Abstract

Objectives:

Letermovir for CMV prophylaxis in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients has decreased anti-CMV therapy use. Contrary to letermovir, anti-CMV antivirals are also active against HHV-6. We assessed changes in HHV-6 epidemiology in the post-letermovir era.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of CMV-seropositive allogeneic HCT recipients comparing time periods prior to and after routine use of prophylactic letermovir. HHV-6 testing was at the discretion of clinicians. We computed the cumulative incidence of broad-spectrum antiviral initiation (foscarnet, (val)ganciclovir, and/or cidofovir), HHV-6 testing, and HHV-6 detection in blood and cerebrospinal fluid within 100 days after HCT. We used Cox proportional-hazards models with stabilized inverse probability of treatment weights to compare outcomes between cohorts balanced for baseline factors.

Results:

We analyzed 738 patients, 376 in the pre-letermovir and 362 in the post-letermovir cohort. Broad-spectrum antiviral initiation incidence decreased from 65% (95% confidence interval [CI], 60%–70%) pre-letermovir to 21% (95% CI, 17%–25%) post-letermovir. The cumulative incidence of HHV-6 testing (17% (95% CI,13%–21%) pre-letermovir versus 13% [95% CI, 10%–16%] post-letermovir), detection (3% [95% CI, 1%–5%] in both cohorts), and HHV-6 encephalitis (0.5% [95% CI, 0.1%–1.8%] pre-letermovir and 0.6% [95% CI, 0.1%–1.9%] post-letermovir) were similar between cohorts. First HHV-6 detection occurred at a median of 37 days (IQR, 18–58) in the pre-letermovir cohort and 27 (IQR, 25–34) in the post-letermovir cohort. In a weighted model, there was no association between the pre- versus post-letermovir cohort and HHV-6 detection (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.44–2.62).

Conclusions:

Despite a large decrease in broad-spectrum antivirals after the introduction of letermovir prophylaxis in CMV-seropositive allogeneic HCT recipients, there was no evidence for increased clinically detected HHV-6 reactivation and disease.

Keywords: HHV-6, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, letermovir, CMV prophylaxis, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide

INTRODUCTION

Human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6) reactivation occurs in approximately 40–50% of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) recipients,[1] and is the most common infectious cause of encephalitis post-HCT.[2,3] HHV-6 has also been associated with acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD),[4,5] pneumonia,[6,7] and delayed engraftment.[8] HHV-6 reactivation usually occurs early after HCT, with a median time to reactivation of 21 days.[1,9] Known risk factors include umbilical cord blood transplant, T-cell depletion, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatched or unrelated donors, acute GVHD, and glucocorticoid use.[2,3,8,10,11] Recent changes in clinical practice, such as the increasing use of post-transplantation high-dose cyclophosphamide (PTCy), have been linked to a higher HHV-6 incidence. [11,12]

The timing of and risk factors for HHV-6 and cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation overlap; CMV preemptive therapy using broad-spectrum antivirals occurrs around the same time as HHV-6 reactivation.[9,13] Of note, these broad-spectrum antivirals, including ganciclovir and foscarnet, constitute first-line treatments for HHV-6 encephalitis.[14] A prophylactic effect of these antivirals has been described for HHV-6.[9,15–17] Thus, CMV reactivation and associated treatments likely influence the natural history of HHV-6 reactivation.

The development of letermovir (LTV) for CMV prophylaxis after allogeneic HCT marks a new era in CMV prevention.[18–22] LTV lacks activity against other herpesviruses, including HHV-6, and its use has led to a substantial decrease in broad-spectrum antiviral use for CMV.[21,23,24] We hypothesized that LTV use would result in increased HHV-6 reactivation incidence post-HCT.

In this study, we assess and compare the cumulative incidence of HHV-6 reactivation and encephalitis before and after LTV implementation for CMV prophylaxis after allogeneic HCT.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

Prophylactic LTV was implemented at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center (FHCC) in October 2018 for all CMV-seropositive allogeneic HCT recipients ≥18 years old. We performed a retrospective study of consecutive adult CMV-seropositive patients who received their first allogeneic HCT at FHCC between May 1st, 2015, and December 31st, 2021. Two cohorts were defined based on the date of LTV prophylaxis implementation: a pre-LTV cohort (May 2015 to September 2018) and a post-LTV cohort (October 2018 to December 2021). The time periods were chosen to provide similar intervals, follow-up, and patients for both cohorts. Patients on broad-spectrum antiviral therapy on the day of HCT were excluded. Data were included from time of HCT to up to 100 days post-HCT or until date of last contact, death, or subsequent HCT. The study was approved by the FHCC Institutional Review Board.

Antiviral Practices

Based on institutional guidelines, LTV prophylaxis was started on day +1 after cord blood HCT, day +8 after other high-risk HCT including HLA-mismatched HCT, T-cell depleted HCT and patients receiving ≥1 mg/kg prednisone, and by day +28 in all other patients. LTV was continued up to day 98 at 480 mg daily (or 240 mg if concurrent cyclosporine use).[25] In both cohorts, CMV reactivation was monitored weekly by testing plasma with a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay through day 100. CMV treatment practices are in the Supplement. Standard practices for the management of GVHD did not change during the study.

