Abstract

Messenger RNA (mRNA) can treat genetic disease using protein replacement or genome editing approaches but requires a suitable carrier to circumnavigate biological barriers and access the desired cell type within the target organ. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are widely used in the clinic for mRNA delivery yet are limited in their applications due to significant hepatic accumulation because of the formation of a protein corona enriched in apolipoprotein E (ApoE). Our lab developed selective organ targeting (SORT) LNPs that incorporate a supplementary component, termed a SORT molecule, for tissue-specific mRNA delivery to the liver, spleen, and lungs of mice. Mechanistic work revealed that the biophysical class of SORT molecule added to the LNP forms a distinct protein corona that helps determine where in the body mRNA is delivered. To better understand which plasma proteins could drive tissue-specific mRNA delivery, we characterized a panel of quaternary ammonium lipids as SORT molecules to assess how chemical structure affects the organ-targeting outcomes and protein corona of lung-targeting SORT LNPs. We discovered that variations in the chemical structure of both the lipid alkyl tail and headgroup impact the potency and specificity of mRNA delivery to the lungs. Furthermore, changes to the chemical structure alter the quantities and identities of protein corona constituents in a manner that correlates with organ-targeting outcomes, with certain proteins appearing to promote lung targeting whereas others reduce delivery to off-target organs. These findings unveil a nuanced relationship between LNP chemistry and endogenous targeting, where the ensemble of proteins associated with an LNP can play various roles in determining the tissue-specificity of mRNA delivery, providing further design criteria for optimization of clinically-relevant nanoparticles for extrahepatic delivery of genetic payloads.

Keywords: Lipid nanoparticle, Protein corona, mRNA delivery, Lungs, Endogenous targeting

1. Introduction

Lipid nanoparticle (LNP) formulations are a clinically-validated strategy for the delivery of messenger RNA (mRNA) in humans, most notably as vaccines to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, in a safe and efficient manner [1–3]. On its own, mRNA does not readily traverse the cellular membrane, due to its large molecular weight and negatively-charged phosphate backbone, and nucleases in the extracellular environment can lead to its premature degradation [3]. By encapsulating mRNA within LNPs, these biological barriers can be circumnavigated to facilitate protein expression in target cells. Beyond vaccination, mRNA has great potential to treat genetic disease through protein replacement therapy [4] and in vivo genome editing approaches [5–8]. However, the clinical landscape of mRNA remains limited to diseases with liver involvement [9–12] or applications based on localized administration due to significant hepatic accumulation of LNPs following systemic injection [13,14].

Analogous to endogenous lipoproteins [15], intravenously administered LNPs bind plasma proteins, such as apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and rapidly biodistribute to the liver via the hepatic artery [14,16,17]. Within the liver, LNPs extravasate through fenestrae in the endothelium to access the Space of Disse where surface-bound ApoE can interact with the low-density lipoprotein receptor, which is highly-expressed by hepatocytes, to facilitate intracellular mRNA delivery [14]. Therefore, to expand the scope of applications for mRNA-based protein replacement therapy and genome editing, it is necessary to devise strategies that are capable of side-stepping this mechanism of liver delivery and accessing additional tissue types [18].

Intravenous injection is a preferred route of administration that could enable mRNA delivery to multiple organs via the circulatory system should a strategy be devised to overcome the key barrier of hepatic accumulation. Recently, our lab developed selective organ targeting (SORT) LNPs which utilize an endogenous targeting mechanism for tissue-specific mRNA delivery to extrahepatic organs following systemic administration [19–23]. While conventional LNP formulations are comprised of four lipid components, SORT LNPs integrate a fifth supplementary component, termed a SORT molecule, whose chemical structure governs where in the body mRNA is delivered (Fig. 1a) [19]. Mechanistic work revealed that the biophysical class of SORT molecule added to an LNP determines the composition of the protein corona, that is the interfacial layer of plasma proteins that associates with a nanoparticle upon contact with the blood [24]. For extrahepatic delivery, the LNP protein corona is enriched in factors distinct from those implicated in hepatic accumulation, including ApoE, thereby de-targeting the liver and promoting interactions with other receptors highly expressed by cells in the target organs [22].

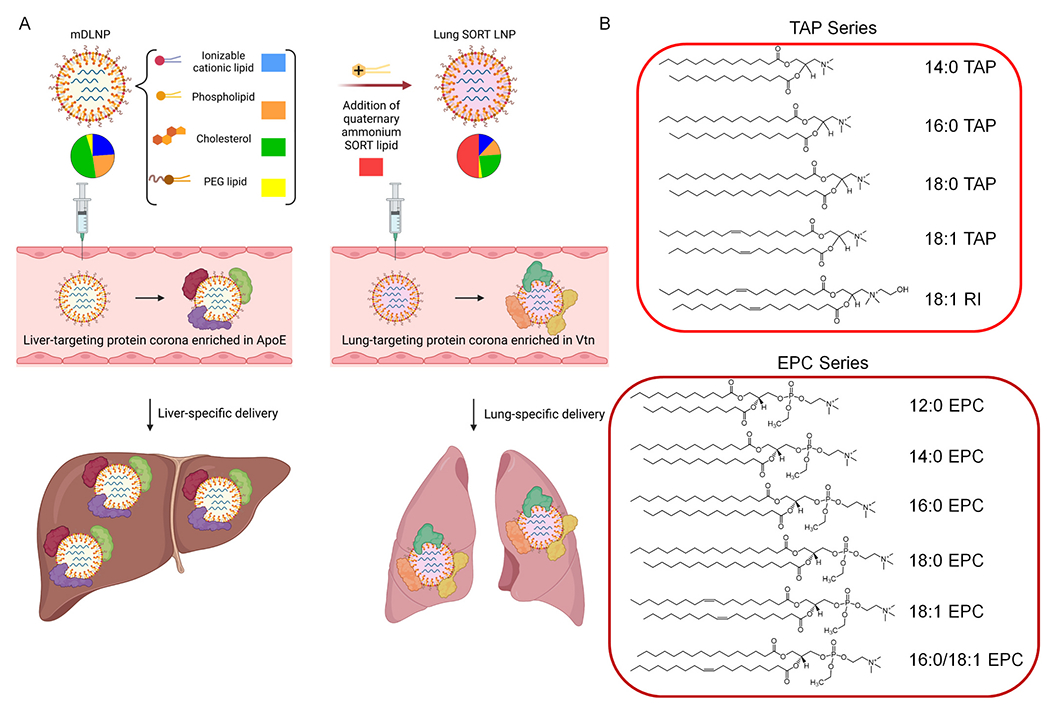

Fig. 1.

Addition of a quaternary ammonium lipid to an LNP formulation in a suitable quantity enables mRNA delivery to the lungs via an endogenous targeting mechanism [22]. (A) Conventional LNPs, like mDLNP, are formulated with four lipid components and bind to a specific set of proteins in the plasma, including ApoE, following intravenous injection, resulting in significant hepatic delivery. The addition of a permanently cationic quaternary ammonium lipid as a 5th component (typically 40–60% of total lipids), known as a SORT molecule, re-targets mRNA delivery from the liver to the lungs by generating a protein corona highly enriched in distinct set of plasma proteins from those involved in liver delivery, including Vtn. (B) The chemical space of commercially-available quaternary ammonium lipids can be partitioned into two molecular series: the TAP series and the EPC series. In this study, each lipid was incorporated into mDLNP as a SORT molecule and tested for its capacity to re-target mRNA delivery to the lungs.

Understanding the determinants of extrahepatic LNP delivery has laid a foundation for further optimization of SORT LNPs for therapeutic applications. For example, SORT LNPs which employ a permanently cationic quaternary ammonium lipid as a SORT molecule enable lung-specific mRNA delivery and genome editing of both pulmonary endothelial and epithelial cells [19]. Lung-targeting SORT LNPs feature a notably different protein corona from liver-targeting LNPs, with a reduced enrichment of ApoE, complement components, and immunoglobulins as well as increased enrichment of vitronectin (Vtn) among other proteins (Fig: 1a) [22]. As lung-targeting SORT LNPs enable protein expression in pulmonary epithelial cells, they have great potential to treat Cystic Fibrosis by exogenous production of the wild-type Cystic Fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein or genome editing of pathogenic mutations in the CFTR genetic locus with further optimization.

In our previous work, lung-specific mRNA expression was initially achieved using the quaternary ammonium lipid 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (18:1 TAP, also referred to as DOTAP) as a SORT molecule [19]. However, several similar lipids have been prepared using chemical synthesis and are available as alternatives to 18:1 TAP that could affect key aspects of mRNA delivery to the lungs, such as total protein production, tissue-specificity, and the cellular populations that are transfected. Given the key role of the protein corona in the proposed endogenous targeting mechanism of SORT LNPs, it is feasible that changes to LNP chemistry could alter protein corona composition in a manner that affects the aforementioned delivery outcomes [22]. Indeed, previous investigations of the protein corona have demonstrated that both molecular composition and surface chemistry can affect which proteins most avidly associate with a nanoparticle [24–28]. However, limited work has characterized the functional consequences of these changes to the protein corona on nanoparticle delivery outcomes in vivo, emphasizing the need to better characterize biological interactions that underly the organ-targeting properties of LNPs [22,29]. Investigating how changes to the chemical structure of SORT molecules belonging to the same biophysical class affect LNP protein corona and mRNA delivery efficacy can bridge the gap between biological interactions and delivery outcomes for a clinically-relevant nanoparticle system and further elucidate which protein(s) are critical for endogenous targeting of the lungs.

