Abstract

Erwinia amylovora causes fire blight disease of apple, pear, and other members of the Rosaceae. Here we present the first evidence for autoinduction in E. amylovora and a role for an N-acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL)-type signal. Two major plant virulence traits, production of extracellular polysaccharides (amylovoran and levan) and tolerance to free oxygen radicals, were controlled in a bacterial-cell-density-dependent manner. Two standard autoinducer biosensors, Agrobacterium tumefaciens NTL4 and Vibrio harveyi BB886, detected AHL in stationary-phase cultures of E. amylovora. A putative AHL synthase gene, eamI, was partially sequenced, which revealed homology with autoinducer genes from other bacterial pathogens (e.g., carI, esaI, expI, hsII, yenI, and luxI). E. amylovora was also found to carry eamR, a convergently transcribed gene with homology to luxR AHL activator genes in pathogens such as Erwinia carotovora. Heterologous expression of the Bacillus sp. strain A24 acyl-homoserine lactonase gene aiiA in E. amylovora abolished induction of AHL biosensors, impaired extracellular polysaccharide production and tolerance to hydrogen peroxide, and reduced virulence on apple leaves.

Bacteria commonly control expression of gene circuits in a population-dependent manner via a regulatory mechanism known as quorum sensing (30, 50). At the core of this process are self-produced, low-molecular-weight signal molecules referred to as autoinducers, which, when present at concentrations at or above intrinsic threshold concentrations, trigger cognate transcriptional effectors to activate quiescent genes or, in some cases (e.g., EsaR in Pantoea stewartii), repress target gene expression (48). Gram-negative bacteria typically produce N-acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) chemical signals (26). The first quorum-sensing system was identified in the luminescent marine symbiont Vibrio fischeri, and this system is controlled by LuxI, the enzyme responsible for synthesis of the pheromone N-3-oxohexanoyl-l-homoserine lactone, and LuxR, the transcriptional activator that recognizes this specific AHL (8, 17). AHL-mediated quorum sensing has since been found to govern a myriad of vital processes in pathogenic and beneficial bacteria (33, 37, 48, 52). AHL signals are required for conjugal transfer of the tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid in phytopathogenic Agrobacterium tumefaciens, for antibiotic biosynthesis in plant-beneficial Pseudomonas chlororaphis, for nodulation factors in Rhizobium leguminosarum, and for synthesis of exoenzyme virulence factors in Erwinia carotovora, just to name a few of these processes (11, 22, 23, 49).

Understanding autoinduction in pathogenic bacteria enables us to pursue signal inactivation or degradation as a new approach to sustainable disease control (35). A few plant and microbial compounds, such as AHL-degrading proteins produced by rhizosphere bacteria, have been reported to have such activity against AHLs (43). The first application of autoinducer quenching for the purpose of disease control involved aiiA, a Bacillus gene encoding AHL lactonase (29), which was expressed in transgenic tobacco and potato plants in order to block AHL-mediated virulence genes of phytopathogenic E. carotovora and to increase plant resistance (14, 15, 28). A similar approach that has been pursued recently to avoid the controversial release of transgenic organisms involves the application of natural AHL-degrading bacteria to plant systems for preventive and curative biological control of diseases (34).

Despite being closely related to E. carotovora, a well-characterized AHL-producing phytopathogen (51), Erwinia amylovora has been absent from lists of bacteria with known autoinduction systems (37, 48). E. amylovora causes fire blight, one of the most devastating and difficult-to-control diseases of apple, pear, and related members of the Rosaceae worldwide (25, 44). Current controls are essentially limited to exclusion measures (i.e., quarantine and eradication), which are exceedingly costly, and to antibiotics (i.e., streptomycin and tetracycline), which are banned from plant agricultural use in Europe and many other regions (44). In an effort to understand the biology of fire blight and to develop effective and practical controls, multiple traits critical for pathogenicity have been identified; these traits include the extracellular polysaccharides amylovoran and levan (24, 45), Hrp proteins (5), and tolerance to the oxidative bursts typical of host defense responses partially conferred by the hydroxamate siderophore desferrioxamine (13, 46). To date, however, no mechanism has been identified that enables this highly successful pathogen to coordinate expression of these distinct genetic factors involved in plant attack (16).

In this report, we present several lines of evidence for AHL-mediated autoinduction in E. amylovora. The presence of a putative AHL signal was detected by cross-feeding AHL-sensitive A. tumefaciens and Vibrio harveyi biosensors with live cultures or cell-free filtrates of E. amylovora. E. amylovora was found to carry luxI and luxR homologous genes and to have a signature lux box in many of its essential virulence genes. A transgenic E. amylovora model constructed to express the specific AHL lactonase gene aiiA from Bacillus sp. strain A24 (39) was diminished in extracellular polysaccharide biosynthesis, tolerance to hydrogen peroxide, and development of symptoms on apple leaves.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were routinely cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) or AB medium (20) with appropriate antibiotics.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens A334 | Crown gall pathogen, AHL producer | 34 |

| A. tumefaciens NTL4/pZLR4 | AHL biosensor strain producing β-galactosidase activity in the presence of exogenous AHL, Gmr (30) | 31 |

| Chromobacterium violaceum CV026 | Double mini-Tn5 mutant derived from ATCC 31532, AHL biosensor, produces violacein pigment only in the presence of exogenous AHL, Kmr (20) | 32 |

| Erwinia amylovora Ea02 | Wild type isolated in Vollèges, Switzerland | This study |

