Abstract

Anesthetic-associated death (AAD) in cats is infrequent, but occurs far more frequently than in people. Post-mortem investigations of AAD in cats are uncommon, and results only sporadically published. Here we report the findings in 54 cases of AAD in cats. Significant gross and/or microscopic pre-existing disease, including pulmonary, cardiac, and systemic disease, was detected in 33% of cases. Pulmonary disease was most frequently diagnosed (24% of cases), and included cases of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus infection (9% of cases). Heart disease, including two cases of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, was less frequent (11% of cases). Four percent died from surgical complications. No significant gross or microscopic disease was detected in 63% of cases. Additional studies are needed to determine if these findings are representative of AAD in cats in other geographic areas or with access to veterinary care. This study demonstrates that post-mortem investigation of AADs is an important and worthwhile endeavor.

Anesthetic-associated death (AAD) has been variably defined as death occurring within 24 or 48 h of anesthetic administration, or at any time, so long as the cause of death is relatable to anesthesia.1–5 In human pathology, AAD investigations are often legally mandated. These investigations, in combination with studies of anesthesia-associated mortality risk, have been credited with making anesthesia safer for people over the past 70 years, reducing the AAD rate in the US from roughly one per 1000 procedures to one per 100,000 procedures. 6

Post-mortem investigations of animals with AAD are uncommon, with few, sporadic reports of findings on a small number of cases.7,8 Because there have been no systematic investigations to examine the lesions, diseases, or mechanisms of AADs in veterinary medicine, there is minimal information available on the nature and frequency of lesions in animals that experience AAD. For instance, although it is an adage that cats that die unexpectedly perioperatively often have hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), no data exist to support this statement. The lack of studies cannot be blamed on lack of AAD cases, for although AADs in day-to-day veterinary practice are relatively rare events, the AAD rate for cats is approximately 2.4 per 1000 procedures. 4 Although comparisons of mortality data between humans and cats must be done cautiously, due to differences in patient populations and different disease severity profiles, the anesthetic death rate for cats is roughly an order of magnitude greater than that of people. 9

The purpose of post-mortem AAD investigation in veterinary medicine is to determine the cause of death, primarily by ruling in or out surgical complication or concurrent disease complicated by anesthesia. There are no known pathognomonic or even typical gross or histopathologic findings for anesthesia-related deaths. As a result, post-mortem investigations of AADs are likely to be either informative (ie, surgical complication or disease discovered) or neutral (ie, no disease discovered).

High quality, high volume spayeneuter organizations (HQHVSNOs) are surgical initiatives that perform sterilization of large numbers of dogs and cats, and which meet or exceed established veterinary medical guidelines of care. 10 Investigating AADs in cats served by HQHVSNOs offer a unique opportunity to study the pathologic findings in cases of AAD. Firstly, these programs perform the same surgical procedures on large numbers of cats. Together, the two programs in this study spay or neuter more than 25,000 cats per year. The surgeries are planned, nonemergency, elective procedures. Also, cats presented to these clinics are ostensibly in good health, with an assessed or assumed (in the case of cats unable to be physically examined) to be of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Scale Class I or II (Table 1). This degree of standardization reduces or eliminates variables such as surgical procedure, urgency of procedure, monitoring methods and equipment, and general health status, variables which have been shown to correlate with risk of anesthetic death in animals. 4 The rates of AADs in these two HQHVSNOs are generally low, at 0.8 and 1.6 per 1000 procedures (LA and MS, personal communication); due to varying anesthetic protocols and procedures as well as underlying health issues, AAD rates likely vary in different practice settings. Finally, investigating AADs in this population of cats could also yield important information about the health status of cats with limited or no veterinary care.

Table 1.

ASA Physical Status Scale (http://www.asahq.org/clinical/physicalstatus.htm)

| Patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Class I | Normal, healthy |

| Class II | Mild systemic disease |

| Class III | Severe systemic disease |

| Class IV | Severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life |

| Class V | Moribund patient; not expected to survive without surgery |

Class VI, not applicable to veterinary medicine, is not included.

