Abstract

Damage to erythrocyte membranes by botulinolysin (BLY) was studied by electron microscopy, which revealed ring-shaped structures with inner diameters and widths of approximately 32 and 6.7 nm, respectively. BLY bound to membranes at 0°C, but subsequent treatment with glutaraldehyde prevented ring formation during further incubation at 37°C. Zn2+ ions inhibited ring formation but not binding of BLY to membranes.

Botulinolysin (BLY) is an oxygen-labile hemolysin produced by Clostridium botulinum (1–4, 13) that is a member of the family of thiol-activated cytotoxins (1–4, 32, 34). This family consists, at present, of about 20 different toxins that are produced by four genera of gram-positive bacteria, namely, Streptococcus, Bacillus, Clostridium, and Listeria (1–4, 8, 10, 27, 34). Formation of ring-shaped and arc-shaped structures has been observed under the electron microscope on erythrocyte membranes that have been treated with some of these toxins (5, 11, 12, 20, 24, 29). Members of our group reported a molecular model for the formation of rings on erythrocyte membranes by streptolysin O (SLO) from Streptococcus pyogenes (29). The various toxins bind cholesterol and their cytolytic activity is inhibited by treatment with cholesterol (12, 15, 16, 20, 31). Recently, the three-dimensional structure of perfringolysin O (PFO; θ-toxin), another thiol-activated cytolysin, was reported, and the fine structures of the cholesterol-binding site and of the region required for formation of oligomers were described (28). Thiol-activated toxins have potent lytic activity against mammalian cells and other eukaryotic cells (3, 35). Purified BLY also has a lethal effect on mice and a cytotoxic effect on Vero cells (13, 33). Thus, membrane damage by thiol-activated toxins might play an important role in the pathogenesis (9) of various diseases if the causative microorganisms produce thiol-activated cytolysins. We are interested in the similarities and differences between toxins from different genera, and we are attempting to clarify the characteristics of various toxins. In this study, we examined the fine-structural changes in erythrocyte membranes induced by BLY, focusing on the formation of ring-shaped structures, as part of an effort to elucidate the mechanism of membrane damage by BLY of erythrocyte membranes.

BLY was purified as described by Haque et al., with slight modification (13). The hemolytic activity of BLY was expressed as the 50% hemolytic dose per microgram of protein. The specific activity of our preparation of BLY was approximately 1,500 hemolytic units (HU)/μg of protein with rabbit erythrocytes as the assay material. Erythrocyte and ghost membranes were prepared from rabbit erythrocytes by the previously described method, with slight modification (29, 30). Preparations of membranes that had been treated with BLY as described below were washed with physiological saline (Ohtsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan), fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 min, washed with distilled water (DW; Ohtsuka Pharmaceutical Co.), and negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid. Specimens were observed under a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi H-500, JEOL 2000 EX, JEM 1010, or Carl Zeiss CEM-902A).

Sizes and structures of BLY rings on erythrocyte membranes.

