Abstract

A DNA region involved in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5 capsular polysaccharide (CP) biosynthesis was identified and characterized by using a probe specific for the cpxD gene involved in CP export. The adjacent serotype 5-specific CP biosynthesis region was cloned from a 5.8-kb BamHI fragment and an 8.0-kb EcoRI fragment of strain J45 genomic DNA. DNA sequence analysis demonstrated that this region contained four complete open reading frames, cps5A, cps5B, cps5C, and cps5D. Cps5A, Cps5B, and Cps5C showed low homology with several bacterial glycosyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of lipopolysaccharide or CP. However, Cps5D had high homology with KdsA proteins (3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid 8-phosphate synthetase) from other gram-negative bacteria. The G+C content of cps5ABC was substantially lower (28%) than that of cps5D and the rest of the A. pleuropneumoniae chromosome (42%). A 2.1-kb deletion spanning the cloned cps5ABC open reading frames was constructed and transferred into the J45 chromosome by homologous recombination with a kanamycin resistance cassette to produce mutant J45-100. Multiplex PCR confirmed the deletion in this region of J45-100 DNA. J45-100 did not produce intracellular or extracellular CP, indicating that cps5A, cps5B, and/or cps5C were involved in CP biosynthesis. However, biosynthesis of the Apx toxins, lipopolysaccharide, and membrane proteins was unaffected by the mutation. Besides lack of CP biosynthesis, and in contrast to J45, J45-100 grew faster, was sensitive to killing in precolostral calf serum, and was avirulent in pigs at an intratracheal challenge dose three times the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of strain J45. At six times the J45 LD50, J45-100 caused mild to moderate lung lesions but not death. Electroporation of cps5ABC into A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 strain 4074 generated strain 4074(pJMLCPS5), which expressed both serotype 1 and serotype 5 CP. However, serotype 1 capsule expression was diminished in 4074(pJMLCPS5) in comparison to 4074. The recombinant strain produced significantly less total CP (serotypes 1 and 5 CP combined) in log phase (P = 0.0012) but significantly more total CP in late stationary phase than 4074 (P < 0.0001). In addition, strain 4074(pJMLCPS5) caused less mortality and bacteremia in pigs and mice following respiratory challenge than strain 4074, indicating that virulence was affected by diminished capsule production. These results emphasize the importance of CP in the serum resistance and virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae.

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae is an encapsulated, gram-negative bacterium that causes swine pleuropneumonia, a frequently fatal and highly contagious respiratory disease. There are 12 recognized serotypes of A. pleuropneumoniae that vary in virulence and geographic predominance (33). The capsular polysaccharide (CP) is responsible for serotype specificity and is required for virulence (19, 20). Nonencapsulated A. pleuropneumoniae mutants obtained by chemical mutagenesis have been shown to be effective vaccine candidates in that they are safe and highly protective (20). However, not all such mutants are stable, and the nature of the mutation(s) is unknown. Hence, characterization of the genes involved in CP export and biosynthesis would be desirable.

We have previously reported cloning and sequencing an A. pleuropneumoniae DNA region involved in export of the CP of serotype 5a. This region consists of four genes, designated cpxABCD, which had a high degree of homology to the group II capsule export genes of Haemophilus influenzae type b (bexDCBA), Neisseria meningitidis group B (ctrABCD), and to a lesser extent, Escherichia coli K5 (kpsE and kpsMT) (54). This homology suggested that A. pleuropneumoniae also synthesized a group II capsule, whose organization predicted that the biosynthesis region would be upstream of cpxDCBA (12). We now report cloning and sequencing of four genes upstream of the cpx CP export region that correspond to capsular biosynthesis genes. A mutant with a deletion in three of these genes by allelic exchange was incapable of synthesizing CP and was avirulent in pigs. trans expression of these three genes in serotype 1 resulted in a chimeric strain producing both serotype 1 and 5 CP. However, expression of serotype 5 CP genes resulted in diminished production of serotype 1 CP, as well as diminished virulence in pigs and mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. For all experimentation, bacteria were grown at 37°C with vigorous shaking to mid-log phase (109 CFU/ml) in medium containing NAD (5 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) unless otherwise noted. For extraction of genomic DNA and for bactericidal assays, A. pleuropneumoniae strains were grown in brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) (BHI-N). For electroporation, A. pleuropneumoniae strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (Difco) containing 0.6% yeast extract (Difco) (TSY-N). For swine challenge experiments, A. pleuropneumoniae strains were grown in Columbia broth (Difco). E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (40) for routine cultivation or in Terrific broth (47) for extraction of plasmids. Antibiotic concentrations for maintaining plasmids in E. coli were 100 μg/ml for ampicillin, 80 μg/ml for streptomycin, and 50 μg/ml for kanamycin. Kanamycin was used at 85 μg/ml for selection of A. pleuropneumoniae recombinant mutants.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| A. pleuropneumoniae strains | ||

| 4074 | Serotype 1 (ATCC 27088) | ATCCa |

| 4074(pJLMCPS5) | Serotype 1 containing pJLMCPS5; serotype 1+ serotype 5+ Strepr | This work |

| 1536 | Serotype 2 (ATCC 27089) | ATCC |

| J45 | Serotype 5a | 17 |

| K17 | Serotype 5a | 17 |

| 178 | Serotype 5 | M. Mulks |

| 29628 | Serotype 7 | L. Hoffman |

| 13261 | Serotype 9 | J. Nicolet |

| J45-C | Ethyl methanesulfonate mutant of J45; nonencapsulated, nontypeable | 20 |

| K17-C | Ethyl methanesulfonate mutant of K17; nonencapsulated, nontypeable | 19 |

| J45-100 | Nonencapsulated, nontypeable mutant of J45; cps5ABC Kanr | This work |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac (F+proABlacIqZΔM15 Tn10); host for recombinant plasmids | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-3z | Cloning vector, 2.74 kb; Ampr | Promega |

| pCW-1C | 5.3-kb XbaI fragment of J45 cloned into pGEM-3z | 54 |

| pCW-11E | 5.8-kb BamHI fragment of J45 cloned into pGEM-3z | This work |

| pMLAp53 | 8.0-kb EcoRI fragment of J45 cloned into pGEM-3z | This work |

| pKS | 3.8-kb BamHI fragment containing the nptIb-sacRB cartridgec cloned into the BamHI site of pGEM-3z; Ampr Kanr | S. M. Boyle |

| pCW11EΔ1KS1 | pCW-11E with the 2.1-kb BglII-StuI fragment deleted and the 3.8-kb BamHI nptI-sacRB cartridge from pKS ligated | This work |

| pLS88 | Broad-host-range shuttle vector from H. ducreyii; Strepr Kanr | 57 |

| pJLMCPS5 | pLS88 containing cps5ABC in the Kan site; Strepr | This work |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.

This marker was originally derived from the Tn903 nptI gene of pUC4K (Pharmacia Biotech).

This cartridge has been previously described (36).

Calculation of generation time.

The generation time of logarithmic-phase A. pleuropneumoniae strains grown in TSY-N was calculated by using the equation g = R/1, where g is the generation time of the bacterial population and R is the average rate of bacterial growth (34). The average rate of growth, R, was calculated by using the following equation: R = 3.32(log10 N − log10 N0)/t, where t is the elapsed time, N is the number of bacteria at time t, and N0 is the initial number of bacteria at time zero.

DNA hybridization.

Restriction endonuclease-digested DNA was electrophoresed through 0.7% agarose gels and was transferred by capillary action to MagnaGraph nylon membranes (Micron Separations Inc., Westboro, Mass.) by using 20× SSC (3 M NaCl, 300 mM sodium citrate [pH 7]) as previously described (40, 44). DNA was covalently linked to nylon membranes by UV irradiation using a UV Stratalinker (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Digoxigenin-labeled probes for DNA hybridizations were synthesized by the random primer method by using a Genius system nonradioactive labeling and detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim Corp., Indianapolis, Ind.) according to the manufacturer’s directions. DNA hybridizations were performed at 68°C in solutions containing 5× SSC. The membranes were washed and developed according to the Genius system directions for colorimetric detection.

Recombinant DNA methods.

