Key Points

Question

Is age stratification relevant for estimating the prevalence and burden associated with mental disorders and substance use disorders in the period from childhood to early adulthood?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study using data from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study, there was a high prevalence of mental disorders affecting children and youths, indicating that more than 1 of 10 (or 293 million) individuals aged 5 to 24 years globally live with a diagnosable mental disorder—in terms of burden, around one-fifth of all disease-related disability (considering all causes) was attributable to mental disorders among this population. Additionally, this age period encompasses about one-fourth of the mental disorder burden across the entire life course.

Meaning

Given the implications of the early onset and lifetime burden of mental and substance use disorders for policy making, age-disaggregated data are essential for a more accurate understanding of vulnerability and more effective prevention and intervention initiatives.

This cross-sectional study estimates the global prevalence and years lived with disability associated with mental disorders and substance use disorders across 4 age groups (age 5 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19, and 20 to 24 years) using data from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease.

Abstract

Importance

The period from childhood to early adulthood involves increased susceptibility to the onset of mental disorders, with implications for policy making that may be better appreciated by disaggregated analyses of narrow age groups.

Objective

To estimate the global prevalence and years lived with disability (YLDs) associated with mental disorders and substance use disorders (SUDs) across 4 age groups using data from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data from the 2019 GBD study were used for analysis of mental disorders and SUDs. Results were stratified by age group (age 5 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19, and 20 to 24 years) and sex. Data for the 2019 GBD study were collected up to 2018, and data were analyzed for this article from April 2022 to September 2023.

Exposure

Age 5 to 9 years, 10 to 14 years, 15 to 19 years, and 20 to 24 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prevalence rates with 95% uncertainty intervals (95% UIs) and number of YLDs.

Results

Globally in 2019, 293 million of 2516 million individuals aged 5 to 24 years had at least 1 mental disorder, and 31 million had an SUD. The mean prevalence was 11.63% for mental disorders and 1.22% for SUDs. For the narrower age groups, the prevalence of mental disorders was 6.80% (95% UI, 5.58-8.03) for those aged 5 to 9 years, 12.40% (95% UI, 10.62-14.59) for those aged 10 to 14 years, 13.96% (95% UI, 12.36-15.78) for those aged 15 to 19 years, and 13.63% (95% UI, 11.90-15.53) for those aged 20 to 24 years. The prevalence of each individual disorder also varied by age groups; sex-specific patterns varied to some extent by age. Mental disorders accounted for 31.14 million of 153.59 million YLDs (20.27% of YLDs from all causes). SUDs accounted for 4.30 million YLDs (2.80% of YLDs from all causes). Over the entire life course, 24.85% of all YLDs attributable to mental disorders were recorded before age 25 years.

Conclusions and Relevance

An analytical framework that relies on stratified age groups should be adopted for examination of mental disorders and SUDs from childhood to early adulthood. Given the implications of the early onset and lifetime burden of mental disorders and SUDs, age-disaggregated data are essential for the understanding of vulnerability and effective prevention and intervention initiatives.

Introduction

Since the first Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) results were published in the early 1990s,1,2 there has been increasing evidence that (1) mental disorders constitute a leading cause of disease-related burden worldwide and (2) the onset of mental disorders occurs in youth,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 with a peak around age 14 years.3 Considering the frequent chronicity of mental disorders, early onset can hinder transition into healthy adulthood and compromise a productive life thereafter. Mental disorders have been linked to high rates of school dropout, low economic productivity, incarceration, suicide, and homelessness,10 among other unfavorable outcomes impacting individuals, families, and society at large.11 Therefore, understanding the prevalence and burden of mental disorders in the first decades of life is essential for planning public policies, organizing services, and providing care across the entire life cycle.

The period spanning from childhood to the end of adolescence and early adulthood encompasses intense developmental changes10 that occur at fairly narrow intervals, associated with brain maturation, school entry, puberty, transition to the workforce, and variations in the social determinants of health.12,13,14 Researchers have argued that analyses of health information would require data disaggregation into shorter developmental intervals to reflect the fast pace of change.12,13 Concurrently, this view also supports an expansion of adolescence beyond 18 to 19 years and up to 24 years of age to account for the neurobiological and societal factors leading from adolescence to adulthood.13

An opportunity for a nuanced understanding of mental disorders affecting children and youth is provided by the GBD study.15 In addition to providing data grouped into 5-year brackets, the GBD study accounts for the chronic nature of mental illnesses by encompassing morbidity and disability as components to define burden.2 Nevertheless, only a few studies have taken advantage of these data to understand mental illness in children and youth globally.11,16 The GBD study also provides data on substance use disorders (SUDs), recognized as important cooccurring conditions in the context of mental disorders in young people.17 In the present report, we explore the most recent available data from the GBD study to estimate the global prevalence and nonfatal disability associated with mental and SUDs in children and youths across 4 developmentally distinct age groups: 5 to 9 years, 10 to 14 years, 15 to 19 years, and 20 to 24 years.

