Abstract

Introducción.

La neurofobia se define como el miedo hacia la neurología que surge de la incapacidad para aplicar los conocimientos teóricos a situaciones clínicas prácticas. Este fenómeno parece no limitarse únicamente a estudiantes de medicina, pero no se dispone de estudios previos en el ámbito de urgencias. Este trabajo valora la percepción de conocimientos en las distintas patologías neurológicas urgentes por parte de médicos en formación y posibles motivos de neurofobia.

Material y métodos.

Se trata de un estudio transversal multicéntrico mediante encuestas autoadministradas a médicos en formación de todo el Servicio Aragonés de Salud. Se interrogó sobre su miedo a la neurología y otras especialidades médicas, posibles causas y percepción de conocimientos en patologías neurológicas en el servicio de urgencias.

Resultados.

Se obtuvieron 134 respuestas. El 27,6% (37) sufría neurofobia. La neurología fue la tercera disciplina que mayor interés despertó, pero se considera la de mayor dificultad. Las áreas en las que mayor seguridad mostraron fueron las cefaleas y la patología vascular. Donde mayor inseguridad existía fue en la neuromuscular, la neurooftalmología y la lesión medular aguda. En ninguna de las áreas hubo un porcentaje mayor del 50% que se sintiera seguro o muy seguro.

Conclusiones.

La neurofobia está presente entre los médicos en formación que desempeñan su labor en los servicios de urgencias. Su distribución depende del grado de exposición a los pacientes. Los neurólogos debemos desempeñar un papel activo en la formación de nuevos especialistas y promover la colaboración con los servicios de urgencias.

Palabras clave: Educación, Enseñanza, Neurofobia, Neurología, Residencia, Urgencias

Introducción

Hace casi tres décadas que el profesor Ralph F. Jozefowicz acuñó el término ‘neurofobia’ para referirse al miedo o rechazo que presentaban sus estudiantes de medicina hacia la neurología clínica, fundamentalmente asociado a la falta de capacidad de los alumnos para aplicar sus conocimientos teóricos en neurociencias [1]. Desde entonces, este concepto, no descrito en otras áreas de la medicina, ha sido corroborado por diversos autores, la mayoría en países de tradición anglosajona [2-6].

Algunos trabajos han observado que esta aversión hacia la neurología parece mantenerse entre médicos jóvenes, pero con algunas diferencias con respecto a la etapa del pregrado, y es un aspecto muy poco estudiado [2,3,7]. Si uno de los principales argumentos de este fenómeno es la incapacidad para aplicar los conocimientos teóricos en situaciones de práctica clínica diaria, las urgencias hospitalarias serían un entorno clave para estudiar la existencia de neurofobia en nuestro medio.

El objetivo principal de este trabajo es conocer si existe neurofobia entre los médicos en formación que realizan guardias de urgencias hospitalarias y describir sus causas. Además, analizamos la percepción que tienen los médicos internos residentes (MIR) de su actuación sobre los principales motivos de consultas neurológicas que se pueden encontrar en urgencias.

Materiales y métodos

Es un estudio transversal mediante encuestas autoadministradas entre octubre y diciembre de 2022 a MIR que estaban desarrollando su formación sanitaria especializada en el Servicio Aragonés de Salud. Para su inclusión, los MIR debían pertenecer a especialidades que realizasen en algún año de su formación guardias médicas en los servicios de urgencias hospitalarias.

Las encuestas se diseñaron mediante la plataforma Google Forms, basándonos en estudios previos adaptados a nuestro medio. El cuestionario consta de 22 preguntas. Las respuestas de formato Likert de 1 a 5 se dicotomizaron para su análisis en 1-2 o 4-5, según la pregunta. Definimos neurofobia como un nivel alto o muy alto de miedo o rechazo hacia la neurología y áreas afines (respuestas 4-5 en la escala Likert). Los formularios se remitieron por correo electrónico a las comisiones de docencia de cada uno de los ocho centros formadores del Servicio Aragonés de Salud. En Aragón, para el año 2022-2023 comenzaron su formación sanitaria especializada 251 MIR, teniendo una duración total la etapa formativa de cuatro o cinco años, según la especialidad. De acuerdo con el modelo formativo, distribuimos las especialidades en no hospitalarias –medicina de familia y comunitaria (MdF)– y hospitalarias (todas las demás).

Tabla.

