Abstract

T-cell memory to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) was first demonstrated through regression of EBV-induced B-cell transformation to lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) in virus-infected peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) cultures. Here, using donors with virus-specific T-cell memory to well-defined CD4 and CD8 epitopes, we reexamine recent reports that the effector cells mediating regression are EBV latent antigen-specific CD4+ and not, as previously assumed, CD8+ T cells. In regressing cultures, we find that the reversal of CD23+ B-cell proliferation was always coincident with an expansion of latent epitope-specific CD8+, but not CD4+, T cells; furthermore CD8+ T-cell clones derived from regressing cultures were epitope specific and reproduced regression when cocultivated with EBV-infected autologous B cells. In cultures of CD4-depleted PBMCs, there was less efficient expansion of these epitope-specific CD8+ T cells and correspondingly weaker regression. The data are consistent with an effector role for epitope-specific CD8+ T cells in regression and an auxiliary role for CD4+ T cells in expanding the CD8 response. However, we also occasionally observed late regression in CD8-depleted PBMC cultures, though again without any detectable expansion of preexisting epitope-specific CD4+ T-cell memory. CD4+ T-cell clones derived from such cultures were LCL specific in gamma interferon release assays but did not recognize any known EBV latent cycle protein or derived peptide. A subset of these clones was also cytolytic and could block LCL outgrowth. These novel effectors, whose antigen specificity remains to be determined, may also play a role in limiting virus-induced B-cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a human B lymphotropic herpesvirus that has cell growth transforming ability in vitro yet is carried by the great majority of immunocompetent individuals as a lifelong asymptomatic infection. The importance of T-cell-mediated immune responses in maintaining asymptomatic persistence is emphasized by clinical observation. Thus, patients who are severely T-cell immunosuppressed either iatrogenically or through progressive human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are at risk of developing fatal EBV-associated lymphoproliferative lesions (11, 32, 37). These lesions are largely composed of EBV-transformed B cells expressing the same panel of latent cycle proteins (the nuclear antigens EBNAs 1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, and LP and the latent membrane proteins [LMPs] 1 and 2), as do the lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) that arise by EBV-induced transformation of normal resting B cells in vitro (8, 12, 54).

The ready availability of such latently infected LCLs provided stimulator cells which, when cocultured at particular ratios with autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), were able to reactivate T-cell memory and generate EBV latent antigen-specific, interleukin 2 (IL-2)-dependent, T-cell lines (39, 51). These lines, which kill the autologous LCL in short-term cytotoxicity assays, tend to be dominated by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells whose specificity was subsequently mapped to individual latent cycle proteins and their derived peptide epitopes. The EBNA3A, -3B, and -3C proteins are usually the immunodominant targets, with less frequent subdominant responses to LMP2 and EBNA1 and much less frequent responses to other antigens (5, 15, 31). As a result, immunodominant peptide epitopes from these proteins are now identified for a range of different HLA class I alleles (18, 40). Furthermore, when the content of EBV latent epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell memory was reanalyzed in ex vivo populations by single-cell techniques, such as ELISpot assays of peptide-induced gamma interferon (IFN-γ) release or staining with HLA peptide-tetramers, the patterns of immunodominance apparent from LCL-restimulated populations were confirmed (6, 44).

More recently, attention has turned to the CD4+ T-cell response to EBV latent proteins. Very little information had come from LCL-stimulated populations in that regard, the available evidence being limited to rare CD4+ T-cell clones specific for one EBNA1-derived and one EBNA2-derived epitope (16, 17). Alternative approaches, however, based on stimulating CD8-depleted PBMCs either with peptide panels, purified antigen, or antigen expressed in autologous dendritic cells, have generated polyclonal or clonal populations of CD4+ T cells specific for the relevant antigen/epitope (22, 30, 35, 36, 42, 49). Most attention has been given to EBNA1-specific responses (30, 36, 49), but it is now clear that CD4+ T-cell memory can be detected against several of the EBNAs and, in some donors, also the LMPs (22, 23). At least some of these CD4+ T-cell reactivities can also recognize and kill the autologous LCL in vitro (23, 30, 35, 36). However, such EBV epitope-specific CD4+ memory T cells are around 10-fold less abundant in PBMC populations than their CD8 counterparts (22, 23), and their relative importance as effectors controlling EBV-driven lymphoproliferations remains unknown.

One approach to this issue is to study the in vitro system which first demonstrated the existence of EBV latent antigen-specific T-cell memory (27). Experimentally infected cultures of PBMCs from EBV-immune (seropositive) donors show early B-cell proliferation but then a regression of B-cell outgrowth that coincides with the reactivation of a memory T-cell response; EBV nonimmune (seronegative) donor cultures show continued B-cell growth irrespective of the presence of autologous T cells. Much of the early literature using this system indicated that regression was associated with the appearance of EBV latent antigen-specific T cells that were operationally HLA class I-restricted in cytotoxicity assays on LCL targets (28, 29, 38, 50) and were therefore assumed to be CD8+ T cells. Indeed, the first experiments separating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from PBMC cultures strongly supported this assumption (7). A more recent analysis using natural killer (NK) and T-cell subset depletions, however, suggested that CD4+ T cells were the principal effectors of regression (33). Although the precise specificity of these effectors was never determined, it seemed likely that they were directed against EBV latent cycle antigens/epitopes since a subsequent publication showed that at least one such CD4+ T-cell specificity, to an EBNA1-derived epitope, could reproduce regression if added as a CD4+ T-cell clone to recently infected autologous B-cell cultures (34).

Here we reexamine the effect of CD16+ NK cell and of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell depletion upon regression and characterize the T-cell populations reactivated in regressing cultures using donors whose preexisting CD4+ and CD8+ memory T-cell reactivities had been rigorously mapped to defined latent cycle epitopes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood donors, PBMC cell depletions.

The experiments involved 12 EBV-seropositive (P1 to P12) and four EBV-seronegative (N1 to N4) laboratory donors of known HLA class I and class II type. Freshly isolated PBMC preparations were screened for preexisting CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell memory to known EBV latent cycle epitopes restricted through the appropriate HLA alleles in conventional ELISpot assays of peptide-induced IFN-γ release as described previously (22, 44).

In most experiments, PBMCs were first depleted of natural killer (NK) cells using anti-CD16 monoclonal antibody (MAb) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)-coated magnetic beads according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). In subsequent experiments, PBMCs were also depleted of either CD4+ T cells or of CD8+ T cells by similar methods using magnetic beads directly coated with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MAbs (Dynal).

Regression assays.

PBMCs either undepleted or depleted of particular subpopulations were exposed for 2 h at 37°C to B95.8 strain EBV preparations and then seeded into replicate flat-bottomed microtest plate wells in doubling dilutions from 3 × 105 to 1.9 × 104 cells/well as described previously (27) in RPMI 1640 and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). In some replicate wells, cyclosporine A (CSA) was added to a final concentration of 0.25 μg/ml within the first 2 days postinfection. Parallel cultures of uninfected PBMCs were set up as controls. All cultures were refed with a half change of medium every week and observed regularly for the incidence of successful B-cell outgrowth over a period of 4 to 5 weeks. In some cases, recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2) was added to a final concentration of 50 U/ml within the first 2 days of culture. The strength of regression was expressed as the initial cell seeding necessary to give a 50% incidence of regression among replicate wells as calculated using the Reed-Muench formula (39). Regression assay cultures for harvesting of cells at days 7, 14, and 21 postinfection were set up in parallel to the above but at a seeding of 106 cells/2-ml well, equivalent to a seeding of 1.5 × 105 cells/microtest plate well.

Immunofluorescence assays.

All undepleted and depleted PBMC preparations ex vivo, and all cell culture populations harvested at weekly intervals from 2-ml well regression assays, were counted, and three separate aliquots were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD16 MAb, dual-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD8 MAbs, and dual stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD19 and PE-conjugated anti-CD23 MAbs using standard protocols. All antibodies and appropriate isotype controls came from a single source (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Staining was analyzed on a Coulter Epics Excel Flow Cytometer (Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

ELISpot assays.

Unfractionated and CD4- or CD8-depleted PBMC preparations ex vivo as well as cell culture populations harvested at weekly intervals from 2-ml well regression assays were tested as responders in ELISpot assays of IFN-γ release; note that in the case of 2-ml well regression assays set up with unfractionated PBMCs, the harvested cells were divided into two aliquots, one of which was depleted of CD4+ T cells and the other of CD8+ T cells, before testing in the ELISpot assay. Peptides were synthesized as described previously (21) and used at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. Assays were conducted essentially as described previously (44), except that the range of input cell numbers varied; typically, ex vivo populations were screened at 105 and 2 × 105 cells/well, whereas cultured populations were screened at 2.5 × 104 and 5 × 104 cells/well. Numbers of spot-forming cells were counted using an automated AID ELISpot reader (Autoimmun Diagnostika, Strasbourg, Germany).

B-cell targets.

