Abstract

Repeated claims that a dwindling supply of potential caregivers is creating a crisis in care for the U.S. aging population have not been well-grounded in empirical research. Concerns about the supply of family care do not adequately recognize factors that may modify the availability and willingness of family and friends to provide care to older persons in need of assistance or the increasing heterogeneity of the older population. In this paper, we set forth a framework that places family caregiving in the context of older adults’ care needs, the alternatives available to them, and the outcomes of that care. We focus on care networks, rather than individuals, and discuss the demographic and social changes that may alter the formation of care networks in the future. Last, we identify research areas to prioritize in order to better support planning efforts to care for the aging U.S. population.

Keywords: Caregiving, Demography, Family issues, Well-being

For decades, warnings have abounded that the aging of the U.S. population would bring dire consequences for society, including a crisis in late-life care. Concerns stem in part from anticipated increases in the number of older adults surviving to very old ages alongside changes in U.S. families portending weaker family ties. The impending decline in the ratio of potential caregivers (aged 45–64) to the number of adults aged 80 and older (Redfoot et al., 2013) is often cited as evidence of a looming family care shortfall needing urgent attention (Gaugler, 2021).

More measured speculations have also been offered about the future of family caregiving. Freedman and Wolff (2020) suggest that countervailing demographic forces, such as spouses and partners living longer, may partially mitigate concerns. Similarly, Spillman and colleagues (2020) note that as the proportion of older adults without spouses or children grows, reliance upon other relatives and nonrelatives may increase. In addition, the increasing diversity of families over the next 20 years may produce a shift in who is called upon to assist older adults.

Much is left to be understood about the changing demography of family caregiving, especially as it relates to the aging of the large Baby Boom generation, which will begin to reach age 80 in 2026. Recently, we formed a national network of family demographers and caregiving experts to better understand impending changes in the demography of family caregiving. We argue that claims of a crisis in caregiving attributable to declines in the supply of potential family caregivers have not adequately recognized demographic and social changes that may modify the availability and willingness of family and friends to provide care.

Our assessment complements prior reviews (e.g., Carr & Utz, 2020; Harvath et al., 2020; Schulz & Eden, 2016; Spillman et al., 2020), which have drawn attention to caregiving heterogeneity, care trajectories, technological advancements, and the care needs of older adults without close kin. We advance the field by outlining a framework to systematically understand the changing demography of family caregiving in the context of shifts in other demographic and social phenomena linked to caregiving. Focusing on the U.S. context over the last decade, we link this evidence to a future research agenda that will foster a deeper understanding of the changing demography of late-life family caregiving.

Framework

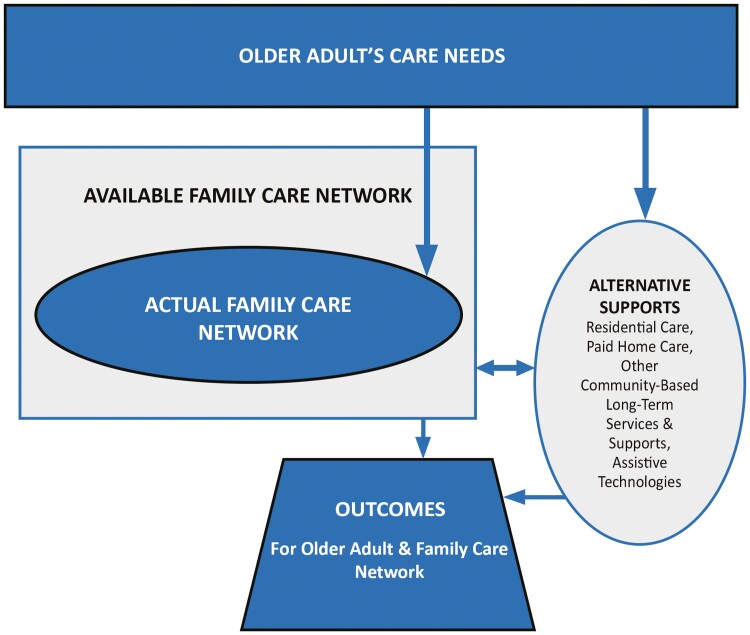

Figure 1 illustrates linkages among an older adult’s care needs, available and actual family care networks, and outcomes for older adults and their support networks. In this context, “care needs” are defined broadly to include physical self-care, mobility, household chores, medical care tasks, transportation, and emotional support; “family care network” refers to family members and unpaid nonrelatives who could potentially or do actually provide care. Because two thirds of older adults with care needs receive assistance from multiple caregivers (Kasper et al., 2015)—irrespective of family size (Reyes et al., 2021)—we focus on the care network, rather than individual caregivers.

