Abstract

Waste segregation at source, particularly at the household level, is an integral component of sustainable solid waste management, which is a critical public health issue. Although multiple interventions have been published, often with contradictory findings, few authors have conducted a comprehensive systematic synthesis of the published literature. Therefore, we undertook a systematic review to synthesize all published interventions conducted in any country in the world which targeted household-level waste segregation with or without additional focus on recycling or composting.

Following PRISMA guidelines, Web of Science, Medline, Global Health, and Google Scholar were searched using a search strategy created by combining the keywords ‘Waste’, ‘Segregation’, and ‘Household’. Two-stage blinded screening and consensus-based conflict resolution were done, followed by quality assessment, data extraction, and narrative synthesis.

8555 articles were identified through the database searches and an additional 196 through grey literature and citation searching. After excluding 2229 duplicates and screening title abstracts of 6522 articles, 283 full texts were reviewed, and 78 publications reporting 82 intervention studies were included in the data synthesis.

High methodological heterogeneity was seen, excluding the possibility of a meta-analysis. Most (n = 60) of the interventions were conducted in high-income countries. Interventions mainly focused on information provision. However, differences in the content of information communicated and mode of delivery have not been extensively studied. Finally, our review showed that the comparison of informational interventions with provision of incentives and infrastructural modifications needs to be explored in-depth. Future studies should address these gaps and, after conducting sufficient formative research, should aim to design their interventions following the principles of behaviour change.

Keywords: Solid waste, Waste management, Waste segregation, Household, Intervention, Systematic review

Highlights

-

•

Systematic review of 82 household waste segregation interventions.

-

•

High heterogeneity in waste segregation processes, assessment methods and reporting.

-

•

Information communication is the most common intervention strategy reported.

-

•

Paucity of research on household waste segregation interventions in low- and middle-income countries.

-

•

Need for studies comparing effectiveness of individual intervention strategies.

1. Introduction

Solid waste management (SWM) is a serious global concern [1]. Its importance is driven by increases in the amount and complexity of generated waste, side by side with economic development, which together pose a severe threat to human health and sustainability of the ecosystem [2]. In 2016, about two billion metric tonnes of solid waste was generated globally, and approximately 34% came from high-income countries [1,3]. Improper waste management, in the form of uncontrolled landfilling and burning, can cause severe health consequences to people residing nearby [4], such as reproductive and birth disorders, cancers, skin allergies, respiratory disorders, and infectious diseases [5]. Mixed waste which includes hazardous waste can be dangerous to sanitary workers and households [4]. Accumulated waste is an ideal breeding site for disease-carrying vectors and micro-organisms, which increases the risk of infectious diseases such as cholera, plague, dengue and typhoid [6].

The average amount of waste produced globally is projected to increase by 70% (from 2.01 billion metric tonnes in 2016 to 3.40 billion metric tonnes in 2050) with maximal contribution expected from low-income countries (LICs), lower-middle-income countries (LMICs), and upper-middle-income countries (UMICs). LICs, LMICs and UMICs are together expected to account for at least 40% of the waste increase, whereas high-income countries (HICs) are expected to account for 19% [1]. Such increase in waste generation will create an enormous economic burden for low- and middle-income countries which currently spend 20% and 10%, respectively, of their municipal budget on solid waste management in contrast to only 4% in HICs with already well-developed waste management infrastructure [1]. While HICs have had much success in maintaining a sustainable waste management system [7], solid waste in low- and middle-income countries are often mismanaged [8] due to an ineffective waste collection and treatment system [9]. Therefore, the development of an effective SWM system is of utmost importance in low- and middle-income countries, especially because SWM serves a crucial role in achieving sustainable development [10] being intricately linked with all 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) [11].

Waste segregation/separation at source, defined as “the process of separating the different fractions of waste at the place where it is generated” [12], is now acknowledged to be an integral component of sustainable SWM [7]. In limited resource settings the advantages of waste segregation are manifold, especially from an economic perspective [13]. Another advantage in resource poor settings is that the majority of the generated solid waste consists of organic matter [7,14] which, if segregated at source, can be a valuable resource in composting for manure and biogas production [14]. Disposal of organic waste through traditional SWM methods, such as landfill, can pose a threat to the environment through the high greenhouse gas emissions from the anaerobic digestion of bio-waste [15,16] and soil pollution through leaching [15]. Similarly, burning of organic waste is limited by their high moisture content [17]. These points demonstrate the necessity of appropriate source segregation and sorting of generated waste in limiting the volume of waste being sent for landfilling or incineration, and highlight the benefits in terms of resource recovery [18].

Household waste (i.e., waste generated during day-to-day household work) is one of the main components of municipal solid waste and a large proportion of municipal waste management budgets is allocated to managing household waste [19]. Therefore, effective household-level waste management, through community participation in waste segregation at source, can result in sustainable SWM [20,21]. Household waste segregation at source would allow recyclable dry waste to be separated for use in resource recovery and wet organic waste to be diverted for composting and biogas production, ultimately leading to reduction in landfill load. One of the major challenges in this endeavour is the lack of public awareness, acceptance and consequent participation [7,22]. Many researchers are therefore focussing on developing successful SWM interventions targeting waste segregation-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviours at the household level [23,24]. Although multiple interventions have been previously published, few authors have conducted comprehensive and systematic synthesis of the literature to identify all interventions that target household waste segregation. Rather the focus of previously published systematic reviews has been on either waste recycling alone or composting. For example, Sewak et al. (2021) published a systematic review focussing on studies reporting household-level composting interventions [25]. Varotto and Spagnolli (2017) performed a meta-analysis on validated field intervention studies which investigated household recycling [26]. However, recycling of dry waste (i.e., conversion into valuable resource) and composting of wet organic waste is impossible without effective segregation of the generated waste [27]. A recently published meta-analysis of the factors influencing household involvement in waste sorting focussed only on observational studies [28]. To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review has synthesized all published interventions targeting household-level waste segregation while incorporating evidence related to both recycling and composting.

Considering the alarming increase in waste generation, there is, therefore, an urgent need to identify effective strategies to reduce, recycle, and manage household waste, which can significantly mitigate the detrimental impacts of landfilling and uncontrolled waste disposal on the environment and public health. Yet, despite the growing interest in waste segregation programs, a critical research gap exists, as previous studies have been fragmented and focused on narrow geographical areas, thereby lacking a comprehensive global perspective. This systematic review seeks to bridge this gap by synthesizing and critically evaluating the existing literature from diverse regions and contexts, offering a novel, overarching analysis of the most successful interventions and highlighting areas where further research is needed to develop innovative and context-specific solutions to this pressing global issue. Specifically, the research questions targeted in our systematic review include:

-

•

What are the types and characteristics of intervention strategies and their outcome assessment methods used to promote waste segregation at the household level?

-

•

What is the effect (including long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness) of strategies used by published intervention studies on waste segregation at the household level?

-

•

Is there any difference in intervention effect according to the types and characteristics of intervention strategies used?

-

•

What are the gaps in the current published literature regarding waste segregation interventions at the household level?

2. Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed while conducting this systematic review (see Appendix Table A1) [29]. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO prior to starting research (registration identification: CRD42021236710) [30].

2.1. Context and scope of the review

Waste segregation at source is defined in many different ways in published literature and is implemented using many different waste collection systems, such as kerbside/property close collection, bring or drop-off collection, etc. [31] Despite the numerous inter- and intra-country differences that exist in waste collection systems, usually the waste generated at household-level is collected through kerbside/property close collection, organised by the urban local bodies. The collected waste is then transferred for further processing to material recovery facilities and then to landfills for disposal. A separate bring/drop-off collection system is operational in some countries (especially HICs) targeting maximal recovery of recyclables [31]. In low- and middle-income countries recyclables are either collected (segregated or otherwise) along with residual waste through systems run by urban local bodies or are more often bought or collected by informal waste collectors [32].

