Abstract

Conjugate vaccines were prepared by binding hydrazine-treated lipopolysaccharide (DeALPS) from Vibrio cholerae O1, serotype Inaba, to cholera toxin (CT) variants CT-1 and CT-2. Volunteers (n = 75) were injected with either 25 μg of DeALPS, alone or as a conjugate, or the licensed cellular vaccine containing 4 × 109 organisms each of serotypes Inaba and Ogawa per ml. No serious adverse reactions were observed. DeALPS alone did not elicit serum LPS or vibriocidal antibodies in mice and only low levels of immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti-LPS in the volunteers. Recipients of the cellular vaccine had the highest IgM anti-LPS levels, but the difference was not statistically significant from that elicited by the conjugates. The conjugates elicited the highest levels of IgG anti-LPS (DeALPS-CT-2 > DeALPS-CT-1 > cellular vaccine). Both conjugates and the cellular vaccine elicited vibriocidal antibodies: after 8 months, recipients of cellular vaccine had the highest geometric mean titer (1,249), followed by DeALPS-CT-2 (588) and DeALPS-CT-1 (330). The correlation coefficient between IgG anti-LPS and 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME)-resistant vibriocidal antibodies was 0.81 (P = 0.0004). Convalescent sera from cholera patients had a mean vibriocidal titer of 2,525 that was removed by treatment with 2-ME. The vibriocidal activities of sera from all vaccine groups and from the patients were absorbed (>75%) by LPS but not by either CT-1 or CT-2. Conjugate-induced IgG vibriocidal antibodies persisted longer than those elicited by the whole-cell vaccine. Both conjugates, but not the cellular vaccine, elicited IgG anti-CT.

Cholera occurs throughout much of the developing world, with its highest attack rate, morbidity, and mortality in children (4, 10, 23, 31, 32). Routine vaccination for cholera in areas where the disease is endemic and epidemic has not been implemented due to deficiencies in the licensed vaccines. (i) Parenterally administered cellular vaccines, composed of inactivated Vibrio cholerae O1, elicit side reactions, limited immunity in adults of ∼60% with a duration of ∼6 months, and a lesser efficacy in children (2, 4, 10, 24, 25, 32); (ii) orally administered killed cellular vaccines exert fewer side reactions, confer a similar degree of efficacy after 5 years, but are less efficacious in children (5, 6); and (iii) an orally administered attenuated strain of V. cholerae, CVD103-HgR, is safe and induced vibriocidal antibodies, but its efficacy in an at-risk population, especially children, has not yet been characterized (23). The above vaccines could not be administered in the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis formulation given routinely to infants. Lastly, neither the protective moieties in the orally administered vaccines nor the host factors elicited by these two products have been correlated with vaccine-induced protection.

Cholera is considered a noninvasive disease because the causative agent is confined to the intestinal lumen (6, 12, 16, 17, 30, 31). Serum vibriocidal activity is the only immune moiety that has been correlated with resistance to cholera caused by V. cholerae O1 (18, 23). Studies of endemic and epidemic cholera and cellular or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) vaccines in Bangladesh showed that the incidence of disease was inversely related to the serum vibriocidal titer (1, 2, 10, 12, 23, 24). Further, cholera was not detected in individuals with a vibriocidal titer of ≥1:160 (1, 10, 12, 16, 24, 25, 33). Most, if not all, serum vibriocidal activity is mediated by LPS antibodies (1, 4, 5, 7, 10, 14, 16–18, 23, 24, 26, 31). We proposed that a critical level of vaccine-induced serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-LPS with vibriocidal activity could confer long-lived protective immunity to cholera and outlined a mechanism by which this may occur (13, 30, 31).

In this study, we synthesized and evaluated in healthy volunteers the safety and immunogenicity of conjugates prepared with the O-specific polysaccharide from V. cholerae O1 serotype Inaba bound to cholera toxin (CT) with a spacer (13). Vibriocidal antibodies elicited by these conjugates were specific for the LPS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study protocols.

Vaccine and study protocols were approved as follows: National Institutes of Health Protocol no. 92-CH-0253, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research Protocol no. 433, and Food and Drug Administration Bureau of Biologics Investigational New Drug no. 4480.

Polysaccharide.