| E. amylovora Ea02/pUC21 | Ea02 derivative transformed with the pUC21 vector plasmid | This study |

| E. amylovora Ea02/pAiiA | Ea02 derivative transformed with the pAiiA plasmid | This study |

| Erwinia carotovora 852 | Potato soft rot pathogen, AHL producer | 34 |

| Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL 1391 | Biocontrol agent producing AHL | 12 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 | Biocontrol agent, does not produce AHL | 42 |

| Vibrio harveyi BB886 | Biosensor for AHL type autoinducers, Tcr (10) | 1 |

| V. harveyi BB120 | Wild type | 1 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pME6000 | Cloning vector, Tcr (50) | 39 |

| pME6863 | pME6000 carrying the aiiA gene from Bacillus sp. strain A24 under constitutive Plac promotion, Tcr (50) | 39 |

| pUC21 | Cloning vector, Apr (80) | 47 |

| pAiiA | pUC21 derivative carrying Plac::aiiA from pME6863, Apr (80) | This study |

Apr, Gmr, Kmr, and Tcr, resistance to ampicillin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and tetracycline, respectively. The numbers in parentheses indicate the concentrations of antibiotics (in micrograms per milliliter) to which the organism or plasmid is resistant.

Autoinducer cross-feeding assays.

Live cultures of the test strain E. amylovora Ea02 were coinoculated with the AHL biosensor strains A. tumefaciens NTL4/pZLR4 and Chromobacterium violaceum CV026 onto LB agar plates. Ten microliters of a 2% X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) solution was added to the A. tumefaciens treatments. AHL production was determined after 3 days of cross-feeding by observing a change in the colony color to blue in A. tumefaciens cultures (31), resulting from lacZ expression, and to purple in C. violaceum cultures (32), resulting from production of the natural pigment violacein. Other test strains were wild-type strains of each biosensor species that were used as positive controls and the non-AHL-producing soil bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 (42) that was used as a negative control.

Cell-free filtrates (150 μl) from stationary-phase cultures (16 h, 30°C) of Ea02 and other test strains were combined with 150 μl of a stationary-phase culture of A. tumefaciens NTL4/pZLR4, and the resulting mixture was grown on LB medium with X-Gal. Cross-feeding of the biosensor was determined by observing a change in the colony color to blue over the course of 3 days. Test strain cell-free filtrates were also combined with a 1:1,000 dilution of an overnight AB medium culture of the V. harveyi BB886 AHL biosensor (20) to obtain a final concentration of test strain filtrate of 10%. Aliquots (20-μl drops) of this mixture were spotted onto filter paper, covered by Hyperfilm and an autoradiography plate (ECL; Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom), and incubated for 8 h. Cross-feeding of V. harveyi was determined by light emission (20). Crude AHL extracts were made from overnight cultures of wild-type E. carotovora, A. tumefaciens, and P. chlororaphis and 72-h cultures of E. amylovora. Bacteria were grown in 200 ml of LB broth at 27°C. Cultures were centrifuged at 4°C and 9,300 × g for 10 min, the supernatants were filtered to remove the cells, and AHL was recovered by using the methods of McClean et al. (32).

DNA procedures.

Plasmid DNA was isolated by the alkaline lysis method with a QIAprep spin plasmid minipreps kit (QIAGEN). Total DNA was isolated by the method of Ramos-González and Molin (38), except that the 30-min incubation step at 55°C was omitted. DNA digestion with restriction enzymes, ligation, and transformation were performed by standard procedures (40). PCRs were performed by using the chromosomal DNA of E. amylovora Ea02, P. fluorescens CHA0, and E. carotovora 852 as templates. Primers AHLea-for (5′AGTATGGGTAAAACCTA-3′) and AHLea-rev (5′-TAAAACGTTCTGGTTGG-3′) were designed based on known AHL gene sequences. Each 20-μl reaction mixture included 1 μl of chromosomal DNA, 2 μl of 10× Taq buffer, 1 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide, 1 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (2.5 μM), 0.4 μl of primer (10 μM), and 0.5 μl of Taq polymerase. The cycles used were one cycle of 3 min at 94°C, 35 cycles of 1 min at 92°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C, and one cycle of 10 min at 72°C with a PTC-100 thermocycler (MJ Research, Waltham, Mass.). DNA sequencing was done with a Perkin-Elmer ABI Prism automated sequencer with a fluorescent dye-labeled dideoxy terminator. The sequence obtained was analyzed by using a BLAST search and the Multiple Sequence Alignment by Florence program of INRA (French National Institute of Agricultural Research).

AHL-degrading E. amylovora model.

A model system for intrinsic degradation of autoinducer was created as previously described (34), except that a more efficient plasmid vector was used (39).

Virulence factor assays.

The amylovoran concentrations in supernatants of LB medium cultures supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) sorbitol were determined by using a turbidity assay with acetylpyrimidinium chloride as described previously (3). The levansucrase activities in supernatants of LB medium cultures were determined as described previously (4, 10). Cultures were removed, and the supernatants from 1-ml aliquots were diluted with the same volume of assay buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, 2 M sucrose, and 0.05% sodium azide to prevent further bacterial growth. The mixtures were incubated for 16 to 24 h at 28°C, and the turbidity characteristic of levan formation was quantified photometrically at 580 nm. Tolerance to free radicals was evaluated by challenging E. amylovora with peroxide and dichloromethane as previously described (46). Different concentrations of H2O2 (0 to 10 μM), dichloromethane (0.1%, vol/vol), or dichloromethane extracts of cultures of E. amylovora, A. tumefaciens, P. fluorescens CHA0, E. carotovora, and P. fluorescens (final concentration of dichloromethane, 0.1% [vol/vol]) were added to early-logarithmic-phase cultures of E. amylovora (optical density at 600 nm, 0.25). The turbidities of these cultures were measured 12 h after addition of the compounds mentioned above. Six independent repetitions were performed.

