Abstract

Background:

A staggering 85% of the global population resides in low- and middle-income countries (LAMICs). India stands as an exemplary pioneer in the realm of mental health initiatives among LAMICs, having launched its National Mental Health Program in 1982. It is imperative to effectively evaluate mental health systems periodically to cultivate a dynamic learning model sustained through continuous feedback from mental healthcare structures and processes.

Materials and Methods:

The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) embarked on the Mental Health Systems Assessment (MHSA) in 12 representative Indian states, following a pilot program that contextually adapted the World Health Organization's Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems. The methodology involved data collection from various sources and interviews with key stakeholders, yielding a set of 15 quantitative, 5 morbidity, and 10 qualitative indicators, which were employed to encapsulate the functional status of mental health systems within the surveyed states by using a scorecard framework.

Results:

The NMHS MHSA for the year 2015–16 unveiled an array of indices, and the resultant scorecard succinctly encapsulated the outcomes of the systems' evaluation across the 12 surveyed states in India. Significantly, the findings revealed considerable interstate disparities, with some states such as Gujarat and Kerala emerging as frontrunners in the evaluation among the surveyed states. Nevertheless, notable gaps were identified in several domains within the assessed mental health systems.

Conclusion:

MHSA, as conducted within the framework of NMHS, emerges as a dependable, valid, and holistic mechanism for documenting mental health systems in India. However, this process necessitates periodic iterations to serve as critical indicators guiding the national mental health agenda, including policies, programs, and their impact evaluation.

Keywords: Epidemiology, evaluation, India, mental health systems, monitoring, performance, psychiatry, services, systems

INTRODUCTION

Psychiatric disorders are one of the leading causes of disability worldwide[1] and are associated with significant morbidity.[2,3] India has a population of nearly 1.4 billion. Among these 1.4 billion, every tenth person suffers from mental health issues. However, there is a large treatment gap for mental disorders in India, ranging from 70% to 90%.[2] In addition, over the past three decades, the disease burden due to mental disorders and its contribution to the total disease burden has nearly doubled.[4]

The World Mental Health Atlas 2020, initiated by the WHO, highlights disparities in global mental health systems.[5] Approximately 31% of WHO member countries collect mental healthcare data, emphasizing the need for greater investment in policies and services. In 2020, 88% of Member States completed the questionnaire, with increased data compilation and policy adoption. However, limited resources and disparities in mental health infrastructure persist. Only 31% integrate mental health into primary care, and service coverage varies widely. Suicide prevention and stigma reduction programs have improved, but disparities remain. A uniform mental health system assessment initiative is needed to address challenges and enhance mental healthcare globally. India's National Mental Health Survey-Mental Health Systems Assessment (NMHS-MHSA) assessed mental health systems in 12 surveyed states providing valuable insights and the potential for expansion.

Mental health systems are a multidimensional construct and include components of planning and organization such as mental health policies, programs, plans, legislations, regulations, and finances; the delivery of primary, secondary, and tertiary mental healthcare; training of mental healthcare professionals; monitoring and evaluation strategies based on mental health information systems; and health education and community participation. The development of a robust mental health system requires political and sociocultural leadership at macroscopic, mesoscopic, and microscopic levels to achieve coordinated goals.[6]