Genomic DNA was isolated from A. pleuropneumoniae as previously described (54). Plasmid DNA was isolated by a rapid alkaline lysis method (22). Restriction fragments required for cloning and probe synthesis were eluted from agarose gels as described elsewhere (59). Restriction digests, agarose gel electrophoresis, and DNA ligations were done with T4 DNA ligase (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) (40). DNA fragments were cloned by ligating electroeluted BamHI-digested or EcoRI-digested J45 genomic DNA in the range of 5.0 to 6.5 kb or 7.0 to 10.0 kb into the BamHI site or the EcoRI site in pGEM-3z, respectively. Restriction fragments were made blunt ended by filling in 5′ overhangs with deoxynucleotide triphosphates (Boehringer Mannheim), using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) (40). Plasmid DNA was electroporated into E. coli strains (8) by using a BTX ECM 600 electroporator (BTX, Inc., San Diego, Calif.).

Multiplex PCR.

Gene products of 0.7 and a 1.1 kb were amplified from A. pleuropneumoniae DNA with forward and reverse primers (Genosys Biotechnologies, Inc., The Woodlands, Tex.) directed to a portion of cpxC and cpxD (54) and to a portion of cps5A and cps5B (30), respectively.

Construction of nonencapsulated A. pleuropneumoniae by allelic exchange.

The pCW11EΔ1KS1 suicide vector for knockout mutagenesis was constructed by first digesting pCW-11E with BglII and StuI to create a large deletion that spanned cps5ABC (Fig. 1). The end of the BglII site was made blunt ended, and the large 6.4-kb fragment was ligated to the 3.8-kb BamHI fragment of pKS (also made blunt ended) containing the Tn903 nptI gene (36), which confers kanamycin resistance (Kanr) to A. pleuropneumoniae (48). The pCW11EΔ1KS1 vector was purified through a CsCl gradient (40) and electroporated into mid-logarithmic-phase A. pleuropneumoniae J45, previously washed four times in chilled (4°C), filter-sterilized buffer (28) modified to contain 272 mM mannitol, 2.43 mM K2HPO4, 0.57 mM KH2PO4, and 15% glycerol (pH 7.5). The cells were then washed once in chilled, filter-sterilized 15% glycerol and resuspended to approximately 1010 CFU/ml in 15% glycerol. Aliquots of this suspension (90 μl) were mixed with 1.5 to 2.0 μg of plasmid DNA. The mixture was placed in chilled 2-mm gap electroporation cuvettes (BTX), and a BTX ECM 600 electroporator (BTX) set to a charging voltage of 2.5 kV and a resistance setting of R7 (246 ohms) was used for electroporation. The actual pulse generated was 2.39 kV delivered over 10.7 ms. After electroporation, the cells were recovered in 1 ml of TSY-N containing 5 mM MgCl2 with gentle shaking for 3.5 h at 37°C. After recovery, the cells were cultured on TSY-N agar containing 85 μg of kanamycin/ml at 37°C.

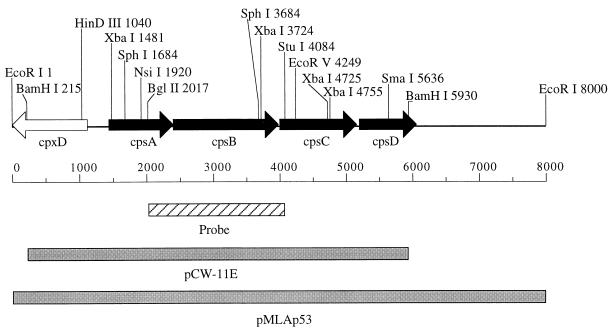

FIG. 1.

Physical map of pCW-11E and pMLAp53 inserts from A. pleuropneumoniae J45. The location and direction of transcription of the four complete ORFs (cps5ABCD; solid fill) identified by sequencing are indicated. The location and direction of transcription of the incomplete cpxD gene located on this DNA fragment are also indicated. The 2.1-kb BglII-StuI fragment used as the DNA probe in Fig. 3 is indicated. Shaded lines indicate the 5.7-kb insert of pCW-11E and the 8.0-kb insert of pMLAp53.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

Double-stranded DNA templates were sequenced by the dideoxy-chain termination method (41) using custom oligonucleotide primers (DNAgency, Inc., Malverne, Pa., and Genosys Biotechnologies). The nucleotide sequence of both strands of the 2.7-kb XbaI-EcoRV DNA fragment of pCW-11E was determined by using a Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (United States Biochemical Corp., Cleveland, Ohio) with [35S]dATP (DuPont/NEN Research Products, Boston, Mass.). The nucleotide sequences of both strands of the 1.7-kb EcoRV-BamHI fragment of pCW-11E and a portion of the 2.1-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment of pMLAp53 were determined using an AutoRead kit with Cy5-dATP labeling on an ALFexpress DNA sequencer (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.).

The nucleotide sequence obtained was combined with the nucleotide sequence of the 4.6-kb XbaI-ClaI DNA fragment of pCW-1C (54) and was analyzed with DNASTAR analysis software (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.). Sequence similarity searches of the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases were performed using BLAST software (2) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, Md.).

Expression of cps5ABC.

Plasmid pLS88, which contains Kanr and streptomycin resistance (Strepr) markers, was first isolated from H. ducreyi and is an effective shuttle vector in A. pleuropneumoniae (57). The A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 5a CP biosynthesis genes were subcloned into this vector by ligating the gel-purified 4.7-kb XmaI-HindIII fragment from pMLAp53 to XmaI-HindIII-digested pLS88, which deleted the Kanr site. Colonies were screened by hybridization with a probe specific for the cps5 region. The resulting plasmid, pJMLCPS5, was introduced into strains J45-100 and 4074 serotype 1 by electroporation as described above.

Immunoblotting.

For colony immunoblots, A. pleuropneumoniae whole cells grown overnight on TSY-N agar plates were suspended in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS), and adjusted to 109 CFU/ml, determined spectrophotometrically. Approximately 105 CFU was applied to a nitrocellulose membrane (NitroBind; Micron Separations Inc., Westboro, Mass.) by using a Bio-Dot apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.). All incubations were at room temperature. The membrane was placed in chloroform for 15 min to lyse the bacteria, air dried, and incubated for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.5 (TBS), containing 2% nonfat dry milk to block nonspecific binding. The membrane was incubated 1 h in a 1:200 dilution of monospecific swine antiserum to the serotype 5a CP (19) in 2% milk–TBS. The membrane was washed in TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and then incubated for 1 h in a 1:1,000 dilution of rabbit anti-swine immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (heavy and light chains; Cappel, Durham, N.C.). The membrane was washed in TBS and then developed with 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Bio-Rad) in TBS containing 0.02% H2O2.

Immunoblotting of A. pleuropneumoniae concentrated culture supernatant was performed as described previously (31). The strips were incubated overnight at 4°C with either a monoclonal antibody specific for Apx toxin II (ApxII) (31) or a monoclonal antibody specific for ApxI (7, 11).

Quantitation of CP by latex agglutination and enzyme linked-immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Latex agglutination was done as previously described (18). Semiquantitation of serotype 1 and 5 CPs was determined by the greatest dilution of bacterial culture (cells and culture medium) that resulted in clear but minimal agglutination of latex particles conjugated to CP-specific IgG (2+ reaction) compared to purified CP.

A sandwich ELISA, which was a modification of a previous assay (19), was used to more accurately quantitate CP. Optimal antibody concentrations were determined by checkerboard titration. Reagents were added to polystyrene plates (Nunc, Inc., Naperville, Ill.) in the following order: 10 μg of purified rabbit IgG (18) to serotype 1 or serotype 5 CP per ml in carbonate buffer, blocking buffer (PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, 5% nonfat dry milk, and 10% normal goat serum), 100 to 0.8 ng of purified CP per ml or dilutions of bacterial culture in blocking buffer, 5 μg of purified pig IgG to serotype 1 or serotype 5 CP per ml in blocking buffer, 1:3,000 dilution of goat anti-swine IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, Pa.), and ABTS peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.). All incubations were for 1 h at 37°C, except that after addition of ABTS substrate, which was for 30 min at room temperature. Wells were washed five times in PBS-Tween 20 between each step. The absorbance at 405 nm was determined with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Menlo Park, Calif.). Control wells for subtraction of background contained all reagents except antigen. Assays for quantitation of serotypes 1 and 5 CPs were done in quadruplicate, and the mean, standard deviation, and P value were calculated by the unpaired t test using InStat computer software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, Calif.).