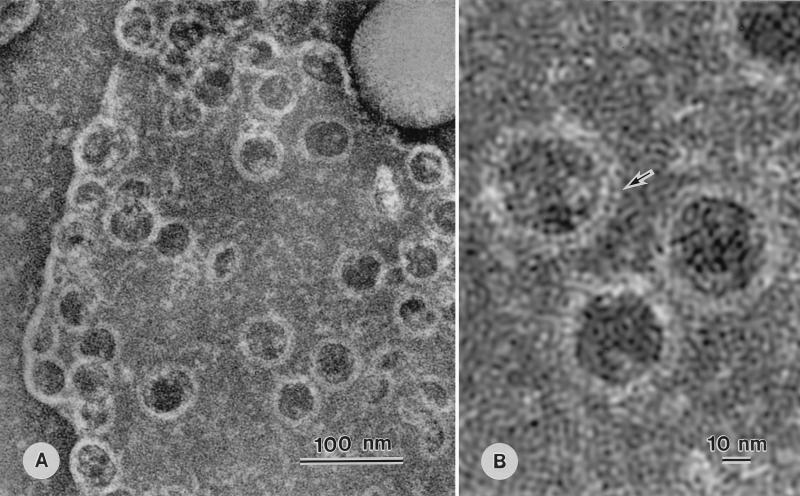

Twenty microliters of a 10% suspension of erythrocytes that had been diluted with physiological saline was mixed with 10 μl of BLY (170,000 HU/ml) in a test tube. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Then 10 μl of the mixture of lysed erythrocytes was dropped onto 100 μl of DW on Sealon film (Fuji Film Co., Tokyo, Japan) and mixed gently with a micropipette. After 30 to 40 min, the membrane fragments that floated at the air-water interface were mounted on supporting Butval-98 films (Nissin EM, Tokyo, Japan) on a grid for electron microscopy. Negative staining of erythrocyte membranes treated with BLY revealed numerous ring-shaped structures (BLY rings [Fig. 1A]). Semicircular structures were also observed. The inner diameters of BLY rings were 32 ± 2.4 nm (n = 50), as determined from radii of semicircular rings, and the rings themselves were 6.7 ± 0.6 nm (n = 50) wide, as observed in the case of SLO rings. The dimensions of the rings, together with those of rings formed by other toxins, are summarized in Table 1. Higher magnification revealed a double-layered structure (29, 30) (Fig. 1B). Crown-shaped structures (29) were also observed on rings at folded edges of erythrocyte membranes (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Electron micrographs of rings formed on an erythrocyte membrane that had been treated with BLY at 37°C for 5 min. Note rings with pores in panel A and double-layered structures indicated by the arrow in panel B.

TABLE 1.

Dimensions of rings

| Toxin | Width (nm) | Inner diam (nm) | Outer diam (nm) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLY | 6.7 | 32 | 45 | |

| SLO | 7–8 | 26 | 33–34 | 6, 7 |

| 7 | 24 | 34 | 12 | |

| 5 | 24 | 34 | 29 | |

| PFO | 5 | 24 | 34 | 19, 20 |

| 6 | 30 | 42 | 25 | |

| PLYa | 6.5 | 17–32 | 30–45 | 22 |

PLY, pneumolysin.

Effects of temperature on binding and formation of pores by BLY on erythrocyte membranes.

Ghost membranes were thawed at room temperature after storage at −80°C. Floating ghost membranes on the surface of DW were prepared as described previously (23, 29) and mounted on supporting Butval-98 films on a grid. Purified BLY was diluted 25-fold with 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) that contained 0.85% NaCl and 5 mM cysteine (Tris NaCl-cysteine buffer). The ghost membranes on supporting films were treated with 10 μl of diluted BLY (6,800 HU/ml). After the treatment with BLY at room temperature for 3 to 5 min, we observed numerous BLY rings (results resembled those in Fig. 1A). By contrast, we observed no ring-shaped structures on ghost membranes treated with BLY at 0°C (data not shown). Binding of BLY to ghost membranes was confirmed by immunogold labeling with a pooled preparation of four mouse monoclonal antibodies against BLY that had almost the same affinities. For visualization, we used 5-nm-diameter colloidal-gold-conjugated goat antibodies against mouse immunoglobulin G (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, Calif.) (data not shown). Controls were treated with only gold-conjugated second antibody, and no gold particles were found on the membranes. Rings with pores formed on membranes that had been incubated with BLY at 0°C for 3 to 5 min, washed to remove excess BLY, and then incubated at 37°C for 1 min (results resembled those in Fig. 1A).

Effects of glutaraldehyde on pore formation.

When ghost membranes were treated with BLY at 0°C for 3 to 5 min, fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde at 0°C for 1 min, and then incubated at 37°C for 1 to 3 min, we observed very few BLY rings on the membranes (data not shown). However, BLY formed numerous rings with pores on membranes that had been fixed with glutaraldehyde for 1 min before exposure to BLY at room temperature for 5 min (results resembled those in Fig. 1A).

Effects of Zn2+ ions on pore formation.

When the preparation of BLY was diluted with Tris NaCl-cysteine buffer that contained 10 mM Zn2+ ions and applied to membranes at room temperature for 5 min, no BLY rings were observed. However, gold particles were found on these membranes after immunogold labeling (data not shown).

We confirmed that the binding of BLY to membranes was temperature independent, as it is in the two-step theory (14, 26, 30) proposed previously to explain the formation of SLO rings on erythrocyte membranes. BLY molecules bound to membranes at 0°C and then oligomerized to form rings with an increase in incubation temperature. The higher fluidity of lipid bilayers at higher temperatures might allow BLY to move on erythrocyte membranes, oligomerize, and finally form pores. When erythrocyte membranes with bound BLY were fixed with glutaraldehyde, no BLY rings were observed, even after incubation at 37°C. The mobility of BLY molecules on membranes might be affected by glutaraldehyde, which might denature BLY or form bridges between BLY molecules or between BLY and other components of the membrane. BLY did, however, form rings with pores when membranes were treated with glutaraldehyde prior to incubation with BLY. Proteins or amine residues in erythrocyte membranes might not be involved directly in the formation of BLY rings.

