Abstract

Objective

Malaysian parents of children diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma stand to benefit from a comprehensive Malay-language online resource, complementing existing caregiver education practices. This study aimed to develop and assess the efficacy of e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education (e-HOPE), an online caregiver education resource in Malay, designed to enhance the knowledge of parents with children diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma in Malaysia.

Methods

A user profile and topic list were established based on previous needs analysis studies. Content was developed for each identified topic. An expert panel assessed the content validity of both informational content and activity sections. Subsequently, the contents were presented via a learning management system to parents of children newly diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma. Parents evaluated the quality of e-HOPE using the Website Evaluation Questionnaire (WEQ) after an 8-week period.

Results

The scale content validity index (S-CVI/Ave) achieved 0.996 for informational content and 0.991 for the activity section. Sixteen parents provided evaluations of e-HOPE after an 8-week usage period. Mean WEQ scores for various dimensions ranged from 4.23 for completeness to 4.88 for relevance.

Conclusions

E-HOPE was meticulously designed and developed to offer Malaysian parents a Malay-language resource complementing current caregiver education practices. It exhibited strong content validity and received positive user ratings for quality. Further assessment is warranted to evaluate its effectiveness in supporting parents of children with leukemia or lymphoma. The resource is anticipated to enhance information accessibility and support for Malaysian parents facing hematological cancers in their children.

Trial registration

Keywords: Pediatrics, Leukemia, Lymphoma, Caregivers, Health education, Internet-based intervention

Introduction

Although childhood cancer represents only 1% of newly diagnosed cancers worldwide, it is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in children.1 Worldwide, there were more than 200,000 cases and nearly 75,000 deaths due to childhood cancer.2 It is important to note that the majority of cases were in low- and middle-income countries where access to care is highly variable.1 Pediatric hematological cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma are the most common forms of cancer in children, both in Malaysia and globally. Leukemia represented 25.1% of cancers in children aged 0–19 years in the year 2020; non-Hodgkin's lymphoma represented 4.5% and Hodgkin's lymphoma represented 0.9%, respectively.3 The primary treatment modality for leukemia and lymphoma in children is chemotherapy. Children with leukemia and lymphoma often require frequent hospital visits and stays for monitoring and treatment, resulting in a heavy caregiving burden on their parents.4

Caregiver education for parents of children with cancer is crucial to empower parents to care for their children. The Children's Oncology Group (COG) expert panel recommended the provision of family-centered education, which not only provides parents with the necessary information but also supports them to cope with the diagnosis and its associated challenges.5 The delivery of caregiver education is highly variable in different countries and is influenced by the availability of resources.6 Low- and middle-income countries were underrepresented in the literature. However, unmet information needs suggest that improvements are needed for conventional caregiver education.7,8 Alongside the conventional method of bedside caregiver education, it is important to provide supporting reference materials that parents can read and re-read at their preferred pace and timing. With the global shift toward the use of information technology, it is also relevant to provide learning resources that can be accessed online.

Delivery of caregiver education to newly diagnosed pediatric cancer patients' parents often uses a combination of methods, including verbal and written information.9,10 The internet is also a medium of instruction that is increasingly being used by these parents.10 It is preferred because it allows parents to access information at their convenience.10 However, identifying credible and easily understandable information can be challenging for parents.11 A review of online resources previously found that the available resources for childhood cancer were poorly designed and difficult to read.12 Over the past decade, more well-designed resources have become available. Reputable online resources such as websites from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society,13 Cancer.Net,14 Together by St. Jude,15 and the Children's Oncology Group16 are examples of comprehensive and easy-to-understand resources for English-literate parents. However, resources for parents who have lower English literacy are greatly needed.17,18

The development of resources in the local language is not as simple as directly translating information from established sources. The resources need to be contextualized for the local culture and health care settings. Some commendable localized resources in the Asia Pacific Region include published e-books in Chinese by the Children's Cancer Foundation in Hong Kong19 and Indonesian online resources on childhood cancer, nutrition, and treatment by the Indonesia Cancer Care Community.20 In some countries, mobile applications have been developed to provide parents with information such as Care Assistant in China and CanSelfMan in Iran.21, 22, 23 However, more resources for different countries are needed. The resources need to be easy to understand and well structured to enable parents to easily find their desired information.24 Such resources are invaluable to supplement efforts for caregiver education and to meet parents' information needs. Parents also desired recommendations for trustworthy information sources to help them avoid the risk of misinformation.

In Malaysia, resources to support parents of children who were newly diagnosed with cancer were extremely limited. The process of caregiver education varied from hospital to hospital. When the diagnosis of cancer is disclosed to parents, they usually participate in a discussion session where they receive verbal general information about cancer and treatment. Caregiver education is often unstructured, is ad hoc, and may be provided by different health care professionals, such as doctors, nurses, or pharmacists.

As a common practice in Malaysia, upon discharge, the child's pediatric oncology team would provide a notebook where information on the child's diagnosis and admissions is recorded. Additional printed information, such as emergency contact numbers and what to do in the event of a fever at home, is provided in the book. The main purpose of this book was for communication with other health care facilities in the event that the child needed medical attention, rather than for caregiver education. However, the book also served to remind the parents on when they needed to bring the child back for the next admission or clinic encounter.

Malaysian parents also rely on cancer parent support groups to guide them with regards to how to provide care for their children.25 These groups were set up by parents of children with cancer and were not part of the formal health care team. The cancer parent support groups helped to provide emotional support for parents of newly diagnosed children and answer questions based on their own experiences. They often formed messaging groups on mobile platforms to provide fast responses to questions from members. Besides providing information and support to parents, the groups may also provide practical help, such as financial aid or fundraising for treatment and medical equipment.

