Abstract

Turner syndrome (45,X) is caused by a complete or partial absence of a single X chromosome. Vascular malformations occur due to abnormal development of blood and/or lymphatic vessels. They arise from either somatic or germline pathogenic variants in the genes regulating growth and apoptosis of vascular channels. Aortic abnormalities are a common, known vascular anomaly of Turner syndrome. However, previous studies have described other vascular malformations as a rare feature of Turner syndrome and suggested that vascular abnormalities in individuals with Turner syndrome may be more generalized. In this study, we describe two individuals with co-occurrence of Turner syndrome and vascular malformations with a lymphatic component. In these individuals, genetic testing of the lesional tissue revealed a somatic pathogenic variant in PIK3CA – a known and common cause of lymphatic malformations. Based on this finding, we conclude that the vascular malformations presented here and likely those previously in the literature are not a rare part of the clinical spectrum of Turner syndrome, but rather a separate clinical entity that may or may not co-occur in individuals with Turner syndrome.

Keywords: Vascular malformation, Turner syndrome, PIK3CA-related vascular malformation, lymphatic malformation, mosaicism, theragnostics

Introduction:

Turner syndrome is a sex chromosome disorder, occurring in about 1 in 2000 to 1 in 2500 live female births, caused by the complete or partial absence of an X chromosome [Bondy and Group, 2007; Gravholt et al., 2017]. This syndrome is commonly associated with short stature, webbed neck, widely spaced nipples, and congenital heart disease such as coarctation of the aorta.

Vascular malformations such as “pedal hemangiomas” and ectatic vessels in the gastrointestinal tract have been described as part of the clinical spectrum of Turner syndrome[Weiss, 1988; Paller et al., 1983; Kucharska et al., 2018]. Vascular malformations form due to abnormal growth and development of blood and lymphatic vessels [Queisser et al., 2021]. Vascular malformations are commonly caused by somatic pathogenic variants in the genes that regulate growth and apoptosis of vascular channels[Queisser et al., 2021]. The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies provides a nomenclature for the diagnosis of vascular malformations, which is typically done by a combination of history, physical exam, pathology, genetics, and imaging [Wassef et al., 2015]. A previous study described the co-occurrence of other conditions in Turner syndrome and suggested evaluation for dual diagnosis in individuals with Turner syndrome and rare features[Jones et al., 2018].

Two individuals with Turner syndrome and vascular malformations presented to our clinic. Given the previous case series and common somatic causes of vascular malformations, we hypothesized that the vascular malformations were due to a secondary mosaic cause. In this study, we describe two individuals with co-occurrence of Turner syndrome and PIK3CA-related vascular malformations to confirm this association is due to dual diagnosis and is not a rare feature of Turner syndrome.

Methods:

Editorial Policies and Ethical Considerations: Individual 1 and 2 provided informed written consent for photo publication and individual 2 enrolled in a research study with the Center for Applied Genomics (CAG) that was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Institutional Review Board.

The Somatic Overgrowth and Vascular Malformations panel was used for both individuals [NCBI]. Briefly, targeted DNA capture of 34 genes, including PIK3CA, was performed via a custom-designed Agilent XT HS Target Enrichment System panel. The targeted regions include all coding exons and 10 bp of flanking intronic regions. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq with 150 bp paired end sequencing. Variant filtering and annotation was performed using Agilent SureCall software using chromosome build GRCh37. The limit of detection for the Somatic Overgrowth and Vascular Malformation panel for clinical reporting is 1% variant allele fraction (VAF) (at 1000x coverage with at least 10 unbiased reads) that is confirmed in a second run of the sample.

The exome libraries for individual 2 were made using Twist Human Core Exome Capture Kit (TWIST Bioscience). Sequencing was performed on NovaSeq 6000 sequencers (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) at CAG/CHOP. Data were analyzed using BWA-mem v0.7.12 for alignment and Picard v1.97 for PCR duplication removal. The resulted BAM file was fed to GATK/Queue v2.6.5 for germline variant calling and GATK/Mutect2 v4.1.4.0 for somatic variant calling. ANNOVAR and SnpEff were then used to functionally annotate the variants and collect minor allele frequency (MAF) data from 1000 Genomes Projects, ESP6500SI, ExAC, gnomAD, and Kaviar. Subsequent variant filtration and prioritization were based on MAF in either population dataset and function annotation, such as, nonsynonymous, exonic, splicing-altering, and frameshift. Subsequent gene prioritization was performed on the basis of deleterious prediction and biological relevance by referring to the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database and Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD). In a large cohort of participants with vascular anomalies published by our group, the average coverage for deep exomes was 470x (128–1,030x) with the lowest VAF detected 2.3% [Li et al., 2023].