Figure 1.

Framework to assess the changing demography of late-life family caregiving.

The framework recognizes the central role of older adults’ care needs, which are shaped by both demographic and health-related processes that intersect in specific environments over the life course. The centerpiece of the framework distinguishes available from actual family care. That is, demographic phenomenon related to family availability may be distinguished from social forces shaping actual care. The framework also specifies that there are alternative options for meeting care needs, including residential care, paid home care, other community-based long-term services and supports, and assistive technologies. The older adult’s evolving care needs and available options yield a set of actual care arrangements that drive outcomes over time for both those receiving and providing assistance.

Although not explicit in the diagram, the proposed framework depicts a set of inherently dynamic processes that are influenced by the macroenvironment. For instance, tasks taken on by family caregivers may shift as health care policies, technologies, and norms change (Wolff et al., 2016). Decisions about how to balance family care with alternatives support may also be influenced over time by changes in family, economic, and policy contexts (Willink et al., 2017). Moreover, we recognize that macrolevel factors may influence the relationships depicted in the figure in different ways for families who have been disadvantaged by structural racism and other forms of systemic inequities.

Demographic Forces Influencing Available Family Caregivers

Our first premise is that the United States has experienced profound demographic changes, which affect the size and composition of older adults’ available family care networks. Here we consider recent and impending changes in five demographic phenomena—marriage; partnering; fertility and family size; stepfamilies; and kinlessness—with implications for late-life family caregiving. Where published estimates are not available, we draw upon the 2020 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) to characterize the family demography of adults aged 70 and older in the United States (see Freedman & Kasper, 2019; Supplementary Material).

Marriage

Spouses and partners are often the first family members to assist an older adult in need of care. The percentage of older adults who are married has been increasing slowly over time (Wang, 2018), as mortality rates at older ages have declined (through 2020). In 2020, half of adults aged 70 and older were married (authors’ NHATS tabulations); among those who were unmarried, a larger share was widowed (59%) than separated/divorced (29%). For younger cohorts, a larger share of the unmarried are divorced, implying that future cohorts of older adults will have more complex marital histories. Unmarried adults from the Baby Boom generation are disproportionately women from minoritized racial groups and are less likely than married older adults to have a college education (Lin & Brown, 2012).

Partnering

Not all unmarried older adults are unpartnered. The number of cohabiting adults aged 50 and older has quadrupled since 2000 (Stepler, 2017), and 3% of those aged 70 and older cohabit (authors’ NHATS tabulations). The national legalization of same-sex marriage in 2015 foretells an increase of same-sex older married couples (Umberson et al., 2018), who have broader social networks and are more likely than different-sex couples to receive care from nonrelatives (Knauer, 2016; Reczek, 2020). Living-apart-together—that is, in a committed romantic relationship but living separately—is recognized as an alternative to cohabitation in midlife (Brown et al., 2022), but estimates for U.S. adults aged 65 and older are limited (Lewin, 2017).

Fertility and family size

Adult children and their partners—and especially women—have long been the mainstays of family caregiving, particularly for unpartnered older adults with care needs. Yet for decades women have been both delaying childbearing and having fewer total births. The rise in mean age at first birth—from 21 in 1970 to 24 in 1995 and 27 in 2020 (Matthews & Hamilton, 2002; Osterman et al., 2022)—means that on average, a 52-year-old woman in 2022 had a 73-year-old mother, a 28-year-old adult child, and possibly a new grandchild (Freedman & Wolff, 2020), although—given declines in marriage among younger generations (Wang, 2018)—not necessarily a child-in-law. Men and women aged 70 and older in 2020 had an average of 2.4 living biological children (including 11% with no biological children; authors’ NHATS tabulations). However, over the next decade, women will reach ages 70–74 with substantially fewer biological children (Guzzo & Schweizer, 2020). Together these trends mean that individuals with aging parents will have fewer siblings on average with whom to share care responsibilities and, for a growing percentage of older adults, the family will not include biological children. Among men and women with more than one child, multiple-partner fertility is common and increasing, resulting in more families with half-siblings (Guzzo, 2014).

