ABSTRACT

Background

25-hydroxyvitamin D can undergo C-3 epimerization to produce 3-epi-25(OH)D3. 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels decline in chronic kidney disease (CKD), but its role in regulating the cardiovascular system is unknown. Herein, we examined the relationship between 3-epi-25(OH)D3, and cardiovascular functional and structural endpoints in patients with CKD.

Methods

We examined n = 165 patients with advanced CKD from the Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Renal Failure and After Kidney Transplantation (CAPER) study cohort, including those who underwent kidney transplant (KTR, n = 76) and waitlisted patients who did not (NTWC, n = 89). All patients underwent cardiopulmonary exercise testing and echocardiography at baseline, 2 months and 12 months. Serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 was analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

Results

Patients were stratified into quartiles of baseline 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (Q1: <0.4 ng/mL, n = 51; Q2: 0.4 ng/mL, n = 26; Q3: 0.5–0.7 ng/mL, n = 47; Q4: ≥0.8 ng/mL, n = 41). Patients in Q1 exhibited lower peak oxygen uptake [VO2Peak = 18.4 (16.2–20.8) mL/min/kg] compared with Q4 [20.8 (18.6–23.2) mL/min/kg; P = .009]. Linear mixed regression model showed that 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels increased in KTR [from 0.47 (0.30) ng/mL to 0.90 (0.45) ng/mL] and declined in NTWC [from 0.61 (0.32) ng/mL to 0.45 (0.29) ng/mL; P < .001]. Serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 was associated with VO2Peak longitudinally in both groups [KTR: β (standard error) = 2.53 (0.56), P < .001; NTWC: 2.73 (0.70), P < .001], but was not with left ventricular mass or arterial stiffness. Non-epimeric 25(OH)D3, 24,25(OH)2D3 and the 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio were not associated with any cardiovascular outcome (all P > .05).

Conclusions

Changes in 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels may regulate cardiovascular functional capacity in patients with advanced CKD.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, CPET, echocardiography, epimeric vitamin D, kidney transplantation

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What was known:

Epimeric vitamin D [3-epi-25(OH)D3] is formed when 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH)D3] undergoes a change in the orientation of the C-3 hydroxy group from β to α.

3-epi-25(OH)D3 may comprise more than half of total 25(OH)D concentrations and therefore could significantly influence the end organ effect and clinical interpretation of vitamin D status.

3-epi-25(OH)D3 serum levels decline as chronic kidney disease (CKD) progresses and are positively correlated with skeletal muscle strength, muscle mass and exercise capacity.

This study adds:

Low (<0.4 ng/mL) serum levels of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 in patients with advanced CKD were associated with significantly impaired cardiovascular functional capacity assessed via peak oxygen consumption (VO2Peak).

Serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels increased following kidney transplantation and declined in patients who did not receive a transplant at 12 months, and these changes were significantly associated with longitudinal VO2Peak in both groups.

Serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels were not associated with left ventricular mass index or arterial stiffness.

Potential impact:

The association between levels of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 and cardiovascular functional capacity reported in the present study, along with its resistance to inactivation and low calcemic effects, assign potential therapeutic interest for epimeric vitamin D supplementation as a treatment for cardiovascular disease in CKD.

INTRODUCTION

Epimeric vitamin D [3-epi-25(OH)D3] is formed when 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH)D3] undergoes a change in the orientation of the C-3 hydroxy group from β to α in what is known as the C-3 epimerization pathway [1]. A recent study found that 3-epi-25(OH)D3 may comprise up to 54.1% of total 25(OH)D concentrations [2], and therefore could significantly influence the end organ effect and clinical interpretation of vitamin D status. Despite this, the vast majority of studies on vitamin D in nephrology have focused on total levels of 25(OH)D without accounting for 3-epi-25(OH)D3. Moreover, recent data shows that 3-epi-25(OH)D3 serum levels decline as chronic kidney disease (CKD) progresses [3], and are positively correlated with skeletal muscle strength, muscle mass and performance in the incremental shuttle walk test—a field test designed to estimate cardiovascular functional capacity—in patients with CKD not on dialysis [4]. These findings suggest that 3-epi-25(OH)D3 may play a biologically significant role in regulating musculoskeletal and, potentially, cardiovascular health in patients with CKD.

Several studies in patients with CKD have demonstrated the tight link between vitamin D deficiency and heightened risk of cardiovascular events and mortality [5–7]. This is significant because of the extraordinarily high burden of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with CKD [8]. Experimental studies have revealed several “non-classical” benefits of vitamin D on the cardiovascular system [9], including downregulation of hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes [10], atherosclerotic plaque regression [11] and protection against vascular calcification [12]. However, randomized clinical trials have failed to demonstrate reversal of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy or improvements in systolic or diastolic function with non-epimeric vitamin D compounds such as paricalcitol [13, 14]. Although there are several potential reasons why these trials failed to show a treatment benefit, such as small sample size [13] and treatment duration that was too short to modify LV hypertrophy and dysfunction [14], it is possible that paricalcitol treatment accelerated the catabolism of 1α,25(OH)2D and 25(OH)D, which can paradoxically potentiate vitamin D deficiency [15]. Moreover, a common complication associated with paricalcitol treatment in these randomized trials was hypercalcemia [13, 14]. Interestingly, 3-epi-1α,25(OH)2D3 was found to be almost equipotent to 1α,25(OH)2D3 in suppressing parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion, but without the calcemic effects of the non-epimeric vitamin D [16, 17]. In addition, the rate of side-chain oxidation of 3-epi-1α,25(OH)2D3 leading to its final inactivation was shown to be 3-fold lower than non-epimeric 1α,25(OH)2D3 [18]. These findings indicate that 3-epi-1α,25(OH)2D3 may have a better pharmacokinetic profile than 1α,25(OH)2D3. However, very little is known regarding the factors that regulate 3-epi-25(OH)D3 production. The enzyme involved in the epimerization of 25(OH)D3, as well as the exact conditions favoring epimerization of 25(OH)D, remain to be determined. Significantly, no studies to-date have examined the relationship between epimers of vitamin D and cardiovascular functional and structural health in patients with CKD. Defining this relationship is an important step towards investigating the role and potential therapeutic utility of C-3 epimeric forms of vitamin D.

Cardiovascular functional decline in patients with CKD is a result of impairment of an integrated system composed of the heart [19], lungs [20], vasculature [21] and skeletal muscle [22]. Together, functional decrements in each of these organs contribute to severe impairment in cardiovascular functional capacity [23], which can be quantified through the assessment of oxygen uptake at peak exercise (VO2Peak) using state-of-the-art cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET). VO2Peak is directly related to cardiac output and skeletal muscle oxygen uptake at peak exercise [24]. Importantly, it has been shown to be a strong predictor of survival in patients with advanced CKD [25] and has been recognized as a ‘vital sign’ for its strong prognostic value by the American Heart Association [26]. Our recently published Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Renal Failure and After Kidney Transplantation (CAPER) study [27] was the first prospective, longitudinal cohort study to assess cardiovascular functional changes using CPET in parallel with resting transthoracic echocardiography before and after kidney transplantation. This cohort provides an ideal opportunity to comprehensively assess both cardiovascular function and structure due to the integrated measures provided. In this study, we hypothesized that 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels are associated with VO2Peak and cardiovascular structural endpoints in patients with advanced CKD before and after kidney transplantation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and cohorts

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from the recently published CAPER study [27]. This prospective, nonrandomized, three-arm study included a total of 253 participants. In the present study, 165 patients with advanced CKD stage 5 were included from two groups: patients who underwent kidney transplant (KTR group, n = 76) and patients on the kidney transplant waitlist who did not undergo kidney transplant (NTWC group, n = 89). Inclusion criteria consisted of patients who were 18 years or older and either waitlisted or scheduled for kidney transplantation. For the KTR group, participants were enrolled within 4 weeks before kidney transplant. Patients were assessed at baseline (BL) and followed up longitudinally at 2 month and 1 year post-transplantation.

All patients on hemodialysis were on thrice-weekly conventional hemodialysis and those on peritoneal dialysis were receiving either automated peritoneal dialysis with nightly five cycles of exchanges or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis with four exchanges over 24 h. All patients were recruited from the same center at the University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire National Health Service Trust, Coventry, UK as previously described [27]. Patients were aged 18 years and older. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Black Country Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent.

Study endpoints

Our primary endpoint was BL VO2Peak (in mL/min/kg) assessed via CPET. The secondary endpoints included VO2AT, the relationship between minute ventilation and carbon dioxide production (VE/VCO2 slope), hemodynamic measures [peak heart rate (HRpeak) and O2 pulse], peak workload, cardiac structural indices [LV mass index (LVMI) and LV ejection fraction (LVEF)] and arterial stiffness [augmentation index at 75 b.p.m. (AI75) and pulse wave velocity (PWV)]. VO2Peak and VO2AT were normalized for body weight to facilitate intersubject comparisons.