Data Sharing and Data Accessibility: The data that support this study are presented in the figures. Data from the clinical testing is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. Exome data for individual 2 is available from the authors upon request.

Case Reports:

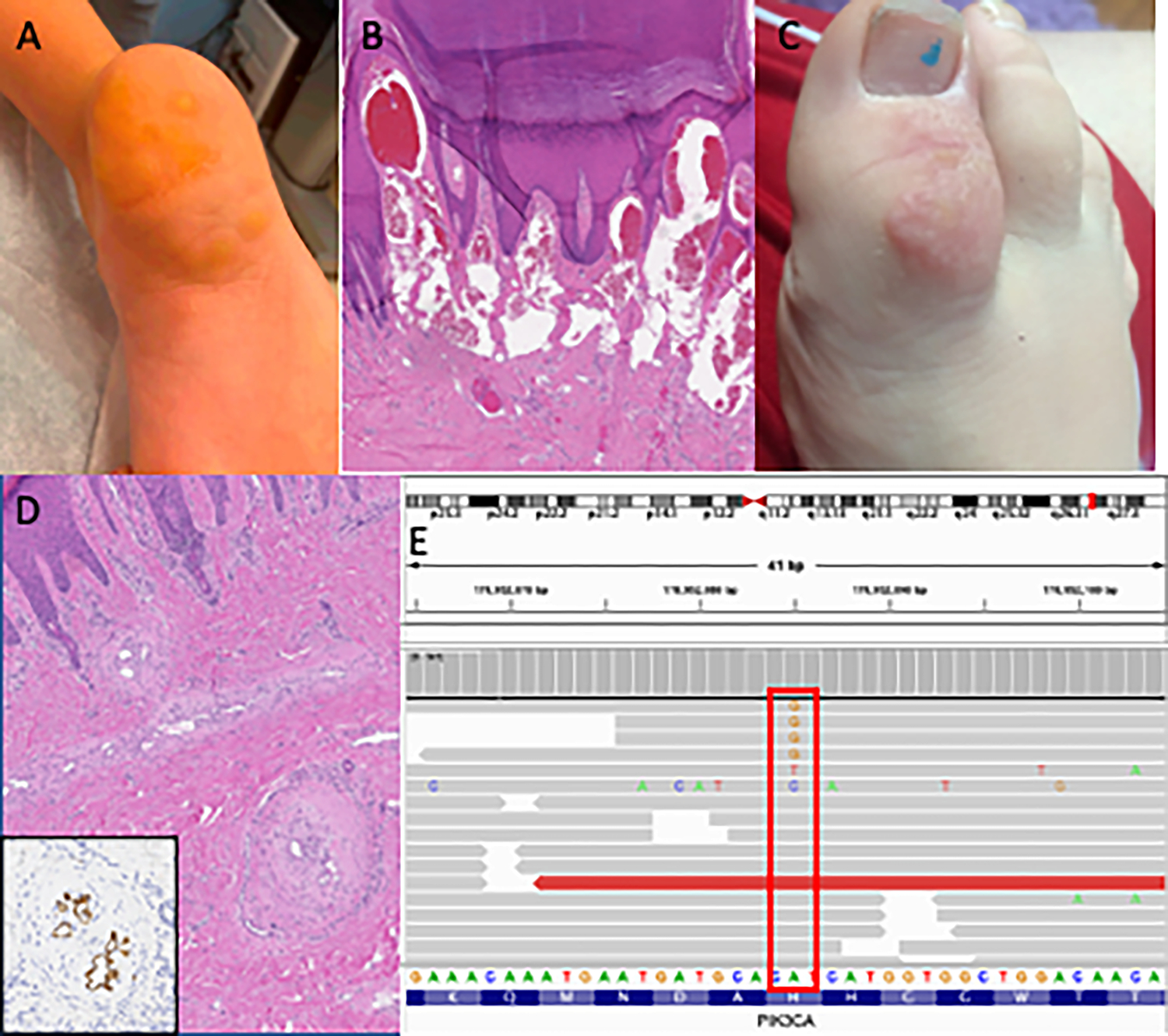

Individual 1 is an 11-year-old female with a combined lymphatic-venous malformation of the right foot, lymphedema, and Turner Syndrome. The pregnancy was complicated by increased nuchal translucency. She was noted to have lymphedema of the hands and feet, and extra nuchal skin at birth. Karyotype and FISH for X and Y chromosomes confirmed 45,X.