Although the parents do search for information online to supplement information provided by health care providers, they were limited by the lack of a resource in the Malay language as most resources were in English and provided information that was meant for a different health care setting. A national survey found that 96.8% of Malaysians used the internet, further supporting the applicability of an online caregiver education resource.26 To the best of our knowledge, at the time the current study was conceptualized, there was no comprehensive Malay-language online resource available for Malaysian parents. Although an Indonesian website was available,20 important differences in the language and health care settings rendered it less helpful for local parents.

An important concern related to unverified online information sources is the trustworthiness of these sources.27 Some websites may recommend supplements that purport to ‘cure’ the cancer or provide information that deters parents from necessary procedures, such as bone marrow aspiration or lumbar puncture. Such misinformation could result in unwanted consequences.27,28 Hence, a trustworthy source of online information is needed to support the parents.

A comprehensive and easy-to-understand online education resource was needed to supplement current methods of caregiver education in Malaysia.25,29 This was supported by a systematic review on the information needs of relatives of childhood cancer patients.10 The online format would make the information resource easily accessible to parents, whether they were in the hospital or at home, and at their own convenience. In view of the extremely broad information needs for different types of cancer, a decision was made to begin the development of this resource focusing on pediatric hematological cancers, namely leukemia and lymphoma. This was because of the high prevalence of hematological cancers among Malaysian children. If the resource was found to be effective and acceptable, efforts could be made to expand the content to include other forms of childhood cancers, such as solid tumors.

This article aims to report on the design and development of a Malay-language online learning resource for parents of children who were newly diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma. This new resource was named e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education (e-HOPE).

Methods

Study design

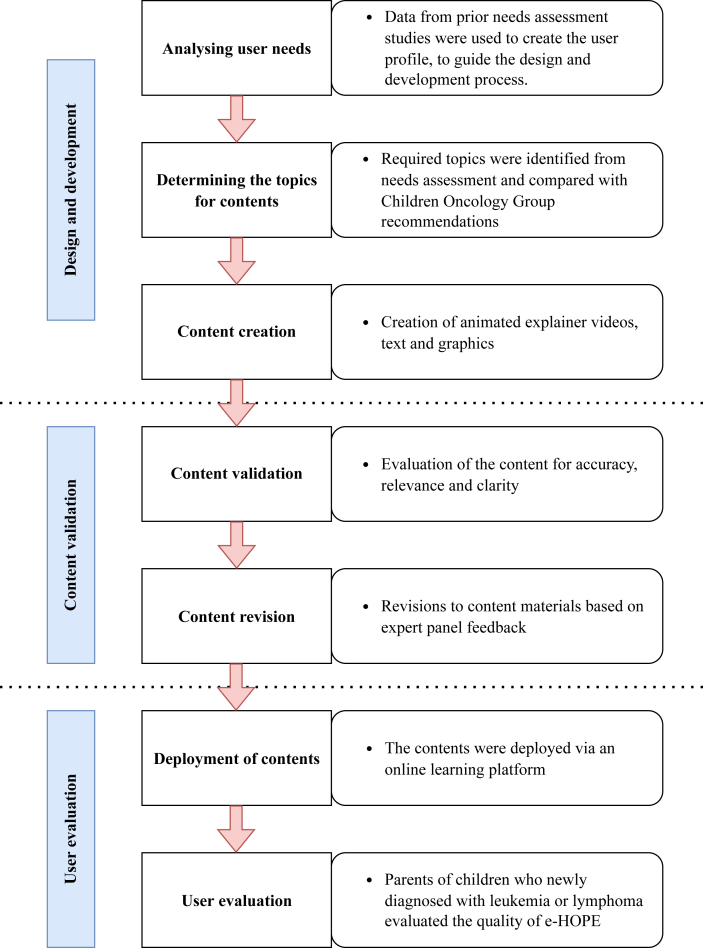

This was a developmental research project comprising three main phases. Developmental research is defined as “the systematic study of designing, developing, and evaluating instructional programs, processes, and products that must meet the criteria of internal consistency and effectiveness”.30 The first phase was the design and development of content materials for the online learning platform. The second phase involved content validation of these resources. The third phase involved user evaluation of e-HOPE. Fig. 1 shows the overall view of the study process.

Fig. 1.

Study process. e-HOPE, e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education.

Design and development of content materials

A good online learning resource should fit the needs of its users. Incorporating a user-centered approach, the online learning materials were designed based on the findings of a prior qualitative needs analysis.25,29 The qualitative needs assessment provided invaluable in-depth knowledge regarding the struggles faced by the parents in obtaining relevant information support and learning how to care for their child. Parents’ demographics and knowledge needs were also obtained from a previous cross-sectional study.31 The findings of the previous study were used to draw up a user profile to describe the potential user.32 The user profile was part of a value proposition canvas, which helped to clarify what the target user needs in order to guide the designer in developing a product that fits their needs.32 The user profile (Table 1) summarized the user characteristics, their goals, their pains or problems that they encounter, and what features would help them to overcome their challenges.

Table 1.

The user profile.

| User characteristics | Goals |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographics31: Age range between 25 and 50 years, with up to secondary level or high school education, and from the lower- to middle-income group. Ability and desire to access online information via their mobile device or computers.25 |

To understand the disease and treatment process.25,31 To support medical decision-making and caregiving.25,29 To learn how to care for the child at home.29 To obtain support and cope with stress.29 To learn how to get credible information and discuss it with health care professionals. |

| Pains |

Gains |

| Does not fully understand the disease and treatment process.25 | Simplify the explanation of medical information in layman terms. Brief interactive activities to assess understanding and provide feedback. |

| Overwhelmed by various information.25,29 Lack of concentration due to caregiving demands.25,29 |

Provide information in short chunks. Accessibility of information based on the parents' needs. Use a blend of text, graphics, and videos to minimize cognitive load. Ensure videos are specific and not longer than 3 min. |

| Need guidance on identifying credible sources of information.25 | Provide guidance on how to identify credible information sources and evaluate the trustworthiness of the information. |

| Experiencing emotional stress and anxiety.25,29 | Include resources on self-care and coping. |

A list of topics was drawn up for the development of contents for e-HOPE. The topics were identified from the previous qualitative needs assessment and refined to ensure relevance to childhood leukemia and lymphoma. These topics were then arranged under specific modules to make it easy for parents to identify their desired information content.