EBV-transformed LCLs were established using the B95.8 virus strain and grown either in standard FCS-supplemented medium or, where necessary, in human serum (HuS)-supplemented medium. Control B-lymphoblast targets were established by culturing PBMCs on a CD40 ligand-expressing mouse L-cell monolayer in medium supplemented with recombinant IL-4 and either HuS as described previously (3) or FCS, and they were maintained for at least 4 weeks by transferring twice weekly onto a fresh L-cell monolayer in medium as above.

T-cell cloning.

Cultures set up from CD4- or CD8-depleted PBMCs on day 0 were harvested 14 days postinfection and seeded at 0.3 and 3 cells/well into U-bottomed microtest plate wells on a feeder layer of γ-irradiated autologous LCL (104 cells/well) in FCS-supplemented culture medium supplemented with 30% supernatant from the IL-2-producing MLA 144 cell line and 50 U/ml recombinant IL-2 (21). All microcultures growing within 3 weeks were picked and further expanded as above.

Functional analysis of T-cell clones.

Clones were first screened for recognition of autologous LCL and control B-lymphoblast targets (both grown in FCS- and in HuS-supplemented medium) using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of IFN-γ release. Briefly, 500 to 1,000 T cells were cocultivated overnight with 2 × 104 target cells, then supernatant was harvested and IFN-γ content was determined against internal standards (Sigma Aldrich, Gillingham, United Kingdom) using a commercial ELISA following the manufacturer's recommended protocol (Perbio Cramlington, United Kingdom). In blocking assays, LCLs were preincubated with MAbs specific for HLA-DR (L243, ATCC clone HB-55), HLA-DQ (SPV-L3, Serotec), HLA-DP (B7.21, kindly provided by A. M. de Jong, Leiden University, The Netherlands), and HLA class I (ATCC hybridoma HB-95) for 1 h before addition of T cells in the continued presence of antibody.

All clones were then tested for recognition of EBV latent proteins or peptides again using ELISA assays for IFN-γ. Here target cells were autologous B lymphoblasts that were either infected with Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) recombinants expressing invariant chain-tagged versions of EBNA1, EBNA2, EBNA3A, EBNA3B, EBNA3C, or LMP2 or were coated with known epitope peptides with appropriate HLA restriction or with pools of overlapping 20mer peptides (5 peptides/pool) to cover the complete primary sequences of EBNA-LP and LMP1. Full details of the MVA recombinants are given elsewhere (45 and Taylor et al., manuscript in preparation).

All clones were also tested in 5-h chromium release assays on autologous LCL targets at effector target ratios of 10:1, 5:1, and 2:1 as described previously (21). Selected clones were then tested for their capacity to prevent the outgrowth of freshly infected autologous B cells as follows: B cells were isolated from PBMCs by positive selection using anti-CD19-coated Detachabeads as per the manufacturer's instructions (Dynal, Oslo, Norway), infected for 2 h with B95.8 strain EBV preparations, and bulk cultured in FCS-supplemental culture medium for 4 days before harvesting, counting, and seeding into replicate U-bottomed microtest plate wells in doubling dilutions from 104 cells/well to 75 cells/well. To some wells at each seeding density were added 2.5 × 103 effector cells of the T-cell clone. The cultures were maintained in standard FCS-supplemented medium without rIL-2 for 4 weeks and regularly monitored for successful B-cell outgrowth, confirmed where necessary by CD19 staining as described earlier.

RESULTS

Regression in CD16-depleted PBMC cultures.

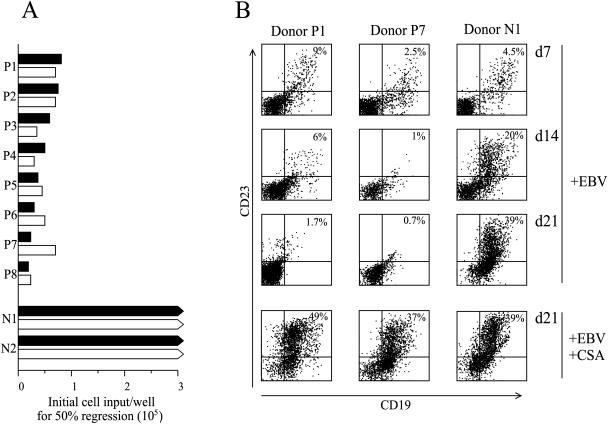

An initial series of experiments to check the possible involvement of NK cells in the induction and/or the effector phase of regression involved eight EBV-seropositive and two EBV-seronegative donors. In each case freshly isolated PBMC preparations, with or without CD16+ NK-cell depletion, were infected with B95.8 strain EBV, and the cells were seeded at doubling dilutions in microtest plate wells. The incidence of regression versus successful outgrowth of the EBV-infected B-cell population was monitored over time and scored finally at 4 to 5 weeks postinfection, and the strength of regression was expressed as the minimum cell seeding required for a 50% incidence of the effect among replicate wells. Typical results, illustrated in Fig. 1A, show that regression is only displayed by EBV-seropositive individuals, and its strength is essentially unaffected by CD16+ NK-cell depletion. To confirm that the inhibition of B-cell outgrowth recorded visually as in earlier work (27) was indeed apparent using single-cell staining, we followed the kinetics of B-cell activation in CD16-depleted PBMC cultures (set-up at a cell density equivalent to 1.5 × 105 cells/well in the regression assay) by costaining for the pan B-cell marker CD19 and the B-cell activation antigen CD23. As can be seen in Fig. 1B, there was a detectable EBV-induced activation of B cells to CD23+ status by day 7 postinfection in both seropositive and seronegative donor cultures, but such cells were completely absent by day 14 in seropositive donor P7 with strong regression and by day 21 in seropositive donor P1 with weaker regression. By contrast, in cultures from seronegative donor N1, the CD19+ CD23+ cells continued to expand, leading eventually to LCL outgrowth. Note that addition of CSA, an inhibitor of T-cell activation, postinfection completely abrogated regression in the seropositive donor cultures. All future experiments involved CD16 depletion of PBMCs as a standard initial step, thereby reducing backgrounds in subsequent ELISpot assays of IFN-γ release.

FIG. 1.

Regression in CD16+ NK-cell-depleted cultures. (A) PBMC from EBV-seropositive donors (P1 to P8) and EBV seronegative donors (N1, N2) were either undepleted (filled bars) or depleted of CD16+ NK cells (open bars) before EBV infection and then seeded in regression assays at doubling dilutions from 3 × 105 to 1.9 × 104 cells per well. Results show the cell input where 50% of the wells regressed; a low cell input indicates strong regression. Bars with arrowheads indicate the complete absence of regression at all cell inputs. (B) EBV-infected cultures of CD16-depleted PBMCs from EBV-seropositive donors P1 and P7 and the EBV-seronegative donor N1 were harvested 7, 14, or 21 days after infection with B95.8 strain EBV, and the cells stained with FITC-conjugated MAb against CD19 and PE-conjugated MAb against CD23 were analyzed by flow cytometry. Cultures maintained in the presence of CSA (to suppress any T-cell response) were harvested at 21 days. Numbers in the upper right quadrant of the FACS profiles refer to the percentage of CD19+ CD23+ B cells in the culture.

EBV epitope-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell numbers in regressing cultures.

The 12 EBV-seropositive donors used in this study had previously been characterized for their prevailing levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell memory to defined EBV latent cycle epitopes (22, 23). Tables 1 and 2 identify those epitopes, their coordinates within the relevant latent antigen, their HLA restricting allele (where known), and the donors with detectable epitope-specific memory. The four seronegative donors used as controls had no detectable memory to any appropriate epitope.

TABLE 1.

CD4+ T-cell epitope peptides and responding donors

| EBV protein | Epitope coordinates | Acronym | HLA restrictiona | Responding donors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBNA1 | 71-85 | RRP | ND | 1 |

| 403-417 | RPF | ND | 2, 5, 6, 7 | |

| 455-469 | DGG | ND | 8 | |

| 475-489 | NPK | DR11 | 1 | |

| 485-499 | LRA | ND | 2, 3, 5, 7, 12 | |

| 509-528 | VYG | ND | 1, 3, 4, 7, 12 | |

| 515-528 | TSL | DR1, DR103 | 3, 12 | |

| 529-543 | PQC | DR14 | 7, 10, 11, 12 | |

| 563-577 | MVF | DR5 | 4 | |

| EBNA2 | 11-30 | LRA | DR17 | 6, 7, 9, 10 |

| 131-150 | MRM | ND | 5, 8 | |

| 206-225 | LPP | ND | 1, 3 | |

| 276-295 | PRS | DR52 DQ7 | 3, 4, 8, 9, 11, 12 | |

| EBNA3A | 364-385 | GPW | DR1 | 2, 7, 12 |

| 649-668 | QVA | ND | 1 | |

| 780-799 | EDL | DR15 | 2 | |

| EBNA3C | 66-85 | NRG | ND | 3, 7, 10 |

| 386-405 | SDD | DQ5 | 1, 4, 6, 11, 12 | |

| 401-420 | QQR | ND | 3, 7 | |

| 626-645 | PPV | ND | 1, 3, 7 | |

| 649-658 | PQC | ND | 8 | |

| 961-980 | AQE | ND | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 | |

| LMP2 | 149-163 | STV | ND | 5, 7 |

| 169-182 | SSY | ND | 5, 8 | |

| 224-243 | VLV | ND | 7, 8, 12 |

ND, not determined.