Methods

We estimated the prevalence and nonfatal disability associated with the following mental disorders categorized as level 3 causes according to GBD hierarchy (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1): anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, conduct disorder, depressive disorders, eating disorders, idiopathic developmental intellectual disability, schizophrenia, and a residual group of other mental disorders. Although SUDs are classified separately from mental disorders in the GBD hierarchy, to provide a comprehensive overview of mental disorders in line with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), the prevalence and nonfatal disability from alcohol and drug use disorders were also estimated. The definition and cataloging system codes (ICD-9, ICD-10, and DSM-IV-TR) to which each disorder is mapped appear in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. Ongoing GBD estimation follows the methodology outlined in the most recent GBD study, as detailed elsewhere; a summary is provided below.18,19,20,21

Prevalence

Prevalence estimates were modeled as described by the GBD 2019 Collaborators18,19 for male and female participants aged 5 to 9 years, 10 to 14 years, 15 to 19 years, and 20 to 24 years. To estimate prevalence, the GBD study derives epidemiological datasets from systematic reviews of published studies, searches of government and international organization websites, published reports, primary data sources, and contributions of data by GBD collaborators. The data obtained are adjusted for biases using DisMod-MR version 2.1, a tool that pools data from different sources to produce internally consistent estimates of prevalence by age, sex, location, and year.18,19 Details regarding bias correction and other adjustments performed for each individual disorder are available in the GBD 2019 capstone report18 and its Supplementary Appendix (page 1004 onwards) and also in the GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborator Study.19

Severity Proportions, Disability Weights, Cooccurring Conditions, and Years Lived With Disability

To assess nonfatal burden, the levels of disability or sequelae associated with each disorder (eg, mild, moderate, severe, or asymptomatic) are determined, with estimation of the prevalence of each sequela. After that, disability weights are assigned to each sequela. For disability weights, 0 implies full health and 1 implies death. eTable 2 in Supplement 1 shows sequelae, health status, and disability weights for mental disorders according to GBD methodology. Further details can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1 of the GBD 2019 study.18

Prevalence of sequelae and disability weights are used in a comorbidity correction procedure that simulates the cooccurrence of different diseases in each combination of location, age, sex, and year. This step considers the independent probability of having a combination of the sequelae covered in the 2019 GBD study. Despite the advantages of the comorbidity correction to prevent overestimation, well-known dependent cooccurring conditions22 are not considered, and prevalence estimation for combined disorders (such as mental disorders and SUDs) is not possible with the publicly available sets. As a result, mental disorders and SUDs are here presented separately, as merging these 2 categories would be contingent on reattributing comorbidity corrections, among other adjustments.

Once these steps are completed, nonfatal disability, expressed as years lived with disability (YLDs), is estimated by multiplying comorbidity-corrected prevalence estimates for each sequela by the corresponding disability weight (eTable 2 in Supplement 1) following the steps described elsewhere.19

Because the GBD study currently does not provide aggregate data on the 5- to 24-year-old group, we calculated the prevalence of mental disorders and SUDs for this broader age bracket as the mean of estimates for the age subgroups weighted by the corresponding world population in each subgroup.23 Details of data presentation are provided in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

Data Sources and Coverage

The number of sources in the GBD study providing data for each developmental stratum is as follows: 416 sources covering those aged 5 to 9 years, 827 sources covering those aged 10 to 14 years, 1611 sources covering those aged 15 to 19 years, and 1187 sources covering those aged 20 to 24 years. Notably, although most categories peak in the age 15 to 19 years bracket, this pattern is not homogeneous across diagnostic groups; for instance, data on autism are densest in the age 5 to 9 years range, and the highest concentration of sources on ADHD is in the age 10 to 14 years window (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Geographical heterogeneity in terms of density of data sources is also evident among the 159 countries with available data, as shown in eFigure 2 and eTable 5 in Supplement 1.

The University of Washington Institutional Review Board committee approved the 2019 GBD study, and the Ethics Committee at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre approved the current project. Informed consent was waived because deidentified data were used. The GBD study analyses adhere to the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) guidelines.24

Results

Prevalence

Globally in 2019, the reported mean prevalence of mental disorders in the age 5 to 24 years group was 11.63%—ie, 293 million of 2516 million children and youths aged 5 to 24 years had at least 1 diagnosable mental disorder—and more than 31 million (1.22%) had an SUD. Among investigated conditions, the highest prevalence in the overall group was recorded for anxiety disorders (84 million [3.35%]) and the lowest for schizophrenia (2 million [0.08%]). As expected, a marked difference was observed between the age subgroups for both individual (Figure 1) and the overall group of mental disorders, with the prevalence of mental disorders in the age 5 to 9 years group (6.81%; 95% UI, 5.58-8.03) estimated at approximately half that recorded for the age 20 to 24 years group (13.63%; 95% UI, 11.90-15.53) (Table). The steep increase in mood disorders across early to late adolescence is particularly striking.

