Abstract

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification is a prevalent RNA epigenetic modification, which plays a crucial role in tumor progression including metastasis. Isothiocyanates (ITCs) are natural compounds and inhibit the tumorigenesis of various cancers. Our previous studies show that ITCs inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, and have synergistic effects with chemotherapy drugs. In this study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effects of ITCs on cancer cell metastasis. We showed that phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC) dose-dependently inhibited the cell viability of both NSCLC cell lines H1299 and H226 with IC50 values of 17.6 and 15.2 μM, respectively. Furthermore, PEITC dose-dependently inhibited the invasion and migration of H1299 and H226 cells. We demonstrated that PEITC treatment dose-dependently increased m6A methylation levels and inhibited the expression of the m6A demethylase fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) in H1299 and H226 cells. Knockdown of FTO significantly increased m6A methylation in H1299 and H226 cells, impaired their abilities of invasion and migration in vitro, and enhanced the inhibition of PEITC on tumor growth in vivo. Overexpression of FTO promoted the migration of NSCLC cells, and also mitigated the inhibitory effect of PEITC on migration of NSCLC cells. Furthermore, we found that FTO regulated the mRNA m6A modification of a transcriptional co-repressor Transducin-Like Enhancer of split-1 (TLE1) and further affected its stability and expression. TCGA database analysis revealed TLE1 was upregulated in NSCLC tissues compared to normal tissues, which might be correlated with the metastasis status. Moreover, we showed that PEITC suppressed the migration of NSCLC cells by inhibiting TLE1 expression and downstream Akt/NF-κB pathway. This study reveals a novel mechanism underlying ITC’s inhibitory effect on metastasis of lung cancer cells, and provided valuable information for developing new therapeutics for lung cancer by targeting m6A methylation.

Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, metastasis, phenethyl isothiocyanate, m6A methylation, FTO, TLE1

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. It caused 1.8 million deaths in 2020, accounting for 18.0% of all cancer-related deaths [1]. NSCLC accounts for ~85% of all lung cancer cases, and it can be further subdivided into adenocarcinoma (LUAD), squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) and large-cell carcinoma by histological type. Surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy are the major clinical treatment strategies for lung cancer and have achieved great progress in recent years. However, the 5-year survival rate is still only ~15% [2]. The metastasis of cancer cells is responsible for ~90% of lung cancer-related deaths [3]. Studies on the underlying mechanisms of lung cancer metastasis and the development of targeted therapy strategies are urgently needed.

Posttranscriptional modifications of RNA have been proven to play critical roles in diverse physiological and pathological processes. Among more than 100 identified modifications in RNA, m6A is the most prevalent and abundant in eukaryotic cells [4, 5]. RNA m6A methylation mainly occurs within the “RRACH” consensus sequence (R = A or G, H = A, C, or U), which is enriched in the stop codon, 3′ untranslated region (UTR) and long internal exon [6, 7]. Similar to DNA methylation, RNA m6A methylation regulates the posttranscriptional expression of genes without changing the base sequences. It can participate in the regulation of almost all steps in the RNA life cycle, including splicing, translocation, stability, decay and translation [8, 9]. As a dynamic and reversible process, RNA m6A methylation is regulated by two groups of catalytic proteins in the nucleus: methyltransferases (‘writers’) and demethylases (‘erasers’) [10, 11]. A group of m6A binding proteins (“readers”) subsequently recognize and bind to the m6A-rich domain in RNA and exert corresponding downstream functional effects.

Studies have revealed that aberrant RNA m6A methylation is associated with the tumorigenesis and progression of cancer [12, 13]. The dysregulation of m6A writers, erasers and readers regulates these processes by activating oncogenes or inhibiting tumor suppressors. Methyltransferase-like protein 3 (METTL3) is the first identified component of the methyltransferase complex and serves as the major methyltransferase critical for m6A methylation. It has been proven to be a tumor-promoting gene in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), liver cancer and LUAD and acts by enhancing the translation of oncogenes such as c-Myc, PTEN and Snail [14, 15]. There are two identified m6A erasers, FTO and AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5). FTO has been proven to be an oncogenic factor in AML [16]. In cervical cancer, the level of FTO is elevated and enhances chemo- and radio-resistance by regulating the expression of β-catenin [17]. M6A methylation also plays important roles in lung cancer [18]. FTO is identified as a prognostic factor in LUSC. It facilitates LUSC cell proliferation and tumor development by decreasing the m6A levels of myeloid zinc finger 1 (MZF1) mRNA and enhancing its stability [19]. In addition, Li et al. revealed that FTO promotes the proliferation and colony formation of NSCLC cells by improving ubiquitin-specific peptidase 7 (USP7) mRNA stability and expression [20]. Although recent studies suggest that m6A modification regulates the progression of lung cancer, the underlying mechanism is not fully understood.

ITCs are natural compounds abundant in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli and watercress. Studies have shown that ITCs, including allyl isothiocyanate (AITC), sulforaphane (SFN), benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC) and phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC), could reduce the risk of cancer occurrence and inhibit the growth of various types of cancer cells by inducing oxidative stress, apoptosis and cell cycle arrest and inhibiting angiogenesis [21, 22]. Our previous studies have revealed that ITCs inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of NSCLC cells and have synergistic effects with chemotherapy drugs [23–26]. However, the inhibitory effects of ITCs on cancer cell metastasis and the related mechanisms still need to be elucidated.

In this study, we found that PEITC inhibited the invasion and migration of NSCLC cells through FTO-mediated m6A methylation, and TLE1 was identified as the target gene methylated by FTO. A mechanistic study revealed that PEITC decreased TLE1 expression through FTO-mediated m6A modification of TLE1 mRNA and further suppressed the downstream Akt/NF-κB pathway.

Materials and methods

Reagents

PEITC was purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). The Akt inhibitor perifosine and the NF-κB inhibitor JSH-23 were purchased from Topscience (Shanghai, China). Actinomycin D was purchased from MedChemExpress (Shanghai, China). Antibodies against FTO (#31687), METTL3 (#86132), Vimentin (#5741), MMP2 (#40994), Akt (#9272), p-Akt (#9271), p65 (#8242) and β-actin (#3700) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA); antibodies against N-cadherin (#WL01047), Twist (#WL00997), MMP9 (#WL03096) and p-p65 (#WL02169) were purchased from Wanleibio (Shenyang, China); the antibody against TLE1 (K008695P) was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China); the antibody against ALKBH5 (#ab69325) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); and the antibody against m6A (#202003) was purchased from Synaptic Systems (Goettingen, Germany). Secondary antibodies coupled to HRP were purchased from ZSGB-BIO (Beijing, China). Cell culture medium and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Life Technologies (Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell culture

The human NSCLC cell lines NCI-H1299 and NCI-H226 were purchased from Cell Bank, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. All cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Cell viability assay

NSCLC cells were seeded at an initial density of 6 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plates and incubated with 0–50 μM PEITC for 48 h at 37 °C. A stock solution of PEITC (100 mM) was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted in a cell culture medium. DMSO was used as the vehicle control. Cell viability was determined by the Cell Counting Kit-8 kit (MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (La Jolla, CA, USA).