Stepfamilies

High rates of divorce and remarriage in prior decades have led to a rising number of older adults with stepchildren. Estimates of older adults with stepchildren vary: about 16% of adults aged 70 and older report having at least one stepchild (authors’ NHATS tabulations); the figure is 41% for couples with one partner at least aged 50 or older (Lin et al., 2018). Such variation is likely related to use of different methods to identify stepchildren and to differing age groups. Irrespective of current estimates, being part of a stepfamily is more common for some groups (e.g., Black older adults, adult children without a college degree; Lin et al., 2018; Seltzer, 2019), and the percentage of older adults with stepchildren is expected to rise in coming decades. Parents in stepfamilies are less likely than those in biological families to receive help (broadly defined) from adult children (Wiemers et al., 2019) and to receive care when needed (Patterson et al., 2022); however, family ties are not uniformly weaker in all types of stepfamilies (Lin et al., 2022; Schoeni et al., 2022).

Kinlessness

Although few older adults are truly kinless—with no living family of any kind—a growing proportion lack a living spouse and children (Margolis & Verdery, 2017). Among adults aged 70 and older, about 5% have no spouse or partner and no children of any type (authors’ NHATS tabulations). Verdery and Margolis (2017) find that Black older adults are more likely than White older adults to be unpartnered with no children, a gap they project will widen over the next few decades. Outside the United States, kinless older adults often turn to other relatives (e.g., grandchildren, siblings) and friends when care needs arise (Mair, 2019), but recent U.S.-focused studies of care provided to kinless older adults are lacking.

Additional Social Factors Affecting Actual Care Networks

Our second premise is that the United States is experiencing changes in key social factors likely to shape participation of family and friends in older adults’ care networks. Here we consider recent and impending changes in proximity and living arrangements; the nature of work and care; competing demands from children and grandchildren; intergenerational relationships; and gendered attitudes and expectations about the caregiving role.

Proximity and living arrangements

Geographic moves within the United States have declined substantially in recent decades (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Moreover, long-run declines in intergenerational coresidence—often meant to address the younger generation’s economic needs (Kahn et al., 2013)—have begun to reverse (Pilkauskas et al., 2020). Consequently, the majority of adults aged 65 and older live with (15%–20%) or within 10 miles of (45%–50%) an adult child (Raymo et al., 2019). Black and Hispanic older adults and those with less than a college degree—subgroups more likely to need late-life care—are more likely to live with or near adult children (Choi et al., 2020; Reyes et al., 2020). Unmarried adult children—a group increasing as marriage rates decline—and biological (versus step) children are more likely to live with a parent (Reyes et al., 2020; Seltzer et al., 2013). Amounts of assistance also vary by proximity, with those living very close providing more substantial amounts of assistance to older parents (Schoeni et al., 2021).

The nature of work and care

About half of family and unpaid caregivers to older adults are employed (Freedman & Wolff, 2020), a trend that has been increasing among spousal caregivers (Wolff et al., 2018). For women, caregiving has been associated with reduced labor force participation and retirement (Van Houtven et al., 2013), and changes in incentives (or, in the case of some public benefits, requirements) to work may in turn influence caregiving (Mommaerts & Truskinovsky, 2020). Caregiving leave policies and flexible work arrangements may facilitate combining work and caregiving (Jacobs, 2020; Saad-Lessler, 2020). In 2017, 4 in 10 workers had access to paid caregiving leave, 57% had scheduling flexibility, and 29% could work from home (Jacobs, 2020). Job flexibility increased during the pandemic and is expected to remain elevated (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022), but access remains limited for low-income workers.

Caring for parents and raising children and grandchildren

Because of shifts in longevity and the timing of births, the proportion of midlife adults who have two or three other living generations has increased (Margolis & Wright, 2017; Wiemers & Bianchi, 2015). Consequently, “sandwich caregiving”—providing care to a parent and grown child(ren) in midlife (about 18%; Friedman et al., 2017)—and “double-decker sandwich caregiving”—providing care to a parent and grandchild (about 10%; Margolis & Wright, 2017)—are both expected to increase. The implications of these shifts are not clear. Although sandwich caregiving may reduce the time available to assist a parent, providing grandchild care in midlife may increase the chances of receiving care from an adult child later in life (Bui et al., 2022).

