Abstract

PURPOSE

Oral anticancer drugs (OACDs) have become increasingly prevalent over the past decade. OACD prescriptions require coordination between payers and providers, which can delay drug receipt. We examined the association between insurance type, pursuit of copayment assistance, pursuit of prior authorization (PA), and time to receipt (TTR) for new OACD prescriptions.

METHODS

We prospectively collected data on new OACD prescriptions for adult oncology patients from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2019, including demographic and clinical characteristics, insurance type, and pursuit of PA and copayment assistance. TTR was defined as the number of days from prescription to OACD receipt. We summarized TTR using cumulative incidence and compared TTR by insurance type, pursuit of copayment assistance, and PA activity using the log-rank test.

RESULTS

Our cohort of 1,024 patients was 53% male, and 40% were younger than 65. Twenty-six percent had commercial insurance only, 16% had Medicaid only, and 59% had Medicare with or without additional insurance. Eighty-six percent of prescriptions were successfully received. Across all prescriptions, 69% involved PA activity, and 21% involved the copayment assistance process. In unadjusted analyses, prescriptions involving the copayment assistance process had longer TTR compared with those not involving assistance (log-rank P value = .005) and OACDs covered by Medicare/commercial insurance had a longer TTR compared with Medicaid (log-rank P value = .006). The PA process was not associated with TTR (log-rank P value = .124).

CONCLUSION

The process for obtaining OACDs is complex. The copayment assistance process and Medicare/commercial insurance are associated with delayed TTR. New policies are needed to reduce time to OACD receipt.

For oral anticancer drugs, copayment assistance and insurance type are associated with delayed time to receipt.

INTRODUCTION

Oral anticancer drugs (OACDs) have been available in the United States for decades, but there has been a dramatic increase in the approval of these medications by the Food and Drug Administration over the past 20 years. Since 2015, oral agents have comprised about two thirds of all newly approved oncology drugs each year. Although oral oncolytics may provide a convenient and preferable option for the appropriate patients, their use is associated with particular challenges, such as navigating adherence, insurance coverage, and affordability. Notably, oral medications are generally expensive and increasing in cost each year, consistent with overall antineoplastic drug pricing. Currently, OACDs have a mean monthly point-of-sale price exceeding $10,000 in US dollars (USD).1,2

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Oral anticancer drugs (OACDs) have become increasingly prevalent. Procuring these prescriptions through a specialty pharmacy involves coordination between providers and payers, which can delay drug receipt. This study examines the association between insurance type, pursuit of copayment assistance, pursuit of prior authorization, and time to drug receipt for new OACD prescriptions.

Knowledge Generated

The process for obtaining OACDs is nuanced and multifactorial. In the study, the copayment assistance process and Medicare/commercial insurance were associated with delayed time to receipt (TTR).

Relevance

There are multiple patient-level characteristics associated with OACD TTR. A detailed understanding of the factors associated with delayed receipt of these medications can inform new policies and interventions to facilitate timely drug delivery for all patients.

Even with insurance coverage, patients often bear the burden of considerable out-of-pocket (OOP) spending for OACDs. Copayments for a monthly supply of commonly prescribed medications range from no cost to over $20,000 (USD), and OOP costs vary by drug and insurance type.3-5 Several recent studies showed that at least a third of patients need financial assistance to afford their OACDs.4-8 One recent study showed that between 2010 and 2019 oral oncolytic prices for Medicare beneficiaries have increased beyond inflation, resulting in higher OOP spending for patients with Medicare.9 A retrospective study looking at insurance claims for over 38,000 patients with Medicare and commercial insurance showed that higher OOP costs were associated with higher rates of oral prescription abandonment and delayed initiation across cancer types.10

