Abstract

Previously we showed that lysates of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) inhibit lymphokine production by mitogen-activated human peripheral blood and lamina propria mononuclear cells. The aims of the present study were to determine whether EPEC-inhibitory factors have similar effects on murine lymphoid populations in order to further delineate the mechanisms of alteration of cytokine production. Preexposure to EPEC lysates inhibited mitogen-stimulated interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production by murine spleen cells, but IL-10 production was increased. The inhibition was not due to increased apoptosis and was not blocked by neutralizating antibodies against IL-10 or transforming growth factor β (TGF-β). EPEC lysates also inhibited mitogen-stimulated IL-2 and IFN-γ production by CD11b-depleted spleen cells, IL-2 and IL-4 production by intraepithelial and Peyer’s patch lymphocytes, IL-2 production by the human T-cell line Jurkat, and antigen-stimulated IL-2 production by murine spleen cells. Lysates obtained from Shiga-like toxin-producing E. coli, E. coli RDEC-1, Citrobacter rodentium, and an EPEC espB insertion mutant all inhibited IL-2 and IL-4 production by mitogen-stimulated lymphoid cells. In conclusion, lysates of EPEC and related bacteria directly inhibit cytokine production by lymphoid cells from multiple sites by a mechanism that does not increase apoptosis or result from secondary effects of IL-10 or TGF-β.

The gastrointestinal tract contains numerous immune effector and regulatory cells of lymphoid and myeloid origin that are thought to play a critical role in host defense against enteric infections. The function of these cells appears to be carefully regulated to prevent potentially deleterious immune responses against harmless products of digestion and the normal flora. The balance between the functions of host defense and immune tolerance in the gut immune system is thought to be mediated in part by production of regulatory cytokines by gut-associated lymphoid tissues (7, 18). This is illustrated by the spontaneous appearance of gastrointestinal inflammatory disease in a number of animals deficient in different cytokines, including interleukin (IL-10), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), and IL-2 (15, 16, 23). Numerous products of enteric flora positively regulate inflammatory responses; this subject was extensively reviewed elsewhere (9). In addition, products of enteric flora with negative regulatory effects have been identified in Salmonella typhimurium (2, 10), Helicobacter pylori (14), Vibrio cholerae (22, 26), and bovine viral diarrhea virus (1). Recently, we identified novel products of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) that inhibit cytokine production by human peripheral blood and intestinal lamina propria lymphocytes (12, 13). On the basis of these observations, we suggested the hypothesis that certain enteric bacterial products may alter immune homeostasis in the gastrointestinal tract through inhibition of regulatory cytokine production, which could contribute to bacterial pathogenesis. The aim of the present study was to determine whether the inhibitory products of EPEC affected murine lymphoid cells, which would permit further studies of the mechanisms of action, antigen specificity, and bacterial specificity of these inhibitory products. The results of these experiments indicate that products of certain related strains of bacteria have the potential to selectively regulate cytokine production by peripheral lymphocytes and gut-associated lymphoid tissues in both human and murine cells by mechanisms that appears to act directly on lymphocytes without increasing apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

BALB/cByJ mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor Maine), 6 to 8 weeks of age, were randomly divided into treatment groups. All mice were housed in the University of Maryland, Baltimore, laboratory animal facility. Food and water were available ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the University of Maryland, Baltimore, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bacterial strains and lysate production.

The bacterial strains used are listed in Table 1. Bacterial lysates were produced from 100 ml of Lennox L broth cultures grown at 37°C for 18 to 20 h with constant shaking. Bacteria were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS), and finally resuspended in 10 ml of PBS. This suspension was passed through a French press cell at 8,000 lb/in2. Protein concentrations of the lysates were determined with bicinchoninic acid protein assays (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Lysates were stored in single-use aliquots at −70°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Characteristic(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| EPEC 2348-69a | Serotype O111:NM | 5 |

| E. coli RDEC-1b | E. coli similar to EPEC, causes diarrhea in rabbits | 3 |

| STECa | EDL933; serotype O157:H7; formerly called enterohemorrhagic E. coli | 27 |

| E. coli UMD864a | Mutant of EPEC 2348-69 lacking functional espB | 6 |

| Citrobacter rodentium | Causes murine colonic hyperplasia, colitis, and attaching-and-effacing lesions; contains LEE; formerly called Citrobacter freundi biotype 4280 | 25 |

| E. coli JM109c | E. coli K-12 genetically engineered for molecular biology techniques (RecA− LacZ− rK− | 29 |

Obtained from Michael Donnenberg, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Obtained from Edgar Boedeker, Center for Vaccine Development, University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Obtained from Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.

Immunization.

Mice were injected subcutaneously at the base of the tail with 100 μg of chicken ovalbumin (OVA) (n = 9) or keyhole limpet hemacyanin (KLH) (n = 6) in 0.1 ml of complete Freund’s adjuvant (FA). Control mice were either injected with PBS in complete FA (n = 9) or not injected (n = 6). Mice immunized with KLH received a booster injection of 100 μg of KLH in 0.1 ml of incomplete FA after 3 weeks. Three of the OVA-immunized mice were each given booster injections containing 100 μg of OVA in 0.1 ml of incomplete FA at 3, 7, and 8 weeks after the initial injection.

Cell isolation.