LPS was purified from acetone-treated cells of V. cholerae O1 569B, biotype classic, serotype Inaba, lot VC12-19 (Richard Finkelstein, University of Missouri) (13). LPS (800 mg) was dried over P2O5, suspended in 80 ml of anhydrous hydrazine (Sigma Fine Chemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) (13), and placed in a 37°C water bath for 2 h with stirring (13). The resultant precipitate was washed with cold 90% acetone, centrifuged (35,000 rpm, 10°C, 5 h), and passed through a 2.5- by 50-cm column of G-50 Sephadex (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) in pyrogen-free water; the void volume fractions were sterile filtered through a 0.25-μm-pore-size membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) and freeze dried. The product, designated DeALPS and stored at −20°C, contained less than 10 endotoxin units (EU)/μg and <1% protein or nucleic acid.

Proteins.

CT variant 1 (CT-1), lot 582, was from Pasteur-Mérieux Institute, Lyon, France, purified from V. cholerae 569B, biotype classical, serotype Inaba. CT variant 2 (CT-2) was prepared by Richard Finkelstein from V. cholerae 3038, biotype El Tor, serotype Ogawa (21). Both CT-1 and CT-2 were passed through a 5- by 90-cm column of Sephadex G-25 in pyrogen-free saline; the void volume fractions were concentrated and sterile filtered.

Conjugation.

DeALPS (10 mg/ml) was activated at pH 10.5 with CNBr (Sigma) and bound to adipic acid dihydrazide (ADH) at pH 8.5, designated as DeALPS-AH (Sigma) (13). The extent of derivatization was determined by 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). CT-1 or CT-2 was mixed with DeALPS-AH in pyrogen-free saline in equal weight (100 mg in 30 ml), and 450 mg of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (Sigma) was added. The reaction mixture was maintained at pH 5.5 to 5.7 for 2 h and passed through a 2.5- by 90-cm column of G-50 Sephadex in 0.2 M NaCl–0.005 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.3). Fractions containing protein and polysaccharide were pooled, thimerosal was added to 0.01%, and the preparations were sterile filtered and designated DeALPS-CT-1 and DeALPS-CT-2, respectively.

Serologic determinations.

LPS and CT antibody levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (13). Plates were coated with 100 μl of LPS (10 μg/ml) or CT (5 μg/ml). LPS antibodies were expressed in ELISA units, using a convalescent serum from Peru (1991) (Richard Hamberger, Naval Medical Research Institute, Bethesda, Md.) or serum from volunteer 24, who had a high postvaccination titer, as the reference.

Bioassays.

LPS (Limulus amebocyte lysate [LAL] assay; Associates of Cape Cod, Woods Hole, Mass.) was expressed as EU related to the U.S. standard (13). Pyrogenicity in the rabbit thermal induction assay was kindly performed by Donald Hochstein, Food and Drug Administration. Toxicity of CT was estimated by Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell elongation (13). Serum vibriocidal antibody was measured with V. cholerae O1 strain 075, biotype El Tor, serotype Inaba, an isolate from Peru (1991), as a target (3, 10, 11, 13). Tenfold serum dilutions were mixed with equal volumes of ∼103 cells/ml in diluted guinea pig serum and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution that yielded 50% killing. Absorption of vibriocidal activity was assayed by mixing equal volumes of 200 μg of LPS, DeALPS, or CT per ml with equal volumes of dilutions of antisera at 37°C for 1 h prior to addition of the bacteria (11, 26). Inactivation of IgM was done by mixing equal volumes of sera and 0.2 M 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) and incubating at 4°C overnight (22). The sera were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C with three changes of the outer fluid, and the vibriocidal activity was assayed (22).

Immunization of mice.

Six-week-old general-purpose mice (National Institutes of Health) (13) were injected subcutaneously three times at 2-week intervals with 2.5 μg of DeALPS as a conjugate or with saline and bled 7 to 10 days after each immunization. Vibriocidal antibodies were assayed in pooled sera of each bleeding.

Study design.

Volunteers, between 18 and 44 years old and without a history of chronic disease, cholera, or vaccination with cholera vaccines, were sought from Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Washington, D.C. After informed consent was obtained, the volunteers were randomized into four groups of 20 each; two groups received one of the conjugates, one group received the DeALPS, and one group received the licensed cellular cholera vaccine containing serotypes Inaba and Ogawa (4 × 109 organisms of each/ml), kindly provided by Frank McCarthy, Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, Marietta, Pa. Each volunteer received an injection of the same vaccine 6 weeks later. Temperatures were taken, and local reactions were inspected 0, 6, 24, and 48 h postinjection. Volunteers were bled before and 28, 42, 70, and 230 days after the first injection.