Sekiya et al. proposed a double-layer SLO ring model composed of about 50 SLO molecules (29). Morgan et al. (21, 22) reported that pneumolysin forms single-layer rings composed of 40 to 50 subunits, with each subunit having four domains. PFO rings also seem to be composed of about 50 PFO molecules (25). Although there is some discrepancy among the models, the number of molecules in each ring is almost the same. The molecular weight of BLY is 58,000 (13) and is close to those estimated for SLO (53,000 and 60,000 [3, 17]). Since the diameter of BLY rings, 47 nm, is larger than that of SLO rings, 36 nm (5, 29), BLY rings might be composed of more than 50 BLY molecules.

Zn2+ ions at 5 to 10 mM prevented pore formation by BLY, as well as by PFO (18), but binding of BLY to membranes was unaffected. Ca2+, Co2+, and Mg2+ ions also blocked pore formation (data not shown). Menestrina et al. (18) reported that lysis by PFO was inhibited by divalent cations in the order, from greatest to least inhibition, of Zn2+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+. They proposed that inhibition by Zn2+ ions might be due, at least in part, to the promotion and maintenance of pore closure. Once BLY has formed a semicircular (arc) structure on a membrane, the arc-shaped structure gradually increases in length to form a C shape or a ring. When the tension within the cell membrane on the concave side of the ring becomes greater than the repulsive force, the inside of the ring opens as a pore. It is unclear how Zn2+ ions and other divalent cations might prevent pore formation by BLY after BLY has bound to the membrane. The effects of metal ions on cytolytic toxins might provide a key to the mechanism of pore formation.