Here, we characterized how adjusting the chemical structure of the quaternary ammonium lipid used as a SORT molecule impacts an LNP’s mRNA delivery profile and associated protein corona. A series of commercially-available lipids were selected and partitioned into two chemical series (Fig. 1b) [30]. We found that changes to the SORT molecule chemical structure have a negligible impact on LNP physicochemical properties but do affect the in vivo potency and selectivity of lung-targeted mRNA delivery. Furthermore, the choice of SORT molecule affects the identity and quantity of protein corona components in a manner that correlates with the lung-selectivity of mRNA delivery. Although certain key proteins implicated in lung delivery were identified as common between the formulations, no single protein was identified as a univariate correlate of lung selectivity. Rather, it appears that an ensemble of multiple proteins may help determine the specificity of mRNA delivery to extrahepatic organs. Collectively, our findings reveal a nuanced relationship exists between protein corona composition and organ-targeting outcomes, highlighting the need for deeper mechanistic characterization of the biological interactions that underpin LNP targeting in vivo [22].

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Development and characterization of alternative lung-targeting SORT LNPs

Four-component LNPs for liver delivery are formulated from ionizable cationic lipid, zwitterionic phospholipid, cholesterol, and poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) lipid molecules [3]. Previously, our lab optimized a four-component formulation (mDLNP) to efficiently deliver fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase mRNA for the normalization of liver function in a mouse model of hepatorenal tyrosinemia type 1 [11]. For this formulation, we used an ionizable cationic amino lipid from a chemical library, 5A2-SC8 [31], the phospholipid 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), cholesterol (Chol), and the PEG lipid 1,2-dimyristoyl-rac-glycero-3-methoxypolyethylene glycol-2000 (DMG-PEG2k). These components were combined at relative molar ratios of 23.8/23.8/47.6/4.8 of 5A2-SC8/DOPE/Chol/DMG-PEG2k for optimal mRNA delivery in vivo [11]. Later studies from our lab revealed that adding 18:1 TAP (DOTAP) to mDLNP as a SORT molecule at a proportion of 50 mol% (11.9/11.9/23.8/2.4/50 5A2-SC8/DOPE/Chol/DMG-PEG2k/18:1 TAP) leads to the formation of a protein corona enriched in factors distinct from those involved in liver delivery, including Vtn, thereby re-targeting mRNA delivery from the liver to the lungs in a tissue-specific manner (Fig. 1a) [19,22].

To determine how the chemical structure of the SORT molecule impacts lung-specific mRNA delivery and plasma protein interactions, we prepared LNPs that incorporate 50 mol% of one of eleven additional commercially-available permanently cationic quaternary ammonium lipids as SORT molecules (Fig. 1b). Two lipid series were considered: the trimethylammonium propane (TAP) series and the ethylphosphocholine (EPC) series [30]. Common to all of these molecules is 1) a hydrophobic domain consisting of two alkyl tails of variable carbon length and degree of unsaturation and 2) a quaternary ammonium headgroup that features a permanent positive charge [30]. For the TAP series, there is a short alkyl linker connecting the quaternary ammonium headgroup to the diester hydrophobic domains. For the EPC series, there is an ethylated phosphate group in the linker region. The ethyl substitution maintains the positive charge on the ammonium headgroup. While the TAP series are fully synthetic and have no biological analogue, the EPC series is based upon naturally-occurring phosphatidylcholine lipids found in cellular membranes whose negatively-charged phosphate group has been neutralized through ethylation [32].

The size, zeta potential, and RNA encapsulation efficiency for all 12 formulations was assessed (Fig. S1). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements showed that LNPs had hydrodynamic diameters within the range of 108 to 151 nm (Fig. S1a). Additionally, mDLNP carried a slightly negative, near neutral ζ-potential of −4.5 mV, while the five-component LNPs carried a slightly positive, near neutral ζ-potential, between 0.323 and 7.06 mV (Fig. S1b). Lastly, all formulations efficiently encapsulated mRNA, although the inclusion of a permanently cationic quaternary ammonium lipid as a SORT molecule led to greater encapsulation efficiency compared to mDLNP (Fig. S1c). No notable trends were observed between the chemical structures of the chosen SORT molecules and the physicochemical properties of the formulated LNPs. Given that all SORT molecules could be successfully incorporated into LNPs with similar attributes, all formulations were evaluated for in vivo delivery and protein corona formation.

2.2. SORT molecule structure impacts the efficacy of mRNA delivery to the lungs

The chemical structure of the lipid components of an LNP have been well established to impact both the potency and tissue-specificity of mRNA delivery [3,18,30]. Changes to LNP chemistry could affect the biological interactions that underpin efficacious targeting, providing us with a rationale as to why changes to the SORT molecule structure could alter delivery efficacy. Image-based methods to assess expression of a fluorescent or luminescent reporter are commonly used to determine where and how much protein is being produced from mRNA delivered by administered LNPs. To examine the organ-targeting properties of LNPs prepared with different SORT molecules, we intravenously injected C57BL6/J mice with five-component SORT formulations encapsulating firefly luciferase (FLuc) mRNA. Six hours later, the mice were euthanized and organs excised for bioluminescence imaging. Measurements of total flux produced by the organs are proportional to the total amount of FLuc protein translated from the exogenously administered mRNA, allowing us to estimate the potency and tissue-selectivity of the eleven SORT formulations. As a control, mice were treated with the original liver-targeted formulation, mDLNP, to demonstrate how the incorporation of any quaternary ammonium lipid as a SORT molecule is a driver of mRNA delivery to the lungs.

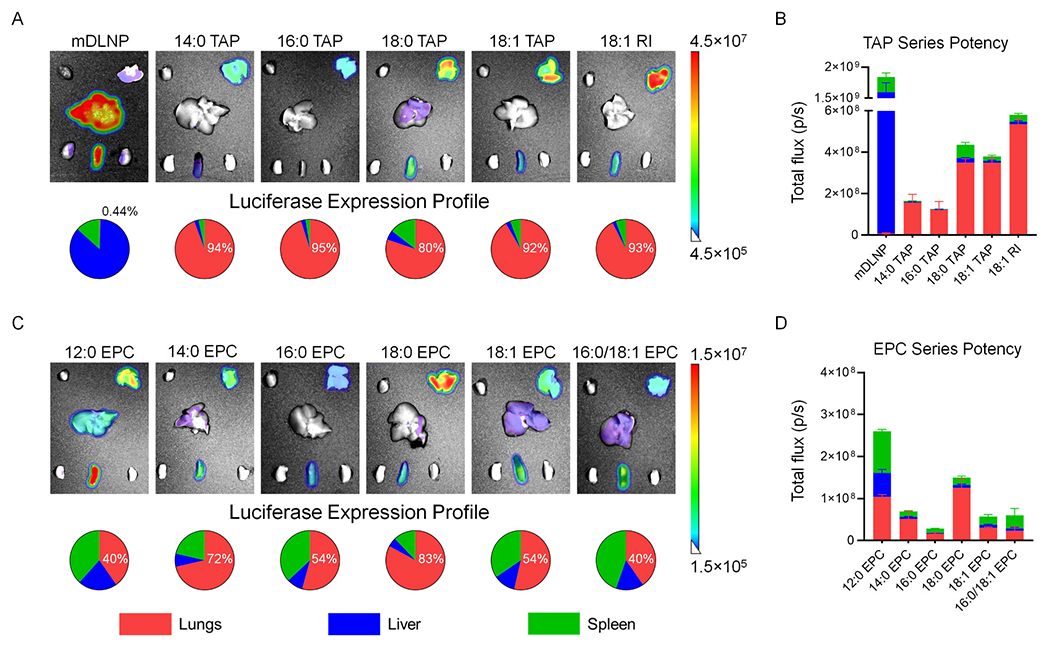

The base four-component formulation, mDLNP, has previously demonstrated effective delivery of mRNA to the liver in an ApoE-dependent manner [11,22]. Further engineering of the formulation through the incorporation of 18:1 TAP as a SORT molecule led to highly selective and potent mRNA delivery to the lungs for protein expression and CRISPR-Cas gene editing [19,20]. As alternatives to 18:1 TAP, other TAP lipids were employed as SORT molecules, all of which resulted in highly potent and specific expression of FLuc in the lungs (Fig. 2a). Compared to 18:1 TAP, 14:0 and 16:0 TAP yielded a lower lung bioluminescence when used as SORT molecules despite similar tissue-specificity (Fig. 2b). Although 18:0 TAP is equally potent as 18:1 TAP for FLuc mRNA delivery to the lungs, there is a larger degree of off-target delivery to the spleen and the liver, reducing the lung-selectivity of 18:0 TAP SORT LNPs to 80%, the lowest among the TAP series (Fig. 2a). Meanwhile, 18:1 RI, which nearly shares the same chemical structure as 18:1 TAP but substitutes one of the methyl groups in the headgroup with an ethanol motif, outperforms 18:1 TAP as a SORT molecule, yielding >1.5 fold more potent mRNA delivery to the lungs while maintaining the same level of selectivity (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

The incorporation of one of eleven quaternary ammonium lipids as a SORT molecule to mDLNP reduces mRNA delivery to the liver and spleen while enhancing mRNA delivery to the lungs with varying degrees of potency and selectivity. (A) Ex vivo luminescence images of major organs excised from C57BL6/J mice intravenously injected with four-component mDLNP or five-component TAP series SORT LNPs encapsulating FLuc mRNA. Beneath the images, pie charts profile the tissue-specificity of FLuc expression in the lungs, liver, and spleen and quantify the percent expression detected in the lungs (0.1 mg/kg, 6 h post-injection, n = 3). (B) Quantification of the total luminescent flux produced by FLuc expressed in the lungs, liver, and spleens of mice treated with mDLNP or TAP series SORT LNPs (0.1 mg/kg, 6 h post-injection, n = 3). (C) Ex vivo luminescence images of major organs excised from C57BL6/J mice intravenously injected with five-component EPC series SORT LNPs encapsulating FLuc mRNA. Beneath the images, pie charts profile the tissue-specificity of FLuc expression in the lungs, liver, and spleen and quantify the percent expression detected in the lungs (0.1 mg/kg, 6 h post-injection, n = 3). (D) Quantification of the total luminescent flux produced by FLuc expressed in the lungs, liver, and spleens of mice treated with mDLNP or EPC series SORT LNPs (0.1 mg/kg, 6 h post-injection, n = 3). Data represented as mean ± SEM.