Figure 1. Global Prevalence of Mental Disorders by Sex and Age Group From Age 5 to 24 Years.

Anxiety disorders included the combined estimate of all subtypes of International Classification of Diseases anxiety disorders; depressive disorders, major depressive disorder and dysthymia; eating disorders, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa; intellectual disability, idiopathic developmental intellectual disability, comprising intellectual disability from any unknown source after all other sources of intellectual disability are accounted for; and other mental disorders, residual category corresponding to an aggregate group of personality disorders. Data were not modeled by the Global Burden of Disease study before age 10 years for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, drug use disorders, and other mental disorders; for conduct disorder, only cases prior to age 18 years are modeled. For attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), no incidence is assumed in the Global Burden of Disease study from age 12 years onward.18,19 The dotted horizontal lines indicate the mean combined prevalence for female and male children and youth across all age strata. The shaded areas indicate 95% uncertainty intervals.

Table. Global Prevalence of Mental Disorders Among Children and Youthsa.

| Cause | Prevalence, % (95% UI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 5-9 y | Age 10-14 y | Age 15-19 y | Age 20-24 y | |

| All mental disorders | ||||

| Total | 6.81 (5.60-8.03) | 12.41 (10.57-14.45) | 13.96 (12.37-15.78) | 13.63 (11.91-15.53) |

| Female | 5.62 (4.60-6.46) | 11.24 (9.42-13.25) | 13.86 (12.11-15.85) | 14.53 (12.52–16.74) |

| Male | 7.92 (6.49-9.41) | 13.51 (11.57-15.72) | 14.06 (12.45-15.92) | 12.76 (11.23-14.58) |

| Anxiety disorders | ||||

| Total | 1.32 (0.86-1.87) | 3.35 (2.28-4.67) | 4.34 (3.23-5.70) | 4.58 (3.25-6.27) |

| Female | 1.62 (1.05-2.30) | 4.12 (2.85-5.73) | 5.39 (4.03-7.06) | 5.73 (4.09-7.79) |

| Male | 1.04 (0.68-1.48) | 2.62 (1.79-3.72) | 3.35 (2.48-4.42) | 3.46 (2.45-4.77) |

| ADHD | ||||

| Total | 2.14 (1.42-3.03) | 2.87 (1.93-4.02) | 2.26 (1.58-3.16) | 1.61 (1.15-2.34) |

| Female | 1.14 (0.76-1.63) | 1.54 (1.04-2.19) | 1.25 (0.86-1.76) | 0.91 (0.64-1.31) |

| Male | 3.08 (2.05-4.34) | 4.11 (2.77-5.73) | 3.23 (2.26-4.50) | 2.29 (1.63-3.35) |

| Autism spectrum disorder | ||||

| Total | 0.43 (0.35-0.51) | 0.41 (0.34-0.49) | 0.40 (0.33-0.47) | 0.38 (0.32-0.46) |

| Female | 0.21 (0.17-0.25) | 0.20 (0.16-0.24) | 0.19 (0.16-0.23) | 0.19 (0.15-0.23) |

| Male | 0.63 (0.52-0.74) | 0.61 (0.51-0.72) | 0.59 (0.49-0.70) | 0.57 (0.48-0.69) |

| Bipolar disorder | ||||

| Total | NA | 0.16 (0.11-0.23) | 0.58 (0.40-0.80) | 0.72 (0.52-0.96) |

| Female | NA | 0.17 (0.11-0.24) | 0.60 (0.42-0.83) | 0.75 (0.54-1.00) |

| Male | NA | 0.16 (0.10-0.23) | 0.56 (0.39-0.77) | 0.69 (0.49-0.91) |

| Conduct disorder | ||||

| Total | 1.02 (0.65-1.46) | 3.27 (2.28-4.43) | 2.00 (1.37-2.80) | NA |

| Female | 0.69 (0.41-1.02) | 2.44 (1.59-3.50) | 1.34 (0.85-2.06) | NA |

| Male | 1.34 (0.86-1.89) | 4.05 (2.91-5.36) | 2.63 (1.86-3.56) | NA |

| Depressive disorders | ||||

| Total | 0.08 (0.05-0.13) | 0.98 (0.65-1.37) | 2.69 (2.05-3.45) | 3.85 (2.96-4.91) |

| Female | 0.10 (0.06-0.16) | 1.26 (0.84-1.77) | 3.38 (2.58-4.35) | 4.69 (3.58-5.98) |

| Male | 0.06 (0.03-0.09) | 0.71 (0.47-1.00) | 2.02 (1.54-2.60) | 3.04 (2.32-3.90) |