Materials and methods

A retrospective study of post-mortem investigations of AAD in domestic cats from HQHVSNOs was conducted at Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine. Cases of AAD were defined as death within 24 h of receiving anesthetic agents. Cases of AAD were submitted from two HQHVSNOs. One, operating in central upstate New York (CNY), submitted cases between May 2009 and December 2010. The other, in the greater New York City (NYC) area, submitted cases between February 2009 and August 2010. Cats served by the HQHVSNOs included: owned cats from low-income households, cats in shelters, unowned cats with regular human supervision and/or interaction (stray cat colonies, barn cats, etc), and unowned trapped feral cats. A variety of anesthetic drugs, used in varying combinations at varying dosages, were used by the programs over the course of the study period.

All post-mortem investigations were conducted by the Section of Anatomic Pathology. A complete necropsy, following standard procedures, was performed within 12–48 h of receiving the body. 11 Bodies were received both fresh and frozen. In all cases, a full set of tissues were collected and fixed in 10% formalin. The tissues processed for histology were dependent upon the gross findings in the case. In nearly all cases, histologic examination of major organs, including the heart, lung, brain, liver and kidneys, plus any lesions, was performed in addition to the gross inspection. In rare cases, histology was not performed as the cause of death was conclusively determined from the gross inspection (ie, hemoabdomen) or initial histologic evaluation. In some cases, additional special stains and immunohistochemistry were performed in order to confirm or refute the differential diagnosis (eg, panleukopenia, HCM, etc). The presence or absence of significant disease, defined as pre-existing natural disease that would have increased anesthetic risk of death, was determined by the pathologist in charge of the case. At the end of the study period, all submission information, final necropsy reports, and all histologic sections were reviewed by one of the authors (JG). Rare discrepancies between the initial interpretation and those based on review (JG) were resolved by a third evaluation (SPM) to arrive at a consensus diagnosis.

Results

At the end of the study period, 56 cases had been submitted for necropsy by two HQHVSNOs. In two of these cases, the cats died 6 or more days after anesthesia and surgery. These cases, in which the cause of death was determined to be septic peritonitis and panleukopenia (feline parvovirus), respectively, were excluded.

In total, 54 cases met the inclusion criteria for the study, including 33 females and 21 males. Both populations of cases of AADs were composed primarily of young adult cats weighing approximately 3 kg (Table 2). From the CNY group, two cases were unowned cats, three cases were owned cats, and seven cases were not specified. From the NYC group, 33 cases were unowned cats, and nine cases were owned cats.

Table 2.

For all cases submitted, the body weight was recorded at the time of necropsy. In many cases, the age was estimated. In 10 cases, the age was not given and was recorded as ‘adult’ at the time of necropsy

| NYC cats | CNY cats | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Weight (kg) | n = 42 | n = 12 |

| Mean | 3.0 | 3.2 |

| Median | 2.7 | 3.2 |

| Range | 1–5 | 1.8–4.3 |

| Age (years) | n = 34 | n = 10 |

| Mean | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| Median | 1 | 1.25 |

| Range | 0.16–6.5 | 0.29–6 |

Fifty-two cases submitted were of cats that went into cardiopulmonary arrest, within a period of minutes to 24 h, from the time of premedication administration. Of the cats that arrested, two were resuscitated but euthanased a short time later, due to persistent neurologic deficits (non-responsiveness). In two cases, the cats were euthanased within 24 h of anesthesia, due to failure to recover appropriately from anesthesia and surgery, characterized by persistent lateral recumbency and decreased responsiveness. Panleukopenia infection was diagnosed prior to euthanasia in one of these two cases.

Twenty-eight cats died following administration of a combination of pre-medications and induction agents, prior to surgery. One cat died following administration of pre-medications alone. Four cats died intra-operatively and 21 cats died postoperatively.

Significant natural disease was identified in 18 cases (33%) based on gross and/or histologic findings. Surgical complication was discovered in two cases, both of which had hemoabdomen and died postoperatively (4%). Post-mortem investigation did not reveal any significant gross or histologic lesions in 34 cases (63%).

Significant natural disease was detected and categorized as follows: pulmonary disease (n = 13); cardiac disease (n = 6); systemic disease (n = 4) and central nervous system (CNS) disease (n = 1). Five cases had both heart and lung disease and one case had both cardiac and CNS disease.

