Abstract

Feline chronic gingivo-stomatitis (FCGS) is a syndrome characterised by persistent, often severe, inflammation of the oral mucosa. In the absence of similar studies, our objective was to estimate the prevalence of FCGS in a convenience based sample of cats visiting first opinion small animal veterinary practices. Twelve practices took part, providing a sample population of 4858 cats. Veterinary surgeons identified cases of FCGS according to our case definition over a 12-week sampling period; age, sex and breed information was determined for all cats, plus brief descriptive data for FCGS cases. The prevalence of FCGS was 0.7% (34 cases, 95% confidence intervals: 0.5–1.0%). Of the 34 cases of FCGS, 44% (15 cats) were new cases and 56% (19 cats) were ongoing cases. No statistically significant difference (P>0.353) was found when the age, sex and breed of cats with FCGS were compared to data from cats without the condition.

Feline chronic gingivo-stomatitis (FCGS) is an inflammatory syndrome affecting the mouths of cats. It has also been referred to by various other names such as plasma cell stomatitis–pharyngitis (White et al 1992), chronic faucitis (Reubel et al 1992), chronic gingivitis and pharyngitis (Thompson et al 1984), lymphocytic plasmacytic gingivitis stomatitis (Lommer and Verstraete 2003), plasmacytic stomatitis–pharyngitis (Reindel et al 1987) and chronic stomatitis (Gaskell and Gruffydd-Jones 1977). These and other similar terms are thought to be interchangeable and refer to the same clinical presentation. FCGS can be very debilitating, difficult to treat, and sometimes results in euthanasia of the affected cat.

The presenting clinical signs of FCGS are symptomatic of the pain and inflammation in the mouth, and include dysphagia (sometimes anorexia), weight loss, halitosis, ptyalism (sometimes blood-stained), pawing at the mouth and reduced grooming (Gaskell and Gruffydd-Jones 1977, Harvey 1991, White et al 1992, Lommer and Verstraete 2003). Cats affected by FCGS typically present with inflammation of the oral mucosa which is disproportionately severe compared with visible dental disease and calculus accumulation. The lesions are commonly concentrated towards the caudal parts of the mouth, involving the palatoglossal folds (sometimes referred to as the fauces) in particular, with extension rostrally along the buccal and gingival mucosa, crossing the mucogingival junctions. The pharynx and the soft palate may also be involved, and (less commonly) the hard palate and the tongue (Gaskell and Gruffydd-Jones 1977, Harvey 1994, Hennet 1997).

The aetiology of FCGS remains uncertain, although a number of factors including various infectious agents, dental disease, genetic and breed factor, have been implicated. The main factors which have so far been considered as playing a role are either infectious or related to a cat's immune response. Infectious agents which have been implicated include feline calicivirus (FCV), feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), and possibly feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) or feline herpesvirus (FHV) (Cotter et al 1975, Thompson et al 1984, Knowles et al 1989, Tenorio et al 1991, Sato et al 1996, Lommer and Verstraete 2003); certain anaerobic bacterial species have also been implicated (Love et al 1989, Sims et al 1990). Immunological studies have found differences in cytokine expression and immunoglobulin profiles in cases compared with controls (Harley et al 1999, 2003) and it has also been suggested that immunosuppression caused by an unrelated health problem may play a role (Williams and Aller 1992). It seems likely, therefore, that the cause is multifactorial.

FCGS is considered to be a fairly common problem: in a survey of its members by the American Veterinary Dental Society, 72% of respondents indicated that they saw one or more cases of ‘gingivo-stomatitis’ per week (Frost and Williams 1986). In another study, ‘gingivitis’ was present in 13.1% of cats examined in private veterinary practices in the United States (Lund et al 1999) but the number of these cats which were affected by FCGS was not recorded. To the authors' knowledge, there are no published figures for the prevalence of FCGS in the population of cats visiting first opinion veterinary practices, and the risk factors for the disease are not fully defined. The aims of this study were to estimate the prevalence of new and existing cases of FCGS in cats visiting first opinion small animal veterinary surgeons in the North West of England over a 3-month period, and to collect data on the age, sex and breed of all cats in the same population.