Next, the members of the EPC series were investigated for their capacity to engineer lung-targeting LNPs. Compared to mDLNP, SORT LNPs incorporating EPC molecules could all deliver mRNA to the lungs (Fig. 2c). Within this series, 12:0 and 18:0 EPC produced the most potent mRNA delivery to the lungs (Fig. 2d). However, compared to 18:0 EPC, which had 83% of the total luminescent flux produced in the lungs, the use of 12:0 EPC as a SORT molecule resulted in significantly greater off-target delivery to the spleen and liver, reducing the lung-selectivity of mRNA delivery to 40%. Other lipids from the EPC series had between 2- to 10-fold lower activity than 12:0 EPC and 18:0 EPC SORT LNPs as well as lung-selectivity of 72% or less (Fig. 2d).

Collectively, all eleven quaternary ammonium molecules could be incorporated into mDLNP as SORT molecules and shift mRNA delivery to the lungs. Interestingly, the potency and selectivity of lung delivery depended on the chemical structure of the SORT molecule within and between the two lipid series, aligning with previous work demonstrating how changes to lipid chemistry can affect the efficacy of both lipoplexes and LNPs [32–34]. Overall, 18:1 RI and 18:0 EPC were identified as the lead SORT molecules within their respective lipid series for potent, lung-specific delivery of FLuc mRNA. However, the EPC series showed slightly less potent and selective delivery of FLuc mRNA in lungs when compared with the TAP series (Fig. 2b,d). Notably, the EPC SORT molecules with most potent lung delivery, 12:0 and 18:0 EPC, had comparable delivery efficacy as the least potent TAP SORT molecules, 14:0 and 16:0 TAP. To further verify that these findings were consistent across multiple mRNA cargoes, we delivered human erythropoietin (hEPO) mRNA using leading formulations and found 18:1 RI facilitated the highest levels of protein translation (Fig. S2). hEPO could be accurately quantified in the blood as a secreted protein to provide an additional readout on LNP efficacy. Despite belonging to the same biophysical class, we hypothesize that these small changes to the SORT molecule structure may alter the composition of the protein corona that drives endogenous targeting of the lungs, thereby impacting delivery efficacy [22,35].

2.3. Lead SORT molecules enable similar cell transfection profiles

Pathogenic mutations are molecular defects that can create disorder within specific cell types and cause disease within specific organ systems [36]. Application of mRNA for either protein replacement therapy or genome editing to remedy pathogenic mutations requires sufficient access to the affected cellular population(s) to generate a desired biological effect, either protein expression or editing of genomic DNA. Given the importance of understanding the intra-organ tropism of mRNA delivery for therapeutic applications [35,37], we characterized which cells are transfected by lung-targeting LNPs that incorporate leading SORT molecules. Even further, differences in the protein corona composition may affect which cells are targeted by an LNP, providing further justification for characterizing the relationship between LNP chemistry and cellular transfection.

To assess the lungs cells targeted by LNPs based on alternative SORT molecules, we treated a genetically-engineered tdTomato (tdTom) reporter mouse model with mRNA encoding Cre recombinase. In this model, a stop cassette is bookended by loxP sites, thereby preventing expression of the fluorescent tdTom protein. Following translation of Cre from the exogenously administered mRNA, the stop cassette is removed to induce expression of tdTom (Fig. 3a) [19]. In the previously performed Luc and hEPO assays, the total amount of protein produced by targeted cells are quantified, providing a measure of overall protein production that may not be directly coupled to the number of cells transfected. In contrast, using the tdTom model, the total amount of fluorescence measured is proportional to the number of cells in which a Cre recombination event occurs, providing an estimate of how many cells are targeted by a given formulation rather than the levels of mRNA activity in the target organ. Additionally, the transfection efficiency of specific cell populations can be elucidated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

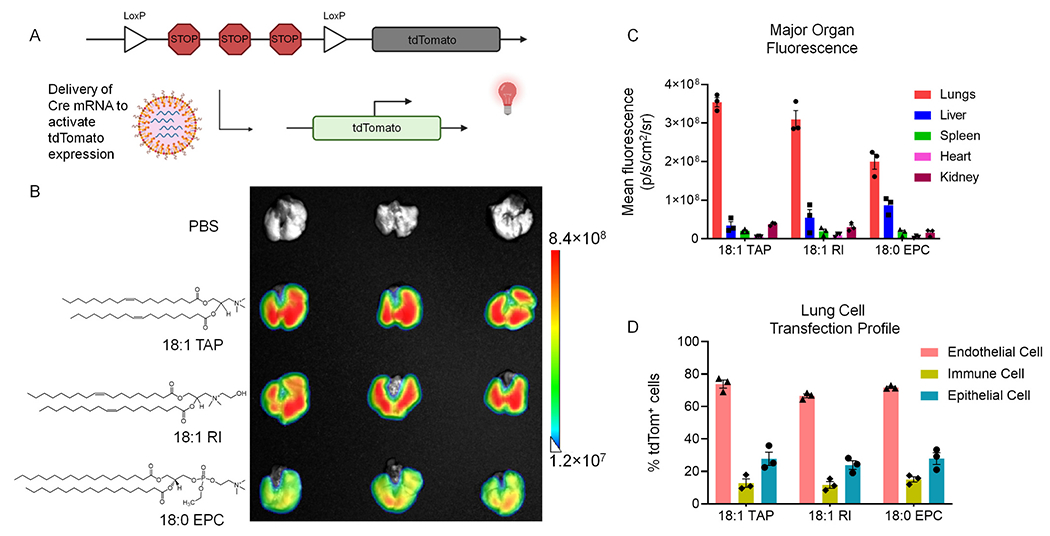

Fig. 3.

Lead SORT molecules enable transfection and genome editing of therapeutically-relevant cells of the lungs. (A) Depiction of genetic induction of tdTom expression following intracellular delivery of Cre mRNA by lung-targeting SORT LNPs. Translation of Cre from LNP-delivered mRNA removes the stop cassette that represses tdTom expression, yielding fluorescence in cells where functional mRNA delivery occurs. (B) Fluorescence imaging of lungs excised from tdTom mice two days following treatment with a single dose of Cre mRNA encapsulated in lung-targeting SORT LNPs that employ either 18:1 TAP, 18:1 RI, or 18:0 EPC as SORT molecules (0.3 mg/kg). (C) Ex vivo fluorescence imaging measurement of mean tdTom fluorescence in major organs removed from tdTom mice treated with Cre mRNA (0.3 mg/kg, 2 days post-injection, n = 3). (D) FACS quantification of the percent of tdTom+ endothelial, epithelial, and immune cells in the lungs of tdTom mice treated with a single dose of Cre mRNA (0.3 mg/kg, 2 days post-injection, n = 3). Data represented as mean ± SEM.

The top-performing SORT molecules from the TAP series and EPC series were compared to the current gold standard of 18:1 TAP for the delivery of Cre mRNA. To account for autofluorescence from the tissue, tdTom mice injected with PBS were used as a control. Two days after intravenous injection of LNPs encapsulating Cre mRNA, the tdTom mice were sacrificed and organs excised for ex vivo fluorescence imaging. Specific organs were imaged together for each group, allowing for ready comparison of tdTom fluorescence induced by the different formulations (Fig. 3b, S3). All formulations induced a high level of tdTom fluorescence in the lungs ranging between 2.0 × 108 and 3.5 × 108 p/s/cm2/sr (Fig. 3b). The lowest tdTom fluorescence was detected in the lungs of mice treated with 18:0 EPC-containing LNPs while the greatest fluorescence was measured in mice treated with 18:1 TAP-containing LNPs.

When considering the tissue-specificity of tdTom fluorescence, the use of 18:0 EPC as a SORT molecule produced more off-target signal in the liver compared to the other SORT molecules, aligning with the previous finding that formulations that utilize EPC series lipids are less lung-selective (Fig. 3c). Notably, the use of 18:1 TAP and 18:1 RI as SORT molecules yielded an average lung: liver tdTom fluorescence ratio of ~12 and ~ 9, respectively, whereas the use of 18:0 EPC as a SORT molecule yielded a ratio of ~2.5, driven by both reduced tdTom fluorescence in the lungs and increased fluorescence in the liver (Fig. 3c, S3). Greater delivery to off-target organs by 18:0 EPC SORT LNPs may result from differential interactions with plasma proteins compared to 18:1 TAP and 18:1 RI SORT LNPs that either promote liver targeting or reduce lung selectivity.

To pinpoint the individual lung cells successfully reached by the leading lung-targeting SORT LNPs, we employed FACS and an antibody panel capable of individually labelling endothelial (CD31+), immune (CD45+), and epithelial (EpCam+) cells (Fig. S4). For all formulations, endothelial cells were most efficiently transfected, followed by epithelial cells, then immune cells (Fig. 3d). The ratio of epithelial to endothelial tdTom positivity was similar for all formulations, ranging between 0.36 and 0.39, suggesting that all three SORT molecules can efficaciously deliver mRNA to the deeper tissues of the lung.

