Abstract

The South China giant salamander, Andrias sligoi, is one of the largest extant amphibian species worldwide. It was recently distinguished from another Chinese species, the Chinese giant salamander, Andrias davidianus, which is considered Critically Endangered according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. It appears too late to save this extremely rare and large amphibian in situ. Another extant species of the same genus, Andrias japonicus, inhabits Japan. However, the introduction of Chinese giant salamanders into some areas of Japan has resulted in hybridization between the Japanese and Chinese species. During our genetic screening of giant salamanders in Japan, we unexpectedly discovered four individuals of the South China giant salamander: two were adult males in captivity, and one had recently died. The last individual was a preserved specimen. In this study, we report these extremely rare individuals of A. sligoi in Japan and discuss the taxonomic and conservational implications of these introduced individuals.

Subject terms: Genetic hybridization, Population genetics, Herpetology

Introduction

Giant salamanders are regarded as the largest extant amphibians worldwide and belong to the family Cryptobranchidae, including Andrias and Cryptobranchus. All species are endangered1 and listed on the appendices of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). All extant Andrias species occur in Japan and China (Fig. 1), and their conservation is an urgent concern, particularly in China2–4. Until recently, only the Chinese giant salamander A. davidianus (Blanchard 1871) was known in China; wild populations of this species have declined considerably due to environmental destruction and overharvesting for food and traditional medicine5,6. Numerous commercial farms must have bred giant salamanders using local individuals, as well as non-local individuals from other provinces, because matured brood stocks are usually difficult to collect near the farms; this approach results in the generation of hybridized individuals between genetically differentiated populations. Reintroduction of artificially bred individuals into the wild was conducted to reinforce wild populations4; however, it constituted another threat to the protection of the original genetic diversity and possible cryptic species within A. davidianus7.

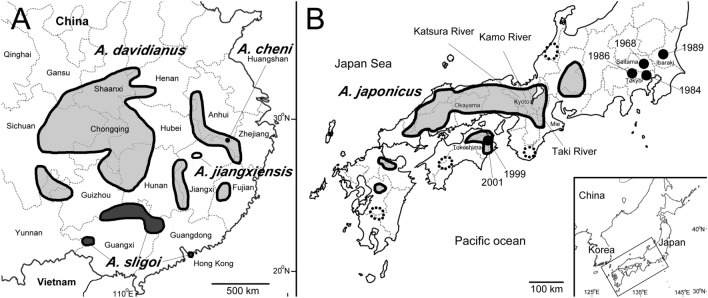

Figure 1.

(A) Map of eastern China showing the original range of A. davidianus (five lightly shaded areas), A. sligoi (three darkly shaded areas), and A. jiangxiensis (one open circle). The locality of A. davidianus in Qinghai Province was omitted in this figure. The ranges were generated based on publications2,4,8. (B) Map of central and southwestern Japan showing the range of A. japonicus (shaded areas). Possible artificial distribution is highlighted by dotted lines. Black circles show collection locations and years of A. davidianus sensu stricto in the wild (two individuals were collected from Saitama in 1986). This figure was generated by Adobe Photoshop 2023 (vers. 24.7.0).

Amid this critical situation in China, the South China giant salamander, Andrias sligoi (Boulenger 1924), was resurrected8, and the Jiangxi giant salamander, A. jiangxiensis Lu, Wang, Chai, Yi, Peng, Murphy, Zhang et Che 2022 and Qimen Giant Salamander, A. cheni Xu, Gong, Li, Jiang, Huang et Huang 2023 were newly described. Turvey et al.8 recovered almost complete mitochondrial genomes from the holotype of A. sligoi collected in 1920 and other museum specimens of Chinese giant salamanders deposited in the late twentieth century before the start of artificial transportation3; they assigned these specimens to the lineages of wild-caught individuals. Although original range of Andrias sligoi is still controversial, it is presumably the largest amphibian among all extant species worldwide8. Unfortunately, when the species was resurrected, it was nearly extinct in the wild because of the situations noted above8.

The genus Andrias includes another extant species, the Japanese giant salamander A. japonicus (Temminck 1836), which was also harvested for food and medicine before World War II. In 1952, the species was legally protected. Nonetheless, the demand for giant salamanders did not decrease, and hundreds of Chinese giant salamanders were imported to Japan as a substitute for the protected native species9. These Chinese giant salamanders were released or escaped into Japanese rivers, then interbred with A. japonicus and established hybrid swarms in several areas of Japan10. To assess the present hybridization situation and to search for living Chinese giant salamanders possibly present in Japan, we conducted genetic surveys. We discovered that the South China giant salamander (believed to be extinct) as well as potentially undescribed species (imperiled in China) present in Japan. Here, we report this unexpected finding, describe the morphology of this rare species for taxonomic implications, and discuss the conservational implications of this invasive but endangered species.

Results

Samples

We made field night surveys in the Kamogawa River, Kyoto, Japan from 2007 to 2015 by visual encounter method and collected 68 tissue samples of the giant salamanders. We also collected five tissue samples of A. cf. davidianus (A. sligoi and U1 lineage: see below) from private houses, aquariums, and zoos throughout Japan (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1.

Samples used for mtDNA analysis in this study together with the information on locality and GenBank accession numbers. Microsatellite identifications are shown in parentheses.