She was born with flesh-colored nodules on the plantar surface of her right foot (Figure 1A). Around 5 years old, the posterior nodule on her became reddish and then blackish and was excised. Pathology from the excision revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and multiple red blood cell-containing thin-walled dilated channels predominantly in the superficial dermis (Figure 1B). The endothelial lining stained strongly positive for CD31 with focal positivity for D2–40 and was negative for GLUT-1, suggestive of lymphatic origin.

Figure 1:

Photography, pathology, and genetic results for individual 1. A) Flesh colored nodules on the heel of right foot at 10 y.o. B) Biopsy of heel lesion showing hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and dilated thin-walled channels in the superficial dermis. C) Vascular lesion on right great toe before graft at 8 y.o. D) Resection of toe lesion with showing thick-walled, tortuous vessels with multiple lumina containing D2–40 positive endothelium (inset). E) Integrative genomics viewer screenshot of the sequencing data showing A to G change from the heel lesion.

Three years later, at age eight, she was seen again for a vascular lesion of her right great toe (Figure 1C). Debulking procedure was done for the lesion on her right great toe in addition to a split thickness skin graft from her buttock to her right great toe. Pathology of tissue from this lesion revealed irregular and tortuous thick and thin-walled channels within the dermis with irregular luminal “fenestrations” or plexiform-type lesions. These types of changes are most similar to that seen in vessel re-canalization post thrombosis or are akin to the plexiform lesions seen in pulmonary arterial hypertension. The endothelium of these vessels stained positive for both CD31 and D2–40, supporting lymphatic origin. The thick smooth muscle lining of the vessels was highlighted by SMA and h-caldesmon. Based on morphology and immunophenotype, the pathology for both the heel and the great toe sample were consistent with a combined vascular malformation containing both lymphatic and venous components.

Somatic Overgrowth and Vascular Malformation panel performed on genomic DNA isolated from the original heel tissue sample revealed a pathogenic PIK3CA variant (c.3140A>G, p.His1047Arg) with a variant allele frequency of 0.7–1.0% (9 out of 1320 reads; 12 out of 1116 reads) (Figure 1E). The p.His1047Arg variant is a recurrent pathogenic variant found in lymphatic malformations and has an allele frequency of 0.000004028 in gnomAD [Brouillard et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022].

Individual 2 is a three-year-old female with Turner syndrome diagnosed by chorionic villus sampling due to cystic hygroma. At birth, she was noted to have a lesion on the foot which was thought to be a bruise due to the emergency C-section. When this did not resolve, it was then thought to be a congenital hemangioma. She was referred to our Comprehensive Vascular Anomalies Clinic at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for diagnosis and treatment of the foot lesion at fifteen months of age. Physical exam was notable for long eyelashes, a flared medial eyebrow, and dorsal area of the left foot with overlying patchy port wine stains, angiokeratomas, and soft tissue hypertrophy and plantar surface with similar crusting and ulceration (Figure 2A,B). Intralesional bleomycin sclerotherapy and concurrent tissue biopsy for genetic testing was recommended. MRI with contrast and ultrasound revealed fatty hypertrophy of the dorsal aspect of the left foot intermixed with a microcystic lymphatic malformation (Figure 2C,D). Somatic Overgrowth and Vascular Malformation panel was performed on genomic DNA isolated from lesional tissue biopsy identified a pathogenic PIK3CA variant (c.3140 A>G, p.His1047Arg) with a 3.1% VAF (46 out of 1473 reads) (Figure 2E). Research deep exome sequencing revealed the same somatic variant at a VAF of 4.1% (16 out of 389 reads). Although the lymphatic malformation initially improved following sclerotherapy, she experienced worsening pain, swelling, and bleeding at the foot especially during weight bearing 6 months post-sclerotherapy. Around 30 months of age, she started sirolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, at 0.39 mg by mouth twice per day. After six months of therapy, she had decreased pain, ulceration, and size of the lesion.