Definitions and Outcomes

HHV-6 reactivation was the primary outcome and was defined as the detection of any HHV-6 DNA in blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). HHV-6 encephalitis was defined as HHV-6 DNA detection in CSF in the context of neurological symptoms absent alternative diagnoses (secondary outcome).[14] Testing for HHV-6 (secondary outcome) was performed at the discretion of healthcare providers or according to HCT protocols using qPCR with a lower limit of detection of 50 copies/mL of plasma.[9] Broad spectrum antiviral therapy (secondary outcome) was defined as use of foscarnet, valganciclovir, ganciclovir, or cidofovir for ≥1 day.

Statistical Analysis

Date of first antiviral use, HHV-6 test, and HHV-6 detection were used for event times for each respective outcome; censoring occurred at date of last contact or 100 days post-HCT, whichever came first. We estimated the cumulative incidence with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for broad-spectrum antiviral therapy initiation, HHV-6 testing, and HHV-6 detection (in blood and/or CSF) in each cohort, treating death and subsequent HCT as competing risks. We used Gray’s test to compare the cumulative incidence between cohorts.

To compare the rate of outcomes of interest (antiviral therapy, HHV-6 testing and HHV-6 reactivation) between the pre-LTV and post-LTV cohorts while accounting for important baseline and time-dependent factors, we used cause-specific Cox regression models with stabilized inverse probability of treatment weights (SIPTW) and robust standard errors. We incorporated the computed weights into a Cox model that was also adjusted for time-dependent acute GVHD (grade ≥2 versus 0–1). Model estimates were presented as adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) with 95% CIs. Wald confidence intervals were presented. Methods used to compute weights and test the proportional hazards (PH) assumption are detailed in the Supplement. All analyses were performed using Stata/SE (version 17.0, Stata Corp LLC) or SAS version (9.4) (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Study Population

We identified 781 CMV-seropositive adult allogeneic HCT recipients during the period of interest, 403 in the pre-LTV cohort and 378 in the post-LTV cohort. Forty-three patients were receiving broad-spectrum antivirals on the day of HCT and were excluded. A total of 738 patients, 376 in the pre-LTV cohort and 362 in the post-LTV cohort, were included in the study (Table 1). Patient characteristics were similar between cohorts except for GVHD prophylaxis regimens, with increased use of PTCy in the post-LTV cohort.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Pre-LTV N=376 |

Post-LTV N=362a |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 56.4 (44.5, 64.8) | 56.7 (42.4, 65.2) |

| Female sex | 175 (46.5) | 169 (46.7) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 42 (11.2) | 35 (9.7) |

| Black | 10 (2.7) | 8 (2.2) |

| Other | 18 (4.8) | 18 (5.0) |

| White | 277 (73.7) | 277 (76.5) |

| Unknown | 29 (7.7) | 24 (6.6) |

| Underlying disease | ||

| Acute leukemia | 197 (52.4) | 195 (53.9) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 94 (25.0) | 98 (27.1) |

| Aplastic Anemia | 15 (4.0) | 15 (4.1) |

| Chronic leukemia | 31 (8.2) | 29 (8.0) |

| Lymphoma | 21 (5.6) | 8 (2.2) |

| Plasma cell disorders | 14 (3.7) | 10 (2.8) |

| Otherb | 4 (1.1) | 7 (1.9) |

| Cytomegalovirus serostatus | ||

| Donor negative, recipient positive | 203 (54.0) | 193 (53.3) |

| Donor positive, recipient positive | 173 (46.0) | 169 (46.7) |

| HLA match and donor relation | ||

| Matched related | 90 (23.9) | 68 (18.8) |

| Matched unrelated | 186 (49.5) | 197 (54.4) |

| Mismatched related | 26 (6.9) | 29 (8.0) |

| Mismatched unrelatedc | 74 (19.7) | 68 (18.8) |

| Cell source | ||

| Umbilical cord blood | 42 (11.2) | 39 (10.8) |

| Bone marrow/peripheral blood | 334 (88.8) | 323 (89.2) |

| Conditioning regimen | ||

| Myeloablatived | 124 (33.0) | 126 (34.8) |

| GVHD prophylaxis e | ||

| PTCy regimen | 39 (10.4) | 77 (21.3) |

| Non-PTCy regimen | 337 (89.6) | 285 (78.7) |

| Cyclosporine + MMF +/− other | 143 (38.0) | 127 (35.1) |

| Cyclosporine + methotrexate | 7 (1.9) | 19 (5.3) |

| Tacrolimus + MMF +/− other | 52 (13.8) | 29 (8.0) |

| Tacrolimus + methotrexate +/− other | 130 (34.6) | 109 (30.1) |

| Otherf | 5 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Acute GVHD grade | ||

| Grade 0–1 | 136 (36.2) | 130 (35.9) |

| Grade ≥2 | 240 (63.8) | 232 (64.1) |

Results are reported as number with percentage in parenthesis unless specified otherwise.

GVHD: graft-versus-host disease, HCT: hematopoietic cell transplant, HLA: human leukocyte antigen, IQR: interquartile range, LTV: letermovir, MMF: mycophenolate mofetil, PTCy: post-transplantation high-dose cyclophosphamide

35 patients in the post-LTV cohort did not receive LTV.

Other underlying diseases included: sickle cell anemia (n=2), immune deficiency disorder/disease or syndrome (n=3), chronic granulomatous disease (n=1), paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (n=1), polycythemia vera (n=1), dyskeratosis congenita (n=1), familial hemophagocytic lymphistiocytosis (n=1), multiple sclerosis (n=1).

All HLA-mismatched related HCTs were haploidentical.

Myeloablative regimens included any regimen containing ≥800 cGY total body irradiation, any regimen containing carmustine/etoposide/cytarabine/melphalan (BEAM), or any regimen containing busulfan/cyclophosphamide with or without antithymocyte globulin.

