Abstract

As we age, the ability to regenerate and repair skeletal muscle damage declines, partially due to increasing dysfunction of muscle resident stem cells—satellite cells (SC). Recent evidence implicates cellular senescence, which is the irreversible arrest of proliferation, as a potentiator of SC impairment during aging. However, little is known about the role of senescence in SC, and there is a large discrepancy in senescence classification within skeletal muscle. The purpose of this study was to develop a model of senescence in skeletal muscle myoblasts and identify how common senescence-associated biomarkers respond. Low-passage C2C12 myoblasts were treated with bleomycin or vehicle and then evaluated for cytological and molecular senescence markers, proliferation status, cell cycle kinetics, and differentiation potential. Bleomycin treatment caused double-stranded DNA breaks, which upregulated p21 mRNA and protein, potentially through NF-κB and senescence-associated super enhancer (SASE) signaling (p < 0.01). Consequently, cell proliferation was abruptly halted due to G2/M-phase arrest (p < 0.01). Bleomycin-treated myoblasts displayed greater senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining (p < 0.01), which increased over several days. These myoblasts remained senescent following 6 days of differentiation and had significant impairments in myotube formation (p < 0.01). Furthermore, our results show that senescence can be maintained despite the lack of p16 gene expression in C2C12 myoblasts. In conclusion, bleomycin treatment provides a valid model of damage-induced senescence that was associated with elevated p21, reduced myoblast proliferation, and aberrant cell cycle kinetics, while confirming that a multi-marker approach is needed for the accurate classification of senescence within skeletal muscle.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-023-00929-9.

Keywords: Senescence, Skeletal muscle, Myoblast, Aging, Bleomycin

Introduction

Skeletal muscle is a highly plastic tissue that can repair and regenerate following damage caused by exercise, injury, or systemic inflammation that occurs with aging [1]. Skeletal muscle’s regenerative potential is accounted for by resident muscle stem cells, referred to as satellite cells (SC). Investigations in rodents and humans have described a decline in SC number with aging [2–4]. The loss of SC content is exacerbated by their dysfunction, which further limits the regenerative potential of this stem cell population [2, 3, 5]. While data across species is conflicting, research from human tissue suggests a reduction in SC number and impairments in SC function may be associated with the inevitable loss of skeletal muscle mass associated with aging [6–8].

There is increasing evidence for the role of senescence as a mediator of cellular dysfunction in aged skeletal muscle. Cellular senescence is a homeostatic response to extrinsic or intrinsic stressors that prevent the proliferation of damaged cells [9]. This phenomenon is largely characterized by the stable arrest of the cell cycle and can be roughly classified into two groups: replicative senescence and damage-induced senescence [9, 10]. Replicative senescence occurs primarily due to telomeric damage from consistent proliferation, whereas damage-induced senescence can be prematurely triggered by stressors such as impaired autophagy, elevated ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction, or aberrant intercellular signalling [9, 11–13]. These stressors induce a senescent phenotype by altering senescence-associated gene expression, such as the p53-p21 and p16-pRB pathways, which promote cell cycle arrest and apoptotic resistance [9]. In some circumstances, senescence can be beneficial as it prevents the propagation of damaged and potentially mutagenic cells, and its absence can lead to uncontrolled proliferation and tumorigenesis [9]. However, senescence can also have negative implications in cells that are required for the maintenance of tissue homeostasis, such as SC. Senescence of SC could inhibit their activation and expansion, ultimately impairing myogenesis and preventing the regeneration of damaged skeletal muscle [14]. It is unlikely that replicative senescence is associated with aging-related SC dysfunction as these cells have robust telomerase activity that protects against telomere attrition in elderly muscle [15]. It is more likely that extensive damage caused by the aged microenvironment, such as impaired autophagy and increased ROS production, could elicit significant cellular and genomic damage and ultimately induce senescence in SC.

Cellular senescence is a highly dynamic process, and while it has been examined across several tissues and species, its study within skeletal muscle is still in its early stages [16]. Currently, there is a paucity of literature investigating the role of senescence in SC, and a muscle cell model of senescence would be valuable in elucidating the role this phenomenon plays in muscle physiology. Thus, we sought to establish and validate a model of cellular senescence in skeletal muscle myoblasts and evaluate the immediate and long-term response of the most common biomarkers of senescence. We opted to use bleomycin, a chemotherapeutic agent that has been shown to induce senescence in lung epithelial cells by triggering single-stranded and double-stranded DNA breaks [17–19]. Our experimental procedures were designed to evaluate the potential of bleomycin to induce senescence and to investigate the impact of damage-induced senescence on skeletal muscle myoblasts. First, we developed and validated a novel, in vitro, model of myoblast senescence. We then determined the acute response to senescence induction by utilizing several molecular and cytological techniques. Lastly, we evaluated the impact on myoblast differentiation and myotube formation following an extended period of senescence.

Methods

Cell culture and myoblast differentiation

C2C12 myoblasts were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Cedarlane) and cultured in 150-mm tissue culture dishes in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Cells were grown in a growth medium (GM) composed of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). GM was changed every day, and cells were passaged using 0.25% Trypsin–EDTA (Gibco) when 60% confluent. Differentiation was induced when cells were ~ 90% confluent with differentiation medium (DM) composed of DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum (Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin; DM was changed every 48 h. Experiments were conducted with cells at passages 6–8, and technical duplicates were averaged to create each N, with a total N = 3 per condition and time point.

Senescence induction with bleomycin

Bleomycin sulfate (Cayman Chemical) was dissolved in nitrogen-purged dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at the indicated concentrations. C2C12 myoblasts were seeded onto 6-, 12-, or 94-well plates and allowed to adhere for 12 h prior to treatment. At 50–60% confluence, cells were treated with bleomycin (3.5–70 μM) or vehicle (isovolumetric nitrogen-purged DMSO) for the indicated duration. Final concentrations were prepared in fresh GM, and the volume of bleomycin and DMSO did not exceed 0.2% of the total volume of media. Cells were then collected for subsequent analysis or washed twice with sterile 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco) and replaced with fresh GM or DM, based on experimental design.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity

C2C12 myoblasts were stained for senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal), a commonly used marker to identify senescent cells [20]. Following treatment, cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS and fixed with 1 × fixative solution (Cell Signalling Technologies) for 10 min. Cells were washed again and then incubated with β-galactosidase staining solution (pH 6.0, Cell Signalling Technologies) in a dry, 37 °C incubator for 16 h. Images were captured through phase-contrast microscopy on the Eclipse TI2 microscope (Nikon), 20X objective. Cells were analyzed with NIS-Elements (V4.40, Nikon) to determine the percentage of SA-β-gal-positive cells. An automated stage moved the plate to five predetermined ROIs before image capture to prevent selection bias, and an average of 650 ± 204 cells were counted per well. All samples within the same comparison were stained and imaged at the same time to minimize between-batch discrepancies.

Cell concentration and viability

Live and total cell counts and cell viability were determined via trypan blue infiltration. Cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS and dissociated using 0.25% Trypsin–EDTA. Once trypsinized, the cells were collected with an equal volume of serum-containing GM and centrifuged at 200 g for 5 min. PBS solution was retained after each wash and added to the final trypsin + cell solution prior to centrifugation to ensure that nonadherent dead cells were included in the quantification. Cells were then resuspended in fresh GM and equal volumes of cell suspension and 0.4% trypan blue (Corning) were gently mixed. 10 μL of the cell + trypan blue solution was loaded onto both sides of a cell counting chamber slide (Invitrogen) and imaged with a Countess automated cell counter (Invitrogen). Live (non-blue) and dead (blue) cells were counted, and viability was reported as a percentage of live cells relative to the total cell count.

