Abstract

Postpartum depression (PPD) is associated with decline in progesterone-derived anxiolytic-antidepressant neurosteroids after delivery. Neurosteroid replacement therapy (NRT) with GABA-A receptor-modulating allopregnanolone (brexanolone) shows promise as the first drug treatment for PPD. Here we describe the molecular insights of the neurosteroid approach for rapid relief of PPD symptoms compared to traditional antidepressants.

Keywords: Allopregnanolone, Brexanolone, Depression, GABA-A receptor, Neurosteroid, Tonic inhibition

Postpartum depression

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a major depressive disorder with onset during pregnancy or within 4 weeks of delivery. It affects about 20% of new mothers worldwide and is typified by depressed mood or anhedonia, insomnia, fatigue, anxiety, feelings of worthlessness, reduced concentration, and suicidal ideation. PPD can be devastating to the entire family and significantly impairs mother-infant attachment and infant wellbeing. PPD is frequently underdiagnosed due to lack of awareness, stigma, and limited remedial options. Therefore, this life-threatening neuroendocrine condition requires targeted and effective therapies.

In 2019, the FDA approved brexanolone (BX), an intravenous formulation of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone (AP), as the first drug for the treatment of PPD [1]. BX rapidly relieves postpartum symptoms within hours of administration, in contrast to traditional antidepressants that take several weeks to take effect. This article highlights the molecular basis and mechanistic rationale for neurosteroid therapy in PPD.