Sirolimus was included in the GVHD prophylaxis regimen in combination with cyclophosphamide-containing regimen or a non-cyclophosphamide-containing regimen in 178 patients (24.1%): 59 (15.7%) in the pre-LTV cohort and 119 (32.9%) in the post-LTV cohort.

No prophylaxis in 1 patient (syngeneic HCT) in the post-LTV cohort and tacrolimus only prophylaxis in 5 patients in pre-LTV cohort.

Letermovir and broad-spectrum antiviral use

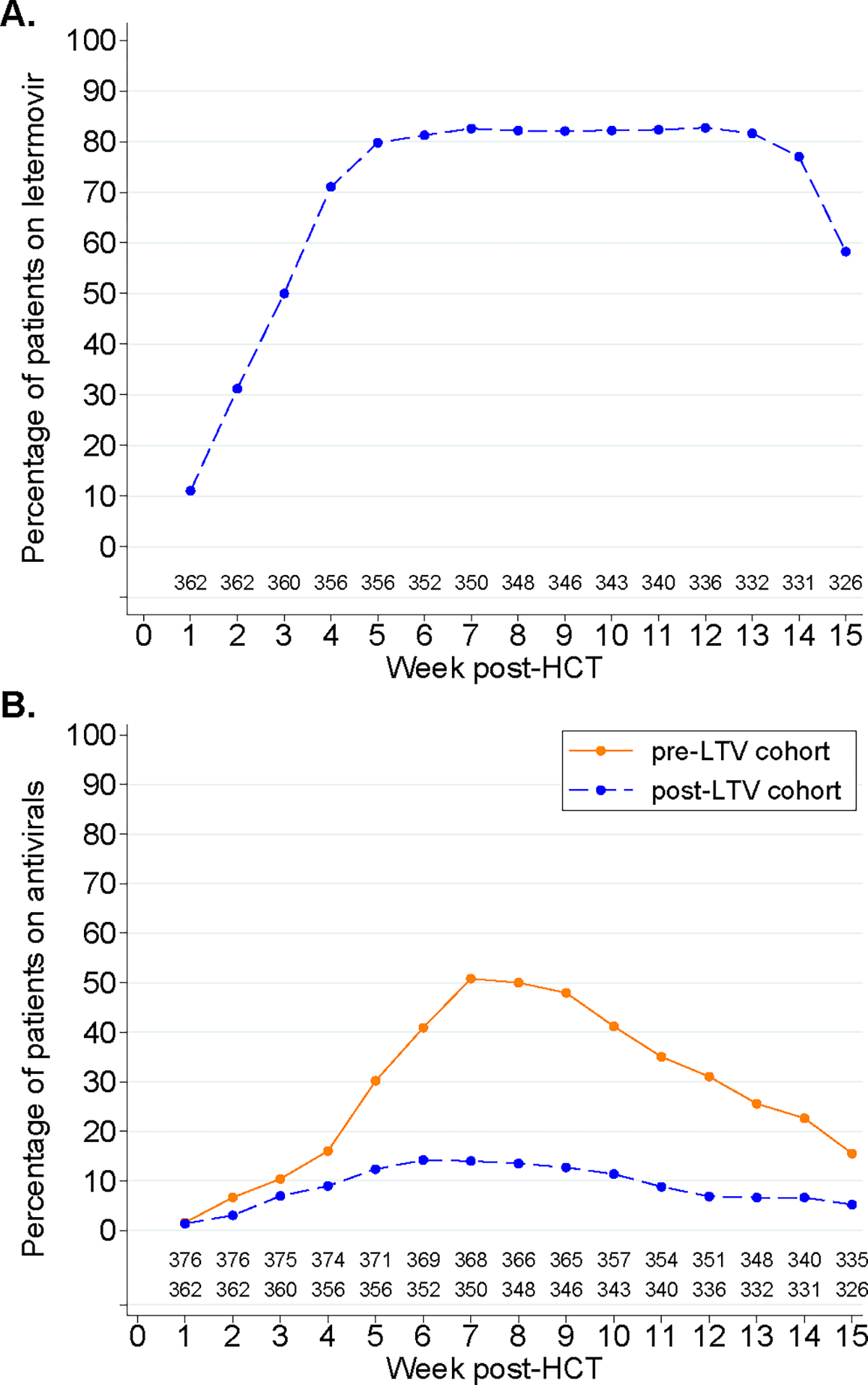

In the post-LTV cohort, 327 (90.3%) patients received LTV initiated at a median of 20 (IQR, 8–25) days after HCT. Thirty-five (9.7%) patients did not receive LTV prophylaxis due to medical or insurance reasons (Table S1); although their baseline characteristics were overall similar to patients who received LTV, their follow-up time was shorter and death rate higher (Table S2). The duration of LTV prophylaxis was 65 days per 100 patient-days. The percentage of patients receiving LTV per week through 14 weeks post-HCT is illustrated in Figure 1A.

Figure 1: Antiviral use by week.

A: Percentage of patients in the post-LTV cohort receiving letermovir per week after HCT. B: Percentage of patients receiving broad-spectrum antiviral therapy per week after HCT, stratified by cohort.