Cell proliferation

Cell proliferation was determined using a colorimetric MTT assay as previously reported [21]. C2C12 myoblasts were plated in a 96-well plate and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Cells were then treated with bleomycin (14 μM) or isovolumetric DMSO for 12 h. Following treatment, media was removed and 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in 1 × PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) combined with 180 μL of DMEM (final concentration of MTT = 0.5 mg/mL) was added to each well. Cells were placed in an incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) for 3 h. MTT + DMEM solution was removed and 200 μL of DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 590 nm (Synergy™ Mx, Biotek) and positively correlates with live cell count [21].

Flow cytometry

C2C12 myoblasts were incubated with bleomycin or DMSO (vehicle) for 12 h then washed twice, collected, and filtered through a 35-μm cell strainer into flow tubes (Corning). All antibodies and dyes used for flow cytometry are detailed in Online Resource, Table S1. Tubes were centrifuged at 500 g, and cells were resuspended in PBS. Cells were then pelleted and PBS was removed before ice-cold 70% ethanol was added dropwise to the cells under gentle agitation. Myoblasts were fixed for 30 min at 4 °C and then pelleted and washed twice with 1 × PBS before being resuspended in 500 μL of propidium iodide (PI) solution (5 μg/mL of PI and 20 μg/mL of RNase A in 1 × PBS). Cell cycle kinetics was determined based on PI fluorescence using a Cytoflex LX (Beckman Coulter) and quantified with FlowJo (V10.8.1, BD Biosciences). Representative dot plots for cell cycle analysis can be found in Online Resource, Fig. S1.

To evaluate DNA damage, cells were stained and subjected to flow cytometry for γH2AX, which is a commonly used indicator of double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) [22]. Following treatment with bleomycin or DMSO, cells were collected, washed, and filtered into flow tubes. Cells were then incubated with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Violet dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min in the dark. The mixture was then washed twice with 1 × PBS and fixed for 20 min at 4 °C with BD Cytofix (BD Biosciences). Following fixation, cells were pelleted and then washed twice with perm/wash buffer (BD Biosciences) before blocking for 20 min (1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 10% goat serum in perm/wash). Cells were again pelleted and resuspended in Alexa Fluor® 555 anti-γH2AXser139 for 2 h at room temperature. The cells were washed twice with perm/wash buffer and resuspended in 250 μL of PBS for flow cytometry analysis. Representative dot plots for γH2AX staining can be found in Online Resource, Fig. S2.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Treated C2C12 myoblasts were collected with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and RNA was isolated using the E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek) as per manufacturer instructions. Isolated RNA concentration and purity were determined using the Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), after which 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Amplification of genes of interest was performed using TaqMan assays (Online Resource, Table S2) and Taqman Fast Advanced Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cq values were obtained in triplicate and relative gene expression data were normalized to the geometric mean of reference genes Gapdh and Tbp using the comparative 2−ΔΔCq method [23]. A no template control (NTC) was used for each probe to confirm the absence of contamination or non-specific amplification.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

Myoblasts were lysed with ice-cold RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with Pierce protease inhibitor (Thermo Scientific) and phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were sonicated and then centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 min to pellet debris. Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic assay (BCA; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and samples were diluted to a final concentration of 1 μg/μL. 10 μg of total protein was loaded into each lane of a 4–15% TGX precast gel (Bio-Rad) and underwent SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and stained with Ponceau S solution (Sigma-Aldrich) to assess equal loading between samples. Ponceau solution was removed with 3 × 5-min washes with Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T), and membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS-T for 1 h. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in 5% BSA in TBS-T (Online Resource, Table S1). The next day, membranes were washed 3 times with TBS-T and incubated with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted at 1: 10,000 in 5% BSA in TBS-T for 2 h. Bands were visualized upon the addition of ECL solution (Bio-Rad). Images were captured with the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad) and quantified using Image Lab software (V6.0.1, Bio-Rad). All bands were normalized to their corresponding Ponceau S image, and a loading control was utilized whenever samples were compared across multiple gels.

Immunocytochemistry

C2C12 myoblasts were plated in Lab-Tek chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and allowed to adhere for 12 h prior to incubation with bleomycin (14 μM) or DMSO. Cells were then washed twice with 1 × PBS and incubated with DM, which was refreshed every 2 days. After 6 days of differentiation, myotubes were washed with 1 × PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min. Myotubes were permeabilized for 20 min with 0.1% Triton-X in PBS before blocking with 2% BSA in PBS for 1 h. Myosin heavy chain (MyHC) supernatant was incubated overnight at 4 °C to label myotubes (Online Resource, Table S1). The next morning, myotubes were washed twice with 1 × PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen) at 1: 500 in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. Chamber slides were washed twice with 1 × PBS before incubation with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min to label nuclei. Slides were washed and mounted with a fluorescence mounting medium (DAKO). Myotubes were imaged at 20 × magnification using an Eclipse TI2 microscope (Nikon) and analyzed with NIS-Elements (V4.40, Nikon).

For immunofluorescent visualization of p53 protein, myoblasts were washed with PBS immediately following 12 h of treatment before fixation with 4% PFA. Cells were then washed and blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 1 h. Next, myoblasts were incubated overnight at 4 °C with p53 antibody (Online Resource, Table S1). After a two-hour incubation with Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1: 500 in PBS), cells were washed with PBS and stained with DAPI. DAKO-mounted slides were imaged at 20 × magnification with an Eclipse TI2 microscope (Nikon). Nuclear p53 content was calculated as the total FITC fluorescence intensity that overlaps with DAPI, divided by the binary threshold area of DAPI. Cytosolic p53 protein was calculated as the total FITC fluorescence intensity minus the FITC fluorescence intensity that overlaps with DAPI, and then divided by the difference between the binary threshold areas of FITC and DAPI.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (V8.4.0, Graphpad Software LLC). For statistical comparisons of two groups, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests were employed. For all other comparisons, a one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed. Normality was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk test and in the case of non-normal data, a non-parametric test was utilized. When a significant interaction effect was detected, a Bonferroni post hoc test was performed. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Results