Phenotypic analysis.

Crude CP was isolated from culture supernatant by precipitation with 5 mM hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide, extraction with 0.4 M NaCl, ethanol precipitation, and lyophilization (17). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was isolated from A. pleuropneumoniae by a micro hot phenol-water extraction method (16), and the electrophoretic profiles were examined as described elsewhere (16, 51). Protein-enriched outer membranes were prepared and electrophoretically examined as described previously (19). Apx toxin activity in concentrated culture supernatant was determined as described previously (20, 31).

Serum bactericidal assay.

The sensitivity of A. pleuropneumoniae to the bactericidal activity of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, and 50% precolostral calf serum was determined after 60 min of incubation at 37°C as described previously (53).

Virulence studies.

Pigs 7 to 9 weeks of age were obtained from two local herds free from A. pleuropneumoniae infection and were distributed randomly into groups. Groups of pigs were housed in separate pens, with no direct physical contact permitted between groups. Broth-grown bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000 × g and resuspended to approximately 109 CFU/ml in PBS. Viable plate counts were done to confirm the inoculating dose. Pigs were challenged intratracheally with 5 ml of a dilution of this suspension following mild sedation with Stresnil (Pittman-Moore, Inc., Washington Crossing, N.J.). Pigs were necropsied as soon as possible after death or immediately after euthanasia with sodium pentobarbital. Lung lesions were scored on a scale of 0 to 4 as previously described (20). Lung samples were taken at necropsy from the right cranial-dorsal aspect of the caudal lobe and cultured on BHI-N to isolate A. pleuropneumoniae.

Mice were challenged intranasally with 1.2 × 107 to 1.5 × 107 CFU of A. pleuropneumoniae recombinant or parent strain in 40 μl as described previously (21). Blood and spleen samples were collected aseptically and cultured onto BHI-N to measure bacteremia. The two-sided P values were calculated by using Fisher’s exact test for 2 × 2 contingency tables (InStat software) to determine statistical differences in mortality by isogenic strains.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of cps5ABCD was determined, submitted to GenBank, and assigned accession no. AF053723.

RESULTS

Identification and cloning of A. pleuropneumoniae serotype-specific DNA.

Southern blot analyses were performed to identify an adjacent DNA region upstream from the cpxDCBA CP export gene cluster (54), which we expected to contain serotype-specific genes involved in CP biosynthesis (12). Both BamHI-digested and EcoRI-digested A. pleuropneumoniae J45 genomic DNAs were probed with the digoxigenin-labeled 1.2-kb BamHI-XbaI fragment of pCW-1C that contained a portion of the cpxD gene (54). This cpxD-specific probe hybridized to a 5.8-kb BamHI DNA fragment and to an 8.0-kb EcoRI DNA fragment of strain J45 chromosomal DNA, which were cloned into the BamHI site and the EcoRI site of pGEM-3Z, respectively. The plasmid containing the 5.8-kb BamHI fragment was designated pCW-11E, and the plasmid containing the 8.0-kb EcoRI fragment was designated pMLAp53. Portions of both the pCW-11E and the pMLAp53 inserts overlapped the DNA present on the insert of pCW-1C (54) (Fig. 1).

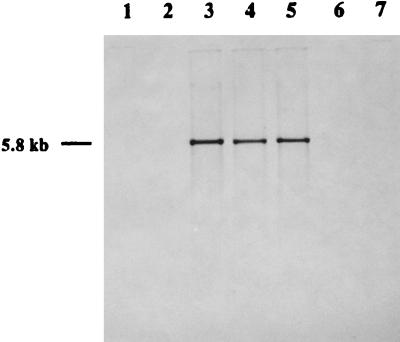

The 2.1-kb BglII-StuI DNA fragment of pCW-11E (Fig. 1) hybridized to a 5.8-kb BamHI genomic DNA fragment from three A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 5 strains tested but not to genomic DNA from serotypes 1, 2, 7, and 9 (Fig. 2). Thus, the A. pleuropneumoniae DNA in pCW-11E contained DNA that was specific to serotype 5 strains.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of A. pleuropneumoniae genomic DNA hybridized to the digoxigenin-labeled 2.1-kb BglII-StuI fragment of pCW-11E. BamHI-digested genomic DNAs from serotype 1 strain 4074 (lane 1), serotype 2 strain 1536 (lane 2), serotype 5a strain J45 (lane 3), serotype 5a strain K17 (lane 4), serotype 5 strain 178 (lane 5), serotype 7 strain 29628 (lane 6), and serotype 9 strain 13261 (lane 7) were hybridized with the probe as described in Materials and Methods. The molecular mass of the hybridizing bands is indicated on the left.

Nucleotide sequence and analysis of the serotype-specific A. pleuropneumoniae DNA region.