| Sample number | Species | Haplotype clades by Yan et al.4* | Voucher | Locality | Genbank | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andrias davidianus | A | GXXA609 | China, Xingan, Guilin, Guangxi | KU131056 | 11 |

| 2 | Andrias davidianus | A | KIZGXDN3 | China, Maoershan, Guilin, Guangxi | MH051462 | 4 |

| 3 | Andrias davidianus | A | KIZYPX10536 | China, Maoershan, Guilin, Guangxi | MH051461 | 4 |

| 4 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 41349 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650372 | This study |

| 5 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 42280 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650374 | This study |

| 6 | A. japonicas × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 43978 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650375 | This study |

| 7 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 44971 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650376 | This study |

| 8 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 46398 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650377 | This study |

| 9 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 46434 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650378 | This study |

| 10 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 46470 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650379 | This study |

| 11 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 46523 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650380 | This study |

| 12 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 48469 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650381 | This study |

| 13 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 48479 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650382 | This study |

| 14 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 48480 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650383 | This study |

| 15 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 55134 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650384 | This study |

| 16 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (others) | B | KUHE 56198 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650386 | This study |

| 17 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 56599 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650387 | This study |

| 18 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (others) | B | KUHE 56826 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650388 | This study |

| 19 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (others) | B | KUHE 56887 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650389 | This study |

| 20 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 57676 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650390 | This study |

| 21 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 57681 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650391 | This study |

| 22 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 58629 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650392 | This study |

| 23 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 58631 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650393 | This study |

| 24 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 58639 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650394 | This study |

| 25 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 58640 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650395 | This study |

| 26 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 58675 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650396 | This study |

| 27 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (others) | B | KUHE 58678 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650397 | This study |

| 28 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (others) | B | KUHE 58687 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650398 | This study |

| 29 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 58774 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650400 | This study |

| 30 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 58785 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650401 | This study |

| 31 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 58899 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650402 | This study |

| 32 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 58901 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650403 | This study |

| 33 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 58905 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650404 | This study |

| 34 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (others) | B | KUHE 58918 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650406 | This study |

| 35 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 58927 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650407 | This study |

| 36 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 59014 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650408 | This study |

| 37 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE 59085 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Katsura River | LC650409 | This study |

| 38 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 62129 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650410 | This study |

| 39 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650411 | This study |

| 40 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650412 | This study |

| 41 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650413 | This study |

| 42 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650414 | This study |

| 43 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650415 | This study |

| 44 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650416 | This study |

| 45 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650417 | This study |

| 46 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650418 | This study |

| 47 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650419 | This study |

| 48 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (others) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650420 | This study |

| 49 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650421 | This study |

| 50 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650422 | This study |

| 51 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (Backcross of A. davidianus) | B | No voucher | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650425 | This study |

| 52 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (F1) | B | No voucher | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650426 | This study |

| 53 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (others) | B | No voucher | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650427 | This study |

| 54 | Andrias davidianus | B | HNJY390 | China, Wangwoshan, Jiyuan, Henan | KU131048 | 11 |

| 55 | Andrias davidianus | B | HNSZSDJ82 | China, Yuanzi Cave, Shangdongjie, Sangzhi, Zhangjiajie, Hunan | KU131061 | 11 |

| 56 | Andrias davidianus | B | KIZYPX25999 | China, Qingchuan, Guangyuan, Sichuan | MH051426 | 4 |

| 57 | Andrias davidianus | B | KIZYPX44113 | China, Lushi, Henan | MH051424 | 4 |

| 58 | Andrias davidianus (Reference) | B | KUHE 34380 | Unknown locality in China | AB445782 | 14 |

| 59 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 41271 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650428 | This study |

| 60 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 47982 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650429 | This study |

| 61 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 48474 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650430 | This study |

| 62 | A. japonicus × A. davidianus (others) | B | KUHE 55714 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650431 | This study |

| 63 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 56189 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650432 | This study |

| 64 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 56335 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650433 | This study |

| 65 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 56829 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650434 | This study |

| 66 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 58902 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650435 | This study |

| 67 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 59308 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650437 | This study |

| 68 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 62130 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650438 | This study |

| 69 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650441 | This study |

| 70 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650442 | This study |

| 71 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650443 | This study |

| 72 | Andrias davidianus (Reference) | B | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | LC650446 | This study |

| 73 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | No voucher | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650447 | This study |

| 74 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | No voucher | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650448 | This study |

| 75 | Andrias davidianus | B | SCMB244 | China, Mabian, Leshan, Sichuan | KU131043 | 29 |

| 76 | Andrias davidianus | B | YNYL551 | China, Niujie, Yiliang, Zhaotong, Yunnan | KU131053 | 29 |

| 77 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 56597 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650449 | This study |

| 78 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE 56600 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650450 | This study |

| 79 | Andrias davidianus (A. davidianus) | B | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | LC650451 | This study |

| 80 | Andrias davidianus | C | KIZYPX25990 | China, Qingchuan, Guangyuan, Sichuan | MH051427 | 4 |

| 81 | Andrias davidianus | C | KIZYPX25991 | China, Qingchuan, Guangyuan, Sichuan | MH051428 | 4 |

| 82 | Andrias sligoi | D | CQWL481 | China, Wujiang, Yangzte R | KU131051 | 29 |

| 83 | Andrias sligoi | D | GZGDYX583 | China, Xiyejing Cave, Yanxia, Guiding, Qiannan, Guizhou | KU131054 | 29 |

| 84 | Andrias sligoi | D | HNLS55 | China, Mengdonghe, Yuanjiang, Yangzte R | KU131052 | 29 |

| 85 | Andrias sligoi | D | HNWMY48 | China, Wumuyu Cave, Yongding, Zhangjiajie, Hunan | KU131050 | 29 |

| 86 | Andrias sligoi | D | KIZYPX2513 | China, Xinglong, Chongqing | MH051435 | 4 |

| 87 | Andrias sligoi | D | KIZZA2 | China, Zhengan, Zunyi, Guizhou | MH051442 | 4 |

| 88 | Andrias sligoi | D | KIZZA9 | China, Zhengan, Zunyi, Guizhou | MH051443 | 4 |

| 89 | Andrias sligoi | D | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | LC650452 | This study |

| 90 | Andrias sligoi | D | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | LC650453 | This study |

| 91 | Andrias sligoi | D | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | LC650454 | This study |

| 92 | Andrias sligoi | D | KUHE 41444 | Unknown locality in China | LC728249 | This study |

| 93 | Andrias sligoi | D | ROM11041 | China, Xi'an, Shaanxi, Yellow River | MK177470 | 8 |

| 94 | Andrias sligoi | D | Unknown | unknown | NC004926 | 30 |

| 95 | Andrias sligoi | D | ZMB24105 | China, Guangdong or Guangxi, Pearl River | MK177465 | 8 |

| 96 | Andrias davidianus | E | AHHS695 | China, Liukou, Xiuning, Huangshan, Anhui | KU131060 | 29 |