Características de la muestra y distribución por años.

| Total (n = 134) | |

|---|---|

| Edad, M (RIC) | 28 (26-29) |

|

| |

| Contacto con enfermedades neurológicas, n (%) | 70 (52,2) |

|

| |

| Prácticas en neurología durante la etapa universitaria, n (%) | 74 (55,2) |

|

| |

| Rotación en neurología durante la residencia, n (%) | 58 (43,3) |

|

| |

| Miedo o rechazo a la neurología, n (%) | 37 (27,6) |

|

| |

| Año de especialidad, n (%) | |

|

| |

| Primer año | 29 (21,6) |

|

| |

| Segundo año | 47 (35,1) |

|

| |

| Tercer año | 28 (20,9) |

|

| |

| Cuarto año | 26 (19,4) |

|

| |

| Quinto año | 4 (3) |

|

| |

| Alma mater, n (%) | |

|

| |

| Universidad de Zaragoza | 71 (53) |

|

| |

| Otra universidad española | 55 (41) |

|

| |

| Universidad extranjera | 8 (6) |

M: media; RIC: rango intercuartílico.

Para el análisis descriptivo, las variables cualitativas se presentan mediante la distribución de frecuencias. En el caso de las variables cuantitativas se usaron indicadores de tendencia central (media o mediana) y de dispersión (desviación estándar o rango intercuartílico). Para el análisis inferencial se estableció como significancia estadística valores de p < 0,05 y se usaron las siguientes pruebas de contraste de hipótesis: χ2 o prueba exacta de Fisher para comparar proporciones cuando ambas variables fueran cualitativas; y, en el caso de que una de ellas fuera cuantitativa, t de Student o ANOVA en distribuciones normales, y U de Mann-Whitney o Kruskal-Wallis si seguían una distribución no normal.

Para el análisis estadístico se empleó R-Studio (versión R: 4.1.2) [8] con el paquete de R ‘tableone’. Las gráficas y tablas se realizaron mediante Microsoft Excel 365 (Microsoft) y con los paquetes de R ‘ggplot2’, ‘ggpubr’ y ‘likert’.

El estudio fue aprobado por el Comité de Ética de la Investigación de la Comunidad Autónoma de Aragón.

Resultados

Se recibió respuesta de 134 MIR distribuidos entre los ocho hospitales formadores de Aragón. Las especialidades de las que se obtuvieron mayor número de respuestas fueron MdF (63; 47%) y medicina interna (10; 7,5%). Los dos principales centros en responder fueron el Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet (58; 43,3%) y el Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa (37; 27,6%), únicos centros terciarios de la región. En la tabla se detallan las principales variables analizadas y la distribución por años.

La edad media de los encuestados fue de 28 años (rango intercuartílico: 26-29). Setenta residentes (52.2%) notificaron haber tenido un contacto estrecho con enfermedades neurológicas, bien en primera persona, bien a través del apoyo o cuidado de familiares o amigos cercanos. En cuanto a la formación en neurología, 74 (55,2%) respondieron haber realizado prácticas hospitalarias durante su etapa universitaria, mientras que 58 (43,3%) habían realizado un rotatorio específico en un servicio de neurología durante la residencia.

Treinta y siete encuestados (27,6%) sintieron un nivel alto o muy alto de miedo o rechazo hacia la neurología (neurofobia). No se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre la existencia de neurofobia y el centro donde se estudió la carrera de Medicina, la especialidad en la que se están formando o si los MIR trabajaban en un centro con guardia específica de neurología de 24 horas. Entre los que habían realizado una rotación específica en un servicio de neurología hubo menor proporción de neurofobia (el 22,4% frente al 34,5%), si bien esta diferencia no fue estadísticamente significativa (p = 0,174).