Cell migration assay

The migration ability of NSCLC cells was assessed by a wound healing experiment as described previously [27]. Briefly, NSCLC cells were plated and cultured in 6-well plates until they formed an 80% confluent monolayer. Then, the cells were scratched with sterile pipette tips and treated with PEITC. Pictures were taken by microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) at ×40 magnification at 0 h, 24 h and 48 h after scratching, and cell migration ability was assessed by the wound closure rate: (1-final wound area/initial wound area) ×100%.

Cell invasion assay

The invasion ability of NSCLC cells was assessed by the Transwell assay as described previously [28]. Briefly, the Transwells were inserted into a 24-well plate, and the upper chamber was coated with 40 μL of serum-free medium diluted Matrigel (1:5) (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, cells (5×104) were suspended in 100 μL serum-free medium and seeded into the upper chamber. 700 μL of culture medium was added to the lower chamber. After 48 h of incubation, invaded cells into the lower chamber were fixed and stained with 1% crystal violet and counted from 5 random fields under a microscope at 200× magnification.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously [26]. Briefly, cells were treated with RIPA buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) containing protease inhibitors. The cell lysates were separated by SDS‒PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Pall, New York, NY, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in 0.5% Tween 20-TBS for 1 h at room temperature and then probed with the indicated antibodies at a 1:1000 dilution overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the membranes were probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody at a 1:5000 dilution for 1 h. The blots were developed with chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and captured by a G:BOX iChemi XT system (Syngene, Cambridge, UK).

RNA isolation, reverse transcription and quantitative PCR assay

Total RNA was extracted from cell samples or tumor tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Reverse transcription was performed by using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TAKARA, Dalian, China). Real-time PCR was performed by using Power SYBR-Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) on an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detector. GAPDH served as an endogenous control for normalization. Primers of genes were as follows: FTO forward: 5ʹ-GACTCTCATCTCGAAGGCAG-3ʹ and reverse: 5ʹ-CCAAGGTTCCTGTTGAGCAC-3ʹ; METTL3 forward: 5ʹ-CAAGGAGGAGTGCATGAAAG-3ʹ and reverse: 5ʹ-GGCTTGGCGTGTGGTCTTTG-3ʹ; ALKBH5 forward: 5ʹ-GTTCCAGTTCAAGCCTATTC-3ʹ and reverse: 5ʹ- GGTCCCTGTTGTTTCCTGAC-3ʹ; TLE1 forward: 5ʹ-CATGCTCGCCAGATCAACACC-3ʹ and reverse: 5ʹ-CACTATGAGAGTGCAGCCATC-3ʹ; GAPDH forward: 5ʹ-CCACCCATGGCAAATTCC-3ʹ and reverse: 5ʹ- GATGGGATTTCCATTGATGACA-3ʹ.

RNA m6A methylation dot blot assay

RNA (250 ng) was denatured at 65 °C for 5 min and spotted onto an N+ nylon membrane (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). The spotted membranes were crosslinked in a UV chamber (CL-1000 Ultraviolet Crosslinker) at 1200×100 μJ/cm2 for 10 min, blocked with 5% skim milk in 0.1% Tween 20-TBS for 1 h and incubated with anti-m6A antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h, and dot blots were developed with Chemilum HRP substrate. Parallel spotted membranes were stained with 0.02% methylene blue (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) in 0.3 M sodium acetate and used as loading controls.

RNA m6A methylation assay

RNA m6A methylation was detected with the EpiQuik m6A RNA methylation quantification kit (EpiGentek, Farmingdale, NY) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 200 ng RNA was added to assay wells with binding buffer and incubated for 90 min at 37 °C. After incubation with the capturing antibody and detecting antibody sequentially, the development solution was added for 10 min, and then the stop solution was added. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured, and the levels of RNA m6A methylation were calculated according to the standard curve.

RNA interference and plasmid transfection

siRNA duplex mixtures (three pairs for each gene) or expression plasmids of the target gene were transfected into NSCLC cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 48 h, cell lysates were harvested for Western blot analysis. The siRNA duplex sequences for FTO were as follows: siFTO-1: sense: 5’-GGCAAUCGAUACAGAAAGUTT-3’, anti-sense: 5’-ACUUUCUGUAUCGAUUGCCTT-3’; siFTO-2: sense: 5’-ACACUUGGCUCCCUUAUCUTT-3’, anti-sense: 5’-AGAUAAUUUAUCCAAGUGUTT-3’; siFTO-3: sense: 5’-GUGGCAGUGUACAGUUAUATT-3’; anti-sense: 5’-UAUAACUGUACACUGCCACTT-3’. Those for TLE1 were siTLE1-1: sense: 5’-GAAGGCUACAGUCUAUGAATT-3’, anti-sense: 5’-UUCAUAGACUGUAGCCUUCTT-3’; siTLE1-2: sense: 5’-CAGCCUUAAAUUGGAAUGUTT-3’, anti-sense: 5’-ACAUUCCAAUUUAAGGCUGTT-3’; siTLE1-3: sense: 5’-CAGCCACUAUGACAGUGAUTT-3’, anti-sense: 5’-AUCACUGUCAUAGUGGCUGTT-3’. The negative control duplexes were as follows: sense: 5’-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3’, anti-sense: 5’-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3’. All siRNA duplexes were synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The expression plasmids of FTO and TLE1 were purchased from the Public Protein/Plasmid Library (Nanjing, China).

Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP-seq)

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent from H1299 cells treated with 30 μM PEITC for 48 h and purified using an RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA fragmentation, library preparation and MeRIP-seq were conducted by LC-Bio Technology (Hangzhou, China).

Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation quantitative PCR (MeRIP-qPCR)

Briefly, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent. Magnetic beads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were incubated with anti-m6A antibody or rabbit IgG at 4 °C for 2 h. After washing, the antibody-conjugated beads were mixed with RNA samples in binding buffer containing RNase inhibitors for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the m6A IP RNAs were eluted and recovered by ethanol precipitation. The m6A RNA samples were assessed by RT‒PCR, and the enrichment was calculated via normalization of the input.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

RIP assays were performed using the Magna RIP RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation kit (Millipore, St. Louis, MO). Briefly, cell samples were treated with lysis buffer containing protease and RNase inhibitors. The lysate (10%) was left as input, and the remaining 90% was incubated with anti-FTO antibody or rabbit IgG-coated magnetic beads overnight at 4 °C. After elution and proteinase K digestion for 2 h at 50 °C, the immunoprecipitated RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent and assessed by RT-PCR. The IP enrichment was calculated as the ratio of the amount of a transcript in the IP sample to that in the input.

