Abstract

Background and Aims:

Lung metastases are the most threatening signs for patients with aggressive hepatoblastoma (HBL). Despite intensive studies, the cellular origin and molecular mechanisms of lung metastases in patients with aggressive HBL are not known. The aims of these studies were to identify metastasis-initiating cells in primary liver tumors and to determine if these cells are secreted in the blood, reach the lung, and form lung metastases.

Approach:

We have examined mechanisms of activation of key oncogenes in primary liver tumors and lung metastases and the role of these mechanisms in the appearance of metastasis-initiating cells in patients with aggressive HBL by RNA-Seq, immunostaining, chromatin immunoprecipitation, Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR and western blot approaches. Using a protocol that mimics the exit of metastasis-initiating cells from tumors, we generated 16 cell lines from liver tumors and 2 lines from lung metastases of patients with HBL.

Results:

We found that primary HBL liver tumors have a dramatic elevation of neuron-like cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts and that these cells are released into the bloodstream of patients with HBL and found in lung metastases. In the primary liver tumors, the ph-S675-β-catenin pathway activates the expression of markers of cancer-associated fibroblasts; while the ZBTB3-SRCAP pathway activates the expression of markers of neurons via cancer-enhancing genomic regions/aggressive liver cancer domains leading to a dramatic increase of cancer-associated fibroblasts and neuron-like cells. Studies of generated metastasis-initiating cells showed that these cells proliferate rapidly, engage in intense cell-cell interactions, and form tumor clusters. The inhibition of β-catenin in HBL/lung metastases–released cells suppresses the formation of tumor clusters.

Conclusions:

The inhibition of the β-catenin-cancer-enhancing genomic regions/aggressive liver cancer domains axis could be considered as a therapeutic approach to treat/prevent lung metastases in patients with HBL.

INTRODUCTION

Aggressive hepatoblastoma (HBL) has been characterized by lung metastases, chemoresistance, and relapse. The molecular basis for HBL aggressiveness is not well understood. Lung metastases in patients with HBL can be detected at the time of diagnosis, or after the initial liver tumor has been removed as a relapse.1 A single-center study of many HBL cases with lung metastases discovered that systematic treatment of patients with HBL may prolong survival2,3; however, surgical excision of lung metastases is necessary for some patients with HBL who do not respond to chemotherapy.4 Examination of cholangiocarcinoma and HCC has provided some insight regarding cells with potential metastatic activity. It has been demonstrated that cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are responsible for the development of cholangiocarcinoma and metastases.5 In contrast to HCC, HBL has a low mutation rate, primarily in CTNNB1 and NRF2 genes, implying that other mechanisms may be important in aggressive HBL.6 Previously, we discovered that epigenetic alterations play a role in the development of aggressive HBL.7,8,9 One of these epigenetic modifications is the activation of genomic regions of DNA known as cancer-enhancing genomic regions or aggressive liver cancer domains (CEGRs/ALCDs), which have been identified in many oncogenes, including β-catenin, NRF2, WNT86, HACE1, and others.9,10 Using the unbiased Regulatory Element Locus Intersection (RELI) algorithm, we investigated mechanisms that open (activate) CEGRs/ALCDs, resulting in oncogene overexpression. Many transcription factors and chromatin remodelers were discovered to bind to CEGRs/ALCDs in a range of human malignancies, including HBL. Particularly, our recent reports showed that ph-S675-β-catenin is abundant in primary tumors of patients with fibrolamellar HCC and HBL and that it increases the expression of the oncogenes through the CEGRs/ALCDs axis.10,11

The portal tract, which includes the portal vein, hepatic arteria, and intrahepatic bile duct, is surrounded by intrahepatic nerve fibers.12,13 Although no reports describe the direct involvement of intrahepatic nerve fibers in liver cancers, there have been several publications detecting neuronal markers and neuron-like cells (cells expressing molecular markers for neurons) in liver tumors.14,15 Particularly, the nerve growth factor (NGF) is expressed in primary liver cancers.15 Critically, NGF regulates the polarity of cultured liver cancer cells, implying that it plays a significant role in invasion and metastasis.16 Another neuronal marker, NeuN (RBFOX3), has been shown to be elevated in patients with HCC and promotes lung metastases.17 Here we demonstrate the role of intrahepatic nerve fibers, neuronal-like cells, and CAFs in the development of lung metastases in patients with aggressive HBL.

METHODS

Pediatric patients with HBL

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at CCHMC (protocol number 2016-9497). Informed consent was obtained from each study patient, or their parents as indicated, before obtaining specimens. In this study, specimens from biorepository of 36 patients with HBL were used. Many of the patients with HBL in this study were diagnosed with lung metastases before or after primary surgery. Background regions are the sections of “healthy” portions of the liver of the same patients that are adjacent to the tumor section; tumor sections are labeled as “hepatoblastoma.”

Antibodies used in this study

β-catenin [Abcam; (E247) ab32572]; ph-S675-β-catenin (Cell Signaling Tech; #4176S); TCF4 (Cell Signaling, #C48H11), p300 (Invitrogen; PA1-848), p21 (Santa Cruz; sc-6246), HACE1 (Abcam; ab133637), cdc2 (Santa Cruz; sc-954), β-actin (Sigma; A5316). GPC3 (Abcam, ab216606), β-III tubulin (Abcam, ab18207), NeuN (Abcam, ab104225), NGF (Abcam, ab52918), α-SMA (Cell Signaling #14968), Collagen I polyclonal (Invitrogen; sc: PA5 29569), ZBTB3 (Abcam, ab106536), and SRCAP (Abcam, ab219181).

Cell-free-exit protocol for the generation of cells with metastatic activities

To isolate cells with potential metastatic activities (metastasis-initiating cells), we developed a methodology for cell line generation from HBL tumors. Small fragments of tumors were plated on collagen plates, and released cells were observed for several weeks (Figures 3A, B). During the first few days, we also evaluated cells in culture media by shifting the media to a new plate. At this stage, cancer cells are observed mainly in media (Supplemental Figure S3, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). We have examined hbl cells on passages 1–3. Typically, the exiting cells have a balance of CAFs and neuron-like cells around 50/50. This balance is stable within 3–5 passages.

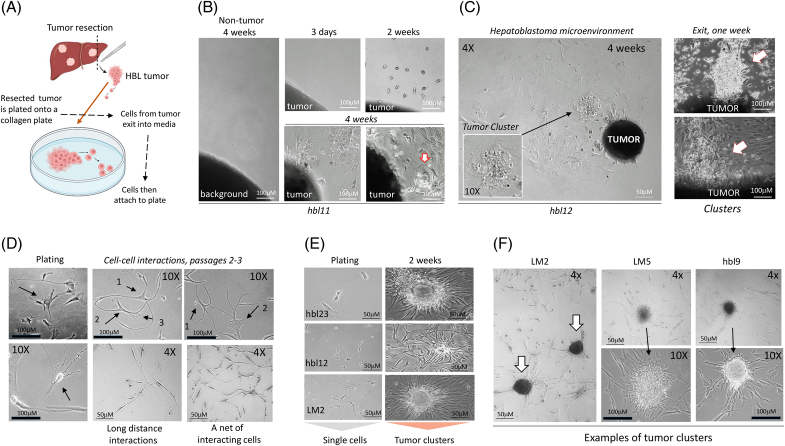

FIGURE 3.

Generation of tissue culture systems derived from rom patients with (HBL microenvironment) using a “cell-free-exit” protocol. (A) A diagram showing the “cell-free-exit” protocol. (B) Images of cells that are exiting HBL11 liver tumor at 3 days, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks after plating. (C) Left: A large area of the plate (4×) showing the exiting hepatoblastoma microenvironment around the attached liver tumor. A section with a tumor cluster is shown under 10×. Right: Additional images of exiting clusters observed in 1 week after plating. (D) Typical images of hbl cells (plating) and cell-cell interactions in microenvironments of generated hbl and LM cell lines. 10× images show interactions of 2–3 cells. 4× images show long-distance interactions. (E) hbl cell lines form tumor clusters at 10–14 days after plating. (F) Formation of tumor clusters by hbl lines 2 weeks after plating at low density. Scale bars=50–100 μM. Abbreviation: HBL, hepatoblastoma.