Over half of the cases with natural disease had pulmonary lesions (n = 13), including: Aelurostrongylus abstrusus infection (five cases), asthma (three cases), acute aspiration pneumonia (one case), and pneumonia (four cases) with no clear etiology and varying cellular infiltrates (eosinophils, lymphocytes, etc). A abstrusus infection was often evident grossly, with dozens of small, multifocal and randomly scattered pale pink foci which exuded a foamy liquid (Fig 1). Histologically, myriad eggs and L1 larvae in alveoli and bronchi, respectively, were evident (Figs 2, 3 and 4). Rarely, 125 μ long adults, characterized by a thin cuticle, coelomyarian—polymyarian musculature and a pseudocoelom containing intestines, were seen in larger airways. Of the five cases of A abstrusus infection, four came from the CNY area; cases of A abstrusus infection included two owned cats, two feral cats, and one cat from a shelter. Feline asthma was diagnosed based on the presence of classic histologic features of pulmonary smooth muscle hyperplasia and hypertrophy, peribronchial gland hyperplasia, and interstitial eosinophilic infiltrates (Fig 5).

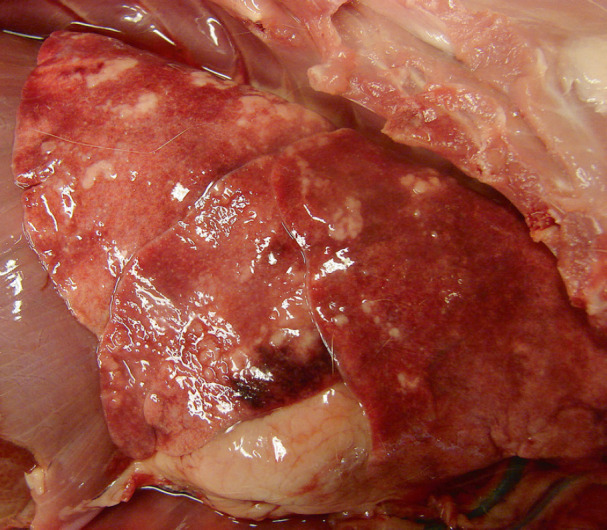

Fig 1.

Photo of the lung, taken at necropsy, of a cat that had cardiopulmonary arrest during induction of anesthesia. Multifocal to coalescing, tan to white, slightly raised, soft, nodular areas bulge from the pulmonary parenchyma. On section the areas exuded off-white foam. Although this gross appearance is not pathognomonic for A abstrusus infection, histologic examination confirmed this differential diagnosis.

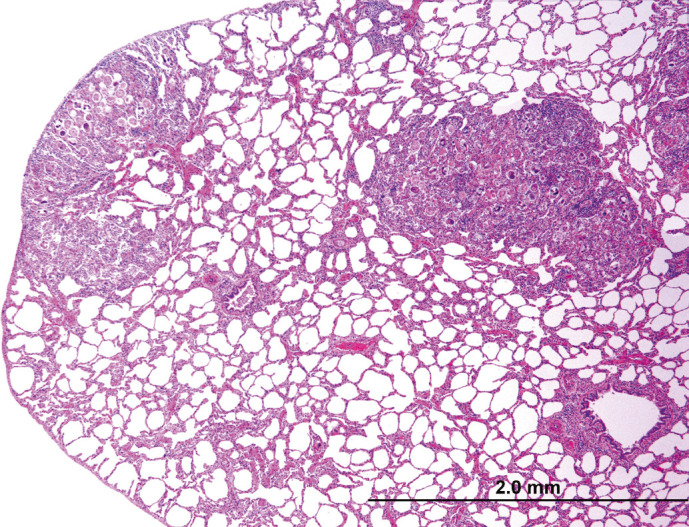

Fig 2.

Histologic section of lung. Multifocally, alveoli are occluded by a combination of parasite eggs, larvae, and infiltrating leukocytes.