CPET, echocardiography and arterial applanation assessments

Participants underwent CPET and echocardiography at BL, 2 months and 12 months. For dialysis-dependent participants, CPET was performed at least 12 h after the last dialysis session on a non-dialysis day. Patients on PD had their fluid drained prior to CPET testing. CPET assessments were performed uniformly for all patients by an experienced exercise physiologist or physician who was blinded to the dialysis status of the study participant as previously described [28]. Participants performed maximum incremental exercise at individualized work rates using an electronically braked upright cycle ergometer (Ergoselect 100, Ergoline) and continuous 12-lead ECG recording. Continuous breath-by-breath gas exchange analysis (VIASYS, MasterScreen CPX®) was performed to assess ventilatory exercise responses. The CPET protocol consisted of a 3-min resting phase, followed by 3 min of cycling at 0 W, and then an incremental ramp test to symptom-limited volitional fatigue. The VO2 at the point of anerobic threshold (VO2AT) was determined by the V-slope method and confirmed with analyses of the ventilatory equivalents and end-tidal gas tension plots [29]. VO2Peak was measured as the highest VO2 achieved during the final 20-s averaging of peak exercise.

Patients also underwent two-dimensional Doppler and tissue Doppler transthoracic echocardiography using Vivid 7 (GE Healthcare) and assessment of vascular compliance (SphygmoCor, AtCor Medical Pty Ltd) as previously described [28].

Vitamin D metabolite analysis

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) were used to measure vitamin D metabolites. Serum 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3, 3-epi-25(OH)D3, 1α,25(OH)2D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 were extracted from human serum supplemented with deuterated internal standards [d3-25-OH-D2, d6-25-OH-D3, d3-3-epi-25-OH-D3, d6-1,25-(OH)2D3 and d6-24,25-(OH)2D3] using a combination of liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) and immunoextraction (IE), followed by derivatization with 4-[2-(6,7-dimethoxy-4-methyl-3-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinoxalinyl)ethyl]-1,2,4-triazoline-3,5-dione (DMEQ-TAD, Wynnewood, PA, USA), as described previously [30]. Samples were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis on Waters ACQUITY UPLC/Xevo TQ-S instruments (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) using both rapid and extended chromatographic systems.

Statistical analysis

The entire patient population was first stratified into quartiles of BL values of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 for analysis and then longitudinal changes were analyzed with patients grouped into KTR and NTWC. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize BL characteristic measures. Continuous variables were summarized by mean [standard deviation (SD)] if normally distributed, or median [interquartile range (IQR)] otherwise. Categorical variables were summarized by frequency (relative frequency in percentage). Comparisons between BL 3-epi-25(OH)D3 groups were made by analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-squared (χ2) tests for categorical variables. Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to assess associations between BL 3-epi-25(OH)D3 groups and each outcome variable. Covariates were selected based on a combination of biological plausibility and known factors from published studies, and those that were significantly different between 3-epi-25(OH)D3 groups. Comparative boxplots were employed to display group differences of outcome variables before and after adjusting for covariates. The entire patient population was also stratified into quartiles of BL values of 25(OH)D3 levels, 24,25(OH)2D3 levels and 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio. Additional multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to assess associations of BL groups of 25(OH)D3 levels, 24,25(OH)2D3 levels and 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio with each outcome variable. Regression analyses using linear mixed models were also conducted to assess associations between 3-epi-25(OH)D3 and each endpoint longitudinally in each group (KTR and NTWC) while accounting for repeated measure correlations within each patient adjusted by BL covariates. Separate linear mixed model analyses were performed to assess time effects and group (KTR or NTWC) effects associated with vitamin D metabolite differences followed by the Tukey's honestly significant difference test for post hoc pairwise comparisons. P-values of <.05 were regarded as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R Statistical Software (v4.1.1, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

Baseline characteristics of the study population [n = 165; mean (SD) age 47 (14) years] stratified into quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4) of BL 3-epi-25(OH)D3 serum levels are shown in Table 1. Patients in Q2 were significantly younger than patients in Q3 (P = .02) and Q4 (P = .03). Patients in Q2 also had a lower systolic blood pressure compared with Q1 (P = .03) and a lower HbA1c level compared with Q4 (P = .05). Patients in Q1 had a lower body mass index (BMI) compared with Q3 (P = .03); lower levels of corrected calcium compared with Q3 (P = .02); and higher levels of intact PTH (iPTH) compared with Q3 (P = .03) and Q4 (P = .04). Patients in Q3 had a lower prevalence of calcium channel blocker use compared with all other groups (P = .01). Serum 25(OH)D3 (P < .001); total 25(OH)D (P < .001); 24,25(OH)2D3 (P < .001); and 3-epi-25(OH)D3 as a % of total 25(OH)D3 (P = .01) were incrementally higher from Q1 to Q4.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3 quartiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: <0.4 ng/mL | Q2: 0.4 ng/mL | Q3: 0.5–0.7 ng/mL | Q4: 0.8+ ng/mL | ||

| Characteristicsa | (n = 51) | (n = 26) | (n = 47) | (n = 41) | P-value |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 44 (31–53) | 38 (31–49) | 52 (43–61) | 54 (38–62) | .01 |

| Male, n (%) | 33 (64.7) | 18 (69.2) | 22 (46.8) | 28 (68.3) | .11 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 24.4 (21.8–27.8) | 23.9 (20.9–29.0) | 26.8 (23.1–32.1) | 25.8 (23.9–29.6) | .01 |

| SBP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 140.6 (23.3) | 127.3 (18.3) | 130.8 (18.5) | 136.5 (18.2) | .02 |

| DBP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 82.1 (11.7) | 78.1 (10.4) | 77.4 (12.8) | 81.5 (13.0) | .19 |

| MAP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 101.6 (13.9) | 94.5 (12.4) | 95.2 (13.1) | 99.8 (13.1) | .04 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 48 (94.1) | 25 (96.2) | 40 (85.1) | 38 (92.7) | .37 |

| Smoking (ever), n (%) | 27 (52.9) | 12 (48.0) | 22 (47.8) | 23 (56.1) | .86 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 8 (17.0) | 7 (17.1) | .06 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 15 (29.4) | 6 (23.1) | 21 (44.7) | 20 (48.8) | .07 |

| Vitamin D supplement, n (%) | |||||

| Alphacalcidol | 25 (49.0) | 20 (76.9) | 32 (68.1) | 28 (68.3) | .06 |

| Calcitriol | 7 (13.7) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.4) | .05 |

| Paricalcitol | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0) | .17 |

| BP medication use | |||||

| ACEI or ARB blocker | 25 (49.0) | 12 (46.2) | 12 (25.5) | 17 (41.5) | .10 |

| Calcium antagonist | 26 (51.0) | 19 (73.1) | 16 (34.0) | 26 (63.4) | .01 |

| β-blocker | 23 (45.1) | 13 (50.0) | 12 (25.5) | 15 (36.6) | .12 |

| Diuretic | 8 (15.7) | 6 (23.1) | 6 (12.8) | 7 (17.1) | .72 |

| Dialysis status, n (%) | |||||

| Hemodialysis | 26 (51.0) | 17 (65.4) | 35 (74.5) | 25 (61.0) | .16 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 11 (21.6) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (4.3) | 4 (9.8) | |

| Predialysis | 14 (27.5) | 7 (26.9) | 10 (21.3) | 12 (29.3) | |

| CKD time, months, median (IQR) | 99 (60–180) | 150 (42–199) | 152 (72–252) | 156 (84–264) | .11 |

| Laboratory values, median (IQR) | |||||

| eGFR, mL/min | 8 (6–13) | 9 (6–13) | 8 (6–10) | 8 (7–14) | .75 |

| Troponin T, pg/L | 29.0 (16.2–48.9) | 29.9 (12.9–57.3) | 30.6 (15.2–42.1) | 31.6 (13.7–43.9) | .9 |

| ntProBNP, pg/mL | 223.1 (56.4–579.3) | 102.1 (33.2–282.4) | 198.1 (38.9–465.4) | 143.4 (56.3–384.3) | .43 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.3 (4.1–4.5) | 4.4 (4.3–4.5) | 4.3 (4.1–4.5) | 4.3 (4.2–4.6) | .42 |

| Corrected Ca, mmol/L | 2.2 (2.1–2.3) | 2.3 (2.2–2.4) | 2.3 (2.1–2.4) | 2.2 (2.2–2.3) | .01 |

| Phosphorus, mmol/L | 1.7 (1.4–1.9) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.4 (1.3–1.8) | 1.5 (1.2–1.7) | .04 |

| iPTH, pg/mL | 34.1 (16.5–60.2) | 19.2 (8.4–49.9) | 17.4 (9.7–36.1) | 19.4 (8.8–28.5) | .01 |