| Eating disorders | ||||

| Total | 0.01 (0.01-0.01) | 0.10 (0.07-0.16) | 0.32 (0.21-0.49) | 0.42 (0.26-0.62) |

| Female | 0.01 (0.01-0.01) | 0.14 (0.09-0.20) | 0.44 (0.29-0.67) | 0.59 (0.38-0.84) |

| Male | 0.01 (0.01-0.01) | 0.08 (0.05-0.12) | 0.20 (0.13-0.32) | 0.26 (0.15-0.40) |

| Intellectual disability | ||||

| Total | 2.04 (1.29-2.80) | 2.01 (1.27-2.76) | 1.92 (1.21-2.65) | 1.76 (1.10-2.44) |

| Female | 2.01 (1.30-2.72) | 1.98 (1.29-2.69) | 1.89 (1.22-2.58) | 1.74 (1.12-2.38) |

| Male | 2.08 (1.29-2.87) | 2.03 (1.26-2.82) | 1.95 (1.20-2.71) | 1.79 (1.10-2.49) |

| Schizophrenia | ||||

| Total | NA | 0.01 (0-0.01) | 0.07 (0.04-0.10) | 0.24 (0.17-0.34) |

| Female | NA | 0.01 (0-0.01) | 0.06 (0.04-0.09) | 0.23 (0.16-0.31) |

| Male | NA | 0.01 (0-0.01) | 0.07 (0.05-0.11) | 0.26 (0.18-0.36) |

| Other mental disorders | ||||

| Total | NA | 0.06 (0.04-0.09) | 0.41 (0.25-0.60) | 1.01 (0.64-1.45) |

| Female | NA | 0.05 (0.03-0.07) | 0.31 (0.18-0.47) | 0.78 (0.46-1.14) |

| Male | NA | 0.07 (0.05-0.11) | 0.49 (0.31-0.72) | 1.23 (0.80-1.76) |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; NA, not applicable; UI, uncertainty interval.

Anxiety disorders included the combined estimate of all subtypes of International Classification of Diseases anxiety disorders; depressive disorders, major depressive disorder and dysthymia; eating disorders, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa; intellectual disability, idiopathic developmental intellectual disability, comprising intellectual disability from any unknown source after all other sources of intellectual disability are accounted for; and other mental disorders, residual category corresponding to an aggregate group of personality disorders. Data were not modeled by the Global Burden of Disease study before age 10 years for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, drug use disorders, and other mental disorders; for conduct disorder, only cases prior to age 18 years are modeled. For ADHD, no incidence is assumed in the Global Burden of Disease study from age 12 years onward.18,19

Sex-related differences were also evident for most disorders, and sex-specific patterns varied to some extent by age. Overall, there was a slight male preponderance of childhood mental disorders that shifted to a slight female excess at adolescence. Despite some overlap in 95% UIs at specific age strata, in general, male children and youths exhibited higher prevalence of autism spectrum, ADHD, and conduct disorders, whereas female children and youths had greater rates of anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and mood disorders that persisted across age groups. By contrast, there were more equal sex ratios for intellectual disability and schizophrenia.

Disability-Related Burden

In 2019, mental disorders constituted the leading cause of YLDs in people aged 5 to 24 years, accounting for 31.14 million YLDs. SUDs accounted for 4.30 million YLDs. A steep rise is observed as age increases, with the number of YLDs almost 5-fold higher in the age 20 to 24 years group compared with the age 5 to 9 years group (2 981 000 vs 13 907 000, respectively). Specifically for depressive disorders, 2.6-fold and 3.5-fold increases in the number of YLDs were observed in the age 15 to 19 years group (3 090 000) and age 20 to 24 years group (4 162 000), respectively, in relation to the age 10 to 14 years group (1 175 000). When the age 5 to 9 years group was compared with the age 20 to 24 years group, the number of YLDs from depressive disorders increased 35-fold (118 275 vs 4 162 000 YLDs, respectively). Figure 2 shows the number of YLDs attributable to each mental disorder for female and male children and youths in the age subgroups.

Figure 2. Years Lived With Disability (YLDs) From Mental and Substance Use Disorders, Age 5 to 24 Years.