| 97 | Andrias davidianus | E | KIZYPX6151 | China, Huangshan, Anhui | MH051473 | 4 |

| 98 | Andrias davidianus | E | KIZYPX6152 | China, Huangshan, Anhui | MH051474 | 4 |

| 99 | Andrias davidianus | E | ZJLSQY680 | China, Xianliang Cave, Qingyuan, Lishui, Zhejiang | KU131059 | 29 |

| 100 | Andrias davidianus | U1 | CGS1009 | China, Farm-bred (Guangxi) | MH051478 | 4 |

| 101 | Andrias davidianus | U1 | CGS725 | China, Farm-bred (Jiangxi) | MH051480 | 4 |

| 102 | Andrias davidianus | U1 | GXZY587 | China, Zishui, Yangzte R | KU131055 | 29 |

| 103 | Andrias davidianus | U1 | KUHE 65273 | Japan, Tokushima, Komatsushima, Tatsue River | AB445784 | 14 |

| 104 | Andrias jiangxiensis | U2 | CGS291 | China, Farm-bred (Jiangxi) | MH051481 | 4 |

| 105 | Andrias jiangxiensis | U2 | GDLZ365 | China, Lianzhou, Qingyuan, Guangdong | KU131046 | 29 |

| 106 | Andrias jiangxiensis | U2 | JXJA336 | China, Jingan, Yichuan, Jiangxi | KU131044 | 29 |

| 107 | Andrias jiangxiensis | U2 | JXJGS352 | China, Maoping, Jinggangshan, Jian, Jiangxi | KU131045 | 29 |

| 108 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Kumamoto, Asagiri, Kuma River | AB445780 | 14 | |

| 109 | Cryptobranchus alleganiensis | No voucher | unknown | GQ368662 | 31 |

Institutional abbreviations: KUHE Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, ROM Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, ZMB Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin (original names of remaining abbreviations are unkown in the sources).

Table 2.

Samples used for microsatellite analysis in this study.

| Sample number | Species | Voucher/PIT tag number | Locality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 34378 | Unknown locality in China | |

| 2 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 34380 | Unknown locality in China | |

| 3 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 41271 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 4 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 42280 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 5 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 46523 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 6 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 47982 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 7 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 48474 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 8 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 56189 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 9 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 56335 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 10 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 56597 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 11 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 56600 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 12 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 56829 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 13 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 57681 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 14 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 58901 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 15 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 58902 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 16 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 59308 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 17 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE 62130 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 18 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 19 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 20 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 21 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 22 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 23 | Andrias davidianus | KUHE no number | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 24 | Andrias davidianus | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | |

| 25 | Andrias davidianus | No voucher | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 26 | Andrias davidianus | No voucher | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kamo River | |

| 27 | Andrias davidianus | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | |

| 28 | Andrias davidianus | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | |

| 29 | Andrias davidianus | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | |

| 30 | Andrias davidianus | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | |

| 31 | Andrias japonicus | 392145000063723 | Japan, Nara, Fukatani River | |

| 32 | Andrias japonicus | 00075BBD7E | Japan, Nara, Muro River | |

| 33 | Andrias japonicus | 00075BED8C | Japan, Nara, Fukatani River | |

| 34 | Andrias japonicus | 00075C28CE | Japan, Nara, Muro River | |

| 35 | Andrias japonicus | 00075C2DEE | Japan, Nara, Fukatani River | |

| 36 | Andrias japonicus | 00075C2E6B | Japan, Nara, Nagatani River | |

| 37 | Andrias japonicus | 00075C3978 | Japan, Nara, Nagatani River | |

| 38 | Andrias japonicus | 00075C83E1 | Japan, Mie, Muro River | |

| 39 | Andrias japonicus | 00075CB299 | Japan, Mie, Ashouzu River | |

| 40 | Andrias japonicus | 0006B846CB | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kiyotaki River | |

| 41 | Andrias japonicus | 0006B84754 | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Kiyotaki River | |

| 42 | Andrias japonicus | 0006B84E8D | Japan, Kyoto, Kyoto, Katsura River | |

| 43 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 44 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 45 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 46 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 47 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 48 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 49 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 50 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 51 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 52 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 53 | Andrias japonicus | No voucher | Japan, Mie, Maefukase River | |

| 54 | Andrias sligoi | KUHE 41444 | Unknown locality in China | |

| 55 | Andrias sligoi | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | |

| 56 | Andrias sligoi | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | |

| 57 | Andrias sligoi | No voucher | Unknown locality in China | |

| 58 | Andrias davidianus (U1) | KUHE 65273 | Japan, Tokushima, Komatsushima, Tatsue River |

Institutional abbreviations: KUHE Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University.