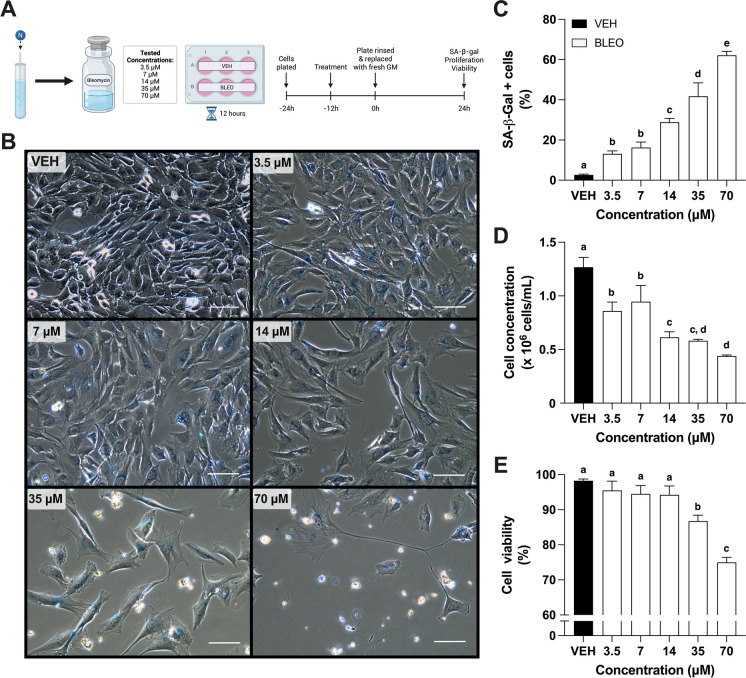

Dose–response characteristics of bleomycin treatment

Cellular senescence can be induced by a variety of stimuli, including telomere shortening, non-telomeric DNA damage, and oncogenic signaling, amongst others [9]. To investigate senescence in skeletal muscle myoblasts, we sought to develop a model of DNA damage-induced senescence using the chemotherapeutic drug, bleomycin. Low confluency (~ 50%) C2C12 myoblasts were treated with vehicle (VEH) or bleomycin (BLEO) at several concentrations (3.5–70 μM) for 12 h and then stained or counted 24 h later (Fig. 1A). Cellular senescence was quantified with the well-established senescence marker SA-β-gal (β-gal). At every concentration, BLEO treatment resulted in more β-gal-positive cells relative to VEH (p < 0.01; Fig. 1B, C). As the concentration rose beyond 7 μM, the percentage of β-gal-positive cells increased stepwise to 70 μM (16.2 ± 2.7% vs. 62.1 ± 2.0%; p < 0.01). In line with these findings, cell concentration was lower in all BLEO groups compared to VEH (p < 0.01) and followed a stepwise pattern of decline, with 70 μM having the lowest concentration (4.38 × 105 ± 1.1 × 104 cells/mL; Fig. 1D), indicating a reduction in cell number with bleomycin treatment. Cell viability was maintained at 3.5, 7, and 14 μM BLEO relative to VEH (all groups > 94% alive) but decreased at 35 μM (p < 0.01; 86.8 ± 1.7%) and 70 μM (p < 0.01; 75.0 ± 1.4%; Fig. 1E). Despite experiencing the largest proportion of β-gal-positive cells and the lowest cell concentrations, treatment at 35 μM or 70 μM caused too large of an apoptotic response for a model of cellular senescence. Therefore, we opted to use a concentration of 14 μM for the remainder of the experiments.

Fig. 1.

Bleomycin dose–response relationship in C2C12 myoblasts. A Schematic representing drug preparation and experimental design. Bleomycin (BLEO) was prepared in nitrogen-purged dimethyl sulfoxide (VEH) and then diluted to various concentrations (3.5–70 μM). All groups were treated for 12 h, and then, growth media was replenished for 24 h prior to collection. B Representative phase contrast microscopy images of myoblasts stained for SA-β-gal at pH 6.0, captured 24 h after dosing with VEH or BLEO at displayed concentrations. Graphical quantification of C SA-β-gal–positive cells, D cell concentration, and E cell viability of treated myoblasts. Data are means ± SD. Means that do not share a letter are statistically different (p < 0.01)

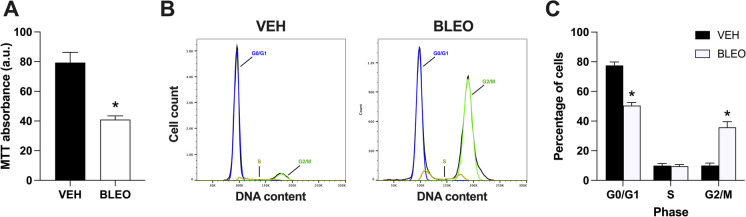

Myoblast proliferation and cell cycle kinetics following bleomycin treatment

Further, we evaluated the impact of bleomycin treatment on myoblast proliferation and cell cycle kinetics. C2C12 myoblasts (~ 50% confluent) were treated with BLEO (14 μM) or VEH for 12 h. Immediately following treatment, BLEO-treated cells had significantly lower MTT absorbance, representing a nearly 50% decrease in proliferation (p < 0.01; Fig. 2A). Next, treated cells were collected and stained with PI to examine cell cycle kinetics (Fig. 2B). There was a significant reduction in the G0/G1 phase of BLEO (50.5 ± 2.0%) relative to VEH (77.5 ± 2.3%) treated myoblasts (p < 0.01; Fig. 2C). No differences were observed in the S phase between conditions, but there was a larger G2/M phase in the BLEO (35.8 ± 3.8%) versus VEH (10.0 ± 1.7%) group (p < 0.01). These findings indicate that bleomycin treatment arrested myoblasts in the G2/M phase, and this corresponds with a significant reduction in cell proliferation.

Fig. 2.

Myoblast proliferation and cell cycle kinetics in senescent myoblasts. A Cell proliferation was assessed by an MTT assay and measured immediately following 12 h of VEH or BLEO (14 μM) treatment. Lower detected absorbance is indicative of reduced proliferation (a.u. (arbitrary units)). B Representative flow cytometry histograms of treated myoblasts stained with propidium iodide (PI) directly after treatment. DNA content is determined by PI intensity. C Graphical quantification of the percentage of cells found in each phase of the cell cycle. Data are means ± SD. * denotes a significant difference from VEH (p < 0.01)

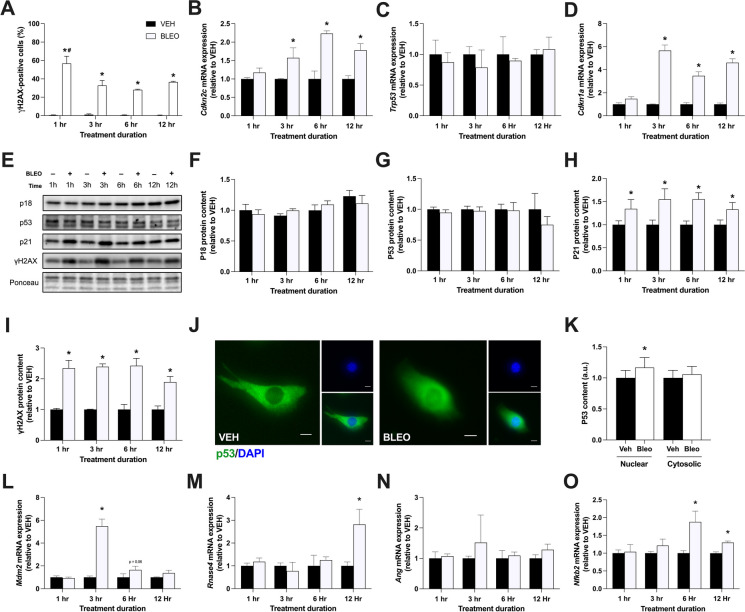

Sampling time affects the molecular signature of senescence

Since cell-cycle arrest is not exclusive to senescence [24], we next evaluated the acute response of several molecular markers to bleomycin-induced cell senescence. C2C12 myoblasts (~ 50% confluent) were treated with VEH or BLEO (14 μM) for 1, 3, 6, or 12 h and collected immediately for analysis. γH2AX is an indicator of DSBs and is often used to identify senescent cells [25–27]. Treated myoblasts were stained for γH2AX and then sorted via flow cytometry to determine the percentage of positively stained cells (Fig. 3A). After 1 h of treatment, 56.7% of BLEO cells were γH2AX-positive versus 0.52% of VEH cells (p < 0.01). At 3 h, the γH2AX percentage significantly decreased to 32.8% for BLEO cells (p < 0.01) and remained elevated for the subsequent time points.

Fig. 3.