| CRP, mg/L | 4.1 (1.7–8.3) | 3.2 (0.9–7.3) | 2.5 (1.7–5.1) | 1.9 (1.0–6.9) | .53 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 5.4 (3.0–9.1) | 3.7 (2.7–5.8) | 4.6 (2.7–8.2) | 4.9 (1.9–7.4) | .49 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, mean (SD) | 11.4 (1.8) | 11.7 (1.2) | 11.9 (1.3) | 12.0 (1.2) | .30 |

| FGF23, pg/mL | 2765.5 (461.0–15 683.9) | 2437.8 (683.9–6328.8) | 5137.2 (808.9–8878.2) | 1765.7 (571.1–13 334.2) | .67 |

| HbA1c level, % | 5.4 (5.0–5.7) | 5.3 (5.1–5.5) | 5.4 (5.0–5.9) | 5.7 (5.4–5.9) | .04 |

| Vitamin D metabolites, median (IQR) | |||||

| 25(OH)D3, ng/mL | 9.8 (6.8–11.4) | 16.4 (14.2–18.8) | 19.3 (16.4–25.0) | 31.6 (24.0–39.5) | <.001 |

| 25(OH)D2, ng/mL | 0.9 (0.1–1.5) | 0.9 (0.2–1.5) | 1.3 (0.6–1.9) | 1.1 (0.5–1.3) | .17 |

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 10.3 (7.7–12.4) | 16.8 (15.0–19.6) | 20.3 (18.1–25.9) | 32.0 (25.4–40.7) | <.001 |

| 1α,25(OH)2D3, pg/mLb | 18.7 (1.0–24.9) | 25.8 (18.8–36.4) | 18.6 (13.3–32.7) | 20.4 (12.2–29.6) | .16 |

| 24,25(OH)2D3, ng/mL | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | <.001 |

| 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio | 49.5 (30.6–91.8) | 46.9 (32.6–89.5) | 41.9 (33.6–59.8) | 52 (34.5–61.2) | .88 |

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3, ng/mL | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | <.001 |

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3, % of total 25(OH)D3 | 2.5 (1.7–3.1) | 2.4 (2.0–2.7) | 2.8 (2.4–3.5) | 2.9 (2.4–3.7) | .01 |

aMissing values excluded. Q1: 3 missing CRP, 3 ntProBNP, 3 Troponin T and 3 IL-6. Q2: 1 missing CRP, 1 ntProBNP, 1 Troponin T, 1 IL-6 and 14 1α,25(OH)2D3. Q2: 4 missing 1α,25(OH)2D3. Q3: 1 missing CRP, 1 ntProBNP, 1 Troponin T and 1 IL-6. Q4: 3 missing CRP, 3 ntProBNP, 3 Troponin T, 3 IL-6 and 7 1α,25(OH)2D3. Q4: 7 missing 1α,25(OH)2D3.

b1α,25(OH)2D3 levels <10 pg/mL were converted to “1” for the purposes of analysis.

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ntProBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; Ca, calcium; CRP, C-reactive protein; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; total 25(OH)D, 25(OH)D3 + 25(OH)D2.

There were no significant differences in sex (P = .11), smoking status (P = .86), diabetes (P = .06), dyslipidemia (P = .07), dialysis status (P = .16), dialysis vintage (P = .11) or vitamin D supplementation use (all P ≥ .05). Additionally, there were no significant differences in Troponin T levels (P = .9), N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (ntProBNP; P = .43), albumin (P = .42), C-reactive protein (CRP; P = .53), interleukin-6 (IL-6; P = .49), hemoglobin (P = .30), fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23; P = .67), 25(OH)D2 (P = .17), 1α,25(OH)2D3 (P = .16) or 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio (P = .88) between quartile groups.

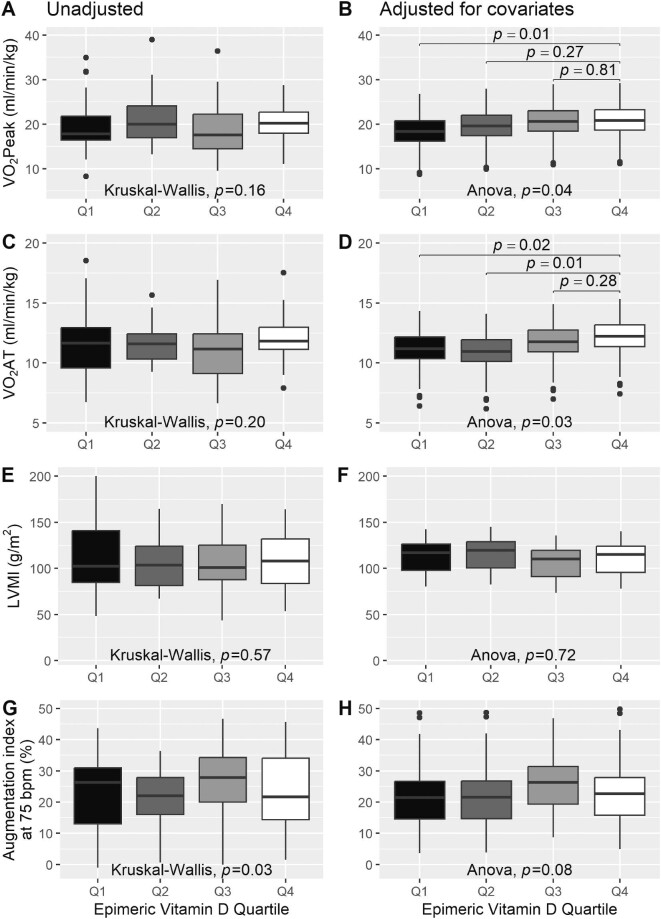

BL associations between 3-epi-25(OH)D3 and cardiovascular functional and structural indices

Unadjusted and adjusted BL functional and structural cardiovascular measures of the entire cohort are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. After adjusting for age, sex, BMI, mean arterial pressure (MAP), dyslipidemia and iPTH levels (Supplementary data, Table S1 and Fig. 1), patients with the lowest 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels (Q1) exhibited a significantly impaired VO2Peak [median (IQR) 18.4 (16.2–20.8) mL/min/kg] compared with patients with the highest 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels [Q4; 20.8 (18.6–23.2) mL/min/kg; P = .01]. Additionally, patients in Q1 [median (IQR) 11.2 (10.4–12.2) mL/min/kg ; P = .02] and Q2 [11.0 (10.1–11.9) mL/min/kg; P = .01] had a lower VO2AT compared with Q4 [12.2 (11.4–13.2) mL/min/kg].

Table 2:

Unadjusted functional and structural cardiovascular measures.

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3 quartiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristicsa | Q1: <0.4 ng/mL | Q2: 0.4 ng/mL | Q3: 0.5–0.7 ng/mL | Q4: 0.8+ ng/mL | P-value |

| VO2Peak, L/min | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.4 (1.3–1.9) | .23 |

| VO2Peak, mL/min/kg | 17.8 (16.3–22.2) | 20.0 (16.8–24.2) | 17.6 (14.4–22.2) | 20.2 (18.0–22.7) | .16 |

| VO2Peak, % predicted | 61 (51–72) | 61.5 (56–73) | 78 (60–86) | 72 (62–85) | <.001 |

| VO2 AT, mL/min/kg | 11.7 (9.4–13.0) | 11.6 (10.3–12.5) | 11.2 (9.1–12.4) | 11.8 (11.0–13.1) | .20 |

| AT, % predicted VO2Peak | 36.8 (32.7–42.7) | 35.5 (31.9–38.1) | 43.2 (38.3–49.6) | 42.0 (35.5–50.5) | <.001 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 30.0 (27.8–34.4) | 28.0 (26.5–31.0) | 29.1 (26.7–32.9) | 29.1 (27.6–34.7) | .29 |

| Peak workload, W | 110 (67–130) | 120.5 (86–144) | 95 (81–120) | 109 (77–142) | .14 |

| Endurance time, min | 9.5 (8.6–11.1) | 10.4 (9.2–11.8) | 10.8 (8.9–12.0) | 10.5 (9.8–12.0) | .06 |

| HRpeak, b.p.m., mean (SD) | 132.9 (24.3) | 137.9 (27.6) | 136.4 (26.8) | 133.6 (25.5) | .83 |

| Oxygen pulse, mL/min of O2 | 10.1 (8.2–12.7) | 11.5 (9.6–13.5) | 10.4 (8.2–13.0) | 11.2 (9.2–14.9) | .13 |

| Cardiac measures | |||||

| LVMI, g/m2 | 103.7 (84.8–142.3) | 104.7 (81.6–141.6) | 101.0 (87.7–127.2) | 108.0 (84.3–135.3) | .57 |

| LVEDV index, mL/m2 | 47.3 (37.1–58.6) | 48.8 (44.8–63.2) | 46.9 (35.0–60.2) | 50.3 (41.1–61.0) | .49 |

| LA volume index, mL/m2 | 26.0 (19.7–30.5) | 27.9 (19.1–35.5) | 25.4 (17.9–39.5) | 25.6 (20.1–32.5) | .83 |

| LVEF, % | 60.4 (56.0–65.0) | 62.0 (51.7–64.4) | 61.0 (56.6–65.6) | 63.0 (57.8–67.5) | .49 |

| E/mean e′ | 7.9 (6.2–10.5) | 8.0 (6.5–9.3) | 8.4 (6.9–10.5) | 8.0 (6.2–10.0) | .72 |

| Arterial indices | |||||

| Augmentation index at 75 b.p.m., % | 23.2 (10.7–30.7) | 21.3 (11.7–27.7) | 28.0 (19.7–35.0) | 21.7 (14.0–34.0) | .03 |

| PWV, m/s | 8.1 (6.9–10.0) | 7.1 (6.7–7.9) | 8.1 (7.3–9.5) | 8.1 (6.4–9.9) | .23 |