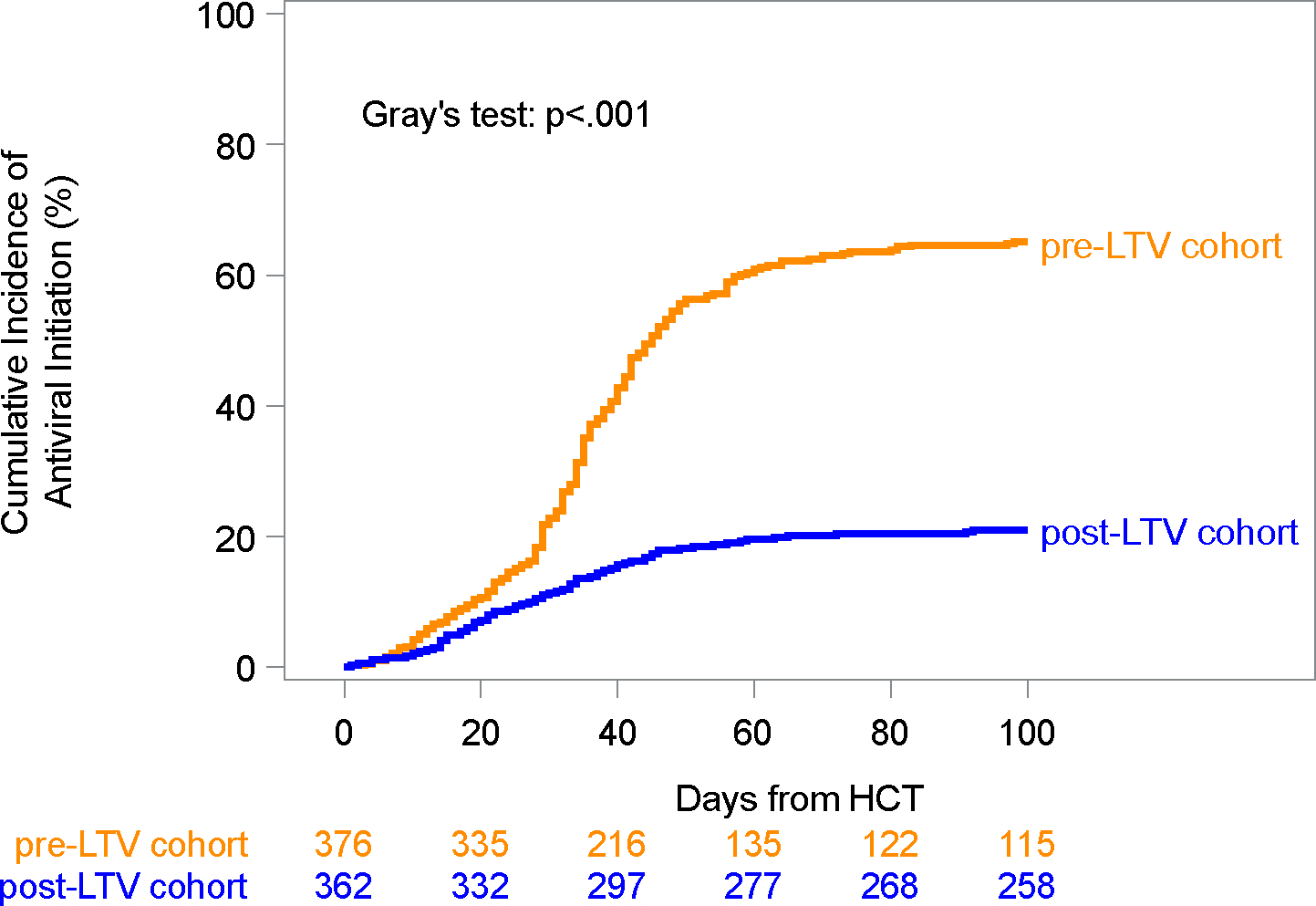

Overall, 245 (65.2%) patients in the pre-LTV cohort and 76 (21%) in the post-LTV cohort received broad-spectrum antivirals within 14 weeks post-HCT, and the cumulative incidence was significantly lower in the post-LTV cohort (21%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 17%–25%) compared to the pre-LTV cohort (65%; 95% CI, 60%–70%; p<.001) (Figure 2). The percentage of patients receiving broad-spectrum antivirals per week in each cohort is depicted in Figure 1B. Broad-spectrum antivirals were initiated a median of 35 (IQR, 28–44) and 29 (IQR, 17–41) days after HCT in the pre- and post-LTV cohorts, respectively (p=.007). Broad-spectrum antiviral duration was shorter in the post-LTV cohort (7.6 days per 100 patient-days) compared to the pre-LTV cohort (24.3 days per 100 patient-days).

Figure 2: Cumulative incidence plot of time to broad-spectrum antiviral therapy initiation.

Cumulative incidence curves of time to broad-spectrum antiviral therapy initiation within 100 days from HCT, treating death and subsequent HCT as competing risks and stratified by cohort. Cumulative incidence rates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) within 100 days from HCT: 65% (95% CI: 60–70%) in the pre-LTV cohort and 21% (95% CI: 17–25%) in the post-LTV cohort.

HHV-6 testing and detection

At least one HHV-6 test was performed in blood or CSF in 63 (16.8%) patients in the pre-LTV cohort and 46 (12.7%) in the post-LTV cohort. CSF was tested in 24 (6.4%) patients in the pre-LTV cohort and 15 (4.1%) in the post-LTV cohort (Table 2). Among tested patients, 10 of 63 (16%) in the pre-LTV cohort and 10 of 46 (22%) in the post-LTV cohort had HHV-6 detected. Among patients with a positive test, clinical manifestations were the primary indication for testing in 16 of 20 patients and the motive for testing was similar between cohorts (Table S3). The cumulative incidence of HHV-6 testing and detection was comparable between cohorts (Figure 3A–B). Cumulative incidence of HHV-6 detection and death over time using finer time categories is shown in Figure S4. There was no evidence of inherited chromosomally integrated HHV-6 in patients with HHV-6 detection based on absence of persistent viremia (with or without treatment) in those with follow up testing.