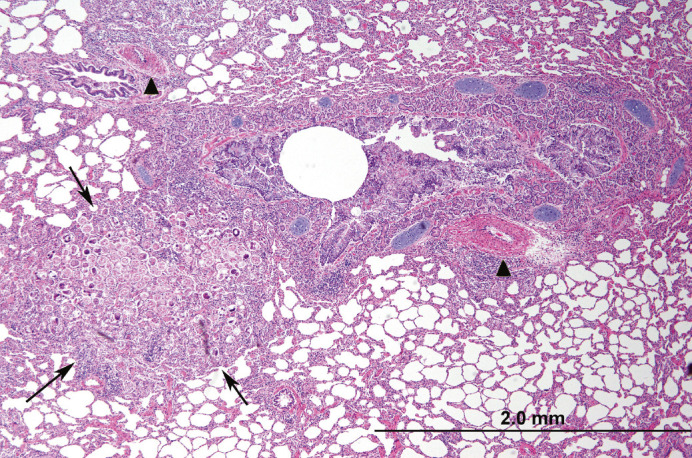

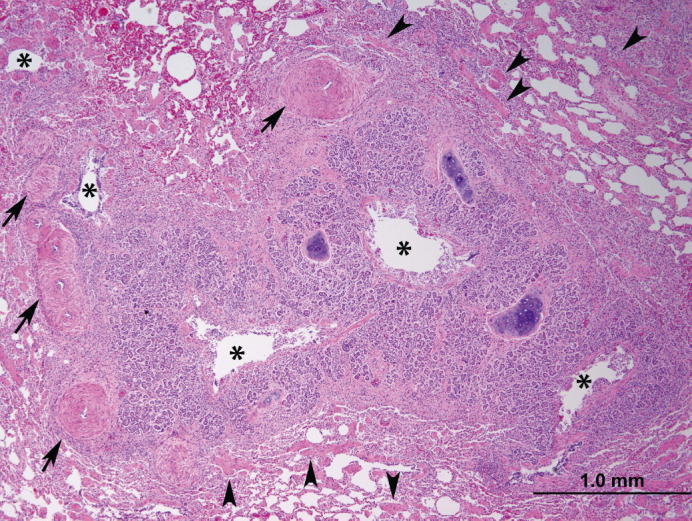

Fig 3.

Histologic section of lung. Adjacent to a secondary bronchus (central clear circular area), alveoli contain a combination of parasite eggs, larvae, and infiltrating leukocytes (arrows). Note multifocal pulmonary arterial muscular wall hypertrophy and hyperplasia (arrowheads). Peribronchial glands are also mildly hyperplastic.

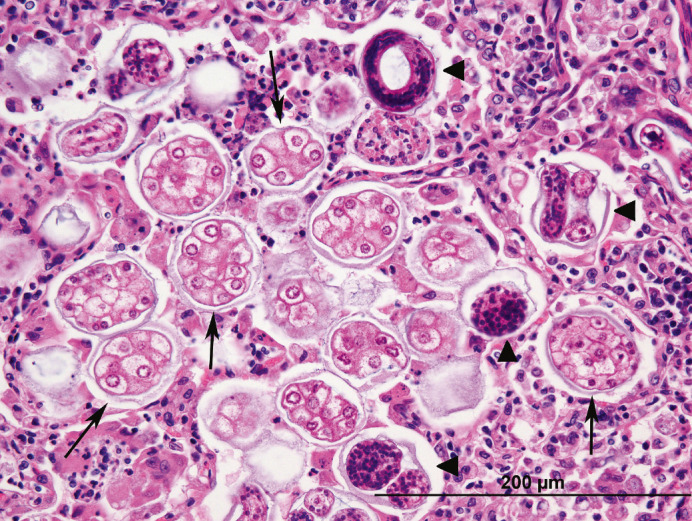

Fig 4.

Histologic section of lung. Filling alveoli are A abstrusus eggs, macrophages, degenerate neutrophils, and fewer lymphocytes. Eggs contain approximately a dozen 7–10 μm, pale eosinophilic, round blastomeres (arrows) or nascent L1 larvae (arrowheads), characterized by a brightly eosinophilic cuticle and basophilic stippled interior.

Fig 5.