Convalescent-phase sera.

Twelve sera, taken from patients 2 to 4 weeks after the onset of symptoms during an outbreak of cholera in southern Mexico in 1992, were provided by Jose Luis Valdespino Gomez, Instituto National de Diagnostica, Mexico City, Mexico.

Statistics.

Calculations used logarithms of antibody levels. Data were analyzed with the Statistical Analysis System. Each concentration below the sensitivity of the ELISA was assigned one-half of that value. Comparisons of geometric means (GMs) were performed by paired and unpaired t tests when appropriate.

RESULTS

Characterization of the conjugates.

The endotoxin content of the DeALPS was ∼2 EU/μg by LAL assay (17) (Table 1). DeALPS-CT-1 had a higher endotoxin level (80 EU of saccharide/μg or 2,000 EU/dose) compared to DeALPS-CT-2 (<10 EU of saccharide/μg or <250 EU/per dose). A human dose of either conjugate was not pyrogenic in the rabbit thermal induction test. CT induced elongation in CHO cells at 0.4 ng/ml, but a human dose of either conjugate had no activity in this assay. Both conjugates passed the general safety test as described in the Code of Federal Regulations [C, 610.13 (b)].

TABLE 1.

Compositions of DeALPS-CT-1 and DeALPS-CT-2

| Conjugatea | DeALPS (μg/ml) | Protein (μg/ml) | Protein/DeALPS | Yield (% DeALPS) | EU/dose determined by LAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeALPS-CT-1 | 390 | 570 | 1.47 | 51 | 2,000 |

| DeALPS-CT-2 | 200 | 310 | 1.55 | 31 | <250 |

The DeALPS-AH derivative used for both conjugates contained 2.16% (wt/wt) AH.

The DeALPS had 2.16% ADH. The two conjugates had a similar protein/DeALPS compositions (∼1.5, wt/wt).

Vibriocidal antibodies of mice.

DeALPS alone did not elicit vibriocidal antibodies after any injection. DeALPS-CT-1 elicited rises of vibriocidal antibodies after each of the first three injections (titers of 100, 500, and 50,000); these levels were considerably higher than those following injection of DeALPS-CT-2 (titers of <10, 10, and 50) (13) (data not shown).

Adverse reactions in volunteers.

There were no serious local or systemic reactions in the volunteers following the first injection: ∼20% injected with the conjugates or the DeALPS alone had a temperature of 37.2 to 37.5°C for 24 h (Table 2). There were no reactions following the second injection (not shown).

TABLE 2.

Adverse reactions of volunteers

| Vaccine | n | Symptom at injection sitea

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Erythema | Induration | ||

| DeALPS-CT-1 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| DeALPS-CT-2 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DeALPS | 19 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cellular | 18 | 7 | 0 | 3 |

In all groups, there was neither fever of >37.5°C nor nodes.

IgM and IgG anti-LPS of the volunteers. (i) IgM.

DeALPS alone did not elicit IgM anti-LPS after the first or at 28 days after the second injection (Table 3). There was a slight rise of the GM IgM anti-LPS 230 days later (4.6 versus 1.1, P = 0.0001), but this level was significantly lower than those of the recipients of the conjugates or of the cellular vaccine (13.7, 12.0, 16.9 versus 4.6, P < 0.001). The conjugates and the cellular vaccine elicited high GM IgM anti-LPS (P < 0.001) compared to the preimmunization levels; neither the conjugates nor the cellular vaccine elicited booster responses after the second injection. The cellular vaccine elicited the highest GM level of IgM anti-LPS, but this was not statistically significant compared to the conjugate groups.

TABLE 3.

