Abstract

Amebic liver abscess is characterized by extensive areas of dead hepatocytes that form cavities surrounded by a thin rim of inflammatory cells and few Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites. E. histolytica produces pore-forming proteins and proteinases, but how trophozoites actually kill host cells has been unclear. Here, we report that E. histolytica induces apoptosis in both inflammatory cells and hepatocytes in a severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse model of amebic liver abscess. By studying infection in C57/BL6.lpr and C57/BL6.gld mice, we found that E. histolytica-induced apoptosis does not require the Fas/Fas ligand pathway of apoptosis, and by using mice with a targeted deletion of the tumor necrosis factor receptor I gene, we have shown that E. histolytica-induced apoptosis is not mediated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. Our data indicate that apoptosis plays a prominent role in the host cell death seen in amebic liver abscess in a mouse model of disease and suggest that E. histolytica induces cell death without using two common pathways for apoptosis.

The protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica is the causative agent of amebic dysentery and amebic liver abscess, major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. E. histolytica is an invasive organism, and in vitro studies have demonstrated that amebic trophozoites are capable of lysing a variety of host cells, including hepatocyte and intestinal cell lines, as well as neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages. The pathology of amebic liver abscess is characterized by extensive areas of hepatocyte death, which eventually form cavities filled with tissue debris. The killing capabilities of amebic trophozoites have raised the question of whether E. histolytica causes liver cell death purely by causing necrosis of host cells or whether it is capable of inducing apoptosis within host liver cells. Recently, there have been two in vitro studies looking at the role of apoptosis in amebic cytotoxicity. Ragland et al. cocultured amebic trophozoites with a murine myeloid cell line and found that the myeloid cell line was undergoing death through apoptosis as evidenced by the presence of a characteristic laddering pattern of genomic DNA (12). In contrast, Berninghausen and Leippe, looking at the killing of the Jurkat and HL-60 human cell lines by amebic trophozoites and purified amebapores, found evidence that necrosis, rather than apoptosis, was the major mediator of amebia-mediated cell death in their system (2). Herein, we describe studies with a murine model of amebic liver abscess which demonstrate that apoptosis is occurring extensively among hepatocytes in amebic liver abscess. Furthermore, by studying the pathogenesis of amebic liver abscess in mutant mouse strains and genetically engineered mice, we show that E. histolytica-mediated apoptosis of hepatic cells does not depend on the Fas/Fas ligand or tumor necrosis-factor alpha (TNF-α) pathway, consistent with a role for amebapore or other amebic molecules in the induction of apoptotic cell death.