Histologic section of lung. Surrounding multiple cross sections of a secondary bronchus are severely hyperplastic peribronchial glands which narrow the lumen (asterisks). Smooth muscle in the surrounding parenchyma is moderately to severely hypertrophied and hyperplastic (arrowheads). The pulmonary arteries in this case were also tortuous, evidenced by increased numbers of cross sections; the tunica media of pulmonary arteries is also moderately hyperplasic and hypertrophied (arrows).

Of the six cases of heart disease, there were two cases of HCM and four cases of lymphocytic myocarditis of unknown etiology. Cases of HCM were diagnosed based upon a fresh heart weight of over 20 g in addition to thickening of the left ventricular free wall and septum, with or without concurrent thickening of the right ventricular free wall (Fig 6); the diagnosis was supported by histologically subtle and localized irregular and obtuse myocardiofiber branching. 13 Lymphocytic myocarditis was only diagnosed on histologic examination. In two cases, myocardial toxoplasmosis was suspected, but organisms could not be identified by immunohistochemical methods.

Fig 6.

Cross section of a fresh heart from a domestic shorthair cat with HCM. The width of the left ventricular free wall and septum is severely increased, and the diameter of the left ventricular lumen severely decreased (concentric hypertrophy). The right ventricular free wall width is within normal limits. This heart weighed 24 g; the body weighed 4.05 kg. Scale in centimeters. Photo courtesy Dr Tim Cushing DACVP.

Systemic disease was diagnosed in three cases. Panleukopenia was found in two cases, based on the presence of necrotizing enteritis, and confirmed with immunohistochemical staining for panleukopenia antigen. Systemic toxoplasmosis, characterized by hepatitis and myocarditis with mixed inflammatory infiltrates, was suspected in one case, although organisms could not be identified by immunohistochemical methods.

CNS disease, specifically meningoencephalitis, was diagnosed in one case, based on the presence of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes in the cerebrum and meninges. Again, toxoplasmosis was suspected, but tachyzooites could not be demonstrated in areas of inflammation by immunohistochemical methods.

Hepatic lesions were noted only in three cases, and only by histologic examination. All three cases demonstrated multifocal random hepatitis. In one case, toxoplasmosis was suspected as myocarditis was also noted. In the other Two cases of hepatitis, small foci of neutrophils with hepatocyte loss, along with hepatic extramedullary hematopoiesis, were the only lesions noted. These lesions were not considered extensive enough to have contributed significantly to death.

The two cats diagnosed with postoperative hemoabdomen were both were female, and all ligatures were in place. Additional evidence of a bleeding diathesis, such as significant hemorrhage or petechiation in other locations (body wall, skin, mucous membranes) was not noted.

None of the 54 cases included in the study had significant gross or histologic evidence of renal disease.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that post-mortem investigations of animals with AAD can yield important information about occult infectious and idiopathic disease, especially lung, heart, and systemic infections. Although this study was limited to cats with minimal access to veterinary care, including feral cats, the finding of a high frequency of occult pulmonary disease also has implications for surgical candidates that are recently adopted stray cats or owned cats that spend a large percentage of time outdoors.

A abstrusus and anesthesia

The high frequency of cases of A abstrusus was unexpected. The reported prevalence of infection rates of A abstrusus in domestic cats varies widely among studies (1–22%), due to differences in the studies' geographic area, methods of detection, and the nature of the populations studied e owned versus stray cats. 14 Some studies suggest that stray cats have higher rates of infection.14,15 Interestingly, an equal number of owned and feral cats were diagnosed post-mortem with A abstrusus infection in this study.

A abstrusus is a metastrongyloid nematode parasite with worldwide distribution. Adult worms reside in the terminal bronchioles of cats, the definitive host. Females lay eggs which molt into first stage larvae (L1) in alveoli. These L1 larvae are then coughed up and eliminated through the feces, which contaminate the environment and infect gastropods (snails and slugs), the intermediate host. After molting to the third larval stage (L3) in intermediate hosts, L3 larvae are infective for cats, but L3 larvae are also carried by paratenic hosts: birds, rodents, frogs and lizards. L3 larvae ingested by cats migrate from the intestine to the lung, and develop into adult (L5) worms. Eggs are deposited in cats' lungs 25 days after infection; however, it takes 40 days for L1 larvae to develop and pass in the feces where they can be detected. 16 Cats eliminate the infection after approximately 5 months and cannot be re-infected. 17 Clinical disease in infected cats is rarely reported, but can include coughing, dyspnea, bronchopneumonia, and in rare cases, spontaneous pneumothorax. The gold standard for diagnosis is a Baerman fecal examination. 18 In this study, a majority of the cats diagnosed post-mortem with A abstrusus came from the CNY area; this may reflect differences in food sources available, with greater access to paratenic hosts in more rural areas.