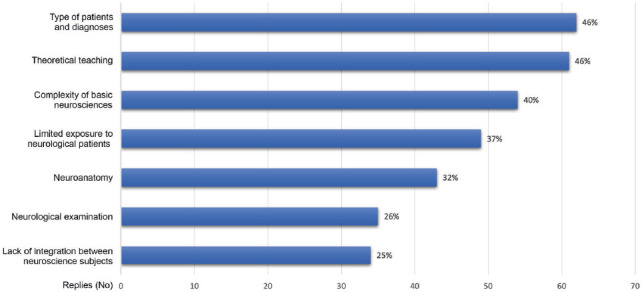

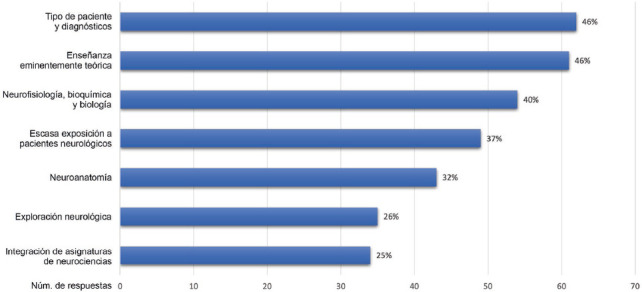

Entre los principales motivos identificados por los residentes como causantes de sus miedos y dificultades hacia la neurología encontramos el tipo de paciente y diagnósticos (62; 46%), y una enseñanza eminentemente teórica durante la etapa universitaria (61; 46%). El conjunto de motivos y su peso se muestran en la figura 1. Al realizar un subanálisis comparativo entre los residentes de MdF y el resto, encontramos diferencias significativas en los que identificaban la escasa exposición a pacientes como motivo para su neurofobia (el 20,6% de MdF frente al 50,7% de especialidades hospitalarias; p < 0,01).

Figura 1.

Motivos que identifican los médicos internos residentes (MIR) como la causa de sus dificultades, miedo o rechazo hacia la neurología. Diagrama de barras con respuesta de selección múltiple y opción abierta. Por ‘Integración de la enseñanza’ nos referimos a la fragmentación de las asignaturas de neurociencias durante los años universitarios y su impartición sin coordinación entre sí.

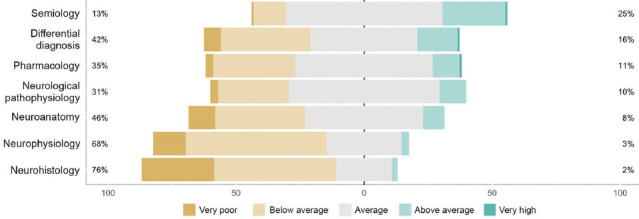

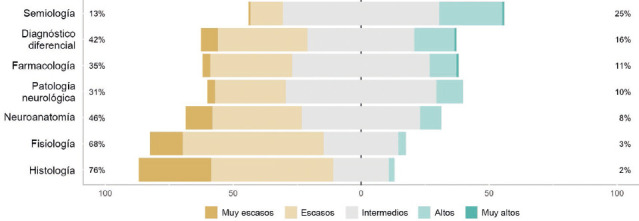

Al preguntar sobre neurología y áreas básicas de conocimiento en neurociencias (neuroanatomía, histología, fisiología, farmacología y patología médica), 121 encuestados (90,3%) consideraron tener conocimientos escasos o muy escasos al menos en una de ellas. En la figura 2 se visualiza la percepción de todas las subáreas y sus frecuencias relativas.

Figura 2.

Autopercepción de conocimientos en distintas disciplinas de neurociencias. Diagrama de frecuencia de distribución de respuestas en escala Likert (1-5); en los extremos, porcentaje agregado de respuestas extremas: ‘muy escasos-escasos’ (1-2) y ‘altos-muy altos’ (4-5).