The acute molecular signature of damage-induced senescence. Myoblasts were treated with VEH or BLEO (14 μM) for 1, 3, 6, or 12 h and collected immediately following treatment. A Flow cytometry was utilized to determine the percentage of cells that stain positive for γH2AX, a marker of DNA damage. Relative mRNA expression of B Cdkn2c, C Trp53, and D Cdkn1a. E Representative western blots of p18INK4C, p53, p21CIP1, and γH2AX. + denotes bleomycin treatment, and – denotes vehicle treatment. Ponceau S staining is shown below to confirm equal loading across all samples. Graphical quantification of F p18INK4C, G p53, H p21CIP1, and I γH2AX protein content. J Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of vehicle- and bleomycin-treated myotubes stained for p53 (green) and nuclei (DAPI; blue). K Graphical quantification of nuclear and cytosolic p53 protein levels. Relative mRNA expression of L Mdm2, M Rnase4, N Ang, and O Nfkb2. Protein and mRNA data are expressed as a fold-change relative to VEH. Data are means ± SD. * denotes a significant difference from VEH (p < 0.05). # denotes a significant difference from all other BLEO time points (p < 0.01)

We then evaluated genes directly implicated in cellular senescence and cell cycle regulation, namely, Cdkn2c (p18INK4C), Trp53 (p53), Cdkn1a (p21Cip1), and Cdkn2a (p16INK4a). In response to BLEO treatment, Cdkn2c mRNA expression was unchanged from VEH at 1 h, but was significantly greater at 3, 6, and 12 h (1.6-, 2.2-, and 1.8-fold greater, respectively; all time points p < 0.01; Fig. 3B). Trp53 mRNA expression did not significantly differ between treatment conditions at any treatment duration (Fig. 3C). Cdkn1a mRNA expression was comparable across conditions at 1 h, but was significantly elevated in BLEO groups at 3, 6, and 12 h (5.7-, 3.5-, and 4.6-fold greater than VEH, respectively; all time points p < 0.01; Fig. 3D). Cdkn2a, a very common gene associated with cellular senescence, could not be amplified in any samples despite the use of two different gene probes. This finding was surprising, and we wanted to further evaluate if the p16INK4A gene was present in the transcriptomic profile of C2C12 myoblasts. We assessed six RNA-sequencing and microarray datasets of C2C12 myoblasts and compared the expression of Cdkn2a, Cdkn1a, Cdkn2c, and Trp53 (Table 1). No Cdkn2a transcripts were detected in 11 control samples analyzed by RNA-sequencing, whereas the p21CIP1, p18INK4C, and p53 genes had anywhere between 8.7 and 156.7 fragments per kilobase million (FPKM). Microarray analysis revealed similar findings, with Cdkn2a displaying a very low Δ signal (defined as the difference between gene median signal and median background signal) compared to the other evaluated genes. Importantly, the p16INK4A gene signal was not significantly greater than the background signal in any of the 10 control samples analyzed. These findings strongly suggest that the Cdkn2a gene is not expressed within C2C12 myoblasts.

Table 1.

RNA-seq and microarray gene expression data

| Gene | RNA-sequencing | Microarray | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | FPKMa | GEO | Sample Size | Δ Signalb | Greater than BGc | GEO | |

| Cdkn2a (p16INK4A) | 11 | 0–0 | 10 | − 2–56 | No (n = 10) | ||

| Cdkn1a (p21CIP1) | 78.8–156.7 | 5860–14305 | Yes (n = 10) | ||||

| Cdkn2c (p18INK4C) | 8.7–22.6 | 306–4886 | Yes (n = 10) | ||||

| Trp53 (p53) | 34.6–62.8 | 188–5437 | Yes (n = 10) | ||||

aFragments per kilobase million (FPKM) of a gene as determined by RNA-sequencing. Only control groups were analyzed; data are expressed from minimum to maximum

bDifference between the median gene signal and median background signal as determined by Agilent microarray profiling. Only control groups were analyzed; data are expressed from minimum to maximum

cIf the gene signal from microarray analysis was significantly greater than the detected background signal

Data were accessed from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession viewer. References, where applicable, are as follows: [28–32]

To investigate if the gene expression modifications induced by BLEO were translated to the protein level, we examined these molecular markers via western blotting (Fig. 3E). Despite elevated Cdkn2c mRNA expression, p18INK4C protein content did not significantly increase between conditions or treatment durations (Fig. 3F). P53 protein content also remained unchanged in all groups (Fig. 3G). P21CIP1 protein content was significantly greater at 1, 3, 6, and 12 h treatment durations in BLEO-treated myoblasts (1.3-, 1.6-, 1.6- and 1.3-fold greater than VEH, respectively; all time points p < 0.01; Fig. 3H). Similarly, γH2AX protein content was elevated in BLEO groups at every time point (2.3-, 2.4-, 2.4-, and 1.9-fold greater than VEH, respectively; all time points p < 0.01; Fig. 3I). P16INK4A western blotting failed to reveal any quantifiable bands for analysis.

P53-independent activation of p21 may be driven by SASE genes and NF-κB

The elevation of both p21 mRNA and protein despite no change in p53 levels was an unexpected finding. We first sought to examine p53 cellular location via immunocytochemistry to identify if p53 nuclear translocation is occurring. Indeed, a small yet significant increase in nuclear p53 content was observed, which could partially account for the elevation in p21 (p < 0.05; Fig. 3J, K). Another possibility is that alternative signalling pathways are responsible for the p53-independent activation of p21. Previous literature has described a family of genes known as senescence-associated super-enhancers (SASE) that suppress p53 activity in senescent cells to protect against apoptosis following DNA damage [33]. We investigated the expression of three SASE genes during BLEO treatment and observed a significant elevation in Mdm2 and Rnase4 mRNA, but not Ang mRNA, at various timepoints (p < 0.05; Fig. 3L-N). Additionally, it has been recently discovered that DNA damage in myeloid leukemia cells can stimulate p21 expression via NF-κB activation, independent of p53 [34]. In our model, C2C12 myoblasts upregulated NF-κB mRNA expression during senescence induction, suggesting that this alternative signalling pathway could be responsible for the elevated p21 levels (p < 0.05; Fig. 3O).

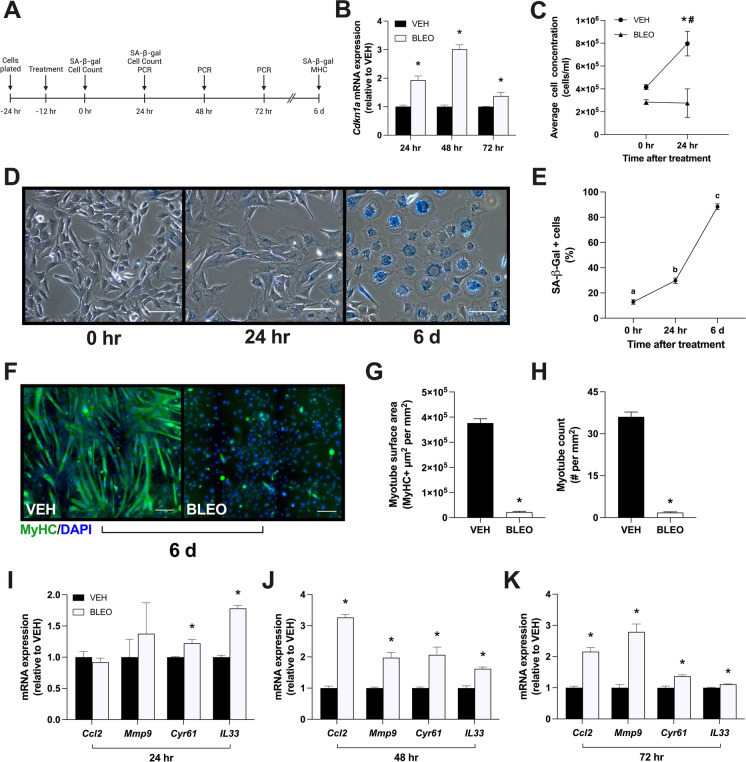

P21 expression remains elevated beyond senescence induction

P21CIP1 is believed to transiently increase in response to DNA damage and then decrease upon senescence induction [10, 35]. To test this, myoblasts were incubated with VEH or BLEO (14 μM) for 12 h and then collected after 24, 48, or 72 h in fresh GM (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, Cdkn1a mRNA expression remained elevated in the senescent myoblasts for 72 h after the bleomycin stimulus was removed (p < 0.05; Fig. 4B). The continued expression of p21CIP1 after 24 h was accompanied with no change in average cell concentration, whereas control myoblasts had significantly proliferated after 24 h and had 2.9 times more cells than the BLEO group (p < 0.01; Fig. 4C). To ensure the decrease in proliferation was not due to apoptosis, cell viability was evaluated at 24 h and was unchanged in senescent myoblasts compared to the 0 h or VEH groups (data not shown). These results suggest that DNA damage-induced senescence is maintained for several days after the damaging stimulus has been removed, which may be due to the sustained expression of p21CIP1.