Culture of HepG2 cells

HepG2 cells were maintained in DMEM (Fisher Scientific 11-965-092) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum and penicillin/streptomycin in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described in our previous papers.10,11

List of TaqMan probes used in this study

ZBTB3 (Hs00227133_m1), SRCAP (Hs00198472_m1), ZBTB38 (Hs01053201_s1), ZBTB4 (Hs00394164_m1), CTNNB1 (Hs00355045_m1), TUBB3 (Hs00801390_s1), RBFOX3 (Hs01370653_m1), NGF (Hs00171458_m1), ACTA2 (Hs00426835_g1), Col1a1 (Hs00164004_m1), Col1a2 (Hs01028956_m1), and 18s (Hs03003631_g1).

Real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR

RNA was isolated using TRIzol/chloroform extraction. cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of RNA using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems 4387406) and diluted 5×. Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using TaqMan probes and TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems 4369016) and analyzed using the ΔΔCT method. Graphs of mRNA levels were made with GraphPad Prism 9.5.

Protein isolation, western blotting, and coimmunoprecipitation

Whole-cell extracts and nuclear extracts were prepared as described in our previous papers.8,9 Supplemental materials show whole gel images of western blots, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A765. Coimmunoprecipitation was performed using an improved True Blot protocol as described.7,8 Levels of the proteins were quantitated as ratios to β-actin using ImageJ software.

Pull-down assay

A biotinylated DNA oligomer containing the ZBTB3 binding site from CEGRs/ALCDs was linked to streptavidin beads and incubated with protein extracts isolated from background and tumor regions of HBL for 4 hours in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol. The beads were washed and proteins were eluted by 1% SDS in a sample buffer and examined by western blot with antibodies to ZBTB3 and SRCAP as described above.

RNA-Seq analysis of tissues from patients with HBL and hbl cells

Patients

Total RNA was extracted from fresh (immediately after surgery) tissues using the Trizol/chloroform extraction as described above.

Hbl and LM cells

Total RNA was isolated from cells using RiboZol (VWR) and processed as above. RNA-Seq was performed by the CCHMC DNA Sequencing and Genotyping. Analyses were performed on 2 paired-end samples using raw (>15 Gb) and trimmed data (>12 Gb), and the Q30 percentages of raw and trimmed data were >90% and >95%, respectively. Data were processed using kallisto (Pachter Lab), which accurately and rapidly assigns reads to genomic locations using pseudoalignment, with transcripts per million (TPM) as output. All reasonably-expressed transcripts (TPM>3 in >20% of samples) were included in statistical analyses, which included moderated t tests with significance defined as p<0.05 and fold change >2.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed as described7,8,9 using the ChIP-IT express enzymatic kit (Active Motif 53009).

Locations of CEGRs/ALCDs within corresponding genes

For gene-specific locations, CEGRs/ALCDs sequences were compared against the Homo sapiens GRCh 38 genome build using NCBI nucleotide BLAST.

Statistical analysis

All continuous values are presented as mean+SEM using GraphPad Prism 9.0. Student t tests and one-way ANOVA analyses were performed as appropriate, and p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A member of the ZBTB family, ZBTB3, binds to CEGRs/ALCDs and is elevated in aggressive HBL

Preceding studies have identified genomic regions of human DNA that promote oncogene expression in aggressive HBL.7,8,9,10,11,12 Since the RELI algorithm identified ZBTB3 as a protein that frequently binds to CEGRs/ALCDs,10 we searched the CEGRs/ALCDs and found a perfect binding site for ZBTB3 (Figure 1A). ZBTB3 has previously been identified as an oncogene**** exhibiting oncogenic activity when it forms complexes with the chromatin remodeling protein SRCAP.18 Through the RELI algorithm, SRCAP was also identified as a protein that binds to CEGRs/ALCDs.10 qRT-PCR revealed that the expression of ZBTB3, SRCAP, and 2 other neuronal markers (ZBTB38 and ZBTB4) were elevated in 60%–70% of patients with HBL within our biorepository (Figure 1A, right). Western blotting confirmed the elevation of ZBTB3 and SRCAP proteins in the majority of these same HBL samples (Figure 1B). Calculations of ZBTB3 and ZRCAP proteins as ratios to β-actin revealed that the levels of increase of these proteins are variable, yet significantly different. There is a strong correlation between patients with elevated levels of ZBTB3 and elevated levels of SRCAP (Figure 1B). Coimmunoprecipitation showed that ZBTB3 and SRCAP form complexes in HBL tumors and HepG2 cells (Figure 1C). Size exclusion chromatography revealed that ZBTB3-SRCAP complexes are of high molecular weights (Supplemental Figure S1A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764), suggesting the presence of additional proteins in this complex. We next examined whether the ZBTB3-SRCAP complex binds to the CEGRs/ALCDs. A biotinylated oligomer containing the ZBTB3 binding region from CEGRs/ALCDs was bound to streptavidin beads and incubated with protein extracts from ZBTB3-positive HBL samples. We found a strong interaction of ZBTB3 and SRCAP with the ZBTB3 binding site in the CEGR/ALCD (Figure 1D, pull down). This interaction is specific since β-actin was not detected in the pull-down samples under 1 minute of exposure. We found that identical traces of β-actin can be detected in all pull-down samples only after very long exposure. The identical signals of β-actin showed equal addition of the proteins to the pull-down samples. ChIP assays uncovered that the ZBTB3-SRCAP complex binds to CEGRs/ALCDs in both tumor samples and HepG2 cells (Figure 1D, right). Histone H3K acetylation at K9 shows that the binding of these complexes opens DNA regions in CEGRs/ALCDs in several oncogenes.

FIGURE 1.

Transcription factor ZBTB3 is increased in intrahepatic nerve fibers of livers in patients with HBL. (A) Left: Results of RELI algorithm showing that ZBTB3 binds to CEGRs/ALCDs. The location and sequence of the ZBTB3 binding site within the CEGRs/ALCDs are shown. Right: Levels of ZBTB3, SRCAP, ZBTB4, and ZBTB38 mRNAs were examined in a fresh biorepository of HBL samples (values presented as means±SEM). (B) ZBTB3 and SRCAP protein levels were determined by western blotting. Background (Back) is a section of the normal liver adjacent to the tumor. Hepatoblastoma is a tumor section of the liver. The western blot was performed with backgrounds of 6 patients and with tumor sections of 9 patients with HBL patients. Student t tests were utilized to compare ratios of signals of ZBTB3 (p=0.0009) and SRCAP (p=0.0006) proteins to signals of β-actin (right images). (C) Co-IP studies of ZBTB3 from the background of 3 patients and tumor sections of 4 patients with HBL, as well as from HepG2 cells (labeled G2 on image). Top: Western blot shows the input of the proteins. Ratios of signals of ZBTB3 and SRCAP proteins to signals of β-actin are shown below each western blot image. (D) Left: Pull-down assay with 18BP oligomer from CEGRs/ALCDs containing a binding site for ZBTB3. (B: Background, T: Tumor). Right: ChIP assay with CEGRs/ALCDs of CTNNB1, NFE2L2, and PGAP1 genes using chromatin solutions from HepG2 cells and from patients with HBL. (E) β-III-tubulin staining in background and tumor sections of HBL. (F) Costaining of a large region of HBL with DAPI, β-III tubulin, and ZBTB3. Scale bar=50 μM. Arrows show colocalizations of signals around the bile duct. Circles show colocalizations far away from the bile duct. Abbreviations: CEGRs/ALCDs, cancer-enhancing genome regions/aggressive liver cancer domains; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; Co-IP, coimmunoprecipitation; HBL, hepatoblastoma; PV-IHBD, portal vein-intrahepatic bile duct area.

