Significance

This study demonstrates the efficacy of combining macrophage-checkpoint inhibition with granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell (G-MDSC) targeting as a strategy for cancer immunotherapy. While CD47 blockade or CXCR2 inhibition alone were not significantly effective in combating tumor progression as single-agent therapies, their combination resulted in an enhanced anti-tumor effect. Through the inhibition of G-MDSCs immunosuppressive contributions to microenvironment, this dual-treatment strategy boosts macrophages immune response against cancer cells and delays tumor progression. We believe that these findings present a promising therapeutic approach for treating a wide range of solid tumors in which both tumor-associated macrophages and G-MDSCs are present.

Keywords: myeloid-derived suppressor cells, CXCR2, macrophages, CD47 blockade, tumor immunology

Abstract

The use of colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibitors has been widely explored as a strategy for cancer immunotherapy due to their robust depletion of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). While CSF1R blockade effectively eliminates TAMs from the solid tumor microenvironment, its clinical efficacy is limited. Here, we use an inducible CSF1R knockout model to investigate the persistence of tumor progression in the absence of TAMs. We find increased frequencies of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (G-MDSCs) in the bone marrow, throughout circulation, and in the tumor following CSF1R deletion and loss of TAMs. We find that G-MDSCs are capable of suppressing macrophage phagocytosis, and the elimination of G-MDSCs through CXCR2 inhibition increases macrophage capacity for tumor cell clearance. Further, we find that combination therapy of CXCR2 inhibition and CD47 blockade synergize to elicit a significant anti-tumor response. These findings reveal G-MDSCs as key drivers of tumor immunosuppression and demonstrate their inhibition as a potent strategy to increase macrophage phagocytosis and enhance the anti-tumor efficacy of CD47 blockade in B16-F10 melanoma.

Over the last decade, advances in immunology have revolutionized cancer treatment and have reignited the field of cancer immunotherapy. Despite numerous clinical successes, many patients demonstrate varying responses to immunotherapies, and some types of cancers show almost complete resistance (1, 2). While most efforts have focused on T cell-mediated therapies, understanding the role of the innate immune system in regulating tumor progression has now come into sharper focus (3–5).

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are two central groups of myeloid cells that represent a major component of the tumor microenvironment in a variety of cancers (6, 7). Both TAMs and MDSCs have been well described for their immunosuppressive properties, and their frequencies in tumors can be correlated with poor prognosis and therapeutic resistance (8–12). Therefore, efforts to modulate the myeloid compartment of the tumor microenvironment are now being explored for cancer immunotherapy.

One such immunotherapy focuses on targeting colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF1R), a class III protein tyrosine kinase receptor expressed on cells belonging to the mononuclear phagocyte lineage (13). Binding of CSF1 or IL-34 ligands activates signaling that is crucial for macrophage development, differentiation, and survival (14, 15). Thus, the inhibition of TAM proliferation and survival through CSF1R blockade has gained significant interest as a strategy for cancer immunotherapy.

CSF1R inhibition with small molecule antagonists such as PLX3397, GW2580, JNJ-40346527, and BLZ945, or monoclonal antibodies such as 5A1 and M279, demonstrates robust reductions of tissue-resident macrophages and TAMs in pre-clinical models and in the clinic (16–23). However, the reported effects of TAM depletion by CSF1R inhibitors in these studies show minimal anti-tumor efficacy and limited therapeutic benefits. Because CSF1R inhibition lacks efficacy as a single agent therapy in many cancer models, efforts have shifted toward its potential in combination therapies, such as with PD-1 or CTLA-4 checkpoint blockade (24). Although some anti-tumor efficacy is observed in combination with these immune checkpoint inhibitors, the clinical utility of TAM depletion requires deeper investigation, as the mechanisms that regulate tumor progression with CSF1R inhibition are not completely understood.

While the elimination of TAMs is one possible strategy for therapeutic intervention, we and others have focused on exploiting the innate properties of certain macrophages to mediate anti-tumor activity. Such strategies include modulation or blockade of anti-phagocytic inhibitory signals expressed by cancer cells, such as CD47, PD-1, LILRB1, and CD24, to allow for recognition and phagocytosis by macrophages (25–31). The effective anti-tumor responses observed with macrophage checkpoint blockade, either as single agents or as combination therapies, demonstrate the utility of macrophages for tumor cell elimination. Given the dual role of macrophages in tumors, it is critical that we further our understanding of their contribution to tumor progression as we aim to develop effective myeloid-targeted immunotherapies.

Here, we developed an inducible CSF1R knockout mouse model to identify the mechanisms that allow tumor progression to persist in the absence of TAMs. Upon deletion of CSF1R and the subsequent loss of macrophages, we observed accelerated tumor progression of B16-F10 melanoma. We discovered increased frequencies of CXCR2+ granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (G-MDSCs) in the bone marrow, throughout circulation, and in the tumor after CSF1R deletion, suggesting their ability to drive tumor progression in a setting of TAM depletion. Our data also reveal that G-MDSCs can suppress the phagocytic functions of macrophages and that inhibition of G-MDSCs using a CXCR2 antagonist can restore phagocytosis. Further, we find that CXCR2 inhibition and CD47 blockade can work synergistically to generate a robust anti-tumor response. Through this study, we identify a possible combination immunotherapy that increases macrophage clearance of tumor cells in the presence of CD47 blockade via the disruption of G-MDSC recruitment.