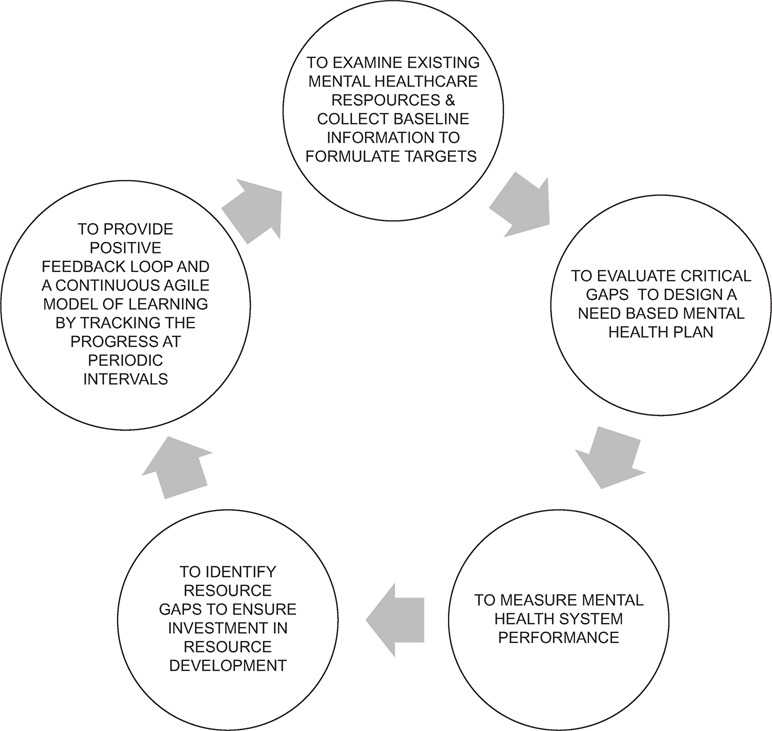

Mental health systems assessment is the first essential step for planning, strengthening implementation, and revision of mental healthcare delivery in India [Figure 1]. The previous mental health systems assessments in India have been largely confined to the national and district mental health program audits and assessments conducted by various organizations.[7] Although each of these reports provided critical information about mental health systems, the lack of uniformity in assessments and the presence of different goals behind each of these assessment initiatives make it difficult to synthesize the information into common themes that can serve multiple purposes of mental health systems assessment.

Figure 1.

The processes of a mental health system assessment in India

MATERIALS AND METHODS

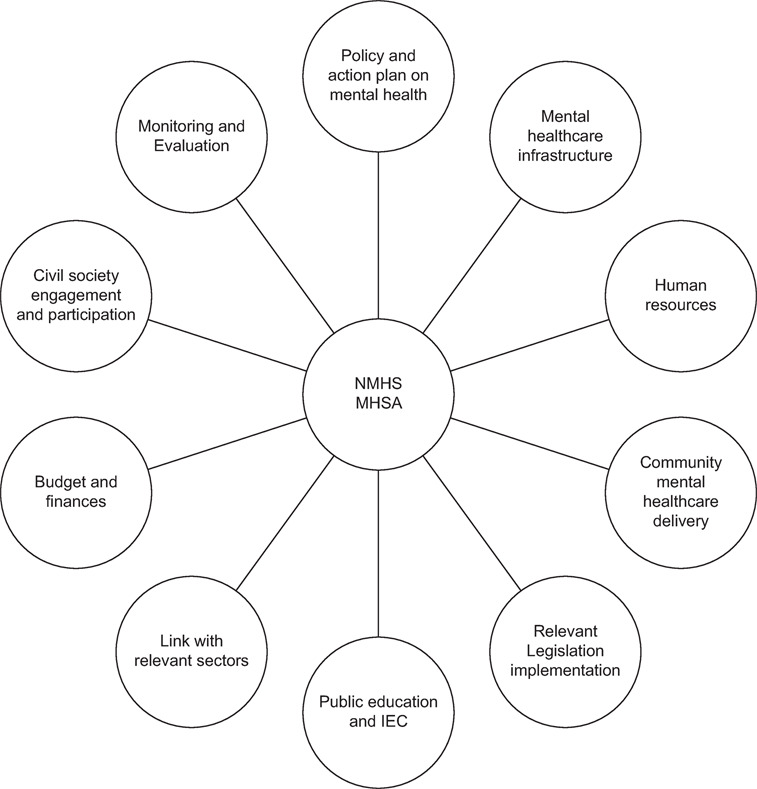

The detailed framework of NMHS-MHSA is discussed comprehensively elsewhere.[8] NMHS-MHSA adopted the World Health Organization-Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS) version.[9] The mental health systems assessment was piloted in the Kolar district of Karnataka and further scaled to 16 districts of Tamil Nadu implementing the district mental health program. This process helped to develop and refine the execution of NMHS-MHSA that was later expanded to 12 surveyed states. It specifically focuses on the triad of assessing the mental health system in each state (primary focus), along with exploring the mental health systems in districts implementing/not implementing DMHP. The NMHS-MHSA collected data pertain to the ten components of mental health systems as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Domains considered under NMHS-MHSA. NMHS = National Mental Health Survey, MHSA = Mental Health Systems Assessment, IEC = Information, education, and communication

Multiple data sources, which are summarized in Table 1, were accessed to collect the required data, and data validation was undertaken through triangulation and data iteration processes. The final set of data and the derived indicator values were finalized by involving various stakeholders as part of the state-level consensus meeting. The NMHS-MHSA involved the following sequential process: proforma development, secondary data collection by the state team, review of the data by the NIMHANS team, development of indicators and state scorecard by the NIMHANS team, state-level expert consensus meeting to discuss the indicator and state score card by the respective state teams, followed by the final step of individual state score sheet finalization.

Table 1.

