Abstract

A 9-year-old male neutered Devon Rex cat was presented for continued investigations following a 7-year history of recurrent syncope. Previous diagnostic tests, including 24 h (Holter) electrocardiographic monitoring, had failed to identify the aetiology of such episodes, and former empirical treatment with atenolol had not provided satisfactory control of the clinical signs. A conclusive diagnosis was eventually achieved using an implantable loop recorder (Reveal), which identified paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) associated with a syncopal episode. Treatment with oral sotalol was instituted and, 18 months after initiation of anti-arrhythmic therapy, no further syncopal episodes have been observed by the cat's owners.

A 9-year-old male neutered, 4.5 kg, Devon Rex cat was presented to the Veterinary Medical Center of the University of Minnesota, with a long history of syncope. The cat had been in the owners' possession since he was a kitten. He was living exclusively indoors, was regularly vaccinated and wormed and was fed a commercial maintenance cat food.

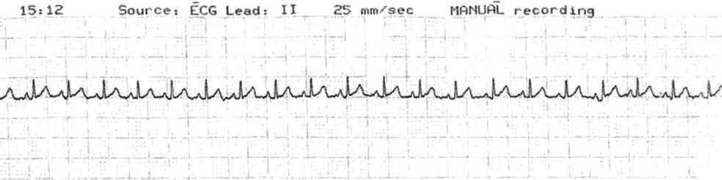

The first episode of syncope was observed when the cat was only 18-month-old, when the owners reported two collapsing episodes, 3 weeks apart. On both occasions, the cat was found recumbent on the floor, immobile and unconscious. The clinical onset was sudden, unexpected, and unprovoked. The cat was reported to regain consciousness spontaneously after a few seconds, but appeared lethargic, cold and dyspnoeic during recovery, returning to a normal condition after approximately 30–60 min. Upon physical examination, the cat did not show any significant abnormalities. Neurological examination was unremarkable. Results of a complete blood count, serum chemistry, serum total thyroxine (T4), and urinalysis were all within the normal ranges. The cat was also negative for the presence of antibodies to feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and for feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) antigen. Electrocardiography (ECG) showed sinus rhythm of approximately 180 bpm (Fig 1). Thoracic radiographs and full echocardiography were essentially unremarkable. A presumptive diagnosis of paroxysmal tachycardia was made and empirical treatment with atenolol (Atenolol, Sandoz Geneva Generics Princeton, NJ, USA) (6.25 mg, PO once daily) was instituted.

Fig 1.

Resting ECG (lead II, 10 mm/mV, 25 mm/s) recorded as a part of the initial diagnostic investigation for recurrent syncope. The trace shows a normal sinus rhythm with a heart rate of approximately 170 bpm. There is no clear evidence of ventricular pre-excitation (short PR intervals) that would suggest the presence of an accessory conduction pathway.

Four months later, after another syncopal episode, the administration of atenolol was increased to 6.25 mg, PO, twice daily. The increased daily dose of atenolol seemed to prolong the interval between episodes; however, the owner continued to report collapsing episodes occurring at approximately 3–4 months intervals. ECG recordings, thoracic radiographs and echocardiograms performed over the forthcoming years were inconclusive. Furthermore, a 24 h (Holter) ECG recorded after a syncopal episode when the cat was 7-year-old failed to demonstrate the presence of any abnormalities. The recorded trace revealed a predominant sinus rhythm, with an average heart rate of 150 bpm (range 100–214). Given the fractious nature of the patient, it was decided to consider further diagnostic investigations only in case of significant shortening of the interval between events or increased severity of the syncopal episodes.