Results

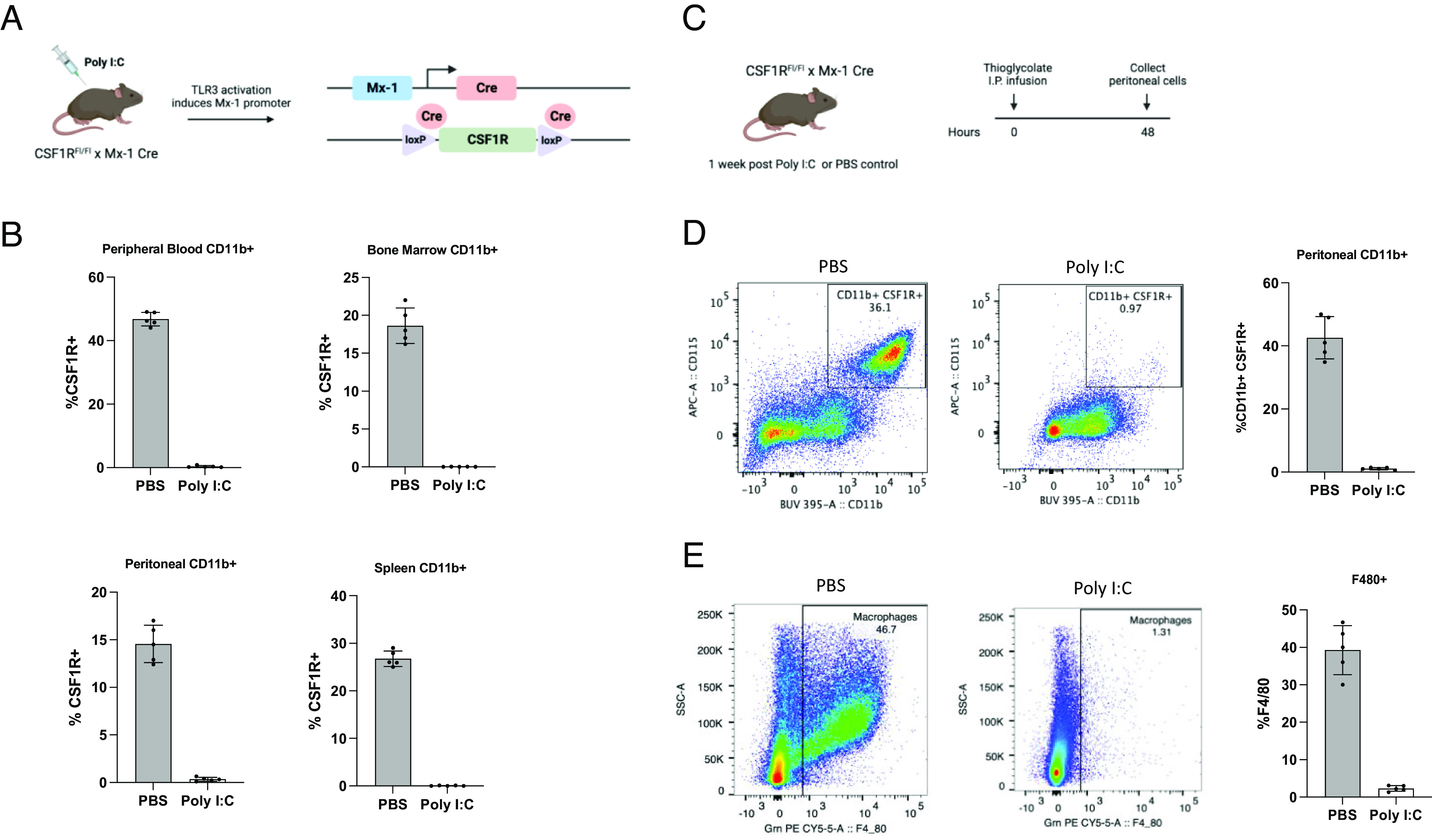

Generation and Validation of Inducible CSF1R Knockout Mice.

Therapeutic approaches to inhibit CSF1R or its ligands, CSF1/IL-34, include the use of various modalities, such as monoclonal antibodies and small molecular antagonists. While these approaches aim to target TAMs, CSF1R inhibitors have also been shown to directly target tumor cells in some cancer models (32, 33). Deletion of the CSF1R locus in the mouse and rat germline results in a significant reduction of tissue-resident macrophages, but CSF1R−/− mice suffer significantly impaired postnatal growth, become osteoporotic, and rarely survive adulthood (34). Therefore, to overcome these limitations, we developed an inducible CSF1R knockout mouse line. CSF1RFl/Fl mice were crossed with Mx1-Cre mice, in which the Mx-1 promoter is activated following intraperitoneal injection of Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly I:C), a TLR3 agonist (Fig. 1A). To validate deletion of CSF1R, CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice were treated with Poly I:C and were allowed to rest for 1 wk to allow their interferon response to subside. Peripheral blood, bone marrow, peritoneal cells, and spleen were then harvested and subjected to flow cytometry for analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). Loss of CSF1R was observed on CD11b+ cells, validating its deletion following administration of Poly I:C.

Fig. 1.

Inducible deletion of CSF1R in CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice. (A) Mating scheme by which inducible CSF1R knockout mice were generated and diagram illustrating the induction of Cre expression and subsequent recombination after Poly I:C administration. (B) CSF1R cell surface expression gated on CD11b+ cells within peripheral blood, bone marrow, peritoneum, and spleen in CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice 1 wk after Poly I:C or PBS treatment (n = 5 mice per group). (C) Schematic depicting experimental timeline. CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice received three intraperitoneal injections of Poly I:C (100 μg) and were rested for 1 wk. Control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice were then infused intraperitoneally with thioglycolate broth. Peritoneal cells were harvested 48 h following thioglycolate broth infusion. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots and bar graphs of CSF1R expression on CD11b+ peritoneal cells 48 h after thioglycolate broth infusion in control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice (n = 5 mice per group). (E) Representative flow cytometry plots and bar graphs of F4/80+ macrophages 48 h after thioglycolate broth infusion in control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice (n = 5 mice).

Under steady-state conditions, the mouse peritoneal cavity contains a population of tissue-resident macrophages (35). In models of sterile inflammation, such as the induction of peritonitis by thioglycolate, monocytes from the periphery are rapidly recruited to the peritoneum where they differentiate into macrophages (36, 37). To determine whether macrophages could be generated from recruited monocytes after CSF1R deletion, control or Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice were infused with thioglycolate IP, and peritoneal cells were harvested 48 h later for flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 1C). Deletion of CSF1R was observed to be maintained on CD11b+ cells recruited to the peritoneum in CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice that were treated with Poly I:C (Fig. 1D). Further, a significant decrease in F4/80+ peritoneal macrophages was found in Poly I:C-treated mice compared to control mice (Fig. 1E).