For the purpose of this review, we considered interventions to be dealing with waste segregation if they focused on any or all of the following:

-

•

Separating generated household waste into categories, for example into dry waste (non-biodegradable, recyclable and combustible) and wet waste (biodegradable including food, agriculture, and dairy waste). Categorisation of waste, as published in literature, is highly variable. Therefore, so as to include the widest range of published waste segregation interventions, we did not limit the inclusion of studies based on the number and type of waste categories used.

-

•

Separate storage of different categories of waste (in suitable bins/bags) for kerbside/property close collection.

-

•

Subsequent use of separated waste, for example, taking dry recyclables to recycling stations/drop-off points and using wet waste for composting.

Determinants of household waste separation are commonly grouped into internal factors (including socioeconomic variables (such as age, gender, education, income, and marital status) and sociopsychological factors (such as moral obligation, perceived behaviour control, subjective norms, etc.)) [[33], [34], [35], [36]] and external factors (policy regulations in terms of information, incentive, and infrastructure) [37]. Many of the internal factors are not amenable to modification, such as the socioeconomic and demographic variables. The modifiable psychological internal factors have been shown by previous research to be affected by the external factors of information, incentive, and infrastructure [38]. Intervention strategies aiming to promote waste segregation at source can therefore target one or more of these three elements – infrastructure, information, and incentive. Accordingly, in this review, we have grouped the interventions based upon these three strategies and have allowed for the possibility of individual studies incorporating more than one strategy.

Further detailed exploration of these three possible intervention strategies has been done following theoretical frameworks and constructs published in the context of waste management, particularly the Motivation–Opportunity–Ability–Behaviour (MOAB) framework [12,39]. Accordingly, to achieve a change in waste segregation behaviour, motivation for waste segregation has been considered to be generated through both external and internal determinants. Previously, research has differentiated between the motivating influence caused by external factors, such as the provision of financial incentives (either through direct monetary payments or through indirect means such as provision of utility goods, coupons exchangeable for goods, gifts, etc.) and the development of internal persuasion through information communication [40,41]. Another important step in waste management should be aimed at creating opportunity for the change, through providing a conducive environment (i.e., infrastructural modifications) for better waste segregation. Details of infrastructural modifications employed by the included interventions were extracted in this review. Along with opportunity, ability is critical, which can be enhanced with appropriate and effective waste segregation information. Such informational strategies were analysed in detail from the papers reviewed.

Due to the complexity of potential informational strategies in waste segregation interventions, in our review we extracted details of information given and categorised it into the generic concepts of information provision (i.e., “what” (declarative) [42], “how” (procedural) [42], and “why” knowledge [43]) and more in-depth concepts of message framing or manipulation as used in persuasive communication (PC). PC (also called ‘steering’, ‘framing’ or ‘nudging’), defined here as the framing or manipulation of messages to influence the attitude or behaviour of participants while sharing “why” knowledge, has been used in behaviour change interventions [44,45] in the context of waste recycling [46] since the 1980s. Based on the Yale model of PC, we explore the characteristics of the source (communicators), message (information content and mode of delivery), and audience as important predictors of the persuasiveness of the communication [47]. Kelman (1958) [48] stated that the “authority, credibility and social attractiveness” displayed by communicators is a critical aspect of PC. This is also supported by the principle of “liking” proposed by Cialdini (2009) [49] which suggests that persuasive messages are more effective when delivered by communicators who are liked by participants based upon factors such as attitude [50], background (related to the concept of participatory communication through the use of community volunteers and block leaders) [51,52], physical appearance [53], attire [54], use of praise [55], and cooperation [56]. We reviewed included studies to identify reported source- or communicator-related factors.

We differentiated information message framing based upon the use of key persuasive message factors and/or the use of commitment [52]. The message factors considered in our review (Table 1) were selected based upon the principles of PC, as highlighted by Cialdini (2009) [49], Perloff (2020) [57], and Guerts et al. (2022) [44], and the factors influencing household waste segregation, as identified by Knickmeyer (2019) [43]. In terms of audience characteristics, as per the elaboration likelihood model (ELM) of persuasion [58] and its application in an intervention influencing travel behaviour [59], we assumed that targeted households would have a low level of personal involvement and information because the perceived benefits of waste segregation are not immediately apparent at personal level. Consequently, we expected that information studies would first engage participants in the intervention by using peripheral cues and simple decision-making rules (heuristics) and then guide participants to central cognitive processing of the PC facilitated by interactive communication, for example, feedback and repeated reminders. Therefore, we also extracted reported information on the use of feedback and prompts in informational interventions.

Table 1.

Categorisation of information message framing used in our review based upon the use of key persuasive communication principles.

| Persuasive message category | Message Content |

|---|---|

| Use of probability framing and biased presentation of information | Framing probabilities as gain versus loss/Framing probabilities in absolute terms versus in relative terms – Selectively highlighting the most relevant information and downplaying the negative impact or vice-versa [For example, to emphasize financial loss from inaction rather than savings due to action or to highlight scarce actions as being valuable] [42,57] |

| Use of logical evidence and authoritative framing | Evidence can be factual assertions or quantitative information from credible sources such as recommended guidelines. [42,55] Provided by authority figures who can be experts/community members expected to have previous experience- eyewitness statements, testimonials, etc. [42,47,55] |

| Use of narrative framing | Stories and/or graphic images with an educational message that can transport audience to different psychological places [55] |

| Use of normative framing | Social norms [“rules and standards that are understood by members of a group, and that guide or constrain social behaviours without the force of law” [58] and are related to perceived social pressure to engage or not engage in specific behaviors [59]/Subjective norms.]- activated by providing social proof/validation [60] (i.e., by showing that social peers comply with proposed attitude/belief/behaviour) or by promoting the targeted behaviour through community members/block leaders/volunteers [61]; Personal norms [62] [“individuals' perception of their own moral obligations to perform a certain behaviour”] - related to ascribed responsibility/civic duty and environmental attitudes/ecological concerns. [41]; Perceived behavioural control- perceived control over opportunities and barriers to waste segregation behaviour- related to self-efficacy [63]/‘locus of control’ [64] (including the concepts of past-behaviour/habit; recycling competence), perceived convenience/effort including time, etc. [41,65] |

| Using emotional appeals | Dramatizing the evil and fear arousal/Guilt appeal/Focussing on positive emotions [42,55] |

| Reciprocation | Providing small unconditional amenities/gifts for “sunk cost” effect [66,67] before intervention (excluding interventions which specifically refer to such provision as ‘incentive’), showing concern for participants' problems and offering relevant solutions (Empathy-inducing framing) [42,47] |

| Decisional control and commitment–consistency mechanism | Allows participant to voluntarily decide compliance (with or without commitment- i.e., verbal/written declarations of intention- made in public or otherwise) which has higher probability of consistency/sustainable behaviour. Under this category, participants are often provided manipulative persuasive messages such as illusion of control (where there is none); one option implicitly taged along with another; small request followed by bigger (Foot-in-the-door technique - FITD); etc. [42,47] |

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The population–intervention–comparator–outcome (PICO) framework was used to define the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review (Table 2). For our review, the population was households, the intervention was those targeting change in waste segregation, the comparators were less relevant for this review, as we accepted studies without any control group, such as quasi-experimental studies, as well as those using specified control groups for comparison, and the outcome was quantitative change in household waste segregation behaviour/knowledge/attitude.

