Abstract

Increasing age is associated with dysregulated immune function and increased inflammation—patterns that are also observed in individuals exposed to chronic social adversity. Yet we still know little about how social adversity impacts the immune system and how it might promote age-related diseases. Here, we investigated how immune cell diversity varied with age, sex and social adversity (operationalized as low social status) in free-ranging rhesus macaques. We found age-related signatures of immunosenescence, including lower proportions of CD20 + B cells, CD20 + /CD3 + ratio, and CD4 + /CD8 + T cell ratio – all signs of diminished antibody production. Age was associated with higher proportions of CD3 + /CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells, CD16 + /CD3- Natural Killer cells, CD3 + /CD4 + /CD25 + and CD3 + /CD8 + /CD25 + T cells, and CD14 + /CD16 + /HLA-DR + intermediate monocytes, and lower levels of CD14 + /CD16-/HLA-DR + classical monocytes, indicating greater amounts of inflammation and immune dysregulation. We also found a sex-dependent effect of exposure to social adversity (i.e., low social status). High-status males, relative to females, had higher CD20 + /CD3 + ratios and CD16 + /CD3 Natural Killer cell proportions, and lower proportions of CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells. Further, low-status females had higher proportions of cytotoxic T cells than high-status females, while the opposite was observed in males. High-status males had higher CD20 + /CD3 + ratios than low-status males. Together, our study identifies the strong age and sex-dependent effects of social adversity on immune cell proportions in a human-relevant primate model. Thus, these results provide novel insights into the combined effects of demography and social adversity on immunity and their potential contribution to age-related diseases in humans and other animals.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-023-00962-8.

Keywords: Age, Inflammation, Sex-differences, Immunosenescence, Social adversity

Introduction

The average human lifespan has almost doubled over the past century [1], accompanied by an increase in the prevalence of many age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disease, diabetes, arthritis, and cognitive decline [2–5]. As individuals age, there is a disruption in the homeostatic balance between innate and adaptive immunity linked to both increases in age-related disease and susceptibility to infection. This imbalance is reflective of two age-related alterations, namely increased inflammation (“inflammaging”) and a decline in adaptive immune function (“immunosenescence”) [6, 7]; both alterations disrupt the balance between pro-and anti-inflammatory mediators that characterize a healthy immune system. One common metric in which inflammaging and immunosenescence can be assessed is through the measurement of immune cell composition and how it covaries with age [8, 9]. For example, with increasing age, innate immune cells such as monocytes become more active and release drivers of inflammation that include proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α) [10]; Natural Killer cells increases in both frequency and their inflammatory phenotypes [11]; and T regulatory cells – which have a role in controlling inflammation – increase with age, all pointing to the increased inflammatory phenotype of increasing age [12, 13]. Other Cells that are part of the adaptive arm of the immune system also change in frequency with age. For instance, B cells and helper T cells show age-related declines that directly impact long-term immunity, as exemplified by the lower effectiveness of vaccination in older individuals [14]. Further, B cells also experience age-associated decreases in frequencies that ultimately affect antibody affinity [15, 16]; all these phenotypes can contribute to immunosenescence.

Yet these age-related alterations in immunity are not universal in their trajectories across individuals. There is substantial heterogeneity with age; not all individuals age at the same rate or fall victim to the same age-related diseases. For instance, some people become hypertensive in their 30 s, while a 60-year-old may never suffer from this condition. Part of this heterogeneity is due to sex differences in the immune system, which alter the prevalence and onset of age-related diseases. For example, in many species, females mount a stronger immune response with increasing age compared to males [14, 17]. Females also have a stronger age-related increase in inflammatory cells compared to males [18]. Further, in humans, older men are more susceptible to infections, such as leptospirosis, tuberculosis, and hepatitis A, than are women [19].

Heterogeneity in aging can also arise from life experiences, such as exposure to social adversity, which can influence the onset and progression of disease and, ultimately, mortality [20]. Social adversity, which is often associated with low social status, and other social stressors [21, 22], has been linked to accelerated aging as indexed by biomarkers like epigenetic age and telomere attrition [23–25]. There are also broad similarities between the effects of age and social adversity on peripheral immune function [26]. For instance, early life social adversity in humans has been linked to increases in proinflammatory T cells [27] – a characteristic usually seen with increasing age. Further, various adversities and social stressors are associated with a decrease in naïve CD4 T helper cells and an increase in naïve CD8 T cells [28], pointing to how the social environment can shape immunity. However, the extent to which social adversity may be associated with immunity across the lifecourse remains unknown. Social adversity might lead to accelerated aging-related disease onset and death and/or social advantage may confer protection from the effects of aging.

Research in humans has identified a significant effect of the social environment has on human health [29–31]. However, these studies have been difficult to carry out due to the complex and multifaceted nature of human society, which include structural inequities and discrimination, and can vary across cultures. Thus, in humans, it can be difficult to objectively quantify adversities and to disentangle effects of specific components of the social environment given the strong correlations between many sources of adversity. Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), an established non-human primate model, offer a tractable alternative for identifying how and why social experiences impact health and aging. Rhesus macaques exhibit aging trajectories similar to humans, such as decreases in mobility, but compressed into a lifespan 3–4 × times shorter [32]. Aging parallels are also manifested at the molecular level: rhesus macaques and humans show similar age-related alterations in immune cell DNA methylation and gene expression [33]. Rhesus macaques also share many social factors with humans including the expression of affiliative behaviors, despotism, among other behaviors [34], making them an ideal animal model for translational aging research.

In rhesus macaques, exposure to social adversity can be captured by measures of social status (i.e., dominance rank). Social status is acquired differently for males and females [35, 36]: females inherit status from their mothers, while males typically disperse from their natal group and enter a new group where they acquire status through a combination of “queuing” and physical contests [37, 38]. Similar to humans, social status in macaques patterns access to resources, and can impact health and lifespan [39–41]. For instance, low-status macaques experience more conspecific aggression and are therefore more likely to be injured [42], and high-status female macaques can live longer than those with lower status [43]. In addition, social status affects immunity in rhesus macaques; one experimental study showed that social status predicts gene expression patterns in peripheral blood mononuclear cells [44].

Here, we characterized age-related variation in immune cell types, as well as the influence of social adversity and sex on immune cell proportions. To do so, we studied a free-ranging population of rhesus macaques living on the island of Cayo Santiago, Puerto Rico where we were able to simultaneously document age, sex, and social status in a semi-naturalistic social setting with minimal human intervention [45].

Methods

Study population

Cayo Santiago is an island located off the southeastern coast of Puerto Rico inhabited by approximately 1,600 rhesus macaques. The population is managed by the Caribbean Primate Research Center (CPRC) and is the oldest primate field station in the world [46]. Cayo Santiago provides unique research opportunities for behavioral, physiological, demographic, morphological and genomic studies. The Cayo Santiago Field Station has a minimal intervention policy, which means that the animals are not managed medically or reproductively. There are no predators on the island, and senescent phenotypes are commonly observed in this population [33, 47–50]. The animals are direct descendants of rhesus macaques introduced from India in 1938; since 1957 these animals have been continuously monitored [51]. The animals are identified with tattoos and ear notches, and demographic data such as age, sex and pedigree have been collected for decades. During the annual capture and release period, researchers have the opportunity to collect biological and morphological samples with the assistance of CPRC veterinary staff. For the past 15 years, the Cayo Biobank Research Unit has collected detailed behavioral data to combine with the biological samples collected each year. In combination, these data provide the opportunity to test the relationships between the social environment, immune function, and aging.