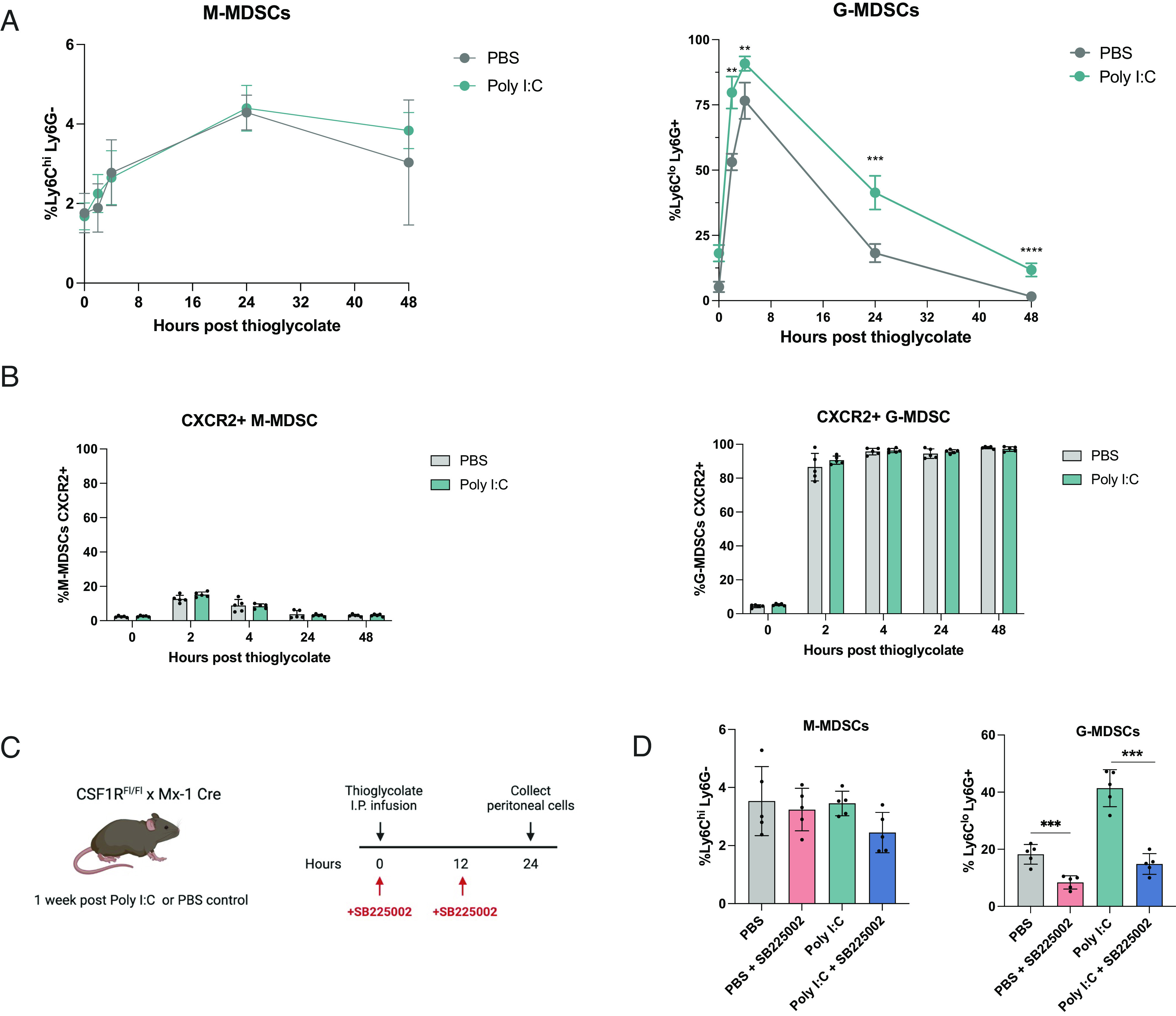

Deletion of CSF1R Leads to Increased CXCR2+ G-MDSCs in Thioglycolate-Induced Peritonitis.

We next examined the CD11b+ compartment to determine whether CSF1R deletion affected the inflammatory response and recruitment of other myeloid cells after thioglycolate infusion. Peritoneal cells were harvested at 0, 2, 4, 24, and 48 h and subjected to flow cytometry for analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A and Fig. 2A). At each time point, Ly6CloLy6G+ cells (G-MDSCs) were found to be significantly increased in Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice compared to control, whereas no differences were observed in Ly6Chi Ly6G− cells (M-MDSCs).

Fig. 2.

Thioglycolate treatment leads to increased CXCR2+ G-MDSCs in CSF1R deletion mice. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of M-MDSCs (CD11b+ Ly6ChiLy6G−) and G-MDSCs (CD11b+ Ly6CloLy6G+) gated on CD11b cells after thioglycolate infusion in control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice. Peritoneal cells were collected and subjected to flow cytometry analysis at 0, 2, 4, 24, and 48 h after thioglycolate infusion (n = 5 mice per group). (B) Flow cytometry analysis of CXCR2 expression on peritoneal G-MDSCs and M-MDSCs of control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice (n = 5 mice). Peritoneal cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometry analysis at 0, 2, 4, 24, and 48 h after thioglycolate infusion (n = 5 mice per group). (C) Schematic showing experimental timeline. Control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice were infused with thioglycolate. Mice were either treated with PBS or 2 mg/kg SB225002 at 0 and 12 h. Peritoneal cells were harvested at 24 h. (D) Peritoneal M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs harvested 24 h after thioglycolate infusion and analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 5 mice per group). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001.

The CXCR2/CXCL1 signaling axis has been shown to regulate the migration and recruitment of G-MDSCs (38, 39). To determine whether Ly6CloLy6G+ G-MSDCs recruited into the peritoneum expressed CXCR2, we subjected peritoneal cells to flow cytometry analysis over the course of 48 h after thioglycolate infusion. G-MDSCs were found to highly express CXCR2, while expression was much lower on M-MDSCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B and Fig. 2B).

Since G-MDSCs have been well described as potent suppressors in inflammation and cancer, we next sought to determine whether the recruitment of CXCR2+ G-MDSCs could be inhibited. At the time of thioglycolate infusion, mice also received a dose of SB225002, a CXCR2 inhibitor. Mice were then dosed with SB225002 again at 12 h, and peritoneal cells were harvested at 24 h for flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 2 C and D). Treatment with SB225002 demonstrated significant decreases in G-MDSCs in the peritoneal cavity of control and Poly I:C-treated mice.

