INTRODUCTION

The F2F Connection project is a collaborative effort involving the School of Library and Information Studies at Texas Woman's University, Houston Academy of Medicine-Texas Medical Center (HAM-TMC) Library, and Family to Family Network (F2FN). The overarching goal of the project is to facilitate access to relevant electronic health information resources for families who have children with special needs. The objective of the initial phase of the project is to conduct an assessment of the community health information needs of families who have children with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities as well as of their care providers.

F2FN works with families, professionals, and friends of children with disabilities and/or chronic illnesses to create communities where all children belong and excel. F2FN provides information and referral services, educational programs, and direct support to this community. In addition to local programming, F2FN operates a training program, Connections, developed for people who are committed to helping the families of children with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities. Connections teaches families about working with school systems to further their children's success. This program represents a collaborative effort between families and educators who share a common vision that all children have value and must have successful educational opportunities to accomplish their dreams. The Connections curriculum has been widely adopted throughout the state of Texas. The F2F Connection project builds on existing successes mounted by F2FN and capitalizes on an academic–community partnership supported by Texas Woman's University and the HAM-TMC Library.

BACKGROUND

Advances in medical science and the provision of health care, decreases in infant and childhood mortality, and the advent of public health programs have yielded growing populations of children experiencing disabilities and/or chronic disease states [1]. The diagnosis of an infant or child with a disability and/or chronic illness has an impact on all family members [2]. When one family member is diagnosed with a health problem, all family members are affected and the family unit as a whole is changed [3]. The diagnosis and management of a disability and/or chronic illness in an infant or child brings with it health, economic, psychological, and social implications [4]. Parents of these infants and children seek coping mechanisms related to the meaning of the health problem and to the increased responsibility they face in caring for an infant or child with special needs. How well parents understand the diagnosis, treatment options, and support systems affects their ability to participate in their child's health care as well as their ability to provide a “normal” childhood experience [5]. Facilitating access to relevant information can play a key role in supporting parents of children with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities along with their care providers.

METHODOLOGY

A series of focus groups was conducted to gain a better understanding of the information needs of families in Texas who have children with chronic illnesses and/ or disabilities. Focus groups were conducted until content saturation was reached (i.e., no unique information was contributed by focus group participants). Six focus groups were conducted: an initial one with F2FN staff members and five subsequent ones with parents of children with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities who have availed themselves of F2FN services.

A total of thirty-three individuals participated in the focus group sessions, eight F2FN staff members and twenty-five F2FN clients. Disabilities and/or chronic illnesses reflected in the target population were represented by the F2FN staff members and parents who comprised the focus group participants. Information provided by focus group participants was anonymous and treated as confidential.

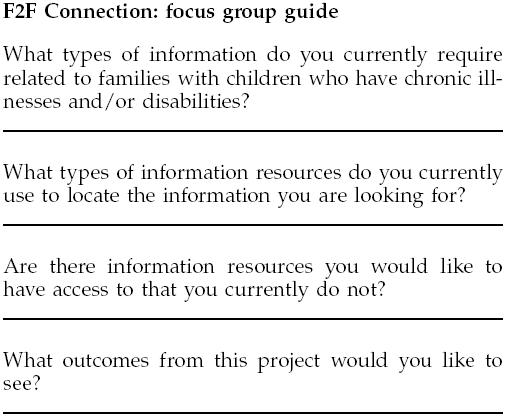

Focus groups were led using a structured format that followed a basic focus group guide (Appendix A). Copies of the focus group guide were provided to participants prior to the beginning of each focus group and collected at the end of each session. Focus group participants were encouraged to make notes on the focus group guide if they did not feel they had the opportunity to express themselves verbally. The guide served two purposes. First, it served as a means to focus discussion and provide general structure for the sessions. Second, it provided an additional mechanism for participants' feedback. Each focus group lasted approximately one hour. All focus groups were audiotaped. Audio tapes were transcribed and reviewed for accuracy. Transcriptions were then analyzed for themes in each section of the focus group guide. As themes were identified, they were recorded and summarized in an Excel spreadsheet. Handwritten information from focus group guides was incorporated into data summaries. Themes were reviewed and verified to provide a measure of dependability.