RNA stability assay

To measure the RNA stability of TLE1 in NSCLC cells, actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) was added to the cells after FTO siRNA or plasmid transfection. Cells were collected after 4 h and 8 h of incubation. RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent and assessed by RT‒PCR. GAPDH was used for normalization.

Mouse xenograft model

Five-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the Cancer Institute of the Chinese Academy of Medical Science (Beijing, China). Mice were randomly divided into two groups (eight mice per group), and 3×106 H1299 or H1299-LV-FTO-KD cells were injected subcutaneously into the flank of each mouse. For each group, four mice were treated with PEITC (100 mg/kg) intraperitoneally every two days for 14 days beginning the fifth week after cell injection, while the other four mice were treated with PBS as a control. At the end of the experiment, mice were euthanized, and tumor tissues were dissected for further analysis. Tumor weights were measured, and volumes were calculated (V = D/2 × d2, V: volume; D: longitudinal diameter; d: latitudinal diameter). Mouse xenograft experiments were approved by the Tianjin Medical University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

All data were obtained from more than three independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Student’s t test was used to assess the differences between two groups, and one-way ANOVA was used to conduct statistical comparisons among different groups. A P value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

PEITC inhibited the growth, invasion and migration of NSCLC cells

To investigate the effects of PEITC on the growth, invasion and migration of NSCLC cells, two lung cancer cell lines were used: NCI-H1299 (adenocarcinoma) and NCI-H226 (squamous cell carcinoma). The cells were treated with 5–50 μM PEITC for 48 h, and cell viability was assessed by a CCK-8 kit. As shown in Fig. 1a, there was dose-dependent inhibition of the growth of both NSCLC cell lines. The IC50 values were 17.6 μM for H1299 and 15.2 μM for H226. The metastatic potential of cancer cells depends on their invasion and migration abilities. To investigate the effects of PEITC on the invasion and migration of NSCLC cells, wound healing and Transwell assays were performed. As illustrated in Fig. 1b, PEITC inhibited the migration of both NSCLC cell lines, and the wound closure rate decreased significantly after PEITC treatment compared with the control. Similar inhibitory effects were observed in the Transwell assay (Fig. 1c). Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a cellular program that is crucial in the metastasis and malignant progression of cancer cells. Then, the expression levels of EMT-related proteins after PEITC treatment were analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 1d). The results indicated that PEITC decreased the expression levels of N-cadherin, MMP2, MMP9, Vimentin and Twist in both NSCLC cell lines in a dose-dependent manner. Taken together, these results demonstrated that PEITC inhibits the growth, invasion and migration of NSCLC cells.

Fig. 1. PEITC inhibited the growth, invasion and migration of NSCLC cells.

a NSCLC cells H1299 and H226 were treated with 0–50 μM PEITC for 48 h, the cell viability was detected by CCK-8 assay. b Wound healing of NSCLC cells treated with or without PEITC for 24 h was recorded (40× magnification) and quantitatively analyzed. c Transwell assay of NSCLC cells treated with or without PEITC was recorded (200× magnification) and quantitatively analyzed. d The expressions of EMT-related genes: N-Cadharin, Vimentin, Twist, MMP2 and MMP9 were measured by Western blotting. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

PEITC increased the RNA m6A modification level in NSCLC cells

Accumulating evidences demonstrate that dysregulated RNA m6A modification is involved in tumor development. However, the effects of antitumor drugs on m6A modification in cancer cells have rarely been studied. To determine the effects of PEITC on RNA m6A modification in NSCLC cells, H1299 and H226 cells were treated with PEITC, and the level of m6A modification was detected. As shown in Fig. 2a, PEITC treatment elevated the m6A modification levels in both cell lines. Similar effects were also observed in the results of the RNA m6A methylation quantification kit assay (Fig. 2b). The MeRIP-seq data also indicated that there was an elevation of RNA m6A methylation levels in NSCLC cells after PEITC treatment (Fig. 2c). As illustrated in Fig. 2d, compared with that in the control group, the level of m6A modification in the mRNA of PEITC-treated cells was increased in both the 5’UTR and 3’UTR. In addition, m6A peaks were especially abundant in the vicinity of start and stop codons.

Fig. 2. PEITC elevated the RNA m6A modification level and inhibited the expression of FTO in NSCLC cells.

a The RNA m6A methylation level in NSCLC cells treated with or without PEITC was detected by dot blot assay and quantitatively analyzed. Methylene blue staining served as a loading control. b The RNA m6A methylation level was detected by RNA m6A Methylation Quantification Kit. c The cumulative distribution function curve of H1299 treated with or without PEITC samples in MeRIP-seq. d Density distribution of m6A peaks in 5′UTR (5′ untranslated region), CDS (coding region) and 3′UTR (3′ untranslated region) across mRNA transcripts. e The transcription level of m6A methyltransferase METTL3, demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 were measured by RT-PCR. f The expression levels of FTO, METTL3 and ALKBH5 were measured by Western blotting. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

RNA m6A modification is dynamically regulated by specific methyltransferases and demethylases. To explore m6A regulators participating in the modulatory effects of PEITC, the levels of methyltransferase METTL3, demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 were detected by RT-PCR and Western blotting. As shown in Figs. 2e, f, the transcript and expression levels of FTO significantly decreased after PEITC treatment; however, there were no consistent effects of PEITC on METTL3 and ALKBH5. Collectively, these results indicated that PEITC elevated the m6A modification level in NSCLC cells, and this effect might be mediated by FTO suppression.

FTO mediated the effect of PEITC on m6A modifications and the invasion and migration of NSCLC cells

To explore the role of FTO in the m6A modification of NSCLC cells, FTO was knocked down or overexpressed by transfecting an FTO-specific siRNA mixture or expression plasmid (Fig. 3a). The m6A methylation dot blot assay illustrated that in both H1299 and H226 cells, the m6A level increased when FTO was knocked down (Fig. 3b) and decreased when FTO was overexpressed (Fig. 3c). To further investigate the role of FTO in the effect of PEITC on m6A modification, NSCLC cells were transfected with the FTO overexpression plasmid and treated with PEITC. Dot blot assays showed that the elevation of m6A modification levels in NSCLC cells after PEITC treatment was attenuated when FTO was overexpressed (Fig. 3d). These results indicated that FTO mediates the effect of PEITC on m6A modification in NSCLC cells.

