Abstract

In recent years, there has been an increase in interest in applied ethology and animal welfare, and an increase in the popularity of the domestic cat. This has stimulated research on the behaviour and welfare of cats kept in different environments. This article presents a review of the recent research and makes recommendations for the housing of domestic cats in the home, in catteries and animal shelters, in laboratories and in veterinary surgeries.

The popularity of the domestic cat has increased steadily in the past few years. In 1998, the owned cat population in the UK was 8 million and exceeded the pet dog population by 1.1 million (Pet Food Manufacturers' Association 1999). Over 20% (5.1 million) of British households owned at least one cat and 37% of these households had more than one cat.

In recent years, research has been carried out on the behaviour and welfare of cats kept in different environments. These include laboratories (Podberscek et al 1991, McCune 1992, van den Bos & de Cock Buning 1994b, van den Bos 1998), animal shelters (Durman 1991, McCune 1992, Roy 1992, Smith et al 1994, Kessler & Turner 1997, Rochlitz 1997), quarantine and boarding catteries (Kessler & Turner 1997, Rochlitz et al 1998b) and the home (Bernstein & Strack 1996). This paper reviews the recent research, and presents guidelines on the housing requirements of cats kept in the home, in catteries and animal shelters, in laboratories and in veterinary surgeries.

Assessment of welfare

The domestic cat has evolved from a carnivore with an essentially solitary lifestyle where, in many contexts, there is no need for large, exaggerated or ritualised signals to develop. Assessment of welfare may initially seem difficult, as cats do not have as wide a behavioural repertoire for visual communication (eg posture, facial expression, tail position) as, for example, the highly social, group-living dog. However, the UK Cat Behaviour Working Group (1995) has published an ethogram (a catalogue of discrete, species-typical behaviour patterns that form the basic behavioural repertoire of the species) for behavioural studies of the domestic cat, and stress scores based on behaviour have been developed (McCune 1992, Kessler & Turner 1997). Physiological measures such as urinary Cortisol have also been used to assess welfare (Carlstead et al 1992, Carlstead et al 1993, Rochlitz et al 1998b).

Cats are more likely to respond to poor environmental conditions by becoming inactive and by inhibiting normal behaviours such as self-maintenance (feeding, grooming and elimination), exploration or play, than by actively showing abnormal behaviour (McCune 1992, Rochlitz 1997). Cats with illness may also modify their behaviour in a similar way. Keeping cats in an enriched, stimulating environment that encourages a wide range of normal behaviours will not only enhance their welfare, but also make it easier for owners and caretakers to detect illness.

General recommendations

The main points to be considered when designing or evaluating housing for cats are listed below. The particular requirements of cats kept in specific environments (the home, catteries and animal shelters, laboratories and veterinary surgeries) are considered in the next section. When cats are housed together the control of infectious disease is of primary importance, but this aspect will not be included in this review.

Size of enclosure 1

Within an enclosure (the internal environment), there should be adequate separation between feeding, resting and elimination (litter tray) areas. The enclosure should be large enough to allow cats to express a range of normal behaviours, and to permit the caretaker or owner to carry out cleaning procedures easily.

When cats are housed in groups, there should also be enough space for cats to keep themselves separate from others (Fig 1). Conflict-regulating mechanisms are important to maintain stability of groups in some species (van den Bos 1998), but group-living cats lack distinct dominance hierarchies and post-conflict mechanisms such as reconciliation (van den Bos & de Cock Buning 1994a, van den Bos 1998). They are not adapted to living in close proximity to each other and reduce the likelihood of aggression by establishing distances between themselves (Leyhausen 1979). If an enclosure is too small, there may be an increase in agonistic encounters or cats will attempt to avoid each other by decreasing their activity (Leyhausen 1979, van den Bos & de Cock Buning 1994a).