The excised spleens were forced through wire screens (40 mesh), and the dissociated cells were collected in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.1 mg of gentamicin per ml (culture medium).

Small intestinal intraepithelial and Peyer’s patch lymphocytes (IEL and PP, respectively) were prepared as described previously (17). Briefly, the small intestine was excised and Peyer’s patches were removed and placed in ice-cold culture medium. The remaining intestine was cut longitudinally, washed three times in RPMI 1640, and cut into pieces 1 cm in length. The pieces were placed in a siliconized 50-ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 20 ml of Hanks balanced salt solution (without Ca2+ or Mg2+) supplemented with 10% FBS, 15 mM HEPES, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mg of gentamicin per ml (EDTA medium) and incubated on a shaker platform at 37°C for 20 min. The cells in the supernatant were harvested, and the remaining tissue pieces were again incubated in EDTA media for 20 min. The IEL obtained from the two incubations were pooled.

The PP were minced with scissors and placed in a siliconized 50-ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 20 ml of RPMI 1640 supplemented with purified collagenase (0.25 mg/ml), trypsin inhibitor (0.125 mg/ml), and DNase I (21 U/ml) (enzyme medium). The pieces were incubated on a shaker platform for 1 h at 37°C and then vortexed vigorously. The tissue was allowed to settle, and the supernatant was removed. Fresh enzyme medium was added to the tissue, and incubation continued as before for 30 to 60 min. The cells in the supernatant were washed three times with ice-cold RPMI 1640 and finally resuspended in ice-cold culture medium. The pooled cells were passed through a Percoll gradient (40%/100%), and the interface cells were removed, washed three times in ice-cold PBS, and resuspended in ice-cold culture medium.

Jurkat cell cultures.

The Jurkat cell line, clone E6-1, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.). Cultures were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.1 mg of gentamicin per ml and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Macrophage depletion.

Cells obtained from individual murine spleens were suspended in 10 ml of RPMI 1640 and treated with biotin-labeled anti-mouse CD11b (10 μg/ml; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) for 1 h at 22°C with constant gentle swirling. The cells were washed three times with PBS and suspended in 5 ml of PBS, and 2 mg of M-280 streptavidin-linked magnetic beads (Dynal, Lake Success, N.Y.) was added. The cells were incubated with the beads for 1 h at 22°C with constant gentle swirling. Cells expressing CD11b and bound to the magnetic beads were removed with a magnet. Cells remaining in the culture after five sequential exposures to the magnet were washed twice in PBS and finally suspended at a concentration of 1.5 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.1 mg of gentamicin per ml.

Neutralization of IL-10 and TGF-β.

Various concentrations of anti-murine IL-10 or TGF-β neutralizing antibodies (R & D Systems, Stillwater, Minn.) were added to cell cultures just prior to bacterial lysate exposure. Serial dilutions of the neutralizing antibodies were used, starting with a concentration twice the amount listed by the manufacturer as providing 100% neutralization in their assay for activity. The cultures were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and analyzed as described above.

In vitro exposure to bacterial lysates and stimulation with antigens or mitogens.

Cell cultures containing harvested murine cells or the Jurkat cell line were adjusted to 1.5 × 106 cells/ml in culture medium and incubated in 96-well round-bottom tissue culture plates, 200 μl/well, at 37°C with 5% CO2. Indicated cultures were preexposed or not to bacterial lysates (50 μg/ml) for 2 h prior to stimulation. Time zero was considered to be the time when the EPEC lysate was added to the cells. Cultured cells were stimulated with PMA (2.5 ng/ml) and PHA (5 μg/ml), OVA (200 μg/ml), or KLH (25 μg/ml) or not stimulated. The antigen and mitogen concentrations used were determined by titration. All treatments were done in duplicate, and all cultures were adjusted to an equal volume by adding culture medium. At specified times, cell culture supernatants were collected and either tested for cytokines immediately or stored in aliquots at −20°C and tested within 7 days. The frozen cytokine samples were not subjected to repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Quantitation of secreted cytokines.

Commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were used to measure human IL-2 (INCstar, Stillwater, Minn.) and murine IL-2 (R & D Systems and Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.), IL-4, IL-10 (R & D Systems), and gamma interferon (IFN-γ; Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.) concentrations in the cell culture supernatants. The manufacturer’s instructions for each ELISA were followed without modification. Each sample was run in at least duplicate wells, the optical density readings of the multiple wells were averaged, and standard curves were created by using the supplied cytokine standards.

Annexin V staining.

Murine splenic and Jurkat cell cultures were each randomly divided into groups, which were exposed to EPEC lysates (50 or 100 μg/ml) or not and stimulated or not with PMA (2.5 ng/ml) and PHA (5 μg/ml). After either 1 or 18 h, the cultures were harvested and stained. To identify cell surface changes that occur early in the apoptotic process, annexin V conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was obtained from Trevigen (Gaithersburg, Md.). The manufacturer’s instructions were followed without modification. Specifically, the concentration was adjusted to 1.5 × 105 cells/ml in the supplied binding buffer, and the cells were stained simultaneously with annexin-FITC (0.50 μg/ml) and propidium iodide (5 μg/ml). The stained cells were analyzed on an EPECS V flow cytometer (Coulter, Miami, Fla.).

Statistics.

The significance of differences between values was tested by using a nonparametric test, the Wilcoxon U or paired test as appropriate.