CSF1R Deletion Leads to Increased CXCR2+ G-MDSCs in B16-F10 Melanoma.

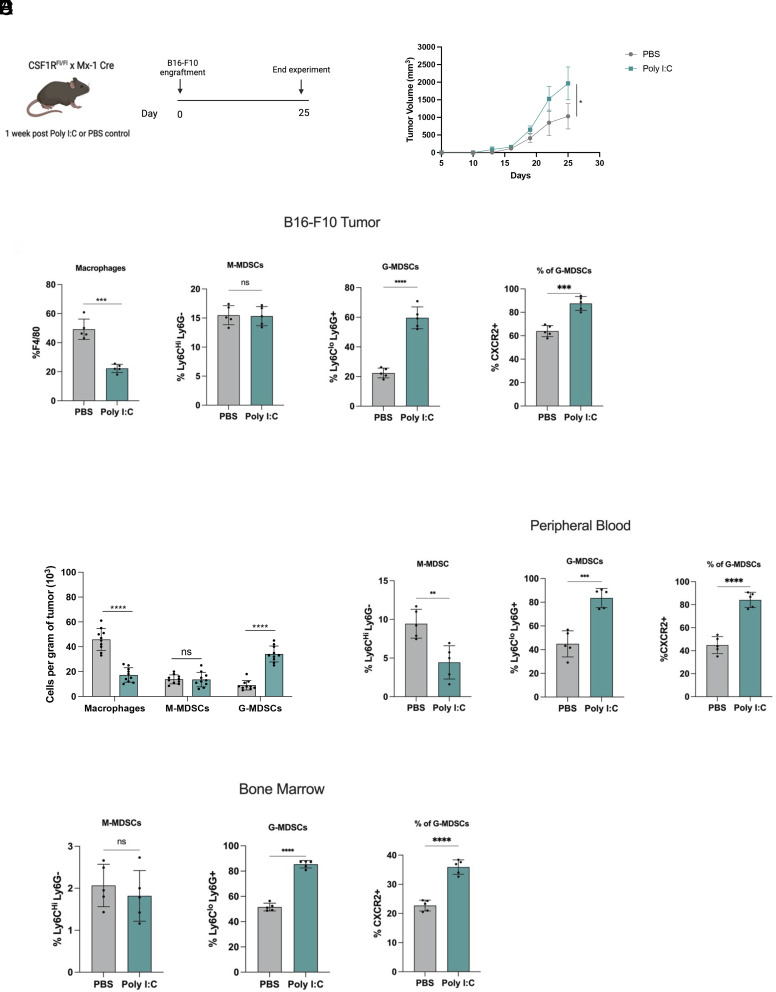

To determine whether deletion of CSF1R affects tumor progression in this model, B16-F10 melanoma tumor cells were engrafted subcutaneously into PBS or Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice and tumor growth was measured over time (Fig. 3A). Following engraftment, tumor volumes were measured every other day for the duration of the study, and Poly I:C-treated mice exhibited significantly larger tumors compared to control mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

CXCR2+ G-MDSCs are increased in B16-F10 melanoma tumor-bearing mice. (A) Schematic showing experimental design and timeline. CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice received three intraperitoneal injections of PBS or Poly I:C (100 μg) and were rested for 1 wk. 5 × 105 B16-F10 mouse melanoma cells were then subcutaneously engrafted into flanks of mice. (B) Measured tumor burden of B16-F10 melanoma in control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice. Tumor size was measured every two days (n = 5 mice per group). (C) Flow cytometry analysis and bar graphs of tumor B16-F10 tumors from control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice. F4/80+ macrophages are gated on CD45+ cells. M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs are gated on CD45+ CD11b+ cells. CXCR2 expression on CD45+ CD11b+ G-MDSCs. (n = 5 mice per group). (D) The absolute number of myeloid cells per gram of tumor of control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice. (E and F) Flow cytometry analysis and bar graphs of peripheral blood and bone marrow of tumor-bearing mice. M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs are gated on CD45+ CD11b+ cells. CXCR2 is gated on CD45+ CD11b+ G-MDSCs (n = 5 mice per group). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001.

To identify whether increased G-MDSC recruitment could also be observed in tumors of CSF1R deficient mice, tumors were subjected to immunophenotyping by flow cytometry. As expected, CD11b+ CSF1R+ myeloid cells and F4/80+ TAMs were significantly reduced in tumors of CSF1R deficient mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A and Fig. 3C). While no significant differences were observed in M-MDSCs, CXCR2+ G-MDSCs were found to be significantly increased in Poly I:C-treated mice. Additionally, an increase in the absolute numbers of G-MDSCs adjusted to tumor weight could be observed in tumors of Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice (Fig. 3D). Increased CXCR2+ G-MDSCs were also found in the bone marrow and peripheral blood of CSF1R deficient tumor-bearing mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and C and Fig. 3 E and F). Tumors in control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice did not show significant differences in T cell, B cell, and NK cell populations (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D).

Inhibition of CXCR2+ G-MDSCs Delays Tumor Progression in B16-F10 Melanoma.