Table 2.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria defined for screening search results.

| PICO | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population (P) |

|

|

| Intervention (I) |

|

|

| Comparator (C) |

|

|

| Outcome (O) |

|

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

Based upon the defined scope of review and inclusion-exclusion criteria, the overall framework for this review involved waste segregation interventions consisting of information, incentive, and infrastructural modifications. The outcome variables considered included: 1) waste segregation related attitudes/intentions/beliefs, 2) participation in waste management schemes that require households to segregate their waste, 3) weight and volume of waste (total and segregated), 4) the number of waste bins of segregated versus residual waste, and 5) contamination (presence of wrong type of or incorrectly sorted waste)

2.3. Search strategy

Searches for relevant published studies were performed in several electronic databases: Web of Science (Clarivate analytics), Medline (Ovid), and Global Health (Ovid). To develop the search string, relevant key words were compiled based on previously published systematic reviews and through discussions with investigators with expertise in waste management research. A unique search string was developed for each database by combining key words in three fields, i.e., Waste, Segregation, and Household. Key words within each field were separated using the Boolean operator “OR” whereas the three fields were connected through the Boolean operator “AND”. We had no restrictions on date of publication, therefore all articles published before the date of search (22nd March 2021) were included. The detailed search strategy is described in Appendix Tables A2–4. Additional studies were identified through searches in Google Scholar, back and forth citation search, and manual screening of bibliographies of relevant reports and review articles identified through database searches.

2.4. Screening and selection of studies

All citations identified through the database searches were exported into Endnote (Version 20), a reference management software, to deduplicate the search results. This deduplicated collection of citations was then imported into Rayyan (http://rayyan.qcri.org), a freely available semi-automated application for collaborative screening of search results. The screening of reports was undertaken in a two-step manner, with the first step being to read only the title and abstract. Reports which were considered relevant were then further screened by reading through the full text. When the full text was not available online, corresponding authors were contacted.

For optimal division of the screening, while maintaining a bias-free approach, both screening steps were undertaken by three groups of investigators, with each group containing one investigator with expertise or previous experience in waste management research (KR, VD, MK) and the other team-member being well-versed in conducting systematic reviews (SA, KCS, TT). Both investigators in each group independently screened all reports assigned to them. Any differences of opinions were addressed through discussion among all investigators and a consensus decision was made. Efforts were undertaken to identify multiple reports from the same study and merge them to avoid inclusion of duplicate publications. When reports included data from more than one eligible intervention conducted on different population groups without any relevant comparison between the interventions, the individual interventions were considered as separate studies. Studies that were included after full-text screening went forward for data extraction and risk of bias assessment.

2.5. Data extraction and study quality assessment

Four investigators working in groups of two (SS and RS, YS and KK) extracted relevant data from the selected studies. Before the start of data extraction, the template of data extraction was developed and discussed among all investigators. Each investigator then worked independently in Microsoft Excel to extract relevant information pertaining to general characteristics (such as year of publication, name of journal/publisher, geographical region where intervention was conducted, etc.) along with details of the intervention and its outcomes. Any discrepancy between investigators was settled through the opinion of others in the team.

The same group of investigators independently assessed study quality i.e., the risk of bias inherent in the included studies, using the open-access Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools [60]. Since we included only intervention studies with quantitative measures, we used the tools specific for randomised trials and non-randomised trials/quasi-experimental. Each of these checklists contained varying numbers of questions suited for the specific study design and the score/rating for each question was between one mark (satisfactorily addresses the domain), 0.5 marks (unclear data) and zero marks (does not satisfactorily address the domain). The final rating of each study was then estimated through summing all of the relevant question scores and dividing the summed score by the number of relevant questions. Any disagreement between two investigators in the risk of bias rating was settled through consensus among the rest of the team.

2.6. Data synthesis

Meta-analysis to calculate pooled effect sizes could not be done in the current systematic review due to high heterogeneity of reported effect estimates and the diversity in control groups, intervention strategies and outcome assessment methodologies. Instead, a narrative synthesis of the included interventions has been reported using descriptive statistics following the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guidelines [61]. To start with, the general characteristics of included reports were analysed and described. The year-wise trend of publication of included reports and the details of publishers were depicted graphically. To explore the spatial distribution of selected interventions, study location was grouped using the financial classification (based on their gross domestic product) and region-wise categorisation of countries provided by the World Bank. Accordingly, study location was divided into high (HIC), upper middle (UMIC), lower middle (LMIC), and low (LIC) income countries as well as East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, North America, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. When studies did not mention the geographic location where the intervention was conducted, for purpose of analysis of spatial distribution, it was assumed to be same as the first/corresponding author's institutional affiliation.

Considering the heterogeneity in the intervention strategies used, to summarise the effect of the included interventions, the results were described separately for each of the main categories of strategies (information, incentive, and infrastructure) implemented. While no standardised metrics could be used to describe the findings, and a comparison of p-values could not be done, results were narratively synthesized in terms of vote counting based on the direction of effect. To do this, the proportion of studies using a specific intervention strategy resulting in a positive effect on household-level waste segregation were reported along with 95% confidence interval and the probability of such positive effect (from a binomial probability test). The results from this, categorised by study design, quality and the method of outcome assessment, were then graphically displayed using effect direction plots following published methodology [62,63].

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

Fig. 1 shows the details of screening and selection of studies in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. Searches of the electronic databases (Ovid MEDLINE (n = 2046); Ovid Global Health (n = 2741); Web of Science Core Collection (n = 3768)) yielded 8555 reports, of which 2206 were duplicates. After deduplication, the title and abstract of 6349 reports were screened and 6239 were excluded based on the pre-determined inclusion-exclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining 110 reports were then retrieved. Excluding four reports whose full text could not be obtained, second-stage screening of remaining 106 reports was conducted by reading through their full texts. Thirty-seven reports were found to be relevant and were thus included in the review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow-diagram depicting details of the screening and selection process, (This is a two-column fitting image).

The bibliographies of all included reports and relevant reviews were then screened to identify any potentially missed relevant reports. Google Scholar was searched to identify grey literature. An additional 196 reports were identified through the citation searching and from Google Scholar, of which 22 were duplicates. Excluding three reports, which could not be retrieved, 171 full texts were screened for eligibility and 41 reports which met the inclusion-exclusion criteria were included. Therefore, 78 reports were finally selected. Three of these reports (Jacobs et al. (1984) [64], Chong et al. (2014) [65], and Timlett and Williams (2008) [66]) included data from eight eligible interventions conducted on different study populations without any comparisons between the results of the individual interventions and are therefore, considered as separate studies. In contrast, two reports described results from a group of waste segregation interventions conducted on the same study population sequentially [67,68], which we considered to be one study. The results of 82 intervention studies published in 78 articles are therefore, reviewed in this manuscript.