Contents were prepared for each topic as either graphics with brief explanatory text, doodle animations, or character animations. The contents were written based on available online caregiver information and literature review.9,13, 14, 15, 16 They were substantively vetted by a consultant pediatric hematologist. To ensure applicability to various institutions, the contents did not highlight setting-specific practices such as the availability of certain clinical services. Being mindful that chemotherapy protocols may be variable across different centers and individualized according to the children's risk status, only general information on treatment was provided. The information was provided with a reminder that parents should discuss with their child's treating oncologist regarding their child's treatment regime. Links to additional online resources, which have been vetted to ensure credibility and ease of understanding, were also provided to cater for parents who wished for more detailed information. These external resources were in English as online resources in Malay were not available.

Videos were selected as the medium for topics that required longer explanations but were kept within a maximum duration of 3 min. Graphics with brief explanatory text were used for topics that were aimed as fast reference for parents, such as symptom management at home. Toonly software (Enterprise Version: 1.7.8, 2021) was used to create character animation videos, whereas Doodly software (Enterprise Version: 2.7.4, 2021) was used to create doodle animation videos. A content script was written for each video in Malay, with care to use layman terms to explain medical terminology. A storyline for each video was created based on the script. A voice recording of the narration was included in the video.

To enhance the understanding of parents, four online activities were created. These activities were aimed at reinforcing parents' caregiving knowledge at home after the child's discharge, developing strategies to optimize their communication sessions with health care professionals, evaluating the credibility of an alternative treatment advertisement, and identifying a suitable coping strategy when facing a challenging situation. These objectives were determined based on needs that were identified to be important to parents during the previous qualitative needs assessment study.25,29 These activities were designed as guided question-and-answer exercises and were aimed at enhancing deeper learning among parents.

Content validation of the content materials

Content validation was done to evaluate whether the materials were relevant and appropriate for the objective of educating parents of newly diagnosed children with leukemia or lymphoma. A content validation method used for e-Health interventions was adapted for this purpose.33 This method used a modified content validity index, which was usually used for questionnaire validation and had been used for the validation of online resources and educational modules in other studies.34, 35, 36

A panel of seven content experts was formed to evaluate the content validity of e-HOPE materials. The panel consisted of a consultant pediatric hematologist and oncologist, a consultant palliative pediatrician, a family medicine specialist with a medical education background, a registered nurse with experience in the pediatric oncology ward, a psychologist, and an experienced parent of a child with leukemia and an experienced parent of a child with lymphoma. Both parents in the expert panel group were also active members of their local cancer parent support group.

The draft of the contents and the videos were shared with the content experts for evaluation. These included the informational contents and the activities. The expert panel was briefed regarding the objective of the validation process and provided with a structured content validation evaluation form for each section. They were given the learning objectives for each informational topic and activity. The form was adapted from a similar website validation study.36 The content validation evaluation form is provided as Supplementary Table S1. The members of the expert panel had to rate their agreement with each item on a scale of 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree).

The content validity index for each item (I-CVI) on the evaluation form was determined by the proportion of a rating of 3 (agree) or 4 (totally agree) over the total number of raters.37 The content validity index for the scale (S-CVI/Ave) was obtained by calculating the average I-CVI of each topic. I-CVI of more than 0.78 and S-CVI/Ave of more than 0.90 indicated good content validity for a panel of seven experts.37 Revisions to the content were made based on the written feedback from the expert panel. This included the addition of topics (e.g., caregiver precautions when the child is on chemotherapy) or breaking up certain videos into two topics. A second round of evaluation was given by the same expert panel, and the results for the I-CVI and S-CVI/Ave are presented in section 3.2.

User evaluation of e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education

The contents of e-HOPE were deployed via a learning management system. A learning management system is a software program that helps simulate a face-to-face learning environment in an online setting.38 The commercial learning management system Xperiencify™ was chosen for this purpose as it had the necessary features needed for the conduct of the feasibility trial.39 These included learner management features, the ability to host video content, customizability, interactive questions, and gamification features to keep learners engaged with the course.

Registered users were able to access e-HOPE contents via various devices, including computers, tablets, and smartphones. Users only required internet access via a browser. Mobile-responsive design allowed for an automatic change in layout depending on which device was used to access the content.40 A web-based platform was also not confined by operating system requirements and was comparatively cheaper than developing a mobile application.40

User evaluation of e-HOPE was nested within a randomized controlled feasibility trial, which was prospectively registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05455268). The study involved Malay-literate adult parents of children (aged below 18 years) who were diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma in the preceding three months and receiving treatment from either one of two pediatric oncology units in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Being newly diagnosed in the preceding three months, the children were in the beginning phase of their chemotherapy treatment. The parents were eligible for inclusion if they were able to access the internet for health information and had an active email account. Spouses of recruited parents and parents experiencing severe emotional distress were excluded from the study.

The feasibility trial was conducted to evaluate the implementation and preliminary effectiveness of e-HOPE. A pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) with a continuous outcome variable and an expected small effect size would require 25 participants per arm. This was increased to 32 per arm to account for a possible 20% attrition. The recruitment duration was capped at 6 months in view of the fact that this was a feasibility trial.