Materials and methods

An initial 2-week pilot study was carried out at three veterinary practices; this identified a requirement for participating practices to have computerised records. Sixteen first opinion small animal veterinary practices in the North West of England were selected on a convenience basis to be recruited to the full study. Practices were first contacted by telephone and faxed an accompanying information sheet; this was followed up by a visit to practices that agreed to participate where a presentation was given to inform the veterinary surgeons of our case definition (Table 1), and study protocol. The presentation included an interactive discussion of each point of the case definition, illustrated by photographs of FCGS lesions. For the purposes of our case definition, the term ‘periodontal area’ referred to that part of the visible gingival margin immediately adjacent to the teeth, and the term ‘gingival mucosa’ referred to the whole visible gingival mucosa from the teeth to the mucogingival junction. The minimum requirement for a case to meet the case definition was that it should have inflammation of at least one of the locations in point one, and that point three must be met (‘the severity of the inflammation is worse than would be expected in the context of visible dental disease’).

Table 1.

Case definition for FCGS

|

For the purposes of the case definition periodontal area referred to that part of the visible gingival margin immediately adjacent to the teeth.

For the purposes of the case definition gingival mucosa referred to the whole visible gingival mucosa from the teeth to the mucogingival junction.

The sample population comprised ‘vet-visiting cats’ (cats examined in a consulting room by a veterinary surgeon) and sampling was carried out during normal working hours over a 12-week period. The age, sex and breed of all cats were extracted from the practice computer system (Table 2). The age at examination was calculated from the birth date and consultation date; if the consultation date was not known, an estimate of age was calculated from the birth date and start date of the sampling period. Cats were counted only once regardless of how frequently they were seen, and in the case of multiple visits, age was taken from the first consultation date.

Table 2.

Roles of practice computer systems in the collection of age, sex and breed data for the whole sample population

| Practice | Computer system | Microsoft Windows based | Computer search possible for age, sex and breed | Simple electronic transfer to spreadsheet possible |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | No | Entries on daylist printout looked up manually * | No |

| B | 1 | No | Entries on daylist printout looked up manually † | No |

| C | 1 (modified) | No | Yes | No |

| D | 1 (modified) | No | Yes | No |

| E | 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F | 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| G | 3 | No | Printout of all cat transactions: age/sex/breed looked up manually | No |

| H | 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| I | 5 | No | Yes | Yes |

| J | 6 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| K | 7 | No | Printout of cat consultations, age and sex; breed looked up manually | No |

| L | 8 | No | Yes | Yes |

Written record of appointments.

Computer generated daylist (list of consultations by date, typically including patient name and species, and client name and address).

Veterinary surgeons were also asked to record information on a short questionnaire for all cases of FCGS fitting the case definition (Table 1) over the 12-week sampling period. This included questions about whether each case was new or pre-existing, the location of the oral inflammation, whether there was any concurrent renal disease, any other relevant clinical problems, and the cat's FCV, FHV, FIV and FeLV status (where known). Vets were also asked to give a subjective assessment of the severity of dental disease present, selecting from a mutually exclusive choice of ‘absent’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’, ‘severe’ or ‘unknown’.

Statistical analysis

Basic statistical analyses were performed on the age, sex and breed results. The χ 2 test was used to analyse categorical variables (age and sex), and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables (age). A P value <0.05 was considered significant. Analysis was performed using Minitab 14 (Minitab, State College, PA, USA).

Results

Of the 16 practices approached, 12 (75%) agreed to participate (practices A to L). Of the four remaining practices, the reasons for non-participation were imminent change of practice ownership (one practice); non-computerised clinical records (one practice); two practices were not privately owned, and were denied permission to participate by their head office. Of the 12 participating practices, one was able to supply only 6 weeks of data due to problems with their computer system; the other 11 practices completed the sampling period.

Eight different computer systems were used by the participating practices; one system was used in four practices, one was used in two practices, and the remaining six practices all used different systems; the method of extraction of age, sex and breed data is summarised in Table 2.

During the 12-week study period, a total of 4858 cats were seen by the 12 practices, ranging from 66 to 893 at individual practices (Table 3). From these cats, 34 cases of FCGS were recorded indicating a prevalence of 0.7% (95%, confidence intervals: 0.5–1.0%): of these, 15 (44%) were new cases and 19 (56%) were ongoing cases (Table 3). The prevalence of FCGS at individual practices ranged from 0% to 2.5%.