Table 2.

Characteristics of HHV-6 detection

| Summary | Pre-LTV N=376 |

Post-LTV N=362 |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with at least one HHV-6 test | 63/376 (16.8) | 46/362 (12.7) |

| Patients with at least one HHV-6 test in blood | 51/376 (13.6) | 40/362 (11.1) |

| Patients with at least one HHV-6 test in CSF | 24/376 (6.4) | 15/362 (4.1) |

| Number of tests per patient, median (range) | 1 (1, 9) | 1 (1, 16) |

| Days to first test (blood and/or CSF), median (IQR)a | 38 (18, 58) | 26 (13, 42) |

| Patients with at least one positive HHV-6 test among tested a | 10/63 (15.9) | 10/46 (21.7) |

| Patients with at least one positive HHV-6 test in blooda | 8/51 (15.7) | 10/40 (25) |

| Patients with at least one positive HHV-6 test in CSFa | 2/24 (8.3) | 2/15 (13.3) |

| Days to first positive HHV-6 test (any site), median (IQR)b | 37 (18, 58) | 26.5 (25, 34) |

| Number of positive HHV-6 tests in blood, median (IQR)c | 1 (1,1) | 2 (1,4) |

| HHV-6 viral load; log10 copies/mL, median (IQR) | ||

| Viral load in blood at first positiveb | 3.00 (2.40, 4.10) | 2.70 (2.40, 5.00) |

| Peak viral load in bloodb | 3.17 (2.51, 4.14) | 4.03 (2.89, 5.00) |

| Peak viral load in CSFd | 2.62 (2.40, 2.84) | 3.39 (3.18, 3.61) |

| Patients treated for HHV-6 e, f | 6/376 (1.6) | 4/362 (1.1) |

Results are reported as number with percentage in parenthesis unless specified otherwise.

CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, HHV-6: human herpesvirus-6, IQR: interquartile range, LTV: letermovir

Among tested patients

Among patients with a positive test (any site)

Among patients with a positive test in blood

Among patients with a positive test in CSF

Indications for treatment: in the pre-LTV cohort: neurological symptoms (n=5) (proven HHV-6 encephalitis (n=2), possible HHV-6 encephalitis (n=3)), rash (n=1); in the post-LTV cohort: altered mental status (n=3) (proven HHV-6 encephalitis (n=2), possible HHV-6 encephalitis (n=1)), delayed engraftment (n=1).

Antiviral therapy: ganciclovir in 5 patients in the pre-LTV cohort and 2 in the post-LTV cohort; foscarnet in 1 patient in the pre-LTV cohort and 2 in the post-LTV cohort.

Figure 3: Cumulative incidence plots of time to HHV-6 testing and detection.

A: Cumulative incidence curves of time to HHV-6 testing within 100 days from HCT, treating death and subsequent HCT as competing risks and stratified by cohort. Cumulative incidence rates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) within 100 days from HCT: 17% (95% CI: 13–21%) in the pre-LTV cohort and 13% (95% CI: 10–16%) in the post-LTV cohort. B: Cumulative incidence curves of time to HHV-6 detection within 100 days from HCT, treating death and subsequent HCT as competing risks and stratified by cohort. Cumulative incidence rates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) within 100 days from HCT: 3% (95% CI: 1–5%) in both cohorts.

The first positive HHV-6 test occurred at a median of 37 (IQR, 18–58) versus 27 (IQR, 25–34) days post-HCT in the pre- and post-LTV cohort, respectively (Table 2). Among patients with at least one positive test in blood, the median of positive tests was 1 (IQR, 1–1) in the pre-LTV cohort and 2 (IQR, 1–4) in the post-LTV cohort (p=0.054). The characteristics of viral detection and kinetics in blood and CSF are detailed in Table 2 and Figure S1.

Two patients in each cohort developed HHV-6 encephalitis for a cumulative incidence of 0.5% (95% CI, 0.1%–1.8%) in the pre-LTV cohort and 0.6% (95% CI, 0.1%–1.9%) in the post-LTV cohort (p=.96). Cumulative incidence curves of HHV-6 testing and detection in blood and CSF are in Figures S2–S3. Three additional patients in the pre-LTV cohort and one patient in the post-LTV cohort had altered mental status and HHV-6 detection in blood but negative CSF testing, which was performed while on broad-spectrum antivirals for CMV; they were considered to have possible HHV-6 encephalitis by the treating providers.

Adjusted comparisons for antiviral initiation and HHV-6 outcomes

To mitigate the impact of differences in key baseline characteristics between the pre-LTV and post-LTV cohort, we generated weights from propensity score models which were subsequently applied in Cox proportional hazards models. The resulting weighted sample had improved balance in key covariates between cohorts (Table S4).

In an adjusted Cox model using SIPTW, the rate of broad-spectrum antiviral initiation was significantly lower in the post-LTV cohort compared to the pre-LTV cohort after controlling for acute GVHD (Table 3). There was no significant difference between cohorts for HHV-6 testing during the first six weeks post-HCT, although after six weeks, the post-LTV cohort was associated with a lower rate of testing (Table 3). Finally, HHV-6 detection was similar in the post-LTV cohort compared to the pre-LTV cohort, while grade ≥2 acute GVHD was associated with HHV-6 detection. We found similar results in an analysis incorporating time-dependent LTV use as the primary independent variable in place of the specified cohorts (data not shown).