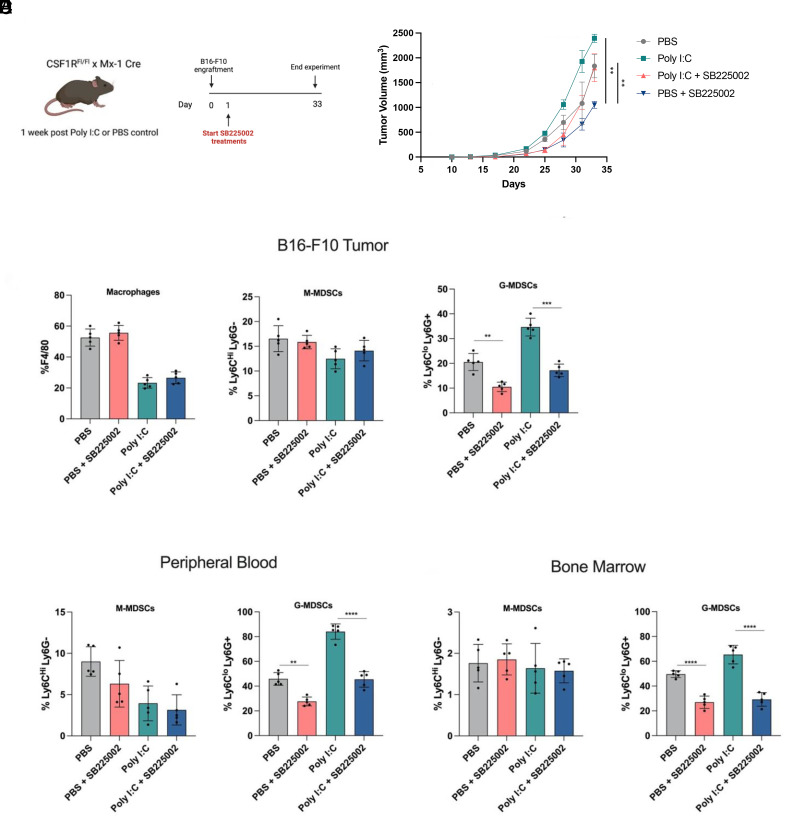

To determine whether targeting CXCR2+ G-MDSCs could lead to an anti-tumor response, control or Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice were subcutaneously engrafted with B16-F10 melanoma tumor cells. The day after engraftment, mice were dosed IP with PBS or SB225002 6 d per week until mice were killed (Fig. 4A). Tumor growth was measured over time, and SB225002 was found to significantly reduce tumor progression in both control and Poly I:C-treated mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

CXCR2 inhibition decreases G-MDSC tumor infiltration and delays tumor progression. (A) Schematic showing experimental design and timeline. CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice received three intraperitoneal injections of Poly I:C (100 μg) or control PBS and were rested for 1 wk. 5 × 105 B16-F10 mouse melanoma cells were then subcutaneously engrafted into flanks of mice. Following the day of engraftment, mice were either untreated or treated daily with 2 mg/kg SB225002. (B) Measured tumor burden of B16-F10 melanoma in control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice treated with or without SB225002. Tumor size was measured every 2 d (n = 5 mice per group). (C) Flow cytometry analysis and bar graphs of tumor B16-F10 tumors from control and Poly I:C-treated CSF1RFl/Fl-Mx1-Cre mice treated with or without SB225002. F4/80+ macrophages are gated on CD45+ cells. M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs are gated on CD45+ CD11b+ cells (n = 5 mice per group). (D and E) Flow cytometry analysis and bar graphs of peripheral blood and bone marrow of tumor-bearing mice. M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs are gated on CD45+ CD11b+ cells (n = 5 mice per group). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001.

To investigate the effect of SB225002 treatment on immune infiltration, tumors were harvested and subjected to flow cytometry for immunophenotyping (Fig. 4C). The frequency of F4/80+ macrophages was not affected by CXCR2 inhibition, but a significant decrease in tumor-infiltrating CXCR2+ G-MDSCs was observed in SB225002-treated mice. Further, a significant decrease of G-MDSCs was found in the bone marrow and peripheral blood of tumor-bearing mice treated with the CXCR2 inhibitor (Fig. 4 D and E).

Inhibition of G-MDSCs Promotes Macrophage Phagocytosis and Enhances the Anti-tumor Efficacy of CD47 Blockade in B16-F10 Melanoma.

Previous studies have demonstrated the capacity for both G-MDSCs and M-MDSCs to dampen inflammatory responses by the immune system through various mechanisms (40–43). However, their direct abilities to influence macrophage function require investigation. Here, we sought to determine whether CXCR2+ G-MDSCs are capable of suppressing macrophage phagocytosis.

Thioglycolate was infused IP into wild-type C57BL6 mice who then received two doses of SB255002 or PBS at 0 h and at 12 h to deplete G-MDSCs in the peritoneal cavity. B16-F10 melanoma cells, previously shown to be relatively resistant to anti-CD47 mAb induced tumor cell reduction in vivo, were either pre-treated with control mouse IgG1 or anti-CD47 mAb, labeled with cell trace CFSE, and injected IP into the mice (Fig. 5A). Peritoneal cells were recovered after 4 h, and phagocytosis by CD11b+ macrophages was measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 5B). Macrophages from mice that received SB225002 treatments and anti-CD47 pre-treated B16-F10 cells demonstrated increased phagocytic capacity.

Fig. 5.

Macrophage tumor clearance of B16-F10 melanoma increases with CXCR2 inhibition and CD47 blockade. (A) Experimental schematic of in vivo phagocytosis assay. C57BL6 mice were infused with thioglycolate to recruit macrophages and G-MDSCs to the peritoneum. Mice were either untreated or treated with SB225002 at time of thioglycolate infusion and again 12 h later. Twenty-four hours following initial thioglycolate infusion, CFSE labeled B16-F10 cells pre-treated with IgG1 or anti-CD47 cells were injected intraperitoneally into mice. (B) Flow cytometry analysis to determine phagocytosis of CFSE-labeled B16-F10 cells by peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal cells were harvested by lavage 4 h after B16-F10 injection and were stained with anti-CD11b. Phagocytosis was determined by percentage of macrophages that were also CFSE+ (n = 5). (C–F) C57BL6 or NSG mice were subcutaneously engrafted with 5 × 105 B16-F10 mouse melanoma cells. The following day, mice began receiving treatments: daily treatments of 2 mg/kg SB225002, three 100 μg priming doses of control IgG1 (MOPC21) or anti-CD47 (MIAP410) given every other day, followed by 300 μg of control IgG1 or anti-CD47 every other day. (C–E) Measured tumor burden of B16-F10 melanoma in C57BL6 mice and survival analysis of treated with IgG1 (100 μg every other day, 100 μg anti-CD47 every other day, 2 mg/kg SB25002 daily, or in combination). (E and F) Measured tumor burden of B16-F10 melanoma in NSG mice and survival analysis (n = 5 mice per group), *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. Survival P value was computed by a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

To determine whether the combination of CXCR2 inhibition by SB225002 and anti-CD47 mAb therapy could lead to an enhanced anti-tumor response in vivo, wild-type C57BL6 mice were subcutaneously engrafted with B16-F10 melanoma, and tumors were measured over time. SB225002 and anti-CD47 combined therapy demonstrated a significantly robust anti-tumor response compared to SB225002 or anti-CD47 alone (Fig. 5C). Additionally, the combination group demonstrated increased survival compared to other treatment groups (Fig. 5D). NSG mice engrafted with B16-10 melanoma also demonstrated a similar trend in response to combination therapy and significantly increased survival compared to single agent therapies. (Fig. 5 E and F). This study implicates G-MDSCs as part of the mechanism of the resistance of this melanoma to anti-CD47 mAb immunotherapy in vivo.