ZBTB3 is expressed in the expanded β-III-tubulin–positive intrahepatic nerve fibers of patients with HBL

Although ZBTB proteins are significant transcriptional regulators in several tissues including neuronal cells,19,20 little is known about ZBTB3 expression in the liver. Analysis of mouse intestine shows ZBTB3 expression is detectable in the same regions as β-III-tubulin and NGF, indicating ZBTB3 is expressed in neurons of the digestive system (Supplemental Figure S1B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). It has been previously found that β-III tubulin is detectable in the intrahepatic nerve network in bile duct regions.12,13 Therefore, we examined if ZBTB3 is expressed in intrahepatic nerve fibers (Figure 1E). In the background sections, the ZBTB3 staining is observed only in nerve fibers around the portal vein-intrahepatic bile duct (PV-IHBD) areas. However, in tumor sections, ZBTB3-positive cells/fibers were observed not only around PV-IHBD but also in areas distant from the PV-IHBD (Figure 1E). The staining of a parallel slide with antibodies to β-III-tubulin showed that ZTBT3 signals and β-III-tubulin signals are located in the same areas. Studies in additional patients with HBL with antibodies to β-III-tubulin and NeuN revealed similar results (Supplemental Figures S1C–F, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Costaining with antibodies to ZBTB3 and β-III-tubulin showed almost complete colocalization of these proteins (Figure 1F). We next analyzed RNA-Seq data in a large, previously characterized biorepository of HBL samples7 for the levels of markers of hepatic nerve cells: TUBB3 (coding for β-III-tubulin), NGFRAP1 (nerve growth factor receptor–associated protein), and ZBTB4. The previous BioBank contained over 62 specimens; and we found that the TUBB3, NGFRAP1, and ZBTB4 RNAs were increased in tumors by 3.13-, 4.8-, and 3.16-fold of these patients with HBL, respectively. Taken together, we conclude that the expression of neuronal markers is increased in tumors of patients with HBL.

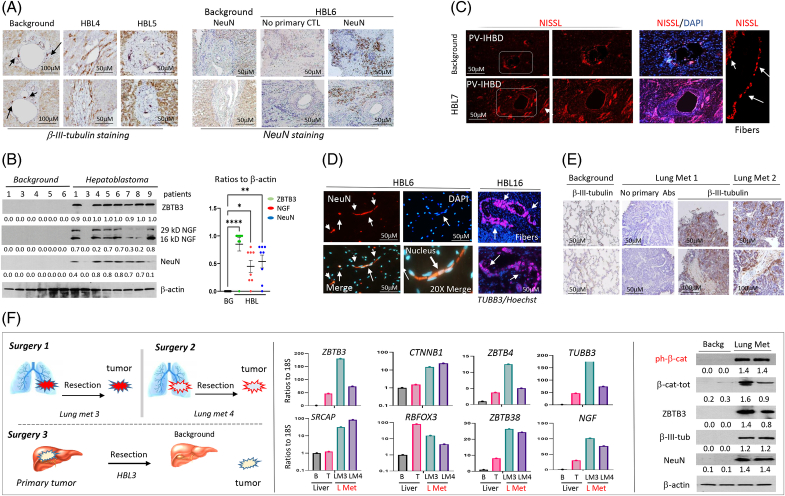

Markers of neurons β-III-tubulin, NeuN, and NGF are highly expressed, and neuron-like cells are abundant in liver tumors of patients with HBL with lung metastases

Given the increase of intrahepatic nerve fibers throughout tumor sections of the livers, we examined the expression of 3 neuronal markers. β-III-tubulin immunostaining of PV-IHBD regions of tumors revealed disordered structures in the PV-IHBD area (Figure 2A). NGF was found to be highly elevated in tumor sections compared to background sections of the same patients with HBL, and NGF, β-III-tubulin, and ZBTB3 signals overlap (Supplemental Figures S2A, B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Staining of primary tumors with NeuN showed a dramatic increase of NeuN-positive cells/fibers in the tumor, but not in background regions (Figure 2A, right). Western blotting revealed significant levels of ZBTB3, NGF, and NeuN in HBL tumors (Figure 2B). To further confirm the presence of neuron-like cells, we performed Nissl staining which identifies the Nissl bodies of neurons.21 Nissl-positive fibers and cells are located mainly in the PV-IHBD area in background regions. However, in tumor sections, Nissl-positive signals appear in both PV-IHBD regions and are distant from them (Figure 2C). HBL tumors also contain Nissl-positive fibers (Figure 2C and Supplemental Figure S2C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Interestingly, a portion of patients with HBL have NeuN-positive cells that resemble the shape of bipolar neurons and TUBB3-positive fibers (Figure 2D). Thus, we conclude that primary tumors of patients with HBL with lung metastases have expanded neuronal marker–positive cells/fibers.

FIGURE 2.

Neuronal markers and neuron-like cells are elevated in primary tumors and lung metastases of patients with HBL. (A) Left: Immunostaining of background and tumor regions of HBL to β-III tubulin. Arrows show positive signals around bile ducts. Right: Immunostaining of HBL samples to NeuN. Scale bar=50 μM. (B) Western blotting with antibodies to ZBTB3, NGF, and NeuN shows the elevation of these proteins in aggressive HBL. A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the ratios of these proteins to signals of β-actin. ZBTB3 (p<0.0001), NGF (p=0.0230), and NeuN (p=0.0062). Two isoforms of NGF were used for calculations. The western blot was performed with backgrounds of 6 patients and with tumor sections of 9 patients with HBL. Right: results of statistical analysis. (C) Nissl staining of background and tumor sections from a patient. Far right: detection of Nissl-positive fibers. (D) Neuron-like cells/fibers are observed in primary liver tumors of patients with HBL. Left: NeuN staining of patient HBL6. Right: TUBB3-positive fibers observed in patient HBL16. (E) Lung metastases of patients with HBL show intensive staining with β-III-tubulin, compared to a No Primary Control slide of the same patient. (F) Left: A diagram showing the order of surgeries for patient #62. Middle: Levels of mRNAs for ZBTB3, SRCAP, CTNNB1, NeuN, and other neuronal markers in the original tumor and lung metastases of patient LM3. Right: ZBTB3, β-III-tubulin, NeuN, total β-catenin, and ph-S675-β-catenin protein levels were determined within lung metastases of patients with HBL by western blot. Ratios of signals of these proteins to signals of β-actin are shown below each western blot image. Abbreviations: BG, background; CTL, control; HBL, hepatoblastoma; NGF, nerve growth factor; PV-IHBD, portal vein-intrahepatic bile duct area.

Lung metastases of patients with HBL contain cells positive for neuronal markers

We next analyzed lung metastases from patients with HBL for cells expressing neuronal markers. Immunostaining with β-III-tubulin in patients revealed a strong signal in the lung metastasis sample, but no positive signals in background regions, and no signals in a “no primary Abs” slide (Figure 2E). To investigate lung metastases in-depth, we analyzed samples from a patient who underwent resections for a primary liver tumor and 2 lung metastases (Figure 2F, left). qRT-PCR analysis showed that neuronal markers are elevated in the primary liver tumor, and further elevated in the lung metastases (Figure 2F, bar graphs). These data were obtained with 1 patient with HBL who had 2 repetitive lung metastases. Further studies with a bigger number of patients are needed to understand if the higher increase of markers of neurons in lung metastases is a common feature of repetitive lung metastases. Because our group previously found that β-catenin phosphorylation at Ser675 was elevated in patients with HBL,11 we examined the expression of ph-S675-β-catenin in HBL lung metastases. Western blot showed that ph-S675-β-catenin and total β-catenin were elevated in lung metastases (Figure 2F, right). Protein levels of ZBTB3, β-III-tubulin, and NeuN were also increased in lung metastases.