Serum IgM and IgG anti-LPS titers of vaccinees

| Immunogen | n | GM ELISA titera (25th–75th centiles) at indicated day postinjection

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (preinjection) | 28 | 42b | 70 | 230 | ||

| IgM | ||||||

| DeALPS-CT-1 | 19 | 1.9 (0.9–3.9) | 10.6 (3.6–35) | 8.5 (3.4–31) | 8.4 (4.0–29) | 13.7 (4.0–31) |

| DeALPS-CT-2 | 19 | 1.3 (1.0–2.5) | 17.4 (6.9–52) | 14.2 (5.4–38) | 12.5 (5.3–30) | 12.0 (6.0–24) |

| DeALPS | 19 | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) | 1.1 (1.0–2.5) | 1.2 (0.7–2.6) | 1.7 (0.9–3.2) | 4.6 (3.3–7.7) |

| Cellularc | 18 | 1.6 (1.0–4.0) | 19.2 (9.6–39) | 16.0 (7.4–26) | 15.3 (8.7–36) | 16.9 (8.4–29) |

| IgG | ||||||

| DeALPS-CT-1 | 19 | 2.8 (0.8–7.1) | 7.2 (1.3–30) | 7.1 (1.3–49) | 7.2 (1.0–29) | 3.4 (0.7–4.0) |

| DeALPS-CT-2 | 19 | 1.8 (0.7–4.4) | 14.3 (0.7–124) | 18.2 (5.8–120) | 17.6 (4.2–82) | 5.1 (1.3–29) |

| DeALPS | 19 | 2.1 (0.9–4.8) | 2.9 (1.1–6.8) | 3.3 (1.1–10) | 2.1 (0.8–6.7) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) |

| Cellular | 18 | 2.2 (0.8–5.8) | 4.9 (1.1–18) | 4.8 (1.2–26) | 5.9 (1.7–24) | 3.4 (1.6–5.3) |

Expressed as percentage of a reference serum (M&M) assigned a value of 100. Post- versus prevaccination sera from vaccinees injected with the two conjugates and the cellular vaccine had higher GM levels (P < 0.001); there was no statistically significant difference between the postvaccination levels of the three groups at any interval. For recipients of DeALPS alone, 4.6 versus 1.1, P = 0.0001. For IgG, 14.3 versus 4.9 and 17.6 versus 5.9, P = 0.05; 18.2 versus 4.8, P = 0.03; 5.1 versus 3.4, P = NS.

Blood sample taken and reinjected with same vaccine.

Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, 4 × 109 organisms each of V. cholerae O1 serotypes Inaba and Ogawa.

(ii) IgG.

Following the first injection, the conjugates and the cellular vaccine elicited a significant rise of IgG anti-LPS. The highest GM level was in the recipients of DeALPS-CT-2, but the difference between this level and those of the other two groups was not statistically significant (Table 3). There was no booster effect after the second injection. The level of IgG anti-LPS of all three groups declined after 230 days; only the recipients of DeALPS-CT-2 had IgG anti-LPS levels that were significantly higher than the preimmunization levels (5.1 versus 1.8, P = 0.057). DeALPS alone did not elicit IgG anti-LPS.

Vibriocidal antibodies of volunteers.

The cellular vaccine and conjugates elicited vibriocidal antibodies after the first injection (Table 4). The highest level was elicited by the cellular vaccine (3,981 versus 1,645 for DeALPS-CT-2, not significant; 3,981 versus 1,090 for DeALPS-CT-1, P = 0.03); reinjection did not elicit a further rise. At 230 days, vibriocidal levels declined to about one-third of their highest values, in the order cellular vaccine > DeALPS-CT-2 > DeALPS-CT-1; these differences were not statistically significant. DeALPS alone did not elicit vibriocidal antibodies at any interval.

TABLE 4.

Serum vibriocidal titers of vaccineesa

| Immunogen | n | GM titer (range) at indicated day after immunization

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (preimmunization) | 28 | 42b | 70 | 230 | ||

| DeALPS-CT-1 | 19 | 11 (5–32) | 1,090 (320–6,400) | 884 (220–6,400) | 629 (20–3,200) | 330 (64–1,280) |

| DeALPS-CT-2 | 19 | 15 (5–128) | 1,645 (640–12,800) | 1,405 (640–12,800) | 1,253 (400–6,400) | 588 (128–3,200) |

| DeALPS | 19 | 17 (5–128) | 29 (5–200) | 30 (5–200) | 32 (5–200) | 33 (8–128) |

| Cellularc | 18 | 15 (5–40) | 3,981 (3,200–12,800) | 2,343 (1,600–6,400) | 1,835 (800–6,400) | 909 (200–3,200) |

V. cholerae O1 strain 075, serotype Inaba, was the target organism.

Blood sample taken and volunteer reinjected with the same vaccine.

Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, containing 4 × 109 organisms each of V. cholerae O1 serotypes Inaba and Ogawa.

IgG anti-LPS and 2-ME-resistant vibriocidal activity.

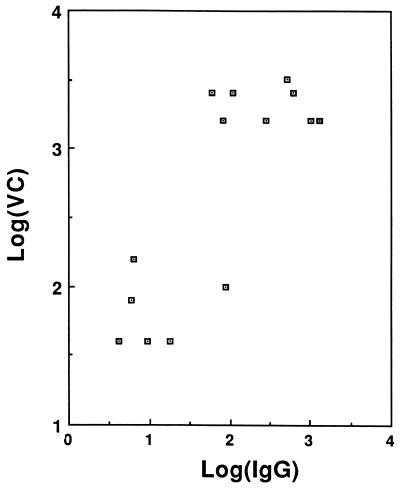

The vibriocidal titers of 2-ME-treated sera were related to the IgG anti-LPS levels. The correlation coefficient by the Pearson method is r = 0.81, P = 0.0004 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Correlation between IgG anti-LPS and 2-ME-resistant vibriocidal activity. The correlation coefficient by the Pearson method is r = 0.81, P = 0.0004.

Absorption of volunteer sera with LPS or CT.

At least 80 to 96% of the vibriocidal activity from the sera of the recipients of the conjugates or the cellular vaccine was removed by absorption with LPS (Table 5). We were unable to remove vibriocidal activity completely from any of the three groups with as much as 1 mg of LPS/ml of serum. CT did not remove vibriocidal activity from any sera.

TABLE 5.

Effects of absorption of postimmunization sera on vibriocidal titers of vaccinees

| Vaccine | Vaccinee no. | Titera

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | LPS | CT | ||

| DeALPS-CT-1 | 3 | 3,200 | 640 | 3,200 |

| 37 | 25,600 | 80 | 25,600 | |

| 42 | 6,400 | 320 | 6,400 | |

| 61 | 3,200 | 320 | 3,200 | |

| 74 | 1,600 | 5 | 1,600 | |

| DeALPS-CT-2 | 29 | 25,600 | 640 | 25,600 |

| 44 | 12,800 | 640 | 12,800 | |

| 60 | 6,400 | 40 | 3,200 | |

| 63 | 6,400 | 160 | 6,400 | |

| 64 | 3,200 | 320 | 3,200 | |

| Cellular | 10 | 6,400 | 160 | 6,400 |

| 13 | 6,400 | 160 | 6,400 | |

| 43 | 3,200 | 5 | 3,200 | |

| 55 | 3,200 | 320 | 3,200 | |

Undiluted sera were mixed with an equal volume of either LPS or DeALPS (purified from serotype Inaba) containing 200 μg of saccharide per ml and then incubated at 37°C for 1 h and overnight at 3 to 8°C. The vibriocidal titer of the sera was then assayed with V. cholerae O1 strain 075, serotype Inaba, as the target organism.

Vibriocidal antibodies of the patients.

The sera of patients with cholera in Peru had vibriocidal antibody titers ranging from 25 to 15,625 (Table 6). Sera with titers of ≥125 had most of their vibriocidal activity removed by absorption with LPS or DeALPS; in most cases, LPS was a more effective absorbent than DeALPS. Treatment of the patient sera with 2-ME removed vibriocidal activity (not shown). These data show that most of the vibriocidal activity of the patient sera was of the IgM class and directed to the LPS. As with the vaccinees, absorption with CT did not remove vibriocidal activity.

TABLE 6.

Serum vibriocidal antibodies of cholera patients following absorption with LPS or DeALPS

| Patient no. | Titera

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unabsorbed | Inaba

|

Ogawa

|

|||

| LPS | DeALPS | LPS | DeALPS | ||

| 1 | 25 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 16 |

| 2 | 125 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 125 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 8 |

| 4 | 625 | 8 | 32 | 128 | 128 |

| 5 | 625 | 16 | 64 | 64 | 32 |

| 6 | 625 | 4 | 120 | 128 | 160 |

| 7 | 625 | 8 | 64 | 64 | 128 |

| 8 | 3,125 | 64 | 120 | 1,280 | 1,280 |

| 9 | 3,125 | 8 | 64 | 160 | 640 |

| 10 | 3,125 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 80 |

| 11 | 15,625 | 8 | 64 | 64 | 640 |

Results are for sera from adults 3 to 5 months following culture-verified cholera. Undiluted sera were mixed with an equal volume of either LPS or DeALPS containing 200 μg of saccharide per ml and then incubated at 37°C for 1 h and overnight at 3 to 8°C. V. cholerae O1 strain 075, serotype Inaba, was the target organism.