mtDNA phylogenetic analysis

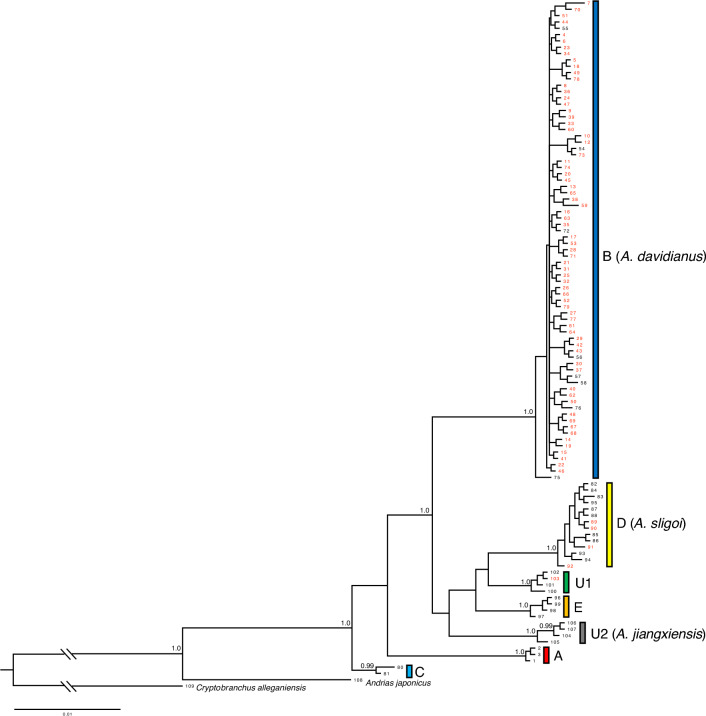

The BI tree obtained based on 590–1141 bp mtDNA cyt b sequences (Fig. 2). The 73 samples collected in this study consisted of three of the seven Chinese mitochondrial lineages reported4: lineages B, D, and U1. Four individuals recovered within lineage D, which is assigned the critically endangered species A. sligoi (Table 1, Fig. 3). Among the three Chinese lineages recovered, lineage B was predominant (Table 1). This lineage is naturally distributed in the Yellow River and Yangtze River drainages. Yan et al.4 reported that the two lineages U1 and U2 were exclusively found in Chinese farms. However, lineage U2 was recently described as A. jiangxiensis based on wild populations. In the present study, one sample collected from Tokushima Prefecture (Sample 103 in Table 1) was assigned to lineage U1.

Figure 2.

Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction of partial cyt b gene sequences from giant salamanders. Lineage assignment was in accordance with Yan et al.4. Red-colored samples were discovered in Japan. Numbers on nodes indicate significant supports (BI ≥ 0.95). For more details regarding sample numbers, see Table 1.

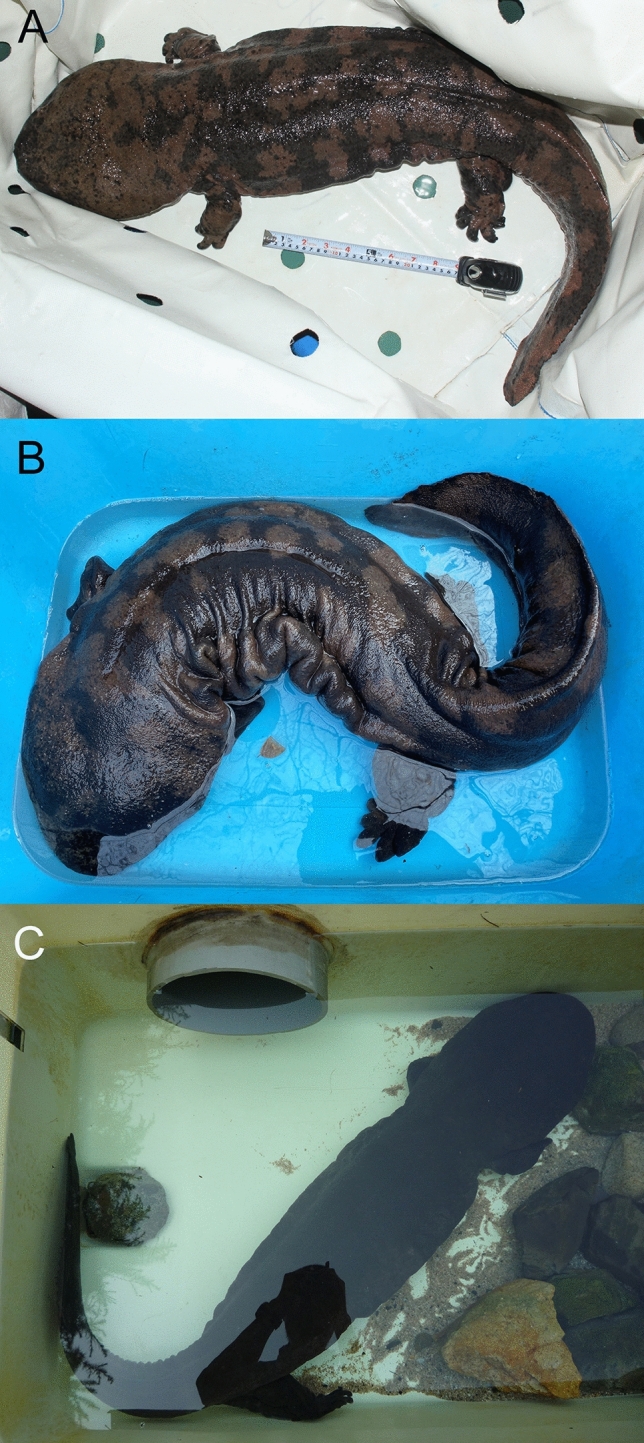

Figure 3.

Photos of A. sligoi in Japan. (A) An individual presently housed at the Sunshine Aquarium, Tokyo, Japan (photo acquired on 25 March 2020). (B) An individual presently housed at the Hiroshima City Asa Zoological Park (photo acquired on 23 December 2021. Copyright: Hiroshima City Asa Zoological Park). (C) A deceased individual once kept in a private house in Okayama Prefecture (photo acquired on 21 June 2011).

Uncorrected p-distances using 810–1141 bp between lineages ranged from 1.4–1.7% (A. sligoi vs. U1 and lineage E vs. U1) to 3.5–4.0% (lineage A vs. U2) (Supplementary information 1***). The genetic distance between A. davidianus (lineage B) and A. sligoi (lineage D) was 2.6–3.2%. The distance between A. japonicus and A. davidianus (lineage B) was 6.0–6.2%.

Microsatellite genotyping

We successfully obtained genotyping data of 14 microsatellite loci for all 68 samples examined, including 45 hybrids and 23 A. davidianus sensu lato. Among the hybrids, 14 were F1, 22 were backcrossed to each parental species, and nine were classified as “other hybrids” whose ancestries are ambiguous. We found no F2 hybrids (Table 2).