Pathogenicity assay.

Detached leaves of the apple variety ‘Golden Delicious’ were inoculated at the petiole base with 20 μl of either saline or saline containing an E. amylovora cell suspension (108 CFU/ml). The leaves were kept physiologically intact by placing them on moistened filter paper in petri dishes sealed with Parafilm. After 7 days of incubation at 27°C in a growth chamber with a 16-h photoperiod, disease symptoms were measured on a scale of severity from 0 to 4, where 0 is no symptoms, 1 is the necrotic zone limited to the leaf petiole, 2 is the necrotic zone extended to the first leaf vein, 3 is the necrotic zone extended to the second leaf vein, and 4 is the necrotic zone extended beyond the second leaf vein. Noninoculated controls remained asymptomatic and vigorous throughout the experiments. Each treatment consisted of eight detached leaves in three independent trials over time.

RESULTS

Detection of quorum-sensing signal molecules in culture supernatants of E. amylovora.

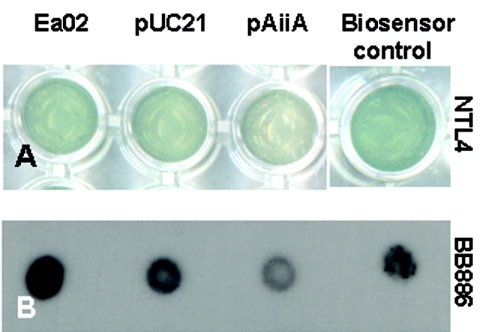

Culture supernatants of wild-type E. amylovora induced the β-galactosidase activity of the 3-oxo and 3-hydroxy AHL derivative biosensor A. tumefaciens NTL4/pZLR4 when they were added to solid or liquid LB medium (Fig. 1A). Also, stimulation of light production by V. harveyi BB886 (Fig. 1B), the specific N-(3-hydroxybutanoyl)-homoserine lactone (autoinducer type I) reporter, was observed when this strain was cultured in AB medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) E. amylovora culture supernatant (Fig. 1B). However, no induction of AHL-mediated violacein production was observed when E. amylovora was coinoculated with C. violaceum CV026, a biosensor sensitive to short-chain AHLs (data not shown). These observations suggested that E. amylovora produces a signaling molecule that is an AHL molecule related to the V. harveyi type autoinducer.

FIG. 1.

Autoinducer production by E. amylovora and autoinducer degradation in a derivative strain carrying the aiiA acyl-homoserine lactonase-encoding gene. Production of autoinducer molecules was detected in cultures of the autoinducer biosensor strains A. tumefaciens NTL4/pZLR4 (A) and V. harveyi BB886 (B) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) cell-free culture supernatants of E. amylovora Ea02 (Ea02); the transconjugant control strain E. amylovora EA02/pUC (pUC21); a transconjugant carrying the lactonase gene, Ea02/pAiiA (pAiiA); or the AHL-positive producing strain A. tumefaciens A334 or the reporter control BB220 (spot on the right in panel B). Autoinducer production was revealed by the appearance of a blue color resulting from β-galactosidase activity in the NTL4/pZLR4 AHL biosensor or by an increase in the intensity of black spots visualized after autoradiography to detect light emission by the Vibrio autoinducer biosensor strain. Degradation of the AHL autoinducer produced by E. amylovora was determined by detection of a decrease in either biosensor reaction.

Genetic evidence for quorum sensing in E. amylovora: characterization of the E. amylovora eamIR and luxS loci.

We used PCR primers based on a comparison of the expIR, echIR, and yenIR sequences from E. carotovora, Erwinia chrysanthemi, and Yersinia enterocolitica (GenBank accession numbers X72891, U45854, and AJ414030) to amplify a 350-bp DNA fragment of the E. amylovora genome containing part of an open reading frame (′eamI) highly homologous to genes encoding an AHL synthase and a partial open reading frame (′eamR) highly homologous to genes encoding an AHL-binding transcriptional activator protein. This DNA fragment exhibited 75 to 95% identity with the hslRI and expRI (E. carotovora), echRI, expRI, and ahlIR (E. chrysanthemi), and yenRI (Y. enterocolitica and Yersinia ruckeri) loci. Like the expI, esaI, and yenI loci, the known sequences of the eamI and eamR genes are convergently oriented, overlapping by 18 bp at the end of both open reading frames. We also detected lux motifs upstream of E. amylovora genes responsible for the regulation of important pathogenicity-related cellular functions, including the ams operon, sorM, sorL, hrpL, and foxR. The lux sequences are similar to the 20-bp inverted repeat region that has been found in promoter regions of genes directly inducible by quorum-sensing signals in Pseudomonas stewartii, P. putida, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. fluorescens, and Pseudomonas syringae (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Lux-box-like sequences in E. amylovora

| Lux box sequencea | AHL-regulated gene | Phenotype | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACCTGGCAGCCTGAGCTGCCAGG | E. amylovora srlMR | Regulators of sorbitol uptake | Y14603 |

| TCCTGGCAACAAGTTGCCAGA | E. amylovora hrpL | Regulator of secretion system type III | AF083877 |

| GGCCTGATTAATCGAGGCCG | E. amylovora foxR | Desferrioxamine receptor | AJ223062 |