Fig. 4.

Senescent myoblast characteristics at several time points post-treatment. A Experimental design of vehicle or bleomycin (14 μM)-treated myoblasts. All groups were treated for 12 h and then collected immediately, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, or 6 days post-treatment. Growth media (24–72 h groups) or differentiation media (6-day groups) replaced treated media after the 12-h incubation period. B Relative mRNA expression of Cdkn1a 24, 48, and 72 h after treatment. C Average cell concentration at 0 and 24 h after treatment; data expressed as total cells per millilitre of media. D Representative phase contrast microscopy images of SA-β-Gal-positive myoblasts at 0 h, 24 h, and 6 days following bleomycin treatment. E Graphical quantification of SA-β-Gal-positive cells at various time points after bleomycin treatment. Following 6 days of DM incubation, samples were stained for myosin heavy chain (MyHC; green) and nuclei (DAPI; blue) to determine differentiation status. F Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of vehicle-treated myotubes and bleomycin-treated myoblasts. G Graphical quantification of myotube surface area was determined by MyHC + area (μm2), expressed relative to image area (mm2). H Myotube count was quantified as the total number of MyHC + myotubes containing 2 + nuclei, expressed relative to image area (mm2). Relative mRNA expression of Ccl2, Mmp9, Cyr61, and Il33 measured I 24 h, J 48 h, and K 72 h after treatment. Data are means ± SD. Means that do not share a letter are statistically different (p < 0.01). * denotes a significant difference from VEH (p < 0.05). # denotes a significant difference from the 0-h post-treatment timepoint (p < 0.01)

Greater SA-β-gal staining several days post-treatment

Based on the substantial genetic and protein response observed as early as 1 h following treatment, we sought to investigate why SA-β-gal staining was only detected in approximately 28% of myoblasts treated with 14 μM BLEO (Fig. 1C). C2C12 myoblasts were incubated with VEH or BLEO (14 μM) for 12 h and then differentiated for 6 days. Cells were stained for β-gal immediately post-treatment (0 h), after 24 h in fresh GM (24 h), and after 6 days of DM (6 d). 12.8% of BLEO-treated cells were β-gal-positive at 0 h, which significantly increased to 29.8% of cells by 24 h (p < 0.01; Fig. 4D, E). After 6 days in DM, there was a noticeable absence of myotubes, and 88.4% of cells were positive for β-gal (p < 0.01). Curiously, β-gal staining intensity was also 57.3% and 55.4% greater compared to the 0 h and 24 h time points, respectively (p < 0.01; data not shown).

Senescent myoblasts exhibit full impairment of differentiation

Given the potential implications of cellular senescence on satellite cell dynamics, we evaluated the impact of damage-induced senescence on myoblast differentiation. C2C12 myoblasts were treated with VEH or BLEO (14 μM) for 12 h before being switched to DM for 6 days. Chamber slides were then stained for MyHC to label terminally differentiated myotubes and DAPI to label nuclei (Fig. 4F). Myotube surface area was significantly reduced in BLEO-treated cells (2.2 × 104 μm2/mm2) compared to VEH-treated cells (3.8 × 105 μm2/mm2; p < 0.01; Fig. 4G). Myotube count, defined as any MyHC + myotube containing 2 + merged myonuclei, was also significantly lower in senescent cells (1.8 myotubes/mm2) compared to control cells (36.0 myotubes/mm2; p < 0.01; Fig. 4H). These findings demonstrate that damage-induced cellular senescence is capable of completely preventing myoblast differentiation and myotube formation.

Bleomycin treatment produces SASP characteristics in senescent myoblasts

Senescent cells are continuously releasing proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and other damage-inducing proteins as part of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Therefore, we sought to investigate if our model of senescence could produce a genetic SASP signature. The SASP markers CCL2, MMP9, Cyr61, and IL-33 were examined after consulting the recently published SenMayo gene set and a senescent atlas of skeletal muscle [36, 37]. Twenty-four hours after concluding treatment, only Cyr61 and Il33 mRNA was significantly elevated in senescent myoblasts (p < 0.05; Fig. 4I). However, by 48- and 72-h post-treatment, Ccl2, Mmp9, Cyr61, and Il33 mRNA expression was significantly greater in BLEO-treated cells (p < 0.05; Fig. 4J, K). These observations provide evidence for the existence of the SASP in this model of DNA damage-induced senescence.

Discussion

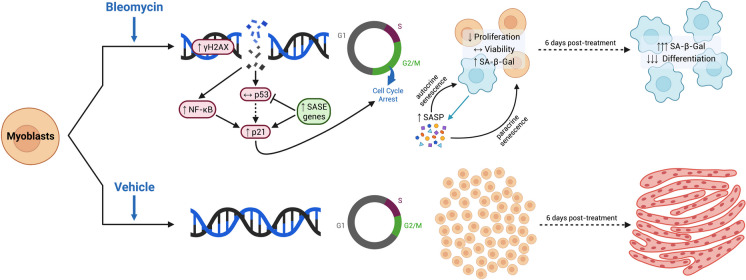

Satellite cells are quiescent until a stimulus, such as muscle damage, triggers their entry into the cell cycle to promote the repair process. Recent evidence implicates cellular senescence as a potential contributor to the decline in human skeletal muscle health during advanced age [38]. However, the investigation of senescence in skeletal muscle is relatively new, and there is a need for valid and reproducible models of SC senescence. In this study, we established a novel, in vitro, model of senescence using C2C12 myoblasts and evaluated how several senescence-related markers changed across various treatment and sampling times. Based on our observations, we propose the following biomarker timeline of senescence induction after extensive DNA damage in myoblasts (Fig. 5). When a stimulus triggers significant genomic damage, γH2AX expression is immediately elevated marking the presence of DSBs. Significant DNA damage can activate several signaling pathways, including NF-κB, which is capable of stimulating p21 expression independent of p53 [34]. There are also protective SASE genes that activate in response to DNA damage to stimulate p21 activity and suppress p53-mediated apoptosis [33]. The elevated p21 expression initiates a sequestration of the myoblasts at the G2 checkpoint of the cell cycle and renders them senescent. In certain conditions, such as the absence of the Cdkn2a gene, p21 expression can persist to maintain senescence. At this point, there is an abrupt halt of proliferation, and a small percentage of cells begin to express SA-β-gal. Meanwhile, senescent cells are continuously releasing SASP factors that reinforce the senescence signal from the host cell, but also act on adjacent cells that may not yet be senescent [39, 40]. As a result, more cells begin to stain positive for SA-β-gal 24 h after the damaging stimulus has been removed, and six days later, nearly 90% of all cells are positive. The final result is a complete impairment of myotube formation and an almost homogenous senescent myoblast population.

Fig. 5.