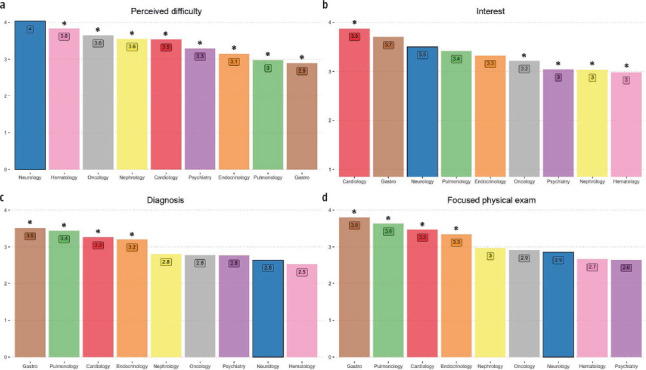

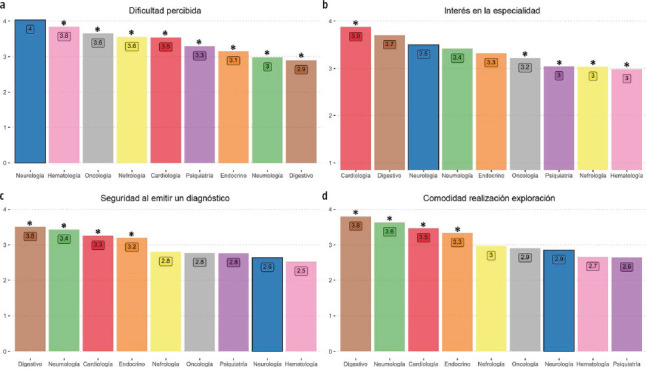

A continuación, se interrogó sobre el interés, la dificultad percibida, la seguridad al emitir un diagnóstico diferencial y la comodidad al realizar una exploración dirigida en las siguientes especialidades: cardiología, gastroenterología, neurología, neumología, endocrinología, oncología, psiquiatría, nefrología y hematología (Fig. 3). La neurología fue la tercera disciplina que mayor interés despertó, por detrás de la cardiología y la gastroenterología. Al mismo tiempo, la neurología se consideró la de mayor dificultad (p < 0,05 respecto al resto).

Figura 3.

Diagrama de barras de la percepción residentes de Aragón acerca de las diferentes especialidades médicas en cuanto a dificultad percibida (a), interés en la materia (b), seguridad al emitir un diagnóstico diferencial (c) y comodidad al realizar una exploración dirigida (d). Puntuación media de respuestas en escala Likert de 1 a 5. Se ofrece una comparativa de la neurología frente a cardiología, endocrinología, gastroenterología, hematología, nefrología, neumología, neurología, psiquiatría y oncología; identificando con * cuando el valor de p es < 0,05 frente a neurología.

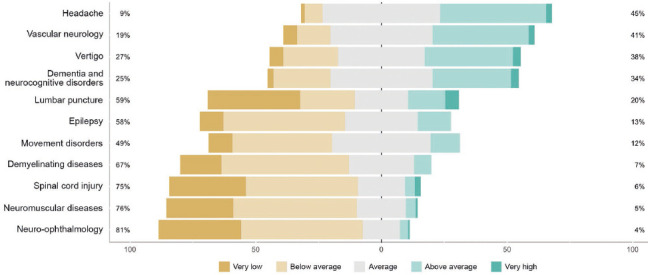

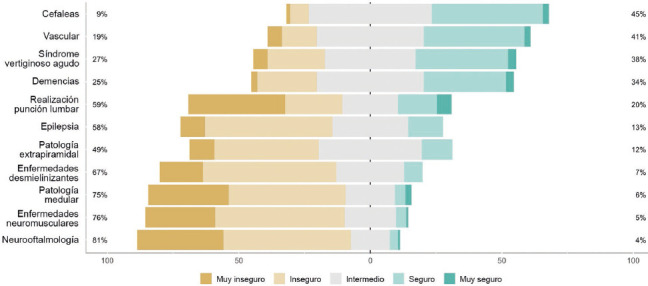

Por último, se preguntó a los residentes sobre su seguridad al abordar pacientes en urgencias con distintas patologías neurológicas (Fig. 4). Las áreas donde menor seguridad mostraron (Likert 1-2: ‘inseguro-muy inseguro’) fueron la neurooftalmología (108; 81%), seguida de la patología neuromuscular (100; 76%) y la lesión medular aguda (99; 75%). Por contrapartida, donde mayor seguridad notificaron (Likert 4-5 ‘seguro-muy seguro’) fue en cefaleas (59; 45%) y patología vascular (54; 41%). Al realizar un subanálisis comparativo entre los residentes de MdF y los de especialidades hospitalarias, encontramos diferencias significativas en la inseguridad al valorar a pacientes con demencia y trastornos cognitivos (el 16% de MdF frente al 33% de especialidades hospitalarias; p = 0,03), y la seguridad al valorar a pacientes con síndrome vertiginoso agudo (el 52% de MdF frente al 26% de especialidades hospitalarias; p < 0,01).

Figura 4.

Seguridad al abordar a un paciente en urgencias en distintas subespecialidades neurológicas. Diagrama de frecuencia de distribución de respuestas en escala Likert (1-5); en los extremos, porcentaje agregado de respuestas extremas: ‘muy escasos-escasos’ (1-2) y ‘altos-muy altos’ (4-5).

Discusión

Existen escasos trabajos que estudien la neurofobia específicamente en médicos durante la etapa de formación reglada, y ninguno hasta la fecha concretamente en los servicios de urgencias. Hemos constatado que la neurofobia no es sólo un problema endémico entre los estudiantes de medicina, sino que se mantiene entre los médicos residentes, variando las causas.