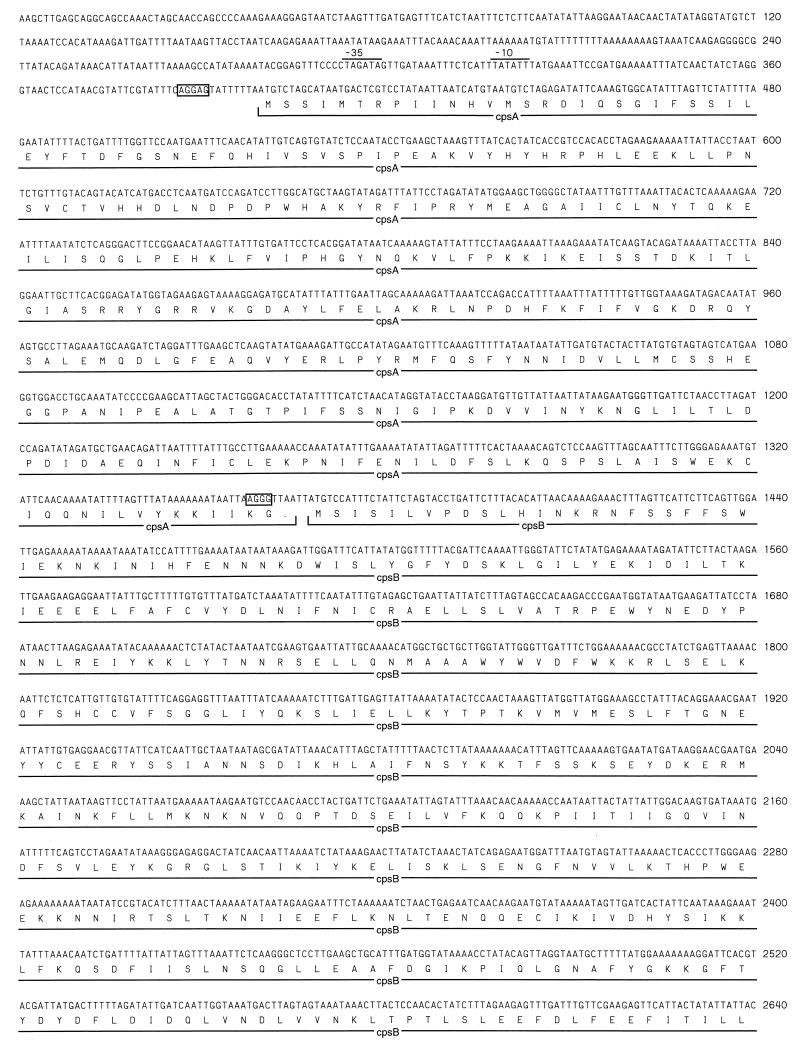

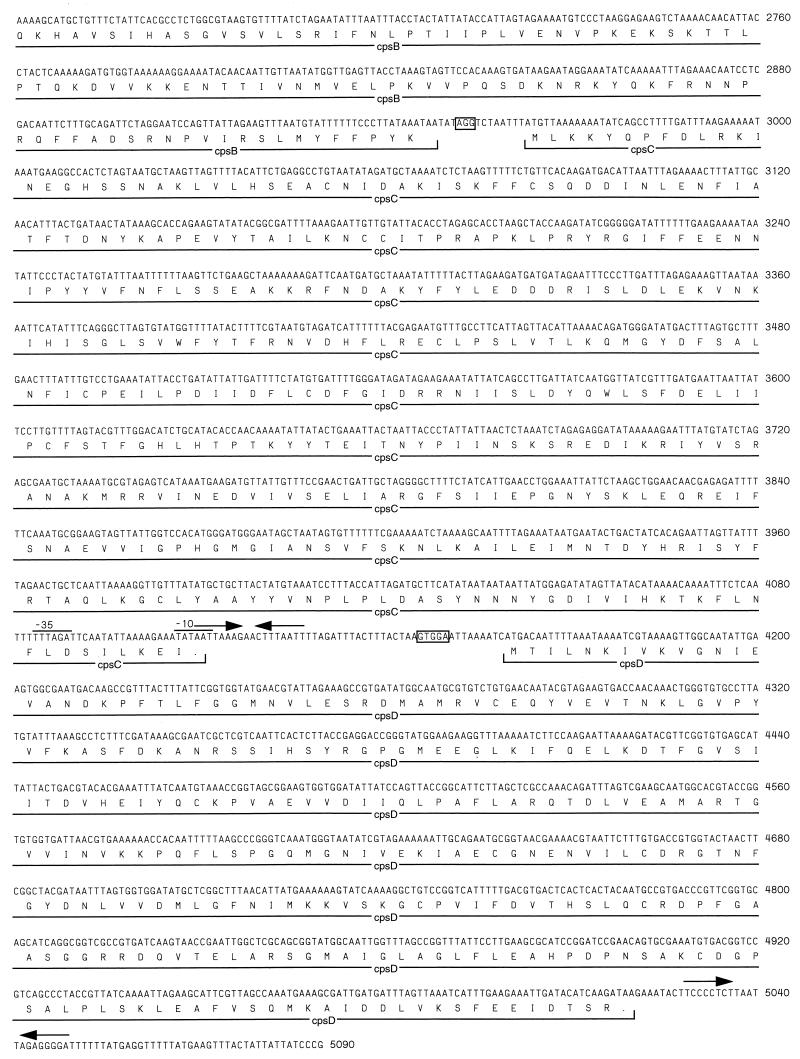

The nucleotide sequence of the 4.4-kb XbaI-BamHI fragment of pCW-11E and a portion of the 2.1-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment of pMLAp53 were determined. The nucleotide sequences of pCW-11E and pMLAp53 inserts contained four open reading frames (ORFs) designated cps5A, cps5B, cps5C, and cps5D (cps5 for capsular polysaccharide synthesis serotype 5) upstream and on the opposite strand from cpxD (Fig. 1 and 3). The AUG initiation codon of cps5B was 3 nucleotides downstream from the UAA termination codon of cps5A, and the AUG initiation codon of cps5C was identified 15 bases downstream from the UAA termination codon of cps5B. The initiation codon of cps5D was 49 bases downstream from the UAA termination codon of cps5C. Shine-Dalgarno ribosome-binding consensus sequences (42) were identified within 13 bases upstream of the AUG initiation codons of cps5A, cps5B, cps5C, and cps5D. Putative promoters containing sequences similar to the E. coli ς70 −10 (TATAAT) and −35 (TTGACA) consensus sequences (14) were identified upstream of both cps5A and cps5D. The putative cps5D promoter was within the cps5C coding sequence. A sequence containing 8-bp inverted repeats with the potential to serve as a rho-independent terminator was identified downstream of cps5D. A sequence containing an A+T-rich 8-bp inverted repeat was identified downstream of cps5C. The G+C content for the DNA region encoding cps5ABC was 28%, whereas the G+C content for the DNA region encoding cps5D was 42%.

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the four ORFs detected in the serotype-specific capsular biosynthesis region from A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 5a. Putative ribosome-binding sites preceding each ORF are boxed. Putative −10 and −35 promoter sequences upstream of cps5A are cps5D are indicated by lines, and inverted repeats downstream of cps5C and cps5D are indicated by arrows.

The predicted polypeptides of cps5ABCD were composed of 321 (Cps5A), 526 (Cps5B), 382 (Cps5C), and 286 (Cps5D) amino acids (Fig. 3). The predicted molecular masses for the polypeptides were 36.9, 61.7, 44.5, and 31.3 kDa, respectively. Hydropathy plots demonstrated that Cps5A, Cps5B, Cps5C, and Cps5D were relatively hydrophilic proteins, suggesting that these proteins may be associated with the cytoplasmic compartment (analysis not shown). BLAST searches (2) of the combined, nonredundant nucleotide and protein databases at the National Center for Biotechnology Information did not reveal any substantial homology between cps5ABC at the nucleotide level with other sequences in the databases (analysis not shown). However, a low level of homology was observed between Cps5A and several bacterial glycosyltransferases at the amino acid level, particularly the E. coli rfb protein B, an O-antigen glycosyltransferase involved in LPS biosynthesis (3, 5, 26, 29, 46). The highest homology was at residues 190 to 253 of Cps5A and residues 554 to 621 of protein B (55% similarity) (5). Cps5B had low homology with the region 2 (biosynthesis region) ORF3 predicted protein product of the H. influenzae type b capsulation locus (52). Cps5C had low similarity with the Vibrio anguillarum rfb region ORF51x5 predicted protein (GenBank accession no. AF025396) (24). The cps5D gene had high homology with kdsA genes, which encode 3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid (dOclA) 8-phosphate synthetase from other gram-negative bacteria. At the nucleotide level, cps5D was 77% identical to the E. coli kdsA gene (58), 78% identical to the H. influenzae kdsA gene (50), and 80% identical to the Pasteurella haemolytica kdsA gene (4). At the amino acid level, the predicted Cps5D protein was 80% similar to E. coli KdsA, 87% similar to the H. influenzae KdsA protein, and 89% similar to P. haemolytica KdsA.

Production of nonencapsulated A. pleuropneumoniae by allelic exchange.

The pCW11EΔ1KS1 vector did not replicate in A. pleuropneumoniae (unpublished data), enabling it to function as a suicide vector. After pCW11EΔ1KS1 was electroporated into A. pleuropneumoniae J45, seven Kanr transformants were obtained after the recovery mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 2 days. Four of these Kanr transformants were noniridescent when visualized with obliquely transmitted light, suggesting that they were nonencapsulated (data not shown). One of these transformants was randomly selected for further study and was designated J45-100.

Southern blot analyses of genomic DNA isolated from J45 and J45-100 with DNA probes specific for the nptI gene, the 2.1-kb BglII-StuI fragment of pCW-11E, and the 2.1-kb ClaI fragment of pCW-1C were performed (data not shown). The nptI-specific DNA probe hybridized to a 5.0-kb fragment of XbaI-digested J45-100 DNA but not to J45 DNA, verifying that the nptI marker was in the chromosome of J45-100. The 2.1-kb BglII-StuI fragment of pCW-11E hybridized to a 5.8-kb fragment of BamHI-digested J45 but not J45-100 DNA, verifying that this fragment was deleted in J45-100. The 2.1-kb ClaI probe specific for cpxABC hybridized to a 5.3-kb XbaI fragment of both J45 and J45-100, verifying that this portion of the A. pleuropneumoniae capsulation locus was unaffected by the double-recombination event that had occurred within the adjacent DNA region. The same hybridization results were obtained with the other three noniridescent transformants, indicating the same double-recombination event occurred in each transformant (data not shown).

Further evidence of a deletion in cps5 was obtained by multiplex PCR using primers specific to cpxCD and cps5AB (30). The cpxCD primers generated a 0.7-kb fragment from encapsulated serotype 5 strains J45 and K17, two nonencapsulated strains derived by chemical mutagenesis, J45-C and K17-C (19, 20), and recombinant strain J45-100. However, the 1.1-kb product of the cps5AB primers was amplified from each strain except J45-100, which was consistent with the engineered deletion in J45-100.