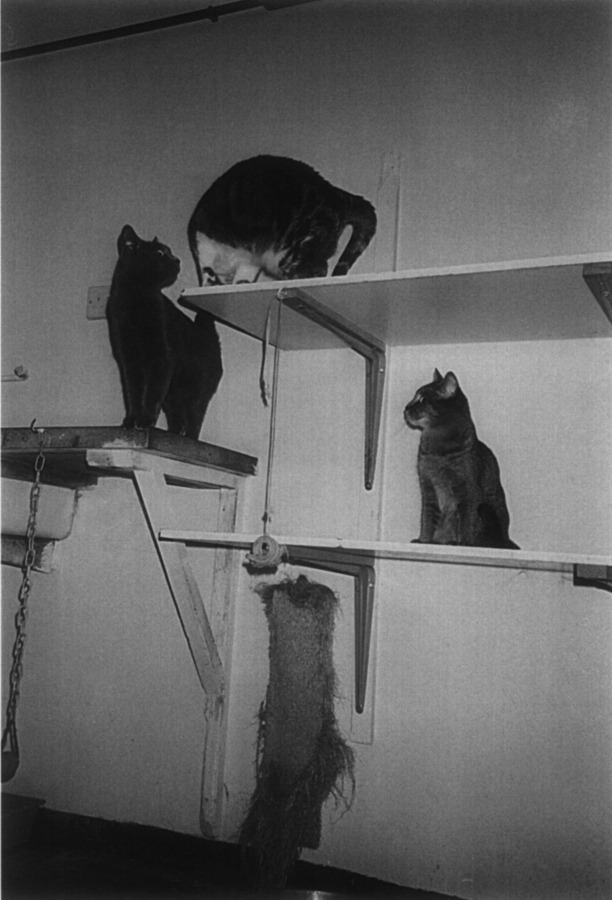

Fig 1.

Enclosures should be large enough to enable cats to keep away from other cats.

The vertical dimension is particularly important as regards the provision of appropriate internal complexity (see next section), so cages should be of adequate height.

Complexity of enclosure

Beyond a certain minimum size, it is the quality rather than the quantity of space that is important. Most cats are active, have the ability to climb well and are well-adapted for concealment (Eisenberg 1989). They use elevated areas as vantage points from which to monitor their surroundings (DeLuca & Kranda 1992, Holmes 1993, James 1995). Enclosures should contain structures that make maximal use of the vertical dimension, such as shelves, climbing frames, platforms, hammocks and raised walkways placed at various heights (Fig 2).

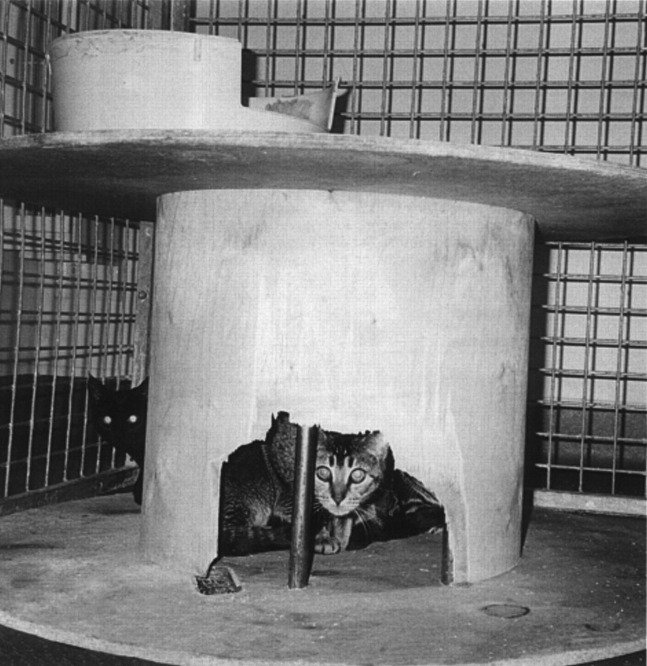

Fig 2.

Shelves at different heights should be provided, as well as a scratch post and toys.

As cats are more likely to rest alone than with others, there should be a sufficient number of resting areas for all cats in the enclosure. (Podberscek et al 1991, Bernstein & Strack 1996). Hiding is a behaviour that cats often show in response to stimuli or changes in their environment, and to avoid interactions with other cats or people (McCune 1992, Carlstead et al 1993, James 1995, Rochlitz et al 1998b). Resting areas where cats can retreat to and be concealed, in addition to ‘open’ resting areas (eg shelves), are essential for their well-being (Fig 3). Visual barriers, such as vertical panels, can also be used to enable cats to get away from others and hide. If it is necessary to observe the cat closely, a box open on two or three sides, or a deep-sided tray, can be used.

Fig 3.

Cats should have retreat areas where they can hide.

Rest areas should have comfortable bedding, which will reduce the likelihood of cats resting in their litter trays (DeLuca & Kranda 1992). Tests indicate that cats prefer polyester fleece to cotton-looped towel, woven rush-matting and corrugated cardboard for lying on (Hawthorne et al 1995).