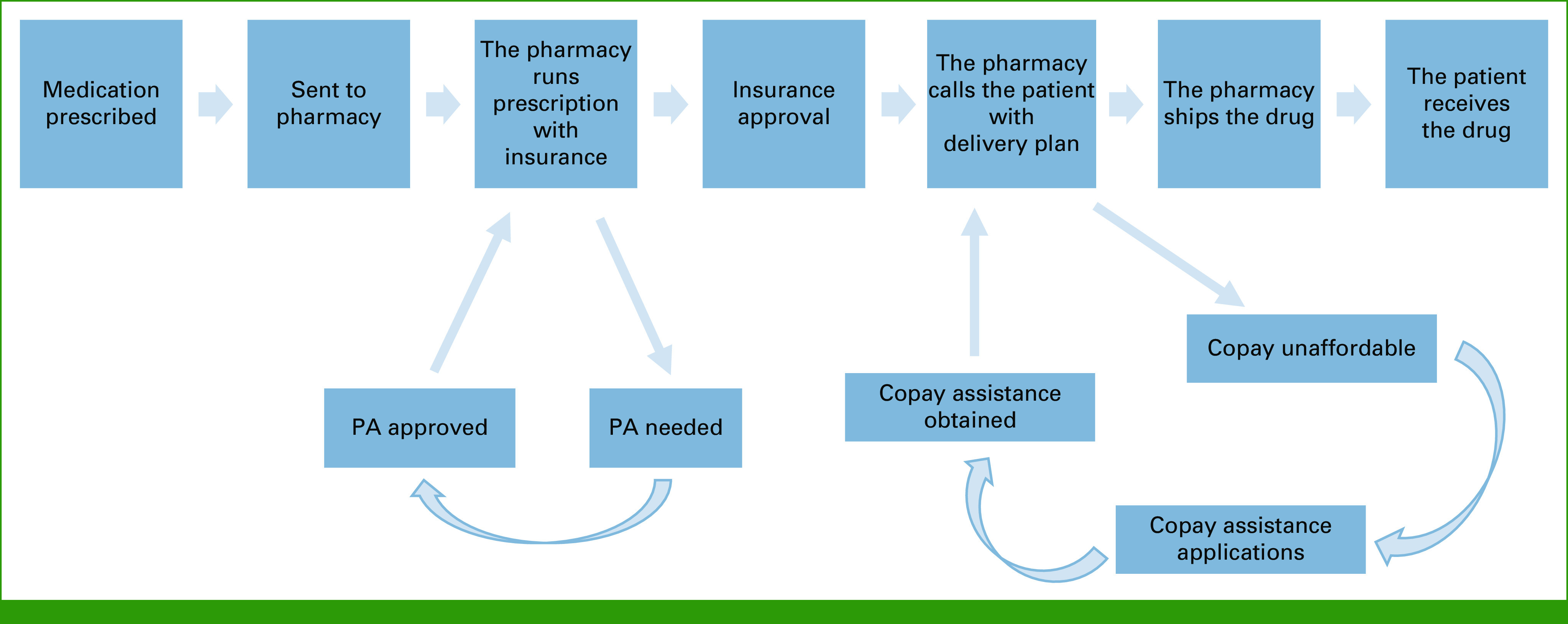

The increasing use of OACDs and their significant cost burden highlight the importance of better understanding the oral drug acquisition process. Distinct from intravenous systemic cancer treatment, the majority of OACDs in the United States are distributed directly to patients by specialty pharmacies, and the research looking at OACD delays, including our research, primarily focuses on prescriptions obtained through centralized, hospital-based specialty pharmacies.11,12 This process is complex and requires coordination and integration of multiple stakeholders on the level of the prescription, patient, and cancer center. After a prescription is generated, several additional steps are required before medication delivery, including insurance approval, which may include the prior authorization (PA) process, and pursuit of copayment assistance, if necessary. At present, no guidelines exist for acceptable time to initiation of OACDs. Although there is literature on the timeliness of intravenous chemotherapy initiation in breast, colon, and lung cancer, the research is limited and primarily focused on time from surgery or diagnosis—not prescription—to treatment.13-20 The objective of this study was to analyze the association between insurance type, the copayment assistance process, the PA process, and time to OACD receipt.

METHODS

We prospectively collected data on all new OACD prescriptions for adults seen in oncology clinic at Columbia/NewYork Presbyterian from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2019. Before September 2018, each medical oncology clinic was responsible for sending prescriptions to independent off-site specialty pharmacies and completing all insurance and financial assistance paperwork associated with prescriptions. This process primarily consisted of the nursing staff sending prescriptions to decentralized specialty pharmacies and pursuing PA and copayment assistance with occasional assistance from administrative staff. The nurses referred all prescriptions to specialty pharmacies not within the hospital system, a process that often requires multiple contacts to identify the correct specialty pharmacy. The specialty pharmacy would then contact the insurance company, and determine the next steps for prescription fill and the cost of the medication to the patient. All information regarding these activities was collected on paper case report forms that were completed by clinical and administrative staff. In September 2018, a centralized hospital-based specialty pharmacy was established and data collection was centralized. After this, all prescription coordination responsibilities shifted to the centralized specialty pharmacy with designated staff working on insurance processing as well as PA and copayment assistance, and clinical staff were no longer directly involved in OACD procurement. Once the hospital-based specialized pharmacy was in place, all OACD prescriptions were filled by the centralized pharmacy and mailed directly to patients (Fig 1A).12