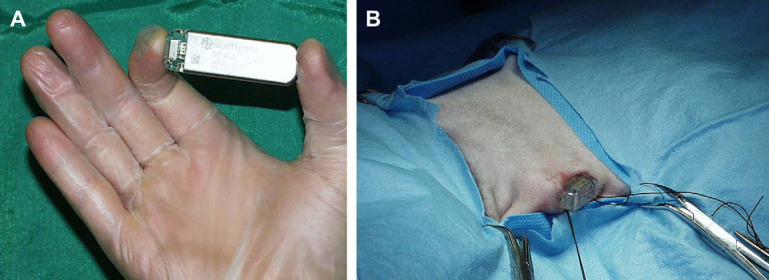

On representation at 9 years of age, the owner reported that three collapsing episodes had been observed in the previous 2 months. Physical examination, thoracic radiographs, ECG recording, echocardiography, complete blood count, serum chemistry, T4, and urianalysis were unremarkable. An implantable loop recorder (ILR) (Reveal Plus 9526, Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, USA) was inserted in the patient, under general anaesthesia, in a subcutaneous pocket created in the ventral aspect of the fifth intercostal space on the left side of the thorax, following the method described by Willis et al 1 (Fig 2A and B). The procedure was successful and recovery from anaesthesia was rapid and uneventful. The proper functioning of the device was assessed using a pacemaker programmer (9790C, Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, USA) and a baseline trace was recorded, showing sinus rhythm at 180 bpm (Fig 3A). The device was programmed to automatically detect five episodes of abnormal ECG recording (classified as asystole>4.5 s, bradycardia<40 bpm, or tachycardia>230 bpm for at least 32 consecutive beats) and three recordings to be manually activated by the owner with the dedicated remote activator.

Fig 2.

(A) The ILR (Reveal Plus 9526) and (B) final phase of the surgical implantation in a subcutaneous pocket created at the level of the cranio-ventral region of the left side of the thorax.

Fig 3.

(A) ECG strip obtained from the interrogation of the ILR after surgical implant in the patient. The trace shows a normal sinus rhythm with heart rate of approximately 180 bpm. (B and C) Two samples of ECG trace recorded by the ILR during a syncopal episode. The arrowhead indicates the manual activation operated by the owner during the episode. The traces show SVT with a heart rate of approximately 420 bpm. The presence of QRS alternans would suggest retrograde conduction.

The cat was discharged on the same day and the owners were instructed on how to use the activator during, or immediately after, a syncopal episode. Four weeks later, the cat was presented to the emergency room at night, after another episode of syncope. Thoracic radiographs were unremarkable and ECG recording showed sinus rhythm at 180 bpm. The following morning, interrogation of the loop recorder showed that all the parameters previously programmed were deleted, suggesting an electrical reset of the device. Therefore, the recorder was reprogrammed and the patient discharged. Two weeks later, the interrogation of the implanted device revealed episodes of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with a heart rate of 400–430 bpm, which coincided with three manual activations of the recorder performed by the owner during, and immediately after, another syncopal episode (Fig 3B and C). The QRS alternans observed in the trace were suggestive of a retrograde conduction. 2

Given the lack of satisfactory clinical response to atenolol, the medication was discontinued progressively over a period of 2 weeks, followed by the institution of a new anti-arrhythmic treatment with sotalol (Apo-Sotalol, Apotex Inc, Weston, Ontario, Canada) (10 mg, PO twice daily).

The cat did not show any further episodes of syncope following institution of medical therapy with sotalol and, 18 months later, he remains symptom-free. Although the battery of the device expired 10 months after implantation, it was decided to leave the recorder in situ, to avoid unnecessary stress for the patient.

In the veterinary literature, the reported cases of syncope in cats have been associated with prolonged periods of sinus arrest, 3 right outflow obstruction secondary to heartworm disease, 4 increases in intra-thoracic and intra-abdominal pressure with subsequent reduced venous return during defecation, 5 paroxysmal atrio-ventricular (AV) block with ventricular standstill, 6 ventricular tachycardia 7 or arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. 8

To the best of the author's knowledge, syncope associated with paroxysmal SVT has not been previously reported in the cat. An episode of ‘tetanic seizure’ possibly associated with paroxysmal atrial tachycardia has been described in a Persian cat; however, a confirmative association between syncope and tachycardia was not observed. 9 In a domestic shorthair cat, 3 described syncopal episodes documented on 24 h (Holter) ECG. These episodes coincided with prolonged periods of sinus arrest precipitated by a preceding period of sinus tachycardia and occasional supraventricular premature complexes.

Syncope is not a clinical sign commonly associated with SVT in people. 10 Nevertheless, it is realistic to believe that such a high heart rate recorded during the syncopal episode in this cat would have severely compromised the cardiac output, with subsequent reduction in cerebral perfusion resulting in loss of consciousness. 11

The investigation of paroxysmal arrhythmias is complex and a definitive diagnosis requires a diagnostic ECG recording obtained during symptomatic episodes (ie, syncope). Given the often sporadic and unpredictable nature of such episodes, standard ECG recording is frequently non-diagnostic. Similarly, episodic arrhythmias that do not occur on a daily basis may be missed by a 24 h (Holter) ECG monitoring, as demonstrated in this case. For these reasons, cardiac event recorders may have a much higher diagnostic rate both in dogs and cats. 7 However, even ambulatory event recorders present some pitfalls. For example, lead detachment may represent an important limitation, especially after a few days of monitoring. Moreover, cats may become uncooperative and attempt to remove the recorder. Finally, the interval between clinical episodes may be significantly longer than the time the event recorder is worn by the patient (usually less than 1–2 weeks).