There should be a sufficient number of litter trays, at least one per two cats (Hoskins 1996), sited away from feeding and resting areas. Cats can have individual preferences for litter characteristics, so it may be necessary to provide a range of litter types and designs of litter trays. Surfaces for claw abrasion (e.g. scratch posts, rush matting, carpet, wood) should also be avail able, as well as toys (Fig 2). Objects which move, have complex textures and mimic prey characteristics are the most successful at promoting play (Hall & Bradshaw 1998). A variety of toys should be available, and novelty is also important so toys should be replaced regularly. Most cats play alone rather than in groups (Podberscek et al 1991), so the cage should be large enough to permit them to play without disturbing other cats. Consideration should also be given to providing containers of grass, which some cats like to chew and may be important for the elimination of furballs (trichobezoars). Catnip (Nepeta cataria) may also be provided, either as a dried herb or contained in toys.

Another environmental enrichment technique is to increase the time animals spend in predatory and feeding behaviour. McCune (1995) suggests putting dry food into containers with holes through which the cat has to extract individual pieces.

Quality of the external environment

The environment around the enclosure (the external environment) will have an impact on the cat's welfare. Efforts should be made to increase olfactory, visual and auditory stimulation, for example by creating enclosures that look out on to areas of human and animal activity, or by providing access to an outdoor run. A technique used in some animal houses is the playing of a radio, to provide music and human conversation (Benn 1995, James 1995, Newberry 1995). This is thought to prevent animals from being startled by sudden noises and habituate them to human voices, and to provide a degree of continuity in the environment (James 1995).

Contact with conspecifics

The cat is a social carnivore that regularly interacts with conspecifics (Leyhausen 1979, Voith & Borchelt 1986, Sandell 1989). Most cats can be housed in groups providing that they are well socialised to other cats, and that there is sufficient space, easy access to feeding and elimination areas and a sufficient number of concealed retreats and resting places. When cats are kept in large groups, it may be necessary to distribute feed, rest and elimination areas in a number of different sites, to prevent certain cats from monopolising one area and denying others access (van den Bos & de Cock Buning 1994b).

Many factors will determine the ideal group size, but it seems that 20 to 25 individuals is the maximal number for cats in laboratories (James 1995, Hubrecht & Turner 1998). In animal shelters, where infectious disease is a frequent problem and there is a regular turnover of cats, they should be kept in smaller groups. Cats that fail to adapt satisfactorily to group-living should be identified and housed singly.

Contact with humans and quality of care

In addition to interacting with conspecifics, domestic cats interact frequently and effectively with humans (Voith & Borchelt 1986, Turner 1995). While cleaning and feeding times provide some opportunities for interactions, a period of time which is not part of routine caretaking procedures should be set aside every day for cats to interact with caretakers or owners (Fig 4). Some cats may prefer to be petted and handled, while others may prefer to interact via a toy (Karsh & Turner 1988).

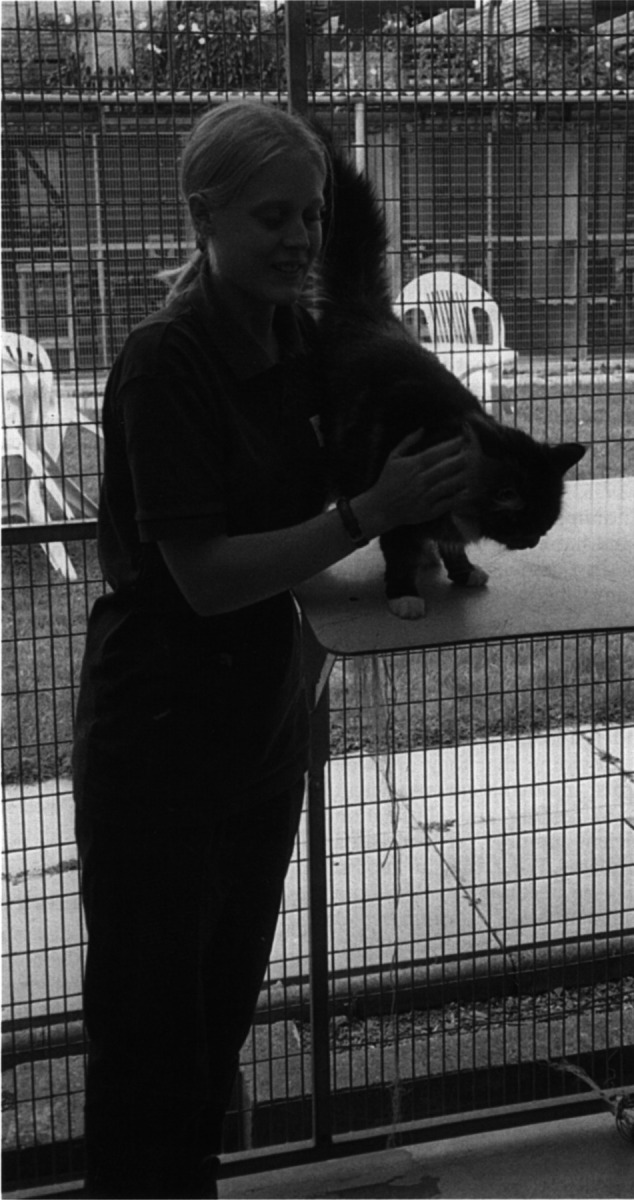

Fig 4.

