Summary

Advances in gene editing, in particular CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), have enabled depletion of essential cellular machinery to study the downstream effects on bacterial physiology. Here, we describe the construction of an ordered E. coli CRISPRi collection, designed to knock down the expression of 356 essential genes with the induction of a catalytically inactive Cas9, harbored on the conjugative plasmid pFD152. This mobile CRISPRi library can be conjugated into other ordered genetic libraries to assess combined effects of essential gene knockdowns with non-essential gene deletions. As proof of concept, we probed cell envelope synthesis with two complementary crosses: (1) an Lpp deletion into every CRISPRi knockdown strain and (2) the lolA knockdown plasmid into the Keio collection. These experiments revealed a number of notable genetic interactions for the essential phenotype probed and, in particular, showed suppressing interactions for the loci in question.

Keywords: CRISPRi, Escherichia coli, genomic screening, gene essentiality, lipoprotein transport, Lpp

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A collection of 356 conjugative CRISPRi constructs targeting E. coli essential genes

-

•

Fitness of CRISPRi mutants can be assessed in microbial colony arrays

-

•

CRISPRi plasmids can be introduced into arrayed genomic collections by conjugation

-

•

Enables rapid high-density genetic interaction screening with essential processes

Motivation

Ordered collections of precise gene deletions in E. coli and other model microbes have proven to be invaluable resources to study gene dispensability in different environmental and genetic contexts. The dispensability of canonically essential genes, however, has been largely unstudied in such contexts. This work presents methodology for conducting genetic interaction studies with essential genes in E. coli by conjugating mobile CRISPRi constructs into gene deletion strains or into ordered genomic deletion collections such as the Keio collection. Interactions uncovered with such genetic screens inform on paradoxes in gene essentiality, which inform on the complexity of bacterial systems and can be leveraged in antibiotic discovery efforts.

Rachwalski et al. describe methodology for conducting genetic interaction studies with essential processes in E. coli using conjugative CRISPRi plasmids. High-throughput conjugation in microbial colony arrays allows for the introduction of an individual CRISPRi plasmid into ∼4,000 non-essential gene deletion strains in parallel, providing insight into the effects of perturbing an essential process in distinct genetic backgrounds. This approach can be used to better understand the complexity of bacterial cell systems and to design unconventional phenotypic screens for antimicrobial drug discovery.

Introduction

Essential genes are defined as those that are required for the survival of an organism under normal growth conditions. The environmental and genetic context of a bacterium will establish which biological processes are required for growth and survival1,2; gene essentiality is not a binary determination. In Escherichia coli, approximately 300–400 genes have been identified as being essential for growth in standard laboratory media using a variety of approaches.3,4,5,6 These genes perform vital functions required for bacterial survival and are thereby sought-after targets for antibacterial drug discovery efforts.7 Indeed, patterns and paradoxes in gene dispensability offer profound insight into gene function and can be leveraged for small-molecule screens that search for novel antibacterial compounds.8,9,10

An important tool to study the dispensable gene set in E. coli is the Keio collection of ∼4,000 gene deletion strains.4 The Keio collection has been extensively screened to identify the environmental conditions, for example, different growth media and chemical stressors, where canonically non-essential genes are rendered essential for E. coli growth.11,12,13 Likewise, millions of unique double deletion strains have been generated with the Keio collection and screened using synthetic genetic array technology to uncover genetic contexts where genes become unexpectedly essential.14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 In contrast, there is great difficulty in performing such large-scale gene-gene interaction assays that include essential processes in E. coli. Chemical and antibiotic probes are often used to investigate the effects of perturbing essential processes in different genetic backgrounds, in what are described as “chemical genomics” screens.11,12,23,24 Other genetic-based approaches, including the creation of temperature-sensitive mutants25,26,27 and generating deletions of genes in strains where a second inducible copy of the gene is present in trans,28 have also been used to perturb essential functions in bacteria. Unfortunately, existing chemical probes target a small subset of essential biology or work only in bacterial strains with permeabilized membranes or deficient efflux systems, and many genetics approach are not scalable to experiments with large ordered genetic collections such as the Keio collection. As such, similar to synthetic genetic arrays for dispensable genes, a genetics-based approach to disrupt essential genes in existing mutant collections would be highly advantageous to the study of genetic interactions with the essential genome.

Recently, focus has shifted to the use of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) to study the effects of perturbing essential genes and processes.29,30 CRISPRi enables inducible and titratable knockdown of gene expression using a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9), which is guided to a target gene by a 20-nt single-guide RNA sequence (sgRNA), thereby blocking the transcription of nascent mRNA.29 The versatility of CRISPRi has enabled investigations of gene essentiality in E. coli5 and other non-model microbes.31 The depth of E. coli annotation as a model microbe32 makes it ideal for studying biological nuances using genetic tools. In E. coli, genome-wide CRISPRi fitness screens are commonly conducted using pooled collections of sgRNAs.5,33,34,35,36 In these screens, gene knockdown by CRISPRi is induced in the pooled collection, which is then grown for a pre-determined number of generations before the relative abundance of different sgRNAs is quantified by next-generation sequencing. Pooled approaches have also been used to conduct gene-gene interaction studies with E. coli deletion strains.37 However, this approach requires the de novo construction of a gene deletion in a genetic background expressing a chromosomal dCas9 and is thereby not immediately compatible with existing arrayed genomic collections such as the Keio collection.4 Alternatively, ordered collections can be screened for individual strain fitness without worrying about cross-feeding and other phenomena often observed with pooled mutant screening approaches.24,38 Screening ordered collections also allows for investigating the effects of knocking down an individual gene on bacterial cell physiology—for instance changes in cell morphology,39,40 the cellular metabolome,41,42 or the cellular proteome.42,43 While an ordered E. coli CRISPRi collection has been published recently by Silvis et al.,39 the fitness screening was conducted using a pooled version of the collection, and the nature of the IPTG promoter controlling expression of the sgRNAs resulted in leaky expression and observed growth defects of strains in the absence of inducer.

Here, we describe an ordered E. coli CRISPRi collection of 356 sgRNAs targeting essential genes built on the conjugative plasmid pFD152.44 The methodology, conducted using colonies arrayed on solid agar, revealed a dose-dependent reduction in strain fitness as we increased concentrations of the dCas9 inducer anhydrotetracycline (aTc) without any detectable growth defects in the absence of inducer. Further, we were able to rapidly and efficiently move our collection into any genetic background of interest by high-throughput conjugation, allowing for the interrogation of genetic interactions between the dispensable and indispensable genome of E. coli K-12. As a proof of principle, we conjugated our CRISPRi collection into a strain deleted for gene lpp, encoding Braun’s lipoprotein. Lpp is the most prevalent lipoprotein in the cell, and it has well-characterized synthetic viable interactions with the essential genes involved in lipoprotein transport.45,46 As expected, we found that CRISPRi constructs targeting essential genes involved in lipoprotein processing and transport (lnt and lolABC) showed considerably less growth inhibition in E. coli Δlpp. In line with this observation, we also demonstrated that conjugating pFD152:lolA into the Keio collection of ∼4,000 deletion strains identified Δlpp as one of the strongest suppressors of growth inhibition resulting from knocking down lolA expression. The platform has the potential to enhance our understanding of the biology underpinning essential processes in E. coli and can provide biological insights to design unconventional screening platforms aimed at identifying novel chemical inhibitors of essential processes.