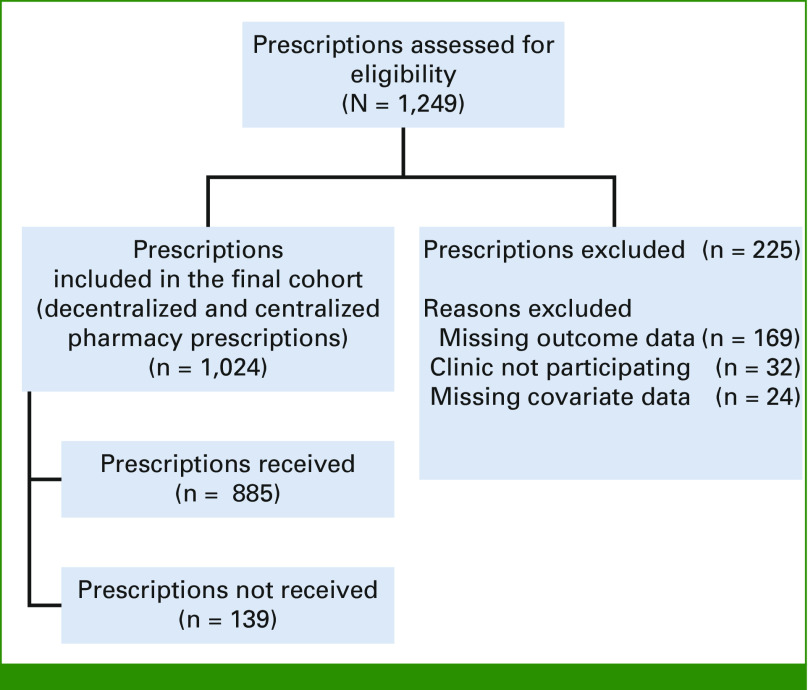

FIG 1.

STROBE diagram of prescription cohort. STROBE, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.

Throughout the study period, we collected information on patient demographic (age, sex, and race/ethnicity) and cancer clinical characteristics (metastatic solid tumor diagnosis, nonmetastatic solid tumor diagnosis, and hematologic malignancy), drugs prescribed, insurance type (Medicaid only, commercial insurance only, and Medicare with or without supplemental or secondary insurance), and specialty pharmacy interactions with payers and financial assistance groups (pursuit of the PA process and copayment assistance process, each collected as binary variables). In this study, medical insurance was obtained from the electronic medical record and used as a proxy for prescription insurance. We considered a prescription to have PA activity if PA was pursued, and copayment assistance activity if the financial assistance process was pursued, regardless of result. Prescriptions with incomplete information were excluded. Only a patient's first prescription was included, to reduce the effect of complexity from receipt of multiple prescriptions that may affect time to drug receipt.

The primary outcome for this study was time from OACD prescription to patient receipt of the drug. Patients who did not successfully receive their drug were censored at 90 days. More specifically, time to receipt (TTR) was defined as the number of days from the OACD prescription to patient receipt, as confirmed on the case report form or specialty pharmacy database, plus one day to ensure that all patients had a nonzero receipt time. This study was approved by the CUIMC Institutional Review Board (AAAR4922), and a waiver of consent was approved because the data were collected as a standard of care for all patients prescribed an OACD and because of the minimal risk of the study.