Phenotypic characterization of J45-100.

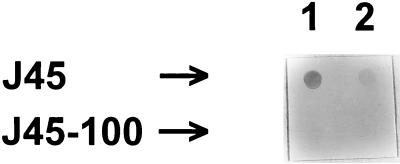

Monospecific antiserum to CP reacted with colonies of J45 but did not react with J45-100 (Fig. 4). The bacterial colonies on the membrane had been lysed in chloroform, indicating that J45-100 was unable to synthesize CP, as opposed to being unable to export it. In addition, neither whole nor sonicated J45-100 agglutinated latex particles that were conjugated to IgG specific for serotype 5a CP (18), whereas J45 whole cells and sonicated J45-C cells strongly agglutinated the conjugated latex particles (data not shown). These results verified that the deletion engineered into the cps region of A. pleuropneumoniae J45-100 resulted in the loss of CP biosynthesis. Furthermore, these results indicated that nonencapsulated mutant J45-C, isolated after ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis (20), produced intracellular but not extracellular CP.

FIG. 4.

Colony immunoblot of A. pleuropneumoniae J45 and J45-100 reacted with CP-enriched swine antiserum. Approximately 5 × 105 (lane 1) or 5 × 104 (lane 2) CFU per well was applied to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was lysed in chloroform and incubated with a swine antiserum that contained monospecific antibodies to the serotype 5a CP.

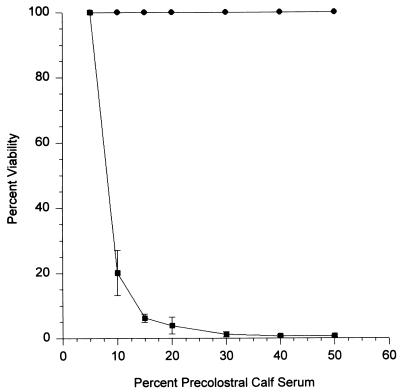

The expression and electrophoretic profiles of ApxI and -II, outer membrane proteins, and LPS were unchanged in J45-100 compared to its parent (data not shown). The growth curves of J45 and J45-100 in TSY-N were similar but not identical. Viable plate counts indicated that during logarithmic growth, J45-100 grew faster (generation time = about 23 min) than parent strain J45 (generation time = about 28 min) (data not shown). Recombinant strain J45-100 was efficiently killed within 60 min in 10 to 50% precolostral calf serum as a complement source, whereas encapsulated parent strain J45 was not killed at any concentration of serum (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Bactericidal activity of precolostral calf serum for A. pleuropneumoniae J45 and J45-100. Percent viability of bacterial strains was evaluated after 60 min of incubation at 37°C. Each data point represents the mean of three separate experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviations for each mean. The maximum percent viability recorded for J45 was 100%. Values greater than 100% were not recorded because they could not be accurately determined.

Expression of cps5ABC.

The entire cps5ABC region was cloned in the broad-host-range vector pLS88 to obtain pJLMCPS5, which was electroporated into strain J45-100. Strepr colonies of J45-100 were not obtained after several attempts. We attempted to modify the methylation pattern of pJMLCPS5 by cloning it into A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 strain 4074. About 27 Strepr colonies were obtained following electroporation of 9.6 × 109 CFU of 4074. Eighteen of the Strepr colonies were screened, and five contained a plasmid of the expected size. Each of these five recombinant strains appeared more mucoid than parent strain 4074, and therefore one isolate [4074(pJMLCPS5)] was randomly selected for further characterization.

Strain 4074(pJMLCPS5) was agglutinated by serotype 1- and serotype 5-conjugated latex particles, indicating that both CP types were being expressed. There was no agglutination of 4074 with the serotype 5 latex particles. To determine if the more mucoid phenotype of 4074(pJMLCPS5) was due to CP expression, CP was semipurified from culture supernatants of the parent and recombinant strains at mid-log phase (109 CFU/ml, or about 180 Klett units) and at late stationary phase (overnight culture, or about 355 Klett units). Viable cell plate counts were done from log-phase cultures. Accurate cell counts cannot be determined from late-stationary-phase cultures, and so CP content was calculated per Klett unit for comparative purposes. At mid-log phase, the amount of total crude CP obtained from culture supernatant of the parent was 5 × 10−6 mg/CFU, or 0.46 mg/Klett unit. The amount of total CP obtained from 4074(pJMLCPS5) supernatant in log phase was 6 × 10−7 mg/CFU, or 0.39 mg/Klett unit. In contrast, the total amount of CP purified from 4074 overnight culture supernatant was 0.13 mg/Klett unit, and the total amount of CP purified from 4074(pJMLCPS5) culture supernatant was 0.16 mg/ Klett unit. When the serotype-specific CP content was measured by latex agglutination in comparison to semipurified CP, we determined that the total amount of serotype 1 CP in cell culture (cells and culture medium) made by strain 4074 was approximately 7.5 × 10−4 ng/CFU, or 441 ng/Klett unit. In contrast, the total amount of serotype 1 CP made by 4074(pJMLCPS5) was 5.0 × 10−4 ng/CFU, or 269 ng/Klett unit. Strain 4074(pJMLCPS5) also made 2.0 × 10−5 ng of serotype 5 CP/CFU, or 107.5 ng/Klett unit (cells and culture medium). By late stationary phase, both strains 4074 and 4074(pJMLCPS5) made a total of about 694 ng of serotype 1 CP/Klett unit, and 4074(pJMLCPS5) also made 288 ng of serotype 5 CP/Klett unit.

A more accurate analysis of the CP content present in cell cultures (cells and culture medium) was made by capture ELISA (Table 2). There was significantly more serotype 1 CP/CFU made by 4074 than by 4074(pJMLCPS5) in log phase (P = 0.0252). The difference was more significant when the amount of serotype 1 CP/Klett unit was measured either in log phase (P = 0.0003) or in late stationary phase (P = 0.0009). These results showed that at both log and late stationary phases, strain 4074(pJMLCPS5) made less serotype 1 CP than strain 4074. In log phase, there was also relatively little serotype 5 CP made by 4074(pJMLCPS5), and the combination of the two CPs (116.5 ng/Klett unit) was less than the amount of serotype 1 CP made by 4074 in log phase (123.5 ng/Klett unit). However, by late stationary phase, the combination of serotypes 1 and 5 CP made by 4074(pJMLCPS5) (479.2 ng/Klett unit) was greater than the amount of serotype 1 CP made by 4074 (452 ng/Klett unit). Therefore, in log phase relatively little serotype 5 CP was expressed by 4074(pJMLCPS5), and expression of serotype 1 CP was somewhat inhibited. However, by late stationary phase, more serotype 5 CP was produced, and the combination of the two CPs was greater than the amount of CP made by serotype 1 alone, explaining why overnight colonies of 4074(pJMLCPS5) appeared more mucoid than the parent strain. There was no significant difference in growth rate or hemolytic activity between 4074 and 4074(pJMLCPS5) (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Serotype 1 and 5 CP content of strains 4074 and 4074(pJMLCPS5) by capture ELISA

| Strain | Growth phase | Mean ± SD

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 CP (ng/CFU) | Type 5 CP (ng/CFU) | Type 1 CP (ng/Klett unita) | Type 5 CP (ng/Klett unit) | ||

| 4074 | Log | 21.9 × 10−5 ± 1.5 × 10−5 | None detected | 123.5 ± 8.3 | None detected |

| 4074(pJMLCPS5) | Log | 18.4 × 10−5 ± 1.9 × 10−5 | 7.2 × 10−5 ± 0.4 × 10−5 | 79.2 ± 8.0 | 37.3 ± 2.3 |

| 4074 | Late stationary | NDb | ND | 452.0 ± 54.6 | None detected |

| 4074(pJMLCPS5) | Late stationary | ND | ND | 262.5 ± 30.3 | 216.7 ± 19.5 |

Presented for comparative purposes.

ND, viable cell numbers were not determined for cultures in late stationary phase due to the large percentage of nonviable cells.

Virulence of J45-100 and 4074(pJMLCPS5) in pigs and mice.