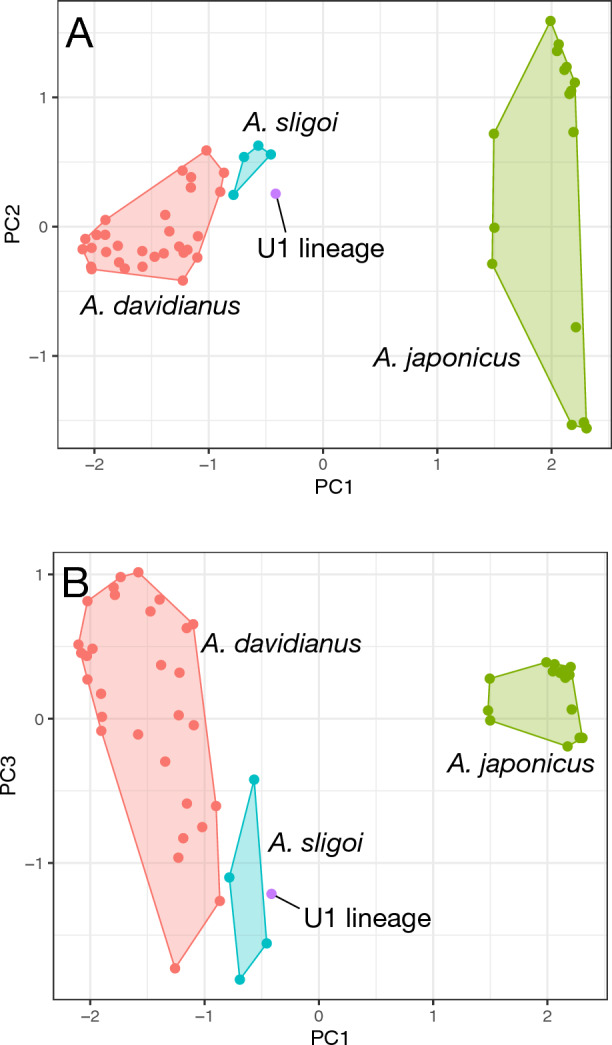

The PCA plot based on 14 microsatellite loci of 58 individuals (including 23 A. davidianus from Kamogawa River [identified by NewHybrids,] seven A. davidianus in captivity, 23 A. japonicus from Kyoto, Mie, and Nara prefectures, four A. sligoi [identified by mtDNA analysis], and one U1 lineage [identified by mtDNA analysis]) revealed two main groups separated along the first axis (43.6%): (1) A. japonicus and (2) A. davidianus, A. sligoi, and U1 lineage, which were identified by mtDNA analysis (Fig. 2). Although A. sligoi and U1 lineage were slightly separated from A. davidianus in the first axis, they largely overlapped in the second (9.2%) and third (6.2%) axes (Fig. 4A,B).

Figure 4.

First and second axes (A) and first and third axes (B) of the PCA plot based on genotype information obtained from microsatellite analyses. A. davidianus: red circles, A. sligoi: blue circles, U1 lineage: purple circle, A. japonicus: green circles.

Sex determination

The two female specimens of A. davidianus showed the expected female-specific bands in the four genetic markers associated with the W sex-chromosome11, whereas the two male specimens did not show any band. These results validate the sexual identification method used in this study. Two living A. sligoi specimens did not show any band and were identified as males; of the other two specimens, the first had died and was deposited as a voucher (KUHE 41444) while the second died and no voucher was kept.

Morphological description of A. sligoi

All four individuals examined (including specimen KUHE 41444 from the museum collection) exhibited a robust and large body structure, as well as a wide and flat head with small dorsal and lateral tubercles (absent on the ventral side) including some paired tubercles. The skin was smooth; cutaneous folds on the lateral body were thick and well-developed. The tail was shorter than the snout-vent length. The body color was highly contrasted, with dark and pale brown colors (Fig. 3A,B). One individual, which recently died, was completely black (Fig. 3C).

One of the specimens, a preserved, large adult female at Kyoto University (KUHE 41444, total length = 1115 mm), had the following ratios of each character to the snout-vent length (698 mm): head length: 32% (223 mm); maximum head width: 32% (226 mm); mouth width: 19% (130 mm); lower jaw length: 15% (104 mm); snout length: 9% (61 mm); internarial distance: 5% (38 mm); interorbital distance: 13% (91 mm); vomerine tooth series width: 10% (68 mm); axilla-groin distance: 53% (370 mm); tail length: 60% (417 mm); medial tail height: 17% (121 mm); medial tail width: 5% (36 mm); forelimb length: 21% (144 mm); hindlimb length: 25% (144 mm); first finger length: 2% (16 mm); second finger length: 4% (30 mm); third finger length: 4% (30 mm); fourth finger length: 4% (25 mm); first toe length: 3% (20 mm); second toe length: 5% (36 mm); third toe length: 6% (42 mm); fourth toe length: 5% (33 mm); and fifth toe length: 4% (27 mm). The finger length and toe length formulae were II = III > IV > I and III > II > IV > V > I, respectively. The specimen had no tubercles from the frontal to parietal regions, and tubercles were lined on the ventral surface of its throat.

The illustration of the type specimen of A. sligoi (Fig. 2 in the work by Turvey et al.8, middle and bottom) shows a typical flat snout similar to the other Chinese species A. davidianus and A. jiangxiensis, with reddish-brown color and only some small black markings on the ventral side; these findings differ from the highly contrasted or monochromatic black coloration observed in the present study (Fig. 4). The color pattern of the illustration of A. japonicus (Fig. 2 in the work by Turvey et al.8, top left) is similar to A. sligoi in our study, as well as the type specimens (Fig. 2 in the work by Turvey et al.8, right). However, the thick head shape in the profile and distinct large tubercles on the head are similar to A. japonicus. The type specimen of A. sligoi had small tubercles on the head, as described by Boulenger12, consistent with observations in the individuals from Japan.

Discussion

In the genus Andrias, hybridization within and between species have occurred both intentionally and accidentally. In this study, most of the non-native individuals found in Japan were hybrids between A. davidianus and A. japonicus, as well as their backcrosses; some pure Chinese giant salamander species were also discovered in this study. These individuals belonged to three of the seven known mitochondrial Andrias lineages, including lineage B corresponding to A. davidianus, lineage D corresponding to A. sligoi, and lineage U1 corresponding to an unknown population found at Chinese farms. These results suggest that the Chinese giant salamanders exported to Japan were collected from multiple locations in China.