Serum IgG CT antibodies of the vaccinees.

Twenty-eight days following the first injection, there was significant antibody rise in groups injected with conjugates but not in the groups injected with DeALPS or the cellular vaccine (Table 7). There was no rise in GM antibody levels of the conjugate groups after the second injection. These antibody levels decreased quickly at 230 days but remained higher than the preimmune levels and the levels of the groups injected with DeALPS or cellular vaccine (P < 0.001).

TABLE 7.

Serum IgG CT antibody titers of vaccinees

| Vaccine | n | GM ELISA titera (25th–75th centiles) at indicated day postinjection

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (preinjection) | 28 | 70 | 230 | ||

| DeALPS-CT-1 | 19 | 0.48 (0.38–0.70) | 6.31 (4.92–19) | 7.68 (5.34–19) | 2.68 (1.48–6.54) |

| DeALPS-CT-2 | 19 | 0.72 (0.48–0.94) | 11.5 (2.28–53) | 13.2 (3.06–53) | 5.08 (1.83–9.16) |

| DeALPS | 19 | 0.73 (0.45–1.07) | 1.26 (0.75–1.66) | 1.09 (0.52–1.66) | 1.00 (0.48–1.73) |

| Cellularb | 18 | 0.67 (0.49–0.91) | 1.19 (0.68–2.44) | 1.36 (0.78–2.44) | 0.95 (0.46–1.85) |

Expressed as in Table 3. Plates were coated with CT-1 (0.5 μg/well). Comparisons: 6.31, 11.5 versus 1.26, 1.19, P < 0.001; 5.08 versus 1.00, 0.95, P < 0.002; 2.68 versus 1.00, 0.95, P = 0.03; 5.08 versus 2.68, 11.5 versus 6.31, and 13.2 versus 7.68, not significant.

Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, containing 4 × 109 organisms each of V. cholerae O1 serotypes Inaba and Ogawa.

DISCUSSION

The O-specific polysaccharide conjugates were safe and induced both serum IgM and IgG anti-LPS with bactericidal activity and IgG anti-CT. Although considered a marker only, the vibriocidal antibody titer reliably predicts resistance to cholera and is the only serologic assay required by the Food and Drug Administration for licensure of new cholera lots (5, 9, 12, 16, 23–25, 30, 31). We proposed that serum vibriocidal antibodies confer immunity to cholera by lysing the inoculum of V. cholerae O1 on the epithelial surface of the small intestine (9, 13, 30, 31). Most if not all vibriocidal antibodies, whether acquired by individuals without cholera (natural), by patients, or by recipients of the cellular vaccine or LPS are directed to the LPS of V. cholerae O1 (1, 3, 5, 9, 10, 12, 13, 17, 24–26, 30, 31).

Parenterally administered cellular cholera vaccines, as with other gram-negative bacteria (8, 13, 22, 33), elicit high levels of mainly IgM anti-LPS for about 6 months. The rapid decline of this IgM vibriocidal activity explains the short-lived protection conferred by cellular vaccines (5, 16, 24, 25, 31). Similarly, most vibriocidal antibodies in patients, including those from Mexico, where cholera recurred after many years, are IgM anti-LPS, and their levels also decline rapidly. This disease-induced response, confined largely to IgM antibodies, provides an explanation for the recurrence of cholera (7, 18, 33, 34).

Several factors should be considered in relating vibriocidal titers to resistance to cholera. First, the specific vibriocidal activity of IgM antibodies is higher than that of IgG (29). Second, the concentration of IgG in the intestinal fluid is higher than that of IgM (28, 30, 31). We showed that the levels of IgG anti-LPS and 2-ME-resistant vibriocidal activity are correlated. Evidence that serum IgG anti-LPS is protective is derived from the observation that infants are protected from cholera, independent of breast feeding (24). The age incidence of cholera is highest in children, and conjugate vaccines have been shown to induce protective levels of polysaccharide antibodies in infants (30).