Fig. 3. FTO mediated the effect of PEITC on the m6A modifications, invasion and migration of NSCLC cells.

a NSCLC cells were transfected with FTO-specific siRNA duplex mixtures or expression plasmid, FTO expression was detected by Western blotting. b, c RNA m6A methylation levels after FTO overexpression or knockdown were detected by dot blot assay and quantitatively analyzed. Methylene blue staining served as a loading control. d RNA m6A methylation levels in FTO overexpressed NSCLC cells treated with or without PEITC were detected by dot blot assay and quantitatively analyzed. Methylene blue staining served as a loading control. e Wound healing of NSCLC cells with or without FTO knockdown was recorded (40× magnification) and quantitatively analyzed. f Transwell assay of NSCLC cells with or without FTO knockdown was recorded (200× magnification) and quantitatively analyzed. g The expression levels of EMT related genes in NSCLC cells after FTO knockdown or overexpression were measured by Western blotting. h Wound healing of FTO overexpressed NSCLC cells treated with or without PEITC was recorded (40× magnification) and quantitatively analyzed. i The expressions levels of EMT related genes in FTO overexpressed NSCLC cells treated with or without PEITC were measured by Western blotting. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

To determine the function of FTO in the invasion and migration of NSCLC cells, wound healing and Transwell assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 3e, the migration of both NSCLC cell lines was suppressed after FTO knockdown, and the wound closure rate decreased significantly compared with that in the control group. Similar inhibitory effects were also observed in the Transwell assay (Fig. 3f). Western blotting results showed that the EMT-related proteins N-cadherin, MMP2, MMP9, Vimentin and Twist decreased when FTO was knocked down but increased when FTO was overexpressed in both NSCLC cell lines (Fig. 3g). Furthermore, FTO was overexpressed in NSCLC cells before treatment with PEITC. The wound healing assay and Western blot results showed that FTO overexpression mitigated the inhibitory effect of PEITC on migration and EMT-related gene expression (Fig. 3h, i). These results suggested that FTO mediates the effect of PEITC on m6A modification and the invasion and migration of NSCLC cells.

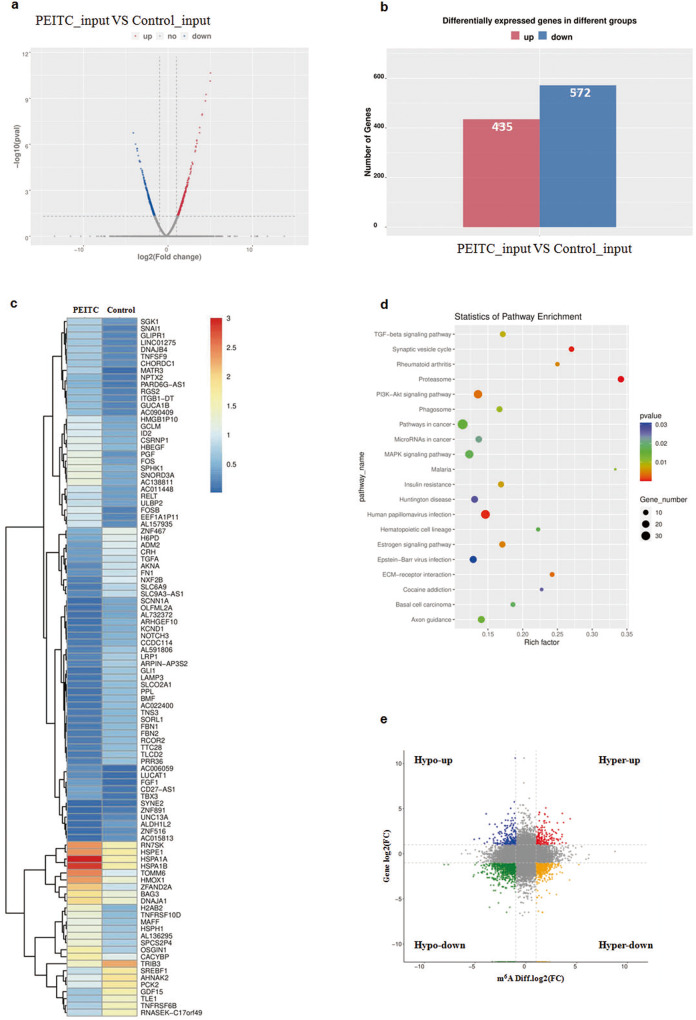

PEITC increased the m6A modification level of TLE1 and decreased its expression

PEITC increased m6A modification in NSCLC cells, and this finding drove us to further identify which gene is modified via m6A modification. RNA-seq and MeRIP-seq of H1299 cells with or without PEITC treatment were performed first. RNA-seq analysis revealed that the expression of many genes was changed after PEITC treatment (Fig. 4a). In total, 572 genes were down-regulated and 435 genes were upregulated in the PEITC-treated sample compared with the control sample (Fig. 4b). The genes significantly changed by PEITC are listed in Fig. 4c. KEGG analysis showed that these genes were enriched in pathways including the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, proteasome and pathways in cancer (Fig. 4d). In addition, the genes that changed at both the mRNA level and m6A level were analyzed by combining the MeRIP-seq and RNA-seq data. Compared to the control, four groups of significantly changed genes were screened according to the changes in m6A modification level (hyper, hypo) and mRNA level (up, down) (Fig. 4e). There were 33 “hyper-down” genes, 33 “hyper-up” genes, 13 “hypo-up” genes, and 81 “hypo-down” genes.

Fig. 4. PEITC regulated m6A modification and expression of genes.

a Volcano plot of mRNA levels detected by MeRIP-seq. b Differentially expressed genes after PEITC treatment were detected by RNA-seq. c Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes. d KEGG pathway analysis. e Distribution graph of genes significantly changed in mRNA level and m6A level after PEITC treatment.

