine Fibroids

The treatment of uterine fibroids is the most widely approved application of HIFU in gynecology. Uterine fibroids are the most common gynecologic benign tumor in women of reproductive age and occur in about 70% of the female population. MRgFUS was approved by the FDA in 2004 for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids in pre- or perimenopausal women who desire to preserve the uterus (44).

A recently published meta-analysis (45) demonstrated that the results of MRgFUS are comparable to surgery in terms of symptom reduction, resulting in a significant improvement of QoL after 12 months (mean difference, 2.25 [95% CI: 1.15, 3.35]). While uterine artery embolization (UAE) has advantages in reducing symptoms and improving QoL in comparison with MRgFUS, it is associated with a longer hospital stay after treatment and a higher risk of major complications. MRgFUS also appears to be associated with a higher postoperative pregnancy rate and shorter pregnancy interval after treatment compared with UAE, with little effect on endometrial receptivity and ovarian function. On the contrary, the desire for future pregnancy is a relative contraindication to UAE in professional society guidelines (45). One limitation of MRgFUS is the relatively high reintervention rate as compared with surgery and UAE; a retrospective study with long follow-up periods (mean 63.5 months) reported an overall reintervention rate of 33.3% after MRgFUS. Interestingly, the risk of reintervention was negatively associated with the percentage of nonperfused volume ratio after treatment; hence, selecting fibroids in which complete ablation is achievable could decrease the risk of reintervention (46).

Currently, no data are available from comparative randomized trials with a long follow-up period. For this purpose, an ongoing national multicenter randomized trial in the Netherlands is enrolling premenopausal women, with the aim to evaluate the long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness of MRgFUS in comparison with other treatment options for fibroids (hysterectomy, myomectomy, or UAE) (47).

Soft Tissue

Among soft-tissue tumors, desmoid fibromatosis has been most extensively investigated clinically. Desmoid tumors are benign, locally aggressive mesenchymal neoplasms with a high rate of recurrence even after surgical resection with negative margins. HIFU is approved in Asia and Europe for the ablation of desmoid tumors. One of the largest studies was conducted by Zhang et al (48), which included 111 patients with 145 desmoid tumors treated with USgFUS. The median nonperfused volume ratio was 84.9%, and the tumor volume reduction rate was 36.1% ± 4.2 at 3 months after treatment. The incidence rate of adverse events (CTCAE grade 1, 2, or 3) was 30.9%. No CTCAE grade 4–5 adverse events occurred. The most commonly reported events were first- or second-degree skin burns and mild pain in the region of treatment or in the innervation region. One patient reported a brachial plexus injury with a permanent deficit (48). In a study by Ghanouni et al (49), 15 patients with extra-abdominal desmoid tumors treated with MRgFUS showed a median reduction of 63% of the viable targeted tumor volume and a median reduction of 58% of the viable total tumor volume immediately after the initial MRgFUS treatment. In another study by Yang et al (50), 15 patients with unresectable and recurrent symptomatic intra-abdominal desmoid tumors treated with HIFU showed a mean nonperfused volume ratio of 71.7% after treatment. Moreover, three patients followed up for more than 4 years showed no tumor progression, while before HIFU treatment, they had undergone one to three radical surgeries in the prior 3 years. The other 12 patients had no evidence of tumor progression or recurrence during a follow-up of 32 months, with a mean tumor recurrence time of 14 months before HIFU treatment.

Brain Tumors

In the last decades, one of the most promising applications of FUS has been for pathologic brain conditions. With technological developments, the hemispheric distribution of phased arrays and concave focusing has resolved the issue of ultrasound wave distortion at the skull interface, allowing for the application of MRgFUS for the treatment of brain tumors without the need of craniotomy (2,3). The first neurosurgical trial using noninvasive transcranial MRI-guided HIFU occurred in 2010. Although thermal ablation of brain tumors using high-intensity MRgFUS showed initial promise, it was abandoned because of the limited treatment envelope and the long time required to ablate a substantial tumor volume (51). Low-intensity FUS, in conjunction with intravenously administered microbubbles, has recently emerged as an effective approach to reversibly disrupt the blood-brain barrier, favoring the delivery of chemotherapeutic agents in targeted brain areas. As a matter of fact, due to the heterogeneous blood-brain barrier permeability of tumors, the penetration of these agents is largely unpredictable. Several preclinical and a few clinical trials have investigated the safety and efficacy of low-intensity FUS with microbubbles for blood-brain barrier disruption in glioma and cerebral metastases. Several efforts, however, remain in establishing the parameters for safe FUS for blood-brain barrier disruption (52).