Table 3.

Prevalence of FCGS at individual practices

| Practice | Number of cats seen | Number of cases of FCGS | Prevalence (%) | 95% * Confidence intervals | ||

| Total | New | Ongoing | ||||

| A | 79 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2.5 | 0.3–8.8 |

| B | 702 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.4 | 0.1–1.2 |

| C | 315 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1.3 | 0.3–2.9 |

| D | 544 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.4 | 0–1.3 |

| E | 528 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 1.3 | 0.5–2.7 |

| F | 170 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0–2.5 |

| G | 893 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.2 | 0–0.8 |

| H | 720 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.3 | 0–1 |

| I | 66 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 | 0–8.2 |

| J | 269 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.6–4.3 |

| K | 156 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0–2.8 |

| L | 416 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1.4 | 0.5–3.1 |

| All practices | 4858 | 34 | 15 | 19 | 0.7 | 0.5–1 |

Where the number of FCGS cases is zero, 97.5% confidence intervals are given.

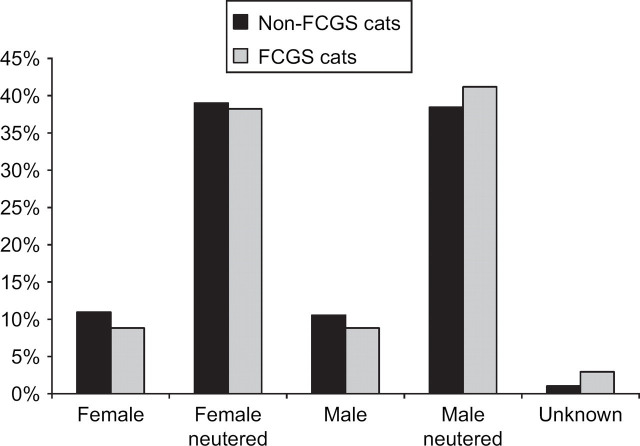

Sex distribution

Within the sampled population, 2428 (50%) of the cats were female and 2379 (49%) were male, with the sex of 51 (1%) being unknown (Fig 1). There was no significant difference (P=0.96) between the sex distribution of the whole sample population and the population of cats with FCGS, where 16 (47%) were female, 17 (50%) were male, and one (3%) was unknown (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Sex distribution in non-FCGS cats (n=4824) and in cases of FCGS (n=34).

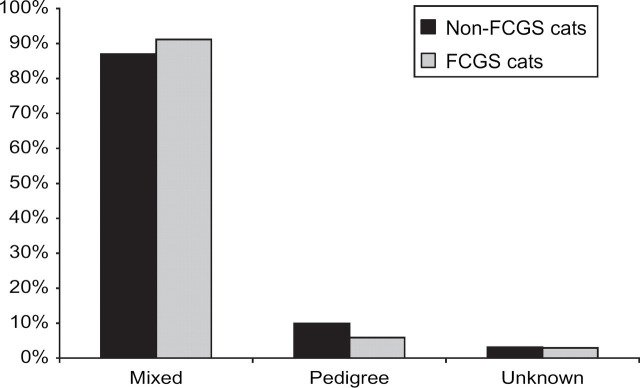

Breed distribution

Of the cats sampled, 4226 (87%) were cats of mixed breed (domestic short- medium- and longhair cats and pedigree crosses): 482 (10%) cats were pedigree, and 150 (3%) were of unknown or unrecorded breed (Fig 2). The trend for cats with FCGS was not significantly different from that of the whole sample population (P=0.4): 31 cats with FCGS (91%) were of mixed breed; 2 (6%) were pedigree (1 Persian and 1 Siamese), and 1 (3%) was unknown/unclassified (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Breed distribution in non-FCGS cats (n=4824) and in cases of FCGS (n=34).