Data sources in the National Mental Health Survey–Mental Health Systems Assessment

| Information on | Source and data collected |

|---|---|

| Demography, administration, and economics | Indian census 2011 for population-related data and the data on economics from the Directorates of Economics and Statistics |

| General healthcare facilities | Multiple sources |

| Human resources in general healthcare facilities | Multiple sectors focusing on the public sector only |

| DMHP coverage | State mental health nodal officers, Health and family welfare departments from states with data focused on DMHP coverage prior to and after the 12th five-year plan |

| Mental healthcare facilities [dedicated mental healthcare facilities + general healthcare facilities providing mental healthcare as well] | Multiple sources – State health and family welfare departments, key persons from mental healthcare facilities, medical colleges, State mental health nodal officers, and State mental health authority |

| Human resources for mental health | From registries, professional regulatory bodies, and data sources on the number of mental health professionals trained and headcount resources available |

| Mental health financing | Administrative and financial records of state health and family welfare departments, state audits, policy and plan documents, and the State Nodal Officer for Mental Health |

| Burden of mental disorder and treatment gap | National Mental Health Survey 2016 |

| Suicide | 2014 report from the National Crime Records Bureau under the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India |

| Qualitative data [especially when quantitative data was difficult to obtain] | State Nodal Officer for Mental Health |

For the data across all these categories - The NMHS team rigorously validated and cross-referenced data from diverse sources, utilizing an iterative approach and state-level consensus meetings, The detailed list of sources is available from the report from NMHS on MHSA (http://indianmhs.nimhans.ac.in/index.php)

An iterative approach was adopted by the NMHS team to validate and cross-reference data from diverse sources and levels. For some variables, the NMHS team relied on data from a single source, while others were constructed by amalgamating information from multiple sources, including credible reports, official documents, websites, and personal communications across various tiers for the most recent year, all clearly documented in the datasheet. The validation process culminated during the state-level consensus meeting. In addition, the NMHS team cross-verified the data with the recent NHRC report and the National Health Profile-2015, selectively incorporating specific parameters. This rigorous methodology ensured the validity, authenticity, and robustness of the data sources. Nevertheless, it is important to note that gathering data for the private sector posed inherent challenges related to the unavailability of consolidated sources of information and poor utility of the available information sources. The overall sources of information are summarized in Table 1.

Key indicators

As part of the mental health systems state scorecard, a set of quantitative and qualitative indicators were developed, including the burden of mental disorders and their treatment gap [Table 2]. This table with its information reproduced completely from the NMHS-MHSA report[8] summarizes the indicators.

Table 2.

Key MHSA indicators reproduced from the National Mental Health Survey–Mental Health Systems report

| Category | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Quantitative indicators | General health facilities (public and private sector) in the state (number per 100,000 population) |

| Health professionals/personnel available in the state (number per 100,000 population) | |

| Districts in the state covered by DMHP (%) | |

| State population covered by DMHP (%) | |

| Tribal population covered by DMHP (%) | |

| Mental health facilities in the state (number per 100,000 population) | |

| District/General hospitals in the state providing mental health services (%) | |

| Taluka hospitals in the state providing mental health services (%) | |

| PHCs in the state providing mental health services (%) | |

| Beds available for mental health inpatient services in the state (number per 100,000 population) | |

| Mental health professionals/personnel in the state (number per 100,000 population) | |

| Health professionals/personnel in the state who have undergone training in mental health in the last 3 years | |

| Percent of total health budget allotted for mental health by state health department | |

| Percentage of total allotted mental health budget that is utilized | |

| Suicide incidence per 100,000 population, by age and gender | |

| Burden and treatment gap of mental morbidity | Prevalence and treatment gap of Common mental disorder |

| Prevalence and treatment gap of Severe mental disorder | |

| Prevalence and treatment gap of Depressive disorder | |

| Prevalence and treatment gap of Alcohol use disorder | |

| Prevalence and treatment gap of High Suicidal risk | |

| Qualitative indicators | Mental Health Policy |

| Mental health action plan and status of its implementation | |

| State mental health Co-ordination mechanism | |

| Mental health budget | |

| Training programme on mental health | |

| Availability of Drugs | |

| Availability of IEC materials and implementation of IEC activities | |

| Intra and Inter-sectoral collaboration for Mental health | |

| Monitoring of mental health activities | |

| Implementation status of legislation pertaining to mental health |

The table contents are taken directly from the National Mental Health Survey report and they are available in the supplementary table of the cited article i.e.., Table S2 of Additional File 1 of reference 8

RESULTS

NMHS-MHSA conducted in 12 states covered all the regions of India and included states in various levels of socioeconomic development. The presence of a Health Management Information System (HMIS) varies across different states in India. All states studied, except for Assam, implemented HMIS. However, not all of them have integrated mental health into the HMIS. Mental health is included in the HMIS in Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Punjab. In terms of computerization, the majority of these states have computerized their HMIS with the exception of Assam and Manipur. Some states reached a high level of computerization, such as Jharkhand, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, which have achieved 75%–100% computerization. However, some states, such as Manipur, have not disclosed the extent of computerization. These variations highlight the diverse levels of HMIS implementation and computerization across different Indian states.

In the public sector, the availability of healthcare facilities varies across Indian states. Rajasthan stands out with a high number of public healthcare facilities, with 31.22 healthcare facilities per 100,000 population. In contrast, Uttar Pradesh (14.82) and Jharkhand (14.80) have relatively fewer facilities. In the private sector, the availability of healthcare facilities also varies, with Punjab having the highest number (18.08) and Rajasthan having the lowest (0.02) per 100,000 population. When considering both public and private sectors, Chhattisgarh had the highest, with a total of 46.45 healthcare facilities per 100,000 population, while Uttar Pradesh lagged behind with 14.85 facilities. These statistics reveal significant disparities in healthcare infrastructure across different surveyed states in India.

With respect to human resources, health force work density ranged from approximately 193 persons per 1,00,000 in Uttar Pradesh to around 995 in Kerala. Field-level and lay health workers comprising ASHA/USHA/ANM/and other cadres of health workers contributed majorly to this workforce. The density of doctors was the highest in West Bengal (~64 per 1,00,000). Central India, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh had a low doctor ratio of 5–6 per 1,00,000 population. The DMHP coverage was 100% in Tamil Nadu and was poor in Punjab (13.64%). The majority (2/3rd) of the states had less than 50% coverage of population at the time of NMHS 2016.

There were 0.3 psychiatrists per 100,000 persons (77% deficit) in India. Psychologists and psychiatric social workers were even fewer. Kerala had 211 psychologists (0.63/100,000 population), while Rajasthan had only 9 (0.01/100,000 population). West Bengal had 110 psychiatric social workers (0.12/100,000 population), while Rajasthan had 6 (0.01 per 100,000 population). Psychiatrists availability in the surveyed states varied from 0.05 per 100,000 population in Madhya Pradesh to 1.2 per 100,000 in Kerala. Tamil Nadu had the highest number of mental health trained nurses at 7555 (10.5/100,000 population). Both Kerala and Tamil Nadu had the highest number (n = 37) of institutions providing an MSc degree in Psychiatry Nursing. The availability of qualified psychiatric social workers was uniformly poor across all states. Tamil Nadu had the maximum number of postgraduate psychiatry course-providing institutions followed by Kerala and Uttar Pradesh (n = 12), while no institutions were available for Psychiatry M.D. training in Chhattisgarh. However, many of these parameters have improved since then.

Nearly 6829 patients were using in-patient services in various mental hospitals across the surveyed states as on December 31, 2015, of which one-third (2245) were in Madhya Pradesh alone. Among them, 16% of in-patients across mental hospitals. The state of Manipur reported zero psychiatry inpatients. Nearly 16% of the total in-patients in mental health institutions were inpatients for more than 5 years.

Gujarat and Kerala scored higher on the composite score. A crucial determinant of this was that there were only two states at the time of NMHS 2016 that had an existing state mental health policy. Most states had a composite score of between 25 and 50, indicating that the existing systems in most states were less than half of the optimal state. Most states had scored around 7 in the state mental health coordination mechanism, which was encouraging. Most states fared poorly on the training program on mental health. Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand were two states that fared poorly on most parameters. Among the surveyed states, the states of Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Kerala, and Assam had an action plan for mental health in various stages of planning and delivery.

Among mental health legislations, the Mental Health Act, the Juvenile Justice Act, and the Domestic Violence Act are legislations that were implemented in varying degrees in most states. IEC activities were carried out in the majority of the districts in the states of Kerala and Gujarat, while the coverage was less than 50% of the districts in the surveyed states of Tamil Nadu, Assam, Manipur, and Punjab.

States such as Chhattisgarh, Assam, Gujarat, Jharkhand, and Rajasthan reported the availability of mental health drugs “always” for more than 75% of the essential psychotropics. Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu had 68% of the listed drugs available.

Although the majority (72%) of surveyed states reported that intersectoral and intrasectoral coordination existed, NMHS-MHSA reported that in most instances, these were need-based and limited to focal activities. Disability assessment and certification are important metrics across states. Among the surveyed states, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal had no information on the provision of disability certificates. The vast range of disability certification numbers across states ranged from 14 in Manipur to 7.48 lakhs in Gujarat.

The key results from the NMHS-MHSA report card for surveyed states are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mental health scorecard for 10 qualitative mental health system indicators across NMHS states (in alphabetical order)

| State | Mental Health Policy | Mental health action plan and status of its implementation | State mental health coordination mechanism | Mental health budget | Training program on mental health | Availability of Drugs | Availability of IEC materials and implementation of IEC activities | Intra and Inter-sectoral collaboration for Mental health | Implementation status of legislation about mental health | Monitoring of mental health activities | Total score out of 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assam | 0 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 34 |

| Chhattisgarh | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 18 |

| Gujarat | 10 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 69 |

| Jharkhand | 0 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 26 |

| Kerala | 10 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 65 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 31 |

| Manipur | 0 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 35 |

| Punjab | 0 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 36 |

| Rajasthan | 0 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 29 |

| Tamil Nadu | 5 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 48 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 5 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 39 |

| West Bengal | 5 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 45 |

1. All scores ranged from a range of 0–10. 2. As per the disclaimer given in the NMHS report, the fact sheet data have been collated from multiple secondary sources and discussed during the state-level consensus meeting; based on this, the best possible information has been provided. More details of data collection methods are provided in the report and available on request. 3. Mean scores rounded to the first decimal. 4. These scores are meant as a standalone and not for comparison with each other due to the varying levels of development trajectories of the individual states. However, states can draw inspiration from other states in finding feasible, innovative solutions

DISCUSSION

The NMHS-MHSA marks a significant departure from traditional methods of assessing mental health indicators. Instead of adhering to predefined criteria from national and district mental health programs, it represents a collaborative and comprehensive effort to scrutinize India's mental health systems. This initiative goes beyond merely evaluating care standards and delves into the intricacies of India's mental healthcare infrastructure. The findings from this comprehensive assessment reveal notable disparities among Indian states, highlighting the nation's diverse healthcare landscape. In addition, it points toward glaring gaps that need to be urgently filled up in the background of recent developments (MHCA, Mental Health Policy, integration of mental health in comprehensive primary care package of Ayushman Bharat, etc.) These regional variations have the potential to significantly impact national-level estimates, underscoring the need for a more nuanced, localized approach to addressing mental health in India.

Individual state mental health policies and action plans are crucial, as are the coordination between various ministries/departments at the center and state levels. In this context, a notable development is mental healthcare financing, which is now part of the flexible pool of finances allotted to non-communicable diseases.[10] Similar models should percolate across many layers till the grassroots.

Mental health financing is a critical pillar of any healthcare system, ensuring the availability and accessibility of mental health services. As the Emerald project has shown, poor funding, inequalities, and poverty are the three most important factors influencing mental healthcare systems and delivery.[11] In the Indian context, both at the national and state levels, mental health financing has often lagged behind the requirements, leading to significant service gaps. Adequate and timely spending of allocated funds is yet another concern that is plaguing the sector.

Mental health care facilities, mental health human resources, and mental health training institutes are integral to a robust mental health system. To address these issues, states in India and the country as a whole must invest in expanding mental health care infrastructure, increasing the number of mental health professionals through education and training, and fostering collaboration with both public and private sectors. However, the nation has seen significant development and expansion in this field. For example, the number of psychiatrists graduating every year has crossed 1200 now, and the number of other mental health professionals is considerably increasing too.

Human resource development, facilitated by digital technology and supported by initiatives from Centers of Excellence in India, is necessary to address the shortage of mental health professionals.[12,13,14,15] In addition, upgrading healthcare facilities to offer accessible stepped care models can counter the dominance of non-governmental healthcare delivery. The establishment of a national registry of service providers, complete with geo-mapping capabilities, is pivotal to ensure the effective utilization of both public and private mental healthcare networks, thereby addressing the treatment gap in India. Furthermore, a focus on rehabilitation through the creation of dedicated healthcare facilities; services to promote the inclusion of individuals with mental disorders in society; provision of disability benefits; re-skilling opportunities; protected employment; and the implementation of supportive legal, legislative, and economic protection measures are all indispensable components of an enhanced mental healthcare system in India. Again, India has seen a phenomenal growth in the mental health sector. DMHP is now operational in more than 700 districts of the country. The Mental Healthcare Act (2017) includes mental health as one of the 12 packages of the Comprehensive Primary Health Care scheme of Ayushman Bharat initiative, leveraging digital technology for large-scale mental health capacity building. Tele-MANAS, India's National Tele Mental Health Program, is an innovative decentralized system using mobile phones to extend mental health services. It also integrates with e-sanjeevani, showcasing a holistic approach to healthcare delivery and highlighting India's commitment to expanding mental health support through digital platforms. Several states have shown innovations in mental healthcare delivery at district level such as the Dava and Dua initiative and the Manochaitanya program. Additionally in two states (Karnataka and Gujarat) the Taluk Mental Health Pilot Programs are operational as well.[16,17,18,19,20,21,22] Across the country, centers of excellence play a crucial role in significantly contributing to the development of mental healthcare resources. Their impactful contributions underscore the nationwide commitment to advancing and enhancing mental health services. For example, the NIMHANS Digital Academy (NDA) has played a pivotal role in addressing the critical challenge of bridging the treatment gap by empowering healthcare professionals to deliver essential mental health services. NDA is making a significant impact by training over 25,000 healthcare professionals in mental health-related courses. This diverse group includes doctors, psychologists, social workers, and nurses, enhancing the accessibility of mental health services. Of those trained, 2024 doctors, 786 psychologists, 639 social workers, and 664 nurses are enrolled in diploma programs, and NDA has also reached project-accredited professionals, such as doctors, rural health organizers, and community health officers, further expanding the reach of mental health care.

This multifaceted approach underscores NDA's dedication to addressing mental health challenges by nurturing a diverse and skilled workforce committed to providing care to those who need it most.[23] These models when replicated across the country will have a huge impact on mental healthcare services.

Drug availability at healthcare facilities is a crucial limiting factor in mental healthcare service delivery. The NMHS-MHSA pointed out the lack of uniform availability of all essential psychotropics across primary health centers and subcenters. A standardized approach to dedicated psychotropic stock registers and seamless drug logistics, including procurement through tenders and indenting, maintenance, and inventory control, is vital. In India, the availability of essential mental health drugs has been a longstanding concern. To address this issue, states and the country as a whole should prioritize mental health as a part of the broader healthcare system, ensuring that essential drugs are readily available in both public and private healthcare facilities. One successful example comes from Brazil, where the government's Mental Health Program has implemented policies to guarantee the free distribution of essential psychotropic medications in the public health system. Such initiatives have significantly improved drug availability, reduced treatment costs, and increased access to mental health care.[24] India has already made it mandatory under the Mental Healthcare Act to provide free treatment to all persons with mental illness who cannot afford the treatment.[25]

Monitoring, evaluation, and research are essential components of any effective mental health system. They help assess the impact of existing programs, identify areas of improvement, and make data-driven decisions. The states and the country should invest in comprehensive data collection, analysis, and research efforts to understand the evolving mental health landscape. This includes evaluating the effectiveness of various interventions, tracking mental health indicators, and conducting studies to inform policy decisions.

Sustainable mental health system financing and decreasing financial burden of mental healthcare provision models from developing countries suggest that health insurance extension regardless of economic status and employment status is essential.[26]

The key learnings from the Mental Health Systems Assessment of the NMHS are as follows,

Mental health systems in the surveyed states are fragmented with isolated approaches toward mental health programs. Lack of coordination, inadequate financing of mental health programs, shortage of mental health professionals, and poor implementation of mental health-related legislations were observed across the states. With exceptions, standalone mental health policy was absent in the surveyed states.

Mental health in India, in 2016, was still largely confined to diagnosis and drug delivery for program implementation. The larger areas of mental health promotion, continued community care, rehabilitation, welfare and protection issues, integration of mental health into other health and health-related programs and non-health sectors, systematic monitoring, and periodic evaluation were at best only minimal.

There is a need for strengthening and reorienting the health sector to address existing and emerging mental health issues. Improving governance, leadership, resource enhancement, capacity building of institutions and professionals, and scaling up of advocacy efforts are needed for advancing mental health programs in the surveyed states and the country in general.

NMHS-MHSA offers a rapid and comprehensive way to assess mental health systems at the state level in India. Regular mental health systems assessments should be conducted for all states in India to guide National Mental Health Policy and align with global health goals. This will also aid in states learning from each other.

Continuous improvements in NMHS-MHSA depend on better data sources and a strengthened mental health information system, leveraging India's digital health initiative. Regular mental health systems assessments are vital for shaping India's National Mental Health Policy and tracking progress toward WHO's Mental Health Action Plan and Sustainable Development Goal-3 targets.