Results

Creation of an arrayed mobile CRISPRi library on the pFD152 backbone

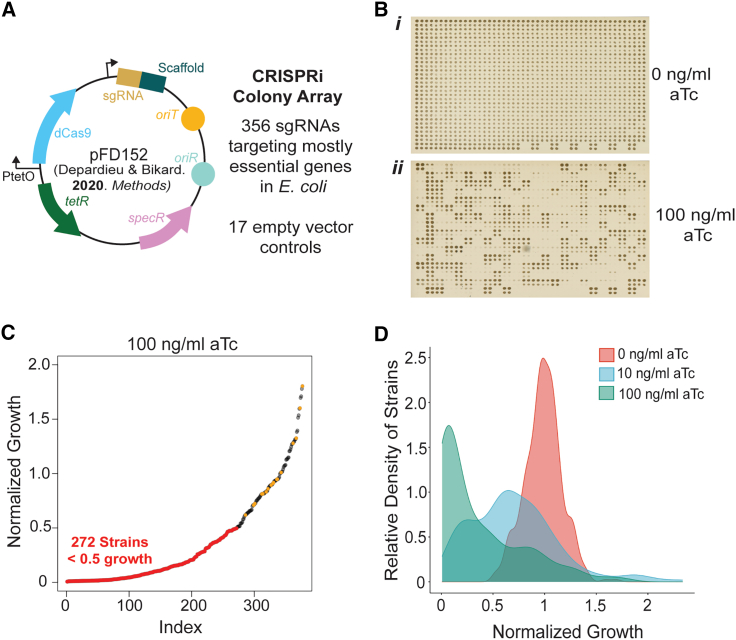

To facilitate genetic interaction studies for the essential genes of E. coli, we sought to create a collection of essential gene knockdowns constructed on a mobile CRISPRi plasmid using the recently published pFD152 vector.44 CRISPRi knockdown by pFD152 is inducible with anhydrotetracycline (aTc), which tightly controls the expression of dcas9 allowing for titratable silencing of gene expression.44 Additionally, pFD152 contains a constitutively expressed sgRNA, an RP4 origin of transfer that enables rapid conjugation into target strains, an origin of replication compatible with most of the commonly used plasmids in E. coli, and a spectinomycin selectable marker that is distinct from those commonly used in existing E. coli ordered deletion collections (Figure 1A). Importantly, expression of dcas9 from pFD152 has been optimized to alleviate non-specific off-target toxicity commonly observed with overexpressing dcas9 in E. coli.34,47,48 We used the CRISPRbact tool to design sgRNAs that minimize off-target binding commonly seen with sgRNAs in CRISPRi assays.34,35 We then introduced these sgRNAs into pFD152 using Golden Gate assembly44 and confirmed all sequences of the sgRNAs by Sanger sequencing. A comprehensive list of all 356 sgRNAs in our collection can be found in Table S1. Of the 356 genes represented in our collection, 353 were selected based on having an essential classification in a recent transposon sequencing survey of gene essentiality,3 and three non-essential genes were included as controls (waaU, lpxL, and bioA). Strains harboring sgRNAs targeting specific genes were arrayed at 384-density with 17 randomly dispersed strains carrying the pFD152 empty vector as a control, which has a 20-nt spacer sequence in lieu of a gene-specific sgRNA (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Overview of the E. coli mobile arrayed CRISPRi collection

(A) The previously published conjugative CRISPRi plasmid, pFD152,44 contains all required components for anhydrotetracycline (aTc)-inducible gene silencing in E. coli. 356 sgRNAs targeting essential genes were cloned into pFD152, validated by Sanger sequencing, and transformed into WT E. coli BW25113 and the conjugative donor strain E. coli MFDpir. Transformants were arrayed along with 17 strains carrying an empty vector that served as controls.

(B) Shown are images of the CRISPRi collection grown at high-density in a colony array in the absence (i) or in the presence of (ii) aTc. Shown is an array grown at 1,536 colony density on LB agar wherein each strain was grown in technical quadruplicate. Empty positions at the bottom right of the plate represent control wells lacking bacteria.

(C) A rank-ordered plot of mutant growth at 100 ng/mL aTc on LB agar. 272 strains in the CRISPRi array demonstrated a substantial growth defect (normalized growth <0.5) upon CRISPRi induction. Empty vector controls are represented by points labeled in orange.

(D) A density plot representing the distribution of growth of the CRISPRi collection at different aTc concentrations on LB agar. Collection-wide growth inhibition was dose dependent on concentration of inducer.

When grown in the presence of aTc, which induces CRISPRi knockdown, a growth defect was observable for a large portion of our collection (Figure 1B). With 100 ng/mL aTc added to the growth media, 272 from the 356 strains showed at least a 50% reduction in growth (Figure 1C). We screened the CRISPRi collection for growth inhibition in both rich (LB) and minimal (MOPS minimal) microbiological media at varying aTc concentrations and observed a dose-dependent growth defect (Figure 1D; Table S1A) while maintaining consistency between screening replicates (Figure S1A). Importantly, we do not see growth inhibition with the empty vector at any concentration of inducer screened (Figure S1B). Similarly, growth inhibition was not observed for the sgRNAs targeting the three non-essential genes that were included as controls, while we observed varying sensitivity to aTc for strains targeting essential genes (Figure S1B). We note that at the highest concentration of inducer tested, 289 and 274 of the 356 CRISPRi constructs caused a growth defect of at least 50% in LB and MOPS minimal media, respectively. While some CRISPRi constructs resulted in a growth defect in one media condition specifically (Table S2B), there were 56 constructs for which we did not observe a growth defect despite targeting the expression of an essential gene. These genes largely overlap with previously reported sets of essential genes that do not elicit a growth defect when perturbed by CRISPRi,5 examined in detail in Table S2C. We speculate that the products of these genes may have long half-lives, that the bacterium may tolerate reduced levels of viable protein, or that the genes have regulatory feedback mechanisms that result in increased expression of gene products when silenced by CRISPRi.34,39 Additionally, variations in bacterial physiology, where our collection was grown in colony arrays rather than in broth, could also account for some of the differences observed.49 Nonetheless, there is merit to including these strains in our collection to identify genetic or environmental contexts where a growth defect might be elicited.

For ease of moving the collection into different genetic backgrounds, we transformed each CRISPRi knockdown plasmid into the conjugative donor strain E. coli MFDpir,50 creating an ordered mobile CRISPRi collection. Here, we present two different applications of the mobile CRISPRi collection (Figure 2). First, the complete CRISPRi collection can be conjugated into a specific genetic background of interest, for example a deletion mutant of the Keio collection. By comparing the growth inhibitory effects of each CRISPRi construct in the mutant background to that of the wild-type background, we can uncover CRISPRi knockdowns of essential processes that exhibit enhanced or suppressed growth inhibition in the mutant background. Second, we can conjugate an individual CRISPRi knockdown strain into existing E. coli genomic collections, for instance into the Keio collection. This allows testing genetic interactions between an essential gene and all the ∼4,000 genes in the Keio collection simultaneously, supplementing existing “synthetic genetic array” screening datasets.14,17 Further, due to the compatibility of pFD152 with commonly used E. coli plasmids, individual CRISPRi constructs could also be conjugated into plasmid-borne arrayed genomic collections including transcriptional reporter collections51 and protein overexpression collections.52

Figure 2.

Schematic representing two complementary uses of the mobile arrayed CRISPRi collection to conduct gene-gene interaction studies with essential genes

(A) The entire mobile CRISPRi array could be rapidly conjugated into a strain of interest, or (B) an individual CRISPRi plasmid could be introduced into an existing genomic collection such as the Keio collection.

Although advantageous to have both dcas9 and the sgRNA on the same plasmid vector, in particular for the high-throughput genomics applications outlined in this study, there remains a risk of spontaneous suppressing mutations arising during library handling. Thus, we sought to estimate the impact of spontaneous suppression in our conjugative assay setup. We arrayed 96 technical replicates each of three CRISPRi strains targeting distinct essential genes (accA, lspA, and lolA) and the empty vector, all in the conjugative donor strain E. coli MFDpir. We then transferred these plasmids into wild-type E. coli BW25113 by high-throughput conjugation, such that each plasmid was conjugated in 96 parallel conjugations (Figure S2A). The exconjugants were then transferred to LB agar containing either 500 ng/mL of aTc or no aTc (Figure S2B). As expected, all 384 colonies in the array grew comparably in the absence of aTc while displaying potent growth inhibition in the presence of aTc. Of the 96 conjugations for each essential targeting CRISPRi plasmid, we observed between one and three small colonies growing with CRISPRi induction, likely spontaneous suppressors (<5% of conjugations). To further examine the effects of passaging CRISPRi plasmids in the absence of inducer, we grew E. coli harboring the previous four CRISPRi plasmids for five passages in LB broth and plated for spontaneous resistance mutants after each passage (Figure S2C). For each of the three CRISPRi constructs tested (pFD152-accA, pFD152-lspA, and pFD152-lolA), we did not observe a meaningful increase in the rates of spontaneous resistance following five serial passages, more passages than required in our conjugative assay setup. This observation along with the smaller appearance of the suppressor colonies compared to colonies harboring the empty vector control in the arrayed assay (Figure S2B) suggests that spontaneous suppression is unlikely to impact our study.