Blood sampling

We collected whole blood from sedated rhesus macaques over three capture and release periods (n = 96 in October—December 2019, n = 153 in October 2020—February 2021 and n = 120 in October 2021—February 2022). Samples were collected in 6 ml K2 EDTA tubes (Beckton, Dickson and Company, cat #367899). We collected a total of 369 samples (200 from males, 169 from females) from 230 unique individuals (113 males, 117 females; i.e., some animals were sampled across multiple years of the study), spanning the natural lifespan of macaques on Cayo Santiago (mean age = 11.8 years, range 0–28 years; Fig. 1A and B). Fresh blood samples were transported at 4 °C to the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences campus where flow cytometric analysis was performed within 6 h of sample collection.

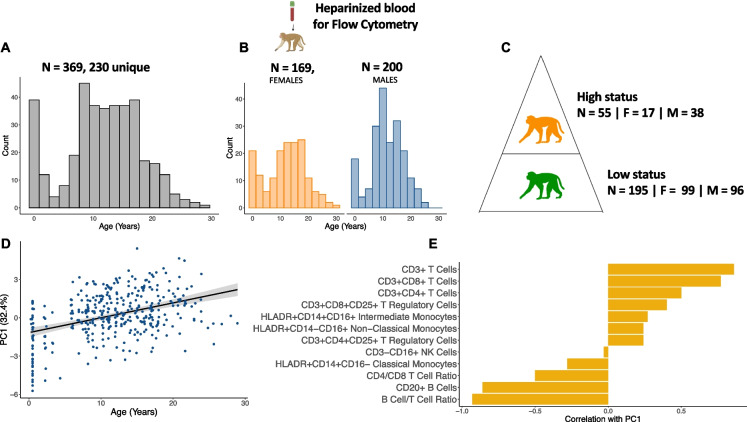

Fig. 1.

Sample collection and demographics. A) We collected 369 whole blood samples from 230 unique individuals across three years, and quantified immune cell proportions using flow cytometry. B) The dataset was roughly balanced between males and females and captured the entire natural lifespan of macaques in this population. C) We calculated social status by assigning dominance ranks to 250 samples using observational data collected in the year before each sample was collected. Animals were assigned to one of three dominance ranks: high, medium, and low. The social status dataset is a subset of the original age dataset because behavioral data were not available for all study animals (i.e., it is not collected for infants and juveniles). D) PC1 of immune cell compositions is significantly associated with age (βPC1 = 0.14, FDR = 7.2 × 10–18). E) The T cell compartment is positively associated with PC1 (and thus age), while the B cell compartment is negatively associated with PC1 of immune cell composition

Antibodies and flow cytometric analysis

An 8-panel antibody cocktail previously validated in rhesus macaques [52–55], consisting of the following antibodies, was used: CD20-PacBlue/Clone 2H7 (Biolegend), CD3-PerCP/Clone SP34-2 (BD), CD4-APC/Clone L200 (BD), CD8-Viogreen/Clone BW135/80 (Miltenyi), CD25-PE/Clone 4E3 (Miltenyi), CD14-FITC/Clone M5E2 (BD), CD16-PEVio770/Clone REA423 (Miltenyi), HLA-DR-APCVio770/Clone REA805 (Miltenyi).

We performed phenotypic characterization of rhesus macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using multicolor flow cytometry with direct immunofluorescence (View Supplementary Fig. 1 for gating strategy and Supplementary Table 1 for Ab panel) on all 369 animals. Aliquots of 150 μl of heparinized whole blood were incubated with a mix of the antibodies described for 30 min at 25 °C (room temperature). After incubation, the red blood cells were fixed and lysed with BD FACS fix and lyse solution (Cat #349202). Cells were washed twice using PBS containing 0.05% BSA at 1,700 RPM for 5 min and processed in a MACSQuant Analyzer 10 flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec, CA).

Lymphocytes and monocytes were gated based on their characteristic forward scatter (measures cells based on their size) and side scatter (measures cells based on their granularity) patterns. Lymphocytes were then further subdivided according to their cell surface markers. Natural killer (NK) cells were defined as the CD3- and CD16 + population; B cells were defined as CD20 + population and T cells as the CD3 + population. We further subdivided T cells from the CD3 + gate into CD4 + and CD8 + populations. CD3 + CD4 + CD25 + and CD3 + CD8 + CD25 + T cells were further gated from the CD4 + and CD8 + gates. Monocytes were gated based on the combined expression of the HLA-DR/CD14 markers for classical monocytes, HLA-DR/CD16 markers for non-classical monocytes, and HLA-DR/CD14/CD16 for intermediate monocytes (Supplementary Fig. 2). Flow cytometry gating was performed using Flowjo version 10.7.1 (FlowJo LLC Ashland, OR).

To obtain an accurate representation of the relative proportions of each individual cell type, we counted only the stained events of the cells of interest and calculated their individual proportions based on the subsets of lymphocytes and monocytes. To calculate cell ratios, such as CD20 + B cell to CD3 + T cell ratio (CD20 + /CD3 + ratio) and CD4 + T cell to CD8 + T cell ratio (CD4 + /CD8 + ratio), we divided the calculated proportion of these cell types in each individual sample (e.g., CD20 + B cell/ CD3 + T cell and CD4 + /CD8 + respectively). (Calculations detailed in Supplementary Table 2).

Quantification of social adversity (social status)

We quantified the social status of a subset of animals for which we had behavioral data (Fig. 1C, n = 250 total samples, 134 from males and 116 from females & n = 145 unique individuals, 73 males and 72 females). We calculated social status (i.e., dominance rank) using the outcomes of win-loss dominance interactions between pairs of same sex adult groupmates. Because of the different routes through which males and females acquire their status, we quantified social status separately for males and females within each group for each year of the study [56, 57]. Observations of adult animals (older than 6 years) were collected from two different social groups, groups V and F, in the year prior to sample collection. In 2019 and 2021, behavioral data were collected using a previously established 10-min focal sampling protocol [35]. Briefly, the protocol consisted of recording state behaviors (e.g., resting, feeding) and agonistic encounters, which included recording the identity of the focal animal and their social partner. Win-loss agonistic interactions included threat and submissive behaviors, along with contact and non-contact aggression. In 2019 and 2021 we also collected additional agonistic interactions ad-libitum. In 2020, all agonistic interactions were collected ad-libitum due to restrictions imposed on behavioral data collection due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In all years, we used known maternal relatedness to settle behavioral gaps in the female hierarchy [58]. To control for variation in group size, social status (i.e., dominance rank) was quantified as the percentage of same-sex adults that an animal outranked in their group. For all analyses, we grouped animals into one of two social status categories: high-rank (> 80% of same-sex adults outranked) and low-rank (< 79% of same-sex adults outranked) [59].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software R version 4.2.3 [60].

First, we performed a principal component analysis of the cell composition data for all samples (n = 369, 230 unique individuals) using the prcomp function of the stats package. Next, we employed a linear additive mixed-effects approach, using the lmer function in the lmerTest package to run sample projections on principal components as a function of age (in years), sex, and sample period—to control for the technical variation in the flow cytometer lasers, which changed over the sampling years (model 1 – Supplementary Table 3) and individual ID as a random effect. We also modeled sample projections on principal components as a function of the interaction between age and sex (age*sex) and sampling period—which will ultimately allow us to identify possible sex-dependent associations with age—and individual ID as a random effect (model 2—Supplementary Table 3).