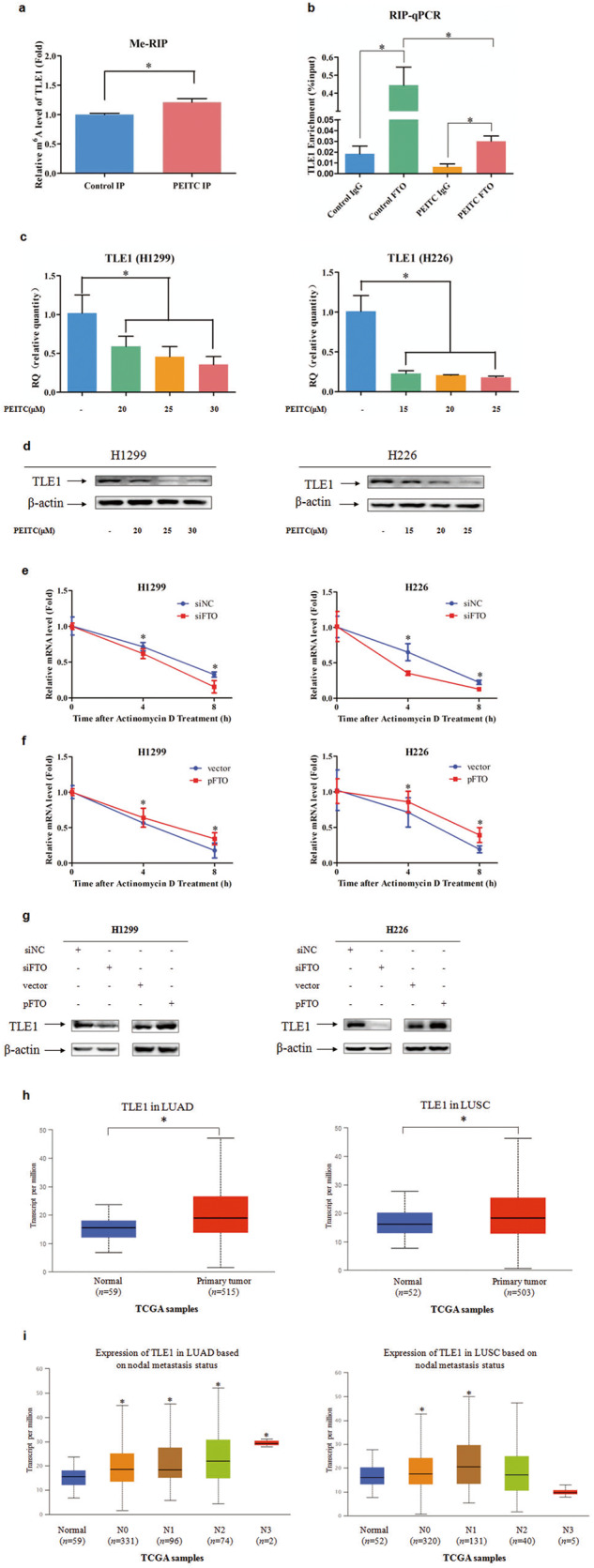

Then, genes in the “hyper-down” group, which were also reported to be involved in cancer cell growth, invasion or migration, were screened. After preliminary verifications and functional analysis, TLE1 was identified. The m6A modification level of TLE1 in NSCLC cells was detected by MeRIP-qPCR assay. As shown in Fig. 5a, the m6A modification level of TLE1 was increased in PEITC-treated cells, which was consistent with the sequencing results. To assess the direct interaction between FTO and the TLE1 transcript, RIP qPCR assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 5b, compared with the control antibody IgG, the FTO-specific antibody enriched TLE1 mRNA significantly, while after PEITC treatment, the enrichment was markedly decreased. The RT-PCR and Western blotting results showed that the transcript and expression of TLE1 in NSCLC cells were decreased after PEITC treatment (Fig. 5c, d). Then, the effect of FTO on the stability of TLE1 mRNA was also investigated by using the RNA synthesis inhibitor actinomycin D. As shown in Fig. 5e, f, FTO knockdown accelerated the decay of TLE1 mRNA, whereas FTO overexpression had the opposite effects. In addition, knockdown of FTO reduced the expression of TLE1, while overexpression of FTO increased the expression of TLE1 (Fig. 5g). Furthermore, the clinical significance of TLE1 in lung cancer was evaluated by using the TCGA database. As illustrated in Fig. 5h, the expression of TLE1 was significantly upregulated in both LUAD and LUSC tissues compared to normal tissues. In addition, the expression level of TLE1 was significantly increased in all stages of LUAD and in stages N0 and N1 but not N2 and N3 in LUSC. These results indicated that TLE1 expression may correlate with the clinical metastasis status of NSCLC (Fig. 5i).

Fig. 5. PEITC regulated m6A modification and expression of TLE1.

a The m6A methylation levels of TLE1 mRNA in H1299 treated with or without PEITC were detected by MeRIP-qPCR. b RIP-qPCR assay of TLE1 enrichment by FTO. c, d The transcription and expression levels of TLE1 in NSCLC cells treated with or without PEITC were detected by RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively. e, f FTO knockdown or overexpressed NSCLC cells were treated with Actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) for 4 and 8 h, the stability of TLE1 mRNA was detected by RT-PCR. g The expression level of TLE1 in FTO knockdown or overexpressed NSCLC cells was detected by Western blotting. h TLE1 expression levels in LUAD and LUSC patients in the TCGA dataset. i Correlation between TLE1 expression levels and metastasis status. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. Columns, mean; bars, SD. *P < 0.05.

Taken together, these data demonstrated that PEITC increased the m6A modification level and inhibited the expression of TLE1 in NSCLC cells. FTO mediates this effect by binding to TLE1 mRNA and regulating its stability.

PEITC inhibited the migration of NSCLC cells via the TLE1-mediated Akt/NF-κB pathway

TLE1 was reported to be involved in tumorigenesis. Further studies were conducted to investigate the roles of TLE1 in the migration of NSCLC cells. As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the wound healing assay showed that TLE1 overexpression promoted migration, while TLE1 knockdown inhibited this ability of NSCLC cells. Similar effects were also observed in the Transwell assay (Fig. 6b). Western blot analysis showed that EMT-related proteins decreased after TLE1 knockdown but increased when TLE1 was overexpressed in both NSCLC cell lines (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6. PEITC inhibited the migration of NSCLC cells via TLE1 mediated Akt/NF-κB pathway.

a Wound healing of TLE1 knockdown or overexpressed NSCLC cells were recorded (40× magnification) and quantitatively analyzed. b Transwell assay of TLE1 knockdown or overexpressed NSCLC cells were recorded (200× magnification) and quantitatively analyzed. c The expression levels of TLE1 and EMT related genes in TLE1 knockdown or overexpressed NSCLC cells were detected by Western blotting. d The levels of Akt/NF-κB pathway related proteins: p-Akt, Akt, p-p65 and p65 in NSCLC cells treated with or without PEITC were detected by Western blotting. e The levels of Akt/NF-κB pathway related proteins in TLE1 knockdown or overexpressed NSCLC cells were detected by Western blotting. f The levels of Akt/NF-κB pathway-related proteins in TLE1 overexpressed NSCLC cells treated with or without PEITC were measured by Western blotting. g Wound healing of TLE1 overexpressed NSCLC cells treated with Akt inhibitor perifosine (10 μM) or NF-κB inhibitor JSH23 (14 μM) was recorded (40× magnification) and quantitatively analyzed. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

Studies have proven that the Akt and NF-κB pathways are responsible for cancer metastasis, and our KEGG analysis (Fig. 4d) also found that the Akt pathway was changed after PEITC treatment. To investigate the mechanism underlying the inhibitory effects of PEITC on NSCLC cells, the effects of PEITC on the Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway were further evaluated. As shown in Fig. 6d, PEITC decreased the levels of p-Akt and p-p65 in a dose-dependent manner without changing the levels of total Akt and p65. TLE1 overexpression activated the Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway, while TLE1 knockdown inhibited it (Fig. 6e). In addition, TLE overexpression mitigated the inhibitory effect of PEITC on the Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway (Fig. 6f). The Akt inhibitor perifosine and the NF-κB inhibitor JSH23 significantly abrogated the promoting effect of TLE1 on NSCLC cell migration (Fig. 6g). These data illustrated that PEITC inhibited the migration ability of NSCLC cells by inhibiting TLE1-mediated Akt/NF-κB pathway activation.