Role of neurosteroids in PPD

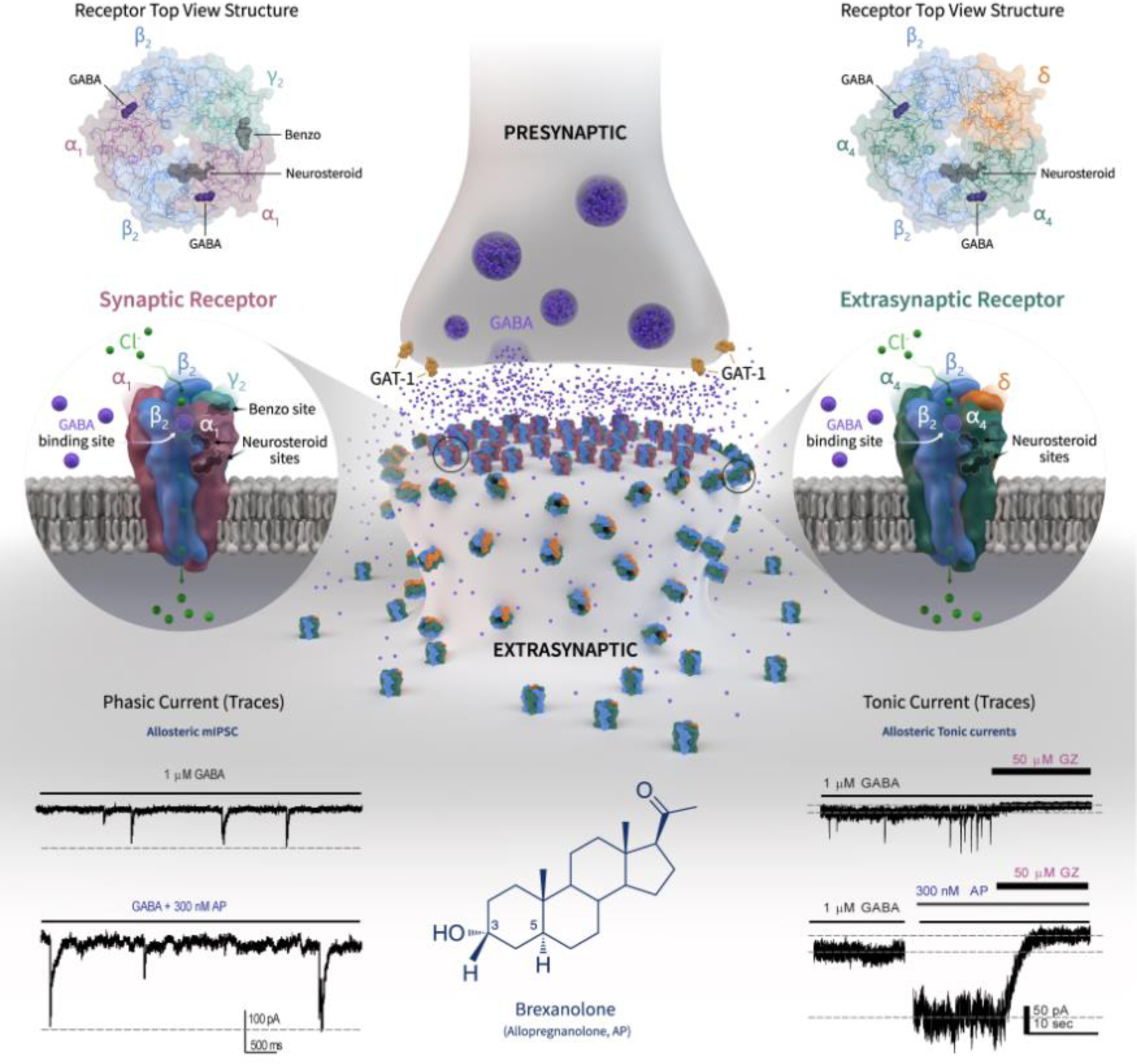

PPD has a complex pathophysiology involving many hormones and genetic factors. Neurosteroids play a pivotal role in PPD and various women’s health conditions [2,3]. Neurosteroids are steroid molecules synthesized within the brain that rapidly affect neuronal excitability. A variety of neurosteroids are present in the human brain, most prominently the progesterone-derived AP and the deoxycorticosterone-derived allotetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone [3]. Neurosteroids are synthesized from cholesterol or steroid hormone precursors in neurons and microglia and affect network excitability by direct interaction with GABA-A receptors (GABA-ARs), the primary receptors responsible for inhibitory currents in the brain (Fig.1). Neurosteroids are among the most potent agonists of GABA-ARs: at physiological levels (~20nM), they allosterically potentiate GABA-gated currents, whereas at pharmacological levels (~200nM), they directly activate receptor channels [4]. The structural basis for this potentiation, however, remains unclear. Neurosteroids bind to specific interface sites to increase conductance of chloride influx. This effect occurs at both synaptic (γ-containing) and extrasynaptic (δ-containing) receptors, with distinct site-specific kinetics for mediating inhibitory transmission (Fig.1). Neurosteroids uniquely bind to all subunit isoforms, with preferential sensitivity at extrasynaptic δ-containing GABA-ARs that generate non-desensitizing tonic currents [4].

Figure 1. Mechanisms of brexanolone actions at synaptic and extrasynaptic GABA-A receptors.

BX’s mechanism in PPD involves elevating brain allopregnanolone (AP), which may decrease significantly at postpartum, back to third trimester levels. AP acts as a preferential allosteric modulator and direct activator of extrasynaptic δGABA-ARs, which causes persistent hyperpolarization of neurons and shunts network hyperexcitability. Although the precise binding location is unclear, both activation and potentiation functions of AP apparently proceed from a single interfacial binding site, specifically at the α-subunit lipid interface. AP enhances the receptor function by binding to “neurosteroid binding” sites, which are distinct from sites for GABA and benzodiazepines. Based on their location and kinetics, GABA-ARs are stratified into two groups. Synaptic receptors (α1β2γ2 subunits) mediate phasic inhibition in response to presynaptic release of GABA, while extrasynaptic receptors (α4β2δ subunits) primarily contribute to tonic inhibition in response to ambient levels of GABA (representative traces shown). AP not only potentiate but also directly activate extrasynaptic and synaptic GABA-ARs at higher concentrations. As shown in phasic and tonic current recordings from dentate gyrus granule cell neurons, AP can promote maximal inhibition by enhancing both phasic and tonic inhibition in the brain, especially during the neurosteroid-deficient postpartum period that is linked to PPD symptoms. This cascade is consistent with the rapid relief of PPD symptoms after BX treatment compared to standard antidepressants. See [3,8]. Abbreviations: AP, allopregnanolone; GZ, gabazine; mIPSC, miniature inhibitory postsynaptic current.