Caretakers should interact on a regular basis with the cats under their care.

Owners and caretakers need to be knowledgeable about the behaviour of the animals they are responsible for, since behavioural changes are often the first indicators of illness or other causes of poor welfare. A study of owners who relinquished pets to shelters found that many lacked knowledge about the normal behaviour of their pets (Salman et al 1998). Owners are more likely to develop a successful relationship with their pet if they have realistic expectations about its behaviour and requirements (Kidd et al 1992). Formal training in animal husbandry should be mandatory for those involved in the day to day care of cats in shelters, catteries, laboratories and veterinary surgeries, and owners should be encouraged to obtain information about cats from a variety of sources.

The sociability of cats to people and to conspecifics is influenced by many factors, such as the handling of kittens at a young age, their exposure to other cats and people, and genetic influences (McCune et al 1995). Attention to management procedures and selective breeding will ensure that cats are well socialised.

Specific housing environments

The following section describes the particular requirements of cats in the home, in catteries and animal shelters, in laboratories and in veterinary surgeries. The aim should be to provide good housing conditions, regardless of the length of the housing period. Whether it will be housed for 2 days, 2 weeks, 2 months or 2 years is of no relevance to the animal; its well-being is determined by the conditions it lives in day to day.

Clearly, in some situations compromises or modifications may have to be made. For example, in quarantine catteries or animal shelters where cats may be confined for long periods, it will be particularly important to ensure that the enclosure and surroundings are complex and stimulating, and that the cats receive sufficient human contact. In veterinary surgeries (where the cat may be ill), or in laboratories (where experimental procedures are carried out), it may be necessary to restrict the cat's movement and to monitor it closely. Nevertheless, just because the animal will be housed for a short period of time is not an excuse for providing poor housing conditions.

The home

In the United States, between 50 and 60% of pet cats are housed indoors (Luke 1996, Patronek et al 1997); this figure is lower for cats in Britain although data have not been published. Some authors (Landsberg 1996, Miller 1996) feel that cats are best housed indoors, while others believe that the cat's quality of life is enhanced if it is allowed outdoors (O'Farrell & Neville 1994, Hubrecht & Turner 1998). Cats that roam freely outdoors are more likely to be exposed to infectious disease, involved in agonistic encounters with cats and other animals, injured or killed by motor vehicles, and may go missing. Another stated argument for keeping cats indoors is to protect wildlife populations from predation (Patronek 1998). Cats with outdoor access can probably compensate to some degree for unsatisfactory conditions in their home environment (Turner 1995). Some behaviourists note that cats kept exclusively indoors are over-represented in the population referred to them with behavioural problems (Hubrecht & Turner 1998). Providing secure enclosures within a garden, or leash-training a cat, are solutions that enable the cat to benefit from outdoor access without undue risk. Whether cats are confined indoors or allowed outdoors, housing conditions in the home should follow the recommendations listed previously.

Bernstein and Strack (1996) described the use of space and patterns of interaction of 14 unrelated, neutered domestic cats, who lived together in a single-storey house at a density of one cat per 10 m2. The cats did not have access to the outdoors. Most of the cats had favourite spots within the rooms that they used. Some individuals had their own unique place, but more commonly several cats chose the same favourite spot. These areas were shared either physically, by cats occupying the space together or, more often, temporally by cats occupying them at different times of the day. There was very little aggression and no fighting between the cats. Individuals seemed to peacefully co-exist by avoiding each other for most of the time. Female cats are said to be more suited to an indoor existence than male cats, because feral males have a bigger home range than feral females (Mertens & Schär 1988). Bernstein and Strack (1996) found that neutered males had an average home range of four to five rooms (out of 10), and neutered females a range of three to 3.6 rooms. It is likely that both neutered males and neutered females can be successfully housed indoors, providing there is sufficient quantity and quality of space.

Boarding and quarantine catteries and animal shelters

In 1995, the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health published model licence conditions and guidance for cat boarding establishments in the UK (CIEH Animal Boarding Establishments Working Party 1995). These guidelines serve as a basis upon which local environmental health officers issue licences to boarding catteries. Concerns have been expressed regarding the welfare of animals in quarantine (Bennett 1997, Rochlitz et al 1998a, b) but currently there exists only a voluntary code of practice (Ministry of Agriculture 1995). However, legislation on welfare standards in quarantine premises is likely to be introduced in the future. Animal shelters in the UK are not subject to legislation on standards of animal care, although the Feline Advisory Bureau has recently published a cat rescue manual (Haughie 1998), which includes a code of practice for cat rescue facilities.