Data are presented as median (IQR) unless otherwise indicated.

aMissing values excluded. Q1: 1 missing AI75. Q2: 1 missing HRpeak and 1 oxygen pulse. Q3: 1 missing peak workload, 1 endurance time and 1 PWV. Q4: 1 missing VO2AT, 1 VE/VCO2 slope, 1 LA volume index, and 2 E/mean e′.

LA, left arterial; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; E/e′, ratio of early transmitral ventricular filling velocity to annular mitral velocity.

Table 3:

Adjusted functional and structural cardiovascular measures.

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3 quartiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristicsa | Q1: <0.4 ng/mL | Q2: 0.4 ng/mL | Q3: 0.5–0.7 ng/mL | Q4: 0.8+ ng/mL | P-value |

| VO2Peak, L/min | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | .14 |

| VO2Peak, mL/min/kg | 18.4 (16.2–20.8) | 19.6 (17.4–22.0) | 20.6 (18.4–23.0) | 20.8 (18.6–23.2) | .04 |

| VO2Peak, % predicted, mean (SD) | 64.3 (7.4) | 67.9 (7.4) | 71.2 (7.4) | 73.1 (7.4) | .04 |

| VO2AT, mL/min/kg | 11.2 (10.4–12.2) | 11.0 (10.1–11.9) | 11.8 (10.9–12.7) | 12.2 (11.4–13.2) | .03 |

| AT, % predicted VO2Peak, mean (SD) | 39.6 (5.8) | 39.1 (5.8) | 41.5 (5.8) | 43.6 (5.8) | .03 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 31.4 (29.9–32.6) | 30.0 (28.5–31.2) | 29.5 (28.0–30.7) | 30.5 (29.0–31.7) | .31 |

| Peak workload, W | 105.3 (84.7–122.9) | 113.3 (92.7–130.9) | 111.2 (90.6–128.8) | 117.3 (96.6–134.9) | .44 |

| Endurance time, min | 10.1 (9.6–10.5) | 10.6 (10.1–11.0) | 10.7 (10.2–11.1) | 10.9 (10.4–11.3) | .31 |

| HRpeak, b.p.m. | 131.9 (124.3–141.7) | 133.9 (126.2–143.7) | 135.3 (127.7–145.2) | 134.9 (127.2–144.7) | .9 |

| Oxygen pulse, mL/min of O2 | 11.3 (8.7–12.4) | 11.8 (9.2–12.9) | 12.0 (9.3–13.0) | 12.5 (9.9–13.6) | .40 |

| Cardiac measures | |||||

| LVMI, g/m2 | 117.1 (97.9–126.4) | 119.5 (100.3–128.8) | 110.3 (91.1–119.6) | 114.9 (95.7–124.2) | .72 |

| LVEDV index, mL/m2 | 47.0 (40.8–51.3) | 52.5 (46.3–56.8) | 51.4 (45.2–55.8) | 52.6 (46.4–56.9) | .35 |

| LA volume index, mL/m2 | 27.3 (23.7–31.2) | 31.7 (28.1–35.6) | 27.2 (23.6–31.2) | 28.0 (24.4–32.0) | .57 |

| LVEF, % | 60.4 (59.4–61.2) | 60.1 (59.0–60.8) | 61.7 (60.6–62.4) | 61.6 (60.6–62.4) | .85 |

| E/mean e′ | 8.9 (7.6–10.4) | 9.3 (8.0–10.8) | 9.2 (7.9–10.6) | 8.1 (6.8–9.5) | .53 |

| Arterial indices | |||||

| Augmentation index at 75 b.p.m., % | 21.4 (14.6–26.6) | 21.6 (14.7–26.7) | 26.5 (19.6–31.6) | 22.7 (15.8–27.9) | .08 |

| PWV, m/s | 8.5 (7.5–10.1) | 8.6 (7.5–10.2) | 8.4 (7.3–10.0) | 8.3 (7.2–9.9) | .9 |

Data are presented as median (IQR) unless otherwise indicated.

aValues were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, MAP, dyslipidemia and iPTH levels.

LA, left arterial; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; E/e′, ratio of early transmitral ventricular filling velocity to annular mitral velocity.

Figure 1:

Differences in BL VO2Peak, VO2AT, LVMI and AI75 between 3-epi-25(OH)D3 quartiles. (A) Unadjusted VO2Peak. (B) Adjusted VO2Peak. (C) Unadjusted VO2AT. (D) Adjusted VO2 AT. (E) Unadjusted LVMI. (F) Adjusted LVMI. (G) Unadjusted AI75. (H) Adjusted AI75. Values were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, MAP, dyslipidemia and iPTH levels.

No significant differences were observed between quartiles of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels in VE/VCO2 slope (P = .31), peak workload (P = .44), HRpeak (P = .92), O2 pulse (P = .40), LVMI (P = .72), LVEF (P = .85), AI75 (P = .08) or PWV (P = .9) after adjusting for covariates.

BL associations of 25(OH)D3 levels, 24,25(OH)2D3 levels and the 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio with cardiovascular functional and structural indices

To compare the role of epimeric vitamin D with non-epimeric forms, we next assessed whether 25(OH)D3, 24,25(OH)2D3 and the 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio were associated with cardiovascular functional structural endpoints. After controlling for age, sex, BMI, MAP, dyslipidemia and iPTH levels, neither 25(OH)D3 (Supplementary data, Table S2), 24,25(OH)2D3 (Supplementary data, Table S3) nor the 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio (Supplementary data, Table S4) was significantly associated with VO2Peak, VO2 at the point of anaerobic threshold (VO2AT), LVMI or AI75 (all P > .05).

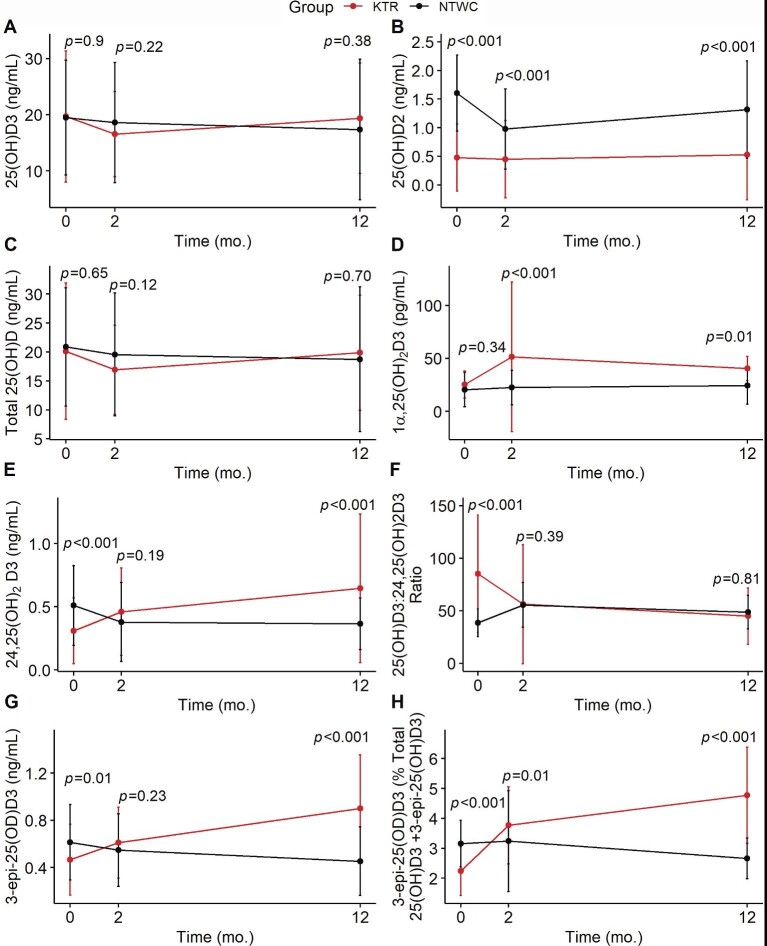

Longitudinal changes in vitamin D metabolite levels following kidney transplantation