Upon recruitment and randomization, all parents received standardized training by the first author on how to access and use e-HOPE. The training was delivered based on a standardized training brochure, and the brochure was also given to the parents for their reference. The parents of the intervention arm of this feasibility trial received full access to e-HOPE for two months (or 8 weeks). Parents were allowed to access any topic that they wished, based on their individual needs, and were not required to complete all modules during the intervention period. They were however required to complete the four activities, which were released every fortnight. Each activity had to be completed within two weeks. Upon completion of the intervention period, they completed the Website Evaluation Questionnaire (WEQ), which was a usability-focused quality assessment tool for informational websites.41,42 The WEQ consisted of 26 items that measured eight dimensions of quality, including ease of use, hyperlinks, structure, relevance, comprehension, completeness, layout, and search option.42 Of these, relevance, comprehension, and completeness were related to the informational content, whereas other dimensions reflected the usability of the website related to navigation and layout.41 The parents provided their responses on a Likert scale of 1–5, and the mean scores for each dimension were calculated. Higher mean scores represented better quality for each dimension.

A total of 16 participants completed the evaluation at the end of the intervention period. The mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range of the WEQ scores were presented as a descriptive analysis.

Results

Content materials for e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education

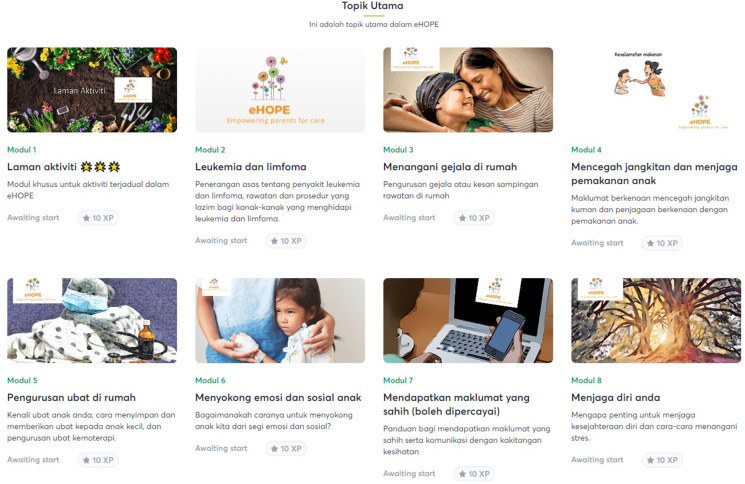

The final structure of e-HOPE consisted of eight modules, of which one was the activity module. Fig. 2 shows a screenshot of the modules on the online learning platform. The topics included in the modules are shown in Table 2. The topics were compared with the education checklist recommended by COG.43

Fig. 2.

Screenshots of modules in e-HOPE. e-HOPE, e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education.

Table 2.

Content topics in comparison with the COG checklist.

| Categories of information | e-HOPE topics | COG checklist | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Module 1: Activities | |||

| Care for the child at home | Care of your child at home after discharge from the hospital | Care of the child: Temperature taking When to call for help Who to call for help Home medication names and purposes |

1 |

| Interaction with the health care system | Communication strategies with health care professionals | – | – |

| Guidance for information gathering | Evaluating the trustworthiness of an advertisement for alternative medicine | – | – |

| Self-care for caregivers | Identifying a suitable coping approach | Coping skills | 3 |

| Module 2: Leukemia and lymphoma | |||

| Disease-related information | What is leukemia? | What is cancer? | 2 |

| What is lymphoma? | What is cancer? | 2 | |

| How does leukemia or lymphoma occur? | What is cancer? | 2 | |

| Bone marrow testing (BMAT) | What is cancer? | 2 | |

| Lumbar puncture (LP) | What is cancer? | 2 | |

| What are the chances for cure with treatment? | What is cancer? | 2 | |

| Treatment-related information | How is leukemia or lymphoma treated? | Meeting with the physician team for a diagnosis and treatment plan | 1 |

| What is chemotherapy? | Meeting with the physician team for a diagnosis and treatment plan Chemotherapy overview |

2 | |

| What is radiotherapy? | Meeting with the physician team for a diagnosis and treatment plan | 1 | |

| What are the side effects of chemotherapy? | Treatment side effects to know before the next appointment Effects of cancer treatment on the bone marrow Other side effects |

1, 2 | |

| What is a central venous line (CVL)? | Care of the central line | 1, 2 | |

| What is a chemoport? | – | – | |

| What is palliative care? | – | – | |

| Module 3: Handling symptoms at home | |||

| Medical caregiving | Fever | Fever When to call for help Who to call for help |

1 |

| Nausea and vomiting | Other side effects When to call for help |

2 | |

| Reduced appetite | Other side effects | 2 | |

| Mouth sores | Other side effects | 2 | |

| Hair loss | Other side effects | 2 | |

| Fatigue or tiredness | Other side effects | 2 | |

| Bruises, red spots, or bleeding | When to call for help? | 1 | |

| Module 4: Preventing infections and managing your child's diet | |||

| Medical caregiving | Preventing infections | Preventing infections | 1 |

| Food safety guidelines | Preventing infections | 1 | |

| Basic activities of daily living | A balanced diet | Nutrition | 2 |

| Vitamins and supplements | Nutrition | 2 | |

| When my child does not want to eat | – | – | |

| Module 5: Medication management at home | |||

| Medical caregiving | Understanding medication labels and prescriptions | Home medication: Names and purposes, dose and frequency | 1 |

| Medication storage | Home medication: Storage | 1 | |

| Liquid oral medications (how to prepare oral suspensions) | Home medication: Administration | 1 | |

| Giving tablet medications to young children | Home medication: Administration | 1 | |

| Giving medications as scheduled | Home medication: Administration | 1 | |

| When my child refuses to take medications | Home medication: Administration | 1 | |