| CCTGGCTTATAGCTGCCAAT | E. amylovora ams | Amylovoran synthesis genes | X77921 |

| ACCTGCACTATAGGTACAGGC | P. stewartii esaI | AHL synthase | L32183 |

| ACCTCCCTGTTCTGGGAGGT | P. putida ppuA | Possible chain fatty acid coenzyme A ligase | A4115588 |

| ACCTGCCAGTTCTGGTAGGA | P. putida ppuI | AHL synthase | A4115588 |

| ACCTGCCAGTTCTGGCAGGT | P. aeruginosa lasB | Protease (pseudolysin) precursor gene | AB029328 |

| CCCTACCAGATCTGGCAGGT | P. aeruginosa rhlI | Autoinducer synthase | U40458 |

| ACCTACCAGAATTGGCAGGG | P. aeruginosa hcnA | Cyanide synthase | AE0046446 |

| ACCTGTACTTAGGTGCAGGT | P. fluorescens afmI | AHL synthase | AF232768 |

| ACCTGACCTTTCGGTCAGGT | Serratia marcescens spnI | AHL synthase | AF389912 |

| TACCTGTTCCTAGGTACAGTA | P. syringae psmI | AHL synthase | AF2344628 |

Boldface type indicates bases with more than 50% homology among the various sequences.

Impact of heterologous expression of acyl-homoserine lactonase on E. carotovora autoinducer phenotypes.

Plasmid pME6863 was cut with the AgeI and EcoRI restriction enzymes to obtain the fragment containing the aiiA gene under control of the constitutive promoter Plac. This fragment was cloned into the vector plasmid pUC21 to obtain pAiiA. This plasmid was introduced into E. amylovora Ea02 to obtain Ea02/pAiiA. Ea02 carrying the vector without aiiA, Ea02/pUC21, was constructed for use as a non-AHL-degrading control. Inactivation of the autoinducer produced by E. amylovora was evaluated by using A. tumefaciens NTL4/pZLR4 and V. harveyi BB886 as autoinducer type I biosensors. The β-galactosidase activity of NTL4/pZLR4 (Fig. 1A) and the light emission of BB886 (Fig. 1B) were drastically reduced when these biosensor strains were incubated overnight in the presence 10% Ea02/pAiiA supernatants. No effect was observed when the strains were incubated with wild-type Ea02 or Ea02/pUC21 supernatants (Fig. 1).

EPS production by E. amylovora is cell density dependent.

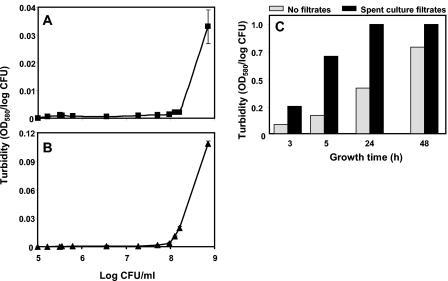

A general feature of quorum-sensing-regulated phenotypes is that their expression is cell density dependent. The amount of amylovoran produced (Fig. 2A) and the activity of the levansucrase enzyme critical to biosynthesis of the cationic extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) levan (Fig. 2B) were cell density dependent. Cultures were inoculated by using 105 CFU/ml and were grown for 15 to 24 h to obtain densities between 1× 108 and 8 × 108 CFU/ml. The results are summarized in Fig. 2, which shows that strain Ea02 produced a small quantity of the acidic EPS during the early stages of growth; also, a little levansucrase activity was measured in the culture supernatants. After the cell density reached approximately 2 × 108 to 3 × 108 CFU/ml, the EPS production and levansucrase activity were 15 to 20 times greater than the EPS production and levansucrase activity at a cell density of 1 × 108 CFU/ml. Levansucrase activity was prematurely induced during the exponential growth phase by the addition of spent culture filtrates (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

(A and B) Acidic EPS production and levansucrase activity of E. amylovora are cell density dependent. E. amylovora was cultured in LB medium supplemented with 1% sorbitol, and 2-ml samples of the cultures were taken at different times and centrifuged. Aliquots (0.75 ml) of culture supernatant were used to determine the production of acidic EPS (A), and the same quantity was used to determine the levansucrase activity (B). The values are the averages of three experiments. The error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means. (C) Addition of cell-free filtrates of spent cultures to LB medium resulted in premature production of levansucrase. OD580, optical density at 580 nm.

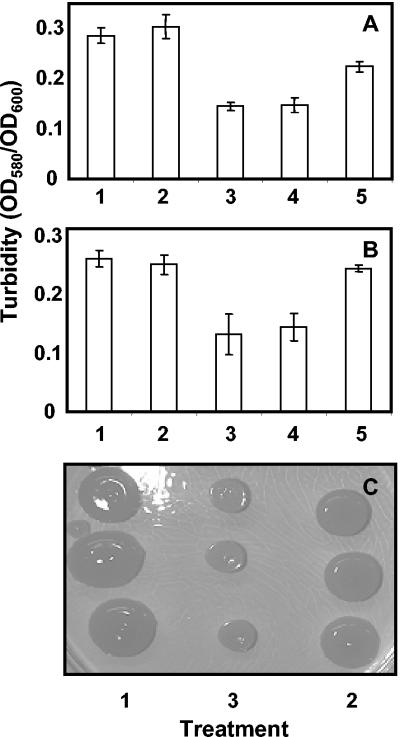

Effects of AHL breakdown on EPS production by E. amylovora.