3.2. General characteristics of included reports (n = 78)

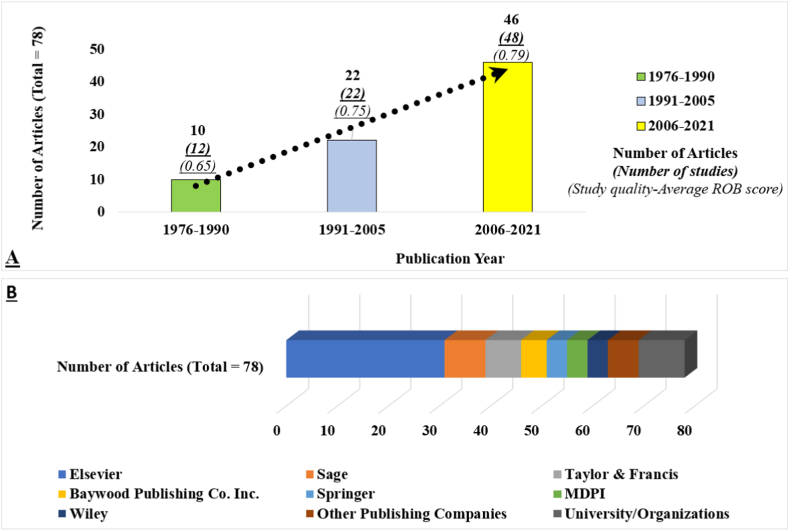

Seventy-eight reports published between 1976 and 2021 were included in the synthesis, of which 56 articles were published after the year 2000. The publication of waste segregation related interventions gradually increased over the years (Fig. 2A) with the highest number of reports published in the last tertile (2006–2021, n = 46). The majority (n = 74) of the included reports were peer-reviewed journal articles published by major publishing houses such as Elsevier (n = 31), Sage (n = 8), and Taylor and Francis (n = 7) (Fig. 2B). Only four grey literature reports i.e., thesis reports published by educational institutions [[69], [70], [71]] and a non-peer reviewed journal article [72] fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 2.

Overview of included articles – (A) Year-wise trend of publication (B) Number of articles categorised by their publishers, (This is a one-column fitting image). Note: The graph has been plotted considering the number of articles/reports published in the time period ranging from 1976 to 2021. This timeframe has been divided into tertiles for clarity in representation.

Since there were multiple reports of the same study and three reports included data from eight eligible interventions, the number of included studies (n = 82) is not the same as the number of included reports (n = 78). Thus, in the graph, the number of articles (topmost in bold) and studies (middle row in bold and italics) has been shown separately along with average risk of bias (ROB) score of the studies (lowermost in italics) in the data labels.

3.3. Quality of included studies (n = 82)

Assessing the quality of the included studies using the JBI critical appraisal tools yielded variable results. Forty-eight of the 82 included studies were classified as having high quality (score ≥ the average i.e., 0.76), of which 15 were randomised interventions and 33 were non-randomised interventions. Thirty-four studies scored below average (score <0.76), for reasons including ambiguous reporting of randomization, allocation concealment and blinding strategies in randomised trials, incomplete reporting of follow-up, and similarity between intervention and control groups in non-randomised trials. Furthermore, only a few studies accounted for potential confounding factors in their analyses [[73], [74], [75]]. Of the 34 low-scoring studies, most (n = 21) were conducted in the first two tertiles of publication year spread (i.e., 1976–1990 and 1991–2005) with only 13 having been published after 2006, showing a gradual improvement in study quality over time (Fig. 2A). There was no major difference in the average quality of studies conducted in HICs and UMICs versus LMICs and LICs.

3.4. Intervention location in included studies (n = 82)

The included studies (n = 82) varied greatly in the geographic locations where the interventions were conducted. Interventions were mostly conducted in countries where at least one of the authors were affiliated, except for in four studies [69,[76], [77], [78]]. Of these, two interventions were conducted in Indonesia [77] and Mozambique [78] by Japanese investigators as part of technical cooperation projects being run by the Japan International Cooperation Agency. Six studies failed to mention the geographic location where the intervention was conducted [46,73,[79], [80], [81], [82]]. As shown in Fig. 3 and Appendix Table A5, most of the studies were conducted in limited regions of the world, i.e., Europe and Central Asia (n = 30) and North America (n = 29) and in high-income countries (n = 60, 73%), especially in the United States of America (n = 25) and United Kingdom (n = 17). Among UMIC and LMIC countries, only China (n = 9), Peru (n = 2), Iran (n = 3) and India (n = 2) reported more than one intervention study. Only one study was conducted in a LIC (i.e., Mozambique).

Fig. 3.

Geographic distribution of included intervention studies classified according to study design

(This is a two-column fitting image).

3.5. Study population

The population units used in the intervention studies varied, with most studies (n = 66) enrolling households as their unit of studied population. The other 16 studies analysed the effect of their interventions on household clusters such as streets [66,81,[83], [84], [85]], residential building complexes or communities [67,68,82,[86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94]]. Although some studies [89,91] involving clusters did not mention the exact number of households covered, overall the included studies covered more than 213,601 households with the sample size ranging from 26 [71] to 64,284 [94] households. Studies mostly focused on households in urban areas (n = 61), followed by rural (n = 9) and sub-urban (n = 3) while three studies intervened in both cities and rural areas and six studies did not report such details. All studies targeted the adult population except one [93]. Maddox et al. (2011) reported the details of a waste management intervention designed and implemented by a local environmental charity organisation, which estimated the effect of educating school children and consequently student-led waste audits and other means of engaging with the wider community on household-level waste segregation and recycling [93].

3.6. Details of interventions

3.6.1. Type of intervention and use of control group

The majority (n = 55) of the studies employed a non-randomised intervention design, while the other 27 studies used randomization when assigning their intervention group. Most (n = 78) of the 82 studies used a control group either in the form of a separate control group, or self-control (pre-post experimental design) or both. However, three studies did not include a control group, neither separate nor self-control, and instead compared the outcome between groups provided with different types of interventions [64,85,89].

3.6.2. Formative research to design appropriate intervention

Of the 82 included interventions, only 34 studies conducted formative research to identify opportunities and barriers to household waste segregation in the local context and reported such determinants before designing and implementing their strategies. Most (n = 21) of these researchers developed their interventions based on findings from literature reviews of relevant studies conducted in their study area and/or quantitative data from local authorities. Few studies (n = 6) used stakeholder perspectives obtained through interviews or surveys to guide their intervention development and implementation. For example, Rousta et al. (2015 and 2016) used mixed-method interviews to understand the participants' needs and, based on stakeholders' opinions, the authors chose to intervene through information provision and decreasing the distance to waste collection points, since multiple interventions can potentially improve waste sorting [67,68]. Similarly, Krendl et al. (1992) [81], Hosono and Aoyagi (2017) [78] and Larson and Massetti-Miller (1984) [95] used households’ comments or interview data while McKay and Buck (2004) [96] and Manomaivibool et al. (2018) [97] worked in collaboration with participant households and local authorities to implement their interventions as per situational requirements. In contrast, seven studies relied upon their previous work or pilot studies conducted in the selected community [93,[98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103]].

3.6.3. Categories of waste for segregation

Included studies categorised waste for source segregation in a highly variable manner. Waste categories used in the interventions ranged from sorting into two groups of dry and wet waste up to 7–8 categories [86,104]. The broad categories of segregated waste commonly used by interventions, such as ‘recyclables’, ‘organic waste’, and ‘residual waste’, often included different waste products. For example, the organic waste category sometimes included only food waste [[67], [68], [69],96,97,99,100,103] but was often broader and studies included garden waste [22,70,102,[104], [105], [106], [107], [108]] under their definition of organic waste. Woodard et al. (2001) used a three-category system for segregation: organic, recyclables and residual. However quite a bit of overlap was found between the categories, with different types of food waste falling into either organic (fruit, vegetables, tea bags/coffee grounds) or residual waste group (cooked food waste, meat, fish, and bones) [105]. Similarly, the materials to be separated as recyclable versus residual waste was highly variable. The colour-coding of dustbins used for separated waste was also highly variable. For example the organic waste bin was usually coloured green [86,102,105,109] (except in the study by Marinela et al. (2018) [110] where it was brown) but green was also used to indicate the recyclables bin [110,111] or even the residual bin [112] (in place of other colours used, like black [105,110] or grey [102] or no colour [86] for residual bin).