Four individuals were identified as A. sligoi via mtDNA analysis, and we determined that they had been imported to Japan in the 1970s to 1980s judging from the information on newspapers at the time10 prior to the start of captive breeding in 1994 in Germany13 and China3, and the release of farmed individuals including hybrids after 20084. Given the information above, these individuals are too large in size (total lengths of the four salamanders are 1100, 1115, 1250, and 1375 mm) to be potential hybrids raised in China. Further, no hybrids have been found in our genetic analyses from available imported Chinese individuals so far. Therefore, we concluded that those four individuals were genetically pure A. sligoi originally collected in China. Morphological examination also supported this identification.

Chinese giant salamander populations have experienced a rapid decline since the 1970s because of extensive collection from the wild2, which supports our estimated time range of importation and hybridization in Japan. Chinese giant salamander individuals have not been imported to Japan since the 1990s. In Japan, Chinese giant salamander adults currently have minimal likelihood of reproducing with conspecific Chinese individuals and must have decreased in number over time, making them more likely to reproduce with A. japonicus and hybrid individuals, than conspecifics. No wild F1 individuals have been observed in monthly surveys since 2011, indicating that the adults of pure Chinese giant salamanders (including A. sligoi) are nearly extinct in Japan. Andrias sligoi is also nearly extinct in China and will soon disappear, even in the introduced refugia of non-original habitats in Japan.

By this study, the four living A. sligoi were discovered in Japan, but the two of them already died. Now the two males are alive in captivity. In 1972, 800 Chinese giant salamander individuals (at least including A. davidianus and A. sligoi) were imported and kept in artificial ponds in a private house in Okayama Prefecture, but 300 of them died within 1 year according to The Asahi Shimbun newspaper on 28 September 1973. Some of the A. sligoi that we discovered in this study may be a part of these remained individuals. One of the two extant A. sligoi was bought from a pet shop in Japan on 25 February 1999, with no information regarding the year of import, but it was likely around 20–30 years ago. This individual is now kept in the Sunshine Aquarium in Tokyo, with a total length of approximately 1250 mm, measured on 25 March 2020. The other male was one of 20 individuals illegally imported from Taiwan to Japan and seized at Osaka International Airport on 13 June 1986. It was kept in the Himeji City Aquarium, and its total length and body weight were measured three times: on 2 August 1986 (305 mm and 113.8 g), on 20 April 1996 (890 mm and 4.6 kg), and on 11 December 2008 (1220 mm and 12.4 kg). The male was eventually transferred to the Hiroshima City Asa Zoological Park in 2008, where it currently measures 1375 mm in total length and weighs 23.4 kg (measured on 23 December 2021). These introduced individuals could be ex situ refugia for critically endangered species. Both individuals were genetically identified as male, and their life spans are near the maximum limit of approximately 60 years (our unpublished data). Therefore, we plan to store their sperm and germ cells in the Frozen Zoo of the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan, for future artificial reproduction. We are urgently searching for remaining Chinese giant salamander species, in China and elsewhere; we are keeping candidate individuals, particularly females, for captive breeding and future reproduction, with closely collaborating to international amphibian conservation acts including the amphibian ark project (https://www.amphibianark.org/). Time is running out to save the world largest extant amphibian species; international collaboration and action are needed to locate and protect this endangered species.

The discovery of A. sligoi individuals has enabled the morphological examination of living individuals by scientists for the first time since its description. The presumed type specimen and its illustration (Fig. 2 in the work by Turvey et al.8, left) are useful for understanding the morphological characteristics. However, the illustrator may have incorrectly depicted the color pattern of A. japonicus instead of A. sligoi, based on our comparisons among the illustrations and the living A. sligoi individuals obtained in this study. Further examinations of specimen morphology remain necessary to clarify the species identification.

The present study revealed a small genetic difference between A. davidianus and A. sligoi in the nuclear genome (Fig. 4) and reconfirmed a small difference in the partial cyt b gene (2.0–3.2%; extended data). The difference in mtDNA is slightly greater than the difference between western and eastern populations of A. japonicus (1.2–1.5% (1.3% on average)14). Murphy et al.7 demonstrated an average allozyme difference of 0.07 between the Pearl River population (Fuchuan; corresponding to A. sligoi) and populations of the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers (Chang’an, Yuanqu, and Dayong; corresponding to A. davidianus sensu lato except for the Huangshan lineage), based on Nei’s genetic distance. This value is also small at the intraspecific level in salamanders (minimum 0.15 between species15), as revealed by our microsatellite result (Fig. 4). Although the genetic differences in giant salamanders tend to be small because of their delayed sexual maturation and longevity8, all available genetic results revealed a small difference between A. davidianus and A. sligoi.

It is inappropriate to conclude that an allopatric population represents a different species solely based on the genetic distance calculated using mtDNA markers. This issue can be addressed by identifying nuclear markers to examine the boundaries of these populations16. If the populations are genetically isolated and represent different species, we would expect to see a drastic transition in genetic composition in and around the contact zone. Otherwise, the transition would be gradual and follow the pattern predicted by the isolation by distance model17. However, A. sligoi was originally described based on an individual that was apparently an escaped captive from a botanical garden in Hong Kong (originally found in a ditch in Hong Kong after heavy rainfall12), a region where native giant salamanders are not known to occur. Although the current distribution of A. sligoi is presumably in southern China (Fig. 1A), its precise range is unknown; the genetic composition of southern populations of A. davidianus sensu lato has been obscured by human-mediated transportation7. Additionally, it is difficult to amplify nuclear sequences from historical specimens stored in museums8. Considering these circumstances, it is challenging to re-evaluate the taxonomic status of A. sligoi using specimens from unaltered localities and additional data of morphology and nuclear markers. All of the morphological characteristics of A. sligoi examined in this study are similar to the characteristics of A. davidianus and A. jiangxiensis. The present study revealed that the external morphologies of living A. sligoi individuals are similar to the morphologies of common living and voucher specimens of A. davidianus that we observed and examined in Chinese zoos, farms, and museums. This finding contradicts Boulenger’s note12 regarding significant differences in morphology between the two species. However, Boulenger described A. sligoi based on the difference from Megalobatrachus maximus (Tschudi 1837), which at that time was believed to include both A. davidianus and A. japonicus. Therefore, Boulenger might have only examined A. japonicus for comparison, suggesting that there have been no comparisons of populations of A. sligoi and A. davidianus for taxonomic validity based on morphology.