TABLE 2.

CD8+ T-cell epitope peptides and responding donors

| EBV protein | Epitope coordinates | Acronym | HLA restriction | Responding donors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBNA1 | 72-80 | RPQ | B7 | 2, 10 |

| 407-417 | HPV | B35.01 | 2 | |

| EBNA3A | 95-104 | RRFP | B27.02/05 | 1, 3, 10, 12 |

| 158-166 | QAK | B8 | 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 | |

| 325-333 | FLR | B8 | 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 | |

| 378-386 | KRPP | B27.05 | 1, 10, 12 | |

| 379-387 | RPP | B7 | 5 | |

| 458-466 | YPL | B35.01 | 2, 3, 10 | |

| 596-604 | SVR | A2.01 | 7, 9 | |

| 603-611 | RLR | A3 | 1 | |

| EBNA3B | 149-157 | HRCQ | B27 | 1, 10 |

| 217-225 | TYS | A24 | 3 | |

| 244-254 | RRAR | B27.02 | 3 | |

| 279-287 | VSF | B57 | 4 | |

| 399-408 | AVF | A11 | 2, 7 | |

| 416-424 | IVT | A11 | 2 | |

| 488-496 | AVL | B35.01 | 3 | |

| EBNA3C | 163-171 | EGG | B44 | 7, 8, 9 |

| 258-266 | RRIY | B27.02/05 | 1, 3, 10, 12 | |

| 281-290 | EEN | B44 | 8, 9 | |

| 335-343 | KEH | B44 | 7, 8, 9 | |

| 343-351 | FRKA | B27.05 | 1 | |

| 881-891 | QPR | B7 | 2 | |

| LMP2 | 329-227 | LLW | A2.01 | 7, 8, 9, 10 |

| 340-350 | SSC | A11 | 7 | |

| 356-364 | FLY | A2.01 | 7, 8, 10, 12 | |

| 419-427 | TYG | A24 | 3 | |

| 426-434 | CLG | A2.01 | 7, 8, 9, 10, 12 |

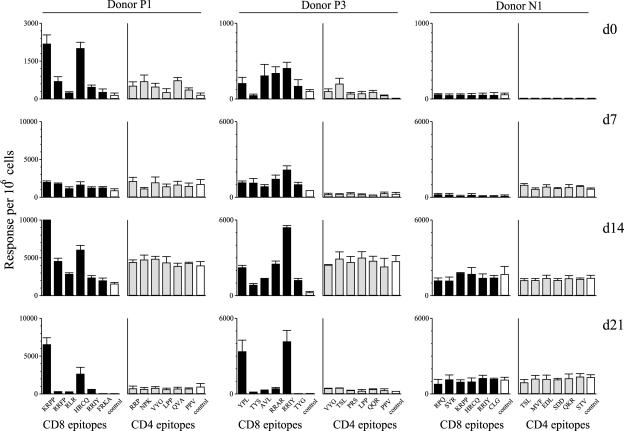

In the following experiments, EBV-infected PBMC cultures from the above donors were harvested at 7, 14, and 21 days postinfection, one-half of the harvested cells were depleted of CD4+ T cells and the other half of CD8+ T cells, and then the two depleted populations were screened for reactivity to the appropriate CD8 and CD4 epitope peptides in ELISpot assays. Figure 2 shows results for two seropositive donors, P1 and P3, and for the seronegative donor N1. Donor P1's principal CD8+ T-cell reactivities in ex vivo PBMC assays were against two B27.05-restricted epitopes, KRPP from EBNA3A and HRCQ from EBNA3B; both reactivities were significantly expanded by day 14 postinfection (just before the disappearance of CD19+ CD23+ cells; see Fig. 1C) and were still detectable at day 21. Likewise, three of donor P3's principal CD8 reactivities ex vivo (to the B35-restricted YPL epitope in EBNA3A and to the B27.02-restricted RRAR and RRIY epitopes in EBNA3B and -3C, respectively) were also expanded coincident with the occurrence of regression. However, for both donors there was no significant expansion of T cells against any of the six CD4+ T-cell epitopes recognized by ex vivo PBMCs. Note that, as a control, the seronegative donor N1 was tested against six CD8 and six CD4 epitopes appropriate to that donor's HLA type and no specific responses were detected either ex vivo or at any time in culture. With all three donors, however, there was an element of nonspecific T-cell activation in culture, apparent in ELISpot assays as background levels of spontaneous IFN-γ release and usually maximal by day 14. From data of the kind shown in Fig. 2, we calculated the increase in epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell numbers over the first 14 days of culture. For all 12 seropositive donors analyzed, the dominant CD8 epitope response regularly showed an amplification of 5- to 25-fold from that present in the ex vivo PBMC population. However, there was never any significant amplification of latent epitope-specific CD4+ T-cell memory in the same cultures.

FIG. 2.

Enumeration of CD8 and CD4 epitope-specificities in EBV-infected PBMC cultures. Data are shown for EBV-seropositive donors P1 and P3 and for the EBV-seronegative donor N1. Ex vivo PBMC preparations (day 0) and cells harvested from cultures 7, 14, and 21 days post-EBV infection were divided into two aliquots, one of which was depleted of CD4+ T cells before testing in ELISpot assays on CD8 epitopes appropriate to the donor, the other of which was depleted of CD8+ T cells before testing on appropriate CD4 epitopes. Results are expressed in histograms as the mean number (± standard error) of spot-forming cells per 106 cells in the test population from four replicate wells in each case. Assays on CD8 epitopes are shown by black bars, assays on CD4 epitopes by grey bars, and assays in the absence of peptide by open bars; irrelevant epitope peptides gave values similar to that of the no-peptide control. The HLA types of the donors were: donor P1, HLA-A3; B15, B27.05; DR11, DR13, DR52; DQ6, DQ7; donor P3, HLA-A1, A24; B27.02, B35; DR11, DR13, DR52, DQ6, DQ7; donor N1, HLA-A2; B7, B27.05; DR103, DR15, DR51; DQ6, DQ7. The identity of the peptides relevant for each particular set of HLA alleles are shown as acronyms as in Tables 1 and 2.

Regression in CD4+ T-cell-depleted PBMC cultures.

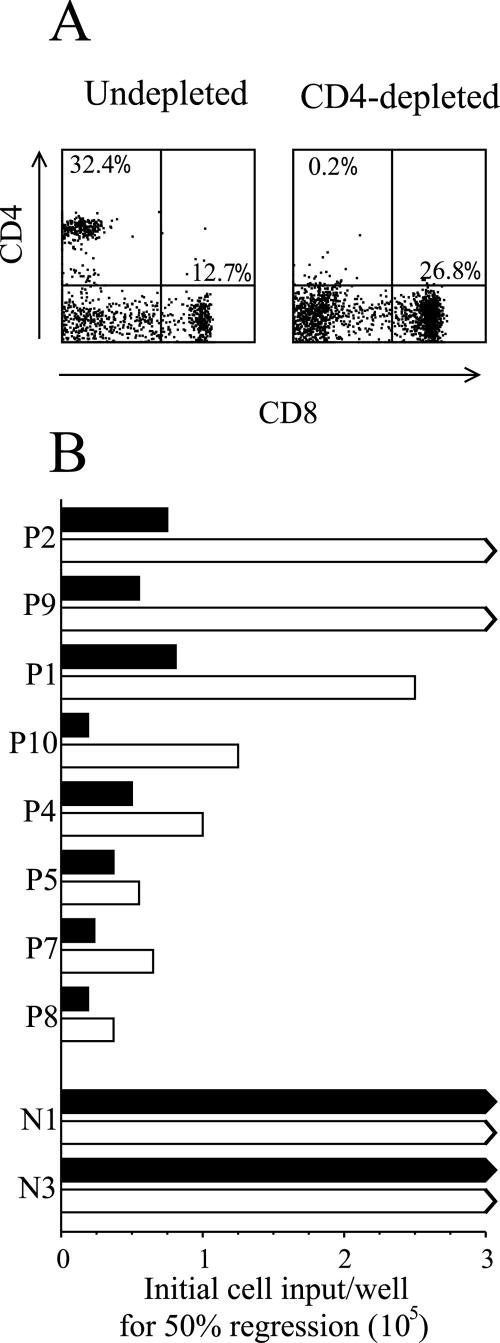

In light of the above results, we carried out a series of assays comparing the strength of regression shown by PBMCs with or without CD4+ T-cell depletion ex vivo. Figure 3A illustrates a typical depletion where the percentage of CD4+ T cells in the ex vivo PBMC population was reduced from 32.4% to 0.2%. Throughout these experiments such depletions routinely reduced the CD4+ T-cell fraction to frequencies below 0.5%. As shown in Fig. 3B, we always detected a weakening of regression following CD4+ T-cell depletion. This ranges from a slight effect in EBV-seropositive individuals, such as P8, with the strongest regression in unfractionated PBMC cultures, to a progressively more marked effect in donors, such as P10 and P1, and to a complete loss of detectable regression in two donors, P2 and P9. These individual differences were also reflected at days 7, 14, and 21 postinfection using CD19, CD23 costaining to track the fate of the EBV-infected B-cell population (data not shown). In the same experiment the seronegative control donors N1 and N3 showed successful B-cell outgrowth from both unfractionated and CD4-depleted PBMC cultures.