PPD has been linked to reduced neurosteroid synthesis [2,5]. Although clinical data are mixed, a prevailing hypothesis for PPD symptoms is the postpartum decline of progesterone-derived AP after delivery, commonly referred to as neurosteroid withdrawal (NSW) [3,6]. Progesterone levels peak during the third trimester, leading to elevated AP (~150nM) in the brain. This prolonged rise in AP dampens the trafficking of extrasynaptic GABA-ARs. After parturition, the decline in AP creates a complex NSW-like milieu triggering hyperexcitability and dysphoria [3,6]. The levels of AP return to baselines (~5nM) similar to those observed before pregnancy, while receptors take longer to recover in susceptible women. The resulting imbalance between neurosteroid levels and GABA-AR plasticity is considered crucial in the development of PPD [3,6–8]. However, clinical studies on AP levels have yielded mixed results, and they often fail to consider the influence of stress on PPD. Elevated AP levels, indicative of a dysregulated stress response, have been identified as an additional marker of PPD [5]. Moreover, it is likely that sensitivity to changes in neurosteroids, rather than absolute levels, play a more significant role in PPD [8]. Ongoing research aims to clarify the molecular pathophysiology of PPD. Nevertheless, traditional antidepressants are less effective for PPD because the serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways require more chronic dosing to elicit a treatment response. Conversely, neurosteroid therapy can be effective for PPD by rapidly restoring the network sensitivity when replenishing with AP levels similar to those in the third trimester of pregnancy.

Neurosteroid replacement therapy

GABAergic neurosteroids have potent anxiolytic, antidepressant, and antiseizure properties in neuroendocrine conditions associated with neurosteroid deficiency or withdrawal, such as PPD [3]. In NSW, prolonged exposure (luteal-phase, pregnancy) followed by abrupt fall or decline (menstruationphase, postpartum) in progesterone-derived neurosteroids trigger anxiety and seizures [1,6]. During this deficiency state, there is a striking increase in the protective potency of exogenous neurosteroids [7]. This increase in efficacy occurs due to a two-fold upregulation of extrasynaptic δ-containing GABA-ARs, which mediates greater tonic currents and confers supersensitivity to AP [8] (Fig.1). Taken together, neurosteroid replacement therapy (NRT), involving selective administration of neurosteroids during the peak therapeutic window, is a viable strategy for treating the neurosteroid-deficient PPD [1,9].

The NRT strategy, which is pioneered by our decade-long research [1,3,6,7,8,9], has been successfully applied in the development of BX for PPD [1,5]. Postpartum mothers are provided with doses of AP equivalent to third-trimester levels (150nM=50ng/ml) in a pulse protocol for three days. Although precise physiological changes have not been fully characterized, experimental and clinical studies confirm the neurosteroid deficiency with impaired receptor plasticity and tonic inhibition at parturition, which trigger PPD symptoms in susceptible women [3,9]. Elevated levels of AP during pregnancy may downregulate δ-containing GABA-ARs, which fail to upregulate among those who develop PPD [8]. There is a consistent link between reduced AP and depression-like behavior [5], supporting this concept.

Development of brexanolone for PPD

BX is an injectable formulation of AP in cyclodextrin solution (Table 1). Unlike traditional antidepressants, which are not explicitly indicated for PPD, BX is approved by the FDA as the first PPD-specific treatment for adult women [1]. When released from the BX-cyclodextrin formulation, AP molecules readily cross the blood-brain barrier and act within the brain. Given its poor absorption and rapid clearance, BX (30–90-mcg/kg/hour) is given in a 60-hour infusion protocol. Its volume of distribution suggests extensive brain distribution. At these levels, pharmacological actions of BX stem from its allosteric modulation and direct activation of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABA-ARs [8] (Fig.1).