Table 3:

Cox model estimates for outcomes of antiviral therapy initiation, HHV-6 testing and HHV-6 detection incorporating propensity score weighting for baseline variables

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence intervals) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Antiviral initiation | therapy |

|

| |

| Cohort | |

| Pre-LTV cohort | Ref |

| Post-LTV cohorta | |

| < 4 weeks post-HCT | 0.57 (0.38–0.87) |

| ≥ 4 weeks post-HCT | 0.14 (0.10–0.20) |

| Acute GVHD grade | |

| 0–1 | Ref |

| ≥ 2 | 2.17 (1.71–2.75) |

|

| |

| Tested for HHV-6 | |

|

| |

| Cohort | |

| Pre-LTV cohort | Ref |

| Post-LTV cohorta | |

| < 6 weeks post-HCT | 1.1 (0.68–1.78) |

| ≥ 6 weeks post-HCT | 0.36 (0.18–0.72) |

| Acute GVHD grade | |

| 0–1 | Ref |

| ≥ 2 | 1.63 (1.03–2.58) |

|

| |

| HHV-6 detected | |

|

| |

| Cohort | |

| Pre-LTV cohort | Ref |

| Post-LTV cohort | 1.08 (0.44–2.62) |

| Acute GVHD grade | |

| 0–1 | Ref |

| ≥ 2 | 3.53 (1.31–9.49) |

GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HHV-6: human herpesvirus 6; LTV: letermovir

Adjusted Cox models used stabilized inversed probability of treatment weights (SIPTW) to balance baseline variables associated with the pre-LTV and post-LTV cohorts. Variables that were incorporated into IPTW weighting are summarized in Table S4. Acute GVHD was separately included in the model as a time-dependent variable.

Due to violations of the proportional hazards assumption for cohort, we added a time-interval-cohort interaction term to these models to compute separate cohort adjusted hazard ratios for time intervals in which the proportional hazards assumption seemed plausible; these time intervals were <4 and ≥4 weeks for antiviral therapy and <6 vs ≥6 weeks for HHV-6 testing.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 781 CMV-seropositive adult allogeneic HCT recipients, we observed that despite the significant decrease in the use and duration of broad-spectrum antivirals in the post-LTV cohort compared to the pre-LTV cohort, there were no significant differences in the incidence of clinically detected HHV-6 reactivation or encephalitis, although this needs validation from studies with systematic virological testing.

Based on the significant decrease in broad-spectrum antiviral use observed in prior studies and confirmed in our cohort after the implementation of LTV prophylaxis,[21,23,24] we anticipated that the incidence of HHV-6 reactivation and disease would be higher post-LTV. However, contrary to our hypotheses, the incidence of clinically detected HHV-6 reactivation was similar between cohorts, but the lack of systematic virological testing and few events preclude definitive conclusions. This was confirmed in an adjusted Cox model weighted to achieve balance between cohorts in key baseline characteristics and controlling for acute GVHD. In the pre-LTV era, HHV-6 detection has been reported in up to ~60% of HCT recipients by day 100 when tested weekly,[1,11,13] while clinically relevant HHV-6 infection defined by the presence of clinical manifestations (end-organ disease and/or other possible associations) was present in 52 of 208 (25%) in a recently published study.[11] In our study, only 17% of patients in the pre-LTV cohort and 13% in the post-LTV cohort had any HHV-6 testing with a median of one test per patient, which precludes direct comparisons with studies using weekly testing. However, the clinically detected HHV-6 incidence of 3% corroborates previous studies reporting HHV-6 reactivation in approximately 4% of patients based on clinically driven testing.[12,26,27] Reassuringly, we identified a similar incidence of HHV-6 encephalitis in the pre-LTV (0.5%) and post-LTV (0.6%) cohorts. As in prior studies,[2,28] acute GVHD grade ≥2 remained an important predictor for antiviral therapy, HHV-6 testing, and HHV-6 reactivation, irrespective of cohort.

Although there was no clear difference in the incidence of HHV-6 reactivation and disease, HHV-6 detection was shifted to earlier after HCT in the post-LTV compared to the pre-LTV cohort by a median of 10 days. Given that immune reconstitution after HCT improves with time, earlier HHV-6 reactivation could result in higher risk for HHV-6-related adverse outcomes due to reduced immunologic control.[4] The more frequent use and longer duration of broad-spectrum antivirals in the pre-LTV cohort likely contributed to the later timeline of HHV-6 reactivation observed in that cohort. Similar findings were observed in a study after solid organ transplantation where CMV-directed ganciclovir prophylaxis was associated with delayed onset and shorter duration of HHV-6 reactivation.[29]

Approximately 9% of patients in the post-LTV cohort did not receive LTV due to insurance or medical reasons, which is comparable to other real-world settings.[23] Our rational for including all patients in the post-LTV cohort, irrespective of whether they received LTV or not, was to take an unbiased approach to describe the epidemiology of clinically relevant HHV-6 reactivation in a real-world cohort. Nevertheless, we also evaluated LTV use in Cox models including receipt of LTV as a time-dependent variable in place of the cohort variable, and this did not influence our results.