Collectively, these results indicate that SORT molecules from both the TAP and EPC series are capable of transfecting multiple cell populations in the lungs with high efficiency. The relative proportions of each cell population targeted by these LNPs was consistent between the three formulations, suggesting all have similar intra-organ tropisms. Delivery to epithelial cells is of particular interest for therapeutic applications, due to their involvement in the pathology of multiple diseases including cystic fibrosis [4], as well as for increasing basic knowledge regarding molecular mechanisms involved in nanoparticle transport in vivo. Unlike the fenestrated endothelium of the liver, which provides LNPs with access to the hepatic parenchyma via passive diffusion out of the vasculature [17], the pulmonary endothelium is continuous [38]. Presumably, the continuous endothelial barrier would prevent delivery to the deeper tissues of the lungs. Thus, it remains necessary to characterize the mechanism(s) responsible for the functional delivery of Cre mRNA to the epithelium we observed here (Fig. 3d). Some of these possible mechanisms, which have been previously identified for the transport of macromolecules or nanoparticles across continuous endothelium, could include transcytosis via caveolae [39], hitchhiking upon cells migrating into the lungs [40,41], re-secretion of internalized mRNA or LNPs by cells like macrophages [42,43], or a combination of these processes which could potentially be affected by protein corona-mediated interactions.

2.4. SORT molecule structure alters protein corona composition in a manner correlative with delivery outcomes

Previous investigations of the factors that govern the tissue-specificity of SORT LNPs revealed an endogenous targeting mechanism which defines where in the body mRNA is delivered (Fig. 1a) [18,22]. After intravenous administration, PEG lipid on the LNP surface will spontaneously desorb, allowing distinct proteins to recognize the underlying SORT molecules now exposed on the LNP surface [22]. Cells highly expressing the cognate receptors of the surface-bound proteins can interact and uptake the LNPs through receptor-mediated mechanisms, promoting functional mRNA delivery within specific organs [22]. Additionally, interactions between plasma proteins and nanoparticles can be impacted by a nanoparticle’s molecular composition and surface properties [24–28]. Thus, we hypothesized that changing the chemical structure of a SORT molecule within a specific biophysical class could lead to subtle changes in the identities and quantities of the constituent of the LNP protein corona, resulting in the differences we observed for tissue-specificity when using different quaternary ammonium lipids as SORT molecules (Figs. 2, 3).

To examine the biological interactions between lung-targeting SORT LNPs and plasma proteins, we implemented a protocol we previously developed to isolate protein-LNP complexes from bulk plasma after an ex vivo incubation at physiological temperature [22]. Following isolation, LNPs were disrupted using 2 wt% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and excess lipids were removed from the samples to provide a mixture of plasma proteins suitable for analysis using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and mass spectrometry proteomics (Figs. 4, 5). For each of the eleven possible SORT molecules, three independent batches of LNPs were formulated and characterized to ensure the reproducibility and reliability of the isolated protein corona (Fig. S5). mDLNP was employed as a relevant control to define how the addition of a SORT molecule to a four-component liver-targeting formulation yields a distinct protein corona composition to drive extrahepatic delivery. To ensure that the proteins detected in the protein corona samples were truly associated with the LNPs, rather than plasma components that coprecipitated during the centrifugation protocol, native plasma was subject to the same isolation protocol. After undergoing the protein-LNP isolation protocol, native plasma did not form a pellet discernible to the naked eye nor were any bands stained on an SDS gel, suggesting that all proteins detected in the LNP protein corona samples are a component of the corona (Fig. S6).

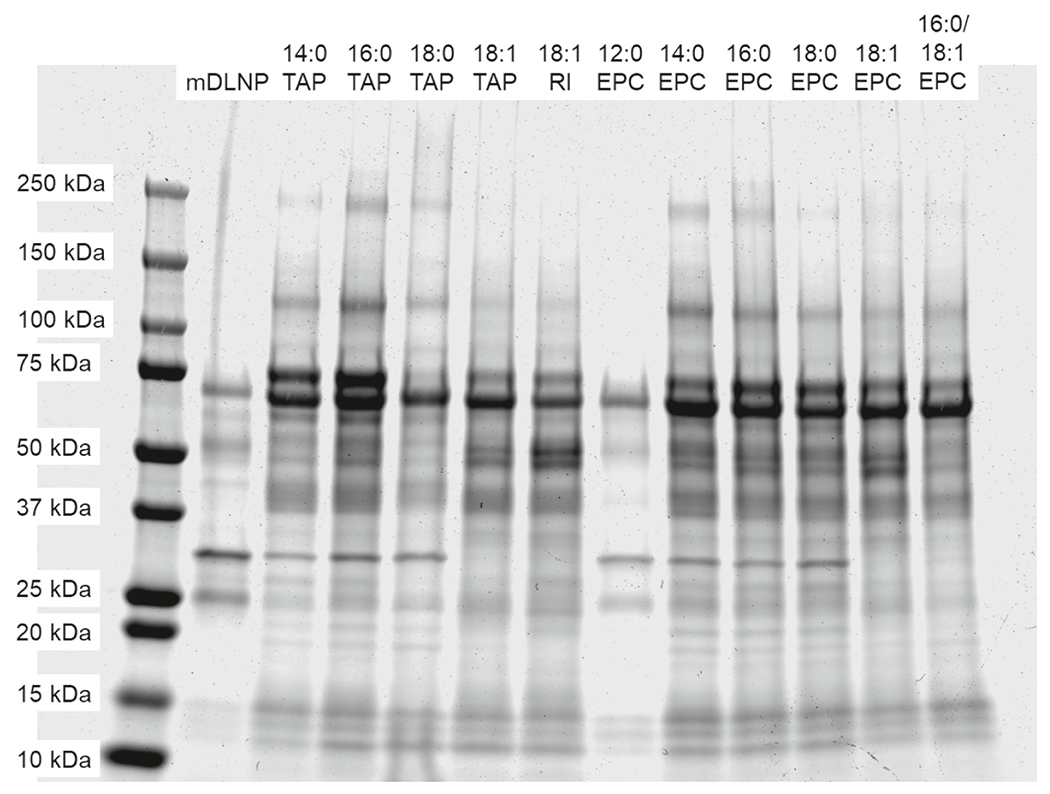

Fig. 4.

SDS-PAGE of the protein corona of four-component liver-targeting mDLNP or five-component lung-targeting SORT LNPs. While all lung-targeting SORT LNPs bind to similar plasma proteins, there are subtle differences in the identities and quantities of bound proteins that may affect in vivo delivery outcomes.

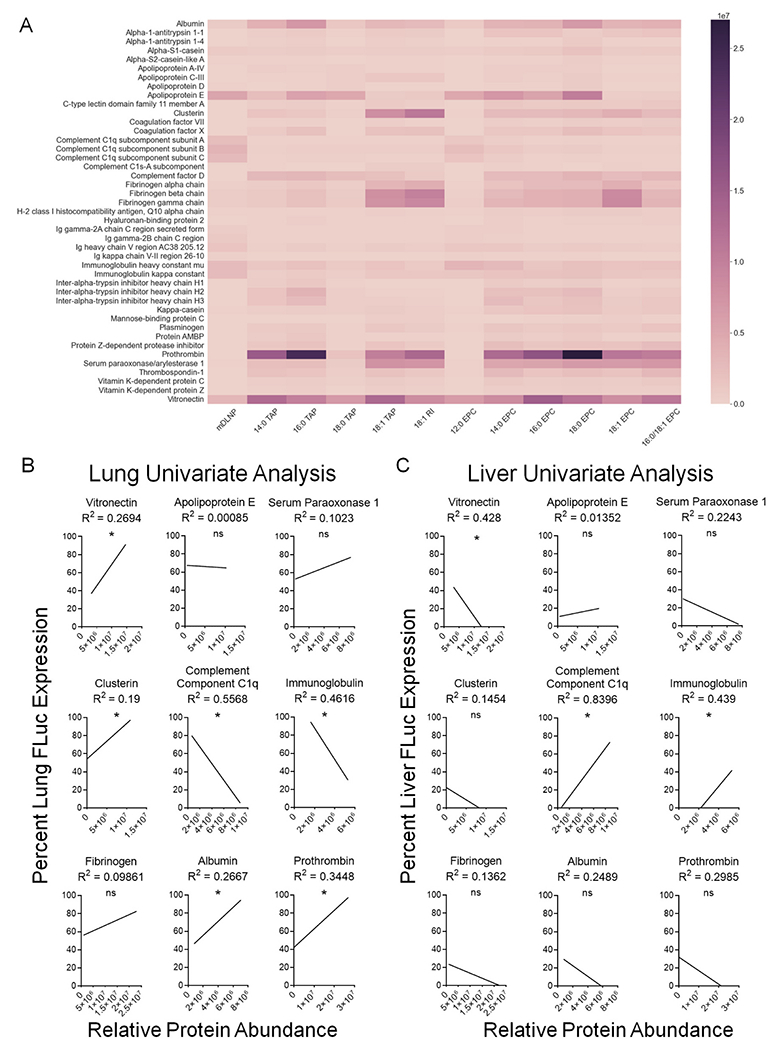

Fig. 5.