3.6.4. Type of intervention strategies

The type of interventions implemented in the included studies are categorised into three main strategies: information communication, incentives, or infrastructural modifications (see Table 3, Table 4, Table 5). In some of the included studies (n = 18), there was an overlap between the intervention methods used, making it difficult to interpret which method was responsible for the observed effects.

Table 3.

Overview of 47 studies using only one type of intervention strategy (information communication, incentives, or infrastructural modifications).

Four main groups of outcome measures have been shown in the graph- KAP- Waste segregation knowledge/attitude/intention, Waste Audit- Waste weight/volume and/or Waste composition analysis/pick analysis, Participation- Participation in waste segregation/recycling/composting scheme/intervention (participant self-reported/author measured), and Other-request for compliance/diversion rate.

Effect direction is represented by the direction of the arrow: upward arrow ▲ = positive health impact, downward arrow ▼ = negative health impact, sideways arrow ◄► = no change/mixed effects/conflicting findings while X indicates that the said outcome was not measured by the study.

Size of the arrow shows the sample size of the study [Large arrow (Font size 20) - ▲ >300; medium arrow (Font size 14) ▲ 50–300; small arrow (Font size 8) ▲ <50.

Study quality is shown through colour of the cell: green = low risk of bias; amber = some concerns; red = high risk of bias and to classify into these groups, the risk of bias scores of individual studies were divided into tertiles.

This effect direction plot has been created following published methodology (Boon and Thomas 2021).

aStudy designs: N-nonrandomised; R-randomised; MA-Multi-arm/multiple interventions; C-controlled; NoC-non-controlled; CBA-controlled before-after; BA-non-controlled before-after.

Table 4.

Overview of 18 studies intervening through combination of information communication (A), incentives (B), or infrastructural modifications (C).

Three main groups of outcome measures (as relevant to the studies) have been shown in the graph- KAP- Waste segregation knowledge/attitude/intention, Waste Audit- Waste weight/volume and/or Waste composition analysis/pick analysis, Participation- Participation in waste segregation/recycling/composting scheme/intervention (participant self-reported/author measured).

Effect direction is represented by the direction of the arrow: upward arrow ▲ = positive health impact, downward arrow ▼ = negative health impact, sideways arrow ◄► = no change/mixed effects/conflicting findings while X indicates that the said outcome was not measured by the study.

Size of the arrow shows the sample size of the study [Large arrow (Font size 20) - ▲ >300; medium arrow (Font size 14) ▲ 50–300; small arrow (Font size 8) ▲ <50.

Study quality is shown through colour of the cell: green = low risk of bias; amber = some concerns; red = high risk of bias and to classify into these groups, the risk of bias scores of individual studies were divided into tertiles.

This effect direction plot has been created following published methodology (Boon and Thomas 2021).

aIntervention strategies used- AC + implies combination of information communication and infrastructural modifications; AB + means combination of information communication and incentives; ABC + all three strategies combined.

bStudy designs: N-nonrandomised; R-randomised; MA-Multi-arm/multiple interventions; C-controlled; NoC-non-controlled; CBA-controlled before-after; BA-non-controlled before-after.

Table 5.

Overview of 17 studies comparing different intervention strategies [information communication (A), incentives (B), or infrastructural modifications (C)].

Three main groups of outcome measures (as relevant to the studies) have been shown in the graph- KAP- Waste segregation knowledge/attitude/intention, Waste Audit- Waste weight/volume and/or Waste composition analysis/pick analysis, Participation- Participation in waste segregation/recycling/composting scheme/intervention (participant self-reported/author measured).

Comparison of effect among intervention strategies is represented by “>”- greater effect and “ = ” implying no difference in effect.

Study quality is shown through colour of the cell: green = low risk of bias; amber = some concerns; red = high risk of bias and to classify into these groups, the risk of bias scores of individual studies were divided into tertiles.

aStudy designs: N-nonrandomised; R-randomised; MA-Multi-arm/multiple interventions; C-controlled; NoC-non-controlled; CBA-controlled before-after; BA-non-controlled before-after; A-information communication, B-provision of incentives, C-infrastructural modifications; “+”- when strategies are combined-for example AB + implies combination of information and incentives.

3.6.4.1. Information as an intervention strategy

Information communication was used as a method of intervention in 77 studies, of which 43 used only information strategies. Of the other 34 studies, information strategy was combined with other strategies (n = 18) or comparisons were made between information versus incentive (n = 5) [75,79,[113], [114], [115]], information versus infrastructure (n = 9) [64,65,67,68,77,82,98,105,107] or both (n = 2) [78,116]. The method of information communication was highly heterogeneous in the included studies. The variations occurred in terms of:

-

(i)

Characteristics of communicator

The studies did not generally report details of the communicator used to make information communication more persuasive, except regarding the communicator background and the effect this may have on his/her authority or credibility. For example, in eight studies, researchers alone approached the targeted community for the intervention [67,68,74,85,89,[117], [118], [119], [120]]. Involvement of local authorities (government or private) was reported in 20 studies [65,70,71,95,97,98,102,105,[107], [108], [109], [110],112,[121], [122], [123], [124]]. Different volunteers were engaged in studies including residents (15 studies) of the targeted community (for example, block leaders) [69,72,75,77,87,88,91,100,103,106,115,[125], [126], [127], [128]], students from local educational institutions (13 studies) [46,69,72,80,82,93,100,113,[129], [130], [131], [132], [133]] or non-community staff/volunteers specifically employed for the intervention implementation either by the researchers or local agencies (13 studies) [66,76,78,81,83,84,94,99,103,114,134].

-

(ii)

Mode of information delivery/communication strategy

Within the 77 informational interventions, the method of information delivery varied from verbal information delivered by face-to-face interaction alone (n = 11) [71,75,77,82,97,115,129,131,[135], [136], [137]], only written information in the form of pamphlets/brochures/fliers/doors/hangers/dustbin/ stickers/wall /posters/magnets etc. (n = 25) [[64], [65], [66],70,72,79,80,84,86,98,101,104,107,108,112,[116], [117], [118],121,134,138,139] or a combination (n = 41) of these two methods. Fifteen studies used additional methods such as online interfaces, telephone/mobile phoning, and radio/television-based platforms for delivery of information and/or clarification of queries. Most studies communicated the information through doorstep canvassing (n = 42), whereas in the other studies written information was either mailed or sent in newsletters or verbal information was provided during community meetings/gatherings, public demonstrations/roadshows, and training programs.

-

(iii)

Content of information

Most (n = 66) of the informational interventions included a combination of information on “what” is waste segregation/recycling/composting (declarative knowledge) and details on “how” to do the process (procedural knowledge). Milford et al. (2015) [70] provided procedural knowledge to only a subgroup (advice group) with feedback information to all participants and identified the effect of provision of procedural knowledge. Nine studies did not report details about their provision of “what” and “how” information but described the “why” information provided while two studies did not elaborate any details regarding the content of information. In addition to providing generic information, 59 studies used specifically framed messages/nudges to explain “why” waste segregation is needed and/or its benefits to influence the participants in the form of PC (Appendix Table A6). The most commonly used methods of PC were normative framing (n = 39), evidence and authoritative framing (n = 26), and reciprocation (n = 24).