Conjugation of the CRISPRi collection into E. coli Δlpp identifies essential processes with altered growth inhibition from gene silencing

As a proof of principle, we elected to probe cell envelope synthesis in E. coli. First, we conjugated the mobile CRISPRi collection into E. coli Δlpp. Lpp is the most abundant lipoprotein in E. coli and acts to covalently tether peptidoglycan to the outer membrane.53,54,55,56 Perturbing essential genes involved in lipoprotein transport, namely the Lol system,57 results in the mis-localization of lipoproteins, thereby causing cell death.57,58,59 In the absence of Lpp, the growth defect associated with disrupting lipoprotein transport is reduced46. As such, we expected to observe suppressed killing by CRISPRi knockdowns targeting lipoprotein synthesis and trafficking upon mating the CRISPRi plasmids into an lpp deletion strain. Following previously published high-throughput conjugation workflows,21 we introduced the CRISPRi collection into E. coli Δlpp (Figure S2D). The wild-type (lpp+) and Δlpp CRISPRi collections were then screened at varying aTc concentrations on minimal media, and the growth observed for each strain in the Δlpp background was normalized to that of the wild-type (lpp+) collection at each concentration of inducer (Figure S3). In the absence of inducer, both the wild-type (lpp+) and Δlpp collection grew comparably; however, with induction, we observed CRISPRi constructs that exhibited either enhanced or suppressed growth inhibition in the Δlpp background (Figure 3A; Table S3). Using an arbitrary threshold of 5-fold change in growth between the Δlpp and wild-type (lpp+) collections, growth inhibition by 17 CRISPRi constructs was enhanced and for 42 CRISPRi constructs was suppressed in at least one concentration of inducer. Interestingly, more than half (24/42) of the suppressors were identified at the lowest concentration of aTc (5 ng/mL), but growth inhibition with all of these low induction suppressors was restored at higher concentrations of inducer (aTc >10 ng/mL). Looking at 100 ng/mL aTc specifically, it’s unsurprising that the four strongest suppressors identified were CRISPRi constructs targeting essential genes involved in lipoprotein synthesis and trafficking: lolA, lolB, lolC, and lnt (Figure 3B). The 17 CRISPRi plasmids that exhibited enhanced growth inhibition in an Lpp-deficient background were mostly identified at higher concentrations of aTc (>10 ng/mL). These enhancers are involved in the biosynthesis of essential phospholipids (gpsA, psd, plsBC, and pssA), the outer membrane (bamA, lpxC, lptA, and kdsC), and in cell division (ftsAHWY, dicA, and zipA). Fortunately, some of these interactions were also testable with available chemical inhibitors of these essential processes (Figure 3C). Using a commercially available inhibitor of the Lol system60 (LolCDE-in-1) and of BamA61 (MRL-494), we showed that a Δlpp strain was less susceptible to the inhibitor of the Lol system and more susceptible to the BamA inhibitor as predicted in our screen. As a control, we also assessed the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs)of three other antibiotics with distinct molecular targets in the cell envelope: ampicillin, colistin, and fosfomycin. We found that the Δlpp strain was equally sensitive to these other antibiotics, confirming that our CRISPRi screen provided strong hypotheses regarding the resistance and sensitivity of the Δlpp mutant to perturbations of different essential processes.

Figure 3.

CRISPRi genetic interaction screens identify a known genetic interaction between Lpp and lipoprotein transport

(A) The mobile arrayed CRISPRi collection was introduced into E. coli Δlpp, and the collection was screened at 6 different concentrations of aTc in minimal media. Density plots show the distribution of growth for both the wild-type (WT) and Δlpp collections at different levels of CRISPRi induction. Average growth of the WT and Δlpp collections is represented by the dotted lines in each density plot.

(B) The fold change in growth of the Δlpp CRISPRi collection relative to the WT (lpp+) CRISPRi collection shown at 100 ng/mL aTc. CRISPRi constructs with suppressed growth inhibition are shown in blue, and CRISPRi constructs with enhanced growth inhibition are shown in red. Empty vector controls are shown in orange. Hits were determined as data points that deviate by at least three standard deviations from the mean.

(C) Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of different compounds against WT and Δlpp E. coli in minimal growth media.

(D) Bar plots showing the growth of bacteria harboring different CRISPRi plasmids in WT or Δlpp backgrounds at different aTc concentrations grown on MOPS minimal medium.

(E) Dilution plating E. coli containing knockdown plasmids for different genes involved in lipoprotein transport and maturation spotted on MOPS minimal media. 10-fold serial dilutions of overnight cultures from the WT or Δlpp CRISPRi collection were spotted on minimal media containing 0 or 50 ng/mL of aTc to induce CRISPRi. Strong suppression of growth inhibition is seen with knockdown constructs targeting lolA, lolB, lolC, and lnt, which were the strongest suppressors of killing in the Δlpp CRISPRi screen.

See also Table S3.

By screening at different inducer concentrations, we could discriminate between different degrees of suppression and enhancement. For instance, the suppressive interaction of Δlpp on growth inhibition by pFD152:lolA was observed at concentrations greater than 50 ng/mL of aTc, whereas suppression by pFD152:lspA was only observed at the two lowest concentrations of inducer: 5 and 10 ng/mL aTc (Figure 3D). Both lspA and lolA are involved in lipoprotein synthesis and trafficking respectively, and Lpp-deficient bacteria are known to be resistant to depletion or inhibition of these proteins.46,62,63 Likewise, enhanced growth inhibition by pFD152:zipA was observed at 10 ng/mL aTc, while that by pFD152:plsC occurred at concentrations from 50 ng/mL aTc and greater. We further confirmed the results from our Δlpp CRISPRi screen using a standard dilution plating assay (Figure 3E). These data suggested the need to screen CRISPRi collections at multiple concentrations of inducer to identify all possible gene-gene interactions. In the case of Lpp and lipoprotein synthesis/transport, genes involved in synthesis/transport remain essential in an Lpp-deficient strain.62 Although screening at the highest inducer concentration alone would have identified the interaction between Lpp and lipoprotein transport, screening at a range of inducer concentrations informed on the global effects of an Δlpp background on the relative essentiality of different processes.

Conjugation of pFD152-lolA into the Keio deletion collection identifies genetic backgrounds with increased tolerance to silencing of lolA expression

To investigate the inverse genetic interaction screen, where a single CRISPRi construct is conjugated into an existing genomic collection, we chose to conjugate the strongest suppressor from the Δlpp CRISPRi conjugation screen, the lolA CRISPRi knockdown, into all ∼4,000 strains of the Keio collection. High-throughput conjugation of a CRISPRi plasmid into the Keio collection was performed as before, with some minor modifications to the methodology (Figure 4A). Here, we were able to investigate the effects of disrupting an essential process by CRISPRi in 4,000 non-essential deletion strains simultaneously, wherein 384 distinct deletion strains are found on each screening plate. As each deletion strain in the Keio could potentially grow faster or slower than its neighbors, it was crucial to include an empty vector control for each deletion mutant. As such, we designed an assay setup that permits screening 3 different CRISPRi knockdowns and an empty vector control in 1,536 colony density arrays, such that each mutant harboring the control plasmid is proximal to the same mutant harboring different CRISPRi plasmids (Figure S4A).