Figure 2:

Photography, imaging, and genetic results for individual 2. A) Photo of feet 7 months after sclerotherapy before initiation of sirolimus. B) Photo of feet 14 months after photo C and 8 months after taking Sirolimus. C) MRI of the left foot before sclerotherapy and initiation of Sirolimus. D) MRI of the left foot 11 months later after sclerotherapy and 3 months of taking Sirolimus showing decrease in microcystic lymphatic malformation (arrows) but continued fatty overgrowth. E) Integrative genomics viewer screenshot of the sequencing data showing A to G change.

Discussion:

A co-occurring genetic disorder has been reported in 152 individuals with Turner Syndrome[Jones et al., 2018]. The majority (31%) of individuals had Down syndrome as the most common co-occurring genetic condition[Jones et al., 2018]. Other genetic conditions reported in individuals with Turner syndrome include Fragile X syndrome, hemophilia and muscular dystrophy [Jones et al., 2018]. However, there were no individuals with a mosaic vascular malformation previously reported. The co-occurrence of lymphatic-venous and lymphatic malformations in these two individuals with Turner syndrome led us to hypothesize that the vascular malformations were due to a secondary mosaic cause. Indeed, we discovered that these vascular malformations are due to mosaic pathogenic variants in PIK3CA, a well known cause of lymphatic malformations[Zenner et al., 2019; Luks et al., 2015; Brouillard et al., 2021].

Vascular malformations have also been reported to co-occur in Turner syndrome[Weiss, 1988; Paller et al., 1983], though a complicating factor is the many of these reports were prior to or around the time that classification of hemangiomas and vascular malformations was changed to be based on endothelial characteristics [Mulliken and Glowacki, 1982] and prior to the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies classification[Wassef et al., 2015]. Four individuals with Turner syndrome and “pedal hemangiomas” were described with varying features, though Bushkell and colleagues questioned whether these were true hemangiomas and possibly could be related to vascular ectasia of the skin[Bushkell and Broughton, 1984]. Weiss et al described two individuals with Turner syndrome and “pedal hemangiomas” though histologically the malformations could be considered “venous hemangiomas”[Weiss, 1988]. Dr. Weiss proposed that these were in fact malformations (rather than a vascular tumor which is what a hemangioma is considered) and that more generalized vascular anomalies could be part of the spectrum of Turner syndrome[Weiss, 1988]. We would agree with Dr. Weiss as the descriptions were not consistent with hemangiomas nor were the biopsies. Indeed, the features of the toe lesion of individual 1 closely resemble those described by Weiss; however, immunohistochemical data was not provided in her description[Weiss, 1988]. There was another individual with Turner syndrome and angiokeratoma of the foot, which was D2–40 positive on pathology (typically a marker of lymphatic endothelium)[Berk et al., 2010]. Finally, one additional individual was reported with a left subclavian cystic lymphangioma (now known as a lymphatic malformation), but no genetic testing was performed on that sample[Gaertner et al., 2016].

We hypothesize that if genetic testing was performed on the biopsies from the previous case studies, somatic pathogenic variants may have been found as the cause of the vascular malformations. Vascular malformations of the gastrointestinal tract resulting in bleeding are also described as a rare feature of Turner syndrome [Kucharska et al., 2018; Witkowska-Krawczak et al., 2021; Bang and Peter, 2013]. In these individuals, further genetic characterization is needed to evaluate for secondary causes, such as Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia, as previously recommended [Jones et al., 2018].

We evaluated the prevalence of vascular malformations in the Turner syndrome population seen at CHOP. From Jan 2020-July 2022, there were 345 individuals with Turner syndrome seen at CHOP which leads to prevalence of 2 in 345. This is similar to what would be expected, based on the prevalence of vascular malformations in 1.2% of the population [Tasnadi, 2009]. Future work studying the natural history of lymphatic anomalies may allow us to investigate this further.

Determination of additional genetic causes have important clinical implications, especially in the current era of theragnostics [Queisser et al., 2021]. Recently, there have been many advances in the use of targeted inhibitors for treatment of vascular malformations. Sirolimus led to a partial response in 82% of participants with complicated vascular anomalies[Adams et al., 2016]. In individual 2, the discovery of PIK3CA mosaicism as a secondary cause for the lymphatic malformation led to the addition of sirolimus. Notably, she had clinical improvement after the initiation of sirolimus. She will be eligible for alpelisib, a selective PI3Kα inhibitor, if there is worsening of disease[Venot et al., 2018; Delestre et al., 2021].