FTO knockdown enhanced the inhibitory effect of PEITC on NSCLC cell growth in vivo

To investigate the role of FTO in NSCLC cell growth in vivo, the FTO-knockdown stable cell line H1299-LV-FTO-KD was established by lentivirus infection (Fig. 7a). Wound healing and Transwell assays illustrated that the migration and invasion abilities of H1299-LV-FTO-KD cells were decreased compared with those of H1299 and H1299-LV-control cells (Fig. 7b, c).

Fig. 7. FTO knockdown enhanced the inhibitory effect of PEITC on NSCLC cell growth in vivo.

a The expression of FTO in the stable FTO-knockdown cell line H1299-LV-FTO-KD was detected by Western blotting. b Wound healing of H1299-LV-FTO-KD and control cells. c Transwell assay of H1299-LV-FTO-KD and control cells. d H1299 or H1299-LV-FTO-KD cells were transplanted subcutaneously into nude mice and further divided into four groups: H1299, H1299 + PEITC treatment, H1299-LV-FTO-KD and H1299-LV-FTO-KD + PEITC treatment. Since the fifth week after cell injection, PEITC (100 mg/kg) or PBS was injected intraperitoneally every two days for 14 days. The picture of mice was taken at the end of the experiment. e The picture of tumor tissues in each group. f The volumes and weights of excised tumor tissues in each group. g RNA m6A methylation levels in tumor tissues were detected by dot blot assay and quantitatively analyzed. h RNA m6A methylation levels in tumor samples were detected by RNA m6A Methylation Quantification Kit. i The expressions of FTO, TLE1, EMT and Akt/NF-κB pathway-related proteins in tumor samples were detected by Western blotting. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

A mouse xenograft model was used to evaluate the effects of PEITC and FTO knockdown on NSCLC cell growth in vivo. During the experiment, the body weights of control and PEITC-treated mice were not significantly different (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 7d–f, PEITC effectively inhibited tumor growth in vivo, and FTO knockdown also suppressed tumor growth. In addition, no tumors formed in the FTO knockdown with PEITC treatment group. The underlying mechanism was further investigated by analyzing tumor tissues. The results of dot blot and m6A RNA methylation quantification kit assays revealed that PEITC treatment significantly increased the m6A levels in tumor tissues, and FTO knockdown also elevated the m6A modification levels (Fig. 7g, h). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 7i, the levels of FTO, TLE1, EMT-related proteins, p-Akt and p-p65 were all decreased in tumor tissues of the PEITC treatment and FTO knockdown groups, which was consistent with the findings of the in vitro study. These results suggested that PEITC suppresses NSCLC tumor growth through FTO-mediated m6A modification of TLE1 and inhibition of the Akt/NF-κB pathway.

Discussion

Studies have shown that ITCs exert remarkable inhibitory effects on various types of cancer cells [26, 29, 30]. In addition to their significant anticarcinogenic effects as chemoprevention agents, ITCs exhibit low toxicity in clinical trials [31]. These advantages support the further development of ITCs as antitumor drugs for cancer prevention and treatment. Mechanistic research has illustrated that the antitumor activity of ITCs is due to the induction of apoptosis, reactive oxygen species (ROS), cell cycle arrest, interference with cell survival signaling pathways and EMT inhibition [32–34]. Our previous studies have revealed that ITCs decreases the metastatic potential of NSCLC cells [23]. However, the precise underlying mechanisms still need further elucidation. In this study, we found that PEITC inhibited the invasion and migration of NSCLC cells in a dose-dependent manner and revealed that these inhibitory effects were mediated by regulation of the expression of FTO and RNA m6A methylation. MeRIP-seq and functional studies further proved that TLE1 is a target gene of FTO that plays an important role in the effect of PEITC. Our results illustrated the effect and function of ITCs on RNA epigenetic modifications and provided valuable evidence for future development and application of ITCs in cancer treatment.

As a prevalent mRNA epigenetic modification, RNA m6A methylation has been proven to play critical roles in the tumorigenesis and progression of various types of human cancers. m6A modification regulators (“writers”, “erasers” and “readers”) are frequently aberrantly expressed in cancer cells and are involved in the regulation of processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, metastasis, and drug resistance; they act by regulating RNA processing and translation of certain genes. Numerous studies have reported the critical roles of dysregulated m6A methylation in lung cancer [18, 35]. Lin et al. found that the m6A writer METTL3 promotes the growth, survival and invasion of lung cancer cells by regulating the translation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and tafazzin (TAZ) [36]. Jin et al. reported that METTL3 promotes the translation of yes-associated protein (YAP) and further leads to drug resistance and metastasis in NSCLC [37]. Guo et al. revealed that elevated expression of the m6A eraser ALKBH5 leads to NSCLC progression by promoting the expression of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2C (UBE2C) [38]. The m6A reader YTHDF2 promotes lung cancer cell growth by facilitating the translation of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6-PGD) and enhancing the activity of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) [39]. In contrast, Ma et al. found that YTHDC2 inhibits lung adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis by suppressing cystine uptake and the SLC7A11-dependent antioxidant program [40]. As the first identified m6A eraser, FTO was reported to play important functions in various types of cancer, including AML, breast cancer, cervical cancer and renal cell carcinoma [41]. In lung cancer, FTO promotes the proliferation and invasion of lung cancer cells by increasing mRNA stability and enhancing the expression of myeloid zinc finger 1 (MZF1) and ubiquitin-specific peptidase 7 (USP7) [19, 20]. However, the in vivo role and molecular mechanism of m6A modification and FTO in the metastasis and antimetastatic effect of antitumor drugs on NSCLC cells have not been evaluated. In this study, we found that PEITC inhibited the invasion and migration of NSCLC cells through FTO-mediated m6A methylation. Overexpression of FTO mitigated the inhibitory effect of PEITC on invasion and migration. The in vivo study also demonstrated that FTO knockdown suppressed the growth of tumors and enhanced the inhibitory effect of PEITC on NSCLC cells. Our results described the roles of m6A methylation and FTO in lung cancer progression and the antimetastatic effect of PEITC and showed the possibility of developing diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for NSCLC by targeting m6A methylation and FTO.

TLE-1 is a member of the Groucho/TLE (Gro/TLE) family, which encodes transcriptional co-repressors. By binding to other transcription factors that bind to DNA, TLE1 affects the histone H3 framework and regulates gene expression [42, 43]. Studies have revealed that TLE1 plays roles in tumor progression [44]. Brunquell et al. found that TLE1 is overexpressed in invasive breast tumors and promotes the anoikis resistance and growth of breast carcinoma cells by inhibiting the Bit1 anoikis pathway [45]. Seo et al. reported that inhibition of TLE1 alters proliferation and apoptosis in synovial sarcoma by suppressing Bcl-2 expression [46]. In addition, TLE1 may act as a tumor suppressor. Zhang et al. reported that microRNA-657 promotes tumorigenesis by targeting TLE1 through NF-κB pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma [47]. In lung cancer, TLE1 is overexpressed and is a putative lung-specific oncogene that promotes cancer progression by regulating ErbB1/ErbB2 [48]. Yao et al. reported that TLE1 promotes EMT in lung adenocarcinoma cells through transcriptional repression of E-cadherin [49, 50]. However, whether TLE1 is regulated by m6A methylation and activates the Akt/NF-κB pathway in NSCLC cells has not been reported. In this study, we found that TLE1 is a target gene of FTO in NSCLC cells. PEITC treatment decreased the expression of TLE1 by regulating its mRNA m6A methylation and stability. The antimetastatic effect of PEITC on NSCLC cells is mediated by TLE1 and Akt/NF-κB pathway inhibition.