Generation of cell lines derived from patients HBL with with potential metastatic activities

To examine the mechanisms by which HBL tumors release metastatic cells into the bloodstream, we established a cell extraction protocol that is based on the “free exit” of cells from a liver tumor in media (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure S3, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Within 1–4 weeks, cells began to exit the tumor into the culture media and attach to the plate, while background sections did not release cells (Figure 3B). Figure 3C shows a large area of the plate with exiting clusters and cells (left) and images of tumor clusters that were exiting the tumor at 1 week after plating (right). We refer to the released cells as hbl cells to distinguish them from tissue tumors (referred to as “HBL”). Cells released by lung metastases are referred to as LM cells. Exiting clusters are referred to as tumor clusters. Examination of the growth of these cells showed several specific characteristics. Plating patient cell lines at low density demonstrated that hbl cells not only actively proliferate but also travel toward and interact with each other (Figure 3D). In some cases, we observed the formation of a “net” where all cells on the field interacted with each other. At days 10–12 after plating, hbl cells formed cell clusters, which we refer to as tumor clusters (Figure 3E). Similar patterns of interaction and tumor cluster formation were observed in all examined hbl cell lines (n=16) (Figure 3F, Supplemental Figures S3C, D, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Thus, the cell lines released from the primary liver tumors have a high rate of proliferation and form intensive cell-cell interactions, leading to the development of tumor clusters.

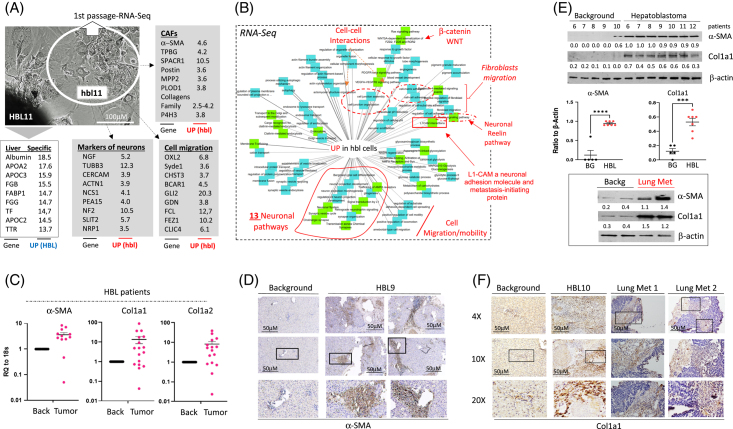

RNA-Seq analysis showed that hbl cells have abundant neuronal pathways, enrichment of CAFs, and elevation of pathways that promote high migration/mobility of cells

To determine the transcriptomic profile of hbl cells, RNA-Seq analysis comparing the original HBL tumor to hbl cells was performed (Figure 4A). RNA-Seq identified the elevation of 13 neuronal pathways, pathways that are involved in the development of CAFs, cell-cell interactions, and cell mobility (Figure 4B). β-catenin/WNT signaling was also elevated in hbl cells. The deep analysis of RNA-Seq identified additional neuron-specific mRNAs that are increased in hbl cells: L1 cell adhesion molecule and Reelin. L1 cell adhesion molecule is a neuronal adhesion molecule that is expressed in many tumors.22 It has been found that L1 cell adhesion molecule defines the origin of metastasis-initiating cells in colorectal cancer.23 Regarding Reelin, it has been shown that Reelin plays a key role in the development of the central nervous system,24 suggesting that its elevation in hbl cells reflects the enrichment of neuron-like cells. Interestingly, all liver/hepatocyte-specific markers such as Albumin, Transferrin, APOA2, APOC2, APOC3, FGG, and TRR had the highest expression in the original tumor (Figure 4A, open box). Gray boxes in Figure 4 show the elevation of neuronal markers, CAFs, and cell migration markers. Thus, RNA-Seq analysis showed that cells released by patients’ original liver tumors are enriched in neuronal pathways, cell migration pathways, and CAF development pathways.

FIGURE 4.

Transcriptome profile of hbl cell detected by RNA-Seq assay. (A) An image of the HBL and exiting hbl cells that were used for RNA-Seq. The unshaded box shows mRNAs increased in HBL cells. Gray-shaded boxes show mRNAs that are elevated in hbl cell lines. (B) Ontology map of mRNAs elevated in hbl cells. The increase of neuronal pathways, L1-CAM, Reelin, CAFs, and cell migration pathways are shown in red. (C) Levels of mRNAs of CAFs markers α-SMA, Col1a1, and Col1a2 in HBL patient biobank (N=17) (values presented as means±SEM). (D) Staining of primary HBL for α-SMA. (E) Top: Protein levels of α-SMA and Col1a1 are increased in primary tumors of patients with HBL. The western blot was performed with backgrounds of 4 patients and with tumor sections of 9 patients with HBL. Student t tests were used to compare ratios of marker signals to signals of β-actin (graphs below). α-SMA (p<0.0001) and Col1a1 (p=0.0002). Bottom: Protein levels of markers of CAFs are increased in the lung metastasis of a patient with HBL. Supplemental Figure S5A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764 shows statistical analysis of these results. (F) Staining of primary HBL tumor and lung metastases with Col1a1. Scale bars=50 μM. Abbreviations: BG, xxx; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; HBL, hepatoblastoma; L1-CAM, L1 cell adhesion molecule

CAFs are abundant in original liver tumors of patients with HBL and lung metastases

While the release of neuron-like cells by HBL tumors is consistent with the extension of intrahepatic nerve fibers and neuron-like cells in patients with HBL, the release of cells with an increase in CAF-specific pathways was surprising. Therefore, we examined whether ph-S675-β-catenin regulates CAF markers and whether CAFs are present in primary tumors. First, CEGRs/ALCDs were found in the introns of genes encoding for α-SMA, Col1A1, and Col1A2, as well as binding sites for β-catenin-TCF4 in their promoters (Supplemental Figure S4, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). qRT-PCR examination of an HBL biorepository (N=32) revealed a significant increase in mRNAs coding for α-SMA, Col1A1, and Col1A2 (Figure 4C). Immunohistochemistry of primary HBL tumors with α-SMA revealed strong staining in tumor sections compared to background regions (Figure 4D). Western blot confirmed significant levels of α-SMA and Col1A1 proteins in tumors, as well as elevated levels in lung metastases samples from patients with HBL (Figures 4E, F and Supplemental Figure S5A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Elevation of α-SMA, Col1a1, and Col1A2 mRNAs was also found in these lung metastases (Supplemental Figure S5B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764).