Number of YLDs is age specific rather than cumulative, ie, YLDs from the older age groups do not incorporate the YLDs recorded for the younger age groups. Anxiety disorders included the combined estimate of all subtypes of International Classification of Diseases anxiety disorders; depressive disorders, major depressive disorder and dysthymia; eating disorders, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa; intellectual disability, idiopathic developmental intellectual disability, comprising intellectual disability from any unknown source after all other sources of intellectual disability are accounted for; and other mental disorders, residual category corresponding to an aggregate group of personality disorders. Data were not modeled by the Global Burden of Disease study before age 10 years for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, drug use disorders, and other mental disorders; for conduct disorder, only cases prior to age 18 years are modeled. For attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, no incidence is assumed in the Global Burden of Disease study from age 12 years onward.18,19

Share of Burden Attributable to Mental Disorders

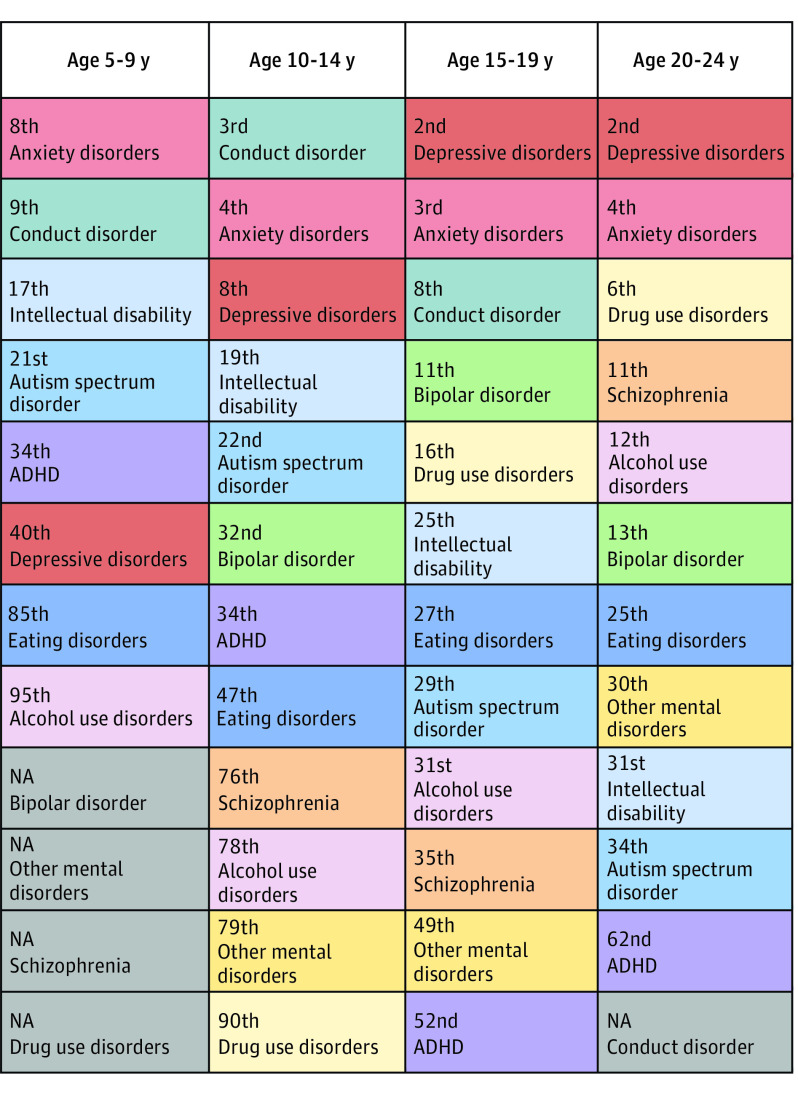

Figure 3 shows the ranking of mental disorders according to their contribution to nonfatal burden expressed as YLDs among all 2019 GBD study disorders in the age subgroups. In the age 5 to 9 years group, 2 mental disorders appeared among the top 10 sources of YLDs among all health conditions; for the age 10 to 14 years and age 15 to 19 years groups, 3 mental disorders appeared among the top 10 sources of YLDs; and for the age 20 to 24 years group, 2 mental disorder and 1 SUD appeared among the top 10 sources of YLDs. Considering all GBD conditions, mental disorders account for the highest disease burden among children and youth aged 5 to 24 years, being associated with 31.14 million of 153.59 million YLDs (20.27%) derived from all GBD disorders in this age group (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1).

Figure 3. Ranking of Mental Disorders and Substance Use Disorders According to Nonfatal Disability Expressed as Years Lived With Disability (YLDs) by Age Group, Both Sexes Combined.

In each age group, the column order reflects the rank within the group of mental disorders, while the number inside each cell reflects the overall rank among all causes within the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study. Gray cells marked with not applicable (NA) show disorders for which burden was not estimated within the age group. Anxiety disorders included the combined estimate of all subtypes of International Classification of Diseases anxiety disorders; depressive disorders, major depressive disorder and dysthymia; eating disorders, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa; intellectual disability, idiopathic developmental intellectual disability, comprising intellectual disability from any unknown source after all other sources of intellectual disability are accounted for; and other mental disorders, residual category corresponding to an aggregate group of personality disorders.18,19 ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Regarding the contribution of different conditions to the burden of disease over the life course, the distribution of the burden from mental disorders was remarkably high in childhood and adolescence compared with the pattern observed from other major causes, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, neoplasms, and unintentional injuries (Figure 4). On this broader life course perspective, of the total YLDs recorded for mental disorders across all GBD ages, 31.14 million of 125.29 million YLDs (24.85%) occur in the age 5 to 24 years range.