EPS synthesis was affected by inactivation of its autoinducer molecule. The amounts of amylovoran (Fig. 3A) and levansucrase (Fig. 3B) were significantly less in the culture supernatants of Ea02/pAiiA than in the supernatants of wild-type strain Ea02 or the transconjugant control Ea02/pUC21. When dichloromethane extracts, which solubilized AHL, were added to cultures, EPS production was stimulated (Fig. 3). Extracellular polysaccharide production was noticeably reduced in Ea02/pAiiA on agar plates compared to the production in the wild-type or transconjugant control (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Effects of quorum-sensing alteration of EPS production by E. amylovora. (A and B) The levels of acidic EPS (A) or levansucrase activity (B) were measured in supernatants of cultures of E. amylovora Ea02 (bar 1), the transconjugant control Ea02/pUC21 (bar 2), or the transconjugant expressing the lactonase gene Ea02/pAiiA (bar 3) or in supernatants of cultures of E. amylovora supplemented with dichloromethane (bar 4) or after dichloromethane autoinducer extraction from cultures of E. amylovora (bar 5) as described in Materials and Methods. (C) EPS production by E. amylovora and its derivatives was also observed after growth on LB medium plates containing 5% (wt/vol) sucrose. The values are means of six trials with three treatment replications per trial. The error bars indicate standard deviations of the means. OD580 and OD600, optical densities at 580 and 600 nm, respectively.

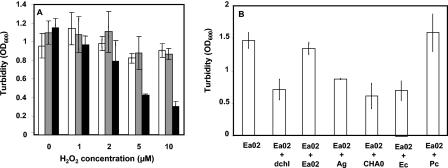

Effects of altering quorum sensing on the tolerance to peroxide and dichloromethane.

The ability of E. amylovora to survive in the presence of an oxidative stress is a virulence trait. Effectively, the expression of the lactonase gene in Ea02/pAiiA decreased survival in the presence of H2O2 compared with the survival of the wild type or control strain Ea02/pUC21. Significant decreases in survival were inversely proportional to the oxidant concentration and were evident at H2O2 concentrations as low as 5 mM (Fig. 4A). E. amylovora was cultured in the presence of dichloromethane, the organic solvent used for extraction of the type I autoinducer molecules. The growth of E. amylovora was reduced threefold by a dichloromethane concentration of 0.1% (vol/vol). This reductive effect on the turbidity of E. amylovora cultures disappeared in the presence of the same concentration of the organic solvent when it was used to extract the autoinducer molecule of Ea02 supernatants. The same effect was observed when the solvent was added prior to extraction of the autoinducer molecules produced by P. chlororaphis PCL1391. Addition of the type I autoinducer molecules extracted with dichloromethane in A. tumefaciens and E. carotovora culture supernatants did not affect the growth pattern compared to addition of the organic solvent alone. The pattern was the same in the case of addition of a dichloromethane extract of P. fluorescens CHA0 supernatants lacking any autoinducer (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Effect of quorum sensing on the growth of E. amylovora in the presence of oxidative radicals (oxygen peroxide) and an organic solvent (dichloromethane). (A) Growth of E. amylovora Ea02 (open bars), control transconjugant derivative Ea02/pUC21 (grey bars), or a derivative expressing the lactonase gene, Ea02/pAiiA (solid bars), was measured in cultures with different concentrations of H2O2 as described in Materials and Methods. Tolerance to free oxygen radicals is a hallmark virulence trait of E. amylovora. (B) Growth of Ea02 was also measured in the presence of 0.1% (vol/vol) dichloromethane (Ea + dchl) or dichloromethane-containing autoinducer extracts from Ea02 (Ea02 + Ea02), A. tumefaciens A334 (Ea02 + Ag), P. fluorescens CHA0 (Ea02 + CHA0), E. carotovora 852 (Ea02 + Ec), and P. chlororaphis PCL1391 (EA02 + Pc). Dichloromethane was included as a control since it was the extraction solvent used for autoinducer recovery. The values are the means of six trials with three treatment replications per trial. The error bars indicate standard deviations of the means. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

Production of AHL contributes to symptom expression in apple leaves.

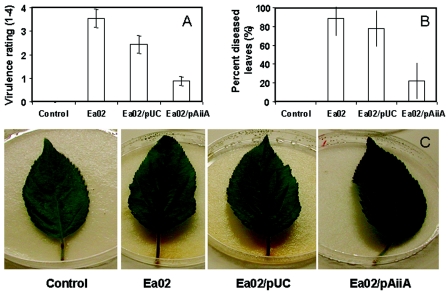

Pathogenicity tests conducted with leaves of ‘Golden Delicious’ apple demonstrated that Ea02/pAiiA expressing the AHL-degrading protein AiiA had diminished virulence in terms of symptom severity (Fig. 5A) and incidence (Fig. 5B). Necrotic symptoms typical of fire blight developed along the main veins of leaves challenged with the wild-type or the transconjugant control strain Ea02/pUC21 (Fig. 5C) but were absent on nonchallenged leaves. Only very slight discoloration was observed at the base of leaves challenged with E. amylovora expressing aiiA.

FIG. 5.

Virulence attenuation in E. amylovora with heterologous expression of the Bacillus sp. strain A24 acyl-homoserine lactonase gene, aiiA. ‘Golden Delicious’ apple leaves were inoculated with saline (Control), with the wild-type pathogen (Ea02), or with one of its derivatives expressing aiiA (Ea02/pAiiA) or carrying the vector plasmid without aiiA (Ea02/pUC). The virulence severity (A) and disease incidence (B) were determined after 7 days of incubation. The development of symptoms observed in wild-type- and transconjugant control-challenged leaves consisted of leaf vein discoloration and necrosis that is typical of fire blight (C). The values are the means of eight trials with three replicates per trial. The error bars indicate standard deviations of the means.