Table 1.

An overview of brexanolone

| Parameter | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Indications | Postpartum depression in women 18 years or older |

| Product | 100 mg/20 ml single-dose vial (5 mg/ml) with 20 g beta-dex sulfobutyl ether sodium solution (25% cyclodextrin solution) |

| Expiry period | 36 months (stored in refrigerator). Diluted solutions stored for a maximum of 12 hours only |

| Duration | 60-hour intravenous infusion |

| Dosage | 0 to 4 hours: Start with a dose of 30 mcg/kg/hour 4 to 24 hours: Increase the dose to 60 mcg/kg/hour 24 to 52 hours: Increase the dose to 90 mcg/kg/hour 52 to 56 hours: Decrease the dose to 60 mcg/kg/hour 56 to 60 hours: Decrease the dose to 30 mcg/kg/hour |

| Oral bioavailability | <5% |

| Volume of distribution (Vd) | 3 L/kg |

| Metabolism | Non-CYP pathways; its main metabolism routes include ketoreduction, glucuronidation, and sulfation pathways. |

| Half-life (t1/2) | 40 minutes |

| Effective half-life | 9 hours |

| Clearance (CL) | 0.8 L/h/kg |

| Protein binding | 99% |

| Drug-drug interactions | Due to its metabolism by multiple enzymes, it is unlikely to be a substrate of metabolic interactions with a concomitant drug |

| Hepatic effects | Metabolized by extra-hepatic pathways; no dosage adjustment is necessary with hepatic impairment |

| Common adverse effects | Headache, dizziness, somnolence/sedation, xerostomia, loss of consciousness, and hot flashes |

| REMS Monitoring | High doses are associated with altered state of consciousness and syncope, which are monitored through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS). |

| Warning and precautions | Contraindicated in patients who have a glomerular filtration rate of <15 mL/minute/1.73 m^2 due to the possible accumulation of solubilizing agent (betadex sulfobutyl ether sodium) in brexanolone formulation |

| Long-term safety | Patients were not followed after a 30-day follow-up period, limiting data on safety from long-term use |

BX has been evaluated in multiple clinical trials. The first two phase 2 trials, consisting of an open-label, proof-of-concept study [10] and a randomized controlled trial (NCT02614547)I [11], showed promising results of pilot safety and efficacy in PPD patients, leading to pivotal phase 3 trials. BX was evaluated in two multicenter, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials (NCT02942004)II (NCT02942017)III in 138 women with moderate to severe PPD. BX infusion (60 or 90 μg/kg/hour for 60 h) resulted in significant and clinically meaningful reductions in total Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) scores at 60-hours compared with placebo, with rapid onset of action and effective response during the study period and at 30-day follow-up [12]. The primary efficacy endpoint of HAM-D remission criteria, which requires a total score of ≤10 and a reduction of ≥50%, supports BX’s effectiveness [12]. A secondary post-hoc analysis of trial datasets demonstrated fast onset of improvement and high remission rates. Based on these outcomes, the FDA approved BX for PPD treatment at certified health facilities.

BX therapy is generally well-tolerated [12], with common side effects including headache, dizziness, and somnolence. However, BX carries a black box warning for sedation and sudden changes in consciousness (FDA-Label-#2019/211371lbl)IV (Table 1). Therefore, therapy requires patient participation in a REMS program to manage this potential adverse effect. Additionally, BX has not been well assessed in special populations, including young adults, pre-partum, and breastfeeding women. The effects of BX on infant brain development and breastmilk production are unclear, but transient somnolence is a potential risk for breast-fed infants. BX is also avoided in patients with end-stage renal disease. Overall, the use of BX requires careful consideration of its potential risks and benefits.