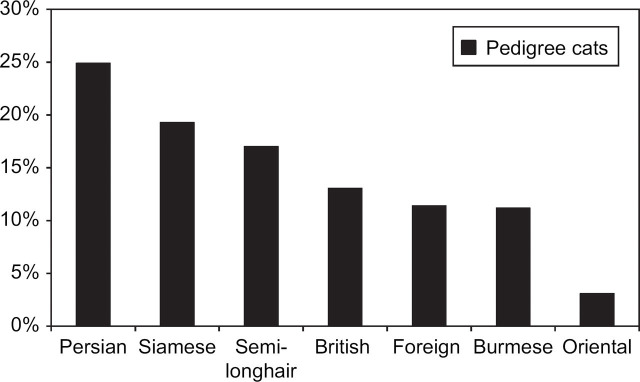

The breed distribution of the pedigree cats in the whole sample population is shown in Fig 3. The most popular groups were Persians (120 cats, 25%); Siamese (93, 19%); and semi-longhairs (82, 17%).

Fig 3.

Breed distribution in all pedigree cats in the sample population (n=480).

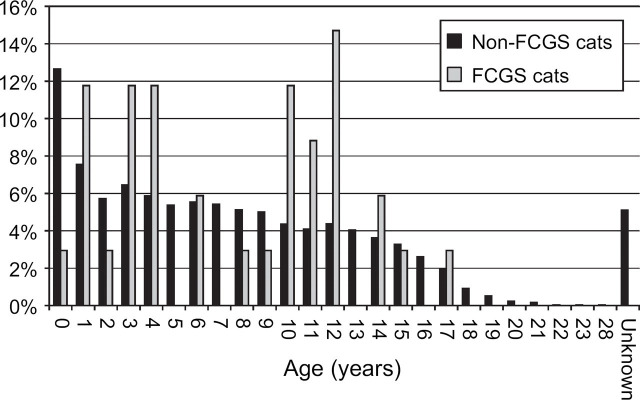

Age distribution

The median age of the sample population was 6 years, 8 months (range <1 month–28 years, 9 months); for 246 cats (5%), the age was unknown (Fig 4). Cats of less than 1 year of age were most commonly presented for examination (611, 13%). This dropped relatively sharply for cats of 1–2 years of age to (368, 8%), then decreased more gradually with increasing age before once more declining more rapidly as cats approached 16 years of age.

Fig 4.

Age distribution in non-FCGS cats (n=4824) and in cases of FCGS (n=34). Note: each age category (e.g. 1 year)=cats aged ≥1 year and <2years.

The age distribution of the pedigree subpopulation (median age 6 years, 6 months, range <1 month–20 years) was not significantly different from that of the mixed breed cats (P=0.4); however, there was a less marked over-representation of pedigree cats in their first year when compared with mixed breed cats (data not shown).

Although the numbers of FCGS cases were relatively small, there appeared to be two peaks in the age distribution among the cats with FCGS (Fig 4). The first occurred in cats aged 1–5 years, the second in the 10–13 years age group. There was a trend for the cats with FCGS to be older than those unaffected (median age of cats with FCGS: 8 years, 11.5 months; median age of cats without FCGS 6 years, 8 months); however, this was not statistically significant (P=0.3).