SORT molecule chemical structure impacts the identities and quantities of protein corona constituents in a manner that correlates with the specificity of mRNA delivery to the lungs. (A) Protein corona fingerprint of four-component liver-targeting mDLNP or five-component lung-targeting SORT LNPs (n = 3). (B) Univariate analysis of the lung specificity of FLuc mRNA delivery as a function of relative protein abundance. Vitronectin, clusterin, albumin, and prothrombin are positively correlated with lung delivery in a significant manner whereas complement component C1q subunits and immunoglobulin chains are negatively correlated with lung delivery. (C) Univariate analysis of the liver specificity of FLuc mRNA delivery as a function of relative protein abundance. Vitronectin is negatively correlated with liver delivery in a significant manner whereas complement component C1q subunits and immunoglobulin chains are positively correlated with liver delivery. (*; p < 0.05).

To begin, we used SDS-PAGE to qualitatively characterize and compare the protein corona of mDLNP and the different lung-targeting SORT LNPs (Fig. 4). The addition of a fifth component to mDLNP leads to notable differences in the composition and quantity of plasma proteins that bind. Namely, there is increased enrichment of bands between 20 and 25 kDa, around 40 to 50 kDa and near 65 kDa. Between the different lung-targeting LNPs, there was differential enrichment of bands around 30, 34, 75, and 125 kDa, among others (Fig. 4). These differences in protein corona were reproducible with three independently-formulated batches of LNPs incubated with separate aliquots of plasma, supporting the validity of the observed interactions (Fig. S5). All formulations tested were found to be stable in serum for at least 48 h, suggesting that the protein corona does not destabilize the LNPs within their expected time in the systemic circulation (Fig. S7) [44].

To identify and quantify the observed differences in protein corona composition between the different LNPs, we analyzed all 36 samples using mass spectrometry proteomics (Fig. 5). We anticipate that the most abundant proteins are those most likely to be functionally relevant, so we focused our analysis on proteins which are present at a level of 2.5% of the total abundance or greater for at least one sample. For all quaternary ammonium lipids incorporated into mDLNP as SORT molecules, there was an increased enrichment of Vtn, a factor previously identified as most important for lung targeting [45] that was further validated as functional in multiple cell lines expressing its cognate receptor αvβ3 integrin. We also previously showed that 18:1 TAP Lung SORT LNPs target the lungs in an ApoE independent manner in vivo. Here, with this expanded collection of Lung SORT lipids, we further noted binding of other proteins including prothrombin, clusterin, serum paraoxonase 1, fibrinogen, and albumin (Fig. 5a). Additionally, there was a decrease in the abundance of factors like complement component C1q subunits and immunoglobulin chains (Fig. 5a). Notably, there were differences in the rank order of most highly enriched proteins as well as the abundances of each protein based on the choice of SORT molecule, highlighting how LNP chemistry can influence the subset and quantities of plasma proteins that associate with lung-targeting SORT LNPs after intravenous injection.

Through an analysis of the relationship between SORT molecule structure and protein enrichment, we can gain a deeper understanding of how LNP chemistry influences the protein corona. In comparison to TAP SORT molecules, EPC SORT molecules generally facilitated increased adsorption of ApoE, complement component C1q subunits, serum paraoxonase 1, and immunoglobulin chains (Fig. 5a). Within each series, the worst-performing formulation, either 18:0 TAP or 12:0 EPC, tended to have similar protein binding patterns as liver-targeting mDLNP (Fig. 5a). Overall, these findings suggest that lipid series chemistry can bias an LNP to interact with specific proteins that may drive differences in the specificity of organ-specific mRNA delivery. Additionally, while there did not appear to be any correlations between saturated alkyl tail length and protein binding for the TAP series, increasing the alkyl tail length of an EPC SORT molecule increased binding of albumin, fibrinogen, prothrombin, and serum paraoxonase 1 (Fig. 5a). Compared to SORT molecules that had fully saturated alkyl tails, SORT molecules that featured at least one alkyl tail with an unsaturated bond led to notably reduced ApoE enrichment but increased binding of other proteins to the LNP surface, such as clusterin, serum paraoxonase 1, and fibrinogen (Fig. 5a). Finally, in comparison to 18:1 TAP, the use of 18:1 RI as a SORT molecule, which substitutes one of the methyl groups found in the headgroup of 18:1 TAP with an ethanol group, increased binding of clusterin and fibrinogen while slightly reducing Vtn binding (Fig. 5a). These findings demonstrate that the chemistry of individual LNP components can alter protein corona composition.

Since the protein corona may impact the endogenous mechanisms responsible for both targeting of the lungs as well as de-targeting of the liver, univariate analyses of the relationship between protein abundances and FLuc mRNA delivery to the lungs and the liver were performed for the most highly enriched proteins (Fig. 5b,c). Significant positive correlations between protein abundance and lung-selectivity were identified for Vtn, clusterin, albumin, and prothrombin while significant negative correlations were seen for complement component C1q subunits and immunoglobulin chains (Fig. 5b). Similarly, Vtn was negatively correlated with liver delivery whereas enrichment of both complement component C1q subunits and immunoglobulin chains was found to be positively correlated with liver delivery in a significant manner (Fig. 5c). Interestingly, proteins like complement components and immunoglobulins are typically associated with detrimental delivery outcomes because they tag nanoparticles for sequestration by cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), some of which reside within the liver and the spleen [18,46,47]. Thus, it is plausible these proteins could reduce the lung-specificity of SORT LNP delivery by promoting increased MPS interactions. Similarly, outside work suggests that clusterin may help circulating nanoparticles avoid MPS sequestration, therefore serving as another factor that promotes lung selectivity. It is also possible that the increased off-target transfection of liver cells in the tdTom mouse model observed when using 18:0 EPC as a SORT molecule, rather than 18:1 TAP or 18:1 RI, could be driven by a corresponding ~10-fold higher enrichment in ApoE binding, a crucial factor known to promote liver accumulation of LNPs (Fig. 3c, S3) [16].

Generally, LNPs incorporating EPC SORT molecules tended to have protein coronas enriched in factors negatively correlated with lung-specificity compared to LNPs incorporating TAP SORT molecules, which may explain the superior in vivo performance of the TAP series (Fig. 5). Notably, no single protein could fully account for the total variation in lung specificity observed between SORT molecules, suggesting that the ensemble of corona proteins may determine delivery outcomes. Altogether, these observations reveal a nuanced relationship exists between SORT molecule structure and protein corona that can be manipulated by tuning the chemistry of a lipid’s hydrophobic domain or headgroup. Further, these changes in protein corona composition and abundances may have a tangible impact on the tissue-specificity of lungtargeting SORT LNPs (Fig. 2). The tissue-specificity of mRNA delivery could be impacted by the presence of proteins that promote delivery to the lungs, like Vtn and clusterin, as well as proteins that are implicated in delivery to off-target sites, such as immunoglobulins and complement components. It is conceivable that differences in the protein corona composition between LNPs that transfect only the endothelium [29] versus SORT LNPs that transfect the endothelium and epithelium [19,22] may drive these observed differences in intra-organ targeting. The implementation of more complex approaches, like multivariate analysis or machine learning, could provide greater insight into the interplay between the protein corona and organ-targeting properties of SORT LNPs to further clarify the corona proteins most crucial for lung delivery and the associated LNP compositions that generate a protein corona that yields a desired delivery outcome [48–50]. This would facilitate rational design of improved delivery systems by identifying suitable LNP compositions which enrich for proteins that drive delivery to the target site while reducing binding of proteins responsible for non-specific delivery.

3. Conclusions

The targeted and potent delivery of mRNA is essential to the success of protein replacement and genome editing therapies seeking to remedy genetic diseases of the lungs. Whereas conventional LNPs typically accumulate in the liver following intravenous administration [14,16,17], thereby limiting their scope of applications, SORT LNPs enable site-specific mRNA delivery to therapeutically-relevant cells within the liver, spleen, or lungs of mice [19–22]. Crucially, LNPs that incorporate different classes of SORT molecules bind to distinct subsets of plasma proteins that likely drive the unique and specific organtargeting outcomes of SORT LNPs [22]. Building on that foundation, we explicated how changes to the chemical structure within the same class of SORT molecule affect lung-specific delivery efficacy and the biological interactions involved in endogenous targeting to better understand the impact of the protein corona on organ-targeted drug delivery.

Through our studies of the TAP and EPC lipid series as SORT molecules, we found that SORT molecule chemistry can affect the potency and selectivity of mRNA delivery to the lungs. Notably, the TAP series outperformed the EPC series by yielding higher protein production and tissue-specificity across multiple mRNA cargoes. The top-performing molecules identified from both series, 18:1 RI and 18:0 EPC, are able to access lung endothelial cells as well as epithelial cells in the deeper tissues of the lungs making them useful for developing SORT formulations for therapeutic protein expression and genome editing. Improved SORT molecules could be designed by tailoring alkyl tail and headgroup functionalities based on structure-property relationships derived from this dataset to promote interactions with the proteins most essential for delivery to the target site and transfection of the desired cell type(s).