RESULTS

Bacterial lysates inhibit IL-2 secretion of mitogen-stimulated murine splenic cells.

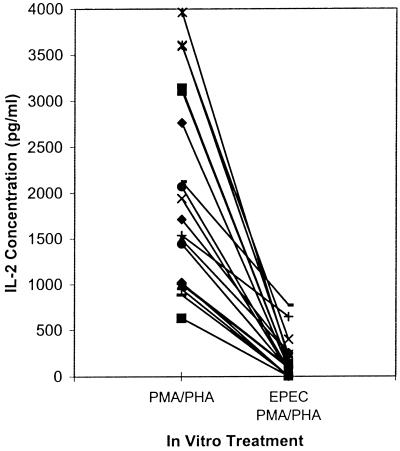

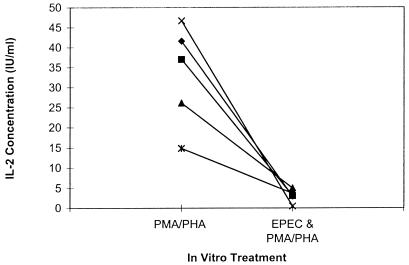

Previously we reported that in vitro exposure of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells to EPEC 2348-69 inhibited IL-2, IL-4, and IL-5 mRNA expression following subsequent mitogen stimulation (12, 13). To determine if murine models could be developed to further examine the inhibitory activity of EPEC, initial experiments were designed to determine if in vitro exposure to EPEC lysates inhibited IL-2 production of mitogen-stimulated murine splenic cells. Splenic cells were isolated from 20 mice and stimulated with PMA and PHA with or without preexposure to EPEC 2348-69 lysate. IL-2 concentration in the culture supernatant was measured after 48 h by ELISA. Compared to the respective non-EPEC-exposed cultures, IL-2 secretion was inhibited in all 20 cultures exposed to the EPEC lysate (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Bacterial lysates inhibit IL-2 secretion of mitogen-stimulated murine splenic cells. IL-2 concentrations in supernatants from BALB/c splenic cell cultures stimulated with PMA (2.5 ng/ml) and PHA (5 μg/ml) with or without preexposure for 2 h to French press lysates of EPEC 2348-69 (50 μg/ml) were measured by ELISA 46 h after stimulation. Values shown are means for duplicate cultures for each mouse (n = 20).

Exposure to EPEC does not induce increased apoptosis.

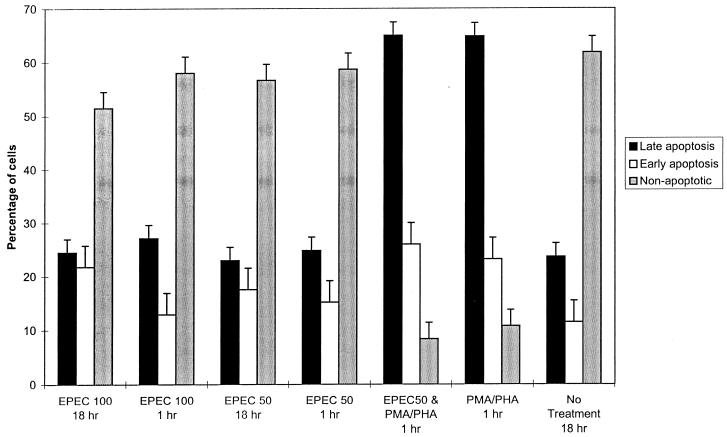

Because the decreased cytokine production could be attributable to decreased cell numbers due to the lysates inducing apoptosis, we stained the cells with annexin V and propidium iodide after exposure to different concentrations of the EPEC lysate for 1 or 18 h with and without stimulation with PMA and PHA. Annexin V binds phosphatidylserine, an inner membrane phospholipid, exposed on cells undergoing apoptosis (19, 28). Cells were divided into three categories based on their staining characteristics. They were considered to be in early apoptosis if annexin V was bound, to be in late apoptosis if intracellular propidium iodide staining was present, and to be nonapoptotic if neither stain was detected. Exposure to 50 or 100 μg of EPEC lysate per ml alone for either 1 or 18 h did not increase the percentage of apoptotic cells compared to analogous cultures not treated with EPEC (Fig. 2). Cultures treated with PMA and PHA for 1 or 18 h had nearly a threefold increase in the percentage of cells in late apoptosis, whether or not the cells were pretreated with EPEC lysates (Fig. 2; data for 18 h not shown since they were similar to data for 1 h). Therefore, EPEC lysates do not appear to decrease cytokine production by inducing apoptosis.

FIG. 2.

Exposure to EPEC does not induce increased apoptosis. Percentages of cells in various stages of apoptosis are indicated. Cells were stained with annexin V-FITC (early apoptotic) and propidium iodide (late apoptotic) and analyzed by flow cytometry. BALB/c splenic cell cultures were exposed to either 50 μg (EPEC 50) or 100 μg (EPEC 100) of EPEC lysate per ml for 1 or 18 h. After a 2-h exposure to 50 mg of EPEC lysate per ml or to PBS, indicated cultures were stimulated with PMA and PHA and stained 1 h after mitogen stimulation. Values shown are means of four replicate cultures obtained from two mice (± standard deviation).

IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ secretion by mitogen-stimulated spleen cells preexposed to EPEC lysate.

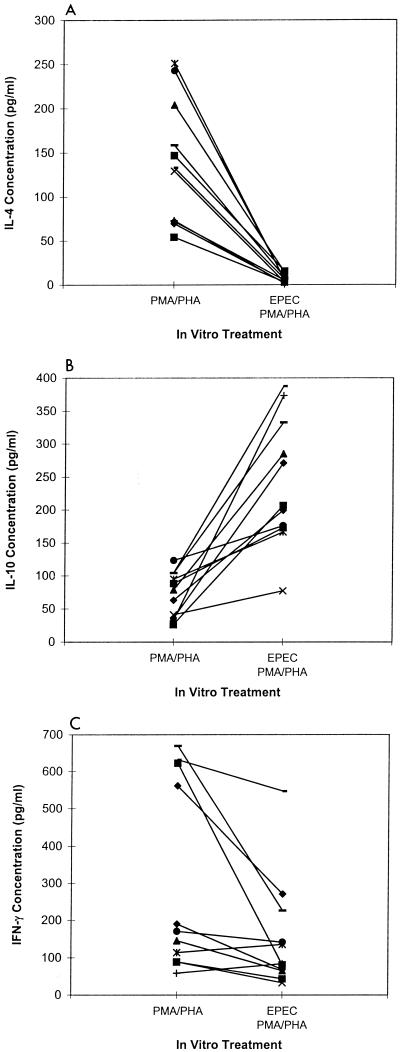

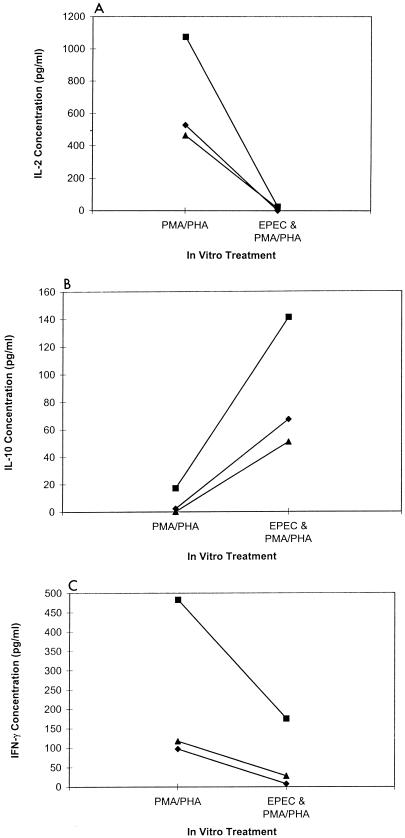

To determine if preexposure to EPEC lysates differentially affected the secretion of other cytokines, we measured IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ concentrations in 11 different mitogen-stimulated murine splenic cell cultures with and without prior exposure to EPEC lysates. Secretion of IL-4 was inhibited (Fig. 3A, P < 0.01) and secretion of IL-10 was enhanced (Fig. 3B, P < 0.01) in all 11 cultures preexposed to EPEC lysates. IFN-γ secretion was inhibited in 9 of 11 cultures compared to nonexposed cultures (Fig. 3C, P < 0.01). Therefore, it does not appear that the inhibitory activity of EPEC is limited to only one cytokine, and secretion of IL-10, a potent inhibitor of cytokine production, was increased following exposure to EPEC lysates.

FIG. 3.

IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ secretion by mitogen-stimulated spleen cells preexposed to EPEC lysates. Shown are IL-4 (A), IL-10 (B), and IFN-γ (C) concentrations in BALB/c splenic cell cultures after mitogen stimulation with and without exposure to EPEC lysates as described for Fig. 1. Values shown are means for duplicate cultures for each mouse (n = 11).

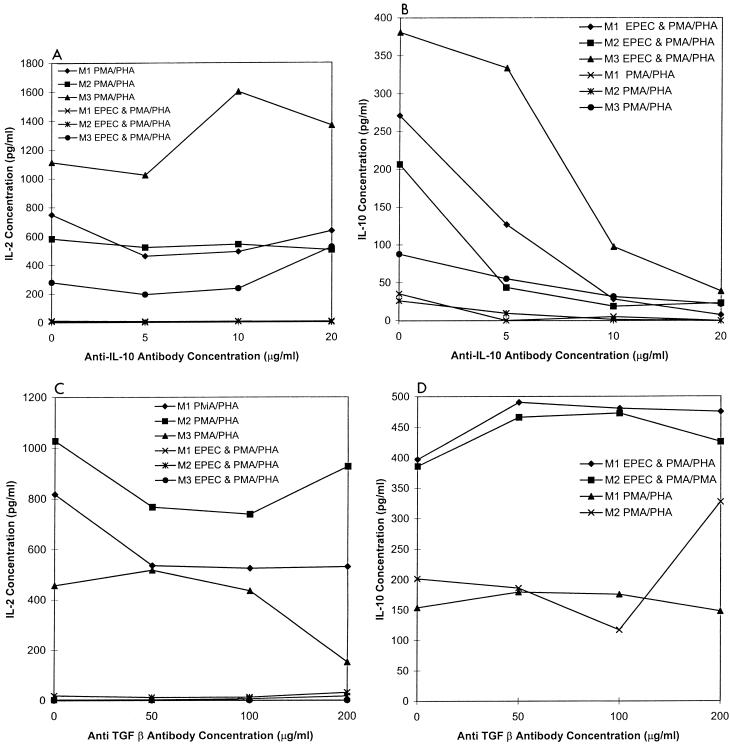

EPEC-inhibitory activity is independent of IL-10 and TGF-β.