In summary, we report the co-occurrence of PIK3CA-related vascular malformations with Turner syndrome to conclude that generalized vascular anomalies are not part of the spectrum of Turner syndrome.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the individuals and their families for participating in this manuscript. The authors thank the Comprehensive Vascular Anomaly Program for clinical care. The work was supported by a Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Frontier Program Grant Research (DMA, HH). SES is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under award number HD009003–01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Dr. Hakonarson and CHOP are equity holders in Nobias Therapeutics Inc., developing MEK inhibitor therapy for complex lymphatic anomalies. Dr. Adams is a consultant for Novartis and Nobias and Dr. Snyder are consultants for Novartis Pharmaceuticals, which makes Vijoice (alpelisib), a selective PI3Kα inhibitor.

References:

- Adams DM, Trenor CC, Hammill AM, Vinks AA, Patel MN, Chaudry G, Wentzel MS, Mobberley-Schuman PS, Campbell LM, Brookbank C, Gupta A, Chute C, Eile J, McKenna J, Merrow AC, Fei L, Hornung L, Seid M, Dasgupta AR, Dickie BH, Elluru RG, Lucky AW, Weiss B, Azizkhan RG. 2016. Efficacy and Safety of Sirolimus in the Treatment of Complicated Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 137: e20153257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang JY, Peter S. 2013. GI Bleed in Turner Syndrome. Digest Endosc 25: 462–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk DR, Lind AC, Bayliss SJ. 2010. Acral Angiokeratomas in a Patient with Turner Syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol 27: 662–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy CA, Group TSS. 2007. Care of Girls and Women with Turner Syndrome: A Guideline of the Turner Syndrome Study Group. The J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92: 10–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillard P, Schlögel MJ, Sepehr NH, Helaers R, Queisser A, Fastré E, Boutry S, Schmitz S, Clapuyt P, Hammer F, Dompmartin A, Weitz-Tuoretmaa A, Laranne J, Pasquesoone L, Vilain C, Boon LM, Vikkula M. 2021. Non-hotspot PIK3CA mutations are more frequent in CLOVES than in common or combined lymphatic malformations. Orphanet J Rare Dis 16: 267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushkell LL, Broughton RA. 1984. Pedal hemangiomas versus vascular ectasia in Turner syndrome. J Pediatrics 104: 486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Francioli LC, Goodrich JK, Collins RL, Kanai M, Wang Q, Alföldi J, Watts NA, Vittal C, Gauthier LD, Poterba T, Wilson MW, Tarasova Y, Phu W, Yohannes MT, Koenig Z, Farjoun Y, Banks E, Donnelly S, Gabriel S, Gupta N, Ferriera S, Tolonen C, Novod S, Bergelson L, Roazen D, Ruano-Rubio V, Covarrubias M, Llanwarne C, Petrillo N, Wade G, Jeandet T, Munshi R, Tibbetts K, Consortium gnomAD P, O’Donnell-Luria A, Solomonson M, Seed C, Martin AR, Talkowski ME, Rehm HL, Daly MJ, Tiao G, Neale BM, MacArthur DG, Karczewski KJ. 2022. A genome-wide mutational constraint map quantified from variation in 76,156 human genomes. bioRxiv: 2022.03.20.485034. [Google Scholar]