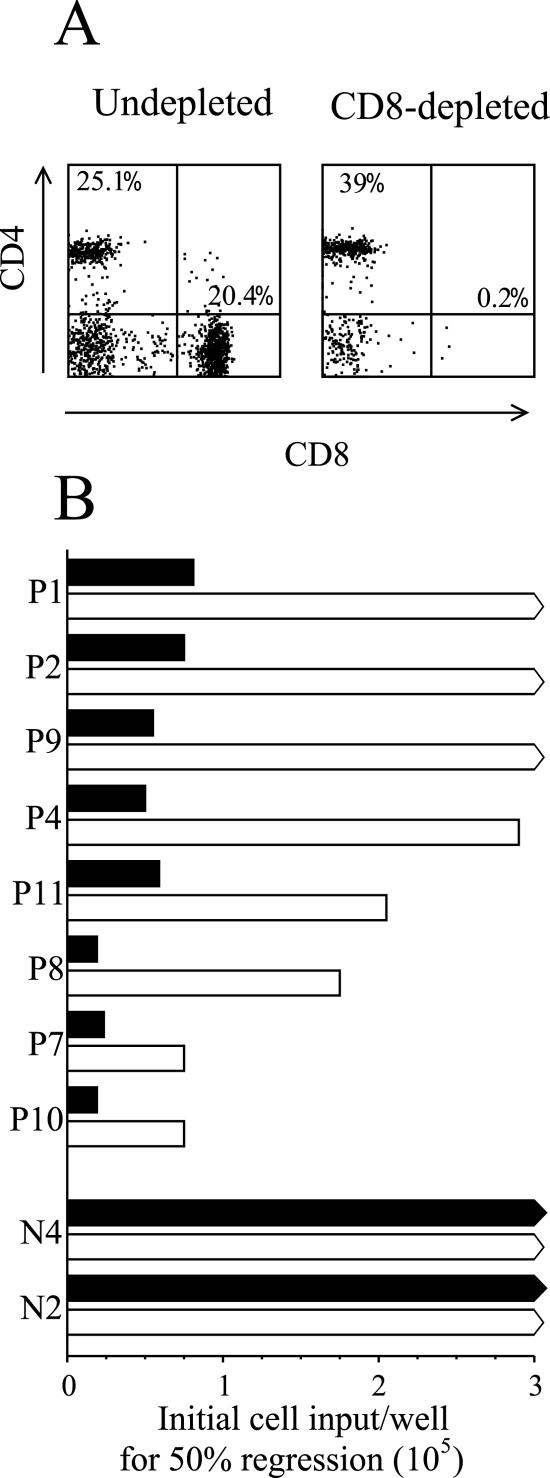

FIG. 3.

Regression in CD4+ T-cell depleted cultures. (A) PBMC from the EBV seropositive donor P1 were either undepleted or depleted of CD4+ T cells using magnetic beads and analyzed for purity by dual staining with FITC-conjugated MAb against CD4 and PE-conjugated MAb against CD8. Numbers refer to the percentage of CD4+CD8− cells (upper left quadrant) and of CD4−CD8+ cells (lower right quadrant) in the two populations. (B) Undepleted (filled bars) and CD4-depleted (open bars) PBMC from EBV seropositive donors (P2 to P8) and EBV seronegative donors (N1, N3) were tested in regression assays and the strength of response expressed as in Fig. 1A.

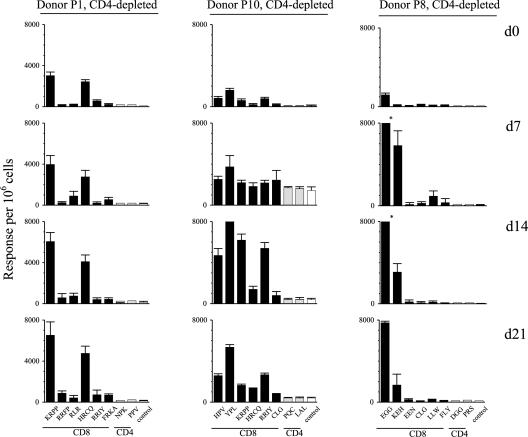

Figure 4 shows the corresponding ELISpot data for three representative donors, P1, P10, and P8, whose CD4-depleted cultures still regressed. We again found evidence that this was associated with an EBV epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell response. For donor P1, the response involves the same epitope reactivities as seen in that donor's PBMC cultures in Fig. 2, KRPP and HRCQ. However, it was significant that the degree of expansion up to day 14 was only about twofold in the absence of CD4+ T cells, whereas it had exceeded fivefold in the corresponding PBMC cultures. For another donor, P10, the CD4-depleted cultures showed a fivefold expansion of CD8+ T-cell memory to four dominant epitopes (two B35-restricted epitopes, HPV and YPL, from EBNA1 and EBNA3A, respectively, and two B27.05-restricted epitopes, KRPP and RRIY, from EBNA3A and EBNA3C, respectively). This compared with a 10- to 20-fold expansion of those responses in corresponding PBMC cultures from this donor (data not shown). For the third donor, P8, whose strength of regression was least affected by CD4 depletion (see Fig. 3), there was a rapid 25-fold expansion of CD8+ T-cell memory to two B44-restricted epitopes, EGG and KEH, from EBNA3C, in CD4-depleted cultures; this was almost equivalent to the expansions seen in unfractionated PBMC cultures from this donor (data not shown). These differences between individuals could not be explained by different efficiencies of CD4+ T-cell depletion, since contamination from residual CD4+ T cells consistently remained very low (usually <1%) throughout the culture period. In light of these results, we sought to ask whether the effects of CD4+ T-cell depletion could be overcome by supplying an exogenous source of IL-2 into the EBV-infected cultures. For those donors where CD4 depletion had either impaired or abrogated the control of EBV-infected B-cell outgrowth, rIL-2 supplementation of CD4-depleted cultures restored the efficiency of regression back to the values seen in undepleted PBMC cultures (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Enumeration of CD8 and CD4 epitope-specificities in EBV-infected cultures of CD4-depleted PBMCs. Data are shown for EBV-seropositive donors P1, P10, and P8. Ex vivo CD4-depleted PBMCs (day 0) and cells harvested from cultures of these same cells 7, 14, and 21 days post-EBV infection, were tested in ELISpot assays against the full panel of CD8 epitope peptides relevant to each donor plus the two CD4 epitopes against which the donor had the strongest CD4+ T-cell memory. Results are expressed as in Fig. 2. The HLA types of the donors were: donor P1, as in Fig. 2; donor P10, HLA-A2, A24; B27.05, B35; DR4, DR53; DQ8; donor P8, HLA-A2, A32; B44; DR7, DR15, DR51, DR53; DQ2, DQ6. The identity of the peptides are shown as acronyms as in Tables 1 and 2.

Regression in CD8+ T-cell-depleted PBMC cultures.

We then carried out a corresponding series of experiments looking at the effect of CD8+ T-cell depletion on regression. Depletion always reduced the fraction of CD8+ T cells in ex vivo PBMC populations down to below 0.5%; one such result (for donor P7) is illustrated in Fig. 5A. Figure 5B shows the results of the corresponding regression assays. As anticipated from the above findings, CD8 depletion significantly impaired regression, and the effect was generally more marked than that of CD4 depletion. Three of the eight seropositive donors tested failed to regress in CD8-depleted cultures, and regression was significantly weakened in the remaining donors. Also, where regression still occurred, it was markedly delayed and often required a full 5 weeks before the status of the cultures could be unequivocally determined whether by microscopic observation or by CD19, CD23 staining.

FIG. 5.

Regression of CD8+ T-cell depleted cultures. (A) PBMC from the EBV-seropositive donor P7 were either undepleted or depleted of CD8+ T cells using magnetic beads and analyzed for purity by staining with FITC-conjugated MAb against CD4 and PE conjugated MAb against CD8. Numbers refer to the percentage of CD4+CD8- and CD4-CD8+ cells as in Fig. 3A. (B) Undepleted (filled bars) and CD8-depleted (open bars) PBMC from EBV seropositive donors (P1 to P10) and EBV seronegative donors (N4, N2) were tested in regression assays and the strength of regression expressed as in Fig. 1A.