Figure 4. Proportion of Years Lived With Disability (YLDs) According to Age Group and Sex for Mental Disorders, Cardiovascular Disease, and Diabetes, Neoplasms, and Unintentional Injuries.

Female children and youth are shown to the left of 0 and male children and youth to the right of 0. Gray shading indicates age brackets of interest (age 5 to 9 years, 10 to 14 years, 15 to 19 years, and 20 to 24 years). Data were not modeled by the Global Burden of Disease study before age 10 years for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, drug use disorders, and other mental disorders; for conduct disorder, only cases prior to age 18 years are modeled. For attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, no incidence is assumed in the Global Burden of Disease study from age 12 years onward.

Discussion

The present study provides an overview of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with different mental disorders according to developmental stage and sex in children and youths. The aggregate estimated prevalence of mental disorders reported for individuals aged 5 to 24 years indicates that more than 1 in 10 (or 293 million) children and youths around the world live with at least 1 diagnosable mental disorder. This figure is in line with previous efforts to systematically review and summarize the global prevalence of mental disorders in youth,25 which estimated a prevalence of 13.4% in children and adolescents up to age 18 years. Here, we extend these findings by showing the marked differences across age-specific strata, with a doubling of overall prevalence between ages 5 to 9 years and 20 to 24 years. Differences in peaks and patterns are evidenced for the disorders considered here across developmental stages of childhood, early adolescence, late adolescence, and early adulthood.

As an important complement to the information regarding prevalence, we also showed that mental disorders were the leading cause of nonfatal disability in children and youths in 2019 (31.14 million YLDs), followed by neurological disorders (16.29 million YLDs) and skin and subcutaneous diseases (16.13 million YLDs) as distant second and third causes of nonfatal disability. Considering the share of disease burden, we found that the YLDs attributable to mental disorders represented 20.27% of all YLDs in the age 5 to 24 years group. Furthermore, the 31.14 million YLDs accounted for 24.85% of the 125.29 million YLDs associated with mental disorders over the life course, in sharp contrast to what is observed for other conditions, such as cardiovascular disease (1.82 million of 34.35 million YLDs [5.30%]), diabetes (1.43 million of 45.43 million YLDs [3.15%]), neoplasms (0.21 of 8.09 million YLDs [2.64%]), and injuries (4.59 million of 37.78 million YLDs [12.14%]).

Taken together, these data support the need for granular analyses across childhood and adolescence and the salience of mental disorders as chronic diseases of children, adolescents, and young adults. This concentration of disability burden at an early age raises concern about the potential lifetime impact of these conditions. Analyses of combined age subgroups (eg, 0 to 14 years, 10 to 24 years, or 0 to 18 years) may mask important trends that could be instrumental for care and prevention efforts. Furthermore, differences in sex-specific prevalences in these age strata highlight the importance of building in both age-specific and sex-specific patterns in planning of services.

Data presented here also demonstrate the importance of the age 5 to 24 years interval for grasping the disease-related burden associated with mental disorders, and therefore future GBD iterations should consider this period as a standard output. There are inherent challenges and complexities in establishing definitive age ranges, especially in the context of the continually evolving landscape of developmental and societal changes. The decision to set the upper age limit at 24 years is not only informed by prevailing literature13,14 but also by a comparison between the age bands of 20 to 24 years and 25 to 29 years, revealing that, with the potential exception of schizophrenia, prevalence estimates largely remain stable between these 2 periods.

Limitations

Despite presenting a comprehensive view of the prevalence and burden associated with mental disorders early in life, this report has several limitations. First, fewer data sources are available in less privileged regions and populations. Considering that more than 170 million children and youths aged 5 to 24 years live in areas without data sources in the 2019 GBD study, epidemiological studies focusing on standardized age groups are warranted. Further, no specific information is available for subgroups with higher vulnerability for mental illnesses, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, asexual, and intersex as well as indigenous youths.

One important consideration in interpreting results is the reliance on reports that used different types of informants across age groups for prevalence data; while some studies integrated parent reports and self-reports, others relied on parental reports for younger children and self-reports for adolescents and young adults. This approach mirrors the practical constraints and methodological norms in the field of child and adolescent mental health and offers the advantage of capturing age-specific perspectives that are most relevant in each developmental stage.25,26 Nevertheless, it also reflects the nuanced challenges of case identification in psychiatric epidemiology, as different informants may offer varying viewpoints.27 As we aim to provide a comprehensive and age-sensitive overview, readers should consider this informant variation as an additional layer of context when interpreting the findings and comparing prevalence estimates between age groups.