Our study also has limitations; the lack of systematic testing for HHV-6 precludes a comprehensive understanding of the true incidence and characteristics of HHV-6 reactivation and our findings likely underestimate the true incidence of HHV-6 reactivation. However, the stable incidence of HHV-6 encephalitis, a key clinical outcome related to HHV-6 reactivation, is reassuring. Our models indicated that HHV-6 testing was lower in the post-LTV cohort after week six, suggesting that clinical suspicion for HHV-6 may have been lower in the post-LTV cohort. Another way to interpret this finding is that in the post-LTV cohort, HHV-6 was detected less frequently due to less testing. However, most HHV-6 reactivation and diagnoses of encephalitis occur by six weeks post-HCT in studies with weekly testing,[11,13] as also demonstrated in this study, so this difference is unlikely to have substantially influenced our results.

We could consider various potential explanations for the lack of association between LTV use and the epidemiology of HHV-6. It is possible that unmeasured differences in management of GVHD over time impacted our findings, although our models accounted for apparent differences (e.g., PTCy). We note that the use of PTCy was twice as common in the post-LTV cohort, but we nonetheless did not see a higher incidence of HHV-6 encephalitis. Reduced CMV reactivation in the post-LTV era could mitigate immunomodulatory effects attributed to CMV that have been associated with increased risk for HHV-6 reactivation.[31,32] Early T-cell reconstitution is known to protect against HHV-6 reactivation.[4,11] Mounting evidence suggests that LTV is associated with improved immune reconstitution, both through the decreased use of myelotoxic antivirals (e.g., ganciclovir) and though the prevention of CMV-induced T-cell repertoire skewing.[27,33,34] Finally, it is plausible that broad-spectrum antiviral use for CMV did not have as much of an anticipated prophylactic effect on HHV-6 due to HHV-6 reactivation often occurring earlier than CMV reactivation and treatment.[9,13]

In conclusion, there was no evidence for increased clinically detected HHV-6 reactivation or disease in patients receiving LTV for CMV prophylaxis after allogeneic HCT, despite the substantially lower utilization of broad-spectrum antiviral therapy. Whether the variations in peak viral loads or in the timeline of HHV-6 reactivation are of clinical importance remains to be determined. Future studies with systematic testing (both within and beyond 100 days from HCT) will be important to determine the epidemiology and kinetics of HHV-6 and other double-stranded DNA viruses in the post-LTV era and to inform the design of prophylactic trials.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) (P500PM_202961 to E.K.), SICPA Foundation (to E.K.), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (5K23AI163343-03 to D.Z and P30 CA015704-47 to J.A.H).

Footnotes

Transparency declaration

Potential conflicts of interest:

D.M.Z. has served as a consultant for a clinical endpoint adjudication committee for AlloVir and has received research support from Merck.

M.J.B. has served as a consultant for Symbio, AlloVir, and Merck and has received research support from Merck.

J.A.H. has served as a consultant for Symbio, Gilead, and AlloVir and has received research support from Merck and AlloVir.