BX therapy has other limitations, such as restricted accessibility, the need for hospitalization for drug infusion, lack of oral treatment alternatives, and risk of adverse events requiring REM protocol. BX is effective for 30 days; however, it remains uncertain whether efficacy persists beyond this timeframe. Zuranolone, an orally-active synthetic neurosteroid, has shown promising efficacy in PPD (NCT02978326)V [13] but failed to achieve a significant reduction in symptoms lasting beyond 14 days in patients with major depression (NCT03672175)VI [14]. Benzodiazepines, which potentiate only synaptic, but not extrasynaptic, GABA-ARs (Fig.1) are not useful for PPD or major depression. Taken together, these outcomes attest to the specific potential of extrasynaptic GABA-ARs as significant targets for PPD.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

PPD affects 500,000 women in the USA annually. BX is the first neurosteroid approved for PPD and marks a significant milestone in the field of neuropsychopharmacology. BX is a breakthrough therapy for PPD, providing rapid relief of depressive symptoms that antidepressants like fluoxetine cannot achieve. BX’s efficacy confirms the crucial role of neurosteroids in postpartum symptoms and supports NRT as a rational and rapid-acting therapeutic strategy for PPD. Recent findings suggest that neurosteroid-sensitive extrasynaptic GABA-ARs may represent promising novel targets for PPD [13]. Further research is underway to explore the pathophysiology of PPD and to develop safer, water-soluble, and orally-administrable alternatives to BX.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01-NS051398 and R21-NS052158 (to DSR). Reddy’s research work was partly supported by the NIH CounterACT Program and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (Grant R21-NS076426, U01-NS083460, R21-NS099009, U01-NS117209, and U01-NS117278).

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Resources

- I. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02614547 .

- II. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02942004 .

- III. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02942017 .

- IV. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211371lbl.pdf .

- V. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02978326 .

- VI. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03672175 .

References

- 1.Reddy DS (2022) Neurosteroid replacement therapy for catamenial epilepsy, postpartum depression and neuroendocrine disorders in women. J. Neuroendocrinol 34, e13028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert Evans S et al. (2005) 3α-Reduced neuroactive steroids and their precursors during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Gynecol. Endocrinol 21, 26879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy DS (2016) Catamenial epilepsy: discovery of an extrasynaptic molecular mechanism for targeted therapy. Front. Cell. Neurosci 10, 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carver CM and Reddy DS (2016) Neurosteroid structure-activity relationships for functional activation of extrasynaptic δGABA-A receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap 357, 188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meltzer-Brody S and Kanes SJ (2020) Allopregnanolone in postpartum depression: Role in pathophysiology and treatment. Neurobiol. Stress 12, 100212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy DS et al. (2001) Neurosteroid withdrawal model of perimenstrual catamenial epilepsy. Epilepsia 42, 328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy DS and Rogawski MA (2001) Enhanced anticonvulsant activity of neuroactive steroids in a rat model of catamenial epilepsy. Epilepsia 42, 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carver CM et al. (2014) Perimenstrual-like hormonal regulation of extrasynaptic δ-containing GABA-A receptors mediating tonic inhibition and neurosteroid sensitivity. J. Neuroscience 34, 14181–14197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy DS and Rogawski MA (2009) Neurosteroid replacement therapy for catamenial epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics 6, 392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanes SJ et al. (2017) Open-label, proof-of-concept study of brexanolone in the treatment of severe postpartum depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 32, e2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanes S et al. (2017) Brexanolone (SAGE-547 injection) in post-partum depression: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 390 (10093), 480–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meltzer-Brody S et al. (2018) Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet 392(10152), 1058–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deligiannidis KM, et al. (2021) Effect of Zuranolone vs Placebo in Postpartum Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 78(9):951–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clayton AH et al. (2023) Zuranolone in major depressive disorder: Results from MOUNTAIN-A Phase 3, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 84(2), 22m14445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]