A lo largo de la carrera profesional como médicos, el contacto con la patología neurológica es inevitable, independientemente de la especialidad. A nivel global, las enfermedades neurológicas son la primera causa de años de vida perdidos ajustados por discapacidad y la segunda causa de mortalidad [9]. Además, suponen uno de los principales motivos de consulta urgente [10,11]. En el clima actual de sobrecarga de la atención primaria se ha incrementado más aún la demanda sobre los servicios de urgencias, convertidos en la puerta de entrada al sistema para muchos pacientes [12]. Es ahí donde el primer contacto con el paciente lo realizan a menudo médicos en formación de diversas especialidades, con sus miedos e inseguridades a pesar de la supervisión existente. La neurofobia entre los MIR puede conducir a una mala interpretación de los síntomas y signos neurológicos, acarreando diagnósticos incorrectos o demorados. A su vez, los médicos con neurofobia pueden sentirse incómodos al manejar enfermedades neurológicas, lo que puede dar lugar a derivaciones innecesarias y a una atención fragmentada para los pacientes [1,6]. Esto puede generar una mayor carga en el sistema y aumentar los costos asociados con la atención de salud [13].

En nuestro trabajo, el 27,6% de los MIR ‘sufriría’ neurofobia. No existe una definición formal de este fenómeno, por lo que la capacidad de comparación entre distintos trabajos es limitada. Sin embargo, nuestras cifras se asemejan a las descritas en otros trabajos realizados en estudiantes [14-16] y médicos jóvenes [7]. Un trabajo previo de nuestro grupo encontró una tasa de neurofobia del 34,1% entre los alumnos de medicina del mismo territorio [17]. Los escasos trabajos que han comparado de forma indirecta la neurofobia entre estudiantes y médicos en formación han encontrado una ligera menor prevalencia entre estos últimos [3,4,7], como también se observa en los trabajos de nuestro grupo. Esto evidencia que se trata de una percepción dinámica y, por tanto, modificable.

Podríamos pensar que estos miedos son también extensibles a otras patologías encontradas en las urgencias. Sin embargo, cuando comparamos la neurología con otras especialidades, vemos que ésta no deja indiferente. Se percibe como la disciplina de mayor dificultad e inseguridad al emitir un diagnóstico o realizar una exploración dirigida, pero, a la vez, se encuentra entre las especialidades que mayor interés suscitan. ¿Cuál es entonces la causa de estos miedos y dificultades? Como ya adelantaba Jozefowicz [1], la génesis de la neurofobia se encuentra en la ‘incapacidad de aplicar los conocimientos de neurociencias básicas a situaciones clínicas concretas’, es decir, en la dificultad de trasladar sus conocimientos teóricos a la realidad asistencial del paciente; pero parecen existir diferencias entre las etapas del pregrado y posgrado.

En nuestra serie, las principales razones para dichos miedos fueron el tipo del paciente y sus diagnósticos (46%), y la enseñanza eminentemente teórica (46%), por delante de los conocimientos de neurociencias básicas (40%) y la escasa exposición a pacientes neurológicos (37%), factores que se repiten en los distintos estudios publicados [2,13, 18,19]. Merece atención especial la situación de la neuroanatomía. Por una parte, casi la mitad de los residentes (46%) consideraban sus conocimientos en dicha área escasos o muy escasos, pero apenas un tercio (32%) lo identificaba como un factor para su miedo a la neurología. Este porcentaje contrasta con los resultados obtenidos en estudios realizados con estudiantes, donde la neuroanatomía tenía un peso mucho mayor (el 47,8% en nuestro trabajo previo [17]). No obstante, esta tendencia ya se intuía al acotar a estudiantes universitarios de último año y se reproduce en otros trabajos [3]. Podemos decir que, conforme nos enfrentamos a situaciones clínicas reales, no damos tanto peso a nuestros conocimientos en ciencias básicas en sí, sino a su utilidad y cómo los aplicamos en cuestiones de práctica diaria.