Our group previously reported significant improvement in VO2Peak and VO2AT in the KTR group and a significant decline in these measures in the NTWC group [27]. We therefore examined serum levels of vitamin D metabolites prospectively in each group (NTWC and KTR) to evaluate the impact of kidney transplantation. Results are shown in Table 4 and illustrated in Fig. 2. The KTR group had significantly lower levels of 25(OH)D2 compared with the NTWC group at BL (P < .001), 2 months (P < .001) and 12 months (P < .001). No significant differences in 1α,25(OH)2D3 levels were observed between groups at BL (P = .34); however, these levels increased following kidney transplantation and were significantly higher in KTR compared with NTWC at 2 months (P < .001) and 12 months (P = .008). The KTR group also had significantly lower levels of 24,25(OH)2D3 compared with NTWC at BL (P = .003), but these levels increased following kidney transplantation and were significantly higher than NTWC at 12 months (P < .001). The KTR group had a significantly higher ratio of 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 compared with NTWC at BL (P < .001), but this ratio decreased following kidney transplantation and was similar to NTWC at 12 months (P = .81). Lastly, the KTR group also had lower levels of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 compared with NTWC at BL (P = .004), but these levels increased shortly following kidney transplantation and were significantly higher than NTWC at 12 months (P < .001). No significant group × time interactions were observed in 25(OH)D3 (P = .06) or total 25(OH)D (P = .10).

Table 4:

Changes in vitamin D metabolite levels before and after kidney transplant.

| Timepoint | Main group effect | Main time effect | Group × time interaction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variablea | Baseline | 2 months | 12 months | F | P | F | P | F | P |

| 25(OH)D3, ng/mL | 0.005 | .9 | 4.142 | .02 | 2.850 | .06 | |||

| KTR | 19.70 (11.70) | 16.54 (7.58) | 19.36 (9.85) | ||||||

| NTWC | 19.49 (10.24) | 18.60 (10.70) | 17.36 (12.51) | ||||||

| P-valuec | .9 | .22 | .38 | ||||||

| 25(OH)D2, ng/mL | 78.064 | <.001 | 16.832 | <.001 | 13.220 | <.001 | |||

| KTR | 0.48 (0.59) | 0.45 (0.68) | 0.53 (0.79) | ||||||

| NTWC | 1.60 (0.66) | 0.98 (0.70) | 1.32 (0.85) | ||||||

| P-valuec | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 0.381 | .54 | 4.906 | .01 | 2.280 | .10 | |||

| KTR | 20.11 (11.77) | 16.92 (7.71) | 19.85 (9.93) | ||||||

| NTWC | 20.86 (10.20) | 19.57 (10.63) | 18.72 (12.49) | ||||||

| P-valuec | .65 | .12 | .70 | ||||||

| 1α,25(OH)2D3, pg/mLb | 22.358 | <.001 | 6.554 | .01 | 4.706 | .01 | |||

| KTR | 25.24 (12.86) | 51.48 (70.69) | 40.46 (11.47) | ||||||

| NTWC | 20.55 (16.38) | 22.44 (16.18) | 24.26 (17.58) | ||||||

| P-valuec | .34 | <.001 | .01 | ||||||

| 24,25(OH)2D3, ng/mL | 1.227 | .27 | 5.565 | .01 | 31.000 | <.001 | |||

| KTR | 0.31 (0.26) | 0.46 (0.35) | 0.65 (0.59) | ||||||

| NTWC | 0.51 (0.31) | 0.38 (0.31) | 0.37 (0.20) | ||||||

| P-valuec | <.001 | .19 | <.001 | ||||||

| 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio | 12.256 | <.001 | 7.314 | <.001 | 35.331 | <.001 | |||

| KTR | 85.22 (55.79) | 56.27 (56.49) | 44.95 (26.80) | ||||||

| NTWC | 38.62 (13.11) | 55.55 (21.35) | 48.72 (15.96) | ||||||

| P-valuec | <.001 | .39 | .81 | ||||||

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3, ng/mL | 8.252 | .01 | 10.962 | <.001 | 55.476 | <.001 | |||

| KTR | 0.47 (0.30) | 0.61 (0.30) | 0.90 (0.45) | ||||||

| NTWC | 0.61 (0.32) | 0.55 (0.31) | 0.45 (0.29) | ||||||

| P-valuec | .01 | .23 | <.001 | ||||||

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3, % of total 25(OH)D3 | 18.908 | <.001 | 36.156 | <.001 | 70.736 | <.001 | |||

| KTR | 2.24 (0.82) | 3.77 (1.29) | 4.78 (1.61) | ||||||

| NTWC | 3.16 (0.78) | 3.24 (1.69) | 2.66 (0.68) | ||||||

| P-valuec | <.001 | .01 | <.001 | ||||||

Data are presented as mean (SD).

aMissing values excluded. KTR at BL: 1α,25(OH)2D3 (n = 32). KTR at 2 months: 25(OH)D3 (n = 4), 25(OH)D2 (n = 3), total 25(OH)D (n = 3), 1α,25(OH)2D3 (n = 18), 24,25(OH)2D3 (n = 3), 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio (n = 3), 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (n = 3). KTR at 12 months: 25(OH)D3 (n = 3), 25(OH)D2 (n = 3), total 25(OH)D (n = 3), 1α,25(OH)2D3 (n = 17), 24,25(OH)2D3 (n = 3), 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio (n = 3), 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (n = 3). NTWC at 2 months: 25(OH)D3 (n = 1), 25(OH)D2 (n = 1), total 25(OH)D (n = 1), 1α,25(OH)2D3 (n = 20), 24,25(OH)2D3 (n = 1), 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio (n = 1), 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (n = 1). NTWC at 12 months: 25(OH)D3 (n = 3), 25(OH)D2 (n = 3), total 25(OH)D (n = 3), 1α,25(OH)2D3 (n = 1), 24,25(OH)2D3 (n = 3), 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio (n = 3), 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (n = 3).

b1α,25(OH)2D3 levels <10 pg/mL were converted to “1” for the purposes of analysis.

P-value for comparison between two groups at each respective time point.

Total 25(OH)D, 25(OH)D3 + 25(OH)D2.

Figure 2:

Vitamin D metabolite levels in kidney transplant patients (KTR group) and non-transplant waitlisted patients (NTWC group). (A) 25(OH)D3. (B) 25(OH)D2. (C) Total 25(OH)D [25(OH)D3 + 25(OH)D2]. (D) 1α,25(OH)2D3. (E) 24,25(OH)2D3. (F) 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio. (G) 3-epi-25(OH)D3. (H) 3-epi-25(OH)D3 as % of total 25(OH)D3. P-values are displayed for comparison between two groups at each respective time point.

Longitudinal associations between 3-epi-25(OH)D3 and cardiovascular function and structure

We next examined the relationship between longitudinal 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels and longitudinal VO2Peak, VO2AT, LVMI and AI75 after adjusting for BL age, sex, BMI, MAP, dyslipidemia and iPTH levels in each group (KTR and NTWC) using a linear mixed model regression (Table 5). We found that longitudinal 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels were significantly associated with longitudinal VO2Peak [β (standard error, SE) = 2.53 (0.56), P < .001 in KTR and 2.73 (0.70), P < .001 in NTWC] and VO2AT [β (SE) = 1.58 (0.31), P < .001 in KTR and 1.37 (0.35), P < .001 in NTWC] in both groups after adjusting for BL covariates.

