HIGHLIGHTS

-

•

This study measured the implementation of COVID-19 medication for opioid use disorder accommodations across 3 time periods.

-

•

Multiday dosing was the only accommodation substantially retracted after COVID-19 shutdown.

-

•

Nearly half (43%) of all providers were unaware of the allowed COVID-19 regulatory flexibilities.

-

•

Federal regulatory changes did not produce a sustained impact on patient medication for opioid use disorder accommodations.

Keywords: methadone, buprenorphine, multiday methadone dosing, federal regulatory policy, policy implementation, Telehealth

Abstract

Introduction

This study examined the impact of federal regulatory changes on methadone and buprenorphine treatment during COVID-19 in Arizona.

Methods

A cohort study of methadone and buprenorphine providers from September 14, 2021 to April 15, 2022 measured the proportion of 6 treatment accommodations implemented at 3 time periods: before COVID-19, during Arizona's COVID-19 shutdown, and at the time of the survey completion. Accommodations included (1) telehealth, (2) telehealth buprenorphine induction, (3) increased multiday dosing, (4) license reciprocity, (5) home medications delivery, and (6) off-site dispensing. A multilevel model assessed the association of treatment setting, rurality, and treatment with accommodation implementation time.

Results

Over half (62.2%) of the 74-provider sample practiced in healthcare settings not primarily focused on addiction treatment, 19% practiced in methadone clinics, and 19% practiced in treatment clinics not offering methadone. Almost half (43%) were unaware of the regulatory changes allowing treatment accommodation. Telehealth was most frequently reported, increasing from 30% before COVID-19 to 80% at the time of the survey. Multiday dosing was the only accommodation substantially retracted after COVID-19 shutdown: from 41% to 23% at the time of the survey. Providers with higher patient limits were 2.5–3.2 times as likely to implement telehealth services, 4.4 times as likely to implement buprenorphine induction through telehealth, and 15.2–20.9 times as likely to implement license reciprocity as providers with lower patient limits. Providers of methadone implemented 12% more accommodations and maintained a higher average proportion of implemented accommodations during the COVID-19 shutdown period but were more likely to reduce the proportion of implemented accommodations (a 17-percentage point gap by the time of the survey).

Conclusions

Federal regulatory changes are not sufficient to produce a substantive or sustained impact on provider accommodations, especially in methadone medical treatment settings. Practice change interventions specific to treatment settings should be implemented and studied for their impact.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Despite the effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine in reducing opioid overdoses and all-cause mortality,1 these treatments remain highly stigmatized for patients and providers2 and are unevenly distributed by location3, 4, 5 and community racial composition.6, 7, 8 Furthermore, differences in U.S. methadone and buprenorphine regulatory regimes create distinct and unique barriers to access.9, 10, 11, 12 For example, methadone is delivered only by certified opioid treatment programs (OTPs) that are limited in number by state regulation with more stringent federal regulatory oversight than buprenorphine, which can be offered in clinician offices and dispensed by community pharmacies.13 For methadone, the biggest access challenge is the requirement for daily in-person, supervised medication dosing. Patients rarely receive multiday doses (also called take-home doses or, pejoratively, privileges) because they depend on patient time in the program and eligibility on the basis of criteria often varying by clinic.13 Between 56% and 82% of patients ever receive multiday doses, and over half never receive more than a 1- or 2-day supply.14,15 In-person dosing and limited multiday dosing can make methadone feel like liquid handcuffs,16 figuratively binding patients to the clinic.17

In contrast, buprenorphine is pharmacy dispensed in multiday and multiweek prescriptions. However, as we found in Arizona, the allowed number of prescribed buprenorphine doses depended upon the provider.18 Buprenorphine access also depends upon finding a provider who is an authorized prescriber and actively accepting new patients and patient insurance. As with methadone, these barriers complicate and limit access to this medication.

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, treatment access barriers intensified, and reported opioid overdoses increased by 30% nationally during that first year.19 As the demand for treatment increased, so did access barriers and the risk of treatment failure for those on buprenorphine or methadone—also called medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD).20 The pandemic made it riskier to congregate socially, which led to stay-at-home orders issued in Arizona and other states.21 To address these challenges of MOUD access and the need for reduced COVID-19 exposure in clinics, federal agencies regulating MOUDs temporarily relaxed several treatment and dispensing requirements in March 2020.22, 23, 24

Federal MOUD accommodations included (1) telehealth (audio only, audio video, or for use by behavioral health support groups); (2) buprenorphine induction through telehealth; (3) increased multiday dosing beyond the Code of Federal Regulation requirements, which was not just about methadone because, as stated earlier, buprenorphine dosing could also be increased; (4) license reciprocity to allow for out-of-state dispensing; (5) home delivery of medications (at-home provision of methadone or buprenorphine, use of a lock box for methadone dispensing at home); and (6) off-site dispensing (nonpharmacy). Accommodations implementation was optional for state regulators and providers; therefore, understanding their impact on access to MOUDs is a national priority, especially because we anticipate additional regulatory flexibility, including the permanence of the COVID-19 period flexible allowances and increased patient-centered MOUD treatment practices.25 Findings will inform communities, researchers, regulators, and other policymakers about whether these changes improved access to services without introducing deleterious health outcomes for people on methadone or buprenorphine.