The results are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of results

| Procedurea | Formation of rings | Gold particles on membrane |

|---|---|---|

| BLY (RT) | + | |

| BLY (0°C) | − | |

| BLY (0°C) + FA + IM | − | + |

| BLY (0°C) + wash + 37°C | + | |

| BLY (0°C) + GA + 37°C | − | |

| GA + BLY (RT) | + | |

| BLY + 10 mM ZnSO4 (RT) | ||

| Alone | − | |

| + FA + IM | − | + |

RT, incubation at room temperature; 0°C, incubation at 0°C; FA, formaldehyde; IM, immunoelectron microscopy; GA, glutaraldehyde; 37°C, incubation at 37°C.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (06670303 and 08557002) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Project-11) from the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kitasato University, Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alouf J E. Cell membranes and cytolytic bacterial toxins. In: Cuatrecasas P, editor. Receptors and recognition, series B. 1. The specificity and action of animal, bacterial and plant toxins. London, England: Chapman and Hall; 1977. pp. 219–270. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alouf J E. Streptococcal toxins (streptolysin O, streptolysin S and erythrogenic toxin) Pharmacol Ther. 1980;11:661–717. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(80)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alouf J E, Geoffroy C. The family of the antigenically related cholesterol-binding (’sulfhydryl activated’) cytolytic toxins. In: Alouf J E, Freer J H, editors. Source book of bacterial protein toxins. London, England: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 147–186. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernheimer A W, Rudy B. Interactions between membranes and cytolytic peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;864:123–141. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(86)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhakdi S, Roth M, Sziegoleit A, Tranum-Jensen J. Isolation and identification of two hemolytic forms of streptolysin-O. Infect Immun. 1984;46:394–400. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.2.394-400.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J, Sziegoleit A. Mechanism of membrane damage by streptolysin-O. Infect Immun. 1985;47:52–60. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.1.52-60.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J. Damage to cell membranes by pore-forming bacterial cytolysins. Prog Allergy. 1988;40:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhakdi S, Weller U, Walev I, Martin E, Jonas D, Palmer M. A guide to the use of pore-forming toxins for controlled permeabilization of cell membranes. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1993;182:167–175. doi: 10.1007/BF00219946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhakdi S, Grimminger F, Suttorp N, Walmrath D, Seeger W. Proteinaceous bacterial toxins and pathogenesis of sepsis syndrome and septic shock: the unknown connection. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1994;183:119–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00196048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulnois G J, Paton J C, Mitchell T J, Andrew P W. Structure and function of pneumolysin, the multifunctional, thiol-activated toxin of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2611–2616. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowell J L, Kim K-S, Bernheimer A W. Alteration by cereolysin of the structure of cholesterol-containing membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;507:230–241. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan J L, Schlegel R. Effect of streptolysin O on erythrocyte membranes, liposomes, and lipid dispersions. A protein-cholesterol interaction. J Cell Biol. 1975;67:160–173. doi: 10.1083/jcb.67.1.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haque A, Sugimoto N, Horiguchi Y, Okabe T, Miyata T, Iwanaga S, Matsuda M. Production, purification, and characterization of botulinolysin, a thiol-activated hemolysin of Clostridium botulinum. Infect Immun. 1992;60:71–78. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.71-78.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hugo F, Reichwein J, Arvand M, Krämer S, Bhakdi S. Use of a monoclonal antibody to determine the mode of transmembrane pore formation by streptolysin O. Infect Immun. 1986;54:641–645. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.641-645.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs A A C, Loeffen P L W, van den Berg A J G, Storm P K. Identification, purification, and characterization of a thiol-activated hemolysin (suilysin) of Streptococcus suis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1742–1748. doi: 10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00034458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson M K, Geoffroy C, Alouf J E. Binding of cholesterol by sulfhydryl-activated cytolysins. Infect Immun. 1980;27:97–101. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.1.97-101.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehoe M A, Miller L, Walker J A, Boulnois G J. Nucleotide sequence of the streptolysin O (SLO) gene: structural homologies between SLO and other membrane-damaging, thiol-activated toxins. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3228–3232. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3228-3232.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menestrina G, Bashford C L, Pasternak C A. Pore-forming toxins: experiments with S. aureus α-toxin, C. perfringens θ-toxin and E. coli haemolysin in lipid bilayers, liposomes and intact cells. Toxicon. 1990;28:477–491. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(90)90292-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitsui K, Sekiya T, Nozawa Y, Hase J. Alteration of human erythrocyte plasma membranes by perfringolysin O as revealed by freeze-fracture electron microscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;554:68–75. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitsui K, Sekiya T, Okamura S, Nozawa Y, Hase J. Ring formation of perfringolysin O as revealed by negative stain electron microscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;558:307–313. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan P J, Hyman S C, Rowe A J, Mitchell T J, Andrew P W, Saibil H R. Subunit organization and symmetry of pore-forming, oligomeric pneumolysin. FEBS Lett. 1995;371:77–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00887-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan P J, Hyman S C, Byron O, Andrew P W, Mitchell T J, Rowe A J. Modeling the bacterial protein toxin, pneumolysin, in its monomeric and oligomeric form. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25315–25320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicolson G L, Singer S J. Ferritin-conjugated plant agglutinins as specific saccharide stains for electron microscopy: application to saccharide bound to cell membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:942–945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.5.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niedermeyer W. Interaction of streptolysin-O with biomembranes: kinetic and morphological studies on erythrocyte membranes. Toxicon. 1985;23:425–439. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(85)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olofsson A, Hebert H, Thelestam M. The projection structure of perfringolysin O. FEBS Lett. 1993;319:125–127. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer M, Valeva A, Kehoe M, Bhakdi S. Kinetics of streptolysin O self-assembly. Eur J Biochem. 1995;231:388–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parrisius J, Bhakdi S, Roth M, Tranum-Jensen J, Goebel W, Seeliger H P R. Production of listeriolysin by beta-hemolytic strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1986;51:314–319. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.1.314-319.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossjohn J, Feil S C, McKinstry W J, Tweten R K, Parker M W. Structure of a cholesterol-binding, thiol-activated cytolysin and a model of its membrane form. Cell. 1997;89:685–692. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekiya K, Satoh R, Danbara H, Futaesaku Y. A ring-shaped structure with a crown formed by streptolysin O on the erythrocyte membrane. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5953–5961. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5953-5961.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sekiya K, Danbara H, Yase K, Futaesaku Y. Electron microscopic evaluation of a two-step theory of pore formation by streptolysin O. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6998–7002. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6998-7002.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shany S, Bernheimer A W, Grushoff P S, Kim K-S. Evidence for membrane cholesterol as the common binding site for cereolysin, streptolysin O and saponin. Mol Cell Biochem. 1974;3:179–186. doi: 10.1007/BF01686643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smyth C J, Duncan J L. Thiol-activated (oxygen-labile) cytolysins. In: Jejaszewicz J, Wadstrom T, editors. Bacterial toxins and cell membranes. London, England: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 129–183. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugimoto N, Haque A, Horiguchi Y, Matsuda M. Botulinolysin, a thiol-activated hemolysin produced by Clostridium botulinum, inhibits endothelium-dependent relaxation of rat aortic ring. Toxicon. 1997;35:1011–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(97)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tweten R K. Pore-forming toxins of gram-positive bacteria. In: Roth J A, Bolin C A, Brogden K A, Minion F C, Wannemuehler M J, editors. Virulence mechanisms of bacterial pathogens. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 207–229. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walev I, Palmer M, Valeva A, Weller U, Bhakdi S. Binding, oligomerization, and pore formation by streptolysin O in erythrocytes and fibroblast membranes: detection of nonlytic polymers. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1188–1194. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1188-1194.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]