Intergenerational relationships

Parents and adult children often provide a safety net for each other, providing emotional and material support, including care (Seltzer & Bianchi, 2013). Some families face discord that may interfere with care provision. For instance, partnership dissolution and repartnering may disrupt family ties, reducing contact or leading to estrangement, particularly for fathers (Lin et al., 2022; Reczek et al., 2022). Yet, the Baby Boom generation appears to have especially strong ties with their adult children (Fingerman et al., 2012) and support for coresidence between older parents and adult children has increased (Patterson & Reyes, 2022).

Gendered preferences and attitudes about caregiving

Wives and daughters have historically been more likely than husbands and sons to take on caregiving responsibilities. Although the gender gap has been slowly decreasing over time as more men assume this role (Wolff et al., 2018), substantial gender inequalities persist for some groups, including Black family caregivers (Cohen et al., 2019). Attitudes are also evolving as adult children of the Baby Boom generation become caregivers. Nearly 60% of Americans say that men and women would do about equally as good a job caring for a seriously ill family member (Horowitz et al., 2017). Similarly, about 90% of men and women believe in an equal division of caregiving labor, and about half of men and women expect to take time off work for caregiving (Schulte, 2021). These findings suggest that men may be more likely in the future to provide care to older adults.

Linking Demographic and Social Changes to Care Recipient and Caregiver Well-Being

Only a few studies have linked family care network characteristics to care-related outcomes for older adults or those who provide care. Patterson and colleagues (2022) found that older parents in stepfamilies are less likely than older parents in nonstepfamilies to receive assistance from children, but they are no more likely to report unmet care needs. Other studies indicate that care-related disagreements with stepfamily members, discordance in family care coordination, and undercontributing network members have negative implications for caregiver well-being (Ashida et al., 2018; Sherman et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2021).

A Research Agenda

Our third premise is that understanding how impending demographic and social trends in the United States will influence family caregiving and related outcomes requires more attention to the processes by which caregiving networks form and evolve and the increasing heterogeneity of families of older adults. We therefore call for a renaissance of research on family demography and aging aimed at understanding the implications of the changing nature of family and filial obligations for late-life caregiving, prioritizing attention to six gaps. Within each topic, attention is needed to the experiences of disadvantaged groups of older adults and their potential/actual caregivers—including gender and sexual minorities, minoritized racial/ethnic groups, immigrants, individuals living with disability, and those of low socioeconomic status—and to inequities in care resulting from the broader policy and practice context.

Who is in an older adult’s available and actual care network? Basic definitional issues regarding who is considered part of an older adults’ available and actual care network need attention. Under what circumstances are former spouses, stepchildren from current or past relationships, or stepgrandchildren called upon to provide care? For older persons who have no spouse or adult children, what role is played by romantic ties, friends, siblings, and nieces/nephews in providing care?

How will prior union formation and dissolution patterns and increases in stepfamilies of older adults affect actual care networks? Research should examine how union dissolution and formation over the lives of older adults, including timing of such events, affects care received from adult children and grandchildren. Under what conditions do union dissolution and formation in the grandparent generation affect care received from the adult child and grandchild generations? Such research should focus on both family type (biological families, stepfamilies with and without joint children, families with half-siblings) and dyadic relationships embedded in those families (biological, step, joint child).

What are the implications for caregiving of the changing patterns of intergenerational and multigenerational proximity and strength of ties across families? Research is needed linking care receipt in later life with both geographic proximity (including coresidence) and strength of ties with kin over the life course. Whether intergenerational coresidence initially intended to mainly benefit adult children later translates into caregiving for older adults will be important to understand given the uptick in multigenerational households. Moreover, long-run consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic related to intergenerational coresidence, geographic proximity, and strength of family ties should be explored in relation to late-life caregiving.

Will changes in the nature of work and related policies strain or support working caregivers? The COVID-19 pandemic abruptly changed the nature of work for many working caregivers. Critical questions remain about the persistence of shifts toward hybrid work and flexible hours and their implications for the balance of work and care among older adults’ family members. As care, work and retirement policies continue to evolve, more research is needed on the implications of such changes for work-care trade-offs and inequities in policy impacts.

How will gendered attitudes, preferences, and expectations about caregiving change? As available care networks shift in composition, attitudes and expectations may shift toward more egalitarian responsibilities for caregiving with respect to gender. More work is needed to understand the conditions under which men become active caregivers and the type and quality of care they provide. Understanding who provides care when family members giving or receiving care are nonbinary, transgender, or in same-sex partnerships also needs attention.

How will changes in available and actual family care networks influence well-being of care recipients and caregivers in the future? Greater attention is needed to the link between care network complexity—that is, the inclusion of cohabiting partners, stepfamily, and nonkin relationships—and consequences for both care recipient and caregiver well-being. Prospective studies are needed to help clarify the temporal relations between the nature and quality of support from diverse care network members and care recipient and caregiver well-being over time.

Conclusion

The United States has experienced profound and complex demographic change, and these trends are likely to shape the size and composition of available family care networks of older adults. Understanding how impending demographic and social trends in the United States will influence participation in family caregiving and its outcomes will require more attention to the processes by which caregiving networks form and change and to increasingly diverse and complex kin connections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not reflect those of the funding agency or the authors’ employers. The National Health and Aging Trends Study is funded by the National Institute on Aging through a cooperative agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (grant number U01AG032947).

Contributor Information

Vicki A Freedman, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Emily M Agree, Department of Sociology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Judith A Seltzer, Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Kira S Birditt, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Karen L Fingerman, Department of Human Development and Family Sciences, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA.

Esther M Friedman, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

I-Fen Lin, Department of Sociology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio, USA.

Rachel Margolis, Department of Sociology, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada.

Sung S Park, Office of Population Research, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Sarah E Patterson, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Courtney A Polenick, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Rin Reczek, Department of Sociology, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Adriana M Reyes, Brooks School of Public Policy and Department of Sociology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Yulya Truskinovsky, Department of Economics, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Emily E Wiemers, Department of Public Administration and International Affairs, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA.

Huijing Wu, Department of Sociology, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada.

Douglas A Wolf, Aging Studies Institute, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA.

Jennifer L Wolff, Department of Health Policy and Management, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Steven H Zarit, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA.

Funding

Funding for the Demography of Family Caregiving Network was provided by the Michigan Center on the Demography of Aging through a grant from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (P30AG012846).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Data Availability

Data used in this article are available from https://www.nhats.org.

References

- Ashida, S., Marcum, C. S., & Koehly, L. M. (2018). Unmet expectations in Alzheimer’s family caregiving: Interactional characteristics associated with perceived under-contribution. Gerontologist, 58(2), e46–e55. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. L., Manning, W. D., & Wu, H. (2022). Relationship quality in midlife: A comparison of dating, living apart together, cohabitation, and marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 84(3), 860–878. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui, C. N., Kim, K., & Fingerman, K. L. (2022). Support now to care later: Intergenerational support exchanges and older parents’ care receipt and expectations. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 77(7), 1315–1324. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbac059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D., & Utz, R. L. (2020). Families in later life: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 346–363. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H., Schoeni, R. F., Wiemers, E. E., Hotz, V. J., & Seltzer, J. A. (2020). Spatial distance between parents and adult children in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(2), 822–840. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. A., Sabik, N. J., Cook, S. K., Azzoli, A. B., & Mendez-Luck, C. A. (2019). Differences within differences: Gender inequalities in caregiving intensity vary by race and ethnicity in informal caregivers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 34(3), 245–263. doi: 10.1007/s10823-019-09381-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L., Pillemer, K. A., Silverstein, M., & Suitor, J. J. (2012). The Baby Boomers’ intergenerational relationships. Gerontologist, 52(2), 199–209. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, V. A., & Kasper, J. D. (2019). Cohort profile: The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(4), 1044–1045g. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, V. A., & Wolff, J. (2020). The changing landscape of family caregiving in the United States. In Sawhill I. & Stevenson B. (Eds.), Paid leave for caregiving: Issues and answers. AEI/Brookings. www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Paid-Leave-for-Caregiving.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, E. M., Park, S. S., & Wiemers, E. E. (2017). New estimates of the sandwich generation in the 2013 panel study of income dynamics. Gerontologist, 57(2), 191–196. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J. E. (Ed.). (2021). Bridging the family care gap. Academic Press: Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/C2017-0-00259-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo, K. B. (2014). New partners, more kids: Multiple-partner fertility in the United States. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 66–86. doi: 10.1177/0002716214525571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo, K. B., & Schweizer, V. J. (2020). FP-20-03 Union and childbearing characteristics of women 40–44, 2000–2018. National Center for Family and Marriage Research Family Profiles, 219. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ncfmr_family_profiles/219 [Google Scholar]

- Harvath, T. A., Mongoven, J. M., Bidwell, J. T., Cothran, F. A., Sexson, K. E., Mason, D. J., & Buckwalter, K. (2020). Research priorities in family caregiving: Process and outcomes of a conference on family-centered care across the trajectory of serious illness. Gerontologist, 60(Supplement 1), S5–S13. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, J. M., Parker, K., Graf, N., & Livingston, G. (2017). Americans widely support paid family and medical leave, but differ over specific policies. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/03/23/gender-and-caregiving/ [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, E. (2020). Family caregiving, caregiving leave, and labor market outcomes. In Sawhill I. & Stevenson B. (Eds.), Paid leave for caregiving: Issues and answers. AEI/Brookings. https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Paid-Leave-for-Caregiving.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, J. R., Goldsheider, F., & Garcia-Manglano, J. (2013). Growing parental economic power in parent–adult child households: Coresidence and financial dependency in the United States, 1960–2010. Demography, 50(4), 1449–1475. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0196-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, J. D., Freedman, V. A., Spillman, B. C., & Wolff, J. L. (2015). The disproportionate impact of dementia on family and unpaid caregiving to older adults. Health Affairs, 34(10), 1642–1649. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauer, N. J. (2016). LGBT older adults, chosen family, and caregiving. Journal of Law and Religion, 31(2), 150–168. doi: 10.1017/jlr.2016.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, A. (2017). Health and relationship quality later in life: A comparison of living apart together (LAT), first marriages, remarriages, and cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues, 38(12), 1754–1774. doi: 10.1177/0192513X16647982 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, I.-F., & Brown, S. L. (2012). Unmarried boomers confront old age: A national portrait. Gerontologist, 52(2), 153–165. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, I.-F., Brown, S. L., & Cupka, C. J. (2018). A national portrait of stepfamilies in later life. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(6), 1043–1054. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, I.-F., Brown, S. L., & Mellencamp, K. A. (2022). The roles of gray divorce and subsequent repartnering for parent–adult child relationships. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 77(1), 212–223. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbab139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair, C. A. (2019). Alternatives to aging alone?: “Kinlessness” and the importance of friends across European contexts. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(8), 1416–1428. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, R., & Verdery, A. M. (2017). Older adults without close kin in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(4), 688–693. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, R., & Wright, L. (2017). Older Adults with three generations of kin: Prevalence, correlates, and transfers. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(6), 1067–1072. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, T. J., & Hamilton, B. E. (2002). Mean age of mother, 1970–2000. National Vital Statistics Reports 51(1). National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr51/nvsr51_01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mommaerts, C., & Truskinovsky, Y. (2020). The cyclicality of informal care. Journal of Health Economics, 71, 102306. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2020.102306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Aging Trends Study. Produced and distributed by www.nhats.org with funding from the National Institute on Aging (U01AG32947). [Google Scholar]

- Osterman, M. J. K., Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., Driscoll, A. K., & Valenzuela, C. P. (2022). Births: Final data for 2020. National Vital Statistics Reports 70(17). National Center for Health Statistics. doi: 10.15620/cdc:112078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, S. E., & Reyes, A. M. (2022). Co-residence beliefs 1973–2018: Older adults feel differently than younger adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 84(2), 673–684. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, S. E., Schoeni, R. F., Freedman, V. A., & Seltzer, J. A. (2022). Care received and unmet care needs among older parents in biological and stepfamilies. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 77(Supplement_1), S51–S62. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbab178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas, N. V., Amorim, M., & Dunifon, R. E. (2020). Historical trends in children living in multigenerational households in the United States: 1870–2018. Demography, 57(6), 2269–2296. doi: 10.1007/s13524-020-00920-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymo, J. M., Pike, I., & Liang, J. (2019). A new look at the living arrangements of older Americans using multistate life tables. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(7), e84–e96. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek, C. (2020). Sexual- and gender-minority families: A 2010 to 2020 decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 300–325. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek, R., Lawrence, S., & Thomeer, M. B. (2022). Parent–adult child estrangement in the United States by gender, race/ethnicity, and sexuality. Journal of Marriage and Family. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfoot, D., Feinberg, L., & Houser, A. N. (2013). The aging of the Baby Boom and the growing care gap: A look at future declines in the availability of family caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute. https://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-08-2013/the-aging-of-the-baby-boom-and-the-growing-care-gap-AARP-ppi-ltc.html [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, A., Schoeni, R. F., & Choi, H. (2020). Race/ethnic differences in spatial distance between adult children and their mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(2), 810–821. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, A. M., Schoeni, R. F., & Freedman, V. A. (2021). National estimates of kinship size and composition among adults with activity limitations in the United States. Demographic Research, 45(36), 1097–1114. doi: 10.4054/demres.2021.45.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad-Lessler, J. (2020). How does paid family leave affect unpaid care providers? Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 17(October), 100265. doi: 10.1016/j.jeoa.2020.100265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeni, R. F., Cho, T. C., & Choi, H. (2021). Close enough? Adult child-to-parent caregiving and residential proximity. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114627. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeni, R. F., Freedman, V. A., Cornman, J. C, & Seltzer, J. A. (2022). The strength of parent–adult child ties in biological families and stepfamilies: Evidence from time diaries from older adults. Demography, 59(5), 1821–1842. doi: 10.1215/00703370-10177468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, B. (2021). Providing care changes men: So what keeps so many from having this transformative caregiving experience? Better Life Lab Report. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/better-life-lab/reports/providing-care-changes-men/ [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, R., & Eden, J. (2016). Families caring for an aging America. The National Academies Press. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/1NAC-SCHULZ.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer, J. A. (2019). Family change and changing family demography. Demography, 56(2), 405–426. doi: 10.1007/s13524-019-00766-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer, J. A., & Bianchi, S. M. (2013). Demographic change and parent–child relationships in adulthood. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 275–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer, J. A., Yahirun, J. J., & Bianchi, S. M. (2013). Coresidence and geographic proximity of mothers and adult children in stepfamilies. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5), 1164–1180. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, C. W., Webster, N. J., & Antonucci, T. C. (2013). Dementia caregiving in the context of late-life remarriage: Support networks, relationship quality, and well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5), 1149–1163. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spillman, B. C., Favreault, M., & Allen, E.H. (2020). Family structures and support strategies in the older population: Implications for Baby Boomers. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103486/family-structure-and-support-strategies-in-the-older-population.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Stepler, R. (2017). Number of U.S. adults cohabiting with a partner continues to rise, especially among those 50 and older. Fact Tank: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/06/number-of-u-s-adults-cohabiting-with-a-partner-continues-to-rise-especially-among-those-50-and-older/ [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). U.S. business response to the COVID-19 pandemic summary. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/covid2.nr0.htm

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Table A-1. Annual geographical mobility rates, by type of movement: 2018. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/geographic-mobility/historic.html

- Umberson, D., Donnelly, R., & Pollitt, A. M. (2018). Marriage, social control, and health behavior: A dyadic analysis of same-sex and different-sex couples. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(3), 429–446. doi: 10.1177/0022146518790560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven, C. H., Coe, N. B., & Skira, M. M. (2013). The effect of informal care on work and wages. Journal of Health Economics, 32(1), 240–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdery, A. M., & Margolis, R. (2017). Projections of White and Black older adults without living kin in the United States, 2015 to 2060. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(42), 11109–11114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710341114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. (2018). The state of our unions: Marriage up among older Americans, down among the younger. Institute for Family Studies. https://ifstudies.org/ifs-admin/resources/marriage-trends-brief-final-2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wiemers, E. E., & Bianchi, S. M. (2015). Competing demands from aging parents and adult children in two cohorts of American women. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 127–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00029.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemers, E. E., Seltzer, J. A., Schoeni, R. F., Hotz, V. J., & Bianchi, S. M. (2019). Stepfamily structure and transfers between generations in U.S. families. Demography, 56(1), 229–260. doi: 10.1007/s13524-018-0740-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willink A., Davis K., Mulcahy J., Wolff J. L. (2017). Use of paid and unpaid personal help by Medicare beneficiaries needing long-term services and supports. The Commonwealth Fund. doi: 10.26099/aym5-h778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J. L., Mulcahy, J., Huang, J., Roth, D. L., Covinsky, K., & Kasper, J. D. (2018). Family caregivers of older adults, 1999–2015: Trends in characteristics, circumstances, and role-related appraisal. Gerontologist, 58(6), 1021–1032. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J. L., Spillman, B. C., Freedman, V. A., & Kasper, J. D. (2016). A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(3), 372–379. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J., Liu, P. J., & Beach, S. (2021). Multiple caregivers, many minds: Family discord and caregiver outcomes. Gerontologist, 61(5), 661–669. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this article are available from https://www.nhats.org.