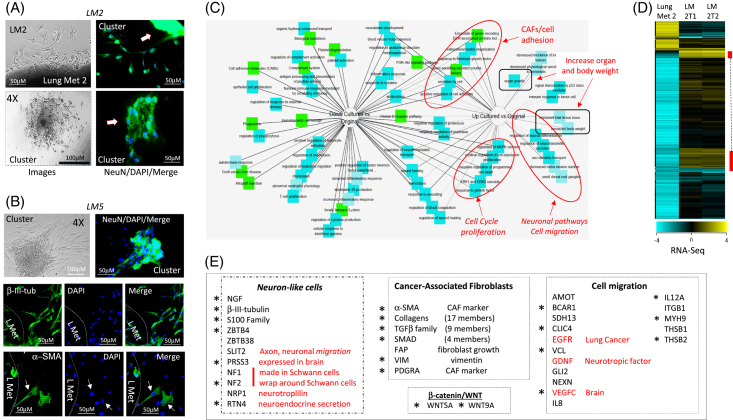

Cell lines released by lung metastases of patients with HBL developed tumor clusters positive for neuronal markers and markers of CAFs

Using the cell-free-exit protocol, we generated 2 sublines from a single metastasis from a patient who had previously undergone resections for a primary liver tumor and 4 other metastases (LM2-1 and LM2-2). A third lung metastasis cell line, LM5, was developed from a patient who, at the time of writing this manuscript, had developed a singular lung metastasis after the removal of the primary HBL tumor. Figures 5A, B show the examination of LM2 and LM5 at various stages of exit and in early passages in cell culture. We found that the efficiency of cell exit from lung metastases of patients with HBL was substantially higher and faster than that from primary liver tumors. The metastases-released cells formed tumor clusters within 1 week after cell exit and in the early passages (passages #1–2). We also noted that LM2 cell lines showed efficient formation of unusually long clusters than LM5 cells (Supplemental Figure S6, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Immunofluorescent staining of LM2 and LM5 cells identified cells positive for NeuN, β-III-tubulin, and α-SMA, suggesting that neuron-like cells and CAFs are present in lung metastases (Figures 5A, B).

FIGURE 5.

Characterization of microenvironment obtained by cell-free-exit protocol from lung metastases (LM2 and LM5). (A) Left images show exiting cells and clusters forming by cells from Lung Met 2 on the plate at the time of extraction. Right images show staining of exiting cells with NeuN. (B) A second lung metastasis (Lung Met #5) secretes NeuN-positive cells and β-III-tubulin and α-SMA–positive cells, which form clusters on the plate. (C) The ontology and signaling pathways determined by the RNA-Seq approach. (D) Heat map of RNA-Seq results with original Lung Met 2 tumor and 2 sublines of secreted cells: LM2-1 and LM2-2. Yellow clusters show genes that are highly abundant. (E) Transcriptome signature of cells secreted by lung metastases. Asterisks mark mRNAs that are identically elevated in exiting LM2 and LM5 cell lines compared to original lung metastases. Scale bars=50 μM.

RNA-Seq analysis was performed to compare the LM cell lines to the original metastases samples. Like RNA-Seq of hbl cells, pathways related to neurons, CAFs, cell migration, cell proliferation, and cancer are highly expressed in the LM2 cell line, compared to the original tumor (Figure 5C). A heat map of RNA-Seq data showed 2 main clusters with high gene expression in LM2 and LM5 cells relative to original lung metastasis tissues from the same patients (Figure 5D). Examination of pathways/genes within these 2 clusters identified markers of neuronal cells (15 genes) and CAFs (37 genes) as being upregulated (Figure 5E). In addition, a group of genes (16 genes) that promote cell migration were elevated in LM2 cells (Figure 5E). RNA-Seq analysis also revealed an elevation of genes encoding stem cell markers (Thy1 and KLF4), cell cycle proteins (CDKs), transcription factors (TCF4/TCF7L2, RUNX1, FOXM1, and FOXL1), members of the WNT family (WNT5A, WNT5B, and WNT9A), and members of the Sonic Hedgehog pathway (GLI2 and HHIP) (Supplemental Figure S7A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). It is interesting to note that the comparison of RNA-Seq data for the LM5 line, generated from the patient’s first lung metastasis, with data from the LM2 line—derived from the patient’s fifth lung metastasis—LM2 was found to have elevated levels of additional genes and pathways. Those include neuronal markers ZBTB38, NF1, FAP, and FLTR2 and CAF markers, ASPN, STC1, and KLF4 (Supplemental Figure S7B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). We also found the elevation of a larger set of genes involved in cell migration and cell cycle progression in LM2 (Supplemental Figure S7B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). These differences show a higher aggressiveness of cells from the fifth metastasis (compared to the first lung metastasis) and suggest that the repetitive development of lung metastases is the result of overexpression of a bigger number of neuronal markers and CAFs-associated genes.

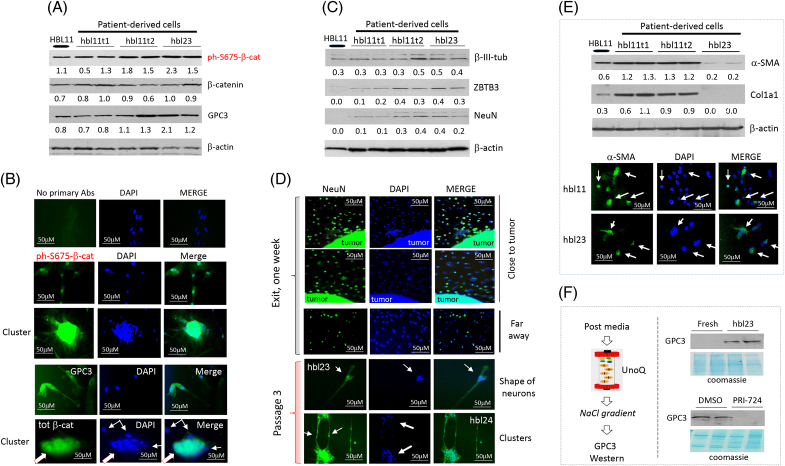

Hbl microenvironments preserve active ph-S675-β-catenin-CEGRs/ALCDs pathway and contain neuron-like cells and CAFs

Our previous work found that the ph-S675-β-catenin-CEGRs/ALCDs pathway is active in aggressive HBL, causing overexpression of a marker of HBL, GPC3.11 Therefore, we examined if the ph-S675-β-catenin-GPC3 pathway is preserved in hbl cells. We found that β-catenin, ph-S675-β-catenin, and GPC3 are highly expressed in hbl23 and hbl11t1/2 cells (Figure 6A and Supplemental Figure S8A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Immunostaining revealed high expression levels of ph-S675-β-catenin, total β-catenin, and GPC3 in tumor clusters formed from hbl cell lines (Figure 6B). Since RNA-Seq results suggested that established hbl cell lines contain cells positive for neuronal markers, we examined the presence of neuron-like cells using early passages of hbl cell lines. Western blotting with antibodies to β-III-tubulin, NeuN, and ZBTB3 showed that these proteins are expressed in generated hbl cell lines (Figure 6C and Supplemental Figure S8B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). We next asked if NeuN-positive cells are directly released from the tumor, or if they are the result of the dedifferentiation of cancer stem cells into NeuN-positive cells. For this goal, a fresh cut of the HBL12 tumor was placed on a slide, and exiting cells were stained for NeuN. As shown in Figure 6D, about 50% of tumor-exiting cells close to the plated tumor are NeuN-positive. Around 45%–50% of NeuN-positive cells were found a long distance from the attached tissue. These studies revealed that, at the time of release, the exiting cells are neuron-like cells. NeuN staining of exiting cells from another patient with HBL (HBL19) is shown in Supplemental Figure S9A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764. We have found that several hbl lines have further accumulated cells with neuronal shapes (Supplemental Figure S10A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). In the hbl11 cell line, we also detected the formation of a huge neuron-like cell body which was positive for NeuN (Supplemental Figures S10B, C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Further studies confirmed the presence of NeuN-positive cells in hbl cell lines and showed that these cells are shaped like neurons (Figure 6D). We also found that tumor clusters of hbl cells are positive for NeuN staining and that NeuN-positive tumor clusters are connected to each other through long cell extensions, indicating that NeuN-positive cells might promote the formation of tumor clusters. We next examined if the cells exiting from HBL tumors are CAFs using antibodies to markers of CAFs, α-SMA and Col1a1. Western blotting found that hbl11t1 and hbl11t2 highly express α-SMA and Col1a1. Immunostaining of cell lines hbl11t1/t2 and hbl23 showed that 30%–50% of cells were positive for α-SMA (Figure 6E and Supplemental Figure S8C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). These markers are expressed in other generated hbl cell lines (data not shown). We also performed staining of exiting cells with hepatocyte markers, C/EBPα and HNF4α, and did not detect cells that were positive for these markers (Supplemental Figure S11, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764), suggesting that the exiting cells are not dedifferentiated from hepatocytes. Taken together, we conclude that hbl cells have active ph-S675-β-catenin-GPC3 signaling and contain both CAFs and neuron-like cells.