Table 5:

Linear mixed model of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 with VO2Peak, VO2 AT, LVMI and AI75 in kidney transplant recipients (KTR group) and non-transplant waitlist patients (NTWC group).

| KTR | NTWC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β (SE) | P-value | β (SE) | P-value |

| VO2Peak | ||||

| Baseline age | −0.15 (0.04) | <.001 | −0.11 (0.03) | <.001 |

| Male sex (ref = Female) | 5.46 (0.93) | <.001 | 2.41 (0.82) | .01 |

| Baseline BMI | −0.33 (0.13) | <.001 | −0.23 (0.07) | .01 |

| Baseline MAP | 0.07 (0.03) | .01 | 0.05 (0.03) | .08 |

| Baseline iPTH | −0.03 (0.01) | .04 | −0.01 (0.01) | .34 |

| Baseline dyslipidemia | −1.75 (1.05) | .10 | −1.80 (0.84) | .03 |

| 3-epi25(OH)D3 | 2.53 (0.56) | <.001 | 2.73 (0.70) | <.001 |

| VO2AT | ||||

| Baseline age | −0.04 (0.02) | .02 | −0.03 (0.02) | .11 |

| Male sex (ref = female) | 2.06 (0.46) | <.001 | 0.51 (0.42) | .23 |

| Baseline BMI | −0.20 (0.06) | .01 | −0.17 (0.04) | <.001 |

| Baseline MAP | 0.01 (0.02) | .55 | 0.01 (0.01) | .44 |

| Baseline iPTH | −0.01 (0.01) | .25 | 0.00 (0.01) | .85 |

| Baseline dyslipidemia | −0.76 (0.51) | .15 | −0.60 (0.43) | .16 |

| 3-epi25(OH)D3 | 1.58 (0.31) | <.001 | 1.37 (0.35) | <.001 |

| LVMI | ||||

| Baseline age | 0.35 (0.27) | .21 | 0.33 (0.27) | .23 |

| Male sex (ref = Female) | 23.39 (7.25) | .01 | 21.2 (7.13) | .01 |

| Baseline BMI | −0.12 (0.99) | .90 | −1.10 (0.64) | <.001 |

| Baseline MAP | −0.12 (0.27) | .63 | 0.01 (0.24) | .44 |

| Baseline iPTH | −0.10 (0.09) | .29 | 0.02 (0.09) | .85 |

| Baseline dyslipidemia | −0.18 (8.18) | .98 | 12.79 (7.30) | .08 |

| 3-epi25(OH)D3 | −0.63 (4.33) | .88 | −13.67 (6.97) | .05 |

| AI75 | ||||

| Baseline age | 0.51 (0.07) | <.001 | 0.43 (0.07) | <.001 |

| Male sex (ref = Female) | −14.24 (1.91) | <.001 | −8.51 (1.85) | <.001 |

| Baseline BMI | −0.34 (0.26) | .20 | −0.59 (0.17) | <.001 |

| Baseline MAP | 0.09 (0.07) | .20 | 0.12 (0.06) | .05 |

| Baseline iPTH | 0.05 (0.02) | .04 | 0.01 (0.02) | .64 |

| Baseline dyslipidemia | −0.04 (2.15) | .98 | −2.39 (1.89) | .21 |

| 3-epi25(OH)D3 | 0.84 (1.56) | .59 | −0.08 (1.96) | .97 |

SE, standard error.

No significant associations were observed between longitudinal 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels and longitudinal LVMI [β (SE) = –0.63 (4.33), P = .88 in KTR and –13.67 (6.97), P = .05 in NTWC] or AI75 [β (SE) = 0.84 (1.56), P = .59 in KTR and –0.08 (1.96), P = .9 in NTWC].

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to comprehensively assess the relationship between the C3-epimer of 25(OH)D3—3-epi-25(OH)D3—and cardiovascular functional and structural endpoints in patients with advanced CKD before and after kidney transplantation. Our BL data demonstrated that patients with low serum levels of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (<0.4 ng/mL) had a significantly lower VO2Peak than patients with the highest 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels (≥0.8 ng/mL) after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, MAP, dyslipidemia and iPTH levels. The median difference of 2.4 mL/min/kg in adjusted VO2Peak between Q1 and Q4 exceeds the “minimum clinically important difference” of 1.5 mL/min/kg reported previously in patients with CKD [31], indicating that this is a clinically meaningful difference in cardiovascular functional capacity. Serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels were also associated with VO2AT after adjusting for covariates. Since most activities of daily living do not require maximal effort, VO2AT is widely used as a submaximal index of cardiovascular functional capacity that is independent of maximal effort, and therefore perhaps more relevant to functional independence [32].

We found that 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels increased in the KTR group and decreased in the NTWC group at 12 months, and these longitudinal changes were significantly associated with longitudinal VO2Peak and VO2AT in both groups. This finding suggests that changes in 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels may play a role in post-transplant improvements in cardiovascular functional capacity. However, very little is known regarding the factors that influence vitamin D epimerization. It has previously been shown that LLC-PK1 cells, a porcine kidney cell line, preferentially produced the inactive metabolite 24,25(OH)2D3 rather than 3-epi-25(OH)D3 in vitro [1, 33]. Therefore, we speculate that kidney transplantation may have either upregulated C-3 epimerization in extrarenal tissues, downregulated C-24 oxidation by the kidneys, or both. Kidney transplantation also resulted in significant increases in 1α,25(OH)2D3 despite no change in total 25(OH)D, likely due to increased CYP27B1 activity in the functioning allograft and/or reductions in FGF23 [34]. Although we did not measure longitudinal changes in 3-epi-1α,25(OH)2D3 following kidney transplantation, studies have found that the perfused rat kidney does not metabolize 1α,25(OH)2D3 through the C-3 epimerization pathway [35, 36]. Further studies are needed to determine whether 3-epi-1α,25(OH)2D3 levels are altered in CKD and following kidney transplantation.

It has previously been suggested that vitamin D status in CKD should be assessed by measuring both 25(OH)D concentrations and surrogate measures of enzymatic activity, such as 24,25(OH)2D concentrations or the ratio of 25(OH)D3 to 24,25(OH)2D3 (or vice versa)—also known as vitamin D metabolite ratio (VMR) [37, 38]. Patients with advanced CKD on hemodialysis have been shown to produce low levels of 24,25(OH)2D3, even after vitamin D3 supplementation [39], and exhibit elevated 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio compared with both healthy individuals and vitamin D deficient individuals with normal kidney function [40], suggesting a loss or downregulation of 24-hydroxylation of 25(OH)D3 with advanced CKD. Moreover, 24,25(OH)2D3:25(OH)D3 ratio was more strongly associated with both loss of bone mineral density and fracture risk compared with 25(OH)D3, which indicates that VMR is a clinically significant measure of bone health [41]. In the present study, however, we found no significant association between 25(OH)D3, 24,25(OH)2D3 or the 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio with any cardiovascular functional or structural measure. Therefore, epimeric forms of vitamin D may be more clinically significant for cardiovascular health than non-epimeric measures of vitamin D status in patients with CKD.

Clinical trials in patients with advanced CKD have shown that treatment with non-epimeric 1α,25(OH)2D3 or its analogs can suppress PTH levels but at the expense of potential increases in serum calcium and phosphate [13, 14]. In this context, the observation that those with the lowest levels of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 had significantly elevated PTH and phosphate levels compared with those in the higher quartiles of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels is a significant finding. The ability of 3-epi-1α,25(OH)2D3 to effectively modulate PTH secretion, coupled with its reduced potential for causing hypercalcemia, provides a compelling argument for considering it as a potential therapeutic option [16, 17]. Further research is needed to explore the clinical implications of administering 3-epi-25(OH)D3 or 3-epi-1α,25(OH)2D3 in the context of PTH regulation and mineral metabolism.

Results from the Paricalcitol Capsule Benefits in Renal Failure-Induced Cardiac Morbidity (PRIMO) trial showed that 48-week therapy with paricalcitol did not alter LVMI compared with a placebo in patients with CKD stages 3–4, though paricalcitol treatment was associated with fewer cardiovascular-related hospitalizations [13]. Similar results were reported in the Effect of Paricalcitol on Left Ventricular Mass and Function in CKD (OPERA) trial [14]. On the other hand, Ryan and colleagues [42] showed that treatment with 1α,25(OH)2D3 in human skeletal muscle cells significantly increased mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate, mitochondrial biogenesis and enzyme activity. Moreover, Sinha and colleagues [43] showed that vitamin D supplementation (vitamin D3, 20 000 IU on alternate days for 10–12 weeks) augments skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity in vivo as assessed by phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy in 12 individuals with severe vitamin D deficiency. It is plausible that vitamin D supplementation may enhance cardiovascular functional capacity by improving skeletal muscle oxygen uptake (i.e. mitochondrial function), which was not assessed in the PRIMO and OPERA studies [13, 14]. It should also be noted that neither trial reported changes in vitamin D metabolites, and therefore the possibility that paricalcitol may have in fact led to reductions in 1α,25(OH)2D and 25(OH)D, as has been previously reported in CKD [15], cannot be excluded. Moreover, both studies reported evidence of hypercalcemia and reduced renal function in response to paricalcitol treatment. The lower rate of inactivation [18] and lower calcemic activity [16] associated with 3-epi-1α,25(OH)2D3 in addition to the association between higher levels of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 and higher cardiovascular functional capacity reported in the present study provide rationale for a future study investigating the potential health benefits of supplementation with 3-epi-25(OH)D3.

FGF23 is known to regulate vitamin D metabolism by inhibiting 1α-hydroxylase activity, stimulating vitamin D degradation, and is also associated with LV hypertrophy and impaired cardiac function [44, 45]. To this end, a recently published study from our group examined the association between FGF23 and cardiovascular functional and structural endpoints in patients with CKD from the CAPER study cohort [34]. In this paper, we demonstrated that high levels of FGF23 in advanced CKD prior to transplantation were associated with impaired VO2Peak and increased left ventricular mass. Furthermore, kidney transplantation was found to significantly reduce FGF23 levels, and this was associated with improvement in VO2Peak at the 1-year follow-up post-transplantation. The interplay between FGF23, vitamin D metabolism, and cardiac outcomes provides rationale for studies to investigate whether FGF23 can regulate epimeric forms of vitamin D. However, we found no significant differences in FGF23 levels between the 3-epi-25(OH)D3 quartile groups at BL.