To evaluate each cell type at a more granular level, we employed the same additive linear mixed-effects to test the proportion of each cell type and certain cell type ratios (e.g., CD4 + /CD8 +) as a function of age, sex, and sample period with individual ID as a random effect (model 3—Supplementary Table 3). Finally, we tested the proportion of each cell type and certain cell type ratios (e.g., CD4 + /CD8 +) as a function of the interaction between age and sex (age*sex) and sampling period with individual ID as a random effect (model 4—Supplementary Table 3).

For the subset of samples in which information on social status was available (n = 250 total samples, 145 unique individuals), we tested for the additive effect of principal component projections as a function of social status, age, sex and sample period, with individual ID and social group as a random effect (model 5—Supplementary Table 3). We also tested for the principal component interaction between status and age (status*age) and between status and sex (status*sex), with individual ID and social group as a random effect (model 6—Supplementary Table 3). We then additively tested the proportion of each cell type and certain cell type ratios as a function of social status, age, sex, and sample period (model 7—Supplementary Table 3). To test whether the relationship between the proportion of cell types and social status depended on sociodemographic variables, we tested the interaction between: social status and age (status*age) and for social status and sex (status*sex, model 8—Supplementary Table 3). Furthermore, since we identified interactions between social status and sex, and since social status is acquired differently for male and females in rhesus macaques, we fitted a separate model for males and females to test if there was a main effect of social status within each sex on the proportions of different cell types. Age and sample period were also included in the model to control for these covariates (model 9—Supplementary Table 3).

The linear models and sample sizes for each are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. For every predictor variable in the full (n = 369) and status (n = 250) datasets, we corrected for multiple hypothesis tests using the Benjamini Hochberg FDR approach and considered significant associates at FDR < 0.10. Because Model 7 was only performed in cell types that showed a significant interaction between sex and social status (and not all the cell types measured), we did not correct for multiple testing in this model.

Results

Macaques exhibit age-related variation in immune cell composition and inflammation

Age was significantly positively associated with the first principal component (PC) of immune cell composition (model 1—βPC1 age = 0.14, FDR = 7.2 × 10–18, Fig. 1D). This first PC, which explained 32.4% of the variance in cell composition across all samples, was associated with higher proportions of inflammation-associated cell types, such as CD3 + CD8 + cytotoxic T cells and CD3 + CD4 + /CD8 + CD25 + T cells, and lower proportions of cells involved in pathogen clearance, including CD20 + B cells and classical monocytes (Fig. 1E, Supplementary Table 4). Thus, older animals exhibited a higher proportion of cell types known to be associated with inflammation and immunosenescence.

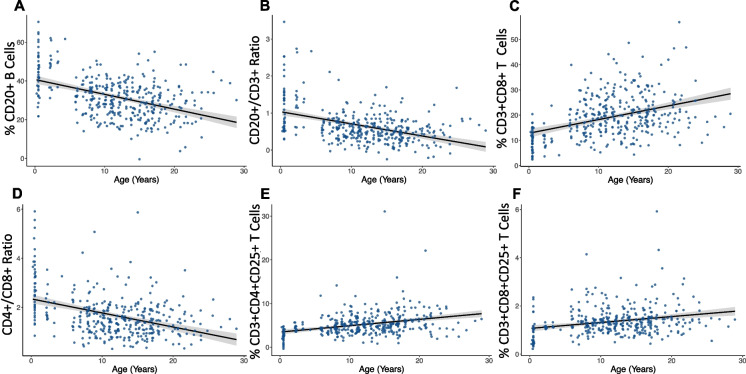

We then conducted a more granular analysis of the factors associated with the individual proportions of cell types. Age was significantly associated with signatures of immunosenescence, including a decline in adaptive immune cells. This was largely driven by lower proportions of CD20 + B cells in older individuals (model 3—βCD20 age = −0.83 ± 0.09, FDR = 1.3 × 10–16, Fig. 2A), which resulted in significantly lower CD20 + /CD3 + ratios in older individuals (model 3—βCD20:CD3 age = −0.04 ± 0.004, FDR = 4.9 × 10–15, Fig. 2B). Age was also associated with higher proportions of inflammation-related cells. The proportion of cytotoxic CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells was significantly higher in older animals (model 3—βCD8 age = 0.60 ± 0.07, FDR = 3.2 × 10–14, Fig. 2C), resulting in a strong and significant effect of lower CD4 + /CD8 + ratios (model 3—βCD4:CD8 age = −0.06 ± 0.008, FDR = 4.3 × 10–14, Fig. 2D) and higher proportions of CD3 + T cells in older individuals (model 3—βCD3 = 0.67 ± 0.11, FDR = 2.2 × 10–8, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Age-associated differences in adaptive immune cell proportions. A) CD20 + B cells (βCD20 = −0.83 ± 0.09, FDR = 1.3 × 10–16) proportions and B) CD20 + /CD3 + ratio (βCD20:CD3 = −0.04 ± 0.004, FDR = 4.9 × 10–15) are lower in older individuals. C) CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells (βCD8 = 0.60 ± 0.07, FDR = 3.2 × 10–14) are higher in older individuals, while the D) CD4 + /CD8 + T cell ratio (βCD4:CD8 = −0.06 ± 0.008, FDR = 4.3 × 10–14) is lower in older individuals. E) CD3 + CD4 + CD25 + T cells (β = 0.16 ± 0.02, FDR = 3.6 × 10–10) and F) CD3 + CD8 + CD25 + T cells are higher in older individuals compared to younger individuals (β = 0.03 ± 0.005, FDR = 1.8 × 10–6), possibly because of higher baseline levels of inflammation (i.e., inflammaging)

Next, we examined the less abundant but immunologically important CD3 + CD4 + CD25 + and CD3 + CD8 + CD25 + T cell populations. It has been previously demonstrated that more than 95% of T cells which express the CD25 + marker also express Foxp3, a key marker for T regulatory cells [61]. Although we did not measure Foxp3 specifically, it is likely that the CD3 + CD4 + CD25 + and CD3 + CD8 + CD25 + T cell populations are part of the T cell regulatory phenotype. These cells, which are involved in immune suppression and maintenance of self-tolerance (i.e., the ability to recognize self-antigens), [62] were significantly more abundant in older animals (model 3—CD3 + CD4 + CD25 + : β age = 0.16 ± 0.02, FDR = 3.6 × 10–10, Fig. 2E; model 3—CD3 + CD8 + CD25 + : β age = 0.03 ± 0.005, FDR = 1.8 × 10–6, Fig. 2F). Because of these cells ability to regulate and suppress immune response, while at the same time playing a role in age-related diseases by contributing to autoimmunity [63, 64], the age-related increases in both of these T cell subtypes suggest a reduced age-related ability to regulate endogenous and exogenous antigens.

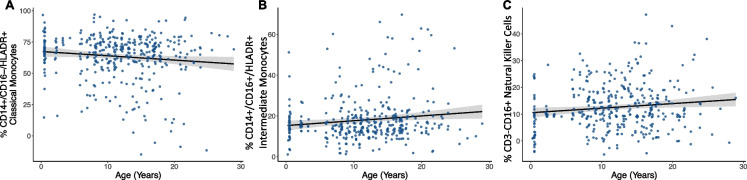

Innate immune cells also showed significant associations with age. Classical monocytes (HLA-DR + /CD14 + /CD16-), which are involved in phagocytosis and extracellular pathogen clearance [65], were lower in older individuals (model 3—βCD14++ age = −0.31 ± 0.16, FDR = 0.07, Fig. 3A), while intermediate monocytes (HLA-DR + /CD14 + /CD16 +), involved in immune cell recruitment and proinflammatory cytokine secretion [65], were higher in older individuals (model 3—βCD14+CD16+ age = 0.21 ± 0.09, FDR = 0.04, Fig. 3B). The proportion of CD16 + CD3- NK cells – which have a similar role to CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells presenting natural cytotoxicity but are not antigen specific – was also significantly higher in older individuals (model 3—βNK age = 0.17 ± 0.07, FDR = 0.03, Fig. 3C). Together, these results may point to an age-associated decrease in adaptive immunity, along with an age-associated increase in inflammation-related innate immune cells, potentially disrupting a “healthy” homeostatic immune system.

Fig. 3.

Age is associated with variation in innate immune cell proportions. A) CD14 + /CD16-/HLADR + Classical monocytes (βCD14++ = −0.31 ± 0.16, FDR = 0.07) are lower and B) CD14 + /CD16 + /HLADR + intermediate monocytes (βCD14+CD16+ = 0.21 ± 0.09, FDR = 0.04) are higher in older individuals, while C) CD16 + NK cells (βNK = 0.17 ± 0.07, FDR = 0.03) are higher in older individuals

We did not observe statistically significant main effects of sex (model 3 in Methods) or a sex-age interaction (model 4 in Methods) on immune cell proportions. Nevertheless, a trend toward sex differences was observed in both the proportions of CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells (model 3—βCD8 sex = 2.19 ± 0.95, FDR = 0.14) and in the CD4 + /CD8 + ratio (model 3—βCD4:CD8 sex = −0.24 ± 0.09, FDR = 0.14, Supplementary Fig. 4), with males having a higher proportion of CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells compared to females, and females having a higher CD4 + /CD8 + ratio compared to males, suggesting a stronger adaptive immune response in females, which, in part, is generated by CD4 + T helper cells.

Social status and immune cell composition

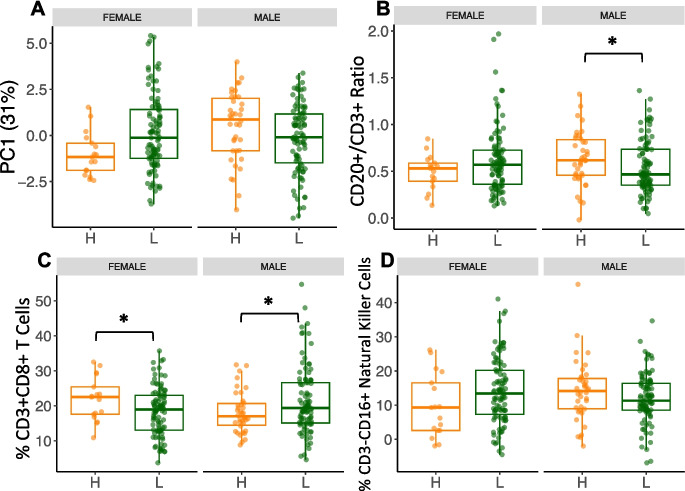

There was a significant interaction between social status and sex on PC1 (31% of the variance in cell composition across all samples) of immune cell composition (model 6—βPC1-sex*status = −1.7 ± 0.63, FDR = 0.04, Fig. 4A), documenting the sex-dependent impact of social status on immunity.

Fig. 4.

Sex and social status interact to impact immune cell proportions. A) PC1 (31% of the variation in the dataset, βPC1-sex*status = −1.7, FDR = 0.03) recapitulates the interaction between sex and social status. B) Interaction in the CD20 + /CD3 + ratio (βCD20/CD3 ratio-sex*status = −0.25 ± 0.05, FDR = 0.06) shows that this ratio is higher with higher social status in males while it is lower with higher social status in females; within-sex analysis show that high social status males have a significantly higher ratio than low social status males (βCD20/CD3 ratio-males/status = −1.3 ± 0.06, p = 0.04). C) CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells show an interaction (βCD8-sex*status = 8.3 ± 2.94, FDR = 0.04) where this cell type is higher in lower social status in males, while it is higher in high social status females. Within-sex analysis of CD8 + T cells showed low social status males had significantly higher proportions of this cell type than did high social status males (βCD8-males/status = 4 ± 1.8, p = 0.03), while the opposite effect was observed in females (βCD8-females/status = −4.8 ± 2.1, p = 0.03). D) Interaction in the proportion of NK Cells (βNK-sex*status = −7.9 ± 3.2, FDR = 0.05), with high social status males showing higher proportions, while high social status females show lower proportions

When modeling males and females together in an additive modeling framework, we found no significant effects of social status on immune cell proportions (all FDR > 0.10, model 7 in Methods), or between the interaction between social status and age (model 8 in Methods). However, we found many significant interactions between social status and sex on immune cell proportions (model 8 in Methods). Because social status is acquired differently for male and female rhesus macaques, we also carried out post-hoc analyses of the social status effects within each sex separately (model 9 in Methods).

The CD20 + /CD3 + ratio interacted between social status and sex such that it was higher in males of high social status, but lower in females with high social status (model 8—βCD20/CD3 ratio-sex*status = −0.26 ± 0.11, FDR = 0.06, Fig. 4B), both part of the adaptive immune system. This difference in the CD20 + /CD3 + ratio seems to be partially driven by interaction between sex and social status on the proportion of CD3 + T cells (model 8—βCD3-sex*status = 11.8 ± 4.42, FDR = 0.04, Supplementary Fig. 5), such that CD3 + T cells were higher in low social status males, but this pattern was flipped in females. There was a within-sex main effect of social status in males in the CD20 + /CD3 + ratio, with high social status males having a significantly higher ratio than low social status males did (model 9—βCD20/CD3 ratio-males/status = −1.3 ± 0.06, p = 0.04, Fig. 4B). No significant effect of social status on the CD20 + /CD3 + ratio was found in females (model 9—βCD20/CD3 ratio-females/status = 0.10 ± 0.13, p = 0.19).

Additionally, there was a significant interaction between social status and sex in the proportion of CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells (model 8—βCD8-sex*status = 8.3 ± 2.94, FDR = 0.04, Fig. 4C), which were higher in high social status males, but this relationship again flipped females. Our within-sex analysis revealed a significant main effect of CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells, in which low social status males had significantly higher proportions of this cell type than did high social status males (model 9—βCD8-males/status = 4 ± 1.8, p = 0.03, Fig. 4C). The opposite main effect was observed in females, in which high-status females had significantly higher proportions of CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells than did low social status females (model 9—βCD8-females/status = −4.8 ± 2.1, p = 0.03, Fig. 4C).

In the innate arm of the immune system, we detected an interaction between social status and sex on the proportion of CD3-CD16 + NK cells (model 8—βNK-sex*status = −7.9 ± 3.2, FDR = 0.05, Fig. 4D), where the proportion was lower in males of low-status, but higher in females of low-status. Social status approached significance in the proportions of CD3-CD16 + NK cells in females (model 9—βNK-females/status = 5.6 ± 3, p = 0.06, Fig. 4D), in which low social status females displayed higher proportions of this cell type compared to high social status females. We found no significant main effect of social status on CD3-CD16 + NK cells in males (model 9—βNK-males/status = −2.27 ± 3.4, p = 0.18).

Discussion

We examined how social status, age, and sex were related to immune cell distributions in a large sample of adult rhesus macaques living in semi-natural conditions. Overall, we found strong and consistent signatures of age-related immune cell dysregulation. We also identified significant links between social status and sex in cells of innate and adaptive arms of the immune system. Together, this variation is likely to influence immune responses to pathogenic challenges as well as the development of inflammation-related diseases.

Overall, macaques exhibited age-related differences in immune cells similar to those observed in humans, including declines in lymphocytes [66]. Here, we also identified more specific cell types with age-related differences. We detected lower proportions of CD20 + B cells at older ages, which may reflect immunosenescence, as these cells are responsible for antibody production, pathogen clearance, and are key cells in the generation of immune memory. Further, a key factor underlying the limited efficacy of vaccines in older individuals is a weakened B cell response [67]; B cells have also been associated with protection against certain types of cancer, such as lung cancer [68].

Similar to two other studies in captive macaques, we found higher CD8 + T cell proportions at older ages [69, 70]. Notably, this differs from findings in humans, where both CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells and their effector responses (i.e., stimulus responsiveness) exhibit lower proportions at older ages [71]. It is possible that this discrepancy is only reflected in the overall CD8 + cytotoxic T cell pool, as it has been reported that certain CD8 + T cell subsets – such as memory subsets – increase in proportion and efficacy with age [72]. Alternatively, given that CD8 + T cell subsets have been associated with inflammation and inflammaging [73], there is a possibility that higher overall CD8 + Cytotoxic T cell pool in rhesus macaques is indicative of higher levels of inflammation. The age-related reduction in CD4 + /CD8 + ratio corroborates this hypothesis. In support of increased inflammation with age, we found that older animals had significantly higher CD3-CD16 + NK cell proportions in our dataset. Similar to CD8 + Cytotoxic T cells, CD3-CD16 + NK cells respond to intracellular pathogens, secrete multiple proinflammatory mediators, and are crucial during tumor surveillance and signaling [74]. The higher proportions of CD3-CD16 + NK cells predict a higher incidence of inflammation and/or tissue injury in the older population, which is commonly observed in the Cayo Santiago macaque population [42]. As expected, CD3 + CD4 + CD25 + T cells as well as CD3 + CD8 + CD25 + T cells were associated with age, possibly indicating higher levels of inflammation in older individuals [64]. These results, together with lower levels of CD20 + B cell proportions and higher levels of CD8 + T cell and CD3-CD16 + NK cell proportions, further support the hypothesis that the adaptive immune response in rhesus macaques decreases with age and inflammation-related cell types increase (i.e., inflammaging). Taken together, these alterations may drive biological and physiological decline that likely increases the risk of morbidity and mortality in macaques, as it does in humans.

Monocyte proportions also varied with age. Specifically, we found fewer CD14 + classical monocytes in older animals. These cells are phagocytic cells that ingest pathogens that they encounter [75]. This age-related reduction may indicate a reduction in phagocytosis (ingestion of pathogens by classical monocytes) and thus can possibly increase infections in older individuals. In addition, older individuals had higher proportions of CD14 + /CD16 + intermediate monocytes, which are strongly associated with inflammation [76]. For instance, an increase in this cell type has been linked to disorders such as chronic kidney disease [77]. The decrease in classical monocytes, together with an increase in intermediate monocytes, represents yet another signature of immunosenescence and inflammaging.

One of the strengths of our study system was the ability to quantify social adversity, operationalized as social status, and test if and how social status influenced immune variation and whether the effects of status varied with age and/or sex. Overall, we found significant variation across both males and females in immune cell proportions and PC compositions (Fig. 4). This may be due to factors such as natural inter-individual variation in immunity [78], and more importantly, there is the possibility that such variation reflects the fact that there are differences in sensitivity to environmental influences [79], possibly making some individuals more resilient than other to the effects of social adversity. Further, there is the chance that naturally occurring infections or injuries can also impact immune cell variation.

We found no main effect of social status on the proportion of immune cell types when testing all samples. Also, there was no interaction between social status and age on the proportions of immune cell types. This result was contrary to our expectations because we expected low social status individuals to experience more variation in immune cell types with increasing age. Nevertheless, we found that several immune cell types demonstrated an interaction between social status and sex. Additionally, we found a within-sex main effect of social status on immune cell proportions, further demonstrating the sex-dependent effects of social status on immune cell proportions which can possibly reflect the different pathways through which social status is acquired in males and females, and thus highlights the fact that different sexes experience social adversity differently across the hierarchy.

The interaction of social status and sex influenced adaptive and innate immune cell types such as CD20 + /CD3 + ratio and CD8 + T cells and CD3-CD16 + NK cells, where the proportions of these cell types associated with status depended on the sex of the individual. In humans, social stressors, such as lower socioeconomic status and lower subjective social status, can affect cytokine release and inflammatory responses in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in a sex-dependent manner [80, 81]. However, studies in humans that have looked at the interaction between social stressors (such as socioeconomic status) and sex on immune cell proportions have found no significant interaction between these covariates [28], thus making our study unique in reporting sex-dependent effects of social status.

We also found a significant main effect of social status in the within-sex analysis on the CD20 + B cell/CD3 + ratio, with high social status males having significantly higher ratios than low-status males. The decrease in the CD20 + /CD3 + ratio seems to be driven by a decrease in the proportions of CD3 + T cells in low social status males (Supplementary Fig. 5) compared to high-status males. Decreases in this cell type have been associated with decreases in cell-mediated immunity to bacteria and viruses [82, 83], potentially showing that the T cell response in macaques is negatively affected by low social status. In addition, CD8 + T cell proportions were higher in low social status males compared to high social status macaques. Few prior studies have assessed sociality-related immune cell differences in male rhesus [84], likely because of ethical and husbandry constraints, such as aggressive behavior between males. One study in male Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) reported that males with strong social bonds had lower levels of fecal glucocorticoids [85], which is typically associated with reduced inflammation [86]. Additionally, studies in cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) have shown that low social status males had a higher probability of being infected with a virus than did high social status macaques [87]. These findings should be taken with caution, however, as other studies of macaques (rhesus and other species) found no differences in infection rate or immune responses between high and low-status males [88, 89]. Although there are currently no data associating social status (or other social stressors) with CD8 + T cells in rhesus macaques, there are reports in other species that CD8 + T cells can mediate the release of proinflammatory cytokines during stressful conditions [90]. Our finding of higher proportions of CD8 + T cells in low social status macaques might indicate higher levels of baseline cytotoxic T cell activation, potentially affecting the CD4 + T cell response. Testing this idea will require methods such as cytokine analysis or next generation sequencing.

There was also a main effect of social status on the proportion of CD8 + T cells in females, but in contrast to males, high social status females had significantly higher proportions of this cell type compared to low social status females. One study also reported lower proportions of CD8 + T cells in low social status in non-free-ranging female rhesus macaques [41]. Given that females tend to have lower proportions of CD8 + T cells than males regardless of age [91–93], a lower proportion of this cell type in low social status females might indicate lower cytotoxic immunity at baseline. Female social status also had a main effect on the proportion of CD3-CD16 + NK cells (associated with immune surveillance, inflammation and innate responses), with low social status females having significantly higher proportions of this cell type than high social status females. Although a prior study found that the proportion of CD3-CD16 + NK cells did not vary with social status in female rhesus macaques, it did find that this cell type was the most sensitive to social status. Specifically, low social status females showed patterns of gene expression consistent with a proinflammatory phenotype in this cell type in response to lipopolysaccharide [94]. These results highlight that low-status female rhesus macaque may experience higher levels of basal inflammation, consistent with other studies in this species [94–96].

One limitation of our study is that, due to the length of the study, we did not directly quantify some canonical health outcomes (e.g., cytokines, disease). Nevertheless, immune cell composition itself is reflective of immunological health and downstream health outcomes [97, 98]. Future studies should, and we will, expand to include other markers of inflammaging and immunosenescence (e.g., interleukins levels and complement proteins), as well as look at how well individuals can respond to innate and adaptive immune challenges (e.g., using in vitro stimulations paired with next-generation sequencing or other ‘omics).

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that, at the level of circulating immune cell proportions, macaques and humans show similar age-related variation in immune cell types. Although we did not detect any significant main effects of sex or sex-age interaction, it is possible that more specific, but unmeasured adaptive immune cells, such as the effector and memory subsets of B cells and T cells, could differ between males and females. In future studies, it will be important to measure other innate immune cell types, such as dendritic cells and granulocytes, since these cell types are critical for antigen presentation and the development of adaptive immune response. We found that the effects of social status differed between males and females, which is likely due to sex-differences in how rhesus macaques obtain social status. Specifically, females inherit their social status, which remains relatively stable throughout their lives, while males queue and occasionally fight to establish and maintain their social status, which may lead to stronger effects of status on immune cell distribution and function. Overall, our study provides detailed insights into the impacts of social and demographic variation on immune cell status in a non-human primate model with unparalleled translatability to humans.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Part of Fig. 1, panel A, was created with BioRender.com.

We thank the Caribbean Primate Research Center for their help in collecting data, especially Giselle Carabllo Cruz, and Nahiri Rivera Barreto; Crisanta Serrano and Stephanie Dorta for laboratory advice; Corbin Johnson, Laura Newman, Alice Baniel, India Schneider-Crease, Kenneth Chiou, Trisha Zintel, and other members of the Snyder-Mackler, Sariol, Higham, Platt, and Brent labs for helpful discussions during the course of this work.

Cayo Biobank Research Unit Members:

Melween I. Martinez4, Michael J. Montague9

Michael L. Platt9,10,11

James P. Higham6

Lauren J. N. Brent5

Noah Snyder-Mackler7,8,12

Author contributions

M.R.S.R., J.P.H., L.J.N.B., C.A.S., M.J.M, M.L.P., and N.S.-M designed research; M.R.S.R., N.M.R., M.M.W., A.D.N.-D, P.P., M.A.P.-F., E.R.S., E.B.C., J.E.N.-D., D.P., A.R.L., M.J.M. and CBRU performed research; M.R.S.R and N.S.-M. analyzed data; and M.S.R. and N.S.-M. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-AG060931; R01-AG060931-S1; R00-AG051764; R01-MH118203; R01-MH096875; R56-AG071023; F31-AG072787; R36-AG080081; C06-OD026690; P40-OD012217; NSF-1800558; ERC-864461).

Data availability

The dataset and code to replicate analysis and plots is available at https://github.com/MSROSADO/Flow_cytometry_analysis. Any other materials can be made available upon request to the author.

Declarations

Ethical note

This work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus (IACUC Number: A400117).

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mitchell R. Sanchez Rosado, Email: Mitchell.sanchez@upr.edu.

Cayo Biobank Research Unit, Email: cbru@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

Noah Snyder-Mackler, Email: nsnyderm@asu.edu.

Cayo Biobank Research Unit:

Melween I. Martinez, Michael J. Montague, Michael L. Platt, James P. Higham, Lauren J. N. Brent, and Noah Snyder-Mackler

References

- 1.Roser M, Ortiz-Ospina E, Ritchie H. Life expectancy. 2013. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy [Online Resource]. Accessed 9 Jun 2021

- 2.Strait JB, Lakatta EG. Aging-associated cardiovascular changes and their relationship to heart failure. Heart Fail Clin 2012;8(1):143–164. 10.1016/j.hfc.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Yung RL, Julius A. Epigenetics, aging, and autoimmunity. Autoimmunity. 2008;41(4):329–335. doi: 10.1080/08916930802024889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halim M, Halim A. The effects of inflammation, aging and oxidative stress on the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus (type 2 diabetes) Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13(2):1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacitharan PK. Ageing and osteoarthritis. Biochem Cell Biol Ageing II Clin Sci. 2019;123–59. 10.1007/978-981-13-3681-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15(9):505–522. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0064-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology. 2007;120(4):435–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan J, Greer JM, Hull R, et al. The effect of ageing on human lymphocyte subsets: comparison of males and females. Immun Ageing. 2010;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen YJ, Liao YJ, Tram VTN, Lin CH, Liao KC, Liu CL. Alterations of specific lymphocytic subsets with aging and age-related metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Life. 2020;10(10):246. doi: 10.3390/life10100246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hearps AC, Martin GE, Angelovich TA, Cheng WJ, Maisa A, Landay AL, et al. Aging is associated with chronic innate immune activation and dysregulation of monocyte phenotype and function. Aging Cell. 2012;11(5):867–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gounder SS, Abdullah BJJ, Radzuanb NEIBM, Zain FDBM, Sait NBM, Chua C, Subramani B. Effect of aging on NK cell population and their proliferation at ex vivo culture condition. Anal Cell Pathol. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/7871814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jagger A, Shimojima Y, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Regulatory T cells and the immune aging process: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2014;60(2):130–137. doi: 10.1159/000355303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Veeken J, Gonzalez AJ, Cho H, Arvey A, Hemmers S, Leslie CS, Rudensky AY. Memory of inflammation in regulatory T cells. Cell. 2016;166(4):977–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giefing-Kröll C, Berger P, Lepperdinger G, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. How sex and age affect immune responses, susceptibility to infections, and response to vaccination. Aging Cell. 2015;14(3):309–321. doi: 10.1111/acel.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ademokun A, Wu YC, Dunn-Walters D. The ageing B cell population: Composition and function. Biogerontology. 2010;11:125–137. doi: 10.1007/s10522-009-9256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, D'Eramo F, Blomberg BB. Aging effects on T-bet expression in human B cell subsets. Cell Immunol. 2017;321:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GubbelsBupp MR, Potluri T, Fink AL, Klein SL. The confluence of sex hormones and aging on immunity. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1269. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerra-Silveira F, Abad-Franch F. Sex bias in infectious disease epidemiology: patterns and processes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e62390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D, Syme SL, Balmes J, Adler N. Social isolation: a predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):2056–2062. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole SW. Human social genomics. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(8):e1004601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4;pmid:10972429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson JA, Johnston RA, Lea AJ, Campos FA, Voyles TN, Akinyi MY, et al. High social status males experience accelerated epigenetic aging in wild baboons. Elife. 2021;10:e66128. doi: 10.7554/eLife.66128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiorito G, Polidoro S, Dugué PA, Kivimaki M, Ponzi E, Matullo G, et al. Social adversity and epigenetic aging: a multi-cohort study on socioeconomic differences in peripheral blood DNA methylation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16391-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ridout KK, Levandowski M, Ridout SJ, Gantz L, Goonan K, Palermo D, et al. Early life adversity and telomere length: a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):858–871. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snyder-Mackler N, Somel M, Tung J. Shared signatures of social stress and aging in peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles. Aging Cell. 2014;13(5):954–957. doi: 10.1111/acel.12239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elwenspoek MM, Hengesch X, Leenen FA, Schritz A, Sias K, Schaan VK, et al. Proinflammatory T cell status associated with early life adversity. J Immunol. 2017;199(12):4046–4055. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klopack ET, Crimmins EM, Cole SW, Seeman TE, Carroll JE. Social stressors associated with age-related T lymphocyte percentages in older US adults: evidence from the US Health and Retirement Study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119(25):e2202780119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2202780119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uddin M, Aiello AE, Wildman DE, Koenen KC, Pawelec G, de Los Santos R, et al. Epigenetic and immune function profiles associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(20):9470–9475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910794107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aiello AE, Feinstein L, Dowd JB, Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E, Galea S, et al. Income and markers of immunological cellular aging. Psychosomat Med. 2016;78(6):657. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole SW. Social regulation of human gene expression: mechanisms and implications for public health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(S1):S84–S92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roth GS, Mattison JA, Ottinger MA, Chachich ME, Lane MA, Ingram DK. Aging in rhesus monkeys: relevance to human health interventions. Science. 2004;305(5689):1423–1426. doi: 10.1126/science.1102541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiou KL, Montague MJ, Goldman EA, Watowich MM, Sams SN, Song J, et al. Rhesus macaques as a tractable physiological model of human ageing. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2020;375(1811):20190612. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2019.0612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thierry B, Singh M, Kaumanns W, editors. Macaque societies: a model for the study of social organization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brent LJ, MacLarnon A, Platt ML, Semple S. Seasonal changes in the structure of rhesus macaque social networks. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2013;67(3):349–359. doi: 10.1007/s00265-012-1455-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulik L, Amici F, Langos D, Widdig A. Sex differences in the development of social relationships in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Int J Primatol. 2015;36(2):353–376. doi: 10.1007/s10764-015-9826-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vandeleest JJ, Winkler SL, Beisner BA, Hannibal DL, Atwill ER, McCowan B. Sex differences in the impact of social status on hair cortisol concentrations in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Am J Primatol. 2020;82(1):e23086. doi: 10.1002/ajp.23086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Datta S. The acquisition of dominance among free-ranging rhesus monkey siblings. Anim Behav. 1988;36(3):754–772. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(88)80159-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder-Mackler N, Burger JR, Gaydosh L, Belsky DW, Noppert GA, Campos FA, et al. Social determinants of health and survival in humans and other animals. Science. 2020;368(6493). 10.1126/science.aax9553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Kohn JN, Snyder-Mackler N, Barreiro LB, Johnson ZP, Tung J, Wilson ME. Dominance rank causally affects personality and glucocorticoid regulation in female rhesus macaques. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;74:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Debray R, Snyder-Mackler N, Kohn JN, Wilson ME, Barreiro LB, Tung J. Social affiliation predicts mitochondrial DNA copy number in female rhesus macaques. Biol Let. 2019;15(1):20180643. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2018.0643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pavez-Fox MA, Kimock CM, Rivera-Barreto N, Negron-Del Valle JE, Phillips D, Ruiz-Lambides A, et al. Reduced injury risk links sociality to survival in a group-living primate. Iscience. 2022;25(11):105454. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blomquist GE, Sade DS, Berard JD. Rank-related fitness differences and their demographic pathways in semi-free-ranging rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Int J Primatol. 2011;32:193–208. doi: 10.1007/s10764-010-9461-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tung J, Barreiro LB, Johnson ZP, Hansen KD, Michopoulos V, Toufexis D, et al. Social environment is associated with gene regulatory variation in the rhesus macaque immune system. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(17):6490–6495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202734109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessler MJ, Rawlins RG. A 75-year pictorial history of the Cayo Santiago rhesus monkey colony. Am J Primatol. 2016;78(1):6–43. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clutton-Brock T. Mammal societies. Wiley; 2016. 10.1093/jmammal/gyx078.

- 47.Cerroni AM, Tomlinson GA, Turnquist JE, Grynpas MD. Bone mineral density, osteopenia, and osteoporosis in the rhesus macaques of Cayo Santiago. Am J Phys Anthropol: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 2000;113(3):389–410. 10.1002/1096-8644(200011)113:3%3c389::AID-AJPA9%3e3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Lee DS, Kang YH, Ruiz-Lambides AV, Higham JP. The observed pattern and hidden process of female reproductive trajectories across the life span in a non-human primate. J Anim Ecol. 2021;90(12):2901–2914. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.13590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watowich MM, Chiou KL, Montague MJ, Cayo Biobank Research Unit. Simons ND, Horvath JE, et al. Natural disaster and immunological aging in a nonhuman primate. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(8):e2121663119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2121663119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper EB, Brent LJ, Snyder-Mackler N, Singh M, Sengupta A, Khatiwada S, et al. The Natural History of Model Organisms: the rhesus macaque as a success story of the Anthropocene. Elife. 2022;11:e78169–e78169. doi: 10.7554/elife.78169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rawlins RG, Kessler MJ, editors. The Cayo Santiago macaques: history, behavior, and biology. SUnY Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pérez-Guzmán EX, Pantoja P, Serrano-Collazo C, Hassert MA, Ortiz-Rosa A, Rodríguez IV, et al. Time elapsed between Zika and dengue virus infections affects antibody and T cell responses. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12295-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marzan-Rivera N, Serrano-Collazo C, Cruz L, Pantoja P, Ortiz-Rosa A, Arana T, et al. Infection order outweighs the role of CD4+ T cells in tertiary flavivirus exposure. Iscience. 2022;25(8):104764. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asiedu CK, Goodwin KJ, Balgansuren G, Jenkins SM, Le Bas-Bernardet S, Jargal U, et al. Elevated T regulatory cells in long-term stable transplant tolerance in rhesus macaques induced by anti-CD3 immunotoxin and deoxyspergualin. J Immunol. 2005;175(12):8060–8068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morita D, Hattori Y, Nakamura T, Igarashi T, Harashima H, Sugita M. Major T cell response to a mycolyl glycolipid is mediated by CD1c molecules in rhesus macaques. Infect Immun. 2013;81(1):311–316. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00871-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Noordwijk MA, van Schaik CP. Sexual selection and the careers of primate males: paternity concentration, dominance–acquisition tactics and transfer decision. Sexual selection in primates: New and comparative perspectives. 2004;208–29. 10.1017/CBO9780511542459.014.

- 57.Kimock CM, Dubuc C, Brent LJ, Higham JP. Male morphological traits are heritable but do not predict reproductive success in a sexually-dimorphic primate. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52633-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brent LJN, Semple S, Dubuc C, Heistermann M, MacLarnon A. Social capital and physiological stress levels in free-ranging adult female rhesus macaques. Physiol Behav. 2011;102(1):76–83. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Madlon-Kay S, Brent L, Montague M, Heller K, Platt M. Using machine learning to discover latent social phenotypes in free-ranging macaques. Brain Sci. 2017;7(7):91. doi: 10.3390/brainsci7070091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2021. https://www.R-project.org/.