Figure 4.

Genetic screen of pFD152_lolA identifies genetic interactions that enhance and suppress killing by lolA silencing

(A) Conjugation workflow for introducing pFD152_lolA into the Keio collection by using high-density arrays. Plasmid can be efficiently introduced into all ∼4,000 strains of the Keio collection in less than 2 days.

(B) The Keio collection harboring pFD152_lolA was screened at 0, 50, and 500 ng/mL of aTc. Shown is the change in growth between mutants harboring the lolA knockdown plasmid compared to those same mutants harboring the empty vector from a representative plate of the Keio collection (384 strains). Upper and lower bounds of the box plot represent the first and third quartile of the plotted data. Median of the plotted data is shown within each box.

(C) (i) A replicate plot showing the normalized growth of two biological replicates of the pFD152_lolA Keio collection at 500 ng/mL aTc. Mutants that demonstrated growth inhibition suppressed by at least 3 standard deviations from the mean of the dataset are colored in blue. (ii) Colonies of selected enhancers and suppressors from the CRISPRi Keio cross with pFD152_lolA.

See also Table S4.

In addition to conjugating and screening the lolA CRISPRi knockdown with the Keio collection, we also conjugated and screened CRISPRi knockdowns of pssA and mreD, which code for phosphatidylserine synthase64 and an integral inner-membrane component of the elongasome,65 respectively, as controls to identify genetic interactions specific to lolA. This is crucial because we have previously observed a “frequent hitter” phenomenon when introducing a second non-essential deletion to the Keio collection with synthetic genetic arrays.21 Specifically, mutant strains with deficiencies in conjugation or recombination were frequently found to be enhancers or suppressors of growth. With CRISPRi Keio experiments, frequent hitters are likely to be deletion mutants that have deficiencies in conjugation or that impact an aspect of the mechanism by which CRISPRi silences gene expression. This includes deletion mutants with altered permeability or accumulation of the inducer (aTc) or, more interestingly, mutants that affect the mechanism of gene silencing by CRISPR. This could provide valuable insight into the underlying biology of CRISPRi-mediated gene silencing in bacteria and possible routes for a bacterium to acquire resistance to CRISPRi-mediated growth inhibition.

The CRISPRi Keio screen was conducted at two concentrations of inducer, 50 and 500 ng/mL aTc (Tables S4A and S4B). We hypothesized that enhancers of growth inhibition by CRISPRi would be easier to identify at lower concentration of inducers with marginal levels of inhibition, while suppressors would be apparent at higher concentrations of inducer and more severe levels of inhibition. Indeed, with increasing concentrations of inducer, we observed that mutants harboring the empty vectors were unperturbed, whereas mutants harboring essential gene knockdowns exhibited a dose-dependent growth defect across the screening plate (Figures 4B and S4A). To normalize the growth of each colony, we employed a previously established method that accounts for both the positional effects of a colony and plate-to-plate variability observed in high-density screening approaches66 (Figure S4B), described in detail within the STAR Methods section. After normalization, growth of each deletion mutant with a knockdown plasmid was then compared to the growth of that respective deletion mutant harboring the empty vector.

Using a cutoff of 3-standard deviations from the mean of the dataset, we identified 68 deletion mutants that suppressed growth inhibition from lolA knockdown at 500 ng/mL aTc. As expected, we found that the Δlpp mutant was one of the strongest suppressors (Figure 2C). To a lesser degree, we also identified Δfis as a suppressor of growth inhibition by lolA knockdown. Fis-deficient E. coli has been shown to be resistant to growth defects associated with an accumulation of a mutant Lpp that is unable to proceed through the lipoprotein processing and transport,67 similar to the stress imposed by knocking down lolA expression by CRISPRi. Interestingly, we also identified gene deletions that suppressed growth inhibition to a similar degree as Δlpp: Δuup, ΔcheY, and ΔholC. CheY has been shown to act as a flagellar response regulator,68 while both Uup and HolC have been implicated in aiding stalled replication complexes by associating with the Holliday junctions of stalled replication forks69 or by resolving toxic conflicts between the replication and transcription complexes,70 respectively. Interestingly, of the three mutants, Δuup also suppressed growth inhibition by mreD knockdown, and ΔholC was likewise a suppressor of growth inhibition by pssA knockdown (Figures S4C–S4E). Neither of these mutants, however, were suppressors across all three Keio crosses. Further investigation is required to test whether these deletion strains are promiscuous suppressors of CRISPRi. In contrast to the many suppressors identified, we found just nine deletion strains showing enhanced growth inhibition from lolA knockdown at 50 ng/mL aTc. Of these nine enhancers, two deletion backgrounds showed increased growth inhibition for all three CRISPRi constructs screened, namely ΔgalU and ΔyiiS. It is likely that both deletion strains enhance growth inhibition by potentiating an innate aspect of the CRISPRi system used in our study. A defect in galU has been associated with disrupted cell envelope biosynthesis including that of lipopolysaccharide,71,72 while E. coli deficient in the yiiS has been found to have defects in envelope biogenesis.73,74 As such, it is likely these mutants have enhanced growth inhibition by CRISPRi due to an increased permeability or accumulation of the inducer compound, aTc.

Discussion

Herein, we present a tool and methodology to study genetic interactions of the E. coli essential genome that is compatible with existing genomic collections. We demonstrated a methodology for the high-throughput conjugation and screening of our collection to uncover genetic interactions between essential and non-essential genes in E. coli, using a deletion of lpp and silencing of lolA expression as a proof of principle.

Having both dcas9 and the sgRNA expressed from the same vector, as is the case with pFD152,44 offers advantageous flexibility for high-throughput genomics experiments. Using highly efficient RP4-mediated conjugation facilitated by the donor strain E. coli MFDpir,50 CRISPRi plasmids can be rapidly and efficiently introduced into any ordered or pooled genomic collection in a single step. Thereby, the collection of CRISPRi plasmids described here could be introduced into ordered reporter collections, protein overexpression collections, or pooled collections such as transposon libraries offering the potential to investigate intricate questions surrounding the effects of perturbing aspects of essential biology. A possible disadvantage to expressing both dcas9 and the sgRNA from the same vector is selecting for suppressing mutations in the sgRNA during library handling in the absence of CRISPRi induction. This consideration led Silvis and colleagues39 to employ tri-parental mating in the construction of their CRISPRi collection to separate dcas9 from the partner sgRNA until the ultimate introduction of both components into the assay strain. This was particularly important as the IPTG-inducible sgRNA in their collection showed evidence of leaky expression: i.e., growth defects were observed for strains grown without inducer. With pFD152, dcas9 expression is stringently repressed by TetR, and we do not observe any growth defects for strains grown in the absence of aTc, whereas just 5 ng/mL of aTc is sufficient to elicit a growth defect for many of the strains in our collection. The strong control of CRISPRi activation is particularly important for gene-gene interaction studies as this allows the isolation of all mutants, which can then be screened for fitness defects upon adding inducer. Leaky CRISPRi activation would otherwise prevent the isolation of mutants that enhance killing, as is seen in the general failure to isolate synthetic lethal gene pairs when conducting synthetic genetic arrays.14,17,21,22 Once grown with aTc, suppressing mutations in CRISPRi strains will arise but will present as smaller colonies and are thereby discernable from bona fide genetic suppressors.

The E. coli CRISPRi collection described here can be used to investigate the dispensability of essential processes in different genetic and environmental contexts and to enhance our understanding of essential gene biology, as well as the downstream effects of perturbing different biological processes. Notably, the approach is translatable to other bacterial pathogens with ordered genomic collections. pFD152 and sister plasmids described by Depardieu and Bikard44 are built on a broad host-range plasmid compatible with Salmonella Typhimurium, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus among other bacteria. Analogous collections of CRISPRi plasmids could be constructed on this backbone and used as tools to investigate genetic interactions in these other important human pathogens.