In humans affected by recurrent syncope, the use of ILRs has significantly increased the diagnostic rate and allowed more rapid introduction of therapy. 12 In veterinary medicine, the only previous report on the use of an ILR was described by Willis et al 1 to investigate a case of recurrent syncope in a cat. Unfortunately, despite the successful implantation and correct functionality of the device, the association between syncope and significant arrhythmia in that cat remained unsolved because of the sudden death of the patient. However, in this case, the definitive diagnosis achieved by using an ILR should encourage the use of this device for the initial investigation of recurrent syncope in small animals. Furthermore, it may be possible that, in this case, a diagnosis could have been achieved significantly earlier if an ILR was readily available at the time of first referral.

The cause of electrical reset of the ILR following the first syncopal episode after implantation remains unknown. According to the safety information provided by the manufacturer, an electrical reset of the device can be caused by magnetic resonance imaging, sources of radiation, electrosurgical cautery, external defibrillation, lithotripsy, and radiofrequency ablation. Therefore, by exclusion of all other causes, it was assumed that the radiographic imaging obtained immediately after admission to the emergency room might have caused the incidental loss of data.

Although cardiac mapping and radiofrequency ablation currently represents the treatment of choice for many types of SVT in people, the procedure could not be considered in this case due to the small size of the patient. Therefore, given the lack of a satisfactory clinical response to atenolol over the preceding years, it was decided to initiate anti-arrhythmic treatment with sotalol. Sotalol belongs to class III anti-arrhythmic drugs, although its L-isomer exhibits non-selective β-blocking effects (class II). In human cardiology, sotalol has been demonstrated to be effective in preventing many forms of SVT, including nodal re-entry, AV re-entry, and atrial tachycardias, atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. 13 In this cat, side-effects relatable to the chronic administration of sotalol were not observed by the owners. Furthermore, the clinical efficacy of the new anti-arrhythmic treatment was considered satisfactory as further syncopal episodes were no longer observed after administration of sotalol.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, USA, for the donation of the implantable loop recorder and their kind support. A special thank you to Heidi Cooper for reviewing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Willis R., McLeod K., Cusack J., Wotton P. Use of an implantable loop recorder to investigate syncope in a cat, J Small Anim Pract 44, 2003, 181–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brembilla-Perrot B., Lucron H., Schwalm F., Haouzi A. Mechanism of QRS electrical alternans, Heart 77, 1997, 180–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meurs K.M., Miller M.W., Mackie J.R., Mathison P. Syncope associated with cardiac lymphoma in a cat, J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 30, 1994, 583–585. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik R., Church D.B., Eade I.G. Syncope in a cat, Aust Vet J 7, 1998, 465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitley N.T., Stepien R.L. Defecation syncope and pulmonary thromboembolism in a cat, Aust Vet J 6, 2001, 403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferasin L., van de Stadt M., Rudorf H., Langford K., Moore A. Hotston. Syncope associated with paroxysmal atrioventricular block and ventricular standstill in a cat, J Small Anim Pract 43, 2002, 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bright J.M., Cali J.V. Clinical usefulness of cardiac event recording in dogs and cats examined because of syncope, episodic collapse, or intermittent weakness: 60 cases (1997–1999), J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 216, 2000, 1110–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey A.M., Battersby I.A., Faena M., Fews D., Darke P.G.G., Ferasin L. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in two cats, J Small Anim Pract 46, 2005, 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harwood M.L. Paroxysmal atrial tachycardia and left superior bundle branch blockage in a cat, Vet Med Small Anim Clin 65, 1970, 862–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delacrétaz E. Supraventricular tachycardia, N Engl J Med 354, 2006, 1039–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobari M., Fukuuchi Y., Tomita M., Tanahashi N., Shinohara T., Yamawaki T., Ohta K., Takeda H. Cerebral microcirculatory changes during and following transient ventricular tachycardia in cats, J Neurolog Sci 111, 1992, 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farwell D.J., Freemantle N., Sulke N. The clinical impact of implantable loop recorders in patients with syncope, Eur Heart J 27, 2006, 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan M.H. Oral class III antiarrhythmics: What is new?, Curr Opin Cardiol 19, 2004, 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]