FCGS cat characteristics

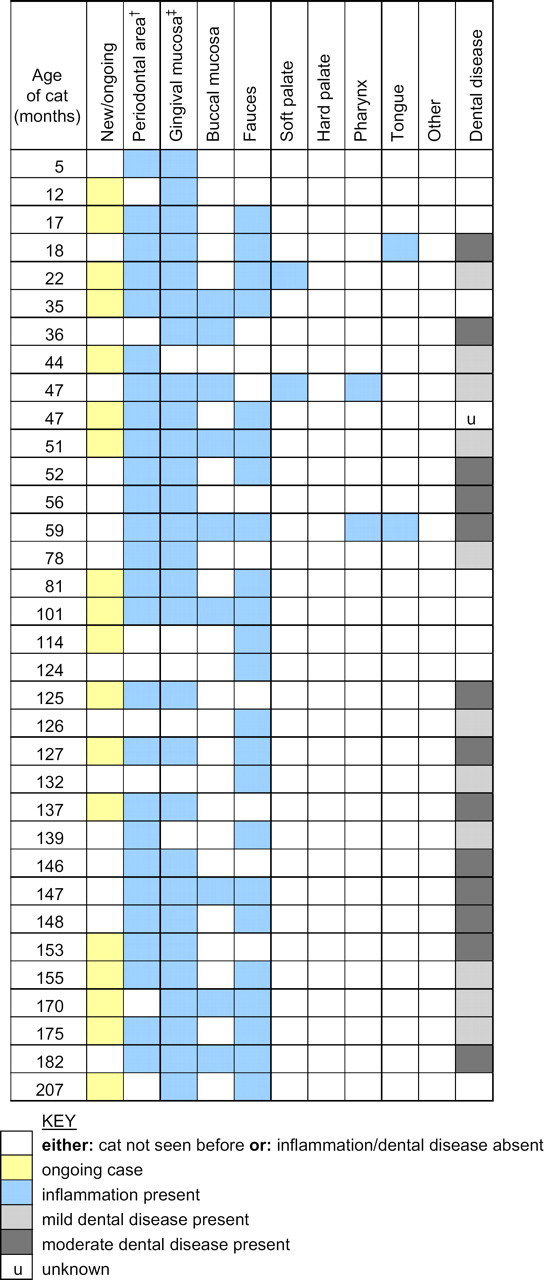

Twenty-eight (82%) of the 34 cats seen with FCGS had inflammation of the gingival mucosa (ie, the visible gingival mucosa from the teeth to the mucogingival junction); the periodontal area (ie, the part of the visible gingival margin immediately adjacent to the teeth) was affected in 26 cats (77%); the fauces in 23 (68%) and the buccal mucosa in 9 (27%) (Fig 5). The soft palate, pharynx and tongue were infrequently affected, and the hard palate was not inflamed in any cat.

Fig 5.

Characteristics of FCGS cases (n=34).

Visible dental disease was present in 24/34 (70%) of cases and was given a subjective assessment of either ‘mild’ (11 cats, 32%) or ‘moderate’ (13 cats, 38%). No cat was documented as having ‘severe’ dental disease. Dental disease was reported as absent in 9 (27%) of the 34 cats, and the severity of dental disease was recorded as ‘unknown’ in 1 cat (3%).

In 25 (74%) of the 34 FCGS cases, the renal disease status was unknown but renal disease was not suspected. In the remaining nine (26%) cats, blood biochemistry had not indicated any evidence of renal disease.

Some of the FCGS cases had undergone diagnostic testing for infection by viruses including FCV, FHV, FIV and FeLV. Five of seven cats tested (71%) were positive for FCV; one of eight tested (13%) was positive for FIV; no cats tested positive for FeLV (six tested) or FHV (two tested).

Discussion

This study found a prevalence of FCGS of 0.7% in a population of 4858 vet-visiting cats; to the authors' knowledge this is the first time the prevalence of FCGS in first opinion small animal veterinary practice has been assessed. In a US survey of members of the American Veterinary Dental Society, 72% of responses indicated that these veterinary surgeons saw one or more cases of ‘gingivo-stomatitis’ per week (Frost and Williams 1986). In another study, ‘gingivitis’ was present in 13.1% of cats examined in private veterinary practices in the United States (Lund et al 1999). The prevalence in the Lund study is much higher than in our study, but as case definitions were not imposed on veterinary surgeons this figure is unlikely to be specific to FCGS. In addition, it is possible that unlike our population, the previous studies may have included a referral caseload.

Although the present study was convenience based and restricted geographically to the North West of England, it nevertheless provides a prevalence estimate in the general, first opinion vet-visiting population from a sample population large enough to provide an estimate with good precision.

The clinical signs associated with FCGS have been well described in the literature (Gaskell and Gruffydd-Jones 1977, Johnessee and Hurvitz 1983, Harvey 1991, White et al 1992, Hennet 1997, DeForge 2004, Baird 2005). Our case definition comprised a list of those features which characterise FCGS. The only criteria of the case definition that each case had to fulfil, however, was that the inflammation should be present in at least one of the listed areas of the mouth, and seem excessive when compared with the extent of dental disease visible on conscious examination. This is because cats with FCGS can exhibit a varying range of clinical manifestations, and may not all have one common feature: White et al (1992) found that while certain clinical features were very common in a series of 40 cats with ‘plasma cell stomatitis–pharyngitis’, none was common to every cat.