Limitations of the study

Our method takes advantage of mobile CRISPRi plasmids that can be rapidly introduced into ordered bacterial gene deletion collections to examine the effects of silencing essential gene expression in different genetic contexts. However, there are considerations and limitations for using CRISPRi to study genetic interactions. As previously discussed, not all essential genes demonstrate perturbed growth when targeted by CRISPRi and require alternate genetic or chemical approaches of perturbation. Further, silencing gene expression by CRISPRi can result in polar effects on downstream genes found in the same transcriptional unit, which could confound interpretation of the enhancing and suppressing interactions discovered. The phenotypic contribution of other genes found within the operon of a gene of interest would have to be determined in follow-up experiments. Finally, CRISPRi approaches have relatively high rates of spontaneous suppression mostly arising from mutations in the gRNA or in the promoter of dCas9. Accordingly, the concentration of inoculum used and the growth conditions (media used, endpoint chosen, etc.) for CRISPRi assays needs to be optimized to ensure fitness defects for strains targeting essential processes are observed. With the methodology outlined in this study, we demonstrate that these suppressors appear smaller and can be easily differentiated from bona fide interactions.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E. coli MFDpir | Ferrières et al.50 | N/A |

| E. coli Keio gene deletion collection | Baba et al.4 | N/A |

| E. coli BW25113 | Baba et al.4 | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Anhydrotetracycline | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#37919 |

| Spectinomycin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#S4014 |

| Kanamycin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#60615 |

| LOLCDE-in-1 | MedChem Express | Cat#HY-130839 |

| MRL-494 | GLPBio | Cat#GC60254 |

| Ampicillin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A0166 |

| Colistin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C4461 |

| Fosfomycin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#34089 |

| Diaminopimelic acid (DAP) | Fisher Scientific | Cat#AAB2239103 |

| MOPS-minimal media | TekNova | Cat#M2101 |

| LB Broth, Miller | Fisher Scientific | Cat#DF0446 |

| Agar | Fisher Scientific | Cat#BP1423 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Plate images and data from Δlpp CRISPRi Cross and pFD152-lolA Keio Cross | This work | https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10214517 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Oligonucleotides used in this work | This paper | See Table S1 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pFD152 | Depardieu and Bikard.44 | Addgene Cat#125546 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad PRISM 9 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| CRISPRbact sgRNA design tool | Cui et al.34 | https://gitlab.pasteur.fr/dbikard/crisprbact |

| ImageJ | ImageJ | https://ImageJ.net/ij/ij/ |

| ImageJ colony biomass quantification script | French et al.12 | https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10214517 |

| Analysis R code for Δlpp CRISPRi cross and CRISPRi Keio Crosses | This work | https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10214517 |

| Other | ||

| Epson Perfection V750 high-resolution scanner | Epson | NA |

| Singer ROTOR+ | Singer Instruments | https://www.singerinstruments.com/solution/rotor/ |

| Singer RePads (384 Long and 1536 short) | Singer Instruments | Cat#REP-003; Cat#REP-005 |

| Singer PlusPlates | Singer Instruments | Cat#PLU-003 |

| Biotek Synergy Neo2 Plate Reader | BioTek | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further inquiries or requests can be directed to Eric Brown (ebrown@mcmaster.ca).

Materials availability

This study reports on the creation of 356 CRISPRi plasmids targeting essential genes in E. coli. Primers used to incorporate specific gRNA into pFD152 to create these plasmids can be found Table S1. A subset of plasmids will be made available for distribution through Addgene following publication. All reagents will be available upon request to the lead contact.

Data and code availability

-

(1)

data reported in this study is available in both the Supplemental Tables included in this publication and has been deposited onto Zenodo. An archival DOI is reported in the key resources table. Deposited data includes source images of assay plates and data from various stages of normalization. Questions regarding data can be directed to the lead contact.

-

(2)

Original code used to process colony arrays images with ImageJ and original R code which was used to normalize growth data has been deposited onto Zenodo. An archival DOI is reported in the key resources table.

-

(3)

Any additional data or information required to reproduce the results reported in this study are available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Growth conditions for E. coli

E. coli was routinely cultured in LB medium at 37°C, supplemented with antibiotics (kanamycin, 50 μg/mL and spectinomycin, 150 μg/mL) or 10 mM Diaminopimelic acid when required. For experiments on solid medium, media was prepared with 15 g/L agar. MOPS minimal medium was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions: components were filter sterilized after preparing liquid growth medium or added to sterile water and agar (1.5% w/v) for solid growth medium. Anhydrotetracycline (aTc) was added to solid agar medium to induce CRISPRi when necessary.

Method details

Plasmids and construction of CRISPRi collection

sgRNAs targeting different essential genes in E. coli were cloned into the conjugative CRISPRi plasmid pFD152 using a previously described single step Golden Gate assembly protocol.44 pFD152 was a gift from David Bikard (Addgene plasmid # 125546). sgRNAs used in this study were designed using the publicly available CRISPRbact tool (https://gitlab.pasteur.fr/dbikard/crisprbact), wherein, an sgRNA with the highest predicted on-target activity score and the least off-target homology was selected for each gene. Oligonucleotides for cloning sgRNAs were ordered from Sigma Aldrich, and specific sequences of oligonucleotides and sequences of sgRNAs can be found in Table S1. All plasmids constructed were verified by Sanger sequencing before being used for downstream experiments.

The mobile arrayed CRISPRi collection was constructed by transforming sequence verified plasmids into E. coli MFDpir,50 the conjugative donor strain for high-throughput conjugation experiments which is auxotrophic for diaminopimelic acid (DAP). All fitness screens with the CRISPRi collection were performed in E. coli BW25113 [F− Δ(araD-araB)567 lacZ4787Δ::rrnB-3 LAM− rph-1 Δ(rhaD-rhaB)568 hsdR514], and, all genes deletions used in the study were obtained from the Keio collection4 (kanamycin resistant single-gene deletions in E. coli BW25113).

High-throughput conjugation and CRISPRi array screening

High-throughput conjugation of the mobile arrayed CRISPRi collection was conducted as previously described with some modifications.20,21,22 For high-throughput conjugation and screening of the CRISPRi collection into a genetic background of interest such as E. coli Δlpp, the query strain (kanamycin resistant E. coli Δlpp) was arrayed on LB agar with kanamycin at 1,536-colony density using the Singer Rotor HDA. The mobile arrayed CRISPRi collection was likewise pinned at 1,536 colony density, with each strain of the collection in technical quadruplicate, on LB with spectinomycin and DAP. The query strain and CRISPRi collection were then co-pinned onto LB agar with DAP but without antibiotic selection, and incubated at 37°C for 2 h for allow for conjugation to occur. After conjugation, colonies were transferred to LB agar with kanamycin and spectinomycin to select for the exconjugants which have both the gene deletion of interest and the CRISPRi plasmid, then were incubated overnight at 37°C. For screening the CRISPRi collection, the exconjugants were used to inoculate LB media with kanamycin and spectinomycin in a 384-microwell plate (Corning) and grown overnight, then cultures were diluted either 100-fold or 10-fold into sterile PBS for assays in rich or minimal medium assays, respectively. These dilutions resulted in a cellular density of ∼2×106 (10-fold dilution) and ∼2×105 (100-fold dilution) CFUs/ml in PBS. Cells were then pinned onto solid media containing five concentrations of aTc (0, 5, 10, 50, 500 ng/mL) using the Singer ROTOR+ HDA (∼1 μL), then were grown for 16 h at 37°C and visualized using transmissive scanners.