A proposed timeline for damage-induced senescence of skeletal muscle cells. Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic agent that can induce double-stranded DNA breaks and was utilized to create a model of damage-induced senescence. Treatment with bleomycin results in significant DNA damage as early as 1 h into the incubation period, as determined by γH2AX. The DNA damage response elevates p21CIP1 gene expression and protein content during the damaging stimulus in a p53-independent manner. One possible explanation for the elevated p21 levels is the increased NF-κB activity in response to DNA damage, which has been shown to activate p21 separately from p53. Another potential mechanism is the activation of senescence-associated super enhancer (SASE) genes, which act to inhibit p53 activity while maintaining elevated p21 levels to protect against damage-induced apoptosis. As a result of the elevated p21 activity, almost 40% of bleomycin-treated myoblasts are sequestered in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle and become senescent. This was accompanied by a significant decrease in cell proliferation but not cell viability, suggesting cells were senescent and not apoptotic. During this time, senescent myoblasts are releasing factors as part of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). These factors are capable of autocrine senescence which reinforces the damage-induced response within the secreting cell and paracrine senescence which promotes senescence within adjacent healthy cells. SA-β-Gal staining revealed approximately 13% of myoblasts were senescent immediately post-treatment, which increased to 30% after 24 h and 88% after 6 days in differentiation media. In comparison, vehicle-treated myoblasts had no impairments to their DNA, underwent significantly greater proliferation, and could differentiate into mature myotubes

We chose to utilize a damage-induced model of senescence because of the increase in ROS, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and DNA damage that acts on SC in advanced age [14, 41, 42]. The C2C12 cell line was selected because these myoblasts are capable of several dozen population doublings before any observable impact on proliferation or differentiation and because immortalized cells are inherently resistant to replicative senescence and thus provide a more rigorous proof-of-concept model of damage-induced senescence [43]. Bleomycin proved to be an effective inducer of cellular senescence in myoblasts, which is in line with previous work demonstrating that bleomycin treatment is capable of inducing senescence in lung epithelial cells in vivo and in vitro [17, 19, 44]. Bleomycin’s primary impact on cells is the initiation of single-stranded and DSBs, the latter of which was detected by γH2AX in our model. Single-stranded breaks have a greater chance of causing apoptosis due to the lower threshold for cell death and the rapid accumulation of p53 that occurs with this kind of DNA damage [45]. While we did not measure single-stranded breaks, our model had very limited apoptosis, so it is possible that most of the damage caused by bleomycin was due to DSBs rather than single-stranded DNA breaks. Therefore, our model of myoblast senescence is particularly valuable as DSBs are known to accumulate with aging and can cause senescence in SC [46]. Prior work has found that up to 15% of SC progeny become senescent after irradiation-induced DSBs, despite having highly efficient DNA repair mechanisms in place [46]. It is possible that DNA damage in the form of DSBs could contribute to aging-related SC senescence. However, this notion is challenged by previous findings showing that SC isolated from aged mouse muscle do not accumulate more DSBs than their young counterparts [47]. Further investigation of the relationship between DSBs and senescence in SC is needed.

Growth arrest and proliferation status are two indicators that should be evaluated when characterizing cellular senescence. Proliferation was reduced and arrest in the G2/M phase occurred in bleomycin-treated myoblasts. Cells that are not actively proliferating but maintain proliferation potential, such as quiescent SC, reside in a reversible phase of the cell cycle known as G0. Historically, senescent cells were believed to be arrested at the G1 and G0 checkpoints throughout the cell cycle; however, more recent findings suggest that senescence can occur in the G2 phase as well [48–50]. Cells that are arrested at the G0/G1 phase have most likely undergone replicative senescence, although there are reports of elevated G2 arrest in replicative-senescent cells [51, 52]. Consistent with our results, DNA damage-induced senescence is commonly associated with G2 phase arrest [49]. Cell cycle arrest at a G2 checkpoint is reliant on p53/p21 signalling, and senescent cells that overexpress p21CIP1 are preferentially arrested in G2 [49, 53]. Our finding that senescent myoblasts are arrested at G2 is complimented by elevated Cdkn1a gene expression and p21 protein content in bleomycin-treated cells (Figs. 2C and 3D, H).

P21 activation upon DNA damage is believed to be transient and decreases once senescence is initiated, ultimately being replaced by the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p16INK4A [35]. Its brief appearance is important for the damage-induced senescence response, but it cannot reliably label senescent cells due to its transient expression [16]. Curiously, our findings suggest the maintenance of p21 expression well beyond the initial damaging stimulus and subsequent senescence induction. One possible explanation is that p21 activity is maintained due to the absence of p16 in C2C12 myoblasts. Another possibility is that adjacent senescent cells secrete SASP factors that continuously initiate damage response signalling and thus p21 expression. It may be that p21 remains elevated when the initial senescence trigger involves extensive DNA damage and DSBs. Should this be true, then p21 could be used as a valid marker of DNA damage-based senescence. However, in vivo, SC in elderly muscles do indeed express p16 and would be exposed to stimuli that cause alternative forms of damage, such as impaired autophagy or mitochondrial function [54, 55]. Thus, it stands that p21 should not be utilized independently as a biomarker of senescence in human skeletal muscle, but instead used to characterize the molecular signature of senescence in conjunction with additional markers.

Because the activation of p21 is primarily mediated by p53, we then sought to evaluate the change in this tumour suppressor protein. To our surprise, neither mRNA expression nor protein content of p53 changed in senescent myoblasts. While it is possible for p21 induction independent of p53, this typically occurs as a result of extrinsic stimuli such as transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) or serum deprivation, not DNA damage [56, 57]. Irradiation-induced G2 phase arrest is possible in p53-deficient cells, but this arrest cannot be maintained without functional p53 protein [58]. The earliest time point evaluated in our work was 1 h into treatment, and p53 activation is known to respond immediately following DNA damage. It is possible that p53 was transiently expressed in order to activate p21 expression prior to the 1-h time point [59]. It is also possible that the small increase in p53 nuclear translocation that we observed in senescent myoblasts could drive the increase in p21 activity. Another explanation could be the early upregulation of senescence-associated super-enhancer (SASE) genes in response to the damaging stimulus. Mdm2, Rnase4, and Ang SASEs act in senescent cells to suppress p53 activity and protect against p53-mediated apoptosis in response to DNA damage [33]. Bleomycin-treated myoblasts upregulated SASE genes during senescence induction, which would also explain why the senescent myoblasts were very resistant to apoptosis, and how they remained senescent in culture for 6 days after the initial damage. Alternatively, DNA damage can activate the NF-κB pathway via phosphorylation of NEMO, which has been found to elevate p21 expression independent of p53 in myeloid leukemia cells [34, 60]. It is possible that in response to bleomycin, the myoblasts activate p21 via NF-κB signaling instead of p53. Given that p53 mRNA and protein were not elevated at any time during bleomycin treatment, our results suggest that in certain conditions, DNA damage is capable of inducing p53-independent activation of p21, potentially through NF-κB signaling and the anti-apoptotic action of the SASE genes.

A curious observation from our work was that there was an increase in SA-β-gal-positive cells and staining intensity 6 days post-treatment relative to immediately and 24 h post-treatment. One possible explanation for the increase in β-gal + cells is that there was a delayed response to the damaging stimuli that required several days before most cells stained positive. Alternatively, the increased staining frequency could be due to the release of SASP factors from senescent cells that promoted autocrine senescence (to reinforce the senescent signal within the origin cell) and paracrine senescence (to induce damage and eventually senescence in adjacent healthy cells). Autocrine senescence would also explain the increase in SA-β-gal staining intensity observed at day 6. It is unlikely that the increase in staining intensity is due to microscopy discrepancies, as all the samples for this experiment were stained and imaged together. Rather, it seems that SA-β-gal staining may be inaccurate at labelling DNA damage-induced senescence or simply delayed in its reaction to senescence induction. The case for a delayed response is evident when considering that almost 40% of cells expressed γH2AX after 12 h of treatment (Fig. 3A), whereas only 13% of cells stained positive for SA-β-gal at the same time point (Fig. 4E). However, there is evidence that SA-β-gal staining can label non-senescent cells, such as in macrophages during M1 to M2 polarization and thus may be less accurate at labeling senescent cells during periods of transformation [26, 61]. Regardless, this finding strengthens the case for the use of multiple biomarkers when characterizing cellular senescence.