Although taxonomic revision of these species is a high priority for the clarification of conservation units, urgent action is needed to protect their genetic diversity. Unfortunately an individual of the lineage U1 detected in Japan by this study died recently. In both China and Japan, artificial transportation must be stopped, and genetically pure populations of these species must be protected.

Online methods

Samples

With permission from the Japan Agency of Cultural Affairs, we collected samples from wild individuals and from individuals kept in private houses, aquariums, and zoos throughout Japan from 2007 to 2015. We deposited voucher specimens in the Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University (KUHE) (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 1). Living Chinese giant salamanders and hybrids identified through genetic surveys were kept in aquariums and zoos for educational and scientific purposes. All experimental procedures in this study followed the experimental animal guidelines of Kyoto University and approved by the Ethics Committee for Human and Animal Research of the Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies of Kyoto University (approval no. 29-A-7 and 30-A-7).

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

We sequenced the mitochondrial cytochrome b (cyt b) genes of the Chinese giant salamanders and hybrids (detected by microsatellite analyses below noted: Table 1). To assign the samples collected in Japan into the genetic groups of Chinese giant salamanders, we compared these sequences with the sequences reported4,8.

We amplified a partial sequence of the cyt b gene region using PCR with the primers L13836 and H1529714 or HYD_Cytb_F1, HYD_Cytb_F2, HYD_Cytb_R1, and Salamander_Cytb_RN218. The PCR products were sequenced with the PCR primers using the ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and BigDye v3.1. We obtained sequences of A. davidianus, A. jiangxiensis, and A. sligoi from GenBank to identify each lineage (Table 1). Sequences were aligned using MAFFT19 with default settings. We conducted phylogenetic analyses using Bayesian inference (BI) methods. The most appropriate substitution model was selected based on the Bayesian information criterion using the Modeltest-NG program20. The BI tree was generated based on 10 million generations of Markov chain Monte Carlo runs using MrBayes v3.2.621. We discarded the first 25% of generations as a burn-in segment, then sampled one of every 100 remaining generations. We verified the convergence of the Markov chain Monte Carlo runs using TRACER v1.622. Posterior probability was used to assess the robustness of BI tree topology. We calculated the uncorrected p-distances of the partial cyt b gene between and within clades using MEGA v7.023. The distance was calculated by pairwise deletion between samples with > 800 base pairs.

Microsatellite analyses

To identify the introduced Chinese giant salamanders and hybrids, we used microsatellite markers developed for giant salamanders24,25. For reference data, we collected Japanese and Chinese giant salamanders in Japan (Table 2, Fig. 1).

We extracted genomic DNA from clipped tail fins using either a standard phenol–chloroform extraction procedure or a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). We selected 14 microsatellite loci (AJP01, 03, 04, 06, 07, 07-2, 08, 08-2, 09, 11, 16, 26, 31, and AJ11824,25) and performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses, using the method of Yoshikawa et al.25. We measured PCR product size using the ABI PRISM 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems) with the GeneScan 500 LIZ size standard.

Based on the genotype, we inferred the hybrid class of each individual (pure A. japonicus, pure A. davidianus, F1, F2, backcross to each parental species) using NewHybrids26. We ran the software for one million sweeps after a burn-in period of 200,000 sweeps. For the analysis, we collected tissues from seven pure A. davidianus in captivity and 23 pure A. japonicus from Kyoto, Mie, and Nara Prefectures (Table 2). The A. davidianus sensu stricto individuals were directly obtained from the police or airports before 1990 and were identified as genetically pure (i.e., not hybridized individuals), although most of them have since died. The A. japonicus individuals were sampled from rivers in which no Chinese or hybridized individuals have been collected thus far. Morphological examination also supported the identification of these two species.

Each individual was classified into one of six categories: A. japonicus, A. davidianus, F1, F2, backcross with A. japonicus, and backcross with A. davidianus. We established the threshold for assignment of individuals to a category as a posterior probability of ≥ 0.8. Individuals with ambiguous ancestry were classified as “other hybrids”.

To survey overall genetic differences among samples of pure A. davidianus, A. japonicus, A. sligoi, and U1 lineage, which were identified by mitochondrial phylogenetic analysis and NewHybrids analysis, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) using genotype information obtained from microsatellite analyses. We performed PCA using GenoDive27.

Genetic sex identification

Sexing giant salamanders based on external characteristics alone is difficult, except during the breeding season. Therefore, we conducted genetic sexing of live A. sligoi. Female-specific genetic markers (i.e., adf225, adf318, adf340, and adf431) were used in accordance with the method of Hu et al.11 to characterize two live giant salamanders identified as A. sligoi. One of the three A. sligoi individuals that had been kept in a private house in Okayama Prefecture likely died in 2020 (about 1100 mm in total length estimated from a photo), and no voucher specimen was collected. Additionally, two male and two female specimens of A. davidianus (KUHE 47438, 56335, 58902, and 58903) were sexed via direct gonad observation.

Morphological examination of A. sligoi

Living A. sligoi specimens were photographed to document their body shape and coloration; their total lengths were measured using a tape measure. Because of the risk of physical harm to the animals, we refrained from detailed examination of their morphology. One voucher specimen of A. sligoi preserved in Kyoto University (KUHE 41444) was measured in accordance with the method of Hara et al.28, and we also measured all fingers and toes. Tubercles on the ventral surface were also confirmed. The body coloration was compared with descriptions by Boulenger12 and the illustration in Fig. 2 of the work by Turvey et al.8.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Himeji City Aquarium, the Sunshine Aquarium, and the Hiroshima City Asa Zoological Park for providing DNA samples and information regarding individual acquisition. We also thank everyone who participated in the field survey of the giant salamander and supported the collection effort. The present study was conducted under the permissions issued by the Japan Agency of Cultural Affairs to Masafumi Matsui and Kanto Nishikawa for research in Kyoto City (no. 420) and in Kyoto Prefecture (no. 710), and Zenkichi Shimizu for research in Iga City, Mie Prefecture (no. 12-65, 12-135, and 26).