No encontramos diferencias en la tasa de neurofobia entre los residentes de MdF y los de especialidades hospitalarias ni entre los que realizaban una rotación específica de neurología y los que no. Esto nos reafirma en la opinión de que el mejor momento para abordar el miedo o rechazo a la neurología sería desde el inicio de la formación universitaria y no tanto en momentos formativos más avanzados. Además, no existieron diferencias en cuanto a la presencia de neurofobia entre MIR que realizan su actividad de urgencias en centros con guardia de neurología 24 horas y los que no, por lo que un mayor acceso al neurólogo no parece mitigar ni favorecer este rechazo. Finalmente, tampoco encontramos diferencias en la presencia de neurofobia entre los que estudiaron la carrera en nuestra región, en otras universidades españolas o en el extranjero (Hispanoamérica), lo que nuevamente reafirma que la neurofobia se trata de un fenómeno global [3,7,14,20,21].

De especial interés nos parecen las percepciones en cuanto al abordaje de los diferentes motivos de consulta neurológica que pueden presentarse en urgencias. Las áreas donde mayor seguridad mostraban los residentes fueron las cefaleas y la patología neurovascular. Por el contrario, donde mayor inseguridad existía fue en la patología neuromuscular y la neurooftalmología seguidas de la lesión medular aguda. No resulta sorprendente comprobar que las patologías donde más cómodos se encuentran se solapan con las patologías neurológicas más prevalentes, y viceversa [22]. Es decir, se muestran más seguros en las que son más frecuentes y, en definitiva, tienen mayor exposición en las urgencias. En este sentido, encontramos muy ilustrativo cómo comparando MIR de MdF con los de hospitalaria, los primeros se mostraban significativamente menos inseguros al valorar a pacientes con trastornos cognitivos y con mareo/vértigo, ambos motivos de consulta frecuentes en el ambulatorio. Asimismo, era significativamente menor la proporción de residentes de MdF que aducían la escasa exposición a pacientes como causa de su neurofobia, dado su continuo contacto con un variado tipo de pacientes. Sí que resulta llamativo cómo la realización de punción lumbar, pese a ser una técnica rutinaria y fundamental en los servicios de urgencias, resultó el área de mayor inseguridad a nivel individual, sin llegar a encontrar diferencias significativas entre MdF y especializada. Todo ello no hace sino reforzar lo expuesto en párrafos anteriores, de cómo el quid de la neurofobia yace en la docencia y la falta de exposición para aplicar sus conocimientos teóricos. Pese a todo, en ninguna de las áreas de la neurología subsidiarias de presentarse en urgencias había un porcentaje mayor del 50% de MIR que se sintieran seguros o muy seguros, por lo que todavía hay mucho por hacer en la etapa de formación sanitaria especializada.

Por último, debemos destacar que la mayoría de los trabajos que abordan la neurofobia entre profesionales se ha centrado en el entorno hospitalario. Nuevos estudios que analicen otras realidades, como la atención primaria, serían de gran ayuda para estudiar y entender este fenómeno.

Limitaciones

Las principales limitaciones del estudio son las propias del uso de encuestas autoadministradas. Las encuestas se remitieron a través de las unidades docentes de cada centro, pero no es posible asegurar con certeza absoluta quién las contestó ni el grado de información o compromiso. Esta debilidad es compartida por trabajos con similar metodología. Por su parte, la tasa de respuesta por parte de los MIR, aunque reducida, ha permitido disponer de grupos de tamaño similar entre médicos en formación de atención primaria y hospitalaria. Casi la mitad de nuestra muestra corresponde a médicos residentes de la especialidad de medicina familiar y comunitaria. Este sesgo de selección se debe al entorno al que se encuentra dirigido, aunque, al mismo tiempo, la hace más representativa de la realidad de los equipos de residentes en los servicios de urgencias.

Conclusión

La neurofobia no es un fenómeno exclusivo de estudiantes universitarios, sino que también está muy presente entre los residentes en formación que desempeñan su labor en los servicios de urgencias. La demanda de atención urgente está en ascenso y la atención a las urgencias de neurología ha experimentado un importante cambio en los últimos años. La neurofobia podría repercutir, por consiguiente, en la asistencia y el manejo de estos pacientes. Su distribución entre los motivos de consulta parece depender del grado de exposición a pacientes. Como escribió el filósofo estadounidense Will Durant: ‘Somos lo que hacemos repetidamente. La excelencia no es un acto, es un hábito’. El tratamiento de la neurofobia ha de centrarse, por tanto, en la docencia y aplicabilidad práctica de los conocimientos adquiridos. Los neurólogos debemos desempeñar un papel activo en la formación de nuevos especialistas y colaborar activamente con los servicios de urgencias.