This assessment method is cost-effective and robust, making it a suitable template for use in low- and middle-income countries (LAMICs) with contextual modifications.

Limitations of NMHS MHSA and recommendations for the next phase of assessments

The NMHS-MHSA has the following limitations that can be considered for further evolution of mental health systems. Availability of data was one of the major limitations. If better data is available, then the NMHS-MHSA indicators will provide better and a more realistic picture fostering an accurate and agile learning model. However, despite this limitation, the consensus method to a certain extent helped to validate the collected data and information, and hence the findings have ecological validity.[27,28,29] The primary exclusive focus of the NMHS-MHSA is around the treatment gap and access to qualified health providers. However, MHSA needs to incorporate how individuals were adequately treated and made a functional recovery. This is a more accurate indicator of effectiveness than the treatment gap alone.[30,31] A limitation of the mental health scorecard assessment method is the absence of validation for the scorecard. This raises the concern that certain items within the scorecard might be assigned equal weightage, despite their potentially varying implications on mental health systems and service delivery. Nevertheless, it is important to note that this was the inaugural attempt at such an endeavour. In future mental health systems assessments, recalibration and validation can be a valuable step to address this limitation.

Actionable information from NMHS-MHSA at the state level is a welcome step. However, policymaking needs to evolve beyond the current form to include components of process, outcome, and impact indicators in each catchment area that can be defined as a geographical area covered by the primary health center for process and outcome indicators and impact indicators at the district level. Further growth of NMHS-MHSA through collaborations with LAMIC initiatives such as the emerald initiative can lead to further gain from other countries with similar ethos.[32]

Although NMHS-MHSA speaks about insurance, adding indicators on insurance coverage for mental health and the claims settled can be a necessary step. This is also in line with the MHCA 2017.[25]

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the NMHS-MHSA marks a pivotal step toward assessing India's mental health systems comprehensively. By uncovering state-level variations, it highlights the need for tailored approaches. To succeed, India must focus on policies, funding, infrastructure, and human resources. This initiative provides a roadmap for a more accessible and responsive mental health ecosystem. MHSA assessments should be periodically carried out in light of several relatively newer initiatives that have seen the light of day.

Financial support and sponsorship

The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) was funded by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, and was implemented and coordinated by the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru, INDIA in collaboration with state partners. NMHS phase 1 (2015-16) was undertaken in 12 states of India across six regions and interviewed 39,532 individuals (http://indianmhs.nimhans.ac.in). Funder had no role in the implementation, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and write-up of the paper.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

NMHS National collaborators group include Pathak K, Singh LK, Mehta RY, Ram D, Shibukumar TM, Kokane A, Lenin Singh RK, Chavan BS, Sharma P, Ramasubramanian C, Dalal PK, Saha PK, Deuri SP, Giri AK, Kavishvar AB, Sinha VK, Thavody J, Chatterji R, Akoijam BS, Das S, Kashyap A, Ragavan VS, Singh SK, Misra R, and investigators as listed in the report “National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015–16: Prevalence, Patterns, and Outcomes” available at https://indianmhs.nimhans.ac.in/phase1/Docs/Report2.pdf.

The authors would also like to sincerely thank Professor David V Sheehan, Distinguished University Health Professor Emeritus at College of Medicine, University of South Florida, USA, for his guidance and valuable inputs for the smooth, scientific, and efficient conduct of the survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.GBD 2017 Disease and injury incidence and prevalence collaborators global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gautham MS, Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Kokane A, et al. The national mental health survey of India (2016): Prevalence, socio-demographic correlates and treatment gap of mental morbidity. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:361–72. doi: 10.1177/0020764020907941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao G, Pathak K, Singh L, et al. National mental health survey of India, 2015-16. prevalence, pattern and outcome. NIMHANS. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sagar R, Dandona R, Gururaj G, Dhaliwal RS, Singh A, Ferrari A, et al. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:148–61. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Mental Health Atlas. 2020. [Last accessed on 2022 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036703 .

- 6.Minas H, Cohen A. Why focus on mental health systems? Int J Ment Health Syst. 2007;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao G, Pathak K, Singh L, et al. 130 Bengaluru, India: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences NIMHANS Publ; 2016. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Mental Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arvind BA, Gururaj G, Rao GN, Pradeep BS, Mathew V, Benegal V, et al. Framework and approach for measuring performance and progress of mental health systems and services in India: National Mental Health Survey 2015–2016. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14:20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO World Health Organization assessment instrument for mental health systems-WHO-AIMS version 2.2. 2005. [Last accessed on 2021 Nov 18]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70771 .