Current studies of provider acceptance or implementation of COVID-19 MOUD accommodations report varying results. A study among 59 Texas and New Mexico methadone providers found a range of beliefs about multiday dosing owing to concerns about patient safety and provider liability.26 Similar findings emerged from a case study in 1 Washington state methadone clinic.14 A New Jersey study among 20 methadone and buprenorphine providers reported a shift toward telehealth, a reduction in toxicology screening and counseling services, and modifications to multiday dosing.27 Finally, a review of 1 San Francisco methadone clinic reported full implementation (undefined) of federal regulations.28 Taken together, these small studies indicate what some providers might have done or thought about relative to accommodations allowed at the time data were gathered, and it appeared that some accommodations were being offered. However, there are contrasting findings from a review of studies reporting methadone dosing in publications across several states. This study found that although a vast majority (89%) increased multiday doses in April 2020, only 26.8% and 16.8% of patients received the allowed 14 days and 28 days of dosing for unstable and stable patients, respectively.29 This, to the best of our knowledge, was the only study of any scope, and yet was based on a review of published studies from several states and not on a statewide study. Furthermore, these studies did not examine elements that are known to impact implementation such as provider characteristics or practice setting characteristics.30

Although these studies indicate some provider beliefs and/or behaviors during COVID-19, they do not provide a view of what providers were doing before, during, and after COVID-19 relative to the allowed accommodations and do not indicate comparative outcomes by provider setting. Because states have regulatory control of MOUD implementation generally and with these federal regulatory accommodations specifically, placed-based (context-specific) studies are necessary. Finally, as we enter a second phase of unprecedented regulatory flexibility with MOUDs,25 it is important to explore differences in accommodations implemented, by whom, in what setting, and for how long—important factors associated with practice change innovation.31,32 Our study reports these data through a statewide survey of methadone and buprenorphine providers, assessing the implementation of federally allowed accommodations in the state of Arizona.

METHODS

Provider implementation of federally allowed MOUD accommodations was measured using a 52-item survey fielded to a sample of Arizona methadone and buprenorphine providers requiring <30 minutes to complete. This study focused on the provider- versus clinic-level implementation because providers are the prescribers and ultimately determine the implementation of treatment accommodations.

Study Sample

As noted elsewhere, the original plan was to draw a sample from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), a source that was thought at the time to be the best list of MOUD providers by state.33 From the DEA, we obtained a listing of Arizona providers authorized to prescribe buprenorphine. It was obtained in March 2021 and was combined with a list of OTPs (methadone clinics) from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) public opioid treatment directory.34 We then removed tribal providers to respect sovereignty because no extant intergovernmental agreements existed regarding this study.

We first drew a stratified random sample of 1,000 providers, which included all providers located with methadone clinic addresses and rural providers, with a balance of randomly selected urban buprenorphine providers. Three recruitment waves were implemented. As reported elsewhere,33 owing to lack of robust response, sampling was expanded to involve social recruitment through Arizona MOUD professional associations, followed by a census sampling of the full DEA list (less those who already had responded). The survey was administered from September 14, 2021 to April 15, 2022. Survey distribution was based on a modified Dillman method35 (paper invitation to an online survey) used successfully in prior studies among pharmacists and nurses.36, 37, 38 Study information was provided on the survey online landing page, which also included a consent process. A $20 online Visa gift card was provided upon survey completion. Study oversight was provided by the University of Arizona IRB.

Measures

Measures included the following federally allowed MOUD treatment accommodations during COVID-29: (1) telehealth (audio only, audio video, or for use by behavioral health support groups), (2) buprenorphine induction through telehealth, (3) increased multiday dosing beyond what was allowed by the pre–COVID-19 regulations, (4) license reciprocity to allow for out-of-state dispensing, (5) home delivery of medications (at-home provision of methadone or buprenorphine, use of a lock box for methadone dispensing at home, and so on), and (6) off-site dispensing (nonpharmacy). Whether or not each accommodation was implemented was measured at 3 time periods: (1) before COVID-19, (2) during Arizona's COVID-19 shutdown (March 15–May 15, 2020), and (3) at the time of the survey currently. The time between Arizona's COVID-19 shutdown and survey completion was 16–23 months. We also measured provider knowledge of the regulatory changes and what their treatment practices did during the COVID-19 shutdown in Arizona (remain open while changing a few business practices to reduce COVID-19 risks for all patients, remain open for business as usual without any major changes, or closed the practice). Provider awareness of regulatory flexibilities was measured with the question Did the federal government or state government relax any policies or regulations affecting how you delivered MAT to your patients during the COVID pandemic? The response format was Yes, No, and I don't know.