Additionally, it is prudent to interpret with skepticism the disability weights applied to developmental disorders, such as autism and intellectual disability, that appear to be underestimated, especially considering the profound impact these conditions can have on an individual’s life. It is also noteworthy that the same disability weights are used across all age groups, despite their derivation solely from surveys of adults. As previously stated,28 disability weights reflect social values, based on the preferences of specific subgroups of the general population or health professionals. In that sense, it should be expected that the characteristics of the people making the choices regarding the disability weights related to specific health states will impact these measures; the view of children and adolescents should not be assumed a priori to align with the view of working-age adults. At the same time, the scales or tasks used for describing the health states should ideally be adapted for different age (or other) groups. Although this is likely a complex procedure, it would be advantageous to consider a specific focus on children and adolescents for the derivation of disability weights in the future. Along these lines, despite recognizing the crucial importance of the first 5 years of life for the promotion of mental health and prevention of mental ill-health, we did not focus on the age 0 to 4 years subgroup due to the limited applicability of diagnostic categories—and disability weights—here assessed for this developmental stage.

Other methodological definitions adopted by the GBD study regarding mental disorders have been questioned,29 for example, the operational definition of conduct disorder as a condition limited to the period until age 18 years.30 In the present study, we observed an enduring contribution of conduct disorder even in those aged 15 to 19 years. In fact, the YLD burden attributable to conduct disorder in those aged 15 to 19 years is second only to that attributable to anxiety and depressive disorders. This highlights the need to assess conduct disorder in the age 20 to 24 years group and perhaps beyond. Further, while we recognize the evolving perspectives on the classification of intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder, we have maintained their inclusion in our study as mental disorders to align with the GBD framework. Also, while our study aligns with previous meta-analyses in terms of the overall prevalence of mental disorders, it is important to note that there are discrepancies in specific diagnostic categories, such as ADHD.31 These discrepancies could arise from various factors, including methodological choices in GBD estimates, or overrepresentation of specific age, sex, or geographical groups in individual studies. In addition, in contrast to the ICD,29 aggregation of SUDs as a separate level 2 condition in the 2019 GBD study is likely to result in underestimation of the burden of mental disorders. This should be reconsidered in the future, especially taking into account the shared demographic and risk and protective factors as well as prevention and care initiatives in those with mental disorders and/or SUDs. Furthermore, it should also be noted that GBD estimates do not include subthreshold manifestations of mental disorders, which are common in the children and adolescents and associated with disability and impairment.32

These limitations are further compounded by the lack of mortality data for mental disorders in the GBD study. As previously pointed out,19 mortality data are only available for eating disorders in the 2019 GBD study. As a result, for most mental disorders, disability-adjusted life years are exactly the same as the YLDs.33 Even though the contribution of nonfatal burden of disease provides important information beyond prevalence that is essential for decision-making in health, the lack of inclusion of mortality estimates from mental disorders may conceal the “true global disease burden of mental illness”34 and in fact is contradictory with the GBD core principles.2 Also noteworthy is the inability of GBD data to capture the link between suicide and mental disorders despite the available evidence showing a high proportion of suicide deaths attributed to mental disorders or SUDs.35 These methodological shortcomings support our focus on nonfatal disability expressed as YLDs.

None of the limitations described should be considered to detract from the GBD study, which has produced the best aggregate dataset of mental disorders globally to date and involves continued efforts to qualify and expand the data collected. Mental disorders as well as SUDs represent a tremendous challenge to individuals, families, and communities. Efforts to tackle this problem can be guided by epidemiology in terms of identifying vulnerable populations and prioritizing lines of action; knowledge on the prevalence and burden is essential for the organization of services and provision of care. An added value of the present results is the use of a pre–COVID-19 dataset, which may potentially serve as a baseline for understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children, adolescents, and young adults over the coming years.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the estimated prevalence and nonfatal disability from mental disorders and SUDs based on data from the 2019 GBD study indicates that mental health disorders deserve special attention in terms of prevention and intervention in the first decades of life and that one-fifth of the disease-related nonfatal burden in this age range is attributable to mental disorders. The findings further support the need for granular analyses of age, an instrumental approach to account for the moment-to-moment interactions shaping mental health and ill health across development.36

eFigure 1. GBD 2019 Cause Hierarchy for Mental and Substance Use Disorders

eFigure 2. Global Coverage of GBD 2019 Sources for Estimation of Mental Disorders and Substance Use Disorders in Individuals Aged 5 to 24 Years

eFigure 3. Proportion of Years Lived With Disability From Mental Disorders in Relation to Other Causes of Disease Burden Among Children and Youths

eTable 1. GBD 2019 Definitions and Cataloging Codes for Mental and Substance Use Disorders

eTable 2. GBD 2019 Sequelae, Health States, Health State Lay Descriptions, and Disability Weights for Mental Disorders

eTable 3. Details of Data Presentation

eTable 4. Number of GBD 2019 Sources for Mental Disorders and Substance Use According to Age and World Bank Country Income Group

eTable 5. Number of GBD Sources up to 1999 and Since 2000, by Age and World Region