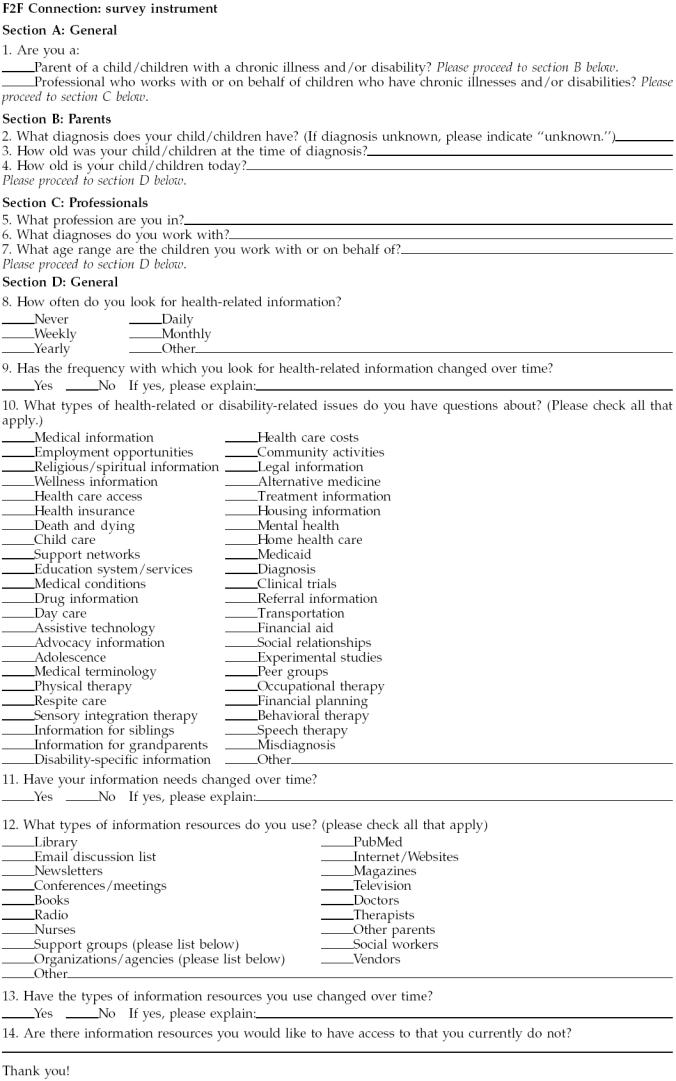

Data provided from the transcriptions and focus group guides were used to develop a survey instrument (Appendix B). The survey instrument was reviewed by F2FN staff members for content and structure and then revised accordingly. The survey, cover letter, and return envelope were mailed to 849 individuals on an existing F2FN mailing list. One hundred forty-three completed surveys were returned, for a return rate of 17%. Survey responses were anonymous and confidential. Data from the returned surveys were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet for analysis.

RESULTS

Of the 143 completed surveys, 104 were from parents of children with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities, 26 were from professionals who worked with children who had chronic illnesses and/or disabilities, and 13 were from parents of children with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities who were also professionals who worked with this population. Of the 117 parents (104 plus 13), 10 reported multiple children who had chronic illnesses and/or disabilities.

The most common diagnosis reported by parents and/or professionals was cerebral palsy (n = 45), followed by autism (n = 39), mental retardation (n = 23), pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (n = 21), and Down syndrome (n = 15). In addition, parents indicated ninety-two children with multiple diagnoses. Four children remained undiagnosed.