Author contributions

K.N., M.M., N.Y., A.T., and K.E.: designed the study; K.N., M.M., N.Y., A.T., K.E., I.F., K.M., Y.H., S.I., T.S., Y.M., Z.S., H.O., and S.H.: conducted fieldwork and laboratory work; K.N. and S.H.: conducted morphological examinations; K.N., M.M., N.Y., K.E., I.F., K.M., and S.I.: conducted molecular analyses; K.N., M.M., N.Y., A.T., K.E., I.F., S.H. and K.F.: wrote the manuscript. The first draft was written by K.N., and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (JPMEERF20204002) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency of Japan to Kanto Nishikawa and by Grants by the Monbukagakusho through the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS: 11640697, 20510215), the Foundation of River and Watershed Environmental management, and Japan Water Agency to Masafumi Matsui.

Data availability

The newly obtained sequences and microsatellite data are deposited in GenBank (cyt b sequence: accession nos. LC650372–LC650454, LC728249) and in figshare (microsatellite: https://figshare.com/search?q=10.6084%2Fm9.figshare.24211173).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-52907-6.

References

- 1.IUCN. The IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2021-3. https://www.iucnredlist.org (2023).

- 2.Wang XM, et al. The decline of the Chinese giant salamander Andrias davidianus and implications for its conserveation. Oryx. 2004;38:197–202. doi: 10.1017/S0030605304000341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham AA, et al. Development of the Chinese giant salamander Andrias davidianus farming industry in Shaanzi Province, China: Conservation threats and opportunities. Oryx. 2016;50:265–273. doi: 10.1017/S0030605314000842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan F, et al. The Chinese giant salamander exemplifies the hidden extinction of cryptic species. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:590–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu C. Amphibians of Western China. Fieldiana Zool. Mem. 1950;2:1–400. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fei L, Hu S, Ye S, Huang Y. Fauna Sinica (Amphibia I) Science Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy RW, Fu J, Upton DE, Lema TD, Zhao EM. Genetic variability among endangered Chinese giant salamanders, Andrias davidianus. Mol. Ecol. 2000;9:1539–1547. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turvey ST, et al. Historical museum collections clarify the evolutionary history of cryptic species radiation in the world’s largest amphibians. Ecol. Evol. 2019;9:10070–10084. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsui, M. Report on DNA analysis of introduced Chinese Giant Salamander. The River Foundation Research Report, The River Foundation, Tokyo, Japan (2006).

- 10.Yoshikawa N. Serious threat on Japanese giant salamander by introduced congeneric species. Human Environ. Forum. 2011;29:36–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Q, et al. Genome-wide RAD sequencing to identify a sex-specific marker in Chinese giant salamander Andrias davidianus. BMC Genom. 2019;20:415. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5771-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulenger EG. On a new giant salamander, living in the Society’s gardens. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1924;1924:173–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1924.tb01494.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haker K. Haltung und Zucht des Chinesischen Riesensalamanders Andrias davidianus. Salamandra. 1997;33:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsui M, Tominaga A, Liu WZ, Tanaka-Ueno T. Reduced genetic variation in the Japanese giant salamander, Andrias japonicus (Amphibia: Caudata) Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2008;49:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Highton R. Biochemical evolution in the slimy salamanders of the Plethodon glutinosus complex in the eastern United States. Part I. Geographic protein variation. Ill. Biol. Monogr. 1989;57:1–78. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hillis DM. Species delimitation in herpetology. J. Herpetol. 2019;53:3–12. doi: 10.1670/18-123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slatkin M, Maddison WP. Detecting isolation by distance using phylogenies of genes. Genetics. 1990;126:249–260. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.1.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsui M, et al. Phylogenetic relationships of two Salamandrella species as revealed by mitochondrial DNA and allozyme variation (Amphibia: Caudata: Hynobiidae) Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2008;48:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katoh K, Kuma KI, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: Improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucle. Acids. Res. 2005;33:511–518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darriba D, et al. ModelTest-NG: A new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020;37:291–294. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rambaut, A., Suchard, M. A., Xie, D. & Drummond, A. J. Tracer version 1.6. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer (2014).

- 23.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshikawa N, et al. Development of microsatellite markers for the two giant salamander species (Andrias japonicus and A. davidianus) Curr. Herpetol. 2011;30:177–180. doi: 10.5358/hsj.30.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshikawa N, Matsui M, Hayano A, Inoue-Murayama M. Development of microsatellite markers for the Japanese giant salamander (Andrias japonicus) through next-generation sequencing, and cross-amplification in its congener. Conser. Genet. Res. 2012;4:971–974. doi: 10.1007/s12686-012-9685-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson EC, Thompson EA. A model-based method for identifying species hybrids using multilocus genetic data. Genetics. 2002;160:1217–1229. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.3.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meirmans PG. GENODIVE version 3.0: Easy-to-use software for the analysis of genetic data of diploids and polyploids. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2020;20:1126–1131. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hara S, Nishikawa K, Matsui M, Yoshimura M. Morphological differentiation among two giant salamanders, Andrias japonicus and A. davidianus, and their hybrids (Urodela, Cryptobranchidae) with a taxonomic implication of the two species. Zootaxa. 2023;5369:42–56. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.5369.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang Z, et al. Phylogenetic patterns and conservation implications of the endangered Chinese giant salamander. Ecol. Evol. 2019;9:3879–3890. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang P, Chen YQ, Liu YF, Zhou H, Qu LH. The complete mitochondrial genome of the Chinese giant salamander, Andrias davidianus (Amphibia: Caudata) Gene. 2003;311:93–98. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(03)00560-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang P, Wake DB. Higher-level salamander relationships and divergence dates inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2009;53:492–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The newly obtained sequences and microsatellite data are deposited in GenBank (cyt b sequence: accession nos. LC650372–LC650454, LC728249) and in figshare (microsatellite: https://figshare.com/search?q=10.6084%2Fm9.figshare.24211173).