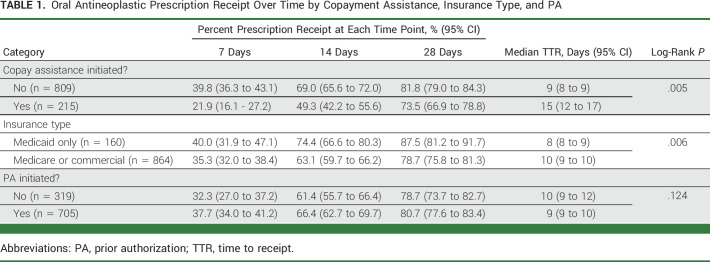

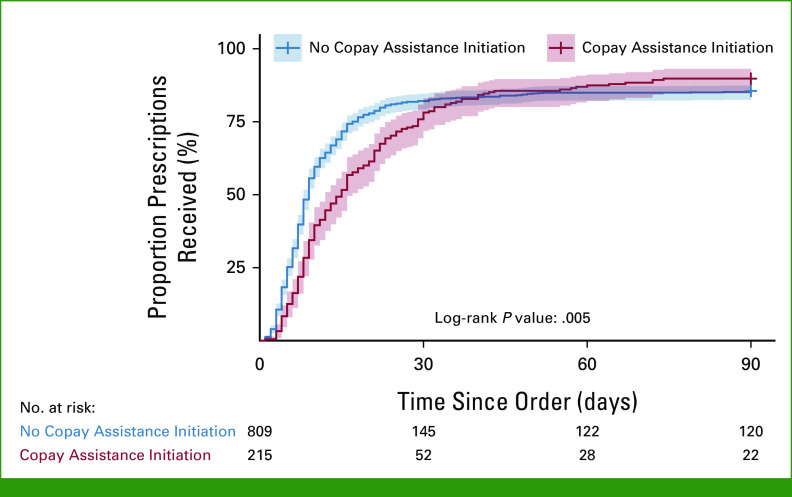

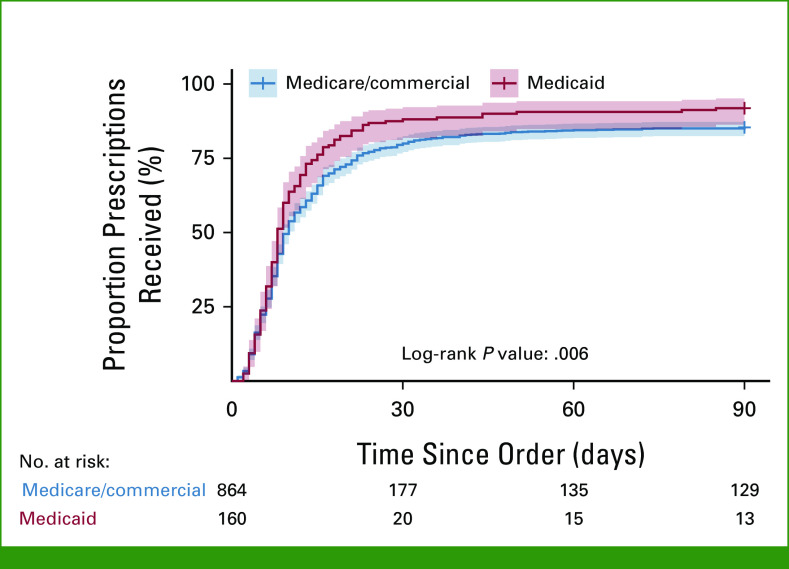

Descriptive statistics were used to report patient and prescription characteristics. Categorical variables were assessed using proportions. We used log-rank tests to examine the association between insurance type, pursuit of the copayment assistance and PA processes, and TTR. Cumulative incidence curves were used to display the associations between TTR and characteristics that were significant at P value < .05. We calculated the proportion of prescriptions received at three time points (7, 14, and 28 days) on the basis of the median TTR and clinical relevance (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Oral Antineoplastic Prescription Receipt Over Time by Copayment Assistance, Insurance Type, and PA

All analyses were done using R version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and R Studio version 1.4.1717 (RStudio, Boston, MA). Log-rank tests were calculated using the package SURVIVAL. Cumulative incidence curves were graphed using package SURVMINER.

