Abstract

Transition to Residency (TTR) courses help ease the critical transition from medical school to residency, yet there is little guidance for developing and running these courses. In this perspective, the authors use their expertise as well as a review of the literature to provide guidance and review possible solutions to challenges unique to these courses. TTR courses should be specialty-specific, allow for flexibility, and utilize active learning techniques. A needs assessment can help guide course content, which should focus on what is necessary to be ready for day one of residency. The use of residents in course planning and delivery can help create a sense of community and ensure that content is practical. While course assessments are largely formative, instructors should anticipate the need for remediation, especially for skills likely to be performed with limited supervision during residency. Additionally, TTR courses should incorporate learner self-assessment and goal setting; this may be valuable information to share with learners’ future residency programs. Lastly, TTR courses should undergo continuous quality improvement based on course evaluations and surveys. These recommendations are essential for effective TTR course implementation and improvement.

Keywords: Undergraduate medical education, curriculum development, transition to residency

Introduction

The transition from medical school to residency is a critical period involving tremendous growth in clinical and professional responsibilities. There is increasing awareness that trainees may be underprepared to handle this transition.1-4 Transition to Residency (TTR) courses, also known as “residency preparation courses,” “boot camps,” or “capstone courses” are recognized as an important mechanism to ease this transition.5-8

TTR courses are increasing in number across the United States.9,10 These courses typically occur near the end of the final year of medical school and involve simulation-based practice, review of high-yield material (eg medical emergencies), and assessment of essential skills (eg performing sign-out, responding to pages).5,6,11 Recently, the Coalition for Physician Accountability's Undergraduate Medical Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (COPA UGRC) recommended that specialty-specific training be provided to all incoming first-year residents to support this transition. 4

While there is an established national curriculum in place to guide the implementation of surgical-based TTR courses,11,12 other fields do not have a national curriculum and are less uniform in both the structure and content of their courses. Established TTR courses vary widely in duration, ranging from several days13,14 to 1 month, 5 or more. They can also vary in structure from specialty-specific courses5,14-16 to a more general capstone-type course. 6 Regardless, a “one-size-fits-all” approach would not be ideal for TTR courses given the diversity of specialties and the variability of prior training received in medical school.

In this article, the authors use their expertise and experiences as TTR course directors and a review of the published literature to describe recommendations that are essential in the development of an effective TTR course. While this manuscript addresses the United States medical education system, similar principles can be applied to transitions in international training.

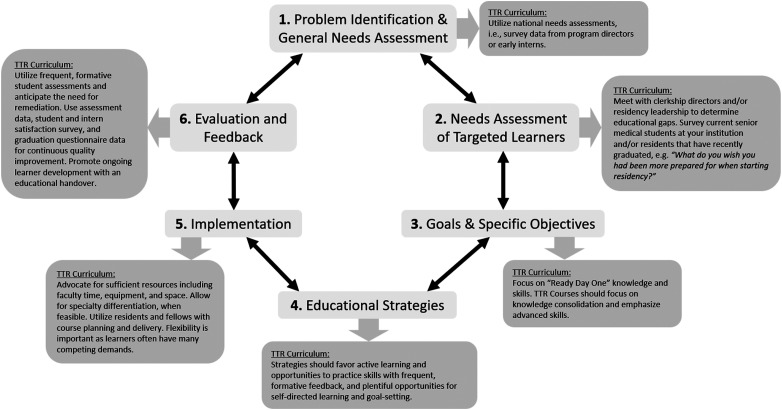

The authors use Kern's 6-step model for curriculum development 17 to support many of these recommendations (Figure 1). As Kern et al suggest, curricular development is a dynamic process, and many steps overlap or influence one another. Hence, these recommendations are intended to be helpful for both new and established TTR courses. Throughout the text, the authors also introduce common challenges unique to TTR courses and strategies to mitigate these challenges (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Kerns’ model for curriculum development applied to transition to residency (TTR) course based on Kern, D. E. (1998). Curriculum development for medical education: A 6-step approach. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Table 1.

Common challenges of transition to residency courses and suggestions for managing them.

| CHALLENGE | DESCRIPTION Of CHALLENGE | SUGGESTIONS FOR MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Struggling learners | Learners are near the end of medical school training, leaving limited time for remediation. |

|

| Not enough instructors | Most instructors helping with TTR courses are doing so on a volunteer basis. TTR courses rely heavily on active learning which may require a reduced student: instructor ratio. It can be challenging to find enough instructors and to retain them. |

|

| Competing demands for students | Students have many obligations related to the Residency Match, graduation, licensing paperwork, and personal life. This can make it challenging for students to attend all elements of the TTR course and can make decisions about what absences to allow difficult. |

|

| Insufficient resources | Course directors may have limited access to simulation resources, materials, faculty effort, or funding. |

|

| Asked to include too many other activities | Course directors may be asked to fit in requirements that are not related to the TTR course. |

|

| Stress around the residency Match | TTR Courses are often positioned around the time of the Residency Match which can be stressful for students, especially if they do not match into their desired program. |

|

ACLS = advanced cardiac life support; CV = curriculum vitae; ILP = individualized learning plan; GME = graduate medical education; TTR = transition to residency.

The study does not require ethics approval as it is a perspective.

Recommendations for Transition to Residency Course Implementation

Kern's steps 1 and 2: Problem identification; general and targeted needs assessment

Perform a needs assessment

Conducting a needs assessment is essential to developing a curriculum when considering what content to include in a TTR course. 17 Reviewing national needs assessments can speak broadly to gaps in education,18,19 while interviewing or assessing senior medical students at the medical school can identify gaps in the undergraduate curriculum. Most TTR course directors choose to conduct a local needs assessment at the development of the course and then periodically thereafter. Residents and residency program leadership should be included in this stage as their involvement serves two purposes: (1) They can help identify specialty-specific content and (2) this helps promote “buy-in” from learners because their future specialty community is contributing to the curricular content. One strategy to help identify content gaps is to ask the early residents, “What do you wish you had been more prepared for when starting residency?”

Kern's step 3: Goals and specific objectives

Focus on “ready day one” knowledge and skills

TTR course content should be targeted to ensure that learners are “ready day one” for residency. Nationally, some professional societies11,12 have developed specific recommendations for TTR course content and this may be a helpful starting point in curriculum development. Standardization of curricular content 20 may help residency programs to have a better understanding of the foundational knowledge that new residents are entering with, and may also allow for resource sharing (eg for smaller specialties). It is important to keep in mind that transition courses should consolidate knowledge and emphasize advanced skills that may not have been covered comprehensively in other parts of the curriculum. Course directors must resist the common tendency or institutional pressure to insert all other topics or required training for which there is no time in other portions of the curriculum. Additionally, it is helpful to concentrate educational efforts on an “approach to” perspective rather than from a “what is” lens. For example, if discussing altered mental status, focus on strategies for initial evaluation of the acutely altered patient, rather than simply reviewing a list of potential etiologies of altered mentation. Following the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) milestones can allow a comprehensive approach when determining the advanced skills for M4s and ways to implement them into a transition course (Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of transition to residency course skills and curricular implementation techniques, as applied to the ACGME milestones.

| ACGME MILESTONE | EXAMPLE OF SKILL | EXAMPLE OF EDUCATIONAL STRATEGIES |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal communication skills | Code status conversation | Standardized patient case or role-play |

| Leading family meetings | Standardized patient case or role-play | |

| Breaking bad news | Standardized patient case or role-play | |

| Informed consent | Standardized patient case or role-play | |

| Residents as teachers | Observed standardized teaching evaluation | |

| Physician-nurse communication | Simulated paging | |

| Patient care | ACLS/PALS training | Simulated paging |

| Common cross-cover scenarios | Case-based small group discussions or interactive didactics | |

| Procedural skills | Simulation | |

| Medical knowledge | Emerging topics (eg COVID-19) | Analysis/small group presentation of major review articles or journal clubs |

| Systems-based practice | Transitions of care: effective sign-out | Role play utilizing standardized tools |

| Addressing bias and inequity in healthcare | Case-based small group discussions | |

| Practice-based learning and improvement | Goal setting | Development of individual learning plans |

| Professionalism | Medical Professionalism and ethical conduct | Reviewing licensure processes and common ethical challenges |

| Other | Resident well-being | Resident panels, utilizing near-peer educators |

| Interprofessional education | Overlapping training modules with advanced practice, nursing, or pharmacy students | |

| Finances/loan repayment | Financial literacy training |

These skills are meant to serve as examples of what a transition to residency course may choose to include. For each course, the skills and competencies chosen to focus on will be individualized depending on each medical school's unique curricular structures and learner needs. ACGME = Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; ACLS = advanced cardiac life support; PALS = pediatric advanced life support; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Kern's step 4: Educational strategies

Incorporate learner self-reflection, self-assessment and goal setting

TTR courses represent an opportune time for learners to reflect on their medical training and the evolution of their professional identities before advancing to the next phase of learning. Practicing reflection may have multiple benefits into residency. 21 Incorporating guided self-assessment in concert with self-directed learning (SDL) is critical during this transition. SDL is a fundamental attribute of healthcare professional identity. 22 To foster the development of SDL skills, the ACGME requires residents to complete an Individualized Learning Plan (ILP). 23 While TTR courses are often short in length, they can provide opportunities to practice and improve SDL skills by requiring the use of an ILP. Offering a tool that directs learners to personal reflection allows the learner to identify areas of weakness and develop goals that are specific and measurable. Following up at set intervals guides the learners to assess their progress and direct the next steps within the course. A practical application of this could be to provide learners with a guided prompt for self-reflection on their medical education journey and professional identities prior to the start of the course based on prior evaluations and clinical experiences. Then prompt them to develop an ILP for the course based on areas of growth identified in their reflections. Providing scheduled times to check in, modify, and evaluate progress is essential, ideally with a faculty member whom the student already has a pre-existing longitudinal relationship. This increases learners’ engagement and may promote further SDL into residency.

Utilize active learning techniques with opportunities to practice skills

The appropriate TTR course teaching strategies will depend on the course and session objectives. Given that the overarching goal of TTR courses is to prepare graduating students to be effective resident physicians in clinical settings, we recommend that courses employ active learning techniques allowing for the application of medical knowledge and skills practice with feedback. Active learning techniques increase critical and creative thinking, problem-solving abilities, adaptability, communication, and interpersonal skills. 24 Flipped-classroom, audience response systems, and simulation-based training are commonly utilized in TTR courses. These pedagogies are designed to maximize student engagement, maintain a safe learning environment, and provide timely feedback allowing for students to participate in deliberate practice and mastery learning of crucial skills needed in the first few months of residency. 25

Kern's step 5: Implementation

Advocate for sufficient resources

The addition of a TTR course is superimposed upon core curricular demands in a setting where finances, faculty time, and curricular time are limited. It is critical to meet with school leadership to advocate for sufficient resources. This may include classroom space, simulation equipment, and audiovisual support. Faculty and staff support is also essential. One institution noted in 2011 that 20% protected time/salary support was allotted for course director(s) and 20% effort for a course administrator. 6 Among the authors’ TTR courses in 2022, the faculty directors receive an average of 55% full-time equivalent (FTE; range 10-130%) from their respective medical schools. Demonstrating the impact of the course by pre/post assessments of students can justify its value as can published literature on the benefit of TTR courses. 3

Allow for specialty differentiation

Creating specialty-specific components for a TTR course is worthwhile for multiple reasons. First, students have generally found learning with peers entering the same field to be valuable. 26 ,27 Specifically, one qualitative study demonstrated that graduates from TTR courses value the ability to reflect and evolve their professional identity as a resident in a specialty with a unique culture. 28 Second, allowing specialty differentiation may permit higher retention of information by decreasing the cognitive load involved in transferring learning from one specialty context to another. 29 Even in areas where a central framework applies to multiple specialties (eg, approaches to delivering a terminal diagnosis), the approach, words, and patient response may vary significantly between different specialties (eg pediatrics vs internal medicine). Certain skills important for the first year of residency differ between specialties and would be challenging to teach to an undifferentiated audience (eg laparoscopic skills, obstetrical ultrasound, responding to abnormal pediatric vitals). While it is not feasible to tailor a TTR course to every possible specialty, targeting courses toward the first post-graduate-year (PGY1) experience is a recommended strategy. For example, a student planning to match into neurology may enroll in an internal medicine TTR course since the neurology PGY1 year is largely composed of internal medicine rotations.

Use residents and fellows in course planning and delivery

Resident and fellow contributions to course design help to ensure that content is practical and at the appropriate level 30 and can provide a rich pool of instructors for the course. Many TTR courses already incorporate “resident as teacher” sessions, and therefore using resident teachers in the course helps to model the importance of this skill. Utilizing these near-peer teachers in content delivery creates a safe learning environment and may increase learner buy-in, sense of community, and professional identity formation.

Be flexible

Transition courses occur at the end of medical school when students have many other obligations related to the residency match, paperwork and surveys, and personal milestones. Course instructors should be prepared to receive many requests from students and should be transparent ahead of time about how these will be handled. If make-up work is required, this should be collected in a time-sensitive manner relative to the missed session. Strategies to help aid flexibility include the incorporation of virtual didactics, asynchronous content, and remote assessments when this is appropriate from a pedagogical standpoint (Table 1). Additionally, allowing for some sessions to be optional allows students to design the course around their learning needs and other competing demands.

Kern's step 6: Evaluation and feedback

Include formative assessments of varying domains

Assessments in TTR courses are important for providing formative feedback, assisting in goal setting for the individual learner as they enter residency. Furthermore, student performance on assessments may also help with continuous quality improvement (CQI) of the course. Assessments should target varying domains including medical knowledge, communication skills, and technical skills. Several national societies have developed validated assessments of medical knowledge 31 and checklists for procedural skills. 32 Additionally, some schools have started to incorporate simulated paging curricula33-35 which assess advanced clinical decision-making as well as interprofessional communication.

Anticipate the need for remediation

While assessments are meant to be formative, it may still be necessary for underperforming students to undergo a remediation process, especially for skills that are higher stakes (eg responding to unstable vitals) or skills performed with limited supervision during residency (eg informed consent) (Table 2). Instructors should be transparent ahead of time about which activities may require remediation and block dedicated time for students to engage in such activities. Instructors may benefit from performing standard setting to set the cut-point at which learners should engage in remediation. It is prudent to appropriately allocate resources to ensure sufficient time, equipment, and faculty to complete remediation prior to graduation. From a student perspective, it is imperative that under-performers have the opportunity to improve their skills and bolster self-confidence.

Plan for the cycle of CQI

Since 2015 the Liaison Committee on Medical Education has mandated a process of CQI. 36 A successful TTR course plans for the CQI process from the outset, using student performance data such as entrustable professional activities, surveys of student satisfaction, and surveys of residents who have graduated from the course to determine what is helpful. In addition, when possible, early intern year milestone data should be gathered from residency programs. This process allows for modification of the curriculum based on student feedback, changing medical school curricula, shifting expectations of residents, and incorporation of emerging topics.

Consider an educational handover and follow up with residency programs

TTR courses have the potential to bridge the chasm between medical school and residency. 37 Mapping TTR course assessment data to ACGME milestones can facilitate tracking learner development as well as providing a shared assessment language with residency program directors (Table 2). 38 A post-Match handoff provides an opportunity for transparent, learner-centered communication and is an ideal time for consolidating student performance data to feed forward to residency programs. There are, however, important caveats that should be heeded. First, transparency with the learner is essential since learners may be nervous about communication with their residency program. In addition, learners’ consent may be required. Lastly, one should ensure that any assessment data fed forward is both valid and valuable. Given these challenges, a good starting point for new courses is to feed-forward individual learning goals. This is favored by learners, 39 and is in line with the COPA UGRC recommendations, 4 which highlight the importance of individual goal-setting during the TTR. The process of creating educational handovers has been described for learners entering Emergency Medicine, 40 General Surgery, 38 Pediatrics 41 and Obstetrics and Gynecology 42 residency programs. Ideally, there should be a 2-way communication between medical schools and residency programs, and the process for program directors to provide feedback on individual learners is beginning to be realized 43 through standardization and centralization of program director surveys.

Conclusion

In summary, TTR courses support learners in the critical transition from medical student to resident. Developing and running a TTR course takes planning and faculty time as well as a commitment to a process of CQI. New courses may benefit from using the recommendations shared in this article.

Footnotes

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Matthew Rustici receives grant funding from the nonprofit Macy Faculty Scholars Program and Zell Family Foundation to optimize Transition to Residency. Lauren A. Heidemann, Andrea Anderson, and Katharyn Atkins receive an honorarium for being a participant on a Transition to Residency Editorial board which is sponsored by the nonprofit Macy Faculty Scholars Program and Zell Family Foundation. Lynn Buckvar-Keltz receives institutional support to direct the WISE online educational programs for medical students and early residents.

We declare that each author meets ICMJE authorship criteria. Each author has engaged in substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, drafting and critical review, final approval of this submitted version, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors and each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Lypson ML, Frohna JG, Gruppen LD, Woolliscroft JO. Assessing residents’ competencies at baseline: Identifying the gaps. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2004;79(6):564-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santen SA, Rademacher N, Heron SL, Khandelwal S, Hauff S, Hopson L. How competent are emergency medicine interns for level 1 milestones: Who is responsible? Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(7):736-739. doi: 10.1111/acem.12162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell SG, Kobernik EK, Burk-Rafel J, et al. Trainees’ perceptions of the transition from medical school to residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(5):611-614. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-20-00183.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The coalition for physician accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC): Recommendations for Comprehensive Improvement of the UME-GME Transition. Accessed September 1, 2021. https://physicianaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/UGRC-Coalition-Report-FINAL.pdf

- 5.Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, Kolbe M, Morgan HK. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? A single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(12):2048-2050. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4620-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teo AR, Harleman E, O’sullivan PS, Maa J. The key role of a transition course in preparing medical students for internship. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2011;86(7):860-865. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821d6ae2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart MK, Henry RC, Ehrenfeld JM, Terhune KP. Utility of a standardized fourth-year medical student surgical preparatory curriculum: Program director perceptions. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(3):639-643. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minter RM, Amos KD, Bentz ML, et al. Transition to surgical residency: A multi-institutional study of perceived intern preparedness and the effect of a formal residency preparatory course in the fourth year of medical school. Acad Med. 2015;90(8):1116-1124. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000000680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Germann CA, Strout TD, Park YS, Tekian A. Senior-year curriculum in U.S. Medical schools: A scoping review. Teach Learn Med. 2019;32:34-44. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2019.1618307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elnicki DM, Gallagher S, Willett L, et al. Course offerings in the fourth year of medical school: How U.S. Medical schools are preparing students for internship. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2015;90(10):1324-1330. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACS/APDS/ASE resident prep curriculum. Accessed April 6, 2022. https://www.facs.org/education/program/resident-prep

- 12.Step up to residency program milestone cases. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://apgo.org/page/stepuptorescases?&hhsearchterms=%22transition+and+residency%22

- 13.Bontempo LJ, Frayha N, Dittmar PC. The internship preparation camp at the university of Maryland. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93(1095):8-14. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen ER, Barsuk JH, Moazed F, et al. Making July safer: Simulation-based mastery learning during intern boot camp. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2013;88(2):233-239. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827bfc0a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns R, Adler M, Mangold K, Trainor J. A brief boot camp for 4th-year medical students entering into pediatric and family medicine residencies. Cureus. 2016;8(2):e488. doi: 10.7759/cureus.488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pete Devon E, Tenney-Soeiro R, Ronan J, Balmer DF. A pediatric preintern boot camp: Program development and evaluation informed by a conceptual framework. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(2):165-169. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY, eds. Curriculum development for medical education: A six-step approach. 3rd ed. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyss-Lerman P, Teherani A, Aagaard E, Loeser H, Cooke M, Harper GM. What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):823-829. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a82426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raymond MR, Mee J, King A, Haist SA, Winward ML. What new residents do during their initial months of training. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2011;86(10 Suppl):S59-S62. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822a70ff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rustici M. Transition to residency compendium. Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.ttreducators.com/compendium