One observation from our work is that C2C12 myoblasts do not express Cdkn2a, the gene that codes for p16INK4A. We compared the results from our qPCR analysis to several RNA-sequencing and microarray datasets on C2C12 myoblasts and concluded that Cdkn2a was indeed not present within these cells. Prior work showed that p16-specific short hairpin RNA, which acts to suppress p16 expression, was able to immortalize human mammary epithelial cells and prevent senescence [62]. These newly immortalized, p16-deficient cells could proliferate indefinitely up to at least passage 24, whereas control cells became senescent as early as passage 9 [62]. While certain cell lines are immortal due to elevated telomerase activity, the C2C12 cell line is at comparable telomerase levels to that of freshly isolated SC [15, 63]. It was previously reported that the Ink4a locus is deleted in C2C12 myoblasts, which would explain why p16 gene expression was not detected in these cells [64]. These findings, in conjunction with the absence of p16 in our cells, leads us to hypothesize that the missing Cdkn2a gene is at least partially responsible for the immortalized nature of C2C12 myoblasts. Importantly, our results show senescence can be maintained in the absence of p16, which is required to sustain cellular senescence after p53/p21 signalling decreases and may be compensating with elevated p21 levels instead [65].

The findings in the current study describe a valid model of myoblast senescence and provide novel insight into the mechanisms governing cellular senescence in skeletal muscle. However, this study is not without limitations. As with all in vitro experimentation, there is undoubtedly a concern regarding the translation to in vivo muscle tissues, especially with a phenomenon as complex and diverse as cellular senescence. This is especially true after considering that C2C12 myoblasts are a polyploid cell line developed from a female mouse donor, which cannot perfectly exemplify human satellite cells in vivo. Furthermore, while bleomycin is a useful compound for producing this model of damage-induced senescence, it does not directly replicate the microenvironment that muscle stem cells would be subjected to during advanced age. Lastly, our examination of the SASP was limited to the mRNA expression within senescent myoblasts. Future studies should aim to investigate the composition of both senescent cells and the surrounding media following bleomycin treatment.

In summary, we have developed a valid and physiologically relevant model that provides a simple approach to studying cellular senescence in skeletal muscle cells. With this model, we discovered several novel observations, including the finding that p21 activity can be sustained beyond senescence induction in the absence of p16. We also observed an increase in SA-β-gal staining several days after an initial damaging stimulus, suggesting that bleomycin-treated myoblasts may be releasing SASP factors that can induce senescence in adjacent cells over time. Additionally, we discovered that the commonly used C2C12 cell line does not express the Cdkn2a gene. Notably, we demonstrate a discrepancy between several commonly used senescence biomarkers, confirming the need for a multi-marker approach when identifying and classifying cellular senescence. Although our work was conducted in cultured myoblasts, this conclusion also applies to, in vivo, animal and human muscle research where a significantly more complex microenvironment surrounding SC can make investigating senescence quite challenging.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Todd Prior and Linda May (McMaster University) for their technical assistance during laboratory analysis. Figure graphics were created with BioRender.com.

Author contribution

MK, SJ, and GP were involved in the conception and design of the study. MK conducted data acquisition and analysis. MK, SJ, and GP were involved in data interpretation. MK drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Funding