For conjugation of a specific CRISPRi plasmid into a genomic collection, the workflow is followed as above with minor modifications. E. coli MFDpir harboring a CRISPRi plasmid of interest was arrayed at 1,536 density on LB with spectinomycin and DAP, whilst the Keio collection was arrayed at 1,536 density on LB with kanamycin. As before, the donor strain harboring the CRISPRi plasmid and the Keio collection were co-pinned onto LB agar with DAP but without antibiotic selection, and incubated at 37°C for 2 h to allow for conjugation to occur. Then, colonies were transferred to LB agar with kanamycin and spectinomycin to select for the exconjugants which have both the gene deletion of interest and the CRISPRi plasmid, then were incubated overnight at 37°C. For screening the CRISPRi-Keio collections, the exconjugants containing the empty vector and CRISPRi plasmids were first used to inoculate LB with spectinomycin and kanamycin in 384-microwell plates and grown overnight–the Keio collection is 12 individual 384 well plates in its entirety. Then, cultures are spotted onto a 1536-colony density solid agar plates containing different concentrations of aTc, such that each Keio mutant is found in four proximal colonies– each with a different CRISPRi plasmid or vector control. CRISPRi Keio screens were conducted in technical duplicate.

Plate imaging quantification and analysis

After being grown to endpoint, solid media screening plates were imaged using an Epson Perfection V750 to generate a high-resolution image, from which the integrated density of each colony was determined using previously published ImageJ pipelines.12 Analysis and data normalization was performed differently based on screen being performed. For analysis of CRISPRi collection growth in wildtype (lpp+) and Δlpp backgrounds, the average raw colony density of the 17 strains harboring the empty vector was calculated, then, this value was used to normalize the growth of strains harboring different CRISPRi plasmids. The average of the two technical replicates was then calculated and is reported in Table S2. As the whole collection was screened on a single solid agar plate, plate to plate variability was not a concern, and spatial growth effects likewise did not appear to impact growth meaningfully.

For analysis of the CRISPRi Keio assay, a two-pass normalization method was used to account for both spatial and plate to plate variation observed. This normalization is similar to a previously published approach to normalize high-throughput screening datasets.66 In summary, the entire Keio screen used 24 assay plates at every aTc concentration – the 12 Keio collection assay plates screened in biological duplicate – wherein mutants with the same CRISPRi plasmid occupy the same position in each plate. First, spatial effects across the 24 assay plates were normalized by dividing each colony with the inter-quartile mean (IQM) of every colony occupying the same position on other plates (with the same CRISPRi plasmid). Then, plate to plate variability was normalized by dividing the growth of each colony, by the IQM of the growth of every other colony harboring the same CRISPRi plasmid within each screening plate. Following spatial and intra-plate normalization, the growth of each deletion mutant with a gene knockdown plasmid was then normalized to the growth that respective deletion mutant with the empty vector.

MIC determination and dilution plating

For MIC assays, overnight cultures of bacteria were grown in LB broth supplemented with appropriate antibiotic selection. Cultures were diluted (1:100) into fresh LB medium and grown to mid-log phase of growth (OD600 ∼0.5). Subcultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.1, then diluted (1:5000) into assay medium, MOPS minimal medium or LB. MIC assay plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h, then OD600 was measured using a Tecan Infinite series micro-plate reader.

For dilution plating assays, overnight cultures of bacteria were grown in LB broth supplemented with appropriate antibiotic selection. Following growth, each culture was pelleted and resuspended in sterile PBS to a final OD600 of 1.0. Then 10-fold serial dilutions of the culture were prepared in sterile PBS, and a 10 μL spot of culture was dispensed onto solid growth plates with and without aTc, and grown for 18 h at 37°C. Images of dilution plating assay plates were obtained using an Epson Perfection V750 high-resolution scanner.

Passaging and determination of rate of suppression

E. coli WT harboring different CRISPRi plasmids was grown overnight in LB broth supplemented with spectinomycin without CRISPRi induction. After overnight growth, cultures were used to both inoculate the next day’s passage (1 in 10,000 dilution in LB broth with spectinomycin) and were pelleted and resuspended in sterile PBS to a final OD600 of 1.0. 10-fold dilutions of each culture were prepared, and a 200 μL spot of each dilution was deposited on LB agar with (500 ng/mL) and without aTc. Spots were allowed to dry in a laminar flow hood for 20 min, then plates were incubated overnight. Spots with discernable colonies were enumerated for CFUs. The frequency of spontaneous suppression was calculated as the CFUs when plated with aTc, divided by the CFUs when plated without aTc. Passaging and plating was repeated for 5 days.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Sizes of bacterial colonies in high-density arrays were quantified using ImageJ.75 All original code that was used to quantify colony size can be found on Zenodo (see data and code availability section). Data was plotted using R 4.2.176. R-squared value to test for replication of datasets was calculated using the rsq() function in R.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Maya Farha for helpful comments and discussion. This research was supported by a Discovery Grant for the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2019-07090) and by infrastructure funding from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the Ontario Research Fund (ORF-RE09-047). E.D.B. was supported by a Tier I Canada Research Chair award, K.R. was supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship, and M.M.T. was supported by Canada Graduate Scholarship.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, K.R. and E.D.B.; methodology, K.R. and E.D.B.; investigation, K.R., M.M.T., S.J.M., and D.M.H.; formal analysis, K.R.; writing – original draft, K.R, and E.D.B.; writing – review & editing, M.M.T., and E.D.B.; funding acquisition, E.D.B; resources, E.D.B; supervision, E.D.B.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Published: January 22, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2023.100693.

Supplemental information

(2A) Average normalized growth of every CRISPRi strain at different inducer concentrations grown in LB and MOPS minimal medium. (2B) Strains with differential sensitivity in LB media compared to MOPS minimal media. (2C) CRISPRi constructs targeting essential processes that did not inhibit growth of E. coli.

(4A) Normalized growth of all CRISPRi strains in Keio cross assay. (4B) Suppressors and enhancers identified from the CRISPRi Keio cross.