-

(iv)

Feedback and repeated reminders

Nineteen studies provided information in form of tailored feedback [22,[66], [67], [68],70,72,77,84,87,102,103,107,112,118,122,123,130,134,139]. For example, in the studies reported by Xu et al. (2016) [103] and Murase et al. (2017) [77], volunteers provided personalised individual feedback to participants by observing their actual behaviour of waste segregation and disposal while Perrin and Barton (2001) [112] distributed feedback leaflets to participating households. In contrast, some studies provided their participants comparative feedback on their performance contrasted with that of their neighbours or other participants in their street/district [70,72,84,107,114,123,130,139]. Finally, a few studies such as Schultz (1999) [134] and De Young et al. (1995) [87] also compared the effect of individual feedback (aimed at activating personal norms) with that of social comparative feedback (activating descriptive/social norm). Mertens and Schultz (2021) went on to compare feedback on immediate neighbours versus that of other residents in the neighbourhood, others in the state or those with best performance [118].

Many studies (n = 26) focussed on provision of prompts/reminders. Sixteen studies [46,[65], [66], [67], [68], [69],78,86,88,94,100,103,106,107,112,122,137] used stickers/signage/magnets on walls, refrigerators, and dustbins as the source of simple and visible information to act as reminders to any passer-by and as an easily available source of information for theresidents (i.e., when they sort the waste). Seven studies provided written reminders either in form of notices/handbills (n = 5) [64,85,116,127] or as mobile messages (n = 2) [65]. Four studies [74,81,82,87] verbally communicated the reminders/prompts.

3.6.4.2. Incentive as intervention strategy

Fourteen studies provided incentives out of the total 82 included studies [66,73,75,78,79,104,106,111,[113], [114], [115], [116],138,140]. Of these, two studies [73,140] only dealt with incentive provision, five studies combined incentives with either solely information (n = 4) [66,104,115,138] or both information and infrastructural changes (n = 1) [106], and seven studies compared incentives with information (n = 4) [75,79,113,114], infrastructural changes (n = 1) [111] or both (n = 2) [78,116]. A variety of incentives were given by the studies. Three studies [114,116,140] provided direct payment with the amount ranging from one penny per pound of waste segregated and recycled up to five USD. In contrast, eight studies [66,73,75,78,104,113,115,138] included the provision of vouchers/coupons/bonus points. The provided coupons differed in terms of goods that they can be exchanged for (goods in local shops such as grocery items or at the local recycling centre [73,75,78,104,115,138] or leisure vouchers e.g., vouchers for swimming [138]). Two studies [66,113] did not report the items that their distributed coupons could be exchanged for. The reported financial value of provided coupons also varied, for example, $0.00072 USD (converted from 0.005 RMB, Chinese yuan) [104], $0.00853 (converted from 2.65 MZN, Mozambican metical) [78], $0.02–0.04 for every pound of segregated recyclables [73], $0.30-$3.02 (converted from £0.25 to £2.5) [138], and $30.23 (converted from £25) [66]. Finally, three studies provided non-monetary goods such as toys (valued at $0.10 to $0.50) [111], compost bags [106], and gifts through a lottery system [79].

3.6.4.3. Infrastructural modification as intervention strategy

A total of 29 interventions targeted infrastructural modifications, of which only two studies [92,96] had no additional information/incentive strategies in their interventions. The other 27 studies either provided combined infrastructural and information (n = 14), all three strategies together (n = 1) [106] or compared the effects of infrastructural changes versus information (n = 9) [64,65,67,68,77,82,98,106,107,112], incentive (n = 1) [111] or both (n = 2) [78,116]. Studies incorporated one or more of five main infrastructural modifications including provision of dustbins/composters/bags, decreasing distance that needs to be traversed for segregated waste disposal, segregation categories of waste, change in the frequency of waste collection (n = 6), and other miscellaneous methods e.g., refurbishing waste collection areas (Appendix Table A7).

A total of 25 studies distributed dustbins, composters or bags, either alone or in combination with other infrastructural changes. Eight studies [64,65,78,97,98,126,137] looked at the effect of distributing free reusable dustbins/composters/bags (for use in households or community bins or both). In contrast, five studies [67,68,77,92,102,111] added another infrastructural modification component (i.e., distance) to the distribution of dustbins while two studies [82,96] went on to compare the effect of dustbin proximity versus dustbin provision alone. Four studies [91,107,109,110] provided dustbins in a manner as to facilitate segregation of waste into categories not being previously used. Another three studies [105,106,112] investigated the combined effect of dustbin provision and change in frequency of waste collection while two studies implemented a comprehensive infrastructural intervention including dustbin provision with modification of waste categories and change in either distance [86] or frequency of waste collection [108]. Xu et al. (2016) added an innovative component to dustbin distribution by refurbishing the waste collection site to make it more hygienic and therefore potentially influencing the residents to use it more frequently [103]. The size and characteristics (such as the colour coding, material of the bins, presence of a cover/lid, labelling, compartments, presence of wheel/hanging facility, and distribution of garbage bags) of provided containers were also highly variable and often not clearly reported (Appendix Table A7).

In addition, four other researchers chose not to distribute dustbins and focussed solely on distance and frequency of waste collection. Of those, Tran et al. (2020) [141] and Jacobs and Bailey (1982) [116] studied the effect of different frequencies of collection (i.e., weekly or fortnightly) whereas Jacobs et al. (1984, Experiment 2) [64] explored the difference in the effect of the same day versus different day collections of recyclables and residuals. Chen et al. (2017) [89] investigated the effect of different source separation categories.

3.7. Outcome measurement methodology

Although all studies aimed to improve household-level waste segregation, data extraction revealed that the included studies have used different outcome measures to target the said behaviour.

3.7.1. Waste segregation knowledge/attitude/intention and request compliance (n = 21)

Eighteen studies [69,70,76,79,80,80,85,86,93,95,100,101,104,113,127,133,135,136] measured knowledge and/or attitudes of participants using author-designed questionnaires. Three studies, Huntjens RC (2020) [71], Guéguen, N. (2010) [129], and Arbuthnot et al. (1977) [128], used a foot-in-the-door approach through an initial small survey on waste sorting behaviour to assess compliance of participants when requesting to separate fruit and vegetable waste, to record one month of waste sorting data, and their use of the city's recycling centre. Mee (2015) [122] reported “interest in recycling” and the number of visits to the recycling website which they considered indicators of attitude/intention.

3.7.2. Waste segregation behaviour (n = 77)

There was considerable heterogeneity in the methodology adopted to measure/monitor waste segregation behaviour, the reported outcome, as well as the categories of separated waste. For quantitative estimation of waste being segregated, studies used the following methods:

-

(i)

Participation in waste segregation/recycling/composting scheme/intervention (self-reported): Fourteen studies [73,75,76,78,82,95,107,111,115,119,122,123,128,136] used questionnaire-based self-reported measure of participation, of which only five studies [73,78,82,111,123] collected additional information through weighing waste or waste composition analysis [78,82,111,123] or triangulated the information through data collected from a local waste management agency [73] or monitoring by researchers [78].

-

(ii)

Participation in waste segregation/recycling/composting scheme/intervention (observed): Thirty-nine studies used various participation related measures for their outcome assessment. Outcomes reported in these studies varied from measuring change in the number of waste bins set-out for collection to recording the frequency of participation in ongoing/newly introduced waste segregation schemes. The definitions used for these outcome indicators by the studies were highly heterogeneous. For example, Willman (2015) [125] defined participation as “the total number of recycling bins counted each week within each of the neighbourhoods” whereas Chong et al. (2014) [65] included multiple indicators for participation such as “participates at any time” (turning in segregated residual waste at least once in the study period) and “participation ratio” (“number of times a household turned in residuals divided by number of opportunities to do so”) [65]. In contrast, Woodard et al. (2005) calculated the proportion of households which participated in recycling during the study period and those that set out recyclables on any given day [106].