Durman (1991) described behavioural indicators of stress in cats who were introduced into communal pens at an animal shelter. Major behavioural changes occurred in the first 4 days, but changes continued throughout the first month as the cats adapted. Kessler and Turner (1997) studied 140 cats entering a boarding cattery, and monitored their adaptation using a Cat-Stress-Score. Stress levels decreased during the observation period, with a pronounced reduction in the first 4 days, and two-thirds of cats adjusted satisfactorily within 2 weeks. In another shelter study (Rochlitz 1997), behavioural and physiological data indicated that cats showed signs of adaptation within 2 weeks. However, cats took longer (5 weeks) to adjust to conditions in a quarantine cattery (Rochlitz et al 1998b).

Smith et al (1994) examined the behaviour of cats in shelters, with specific reference to their spatial distribution. Cats used structures more often than the floor of the pens, and high structures, which provided vantage points, were used more frequently than low ones. These findings were confirmed in other studies (Durman 1991, Podberscek et al 1991, Roy 1992, Rochlitz et al 1998b). Roy (1992) found that cats preferred wood as a substrate to plastic, and also liked materials that maintain a constant temperature such as straw, hay, wood shavings and fabric. In an animal shelter, the presence of a toy within an enclosure may make the animal more attractive to prospective owners (Wells & Hepper 1992).

Techniques have been developed for identifying cats that are unfriendly towards other cats or people (Kessler 1997). Cats that are poorly socialised towards conspecifics should be housed singly, and cats that are poorly socialised towards people, such as feral cats, should not initially be subjected to a high demand for interaction with shelter staff and visitors (Kessler 1997). However, cats may become more socialised towards humans and subsequently make more rewarding pets, if they receive regular socialisation sessions. Hoskins (1995) examined the effect of human contact on the reactions of cats in a rescue shelter. Cats that had received additional handling sessions, where they interacted closely with a familiar person, could subsequently be held for longer by an unfamiliar person than cats who had not received additional handling sessions.

Concern has been expressed regarding the potentially harmful effects long periods of housing in a shelter may have on the animal's behaviour (Wells & Hepper 1992) and the likelihood that the animal will be able to integrate successfully into a home environment after adoption. In a study of cats adopted from a shelter, there was no correlation between the length of time the cat had been in the shelter (the longest time was 9.5 months) and the time it took to adapt to its new home (Rochlitz et al 1996). Another study found that being in a quarantine cattery for six months caused changes in the temperament and behaviour of cats, and in the relationship between cats and their owners (Rochlitz et al 1998a).

Laboratories

In the UK, the Home Office issues a Code of Practice for the housing and care of animals used in scientific procedures (Home Office 1989) and a Code of Practice for the housing and care of animals in designated breeding and supplying establishments (Home Office 1995), to establish minimum standards and provide guidelines on the housing and care of laboratory animals. In 1997 1446 scientific procedures were performed on cats in Great Britain (Home Office 1998).

A number of studies underline the importance of positive social interactions between laboratory technicians and the animals under their care. Randall et al (1990) found that laboratory cats organised their daily activity patterns around human caretaker activity, and responded strongly to humans in their environment. Cats in enriched conditions in a laboratory facility preferred human contact to toys (DeLuca & Kranda 1992), and cats showed signs of stress when they were subjected to an unpredictable caretaking routine and technicians stopped petting and talking to them (Carlstead et al 1993).

De Monte and Le Pape (1997) found that a tennis ball was a more effective enrichment tool than a wooden log, for laboratory cats caged singly. Environmentally enriched housing for cats kept at the Waltham Centre for Pet Nutrition, a large research establishment in the UK, has been described for cats housed singly (Loveridge et al 1995) and in groups (Loveridge 1994).

Keeping cats in an enriched, stimulating environment that encourages a wide range of normal behaviours will not only enhance their welfare, making them better subjects for scientific investigation (Poole 1997), but will also have a positive effect on the public perception of the treatment of animals in laboratories (Benn 1995).

Veterinary surgeries

In veterinary surgeries, it is preferable for cats to be housed in an area away from dog kennels, providing that the cats can be adequately supervised. If tiered caging is used, the upper cages should be filled before the lower ones, and cats should not be kept in tiered caging for long periods of time. If cats are hospitalised for more than 6–8 h, a litter tray should be provided. The cage should be large enough to contain this, as well as a resting and feeding area. The addition of a box will improve the cat's welfare by offering it a place to hide (Fig 5), and if the box is solid it can also function as a shelf.