| Special precautions while my child is receiving chemotherapy | Chemotherapy safe-handling/item disposal | 1 | |

| Module 6: Supporting my child emotionally and socially | |||

| Psychosocial caregiving for the child | Should I tell my child about the diagnosis? | Talking with child and siblings about cancer | 3 |

| How children understand their illness | Talking with child and siblings about cancer | 3 | |

| How do I tell my child about cancer | Talking with child and siblings about cancer | 3 | |

| Understanding and supporting your child's emotions | Talking with child and siblings about cancer | 3 | |

| Supporting your child during a procedure or treatment | Talking with child and siblings about cancer | 3 | |

| Between discipline and love | – | – | |

| Schooling during the treatment period | Work and school absences | 3 | |

| Supporting your child's social interaction | – | – | |

| Module 7: Obtaining credible information | |||

| Guidance for information gathering | Characteristics of trustworthy information sources | – | – |

| Evaluating appropriateness of alternative treatment | – | – | |

| Health system navigation | Introducing the roles of different health care professionals | Meeting with the physician team for diagnosis and treatment plan | 1 |

| Introduction to emergency department | 2 | ||

| Introduction to outpatient nurse and/or clinic tour | 2 | ||

| Introduction to child life specialist | 3 | ||

| Communicating with health care professionals | – | – | |

| Module 8: Taking care of yourself | |||

| Self-care for caregivers | Why is it important to take care of yourself? | Coping skills | 3 |

| Obtaining practical support needs | Practical support | Meeting with social worker | 1 |

| Self-care for caregivers | Coping with stress | Coping skills | 3 |

| Problem-focused approach for coping | Coping skills | 3 | |

| Emotion-focused approach for coping | Coping skills | 3 | |

E-HOPE, e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education; COG, Children's Oncology Group.

Content validation of e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education

Table 3 shows the content validity indices for the informational contents and the activities section. Following one round of revision, the S-CVI/Ave were 0.996 and 0.991 for the informational contents and activities section, respectively. Both sections had good content validity, indicating that the panel of experts agreed on the relevance, alignment with objectives, and appropriateness of the materials developed for e-HOPE.

Table 3.

Content validity indices for e-HOPE.

| Content validation for informational content | Mean I-CVI | Content validation for activities section | Mean I-CVI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contents are accurate based on current knowledge. | 0.972 | The objectives are evident in the activity. | 1.000 |

| Objectives are evident | 1.000 | The activity will help user to achieve the objective. | 1.000 |

| Information provided is necessary. (Or, there is no unnecessary information included) | 1.000 | The activity is simple and easy to understand. | 0.965 |

| All important points are included. | 1.000 | The activity will be useful for the user to help them understand information in e-HOPE. | 1.000 |

| The language is easily understood. | 1.000 | The objectives are evident in the activity. | 1.000 |

| The information is well-organized and easy to find. | 1.000 | ||

| The video clips are useful to aid understanding of the content. | 1.000 | ||

| S-CVI/Ave for informational content | 0.996 | S-CVI/Ave for activities section | 0.991 |

I-CVI, item-level content validity index; S-CVI/Ave, averaged scale-level content validity index; e-HOPE, e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education.

User evaluation of e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education

A total of 64 parents were approached, but only 51 consented and were randomized. There were 27 parents who were randomized to the intervention arm. However, due to the deaths of the child (n = 2) and the losses to follow-up (n = 9), only 16 parents (59.26%) completed the intervention period and provided feedback on their evaluation of the e-HOPE contents. Table 4 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the parents and their child's clinical characteristics. The mean parent's age was 39.13 years (SD = 6.50). The majority were women (n = 13, 81.25%), of Malay ethnicity (n = 14, 87.50%), and from the low-income group (n = 11, 68.75%). Half of the parents had tertiary-level education. Three-quarters of the parents had a child diagnosed with leukemia.

Table 4.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the parents and their child's clinical characteristics (N = 16).

| Variables | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent's age, years | 39.13 (6.50) | 39.00 (11.00) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3 (18.75) | ||

| Female | 13 (81.25) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Malay | 14 (87.50) | ||

| Non-Malay | 2 (12.50) | ||

| Education | |||

| Tertiary | 8 (50.00) | ||

| Nontertiary | 8 (50.00) | ||

| Income | |||

| Low income | 11 (68.75) | ||

| Middle- and high-income | 5 (31.25) | ||

| Child's age, years | 6.02 (4.92) | 4.13 (8.75) | |

| Child's diagnosis | |||

| Leukemia | 12 (75.00) | ||

| Lymphoma | 4 (25.00) | ||

| Child's duration of diagnosis, months | 1.00 (0.82) | 1.00 (2.00) | |

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

The participants rated all eight dimensions of the WEQ highly (Table 5). Of note, the highest scores were for relevance (mean = 4.88, SD = 0.27), hyperlinks (mean = 4.70, SD = 0.40), and structure (mean = 4.67, SD = 0.42). The areas of e-HOPE that needed improvement were completeness (mean = 4.23, SD = 0.65), layout (mean = 4.48, SD = 0.47), and the search option (mean = 4.56, SD = 0.65).

Table 5.