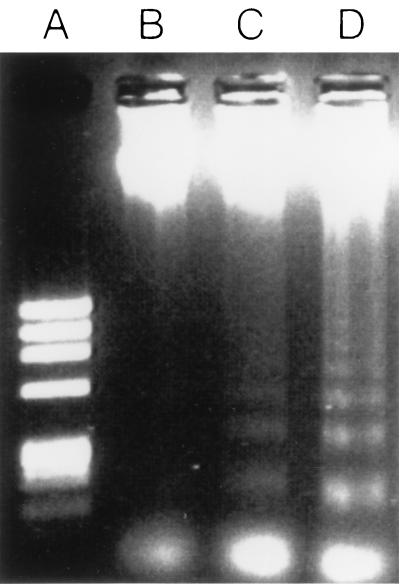

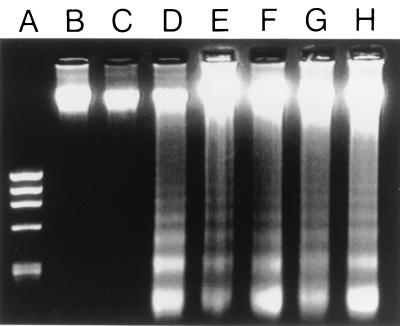

We have previously shown that severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice develop amebic liver abscess within 24 h of direct hepatic inoculation with E. histolytica trophozoites (14). Amebic liver abscesses in SCID mice are characterized by large regions of dead hepatocytes which become surrounded by a narrow ring of inflammatory cells and fibrosis (3). To determine whether hepatocytes were dying by apoptosis in amebic liver abscess, we first inoculated SCID mice intrahepatically with 106 E. histolytica HM1:IMSS trophozoites by our standard protocol (14). The E. histolytica strain used in these studies has been passaged multiple times through mouse livers and is capable of inducing amebic liver abscesses in immunocompromised and immunocompetent mice. At various time points following E. histolytica inoculation, mice were sacrificed and genomic DNA was obtained from both normal and abscessed regions of the liver. For these studies, approximately 100 mg of murine liver tissue was placed into a buffer containing 100 mM Tris (pH 8.5), 5 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 1 μg of proteinase K per ml at a concentration of 50 mg of tissue per ml of buffer. The liver tissue was homogenized for 10 s and then incubated overnight at 56°C. DNA was purified by a standard phenol-chloroform extraction, and the DNA pellet was resuspended in dH2O and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 100 μg of RNase per ml. Five micrograms of DNA was subsequently loaded on a 1.2% agarose gel and subjected to electrophoresis at 100 V for 75 min. Cell death by apoptosis is associated with the activation of endogenous DNases which cleave genomic DNA into multimers of 180 bp. As shown in Fig. 1, we found that as soon as 2 h after inoculation of E. histolytica trophozoites, and clearly by 6 h following inoculation, DNA obtained from regions of amebic liver abscess showed the distinctive laddering of DNA into multimers of 180 bp. Genomic DNA obtained from uninfected livers (Fig. 1) or from regions of E. histolytica-infected livers that were distant from the site of the amebic liver abscess (Fig. 2) did not form DNA ladders. To ensure that apoptosis was being induced specifically by E. histolytica and was not a result of hepatic trauma from the injection, we repeated these studies but injected the nonpathogenic ameba Entamoeba moshkovskii into the livers of SCID mice. E. moshkovskii failed to establish liver abscesses in SCID mice, and genomic DNA obtained from the site of inoculation did not show laddering on gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Apoptosis is detectable in genomic DNA obtained from regions of amebic liver abscess in SCID mice at early time points following infection. Shown are the results of gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA isolated from the livers of SCID mice that were uninfected (lane B) or from the site of inoculation in livers infected with E. histolytica 2 h previously (lane C) or 6 h previously (lane D). The characteristic 180-bp DNA laddering is faintly visible at 2 h and pronounced at 6 h. Lane A is the φX174RF/HaeIII DNA size standards.

FIG. 2.

Apoptosis occurs in amebic liver abscesses with E. histolytica and not E. moshkovskii inoculation and does not require the Fas/Fas ligand or TNFRI pathways. Shown are results of gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA isolated from uninvolved regions of a SCID mouse liver infected with E. histolytica 24 h following infection (lane B), the site of inoculation in the liver from a SCID mouse obtained 24 h after inoculation with E. moshkovskii (lane C), an area of amebic liver abscess 24 h after E. histolytica infection in a C57BL/6 mouse (lane D), an area of amebic liver abscess 24 h after E. histolytica infection in a C57BL/6.lpr mouse (lane E), an area of amebic liver abscess 24 h after E. histolytica infection in a C57BL/6.gld mouse (lane F), an area of amebic liver abscess 24 h after E. histolytica infection in a TNFRI knockout mouse (lane G), and an area of amebic liver abscess 24 h after E. histolytica infection in a SCID mouse (lane H). The characteristic 180-bp DNA laddering is present in DNA from amebic liver abscess tissue in all mice inoculated with E. histolytica, including mice defective in the Fas/Fas ligand pathway (lanes E and F) and mice lacking TNFRI (lane G), but is not present in DNA obtained from nonabscessed regions of liver (lane B) or the inoculation site in a liver infected with E. moshkovskii (lane C). Lane A is the φX174RF/HaeIII DNA size standards.