FIGURE 6.

HBL-released cells express elevated levels of ph-S675-β-catenin and contain neuron-like cells and CAFs. (A) Western blots showing levels of ph-S675-β-catenin, total β-catenin, and GPC3 in a primary HBL tumor and 3 hbl cell lines. Supplemental Figure S8A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764 shows statistical analysis of these results. (B) Immunostaining of hbl cells for ph-S675-β-catenin, GPC3, and total β-catenin. (C) Western blots showing levels of β-III-tubulin, ZBTB3, and NeuN in a primary HBL tumor and 3 hbl cell lines. Supplemental Figure S8B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764 shows statistical analysis of these results. (D) Immunostaining of hbl cell lines for NeuN. The top 3 panels show NeuN staining of the cells at very early stages of exit. Areas close to the attached tumor and areas in the distance are shown. (E) Top: Western blots show levels of α-SMA and Col1a1 in a primary HBL tumor and 3 hbl cell lines. Bottom: immunostaining of 2 hbl cell lines for α-SMA. Supplemental Figure S8C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764 shows statistical analysis of these results. (F) hbl cells secrete GPC3 in culture media. Left: a strategy for concentrating postculture media using a UnoQ ion exchange column. Right: examination of GPC3 protein levels by western blot. For each western Blot, the ratios of proteins to β-actin are shown below the western blot images. Scale bars=50–100 μM. Abbreviations: CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; HBL, hepatoblastoma.

The previous study showed that GPC3 is detected in the blood of patients with HBL who had active ph-S675-β-catenin in primary tumors11; therefore, we examined if the generated ph-S675-β-catenin–positive hbl cells might secrete GPC3 into the media. Proteins in the hbl-conditioned media were concentrated by loading on ion exchange column UnoQ and by subsequent elution by a sharp gradient of NaCl (Figure 6F and Supplemental Figure S10D, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). We found that GPC3 is detected in the hbl23 conditioned media, while fresh media does not have detectable GPC3 (Figure 6F). We next asked if β-catenin inhibition by PRI-72425 might block GPC3 secretion. We found that hbl cells treated with PRI-724 have reduced GPC3 secretion into the media, compared to DMSO-treated controls (Figure 6F). Thus, these studies showed that hbl cells do secrete GPC3 into the media, and the inhibition of β-catenin blocks this secretion.

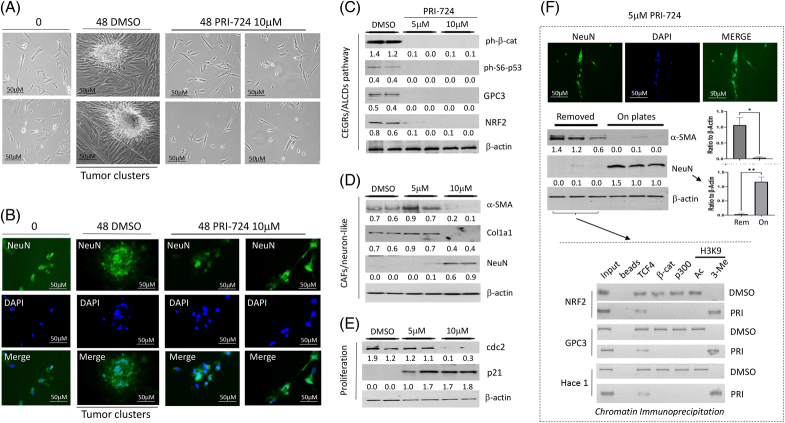

Inhibition of the β-catenin-CEGRs/ALCDs axis in HBL microenvironment blocks the formation of tumor clusters

Since the β-catenin-TCF4-CEGRs/ALCDs pathway is active in hbl cell lines, we wanted to see if inhibiting this pathway could suppress their proliferation and their ability to form tumor clusters. We found that DMSO-treated cells formed large tumor clusters, while PRI-724–treated cells did not form clusters (Figure 7A). PRI-724 also inhibited tumor cluster formation in other patient cell lines (Supplemental Figure S9B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). Immunostaining revealed that in DMSO-treated cells, NeuN-positive cells were observed in the center of tumor clusters; however, the inhibition of β-catenin blocked the development of NeuN-positive tumor clusters (Figure 7B). Note that tumor cluster cells treated with DMSO for 48 hours have a smaller size due to a short incubation in the culture. To ascertain whether PRI-724 prevents tumor cluster formation in patient cell lines through the β-catenin CEGRs/ALCDs axis, protein expression of the axis components was analyzed by treating patient cells with 2 doses of PRI-724. Both doses of PRI-724 strongly inhibited the ph-S6-p53 and ph-S675-β-catenin-TCF4 pathways, which are known to activate CEGRs/ALCDs in aggressive HBL.9,10,11 The downstream targets of these pathways, GPC3 and NRF2, were also reduced (Figure 7C and Supplemental Figure S12A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). A high dose of PRI-724 reduced α-SMA and Col1a1 in hbl cells, suggesting that PRI-724 suppresses the proliferation of CAFs. NeuN was increased in the PRI-724–treated patient cells (Figure 7D and Supplemental Figure S12B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764), suggesting that neuron-like cells are less sensitive to PRI-724. Examination of cdc2 and p21 in the treated hbl cells showed that the proliferation of remaining NeuN-positive hbl cells is reduced by a high dose of PRI-724 (Figure 7E and Supplemental Figure S12C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764).

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of ph-S675-β-catenin-CEGRs/ALCDs pathway blocks the formation of tumor clusters in hbl microenvironment. (A) PRI-724 inhibits the formation of tumor clusters in hbl microenvironment. Bright-field images are shown. (B) Immunostaining of DMSO and PRI-724–treated hbl cells for NeuN. (C) Western blot analyses of ph-S675-β-catenin-CEGRs/ALCDs pathway. Statistical analysis is shown in Supplemental Figure S12A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764. (D, E) Western blotting of CAFs, neuron-like cells, and cell proliferation markers in DMSO and PRI-724–treated hbl74 cells. Ratios of proteins to β-actin are shown below for each western blot image. The statistical analysis is shown in Supplemental Figures S12B, C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764. (F) Separation of CAFs from neuron-like cells for ChIP assay. The bottom image shows a ChIP assay with enriched CAFs from DMSO and PRI-724–treated cells. Scale bars=50 μM. Abbreviations: CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; CEGRs/ALCDs, cancer-enhancing genome regions/aggressive liver cancer domains; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Results in Figures 7C–E suggested that the inhibition of CAFs in hbl cells may occur through a suppression of CEGRs/ALCDs regions in oncogenes. To determine the effect of PRI-724 on the CEGRs/ALCDs regions in oncogenes, we separated CAFs and NeuN-positive cells by a mild trypsinization. CAFs are easily deattached from the plate, while NeuN-positive cells remain tightly connected to the plate (Figure 7F). The collected hbl CAFs-enriched cells treated with DMSO or with PRI-724 were used for ChIP assays for 3 oncogenes (NRF2, GPC3, and HACE1) which are the targets of ph-S675-β-catenin.10,11 This analysis showed that β-catenin-TCF4-p300 complexes are bound to the CEGRs/ALCDs in DMSO-treated CAFs; however, only TCF4 was found on these DNA regions in the PRI-724–treated hbl69 cells (Figure 7F, ChIP).