Additionally, we discovered that SORT molecule chemical structure impacts plasma protein interactions in a manner that appears to be related to the lung-specificity of mRNA delivery. As we had previously observed, Vtn was a key protein associated with all lung-targeting SORT LNPs and is correlated with the tissue-specificity of mRNA delivery to the lungs [22]. However, lung targeting appears to be driven by binding of an ensemble of proteins that could play different roles in determining the potency and selectivity of mRNA delivery, such as de-targeting the liver or binding to receptors highly expressed on the luminal side of pulmonary endothelial cells to promote transfection of lung tissue, rather than a single factor. Given the complexity of the relationship between SORT molecule chemical structure and protein corona composition, more intricate modelling approaches could further clarify how individual proteins impact delivery. This would be supported by collection of a larger dataset to profile the protein corona more comprehensively across different SORT formulations [48–50]. Further mechanistic experiments that clarify the functional effect of major proteins identified as important for delivery within these datasets, such as how genetic knockout of key proteins impacts delivery [47] or profiling of the cellular receptors that facilitate nanoparticle uptake [51], would deepen our understanding of the intersection between LNP chemistry, plasma protein interactions, and organ-targeting outcomes [18]. Ultimately, this would provide a foundation for rational design and optimization of formulation components that minimize delivery to off-target tissues and further reveal how to harness endogenous proteins for organ-targeted nanoparticle drug delivery.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Materials

5A2-SC8 was synthesized and purified by following published protocols [31]. The phospholipid 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) and all quaternary ammonium lipids, 14:0 TAP, 16:0 TAP, 18:0 TAP, 18:1 TAP, 18:1 RI, 12:0 EPC, 14:0 EPC, 16:0 EPC, 18:0 EPC, 18:1 EPC, and 16:0/18:1 EPC, were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Cholesterol, sucrose, sodium dodecyl sulfate, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. DMG-PEG2k was purchased from NOF America Corporation. The ReadyPrep 2-D Cleanup Kit, 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gels, 2× Laemmli Buffer, 10× Tris/Glycine/SDS, and Bio-Safe™ Coomassie Stain were purchased from Bio-Rad. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) Ultramicro cuvettes Quant-iT RiboGreen Assay Kit, and Invitrogen MEGAscript SP6 transcription kit were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. Pur-A-Lyzer Midi Dialysis Kits (MWCO, 3.5 kDa) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. D-Luciferin (sodium salt) was purchased from Gold Biotechnology. Innovative Research C57BL/6 Mouse Plasma K2EDTA and N1-Methylpseudouridine-5′-Triphosphate were purchased from Fisher Scientific. ScriptCap Cap1 Capping System was purchased from CellScript. Red blood cell lysis buffer, cell staining buffer, TruStain FcX antibody, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse CD31, Pacific Blue-conjugated anti-mouse CD45, Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-mouse EpCAM, and Ghost Dye Red 780 were purchased from BioLegend. Human Erythropoietin/EPO DuoSet ELISA and DuoSet ELISA Ancillary Reagent Kit 2 were purchased from R&D Systems.

4.2. In vitro transcription of mRNA

mRNAs encoding FLuc, hEPO, and Cre recombinase were synthesized by in vitro transcription. The coding fragments of each protein were prepared using PCR and cloned into a pCS2 + MT plasmid backbone featuring customized 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions as well as poly A sequences. In vitro transcription was conducted using the Invitrogen MEGAscript SP6 transcription kit (ThermoFisher) but with N1-methylpseudouridine-5′-triphosphate replacing the typical uridine triphosphate. Next, a Cap1 cap structure was installed to the 5′ end of the mRNA using the ScriptCap Cap1 Capping System (CellScript).

4.3. LNP preparation

The ethanol dilution method was used to formulate mRNA LNPs [23]. To prepare mDLNP, the base four component formulation, a mixture of 23.8 mol% 5A2-SC8, 23.8 mol% DOPE, 47.6 mol% cholesterol, and 4.8 mol% DMG-PEG2K was diluted in ethanol and rapidly mixed with 10 mM, pH = 4.0 citrate buffer containing mRNA using a pipette at a volume ratio of 3:1 (aqueous:organic phases). For all lungtargeting SORT formulations, a mixture of 11.9 mol% 5A2-SC8, 11.9 mol% DOPE, 23.8 mol% cholesterol, 2.4 mol% C14-PEG2K, and 50 mol % of the chosen SORT molecule was prepared in ethanol. Once again, this lipid mixture was rapidly mixed with 10 mM, pH = 4.0 citrate buffer containing mRNA using a pipette at a volume ratio of 3:1. Ten minutes after mixing, the LNP formulations were diluted to a desired concentration using 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS). For in vivo experiments, LNPs were dialyzed against 1× PBS for 2 h using the Pur-A-Lyzer Midi Dialysis Kit (MWCO 3.5 kDa).

4.4. LNP characterization

LNP size, polydispersity index, and ζ-potential were measured using DLS (Malvern MicroV model; He—Ne laser, λ = 632 nm). After formulation, LNPs were diluted in 1× PBS to a final concentration of 1.0 ng mRNA /μL PBS before measurement of hydrodynamic diameter by DLS. After DLS, the LNPs were diluted 10-fold in DI water to measure ζ-potential. To measure mRNA encapsulation, a RiboGreen assay was performed. LNPs were diluted to a final concentration of 0.5 ng mRNA /μL PBS and mRNA standards were prepared at concentrations of 0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, and 2.0 ng/μL. All samples and standards were added to a 96-well black opaque polystyrene microplate, followed by addition of RiboGreen reagent that had been diluted 200× in PBS. Then the amount of free mRNA was measured in the Infinite F/M200 Pro microplate reader (Tecan) for fluorescence using an excitation of 485 nm and an emission 535 nm. The total mRNA concentration (free and encapsulated) was determined by adding 0.5% Triton X-100 to each well before conducting a second measurement of fluorescence using an excitation of 485 nm and an emission 535 nm. The encapsulation efficiency was calculated as:

4.5. In vivo FLuc mRNA delivery and quantification

C57BL6/J mice between 6 and 8 weeks old were injected with mDLNP or a lung-targeting SORT LNPs that incorporate one of eleven quaternary ammonium lipids at a dosage of 0.1 mg FLuc mRNA/kg bodyweight (n = 3). After 6 h, mice were injected with D-Luciferin (150 mg/kg, IP) and bioluminescence imaging was conducted with an AMI-HTX in vivo imaging system (Spectral Instruments Imaging). Total luminescence of target organs was quantified using Aura Imaging Software (Spectral Instruments Imaging). Tissue-selectivity was quantified as:

4.6. In vivo hEPO mRNA delivery and quantification

C57BL6/J mice between 6 and 8 weeks old were injected with lungtargeting SORT LNPs that employ either 18:1 TAP, 18:1 RI, or 18:0 EPC as a SORT molecule at an mRNA dosage of 0.3 mg hEPO mRNA/kg bodyweight. Blood was collected retro-orbitally at 6, 24, 48, and 72 h after injection to assess serum levels of hEPO protein. To prepare serum, whole blood was allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min prior to centrifugation at 2000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Samples were maintained at −80 °C before analysis using ELISA. Quantification of serum hEPO concentration was performed using a sandwich ELISA developed in-house with the Human Erythropoietin/EPO DuoSet ELISA and DuoSet ELISA Ancillary Reagent Kit 2 (R&D Systems).

4.7. In vivo Cre mRNA delivery and quantification

LNP formulations encapsulating Cre mRNA were intravenously injected into tdTom mice at a dosage of 0.3 mg mRNA/kg bodyweight (n = 3). Two days later, mice were sacrificed and organs were excised for fluorescence imaging using an AMI-HTX in vivo imaging system (Spectral Instruments Imaging). To account for background fluorescence, tdTom mice injected with PBS were included as a cohort for this experiment. Mean organ fluorescence was measured as:

4.8. Lung cell isolation

Lungs excised from tdTomato mice were placed onto ice cold PBS following resection. 1× lung digestion media was prepared from RPMI media supplemented with 2% wt/vol BSA, 300 U/mL collagenase, and 100 U/mL hyaluronidase [52]. The lung tissue was cut into small pieces using a razor blade, then transferred into a 50 mL tube containing 10 mL of digestion media. The tube was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h while shaking at 180 rpm. After incubation, the homogenized lung cell solution was pipetted up and down several times to remove cell clumps and finally filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer into a fresh 50 mL tube. The filter was washed with a wash buffer composed of cold PBS and 2% fetal bovine serum prior centrifuging the sample at 1200 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 10 mL of cold wash buffer. Next, the red blood cells (RBCs) were lysed by resuspending the cell pellet in 5 mL of 1× RBC lysis buffer (BioLegend) and incubating at room temperature for 5 min. Following the incubation, 10 mL of wash media was added to the sample. Once again, the sample was centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min. Finally, the RBC free cell pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of cell staining buffer (BioLegend) prior to antibody staining for flow cytometry.

4.9. Lung cell staining and flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions obtained from lungs excised from tdTomato mice were pre-blocked with TruStain FcX™ antibody (BioLegend) for 15 min. Next, 100 μL of cell suspension was incubated with 1 μL of an antibody cocktail composed of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse CD31, Pacific Blue-conjugated anti-mouse CD45, and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-mouse EpCAM antibodies (BioLegend) for 15 min on ice. Ghost Dye Red 780 (BioLegend) was used to identify the dead cells. Next, excess antibodies were removed by washing the cell pellet with cell staining buffer three times. Finally, the cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μL of cold cell staining buffer and kept on ice until analysis by flow cytometer. Cells were then analyzed by Becton Dickenson (BD) LSR Fortessa flow cytometer. The resulting data were analyzed by FlowJo software (BD) to assess the percentage of tdTomato positive cells within each population stained for in the lungs.