RESULTS

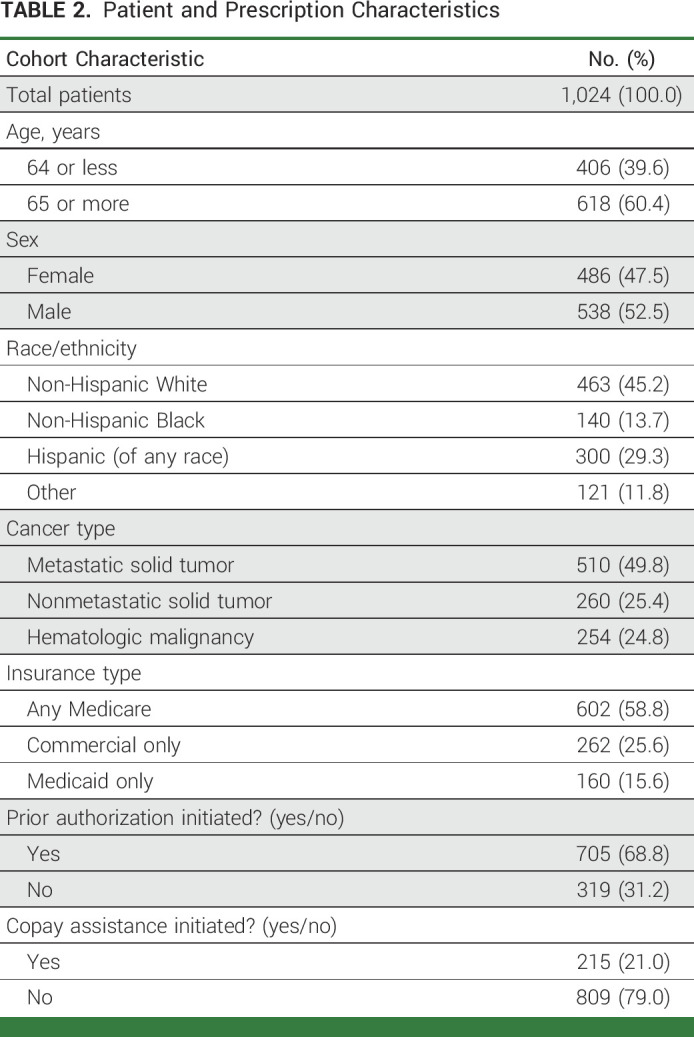

We identified 1,024 patients who were prescribed at least one new OACD during the study period (Fig 1). The study cohort was 53% male, and 40% were younger than 65 years (Table 2). The study population included 45% non-Hispanic White patients, 14% non-Hispanic Black patients, and 39% Hispanic patients of any race. Health insurance was grouped into three categories: commercial insurance only (26%), Medicaid only (16%), and Medicare with or without supplemental or secondary insurance (59%). Half of the patients (50%) had a metastatic solid tumor diagnosis, 25% had a non-metastatic solid tumor diagnosis, and the remaining 25% had a hematologic malignancy (Appendix Fig A1).

TABLE 2.

Patient and Prescription Characteristics

The majority of OACD prescriptions (69%) involved the PA process (Table 2). One fifth of prescriptions (21%) involved the copayment assistance process, and this varied by type of insurance. OACDs covered by Medicare were more likely to involve the copayment assistance process (29%) compared with those covered by commercial insurance (14%) or Medicaid (3%). The copayment assistance process was also more common among patients age 65 years and older compared with their younger peers (78% v 56%) and among those with a hematologic malignancy rather than a solid tumor diagnosis (31% v 23%). Initiation of copayment assistance did not vary by patient sex or by PA activity. There was no difference in age, sex, insurance type, or copayment assistance among patients who had a PA issued versus those who did not.

Of the 1,024 included OACD prescriptions, 86% (n = 885) were successfully received. Of prescriptions received, 22% were received after 2 weeks, and 5% of prescriptions were received after 30 days. Among all prescriptions, in unadjusted analysis, we found that OACD prescriptions involving the copayment assistance process had longer TTR compared with those that did not involve copayment assistance (log-rank P value = .005; Fig 2). Specifically, within the first 15 days, 72% (95% CI, 68.4 to 74.6) of patients who did not need the copayment assistance process had received their OACDs, while only 52% (95% CI, 44.5 to 57.9) of those who sought copayment assistance had received their OACDs. Overall, patients who did not require copayment assistance had a median TTR of 9 days (95% CI, 8 to 9), while those who sought copayment assistance had a TTR of 15 days (95% CI, 12 to 17) for OACD delivery (Table 1).

FIG 2.

Cumulative incidence curve by copayment assistance initiation.

Given that TTR was similar between Medicare and commercial insurance, we grouped these categories together. OACDs among patients with Medicare/commercial insurance had a longer TTR compared with OACDs for patients with Medicaid (log-rank P value = .006; Fig 3). Within the first 15 days, 76% (95% CI, 68.6 to 82.0) of patients with Medicaid had received their OACDs, while only 66% (95% CI, 62.5 to 68.9) of patients with Medicare/commercial insurance had received their OACDs. Patients with Medicare and commercial insurance each had a median TTR of 10 days (95% CI, 9 to 10), while those with Medicaid had a TTR of 8 days (95% CI, 8 to 9) for OACD delivery (Table 1).

FIG 3.

Cumulative incidence curve by insurance type.

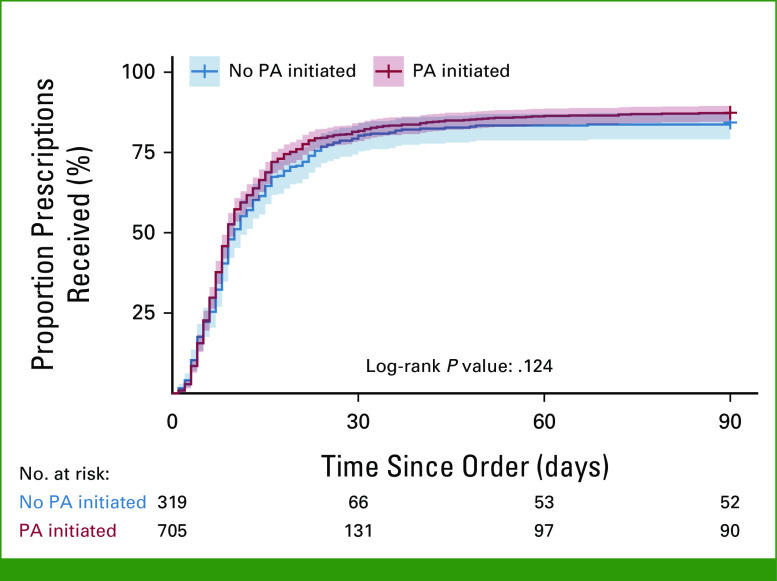

In this analysis, the PA process was not significantly associated with TTR (log-rank P value = .124; Fig 4). The median TTR of those with no PA activity was 10 days (95% CI, 9 to 12), while the median TTR of those with PA activity was 9 days (95% CI, 9 to 10; Table 1).