Mean scores of the WEQ (N = 16).

| Dimensions of the WEQ | Mean | SD | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevance | 4.88 | 0.27 | 5.00 | 0.00 |

| Comprehension | 4.63 | 0.57 | 5.00 | 0.58 |

| Completeness | 4.23 | 0.65 | 4.33 | 0.65 |

| Ease of use | 4.58 | 0.55 | 4.83 | 0.92 |

| Structure | 4.67 | 0.42 | 4.88 | 0.69 |

| Hyperlinks | 4.70 | 0.40 | 5.00 | 0.50 |

| Search option | 4.56 | 0.65 | 5.00 | 0.92 |

| Layout | 4.48 | 0.47 | 4.33 | 1.00 |

WEQ, Website Evaluation Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Discussion

This study reported the development and validation of content materials for e-HOPE, an online learning resource for Malaysian parents of children with leukemia or lymphoma. E-HOPE was found to have good content validity for both the informational contents and activities sections. User evaluation showed that the parents rated e-HOPE highly.

e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education as a supplement to current caregiver education

Caregiver or parent education in high-resource pediatric oncology settings was commonly delivered in person, primarily by advanced practice nurses.6 Education could be individualized and allow for hands-on skill training. Conversely, in centers with limited resources, the provision of caregiver education was hampered by insufficiently trained staff, a high patient load, and a lack of resource materials to support the education process. The purpose of e-HOPE was not to take over the role of direct training but as a supplementary resource to aid parents in learning how to care for and support their child during the treatment process. Therefore, the contents were designed as a general reference for parents. Certain information such as those related to individual treatment plans was best delivered by the pediatric oncologist, whereas e-HOPE provided only general information regarding chemotherapy and its side effects.

Having a standardized caregiving education resource was also helpful to health care professionals such as nurses and junior doctors. It could help them to provide consistent and trustworthy information. Contradicting information about pediatric cancer care could result in more distress for the parents.44 Therefore, having a standardized and trustworthy resource would be helpful for training junior health care professionals, as well as facilitating their tasks in providing information to parents of newly diagnosed children.

Comparison of e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education with Children's Oncology Group checklist

Upon comparison, e-HOPE had covered most of the topics listed in the COG checklist with some differences. The COG checklist was created to guide nurse educators to provide education to parents of children who were newly diagnosed with cancer.43 Topics in the COG checklist were divided into three timelines: primary topics were to be completed before the first hospital discharge, secondary topics were to be completed within the first month of diagnosis, and tertiary topics were to be completed before the end of treatment. In general, both e-HOPE and the COG checklist covered the basics of disease and treatment-related information, medical caregiving, and psychosocial care for the child, as well as referrals for support in terms of financial resources. However, there were some differences.

Some differences were due to the mode of delivery for certain educational content. For example, topics such as the demonstration of central line flush or the demonstration of cap change were best carried out in person. Similarly, meetings with the actual teams or health services had to be conducted in person. In the COG checklist, there were specific topics on introduction to the emergency department and introduction to the outpatient nurse or clinic tour. As different hospitals had different systems in place, e-HOPE contents did not specifically include these topics but introduced the roles of different health care professionals.

Differences in the care process between Malaysian pediatric oncology centers and other high-resource centers also contributed toward the divergence of the contents. For example, a general assessment of psychosocial needs was often performed by the physician's team in Malaysia instead of by the medical social worker as listed by the COG checklist. When psychosocial needs were identified, the family would then be referred to a medical social worker or counselor as needed. Another difference was that there were no child life specialists in Malaysian hospitals. The topic “Introducing the Roles of Health Care Professionals” in e-HOPE included an explanation of the different roles of physicians, different physician teams in hospitals, nurses, pharmacists, and medical social workers. Timing for discussion with different health care professionals could be challenging due to the busy care environment.7 Therefore, a topic on “Communicating with Health Care Professionals” provided a primer to guide parents on preparing a list of questions, identifying which healthcare professional would be the best to meet their needs, and arranging for a planned session for discussion.

The module on evaluating the credibility of information was also necessary for the local population. A prior local needs assessment study found that parents needed guidance on evaluating the credibility of information sources and applying information to their own child's context.25 In terms of culture, the prevalent undisclosed use of alternative medicine also necessitated a section to guide them in evaluating potential alternative medicine advertisement.45,46 Therefore, e-HOPE included these topics although they were not listed in the COG checklist. These topics were meant to guide parents with lower health literacy to assess the possibility of misinformation when their peers shared about alternative medicine for their consideration.

User evaluation of e-Hematological Oncology Parents Education

The contents of e-HOPE were rated highly for relevance and comprehension. On the other hand, the parents felt that the information provided within e-HOPE could be improved. Despite the generally high ratings, completeness was rated relatively lower than other domains. This shows that parents wished for more details in the information content. Feedback on areas that were lacking in completeness was needed to develop new contents to improve completeness.

Usability is closely related to website quality.41 In the context of websites, usability is defined as a quality attribute regarding how easy it is to use the website, including how fast a person can learn to use it, efficiency while using it, how well they remember it, how error-prone it is, and how much they enjoy using it.47 The scores on the WEQ showed that the parents were satisfied with the navigation and layout of the site. Improvements could be made in terms of the appearance and appeal of the website design by using professional images and designs. Some aspects of the design and the search function were related to the customization and features of the learning management system.

There were very few published studies on user evaluation of educational websites for parents of children with leukemia or lymphoma. An Icelandic web-based educational and support intervention was evaluated using a qualitative study and found that most parents rated the website favorably.48 A mobile application for the provision of information support to parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in China helped parents feel better prepared to care for their child by providing more credible and professional information.22 The COG also released a smartphone application to help meet the informational needs of parents of children with cancer. The mobile app was also highly rated by the eight parents and fourteen clinicians who evaluated the app.49 These studies showed that online and e-health resources were highly acceptable by parents of children with cancer.

Implications for nursing practice and research

E-HOPE will be a useful resource for Malay-literate parents and may be expanded to include more contents as necessary in the future. The study may also provide a helpful reference for researchers who would like to develop online caregiver education resources for non-English-speaking populations. It is extremely important to ensure that the developed contents are contextualized to the local needs and settings. Such resources would be helpful to support caregiver education in oncology nursing.