-

(iii)

Waste weight/volume: Thirty-nine studies utilised waste audit as the method for their outcome assessment. Waste audits were conducted through one or more methods such as weighing of waste bins, counting the number of bins of known size and estimating the volume from size of bins. Weight or tonnage of set out segregated waste was measured by 33 studies. Four studies [125,130,134,139] counted the number of provided waste bins/bags (with known volume) that had been set out by the participating households while another three studies [116,121,140] estimated the volume of waste. For example, White et al. (2011) (Study 1) measured the height of waste bin using measuring stick and then went on to calculate the volume by using formulae for volume calculation of pyramid with rectangular base (assuming dimensions to follow the standardised bin) [121]. Some studies utilised the data on number of bins, volume, weight, etc. to define and calculate complex indices. For example, Willman (2015) [125] defined “recycling potential” to reflect the total of recyclables collected from a neighbourhood based on the number and volume of recycling bins and carts set out.

-

(iv)

Waste composition analysis/pick analysis: Multiple studies (n = 25) scrutinised the waste composition in addition with the aforementioned outcome variables. Waste composition has been reported in terms of categories of waste items (e.g., residual versus different types of recyclables versus biodegradable/food waste), weight/volume of each waste category and presence/absence/quantification of contamination. Three studies reported only the results of waste composition analysis. Rousta et al. (2015 and 2016) [67,68] reported the percentage of missorted waste while Chen et al. (2017) [89] defined two outcome variables: “accuracy rate as the ratio of a certain category of waste that is thrown into a corresponding waste container accurately” and “miscellany rate as the ratio of the waste that is thrown into the wrong category of waste container”. Zhuang et al. (2008) used composition analysis to define the “correct rate of separation of dry and wet waste” [91].

3.8. Effect of interventions on household waste segregation

The effect of the implemented interventions varied greatly. However, there was evidence that information, incentive, and infrastructural changes had an effect on waste segregation, with 72 of 82 studies resulting in a positive effect of the implemented interventions (88% (95% CI 81%–95%), p = 0.00). The summary of the effects of the intervention for each of the three main categories of strategies implemented and a comparison between the strategies is described in the following paragraphs (Table 3, Table 4, Table 5).

3.8.1. Effect of information-only interventions (n = 43)

3.8.1.1. Overall effects

Among the 43 studies which reported information-only interventions (Table 3), only six studies [65,66,87,95,99,139] failed to demonstrate any increase in waste segregation as a result of their intervention. Another eight of the 43 studies [66,69,70,85,100,123,125,134] reported inconclusive evidence as their written informational interventions resulted in positive effect on some outcome measures but negative or statistically insignificant changes on other outcomes. Of these 14 studies which do not report unequivocal positive effects of information-based interventions, four were randomised control trials (RCT) and the remaining ten studies used a non-randomised trial (NRT) design. Only two of these 14 studies used participant self-reported outcome measures alone and all of these 14 studies provided written PC with some studies (n = 9) adding a verbal component and/or doorstepping or volunteering. However, the persuasive component of the communication was highly variable among these studies, as were the outcomes assessed, hindering the drawing of any conclusions regarding ineffective or effective information characteristics. For example, Chong et al. (2014) (Participation study) [65] provided normative PC and reported that none of the nine different types of normative information led to any significant increase in participation rate when compared with the control group. In contrast, Lyas et al. (2004) [139] reported an overall decrease in both recyclables set out rate and the occurrence of contamination in both positive and negative emotion-based feedback groups and the control group (no feedback), with no significant between group difference. An example of inconclusive evidence is in the feedback intervention reported by Timlett and Williams (2008) [66], which significantly reduced contamination in disposed segregated recyclables, but the increase in recycling set out rates was not statistically significant.

Among the remaining 29 studies (RCT = 13, NRT = 16) which reported unequivocal positive effects of information-based interventions, most of the studies (n = 22) employed verbal modes of communication and incorporated doorstepping and/or volunteers (except for Sadeghi et al. (2020)) [135] who did not clearly mention details regarding the communicator and absence/presence of doorstepping). However, since 31% (n = 9) of these 29 studies used only participant self-reported outcome measures, such as their knowledge/attitude, compliance, or self-reported participation (as opposed to 14% (n = 2) of 14 non-positive studies), a non-ambiguous conclusion of higher effectiveness of verbal mode of information communication cannot be drawn.

3.8.1.2. Effect of individual strategies of information communication

In most of the included studies, the evaluation of the effectiveness of individual means of information communication was difficult because informational interventions were often conducted as broad campaigns with multiple simultaneous activities. An example of this is the study by Gordon (2013) [69] who conducted extensive information communication campaigns including radio broadcasts, written information sharing through leaflets, pictorial posters, blackboards, dustbin stickers, direct interactive verbal communication through trained volunteers standing near waste-bins, and door-steppers aided by block leaders. Although the intervention resulted in a statistically significant increase in the quantity of separated food waste and food waste capture rate, the effect of individual components of the intervention cannot be separated [69].

Of the 43 information-only studies in our review, only around half (n = 22) attempted to differentiate and evaluate between different informational strategies. Eight studies compared written versus verbal mode of informational intervention, of which three [81,87,99] found no difference while four [74,125,127,130] reported that providing additional verbal information, particularly when delivered by volunteers, improves intervention effectiveness. However, one study, Lin et al. (2016) [88], concluded that the content/characteristics of written information made a difference in the overall intervention effectiveness. The authors found that visually attractive written information, which can also act as a reminder/prompt, was equally as effective as volunteer-delivered verbal information and both of these were more effective than generic poster-based written information, which was the baseline situation in the study. Particularly, incorporation of written/signed commitment components increased the probability of a positive effect when compared with verbal commitment and generic leaflet-based written information, as reported by Pardini and Katzev (1983) [120]. Written commitment, furthermore, was found to have an equal effectiveness as other forms of written PC by Burn and Oskamp (1986) [46] and De Young et al. (1995) [87]. PC was compared with basic information by seven studies [71,87,88,118,129,134,139], of which only Lyas et al. (2004) [139] failed to find any difference. The most commonly compared persuasive technique was the use of normative feedback, which was found to be consistently better than generic information [87,118,134]. However very few studies compared different types of PC. Rhodes et al. (2014) [119] found no difference between four types of PC: information on depot recycling with pictures (narrative PC), messages on utility (gain-framed evidence-based PC), messages about affective benefits (emotional PC), planning-based procedural information (normative PC).

3.8.1.3. Moderation of informational intervention effectiveness by audience characteristics

Multiple audience characteristics modified the effectiveness of informational interventions. For example, participants with low past waste segregation behaviour were shown to be more influenced by the informational interventions than existing recyclers/segregators, as reported by Rhodes et al. (2014) [119] and Willman (2015) [125]. Similarly, Keller (1991) [72], Woodard (2005) [106], and Burn and Oskamp (1986) [46] showed significant effectiveness of information communication through doorstepping in low past waste segregation neighbourhoods, as opposed to the non-significant results reported in high baseline waste segregation regions by Cotterill et al. (2009) [83], Larson and Massetti-Miller (1984) [95], and Timlett and Williams (2008) [66]. Other audience characteristics that affected intervention success included socioeconomic and demographic variables. For example, Wadhera and Mishra (2018) found that lower income, larger household size, male gender and lower age reduced the probability of success of informational interventions with or without provision of incentives.