Accumulating evidences proved that m6A methylation regulators could serve as potential therapeutic targets of antitumor drugs. However, the development of m6A methylation inhibitors is still in the early stages. Several FTO inhibitors have been discovered and displayed inhibitory effects in various types of cancer [51]. The natural compound rhein inhibits the m6A demethylation activity of FTO by competitively binding to its catalytic domain [52]. Huang et al. reported that meclofenamic acid (MA) can selectively inhibit FTO by competitively binding to the surface of its active site [53]. R-2-hydroxyglutarate (R-2HG) and FB23-2 were found to inhibit FTO activity by directly binding to FTO and to exhibit antitumor activity in AML [54, 55]. In this study, we found that PEITC inhibited the expression of FTO and increased the RNA m6A methylation level in lung cancer. Although the mechanism underlying PEITC’s inhibitory effect on FTO needs further elucidation, our study provides a novel direction to identify effective drugs that could target dysregulated m6A methylation regulators in cancer and develop combination treatment strategies.

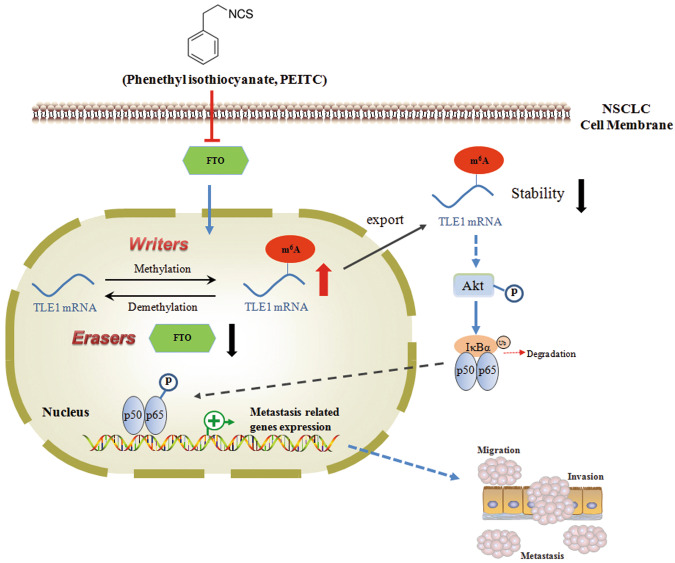

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that PEITC inhibits the metastatic potential of NSCLC cells via FTO-mediated m6A methylation. A mechanistic study revealed that PEITC decreases TLE1 expression through FTO-mediated m6A modification of TLE1 mRNA and further suppresses the downstream Akt/NF-κB pathway (Fig. 8). Our work revealed a novel mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of ITC on the metastasis of lung cancer cells and provided valuable information for developing an m6A modification-targeted strategy for lung cancer clinical treatment.

Fig. 8. A proposed model of PEITC’s regulation on m6A modification in NSCLC cells.

PEITC inhibits the metastatic potential of NSCLC cells via FTO-mediated m6A methylation. Mechanistic study showed that PEITC decreased TLE1 stability and expression though FTO-mediated m6A modification of TLE1 mRNA and further suppressed the downstream Akt/NF-κB pathway.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81372519), the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (22JCZDJC00450, 21JCQNJC00150), the Project of Health Commission of Tianjin (TJWJ2021MS006), the Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (TJYXZDXK-061B), the Project of Tianjin Municipal Education Commission (2020KJ150, 2021KJ212) and the Open Fund of Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology and Technology, Nankai University (NKU-KLMMTME-KFKT-202101).

Author contributions

KX, QCZ, LMC and YHR provided grant support. QCZ, YMQ, YHR, MMC, LMC, SJZ and BBL performed the experiments. MW and XW performed data analysis. KX and QCZ contributed to the study design and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Qi-cheng Zhang, Yong-mei Qian, Ying-hui Ren