Discussion

The data presented here reveal that loss of macrophages via CSF1R deletion leads to increased production and recruitment of CXCR2+ G-MDSCs in inflammation and in a syngeneic tumor model of B16-F10 melanoma. Thus, we have uncovered a possible pathway by which tumor growth may persist in the absence of macrophages or in CSF1R inhibition therapy: through the influx of G-MDSCs in both the primary tumor site, as well as throughout circulation.

While TAMs have been shown to constitute up to 50% of the mass of human tumors, other infiltrating myeloid cells, such as neutrophils and MDSCs, can facilitate tumor growth and dampen anti-tumor immunity, such as through inhibition of T cell responses (44–46). These data, as well as findings from previous studies, highlight the central role of G-MDSCs in driving tumor progression.

Since previous studies have shown the CXCR2/CXCL1 signaling axis to be important for G-MDSC recruitment, we used a small-molecule antagonist of CXCR2 to attenuate the recruitment of G-MDSCs into tumors of CSF1R deletion and control mice. Our findings show that while CXCR2 inhibition alone can significantly decrease G-MDSC tumor infiltration in both groups, a greater anti-tumor response can be achieved in a setting where TAMs persist and CD47 blockade is administered. While CXCR2 inhibition has previously been shown to be an effective therapeutic for several cancer models, our data suggest that this elimination of G-MDSCs may in part relieve tumor immunosuppression and promote macrophage function, which may also be in part due to downregulation of fibroblast-mediated chemokine production (47–53). In turn, the presence of macrophages in the tumor is correlated with a lack of G-MDSCs. Currently, it is not clear whether this is an association or a function of macrophages.

While studies have shown the ability for MDSCs to suppress T cell responses, the ability for G-MDSCs to suppress macrophage function, such as phagocytosis of tumor cells, has not been shown. Given the plasticity of macrophages, it is conceivable that G-MDSCs may dampen their function and further reinforce a TAM or suppressive phenotype. We found, through an in vivo phagocytosis assay, that elimination of G-MDSCs from the peritoneum increases phagocytosis of tumor cells by peritoneal macrophages, and pre-treatment of B16-F10 tumor cells with anti-CD47 led to further increased levels of phagocytosis. C57BL6 mice subcutaneously engrafted with B16-F10 melanoma demonstrated resistance to anti-CD47 therapy alone, which has also been observed in previous studies. While CXCR2 inhibition achieved modest levels of delayed tumor progression, a more significant anti-tumor response could be achieved when CD47 blockade and CXCR2 inhibition therapy were combined. Together, these data suggest that G-MDSCs may inhibit macrophage phagocytosis, and eliminating G-MDSCs may restore macrophages’ abilities to clear tumor cells. Moreover, relieving tumor immunosuppression by targeting G-MDSCs can enhance the effects of CD47 blockade.

In summary, we demonstrate that depletion of macrophages from the tumor microenvironment leads to expansion and increased infiltration of G-MDSCs, which may be in part responsible for tumor progression in the absence of TAMs. Inhibition of CXCR2+ G-MDSCs in combination with CD47 mAb therapy may be an ideal approach for selectively abrogating G-MDSC trafficking into tumors while restoring macrophage phagocytosis of tumor cells. Because of G-MDSCs’ suppressive effects on various immune cells, further investigation is needed on the possible benefits of CXCR2 inhibition in combination with other immunotherapies and in other cancer models. It is important to note that although mouse MDSCs have been described as CD11b+ Ly6C+Ly6G− for M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs as CD11b+ Ly6CloLy6G+, these markers can also be expressed by mature monocytic and neutrophil subsets (54, 55). Future studies should also determine whether these populations possess suppressive activities to more accurately characterize and define them.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57Bl6/J mice, B6.Cg-Csf1rtm1.2Jwp/J (Csf1rfl/f) mice, and B6.Cg-Tg(Mx1-cre) 1Cgn/J mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice were obtained from in-house breeding stocks. Mice were bred and maintained at the Stanford University Research Animal Facility. All experiments were carried out in accordance with ethical care guidelines set by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care (APLAC). All experiments performed included male and female mice.

Cell Culture and Reagents.

B16-F10 murine melanoma cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and were cultured in DMEM+GlutaMax + 10% fetal bovine serum + 100 U ml−1 penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were cultured in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. SB225002 was purchased from Tocris (Cat. No. 2725) and Poly I:C HMW was obtained from Invivogen (tlrl-pic). Anti-CD47 MIAP410 (Cat. No. BE0283) and anti-IgG1 MOP-C21 (Cat. No. BE0083) were purchased from BioXCell.

Flow Cytometry.

Samples were blocked with monoclonal antibody to CD16/32 (TruStain fcX, BioLegend) before staining with antibody panels. Samples were stained for 30 min on ice and subsequently washed with FACS buffer (PBS with 1% FBS buffer). Fluorescence compensations were performed using single-stained UltraComp eBeads (Invitrogen). The following antibodies were used for FACS analysis: Anti-CD11b (M1/70 BD Biosciences); Anti-F4/80 (BM8 BioLegend); Anti-Ly6G (1A8 BioLegend), Anti-Ly6C (HK1.4 BioLegend); Anti-CXCR2 (SA044G4 BioLegend), Anti-CD45 (30-F11 BioLegend), Anti-CSF1R (AFS98 BioLegend), Anti-B220 (RA3-8B2 BD Biosciences), Anti-CD8a (53-6.7 BD Biosciences), Anti-CD4 (RM4-5 BioLegend), and Anti-NK1.1 (PK136 BioLegend). SYTOX blue dead cell stain (Invitrogen) was used for dead cell exclusion. CountBright Absolute Counting Beads (Thermo) were used to determine absolute cell count. Data were acquired using a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software.

Thioglycolate-Induced Peritonitis and Isolation of Peritoneal Cells.

Peritoneal lavage was performed at indicated times after intraperitoneal injection of 1 mL of 3% thioglycolate medium (Difco). Cells were resuspended in FACS buffer and were stained with antibodies as previously described for flow cytometry analysis.