References

- 1.Hogan A.M., Cardona S.T. Gradients in gene essentiality reshape antibacterial research. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2022;46:fuac005. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuac005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Elia M.A., Pereira M.P., Brown E.D. Are essential genes really essential? Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:433–438. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodall E.C.A., Robinson A., Johnston I.G., Jabbari S., Turner K.A., Cunningham A.F., Lund P.A., Cole J.A., Henderson I.R. The essential genome of Escherichia coli K-12. mBio. 2018;9 doi: 10.1128/mBio.02096-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baba T., Ara T., Hasegawa M., Takai Y., Okumura Y., Baba M., Datsenko K.A., Tomita M., Wanner B.L., Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2:2006.0008–0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rousset F., Cui L., Siouve E., Becavin C., Depardieu F., Bikard D. Genome-wide CRISPR-dCas9 screens in E. coli identify essential genes and phage host factors. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerdes S.Y., Scholle M.D., Campbell J.W., Balázsi G., Ravasz E., Daugherty M.D., Somera A.L., Kyrpides N.C., Anderson I., Gelfand M.S., et al. Experimental determination and system level analysis of essential genes in Escherichia coli MG1655. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:5673–5684. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.19.5673-5684.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juhas M., Eberl L., Church G.M. Essential genes as antimicrobial targets and cornerstones of synthetic biology. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farha M.A., Leung A., Sewell E.W., D’Elia M.A., Allison S.E., Ejim L., Pereira P.M., Pinho M.G., Wright G.D., Brown E.D. Inhibition of WTA synthesis blocks the cooperative action of PBPs and sensitizes MRSA to β-lactams. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:226–233. doi: 10.1021/cb300413m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gehrke S.S., Kumar G., Yokubynas N.A., Côté J.P., Wang W., French S., MacNair C.R., Wright G.D., Brown E.D. Exploiting the Sensitivity of Nutrient Transporter Deletion Strains in Discovery of Natural Product Antimetabolites. ACS Infect. Dis. 2017;3:955–965. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klobucar K., Brown E.D. Use of genetic and chemical synthetic lethality as probes of complexity in bacterial cell systems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018;42:fux054. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols R.J., Sen S., Choo Y.J., Beltrao P., Zietek M., Chaba R., Lee S., Kazmierczak K.M., Lee K.J., Wong A., et al. Phenotypic landscape of a bacterial cell. Cell. 2011;144:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.French S., Mangat C., Bharat A., Côté J.P., Mori H., Brown E.D. A robust platform for chemical genomics in bacterial systems. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2016;27:1015–1025. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-08-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong M., French S., El Zahed S.S., Ong W.K., Karp P.D., Brown E.D. Gene Dispensability in Escherichia coli Grown in Thirty Different Carbon Environments. mBio. 2020;11 doi: 10.1128/mBio.02259-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Typas A., Nichols R.J., Siegele D.A., Shales M., Collins S.R., Lim B., Braberg H., Yamamoto N., Takeuchi R., Wanner B.L., et al. High-throughput, quantitative analyses of genetic interactions in E. coli. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:781–787. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babu M., Díaz-Mejía J.J., Vlasblom J., Gagarinova A., Phanse S., Graham C., Yousif F., Ding H., Xiong X., Nazarians-Armavil A., et al. Genetic interaction maps in Escherichia coli reveal functional crosstalk among cell envelope biogenesis pathways. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babu M., Arnold R., Bundalovic-Torma C., Gagarinova A., Wong K.S., Kumar A., Stewart G., Samanfar B., Aoki H., Wagih O., et al. Quantitative Genome-Wide Genetic Interaction Screens Reveal Global Epistatic Relationships of Protein Complexes in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butland G., Babu M., Díaz-Mejía J.J., Bohdana F., Phanse S., Gold B., Yang W., Li J., Gagarinova A.G., Pogoutse O., et al. eSGA: E. coli synthetic genetic array analysis. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:789–795. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babu M., Bundalovic-Torma C., Calmettes C., Phanse S., Zhang Q., Jiang Y., Minic Z., Kim S., Mehla J., Gagarinova A., et al. Global landscape of cell envelope protein complexes in Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:103–112. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar A., Beloglazova N., Bundalovic-Torma C., Phanse S., Deineko V., Gagarinova A., Musso G., Vlasblom J., Lemak S., Hooshyar M., et al. Conditional Epistatic Interaction Maps Reveal Global Functional Rewiring of Genome Integrity Pathways in Escherichia coli. Cell Rep. 2016;14:648–661. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rachwalski K., Ellis M.J., Tong M., Brown E.D. Synthetic Genetic Interactions Reveal a Dense and Cryptic Regulatory Network of Small Noncoding RNAs in Escherichia coli. mBio. 2022;13:e0122522. doi: 10.1128/mbio.01225-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klobucar K., French S., Côté J.P., Howes J.R., Brown E.D. Genetic and chemical-genetic interactions map biogenesis and permeability determinants of the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. mBio. 2020;11 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00161-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Côté J.P., French S., Gehrke S.S., MacNair C.R., Mangat C.S., Bharat A., Brown E.D. The genome-wide interaction network of nutrient stress genes in Escherichia coli. mBio. 2016;7 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01714-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price M.N., Wetmore K.M., Waters R.J., Callaghan M., Ray J., Liu H., Kuehl J.V., Melnyk R.A., Lamson J.S., Suh Y., et al. Mutant phenotypes for thousands of bacterial genes of unknown function. Nature. 2018;557:503–509. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.French S., Ellis M.J., Coutts B.E., Brown E.D. Chemical genomics reveals mechanistic hypotheses for uncharacterized bioactive molecules in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017;39:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dohmen R.J., Wu P., Varshavsky A. Heat-Inducible Degron: a Method for Constructing Temperature-Sensitive Mutants. Science. 1994;263:1273–1276. doi: 10.1126/science.8122109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y., Cole K., Altman S. The effect of a single, temperature-sensitive mutation on global gene expression in Escherichia coli. RNA. 2003;9:518–532. doi: 10.1261/rna.2198203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakano H., Yamada S., Ikemura T., Shimura Y., Ozeki H. Temperature sensitive mutants of Escherichia coli for tRNA synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1974;1:355–371. doi: 10.1093/nar/1.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown E.D., Vivas E.I., Walsh C.T., Kolter R. MurA (MurZ), the enzyme that catalyzes the first committed step in peptidoglycan biosynthesis, is essential in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4194–4197. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4194-4197.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larson M.H., Gilbert L.A., Wang X., Lim W.A., Weissman J.S., Qi L.S. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2180–2196. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Todor H., Silvis M.R., Osadnik H., Gross C.A. Bacterial CRISPR screens for gene function. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021;59:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters J.M., Koo B.-M., Patino R., Heussler G.E., Hearne C.C., Qu J., Inclan Y.F., Hawkins J.S., Lu C.H.S., Silvis M.R., et al. Enabling genetic analysis of diverse bacteria with Mobile-CRISPRi. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:244–250. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0327-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keseler I.M., Gama-Castro S., Mackie A., Billington R., Bonavides-Martínez C., Caspi R., Kothari A., Krummenacker M., Midford P.E., Muñiz-Rascado L., et al. The EcoCyc Database in 2021. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:711077. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.711077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S., Jendresen C.B., Landberg J., Pedersen L.E., Sonnenschein N., Jensen S.I., Nielsen A.T. Genome-Wide CRISPRi-Based Identification of Targets for Decoupling Growth from Production. ACS Synth. Biol. 2020;9:1030–1040. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cui L., Vigouroux A., Rousset F., Varet H., Khanna V., Bikard D. A CRISPRi screen in E. coli reveals sequence-specific toxicity of dCas9. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1912. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04209-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calvo-Villamañán A., Ng J.W., Planel R., Ménager H., Chen A., Cui L., Bikard D. On-target activity predictions enable improved CRISPR-dCas9 screens in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Bakker V., Liu X., Bravo A.M., Veening J.W. CRISPRi-seq for genome-wide fitness quantification in bacteria. Nat. Protoc. 2022;17:252–281. doi: 10.1038/s41596-021-00639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranava D., Yang Y., Orenday-Tapia L., Rousset F., Turlan C., Morales V., Cui L., Moulin C., Froment C., Munoz G., et al. Lipoprotein dolP supports proper folding of bamA in the bacterial outer membrane promoting fitness upon envelope stress. Elife. 2021;10:e67817. doi: 10.7554/eLife.67817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrick J.E., Lenski R.E. Genome-wide Mutational Diversity in an Evolving Population of Escherichia coli. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2009;74:119–129. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2009.74.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silvis M.R., Rajendram M., Shi H., Osadnik H., Gray A.N., Cesar S., Peters J.M., Hearne C.C., Kumar P., Todor H., et al. Morphological and transcriptional responses to CRISPRi knockdown of essential genes in Escherichia coli. mBio. 2021;12:e0256121. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02561-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters J.M., Colavin A., Shi H., Czarny T.L., Larson M.H., Wong S., Hawkins J.S., Lu C.H.S., Koo B.M., Marta E., et al. A comprehensive, CRISPR-based functional analysis of essential genes in bacteria. Cell. 2016;165:1493–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anglada-Girotto M., Handschin G., Ortmayr K., Campos A.I., Gillet L., Manfredi P., Mulholland C.V., Berney M., Jenal U., Picotti P., Zampieri M. Combining CRISPRi and metabolomics for functional annotation of compound libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022;18:482–491. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-00970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donati S., Kuntz M., Pahl V., Farke N., Beuter D., Glatter T., Gomes-Filho J.V., Randau L., Wang C.Y., Link H. Multi-omics Analysis of CRISPRi-Knockdowns Identifies Mechanisms that Buffer Decreases of Enzymes in E. coli Metabolism. Cell Syst. 2021;12:56–67.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2020.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mateus A., Hevler J., Bobonis J., Kurzawa N., Shah M., Mitosch K., Goemans C.V., Helm D., Stein F., Typas A., Savitski M.M. The functional proteome landscape of Escherichia coli. Nature. 2020;588:473–478. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-3002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Depardieu F., Bikard D. Gene silencing with CRISPRi in bacteria and optimization of dCas9 expression levels. Methods. 2020;172:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2019.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zwiebel L.J., Inukai M., Nakamura K., Inouye M. Preferential selection of deletion mutations of the outer membrane lipoprotein gene of Escherichia coli by globomycin. J. Bacteriol. 1981;145:654–656. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.654-656.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehman K.M., Smith H.C., Grabowicz M. A Biological Signature for the Inhibition of Outer Membrane Lipoprotein Biogenesis. mBio. 2022;13:e0075722. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00757-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rostain W., Grebert T., Vyhovskyi D., Pizarro P.T., Tshinsele-Van Bellingen G., Cui L., Bikard D. Cas9 off-target binding to the promoter of bacterial genes leads to silencing and toxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:3485–3496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho S., Choe D., Lee E., Kim S.C., Palsson B., Cho B.K. High-Level dCas9 Expression Induces Abnormal Cell Morphology in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018;7:1085–1094. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goh E.B., Yim G., Tsui W., McClure J.A., Surette M.G., Davies J. Transcriptional modulation of bacterial gene expression by subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:17025–17030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252607699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrières L., Hémery G., Nham T., Guérout A.M., Mazel D., Beloin C., Ghigo J.M. Silent mischief: Bacteriophage Mu insertions contaminate products of Escherichia coli random mutagenesis performed using suicidal transposon delivery plasmids mobilized by broad-host-range RP4 conjugative machinery. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:6418–6427. doi: 10.1128/JB.00621-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaslaver A., Bren A., Ronen M., Itzkovitz S., Kikoin I., Shavit S., Liebermeister W., Surette M.G., Alon U. A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kitagawa M., Ara T., Arifuzzaman M., Ioka-Nakamichi T., Inamoto E., Toyonaga H., Mori H. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (A complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 2005;12:291–299. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Braun V. Molecular organization of the rigid layer and the cell wall of Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 1973;128:S9–S16. doi: 10.1093/infdis/128.supplement_1.s9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braun V., Rehn K. Chemical characterization, spatial distribution and function of a lipoprotein (murein-lipoprotein) of the E. coli cell wall. The specific effect of trypsin on the membrane structure. Eur. J. Biochem. 1969;10:426–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1969.tb00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inouye S., Wang S., Sekizawa J., Halegoua S., Inouye M. Amino acid sequence for the peptide extension on the prolipoprotein of the Escherichia coli outer membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:1004–1008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.3.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mathelié-Guinlet M., Asmar A.T., Collet J.F., Dufrêne Y.F. Lipoprotein Lpp regulates the mechanical properties of the E. coli cell envelope. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1789–1811. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15489-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grabowicz M. Lipoproteins and Their Trafficking to the Outer Membrane. EcoSal Plus. 2019;8 doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0038-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruiz N., Gronenberg L.S., Kahne D., Silhavy T.J. Identification of two inner-membrane proteins required for the transport of lipopolysaccharide to the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5537–5542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801196105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grabowicz M., Silhavy T.J. Redefining the essential trafficking pathway for outer membrane lipoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:4769–4774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702248114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McLeod S.M., Fleming P.R., MacCormack K., McLaughlin R.E., Whiteaker J.D., Narita S.I., Mori M., Tokuda H., Miller A.A. Small-molecule inhibitors of gram-negative lipoprotein trafficking discovered by phenotypic screening. J. Bacteriol. 2015;197:1075–1082. doi: 10.1128/JB.02352-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hart E.M., Mitchell A.M., Konovalova A., Grabowicz M., Sheng J., Han X., Rodriguez-Rivera F.P., Schwaid A.G., Malinverni J.C., Balibar C.J., et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of BamA impervious to efflux and the outer membrane permeability barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:21748–21757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912345116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tajima T., Yokota N., Matsuyama S., Tokuda H. Genetic analyses of the in vivo function of LolA, a periplasmic chaperone involved in the outer membrane localization of Escherichia coli lipoproteins. FEBS Lett. 1998;439:51–54. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Diao J., Komura R., Sano T., Pantua H., Storek K.M., Inaba H., Ogawa H., Noland C.L., Peng Y., Gloor S.L., et al. Inhibition of Escherichia coli lipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase is insensitive to resistance caused by deletion of Braun’s lipoprotein. J. Bacteriol. 2021;203:e0014921. doi: 10.1128/JB.00149-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raetz C.R., Carman G.M., Dowhan W., Jiang R.T., Waszkuc W., Loffredo W., Tsai M.D. Phospholipids chiral at phosphorus. Steric course of the reactions catalyzed by phosphatidylserine synthase from Escherichia coli and yeast. Biochemistry. 1987;26:4022–4027. doi: 10.1021/bi00387a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu X., Biboy J., Consoli E., Vollmer W., den Blaauwen T. MreC and MreD balance the interaction between the elongasome proteins PBP2 and RodA. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1009276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mangat C.S., Bharat A., Gehrke S.S., Brown E.D. Rank Ordering Plate Data Facilitates Data Visualization and Normalization in High-Throughput Screening. J. Biomol. Screen. 2014;19:1314–1320. doi: 10.1177/1087057114534298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patil D., Xun D., Schueritz M., Bansal S., Cheema A., Crooke E., Saxena R. Membrane Stress Caused by Unprocessed Outer Membrane Lipoprotein Intermediate Pro-Lpp Affects DnaA and Fis-Dependent Growth. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:677812. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.677812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antani J.D., Gupta R., Lee A.H., Rhee K.Y., Manson M.D., Lele P.P. Mechanosensitive recruitment of stator units promotes binding of the response regulator CheY-P to the flagellar motor. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:5442–5448. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25774-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Romero Z.J., Armstrong T.J., Henrikus S.S., Chen S.H., Glass D.J., Ferrazzoli A.E., Wood E.A., Chitteni-Pattu S., Van Oijen A.M., Lovett S.T., et al. Frequent template switching in postreplication gaps: suppression of deleterious consequences by the Escherichia coli Uup and RadD proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:212–230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cooper D.L., Harada T., Tamazi S., Ferrazzoli A.E., Lovett S.T. The role of replication clamp-loader protein holC of Escherichia coli in overcoming replication/transcription conflicts. mBio. 2021;12 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00184-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Genevaux P., Bauda P., DuBow M.S., Oudega B. Identification of Tn 10 insertions in the rlaG, rfaP, and galU genes involved in lipopolysaccharide core biosynthesis that affect Escherichia coli adhesion. Arch. Microbiol. 1999;172:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s002030050732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sundararajan T.A., Rapin A.M.C., Kalckar H.M. Biochemical observations om E. coli mutants defective in uridine diphosphoglucose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1962;48:2187–2193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.12.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rezuchova B., Miticka H., Homerova D., Roberts M., Kormanec J. New members of the Escherichia coli sigmaE regulon identified by a two-plasmid system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003;225:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paradis-Bleau C., Kritikos G., Orlova K., Typas A., Bernhardt T.G. A Genome-Wide Screen for Bacterial Envelope Biogenesis Mutants Identifies a Novel Factor Involved in Cell Wall Precursor Metabolism. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:1004056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ihaka R., Gentleman R. R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph Stat. 1996;5:299–314. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(2A) Average normalized growth of every CRISPRi strain at different inducer concentrations grown in LB and MOPS minimal medium. (2B) Strains with differential sensitivity in LB media compared to MOPS minimal media. (2C) CRISPRi constructs targeting essential processes that did not inhibit growth of E. coli.

(4A) Normalized growth of all CRISPRi strains in Keio cross assay. (4B) Suppressors and enhancers identified from the CRISPRi Keio cross.

Data Availability Statement

-

(1)

data reported in this study is available in both the Supplemental Tables included in this publication and has been deposited onto Zenodo. An archival DOI is reported in the key resources table. Deposited data includes source images of assay plates and data from various stages of normalization. Questions regarding data can be directed to the lead contact.

-

(2)

Original code used to process colony arrays images with ImageJ and original R code which was used to normalize growth data has been deposited onto Zenodo. An archival DOI is reported in the key resources table.

-

(3)

Any additional data or information required to reproduce the results reported in this study are available from the lead contact upon request.