Strengths and limitations

Overall, e-HOPE was a useful reference material to supplement the current provision of parent education for newly diagnosed pediatric leukemia and lymphoma. It was the first comprehensive online resource in the Malay language for local parents. The contents were developed based on a local needs assessment and contextualized for the local health care setting. E-HOPE had good content validity and received good ratings by users.

This study was limited by the small number of users rating the quality of e-HOPE. Only parents in the intervention arm of the feasibility trial completed the user evaluation, resulting in a small sample size. Most user evaluations were conducted with sample sizes ranging from 12 to 30 participants.50 Despite the small sample size, this study provided a preliminary evaluation of e-HOPE and showed that additional improvements for the completeness of the information were needed. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of e-HOPE in improving parents’ knowledge.

Conclusions

In conclusion, e-HOPE is a pioneer Malay language online resource that was designed to supplement parent education for Malaysian parents of children with leukemia and lymphoma. E-HOPE has the potential to support parents who need reference materials to help them understand their child's condition and to support them in caring for their child during the treatment period. Although e-HOPE still has areas for improvement, it is a useful tool to complement health care professionals' caregiver education efforts.

CRediT author statement

Chai-Eng Tan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft. Novia Admodisastro: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing. Sie Chong Doris Lau: Validation, resources, Funding acquisition, Writing- Review & Editing. Kit Aun Tan: Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. Kok Hoi Teh: Validation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing. Chee Chan Lee: Validation, Resources. Sherina Mohd Sidik: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing. All authors had full access to all the data in the study, and the corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Declaration of competing interest

Chai-Eng Tan was a doctoral student of Universiti Putra Malaysia at the time of this study and an academic staff of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Sherina Mohd Sidik, Novia Admodisastro and Kit Aun Tan were supervisors for her doctoral study. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the UKM Medical Faculty Fundamental Grant (GFFP) (Project code FF-2021-256). The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from both Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Research Ethics Committee (JEP-2021-413) and Malaysian Ministry of Health (NMRR-21-613-58896). Data collection was commenced only after ethical approval was obtained. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, CET. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions their information could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

No AI tools/services were used during the preparation of this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to CAKNE, the cancer parent support group of UKM Children's Specialist Hospital for their support and contribution, and all members of the content expert panel. Sincere thanks to the staff of the pediatric oncology units of UKM Children's Specialist Hospital and Hospital Tunku Azizah for supporting the study. The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for permission to publish this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjon.2023.100363.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bhakta N., Force L.M., Allemani C., et al. Childhood cancer burden: a review of global estimates. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):e42–e53. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30761-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma R. A systematic examination of burden of childhood cancers in 183 countries: estimates from GLOBOCAN 2018. Eur J Cancer Care. 2021 Sep 1;30(5) doi: 10.1111/ecc.13438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J., Ervik M., Lam F., et al. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today.https://gco.iarc.fr/today [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferraz A., Santos M., Pereira M.G. Parental distress in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a systematic review of the literature. J Fam Psychol. 2023 doi: 10.1037/fam0001113. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landier W., Ahern J., Barakat L.P., et al. Patient/family education for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients: consensus recommendations from a children's oncology group expert panel. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016;33(6):422–431. doi: 10.1177/1043454216655983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Withycombe J.S., Andam-Mejia R., Dwyer A., Slaven A., Windt K., Landier W. A comprehensive survey of institutional patient/family educational practices for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients: a report from the children's oncology group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016;33(6):414–421. doi: 10.1177/1043454216652857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aziza Y.D.A., Wang S.T., Huang M.C. Unmet supportive care needs and psychological distress among parents of children with cancer in Indonesia. Psycho Oncol. 2019;28(1):92–98. doi: 10.1002/pon.4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barata A., Wood W.A., Choi S.W., Jim H.S.L. Unmet needs for psychosocial care in hematologic malignancies and hematopoietic cell transplant. Curr Hematol Malig R. 2016;11(4):280–287. doi: 10.1007/s11899-016-0328-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodgers C.C., Laing C.M., Herring R.A., et al. Understanding effective delivery of patient and family education in pediatric oncology: a systematic review from the children's oncology group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016;33(6):432–446. doi: 10.1177/1043454216659449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilic A., Sievers Y., Roser K., Scheinemann K., Michel G. The information needs of relatives of childhood cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Patient Educ Counsel. 2023;114 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2023.107840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gage E.A., Panagakis C. The devil you know: parents seeking information online for paediatric cancer. Sociol Health Illness. 2012;34(3):444–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stinson J.N., White M., Breakey V., et al. Perspectives on quality and content of information on the internet for adolescents with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(1):97–104. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Children and young adults. 2022. https://www.lls.org/children-and-young-adults

- 14.American Society of Clinical Oncology . Cancer.Net; 2022. Navigating cancer care for children.https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/children [Google Scholar]

- 15.St. Jude children's research hospital. Together by St. Jude; 2022. https://together.stjude.org/en-us/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Children’s Oncology Group . Children’s Oncology Group; 2022. Patients and families.https://childrensoncologygroup.org/patients-and-families [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Shamsi H., Almutairi A.G., Al Mashrafi S., Al Kalbani T. Implications of language barriers for healthcare: a systematic review. Oman Med J. 2020 15;35(2):e122. doi: 10.5001/omj.2020.40. e122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maree J.E., Parker S., Kaplan L., Oosthuizen J. The information needs of South African parents of children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016;33(1):9–17. doi: 10.1177/1043454214563757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Children's Cancer Foundation . Publications; 2022. Books.https://www.ccf.org.hk/en/publications/publications/books/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Indonesia Cancer Care Community ICCC Indonesia cancer care community. 2022. https://iccc.id/