Strain J45-100 did not cause any pleuropneumonia-related mortality in pigs when administered at doses 3 to 36 times (1.5 × 107 to 1.8 × 108 CFU) the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of parent strain J45 (5 × 106 CFU) (Table 3). In contrast, all four of the pigs challenged with 6.6 times the LD50 of J45 died due to severe pleuropneumonia (Table 3). The five pigs challenged with the lowest dose of J45-100 (1.5 × 107 CFU) did not exhibit any clinical symptoms characteristic of swine pleuropneumonia and did not develop any lung lesions. Furthermore, A. pleuropneumoniae was not cultured from lung samples taken 4 days postchallenge at necropsy. Three of the five pigs challenged with 3 × 107 CFU of J45-100 were clinically normal, and no lung lesions were observed at necropsy. The remaining two pigs in this group exhibited mild dyspnea, and at necropsy some pleuritis and consolidation were observed (lung lesion score = 1+). A. pleuropneumoniae J45-100 was cultured only from these two pigs. There was a highly significant difference in the mortality caused by 3 × 107 CFU of J45-100 compared to a similar or lower dose of J45 (P = 0.0079). Pigs challenged with 8.4 × 107 CFU of J45-100 all had less than 10% of their lung mass affected. Nonencapsulated A. pleuropneumoniae was isolated from the lungs of each of these pigs. One pig challenged with 8.4 × 107 CFU of J45-100 died within 24 h of challenge. However, at necropsy two hemorrhagic lesions each 1 cm3 in size were observed at the injection site; less than 3% of the lung mass had pleuropneumonia-like lesions. Therefore, this pig most likely died from asphyxiation due to swelling of the trachea at the injection site. Pigs challenged with the highest dose of J45-100 (1.8 × 108 CFU, or 36 times the LD50) had 10 to 30% of the total lung mass affected, and nonencapsulated A. pleuropneumoniae was recovered from the lesions. The type of lesions in each pig varied but consisted of congestion, consolidation, and some hemorrhagic necrosis, suggesting that the lesions were due to the Apx toxins. However, this dose of J45-100 still caused significantly less mortality than the lower dose of J45 (P = 0.0286). All bacteria recovered from J45-100-infected pigs were nonencapsulated, as determined by failure to agglutinate serotype 5-specific latex beads. Thus, J45-100 did not revert to the encapsulated phenotype in vivo.

TABLE 3.

Virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae parent and recombinant strains in pigs following intratracheal challenge

| Challenge strain | Challenge dose (CFU) | Mean lung lesion score | No. positive/ total no. tested

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | Recoverya | |||

| J45 | 1.6–3.30 × 107b | 4+ | 4/4c | 4/4 |

| J45-100 | 1.5 × 107 | 0 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| J45-100 | 3.0 × 107 | 1+ | 0/5 | 2/5d |

| J45-100 | 8.4 × 107 | 1+ | 1/4e | 4/4d |

| J45-100 | 1.8 × 108 | 2+ | 0/4 | 4/4d |

| J45-Cf | 1.7 × 108 | 1+ | 0/2 | 2/2d |

| 4074 | 1.6 × 107 | 3–4+ | 6/6g | NDh |

| 4074(pJMLCPS5) | 1.8 × 107 | 3–4+ | 2/5g | ND |

Recovery of the challenge strain from lung samples taken at necropsy. Pigs challenged with J45-100 were necropsied 4 days postchallenge.

This dose is 6.6 times the LD50 (5 × 106 CFU) (20).

All of the pigs in this group died within 36 h postchallenge.

A. pleuropneumoniae was recovered from the lungs and was confirmed to be nonencapsulated by lack of iridescence and failure to agglutinate serotype 5-specific latex particles.

One pig died within 24 h postchallenge. At necropsy, two 1-cm3 hemorrhagic lesions were present at the injection site. Less than 3% of the lung mass had lesions characteristic of pleuropneumonia.

A chemically derived, nonencapsulated mutant that has been previously characterized (20).

Five of six pigs died within 20 h postchallenge with strain 4074, whereas two of five pigs challenged with strain 4074(pJMLCPS5) died within 24 h.

ND, not determined.

The virulence of strains 4074 and 4074(pJMLCPS5) was assessed in pigs by intratracheal challenge with 1.6 × 107 and 1.8 × 107 CFU, respectively, in 5 ml (Table 3). Six of six pigs challenged with parent strain 4074 died by 36 h postchallenge (five of six within 20 h). All pigs had lung lesions comprising 33 to 60% of the lung mass consistent with pleuropneumonia (consolidation, edema, and/or hemorrhage). In contrast, only two of five pigs challenged with 4074(pJMLCPS5) died, and they died within 24 h. The remaining three pigs (one pig was mischallenged and eliminated from the study) were euthanized at 72 h postchallenge and appeared clinically normal. However, all pigs challenged with strain 4074(pJMLCPS5) had lung lesions similar in degree and severity to those of pigs challenged with strain 4074. These results suggested that strain 4074(pJMLCPS5) was somewhat less virulent than parent strain 4074, but the difference in mortality was not quite significant (P = 0.06).

To reassess the virulence of 4074(pJMLCPS5), mice were inoculated with 1.2 × 107 or 1.5 × 107 CFU of 4074(pJMLCPS5) or its parent, respectively, per 40 μl. Five of six mice challenged intranasally with 4074 were bacteremic by 2.5 h after intranasal challenge (50 to 100 CFU/ml), whereas only two of six mice were bacteremic following challenge with 4074(pJMLCPS5) (≤50 CFU/ml). By 20 h postchallenge, five of six mice challenged with the parent had died. The remaining mouse had a high level of bacteremia (1.75 × 104 CFU/ml) and was euthanized. At 20 h postchallenge, only one of six mice challenged with 4074(pJMLCPS5) had died, and two of six mice were bacteremic (1.2 × 103 CFU/ml). The remaining four mice did not become bacteremic; three were clinically normal by 48 h postchallenge, and one died during phlebotomy. These results support those obtained with the pigs and indicate that 4074(pJMLCPS5) was less virulent than strain 4074. Because bacteria are in log phase in vivo, the lower virulence of isogenic strain 4074(pJMLCPS5) than of strain 4074 was likely due to its diminished amount of total CP.

DISCUSSION

A DNA region upstream from A. pleuropneumoniae J45 cpxD was cloned and sequenced. A portion of this region hybridized to genomic DNA from only A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 5 strains. This result differed from that obtained with a DNA region involved in CP export, which hybridized to all serotypes tested (54). The location of this serotype-specific A. pleuropneumoniae DNA (upstream from cpxD) is consistent with the location of serotype-specific DNA involved in CP biosynthesis in H. influenzae type b (upstream of bexD) (27, 52) and in N. meningitidis group B (upstream of ctrA) (12), providing further evidence that A. pleuropneumoniae synthesizes a group II capsule.

In general, little homology exists between the genes that encode glycosyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of structurally distinct CPs (9, 37, 38, 52). Therefore, the lack of substantial overall homology observed at the nucleotide level between cps5ABC and the sequences in the databases was expected. The low overall amino acid homology, with shared regions of higher homology, between Cps5A, Cps5B, and Cps5C and other bacterial proteins involved in carbohydrate synthesis, however, supports the premise that these proteins function in CP biosynthesis. The high homology between cps5D and the kdsA genes from other gram-negative bacteria suggests that Cps5D is the functional equivalent of the kdsA gene product required for the synthesis of dOclA. dOclA is an essential component of LPS, and it is also a component of the A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 5 CP, which has the structure [→6)-α-d-GlcpNAc-(1→5)-β-d-dOclAp-(2→]n (1).

The close proximity of cps5ABC, the identification of a putative promoter upstream of cps5A, and the lack of a potential terminator sequence between cps5ABC suggest that these ORFs are cotranscribed. The longer intergenic space between cps5C and cps5D and the presence of a promoter sequence upstream of cps5D suggest that this gene may be transcribed independently of cps5ABC, but it is unknown whether the 8-bp inverted repeat present at the downstream end of cps5C functions as a terminator sequence. The proposed dual function for dOclA in A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 5 suggests the possibility for two coexisting transcripts: a longer transcript that would include cps5ABCD for CP biosynthesis, and a shorter transcript allowing for separate expression of cps5D during LPS biosynthesis. In this case, the 8-bp inverted repeat downstream of cps5C may be nonfunctional or only partly functional, while the 8-bp inverted repeat downstream of cps5D would serve to terminate both transcripts.