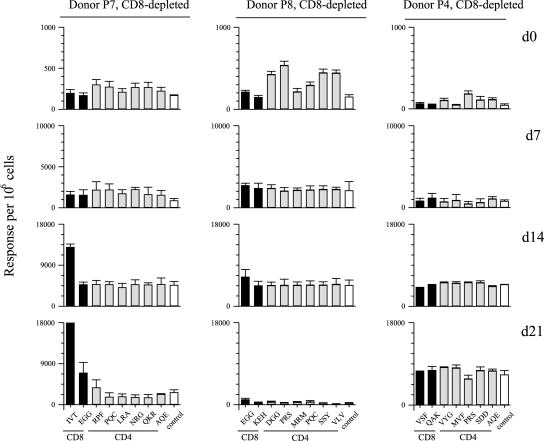

We then screened regressing cultures from selected donors for evidence of EBV epitope-specific reactivities in ELISpot assays. Figure 6 shows data from three such donors, P7, who still regressed well after CD8 depletion, P8, who showed intermediate regression, and P4, in whom regression was almost abrogated by CD8 depletion. Significantly, the cultures from all three donors showed no detectable expansion of CD4+ T-cell memory to defined EBV latent cycle epitopes, despite the fact that in each case such reactivities were clearly present in the CD8-depleted PBMCs screened by ELISpot ex vivo. Note that these day-0 assays also included, for each donor, peptides representing their two strongest CD8 epitope responses; no reactivities were detected, confirming the efficiency of CD8+ T-cell depletion from responder PBMCs. However, the occurrence of regression in the cultures from donor P7 and P8 was associated with the unexpected appearance of an epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell response. This was particularly observed for donor P7 using the A11-restricted IVT epitope from EBNA3B and also for donor P8 using the B44-restricted EGG epitope from EBNA3C; both represent the strongest CD8 epitope response detectable in ex vivo PBMCs from these donors (1,250 and 2,000 epitope/specific cells for 105 CD8+ T cells, respectively; data not shown). Knowing the level of CD8+ T-cell contamination in the starting population for donors P7 and P8 (0.2% and 0.1%, respectively), one can calculate that the relevant IVT- and EGG-specific CD8 populations were expanded by approximately 700-fold and 100-fold, respectively, in the regressing cultures. This no doubt contributed to the finding that in these regressing cultures CD8+ T-cell contamination had increased from the very low initial levels to 6% and 2% of total cells by day 14 postinfection (data not shown). However, in the third donor, P4, where regression was observed in some but not all cultures seeded at the highest concentration, CD8 contamination remained at 0.6%, and we found no evidence of an EBV epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell response. This raised the possibility that a CD4+ T-cell response might also contribute to regression, particularly in the absence of the usually dominant CD8+ response.

FIG. 6.

Enumeration of CD8 and CD4 epitope-specificities in EBV-infected cultures of CD8-depleted PBMCs. Data are shown for EBV-seropositive donors P7, P8, and P4. Ex vivo CD8-depleted PBMCs (day 0) and cells harvested from cultures of the same cells 7, 14, and 21 days post-EBV infection were tested in ELISpot assays against the full panel of CD4 epitope peptides relevant to each donor plus the two CD8 epitopes against which the donor had the strongest CD8+ T-cell memory. Results (with standard errors) are expressed as in Fig. 2; note that the small amplifications of EGG-responsive CD8+ T cells seen in donors P7 and P8 were observed in repeat experiments. The HLA types of the donors were: donor P7, A2, A11; B8, B44; DR13, DR17, DR52; DQ2, DQ6; donor P8, as in Fig. 4; donor P4, A1; B8, B57; DR7, DR17, DR52; DQ2, DQ9. The identity of the peptides are shown as acronyms as in Tables 1 and 2.

Analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell clones derived from regressing cultures.

In the final set of experiments involving EBV-seropositive donors P7 and P4, we harvested day 14 EBV-infected cultures of CD4-depleted PBMCs and of CD8-depleted PBMCs and seeded these at limiting dilutions of 0.3 and 3 cells/well onto γ-irradiated feeder cells in IL-2-conditioned medium to establish T-cell clones. All growing microcultures were first stained to confirm CD4+ or CD8+ status and then were screened for recognition of the autologous LCL and of autologous CD40-activated B lymphoblasts, both of which had been prepared as targets growing in FCS-supplemented medium and in HuS-supplemented medium. This allowed the identification of clones specifically reactive to antigens expressed on the LCL and eliminated clones specific to FCS components.

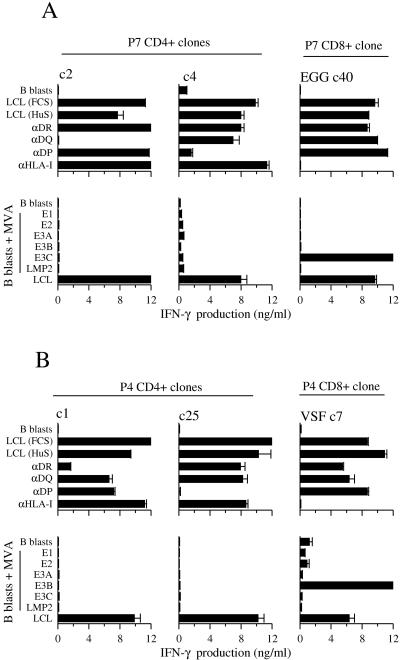

Cloning from CD4-depleted cultures yielded multiple CD8+ T cells which recognized the autologous LCL and which mapped to the same immunodominant epitopes as recognized by the donor's CD8+ T-cell memory in ex vivo ELISpot assays. Figure 7 (right-hand columns) shows IFN-γ release data for a CD8+ T-cell clone from donor P7 reactive to the B44-restricted EGG epitope in EBNA3C and for a CD8+ T-cell clone from donor P4 reactive to the B57-restricted VSF epitope in EBNA3B. These clones clearly recognized the autologous LCL (whether in HuS or FCS) but not autologous B lymphoblasts, and LCL recognition was blocked by an HLA class I MAb but not by any of the HLA class II allele-specific MAbs. Furthermore, when tested on B lymphoblasts expressing one of a panel of invariant chain-tagged EBV latent proteins from recombinant MVA vectors, the clones recognized their specific antigen, EBNA3C and EBNA3B, respectively.

FIG. 7.

HLA restriction and EBV antigen mapping assays on CD4+ T-cell clones isolated from EBV-infected cultures of CD8-depleted PBMCs (A) from EBV-seropositive donor P7 (c2, c4) and (B) from EBV-seropositive donor P4 (c1, c25). Included in the analysis as positive controls are one CD8+ T-cell clone from each donor isolated from EBV-infected cultures of CD4-depleted PBMCs; donor P7 c40 is specific for the B44-restricted EGG epitope in EBNA3C, and donor P4 c7 is specific from the B57-restricted VSF epitope in EBNA3B. All clones were tested in MAb blocking assays against the autologous LCL grown either in FCS- or HuS-supplemented medium, and against the autologous LCL grown in FCS-supplemented medium assayed in the presence of MAbs specific for HLA-DR, HLA-DQ, HLA-DP, or HLA class I alleles; CD40-L-activated B lymphoblasts serve as negative control targets. All clones were also tested in EBV antigen mapping assays on autologous B lymphoblasts either uninfected or infected with MVA vectors expressing invariant chain-targeted forms of EBV latent proteins EBNA1 (E1), EBNA2 (E2), EBNA3A (E3A), EBNA3B (E3B), EBNA3C (E3C), or LMP2; the autologous LCL served as a positive control target. In all assays, T-cell recognition was monitored by IFN-γ release quantitated by ELISA.

Cloning from CD8-depleted cultures of the above two donors yielded a small number of immunodominant epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell clones (particularly from donor P7) but also multiple CD4+ T-cell clones. Interestingly, some 16/30 CD4+ clones from donor P7 and 8/31 CD4+ clones from donor P4 showed specific recognition of the autologous LCL (whether in HuS- or in FCS-supplemented medium) and not of autologous B lymphoblasts. The data for two LCL-reactive clones from each donor are illustrated in Fig. 7A and B (left-hand and central columns). The MAb-blocking assays clearly show that donor P7 clones c2 and c4 are restricted through HLA-DQ and HLA-DP alleles, respectively, and donor P4 clones c1 and c25 through HLA-DR and HLA-DQ, respectively. Importantly, none of the 24 LCL-reactive CD4+ T-cell clones derived from these two donors recognized any of the EBV latent cycle epitopes against which these donors displayed CD4+ T-cell memory in ex vivo assays, nor could they be mapped to any other defined EBV latent cycle antigen or epitope. Thus, as exemplified in Fig. 7, there was never any recognition of B lymphoblasts expressing one of a panel of six invariant chain-targeted EBV antigens from MVA vectors. In addition, because relevant viral vectors were not available for the two remaining EBV latent proteins, EBNA-LP and LMP1, we screened these same clones against pools of peptides covering the entire sequence of these two proteins and again never detected any IFN-γ release (data not shown). These negative screening results are highly significant, because in other work the relevant MVA recombinants and peptide pools are strongly recognized by CD4+ T-cell clones specific for defined EBV latent cycle epitopes (45 and Taylor et al., manuscript in preparation). We also explored the possibility that these effectors were specific for EBV lytic cycle antigens, since a small fraction of cells in most LCLs are lytically infected. However, this was clearly not the case, since they also recognized LCLs of the relevant HLA class II type that were transformed with a recombinant EBV strain lacking the immediate-early transactivator BZLF1 (9) and were therefore incapable of lytic cycle entry (data not shown). We infer that these CD4+ T-cell effectors are operationally LCL-specific but do not map to any currently known EBV-coded protein.