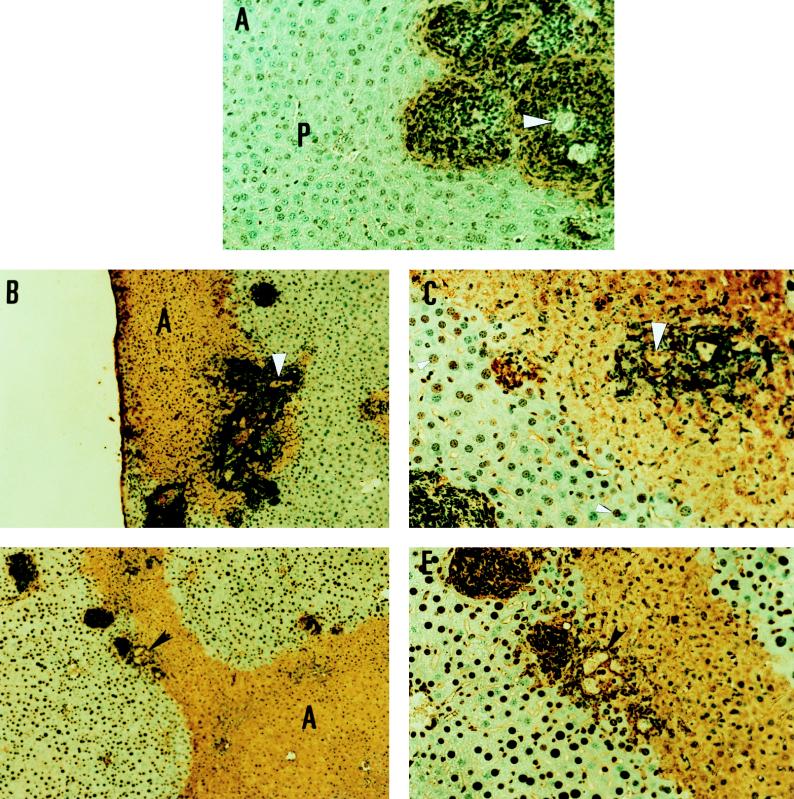

To confirm that apoptosis was occurring in hepatocytes in amebic liver abscesses, we performed terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining on sections from amebic liver abscesses in SCID mice. The cleavage of DNA by endogeneous DNases that occurs in apoptosis leads to the formation of free 3′ DNA hydroxyl groups that are substrates for the enzyme terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase, which can attach nucleotides to the free 3′ DNA hydroxy groups. In TUNEL staining, labeled nucleotides allow for the immunohistochemical detection of cells undergoing apoptosis. TUNEL staining was performed with an in situ cell death detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. As shown in Fig. 3, we found significant TUNEL staining of hepatocytes and inflammatory cells in areas of amebic liver abscess, which was most pronounced in areas immediately adjacent to amebic trophozoites. Staining of liver sections taken from regions of normal-appearing liver that were not proximal to amebic liver abscesses showed no TUNEL staining. No TUNEL staining of normal uninfected liver was seen, and there was no TUNEL staining detected in infected livers when terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase was omitted from the staining reaction (data not shown). The findings of both DNA laddering in genomic DNA and positive TUNEL staining indicate that E. histolytica infection induces apoptosis in hepatocytes in amebic liver abscess.

FIG. 3.

Apoptosis occurs in hepatocytes and inflammatory cells in amebic liver abscesses in SCID, C57BL/6.lpr, and C57BL/6.gld mice. (A) TUNEL staining of a section of an amebic liver abscess in a SCID mouse. Note intense staining (brown color) of inflammatory cells surrounding amebic trophozoites (arrowhead) and some TUNEL staining of adjacent hepatocytes. Most of the adjacent liver parenchyma (P) does not stain at this early time point (original magnification, ×400). (B) TUNEL staining of a section of amebic liver abscess from a C57BL/6 mouse infected 24 h previously. Note intense staining surrounding amebic trophozoites (arrowhead) and widespread TUNEL staining of hepatocytes in the abscess region (A) (original magnification, ×100). (C) Detail of the section showing amebic trophozoites from panel B. Note intense staining around E. histolytica trophozoites (large arrowhead), and note that some nuclei of hepatocytes in regions of morphologically normal-appearing liver proximal to the abscessed region display TUNEL staining (original magnification, ×400). (D) TUNEL staining of a section of amebic liver abscess from a C57BL/6.lpr mouse infected 24 h previously. Note intense staining surrounding amebic trophozoites (arrowhead) and the extensive regions of TUNEL staining of hepatocytes in the abscess (A) (original magnification, ×100). (E) Detail of the section showing amebic trophozoites from panel D. E. histolytica trophozoites (arrowhead) are surrounded by intensely staining inflammatory cells, and staining is also seen in abscess regions of morphologically abnormal hepatocytes (A) (original magnification, ×400).