The low G+C content of the DNA region encoding cps5ABC (28%) differs from the overall 42% G+C content reported for NAD-dependent strains of A. pleuropneumoniae (28) and from the G+C contents for the flanking sequences (about 40% G+C content for cpxDCBA and 42% G+C content for cps5D). These findings are similar to results obtained for the serotype-specific capsular biosynthesis region of H. influenzae type b (52) and suggest a heterologous origin for the cps5ABC genes in A. pleuropneumoniae.

CP synthesis occurs on the cytoplasmic side of the gram-negative inner membrane (56). Since the Cps5A, Cps5B, Cps5C, and Cps5D proteins are predicted to be relatively hydrophilic, it is likely that these proteins are located within the cytoplasm or associated with the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane of A. pleuropneumoniae. A cytoplasmic location for Cps5D is also consistent with the cytoplasmic location of dOclA 8-phosphate synthetase in E. coli (58).

Genetic manipulations in A. pleuropneumoniae have been difficult because of the strong restriction barrier expressed by this bacterium (10a, 23). Both electroporation and conjugation have been successfully used to transform plasmid DNA into A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1, but transformation efficiencies vary among serotypes (10, 28, 48, 55). Tascón et al. (48) developed a system for random transposon mutagenesis of the A. pleuropneumoniae genome and have used this system to construct Apx toxin-deficient mutants (49). Mulks and Buysse (32) described a targeted mutagenesis system for A. pleuropneumoniae that involved cloning the desired deletion site into a conjugative, R6K-derived, λpir-dependent suicide vector, which is introduced into A. pleuropneumoniae by filter mating. Jansen et al. (23) have succeeded in producing targeted A. pleuropneumoniae knockout mutants (lacking expression of Apx toxins) by allelic exchange with a nonreplicating plasmid vector containing the desired mutation (consisting of a deletion and/or insertion). We also used homologous recombination and allelic exchange to inactivate A. pleuropneumoniae J45 genes involved in CP biosynthesis. The production of these mutants was significant because serotype 5 is one of the more difficult A. pleuropneumoniae serotypes to transform (unpublished data; 23, 55). The medium used to grow A. pleuropneumoniae prior to electroporation with pCW11EΔ1KS1 was critical to obtaining the desired double-recombination event: nonencapsulated Kanr transformants were never obtained when A. pleuropneumoniae was grown in BHI-N (data not shown). A large proportion of the A. pleuropneumoniae Kanr transformants obtained (four of seven total in one experiment) had undergone the desired double-recombination event, and each was genotypically identical by Southern blot analyses. These results were unexpected because single-recombination events in which the entire plasmid vector integrates into the genome are more likely to occur (45). However, Jansen et al. (23) also reported a high proportion of A. pleuropneumoniae double recombinants after electroporation with a suicide vector.

J45-100 did not produce intracellular or extracellular CP. This result was expected since mutations in DNA regions involved in CP biosynthesis of N. meningitidis group B, E. coli K1, and H. influenzae type b knock out the capability of these bacteria to produce intracellular or extracellular CP (13, 43, 52). These results also indicated that cps5A, cps5B, and cps5C are involved in A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 5a CP biosynthesis. However, the exact contribution of each of these genes to the biosynthesis of the serotype 5a CP was not determined. It is important to note that J45-100 did not revert to the encapsulated phenotype in vivo in the pigs from which this strain was isolated, indicating the stability of the mutation. The only phenotypic difference between J45 and J45-100, besides CP biosynthesis, was that the generation time of J45-100 was about 5 min shorter than that of the parent. In contrast, spontaneous nonencapsulated H. influenzae type b mutants that produce, but do not export, intracellular CP grow more slowly and are highly pleomorphic (15), possibly due to the toxic accumulation of intracellular CP. These observations suggested that CP expression is a metabolically expensive process, and cells that do not make CP can use more energy for growth.

As previously reported for chemically derived nonencapsulated mutants (20, 53), J45-100 was efficiently killed in precolostral calf serum, an antibody-deficient source of complement, whereas J45 is resistant. Thus, the CP was the main determinant of serum resistance in A. pleuropneumoniae. Furthermore, J45-100 was completely avirulent in nonimmune pigs challenged intratracheally at a dose three times greater than the LD50 of parent strain J45. When pigs were challenged with J45-100 at six times the J45 LD50, three of five pigs developed mild to moderate lung lesions but did not die. It is likely that the release of tumor necrosis factor and interferons by pulmonary alveolar macrophages and neutrophils in response to endotoxin as well as direct damage to cells by exotoxins were responsible for the lung lesions that occurred at this higher challenge dose. These challenge studies demonstrated that J45-100 was significantly attenuated in pigs, further substantiating the importance of the CP to A. pleuropneumoniae virulence.

Attempts to complement J45-100 in trans with cpsABC were not successful, which we attributed to the serotype 5 restriction system. When pJMLCPS5 was electroporated into strain 4074 serotype 1 (primarily to methylate the DNA), we found that the serotype 5a CP was being expressed in addition to the serotype 1 CP. This was unexpected because the complete cps locus was not cloned into 4074; cps5D (a homolog of kdsA) was not included. Because dOclA is required for LPS biosynthesis (35, 58), a kdsA homolog must be present in 4074, which we presume was being utilized to complete biosynthesis of the serotype 5a CP. This presumption would also explain why relatively little serotype 5a CP was made by 4074(pJMLCPS5) in log phase, but greater amounts were made in stationary phase. During log phase, the kdsA gene product is required for LPS biosynthesis and cell growth (35). However, once active cell growth has stopped or slowed in late stationary phase, more of the kdsA gene product could be applied to the biosynthesis of serotype 5a CP. Why expression of cps5ABC in serotype 1 suppressed serotype 1 CP expression is not clear but may be due to end-product repression (6) or limited CP export capability.

Strains of A. pleuropneumoniae that produce more CP have been reported to be more virulent than strains producing less CP (25, 39). However, this is the first report of an isogenic strain of A. pleuropneumoniae that varies in the amount of CP produced. Strain 4074(pJMLCPS5), which produced significantly less CP in log phase than 4074, was also less virulent in pigs and mice than 4074, although due to the small number of animals used, the difference was not quite significant. In vivo, the bacteria would be in a state equivalent to log phase and produce less CP in the host, thus supporting previous reports that virulence is, in part, correlated with the amount of CP produced.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. E. Fuller for helpful discussions concerning A. pleuropneumoniae transformation. We thank John McQuiston for helping to construct pJMLCPS5 and Stephen Boyle for constructing and providing the pKS vector and technical advice, and we thank Todd Pack, Gretchen Glindemann, and Rhonda Wright for technical assistance. Thanks are given to Chris Wakley and Joe Givens for the expert care and handling of the animals used in this study. We thank Joachim Frey for Western blotting A. pleuropneumoniae concentrated culture supernatants with an ApxI-specific monoclonal antibody.