Increased urinary loss of vitamin D-binding protein (VDBP), the main transporter for circulating vitamin D metabolites, has been postulated to contribute to vitamin D deficiency in proteinuric conditions [46]. The present study measured total concentrations (both free and bound to VDBP or albumin) of vitamin D metabolites. Therefore, we can only speculate on the role of VDBP on 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels. A previous study in patients with proteinuria showed that urinary VDBP excretion was significantly increased in proportion to proteinuria [47]. However, urinary VDBP loss was not associated with reduced plasma levels of VDBP, 25(OH)D3 or 1α,25(OH)2D3. Although urinary loss of VDBP was significantly reduced by antiproteinuric intervention, this large change in urinary VDBP had no effect on plasma VDBP, 25(OH)D3 or 1α,25(OH)2D3. Moreover, 3-epi-25(OH)D3 has been shown to have a lower affinity for VDBP (∼36%) as compared with 25(OH)D3 [1]. Taken together, these data suggest that potential reductions in circulating VDBP in patients with CKD in the present study likely would have little to no effect on 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels.

Although 3-epi-25(OH)D3 has recently been recognized as a potentially clinically significant vitamin D metabolite, very little is known regarding the factors that regulate its production. Early preterm infants have been shown to exhibit the highest 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels, which suggests that vitamin D epimerization may result from immature hepatic vitamin D metabolism [48, 49]. However, adults with liver disease do not exhibit differences in 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels when compared with healthy adults, and hepatic CYP enzymes are not involved in the vitamin D epimerization process [49, 50]. Therefore, whether liver function regulates vitamin D epimerization remains unclear. Moreover, serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels have been shown to increase to a similar extent with both oral vitamin D3 supplementation and exposure to ultraviolet radiation in humans, indicating that both dietary intake and dermal synthesis of vitamin D3 contribute to serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 concentration [51, 52]. Over-the-counter vitamin D3 supplements were shown not to contain 3-epi-25(OH)D3 [53]; however, whether a natural dietary source of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 exists remains unknown. None of the patients in the present study was taking inactive vitamin D supplements at the time of the study, and we found no significant differences in the proportion of patients taking active vitamin D compounds (alphacalcidol, calcitriol and paricalcitol) between quartiles of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels at BL. Serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels were significantly correlated with 25(OH)D3 in both the KTR and NTWC groups at BL and at 12 months post-transplant (Supplementary data, Fig. S1). These results are in agreement with prior studies that have found that serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels correlate with 25(OH)D3 levels [51, 54]. However, it is not clear whether inactive vitamin D compounds that improve 25(OH)D3 levels could also improve 3-epi-25(OH)D3 enough to have a therapeutic effect.

Our study has several strengths. By incorporating transthoracic echocardiography and assessment of vascular compliance in parallel with CPET measures, this study was the first to comprehensively assess the link between 3-epi-25(OH)D3 and both cardiovascular function and structure. CPET provides assessment of the integrative exercise responses involving the entire oxygen transport system, and combined with cardiac imaging and tonometric measurements, this has provided in-depth analysis of the role of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 in regulating cardiovascular health in CKD. In addition, this is the first study to examine longitudinal changes in 3-epi-25(OH)D3 following kidney transplantation, providing evidence of increased relative [% of total 25(OH)D] and absolute levels of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 following kidney transplantation that were associated with both VO2Peak and VO2AT. However, the results of the present study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. Firstly, we did not assess differences in skeletal muscle O2 extraction or measures of skeletal muscle function. Therefore, we could not examine the association between noncardiac components of cardiovascular functional capacity and 3-epi-25(OH)D3. Additionally, we were unable to assess changes in 3-epi-1α,25(OH)2D3 or the inactive metabolite, 3-epi-1α,24,25(OH)3D3, in this initial proof-of-concept study [55].

CONCLUSION

We present, for the first time, a significant association between serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels and cardiovascular functional capacity in patients with advanced CKD and kidney transplant recipients. We found that serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels were significantly associated with VO2Peak and VO2AT as assessed by CPET at BL after adjusting for covariates. Differences in cardiovascular functional capacity were observed despite no differences in HRpeak, O2 pulse, LVMI, LVEF or arterial stiffness, suggesting that 3-epi-25(OH)D3 may regulate noncardiac factors of VO2Peak. Moreover, since kidney transplantation resulted in significant increases in serum 3-epi-25(OH)D3 that were associated with improved VO2Peak and VO2AT at 12 months post-transplant, we postulate that changes in circulating 3-epi-25(OH)D3 levels may underlie alterations in cardiovascular functional capacity. Given the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and physical function impairments in patients with CKD, further investigation is needed to understand the role and mechanisms of vitamin D C3-epimers on cardiovascular and musculoskeletal function in CKD.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Eliott Arroyo, Division of Nephrology & Hypertension, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Cecilia A Leber, Division of Nephrology & Hypertension, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA; Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA.

Heather N Burney, Department of Biostatistics and Health Data Science, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Yang Li, Department of Biostatistics and Health Data Science, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Xiaochun Li, Department of Biostatistics and Health Data Science, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Tzong-shi Lu, Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Glenville Jones, Department of Biomedical and Molecular Sciences and Medicine, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Martin Kaufmann, Department of Biomedical and Molecular Sciences and Medicine, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Stephen M S Ting, Department of Medicine, University Hospitals Birmingham National Health Service Foundation Trust, Birmingham, UK.

Thomas F Hiemstra, Cambridge Clinical Trials Unit, Cambridge University Hospitals National Health Service Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK; School of Clinical Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

Daniel Zehnder, Department of Nephrology; Department of Acute Medicine, North Cumbria University Hospital National Health Service Trust, Carlisle, UK.

Kenneth Lim, Division of Nephrology & Hypertension, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

K.L. is co-founder and consultant to OVIBIO Corporation. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

E.A.: writing—review and editing, formal analysis, visualization. C.A.L.: writing—original draft, formal analysis. H.N.B.: formal analysis, visualization, data curation. Y.L.: formal analysis, supervision. X.L.: formal analysis, supervision. T.-s.L.: writing—review and editing. G.J.: methodology, investigation, resources. M.K.: methodology, investigation, resources. S.M.S.T.: writing—review and editing, conceptualization, methodology, investigation. T.F.H.: writing—review and editing, investigation. D.Z.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, supervision. K.L.: writing—review and editing, conceptualization, investigation supervision.