4.10. Isolation of LNP protein corona

To isolate the LNP protein corona, the method we previously developed was employed [22]. Briefly, C57BL6/J mouse plasma was added to each LNP solution, diluted to a lipid concentration of 1 g/L, at a 1:1 volume ratio and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. A 0.7 M sucrose solution was prepared by dissolving solid sucrose in MilliQ water. The LNP/plasma mixture was loaded onto a 0.7 M sucrose cushion of equal volume to the mixture and centrifuged at 15,300 g and 4°C for 1 h. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed with 1× PBS. Next, the pellet was centrifuged at 15,300 g and 4°C for 5 min, and the supernatant was removed. Washing was performed twice more for a total of three washes. Following the final wash, the pellet was resuspended in 2 wt% SDS. Excess lipids were removed from each using the ReadyPrep 2-D Cleanup (Bio-Rad). The resulting pellet from the cleanup step was resuspended in 2× Laemmli buffer. The same procedure was repeated with plasma diluted directly in 1× PBS at a 1:1 volume ratio to verify that no plasma components were precipitating on their own due to the centrifugation protocol.

4.11. SDS-PAGE characterization of protein corona

Plasma proteins isolated from the surface of LNPs were loaded onto a 4–20% TGX Precast Protein Gel. Samples were allowed to stack for 10 min at 90 V before increasing the running voltage to 150 V until the dye front reached the bottom edge of the gel. Proteins were visualized by staining the gel for 1 h in Bio-Safe Coomassie Stain followed by a 1 h destain in water at room temperature. The gel was then imaged using a Licor Scanner.

4.12. LNP serum stability

The serum stability of SORT LNPs was investigated by incubating the LNPs with a serum solution at 37 °C. Four-component mDLNP and five-component SORT LNPs were suspended with PBS buffer containing 10% of FBS and incubated at 37 °C. At time points of 0, 8, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, and 168 h, LNP hydrodynamic diameter was measured using DLS (Malvern MicroV model; He—Ne laser, λ = 632 nm).