DISCUSSION

We obtained genetic and phenotypic evidence of the existence of quorum sensing in E. amylovora. This phytopathogenic bacterium produces an autoinducer molecule with characteristics of an AHL typical of gram-negative bacteria (6). AHL production was first detected by using standard A. tumefaciens and V. harveyi type autoinducer biosensor strains. A previous survey of plant-associated bacteria for autoinducers in which the A. tumefaciens biosensor was used failed to detect any such molecules in three North American isolates of E. amylovora. Cha et al. (9) used 5-ml late-stationary- to early-exponential-phase cultures and found even among Agrobacterium spp. isolates that reaction elicitation in the sensitive biosensor was often weak. Other laboratories have also recently discovered AHL production in P. putida (41) and Agrobacterium vitis (53) that was not detected by Cha et al. (9). Our success in detecting AHL production in E. amylovora may have been due to our use of large-volume, late-stationary-phase cultures and more efficient extraction methods (39). Indeed, when we first tried using methods identical to those of Cha et al. (9), we found that E. carotovora produced intense reactions but that we missed signals from E. amylovora. E. amylovora signals were detected when the culture age was increased and we used late-log-phase cultures or added spent culture filtrates to prematurely induce enzyme activity. Sequence analysis of PCR products confirmed the presence of luxI and luxR homologues (27), which were designated the putative AHL synthesis gene eamI and the putative activator gene eamR. These genes have a high degree of homology with luxI-luxR-related genes in plant- and animal-pathogenic bacteria (i.e., the expI-expR, hslI-hslR, and carI genes of E. carotovora, the echI-echR and expI-expR genes of E. chrysanthemi, and the yenI-yenR genes of Y. enterocolitica and Y. ruckeri).

AHL in E. amylovora appears to contribute to the expression of virulence factors and symptom development, which is similar to the role that AHLs play in other plant-pathogenic bacteria, such as the closely related organisms E. carotovora, E. chrysanthemi, and P. stewartii (51, 52). For example, density-dependent signaling and AHL are involved in synthesis of two key EPS, amylovoran and levan (by way of levansucrase activity) (4, 21). Wild-type E. amylovora produces appreciable amounts of EPS only after the concentration reaches 2 × 108 CFU/ml, which is similar to observations for stewartan production in P. stewartii (48). Addition of spent cultures or culture extracts increased EPS production in E. amylovora. Moreover, heterogeneous expression of the Bacillus sp. strain A24 acyl-homoserine lactonase gene aiiA in E. amylovora greatly diminished EPS production by the pathogen. EPS synthesis was not affected in E. amylovora carrying the vector plasmid without aiiA. This is a novel approach to identifying new systems with AHL signaling, but it is an approach that has precedence in the work of Dong et al. (15) and Reimmann et al. (39), who used heterologous expression of aiiA in E. carotovora and P. aeruginosa, respectively, to demonstrate AHL involvement in virulence factor gene expression in these pathogens. Using this model system, we further demonstrated that AHL production contributes to tolerance of active oxygen species in E. amylovora, a critical trait for survival in infected host plants that produce oxidative bursts (46). AHL also enhances tolerance to organic solvents in E. amylovora. It is likely that the reduced tolerance to active oxygen species is the result of less EPS that protects cells from environmental stress. It remains to be determined if AHL modulates expression of other factors that regulate oxidative burst tolerance, such as the ferrioxamine siderophore (13) or the Hrp elicitor (36). We identified signature lux motifs in genes for these and other virulence factors in E. amylovora. For example, a 20-bp repeated and inverted DNA sequence was found in the ams operon promoter region for amylovoran synthesis (7). Finally, the aiiA model indicated that AHL plays a role in symptom development in apple. One of the trademark symptoms used to diagnose fire blight in the field is the development of black necrosis progressing out of the leaf veins. The aiiA-expressing E. amylovora strain was not able to induce such symptoms in apple leaves. Recent findings presented by Friscina et al. (18) corroborate our evidence that there is AHL-mediated autoinduction in E. amylovora.

Fire blight caused by E. amylovora is arguably the most economically severe disease of pome fruits because of direct damage to, and often total loss of, orchards and also because of the high costs for monitoring, exclusion, and eradication worldwide. Added to these costs are incalculable ecological costs to wild species like hawthorn and to loss of old-growth fruit tree (Hochstämme) ecosystems highly prized as biodiversity islands and sources of cider fruit throughout central Europe. Control strategies are currently limited for the most part to exclusion and eradication, which are costly and useful primarily in the relatively few fire blight-free zones worldwide, to antibiotics such as streptomycin, which are banned in most parts of Europe, to resistance breeding, which has not yielded any strongly resistant commercial varieties to date, and to biocontrol, which relies on nutritional competition and growth inhibition. Our discovery of an AHL signal in E. amylovora that has some role in virulence factor expression presents a novel target for designing control strategies to block disease development. Autoinducer degradation engineered into transgenic crops (14) or with natural microbial degraders (27, 34) has been shown recently to hold promise for protecting crops against soft rot-causing E. carotovora. Similar studies with autoinducer-degrading antagonists are now being started for fire blight.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bonnie Bassler for generously providing the Vibrio biosensor, Dieter Haas for providing the Agrobacterium and Chromobacterium biosensors, and Olivier Cazelle for providing wild-type E. amylovora Ea02.

Financial support was provided in part by the European Union ECO-SAFE Project (grant QLK3-CT-2000-31759/OFES 00.0164-2) and by Swiss Federal Office for Agriculture (BLW) project 04.24.3.3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassler, B. L., E. P. Greenberg, and A. M. Stevens. 1997. Cross-species induction of luminescence in the quorum-sensing bacterium Vibrio harveyi. J. Bacteriol. 179:4043-4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellemann, P., and K. Geider. 1992. Localisation of transposon insertions in pathogenicity mutants of Erwinia amylovora and their biochemical characterisation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:931-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellemann, P., S. Bereswill, S. Berger, and K. Geider. 1994. Visualization of capsule formation by Erwinia amylovora and assays to determine amylovoran synthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 16:290-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bereswill, S., and K. Geider. 1997. Characterization of the rcsB gene from Erwinia amylovora and its influence on exopolysaccharide synthesis and virulence of the fire blight pathogen. J. Bacteriol. 179:1354-1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogdanove, A. J., Z. Wei, L. Zhao, and S. V. Beer. 1996. Erwinia amylovora secretes harpin via a type III pathway and contains a homologue of yopN of Yersinia spp. J. Bacteriol. 178:1720-1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brelles-Marino, G., and E. J. Bedmar. 2001. Detection, purification and characterisation of quorum-sensing signal molecules in plant-associated bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 91:197-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bugert, P., and K. Geider. 1995. Molecular analysis of the ams operon required for exopolysaccharide synthesis of Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Microbiol. 15:917-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao, J. G., and E. A. Meighen. 1989. Purification and structural identification of an autoinducer for the luminescence system of Vibrio harveyi. J. Biol. Chem. 264:21670-21676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cha, C., P. Gao, Y.-C. Chen, P. D. Shaw, and S. K. Farrand. 1998. Production of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals by Gram-negative plant-associated bacteria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:1119-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambert, R., G. Treboul, and R. Dedonder. 1974. Kinetic studies of levansucrase of Bacillus subtilis. Eur. J. Biochem. 41:285-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, H., M. Teplitski, J. B. Robinson, B. G. Rolfe, and W. D. Bauer. 2003. Proteomic analysis of wild-type Sinorhizobium meliloti responses to N-acyl homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals and the transition to stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 185:5029-5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chin-A-Woeng, T. F. C., G. V. Bloemberg, A. J. van der Bij, K. M. G. F. van der Drift, J. Schripsema, B. Kroon, R. J. Scheffer, C. Keel, P. A. H. M. Bakker, H. Tichy, F. J. V. de Bruijn, J. E. Thomas-Oates, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 1998. Biocontrol by phenazine-1-carboxamide-producing Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL1391 of tomato root rot caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:1069-1077. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dellagi, A., M.-N. Brisset, J.-P. Paulin, and D. Expert. 1998. Dual role of desferrioxamine in Erwinia amylovora pathogenicity. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:734-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong, Y. H., A. R. Gusti, Q. Zhang, J. L. Xu, and L. H. Zhang. 2002. Identification of quorum-quenching N-acyl homoserine lactonases from Bacillus species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1754-1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong, Y. H., L. H. Wang, J. L. Xu, H. B. Zhang, X. F. Zhang, and L. H. Zhang. 2001. Quenching quorum-sensing-dependent bacterial infection by an N-acyl homoserine lactonase. Nature 411:813-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eastgate, J. A. 2000. Erwinia amylovora: the molecular basis of fireblight disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1:325-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engebrecht, J., K. Nealson, and M. Silverman. 1983. Bacterial bioluminescence: isolation and genetic analysis of functions from Vibrio fischeri. Cell 32:773-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friscina, A., C. Aguilar, C. Venuti, G. Degrassi, V. Venturi, and U. Mazzucchi. 2004. Acyl homoserine lactone autoinducers are produced by Erwinia amylovora strains isolated in Italy, p. 86. Abstr. Book, 10th Int. Workshop Fire Blight, Bologna, Italy, 5-9 July 2004.

- 19.Fuqua, C., M. R. Parsek, and E. P. Greenberg. 2001. Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:439-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg, E. P., J. W. Hastings, and S. Ulitzur. 1979. Induction of luciferase synthesis in Beneckea harveyi by other marine bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 120:87-91. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross, M., G. Geier, K. Rudolph, and K. Geider. 1992. Levan and levansucrase synthesized by the fireblight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 40:371-381. [Google Scholar]