IL-10 and TGF-β are two regulatory cytokines known to inhibit IL-2 and IL-4 secretion. To determine if IL-10 or TGF-β is required for the inhibition of cytokine secretion following exposure to EPEC lysates, specific neutralizing antibodies were added to the cell cultures. Splenic cell cultures from three mice were each treated with increasing concentrations of anti-IL-10 antibodies and evaluated for IL-2 and IL-10 secretion following EPEC exposure and mitogen stimulation. Blocking IL-10 in the cultures did not appear to influence the IL-2 concentration in the mitogen-stimulated cell cultures (Fig. 4A). As expected, cultures treated with increasing concentrations of anti-IL-10 had decreasing concentrations of IL-10 (Fig. 4B). Thus, inhibition of IL-2 production by EPEC lysates does not appear to be dependent on production of IL-10.

FIG. 4.

EPEC-inhibitory activity is independent of IL-10 and TGF-β. Shown are IL-2 (A and C) and IL-10 (B and D) concentrations of mitogen-stimulated BALB/c splenic cultures exposed to increasing concentrations of anti-IL-10 (A and B) and anti-TGF-β (C and D) with and without preexposure to EPEC lysates as described for Fig. 1. Cells were obtained from three mice (M1, M2, and M3). Values shown are means of duplicate replicate cultures for each mouse.

In similar experiments, increasing concentrations of neutralizing antibodies for murine TGF-β were added to cultures prior to EPEC exposure and mitogen stimulation. Reducing the concentration of TGF-β appeared to have no effect on the concentration of IL-2 or IL-10 in the mitogen-stimulated murine spleen cultures exposed to EPEC (Fig. 4C and D). In all cultures, the concentration of IL-2 was decreased and that of IL-10 was increased. Therefore, the quantity of IL-2 and IL-10 in the culture supernatants depended on whether the cultures had been exposed to EPEC lysates prior to mitogen stimulation and not on the IL-10 or TGF-β concentration.

Depletion of CD11b-expressing cells.

Macrophages can secrete IL-10, IFN-γ, and numerous other cytokines. To better evaluate if EPEC was acting directly on lymphocytes or if other cells were involved, macrophages and other CD11b (Mac-1)-expressing cells were depleted from cultures prior to EPEC exposure. IL-2 and IFN-γ secretions were markedly decreased and secretion of IL-10 was increased in CD11b-depleted cultures after exposure to EPEC lysates and subsequent mitogen stimulation (Fig. 5). Therefore, CD11b cells do not appear to be necessary for the EPEC lysates to inhibit IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion, and the increased IL-10 secretion is not solely due to macrophage stimulation.

FIG. 5.

Depletion of CD11b-expressing cells did not change the effect of EPEC lysate on cytokine secretion. IL-2 (A), IL-10 (B), and IFN-γ (C) secretion of BALB/c splenic cultures depleted of CD11b-expressing cells and stimulated with PMA and PHA was determined following exposure or not to EPEC lysate (50 μg/ml). CD11b-expressing cells were removed by using magnetic beads and anti-CD11b antibody. Results from cultures made from three separate mice are shown. Values shown are means for duplicate determinations for each mouse.

IL-2 secretion of Jurkat cells inhibited by EPEC lysates.

To further evaluate if the EPEC lysates are capable of directly inhibiting lymphocyte cytokine secretion, we measured IL-2 secretion of mitogen-stimulated Jurkat cells, a human T-cell leukemia, exposed or not to EPEC lysates. IL-2 secretion of mitogen-stimulated cells was decreased following EPEC exposure (Fig. 6). Therefore, some factor or combination of factors in the EPEC lysate is capable of acting directly on T cells to inhibit cytokine secretion. Results for annexin staining of Jurkat cell cultures were very similar to that shown above for murine spleen cultures. Compared to control cultures, increased apoptosis was observed only when PHA and PMA were added to the cultures (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

IL-2 secretion of mitogen-stimulated Jurkat cells preexposed or not to EPEC lysates (50 μg/ml). Exposure to EPEC and mitogen stimulation were as described for Fig. 1. IL-2 concentration in cell culture supernatants was measured by ELISA 16 h after mitogen stimulation. Values are means of duplicate cultures for each experiment (n = 5).

IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10 secretion by mitogen-stimulated PP and IEL.

To determine if lymphocytes isolated from different regions of the immune system were equally susceptible to the EPEC factor, we isolated PP and IEL from two mice and cultured the lymphocytes. Mitogen-stimulated PP and IEL cultures each treated with EPEC lysates had lower IL-2 and IL-4 secretion, but no significant change in IL-10, compared to cultures not treated with EPEC (Table 2). Thus, the effect of EPEC exposure on mucosal immune cell cytokine production was similar to the effect observed with splenic cells.

TABLE 2.