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, Fraissenon A, Ladraa S, Hoguin C, Chapelle C, Yamaguchi J, Cassaca R, Zerbib L, Magassa S, Morin G, Asnafi V, Villarese P, Kaltenbach S, Fraitag S, Duong J-P, Broissand C, Boccara O, Soupre V, Bonnotte B, Chopinet C, Mirault T, Legendre C, Guibaud L, Canaud G. 2021. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med 13: eabg0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner S, Jeandidier N, Glasser L, Ohl J, Trinh A, Stephan D. 2016. Turner’s syndrome: is there a risk of widespread vascular abnormalities? Clin Endocrinol 84: 634–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravholt CH, Andersen NH, Conway GS, Dekkers OM, Geffner ME, Klein KO, Lin AE, Mauras N, Quigley CA, Rubin K, Sandberg DE, Sas TCJ, Silberbach M, Söderström-Anttila V, Stochholm K, derVelden JA van A, Woelfle J, Backeljauw PF, Group ITSC. 2017. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: proceedings from the 2016 Cincinnati International Turner Syndrome Meeting. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 177: G1–G70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, McNamara EA, Longoni M, Miller DE, Rohanizadegan M, Newman LA, Hayes F, Levitsky LL, Herrington BL, Lin AE. 2018. Dual diagnoses in 152 patients with Turner syndrome: Knowledge of the second condition may lead to modification of treatment and/or surveillance. Am J Med Genet A 176: 2435–2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska A, Józefczuk P, Ksiązyk M, Labochka D, Banaszkiewicz A. 2018. Gastrointestinal Vascular Malformations in Patients with Turner’s Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Horm Res Paediat 90: 39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Sheppard SE, March ME, Battig MR, Surrey LF, Srinivasan AS, Matsuoka LS, Tian L, Wang F, Seiler C, Dayneka J, Borst AJ, Matos MC, Paulissen SM, Krishnamurthy G, Nriagu B, Sikder T, Casey M, Williams L, Rangu S, O’Connor N, Thomas A, Pinto E, Hou C, Nguyen K, Silva RP da, Chehimi SN, Kao C, Biroc L, Britt AD, Queenan M, Reid JR, Napoli JA, Low DM, Vatsky S, Treat J, Smith CL, Cahill AM, Snyder KM, Adams DM, Dori Y, Hakonarson H. 2023. Genomic profiling informs diagnoses and treatment in vascular anomalies. Nat. Med: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luks VL, Kamitaki N, Vivero MP, Uller W, Rab R, Bovée JVMG, Rialon KL, Guevara CJ, Alomari AI, Greene AK, Fishman SJ, Kozakewich HPW, Maclellan RA, Mulliken JB, Rahbar R, Spencer SA, Trenor CC, Upton J, Zurakowski D, Perkins JA, Kirsh A, Bennett JT, Dobyns WB, Kurek KC, Warman ML, McCarroll SA, Murillo R. 2015. Lymphatic and Other Vascular Malformative/Overgrowth Disorders Are Caused by Somatic Mutations in PIK3CA. J Pediatrics 166: 1048–1054.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. 1982. Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations in Infants and Children. Plast Reconstr Surg 69: 412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCBI. Somatic Overgrowth and Vascular Malformations Gene Panel.

- Paller AS, Esterly NB, Charrow J, Cahan FM. 1983. Pedal hemangiomas in Turner syndrome. J Pediatrics 103: 87–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queisser A, Seront E, Boon LM, Vikkula M. 2021. Genetic Basis and Therapies for Vascular Anomalies. Circ Res 129: 155–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasnadi G 2009. Epidemiology of Vascular Malformations. In: Mattassi R, Loose DA, Vaghi M, editors. Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations, 1e. Springer; Milano, p 109–110. [Google Scholar]

- Venot Q, Blanc T, Rabia SH, Berteloot L, Ladraa S, Duong J-P, Blanc E, Johnson SC, Hoguin C, Boccara O, Sarnacki S, Boddaert N, Pannier S, Martinez F, Magassa S, Yamaguchi J, Knebelmann B, Merville P, Grenier N, Joly D, Cormier-Daire V, Michot C, Bole-Feysot C, Picard A, Soupre V, Lyonnet S, Sadoine J, Slimani L, Chaussain C, Laroche-Raynaud C, Guibaud L, Broissand C, Amiel J, Legendre C, Terzi F, Canaud G. 2018. Targeted therapy in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome. Nature 558: 540–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassef M, Blei F, Adams D, Alomari A, Baselga E, Berenstein A, Burrows P, Frieden IJ, Garzon MC, Lopez-Gutierrez J-C, Lord DJE, Mitchel S, Powell J, Prendiville J, Vikkula M, Committee IB and S. 2015. Vascular Anomalies Classification: Recommendations From the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 136: e203–e214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SW. 1988. Pedal hemangioma (venous malformation) occurring in Turner’s syndrome: An additional manifestation of the syndrome. Hum Pathol 19: 1015–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkowska-Krawczak E, Zapolska A, Banaszkiewicz A, Kucharska A. 2021. Recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding due to vascular malformations in a girl with Turner syndrome. Pediatric Endocrinol Diabetes Metabolism. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenner K, Cheng CV, Jensen DM, Timms AE, Shivaram G, Bly R, Ganti S, Whitlock KB, Dobyns WB, Perkins J, Bennett JT. 2019. Genotype correlates with clinical severity in PIK3CA-associated lymphatic malformations. JCI Insight 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]