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cataldo VD, Gibbons DL, Perez-Soler R, Quintas-Cardama A. Treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer with erlotinib or gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:947–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0807960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert AW, Pattabiraman DR, Weinberg RA. Emerging biological principles of metastasis. Cell. 2017;168:670–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia G, Fu Y, He C. Reversible RNA adenosine methylation in biological regulation. Trends Genet. 2013;29:108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue Y, Liu J, He C. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1343–55. doi: 10.1101/gad.262766.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149:1635–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Q, Gregory RI. RNAmod: an integrated system for the annotation of mRNA modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W548–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ke S, Pandya-Jones A, Saito Y, Fak JJ, Vagbo CB, Geula S, et al. m6A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Genes Dev. 2017;31:990–1006. doi: 10.1101/gad.301036.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai D, Wang H, Zhu L, Jin H, Wang X. N6-methyladenosine links RNA metabolism to cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:124. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0129-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batista PJ. The RNA modification N(6)-methyladenosine and its implications in human disease. Genom Proteom Bioinforma. 2017;15:154–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan Q, Liu PY, Haase J, Bell JL, Huttelmaier S, Liu T. The critical role of RNA m6A methylation in cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79:1285–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang T, Kong S, Tao M, Ju S. The potential role of RNA N6-methyladenosine in cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:88. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vu LP, Pickering BF, Cheng Y, Zaccara S, Nguyen D, Minuesa G, et al. The N(6)-methyladenosine (m6A)-forming enzyme METTL3 controls myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells. Nat Med. 2017;23:1369–76. doi: 10.1038/nm.4416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin X, Chai G, Wu Y, Li J, Chen F, Liu J, et al. RNA m6A methylation regulates the epithelial mesenchymal transition of cancer cells and translation of Snail. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2065. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Li Z, Weng H, Su R, Weng X, Zuo Z, Li C, et al. FTO plays an oncogenic role in acute myeloid leukemia as a N(6)-methyladenosine RNA demethylase. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:127–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou S, Bai ZL, Xia D, Zhao ZJ, Zhao R, Wang YY, et al. FTO regulates the chemo-radiotherapy resistance of cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) by targeting beta-catenin through mRNA demethylation. Mol Carcinog. 2018;57:590–7. doi: 10.1002/mc.22782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q, Xu K. The role of regulators of RNA m6A methylation in lung cancer. Genes Dis. 2022;10:495–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Liu J, Ren D, Du Z, Wang H, Zhang H, Jin Y. m6A demethylase FTO facilitates tumor progression in lung squamous cell carcinoma by regulating MZF1 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;502:456–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Han Y, Zhang H, Qian Z, Jia W, Gao Y, et al. The m6A demethylase FTO promotes the growth of lung cancer cells by regulating the m6A level of USP7 mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;512:479–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.03.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X, Zhou QH, Xu K. Are isothiocyanates potential anti-cancer drugs? Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30:501–12. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fofaria NM, Ranjan A, Kim SH, Srivastava SK. Mechanisms of the anticancer effects of isothiocyanates. Enzymes. 2015;37:111–37. doi: 10.1016/bs.enz.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu X, Zhu Y, Yan H, Liu B, Li Y, Zhou Q, et al. Isothiocyanates induce oxidative stress and suppress the metastasis potential of human non-small cell lung cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:269. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu BN, Yan HQ, Wu X, Pan ZH, Zhu Y, Meng ZW, et al. Apoptosis induced by benzyl isothiocyanate in gefitinib-resistant lung cancer cells is associated with Akt/MAPK pathways and generation of reactive oxygen species. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2013;66:81–92. doi: 10.1007/s12013-012-9456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Q, Chen M, Cao L, Ren Y, Guo X, Wu X, et al. Phenethyl isothiocyanate synergistically induces apoptosis with gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated degradation of Mcl-1. Mol Carcinog. 2020;59:590–603. doi: 10.1002/mc.23184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang QC, Pan ZH, Liu BN, Meng ZW, Wu X, Zhou QH, et al. Benzyl isothiocyanate induces protective autophagy in human lung cancer cells through an endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated mechanism. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:539–50. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao L, Ren Y, Guo X, Wang L, Zhang Q, Li X, et al. Downregulation of SETD7 promotes migration and invasion of lung cancer cells via JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2020;45:1616–26. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X, Song Q, Guo X, Wang L, Zhang Q, Cao L, et al. The metastasis potential promoting capacity of cancer-associated fibroblasts was attenuated by cisplatin via modulating KRT8. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:2711–23. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S246235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu K, Thornalley PJ. Studies on the mechanism of the inhibition of human leukaemia cell growth by dietary isothiocyanates and their cysteine adducts in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:221–31. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(00)00319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta P, Wright SE, Srivastava SK. PEITC treatment suppresses myeloid derived tumor suppressor cells to inhibit breast tumor growth. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e981449. doi: 10.4161/2162402X.2014.981449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD, Stephenson KK, Wade KL, et al. Safety, tolerance, and metabolism of broccoli sprout glucosinolates and isothiocyanates: a clinical phase I study. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:53–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5501_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta P, Wright SE, Kim SH, Srivastava SK. Phenethyl isothiocyanate: a comprehensive review of anti-cancer mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1846:405–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Huang H, Jin L, Lin S. Anticarcinogenic effects of isothiocyanates on hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:13834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Xiao J, Zhou N, Li Y, Xiao Y, Chen W, Ye J, et al. PEITC inhibits the invasion and migration of colorectal cancer cells by blocking TGF-beta-induced EMT. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;130:110743. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan H, Li X, Chen C, Fan Y, Zhou Q. Research advances of m6A RNA methylation in non-small cell lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2020;23:961–9. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2020.102.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin S, Choe J, Du P, Triboulet R, Gregory RI. The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2016;62:335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin D, Guo J, Wu Y, Du J, Yang L, Wang X, et al. m6A mRNA methylation initiated by METTL3 directly promotes YAP translation and increases YAP activity by regulating the MALAT1-miR-1914-3p-YAP axis to induce NSCLC drug resistance and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:135. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0830-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Guo J, Wu Y, Du J, Yang L, Chen W, Gong K, et al. Deregulation of UBE2C-mediated autophagy repression aggravates NSCLC progression. Oncogenesis. 2018;7:49. doi: 10.1038/s41389-018-0054-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheng H, Li Z, Su S, Sun W, Zhang X, Li L, et al. YTH domain family 2 promotes lung cancer cell growth by facilitating 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase mRNA translation. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:541–50. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgz152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma L, Chen T, Zhang X, Miao Y, Tian X, Yu K, et al. The m6A reader YTHDC2 inhibits lung adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis by suppressing SLC7A11-dependent antioxidant function. Redox Biol. 2021;38:101801. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He L, Li H, Wu A, Peng Y, Shu G, Yin G. Functions of N6-methyladenosine and its role in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:176. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jennings BH, Ish-Horowicz D. The Groucho/TLE/Grg family of transcriptional co-repressors. Genome Biol. 2008;9:205. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palaparti A, Baratz A, Stifani S. The Groucho/transducin-like enhancer of split transcriptional repressors interact with the genetically defined amino-terminal silencing domain of histone H3. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26604–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan D, Yang X, Yuan Z, Zhao Y, Guo J. TLE1 function and therapeutic potential in cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:15971–6. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunquell C, Biliran H, Jennings S, Ireland SK, Chen R, Ruoslahti E. TLE1 is an anoikis regulator and is downregulated by Bit1 in breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:1482–95. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seo SW, Lee H, Lee HI, Kim HS. The role of TLE1 in synovial sarcoma. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1131–6. doi: 10.1002/jor.21318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, Yang L, Liu X, Chen W, Chang L, Chen L, et al. MicroRNA-657 promotes tumorigenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting transducin-like enhancer protein 1 through nuclear factor kappa B pathways. Hepatology. 2013;57:1919–30. doi: 10.1002/hep.26162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allen T, van Tuyl M, Iyengar P, Jothy S, Post M, Tsao MS, et al. Grg1 acts as a lung-specific oncogene in a transgenic mouse model. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1294–301. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao X, Ireland SK, Pham T, Temple B, Chen R, Raj MH, et al. TLE1 promotes EMT in A549 lung cancer cells through suppression of E-cadherin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;455:277–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yao X, Pham T, Temple B, Gray S, Cannon C, Hardy C, et al. TLE1 inhibits anoikis and promotes tumorigenicity in human lung cancer cells through ZEB1-mediated E-cadherin repression. Oncotarget. 2017;8:72235–49. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niu Y, Wan A, Lin Z, Lu X, Wan GN. (6)-Methyladenosine modification: a novel pharmacological target for anti-cancer drug development. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8:833–43. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen B, Ye F, Yu L, Jia G, Huang X, Zhang X, et al. Development of cell-active N6-methyladenosine RNA demethylase FTO inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:17963–71. doi: 10.1021/ja3064149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang Y, Yan J, Li Q, Li J, Gong S, Zhou H, et al. Meclofenamic acid selectively inhibits FTO demethylation of m6A over ALKBH5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:373–84. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su R, Dong L, Li C, Nachtergaele S, Wunderlich M, Qing Y, et al. R-2HG exhibits anti-tumor activity by targeting FTO/m6A/MYC/CEBPA Signaling. Cell. 2018;172:90–105.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang Y, Su R, Sheng Y, Dong L, Dong Z, Xu H, et al. Small-molecule targeting of oncogenic FTO demethylase in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:677–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]