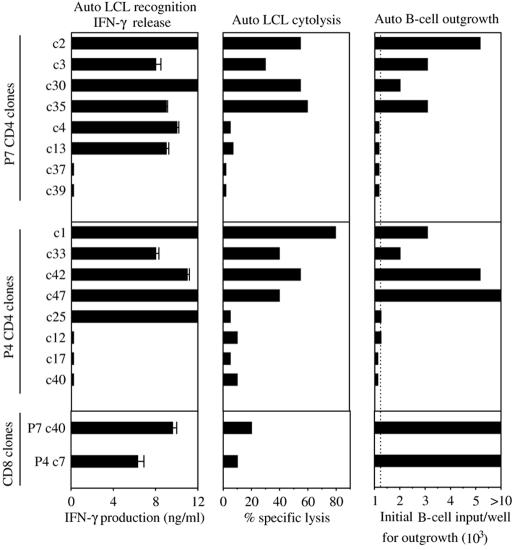

We then asked whether these novel CD4+ T-cell reactivities were potential effectors of regression, firstly by screening for cytotoxic activity in short-term 51chromium release assays and secondly by screening for their ability to prevent the outgrowth of autologous EBV-infected B cells in longer-term cocultures. These experiments included EBV latent epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell clones derived from the same donors as positive controls and non-LCL-reactive CD4+ T-cell clones from the same donors as negative controls. Figure 8 illustrates the results obtained. Of six CD4+ clones from donor P7 that were LCL-specific in IFN-γ assays (left-hand column), four were also cytotoxic to the autologous LCL in 51chromium release assays (central column), and the same four were capable of inhibiting B-cell outgrowth (right-hand column). Likewise, of five CD4+ clones from donor P4 that were LCL specific in IFN-γ release assays, four showed cytotoxic activity, and the same four significantly impaired B-cell outgrowth. For both donors, those CD4 clones included as negative controls because they showed no IFN-γ response to the LCL also showed no activity either in the cytotoxicity or in the B-cell outgrowth assays. These results are representative of a pattern seen throughout these experiments; all 11 LCL-specific cytotoxic clones tested on freshly infected B cells had a significant effect on outgrowth, whereas all 14 noncytotoxic clones (whether or not LCL-reactive in IFN-γ assays) never affected outgrowth. Figure 8 also shows results from the two latent epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell clones already described in Fig. 7. These cells show good LCL recognition by IFN-γ release but, as often seen with such CD8+ T-cell clones (21), mediate lower levels of LCL killing in short-term 51chromium release assays. However, they consistently inhibit B-cell outgrowth at least as effectively as the best CD4+ T-cell clones tested.

FIG. 8.

Functional analysis of LCL-specific CD4+ T-cell clones derived from EBV-infected cultures of CD8-depleted PBMCs of EBV-seropositive donors P7 (c2 to c13) and P4 (c1 to c25). Clones were tested (i) in ELISA assays of IFN-γ produced in response to autologous LCL stimulation as in Fig. 7, (ii) in 5-h chromium release assays against the autologous LCL target, the data being expressed as percentage specific lysis at an effector target ratio of 5:1, and (iii) in cocultivation assays for inhibition of the outgrowth of autologous B cells seeded 4 days post-EBV infection, the data being expressed as the minimum number of B cells required for successful outgrowth; the dotted line indicates the efficiency of outgrowth of EBV-infected B cells seeded alone. Included in the same experiments were CD4+ T-cell clones from the same donors that had failed to show LCL recognition in the initial IFN-γ screening assays (P7, c37 and c39; P4, c12-c40), and one latent epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell clone per donor (P7, c40; and P4, c7) as in Fig. 7.

DISCUSSION

Although the regression assay as a means of quantitating EBV-specific memory T-cell responses has been superseded by a variety of single-cell techniques (1, 6, 44), the phenomenon of regression remains interesting since it reflects the combined impact of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell memory upon virus-induced B-cell transformation. Thus, it recapitulates an immunological control which is likely to be occurring at sites of de novo B-cell infection in healthy virus carriers in vivo (2) and which, when impaired, renders immunocompromised patients at high risk of EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disease (11, 32, 37). To reexamine the cell-mediated responses underlying regression, we adopted the recent approach of Nikiforow and colleagues; PBMCs were depleted of either CD16+ NK cells, CD4+ T cells, or CD8+ T cells and then exposed to EBV, and the progress of virus-induced B-cell transformation was monitored weekly by CD19, CD23 costaining (33). In addition, however, we monitored the same cultures for expansions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells recognizing epitope peptides already known to be the dominant targets of EBV latent antigen-specific T-cell memory in the blood of donors being tested.

Our results confirm that regression is entirely T cell dependent with no obvious role for CD16+ NK cells but, in contrast to the above report (33), indicate that virus-specific CD8+, rather than CD4+, T cells are the principal effector population. Thus, regression in unfractionated PBMC cultures is coincident with the in vitro activation and expansion of epitope-specific CD8+ (but not the corresponding CD4+) memory cells. While regression is often impaired in CD4-depleted PBMC cultures, this impairment directly correlates with a reduced expansion of the relevant epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell response. Indeed, the CD4+ T-cell dependence of regression could be entirely overcome by rIL-2 supplementation of CD4-depleted cultures. We infer that at least one important contribution of CD4+ T cells in the control of B-cell outgrowth in vitro is to provide cytokines, in particular IL-2, for CD8+ T-cell expansion. The identity of the CD4+ T cells mediating this helper function remains to be determined, but memory cells specific for virus structural proteins within B95.8 virion preparations are likely to be involved; such cells clearly exist in seropositive donors, as shown originally by T-cell proliferation assays and CD4+ T-cell cloning (48) and more recently by IFN-γ release (1).

In view of the above results, it was surprising to find that CD8+ T-cell depletion itself did not entirely abrogate regression. However, the donors whose CD8-depleted cultures still regressed were those with the strongest responses in the unfractionated PBMC assays. Indeed, for several such donors analyzed (here exemplified by P7 and P8) regression was accompanied by the appearance of a contaminating CD8 effector population which had expanded up to 750-fold from the very low numbers that must have been present within the initial culture population. An interesting feature of this regression response in CD8-depleted cultures (data not shown) was that, unlike the situation in CD4-depleted cultures, supplementation with rIL-2 did not amplify the effect. We infer that, in the presence of a numerically dominant CD4+ T-cell population, the cytokine requirements for CD8 effector cell expansion are fully satisfied and that additional supplementation is redundant.

The identification of latent epitope-specific CD8+ T cells as the principal effectors of regression is entirely consistent with much of the early literature. Thus, the first regression assays conducted with reconstructed populations of EBV-infected T-depleted PBMCs as targets and positively selected CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell subpopulations as responders identified CD8+ T cells as the major effectors (7). Furthermore, T cells harvested from regressing PBMC cultures were dominated by CD8+ T-cell effectors that not only killed established LCL targets in a HLA class I-restricted manner (28, 50) but also killed EBV-infected B cells early in the process of transformation (29), just as would be required of the T cells mediating regression. However, our data are partly at odds with the more recent work of Nikiforow and colleagues (33), who found that CD8 depletion had no effect on regression, whereas CD4 depletion appeared to completely abrogate the response. It seems unlikely that differences in methods of virus preparation or in precise culture conditions can account for the apparent discrepancies between the two reports, since the basic parameters of regression in PBMC cultures are essentially identical in both laboratories (33, 27). We agree that depleting CD4+ T cells will prevent detectable regression in a significant number (up to 50%) of donors. In many other cases, however, we find that regression still occurs but is less efficient because the CD8+ T-cell expansion is reduced in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help; the residual response may therefore go undetected if the test cultures have not been seeded at a sufficiently high cell density or if the screening is not continued for the full 4-week period of culture. As to the effects of CD8 depletion, we again agree with Nikiforow and colleagues that regression can occur in such circumstances. However, in our hands, this almost always involves individuals with potent CD8+ T-cell immune responses in unfractionated PBMC cultures and is often associated with an unexpectedly vigorous expansion of a contaminating EBV-specific CD8+ T-cell population. For some donors, such as P7 (Fig. 5, 6), this occurred even when the initial level of CD8+ contamination was <0.2%, a value which is significantly lower than that quoted for CD8+ T-cell-depleted preparations used in the earlier work (33). It is therefore possible that at least some examples of CD8-independent regression in that earlier study came, as in our experiments, from CD8 contamination.