A abstrusus infection in cats results in granulomatous pneumonia. A combination of eggs, L1 larvae and macrophages fill alveoli, reducing available surface area for gas exchange (Fig 2). A abstrusus infection also results in hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the tunica muscularis of pulmonary arteries and smooth muscle hypertrophy throughout the lung. 19 In one study of experimental infection, these changes were shown to persist for over a year. 20 Hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the smooth muscle of pulmonary arteries is also induced by Dirofilaria immitis infection in cats, and has been shown to result in pulmonary hypertension. 21 Although pulmonary hypertension has not been conclusively demonstrated in cats with A abstrusus, it is reasonable to suspect it occurs, based on the similarity of vascular changes. No gross or histologic evidence of right ventricular free wall hypertrophy, a sequelae of chronic pulmonary hypertension, was noted in any of the cases of A abstrusus infection; however, the relationships between the duration and degree of pulmonary hypertension and effect on the right ventricular free wall thickness is not well characterized in cats.

In people with pulmonary hypertension, anesthetic drug-induced decreases in heart rate and/or systemic blood pressure result in a sudden drop in pulmonary perfusion, and an attendant decrease in the volume of blood returned to the left ventricle. 22 Similarly, when sedated or anesthetized, cats infected with A abstrusus may no longer be able to compensate for decreased gas exchange surface area and (presumed) pulmonary hypertension, resulting in a precipitous drop in blood oxygen saturation and decreased left ventricular filling. With lung perfusion and ventilation significantly compromised, these cats would rapidly succumb to a combination of hypoxia and systemic hypotension, culminating in cardiovascular collapse and arrest.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of A abstrusus in the populations studied is unknown, as is the percentage of cats infected with A abstrusus that survived anesthesia and surgery. Disease prevalence investigations into this population of cats could help clarify the role of this parasite in AADs.

Other lesions

The proportional mortality ratio of HCM within the AAD study group was 4% (2/54). The small number of cases would seem to contradict the adage that AADs are often due to HCM. The etiology of the four cases of lymphocytic myocarditis is unknown, and although toxoplasmosis was often suspected in these and other cases, tachyzooites were not detected using immunohistochemical stains. However, the small size of the infective form of Toxoplasma gondii, tachyzooites, measure approximately 5 × 2 μm, which makes identification challenging in the majority of toxoplasmosis cases. Only a few of the tiny T gondii tachyzooites are needed to incite significant inflammation however, and so the absence of organisms in histologic section does not conclusively rule out this differential diagnosis. Additional diagnostic techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) would have been more sensitive for detection of T gondii organisms had cost not been a constraint in this study. Differential diagnoses for primary lymphocytic myocarditis in cats also includes Bartonella henselae, a wide variety of systemic infectious agents may spread to the heart. Myocarditis may also be seen in association with cardiomyopathy, although no other evidence of cardiomyopathy was seen in the four cases of lymphocytic myocarditis.

In the two cases of hepatitis with small foci of neutrophilic infiltration and hepatocyte loss and extramedullary hematopoiesis, an acute bacterial shower from portal blood was suspected, as was infection with Mycoplasma haemofelis. However, neither case had additional histologic changes, such as icterus, splenic hemosiderosis, or lymphadenopathy, to support a diagnosis of M haemofelis.

Finding cases of panleukopenia in this population of young, largely unvaccinated cats were unsurprising. Clearly, more studies of cats with AAD need to be investigated to determine if the population studied here is representative of AADs of owned cats with regular veterinary care.