The O-specific polysaccharides of serotypes Inaba and Ogawa are cross-reactive and are composed of a linear homopolymer of about 14 residues of α(1→2)-d-perosamine whose amino groups are acylated by 3-deoxy-l-glycerotetronic acid (15); their serologic difference is only due to the fact that the O-specific polysaccharide from Ogawa has a methyl group on C-2 at the nonreducing end (14, 20). Cellular vaccines contain 4 × 109 organisms of Ogawa and of Inaba per ml. In most countries with endemic or epidemic cholera, strains of both V. cholerae O1 serotypes are isolated from patients (10, 32). Accordingly, we plan to prepare a bivalent formulation with the O-specific polysaccharides of both serotypes. We are, however, not satisfied with the level of IgG anti-LPS achieved with our conjugates, and methods to improve their immunogenicity, including using synthetic oligosaccharides of the V. cholerae serotypes, are under study (26).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Lynne Caufield, David Towne, and Danielle Rickrode, who performed the serologic assays, and to Vicky Tifft for clinical assistance with the volunteers. Rachel Schneerson, Richard A. Finkelstein, and Pavol Kováč provided helpful comments and suggestions for the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed A, Bhattacharjee A K, Mosley W H. Characteristics of the serum vibriocidal and agglutinating antibodies in cholera cases and in normal residents of the endemic and non-endemic cholera areas. J Immunol. 1970;105:431–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benenson A S, Mosley W H, Fahimuddin M, Oseasohn R O. Cholera vaccine field trials in East Pakistan. Bull W H O. 1968;38:359–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benenson A S, Saad A, Mosley W H. Serological studies in cholera. 2. The vibriocidal antibody response of cholera patients determined by a microtechnique. Bull W H O. 1968;38:277–285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bern C, Martines J, deZoysa I, Glass R I. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrhoeal disease: a ten-year update. Bull W H O. 1992;70:705–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemens J D, Van Loon E, Sack D A, Chakraborty J, Rao M R, Ahmed F, Harris J R, Khan M R, Yunus M, Huda S. Field trial of oral cholera vaccines in Bangladesh: serum vibriocidal and antitoxic antibodies as markers of the risk of cholera. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1235–1242. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.6.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemens J D, Sack D A, Harris J R, van Loon F, Chakraborty J, Ahmed F, Stanton B F, Kay B A, Walter S, Eeckels R, Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Field trial of oral cholera vaccines in Bangladesh: results from a three-year follow-up. Lancet. 1990;335:270–273. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90080-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clements M L, Levine M M, Young C R, Black R E, Lim Y L, Robins-Browne R M, Craig J P. Magnitude, kinetics, and duration of vibriocidal antibody responses in North Americas after ingestion of Vibrio cholerae. J Infect Dis. 1982;145:465–473. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeMaria A, Johns M A, Berbeerich H, McCabe W R. Immunization with rough mutants of Salmonella minnesota: initial studies in human subjects. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:301–311. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feeley J C. Proceedings of Cholera Research Symposium. Public Health Service publication 1328. U.S. Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office; 1965. Passive protective activity of antisera in infant rabbits infected orally with Vibrio cholerae; pp. 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkelstein R A. Cholera. In: Germanier R, editor. Bacterial vaccines. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1984. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelstein R A. Vibriocidal antibody inhibition (VAI) analysis: a technique for the identification of the predominant vibriocidal antibodies in serum and for the detection and identification of Vibrio cholerae antigens. J Immunol. 1962;89:264–271. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glass R I, Svennerholm A-M, Khan M R, Huda S, Huq M I, Holmgren J. Seroepidemiological studies of El Tor cholera in Bangladesh: association of serum antibody levels with protection. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:236–242. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta R K, Szu S C, Finkelstein R A, Robbins J B. Synthesis, characterization, and some immunological properties of conjugates composed of the detoxified lipopolysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O1 serotype Inaba bound to cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3201–3208. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3201-3208.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito T, Higuchi T, Hirobe M, Hiramatsu K, Yokota T. Identification of a novel sugar, 4-amino-4,6-dideoxy-O-methylmannose in the lipopolysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O1 serotype Ogawa. Carbohydr Res. 1994;256:113–128. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(94)84231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenne L, Lindberg B, Unger P, Holme T, Holmgren J. Structural studies of the Vibrio cholerae O-antigen. Carbohydr Res. 1979;68:C14–C16. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)84073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine M M. Immunity to cholera as evaluated in volunteers. In: Ouchterlony O, Holmgren J, editors. Cholera and related diarrheas. 43rd Nobel Symposium. S. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1980. pp. 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine M M, Black R E, Clements M L, Ciscernos I, Nalin R, Young C R. The quality and duration of infection-derived immunity to cholera. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:818–820. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.6.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine M M, Nalin D R, Craig J P, Hoover D, Bergquist E J, Waterman D, Holley P, Hornick R B, Pierce N P, Libonati J P. Immunity of cholera in man: relative role of antibacterial versus antitoxin immunity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979;73:3–9. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manning P A, Heuzenroeder M W, Yeadon J, Leavesley D I, Reeves P R, Rowley D. Molecular cloning and expression in Escherichia coli K-12 of the antigens of the Inaba and Ogawa serotypes of the Vibrio cholerae O1 lipopolysaccharide and their potential for vaccine development. Infect Immun. 1986;53:272–277. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.2.272-277.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchlewicz B A, Finkelstein R A. Immunological differences among the cholera/coli family of enterotoxins. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1983;1:129–138. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(83)90042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merrit C B, Sack R B. Sensitivity of agglutinating and vibriocidal antibodies to 2-mercaptoethanol in human cholera. J Infect Dis. 1970;121:S25–S30. doi: 10.1093/infdis/121.supplement.s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Migasena S, Pitisuttitham P, Prayurahong B, Suntharasamai P, Supanaranonod W, Desakorn V, Vongsthongsri U, Tall B, Ketley J, Losonsky G, Cryz S, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Preliminary assessment of the safety and immunogenicity of live cholera vaccine CVD103-HgR in healthy Thai adults. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3261–3264. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3261-3264.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosley, W. H. 1969. The role of immunity in cholera. A review of epidemiological and serological studies. Tex. Rep. Biol. Med. 27(Suppl. 1):227–241.