The process of informing individual practices of the case definition should have optimised the specificity (reduced the number of false positives) of the study. In a minority of practices, due to the limitations of the computer system, it was necessary to check the clinical record of every cat seen during the study period. Of the 1194 records examined during this process, a total of six cases were found, of which five had been recorded by the veterinary surgeons (data not presented). This would suggest that although we believe the specificity to be high, our prevalence figure may be slightly low due to occasional true cases not being recorded.

Eight of the computer systems used by the study practices were newer, Windows-based systems. These tended to be more adaptable for our purposes, but there was enormous variation in the suitability of practice computer systems for data extraction such as was required for this study. This led to the requirement for a proportion of the data to be searched for and recorded manually. However, this problem is frequently eliminated in the more versatile, updated versions of the same systems.

The approximately equal number of male and female cats in the whole sample population in this study corresponds with an estimate of the UK cat sex distribution by Gaskell et al (2002) and a survey of a large population of vet-visiting cats in the USA (Lund et al 1999). A similar trend was seen in the subpopulation of cats with FCGS; this is consistent with previous findings (Johnessee and Hurvitz 1983, White et al 1992).

Siamese, Abyssinian, Persian, Himalayan and Burmese breeds have all been cited in the literature as being possibly predisposed to FCGS (Frost and Williams 1986, Diehl and Rosychuk 1993). The Somali, which originated from a long-haired mutation of the Abyssinian breed, has been documented as being predisposed to periodontal disease, although not FCGS specifically (Wiggs and Lobprise 1997). However, in the present study, the breed distribution of the FCGS cases appeared to mirror the trend of the whole sample population (the two pedigree cats with FCGS were Persian and Siamese, representing the two most popular breeds in the overall sample population). In a study by Hennet (1997) looking at 30 cases of FCGS, the majority were mixed breed cats, while three were Siamese, three Persian and one was Foreign. A pedigree sample population would need to be targeted to look more closely at the prevalence of FCGS in specific breeds, as pedigree cats are in a minority in the vet-visiting population of cats.

The median age of the whole sample population was 6 years, 8 months (range <1 month to 28 years, 7 months). Young cats (under 1 year of age) were presented at veterinary surgeries more commonly than cats of other ages. This may be a true reflection of the age distribution in the general cat population (including non-vet-visiting cats), or a result of the number of routine veterinary check-ups (eg, new kitten checks, primary vaccinations, pre-neutering checks) that take place at this time in the life of vet-visiting cats. After this first year, the gradual decline in the frequency of presentation of cats between 1 year and 16 years of age could be accounted for by a low but steady mortality rate; this decline proceeded more rapidly after 17 years of age, again probably due to increased death rate. A study by Lund et al (1999) also found that the number of vet-visiting cats peaked in the first year of life, this then initially fell but rose again during the ages of 4 and 7 years, before declining with increasing age. The median age of the vet-visiting cat population in the study by Lund et al (1999) was relatively low at 4.3 years of age.

The median age (8 years, 11.5 months) and range (5 months–17 years, 3 months) of cats in this study diagnosed with FCGS are comparable to data from other studies which have reported median ages of 7.1–8 years (range 4 months–17 years) (White et al 1992, Hennet 1997) and mean ages of 5.7–8.3 years (range 1.5–12 years) (Johnessee and Hurvitz 1983, Thompson et al 1984, Knowles 1988). Although the median age of cats with FCGS in our study is higher than that of the whole population, this difference is not statistically significant. Interestingly, in our study there also appeared to be two peaks in the ages of cats in the FCGS subpopulation (at approximately 1–5 years and 10–13 years), although numbers are relatively small. No obvious differences in clinical presentation were apparent between these two groups.

The most frequently identified locations of oral inflammation in our study (gingival mucosa (ie, visible gingiva from the teeth to the mucogingival junction), periodontal area (ie, the part of the visible gingival margin immediately adjacent to the teeth), and fauces (glossopalatine folds)) correspond well to the findings of White et al (1992) where the most common areas of oral inflammation were the gingiva and glossopalatine arches in a series of 40 cats with ‘plasma cell stomatitis–pharyngitis’ (the periodontal area was not evaluated as a distinct region in this study). In a series of 30 cats with ‘chronic gingivo-stomatitis’ evaluated by Hennet (1997), the findings were also similar, although less comparable to this study as slightly different terminology was used. All nine of the cats with ‘feline plasma cell gingivitis–pharyngitis’ studied by Johnessee and Hurvitz (1983) suffered from gingivitis, faucitis and inflammation of the palatopharyngeal arch. Tongue lesions were not documented in this study, but accounted for a small proportion of cats in our study and those by White et al (1992) and Hennet (1997).