Both cases of hemoabdomen were diagnosed in females, and no other evidence of a bleeding diathesis was noted at necropsy. As all ligatures were in place, we suspect that an ovarian or uterine artery retracted proximal to the level of the ligature, effectively releasing the artery from ligation. Alternatively, ligatures may not have adequately constricted the artery.

Cases without gross or histologic findings

The implications in cases without gross or histologic findings are limited. What can be said conclusively is that death occurred in association with anesthesia, and no gross or histologic evidence of significant, complicating disease was detected. Ultimately, these cases are best labeled as ‘AAD of unknown etiology’. Note that this categorization only specifies the circumstances of the death, and is not the same as or tantamount to concluding that death was solely or primarily due to anesthesia.

All parties involved in an AAD investigation should be aware that many fatal anesthetic complications cannot be detected by post-mortem investigations. These include mechanical causes of death such as upper airway occlusion by the soft palate or improper endotracheal intubation, biochemical derangements such as respiratory acidosis secondary to hypoventilation, and cardiac conduction abnormalities. It is important to note that proving death due to drug-specific side effects or anesthetic overdose, using post-mortem toxicological analysis, is currently not feasible in veterinary medicine.

Cases of AAD with occult disease were diagnosed as ‘AAD with [disease entity],’ because it is the anesthetic effects in combination with the disease state(s) that precipitate death. Complicating diseases considered significant should be limited to those body systems which are affected by or have a profound effect upon anesthesia, including the respiratory system, cardiovascular system, nervous system, and renal and hepatic (drug-metabolizing) systems. Systemic disease states, including both infectious and non-infectious diseases (neoplastic, idiopathic, etc), also have the potential to have a profound impact on anesthesia and risk, as reflected in the ASA Physical Status Scale. Only in those cases where the patient could be expected to die regardless of anesthesia, can the anesthetic setting of the death potentially be disregarded. 2

Using standardized terminology in pathology reports for cases of AADs will more clearly reflect the nature and circumstances of the death, and allow easier identification of these cases and compilation of data, so that population-based studies of risk factors for AAD can be conducted in the future.

Study limitations

The amount of case-related information recorded in Cornell's necropsy data varied widely, in large part due to the open-ended nature of the necropsy submission form. Unfortunately, the variability of information submitted and protocols employed during the study period limited the comparisons that could be made regarding anesthetic drugs administered, doses, and relationship to sex, age, weight, time to arrest, etc. Towards the end of the study, a standard list of information, useful from clinical, anesthesiologic, and pathologic perspectives in cases of AAD, was developed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recommended submission information for cases of AAD. The type of arrest can be essential in establishing the mechanism and cause of death. 3 The percentage of oxygen in the lungs at the time of death can have a profound impact upon the gross appearance at the time of necropsy and affect interpretation (artifact or true lesion). Similarly, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) efforts, including drug administration, may result in post-mortem artifacts.

| Recommended submission information for cases of AAD | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Signalment | Time arrest was noted |

| Presenting complaint | Type of arrest: respiratory or cardiopulmonary |

| ASA Physical Status Scale category/significant physical exam findings (based on information available prior to anesthesia) | Oxygen content inspired/delivered at time of death (room air, 100% O2, etc) |

| Purpose of anesthesia/sedation (exam, surgery, other procedure, etc) | CPR attempted (Y/N) |

| Pre-anesthetic medications: drugs, doses, routes, and times given | CPR drugs/reversal agents administered (dose and route) |

| Induction drugs: drugs, doses, routes, and times given | Oxygen content delivered during CPR (room air, 100% O2, etc) |

| Maintenance drugs: list drugs, doses, routes, and times given | Duration of CPR |

| Endotracheal intubation (Y/N) | Body handling since time of death (refrigeration, freezing, thawing, etc) |

Also, although AAD was defined as death within 24 h of receiving anesthesia, postoperative monitoring of all cats for a full 24 h could not be guaranteed, even though it is recommended by the HQHVSNOs to caretakers that cats be monitored for 48 h postoperatively prior to release. Both HQHVSNOs have phone numbers available to call if caretakers had questions or problems, however. Therefore, cats that died or were euthanased within 24 h were likely completely reported.