Conclusion and Future Directions

In oncology, HIFU for either thermal or mechanical effects is still widely considered an investigative technology with promising potential for integration in current cancer treatment strategies, both curative and palliative. Few stage-specific ablative applications are globally approved, while a rising number of tailored approaches are being studied that aim to improve symptoms, control benign and malignant tumor growth, decrease lesion bulk to meet surgical eligibility, and augment the efficacy of parallel treatments for radiosensitization, immunization, and drug delivery. Most organs appear amenable to HIFU thermal ablation; however, noninvasive brain tumor targeting remains a challenge. To address such limitations (2,3), low-intensity FUS is being investigated in both preclinical and clinical settings for localized drug delivery, immunomodulation, and neuromodulation to the brain and spinal cord. Encouraging oncologic applications of HIFU bioeffects are liquid biopsy (to promote the release of cancer biomarkers), clot lysis, and targeted vascular occlusion. As safety and efficacy studies are performed worldwide, routine adoption of HIFU treatments must continue to be closely monitored for clinical outcomes, niche stage- and patient-specific applications, and integration with concurrent therapies, while continuing to improve and expand FUS-mediated biologic applications.

Authors declared no funding for this work.

Disclosures of conflicts of interest: A.D.M. No relevant relationships. G.A. No relevant relationships. M.M. No relevant relationships. P.G. Clinical trial grant support from Insightec; consulting fees from HistoSonics; support from Focused Ultrasound Foundation for attending meetings and/or travel; participation on advisory boards for SonALASense and Profound Medical; stockholder in SonALASense. A.N. Grant from the European Union’s 2020 Research and Innovation Program (grant no. 825859).

Abbreviations:

- CTCAE

- common terminology criteria for adverse events

- EBRT

- external beam radiation therapy

- FDA

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- FUS

- focused ultrasound

- HIFU

- high-intensity FUS

- MRgFUS

- MRI-guided FUS

- OO

- osteoid osteoma

- QoL

- quality of life

- RFA

- radiofrequency ablation

- TACE

- transarterial chemoembolization

- UAE

- uterine artery embolization

- USgFUS

- US-guided FUS

References

- 1. Mattiuzzi C , Lippi G . Current cancer epidemiology . J Epidemiol Glob Health 2019. ; 9 ( 4 ): 217 – 222 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siedek F , Yeo SY , Heijman E , et al . Magnetic resonance-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound (MR-HIFU): technical background and overview of current clinical applications (part 1) . Rofo 2019. ; 191 ( 6 ): 522 – 530 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Medel R , Monteith SJ , Elias WJ , et al . Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery: Part 2: A review of current and future applications . Neurosurgery 2012. ; 71 ( 4 ): 755 – 763 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fan HJ , Zhang C , Lei HT , et al . Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of uterine fibroids . Medicine (Baltimore) 2019. ; 98 ( 10 ): e14566 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blackwell J , Kraśny MJ , O’Brien A , et al . Proton resonance frequency shift thermometry: a review of modern clinical practices . J Magn Reson Imaging 2022. ; 55 ( 2 ): 389 – 403 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelekis A . Radiation therapy castle under siege: Will it hold or fold? Radiology 2023. ; 307 ( 2 ): e222944 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Slotman DJ , Bartels MMTJ , Ferrer CJ , et al. ; FURTHER consortium . Focused Ultrasound and RadioTHERapy for non-invasive palliative pain treatment in patients with bone metastasis: a study protocol for the three armed randomized controlled FURTHER trial . Trials 2022. ; 23 ( 1 ): 1061 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huisman M , ter Haar G , Napoli A , et al . International consensus on use of focused ultrasound for painful bone metastases: Current status and future directions . Int J Hyperthermia 2015. ; 31 ( 3 ): 251 – 259 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scipione R , Anzidei M , Bazzocchi A , Gagliardo C , Catalano C , Napoli A . HIFU for bone metastases and other musculoskeletal applications . Semin Intervent Radiol 2018. ; 35 ( 4 ): 261 – 267 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hurwitz MD , Ghanouni P , Kanaev SV , et al . Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound for patients with painful bone metastases: phase III trial results . J Natl Cancer Inst 2014. ; 106 ( 5 ): dju082 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Napoli A , De Maio A , Alfieri G , et al . Focused ultrasound and external beam radiation therapy for painful bone metastases: A phase II clinical trial . Radiology 2023. ; 307 ( 2 ): e211857 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baal JD , Chen WC , Baal U , et al . Efficacy and safety of magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound for the treatment of painful bone metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Skeletal Radiol 2021. ; 50 ( 12 ): 2459 – 2469 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bartels MMTJ , Verpalen IM , Ferrer CJ , et al . Combining radiotherapy and focused ultrasound for pain palliation of cancer induced bone pain; a stage I/IIa study according to the IDEAL framework . Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2021. ; 27 : 57 – 63 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parmeggiani A , Martella C , Ceccarelli L , Miceli M , Spinnato P , Facchini G . Osteoid osteoma: which is the best mininvasive treatment option? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2021. ; 31 ( 8 ): 1611 – 1624 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Napoli A , Bazzocchi A , Scipione R , et al . Noninvasive therapy for osteoid osteoma: a prospective developmental study with MR imaging-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound . Radiology 2017. ; 285 ( 1 ): 186 – 196 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arrigoni F , Spiliopoulos S , de Cataldo C , et al . A bicentric propensity score matched study comparing percutaneous computed tomography-guided radiofrequency ablation to magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound for the treatment of osteoid osteoma . J Vasc Interv Radiol 2021. ; 32 ( 7 ): 1044 – 1051 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Comparative Effectiveness of MRgFUS Versus CTgRFA for Osteoid Osteomas . ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02923011. Accessed April 11, 2023.