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Jamison DT. The global burden of disease in 1990: summary results, sensitivity analysis and future directions. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72(3):495-509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJL. The Global Burden of Disease Study at 30 years. Nat Med. 2022;28(10):2019-2026. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01990-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):281-295. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations . The Power of 1.8 Billion: Adolescents, Youth and the Transformation of the Future. United Nations Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copeland W, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorders by young adulthood: a prospective cohort analysis from the Great Smoky Mountains Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(3):252-261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGorry PD, Mei C, Chanen A, Hodges C, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Killackey E. Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):61-76. doi: 10.1002/wps.20938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(12):947-957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baranne ML, Falissard B. Global burden of mental disorders among children aged 5-14 years. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12:19. doi: 10.1186/s13034-018-0225-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development Among Children and Youth . Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth: A National Agenda. National Academies Press; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erskine HE, Moffitt TE, Copeland WE, et al. A heavy burden on young minds: the global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychol Med. 2015;45(7):1551-1563. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2423-2478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(3):223-228. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz T, Strong KL, Cao B, et al. A call for standardised age-disaggregated health data. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(7):e436-e443. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00115-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . GBD protocol. Accessed September 10, 2023. https://www.healthdata.org/gbd/about/protocol

- 16.Piao J, Huang Y, Han C, et al. Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31(11):1827-1845. doi: 10.1007/s00787-022-02040-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institutes on Drug Abuse . Common Comorbidities with Substance Use Disorders Research Report. National Institutes on Drug Abuse; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators . Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204-1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137-150. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castelpietra G, Knudsen AKS, Agardh EE, et al. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in Europe, 1990-2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;16:100341. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amendola S. Burden of mental health and substance use disorders among Italian young people aged 10-24 years: results from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(4):683-694. doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02222-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Holtz Y, et al. Exploring comorbidity within mental disorders among a Danish national population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):259-270. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) population estimates 1950-2019. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/gbd-2019-population-estimates-1950-2019

- 24.Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. ; (The GATHER Working Group ). Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet. 2016;388(10062):e19-e23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(3):345-365. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angold A, Erkanli A, Copeland W, Goodman R, Fisher PW, Costello EJ. Psychiatric diagnostic interviews for children and adolescents: a comparative study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(5):506-517. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costello EJ, Burns BJ, Angold A, Leaf PJ. How can epidemiology improve mental health services for children and adolescents? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(6):1106-1114. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199311000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charalampous P, Polinder S, Wothge J, von der Lippe E, Haagsma JA. A systematic literature review of disability weights measurement studies: evolution of methodological choices. Arch Public Health. 2022;80(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s13690-022-00860-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vigo D, Jones L, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Burden of mental, neurological, substance use disorders and self-harm in North America: a comparative epidemiology of Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(2):87-98. doi: 10.1177/0706743719890169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erskine HE, Ferrari AJ, Polanczyk GV, et al. The global burden of conduct disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 2010. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(4):328-336. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cortese S, Song M, Farhat LC, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of ADHD from 1990 to 2019 across 204 countries: data, with critical re-analysis, from the Global Burden of Disease study. Mol Psychiatry. Published online September 8, 2023. doi: 10.1038/s41380-023-02228-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuijpers P, Vogelzangs N, Twisk J, Kleiboer A, Li J, Penninx BW. Differential mortality rates in major and subthreshold depression: meta-analysis of studies that measured both. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(1):22-27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171-178. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vigo D, Jones L, Atun R, Thornicroft G. The true global disease burden of mental illness: still elusive. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):98-100. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00002-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moitra M, Santomauro D, Degenhardt L, et al. Estimating the risk of suicide associated with mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;137:242-249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenberg L. Development as a unifying concept in psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;131:225-237. doi: 10.1192/bjp.131.3.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. GBD 2019 Cause Hierarchy for Mental and Substance Use Disorders

eFigure 2. Global Coverage of GBD 2019 Sources for Estimation of Mental Disorders and Substance Use Disorders in Individuals Aged 5 to 24 Years

eFigure 3. Proportion of Years Lived With Disability From Mental Disorders in Relation to Other Causes of Disease Burden Among Children and Youths

eTable 1. GBD 2019 Definitions and Cataloging Codes for Mental and Substance Use Disorders

eTable 2. GBD 2019 Sequelae, Health States, Health State Lay Descriptions, and Disability Weights for Mental Disorders

eTable 3. Details of Data Presentation

eTable 4. Number of GBD 2019 Sources for Mental Disorders and Substance Use According to Age and World Bank Country Income Group

eTable 5. Number of GBD Sources up to 1999 and Since 2000, by Age and World Region

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement