Abstract

Objective

Numerous studies have highlighted the role of clock genes in diabetes disease and pancreatic β cell functions. However, whether rhythmic long non-coding RNAs involve in this process is unknown.

Methods

RNA-seq and 3’ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)-PCR were used to identify the rat LncCplx2 in pancreatic β cells. The subcellular analysis with qRT-PCR and RNA-Scope were used to assess the localization of LncCplx2. The effects of LncCplx2 overexpression or knockout (KO) on the regulation of pancreatic β cell functions were assessed in vitro and in vivo. RNA-seq, immunoblotting (IB), Immunoprecipitation (IP), RNA pull-down, and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR assays were employed to explore the regulatory mechanisms through LncRNA-protein interaction. Metabolism cage was used to measure the circadian behaviors.

Results

We first demonstrate that LncCplx2 is a conserved nuclear long non-coding RNA and enriched in pancreatic islets, which is driven by core clock transcription factor BMAL1. LncCplx2 is downregulated in the diabetic islets and repressed by high glucose, which regulates the insulin secretion in vitro and ex vivo. Furthermore, LncCplx2 KO mice exhibit diabetic phenotypes, such as high blood glucose and impaired glucose tolerance. Notably, LncCplx2 deficiency has significant effects on circadian behavior, including prolonged period duration, decreased locomotor activity, and reduced metabolic rates. Mechanistically, LncCplx2 recruits EZH2, a core subunit of polycomb repression complex 2 (PRC2), to the promoter of target genes, thereby silencing circadian gene expression, which leads to phase shifts and amplitude changes in insulin secretion and cell cycle genes.

Conclusions

Our results propose LncCplx2 as an unanticipated transcriptional regulator in a circadian system and suggest a more integral mechanism for the coordination of circadian rhythms and glucose homeostasis.

Keywords: LncCplx2, Glucose homeostasis, Pancreatic β cell, Insulin secretion

Highlights

-

•

LncCplx2 is a rhythmic nuclear long non-coding RNA and highly enriched in pancreatic islets.

-

•

LncCplx2 regulates pancreatic β cell functions in vitro and in vivo.

-

•

LncCplx2 regulates circadian clock genes expression through interaction with EZH2.

-

•

LncCplx2 KO mice exhibit overt diabetic phenotypes and disrupt circadian behaviors.

1. Introduction

Circadian rhythms adapt organisms to their daily surroundings in behavior and physiology. In mammals, circadian rhythms are driven by a web of cell-autonomous and self-sustained oscillators, which include the central oscillator within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, and the peripheral oscillator present in nearly every cell of the body [1]. At the cellular level, the molecular mechanism responsible for driving the circadian oscillator comprises three interlocked transcriptional feedback loops [2]. The core components of circadian clock are the transcription factor CLOCK and its heterodimeric partner BMAL1, which binds to regulatory elements containing E-boxes [3]. In a secondary feedback loop, the BMAL1/CLOCK complex controls the rhythmic expression of nuclear receptors REV-ERBα/β and RORα/β/r [4]. In turn, REV-ERBα/β and RORα/β/r compete the ROR response elements (RORE) to control the expression of BMAL1 and NFIL3 [4]. The third BMAL1/CLOCK driven transcriptional loop involves D-box binding protein (DBP), thyrotroph embryonic factor (TEF), and hepatic leukemia factor (HLF), which interact with repressor nuclear factor interleukin-3 regulated protein (NFIL3) at D-box elements to fine-tune the circadian rhythms of PER1/2 and RORα/β/r transcripts [5].

Numerous studies have revealed that islet clock genes play a central role in the control of insulin secretion and the development of diabetes [6,7]. For instance, studies performed in whole-body, pancreas-specific, and β cell-specific Clock or Bmal1 knockout (KO) mice exhibit diabetic phenotypes, including hyperglycemia, hypoinsulinemic and impaired glucose tolerance [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. The diabetic phenotypes are associated with impaired insulin secretion and β cell proliferation [10,11]. Consistent with these in vivo findings, in vitro or ex vivo experiments revealed that disturbed clock was sufficient to impair glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) function in β cells [12,13]. The molecular mechanism underlying the circadian control of insulin secretion involves the binding of BMAL1/CLOCK complexes to distinct enhancers, which regulate time-dependent transcription of key exocytosis and metabolic genes in β cells [10]. In contrast to the hypoinsulinemic phenotype observed by Bmal1 or Clock KO mice, the repressor gene period 2 (Per2) KO mice showed an enhanced GSIS function [14], and cryptochrome deficient (Cry1 and Cry2 double KO) mice were hyperinsulinemic [15].

LncRNA is considered as a class of non-coding RNAs without open reading frames, which is over 200 nt in length [16]. Recently, some small ORFs encoding functional micropeptides have been identified in LncRNAs [17]. Several studies identified groups of LncRNA showed circadian oscillations, which is under the control of circadian clock genes, and in turn, they have the potential impact on circadian biology or other specific function of tissues [18,19]. For example, a class of rhythmic LncRNAs, mostly regulated by BMAL1 and REV-ERBα, are involved in the metabolic homeostasis in the mouse liver [18,19]. In our previous study, we found a pancreatic islets enriched LncRNA anti-sense to Cplx2, namely LncCplx2, is downregulated in the islets of diabetic Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats by RNA-seq analysis [20], as it was described in the atlas of circadian rhythmic LncRNAs in the rat pineal gland [21]. In this study, we found that LncCplx2 regulates pancreatic β cell functions in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, LncCplx2 recruits EZH2, a core subunit of PRC2, to the promoter of target genes, leading to suppress the circadian genes expression. Accordingly, LncCplx2 deficiency causes overt diabetic phenotypes and disrupts circadian behaviors in mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Min6 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) medium containing 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. INS1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK)-293T cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. All the cells were placed in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.2. Construction of LncCplx2, Cplx2 or Bmal1 KO cells and LncCplx2-rescued or overexpressed cells and Bmal1 knockdown cells

LncCplx2, Cplx2 or Bmal1 KO Min6 cells were generated using CRISPR-Cas9. For LncCplx2 KO cells, in order to avoid damaging the structure of the Cplx2 gene, two sgRNAs were designed to cut out the second exon of LncCplx2, which account for the 90% of LncCplx2 region. For Cplx2 KO cells, two sgRNAs were designed to induce shift mutation of Cplx2 gene reading frame, but not destruction of the LncCplx2 transcript. For Bmal1 KO cells, two sgRNAs were designed to induce shift mutation of Bmal1 gene reading frame. One of the gRNAs was subcloned into the pLenti-CRISPR-V2 vector. The second gRNA was subcloned into a modified version of the pLenti-CRISPR-V2-BSD vector, in which the puromycin selection marker was substituted with a blasticidin selection marker. CRISPR plasmids were transiently transfected into HEK-293T cells together with pAdVAntage, VSVG and psPAX2 with a ratio 10:1.7:1:5. The HEK-293T culture media containing lentiviral particles were collected consecutively for two rounds and centrifuged in a Beckman SW 32 Ti rotor (Optima XPN-100) at 100,000 g for 1.5 h at 4 °C. Viral pellets were resuspended in PBS and used to infect target cells. Infected cells were sequentially selected using 1 μg/mL puromycin and 1 μg/mL blasticidin.

The LncCplx2-rescued cells or overexpressed cells were constructed with the lentiviral pLVX-IRES-Puro plasmid in LncCplx2 KO Min6 cells or INS1 cells, respectively. Lentivirus was packaged by transfecting HEK-293T cells with pLVX-LncCplx2 plasmids and two packaging plasmids psPAX2 and VSVG with a ratio 4 : 3: 1. At 48 h posttransfection, the virus-containing supernatant was collected as above described, filtered and used to infect Min6 cells. The infected cells were selected and maintained with puromycin.

The Bmal1 knockdown Min6 cells was constructed with shBmal1 plasmids. Briefly, 5 shRNA plasmids targeting different regions of Bmal1 and a control shRNA plasmid (scrambled) were used to transfect Min6 cells with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, L3000001), and positive cells were selected with G418 (Invitrogen, 11811023) for 2 weeks. qRT-PCR were used to determine the Bmal1 expression level. The sequences of gRNA, shRNA are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

2.3. Animals

LncCplx2 KO mice were generated by GemPharmatech using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Since the LncCplx2 is an antisense RNA, in order to avoid damaging the structure of the Cplx2 gene, the two sgRNAs were designed to cut out the second exon of LncCplx2, which account for the 90% of LncCplx2 region. Cas9 mRNA and sgRNAs were co-injected into the fertilized eggs of C57BL/6JGpt mice. The fertilized eggs were transplanted to form positive F0 mice, which were confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing. A stable F1 generation mouse model was obtained by mating positive F0 generation mice with C57BL/6JGpt mice. Mice were housed in groups of three to five at 22–24 °C with a 12-h LD cycle. Animals had access to water ad libitum. All mice used in this study were gender- and age-matched. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the Institute of Biophysics (License No. SYXK2021093).

2.4. Islet isolation

Pancreatic islets were isolated by collagenase digestion as described previously [20]. Briefly, the pancreas was inflated by instilling 5 mL of Hanks' buffered saline solution (HBSS) containing 0.5 mg/mL collagenase P through the pancreatic duct. The pancreas was harvested and incubated in a water bath at 37 °C for 25 min. The digested pancreas was rinsed with HBSS, and islets were separated on a Ficoll density gradient. After three washes with HBSS, the islets were manually isolated under a dissection microscope.

2.5. GSIS

Isolated islets were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 with 5.6 mM glucose for about 24 h. After washed with PBS, islets, Min6 or INS1 cells were pre-incubated for 1 h in 2.8 mM glucose Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate HEPES buffer (KRBB) containing: 114 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.16 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM CaCl2, and 20 mM HEPES with 0.2% BSA, pH 7.4. Next, groups of islets, Min6 or INS1 cells were batch-incubated in 0.2 mL, 2.8 mM glucose in KRBB for 1 h. Incubation medium was withdrawn for insulin measurement after gentle agitation and was replaced by 0.2 mL fresh KRBB solution supplemented with 16.8 mM glucose. For islets, all operations were conducted under dissection microscopy to avoid damaging the islets. Insulin was quantified by ELISA with commercially available kits.

2.6. Serum insulin measurements

For serum insulin detection, the mice were fasted for 12 h, then blood samples were collected into centrifuge tubes from the mouse orbital vein with no anti-coagulant. The clotted blood was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min to obtain serum. The supernatant serum was transferred into a clean tube and was analyzed using Rat/Mouse Insulin ELISA kit (Sigma-Aldrich, EZRMI-13K).

2.7. Glucose tolerance test

Glucose tolerance tests were performed in mice fasted for 12 h, blood glucose was measured after intra-peritoneal (i.p.) glucose injection of 2 g/kg body weight. Blood glucose was measured at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min from tail vein blood samples.

2.8. Islet size measurements

Pancreases were dissected from paired WT and LncCplx2 KO mice and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24 h. After dehydration, the samples were embedded in paraffin. We studied islet morphology for each section using H&E staining. 5 μm pancreas paraffin sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated before staining with hematoxylin solution for 5 min, followed by dips in 1% acid ethanol (1% HCl in 70% ethanol) and rinsed in distilled water. The sections were then stained with eosin for 3 min, dehydrated with graded alcohol and cleared in xylene. The sections were scanned with a Leica Aperio Versa 200 and Nikon DS-Ri2. Islet size and number of islets/mm2 were analyzed by Fiji-ImageJ software.

2.9. Polysome profile

INS1 cells were treated with 100 μg/mL cycloheximide for 10 min at 37 °C, and digested by 0.05% trypsin–EDTA for 5 min and wash twice with cold PBS buffer. Lysis buffer composed with 15 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2, 300 mM NaCl, 100 μg/mL cycloheximide, 1% Triton X-100, 40 U/μL RNAseOut and 24 U/mL DNAse was used to resuspend cells, and incubated on ice for 10 min, then centrifugated 5 min at 12,000 × g at 4 °C to remove nucleus. The supernatant was gently retrieved and floated on a 10–50% continuous sucrose gradient diluted with lysis buffer without NP40 in a SW40 tube. The samples were then centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 3 h at 4 °C. Sucrose gradient fractions were collected and concentrated by an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, followed by ethanol precipitation for the subsequent qRT-PCR analysis.

2.10. RNA-scope (RNA in situ hybridization)

The in situ hybridization was performed using the RNA-scope 2.5 HD Reagent Kit-BROWN (ACDBio, 322300) according to the manufacturers' instructions. The RNA-Scope probes were as follows: Mm-LNCCPLX2-01-C1 (ACDBio, 1090001) targeted LncCplx2, Negative Control Probe (ACDBio, 320871) and Positive Control Probe (ACDBio, 320881). The RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization was performed following protocol of RNA-scope Multiplex Fluorescent Regent Kit V2 (ACDBio, 323100) and RNA-Protein Co-Detection Ancillary Kit (ACDBio, 323180). LncCplx2 probe co-labeled with two primary antibodies, insulin (Abcam, ab7842) and glucagon (Proteintech, 67286-1-Ig), with Opal fluorophores 520 Reagent (Akoya Biosciences, FP1487001KT) for glucagon, secondary antibody Rhodamine (TRITC) AffiniPure Goat Anti-Guinea Pig IgG (H + L) (Jackson IR, 106-025-003) for insulin, Opal fluorophores 650 Reagent (Akoya Biosciences, FP1496001KT) for LncCplx2. The mounted pancreas slices with DAPI were examined and photographed by Nikon DS-Ri2 and PerkinElmer Vectra 3 Automated Quantitative Pathology Imaging System.

2.11. RNA-seq

Total RNA was prepared with TRIzol regent (Invitrogen, 15596018) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing libraries were synthesized using the Hieff NGS Ultima Dual-Mode RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (YEASEN, 12252ES) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 PE150 (BerryGenomics). RNA raw sequence reads were aligned to the reference genome using STAR version 2.7.2b, and the raw and transcripts per million (TPM) count values were determined using RSEM version 1.3.3. Differentially expressed RNAs were identified by padj < 0.05 and |Log2 fold change| > 2 using DESeq2 version 1.32.0 in R 4.2.0. Interaction network were generated by the STRING database, confidence score was 0.7. The GO biological process enrichments were performed by clusterProfiler version 4.8.1 Raw mRNA sequence data have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa) with accession number CRA008428.

2.12. Analysis of LncCplx2 expression in islets of healthy and diabetic patients

The raw fastq files were downloaded from the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) with the accession: PRJNA690574 (GEO: GSE164416). Raw sequence reads were aligned to the reference genome (hg38) using hisat2 version 2.2.0. Read count was calculated using htseq-count version 0.9.1 and the Gencode annotation file (v39). The read count of LncCPLX2 were calculated using samtools, and TPM values were estimated with the consideration of total mapped reads and gene length. The BMI values of normal and diabetic group were kept within the same range of 28, and HbA1c values were less than 6 in the healthy group and more than 6 in the diabetic group (n = 18).

2.13. Metabolism cage

Mice were acclimated into CLAMS metabolic cage (Columbus Instruments) housing for one week before measurements were taken under a 12-h light–dark (LD) cycle. O2 consumption, CO2 production, energy expenditure, RER, feeding behavior and locomotor activity were measured with the CLAMS 6-chamber comprehensive monitoring system. Locomotor activity was determined as ambulatory counts when a series of infrared beams were interrupted sequentially on the horizontal X-axis/Y-axis (XAMB/YAMB), and feeding behavior was determined as ambulatory counts when a series of infrared beams were interrupted on the vertically (ZTOT).

To estimate the free running period of circadian rhythms, Chi-square periodogram analysis was applied for the free running period estimation, which was performed by calculating the Qp values of various possible periods [22]. The Qp values follow a probability distribution of χ2 when there are at least 10 cycles of circadian rhythm, and they were calculated by using the R package spectr [23,24]. The estimated period corresponding to the most significant Qp values was considered as the true free running period.

The active time was identified when the activity was equal to or greater than 10% mean activity of the top five peak activities on each day and at least 3 of the 6 following time points also met the criterion. And the main activity time was defined as between the first active time and the last active time during each day. The active onset and offset (min) were shown as the buffering time before the start of the main activity time or after the end of the main activity time which was caused by the delayed LD cycle. In-house developed R functions were used to analyze the activity data of mice, including the identification of active time and the calculation of activity onset and offset. The visualization of mice activity was performed with the R package ggplot2.

2.14. ChIP

ChIP-PCR was performed in Min6 cells or pancreatic islets using the Magnetic ChIP Kit (Pierce, 26157) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Briefly, Min6 cells or pancreatic islets were cross-linked by 1% formaldehyde (Invitrogen, 28908) for 10 min at room temperature, then quenched with glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM for 5 min. Sonication of cell lysis was performed by a ME220 Focused-ultrasonicator (Covaris). BMAL1 (Invitrogen, PA1-46118), E4BP4 (Proteintech, 11773-1-AP), NR1D1 (Proteintech, 14506-1-AP) and EZH2 (Invitrogen, 36–6300) antibody were used to pull down chromatin. Normal mouse/rabbit IgG or RNA Polymerase II antibodies (provided by ChIP kit) were used as the negative or positive control, respectively. ChIP-qPCR signals were calculated as fold enrichment of 1% input or non-specific antibody (isotype IgG antibodies) signals with at least two technical triplicates.

2.15. Luciferase reporter assay

LncCplx2 promoter region and a scrambled region were cloned into pGL6 luciferase vector. HEK-293T Cells were cotransfected with luciferase reporter, pRL-TK, and Bmal1 overexpression plasmid. After 24-h transfection, cells were lysed and luciferase activities were determined using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System and luminometer (BioTek SYNERGY NEO2). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to renilla luciferase activity and expressed as relative luciferase unit.

2.16. RNA pull down

The LncCplx2 was cloned into T7 promoter–based vector. The LncCplx2 transcript and its antisense transcript were in vitro transcribed using biotin RNA labeling mix with T7 RNA polymerase or SP6 RNA polymerase. The mixtures were treated with RNase free DNase I and purified with TRIzol. Biotinylated RNAs were incubated with 20 μL of streptavidin C1 magnetic beads (Invitrogen, 65001) at room temperature for 30 min, and then incubated with nuclear proteins at 4 °C for 1 h. Proteins were eluted from the beads with elution buffer. The pulldown proteins were run on SDS-PAGE gels and followed IB analysis.

2.17. IP of RNP complexes

Pancreatic β cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde and lysed in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40 and 1% proteinase inhibitor for 30 min on ice and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were incubated with protein A/G magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher, 88802) coated with an anti-EZH2 antibody (Invitrogen, 36-6300) or control IgG (Invitrogen, 02-6102) overnight at 4 °C. Then, the beads were washed three times with wash buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.05% NP-40. The precipitates were incubated with 20 U of RNase-free DNase I for 15 min at 37 °C to remove DNA and were incubated further with 0.1% SDS/0.5 mg/mL Proteinase K at 55 °C for 15 min to remove proteins. The RNA isolated by IP was further analyzed by PCR.

2.18. 3′ RACE assay

3′ RACE was performed with Roche 3′ RACE kit (Roche, 3353621001) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RACE PCR productions were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel. Gel production were extracted with a Gel Extraction kit and sequenced.

2.19. qRT-PCR

Total RNA from GK rat islets, ob/ob and db/db mouse islets or cells was prepared with TRIzol regent according to the manufacturer's instructions, and then reverse transcribed by SuperQuick RT MasterMix. qRT-PCR was performed with cDNA (1:20 dilution), 2xSYBR Green PCR Mix, and specific primers (10 mM) listed in Supplementary Table S4 by QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR Systems (Applied Biosystems). The 18S or Gapdh primers were used for normalization, and ΔCt was calculated to determine the relative expression levels.

2.20. IB

Whole-cell lysates prepared using RIPA buffer containing a proteinase inhibitor were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against Tubulin (Proteintech, 66031-1-Ig), DDX1 (Proteintech, 11357-1-AP), SETD8 (Abcam, ab111691), HistoneH3 (Invitrogen, PA5-16183), CPLX2 (Proteintech, 18149-1-AP), BMAL1 (Invitrogen, PA1-46118), E4BP4 (Proteintech, 11773-1-AP), NR1D1 (Proteintech, 14506-1-AP), EZH2 (Invitrogen, 36-6300), and β-actin (Sigma Aldrich, A1978), followed by the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Proteintech, SA00001-2/SA00001-1), and protein expression was detected with enhanced luminescence reagents (GE Healthcare, RPN2106).

2.21. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were acquired from more than two independent experiments, values were expressed as means ± SEM. Significance was calculated by two-tailed paired Student's t-test when two independent groups were compared. Two-way ANOVA was applied for multiple groups comparisons. P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 8.

3. Results

3.1. LncCplx2 is a conserved nuclear long non-coding RNA and enriched in pancreatic islets

Our previous study revealed a long non-coding RNA anti-sense Cplx2, termed LncCplx2, was downregulated in islets of diabetic Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats by RNA-seq analysis [20]. Full-length RNA-seq and Poly A+ 3′ end RNA-seq profiles indicated that LncCplx2 was a short isoform with a different 3′ end terminal in pancreatic β cells (Figure S1a), which was confirmed by the 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)-PCR (Figure S1b and Supplementary Table S1). RNA-seq analysis indicated that LncCplx2 transcript was highly species-conservative in mice and humans (Figure S1c). LncCplx2 showed the oscillatory expression pattern by serum shock in pancreatic β cells (Figure S1d), similar to the expression pattern described in the circadian rhythmic LncRNA atlas of the rat pineal gland [21]. The in silico and polysome profile results showed that LncCplx2 was a non-coding transcript (Figures 1A, S1e and S1f). Further, a quantitative tissue distribution assay using qRT-PCR showed that LncCplx2 was highly expressed in mouse pancreatic islets (Figure 1B). The subcellular analysis showed that the LncCplx2 was almost located in the insoluble nuclear pellet along with the corresponding RNA and protein markers (Figure 1C). Consistently, RNA-Scope with H&E staining as well as staining of β cells and α cells showed that LncCplx2 mainly located in the nucleus of β cells (Figures 1D and S1g). Intriguingly, LncCplx2 was downregulated in the islets of diabetic GK rats, diabetic ob/ob and db/db mice, as well as diabetic patients (Figures S2a–d). Furthermore, LncCplx2 expression was significantly repressed in INS1 and Min6 cells treatment with high glucose for 24 h and 48 h, respectively (Figures S2e–S2g). Collectively, LncCplx2 is a conserved nuclear long non-coding RNA that is highly enriched in pancreatic islets and regulated by glucose.

Figure 1.

LncCplx2 is a nuclear long non-coding RNA enriched in pancreatic islets. (A) Analysis of the relative distribution of LncCplx2 and Insulin mRNA on polysome gradients in INS1 cells. (B) Analysis of LncCplx2 expression by qRT-PCR in mouse tissues (n = 3). (C) Analysis of LncCplx2 expression by qRT-PCR in INS1 cells following cell fractionation. The cytoplasm (Cyt), soluble nuclear (Nuc) and insoluble nuclear pellet (Pel) fractions were verified using specific markers through qRT-PCR and IB, respectively (n = 2). (D) RNA-scope images showing nuclear localization of LncCplx2 in mouse islets. LncCplx2 KO mouse islets were used as a negative control. Scale bar, 50 μm. The red arrowheads point the LncCplx2 signals (n = 4). All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01, using two-tailed Student's t-test.

3.2. LncCplx2 regulates pancreatic β cell functions in vitro and in vivo

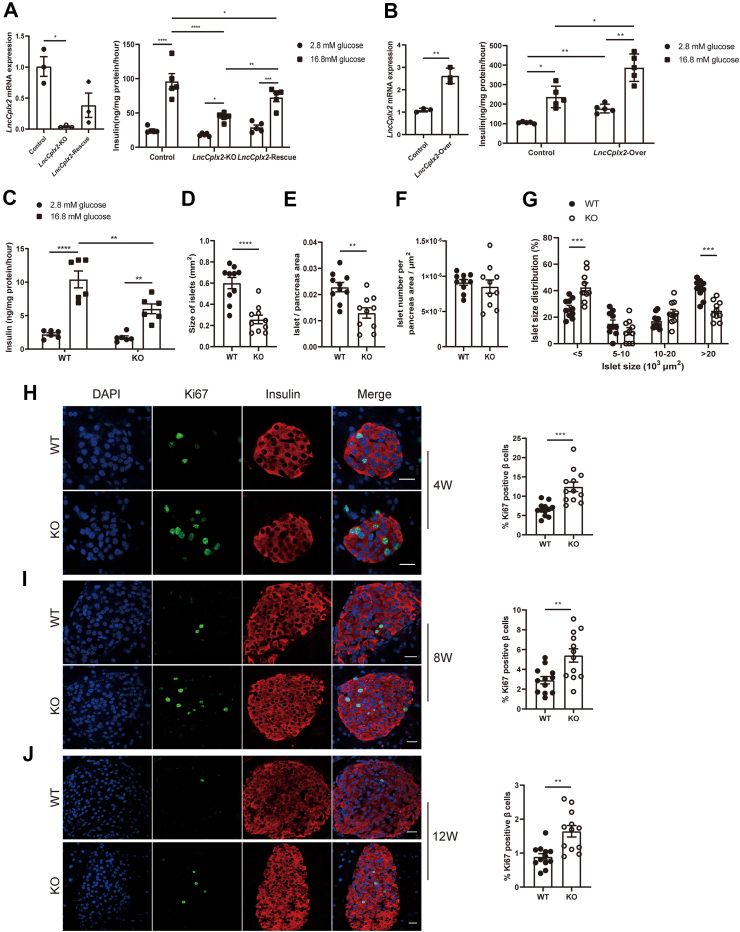

To explore the potential role of LncCplx2 in regulating β cell function, we generated a LncCplx2 KO Min6 cell line via the CRISPR-Cas9 technique. LncCplx2 deficiency significantly impaired the GSIS function of Min6 cells (Figure 2A). Notably, when LncCplx2 expression was partially restored in the LncCplx2 KO cells, GSIS function was also partially restored (Figure 2A). Consistently, overexpression of LncCplx2 increased insulin secretion in INS1 cells (Figure 2B). These results suggest that LncCplx2 plays a role in regulating insulin secretion in vitro. To verify whether LncCplx2 also regulates insulin secretion in vivo, we generated whole body LncCplx2 KO mice via the CRISPR-Cas9 technique with the same sgRNAs (Figure S3a–c). The LncCplx2 KO mice showed efficient depletion of LncCplx2 expression in pancreatic islets (Figures 1D and S3d). Consistently, insulin secretion was markedly impaired in LncCplx2 KO islets compared to wild-type (WT) islets (Figure 2C). All these results suggest that LncCplx2 regulates insulin secretion in vitro and ex vivo.

Figure 2.

LncCplx2 regulates pancreatic β cell function in vitro and in vivo. (A) GSIS in LncCplx2 KO and LncCplx2-rescue Min6 cells compared to control cells (n = 5). (B) GSIS in LncCplx2 overexpressed INS1 cells compared to control cells (n = 5). (C) GSIS in ex vivo islets isolated from WT and LncCplx2 KO mice (n = 6, 12 weeks, male). (D–F) Comparison of size of islets (D), islet area per pancreas (E) and islet number per pancreas area (F) between WT and LncCplx2 KO mice (n = 10, 12 weeks, male). (G) Distribution of different-sized islets in WT and LncCplx2 KO mice (n = 10, 12 weeks, male). (H–J) Representative immunostaining of Ki67 for β cells (staining insulin) proliferation in WT and LncCplx2 KO mice at 4 (H), 8 (I), and 12 (J) weeks (left). Scale bar, 10 μm. The quantitative analysis is shown in right panel (n = 12). All the data are shown as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, using two-tailed Student's t-test and two-way ANOVA.

However, it was observed that the protein level of CPLX2 was significantly decreased in LncCplx2 KO pancreatic islets and Min6 cells (Figure S4a and b). To rule out the possibility that the LncCplx2-deficient phenotypes was due to reduced CPLX2 protein levels. Firstly, we examined whether CPLX2 protein levels could be restored in LncCplx2-rescued cells. The results showed that CPLX2 protein levels remained unchanged (Figure S4b), while GSIS function could be partially rescued in the LncCplx2-rescued cells (Figure 2A), suggesting that the impaired insulin secretion was primarily due to LncCplx2 deficiency rather than reduced CPLX2 protein levels. Furthermore, two Cplx2 KO Min6 cell lines were generated using CRISPR-Cas9 to induce a shift mutation in the Cplx2 gene reading frame without disrupting the LncCplx2 transcript (Figure S4c). The results showed that GSIS function was not changed after Cplx2 deficiency (Figure S4d), indicating that other CPLX family proteins might compensate for CPLX2 deficiency. Indeed, previous studies have shown that only the double KO of Cplx1 and Cplx2 resulted in decreased vesicle release in neuronal cells [15]. Taken together, these results showed that impaired insulin secretion is primarily caused by LncCplx2 deficiency rather than reduced CPLX2 protein levels.

We next examined the morphology of pancreatic islets and found it to be comparable between age-matched WT and KO islets. However, quantification indicated that the islet size and islet size per pancreas area were significantly decreased in KO mice (Figure 2D and E). Interestingly, there was no significant change in the number of islets in KO mice compared to WT littermates (Figure 2F), indicating that LncCplx2 deficiency may affect islets proliferation. Furthermore, there was a significant reduction in the percentage of large islets and a significant increase in the percentage of small islets in KO mice compared to WT littermates (Figure 2G), which is consistent with the phenotypes observed in Clock or Bmal1 KO mice [9]. To further confirm whether LncCplx2 regulates islets proliferation, we performed the immunostaining Ki67 in LncCplx2 deficient islets. The results showed that the Ki67 positive β cells were significantly increased in LncCplx2 deficient islets (Figure 2H–J), suggesting that LncCplx2 deficiency increases β cells proliferation. These findings indicate that LncCplx2 deficiency also affects islet proliferation and mass.

3.3. LncCplx2 regulates circadian clock genes expression

To elucidate the underlying mechanism by which LncCplx2 regulates islet functions, a global transcriptome analysis was performed on isolated islets from WT and LncCplx2 KO mice. A total of 374 differential expression genes (DEGs) were identified, of which 362 genes were up-regulated and 12 genes were down-regulated in the LncCplx2 KO islets (Figure 3A, and Supplementary Table S2), indicating that LncCplx2 is more likely to repress gene expression. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis showed significant enrichment in the process of MAPK signaling pathway, protein folding, rhythmic process and inflammatory response (Figure 3A). Intriguingly, STRING analysis showed that the interaction complexes were significantly enriched in rhythmic process, immediate-early gene, and chaperones-mediated autophagy (Figure 3B), which are known regulators of circadian rhythm. Examples of such genes include Per1, Sik1, and Ciart, which are core circadian transcription factors [[25], [26], [27]]. The AP-1 transcription factors c-Fos, Fosb and Junb, the zinc-finger protein Egr3, and the orphan receptor Nr4a1, are classic immediate-early genes that are important for light-induced phase-shifting of the circadian clock [28]. The LncCplx2 deficient-induced chaperones, including Dnajb1, Hsph1, Hspa1a, and Hspa1b, are the components of the chaperone-mediated autophagy pathway, which contributes to the rhythmic removal of clock machinery proteins [29,30]. qRT-PCR results further confirmed the significant increase in the expression of several DEGs in LncCplx2 KO pancreatic islets and Min6 cells (Figure 3C and D). Notably, no significant changes were observed in Cplx2 KO cells (Figure S4e), suggesting that it is LncCplx2, rather than Cplx2, that regulates circadian gene expression.

Figure 3.

LncCplx2 deficiency increases circadian gene expression. (A) Volcano plot (left) displaying RNA-seq analysis of islets from WT (n = 4) and LncCplx2 KO mice (n = 4) at 16 weeks. DEGs (Log2 Fold Change KO/WT >2 or <−2 with padj <0.05) are represented as red dots, with 362 genes upregulated and 12 genes downregulated. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis (right) of DEGs affected by LncCplx2 deficiency. (B) Interaction network of DEGs based on the STRING database. Nodes are colored as indicated terms. (C–D) qRT-PCR analysis of DEGs in LncCplx2 KO islets(c) (n = 4) and LncCplx2 KO Min6 cells (D) (n = 4). All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, using two-tailed Student's t-test.

It has been demonstrated that the molecular mechanism underlying circadian genes control of islet functions was through the regulation of time-dependent transcription of key exocytosis and metabolic genes in β cells [9,10,14]. We next sought to examine the differential rhythmic transcription of insulin secretion and cell cycle genes, every 4-h over a 24-h light–dark cycle by qRT-PCR in isolated islets from the WT and LncCpx2 KO mice. As expected, all the examined genes showed circadian oscillations in the WT islets (Figure S5). Strikingly, LncCplx2 deficiency significantly augmented the oscillatory amplitude of InsR (Figure S5). Conversely, the oscillatory amplitude of key β cell transcriptional factor NeuroD1 was significantly decreased in the LncCpx2 KO islets (Figure S5). In addition, the oscillatory amplitudes of Ins1, Gck and cyclinD1 were also changed but without statistical significance in the LncCpx2 KO islets. Furthermore, LncCplx2 deficiency leaded to the phase shift of transcriptional waves regarding insulin signaling genes (Irs2, Akt2, and Pi3k) (Figure S5). However, no significant change in oscillatory expression pattern of Pdx1 was observed (Figure S5). Taken together, these results show that LncCplx2 plays a role in modulating the rhythmic transcriptional waves of these genes, which are crucial for β cell function and insulin secretion.

3.4. LncCplx2 expression is regulated by the clock transcription factor BMAL1

Circadian gene expression is generally driven by a transcriptional mechanism in which core clock genes act on three cis-elements (E-box, RORE, and D-box) in the target gene promoter region [2]. To investigate the potential transcriptional factor that directly regulates the LncCplx2 expression, the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR assay was performed with specific antibodies targeting BMAL1, E4BP4 and NR1D1, which represent cis-acting proteins for E-box, RORE, and D-box, respectively. As a positive control, we found that the LncCplx2 promoter region was significantly enriched by the anti-RNA Polymerase II (Pol II) antibody (Figure 4A), confirming the specificity of the assay. Strikingly, the LncCplx2 promoter region could be enriched by the anti-BMAL1 antibody, but not by the anti-E4BP4 and anti-NR1D1 antibodies, compared to the enrichment attained by IgG (Figure 4A), implying that the expression of LncCplx2 may be regulated by BMAL1. Consistently, the expression of LncCplx2 was significantly increased in the Bmal1 KO and knockdown Min6 cells (Figure 4B–D), supporting the notion that BMAL1 negatively regulates LncCplx2 expression. Furthermore, we found a 1-kb LncCplx2 promoter could increase the activity of luciferase reporter (Figure 4E). However, overexpression of Bmal1 inhibited the activity of the luciferase reporter driven by a 1-kb LncCplx2 promoter, but does not affect the activity of the luciferase reporter driven by a negative control and vector luciferase reporter (Figure 4E). Interestingly, Bmal1 KO eliminated the high glucose-induced repression of LncCplx2 expression, suggesting that high glucose downregulates LncCplx2 through BMAL1 (Figure S2h). Taken together, these results suggest that BMAL1 regulates LncCplx2 expression at the transcriptional level.

Figure 4.

LncCplx2 expression is regulated by BMAL1. (A) ChIP-qPCR assays demonstrating enrichment of BMAL1 at the LncCplx2 promoter region in Min6 cells. RNA Polymerase II antibody and IgG serve as the positive and negative control, respectively (n = 3/2). Two different primer pairs (LncCplx2-P1 and LncCplx2-P2) targeted the promoter of LncCplx2 were used for the PCR assay. IB analysis of BMAL1, NR1D1 and E4BP4 antibody immunoprecipitation efficiency, IgG as negative control. (B) IB analysis of BMAL1 protein level in Bmal1 KO and control Min6 cells. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (C) LncCplx2 expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR in Bmal1 KO and control Min6 cells (n = 4). (D) qRT-PCR analysis of Bmal1 and LncCplx2 expression in Min6 cells expressing two shRNAs targeting Bmal1 and scrambled shRNA as control (n = 3). (E) Effects of Bmal1 overexpression on different luciferase reporter activity driven by the LncCplx2 promoter and negative control (n = 6). All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, using two-tailed Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA.

3.5. LncCplx2 interacts with EZH2 to repress gene expression

To investigate the molecular mechanism underlying LncCplx2 regulation of gene expression, we first explored the LncCplx2-interacting proteins using a pull-down assay. LncCplx2 mainly represses gene expression, which promoted us to examine whether LncCplx2 interacts with PRC2, a transcriptional repressor complex, to repress target gene expression [31]. RNA pull-down results showed that the core subunit of PRC2, EZH2, was pulled down by the LncCplx2 transcript, but not by the control LncCplx2 antisense transcript (Figure 5A). Conversely, RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) results showed that LncCplx2 transcript was significantly enriched by anti-EZH2 RIP compared to the enrichment attained by IgG RIP (Figure 5B). Taken together, these results indicate that LncCplx2 interacts with EZH2. We sought to perform a ChIP assay to investigate the binding of EZH2 to the promoter region of Per1, one of the up-regulated DEGs in pancreatic islets due to LncCplx2 deficiency. ChIP-PCR results indicated a significant enrichment of EZH2 to Per1 promoter region (Figure 5C), consistent with previous results [32]. Strikingly, LncCplx2 deficiency significantly decreased the enrichment of EZH2 to Per1 promoter region (Figure 5D). Therefore, we speculate that LncCplx2 recruits EZH2 to the promoter of target genes, thereby silencing gene expression.

Figure 5.

LncCplx2 interacts with EZH2 to regulate gene expression. (A) IB analysis showing EZH2 pulled down by LncCplx2 sense RNA transcript. Biotinylated LncCplx2 was transcribed in vitro, and subjected to pull down interaction proteins, whereas antisense RNA served as the control. The LncCplx2-associated proteins captured by streptavidin beads were subjected to western blot analysis with specific anti-EZH2 antibody. Two independent experiments were performed. (B) RIP assays demonstrating that EZH2 could pull down the LncCplx2 transcript. IB analysis of IP using an anti-EZH2 antibody, followed by RT-PCR analysis of the LncCplx2 pulled down by the anti-EZH2 antibody. Two independent experiments were performed. (C) ChIP-qPCR assays showing enrichment of EZH2 at the Per1 promoter region in Min6 cells (n = 3). IB analysis of EZH2 antibody immunoprecipitation efficiency, IgG as negative control. (D) ChIP-qPCR assays showing decreased enrichment of EZH2 at the Per1 promoter region in LncCplx2 KO islets compared to WT (n = 3). IB analysis of EZH2 antibody immunoprecipitation efficiency, IgG as negative control. All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, using two-tailed Student's t-test.

3.6. LncCplx2 KO mice exhibit overt diabetic phenotypes

We went on to explore the physiological phenotypes of LncCplx2 KO mice. The body weight of LncCplx2 KO mice was reduced at 4 weeks old, compared with the WT mice (Figure 6A). However, no obvious phenotype with respect to body weight was observed from 6 weeks to study end (Figure 6A). Strikingly, the random blood glucose is increased from 4 weeks to study end in the LncCplx2 KO mice (Figure 6B), suggesting that the LncCplx2 deficiency disrupts glucose homeostasis. Consistently, LncCplx2 KO mice exhibited high fasted blood glucose and insulin level, as well as normal fasted blood proinsulin level, compared to WT mice (Figure 6C–E). Moreover, GTT result showed that LncCplx2 deficiency significantly impaired glucose tolerance in mice (Figure 6F). Taken together, these results suggest that LncCplx2 deficiency results in overt diabetic phenotypes.

Figure 6.

LncCplx2-deficient mice exhibit overt diabetic phenotypes. (A–B) Body weight (A) and random blood glucose (B) of WT and LncCplx2 KO mice were measured from 4 weeks to 30 weeks (n = 8, male). (C–E) Fasted blood glucose (C), fasted proinsulin (D) and fasted insulin (E) of WT and LncCplx2 KO mice was determined at 12 weeks (n = 5/6, male). (F) Blood glucose during glucose tolerance test (GTT) in WT and LncCplx2 KO mice at 12 weeks (n = 12/10, male). All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, using two-tailed Student's t-test and two-way ANOVA.

3.7. LncCplx2 KO mice disrupt circadian behaviors

Previous study showed that LncCplx2 is a circadian rhythmic transcript in penal gland [21], which prompted us to examine whether LncCplx2 deficiency could affect the circadian behaviors. Mice were placed in metabolic cages equipped with infrared sensors to detect locomotor activity under entrained 12-h of light and 12-h of dark cycle (LD). LncCplx2 KO mice showed a slightly but significantly increased duration of the circadian period under entrained LD conditions (Figure 7A and B). Strikingly, the magnitude of locomotor activity was significantly decreased in the LncCplx2 KO mice under entrained LD conditions (Figure 7C and D). Accordingly, the metabolic phenotypes showed that the LncCplx2 KO mice exhibited less O2 consumption, less CO2 production and less energy expenditure, but normal respiratory exchange rate (RER), compared to WT mice (Figure 7E–H), consistent with the features of aging [29]. However, no obvious change in feeding behavior was observed between the WT and LncCplx2 KO mice (Figure S6). Next, we examined the effects of LncCplx2 deficiency on the synchronization of circadian rhythms using an experimental jet-lag model, in which mice were entrained in LD cycle for 10 days, then the LD cycles was delayed 6-h. The results showed that LncCplx2 KO mice showed significantly faster re-entrainment compared to WT mice (Figure S7a and b). Consistently, the activity onset and offset of LncCplx2 KO mice showed faster re-entrainment to the new LD cycle (Figure S7c and d). Taken together, these results show that LncCplx2 deficiency disrupts the circadian behavior.

Figure 7.

LncCplx2 deficiency disrupts circadian behaviors. (A) Representative actogram of locomotor activity in WT and LncCplx2 KO mice under an entrained LD cycle. (B) Circadian free running period in WT and LncCplx2 KO mice under an entrained LD cycle (n = 12, 12 weeks, male). (C–D) Quantification of locomotor activities in the X-axis (C) and Y-axis (D) during the day or night time of WT and LncCplx2 KO mice (n = 12, 12 weeks, male). (E–H), Average value of VO2 (E), VCO2 (F), HEAT (G) and RER (H) in WT and LncCplx2 KO mice (n = 12, 12 weeks, male). All the data are shown as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, using two-tailed Student's t-test and two-way ANOVA.

4. Discussion

Overall, this study unveils an islets-enriched rhythmic long non-coding RNA LncCplx2 plays a role in regulating glucose homeostasis and pancreatic β cell function by modulating circadian gene expression. The findings suggest that LncCplx2 functions as an unexpected transcriptional regulator within the circadian system and provide insights into a more integrated mechanism for coordinating circadian rhythms and glucose homeostasis.

Numerous studies demonstrated that the circadian transcriptional loop is critical for maintenance of the glucose homeostasis [6,33]. Differential metabolic phenotypes were observed in various core clock gene mutant mice [33]. Both Bmal1 KO or Clock mutant mice showed fasting hyperglycemia, impaired glucose tolerance and blunted insulin sensitivity [9]. Glucose homeostasis is also disrupted in the Cry-deficient or Per-deficient mice [14,15]. An overview of the metabolic disturbances reported for the different global clock gene KOs is well reviewed en masse [33]. In addition, it has been reported that the tissues-specific KO Bmal1 or Clock is sufficient to disrupt the glucose homeostasis [9,10]. For example, the pancreas-specific and β cell-specific Clock or Bmal1 KO mice exhibit diabetic phenotypes and disrupt the pancreatic β-cell function [10]. In this study, we found that LncCplx2 deficiency exhibit the diabetic phenotypes, including hyperglycemia, impaired glucose tolerance, and defective in the pancreatic islets size and impaired GSIS function, consistent with the phenotypes of β-cell specific Clock or Bmal1 KO mice. Furthermore, the molecular mechanism underlying BMAL1/CLOCK complexes circadian control of glucose homeostasis has been demonstrated to be through the regulation of time-dependent transcription of key β cell exocytosis, proliferation and metabolic genes [10]. Consistently, LncCplx2 deficiency leads to the phase shifts and amplitude changes of clock-dependent transcriptional waves of insulin signaling and cell cycle genes, indicating that the molecular mechanism underlying LncCplx2 affect the pancreatic islet function is through the regulation of circadian gene expression. This study has shed new light into the fascinating connection between circadian rhythm and metabolism.

Author contributions

T.X. and Z.L. conceived the project. L.W., T.X. and Z.L. prepared the manuscript. L.W. and Z.L. contributed to the experiments design, data acquisition and analysis. L.W. carried out animal experiments. L.H. and X.W. performed bioinformatics analysis. Z.G. help with RNA-seq analysis. M.W. and J.H. performed the RNA in situ hybridization. Y.F. help review and edit the manuscript. All the authors discussed the data and reviewed the manuscript. Z.L. contributed to the study conceptualization, resources, investigation, review and editing of the manuscript, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, and is the guarantor and takes full responsibility for the work as a whole, including the study design, access to data, and the decision to submit and publish the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Institute of Biophysics Core Facilities, in particular, Zhenwei Yang for technical support with qRT-PCR and Zheng Liu for technical support with mouse feeding. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82200884 to Z.L. and 31730054 to T.X.), National Key Research and Development Program (2021YFA1300301 to T.X.) and Guangdong Province High-level Talent Youth Project (2021QN02Y939 to Z.L.).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2024.101878.

Contributor Information

Yuying Fan, Email: fanyy033@nenu.edu.cn.

Tao Xu, Email: xutao@ibp.ac.cn.

Zonghong Li, Email: li_zonghong@gzlab.ac.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Figure S1.

Identification of long non-coding RNA LncCplx2. (a) IGV view of LncCplx2 locus by analysis of full length RNA-seq and poly A+ 3′ end RNA-seq data from INS1 cells and rat islets. The red rectangle indicates the signal of 3′ end of LncCplx2. (b) 3′ end of LncCplx2 was determined by 3′ RACE assay. The arrow indicates the RACE PCR production subsequently confirmed by Sanger sequence. (c) IGV view of the LncCplx2 locus based on RNA-seq data from mouse islet, human islet and β cells. RNA-seq data for human islets and β cells were obtained from published paper [34]. (d) qRT-PCR analysis of LncCplx2 expression in serum-shocked Min6 cells. Two paired primers targeting LncCplx2 transcript were used. (e–f) In silico prediction of LncCplx2 coding potential using Coding Potential Alignment Tool (e) and Coding Potential Calculator 2 (f). Xist serves as a control non-coding gene, while Actin and Gapdh serve as control coding genes. (g) RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization following immunofluorescence staining of glucagon and insulin antibody showing that LncCplx2 co-localized with insulin in mouse pancreatic islets. Scale bar, 50 μm (n = 3 independent experiments).

Figure S2.

LncCplx2 is downregulated in high glucose treated pancreatic β cells. (a–c) Analysis of LncCplx2 expression by qRT-PCR in islets from Wistar and diabetic GK rats (a, n = 8), WT and diabetic ob/ob (b, n = 6), as well as WT and db/db mice (c, n = 6). (d) Analysis of LncCplx2 expression in the islets of healthy and type 2 diabetic (T2D) individuals from published database (GEO: GSE164416) (n = 18). (e) Analysis of LncCplx2 expression by qRT-PCR in INS1 cells treated with 11 mM and 28 mM glucose for 24 h (n = 4). (f–g) Analysis of LncCplx2 expression by qRT-PCR in Min6 cells treated with 2.8 mM, 11 mM and 28 mM glucose for 24 h (f, n = 5) and 48 h (g, n = 4). (h) Analysis of LncCplx2 expression by qRT-PCR in Bmal1 KO Min6 cells treated with 2.8 mM and 28 mM glucose for 48 h (n = 5). All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, using two-tailed Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA.

Figure S3.

Establishment of LncCplx2 KO mice. (a) Schematic diagram showing the endogenous mouse LncCplx2 locus and genome location of all sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 KO strategy and primers used for identification of LncCplx2 KO mice. (b) Agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of PCR products, in which PCR reaction using primers (1) with single band and PCR reaction using primers (2) without band are shown as homozygotes deficiency. (c) Analysis of LncCplx2 expression by qRT-PCR in islets from WT and LncCplx2 KO mice (n = 6). All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01, using two-tailed Student's t-test.

Figure S4.

Cplx2 KO does not affect GSIS function and gene expression in pancreatic β cell. (a–c) IB analysis of CPLX2 protein level in LncCplx2 KO islets (a), LncCplx2 KO Min6 cells with or without rescue expression of LncCplx2 (b), and Cplx2 KO Min6 cells (c). β-actin was used as the loading control. (d) GSIS function of WT and Cplx2 KO Min6 cells. (e) Analysis of DEGs by qRT-PCR in Cplx2 KO Min6 cells. All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, using two-tailed Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA.

Figure S5.

LncCplx2 deficiency disrupts rhythmic expression of insulin signaling (a), glucose metabolism (b), β cell growth (c) and cell cycle (d) genes. All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, using two-tailed Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA.

Figure S6.

LncCplx2 deficiency does not affect the feeding behavior. (a–c) Representative actogram of feeding activity in WT and LncCplx2 KO mice under an entrained LD condition (a), quantification of locomotor activities in the Z-axis during the day or night time of WT and LncCplx2 KO mice (b) and measurement of food intake (c) under an entrained LD (n = 12, 12 weeks, male). All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM. using two-tailed Student's t-test and two-way ANOVA.

Figure S7.

LncCplx2 deficiency results in rapid re-entrainment of circadian rhythms to time delay shifts. (a) Representative actogram of locomotor activity in WT and LncCplx2 KO mice under an entrained LD cycle and a delayed 6-h LD cycle. (b) Quantification of the re-entrainment days of WT and LncCplx2 KO mice to the delayed 6-h LD cycle. (c–d) Quantification of activity onset (c) and offset (d) of WT and LncCplx2 KO mice during re-entrainment to the delayed 6-h LD cycle (n = 6, 12 weeks, male). All the data are shown as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05. Statistically significant differences assessed using two-tailed Student's t-test and two-way ANOVA.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Hastings M.H., Reddy A.B., Maywood E.S. A clockwork web: circadian timing in brain and periphery, in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:649–661. doi: 10.1038/nrn1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi J.S. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18:164–179. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shearman L.P., Sriram S., Weaver D.R., Maywood E.S., Chaves I., Zheng B., et al. Interacting molecular loops in the mammalian circadian clock. Science. 2000;288:1013–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preitner N., Damiola F., Lopez-Molina L., Zakany J., Duboule D., Albrecht U., et al. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002;110:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsui S., Yamaguchi S., Matsuo T., Ishida Y., Okamura H. Antagonistic role of E4BP4 and PAR proteins in the circadian oscillatory mechanism. Genes Dev. 2001;15:995–1006. doi: 10.1101/gad.873501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vieira E., Burris T.P., Quesada I. Clock genes, pancreatic function, and diabetes. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:685–693. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J., Liu R., de Jesus D., Kim B.S., Ma K., Moulik M., et al. Circadian control of beta-cell function and stress responses. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(Suppl 1):123–133. doi: 10.1111/dom.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudic R.D., McNamara P., Curtis A.M., Boston R.C., Panda S., Hogenesch J.B., et al. BMAL1 and CLOCK, two essential components of the circadian clock, are involved in glucose homeostasis. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcheva B., Ramsey K.M., Buhr E.D., Kobayashi Y., Su H., Ko C.H., et al. Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes. Nature. 2010;466:627–631. doi: 10.1038/nature09253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perelis M., Marcheva B., Ramsey K.M., Schipma M.J., Hutchison A.L., Taguchi A., et al. Pancreatic beta cell enhancers regulate rhythmic transcription of genes controlling insulin secretion. Science. 2015;350:aac4250. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadacca L.A., Lamia K.A., deLemos A.S., Blum B., Weitz C.J. An intrinsic circadian clock of the pancreas is required for normal insulin release and glucose homeostasis in mice. Diabetologia. 2011;54:120–124. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1920-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vieira E., Marroqui L., Batista T.M., Caballero-Garrido E., Carneiro E.M., Boschero A.C., et al. The clock gene Rev-erbalpha regulates pancreatic beta-cell function: modulation by leptin and high-fat diet. Endocrinology. 2012;153:592–601. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcheva B., Ramsey K.M., Bass J. Circadian genes and insulin exocytosis. Cell Logist. 2011;1:32–36. doi: 10.4161/cl.1.1.14426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y., Zhang Y., Zhou M., Wang S., Hua Z., Zhang J. Loss of mPer2 increases plasma insulin levels by enhanced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and impaired insulin clearance in mice. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1306–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barclay J.L., Shostak A., Leliavski A., Tsang A.H., Johren O., Muller-Fielitz H., et al. High-fat diet-induced hyperinsulinemia and tissue-specific insulin resistance in Cry-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E1053–E1063. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00512.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yao R.W., Wang Y., Chen L.L. Cellular functions of long noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:542–551. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patraquim P., Magny E.G., Pueyo J.I., Platero A.I., Couso J.P. Translation and natural selection of micropeptides from long non-canonical RNAs. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6515. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34094-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan Z., Zhao M., Joshi P.D., Li P., Zhang Y., Guo W., et al. A class of circadian long non-coding RNAs mark enhancers modulating long-range circadian gene regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:5720–5738. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vollmers C., Schmitz R.J., Nathanson J., Yeo G., Ecker J.R., Panda S. Circadian oscillations of protein-coding and regulatory RNAs in a highly dynamic mammalian liver epigenome. Cell Metab. 2012;16:833–845. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou J., Li Z., Zhong W., Hao Q., Lei L., Wang L., et al. Temporal transcriptomic and proteomic landscapes of deteriorating pancreatic islets in type 2 diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2017;66:2188–2200. doi: 10.2337/db16-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coon S.L., Munson P.J., Cherukuri P.F., Sugden D., Rath M.F., Moller M., et al. Circadian changes in long noncoding RNAs in the pineal gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13319–13324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207748109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sokolove P.G., Bushell W.N. The chi square periodogram: its utility for analysis of circadian rhythms. J Theor Biol. 1978;72:131–160. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(78)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Refinetti R., Lissen G.C., Halberg F. Procedures for numerical analysis of circadian rhythms. Biol Rhythm Res. 2007;38:275–325. doi: 10.1080/09291010600903692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughey J., Tackenberg M. ectr: Calculate the Periodogram of a Time-Course. Version 1.0.1. 2022 Available from: https://github.com/hugheylab/spectr. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jagannath A., Butler R., Godinho S.I.H., Couch Y., Brown L.A., Vasudevan S.R., et al. The CRTC1-SIK1 pathway regulates entrainment of the circadian clock. Cell. 2013;154:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Numano R., Yamazaki S., Umeda N., Samura T., Sujino M., Takahashi R., et al. Constitutive expression of the Period1 gene impairs behavioral and molecular circadian rhythms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3716–3721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600060103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Annayev Y., Adar S., Chiou Y.Y., Lieb J.D., Sancar A., Ye R. Gene model 129 (Gm129) encodes a novel transcriptional repressor that modulates circadian gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:5013–5024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.534651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris M.E., Viswanathan N., Kuhlman S., Davis F.C., Weitz C.J. A screen for genes induced in the suprachiasmatic nucleus by light. Science. 1998;279:1544–1547. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juste Y.R., Kaushik S., Bourdenx M., Aflakpui R., Bandyopadhyay S., Garcia F., et al. Reciprocal regulation of chaperone-mediated autophagy and the circadian clock. Nat Cell Biol. 2021;23:1255–1270. doi: 10.1038/s41556-021-00800-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarraberes F.A., Dice J.F. A molecular chaperone complex at the lysosomal membrane is required for protein translocation. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2491–2499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.13.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long Y., Hwang T., Gooding A.R., Goodrich K.J., Rinn J.L., Cech T.R. RNA is essential for PRC2 chromatin occupancy and function in human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet. 2020;52:931–938. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Etchegaray J.P., Yang X., DeBruyne J.P., Peters A., Weaver D.R., Jenuwein T., et al. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is required for mammalian circadian clock function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21209–21215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalsbeek A., la Fleur S., Fliers E. Circadian control of glucose metabolism. Mol Metab. 2014;3:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moran I., Akerman I., van de Bunt M., Xie R., Benazra M., Nammo T., et al. Human beta cell transcriptome analysis uncovers lncRNAs that are tissue-specific, dynamically regulated, and abnormally expressed in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2012;16:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.