Apoptotic death is an end point that can be reached via a variety of cellular signals, and we next attempted to determine whether the apoptotic death occurring in amebic liver abscess occurs via a Fas/Fas ligand and/or TNF receptor-mediated pathway. Fas and its ligand are cell surface molecules with single transmembrane domains, and ligation of Fas by its ligand leads to apoptotic death in a variety of physiologic and pathologic conditions, including the control of immune responses, autoimmunity, and hepatitis (9). Fas is expressed on hepatocytes at high levels, and liver cells have been shown to be highly sensitive to the induction of Fas-mediated apoptosis (1, 4, 10). To investigate the role of Fas and its ligand in the apoptosis seen with amebic liver abscess, we studied amebic liver abscesses in C57/BL6, C57/BL6.lpr, and C57/BL6.gld mice. C57/BL6.lpr mice possess the lpr mutation and fail to produce Fas protein (18), while C57/BL6.gld mice have a point mutation in the gld gene resulting in the expression of a non-functional Fas ligand (15). If the Fas/Fas ligand pathway plays an important role in the apoptosis seen in amebic liver abscess, there should be little or no apoptosis seen in amebic liver abscesses in C57/BL6.lpr and C57/BL6.gld mice, and any amebic liver abscess that develops should be smaller than abscesses in the C57/BL6 strain. To test this, we first compared the size of amebic liver abscesses in C57/BL6, C57/BL6.lpr, and C57/BL6.gld mice, 48 h after direct hepatic inoculation with E. histolytica trophozoites. The mean sizes of the amebic liver abscess (as measured by the percentage of liver occupied by abscess based on abscess weight) were not significantly different among C57/BL6 mice ([22 ± 5]% of liver abscessed; n = 9), C57/BL6.lpr mice ([20 ± 6]% of liver abscessed; n = 7), and C57/BL6.gld mice ([21 ± 8]% of liver abscessed; n = 3). Electrophoresis of genomic DNA obtained from regions of amebic liver abscess in C57/BL6, C57/BL6.lpr, and C57/BL6.gld mice revealed DNA laddering in all three samples (Fig. 2). TUNEL staining for apoptotic cells was positive in regions of amebic liver abscess in both C57/BL6 and C57/BL6.lpr mice (Fig. 3) as well as in the C57/BL6.gld strain (data not shown). Extensive areas of apoptosis were visible around E. histolytica trophozoites, and positive TUNEL staining could be detected in nuclei in morphologically normal-appearing hepatocytes adjacent to abscessed areas (Fig. 3C). Based on all these findings, we conclude that the Fas/Fas ligand system does not play a major role in the apoptotic death induced by E. histolytica trophozoites.

An alternative pathway for inducing apoptosis involves the interaction of TNF-α with TNF receptor I (TNFRI) (p55) (5, 16, 17). TNFRI is found on most nucleated cells and has been shown to play a role in the apoptotic death of hepatocytes during experimentally induced shock (8). We have found that TNF-α is detectable in mouse livers when they are infected with E. histolytica trophozoites (13), suggesting that the local production of high levels of TNF-α in response to E. histolytica could cause ligation of TNFRI on hepatocytes, resulting in apoptosis. To test this hypothesis, we used mice genetically engineered to lack TNFRI (graciously provided by Immunex Corporation, Seattle, Wash.). If the TNF-α–TNFRI pathway of apoptosis is important in amebic liver abscess, mice lacking TNFRI should show significantly decreased areas of hepatocyte death from apoptosis. We found that amebic liver abscesses from TNFRI knockout mice were no different in size from those from the congenic control strain (data not shown) and that electrophoretic analysis of genomic DNA from areas of amebic liver abscess in TNFRI knockout mice revealed DNA laddering (Fig. 2). TUNEL staining revealed extensive areas of apoptosis in amebic liver abscesses in TNFRI knockout mice, identical to that seen in C57BL6.lpr mice (data not shown). These data indicate that the apoptotic death seen with amebic trophozoite invasion of the liver is independent of the TNF-α-mediated pathway.

In this study, we have shown that at least a portion of the cell death seen in amebic liver abscess occurs by apoptosis of host cells. Induction of apoptosis was specific for E. histolytica, as inoculation of the nonpathogenic E. moshkovskii strain failed to cause apoptotic cell death. Our results are consistent with those obtained from an in vitro study where a murine myeloid cell line underwent apoptotic death when coincubated with E. histolytica trophozoites (12). How E. histolytica induces apoptosis in host hepatocytes remains unknown. Our studies indicate that it is not through the Fas/Fas ligand pathway or via a TNF-α-dependent pathway of apoptosis. One appealing candidate is the E. histolytica amebapore molecule (7), which could be playing a role similar to that of the Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin (6) or human NK lysins and granzymes in promoting apoptotic death (11). While coculture with E. histolytica trophozoites or the addition of purified amebapores to Jurkat or HL-60 cells did not induce DNA fragmentation in the target cells in one in vitro study, the promyelocytic cell lines used in those experiments may differ significantly from the hepatocytes and other cell types present in the liver in their susceptibility to E. histolytica-induced apoptosis (2). It remains to be experimentally tested whether a blockade of amebapore activity could alter apoptosis in amebic liver abscess.