- 21.Mehdizadeh H., Asadi F., Nazemi E., Mehrvar A., Yazdanian A., Emami H. A mobile self-management app (CanSelfMan) for children with cancer and their caregivers: usability and compatibility study. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2023;6 doi: 10.2196/43867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J., Yao N., Shen M., et al. Supporting caregivers of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia via a smartphone app. Comput Inform Nurs. 2016;34(11):520–527. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J., Howell D., Shen N., et al. mHealth supportive care intervention for parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: quasi-experimental pre- and postdesign study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(11):e195. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenzang K.A., Scavotto M.L., Revette A.C., Schlegel S.F., Silverman L.B., Mack J.W. “There's no playbook for when your kid has cancer”: desired elements of an electronic resource to support pediatric cancer communication. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023;70(3) doi: 10.1002/pbc.30198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan C.E., Lau S.C.D., Abdul Latiff Z., Lee C.C., Teh K.H., Mohd Sidik S. Parents of children with cancer require health literacy support to meet their information needs. Health Inf Libr J. 2023 doi: 10.1111/hir.12491. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Department of Statistics Malaysia ICT use and access by individuals and households survey report 2021. 2022. https://www.dosm.gov.my/portal-main/release-content/ict-use-and-access-by-individuals-and-households-survey-report-malaysia-2021

- 27.Teplinsky E., Ponce S., Drake E., et al. Online medical misinformation in cancer: distinguishing fact from fiction. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:584–589. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson J.S., Swire-Thompson B., Johnson S.B. What is the alternative? Responding strategically to cancer misinformation. Future Oncol. 2020;16(25):1883–1888. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan C.E., Lau S.C.D., Latiff Z.A., Lee C.C., Teh K.H., Sidik S.M. Information needs of Malaysian parents of children with cancer: a qualitative study. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2022;9(3):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.apjon.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richey R.C., Klein J.D. Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology. Springer New York; New York, NY: 2014. Design and development research; pp. 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan C.E., Lau S.C.D., Tan K.A., et al. Development and validation of a caregiving knowledge questionnaire for parents of pediatric leukemia and lymphoma patients in Malaysia. Cureus. 2022;14(10) doi: 10.7759/cureus.30903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osterwalder A., Pigneur Y., Bernarda G., Smith A. Wiley; 2015. Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kassam-Adams N., Marsac M.L., Kohser K.L., Kenardy J.A., March S., Winston F.K. A new method for assessing content validity in model-based creation and iteration of eHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(4):e95. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Candelaria Martínez M., Franco-Paredes K., Díaz-Reséndiz F.J., Camacho-Ruiz E.J. Content validity of a psychological e-health program of self-control and motivation for adults with excess weight. Clin Obes. 2022;12(5) doi: 10.1111/cob.12530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau X.C., Wong Y.L., Wong J.E., et al. Development and validation of a physical activity educational module for overweight and obese adolescents: CERGAS programme. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019;16(9):1–16. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Syahirah S.I., Rahmad S., Mohd I., Teng F. Development and validation of website on nutrition for premature baby. Malaysian J Med Health Sci. 2020;16(4):218–225. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polit D.F., Beck C.T., Owen S.V. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(4):459–467. doi: 10.1002/nur.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira PC de, Cunha CJC de A., Nakayama M.K. Learning Management Systems (LMS) and e-learning management: an integrative review and research agenda. J Inf Sys Technol Manag. 2016;13(2):157–180. doi: 10.4301/S1807-17752016000200001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xperiencify Xperiencify, the best gamified online course platform. 2022. https://xperiencify.com

- 40.Turner-McGrievy G.M., Hales S.B., Schoffman D.E., et al. Choosing between responsive-design websites versus mobile apps for your mobile behavioral intervention: presenting four case studies. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(2):224–232. doi: 10.1007/s13142-016-0448-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elling S., Lentz L., de Jong M. In: Electronic Government EGOV 2007 Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Wimmer M.A., Scholl J., Gronlund A., editors. Springer; Berlin: 2007. Website evaluation questionnaire: development of a research-based tool for evaluating informational websites; pp. 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elling S., Lentz L., de Jong M., van den Bergh H. Measuring the quality of governmental websites in a controlled versus an online setting with the “Website Evaluation Questionnaire.”. Govern Inf Q. 2012;29(3):383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2011.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodgers C., Bertini V., Conway M.A., et al. A standardized education checklist for parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer: a report from the children's oncology group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2018;35(4):235–246. doi: 10.1177/1043454218764889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clarke J.N., Fletcher P. Communication issues faced by parents who have a child diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2003;20(4):175–191. doi: 10.1177/1043454203254040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farooqui M., Hassali M.A., Abdul Shatar A.K., et al. Complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) disclosure to the health care providers: a qualitative insight from Malaysian cancer patients. Compl Ther Clin Pract. 2012 Nov;18(4):252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamidah A., Rustam Z.A., Tamil A.M., Zarina L.A., Zulkifli Z.S., Jamal R. Prevalence and parental perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine use by children with cancer in a multi-ethnic Southeast Asian population. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(1):70–74. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nielsen J., Loranger H. Prioritizing Web Usability. New Riders; Berkeley, CA: 2006. What is usability. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sigurdardottir A.O., Svavarsdottir E.K., Rayens M.K., Gokun Y. The impact of a web-based educational and support intervention on parents' perception of their children's cancer quality of life: an exploratory study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2014;31(3):154–165. doi: 10.1177/1043454213515334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landier W., Campos Gonzalez P.D., Henneberg H., et al. Children's Oncology Group KidsCare smartphone application for parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023;70(6) doi: 10.1002/pbc.30288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Díaz-Oreiro I., López G., Quesada L., Guerrero L. 13th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Ambient Intelligence UCAmI 2019. MDPI; Basel Switzerland: 2019. Standardized questionnaires for user experience evaluation: a systematic literature review; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, CET. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions their information could compromise the privacy of research participants.