- 18. Zou YW , Ren ZG , Sun Y , et al . The latest research progress on minimally invasive treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma . Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2023. ; 22 ( 1 ): 54 – 63 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ji Y , Zhu J , Zhu L , Zhu Y , Zhao H . High-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for unresectable primary and metastatic liver cancer: real-world research in a Chinese tertiary center with 275 cases . Front Oncol 2020. ; 10 : 519164 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang T , Ng DM , Du N , et al . HIFU for the treatment of difficult colorectal liver metastases with unsuitable indications for resection and radiofrequency ablation: a phase I clinical trial . Surg Endosc 2021. ; 35 ( 5 ): 2306 – 2315 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu J , Mao H , He Y . Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of high-intensity focused ultrasound combined with transarterial chemoembolization and transarterial chemoembolization alone in the treatment of liver cancer . Transl Cancer Res 2022. ; 11 ( 6 ): 1678 – 1688 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chok KSH , Cheung TT , Lo RCL , et al . Pilot study of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation as a bridging therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma patients wait-listed for liver transplantation . Liver Transpl 2014. ; 20 ( 8 ): 912 – 921 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu JX , Zhao CF , Chen WB , et al . Pancreatic cancer: A review of epidemiology, trend, and risk factors . World J Gastroenterol 2021. ; 27 ( 27 ): 4298 – 4321 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sofuni A , Asai Y , Mukai S , Yamamoto K , Itoi T . High-intensity focused ultrasound therapy for pancreatic cancer . J Med Ultrason (2001) 2022. ; 01208 - 4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guo J , Wang Y , Chen J , Qiu W , Chen W . Systematic review and trial sequential analysis of high-intensity focused ultrasound combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy in the treatment of unresectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma . Int J Hyperthermia 2021. ; 38 ( 1 ): 1375 – 1383 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fergadi MP , Magouliotis DE , Rountas C , et al . A meta-analysis evaluating the role of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) as a fourth treatment modality for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer . Abdom Radiol (NY) 2022. ; 47 ( 1 ): 254 – 264 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee JY , Oh DY , Lee KH , et al . Combination of chemotherapy and focused ultrasound for the treatment of unresectable pancreatic cancer: a proof-of-concept study . Eur Radiol 2023. ; 33 ( 4 ): 2620 – 2628 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Padala SA , Barsouk A , Thandra KC , et al . Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma . World J Oncol 2020. ; 11 ( 3 ): 79 – 87 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Panzone J , Byler T , Bratslavsky G , Goldberg H . Applications of focused ultrasound in the treatment of genitourinary cancers . Cancers (Basel) 2022. ; 14 ( 6 ): 1536 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ritchie RW , Leslie T , Phillips R , et al . Extracorporeal high intensity focused ultrasound for renal tumours: a 3-year follow-up . BJU Int 2010. ; 106 ( 7 ): 1004 – 1009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ritchie RW , Leslie TA , Turner GDH , et al . Laparoscopic high-intensity focused ultrasound for renal tumours: a proof of concept study . BJU Int 2011. ; 107 ( 8 ): 1290 – 1296 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Di Candio G , Porcelli F , Campatelli A , Guadagni S , Vistoli F , Morelli L . High-intensity focused ultrasonography and radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma arisen in transplanted kidneys: single-center experience with long-term follow-up and review of literature . J Ultrasound Med 2019. ; 38 ( 9 ): 2507 – 2513 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Napoli A , Alfieri G , Scipione R , et al . High-intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer . Expert Rev Med Devices 2020. ; 17 ( 5 ): 427 – 433 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ehdaie B , Tempany CM , Holland F , et al . MRI-guided focused ultrasound focal therapy for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: a phase 2b, multicentre study . Lancet Oncol 2022. ; 23 ( 7 ): 910 – 918 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bakavicius A , Marra G , Macek P , et al . Available evidence on HIFU for focal treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review . Int Braz J Urol 2022. ; 48 ( 2 ): 263 – 274 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garcia-Barreras S , Sanchez-Salas R , Sivaraman A , et al . Comparative analysis of partial gland ablation and radical prostatectomy to treat low and intermediate risk prostate cancer: oncologic and functional outcomes . J Urol 2018. ; 199 ( 1 ): 140 – 146 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Siddiqui KM , Billia M , Arifin A , Li F , Violette P , Chin JL . Pathological, oncologic and functional outcomes of a prospective registry of salvage high intensity focused ultrasound ablation for radiorecurrent prostate cancer . J Urol 2017. ; 197 ( 1 ): 97 – 102 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cavallo Marincola B , Pediconi F , Anzidei M , et al . High-intensity focused ultrasound in breast pathology: non-invasive treatment of benign and malignant lesions . Expert Rev Med Devices 2015. ; 12 ( 2 ): 191 – 199 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kovatcheva R , Guglielmina JN , Abehsera M , Boulanger L , Laurent N , Poncelet E . Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment of breast fibroadenoma-a multicenter experience . J Ther Ultrasound 2015. ; 3 ( 1 ): 1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peek MCL , Ahmed M , Scudder J , et al. ; HIFU-F Collaborators . High-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of breast fibroadenomata (HIFU-F trial) . Int J Hyperthermia 2018. ; 34 ( 7 ): 1002 – 1009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Peek MCL , Ahmed M , Napoli A , et al . Systematic review of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation in the treatment of breast cancer . Br J Surg 2015. ; 102 ( 8 ): 873 – 882 ; discussion 882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zulkifli D , Manan HA , Yahya N , Hamid HA . The applications of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablative therapy in the treatment of primary breast cancer: a systematic review . Diagnostics (Basel) 2023. ; 13 ( 15 ): 2595 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dahan M , Cortet M , Lafon C , Padilla F . Combination of focused ultrasound, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy: new perspectives in breast cancer therapy . J Ultrasound Med 2023. ; 42 ( 3 ): 559 – 573 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Napoli A , Alfieri G , Andrani F , et al . Uterine myomas: focused ultrasound surgery . Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2021. ; 42 ( 1 ): 25 – 36 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yan L , Huang H , Lin J , Yu R . High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for symptomatic uterine fibroids: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Int J Hyperthermia 2022. ; 39 ( 1 ): 230 – 238 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Verpalen IM , de Boer JP , Linstra M , et al . The Focused Ultrasound Myoma Outcome Study (FUMOS); a retrospective cohort study on long-term outcomes of MR-HIFU therapy . Eur Radiol 2020. ; 30 ( 5 ): 2473 – 2482 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Anneveldt KJ , Nijholt IM , Schutte JM , et al . Comparison of (Cost-)Effectiveness of Magnetic Resonance Image-Guided High-Intensity-Focused Ultrasound With Standard (Minimally) Invasive Fibroid Treatments: Protocol for a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (MYCHOICE) . JMIR Res Protoc 2021. ; 10 ( 11 ): e29467 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang R , Chen JY , Zhang L , et al . The safety and ablation efficacy of ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for desmoid tumors . Int J Hyperthermia 2021. ; 38 ( 2 ): 89 – 95 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ghanouni P , Dobrotwir A , Bazzocchi A , et al . Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound treatment of extra-abdominal desmoid tumors: a retrospective multicenter study . Eur Radiol 2017. ; 27 ( 2 ): 732 – 740 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang Y , Zhang J , Pan Y . Management of unresectable and recurrent intra-abdominal desmoid tumors treated with ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound: A retrospective single-center study . Medicine (Baltimore) 2022. ; 101 ( 34 ): e30201 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bunevicius A , McDannold NJ , Golby AJ . Focused ultrasound strategies for brain tumor therapy . Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2020. ; 19 ( 1 ): 9 – 18 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gorick CM , Breza VR , Nowak KM , et al . Applications of focused ultrasound-mediated blood-brain barrier opening . Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2022. ; 191 : 114583 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]