Dental disease was common (71%, 24 cats) among the FCGS cases in our study, although all were subjectively classified as mild or moderate; no cases were described as having severe dental disease (although such cats were not specifically excluded by the case definition). Information on the dental disease status of this study's whole sample population was not collected; Lund et al (1999) found 24.2% of cats had dental calculus, and 13.1% gingivitis in a survey of vet-visiting cats in the USA. It is, however, difficult to correlate these figures with the dental disease assessed in our study, particularly as case definitions were not used in either study for this factor.

Veterinary surgeons were asked about the renal status of the cases to assess whether uraemic ulceration of the mouth could be a possible differential diagnosis. However, renal disease was neither diagnosed by blood tests nor suspected on clinical examination (in the cats where blood tests had not been performed) in any of the cases of FCGS in our study. This is a similar finding to other studies where blood biochemistry analysis showed no evidence of renal failure (Johnessee and Hurvitz, 1983, White et al 1992). However, in one study by Hennet (1997), 3 of 30 cats with ‘chronic gingivo-stomatitis’ were diagnosed with chronic renal failure. As few of the FCGS cases in our study were tested for renal disease, we cannot exclude the possibility of a low level of renal disease.

The results of virus testing were present for only a small number of the cats with FCGS and, therefore, were not suitable for statistical analysis. However, it is interesting to note that the high prevalence of FCV and low prevalence of FeLV are similar to previous findings (Johnessee and Hurvitz 1983, Thompson et al 1984, Knowles et al 1989, Harbour et al 1991). The prevalence of FIV corresponds very well with the findings of Hennet (1997) but is markedly lower than the prevalence of FIV in other studies (Knowles et al 1989, White et al 1992). Tenorio et al (1991) reported a trend for cats with increasing severity of oral disease to be more likely to be infected with FCV and FIV. The absence of FHV found in our study corresponds with the absence or low level of FHV found in other studies (Thompson et al 1984, Harbour et al 1991), although another study found that co-infection with FCV and FHV was present in 22 of 25 cats with ‘chronic gingivo-stomatitis’ (Lommer and Verstraete 2003). The reason for the high prevalence of FHV in this latter study is unclear.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated a prevalence of 0.7% for FCGS in cats visiting first opinion veterinary surgeons in North West England. Despite being a low prevalence, FCGS represents a serious and chronic disease and, therefore, constitutes a genuine welfare concern in the population of vet-visiting cats. No significant difference was found when comparing the age, sex and breed trends of the FCGS cats with unaffected cats. However, it would be interesting to examine a larger number of cats with FCGS to determine whether the two apparent age peaks are an artefact resulting from the small number of cases, or whether they are a true reflection of the population of affected cats.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the veterinary practices and computer system companies for their time and enthusiasm: their participation made this study possible. The Cat Welfare Trust, the British Veterinary Association Animal Welfare Foundation and the University of Liverpool funded this work.

References

- Baird K. Lymphoplasmacytic gingivitis in a cat, Canadian Veterinary Journal 46 (6), 2005, 530–532. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter S.M., Hardy W.D., Jr., Essex M. Association of feline leukaemia virus with lymphosarcoma and other disorders in the cat, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 166 (5), 1975, 449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeForge D. Images in veterinary dental practice, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 224 (2), 2004, 207–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl K., Rosychuk R.A.W. Feline gingivitis–stomatitis–pharyngitis, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 23 (1), 1993, 139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost P., Williams C.A. Feline dental disease, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 16 (5), 1986, 851–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell R.M., Gruffydd-Jones T.J. Intractable feline stomatitis, Veterinary Annual 17, 1977, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell R.M., Gettinby G., Graham S., Skilton D., Gray A., Knivett S., Leavey A., Mackay D. Veterinary Products Committee (VPC) working group on feline and canine vaccination: final report to the VPC, www.vpc.gov.uk/reports/catfogvetsurv.pdf, 2002. [PubMed]