FUNDING

This study was funded by a grant from the British Heart Foundation Project (PG/11/66/28 982). This work was supported by an NIH K23 DK115683 grant provided to K.L.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kamao M, Tatematsu S, Hatakeyama Set al. C-3 epimerization of vitamin D3 metabolites and further metabolism of C-3 epimers: 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 is metabolized to 3-epi-25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and subsequently metabolized through C-1α or C-24 hydroxylation. J Biol Chem 2004;279:15897–907. 10.1074/jbc.M311473200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abouzid M, Karaźniewicz-Łada M, Pawlak Ket al. Measurement of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D2, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 3-epi-25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in population of patients with cardiovascular disease by UPLC-MS/MS method. J Chromatogr B 2020;1159:122350. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2020.122350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li Y-m, Feng Q, Jiang W-qet al. Evaluation of vitamin D storage in patients with chronic kidney disease: detection of serum vitamin D metabolites using high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2021;210:105860. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Watson EL, Wilkinson TJ, O'Sullivan TFet al. Association between vitamin D deficiency and exercise capacity in patients with CKD, a cross-sectional analysis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2021;210:105861. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drechsler C, Pilz S, Obermayer-Pietsch Bet al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with sudden cardiac death, combined cardiovascular events, and mortality in haemodialysis patients. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2253–61. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drechsler C, Verduijn M, Pilz Set al. Vitamin D status and clinical outcomes in incident dialysis patients: results from the NECOSAD study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:1024–32. 10.1093/ndt/gfq606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Boer IH, Kestenbaum B, Shoben ABet al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels inversely associate with risk for developing coronary artery calcification. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:1805–12. 10.1681/ASN.2008111157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thompson S, James M, Wiebe Net al. Cause of death in patients with reduced kidney function. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;26:2504–11. 10.1681/ASN.2014070714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hiemstra TF, Lim K, Thadhani Ret al. Vitamin D and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:4033–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bodyak N, Ayus JC, Achinger Set al. Activated vitamin D attenuates left ventricular abnormalities induced by dietary sodium in Dahl salt-sensitive animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:16810–5. 10.1073/pnas.0611202104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Riek AE, Oh J, Bernal-Mizrachi C.. 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D suppresses macrophage migration and reverses atherogenic cholesterol metabolism in type 2 diabetic patients. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2013;136:309–12. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mathew S, Lund RJ, Chaudhary LRet al. Vitamin D receptor activators can protect against vascular calcification. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:1509–19. 10.1681/ASN.2007080902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thadhani R, Appelbaum E, Pritchett Yet al. Vitamin D therapy and cardiac structure and function in patients with chronic kidney disease: the PRIMO randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012;307:674–84. 10.1001/jama.2012.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang AY-M, Fang F, Chan Jet al. Effect of paricalcitol on left ventricular mass and function in CKD—The OPERA trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;25:175–86. 10.1681/ASN.2013010103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Boer IH, Sachs M, Hoofnagle ANet al. Paricalcitol does not improve glucose metabolism in patients with stage 3–4 chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2013;83:323–30. 10.1038/ki.2012.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown AJ, Ritter CS, Weiskopf ASet al. Isolation and identification of 1alpha-hydroxy-3-epi-vitamin D3, a potent suppressor of parathyroid hormone secretion. J Cell Biochem 2005;96:569–78. 10.1002/jcb.20553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown A, Ritter C, Slatopolsky Eet al. 1α, 25-Dihydroxy-3-epi-vitamin D3, a natural metabolite of 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, is a potent suppressor of parathyroid hormone secretion. J Cell Biochem 1999;73:106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rhieu SY, Annalora AJ, Wang Get al. Metabolic stability of 3-epi-1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 over 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: metabolism and molecular docking studies using rat CYP24A1. J Cell Biochem 2013;114:2293–305. 10.1002/jcb.24576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bansal N, Keane M, Delafontaine Pet al. A longitudinal study of left ventricular function and structure from CKD to ESRD: the CRIC study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:355–62. 10.2215/CJN.06020612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mukai H, Ming P, Lindholm Bet al. Lung dysfunction and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press Res 2018;43:522–35. 10.1159/000488699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Górriz JL, Molina P, Cerverón MJet al. Vascular calcification in patients with nondialysis CKD over 3 years. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:654–66. 10.2215/CJN.07450714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kestenbaum B, Gamboa J, Liu Set al. Impaired skeletal muscle mitochondrial bioenergetics and physical performance in chronic kidney disease. JCI Insight 2020;5:e133289. 10.1172/jci.insight.133289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arroyo E, Umukoro PE, Burney HNet al. Initiation of dialysis is associated with impaired cardiovascular functional capacity. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e025656. 10.1161/JAHA.122.025656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chinnappa S, Lewis N, Baldo Oet al. Cardiac and noncardiac determinants of exercise capacity in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021;32:1813. 10.1681/ASN.2020091319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sietsema KE, Amato A, Adler SGet al. Exercise capacity as a predictor of survival among ambulatory patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 2004;65:719–24. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00411.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ross R, Blair SN, Arena Ret al. Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: a case for fitness as a clinical vital sign: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;134:e653–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lim K, Ting SMS, Hamborg Tet al. Cardiovascular functional reserve before and after kidney transplant. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:420–9. 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ting SM, Hamborg T, McGregor Get al. Reduced cardiovascular reserve in chronic kidney failure: a matched cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;66:274–84. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.02.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DYet al. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation: including pathophysiology and clinical applications. Med Sci Sports Exercise 2005;37:1249. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaufmann M, Schlingmann KP, Berezin Let al. Differential diagnosis of vitamin D–related hypercalcemia using serum vitamin D metabolite profiling. J Bone Miner Res 2021;36:1340–50. 10.1002/jbmr.4306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wilkinson TJ, Watson EL, Xenophontos Set al. The “minimum clinically important difference” in frequently reported objective physical function tests after a 12-week renal rehabilitation exercise intervention in nondialysis chronic kidney disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2019;98:431–7. 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lim K, McGregor G, Coggan ARet al. Cardiovascular functional changes in chronic kidney disease: integrative physiology, pathophysiology and applications of cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Front Physiol 2020;11:572355. 10.3389/fphys.2020.572355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kamao M, Tatematsu S, Sawada Net al. Cell specificity and properties of the C-3 epimerization of vitamin D3 metabolites. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2004;89–90:39–42. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Halim A, Burney HN, Li Xet al. FGF23 and cardiovascular structure and function in advanced chronic kidney disease. Kidney 360 2022;3:1529–4110.34067/kid.0002192022. 10.34067/KID.0002192022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bischof M, Siu-Caldera M-L, Weiskopf Aet al. Differentiation-related pathways of 1α, 25-dihydroxycholecalciferol metabolism in human colon adenocarcinoma-derived Caco-2 cells: production of 1α, 25-dihydroxy-3epi-cholecalciferol. Exp Cell Res 1998;241:194–201. 10.1006/excr.1998.4044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Siu-Caldera M, Sekimoto H, Brem Aet al. Metabolism of 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin-D3 into 1α, 25-dihydroxy-3-epi-vitamin-D3 in rat osteosarcoma cells (UMR 106 and ROS 17/2.8) and rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Pediatr Res 1999;45:98. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Melamed ML, Chonchol M, Gutiérrez OMet al. The role of vitamin D in CKD stages 3 to 4: report of a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;72:834–45. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.06.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kaufmann M, Gallagher JC, Peacock Met al. Clinical utility of simultaneous quantitation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D by LC-MS/MS involving derivatization with DMEQ-TAD. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:2567–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Graeff-Armas LA, Kaufmann M, Lyden Eet al. Serum 24, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 response to native vitamin D2 and D3 supplementation in patients with chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis. Clin Nutr 2018;37:1041–5. 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kaufmann M, Morse N, Molloy BJet al. Improved screening test for idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia confirms residual levels of serum 24, 25-(OH) 2D3 in affected patients. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32:1589–96. 10.1002/jbmr.3135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ginsberg C, Katz R, de Boer IHet al. The 24,25 to 25-hydroxyvitamin D ratio and fracture risk in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Bone 2018;107:124–30. 10.1016/j.bone.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ryan ZC, Craig TA, Folmes CDet al. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and dynamics in human skeletal muscle cells. J Biol Chem 2016;291:1514–28. 10.1074/jbc.M115.684399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sinha A, Hollingsworth KG, Ball Set al. Improving the vitamin D status of vitamin D deficient adults is associated with improved mitochondrial oxidative function in skeletal muscle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:E509–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Yet al. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:429–35. 10.1359/JBMR.0301264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ky B, Shults J, Keane MGet al. FGF23 modifies the relationship between vitamin D and cardiac remodeling. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:817–24. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. González EA, Sachdeva A, Oliver DAet al. Vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency in chronic kidney disease. A single center observational study. Am J Nephrol 2004;24:503–10. 10.1159/000081023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Doorenbos CR, de Cuba MM, Vogt Let al. Antiproteinuric treatment reduces urinary loss of vitamin D-binding protein but does not affect vitamin D status in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2012;128:56–61. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ooms N, van Daal H, Beijers AMet al. Time-course analysis of 3-epi-25-hydroxyvitamin D3 shows markedly elevated levels in early life, particularly from vitamin D supplementation in preterm infants. Pediatr Res 2016;79:647–53. 10.1038/pr.2015.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Singh RJ, Taylor RL, Reddy GSet al. C-3 epimers can account for a significant proportion of total circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D in infants, complicating accurate measurement and interpretation of vitamin D status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:3055–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stokes CS, Volmer DA.. Assessment of 3-epi-25-hydroxyvitamin D levels during cholecalciferol supplementation in adults with chronic liver diseases. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2016;41:1311–7. 10.1139/apnm-2016-0196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ghaly S, Bliuc D, Center JRet al. Vitamin D C3-epimer levels are proportionally higher with oral vitamin D supplementation compared to ultraviolet irradiation of skin in mice but not humans. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2019;186:110–6. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cashman KD, Kinsella M, Walton Jet al. The 3 epimer of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol is present in the circulation of the majority of adults in a nationally representative sample and has endogenous origins. J Nutr 2014;144:1050–7. 10.3945/jn.114.192419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yazdanpanah M, Bailey D, Walsh Wet al. Analytical measurement of serum 25-OH-vitamin D3, 25-OH-vitamin D2 and their C3-epimers by LC–MS/MS in infant and pediatric specimens. Clin Biochem 2013;46:1264–71. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Baecher S, Leinenbach A, Wright JAet al. Simultaneous quantification of four vitamin D metabolites in human serum using high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry for vitamin D profiling. Clin Biochem 2012;45:1491–6. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reddy GS, Muralidharan KR, Okamura WHet al. Metabolism of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its C-3 epimer 1α,25-dihydroxy-3-epi-vitamin D3 in neonatal human keratinocytes. Steroids 2001;66:441–50. 10.1016/S0039-128X(00)00228-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.