In a subsequent study, however, Nikiforow and colleagues clearly showed that EBV latent epitope-specific CD4+ T-cell clones, produced by specific antigen stimulation in vitro rather than derived from regressing cultures, could block the outgrowth of autologous EBV-infected B cells (34). Indeed, we have independently confirmed this result with CD4+ T-cell clones to some, but not all, latent cycle epitopes (23). A reasonable assumption, therefore, was that such CD4 specificities were also efficiently reactivated in regressing cultures and were responsible for blocking B-cell outgrowth in that situation also. The present data show that this is not the case. Expansions of EBV latent epitope-specific CD4+ T cells were never detectable in regressing cultures either by sensitive ELISpot assays or by CD4+ T-cell cloning. We infer that the poor reactivation of these CD4+ T cells reflects both the smaller size of EBV-specific CD4 memory populations in blood relative to CD8+ T-cell memory (22) and the fact that, as our recent experiments show (23), most CD4 epitopes from latent cycle proteins are relatively poorly displayed on EBV-transformed B cells. While ruling out latent antigen-specific CD4+ T cells as effectors of regression, our experiments do not exclude the possibility that virus structural antigen-specific CD4+ T cells, following their activation and transient expansion in experimentally infected PBMC cultures (1, 48), may contribute in ways other than simply promoting CD8+ T-cell expansion; for example, cytokines released from such cells may underlie the previously reported capacity of adult donor T cells to delay the early events of B-cell transformation (46, 47). The potential involvement of such virion-activated CD4+ T cells in the regression phenomenon will be easier to examine once their precise viral antigen/epitope specificities have been determined. However, such virion-activated responses are clearly not necessary for effective T-cell control of LCL outgrowth, since the phenomenon of regression can be faithfully reproduced using limiting dilution seedings of the already established autologous LCL rather than freshly infected B cells as the in vitro challenge to immune donor PBMCs (39).