Cytokine secretion of murine PP or IEL following mitogen stimulation with and without preexposure to EPEC lysatesa

| Expt no. | Mean concn (pg/ml) from duplicate wells

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2

|

IL-4

|

IL-10

|

||||

| − | + | − | + | − | + | |

| 1 | ||||||

| PP | 2,174 | 286 | 366 | 28 | 131 | 102 |

| IEL | 288 | 71 | 17 | 8 | <4 | 22 |

| 2 | ||||||

| PP | >2,890 | 1,804 | 244 | 60 | 182 | 142 |

| IEL | 420 | 111 | <2 | <2 | <4 | 16 |

Cells were isolated and preexposed (+) or not (−) to 50 μg of EPEC lysate protein per ml for 2 h and then stimulated with PMA and PHA. Supernatants were collected 46 h after stimulation, and cytokines were quantitated by ELISA.

IL-2 and IL-10 secretion by antigen-stimulated spleen cells preexposed to EPEC lysate.

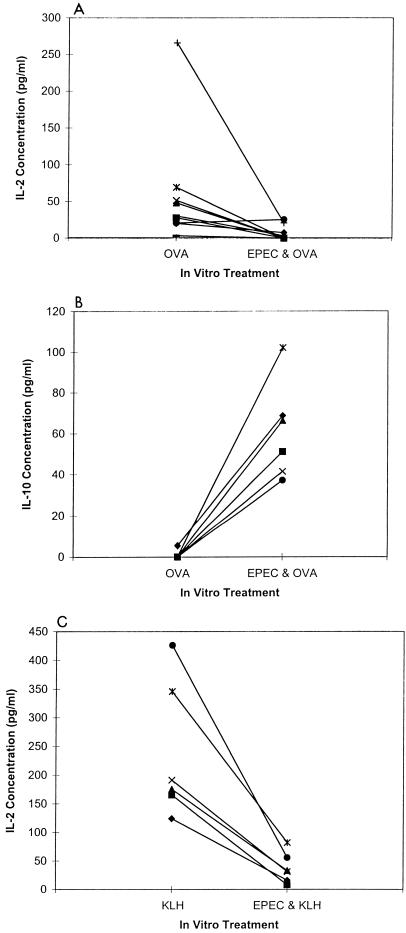

Because mitogen stimulation may not effectively mimic physiological conditions, we determined if levels of antigen-specific IL-2 and IL-10 production were affected by preexposure to EPEC lysates. Mice were immunized with either OVA or KLH, and the harvested splenic cells were either exposed or not exposed to EPEC lysates and stimulated with the appropriate antigen.

Preexposure to EPEC lysates inhibited IL-2 secretion in eight of nine OVA-stimulated (P < 0.05) and six of six KLH-stimulated (P < 0.05) cultures (Fig. 7A and C) and increased IL-10 secretion in nine of nine OVA-stimulated cultures (Fig. 7B, P < 0.01). IL-10 secretion in the KLH mice was not measured. Therefore, IL-2 secretion is decreased and IL-10 secretion is increased in antigen- or mitogen-stimulated cultures preexposed to EPEC lysates.

FIG. 7.

Preexposure to EPEC lysate inhibits IL-2 secretion but enhances IL-10 secretion by antigen-stimulated murine splenic cells. Mice were immunized with OVA (n = 9) (A and B) or KLH (n = 6) (C) by subcutaneous injection at the base of the tail with 100 μg of each antigen in 0.1 ml of complete FA. Spleens were harvested from the mice, and the cell cultures were stimulated with OVA (200 μg/ml) or KLH (25 μg/ml) with or without a 2-h preexposure to EPEC lysate (50 μg/ml). IL-2 (A and C) and IL-10 (B) concentrations in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA 46 h after antigen stimulation. The high-responder OVA-stimulated mouse (+) received three booster injections each containing 100 μg of OVA in incomplete FA. Each value is a mean of duplicate replicate cultures for each mouse.

Additional pathogenic bacterial strains modify cytokine secretion.

To determine if the inhibitory activity of EPEC was shared by other related bacteria, lysates of Shiga-like toxin-producing E. coli (STEC; O:157), RDEC-1, and Citrobacter rodentium were tested. These bacterial strains each contain a genomic region homologous to the EPEC locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) (8, 11, 20, 25, 30). Preexposure to any of the strains markedly inhibited IL-2 and IL-4 secretion but increased IL-10 secretion by mitogen-stimulated spleen cells (Table 3). The effect of bacterial lysates on IFN-γ secretion was variable. Therefore, the inhibitory activity associated with EPEC is shared by related bacterial species.

TABLE 3.

Cytokine secretion of mitogen-stimulated murine splenic cells pretreated with lysates from different E. coli strainsa

| Cytokine | Mouse | Concn (pg/ml) after exposure to:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPEC | STEC | RDEC-1 | C. rodentium | UMD864 espB mutant | No bacterial lysate | ||

| IL-2 | 1 | <3 | 60 | <3 | 121 | <3 | 1,019 |

| 2 | <3 | 41 | <3 | 102 | <3 | 629 | |

| 3 | <3 | <3 | <3 | 10 | <3 | 429 | |

| 4 | <3 | <3 | <3 | 62 | <3 | 400 | |

| IL-4 | 1 | <2 | 9 | 3 | 12 | <2 | 70 |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 11 | <2 | 54 | |