- 21.Winkel AF, Yingling S, Jones AA, Nicholson J. Reflection as a learning tool in graduate medical education: A systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):430-439. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00500.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricotta DN, Richards JB, Atkins KM, et al. Self-Directed learning in medical education: Training for a lifetime of discovery. Teach Learn Med. 2022;34:530-5540. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2021.1938074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clay AS, Ming DY, Knudsen NW, et al. CaPOW! using problem sets in a capstone course to improve fourth-year medical Students’ confidence in self-directed learning. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2017;92(3):380-384. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung DYP, Kember D. The influence of teaching approach and teacher-student interaction on the development of graduate capabilities. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 2006;13(2):264-286. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1302_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGaghie WC, Barsuk JH, Wayne DB. Mastery learning with deliberate practice in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(11):1575. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavalcanti M, Fernandes AK, McCallister JW, et al. Post-Clerkship curricular reform: Specialty-specific tracks and entrustable professional activities to guide the transition to residency. Med Sci Educ. 2021;31(2):851-861. doi: 10.1007/s40670-021-01248-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keilin CA, Farlow JL, Malloy KM, Bohm LA. Otolaryngology curriculum during residency preparation course improves preparedness for internship. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(7). doi: 10.1002/lary.29443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang LY, Eliasz KL, Cacciatore DT, Winkel AF. The transition from medical student to resident: A qualitative study of new Residents’ perspectives. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1421-1427. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Merriënboer JJG, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory in health professional education: Design principles and strategies: Cognitive load theory. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):85-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03498.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snell L. The resident-as-teacher: It’s more than just about student learning. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(3):440-441. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00148.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.APGO preparation for residency knowledge assessment tool v.6.5.2021. Accessed June 14, 2022. https://apgo.org/page/prepforres

- 32.Scott DJ, Goova MT, Tesfay ST. A cost-effective proficiency-based knot-tying and suturing curriculum for residency programs. J Surg Res. 2007;141(1):7-15. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.02.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heidemann LA, Blaszczak J, Morrison L, et al. How can registered nurses prepare medical students to be better residents? A qualitative study on feedback in a simulated paging curriculum. J Interprofessional Educ Pract. 2021;24:100454. doi: 10.1016/j.xjep.2021.100454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidemann LA, Kempner S, Walford E, Chippendale R, Fitzgerald JT, Morgan HK. Internal medicine paging curriculum to improve physician-nurse interprofessional communication: A single center pilot study. J Interprof Care. 2020:1-4. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1743246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frischknecht AC, Boehler ML, Schwind CJ, et al. How prepared are your interns to take calls? Results of a multi-institutional study of simulated pages to prepare medical students for surgery internship. Am J Surg. 2014;208(2):307-315. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liason Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school. standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the MD degree. Published online October 2021.

- 37.Morgan HK, Mejicano GC, Skochelak S, et al. A responsible educational handover: Improving communication to improve learning. Acad Med. 2020;95:194-199. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wancata LM, Morgan H, Sandhu G, Santen S, Hughes DT. Using the ACMGE milestones as a handover tool from medical school to surgery residency. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(3):519-529. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heidemann LA, Schiller JH, Allen B, Hughes DT, Fitzgerald JT, Morgan HK. Student perceptions of educational handovers. Clin Teach. 2021;18(3):280-284. doi: 10.1111/tct.13327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sozener CB, Lypson ML, House JB, et al. Reporting achievement of medical student milestones to residency program directors: An educational handover. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):676-684. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiller JH, Burrows HL, Fleming AE, Keeley MG, Wozniak L, Santen SA. Responsible milestone-based educational handover with individualized learning plan from undergraduate to graduate pediatric medical education. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):231-233. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan H, Skinner B, Marzano D, Ross P, Curran D, Hammoud M. Bridging the Continuum: Lessons learned from creating a competency-based educational handover in obstetrics and gynecology. Med Sci Educ. 2016;26(3):443-447. doi: 10.1007/s40670-016-0266-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Howley L, Grbic D, Speicher MR, Roskovensky LB, Jayas A, Andriole DA. The resident readiness survey: A national process for program directors to provide standardized feedback to medical schools about their graduates. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15(5):572-581. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-23-00061.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]