- 61.Zelenay S, Lopes-Carvalho T, Caramalho I, Moraes-Fontes MF, Rebelo M, Demengeot J. Foxp3+ CD25–CD4 T cells constitute a reservoir of committed regulatory cells that regain CD25 expression upon homeostatic expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(11):4091–4096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408679102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(7):523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kondelková K, Vokurková D, Krejsek J, Borská L, Fiala Z, Ctirad A. Regulatory T cells (TREG) and their roles in immune system with respect to immunopathological disorders. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2010;53(2):73–7. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2016.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rocamora-Reverte L, Melzer FL, Würzner R, Weinberger B. The complex role of regulatory T cells in immunity and aging. Front Immunol. 2021;11:616949. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.616949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Idzkowska E, Eljaszewicz A, Miklasz P, Musial WJ, Tycinska AM, Moniuszko M. The role of different monocyte subsets in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and acute coronary syndromes. Scand J Immunol. 2015;82(3):163–173. doi: 10.1111/sji.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Erkeller-Yuksel FM, Deneys V, Yuksel B, Hannet I, Hulstaert F, Hamilton C, et al. Age-related changes in human blood lymphocyte subpopulations. J Pediatr. 1992;120(2):216–222. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frasca D, Blomberg BB, Garcia D, Keilich SR, Haynes L. Age-related factors that affect B cell responses to vaccination in mice and humans. Immunol Rev. 2020;296(1):142–154. doi: 10.1111/imr.12864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Germain C, Gnjatic S, Tamzalit F, Knockaert S, Remark R, Goc J, et al. Presence of B cells in tertiary lymphoid structures is associated with a protective immunity in patients with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(7):832–844. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1611OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Asquith M, Haberthur K, Brown M, Engelmann F, Murphy A, Al-Mahdi Z, Messaoudi I. Age-dependent changes in innate immune phenotype and function in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Pathobiol Aging Age-Relat Dis. 2012;2(1):18052. doi: 10.3402/pba.v2i0.18052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zheng HY, Zhang MX, Pang W, Zheng YT. Aged Chinese rhesus macaques suffer severe phenotypic T-and B-cell aging accompanied with sex differences. Exp Gerontol. 2014;55:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quinn KM, Fox A, Harland KL, Russ BE, Li J, Nguyen TH, et al. Age-related decline in primary CD8+ T cell responses is associated with the development of senescence in virtual memory CD8+ T cells. Cell Rep. 2018;23(12):3512–3524. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li M, Yao D, Zeng X, Kasakovski D, Zhang Y, Chen S, et al. Age related human T cell subset evolution and senescence. Immun Ageing. 2019;16(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12979-019-0165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mogilenko DA, Shpynov O, Andhey PS, Arthur L, Swain A, Esaulova E, et al. Comprehensive profiling of an aging immune system reveals clonal GZMK+ CD8+ T cells as conserved hallmark of inflammaging. Immunity. 2021;54(1):99–115. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meza Guzman LG, Keating N, Nicholson SE. Natural killer cells: tumor surveillance and signaling. Cancers. 2020;12(4):952. doi: 10.3390/cancers12040952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kapellos TS, Bonaguro L, Gemünd I, Reusch N, Saglam A, Hinkley ER, Schultze JL. Human monocyte subsets and phenotypes in major chronic inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2035. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Italiani P, Boraschi D. From monocytes to M1/M2 macrophages: phenotypical vs. functional differentiation. Front Immunol. 2014;5:514. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Naicker SD, Cormican S, Griffin TP, Maretto S, Martin WP, Ferguson JP, et al. Chronic kidney disease severity is associated with selective expansion of a distinctive intermediate monocyte subpopulation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2845. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brodin P, Davis M. Human immune system variation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:21–29. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pluess M, Lionetti F, Aron EN, Aron A. People differ in their sensitivity to the environment: an integrated theory, measurement and empirical evidence. J Res Pers. 2023;104:104377. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2023.104377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moieni M, Muscatell KA, Jevtic I, Breen EC, Irwin MR, Eisenberger NI. Sex differences in the effect of inflammation on subjective social status: a randomized controlled trial of endotoxin in healthy young adults. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2167. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gassen J, White JD, Peterman JL, Mengelkoch S, Proffitt Leyva RP, Prokosch ML, et al. Sex differences in the impact of childhood socioeconomic status on immune function. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9827. doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/DXPZU. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Monserrat J, de Pablo R, Reyes E, Díaz D, Barcenilla H, Zapata MR, et al. Clinical relevance of the severe abnormalities of the T cell compartment in septic shock patients. Crit Care. 2009;13(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/cc7731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chinen J, Easley KA, Mendez H, Shearer WT. Decline of CD3-positive T-cell counts by 6 months of age is associated with rapid disease progression in HIV-1–infected infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(2):265–268. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.116573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pavez-Fox MA, Negron-Del Valle JE, Thompson IJ, Walker CS, Bauman SE, Gonzalez O, et al. Sociality predicts individual variation in the immunity of free-ranging rhesus macaques. Physiol Behav. 2021;241:113560. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2021.113560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Young C, Majolo B, Heistermann M, Schülke O, Ostner J. Responses to social and environmental stress are attenuated by strong male bonds in wild macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(51):18195–18200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411450111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Adcock IM, Mumby S. Glucocorticoids. In: Page C, Barnes P, editors. Pharmacology and therapeutics of asthma and COPD. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Cham: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cohen S, Line S, Manuck SB, Rabin BS, Heise ER, Kaplan JR. Chronic social stress, social status, and susceptibility to upper respiratory infections in nonhuman primates. Psychosom Med. 1997;59(3):213–221. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McAuliffe J, Vogel L, Roberts A, Fahle G, Fischer S, Shieh WJ, et al. Replication of SARS coronavirus administered into the respiratory tract of African Green, rhesus and cynomolgus monkeys. Virology. 2004;330(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Skinner JM, Caro-Aguilar IC, Payne AM, Indrawati L, Fontenot J, Heinrichs JH. Comparison of rhesus and cynomolgus macaques in a Streptococcus pyogenes infection model for vaccine evaluation. Microb Pathog. 2011;50(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Clark SM, Song C, Li X, Keegan AD, Tonelli LH. CD8+ T cells promote cytokine responses to stress. Cytokine. 2019;113:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee BW, Yap HK, Chew FT, Quah TC, Prabhakaran K, Chan GS, et al. Age-and sex-related changes in lymphocyte subpopulations of healthy Asian subjects: from birth to adulthood. Cytometry: J Int Soc Anal Cytol. 1996;26(1):8–15. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19960315)26:1<8::AID-CYTO2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lisse IM, Aaby P, Whittle H, Jensen H, Engelmann M, Christensen LB. T-lymphocyte subsets in West African children: impact of age, sex, and season. J Pediatr. 1997;130(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(97)70313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Uppal SS, Verma S, Dhot PS. Normal values of CD4 and CD8 lymphocyte subsets in healthy Indian adults and the effects of sex, age, ethnicity, and smoking. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2003;52(1):32–36. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Snyder-Mackler N, Sanz J, Kohn JN, Brinkworth JF, Morrow S, Shaver AO, et al. Social status alters immune regulation and response to infection in macaques. Science. 2016;354(6315):10411045. doi: 10.1126/science.aah3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sanz J, Maurizio PL, Snyder-Mackler N, Simons ND, Voyles T, Kohn J, et al. Social history and exposure to pathogen signals modulate social status effects on gene regulation in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(38):23317–23322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820846116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Snyder-Mackler N, Sanz J, Kohn JN, Voyles T, Pique-Regi R, Wilson ME, et al. Social status alters chromatin accessibility and the gene regulatory response to glucocorticoid stimulation in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(4):1219–1228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811758115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schäfer S, Zernecke A. CD8+ T cells in atherosclerosis. Cells. 2020;10(1):37. doi: 10.3390/cells10010037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Girard D, Vandiedonck C. How dysregulation of the immune system promotes diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular risk complications. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:991716. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.991716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset and code to replicate analysis and plots is available at https://github.com/MSROSADO/Flow_cytometry_analysis. Any other materials can be made available upon request to the author.