3.8.2. Effect of incentive-only and infrastructure-only interventions (n = 2)

Only four studies investigated the effects of infrastructure-only interventions (effect of reducing distance and provision of dustbins, DiGiacomo et al. (2017, Study 1) [92] and McKay and Buck (2004) [96]) and incentive-based interventions (introduction of pricing schemes, Fullerton and Kinnaman (1996) [140], and voucher-based incentives, Allen et al. (1993) [73]) (Table 3). Of these, the first three [92,96,140] reported significantly positive effects on the weight of segregated waste post-intervention while Allen et al. (1993) [73] found higher increase in participation rate in the intervention group (higher incentive, higher effect) compared to the control group. In addition, McKay and Buck (2004) reported that provision of backyard digesters was equally as effective as the more resource-intensive pickup and centralized composting system for segregation of wet waste [96].

3.8.3. Effect of combined (information, incentive and/or infrastructural modification) interventions (n = 18)

Table 4 shows the details of combined interventions. Three studies provided combined incentives (vouchers) and information (Guo et al. (2017) [104], Timlett and Williams (2008) (combined feedback and incentives intervention) [66], and Harder and Woodard (2007) [138]) all of which reported positive effects in waste audits conducted before and after the interventions. In addition, Guo et al. (2017) [104] also reported improvement in awareness regarding waste segregation while the latter two studies [66,138] also found increases in participation. Woodard et al. (2005) combined all three strategies (incentive (non-monetary goods), infrastructural modification (introduction of a scheme providing larger volume dustbins and changing the frequency of waste collection to alternate weekly between compostables and recyclables in first week followed by collection of residuals in the second week in place of the existing weekly residual and recyclables collection system) and information (written and verbal authoritative PC and reminders by doorstepping community volunteers)), which boosted participation rates to 84% (immediately after intervention) from 72% (baseline).

Combined infrastructural modification and information interventions were reported by 14 studies, of all which (except Amanidaz et al. (2019) [137]) reported increases in waste segregation outcomes. Amanidaz et al. (2019) provided flexible, waterproof, and washable bags with steel supports to act as dustbins for wet waste and found that source separation of waste remained relatively constant, although contamination of dry waste with wet waste reduced [137]. Similar reusable waste bags were also provided by Burn (1991) who found a significant increase in participation [126]. Manomaivibool et al. (2018) reported increases in acceptance and installation of composters [97] while eight of the other 11 studies which provided standard dustbins and/or a change in distance/frequency of waste collection, documented increases in separated waste weight and/or participation [64,86,91,102,103,[108], [109], [110]]. Finally, three studies (Chen et al. (2017) [89], Tran et al. (2020) [141], Jacobs et al. (1984, Experiment 2) [64]) successfully improved waste segregation through information communication combined with changes in waste categories and frequency of collection.

Six of these 18 combined interventions went on to compare a few of the incorporated strategies. For example, Harder and Woodard (2007) found that incentive vouchers that could be exchanged for leisure items were more effective than practical regular shop vouchers [138]. Infrastructural modification increasing convenience of waste segregation such as simpler categorisation [89,108] and convenient collection frequency [64,108] were found to be most effective.

3.8.4. Comparison of the effect of information versus incentive versus infrastructural modification (n = 17)

Only 17 of the included interventions directly compared the effectiveness of these three strategies (Table 5), of which two studies did not find any difference (Xu et al. (2018b) [75] (incentive = information) and Hosono and Aoyagi (2017) [78] (incentive = infrastructure = information)). Eight of 17 studies concluded that combining information with either incentives (n = 2) [22,113] or infrastructural modifications (n = 6) [64,67,68,77,82,105,112] improved the effectiveness of intervention. Bernstad (2014) [98], Geislar (2017) [107], and Chong et al. (2014, Participation intensity study) [65] found that infrastructural modifications were more effective than information provision through doorstep canvassing. However, financial incentives seem to be more effective, at least in the short-term, than infrastructural modification in terms of convenience/proximity to waste containers (Luyben and Bailey (1979) [111]) or weekly pickup facility (Jacobs and Bailey (1982) [116]) and information (Jacobs and Bailey (1982) [116], Xu et al. (2018a)). In contrast, Meneses and Palacio (2003) stated that using commitment-related PC through block leaders was more effective than the provision of incentives [79]. However, authors also stated that use of block leaders involved higher costs than provision of incentives in the form of non-monetary goods such as gifts (cost not mentioned) to participants selected through lottery [79]. Hence, the findings of the limited number of studies comparing the individual strategies were not conclusive.

3.8.5. Long-term and cost effectiveness

Twenty-eight studies included long-term follow-up to assess whether their interventions had any long-lasting/sustainable impact (Table 3, Table 4, Table 5). The follow-up duration varied from 2 to 4 weeks [113,114,119,120,125] to 18–19 months [99,102,128] with an average follow-up duration of 6.4 months in the 28 studies. Of these 28 studies, 16 reported declining long-term trends. All five studies reporting an incentive-related intervention, and which assessed long-term effectiveness, reported a decline in intervention's effectiveness [22,104,106,111,113]. In contrast, 50% of the 10 infrastructural interventions and 54% of 26 information-based interventions were not sustainable. Direct comparison of long-term effectiveness of different intervention strategies was reported by only two studies. Katzev and Pardini (1987) [113] showed that information interventions were more sustainable than incentive vouchers alone, while Luyben and Bailey (1979) [111] reported that the decline in intervention effectiveness was higher for non-monetary incentives than in the infrastructural modification (distance) group.

Few studies (n = 22) directly analysed the economic aspect of their interventions. Of these, four studies [79,88,102,111] reported the cost incurred during the implementation of intervention. Another 18 studies [[64], [65], [66],78,91,94,96,97,99,108,113,116,117,137,140] estimated the cost-effectiveness of their intervention comparing cost incurred versus the benefit obtained through sale of recyclables or redirection of total solid waste into landfills, of which four did not provide sufficient details. Timlett and Williams (2008) compared their three interventions and concluded that written information (feedback) was most cost-effective, followed by incentives and finally verbal information through doorstepping [66]. Similarly, higher cost-effectiveness of information interventions compared to incentive or infrastructure was reported Katzev and Pardini (1987), Hosono and Aoyagi (2017) and Jacobs and Bailey (1982) [78,113,116]. In contrast, Chong et al. (2015, Participation intensity study) found intensive prompting was not cost-effective unless combined with provision of dustbins [65] while Jacobs et al. (1984, Experiment 4) found combined information and incentive interventions most cost-effective [64]. Among informational interventions, written was invariably more cost-effective [66,99]. Zhuang et al. (2008) and Williams and Cole (2013) reported higher cost-effectiveness of convenient segregation categories and collection frequency, respectively [91,108].

4. Discussion

This systematic review highlighted the different intervention strategies published in literature which target the promotion of waste segregation at source. Considering the heterogeneity in the intervention strategies and outcome assessment methods used in the included 82 studies, we narratively synthesized the effects of included interventions. Although multiple interventions have been conducted globally, these studies are not equitably distributed around the globe, with the majority of the conducted interventions taking place in high income countries, particularly in Europe, North America, and Central and East Asia-Pacific regions. This review identified a paucity of high-quality interventions, particularly from low- and middle-income countries. This is a critical gap in published literature as the ever-increasing burden of waste generation [1], coupled with improper solid waste management, is an ongoing issue in low- and middle-income countries [8]. Evidence-based implementation of waste segregation at source is instrumental in tackling this public health issue. Despite the lack of field-based intervention studies which fulfilled the inclusion/exclusion criteria of our systematic review, recent publications from middle-income countries [142,143] have used modelling-based assessment to evaluate the effect of different socioeconomic and behavioural constructs on households’ waste segregation intention and behaviour, through questionnaire-based data collection. A review synthesizing the details of such choice experiments, simulations, and modelling-based studies adds to the existing evidence.