- Harbour D.A., Howard P.E., Gaskell R.M. Isolation of feline calicivirus and feline herpesvirus from domestic cats 1980–1989, Veterinary Record 128, 1991, 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley R., Helps C.R., Harbour C.A., Gruffydd-Jones T.J., Day M.J. Cytokine mRNA expression in lesions in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis, Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology 6 (4), 1999, 471–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley R., Gruffydd-Jones T.J., Day M.J. Salivary and serum immunoglobulin levels in cats with chronic gingivo-stomatitis, Veterinary Record 152, 2003, 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey C.E. Oral inflammatory disease in cats, Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 27, 1991, 585–591. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey C.E. Stomatitis. Sherding R.G. The Cat: Diseases and Clinical Management, 2nd edn, 1994, WB Saunders: Philadelphia, USA, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Hennet P. Chronic gingivo-stomatitis in cats: long-term follow-up of 30 cases treated by dental extractions, Journal of Veterinary Dentistry 14 (1), 1997, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Johnessee J.S., Hurvitz A.I. Feline plasma cell gingivitis–pharyngitis, Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 19, 1983, 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles JO. (1988) Studies on feline calicivirus with particular reference to chronic stomatitis in the cat. PhD thesis, University of Liverpool.

- Knowles J.O., Gaskell R.M., Gaskell C.J., et al. Prevalence of feline calicivirus, feline leukaemia virus and antibodies to FIV in cats with chronic stomatitis, Veterinary Record 124, 1989, 336–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lommer M.J., Verstraete F.J.M. Concurrent oral shedding of feline calicivirus and feline herpesvirus-1 in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis, Oral Microbiology and Immunology 18, 2003, 131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love D.N., Johnson J.L., Moore L.V. Bacteroides species from the oral cavity and oral associated diseases of cats, Veterinary Microbiology 19 (3), 1989, 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E.M., Armstrong P.J., Kirk C.A., et al. Health status and population characteristics of dogs and cats examined at private veterinary practices in the United States, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 214 (9), 1999, 1336–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reindel J.F., Trapp A.L., Armstrong P.J., et al. Recurrent plasmacytic stomatitis–pharyngitis in a cat with esophagitis, fibrosing gastritis and gastric nematodiasis, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 190 (1), 1987, 65–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubel G.H., Hoffmann D.E., Pedersen N.C. Acute and chronic faucitis of domestic cats, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 22 (6), 1992, 1347–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato R., Inanami O., Tanaka Y., et al. Oral administration of bovine lactoferrin for treatment of intractable stomatitis in feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)-positive and FIV-negative cats, American Journal of Veterinary Research 57 (10), 1996, 1443–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims T.J., Moncla B.J., Page R.C. Serum antibody response to antigens of oral Gram-negative bacteria in cats with plasma cell gingivitis–stomatitis, Journal of Dental Research 69 (3), 1990, 877–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenorio A.P., Franti C.E., Madewell B.R., et al. Chronic oral infection of cats and their relationship to persistent oral carriage of feline calici, immunodeficiency, or leukaemia viruses, Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 29, 1991, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R.R., Wilcox G.E., Clark W.T., Jansen K.L. Association of calicivirus infection with chronic gingivitis and pharyngitis in cats, Journal of Small Animal Practice 25, 1984, 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- White S.D., Rosychuk R.A., Reinke S.I., et al. Plasma cell stomatitis–pharyngitis in cats: 40 cases (1973–1991), Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 200 (9), 1992, 1377–1380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggs R.B., Lobprise H.B. Periodontology. Wiggs R.B., Lobprise H.B. Veterinary Dentistry: Principles and Practice, 1st edn, 1997, Lippincott-Raven Publishers: Philadelphia, USA, 186–231. [Google Scholar]

- Williams C.A., Aller M.S. Gingivitis/stomatitis in cats. Harvey C.E. Feline Dentistry. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 1992, 1361–1383, (Philadelphia, USA: WB Saunders; ). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]