FIG 4.

Cumulative incidence curve by PA initiation. PA, prior authorization.

DISCUSSION

We found that delays in OACD receipt were common. A quarter of patients received their medications more than 2 weeks after prescription. Our findings also show that about 20% of OACD prescriptions involved the copayment assistance process, and among those that did, the median TTR was 6 days longer compared with prescriptions that did not involve the copayment assistance process. Notably, although the majority of OACDs involve PA activity, the PA process was not associated with a longer time to OACD receipt. Our results underscore the complexity of the OACD acquisition process and highlight barriers to timely OACD receipt, particularly for prescriptions requiring copayment assistance.

Although multiple studies have established higher rates of OACD noninitiation among patients with higher OOP costs, research on the association between copayment assistance and OACD TTR is limited and shows conflicting results.21,22 In 2020, Wang et al21 conducted a retrospective study of 270 patients and found that seeking copayment assistance for OACDs was associated with longer TTR. This study also showed that Medicare beneficiaries and uninsured patients waited longer for their medications and were more likely to need copayment assistance. By contrast, a retrospective study of 58 patients by Anders et al8 in 2015 found that PA requirement and cost-assistance programs did not affect TTR. Compared with these studies, our work assesses a larger, prospective cohort, and includes all first-time OACD prescriptions per patient within the study period. Our study supports the finding that the copayment-assistance process is associated with treatment delay. Moreover, in exploratory analysis, we found a strong association between the copayment-assistance process and insurance type, as Medicare beneficiaries were more likely to pursue copayment assistance compared with commercial insurance and Medicaid beneficiaries.

At present, there are no drug- or disease-specific guidelines that recommend acceptable time to OACD initiation. Although several retrospective reviews and meta-analyses have investigated the survival impact of treatment timeliness and found that time to curative treatment matters, many of these trials evaluated multiple treatment modalities and examined various end points.13-20 For example, one study looking at delays in adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with localized breast cancer showed that a 7-day delay in initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy increased the risk of death by 1% and that patients receiving treatment 91 or more days from surgery had a 34% increase in the risk of death. Notably, none of this research has focused on delays in oral cancer treatment. The process for obtaining OACDs differs from other cancer treatments, and typically requires multiple steps, which can include insurance processing, the PA process, and pursuit of copayment assistance. In 2017, a small single-center prospective study led by Niccolai et al22 found that pharmacy processing time, which includes confirming insurance coverage, PA, and copayment assistance, was the rate-limiting step for medication acquisition. Our work refines this observation by showing that copayment assistance, an element of pharmacy processing, is associated with significant treatment delays for patients who cannot afford their initial OACD copayment as determined between the pharmacy and insurance payer.

In addition to the association between copayment assistance and longer TTR, our study reveals that OACDs prescribed to Medicare and commercial insurance beneficiaries have a longer TTR compared with those prescribed for Medicaid beneficiaries. This difference in TTR likely reflects differences in the acquisition process across insurance types. In particular, we found a strong association between the initiation of the copayment-assistance process and insurance type, with Medicare beneficiaries more likely to require copayment assistance compared with commercial insurance and Medicaid beneficiaries. This association demonstrates that the need for copayment assistance may vary by patient-level characteristics. In this case, Medicare beneficiaries may have more barriers in obtaining OACDs compared with others. Since our insurance categories lack granularity and Medicaid is state-specific, we hesitate to draw further conclusions about specific insurance categories from this single-center study. Notwithstanding, this work highlights how cancer care could benefit from a more detailed understanding of the OACD delivery process across insurance types and subtypes, among other patient- and drug-level factors.

Notably, in our study, contrary to our hypothesis, the PA process was not associated with TTR. However, it should be noted that the majority of prescriptions in our cohort involved PA activity, which may have affected the analytical power to find a difference in this study. We did not see an association between the copayment-assistance process and PA activity or insurance type and PA activity, suggesting that this is an independent effect. Notwithstanding, existing literature cites PA as a barrier to timely treatment delivery.12,23-27 Since our work spans across insurance and OACD types, these results may reflect variation in the PA process across patient- or prescription-level factors. Although our research was not powered to distinguish between these factors, our findings highlight a need for more detailed exploration of the PA process to assess inequities in OACD access.