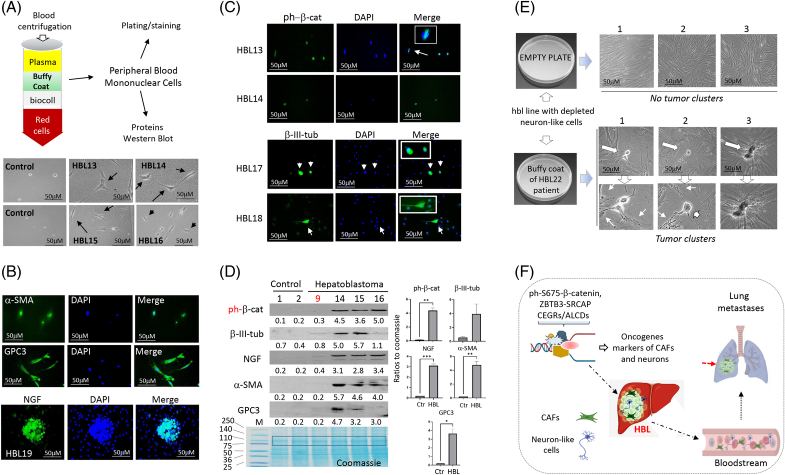

Blood samples of patients with HBL contain ph-S675-β-catenin–positive cells, neuron-like cells, and CAFs

To determine if neuron-like cells and CAFs might be detected in the bloodstream of patients with HBL, we analyzed blood samples from 10 patients with HBL with lung metastases or relapses. The whole-blood samples were separated using centrifugation with biocoll and the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)/buffy coat layer was collected (Figure 8A). Buffy coats were plated on a collagen plate for bright-field microscopy or on the collagen-coated slides for immunostaining. A comparison of the bright-field microscopy images of buffy coats plated from healthy patients and patients with HBL showed attached PBMCs in control blood samples; however, buffy coats from the blood of patients with HBL contained PBMCs and elongated cells (Figure 8A). Immunostaining identified cells positive for α-SMA and GPC3 in the blood samples from patients with HBL (Figure 8B). Buffy coats from these patients also contained cells that are positive for ph-S675-β-catenin and β-III-tubulin (Figure 8C). In one rare case, buffy coat cells were able to proliferate and formed clusters of NGF-positive cells (Figure 8B). Western blotting confirmed that buffy coats from the blood of patients with HBL contain cells positive for ph-S675-β-catenin, α-SMA, β-III-tubulin, NGF, and GPC3 (Figure 8D). It is interesting that patient (#9) with HBL had the primary liver tumor resected in surgery and was successfully treated with chemotherapy. No lung metastases were observed in this patient. In agreement with this, our studies of this patient’s blood showed that CAFs and neuron-like cells are not detected in the bloodstream.

FIGURE 8.

Bloodstream of patients with HBL with active β-catenin-TCF4-CEGRs/ALCDs pathways contains ph-S675-β-catenin–positive cells, neuron-like cells, and CAFs. (A) Top: A design for analyses of cells in buffy coat fraction of whole blood. Bottom: Images of cells in a buffy coat of control blood from 2 healthy patients and 4 patients with HBL. (B) Immunostaining of buffy coats of patients with HBL for α-SMA, GPC3, and NGF. (C) Immunostaining of buffy coat cells to ph-S675-β-catenin and for β-III-tubulin. (D) Western blot analysis of proteins isolated from buffy coats of blood of patients with HBL. Student t tests were used to compare ratios of protein signals to a portion of Coomassie stain (marked by box). ph-β-catenin (p=0.0041), β-III-Tubulin (no significance), NGF (p=0.0010), α-SMA (p=0.0057), and GPC3 (p=0.0158). The bottom image shows the loading and integrity of isolated proteins (coomassie). (E) Cells from buffy coats of patients with HBL restore the ability of the neuron-like cells depleted hbl line to form tumor clusters. (F) A hypothesis for the first lung metastases and repetitive lung metastases in patients with HBL with aggressive liver cancer. Scale bars=50 μM. Abbreviations: CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; CEGRs/ALCDs, cancer-enhancing genome regions/aggressive liver cancer domains; HBL, hepatoblastoma; NGF, nerve growth factor.

Since it was not possible to establish cell lines from buffy coats of patients with HBL, we examined if coculturing PBMC from the blood of patients with HBL with hbl cell line that lost the ability to form tumor clusters might restore tumor cluster formation. For this goal, hbl cell line with depleted neuron-like cells was generated by a short time of cell plating when neuron-like cells are not attached to the plate, while other cells (mainly CAFs) are attached (Supplemental Figure S13, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A764). The hbl cell line with depleted neuron-like cells was added to the plate with PBMC of the patient with HBL. We found that this coculturing restores the tumor cluster formation in hbl cell line which lost the ability to form tumor clusters (Figure 8E) showing that the neuron-like cells released in the blood are the initiators of the formation of tumor clusters. Taking together our data, we hypothesize that CAFs and neuron-like cells are the origin of lung metastases (Figure 8F).

DISCUSSION

The development of lung metastases in patients with HBL is the primary indicator of the cancer’s aggressiveness. The cellular origin of lung metastases, as well as the underlying molecular mechanisms causing lung metastases in HBL, have not been elucidated. Our findings reveal that neuron-like cells and CAFs are key cells in the HBL microenvironment and are elevated in primary liver tumors. Previous studies have found neuronal markers and neuronal-like cells in HCC liver tumors,26,27 implying some mechanistic similarities between pediatric and adult liver cancer. It has been demonstrated that neuron-derived orphan receptor (NOR-1/NR4A3) promotes hepatocyte proliferation.28 Overexpression of neuron-glial antigen 2 (NG2) is observed in patients with HCC and may be a predictor of poor prognosis.29 CAFs are found in the cellular HBL microenvironment alongside neuron-like cells. Neuron-like cells and CAFs interact extensively in tissue culture cell lines, forming tumor clusters. From a mechanistic standpoint, we found that the ZBTB3-CEGRs/ALCDs axis is critical for neuron-like cell expansion and proliferation, whereas the ph-S675-β-catenin/TCF4-CEGRs/ALCDs pathway is involved in CAF expansion. We discovered that hbl cells develop quickly and represent a more aggressive component of HBL tumors, thereby serving as a model of real-time therapeutic drug testing in vitro with the potential to impact personalized medical care for patients. Related to such translational potential, data presented demonstrated the antitumor effects of PRI-724 targeting β-catenin in aggressive HBL metastasis-producing cells. Since the majority of HBL harbor β-catenin mutations, the inhibition of β-catenin–driven pathophysiology in HBL may be beneficial for children with chemo-resistant HBL. The Children’s Oncology Group is currently conducting a phase 1/2 study of tegavivint, a β-catenin inhibitor, in children with HBL (NCT04851119).

Another key finding of this study was the identification of CAFs and neuron-like cells in primary liver tumors, lung metastases, the HBL microenvironment and lung metastases in vitro, and blood samples from patients. Based on this knowledge, we hypothesize that the CAFs and neuron-like cells’ release into the bloodstream, followed by the cells’ subsequent attachment to the lung, is the cause of the initial development of metastases in patients with HBL (Figure 8F). Since we found that CAFs and neuron-like cells are observed in a patient after the primary tumor was removed, we suggest that lung metastases continued to release CAFs and neuron-like cells into the bloodstream, leading to a high risk of recurrence of lung metastases and liver relapse.