- 10.Aarti D. At India's insistence, mental health included as non-communicable disease. The Hindu. 2011. [Last accessed on 2023 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/health/policy-and-issues/at-indias-insistence-mental-health-included-as-noncommunicable-disease/article1991279.ece .

- 11.Chisholm D, Docrat S, Abdulmalik J, Alem A, Gureje O, Gurung D, et al. Mental health financing challenges, opportunities and strategies in low- and middle-income countries: Findings from the Emerald project. BJPsych Open. 2019;5:e68. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bada Math S, Moirangthem S, Kumar CN. Public health perspectives in cross-system practice: Past, present and future. Indian J Med Ethics. 2015;12:131–6. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2015.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Math SB, Moirangthem S, Kumar NC. Tele-Psychiatry: After Mars, Can we Reach the Unreached? Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37:120–1. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.155606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim FA, Pahuja E, Dinakaran D, Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Math SB. The future of telepsychiatry in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42(5 Suppl):112S–7S. doi: 10.1177/0253717620959255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moirangthem S, Rao S, Kumar CN, Narayana M, Raviprakash N, Math SB. Telepsychiatry as an economically better model for reaching the unreached: A retrospective report from south India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39:271–5. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_441_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Chander KR, Sadh K, Gowda GS, Vinay B, et al. Taluk mental health program: the new kid on the block? Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:635–9. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_343_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gangadhar BN, Kumar CN, Sadh K, Manjunatha N, Math SB, Kalaivanan RC, et al. Mental health programme in India: has the tide really turned? Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2023;157:387–94. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2217_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pahuja E, Kumar TS, Uzzafar F, Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Gupta R, et al. An impact of a digitally driven primary care psychiatry program on the integration of psychiatric care in the general practice of primary care doctors. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:690–6. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_324_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Math SB, Thirthalli J. Designing and implementing an innovative digitally driven primary care psychiatry program in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:236–44. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_214_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Math SB, Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Dinakaran D, Gowda GS, Rao GN, et al. Mental healthcare management system (e-manas) to implement India's mental healthcare act, 2017: Methodological design, components, and its implications. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;57:102391. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nirisha PL, Malathesh BC, Kulal N, Harshithaa NR, Ibrahim FA, Suhas S, et al. Impact of technology driven mental health task-shifting for accredited social health activists (Ashas): Results from a randomised controlled trial of two methods of training. Community Ment Health J. 2023;59:175–84. doi: 10.1007/s10597-022-00996-w. doi: 10.1007/s10597-022-00996-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suhas S, Kumar CN, Math SB, Manjunatha N. E-Sanjeevani: A pathbreaking telemedicine initiative from India. Journal of Psychiatry Spectrum. 2022;1:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.India N. NIMHANS Digital Academy. NIMHANS DIGITAL ACADEMY (NDA) 2023. [Last accessed on 2023 Oct 18]. Available from: https://nda.nimhans.ac.in/

- 24.Rodrigues PS, Francisco PMSB, Fontanella AT, Costa KS. Free acquisition of psychotropic drugs by the Brazilian adult population and presence on the National List of Essential Medicines. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2022;58:e20290. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Law and Justice G of I Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. An Act to provide for mental healthcare and services for persons with mental illness and to protect, promote and fulfil the rights of such persons during delivery of mental healthcare and services and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. 2017. [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 16]. Available from: http://indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2249 .

- 26.Abdulmalik J, Olayiwola S, Docrat S, Lund C, Chisholm D, Gureje O. Sustainable financing mechanisms for strengthening mental health systems in Nigeria. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13:38. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0293-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith TE, Sullivan AT, Druss BG. Redesigning public mental health systems post-COVID-19. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:602–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maulik PK, Thornicroft G, Saxena S. Roadmap to strengthen global mental health systems to tackle the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14:57. doi: 10.1186/s13033-020-00393-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belkin G, Appleton S, Langlois K. Reimagining mental health systems post COVID-19. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5:e181–2. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slade M, Amering M, Farkas M, Hamilton B, O'Hagan M, Panther G, et al. Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:12–20. doi: 10.1002/wps.20084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hannigan B, Simpson A, Coffey M, Barlow S, Jones A. care coordination as imagined, care coordination as done: Findings from a cross-national mental health systems study. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18:12. doi: 10.5334/ijic.3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semrau M, Alem A, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chisholm D, Gureje O, Hanlon C, et al. Strengthening mental health systems in low- and middle-income countries: Recommendations from the Emerald programme. BJPsych Open. 2019;5:e73. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2018.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]