- 24.Mosley W H, Woodward W E, Aziz K M A, Rahman A S M M, Chowdhury A K M A, Ahmed A, Feeley J C. The 1968–1969 cholera-vaccine field trial in rural East Pakistan. Effectiveness of monovalent Ogawa and Inaba vaccines and a purified Inaba antigen, with comparative results of serological and animal protection tests. J Infect Dis. 1970;121:S1–S9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/121.supplement.s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neoh S H, Rowley D. The antigens of Vibrio cholerae involved in the vibriocidal action of antibody and complement. J Infect Dis. 1970;121:505–513. doi: 10.1093/infdis/121.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogawa Y, Lei P-S, Kováč P. Synthesis of eight glycosides of hexasaccharide fragments representing the terminus of the O-specific polysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O:1 serotype Inaba and Ogawa, bearing aglycons suitable for linking to proteins. Carbohydr Res. 1996;293:173–194. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(96)00202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierce N F, Reynolds H Y. Immunity to experimental cholera. I. Protective effect of humoral IgG antitoxin demonstrated by passive immunization. J Immunol. 1974;113:1017–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pike R M, Chandler C H. Serological properties of γG and γM antibodies to the somatic antigen of Vibrio cholerae during the course of immunization of rabbits. Infect Immun. 1971;6:803–809. doi: 10.1128/iai.3.6.803-809.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robbins J B, Schneerson R. Polysaccharide-protein conjugates: a new generation of vaccines. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:821–832. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robbins J B, Schneerson R, Szu S C. Perspective: hypothesis: serum IgG antibody is sufficient to confer protection against infectious diseases by inactivating the inoculum. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1387–1398. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szu S C, Gupta R, Robbins J B. Induction of serum vibriocidal antibodies by O-specific polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines for prevention of cholera. In: Wachsmuth I K, Blake P A, Olsvik O, editors. Vibrio cholerae and cholera. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 381–394. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tauxe R, Blake P, Olsvik O, Wachsmuth I K. The future of cholera: persistence, change and an expanding research agenda. In: Wachsmuth I K, Blake P A, Olsvik O, editors. Vibrio cholerae and cholera. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 443–453. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wasserman S S, Losonsky G A, Noriega F, Tacket C O, Castaneda E, Levine M M. Kinetics of the vibriocidal antibody response to live oral cholera vaccines. Vaccine. 1994;11:1000–1003. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodward W E. Cholera reinfection in man. J Infect Dis. 1971;123:61–66. doi: 10.1093/infdis/123.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]