When asked how often parents and/or professionals sought health-related information for their children or clients, thirty-five indicated daily, fifty-four weekly, thirty-five monthly, nine yearly, and one never. Nine survey participants did not respond to this question.

When asked if the frequency with which parents and/or professionals sought health-related information for their children or clients had changed over time, ninety-one responded yes and fifty no. Two survey participants did not respond to this question. Narrative associated with positive responses suggested that an individual's information seeking was greater at the time of diagnosis or as it related to new therapies.

When asked what types of health-related or disability-related issues parents and/or professionals had questions about, survey participants were instructed to select all that applied. The most common response was education system/services (n = 94), followed by support networks (n = 91), medical information (n = 89), and disability-specific information (n = 85).

When asked if their health-related or disability-related information needs had changed over time, 101 responded yes and 36 no. Six survey participants did not respond to this question. Narrative associated with positive responses suggested that information needs changed relative to the trajectory of a chronic illness and/or disability and with a child's advancing age. For example, a parent with a one year old just diagnosed with Down syndrome would have different information needs from a parent with a child diagnosed at birth with cerebral palsy who was now entering puberty.

When asked what types of information resources parents and/or professionals used, survey participants were instructed to select all that applied. The most common response was Internet or Websites (n = 118), followed by newsletters (n = 113), conferences or meetings (n = 111), books (100), and other parents (n = 100).

When asked if the types of information resources they used had changed over time, ninety-four responded yes and forty-three no. Six survey participants did not respond to this question. Narrative associated with positive responses suggested that the Internet and Web have had an impact on information resource use. Also, narrative responses suggested that individuals sought general information early on and looked for more detailed or specific information once they had a generic understanding of a topic.

DISCUSSION

Based on data gathered from focus group participants and survey respondents, parents of children with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities have significant information needs as do the professionals who work with this population. However, not all information needs are currently being met. While many focus group participants and survey respondents were experienced Internet and Web users and the Internet and Websites ranked highest among survey participants regarding information resources, not all respondents used the Internet or Web or felt that they were effective users of Internet and Web resources. As for desired information resources, one common theme centered around having access to information resources that reflect the trajectory of chronic illnesses and/or disabilities as well as a child's age. Another common theme among parents was the desire for better referral resources for health care providers.

Although the types of knowledge-based resources desired by project participants do not exist to cover every aspect of unfilled information needs, many current information resources provide partial coverage or coverage of various aspects of a particular issue, disability, or chronic illness. This knowledge deficit (i.e., lack of knowledge concerning the existence of or content contained in various information resources) provides an educational opportunity for health sciences librarians to work with care providers and parents of children who have disabilities and/or chronic illnesses. This opportunity is even greater among those individuals who do not use the Internet or Web or feel that they are not effective users of Internet and Web resources.

Funding for the implementation phase of the project is being used to provide health literacy programming at the F2FN facility. The data gathered during the community health information needs assessment is being used to guide development of this health literacy program. Health sciences librarians are involved in the implementation phase and will be instrumental in facilitating this educational opportunity for F2FN clients.

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

Footnotes

* Supported in part by National Library of Medicine contract no. N01-LM-1-3515.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey T. Huber, Email: jhuber@twu.edu.

Jill D. Dietrich, Email: dietrich@houston.rr.com.

Eve Cugini, Email: f2fnetwork@sbcglobal.net.

Shannon Burke, Email: s_fburke@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- Judson L. Global childhood chronic illness. Nurs Adm Q. 2004 Jan–Mar; 28(1):60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batshaw ML. Your child has a disability. Boston, MA: Little Brown and Company, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Van Riper M.. The sibling experience of living with childhood chronic illness and disability. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2003;21:279–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Goldsmith T, and Patel DR. Behavioral aspects of chronic illness in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2003 Aug; 50(4):859–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston CE, Marder LR. Parenting the child with a chronic condition: an emotional experience. Pediatr Nurs. 1994 Nov–Dec; 20(6):611–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]