- 22.He, X., W. Chang, D. L Pierce, L. O. Seib, J. Wagner, and C. Fuqua. 2003. Quorum sensing in Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 regulates conjugal transfer (tra) gene expression and influences growth rate. J. Bacteriol. 185:809-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heurlier, K., V. Denervaud, G. Pessi, C. Reimmann, and D. Haas. 2003. Negative control of quorum sensing by RpoN (σ54) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 185:2227-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwabuchi, N., M. Sunairi, M. Urai, C. Itoh, H. Anzai, M. Nakajima, and S. Harayama. 2002. Extracellular polysaccharides of Rhodococcus rhodochrous S-2 stimulate the degradation of aromatic components in crude oil by indigenous marine bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2337-2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson, K. B., and V. O. Stockwell. 1998. Management of fire blight: a case study in microbial ecology. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 36:227-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleerebezem, M., L. E. Quadri, O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1997. Quorum sensing by peptide pheromones and two-component signal-transduction systems in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 24:895-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo, A., N. V. Blough, and P. V. Dunlap. 1994. Multiple N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone autoinducers of luminescence in the marine symbiotic bacterium Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 176:7558-7565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leadbetter, J. R., and E. P. Greenberg. 2000. Metabolism of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals by Variovorax paradoxus. J. Bacteriol. 182:6921-6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, S. J., S. Y. Park, J. J. Lee, D. Y. Yum, B. T. Koo, and J. K. Lee. 2002. Genes encoding the N-acyl homoserine lactone-degrading enzyme are widespread in many subspecies of Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3919-3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loh, J., E. A. Pierson, L. S. Pierson, G. Stacey, and A. Chatterjee. 2002. Quorum sensing in plant-associated bacteria. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5:285-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo, Z. Q., S. Su, and S. K. Farrand. 2003. In situ activation of the quorum-sensing transcription factor TraR by cognate and noncognate acyl-homoserine lactone ligands: kinetics and consequences. J. Bacteriol. 185:5665-5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McClean, K. H., M. K. Winson, L. Fish, A. Taylor, S. R. Chhabra, M. Camara, M. Daykin, J. H. Lamb, S. Swift, B. W. Bycroft, G. S. Stewart, and P. Williams. 1997. Quorum-sensing and Chromobacterium violaceum: exploitation of violacein production and inhibition for the detection of N-acylhomoserine lactones. Microbiology 143:3703-3711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller, M. B., and B. L. Bassler. 2001. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:165-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molina, L., F. Constantinescu, L. Michel, C. Reimmann, B. Duffy, and G. Défago. 2003. Degradation of pathogen quorum-sensing molecules by soil bacteria: a preventive and curative biological control mechanism. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 45:71-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newton, J. A., and R. G. Fray. 2004. Integration of environmental and host-derived signals with quorum sensing during plant-microbe interactions. Cell. Microbiol. 6:213-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penaloza-Vazquez, A., G. M. Preston, A. Collmer, and C. L. Bender. 2000. Regulatory interactions between the Hrp type III protein secretion system and coronatine biosynthesis in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Microbiology 146:2447-2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierson, L. S., III, D. W. Wood, and E. A. Pierson. 1998. Homoserine lactone-mediated gene regulation in plant-associated bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 36:207-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramos-González, M. I., and S. Molin. 1998. Cloning, sequencing, and phenotypic characterization of the rpoS gene from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J. Bacteriol. 180:3421-3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reimmann, C., N. Ginet, L. Michel, C. Keel, P. Michaux, V. Krishnapillai, M. Zala, K. Heurlier, K. Triandafillu, H. Harms, G. Défago, and D. Haas. 2002. Genetically programmed autoinducer destruction reduces virulence gene expression and swarming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Microbiology 148:923-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Steidle, A., M. Allesen-Holm, K. Riedel, G. Berg, M. Givskov, S. Molin, and L. Eberl. 2002. Identification and characterization of an N-acylhomoserine lactone-dependent quorum-sensing system in Pseudomonas putida strain IsoF. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6371-6382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stutz, E., G. Défago, and H. Kern. 1986. Naturally occurring fluorescent pseudomonads involved in suppression of black root rot of tobacco. Phytopathology 76:181-185. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uroz, S., C. D'Angelo-Picard, A. Carlier, M. Elasri, C. Sicot, A. Petit, P. Oger, D. Faure, and Y. Dessaux. 2003. Novel bacteria degrading N-acylhomoserine lactones and their use as quenchers of quorum-sensing-regulated functions of plant-pathogenic bacteria. Microbiology 149:1981-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vanneste, J. L. 2000. Fire blight: the disease and its causative agent, Erwinia amylovora. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, Oxon, United Kingdom.

- 45.Vanneste, J. L. 1995. Erwinia amylovora, p. 21-46 In U. S. Singh, R. P. Singh, and K. Kohmoto (ed.), Pathogenesis and host specificity in plant diseases: histopathological, biochemical, genetic and molecular basis, vol. 1. Pergamon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venisse, J. S., G. Gullner, and M. N. Brisset. 2001. Evidence for the involvement of an oxidative stress in the initiation of infection of pear by Erwinia amylovora. Plant Physiol. 4:2164-2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1991. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene 100:189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.von Bodman, S. B. B., W. D. Bauer, and D. L. Coplin. 2003. Quorum sensing in plant pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41:455-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whistler, C. A., and L. S. Pierson III. 2003. Repression of phenazine antibiotic production in Pseudomonas aureofaciens strain 30-84 by RpeA. J. Bacteriol. 185:3718-3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitehead, N. A., A. M. Barnard, H. Slater, N. J. Simpson, and G. P. Salmond,. 2001. Quorum-sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:365-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitehead, N. A., J. T. Byers, P. Commander, M. J. Corbett, S. J. Coulthurst, L. Everson, A. K. Harris, C. L. Pemberton, N. J. Simpson, H. Slater, D. S. Smith, M. Welch, N. Williamson, and G. P. Salmond. 2002. The regulation of virulence in phytopathogenic Erwinia species: quorum sensing, antibiotics and ecological considerations. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 81:223-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wisniewski-Dye, F., and J. A. Downie. 2002. Quorum-sensing in Rhizobium. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 81:397-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng, D., H. Zhang, S. Carle, G. Hao, M. R. Holden, and T. J. Burr. 2003. A luxR homolog, aviR, in Agrobacterium vitis is associated with induction of necrosis on grape and a hypersensitive response on tobacco. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 16:650-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]