This work was supported by Hatch formula funds to the Virginia State Agricultural Experiment Station and a grant from Solvay Animal Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman E, Brisson J-R, Perry M B. Structure of the CP of Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5. Eur J Biochem. 1987;170:185–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D L. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker A, Ruberg S, Kuster H, Roxlau A A, Keller M, Ivashina T, Cheng H, Walker G C, Puhler A. The 32-kilobase exp gene cluster of Rhizobium meliloti directing the biosynthesis of galactoglucan: genetic organization and properties of the encoded gene products. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1375–1384. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1375-1384.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burrows L L, Lam J S, Lo R Y. The kdsA gene of Pasteurella trehalosi (haemolytica) serotype T3 is functionally and genetically homologous to that of Escherichia coli. J Endotoxin Res. 1996;3:353–359. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheah K-C, Manning P A. Inactivation of the Escherichia coli B41 (O101:K99/F41) rfb gene encoding an 80-kDa polypeptide results in the synthesis of an antigenically altered lipopolysaccharide in E. coli K-12. Gene. 1993;123:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90532-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen G N. Regulation of enzyme activity in microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1965;19:105–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.19.100165.000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devendish J, Rosendal S, Johnson R, Hubler S. Immunoserological comparison of 104-kilodalton proteins associated with hemolysis and cytolysis in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Actinobacillus suis, Pasteurella haemolytica, and Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3210–3213. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.10.3210-3213.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dower W J, Miller J F, Ragsdale C W. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6127–6145. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards U, Müller A, Hammerschmidt S, Gerardy-Schahn R, Frosch M. Molecular analysis of the biosynthesis pathway of the -2,8 polysialic acid capsule by Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:141–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frey J. Construction of a broad host range shuttle vector for gene cloning and expression in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and other Pasteurellaceae. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:263–269. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90018-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Frey, J. Personal communication.

- 11.Frey J, van den Bosch H, Segers R, Nicolet J. Identification of a second hemolysin (HlyII) in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 and expression of the gene in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1671–1676. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1671-1676.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frosch M, Edwards U, Bousset K, Krausse B, Weisgerber C. Evidence for a common molecular origin of the capsule gene loci in gram-negative bacteria expressing group II CPs. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1251–1263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frosch M, Weisgerber C, Meyer T F. Molecular characterization and expression in Escherichia coli of the gene complex encoding the polysaccharide capsule of Neisseria meningitidis group B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1669–1673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawley D K, McClure W R. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:2237–2255. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.8.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoiseth S K, Connelly C J, Moxon E R. Genetics of spontaneous, high-frequency loss of b capsule expression in Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1985;49:389–395. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.389-395.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inzana T J. Electrophoretic heterogeneity and inter-strain variation of the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:492–499. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inzana T J. Purification and partial characterization of the capsular polymer of Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1573–1579. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.7.1573-1579.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inzana T J. Simplified procedure for preparation of sensitized latex particles to detect capsular polysaccharides: application to typing and diagnosis of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2297–2303. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2297-2303.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inzana T J, Mathison B. Serotype specificity and immunogenicity of the capsular polymer of Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1580–1587. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.7.1580-1587.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inzana T J, Todd J, Veit H P. Safety, stability, and efficacy of noncapsulated mutants of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae for use in live vaccines. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1682–1686. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1682-1686.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inzana T J, Ma J, Workman T, Gogolewski R P, Anderson P. Virulence properties and protective efficacy of the capsular polymer of Haemophilus (Actinobacillus) pleuropneumoniae serotype 5. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1880–1889. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1880-1889.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ish-Horowicz D, Burke J F. Rapid and efficient cosmid cloning. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:2989–2998. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.13.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansen R, Briaire J, Smith H E, Dom P, Haesebrouck F, Kamp E M, Gielkens A L J, Smits M A. Knockout mutants of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 that are devoid of RTX toxins do not activate or kill porcine neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1995;63:27–37. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.27-37.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jedani K E, Stroeher U H, Manning P A. Vibrio anguillarum rfb region, partial sequence. 1997. Direct submission, nonredundant GenBank CDS. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen A E, Bertram T A. Morphological and biochemical comparison of virulent and avirulent isolates of Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5. Infect Immun. 1986;51:419–424. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.2.419-424.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang X, Neal B, Santiago F, Lee S J, Romana L K, Reeves P R. Structure and sequence of the rfb (O antigen) gene cluster of Salmonella serovar typhimurium (strain LT2) Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:695–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroll J S, Loynds B, Brophy L N, Moxon E R. The bex locus in encapsulated H. influenzae: a chromosomal region involved in capsule polysaccharide export. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1853–1862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lalonde G, Miller J F, Tompkins L S, O’Hanley P. Transformation of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and analysis of R factors by electroporation. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50:1957–1960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin W S, Cunneen T, Lee C Y. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of genes required for the biosynthesis of type 1 capsular polysaccharide in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7005–7016. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7005-7016.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo T M, Ward C K, Inzana T J. Detection and identification of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5 by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1704–1710. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1704-1710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma J, Inzana T J. Indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibody to a 110,000-molecular-weight hemolysin of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1356–1361. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1356-1361.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulks M H, Buysse J M. A targeted mutagenesis system for Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Gene. 1995;165:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00528-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen R. Serological characterization of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae strains and proposal of a new serotype: serotype 12. Acta Vet Scand. 1986;27:452–455. doi: 10.1186/BF03548158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelczar M J, Jr, Chan E C S, Krieg N R. Microbiology: concepts and applications. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill Inc.; 1993. pp. 189–190. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raetz C R H. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: a remarkable family of bioactive macroamphiphiles. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtis III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1035–1063. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ried J L, Collmer A. An nptI-sacB-sacR cartridge for constructing directed, unmarked mutations in gram-negative bacteria by marker exchange-eviction mutagenesis. Gene. 1987;57:239–246. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts I, Mountford R, High N, Bitter-Suermann D, Jann K, Timmis K, Boulnois G. Molecular cloning and analysis of genes for production of K5, K7, K12, and K92 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1228–1233. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1228-1233.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts I S, Mountford R, Hodge R, Jann K, Boulnois G J. Common organization of gene clusters for production of different capsular polysaccharides (K antigens) in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1305–1310. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1305-1310.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosendal S, MacInnes J I. Characterization of an attenuated strain of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1. Am J Vet Res. 1990;51:711–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shine J, Dalgarno L. The 3′ terminal sequence of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA: complementarity to nonsense triplets and the ribosome binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1342–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silver R P, Vann W F, Aaronson W. Genetic and molecular analyses of Escherichia coli K1 antigen genes. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:568–575. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.568-575.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stibitz S. Use of conditionally counterselectable suicide vectors for allelic exchange. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:458–465. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stingele F, Neeser J, Mollet B. Identification and characterization of the eps (exopolysaccharide) gene cluster from Streptococcus thermophilus Sfi6. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1680–1690. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1680-1690.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tartof K D, Hobbes C A. Improved media for growing plasmid and cosmid clones. Bethesda Res Lab Focus. 1987;9:12. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tascón R I, Rodríguez-Ferri E F, Gutiérrez-Martín C B, Rodríguez-Barbosa I, Berche P, Vázquez-Boland J A. Transposon mutagenesis in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae with a Tn10 derivative. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5717–5722. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5717-5722.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tascón R I, Vázquez-Boland J A, Gutiérrez-Martín C B, Rodríguez-Barbosa I, Rodríguez-Ferri E F. The RTX haemolysins ApxI and ApxII are major virulence factors of the swine pathogen Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae: evidence from mutational analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tatusov R L, Mushegian A R, Bork P, Brown N P, Hayes W S, Borodovsky M, Rudd K E, Koonin E V. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsai C-M, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Eldere J, Brophy L, Loynds B, Celis P, Hancock I, Carman S, Kroll J S, Moxon E R. Region II of the Haemophilus influenzae type b capsulation locus involved in serotype-specific polysaccharide synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:107–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ward C K, Inzana T J. Resistance of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae to bactericidal antibody and complement is mediated by CP and blocking antibody specific for lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1994;153:2110–2121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ward C K, Inzana T J. Identification and characterization of a DNA region involved in the export of capsular polysaccharide by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5a. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2491–2496. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2491-2496.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.West S E H, Romero M J M, Regassa L B, Zielinski N A, Welch R A. Construction of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors: expression of antibiotic resistance genes. Gene. 1995;160:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00236-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whitfield C, Valvano M A. Biosynthesis and expression of cell-surface polysaccharides in gram-negative bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol. 1993;35:135–246. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Willson P J, Albritton W L, Slaney L, Setlow J K. Characterization of a multiple antibiotic resistance plasmid from Haemophilus ducreyi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1627–1630. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woisetschlager M, Hogenauer G. The kdsA gene coding for 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid 8-phosphate synthetase is part of an operon in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;207:369–373. doi: 10.1007/BF00331603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhen L, Swank R T. A simple and high yield method for recovering DNA from agarose gels. BioTechniques. 1993;14:894–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]