In Vivo Tumor Experiments and Treatments.

Mice 6 to 8 wk of age were given subcutaneous injection of 5 × 105 B16-F10 melanoma cells in PBS into the right flank. Tumor growth was measured by using calipers, and volumes were calculated by using the formula: volume= 4/3π × (x/2)2 × (y/2), where x is the largest measurable dimension of the tumor and y is the dimension immediately perpendicular to x. Tumor volumes were evaluated using two-way ANOVA in GraphPad Prism. For tumor treatments, mice were given mouse IgG1 isotype control clone MOPC21 (BioXCell), anti-CD47 mAb clone MIAP410 (BioXCell), and SB225002 2 mg/kg (Tocris) by intraperitoneal injection. Single-cell suspensions of solid tumor specimens were obtained by mechanical dissociation using a straight razor, followed by enzymatic digestion in RPMI + 10 μg mL−1 DNaseI (Sigma-Aldrich) + 25 μg mL−1 Liberase (Roche) for 30 to 60 min shaking at 37 °C. Tumor cells were filtered through 100-μm filters and resuspended in ACK Lysing Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 5 min at room temperature to lyse red blood cells.

In Vivo Phagocytosis Assay.

B16-F10 melanoma cells were labeled with CellTrace CFSE (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. CFSE labeled B16-F10 cells were incubated with IgG1 isotype control or anti-CD47 (MIAP410) for 20 min on ice and washed with PBS. Then, 1 × 106 labeled cells were subsequently injected into the peritoneal cavity of C57BL6 mice. Four hours after the injections, mice were killed, and cells were harvested by peritoneal lavage. Peritoneal macrophages were stained with anti-CD11b for 30 min on ice and washed with FACS buffer. Phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry.

Statistical Analysis and Graphing Software.

All data were collected and statistically analyzed with GraphPad Prism software.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda Quinn, Teja Naik, and Aaron McCarty for technical assistance. We thank Catherine Carswell-Crumpton and Cheng Pan for flow cytometry assistance. This research was supported by the Ludwig Cancer Foundation and NIH/NCI Outstanding Investigator Award R35CA220434 (to I.L.W.), the Stanford Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine Training Grant T32GM119995 (to A.B.), the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Training award (to H.B., M.B., and N.G.), and the Stanford Bio-X Summer Fellowship (to A.Z. and L.Y.).

Author contributions

A.B., A.Z., H.B., M.B., L.Y., N.G., K.D.M., M.M., and I.L.W. designed research; A.B., A.Z., H.B., M.B., L.Y., and N.G. performed research; A.B., A.Z., H.B., M.B., L.Y., and N.G. analyzed data; and A.B., A.Z., and I.L.W. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

Patent was filed on combination therapy of CXCR2 inhibition and CD47 blockade.

Footnotes

Reviewers: A.M., Istituto Clinico Humanitas; D.G., AstraZeneca (United States); and J.D.L., Cleveland Clinic.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