Unexpectedly, however, our experiments revealed the presence of another potential CD4+ effector cell in regressing cultures that was distinct both from previously defined latent antigen specificities and from virus structural antigen specificities. These cells showed typical HLA class II allele-restricted recognition of LCL targets and no recognition of EBV-negative B lymphoblasts, yet the could not be mapped to any known EBV latent or lytic antigen. The targets recognized by these LCL-specific effectors remain to be determined, as does the relationship between the generation of such a response and the donor's EBV-immune status. Both EBV-seropositive donors tested in our experiments yielded LCL-specific CD4+ T-cell clones, whereas parallel cloning from one seronegative donor (data not shown) only yielded FCS-specific clones. It is therefore too early to say how these effectors relate to CD4+ T-cell preparations with LCL reactivity already described in the literature, mostly generated by LCL stimulation and derived either from cord blood (26, 53), EBV seronegative donors (25, 41), or EBV-seropositive donors (24, 14, 19, 43, 52). All these preparations killed the autologous LCL and, where tested at the clonal level (24, 25, 19, 43), also showed HLA class II-restricted recognition of allogeneic LCLs but not mitogen-activated lymphoblasts. Though frequently described as EBV-specific, these effectors were never tested for reactivity against EBV antigens or epitopes in the ways described in the present report and may indeed be functionally similar to those described here. The LCL-specific CD4+ population within regressing cultures appeared to be functionally heterogeneous; thus, many derived CD4+ clones were identified as LCL-specific by the criterion of IFN-γ release, but of these, only about half showed cytotoxic activity. Interestingly, these were also the only clones that could prevent B-cell outgrowth, in some cases just as efficiently as latent epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell clones. This not only reinforces their credentials as potential CD4+ effectors of regression, whose activity may best be seen in the absence of the dominant CD8 response, but also strongly suggests that CD4+ T-cell-mediated control of EBV-transformed B-cell growth requires cell killing and is not mediated by cytokine release.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amyes, E., C. Hatton, D. Montamat-Sicotte, N. H. Gudgeon, A. B. Rickinson, A. J. McMichael, and M. F. Callan. 2003. Characterization of the CD4+ T cell response to Epstein-Barr virus during primary and persistent infection. J. Exp. Med. 198:903-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock, G. J., D. Hochberg, and A. D. Thorley-Lawson. 2000. The expression pattern of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes in vivo is dependent upon the differentiation stage of the infected B cell. Immunity 13:497-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau, J., P. de Paoli, A. Valle, E. Garcia, and F. Rousset. 1991. Long-term human B cell lines dependent on interleukin-4 and antibody to CD40. Science 251:70-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird, A. G., S. M. McLachlan, and S. Britton. 1981. Cyclosporin A promotes spontaneous outgrowth in vitro of Epstein-Barr virus-induced B-cell lines. Nature 289:300-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blake, N., S. Lee, I. Redchenko, W. Thomas, N. Steven, A. Leese, P. Steigerwald-Mullen, M. G. Kurilla, L. Frappier, and A. Rickinson. 1997. Human CD8+ T cell responses to EBV EBNA1: HLA class I presentation of the (Gly-Ala)-containing protein requires exogenous processing. Immunity 7:791-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callan, M. F., L. Tan, N. Annels, G. S. Ogg, J. D. Wilson, C. A. O'Callaghan, N. Steven, A. J. McMichael, and A. B. Rickinson. 1998. Direct visualization of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during the primary immune response to Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 187:1395-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford, D. H., V. Iliescu, A. J. Edwards, and P. C. Beverley. 1983. Characterisation of Epstein-Barr virus-specific memory T cells from the peripheral blood of seropositive individuals. Br. J. Cancer 47:681-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delecluse, H. J., E. Kremmer, J. P. Rouault, C. Cour, G. Bornkamm, and F. Berger. 1995. The expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent proteins is related to the pathological features of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Am. J. Pathol. 146:1113-1120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feederle, R., M. Kost, M. Baumann, A. Janz, E. Drouet, W. Hammerschmidt, and H. J. Delecluse. 2000. The Epstein-Barr virus lytic program is controlled by the co-operative functions of two transactivators. EMBO J. 19:3080-3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu, Z., and M. Cannon. 2000. Functional analysis of the CD4+ T-cell response to Epstein-Barr virus: T-cell-mediated activation of resting B cells and induction of viral BZLF1 expression. J. Virol. 74:6675-6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaidano, G., A. Carbone, and R. Dalla-Favera. 1998. Pathogenesis of AIDS-related lymphomas—molecular and histogenetic heterogeneity. Am. J. Pathol. 152:623-630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton-Dutoit, S. J., D. Rea, M. Raphael, K. Sandvej, H. J. Delecluse, C. Gisselbrecht, L. Marelle, H. J. van Krieken, and G. Pallesen. 1993. Epstein-Barr virus-latent gene expression and tumor cell phenotype in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Correlation of lymphoma phenotype with three distinct patterns of viral latency. Am. J. Pathol. 143:1072-1085. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heslop, H. E., and C. M. Rooney. 1997. Adoptive cellular immunotherapy for EBV lymphoproliferative disease. Immun. Rev. 157:217-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honda, S., T. Tagasaki, K. Okuno, M. Yasutomi, and I. Kurane. 1998. Establishment and characterization of Epstein-Barr virus-specific human CD4+ T lymphocytes clones. Acta Virol. 42:307-313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanna, R., S. R. Burrows, M. G. Kurilla, C. A. Jacob, I. S. Misko, T. B. Sculley, E. Kieff, and D. J. Moss. 1992. Localization of Epstein-Barr virus cytotoxic T cell epitopes using recombinant vaccinia: implications for vaccine development. J. Exp. Med. 176:169-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanna, R., S. R. Burrows, P. M. Steigerwald-Mullen, S. A. Thomson, M. G. Kurilla, and D. J. Moss. 1995. Isolation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes from healthy seropositive individuals specific for peptide epitopes from Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1: implications for viral persistence and tumor surveillance. Virology 214:633-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khanna, R., S. R. Burrows, S. A. Thomson, D. J. Moss, P. Cresswell, L. M. Poulsen, and L. Cooper. 1997. Class I processing-defective Burkitt's lymphoma cells are recognized efficiently by CD4+ EBV-specific CTLs. J. Immunol. 158:3619-3625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna, R., and S. R. Burrows. 2000. Role of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in Epstein-Barr virus-associated diseases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:19-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khanokar, A., H. Yagita, and M. J. Cannon. 2001. Preferential utilization of the perforin/granzyme pathway for lysis of Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cells by virus-specific CD4+ T cells. Virology 287:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lalvani, A., R. Brooks, S. Hambleton, W. J. Britton, A. V. S. Hill, and A. J. McMichael. 1997. Rapid effector function in CD8+ memory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:859-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, S. P., R. J. Tierney, W. A. Thomas, J. M. Brooks, and A. B. Rickinson. 1997. Conserved CTL epitopes within EBV latent membrane protein 2: a potential target for CTL-based tumor therapy. J. Immunol. 158:3325-3334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leen, A., P. Meij, I. Redchenko, J. Middeldorp, E. Bloemena, A. B. Rickinson, and N. Blake. 2001. Differential immunogenicity of Epstein-Barr virus latent-cycle proteins for human CD4(+) T-helper 1 responses. J. Virol. 75:8649-8659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long, H. M., T. A. Haigh, N. H. Gudgeon, A. M. Leen, C. W. Tsang, J. Brooks, E. Landais, E. Houssaint, S. P. Lee, A. B. Rickinson, and G. S. Taylor. 2005. CD4+ T-cell responses to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent cycle antigens and the recognition of EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines J. Virol. 79:4896-4907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misko, I. S., J. H. Pope, R. Hutter, T. D. Soszynski, and R. G. Kane. 1984. HLA-DR-antigen-associated restriction of EBV-specific cytolytic T-cell colonies. Int. J. Cancer 33:239-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misko, I. S., T. B. Sculley, C. Schmidt, D. J. Moss, D., T. Soszynski, and K. Burman. 1991. Composite response of naive T cells to stimulation with the autologous lymphoblastoid cell line is mediated by CD4 cytotoxic T cell clones and includes an Epstein-Barr virus-specific component. Cell. Immun. 132:295-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moretta, A., P. Comoli, D. Montagna, A. Gasparoni, E. Percivalle, I. Carena, M. G. Revello, G. Gerna, G. Mingrat, F. Locatelli, G. Rondini, and R. Maccario. 1997. High frequency of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) lymphoblastoid cell line-reactive lymphocytes in cord blood: evaluation of cytolytic activity and IL-2 production. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 107:312-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moss, D. J., A. B. Rickinson, and J. H. Pope. 1978. Long-term T-cell-mediated immunity to Epstein-Barr virus in man. I. Complete regression of virus-induced transformation in cultures of seropositive donor leukocytes. Int. J. Cancer 22:662-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moss, D. J., L. E. Wallace, A. B. Rickinson, and M. A. Epstein. 1981. Cytotoxic T cell recognition of Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells. I. Specificity and HLA restriction of effector cells reactivated in vitro. Eur. J. Immunol. 11:686-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moss, D. J., A. B. Rickinson, L. E. Wallace, and M. A. Epstein. 1981. Sequential appearance of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear and lymphocyte-detected membrane antigens in B cell transformation. Nature 291:664-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munz, C., K. L. Bickham, M. Subklewe, M. L. Tsang, A. Chahroudi, M. G. Kurilla, D. Zhang, M. O'Donnell, and R. M. Steinman. 2000. Human CD4(+) T lymphocytes consistently respond to the latent Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA1. J. Exp. Med. 191:1649-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray, R. J., M. G. Kurilla, J. M. Brooks, W. A. Thomas, M. Rowe, E. Kieff, and A. B. Rickinson. 1992. Identification of target antigens for the human cytotoxic T cell response to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV): implications for the immune control of EBV-positive malignancies. J. Exp. Med. 176:157-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nalesnik, M. A. 1998. Clinical and pathological features of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD). Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 20:325-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikiforow, S., K. Bottomly, and G. Miller. 2001. CD4+ T-cell effectors inhibit Epstein-Barr virus-induced B-cell proliferation. J. Virol. 75:3740-3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikiforow, S., K. Bottomly, G. Miller, and C. Munz. 2003. Cytolytic CD4(+)-T-cell clones reactive to EBNA1 inhibit Epstein-Barr virus-induced B-cell proliferation. J. Virol. 77:12088-12104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Omiya, R., C. Buteau, H. Kobayashi, C. V. Paya, and E. Celis. 2002. Inhibition of EBV-induced lymphoproliferation by CD4(+) T cells specific for an MHC class II promiscuous epitope. J. Immunol. 169:2172-2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paludan, C., K. Bickham, S. Nikiforow, M. L. Tsang, K. Goodman, W. A. Hanekom, J. F. Fonteneau, S. Stevanovic, and C. Munz. 2002. Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1-specific CD4(+) Th1 cells kill Burkitt's lymphoma cells. J. Immunol. 169:1593-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paya, C. V., J. J. Fung, M. A. Nalesnik, E. Kieff, M. Green, G. Gores, T. M. Habermann, R. H. Wiesner, L. J. Swinnen, E. S. Woodle, and J. S. Bromberg. 1999. Epstein-Barr virus-induced, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Transplantation 68:1517-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rickinson, A. B., L. E. Wallace, and M. A. Epstein. 1980. HLA-restricted T-cell recognition of Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells. Nature 283:865-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rickinson, A. B., D. J. Moss, D. J. Allen, L. E. Wallace, M. Rowe, and M. A. Epstein. 1981. Reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus-specific cytotoxic T cells by in vitro stimulation with the autologous lymphoblastoid cell line. Int. J. Cancer 27:593-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rickinson, A. B., and D. J. Moss. 1997. Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:405-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savoldo, B., M. L. Cubbage, A. G. Durett, J. Goss, M. H. Huls, Z. Liu, L., Teresita, A. P. Gee, P. D. Ling, M. K. Brenner, H. E. Heslop, and C. M. Rooney. 2002. Generation of EBV-specific CD4+ cytotoxic T cells from virus naive individuals. J. Immunol. 168:909-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steigerwald-Mullen, P., M. G. Kurilla, and T. J. Braciale. 2000. Type 2 cytokines predominate in the human CD4(+) T-lymphocyte response to Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. J. Virol. 74:6748-6759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun, Q., R. L. Burton, and K. G. Lucas. 2001. Cytokine production and cytolytic mechanism of CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in ex vivo expanded therapeutic Epstein-Barr virus-specific T-cell cultures. Blood 99:3302-3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan, L. C., N. H. Gudgeon, N. E. Annels, P. Hansasuta, C. A. O'Callaghan, S. Rowland-Jones, A. J. McMichael, A. B. Rickinson, and M. F. Callan. 1999. A re-evaluation of the frequency of CD8+ T cells specific for EBV in healthy virus carriers. J. Immunol. 162:1827-1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor, G. S., T. A. Haigh, N. H. Gudgeon, R. J. Phelps, S. P. Lee, N. M. Steven, and A. B. Rickinson. 2004. Dual stimulation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific CD4+- and CD8+-T-cell responses by a chimeric antigen construct: potential therapeutic vaccine for EBV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Virol. 78:768-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thorley-Lawson, D. A., L. M. Chess, and J. L. Strominger. 1977. The suppression of in vitro Epstein-Barr virus infection-a new role for adult human T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 146:495-508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thorley-Lawson, D. A. 1981. The transformation of adult but not newborn human lymphocytes by Epstein-Barr virus and phytohemagglutinin is inhibited by interferon: the early suppression by T cells of Epstein-Barr virus infection is mediated by interferon. J. Immunol. 126:829-833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ulaeto, D., L. Wallace, A. Morgan, B. Morein, and A. B. Rickinson. 1988. In vitro T cell responses to a candidate Epstein-Barr virus vaccine: human CD4+ T cell clones specific for the major envelop glycoprotein gp340. Eur. J. Immunol. 18:1689-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voo, K. S., T. Fu, H. E. Heslop, M. K. Brenner, C. M. Rooney, and R. F. Wang. 2002. Identification of HLA-DP3-restricted peptides from EBNA1 recognized by CD4(+) T cells. Cancer Res. 62:7195-7199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallace, L. E., D. J. Moss, A. B. Rickinson, A. J. McMichael, and M. A. Epstein. 1981. Cytotoxic T cell recognition of Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells. II. Blocking studies with monoclonal antibodies to HLA determinants. 11:694-699. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Wallace, L. E., A. B. Rickinson, M. Rowe, D. J. Moss, D. J. Allen, and M. A. Epstein. 1982. Stimulation of human lymphocytes with irradiated cells of the autologous Epstein-Barr virus-transformed cell line. I. Virus-specific and nonspecific components of the cytotoxic response. Cell. Immun. 67:129-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson, A. D., J. C. Hopkins, and A. J. Morgan. 2001. In vitro cytokine production and growth inhibition of lymphoblastoid cell lines by CD4+ T cells from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) seropositive donors. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 126:101-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson, A. D., and A. J. Morgan. 2002. Primary immune responses by cord blood CD4+ T cells and NK cells inhibit Epstein-Barr virus B-cell transformation in vitro. J. Virol. 76:5071-5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young, L., C. Alfieri, K. Hennessy, H. Evans, C. O'Hara, K. C. Anderson, J. Ritz, R. S. Shapiro, A. Rickinson, E. Kieff, et al. 1989. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus transformation-associated genes in tissues of patients with EBV lymphoproliferative disease. New. Eng. Med. J. 321:1080-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]