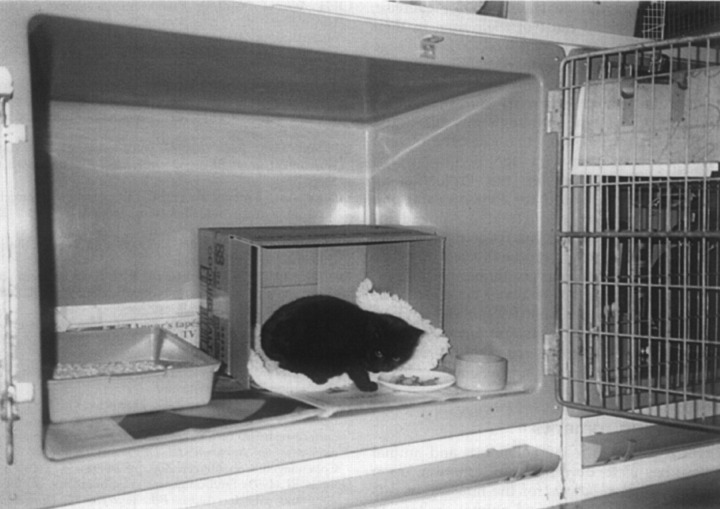

Fig 5.

The addition of a box will improve the cat's welfare when it is hospitalised in a veterinary surgery.

Current recommendations and regulations on dimensions of enclosures

Dimensions of enclosures for cats in animal shelters, boarding and quarantine catteries and laboratories are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cage sizes for cats in animal shelters, catteries and laboratories

| Code of Practice | Floor area (single) | Floor area (groups) | Height |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Animal shelter 1 | not specified | 1.67 m2/cat | walk-in (1.8 m) |

| Boarding cattery 2 | 2.55 m2 | 2 cats 3.73 m2 | walk-in (1.8 m) |

| 3–4 cats 4.68 m2 | |||

| Quarantine cattery 3 | up to 3 cats from same household in 1.4 m2 | walk-in (1.8 m) | |

| Cats (scientific procedures) 4 | <3 kg 0.5 m2 | <3 kg 0.33 m2/cat | <3 kg 0.5 m |

| >3 kg 0.75 m2 | >3 kg 0.5 m2/cat | >3 kg 0.8 m | |

| Cats (breeding & supplying) 5 | not specified | <3 kg 0.5 m2/cat | 2 m |

| >3 kg 0.75 m2/cat | |||

| Dogs (scientific procedures) 4 | <5 kg 4.5 m2 | <5 kg 1 m2/dog | <5 kg 1.5 m |

For group-living cats in shelters, Kessler (1997) suggests that 1.67 m2 of floor space is required per cat in order to keep stress at an acceptable level. The pen sizes recommended by the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health for boarding catteries, which include both the house and run area, are adequate. In the author's opinion, the minimum pen dimensions for cats in quarantine catteries cannot provide good housing, based on the recommendations described previously, and should be increased to dimensions similar to those required of boarding catteries.

Minimum cage sizes permitted for laboratory cats in the UK are also too small. The cage in Fig 5 has 0.42 m2 of floor space and is 0.5 m high, and is clearly inadequate for the long-term housing of an adult cat. Distinguishing between the dimensions of cages for cats according to body weight is unhelpful. Most adult cats weigh more than 3 kg. Those under 3 kg are likely to be kittens or young cats; they will be more active and playful than adults and will require more rather than less space. Groups often consist of cats of different weights, and a cat's weight may vary over time. Cage floor area should be determined per weaned cat, and not according to the weight of the cat.

In addition, it does not make sense that the floor area and height of cages permitted for cats are so much smaller than those for small dogs (less than 5 kg) kept for scientific procedures (Table 1). Some adult cats may weigh more than 5 kg, and dogs can be taken out for exercise, whereas cats spend most of their time in their cages. Shelving can be removed, a lower cage used or the cage height reduced using a horizontal partition if the experimental procedure requires that the cat's activity is restricted for short periods of time, although the cat should still be able to stretch fully in a vertical direction.

The working party for the review of the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes (ETS 123), Appendix A (Council of Europe 1986), has recommended that one to two weaned cats can be housed in a cage with a floor area of 1.5 m2, with another 0.75 m2 of floor space required for every additional cat; the cage should be walk-in (JWS Bradshaw, personal communication). These minimum cage dimensions are likely to be acceptable, providing that the quality of the space is also addressed.