The cooptation of the apoptotic pathway for cell killing could be an important pathogenesis factor for an invasive extracellular pathogen such as E. histolytica, which lyses cells to invade deep tissue layers. We have recently shown that the inflammatory response, specifically neutrophils, plays a role in the control of amebic liver abscess formation (14). Because apoptosis, as opposed to necrosis, generally fails to induce an inflammatory response, the use of apoptosis for the destruction of host cells could serve to reduce the inflammatory response and provide an advantage for E. histolytica survival within the host.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lynne Foster, Lei Wang, and Tonghai Zhang for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant AI-30084 and Research Career Development Award AI-01231 (S.L.S.) and NIH training grant 5T32AI-07172 (K.B.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Benedetti A, Jezequel A M, Orlandi F. Preferential distribution of apoptotic bodies in acinar zone 3 of normal human and rat liver. J Hepatol. 1988;7:319–324. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(88)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berninghausen O, Leippe M. Necrosis versus apoptosis as the mechanism of target cell death induced by Entamoeba histolytica. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3615–3621. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3615-3621.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cieslak P R, Virgin IV H W, Stanley S L., Jr A severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse model for infection with Entamoeba histolytica. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1605–1609. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galle P R, Hofmann W J, Walczak H, Schaller H, Otto G, Stremmel W, Krammer P H, Runkel L. Involvement of the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) receptor and ligand in liver damage. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1223–1230. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenblatt M S, Elias L. The type B receptor for tumor necrosis factor-α mediates DNA fragmentation in HL-60 and U937 cells and differentiation in HL-60 cells. Blood. 1992;80:1339–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jonas D, Walev I, Berger T, Liebetrau M, Palmer M, Bhakdi S. Novel path to apoptosis: small transmembrane pores created by staphylococcal alpha-toxin in T lymphocytes evoke internucleosomal DNA degradation. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1304–1312. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1304-1312.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leippe M. Ancient weapons: NK-lysin is a mammalian homolog to pore-forming peptides of a protozoan parasite. Cell. 1995;83:17–18. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leist M, Gantner F, Bohlinger I, Tiegs G, Germann P G, Wendel A. Tumor necrosis factor-induced hepatocyte apoptosis precedes liver failure in experimental murine shock models. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:1220–1234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagata S, Golstein P. The Fas death factor. Science. 1995;267:1449–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.7533326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogasawara J, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Adachi M, Matsuzawa A, Kasugal T, Kitamura Y, Itoh N, Suda T, Nagata S. Lethal effect of the anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nature. 1993;364:806–809. doi: 10.1038/364806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pena S V, Hanson D A, Carr B A, Goralski T J, Krensky A M. Processing, subcellular localization, and function of 519 (granulysin), a human late T cell activation molecule with homology to small lytic, granule proteins. J Immunol. 1997;158:2680–2688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ragland B D, Ashley L S, Vaux D L, Petri W A., Jr Entamoeba histolytica: target cells killed by trophozoites undergo DNA fragmentation which is not blocked by Bcl-2. Exp Parasitol. 1994;79:460–467. doi: 10.1006/expr.1994.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seydel, K. B., and S. L. Stanley, Jr. 1998. Unpublished observations.

- 14.Seydel K B, Zhang T, Stanley S L., Jr Neutrophils play a critical role in early resistance to amebic liver abscesses in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3951–3953. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3951-3953.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi T, Tanaka M, Brannan C I, Jenkins N A, Copeland N G, Suda T, Nagata S. Generalized lymphoproliferative disease in mice, caused by a point mutation in the Fas ligand. Cell. 1994;76:969–976. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tartaglia L A, Ayres T M, Wong G H W, Goeddel D V. A novel domain within the 55 kd TNF receptor signals cell death. Cell. 1993;74:845–853. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90464-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tartaglia L A, Rothe M, Hu Y-F, Goeddel D V. Tumor necrosis factor’s cytotoxic activity is signaled by the p55 TNF receptor. Cell. 1993;73:213–216. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90222-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Brannan C I, Copeland N G, Jenkins N A, Nagata S. Lymphoproliferation disorder in mice explained by defect in Fas antigen that mediates apoptosis. Nature. 1992;356:314–317. doi: 10.1038/356314a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]