Supplementary Material

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ruhi Gulati generated the design, performed experiments with HBL specimens, analyzed data, and participated in writing the manuscript. Maggie Lutz was involved in the investigations of the cells from patients with HBL and the discussion of data for the manuscript. Margaret Hanlon analyzed gene expression in our biorepository and participated in writing the manuscript. Ashley Cast performed immunostaining of the samples from the archived HBL biorepository. Rebekah Karns has performed biostatistical analyses of RNA-Seq data and participated in the preparation of the manuscript. James Gelle, Gregory Tiao, and Alex Bondoc participated in the surgeries, collection of specimens, and the generation of design for cell treatments and in the interpretation of results. Lubov Timchenko has generated the design for HBL cell propagation and participated in the treatments and analyses of cell lines from patients with HBL. Nikolai A. Timchenko has generated the overall design for the project, and performed a portion of molecular studies of patients with HBL, lung metastases, and metastatic cells. He has written the manuscript and obtained funds for the studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank NIH P30 DK078392 of the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center in Cincinnati for supporting these studies.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The work was supported by internal funds from the Division of Pediatric Surgery, CCHMC, and by funds from the Grace Foundation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; CEGRs/ALCDs, cancer-enhancing genomic regions or aggressive liver cancer domains; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; HBL, hepatoblastoma; NGF, nerve growth factor; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PV-IHBD, portal vein-intrahepatic bile duct; qRT-PCR, Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR; RELI, Regulatory Element Locus Intersection.

Ruhi Gulati, Maggie Lutz, and Margaret Hanlon contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.hepcommjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Ruhi Gulati, Email: Ruhi.Gulati@cchmc.org.

Maggie Lutz, Email: Maggie.Lutz@cchmc.org.

Margaret Hanlon, Email: Margaret.Hanlon@cchmc.org.

Ashley Cast, Email: Ashley.Cast@cchmc.org.

Rebekah Karns, Email: Rebekah.Karns@cchmc.org.

James Geller, Email: james.geller@cchmc.org.

Alex Bondoc, Email: Alex.Bondoc@cchmc.org.

Gregory Tiao, Email: greg.tiao@cchmc.org.

Lubov Timchenko, Email: Lubov.Timchenko@cchmc.org.

Nikolai A. Timchenko, Email: Nikolai.Timchenko@cchmc.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. O’Neill AF, Towbin AJ, Krailo MD, Xia C, Gao Y, McCarville MB, et al. Characterization of pulmonary metastases in children with hepatoblastoma treated on children’s oncology group protocol AHEP0731 (the treatment of children with all stages of hepatoblastoma): A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3465–3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shi Y, Geller JI, Ma IT, Chavan RS, Masand PM, Towbin AJ, et al. Relapsed hepatoblastoma confined to the lung is effectively treated with pulmonary mastectomy. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hu H, Zhang W, Zhi T, Li J, Wen Y, Towbin AJ. Genotypic characteristics of hepatoblastoma as detected by next generation sequencing and their correlation with clinical efficacy. Front Oncol. 2021;11:628531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 4. Zhang YT, Chang J, Yao YM, Li YN, Zhong XD, Liu ZL. Novel treatment of refractory/recurrent pulmonary hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Int. 2020;62:324–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Affo S, Nair A, Brundu F, Ravichandra A, Bhattacharjee S, Matsuda M, et al. Promotion of cholangiocarcinoma growth by diverse cancer-associated fibroblast subpopulations. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:866–882.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cairo S, Armengol C, De Reyniès A, Wei Y, Thomas E, Renard CA, et al. Hepatic stem-like phenotype and interplay of Wnt/beta-catenin and Myc signaling in aggressive childhood liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:471–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valanejad L, Cast A, Wright M, Bissig KM, Karns R, Weirauch MT, et al. PARP1 activation increases expression of modified tumor suppressors and pathways underlying development of aggressive hepatoblastoma. Commun Biol. 2018;1:1–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rivas M, Johnston ME, II, Gulati R, Kumbaji M, Margues Aguiar TF, Timchenko T, et al. HDAC1-dependent repression of markers of hepatocytes and P21 is involved in development of pediatric liver cancer. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12:1669–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnston ME, II, Rivas MP, Nicolle D, Gorse A, Gulati R, Kumbaji M, et al. Olaparib inhibits tumor growth of hepatoblastoma in patient derived xenograft models. Hepatology. 2021;74:2201–2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gulati R, Johnston M, Rivas M, Cast A, Kumbaji M, Hanlon M, et al. β-catenin-cancer-enhancing genomic regions axis is involved in the development of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:2950–2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gulati R, Hanlon MA, Lutz M, Quitmeyer T, Geller J, Tiao G, et al. Phosphorylation-mediated activation of beta-Catenin-TCF4-CEGRs/ALCDs pathway is an essential event in development of aggressive hepatoblastoma. Cancers. 2023;14:6062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tanimizu N, Ichinohe N, Mitaka T. Intrahepatic bile ducts guide establishment of the intrahepatic nerve network in developing and regenerating mouse liver. Development. 2018;145:dev159095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koike N, Tadokoro T, Ueno Y, Okamoto S, Kobayashi T, Murata S, et al. Development of the nervous system in mouse liver. World J Hepatol. 2022;14:386–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bednarsch J, Tan X, Czigany Z, Liu D, Lang SA, Sivakumar S, et al. The presence of small nerve fibers in the tumor microenvironment as predictive biomarker of oncological outcome following partial hepatectomy for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li PY, Ke XL, Zhu Q, Tian DA. Expression and clinical significance of nerve growth factor in primary liver cancer. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2013;21:121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lin H, Huang H, Yu Y, Chen W, Zhang S, Zhang Y. Nerve growth factor regulates liver cancer cell polarity and motility. Mol Med Rep. 2021;23:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu T, Li W, Lu W, Chen M, Luo M, Zhang C, et al. RBFOX3 promotes tumor growth and progression via hTERT signaling and predicts a poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics. 2017;7:3138–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ye B, Liu B, Yang L, Zhu X, Zhang D, Wu W, et al. LncKdm2b controls self-renewal of embryonic stem cells via activating expression of transcription factor Zbtb3 . EMBO J. 2018;37:e97174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lim JH. Zinc finger and BTB domain-containing protein 3 is essential for the growth of cancer cells. BMB Rep. 2014;47:405–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheng ZY, He TT, Gao XM, Zhao Y, Wang J. ZBTB transcription factors: Key regulators of the development, differentiation and effector function of T cells. Front Immunol. 2021;12:713294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Prisco N, Chemiakine A, Lee W, Botta S, Gennarino VA. Protocol to assess the effect of disease-driving variants on mouse brain morphology and primary hippocampal neurons. STAR Protoc. 2022;3:101244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Altevogt P, Ben‐Ze'ev I, Gavert N, Schumacher U, Schäfer H, Sebens S. Recent insights into the role of L1CAM in cancer initiation and progression. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:3292–3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ganesh C, Basnet H, Kaygusuz Y, Laughney AM, He L, Sharma R, et al. L1 CAM defines the regenerative origin of metastasis-initiating cells in colorectal cancer. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:28–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Faini G, Del Bene F, Albadri S. Reelin functions beyond neuronal migration: From synaptogenesis to network activity modulation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2021;66:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kimura K, Ikoma A, Shibakawa M, Shimoda S, Harada K, Saio M, et al. Safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy of the anti-fibrotic small molecule PRI-724, a CBP/beta-catenin inhibitor, in patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: A single-center, open-label, dose escalation phase 1 trial. eBioMed. 2017;23:79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee L, Ramos-Alvarez I, Jensen RT. Predictive factors for resistant disease with medical/radiologic/liver-directed anti-tumor treatments in patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: Recent advances and controversies. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jeong KH, Rim HJ, Kim CW. A study on the fine structure of clonorchis sinensis, a liver fluke: 1. The body wall and the nervous system]. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi. 1978;16:156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vacca M, Murzilli S, Salvatore L, Di Tullio G, D'Orazio A, Lo Sasso G, et al. Neuron-derived orphan receptor 1 promotes proliferation of quiescent hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1518–1529.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lu LL, Sun J, Lai JJ, Jiang Y, Bai LH, Zhang LD. Neuron-glial antigen 2 overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma predicts poor prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6649–6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.