Finally, variation among pathologists is always a concern in retrospective pathology studies. In this study, differences were minimized by strict adherence to the necropsy protocol and collection of a complete, standardized set of tissues, although the tissues examined histologically varied among pathologists and cases handled by the same pathologist. While having all necropsies performed by an individual pathologist may decrease variability, review by multiple pathologists decreases the risk of a systematic bias in interpretation.

Conclusion

We hope that this is the first in a series of studies of the lesions and diseases that contribute to AADs in cats, as well as other veterinary species. It is important for clinicians to be aware of the utility of the necropsy in AAD investigation, both as a means to discover more information on an individual case-basis, and as a contribution to the effort to make anesthesia safer for all veterinary species.

Acknowledgements

Funding for post-mortem investigations was provided in part by a grant from Pfizer Animal Health. Pfizer Animal Health had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Sharma BR. Death during or following surgical procedure and the allegation of medical negligence: an overview. J Forensic Leg Med 2007; 14: 311–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward RJ, Reay DT. Anesthetic death investigation. Leg Med 1989: 39–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lienhart A, Auroy Y, Pequignot F, et al. Survey of anesthesia-related mortality in France. Anesthesiology 2006; 105: 1087–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodbelt DC, Pfeiffer DU, Young LE, Wood JL. Risk factors for anaesthetic-related death in cats: results from the confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities (CEPSAF). Br J Anaesth 2007; 99: 617–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Start RD, Cross SS. Acp Best practice no 155. Pathological investigation of deaths following surgery, anaesthesia, and medical procedures. J Clin Pathol 1999; 52: 640–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li G, Warner M, Lang BH, Huang L, Sun LS. Epidemiology of anesthesia-related mortality in the United States, 1999–2005. Anesthesiology 2009; 110: 759–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyson DH, Maxie MG, Schnurr D. Morbidity and mortality associated with anesthetic management in small animal veterinary practice in Ontario. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1998; 34: 325–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott KC, Levy JK, Crawford PC. Characteristics of free-roaming cats evaluated in a trap-neuter-return program. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002; 221: 1136–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodbelt MA. Feline anesthetic deaths in veterinary practice. Top Companion Anim Med 2010; 25: 189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Looney AL, Bohling MW, Bushby PA, Howe LM, Griffin B, Levy JK. The Association of Shelter Veterinarians veterinary medical care guidelines for spayeneuter programs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008; 233: 74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King. The necropsy book. 5th edn. Ithaca, NY: Charles Louis Davis Foundation, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Peterson ME, Fox PR. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and hypertension in the cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1984; 185: 52–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payo-Puente P, Botelho-Dinis M, Carvaja Uruena AM, Payo-Puente M, Gonzalo-Orden JM, Rojo-Vazquez FA. Prevalence study of the lungworm Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in stray cats of Portugal. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 242–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabarevic. Incidence and regional distribution of the lungworm Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in cats in Croatia. Veterinarski Arhiv 1999; 69: 279–87. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockdale PH. The pathogenesis of the lesions elicited by Aelurostrongylus abstrusus during its prepatent period. Pathol Vet 1970; 7: 102–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton JM. Studies on re-infestation of the cat with Aelurostrongylus abstrusus. J Comp Pathol 1968; 78: 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacorcia L, Gasser RB, Anderson GA, Beveridge I. Comparison of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid examination and other diagnostic techniques with the Baermann technique for detection of naturally occurring Aelurostrongylus abstrusus infection in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2009; 235: 43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Headley. Aelurostrongylus abstrusus induced pneumonia in cats: pathological and epidemiological findings of 38 cases. Semina: Cieênc Agrár 1996; 26: 373–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naylor JR, Hamilton JM, Weatherley AJ. Changes in the ultrastructure of feline pulmonary arteries following infection with the lungworm Aelurostrongylus abstrusus. Br Vet J 1984; 140: 181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rawlings CA. Pulmonary arteriography and hemodynamics during feline heartworm disease. Effect of aspirin. J Vet Intern Med 1990; 4: 285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaise G, Langleben D, Hubert B. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: pathophysiology and anesthetic approach. Anesthesiology 2003; 99: 1415–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]