Our study has unique strengths. We prospectively assessed TTR using a time-to-event method among all initial OACDs that were prescribed within the study period to patients with cancer seen in outpatient clinics. This work expands upon existing literature on delays in oral medication delivery by looking at a larger, prospective cohort. We included all prescriptions, both received and not received, to avoid the bias of looking only at successfully delivered OACDs and to understand the full spectrum of delayed treatment in this context. Although the relationship between OOP cost and OACD noninitiation has been explored in the literature, our work focuses specifically on TTR and on the association between copayment assistance and treatment delays. This research sheds new light on the importance of OACD patient-facing cost and the process of seeking copayment assistance as a potential barrier to timely drug treatment.

Our work also has several limitations. The study was conducted at a single academic cancer center and may not be representative of oral oncolytic prescribing habits and fill times in other settings. We were not able to analyze 193 prescriptions because of incomplete data, and these cases were excluded from this analysis. Because of limited availability of insurance coverage details, the categories chosen may mask heterogeneity between individual plans, and Medicaid is state-specific and therefore not generalizable. In future studies, we aim to collect more detailed prescription insurance data. In addition, our study includes information about initiating the PA and copayment assistance processes, but we were not able to uniformly obtain the end result of these efforts to include in our analysis. OOP cost to the patient was also not obtained reliably, and thus could not be included in this analysis, but is an important variable to assess in future studies. Finally, given the smaller sample sizes in some of the categories, the small number of patients who did not receive their drugs, and the violation of the proportional-hazards assumption, Cox proportional-hazards and cure-rate models were not used to assess the relationship between the main covariates of interest and TTR after adjustment. With a larger data set, we would be able to estimate the effect of the covariates on both TTR and drug receipt using a cure rate model, evaluate for the changes in the estimate of the effect size over time, and adjust for additional covariates.

In conclusion, the current process for obtaining OACDs is complex and multifaceted. Overall, these findings reveal that patients who engage in the copayment-assistance process are more likely to encounter delays in treatment, particularly those with Medicare or commercial insurance. Moving forward, a more nuanced understanding of the pharmacy processing factors associated with delayed OACD receipt will enable the development of targeted interventions to facilitate timely drug delivery. Future research should aim to assess key nuances of the drug delivery process, particularly related to OOP cost and the copayment-assistance process, as well as PA activity across insurance types. Overall, this work demonstrates that insurance type and pharmacy processing factors may affect the prescription acquisition process, particularly time to medication receipt, and that a multipronged approach is needed to identify and address potential barriers early in the process to avoid delays.

APPENDIX

FIG A1.

Oral anticancer drug acquisition process. PA, prior authorization.

Shing Lee

Consulting or Advisory Role: PTC Therapeutics

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Karyopharm Therapeutics (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst)

Melissa K. Accordino

Honoraria: Incrowd

Elena B. Elkin

Research Funding: Pfizer

Jason D. Wright

Consulting or Advisory Role: UpToDate

Research Funding: Merck (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: UpToDate

Dawn L. Hershman

Consulting or Advisory Role: AIM Specialty Health

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at ASCO Quality Care Symposium, Boston, MA, September 24 - 25, 2021.

SUPPORT

Supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (R21CA242044, D.L.H.; T32CA094061, M.R.L.L.), Breast Cancer Research Foundation (D.L.H.), and the American Cancer Society (D.L.H.).

M.R.L.L. and M.P.B. contributed equally to this work as co-first authors.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request. The codes used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Morgan R.L. Lichtenstein, Melissa P. Beauchemin, Sahil D. Doshi, Melissa K. Accordino, Elena B. Elkin, Dawn L. Hershman

Administrative support: Cynthia Law, Dawn L. Hershman

Provision of study materials or patients: Cynthia Law, Melissa K. Accordino

Collection and assembly of data: Morgan R.L. Lichtenstein, Melissa P. Beauchemin, Sahil D. Doshi, Cynthia Law, Dawn L. Hershman

Data analysis and interpretation: Morgan R.L. Lichtenstein, Melissa P. Beauchemin, Rohit Raghunathan, Shing Lee, Melissa K. Accordino, Elena B. Elkin, Jason D. Wright, Dawn L. Hershman

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Association Between Copayment Assistance, Insurance Type, Prior Authorization, and Time to Receipt of Oral Anticancer Drugs

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Shing Lee

Consulting or Advisory Role: PTC Therapeutics

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Karyopharm Therapeutics (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst)

Melissa K. Accordino

Honoraria: Incrowd

Elena B. Elkin

Research Funding: Pfizer

Jason D. Wright

Consulting or Advisory Role: UpToDate

Research Funding: Merck (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: UpToDate

Dawn L. Hershman

Consulting or Advisory Role: AIM Specialty Health

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.https://www.drugpricinglab.org/issue/launch-price-tracker/ Drug Pricing Lab, 2021.