Concluding remarks

Recent research in feline behaviour and animal welfare has yielded valuable information, upon which recommendations for the housing of cats in the home, in catteries and animal shelters, in laboratories and in veterinary surgeries can be based. There is a need for more research, and it is likely that the recommendations will be modified as further knowledge is gained.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the two anonymous referees for their helpful comments, and Professor D M Broom for providing the facilities to write this paper.

Footnotes

The terms enclosure, pen and cage are used interchangeably.

References

- Benn DM. (1995) Innovations in research animal care. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 206, 465–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RM. (1997) Non-market costs of rabies policy. The Veterinary Record 141, 127–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein PL, Strack M. (1996) A game of cat and house: Spatial patterns and behaviour of 14 cats (felis catus) in the home. Anthrozoos 9, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw JWS. (1992) The behaviour of the domestic cat. Wallingford, Oxon: CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- Carlstead K, Brown JL, Monfort SL, Killens R, Wildt DE. (1992) Urinary monitoring of adrenal responses to psychological stressors in domestic and nondomestic felids. Zoo Biology 11, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Carlstead K, Brown JL, Strawn W. (1993) Behavioural and physiological correlates of stress in laboratory cats. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 38, 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- CIEH Animal Boarding Establishments Working Party (1995) Model licence conditions and guidance for cat boarding establishments (Animal Boarding Establishments Act 1963). London: The Chartered Institute of Environmental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe (1986) European Convention for the protection of vertebrate animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes (ETS 123), Appendix A. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- De Monte M, Le Pape G. (1997) Behavioural effects of cage enrichment in single-caged adult cats. Animal Welfare 6, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca AM, Kranda KC. (1992) Environmental enrichment in a large animal facility. Laboratory Animal 21, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Durman KJ. (1991) Behavioural indicators of stress. BSc. thesis, University of Southampton. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg JF. (1989) An introduction to the Carnivora. In: Carnivore behaviour, ecology and evolution Gittelman JL, (ed.) London: Chapman & Hall, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hall SL, Bradshaw JWS. (1998) The influence of hunger on object play by adult domestic cats. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 58, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Haughie A. (1998) Cat Rescue Manual. Feline Advisory Bureau Publication. Tisbury, Wiltshire. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne AJ, Loveridge GG, Horrocks LJ. (1995) The behaviour of domestic cats in response to a variety of surface-textures. In: Proceedings of the second international conference on environmental enrichment, Holst B, (ed.) Copenhagen: Copenhagen Zoo, pp. 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes RJ. (1993) Environmental enrichment for confined dogs and cats. In: Animal Behaviour-The TG Hungerford Refresher Course for Veterinarians, Proceedings 214 Holmes RJ, (ed.) Sydney: Post Graduate Committee in Veterinary Science, pp. 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office (1989) Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986—Code of practice for the housing and care of animals used in scientific procedures (issued under section 21). London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office (1995) Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986—Code of practice for the housing and care of animals in designated breeding and supplying establishments (issued under section 21). London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office (1998) Statistics of scientific procedures on living animals Great Britain 1997. London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins CM. (1995) The effects of positive handling on the behaviour of domestic cats in rescue centres. MSc. thesis, University of Edinburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins JD. (1996) Population medicine and infectious diseases. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 208, 510–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubrecht RC, Turner DC. (1998) Companion animal welfare in private and institutional settings. In: Companion Animals in Human Health, Wilson CC, Turner DC, (eds), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc., pp. 267–289. [Google Scholar]

- James AE. (1995) The laboratory cat. The Australian and New Zealand Council for the Care of Animals in Research and Teaching News 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Karsh EB, Turner DC. (1988) The human-cat relationship. In: The domestic cat: the biology of its behaviour Turner DC, Bateson P, (eds). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler MR. (1997) Katzenhaltung im Tierheim: Analyse des Ist-Zustandes und ethologische Beurteilung von Haltungsformen. Ph.D. thesis, Eidgenössischen Technischen Hochschule, Zurich.