M.K. was supported in part by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada post-graduate scholarship. G.P was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Discovery award.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Peake J, Gatta PD, Cameron-Smith D. Aging and its effects on inflammation in skeletal muscle at rest and following exercise-induced muscle injury. Am J Physiol-Regul, Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1485–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00467.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renault V, Thornell LE, Eriksson PO, Butler-Browne G, Mouly V. Regenerative potential of human skeletal muscle during aging. Aging Cell. 2002;1:132–139. doi: 10.1046/J.1474-9728.2002.00017.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brack AS, Bildsoe H, Hughes SM. Evidence that satellite cell decrement contributes to preferential decline in nuclear number from large fibres during murine age-related muscle atrophy. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4813–4821. doi: 10.1242/JCS.02602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verdijk LB, Koopman R, Schaart G, Meijer K, Savelberg HHCM, van Loon LJC. Satellite cell content is specifically reduced in type II skeletal muscle fibers in the elderly. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E151–E157. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00278.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKay BR, Ogborn DI, Bellamy LM, Tarnopolsky MA, Parise G. Myostatin is associated with age-related human muscle stem cell dysfunction. FASEB J. 2012;26:2509–2521. doi: 10.1096/FJ.11-198663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snijders T, Parise G. Role of muscle stem cells in sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2017;20:186–190. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keefe AC, Lawson JA, Flygare SD, Fox ZD, Colasanto MP, Mathew SJ, et al. Muscle stem cells contribute to myofibres in sedentary adult mice. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7087. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fry CS, Lee JD, Mula J, Kirby TJ, Jackson JR, Liu F, et al. Inducible depletion of satellite cells in adult, sedentary mice impairs muscle regenerative capacity without affecting sarcopenia. Nat Med. 2015;21:76–80. doi: 10.1038/nm.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campisi J, D’Adda Di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:729–40. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robles SJ, Adami GR. Agents that cause DNA double strand breaks lead to p16INK4a enrichment and the premature senescence of normal fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1998;16:1113–1123. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aravinthan A. Cellular senescence: a hitchhiker’s guide. Hum Cell. 2015;28:51–64. doi: 10.1007/s13577-015-0110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez-Segura A, Nehme J, Demaria M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:436–453. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tai H, Wang Z, Gong H, Han X, Zhou J, Wang X, et al. Autophagy impairment with lysosomal and mitochondrial dysfunction is an important characteristic of oxidative stress-induced senescence. Autophagy. 2017;13:99–113. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1247143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sousa-Victor P, Gutarra S, García-Prat L, Rodriguez-Ubreva J, Ortet L, Ruiz-Bonilla V, et al. Geriatric muscle stem cells switch reversible quiescence into senescence. Nature. 2014;506:316–321. doi: 10.1038/nature13013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connor MS, Carlson ME, Conboy IM. Differentiation rather than aging of muscle stem cells abolishes their telomerase activity. Biotechnol Prog. 2009;25:1130–1137. doi: 10.1002/BTPR.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharpless NE, Sherr CJ. Forging a signature of in vivo senescence. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:397–408. doi: 10.1038/nrc3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoshiba K, Tsuji T, Nagai A. Bleomycin induces cellular senescence in alveolar epithelial cells. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:436–443. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00011903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hecht SM. Bleomycin: new perspectives on the mechanism of action. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:158–168. doi: 10.1021/np990549f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chow MS, Liu L V, Solomon EI. Further insights into the mechanism of the reaction of activated bleomycin with DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13241–510.1073/pnas.0806378105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9363–710.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Loveland BE, Johns TG, Mackay IR, Vaillant F, Wang ZX, Hertzog PJ. Validation of the MTT dye assay for enumeration of cells in proliferative and antiproliferative assays. Biochem Int. 1992;27:501–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernadotte A, Mikhelson VM, Spivak IM. Markers of cellular senescence. Telomere shortening as a marker of cellular senescence. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8:3. doi: 10.18632/AGING.100871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/METH.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blagosklonny MV. Cell cycle arrest is not yet senescence, which is not just cell cycle arrest: terminology for TOR-driven aging. Aging. 2012;4:159–65. doi: 10.18632/AGING.100443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mah L-J, El-Osta A, Karagiannis TC. GammaH2AX as a molecular marker of aging and disease. Epigenetics. 2010;5:129–136. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.2.11080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dungan CM, Peck BD, Walton RG, Huang Z, Bamman MM, Kern PA, et al. In vivo analysis of γH2AX+ cells in skeletal muscle from aged and obese humans. FASEB J. 2020;34:7018–7035. doi: 10.1096/fj.202000111RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, Jurk D, Maddick M, Nelson G, Martin-Ruiz C, Von Zglinicki T. DNA damage response and cellular senescence in tissues of aging mice. Aging Cell. 2009;8:311–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chemello F, Grespi F, Zulian A, Cancellara P, Hebert-Chatelain E, Martini P, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of single isolated myofibers identifies miR-27a-3p and miR-142-3p as regulators of metabolism in skeletal muscle. Cell Rep. 2019;26:3784–3797.e8. doi: 10.1016/J.CELREP.2019.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki K, Matsumoto M, Katoh Y, Liu L, Ochiai K, Aizawa Y, et al. Bach1 promotes muscle regeneration through repressing Smad-mediated inhibition of myoblast differentiation. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0236781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, Zhu X, Jia X, Hou W, Zhou G, Ma Z, et al. Phosphorylation of Msx1 promotes cell proliferation through the Fgf9/18-MAPK signaling pathway during embryonic limb development. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:11452–11467. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKAA905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He K, Wu G, Li W-X, Guan D, Lv W, Gong M, et al. A transcriptomic study of myogenic differentiation under the overexpression of PPARγ by RNA-Seq. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15308. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14275-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyu P, Jiang H. RNA-sequencing reveals upregulation and a beneficial role of autophagy in myoblast differentiation and fusion. Cells. 2022;11:3549. doi: 10.3390/cells11223549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sturmlechner I, Sine CC, Jeganathan KB, Zhang C, Fierro Velasco RO, Baker DJ, et al. Senescent cells limit p53 activity via multiple mechanisms to remain viable. Nat Commun. 2022;13:3722. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31239-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolae CM, O’Connor MJ, Constantin D, Moldovan G-L. NFκB regulates p21 expression and controls DNA damage-induced leukemic differentiation. Oncogene. 2018;37:3647–3656. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein GH, Drullinger LF, Soulard A, Dulić V. Differential roles for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p16 in the mechanisms of senescence and differentiation in human fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2109–2117. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.3.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saul D, Kosinsky RL, Atkinson EJ, Doolittle ML, Zhang X, LeBrasseur NK, et al. A new gene set identifies senescent cells and predicts senescence-associated pathways across tissues. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4827. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moiseeva V, Cisneros A, Sica V, Deryagin O, Lai Y, Jung S, et al. Senescence atlas reveals an aged-like inflamed niche that blunts muscle regeneration. Nature. 2023;613:169–178. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05535-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X, Habiballa L, Aversa Z, Ng YE, Sakamoto AE, Englund DA, et al. Characterization of cellular senescence in aging skeletal muscle. Nat Aging. 2022;2:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s43587-022-00250-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiche A, le Roux I, von Joest M, Sakai H, Aguín SB, Cazin C, et al. Injury-induced senescence enables in vivo reprogramming in skeletal muscle. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:407–414.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Muñoz DP, Goldstein J, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e301. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PBIO.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.García-Prat L, Martínez-Vicente M, Perdiguero E, Ortet L, Rodríguez-Ubreva J, Rebollo E, et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature. 2016;529:37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature16187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tidball JG. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00454.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharples AP, Al-Shanti N, Lewis MP, Stewart CE. Reduction of myoblast differentiation following multiple population doublings in mouse C2C12 cells: a model to investigate ageing? J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:3773–3785. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aoshiba K, Tsuji T, Kameyama S, Itoh M, Semba S, Yamaguchi K, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotype in a mouse model of bleomycin-induced lung injury. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2013;65:1053–1062. doi: 10.1016/J.ETP.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma A, Dai X. The relationship between DNA single-stranded damage response and double-stranded damage response. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:73. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1403681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.VahidiFerdousi L, Rocheteau P, Chayot R, Montagne B, Chaker Z, Flamant P, et al. More efficient repair of DNA double-strand breaks in skeletal muscle stem cells compared to their committed progeny. Stem Cell Res. 2014;13:492–507. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cousin W, Ho ML, Desai R, Tham A, Chen RY, Kung S, et al. Regenerative capacity of old muscle stem cells declines without significant accumulation of DNA damage. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63528. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0063528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanishevsky R, Mendelsohn ML, Mayall BH, Cristofalo VJ. Proliferative capacity and DNA content of aging human diploid cells in culture: a cytophotometric and autoradiographic analysis. J Cell Physiol. 1974;84:165–170. doi: 10.1002/JCP.1040840202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gire V, Dulić V. Senescence from G2 arrest, revisited. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:297–304. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2014.1000134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumari R, Jat P. Mechanisms of cellular senescence: cell cycle arrest and senescence associated secretory phenotype. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:485. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.645593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wagner M, Hampel B, Bernhard D, Hala M, Zwerschke W, Jansen-Dürr P. Replicative senescence of human endothelial cells in vitro involves G1 arrest, polyploidization and senescence-associated apoptosis. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36:1327–1347. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(01)00105-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mao Z, Ke Z, Gorbunova V, Seluanov A. Replicatively senescent cells are arrested in G1 and G2 phases. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:431. doi: 10.18632/AGING.100467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shtutman M, Chang BD, Schools GP, Broude EV. Cellular model of p21-induced senescence. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1534:31. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6670-7_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.García-Prat L, Muñoz-Cánoves P, Martinez-Vicente M. Dysfunctional autophagy is a driver of muscle stem cell functional decline with aging. Autophagy. 2016;12:612–613. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1143211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Korolchuk VI, Miwa S, Carroll B, von Zglinicki T. Mitochondria in cell senescence: is mitophagy the weakest link? EBioMedicine. 2017;21:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Datto MB, Li Y, Panus JF, Howe DJ, Xiong Y, Wang XF. Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:5545–9.10.1073/PNAS.92.12.5545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Macleod KF, Sherry N, Hannon G, Beach D, Tokino T, Kinzler K, et al. p53-dependent and independent expression of p21 during cell growth, differentiation, and DNA damage. Genes Dev 1995;9. 10.1101/gad.9.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Bunz F, Dutriaux A, Lengauer C, Waldman T, Zhou S, Brown JP, et al. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science. 1979;1998(282):1497–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lakin ND, Jackson SP. Regulation of p53 in response to DNA damage. Oncogene. 1999;18:7644–7655. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang TT, Wuerzberger-Davis SM, Wu ZH, Miyamoto S. Sequential modification of NEMO/IKKγ by SUMO-1 and ubiquitin mediates NF-κB activation by genotoxic stress. Cell. 2003;115:565–576. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00895-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hall BM, Balan V, Gleiberman AS, Strom E, Krasnov P, Virtuoso LP, et al. p16(Ink4a) and senescence-associated β-galactosidase can be induced in macrophages as part of a reversible response to physiological stimuli. Aging (Albany NY) 2017;9:1867. doi: 10.18632/AGING.101268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haga K, Ohno SI, Yugawa T, Narisawa-Saito M, Fujita M, Sakamoto M, et al. Efficient immortalization of primary human cells by p16INK4a-specific short hairpin RNA or Bmi-1, combined with introduction of hTERT. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:147–154. doi: 10.1111/J.1349-7006.2006.00373.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holt SE, Wright WE, Shay JW. Regulation of telomerase activity in immortal cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2932–2939. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.6.2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pajcini KV, Corbel SY, Sage J, Pomerantz JH, Blau HM. Transient inactivation of Rb and ARF yields regenerative cells from postmitotic mammalian muscle. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:198–213. doi: 10.1016/J.STEM.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.te Poele RH, Okorokov AL, Jardine L, Cummings J, Joel SP. DNA damage is able to induce senescence in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1876–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.