There are no data underlying this work.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Yang Y., Cancer immunotherapy: Harnessing the immune system to battle cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 3335–3337 (2015), 10.1172/JCI83871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma P., Hu-Lieskovan S., Wargo J. A., Ribas A., Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell 168, 707–723 (2017), 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldman A. D., Fritz J. M., Lenardo M. J., A guide to cancer immunotherapy: From T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 651–668 (2020), 10.1038/s41577-020-0306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demaria O., et al. , Harnessing innate immunity in cancer therapy. Nature 574, 45–56 (2019), 10.1038/s41586-019-1593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng M., et al. , Phagocytosis checkpoints as new targets for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 19, 568–586 (2019), 10.1038/s41568-019-0183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidov V., Jensen G., Mai S., Chen S. H., Pan P. Y., Analyzing one cell at a TIME: Analysis of myeloid cell contributions in the tumor immune microenvironment [published correction appears in Front Immunol. 2021 Feb 01;11:645213]. Front Immunol. 11, 1842 (2020), 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantovani A., Marchesi F., Jaillon S., Garlanda C., Allavena P., Tumor-associated myeloid cells: Diversity and therapeutic targeting. Cell Mol. Immunol. 18, 566–578 (2021), 10.1038/s41423-020-00613-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan Y., Yu Y., Wang X., Zhang T., Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immunity [published correction appears in Front Immunol. 2021 Dec 10;12:775758]. Front Immunol. 11, 583084 (2020), 10.3389/fimmu.2020.583084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabrilovich D. I., Nagaraj S., Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 162–174 (2009), 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar V., Patel S., Tcyganov E., Gabrilovich D. I., The nature of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 37, 208–220 (2016), 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q. W., et al. , Prognostic significance of tumor-associated macrophages in solid tumor: A meta-analysis of the literature. PLoS ONE 7, e50946 (2012), 10.1371/journal.pone.0050946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montero A. J., Diaz-Montero C. M., Kyriakopoulos C. E., Bronte V., Mandruzzato S., Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients: A clinical perspective. J. Immunother. 35, 107–115 (2012), 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318242169f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanley E. R., Chitu V., CSF-1 receptor signaling in myeloid cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 6, a021857 (2014), 10.1101/cshperspect.a021857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanley E. R., Chen D. M., Lin H. S., Induction of macrophage production and proliferation by a purified colony stimulating factor. Nature 274, 168–170 (1978), 10.1038/274168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagasse E., Weissman I. L., Enforced expression of Bcl-2 in monocytes rescues macrophages and partially reverses osteopetrosis in op/op mice. Cell. 89, 1021–1031 (1997), 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchem J. B., et al. , Targeting tumor-infiltrating macrophages decreases tumor-initiating cells, relieves immunosuppression, and improves chemotherapeutic responses. Cancer Res. 73, 1128–1141 (2013), 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mok S., et al. , Inhibition of colony stimulating factor-1 receptor improves antitumor efficacy of BRAF inhibition. BMC Cancer 15, 356 (2015), 10.1186/s12885-015-1377-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sluijter M., et al. , Inhibition of CSF-1R supports T-cell mediated melanoma therapy. PLoS ONE 9, e104230 (2014), 10.1371/journal.pone.0104230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conway J. G., et al. , Inhibition of colony-stimulating-factor-1 signaling in vivo with the orally bioavailable cFMS kinase inhibitor GW2580. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16078–16083 (2005), 10.1073/pnas.0502000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strachan D. C., et al. , CSF1R inhibition delays cervical and mammary tumor growth in murine models by attenuating the turnover of tumor-associated macrophages and enhancing infiltration by CD8+ T cells. Oncoimmunology 2, e26968 (2013), 10.4161/onci.26968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lokeshwar B. L., Lin H. S., Development and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to murine macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Immunol. 141, 483–488 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDonald K. P., et al. , An antibody against the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor depletes the resident subset of monocytes and tissue- and tumor-associated macrophages but does not inhibit inflammation. Blood 116, 3955–3963 (2010), 10.1182/blood-2010-02-266296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien S. A., et al. , Activity of tumor-associated macrophage depletion by CSF1R blockade is highly dependent on the tumor model and timing of treatment. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 70, 2401–2410 (2021), 10.1007/s00262-021-02861-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Y., et al. , CSF1/CSF1R blockade reprograms tumor-infiltrating macrophages and improves response to T-cell checkpoint immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer models. Cancer Res. 74, 5057–5069 (2014), 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majeti R., et al. , CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell 138, 286–299 (2009), 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chao M. P., et al. , Anti-CD47 antibody synergizes with rituximab to promote phagocytosis and eradicate non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cell 142, 699–713 (2010), 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willingham S. B., et al. , The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 6662–6667 (2012), 10.1073/pnas.1121623109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J., et al. , Pre-clinical development of a humanized anti-CD47 antibody with anti-cancer therapeutic potential. PLoS ONE 10, e0137345 (2015), 10.1371/journal.pone.0137345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon S. R., et al. , PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature 545, 495–499 (2017), 10.1038/nature22396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barkal A. A., et al. , Engagement of MHC class I by the inhibitory receptor LILRB1 suppresses macrophages and is a target of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 19, 76–84 (2018), 10.1038/s41590-017-0004-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barkal A. A., et al. , CD24 signalling through macrophage Siglec-10 is a target for cancer immunotherapy. Nature 572, 392–396 (2019), 10.1038/s41586-019-1456-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ries C. H., et al. , Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell 25, 846–859 (2014), 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tap W. D., et al. , Structure-guided blockade of CSF1R kinase in tenosynovial giant-cell tumor. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 428–437 (2015), 10.1056/NEJMoa1411366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai X. M., et al. , Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood 99, 111–120 (2002), 10.1182/blood.v99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosn E. E., et al. , Two physically, functionally, and developmentally distinct peritoneal macrophage subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2568–2573 (2010), 10.1073/pnas.0915000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leijh P. C., van Zwet T. L., ter Kuile M. N., van Furth R., Effect of thioglycolate on phagocytic and microbicidal activities of peritoneal macrophages. Infect. Immun. 46, 448–452 (1984), 10.1128/iai.46.2.448-452.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y. M., Baviello G., Vlassara H., Mitsuhashi T., Glycation products in aged thioglycollate medium enhance the elicitation of peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. Methods 201, 183–188 (1997), 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obermajer N., Muthuswamy R., Odunsi K., Edwards R. P., Kalinski P., PGE(2)-induced CXCL12 production and CXCR4 expression controls the accumulation of human MDSCs in ovarian cancer environment. Cancer Res. 71, 7463–7470 (2011), 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katoh H., et al. , CXCR2-expressing myeloid-derived suppressor cells are essential to promote colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 24, 631–644 (2013), 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y., et al. , Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote the stemness of colorectal cancer cells through exosomal S100A9. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 6, 1901278 (2019), 10.1002/advs.201901278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X., et al. , Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote epithelial ovarian cancer cell stemness by inducing the CSF2/p-STAT3 signalling pathway. FEBS J. 287, 5218–5235 (2020), 10.1111/febs.15311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bosiljcic M., et al. , Targeting myeloid-derived suppressor cells in combination with primary mammary tumor resection reduces metastatic growth in the lungs. Breast Cancer Res. 21, 103 (2019), 10.1186/s13058-019-1189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vinogradov S., Warren G., Wei X., Macrophages associated with tumors as potential targets and therapeutic intermediates. Nanomedicine (London) 9, 695–707 (2014), 10.2217/nnm.14.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solinas G., Germano G., Mantovani A., Allavena P., Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. J. Leukoc Biol. 86, 1065–1073 (2009), 10.1189/jlb.0609385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu S., et al. , Tumor-associated macrophages: Role in tumorigenesis and immunotherapy implications. J. Cancer 12, 54–64 (2021), 10.7150/jca.49692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabrilovich D. I., Velders M. P., Sotomayor E. M., Kast W. M., Mechanism of immune dysfunction in cancer mediated by immature Gr-1+ myeloid cells J. Immunol. 166, 5398–5406 (2001), 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Mitri D., et al. , Re-education of tumor-associated macrophages by CXCR2 blockade drives senescence and tumor inhibition in advanced prostate cancer. Cell Rep. 28, 2156–2168 (2019), 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang G., et al. , Targeting YAP-dependent MDSC infiltration impairs tumor progression. Cancer Discov. 6, 80–95 (2016), 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang J., et al. , Targeted deletion of CXCR2 in myeloid cells alters the tumor immune environment to improve antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol. Res. 9, 200–213 (2021), 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Groth C., et al. , Blocking migration of polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells inhibits mouse melanoma progression. Cancers 13, 726 (2021), 10.3390/cancers13040726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun L., et al. , Inhibiting myeloid-derived suppressor cell trafficking enhances T cell immunotherapy. JCI Insight 4, e126853 (2019), 10.1172/jci.insight.126853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steele C. W., et al. , CXCR2 inhibition profoundly suppresses metastases and augments immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 29, 832–845 (2016), 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar V., et al. , Cancer-associated fibroblasts neutralize the anti-tumor effect of CSF1 receptor blockade by inducing PMN-MDSC infiltration of tumors. Cancer Cell. 32, 654–668.e5 (2017), 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bronte V., et al. , Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat. Commun. 7, 12150 (2016), 10.1038/ncomms12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cassetta L., et al. , Deciphering myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Isolation and markers in humans, mice and non-human primates. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 68, 687–697 (2019), 10.1007/s00262-019-02302-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

There are no data underlying this work.