4.13. Mass spectrometry proteomics analysis of plasma proteins

To prepare samples for mass spectrometry proteomics, 10 uL of the plasma protein mixture isolated from the LNPs was loaded on to a 4–20% TGX gel. Samples were run at 90 V for 10 min, allowing them to stack. Then, the gel was stained using Bio-Safe Coomassie Stain to fix and visualize the proteins. After destaining for 1 h, the protein bands were cut out using a razor blade and diced into small cubes with a volume of approximately 1 mm3. The cubes were added to a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube and stored at 4°C until being submitted to the University of Texas Southwestern Proteomics Core for mass spectrometry analysis. A Thermo QExactive HF mass spectrometer was used to identify and quantify the constituents of the protein samples. The identified proteins were ordered based on their abundance/MW. A custom Python Script was written to rank the most abundant proteins and plot them as a heat map.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) (R01 5R01EB025192-06) and National Cancer Institute (R01 CA269787-01), the Welch Foundation (I-2123-20220031), a Sponsored Research Agreement with ReCode Therapeutics, and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) (SIEGWA18XX0, SIEGWA21XX0). We acknowledge the UTSW Small Animal Imaging Resource supported in part by the NCI (P30CA142543) and the UTSW Proteomics Core. S.A.D. acknowledges financial support from the NIH Pharmacological Sciences Training Grant (GM007062) and the NIH Molecular Medicine Training Grant (GM109776). Cartoons for the figures were created using Biorender.com.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sean A. Dilliard: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yehui Sun: Investigation. Madeline O. Brown: Investigation. Yun-Chieh Sung: Investigation. Sumanta Chatterjee: Investigation. Lukas Farbiak: Investigation. Amogh Vaidya: Investigation. Xizhen Lian: Investigation. Xu Wang: Investigation. Andrew Lemoff: Supervision, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Daniel J. Siegwart: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The University of Texas System has filed patent applications related to the SORT technology, with some authors listed as co-inventors. D.J.S. is a co-founder, consultant, and member of the scientific advisoiy board of ReCode Therapeutics which has licensed intellectual property from UT Southwestern.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.07.058.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D, Spector SA, Rouphael N, Creech CB, McGettigan J, Kehtan S, Segall N, Solis J, Brosz A, Fierro C, Schwartz H, Neuzil K, Corey L, Gilbert P, Janes H, Follmann D, Marovich M, Mascola J, Polakowski L, Ledgerwood J, Graham BS, Bennett H, Pajon R, Knightly C, Leav B, Deng W, Zhou H, Han S, Ivarsson M, Miller J, Zaks T, Group CS, Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, New Engl. J. Med 384 (2021) 403–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Perez JL, Perez Marc G, Moreira ED, Zerbini C, Bailey R, Swanson KA, Roychoudhury S, Koury K, Li P, Kalina WV, Cooper D, Frenck RW Jr., Hammitt LL, Tureci O, Nell H, Schaefer A, Unal S, Tresnan DB, Mather S, Dormitzer PR, Sahin U, Jansen KU, Gruber WC, Group CCT, Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine, N. Engl. J. Med 383 (2020) 2603–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hou X, Zaks T, Langer R, Dong Y, Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery, Nat. Rev. Mater 6 (2021) 1078–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kim J, Jozic A, Lin Y, Eygeris Y, Bloom E, Tan X, Acosta C, MacDonald KD, Welsher KD, Sahay G, Engineering lipid nanoparticles for enhanced intracellular delivery of mRNA through inhalation, ACS Nano 16 (2022) 14792–14806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E, A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity, Science 337 (2012) 816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR, Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage, Nature 533 (2016) 420–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR, Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage, Nature 551 (2017) 464–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, Raguram A, Liu DR, Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA, Nature 576 (2019) 149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jiang L, Park JS, Yin L, Laureano R, Jacquinet E, Yang J, Liang S, Frassetto A, Zhuo J, Yan X, Zhu X, Fortucci S, Hoar K, Mihai C, Tunkey C, Presnyak V, Benenato KE, Lukacs CM, Martini PGV, Guey LT, Dual mRNA therapy restores metabolic function in long-term studies in mice with propionic acidemia, Nat. Commun 11 (2020) 5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Musunuru K, Chadwick AC, Mizoguchi T, Garcia SP, DeNizio JE, Reiss CW, Wang K, Iyer S, Dutta C, Clendaniel V, Amaonye M, Beach A, Berth K, Biswas S, Braun MC, Chen H-M, Colace TV, Ganey JD, Gangopadhyay SA, Garrity R, Kasiewicz LN, Lavoie J, Madsen JA, Matsumoto Y, Mazzola AM, Nasrullah YS, Nneji J, Ren H, Sanjeev A, Shay M, Stahley MR, Fan SHY, Tam YK, Gaudelli NM, Ciaramella G, Stolz LE, Malyala P, Cheng CJ, Rajeev KG, Rohde E, Bellinger AM, Kathiresan S, In vivo CRISPR base editing of PCSK9 durably lowers cholesterol in primates, Nature 593 (2021) 429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cheng Q, Wei T, Jia Y, Farbiak L, Zhou K, Zhang S, Wei Y, Zhu H, Siegwart DJ, Dendrimer-based lipid nanoparticles deliver therapeutic FAH mRNA to normalize liver function and extend survival in a mouse model of hepatorenal tyrosinemia type I, Adv. Mater 30 (2018), e1805308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Finn JD, Smith AR, Patel MC, Shaw L, Youniss MR, van Heteren J, Dirstine T, Ciullo C, Lescarbeau R, Seitzer J, Shah RR, Shah A, Ling D, Growe J, Pink M, Rohde E, Wood KM, Salomon WE, Harrington WF, Dombrowski C, Strapps WR, Chang Y, Morrissey DV, A single administration of CRISPR/Cas9 lipid nanoparticles achieves robust and persistent in vivo genome editing, Cell Rep. 22 (2018) 2227–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O’Riordan WD, Yang CC, Ueda M, Kristen AV, Tournev I, Schmidt HH, Coelho T, Berk JL, Lin KP, Vita G, Attarian S, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Mezei MM, Campistol JM, Buades J, Brannagan TH 3rd, Kim BJ, Oh J, Parman Y, Sekijima Y, Hawkins PN, Solomon SD, Polydefkis M, Dyck PJ, Gandhi PJ, Goyal S, Chen J, Strahs AL, Nochur SV, Sweetser MT, Garg PP, Vaishnaw AK, Gollob JA, Suhr OB, Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis, N. Engl. J. Med 379 (2018) 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gillmore JD, Gane E, Taubel J, Kao J, Fontana M, Maitland ML, Seitzer J, O’Connell D, Walsh KR, Wood K, Phillips J, Xu Y, Amaral A, Boyd AP, Cehelsky JE, McKee MD, Schiermeier A, Harari O, Murphy A, Kyratsous CA, Zambrowicz B, Soltys R, Gutstein DE, Leonard J, Sepp-Lorenzino L, Lebwohl D, CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo gene editing for transthyretin amyloidosis, N. Engl. J. Med 385 (2021) 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mahley Robert W, Apolipoprotein E: cholesterol transport protein with expanding role in cell biology, Science 240 (1988) 622–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Akinc A, Querbes W, De S, Qin J, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Jayaprakash KN, Jayaraman M, Rajeev KG, Cantley WL, Dorkin JR, Butler JS, Qin L, Racie T, Sprague A, Fava E, Zeigerer A, Hope MJ, Zerial M, Sah DW, Fitzgerald K, Tracy MA, Manoharan M, Koteliansky V, Fougerolles A, Maier MA, Targeted delivery of RNAi therapeutics with endogenous and exogenous ligand-based mechanisms, Mol. Ther 18 (2010) 1357–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Akinc A, Maier MA, Manoharan M, Fitzgerald K, Jayaraman M, Barros S, Ansell S, Du X, Hope MJ, Madden TD, Mui BL, Semple SC, Tam YK, Ciufolini M, Witzigmann D, Kulkarni JA, van der Meel R, Cullis PR, The Onpattro story and the clinical translation of nanomedicines containing nucleic acid-based drugs, Nat. Nanotechnol. 14 (2019) 1084–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dilliard SA, Siegwart DJ, Passive, active and endogenous organ-targeted lipid and polymer nanoparticles for delivery of genetic drugs, Nat. Rev. Mater 8 (2023) 282–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cheng Q, Wei T, Farbiak L, Johnson LT, Dilliard SA, Siegwart DJ, Selective organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles for tissue-specific mRNA delivery and CRISPR-Cas gene editing, Nat. Nanotechnol 15 (2020) 313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wei T, Cheng Q, Min YL, Olson EN, Siegwart DJ, Systemic nanoparticle delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins for effective tissue specific genome editing, Nat. Commun 11 (2020) 3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lee SM, Cheng Q, Yu X, Liu S, Johnson LT, Siegwart DJ, A systematic study of unsaturation in lipid nanoparticles leads to improved mRNA transfection in vivo, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Eng 60 (2021) 5848–5853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dilliard SA, Cheng Q, Siegwart DJ, On the mechanism of tissue-specific mRNA delivery by selective organ targeting nanoparticles, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 118 (2021), e2109256118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang X, Liu S, Sun Y, Yu X, Lee SM, Cheng Q, Wei T, Gong J, Robinson J, Zhang D, Lian X, Basak P, Siegwart DJ, Preparation of selective organ-targeting (SORT) lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) using multiple technical methods for tissue-specific mRNA delivery, Nat. Protoc 18 (2023) 265–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Walkey CD, Chan WC, Understanding and controlling the interaction of nanomaterials with proteins in a physiological environment, Chem. Soc. Rev 41 (2012) 2780–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sebastiani F, Yanez Arteta M, Lindfors L, Cárdenas M, Screening of the binding affinity of serum proteins to lipid nanoparticles in a cell free environment, J. Colloid Interface Sci 610 (2022) 766–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tenzer S, Docter D, Kuharev J, Musyanovych A, Fetz V, Hecht R, Schlenk F, Fischer D, Kiouptsi K, Reinhardt C, Landfester K, Schild H, Maskos M, Knauer SK, Stauber RH, Rapid formation of plasma protein corona critically affects nanoparticle pathophysiology, Nat. Nanotechnol 8 (2013) 772–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Caracciolo G, Pozzi D, Capriotti AL, Cavaliere C, Piovesana S, Amenitsch H, Lagana A, Lipid composition: a “key factor” for the rational manipulation of the liposome–protein corona by liposome design, RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 5967–5975. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cedervall T, Lynch I, Lindman S, Berggard T, Thulin E, Nilsson H, Dawson KA, Linse S, Understanding the nanoparticle-protein corona using methods to quantify exchange rates and affinities of proteins for nanoparticles, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104 (2007) 2050–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Qiu M, Tang Y, Chen J, Muriph R, Ye Z, Huang C, Evans J, Henske Elizabeth P, Xu Q, Lung-selective mRNA delivery of synthetic lipid nanoparticles for the treatment of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 119 (2022), e2116271119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhang Y, Sun C, Wang C, Jankovic KE, Dong Y, Lipids and lipid derivatives for RNA delivery, Chem. Rev 121 (2021) 12181–12277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhou K, Nguyen LH, Miller JB, Yan Y, Kos P, Xiong H, Li L, Hao J, Minnig JT, Zhu H, Siegwart DJ, Modular degradable dendrimers enable small RNAs to extend survival in an aggressive liver cancer model, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113 (2016) 520–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Koynova R, MacDonald RC, Cationic O-ethylphosphatidylcholines and their lipoplexes: phase behavior aspects, structural organization and morphology, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr 1613 (2003) 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tenchov BG, Wang L, Koynova R, MacDonald RC, Modulation of a membrane lipid lamellar–nonlamellar phase transition by cationic lipids: a measure for transfection efficiency, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr 1778 (2008) 2405–2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Koynova R, Tenchov B, Wang L, MacDonald RC, Hydrophobic moiety of cationic lipids strongly modulates their transfection activity, Mol. Pharm 6 (2009) 951–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Johnson LT, Zhang D, Zhou K, Lee SM, Liu S, Dilliard SA, Farbiak L, Chatterjee S, Lin Y-H, Siegwart DJ, Lipid nanoparticle (LNP) chemistry can endow unique in vivo RNA delivery fates within the liver that alter therapeutic outcomes in a cancer model, Mol. Pharm 19 (2022) 3973–3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Doudna JA, The promise and challenge of therapeutic genome editing, Nature 578 (2020) 229–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kim M, Jeong M, Hur S, Cho Y, Park J, Jung H, Seo Y, Woo HA, Nam KT, Lee K, Lee H, Engineered ionizable lipid nanoparticles for targeted delivery of RNA therapeutics into different types of cells in the liver, Sci. Adv 7 (2021) eabf4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Huertas A, Guignabert C, Barberà JA, Bärtsch P, Bhattacharya J, Bhattacharya S, Bonsignore MR, Dewachter L, Dinh-Xuan AT, Dorfmüller P, Gladwin MT, Humbert M, Kotsimbos T, Vassilakopoulos T, Sanchez O, Savale L, Testa U, Wilkins MR, Pulmonary vascular endothelium: the orchestra conductor in respiratory diseases, Eur. Respir. J 51 (2018) 1700745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jones JH, Minshall RD, Lung endothelial transcytosis, in: Compr. Physiol, 2020, pp. 491–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Myerson JW, Patel PN, Rubey KM, Zamora ME, Zaleski MH, Habibi N, Walsh LR, Lee Y-W, Luther DC, Ferguson LT, Marcos-Contreras OA, Glassman PM, Mazaleuskaya LL, Johnston I, Hood ED, Shuvaeva T, Wu J, Zhang H-Y, Gregory JV, Kiseleva RY, Nong J, Grosser T, Greineder CF, Mitragotri S, Worthen GS, Rotello VM, Lahann J, Muzykantov VR, Brenner JS, Supramolecular arrangement of protein in nanoparticle structures predicts nanoparticle tropism for neutrophils in acute lung inflammation, Nat. Nanotechnol 17 (2022) 86–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lin ZP, Nguyen LNM, Ouyang B, MacMillan P, Ngai J, Kingston BR, Mladjenovic SM, Chan WCW, Macrophages actively transport nanoparticles in tumors after extravasation, ACS Nano 16 (2022) 6080–6092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Melamed JR, Yerneni SS, Arral ML, LoPresti ST, Chaudhary N, Sehrawat A, Muramatsu H, Alameh M-G, Pardi N, Weissman D, Gittes GK, Whitehead KA, Ionizable lipid nanoparticles deliver mRNA to pancreatic β cells via macrophage-mediated gene transfer, Sci. Adv 9 (2023) eade1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Maugeri M, Nawaz M, Papadimitriou A, Angerfors A, Camponeschi A, Na M, Hölttä M, Skantze P, Johansson S, Sundqvist M, Lindquist J, Kjellman T, Mårtensson I-L, Jin T, Sunnerhagen P, Östman S, Lindfors L, Valadi H, Linkage between endosomal escape of LNP-mRNA and loading into EVs for transport to other cells, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mui BL, Tam YK, Jayaraman M, Ansell SM, Du X, Tam YY, Lin PJ, Chen S, Narayanannair JK, Rajeev KG, Manoharan M, Akinc A, Maier MA, Cullis P, Madden TD, Hope MJ, Influence of polyethylene glycol lipid desorption rates on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of siRNA lipid nanoparticles, Mol. Ther. Nudeic Acids 2 (2013), e139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lokugamage MP, Vanover D, Beyersdorf J, Hatit MZC, Rotolo L, Echeverri ES, Peck HE, Ni H, Yoon J-K, Kim Y, Santangelo PJ, Dahlman JE, Optimization of lipid nanoparticles for the delivery of nebulized therapeutic mRNA to the lungs, Nat. Biomed. Eng 5 (2021) 1059–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chow A, Brown BD, Merad M, Studying the mononuclear phagocyte system in the molecular age, Nat. Rev. Immunol 11 (2011) 788–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bertrand N, Grenier P, Mahmoudi M, Lima EM, Appel EA, Dormont F, Lim JM, Karnik R, Langer R, Farokhzad OC, Mechanistic understanding of in vivo protein corona formation on polymeric nanoparticles and impact on pharmacokinetics, Nat. Commun 8 (2017) 777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ban Z, Yuan P, Yu F, Peng T, Zhou Q, Hu X, Machine learning predicts the functional composition of the protein corona and the cellular recognition of nanoparticles, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117 (2020) 10492–10499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lazarovits J, Sindhwani S, Tavares AJ, Zhang Y, Song F, Audet J, Krieger JR, Syed AM, Stordy B, Chan WCW, Supervised learning and mass spectrometry predicts the in vivo fate of nanomaterials, ACS Nano 13 (2019) 8023–8034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ouassil N, Pinals RL, Del Bonis-O’Donnell JT, Wang JW, Landry MP, Supervised learning model predicts protein adsorption to carbon nanotubes, Sci. Adv 8 (2022) eabm0898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ngo W, Wu JLY, Lin ZP, Zhang Y, Bussin B, Granda Farias A, Syed AM, Chan K, Habsid A, Moffat J, Chan WCW, Identifying cell receptors for the nanoparticle protein corona using genome screens, Nat. Chem. Biol 18 (2022) 1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Chatterjee S, Basak P, Buchel E, Safneck J, Murphy LC, Mowat M, Kung SK, Eirew P, Eaves CJ, Raouf A, Breast cancers activate stromal fibroblast-induced suppression of progenitors in adjacent normal tissue, Stem Cell Rep. 10 (2018) 196–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.