- Kessler MR, Turner DC. (1997) Stress and adaptation of cats (Felis Silvestris Catus) housed singly, in pairs and in groups in boarding catteries. Animal Welfare 6, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd AH, Kidd RM, George CC. (1992) Veterinarians and successful pet adoptions. Psychological Reports 71, 551–557. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberg G. (1996) Feline behaviour and welfare. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 208, 502–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyhausen P. (1979) Cat behaviour: the predatory and social behaviour of domestic and wild cats. New York: Garland STPM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loveridge GG. (1994) Provision of environmentally enriched housing for cats. Animal Technician 45, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Loveridge GG, Horrocks LJ, Hawthorne AJ. (1995) Environmentally enriched housing for cats when housed singly. Animal Welfare 4, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Luke C. (1996) Animal shelter issues. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 208, 524–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCune S. (1992) Temperament and the welfare of caged cats. Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- McCune S. (1995) Enriching the environment of the laboratory cat—a review. In: Proceedings of the second international conference on environmental enrichment, Holst B. (ed.) Copenhagen: Copenhagen Zoo, pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- McCune S, McPherson JA, Bradshaw JWS. (1995) Avoiding problems: The importance of socialisation. In: The Waltham book of human–animal interaction: benefits and responsibilities of pet ownership Robinson I, (ed). Oxford: Elsevier Science Ltd, pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens C, Schär R. (1988) Practical aspects of research on cats. In: The domestic cat: the biology of its behaviour, Turner DC, Bateson P. (eds), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. (1996) The domestic cat: Perspective on the nature and diversity of cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 208, 498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (1995) The voluntary code of practice on the welfare of dogs and cats in quarantine premises. Surbiton, Surrey: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry RC. (1995) Environmental enrichment: Increasing the biological relevance of captive environments. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 44, 229–243. [Google Scholar]

- O'Farrell V, Neville P. (1994) The BSAVA manual of feline behaviour. Cheltenham: British Small Animal Veterinary Association. [Google Scholar]

- Patronek GJ. (1998) Free-roaming and feral cats—their impact on wildlife and human beings. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 212, 218–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patronek GJ, Beck AM, Glickman LT. (1997) Dynamics of dog and cat populations in a community. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 210, 637–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pet Food Manufacturers’ Association (1999). The pet food manufacturers’ association profile. Brussels: FEDIAF. [Google Scholar]

- Podberscek AL, Blackshaw JK, Beattie AW. (1991) The behaviour of laboratory colony cats and their reactions to a familiar and unfamiliar person. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 31, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Poole TB. (1997) Happy animals make good science. Laboratory Animals 31, 116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall WR, Cunningham JT, Randall S. (1990) Sounds from an animal colony entrain a circadian rhythm in the cat, Felis catus L. Journal of Interdisciplinary Cycle Research 21, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rochlitz I. (1997) The welfare of cats kept in confined environments. Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Rochlitz I, Podberscek AL, Broom DM. (1996) A questionnaire survey on aspects of cat adoption. Society for Companion Animal Studies Proceedings Glasgow, (Abstract) 65–66.

- Rochlitz I, Podberscek AL, Broom DM. (1998a) Effects of quarantine on cats and their owners. The Veterinary Record 143, 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochlitz I, Podberscek AL, Broom DM. (1998b) The welfare of cats in a quarantine cattery. The Veterinary Record 143, 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy D. (1992) Environmental enrichment for cats in rescue centres. BSc. thesis, University of Southampton. [Google Scholar]

- Salman MD, New JG, Jr., Scarlett JM, Kass PH, Ruch-Gallie R, Hetts S. (1998) Human and animal factors related to the relinquishment of dogs and cats in 12 selected animal shelters in the United States. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 1, 207–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell M. (1989) The mating tactics and spacing patterns of solitary carnivores. In: Carnivore behaviour, ecology and evolution Gittelman JL, (ed.), London: Chapman & Hall, pp. 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DFE, Durman KJ, Roy DB, Bradshaw JWS. (1994) Behavioural aspects of the welfare of rescued cats. The Journal of the Feline Advisory Bureau 31, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Turner DC. (1995) The human-cat relationship. In: The Waltham book of human-animal interaction: benefits and responsibilities of pet ownership Robinson I, (ed.), Oxford: Elsevier Science Ltd, pp. 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- UK Cat Behaviour Working Group (1995) UFAW animal workshop report no. 1: An ethogram for behavioural studies of the domestic cat (Felis catus L.). Potters Bar, Herts: Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bos R, de Cock Buning T. (1994a) Social and non-social behaviour of domestic cats (Felis catus L.): A review of the literature and experimental findings. In: Welfare and Science-proceedings of the fifth FELASA symposium, Bunyan J, (ed.), London: Royal Society of Medicine Press Ltd, pp. 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bos R, de Cock Buning T. (1994b) Social behaviour of domestic cats (Felis lybica f. catus L.): A study of dominance in a group of female laboratory cats. Ethology 98, 14–37. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bos R. (1998) Post-conflict stress-response in confined group-living cats (Felis silvestris catus). Applied Animal Behaviour Science 59, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Voith VL, Borchelt PL. (1986) Social behaviour of domestic cats. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practising Veterinarian 8, 637–645. [Google Scholar]

- Wells D, Hepper PG. (1992) The behaviour of dogs in a rescue shelter. Animal Welfare 1, 171–186. [Google Scholar]