| 3 | 6 | <2 | <2 | 2 | <2 | 52 | |

| 4 | <2 | <2 | <2 | 18 | <2 | 64 | |

| IL-10 | 1 | 271 | 362 | 281 | 159 | 485 | 37 |

| 2 | 388 | 415 | 157 | 168 | 179 | 6 | |

| 3 | 128 | 119 | 79 | 153 | 114 | 6 | |

| IFN-γ | 1 | 120 | 281 | 60 | 67 | 129 | 560 |

| 2 | 81 | 203 | 31 | 826 | 32 | 621 | |

| 3 | 350 | 424 | 87 | 660 | 166 | 332 | |

| 4 | 226 | 275 | 97 | 554 | 62 | 352 | |

Splenic cells were isolated and preexposed to 50 μg of each bacterial lysate protein per ml for 2 h and then stimulated with PMA and PHA. Supernatants were collected 22 h after stimulation, and cytokines were quantitated by ELISA. Values represent means of duplicate cultures for each mouse for each condition.

Inhibitory activity is not related to espB.

All of the bacterial strains tested contain the LEE region, which includes espB, a gene known to code for a factor capable of stimulating NF-κB (24). Therefore, we tested lysates of the insertion mutant UMD864 to determine if a functional espB was required for inhibitory activity. In all four murine splenic cell cultures tested, the UMD864 lysates inhibited IL-2 secretion as effectively as the wild-type EPEC (Table 3). Therefore, although the inhibitory activity may be associated with the LEE region, the espB gene product is not involved.

DISCUSSION

The experiments described here considerably extend our previous observations that lysates of EPEC modify cytokine production by human peripheral blood and intestinal lamina propria lymphocytes. First, in this study we observed similar effects on cytokine production with murine lymphoid populations, although the mouse is not considered to be a host susceptible to diarrheal disease from human EPEC isolates. Murine lymphoid cells pretreated with EPEC lysates and then stimulated with mitogens demonstrated decreased production of IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-γ but increased production of IL-10. The observation that the effect of EPEC lysates was not restricted solely to human cells allowed for further experimentation to be carried out in the mouse that cannot readily be accomplished in humans. Antigen-specific lymphokine production by immunized (with OVA and KLH) mice was also inhibited. Furthermore, similar effects were seen with murine PP and IEL populations, both of which could be more relevant populations to study for enteric pathogens and are difficult to obtain from humans. The fact that similar effects on both human and murine lymphoid cells are observed suggests that although the important steps in pathogenesis of EPEC diarrheal disease may be restricted by the well-characterized specific interactions of EPEC with gastrointestinal epithelial cells (4), the mechanisms by which EPEC lysates affect lymphoid cells may be different and not require these selective interactions.

The observations reported here also provide further information regarding potential mechanisms by which EPEC lysates modify cytokine production by lymphoid cells. Macrophage depletion did not alter the ability of lysates to inhibit IL-2, IL-4, or IFN-γ production or augment IL-10 production. EPEC lysates markedly inhibited IL-2 production by mitogen-stimulated Jurkat T cells, a human T-cell line, indicating that the inhibitory effect does not necessarily require the presence of another cell type. Since high concentrations of neutralizing antibodies to IL-10 or TGF-β did not eliminate the effect of EPEC lysates on inhibition of IL-2 production, the results suggest that decreased IL-2 production is not due to a secondary inhibitory effect of high levels of IL-10 or TGF-β. Finally, and somewhat surprisingly, there was no evidence that the bacterial products caused inhibition by the trivial mechanism of increased cell death, since there was no evidence of increased apoptosis in cells exposed to the lysates.

As indicated in the introduction, inhibitory effects on cytokine production have been found in studies using factors isolated from other pathogens (1, 2, 10, 14, 22, 26). In these prior reports, as in ours, the specific factor or factors causing inhibition remain undefined. The preparations used in the present experiments clearly contain complex mixtures of bacterial products, and the observed effects on cytokine production may represent the summation of both stimulatory and inhibitory effects mediated by different specific bacterial products. Although the bacterial preparations are complex, they may nonetheless provide insights into pathological conditions in vivo. We have demonstrated that these regulatory effects extend to other related bacterial species, such as STEC, the E. coli pathogen RDEC-1, which causes attachment-and-effacing lesions and diarrheal disease in young rabbits, and C. rodentium, which causes colitis in young mice. There has been considerable interest recently in the LEE pathogenicity island of EPEC (20, 21). In previous studies (12, 13) and this study, we tested a number of EPEC strains containing inactivating mutations within the LEE region, including eaeA and espB, and found that these mutants retained inhibitory activity. Furthermore, we obtained a cosmid clone of EPEC that retained inhibitory activity when expressed in E. coli but does not have homology to the LEE region based on preliminary sequencing of the clone (unpublished observations). Thus, the cytokine regulatory activity found in EPEC, and present in other, related bacterial strains, could represent a novel biological and potentially pathogenic mechanism of bacterial pathogenesis. Selective inhibition of specific cytokines such as IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-γ by enteric bacterial products could play an additional role in disease pathogenesis beyond that due to the primary interaction of bacteria with target epithelial cells. Evidence in support of this hypothesis is suggested from murine models of cytokine gene inactivation, such as the IL-2 knockout mouse that spontaneously develops colonic inflammation and ulceration (23). It has been suggested that cytokine dysregulation occurring in this and other animal models of inflammatory bowel disease could be an important contributor to gastrointestinal inflammation. The results of the present study indicate that it may be possible to further examine the relevance of bacterial factors that modulate cytokine production by using murine models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant DK47708 from the National Institutes of Health and by the Baltimore Veterans Administration Medical Center. C.M. was supported by a research fellowship from The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