- 2.New Drugs at FDA: CDER’s New Molecular Entities and New Therapeutic Biological Products2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products

- 3. Tran G, Zafar SY. Financial toxicity and implications for cancer care in the era of molecular and immune therapies. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:166. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.03.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Swartz S, Mackenzie C, White J, et al. Between and within drug variation in copayments for common oral anti-cancer medications at an academic medical center. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:18. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ragavan MV, Scott S, Clark M, et al. Disparities in receipt of financial assistance for patients prescribed oral anti-cancer medications at an integrated specialty pharmacy J Clin Oncol 40 217 2022. 34793259 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Geynisman DM, Meeker CR, Doyle JL, et al. Provider and patient burdens of obtaining oral anticancer medications. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24:e128–e133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anders B, Shillingburg A, Newton M. Oral antineoplastic agents: Assessing the delay in care. Chemother Res Pract. 2015;2015:512016. doi: 10.1155/2015/512016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dusetzina SB, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. Specialty drug pricing and out-of-pocket spending on orally administered anticancer drugs in Medicare part D, 2010 to 2019. JAMA. 2019;321:2025–2027. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Doshi JA, Li P, Huo H, et al. Association of patient out-of-pocket costs with prescription abandonment and delay in fills of novel oral anticancer agents. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:476–482. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.5091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doshi SD, Lichtenstein MRL, Beauchemin MP, et al. Factors associated with patients not receiving oral anticancer drugs. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2236380. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.36380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beauchemin MP, Lichtenstein MRL, Raghunathan R, et al. Impact of a hospital-based specialty pharmacy in partnership with a care coordination organization on time to delivery and receipt of oral anticancer drugs. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19:e326–e335. doi: 10.1200/OP.22.00451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yorio JT, Xie Y, Yan J, et al. Lung cancer diagnostic and treatment intervals in the United States: A health care disparity? J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1322–1330. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181bbb130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Largey G, Ristevski E, Chambers H, et al. Lung cancer interval times from point of referral to the acute health sector to the start of first treatment. Aust Health Rev. 2016;40:649–654. doi: 10.1071/AH15220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olsson JK, Schultz EM, Gould MK. Timeliness of care in patients with lung cancer: A systematic review. Thorax. 2009;64:749–756. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.109330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van de Vosse D, Chowdhury R, Boyce A, et al. Wait times experienced by lung cancer patients in the BC southern interior to obtain oncologic care: Exploration of the intervals from first abnormal imaging to oncologic treatment. Cureus. 2015;7:e330. doi: 10.7759/cureus.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chan A, Woods R, Kennecke H, et al. Factors associated with delayed time to adjuvant chemotherapy in stage iii colon cancer. Curr Oncol. 2014;21:181–186. doi: 10.3747/co.21.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wasserman DW, Boulos M, Hopman WM, et al. Reasons for delay in time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e28–e35. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chavez-MacGregor M, Clarke CA, Lichtensztajn DY, et al. Delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:322–329. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yu KD, Huang S, Zhang JX, et al. Association between delayed initiation of adjuvant CMF or anthracycline-based chemotherapy and survival in breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:240. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang AA, Tapia C, Bhanji Y, et al. Barriers to receipt of novel oral oncolytics: A single-institution quality improvement investigation. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26:279–285. doi: 10.1177/1078155219841424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Niccolai JL, Roman DL, Julius JM, et al. Potential obstacles in the acquisition of oral anticancer medications. JCO Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e29–e36. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.012302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.2022 American Medical Association Prior Authorization (PA) Physician Survey2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-04/prior-authorization-survey.pdf

- 24. Lin NU, Bichkoff H, Hassett MJ. Increasing burden of prior authorizations in the delivery of oncology care in the United States. JCO Oncol Pract. 2018;14:525–528. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Agarwal A, Freedman RA, Goicuria F, et al. Prior authorization for medications in a breast oncology practice: Navigation of a complex process. JCO Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e273–e282. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.017756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dickens DS, Pollock BH.Medication prior authorization in pediatric hematology and oncology Pediatr Blood Cancer 64e26339, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kirkwood MK, Hanley A, Bruinooge SS, et al. The state of oncology practice in America, 2018: Results of the ASCO practice census survey. JCO Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e412–e420. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request. The codes used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.