References

- [1].Zerr DM, Boeckh M, Delaney C, Martin PJ, Xie H, Adler AL, et al. HHV-6 reactivation and associated sequelae after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2012;18:1700–8. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hill JA, Koo S, Guzman Suarez BB, Ho VT, Cutler C, Koreth J, et al. Cord-blood hematopoietic stem cell transplant confers an increased risk for human herpesvirus-6-associated acute limbic encephalitis: a cohort analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2012;18:1638–48. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ogata M, Oshima K, Ikebe T, Takano K, Kanamori H, Kondo T, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of human herpesvirus-6 encephalitis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2017;52:1563–70. 10.1038/bmt.2017.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Admiraal R, de Koning CCH, Lindemans CA, Bierings MB, Wensing AMJ, Versluys AB, et al. Viral reactivations and associated outcomes in the context of immune reconstitution after pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;140:1643–1650.e9. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.12.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Phan TL, Carlin K, Ljungman P, Politikos I, Boussiotis V, Boeckh M, et al. Human Herpesvirus-6B Reactivation Is a Risk Factor for Grades II to IV Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2018;24:2324–36. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hill JA, Vande Vusse LK, Xie H, Chung EL, Yeung CCS, Seo S, et al. Human Herpesvirus 6B and Lower Respiratory Tract Disease After Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 2019;37:2670–81. 10.1200/JCO.19.00908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Seo S, Renaud C, Kuypers JM, Chiu CY, Huang M-L, Samayoa E, et al. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after hematopoietic cell transplantation: evidence of occult infectious etiologies. Blood 2015;125:3789–97. 10.1182/blood-2014-12-617035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zerr DM, Corey L, Kim HW, Huang M-L, Nguy L, Boeckh M. Clinical outcomes of human herpesvirus 6 reactivation after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis an Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2005;40:932–40. 10.1086/428060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hill JA, Mayer BT, Xie H, Leisenring WM, Huang M-L, Stevens-Ayers T, et al. Kinetics of Double-Stranded DNA Viremia After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Clin Infect Dis an Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2018;66:368–75. 10.1093/cid/cix804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Perruccio K, Sisinni L, Perez-Martinez A, Valentin J, Capolsini I, Massei MS, et al. High Incidence of Early Human Herpesvirus-6 Infection in Children Undergoing Haploidentical Manipulated Stem Cell Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2018;24:2549–57. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Noviello M, Lorentino F, Xue E, Racca S, Furnari G, Valtolina V, et al. Human herpesvirus 6-specific T-cell immunity in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Blood Adv 2023:bloodadvances.2022009274. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022009274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Singh A, Dandoy CE, Chen M, Kim S, Mulroney CM, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, et al. Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide Is Associated with an Increase in Non-Cytomegalovirus Herpesvirus Infections in Patients with Acute Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Transplant Cell Ther 2022;28:48.e1–48.e10. 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hill JA, Mayer BT, Xie H, Leisenring WM, Huang M-L, Stevens-Ayers T, et al. The cumulative burden of double-stranded DNA virus detection after allogeneic HCT is associated with increased mortality. Blood 2017;129:2316–25. 10.1182/blood-2016-10-748426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ward KN, Hill JA, Hubacek P, de la Camara R, Crocchiolo R, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines from the 2017 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia for management of HHV-6 infection in patients with hematologic malignancies and after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica 2019;104:2155–63. 10.3324/haematol.2019.223073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ljungman P, Dahl H, Xu Y-H, Larsson K, Brytting M, Linde A. Effectiveness of ganciclovir against human herpesvirus-6 excreted in saliva in stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007;39:497–9. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ogata M, Takano K, Moriuchi Y, Kondo T, Ueki T, Nakano N, et al. Effects of Prophylactic Foscarnet on Human Herpesvirus-6 Reactivation and Encephalitis in Cord Blood Transplant Recipients: A Prospective Multicenter Trial with an Historical Control Group. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant 2018;24:1264–73. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hill JA, Nichols WG, Marty FM, Papanicolaou GA, Brundage TM, Lanier R, et al. Oral brincidofovir decreases the incidence of HHV-6B viremia after allogeneic HCT. Blood 2020;135:1447–51. 10.1182/blood.2019004315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ljungman P, de la Camara R, Robin C, Crocchiolo R, Einsele H, Hill JA, et al. Guidelines for the management of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with haematological malignancies and after stem cell transplantation from the 2017 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 7). Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:e260–72. 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hakki M, Aitken SL, Danziger-Isakov L, Michaels MG, Carpenter PA, Chemaly RF, et al. American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Series: #3—Prevention of Cytomegalovirus Infection and Disease After Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther 2021;27:707–19. 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dadwal SS, Papanicolaou GA, Boeckh M. How I Prevent Viral Reactivation in High-risk Patients. Blood 2022. 10.1182/blood.2021014676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Marty FM, Ljungman P, Chemaly RF, Maertens J, Dadwal SS, Duarte RF, et al. Letermovir Prophylaxis for Cytomegalovirus in Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2433–44. 10.1056/NEJMoa1706640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chemaly RF, Ullmann AJ, Ehninger G. CMV prophylaxis in hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2014;371:576–7. 10.1056/NEJMc1406756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Su Y, Stern A, Karantoni E, Nawar T, Han G, Zavras P, et al. Impact of Letermovir Primary Cytomegalovirus Prophylaxis on 1-Year Mortality After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:795–804. 10.1093/cid/ciab1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sassine J, Khawaja F, Shigle TL, Handy V, Foolad F, Aitken SL, et al. Refractory and Resistant Cytomegalovirus After Hematopoietic Cell Transplant in the Letermovir Primary Prophylaxis Era. Clin Infect Dis an Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2021;73:1346–54. 10.1093/cid/ciab298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Perchetti GA, Biernacki MA, Xie H, Castor J, Joncas-Schronce L, Ueda Oshima M, et al. Cytomegalovirus breakthrough and resistance during letermovir prophylaxis. Bone Marrow Transplant 2023. 10.1038/s41409-023-01920-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hill JA, Moon SH, Chandak A, Zhang Z, Boeckh M, Maziarz RT. Clinical and Economic Burden of Multiple Double-Stranded DNA Viral Infections after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther 2022;28:619.e1–619.e8. 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Royston L, Royston E, Masouridi-Levrat S, Vernaz N, Chalandon Y, Van Delden C, et al. Letermovir Primary Prophylaxis in High-Risk Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients: A Matched Cohort Study. Vaccines 2021;9. 10.3390/vaccines9040372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ogata M, Satou T, Kawano R, Takakura S, Goto K, Ikewaki J, et al. Correlations of HHV-6 viral load and plasma IL-6 concentration with HHV-6 encephalitis in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:129–36. 10.1038/bmt.2009.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Galarraga MC, Gomez E, de Oña M, Rodriguez A, Laures A, Boga JA, et al. Influence of ganciclovir prophylaxis on citomegalovirus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 7 viremia in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2005;37:2124–6. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ogata M, Satou T, Kadota J, Saito N, Yoshida T, Okumura H, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) reactivation and HHV-6 encephalitis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a multicenter, prospective study. Clin Infect Dis an Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2013;57:671–81. 10.1093/cid/cit358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sen P, Wilkie AR, Ji F, Yang Y, Taylor IJ, Velazquez-Palafox M, et al. Linking indirect effects of cytomegalovirus in transplantation to modulation of monocyte innate immune function. Sci Adv 2023;6:eaax9856. 10.1126/sciadv.aax9856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Freeman RBJ The ‘Indirect’ Effects of Cytomegalovirus Infection. Am J Transplant 2009;9:2453–8. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Suessmuth Y, Mukherjee R, Watkins B, Koura DT, Finstermeier K, Desmarais C, et al. CMV reactivation drives posttransplant T-cell reconstitution and results in defects in the underlying TCRβ repertoire. Blood 2015;125:3835–50. 10.1182/blood-2015-03-631853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Meyer E CMV after transplant: T-cell repertoire crooks. Blood 2015;125:3827–8. 10.1182/blood-2015-04-640664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.