We thank Michael Donnenberg for providing the EPEC and STEC bacterial strains and Edgar Boedeker for providing the RDEC-1 strain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler H, Jungi T W, Pfister H, Strasser M, Sileghem M, Peterhans E. Cytokine regulation by virus infection: bovine viral diarrhea virus, a flavivirus, downregulates production of tumor necrosis factor alpha in macrophages in vitro. J Virol. 1996;70:2650–2653. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2650-2653.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai T, Matsui K. A purified protein from Salmonella typhimurium inhibits high-affinity interleukin-2 receptor expression on CTLL-2 cells. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;17:155–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantey J R, Blake R K. Diarrhea due to Escherichia coli in the rabbit: a novel mechanism. J Infect Dis. 1977;135:454–462. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Finlay B B. Interactions between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and host epithelial cells. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:109–114. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnenberg M S, Donohue-Rolfe A, Keusch G T. Epithelial cell invasion: an overlooked property of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) associated with the EPEC adherence factor. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:452–459. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnenberg M S, Yu J, Kaper J B. A second chromosomal gene necessary for intimate attachment of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4670–4680. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4670-4680.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiocchi C, Podolsky D K. Cytokines and growth factors in inflammatory bowel disease. In: Kirsner J B, Shorter R G, editors. Inflammatory bowel disease. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1995. pp. 252–280. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankel G, Candy D C A, Everest P, Dougan G. Characterization of the C-terminal domains of intimin-like proteins of enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, Citrobacter freundii, and Hafnia alvei. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1835–1842. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1835-1842.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson B, Poole S, Wilson M. Bacterial modulins: a novel class of virulence factors which cause host tissue pathology by inducing cytokine synthesis. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:316–341. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.316-341.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang D, Schwacha M G, Eisenstein T K. Attenuated Salmonella vaccine-induced suppression of murine spleen cell responses to mitogen is mediated by macrophage nitric oxide: quantitative aspects. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3786–3792. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3786-3792.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karaolis D K R, McDaniel T K, Boedeker E C. Abstracts of the 96th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1996. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. Cloning of the RDEC-1 locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) and functional analysis of its phenotype, abstr. B90; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klapproth J-M, Donnenberg M S, Abraham J M, James S P. Products of enteropathogenic E. coli inhibit lymphokine production by gastrointestinal mucosal lymphocytes. Am J Physiol. 1996;34:G841–G848. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.5.G841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klapproth J-M, Donnenberg M S, Abraham J M, Mobley H L T, James S P. Products of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli inhibit lymphocyte activation and lymphokine production. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2248–2254. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2248-2254.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knipp U, Birkholz S, Kaup W, Opferkuch W. Partial characterization of a cell proliferation-inhibiting protein produced by Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3491–3496. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3491-3496.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhn R, Lohler J, Renick D, Rafewsky K K, Muller W. Interleukin-10 deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkarni A B, Huh C G, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders K C, Roberts A B, Sporn M B, Ward J M, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor B1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefrancois L, Lycke N. Isolation of mouse small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, Peyer’s patch, and lamina propria cells. In: Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1995. pp. 3.19.1–3.19.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDermott R P. Alterations in mucosal immune system in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Med Clin North Am. 1994;78:1207–1231. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin J S, Reutelingsperger C P M, McGahon A J, Rader J, van Schei R C A C, LaFace D M, Green D R. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1545–1556. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDaniel T K, Kaper J B. A cloned pathogenicity island from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli confers the attaching and effacing phenotype of E. coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:399–407. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2311591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munoz E, Zubiaga A M, Merrow M, Sauter N P, Huber B T. Cholera toxin discriminates between T helper 1 and 2 cells in T cell receptor mediated activation: role of cAMP in T cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 1990;172:95–103. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadlack B, Merz H, Schorle H, Schimpl A, Feller A C, Horak I. Ulcerative colitis like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin 2 gene. Cell. 1993;75:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savkovic S D, Koutsouris A, Hecht G. Activation of NF-kappaB in intestinal epithelial cells by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:c1160–c1167. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shauer D B, Falkow S. The eae gene of Citrobacter freundii biotype 4280 is necessary for colonization in transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Infect Immun. 1993;65:2486–2492. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4654-4661.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuruta L, Lee H-J, Masuda E S, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Arai N, Arai K-I, Yokota T. Cyclic AMP inhibits expression of the IL-2 gene through the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NF-AT) site, and transfection of NF-AT cDNAs abrogates the sensitivity of EL-4 cells to cyclic AMP. J Immunol. 1995;154:5255–5264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tziori S, Karch H, Wachsmuth K I. Role of a 60-megadalton plasmid and Shiga-like toxins in the pathogenesis of infection caused by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3117–3125. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3117-3125.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vermes I, Haanen C, Steffen-Nakken H, Reutelingsperger C P M. A novel assay for apoptosis. Flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J Immunol Methods. 1995;184:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00072-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13am18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J, Kaper J B. Cloning and characterization of the eae gene of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:411–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]