Provider characteristics included practice settings, which were coded as follows: stand-alone methadone clinic, substance use disorder (SUD) clinic (excluding stand-alone methadone clinics), and healthcare setting that was not primarily an opioid use disorder (OUD) clinic (e.g., general health clinic). Coding practice settings such as stand-alone methadone clinics, SUD clinics (excluding stand-alone methadone clinics), and healthcare settings were based on the hypothesis that there might be implementation differences among methadone clinics compared with that among other settings.39,40 Note that providers could offer methadone and be considered an OTP by the federal government even if their practice setting was a healthcare facility such as a healthcare unit in a detention center or a federally qualified health clinic. These providers, although offering methadone as a treatment, were not coded as stand-alone methadone clinics.

Provider characteristics also included the type of medication prescribed (methadone versus nonmethadone treatments) and the rurality of the practice setting, which was dichotomized (urban, rural).41 Providers were also associated with their DEA-approved patient prescribing limit (30, 100, 275) indicated by their DEA listing.42

Statistical Analysis

Frequencies were described for each accommodation by practice setting and medication (methadone or nonmethadone treatments) to assess accommodations implementation. The percentage of surveyed providers who implemented each accommodation was visually depicted, stratified by setting. The association of provider characteristics with accommodations implementation differences during COVID-19 was explored through a series of logistic regressions assessing the odds of implementation of each accommodation among providers that did not previously offer them before COVID-19. We then calculated the odds of implementing telehealth, buprenorphine induction through telehealth, increased multiday dosing, license reciprocity, and home delivery of medications across provider characteristics (patient limits, practice setting, medication offered, and rural versus urban location). Off-site dispensing was only implemented by 3 providers and was not examined owing to insufficient variation in the outcome variable.

We then created a metric capturing the overall implementation of accommodations: the proportion of relevant accommodations implemented by provider. We adjust for relevance because some of the accommodations were medication specific and thus only applicable to certain providers. For providers offering methadone, the number of implemented accommodations was based on the sum of all 6 listed earlier. This count was then scaled to a proportion of the 6 relevant accommodations. For providers who did not offer methadone, the count was based on whether they implemented telehealth, buprenorphine induction through telehealth, or license reciprocity to allow for out-of-state dispensing. For these nonmethadone providers, the proportion of implemented accommodations is the percentage of these 3 implemented accommodations.

The outcome variable was the proportion of relevant accommodations implemented by providers over 3 time periods. We selected this outcome to assist with model development and because it would give a clearer picture of the extent to which relevant and allowed accommodations were implemented. A simple mixed model was constructed to examine the associations between various provider characteristics and the proportion of relevant accommodations implemented over 3 time periods to parse complexities of setting and regulatory regime differences. Linear growth modeling, also known as multilevel modeling for change,43 was used to identify provider characteristics (methadone treatment provider, rurality, provider setting) associated with trends in relevant accommodations implementation over time. All models were run in STATA 16.1 and were based on a set of 222 observations (3 waves for 74 completed survey responses).

The constructed models included Model #1 (FIT Model) assessing the appropriateness of the modeling approach for the outcome variable. Model #2 (methadone treatment) included the independent variables of patient prescribing limit, rurality, and whether a provider offered methadone as treatment. Model #3 (practice setting) included the independent variables of prescribing limit and rurality as well as the practice setting (measured by practicing in a stand-alone methadone clinic, a SUD clinic [not a stand-alone methadone clinic], or other healthcare facility). All stand-alone methadone clinics offer methadone as a treatment. As such, the variable identifying providers who offer methadone was found to be highly correlated with the dichotomous variable identifying stand-alone methadone clinics (r=0.69). This high degree of multicollinearity is the reason for exploring these 2 models (Models 2 and 3) separately. Unless otherwise noted, all findings were significant at the p≤0.05 level.

RESULTS

Despite the extended survey period using a variety of recruitment methods, a final sample included 74 providers from 11 of Arizona's 15 counties.44 As shown in Table 1, over half (62.2%) of providers were located in healthcare settings not primarily focused on OUD treatment. Less than 20% of all providers practiced in stand-alone methadone clinics, whereas another 19% were in SUD-focused settings that were not methadone clinics. Over half of all providers (65%) prescribed buprenorphine, and the vast majority of those prescribing methadone also reported prescribing buprenorphine (96.2%).

Table 1.

Methadone and Buprenorphine Provider Characteristics, Arizona 2022 (N=74)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Settings | |

| OUD treatment settings | |

| Stand-alone methadone clinic | 15 (20.3%) |

| SUD clinic (excluding stand-alone methadone clinics) | 14 (18.9%) |

| Other healthcare settings (non-OUD specific) | |

| Private medical office | 16 (21.6%) |

| Other (VA clinics, CHCs, correctional clinics, hospitals) | 29 (39.2%) |

| Medication type | |

| Methadone | 1 (1.4%) |

| Buprenorphine (alone or in combination with other nonmethadone treatment) | 48 (64.9%) |

| Methadone and buprenorphine | 25 (33.8%) |

| Provider type (completing the survey) | |

| Physician | 27 (36.5%) |

| Physician assistant | 4 (5.4%) |

| Nurse practitioner | 43 (58.1%) |

| DEA waiver patient prescribing limits | |

| 30 patients | 37 (50.0%) |

| 100 patients | 24 (32.4%) |

| 275 patients | 13 (17.6%) |

| Rurality | |

| Urban | 59 (80.0%) |

| Large and small rural city/town | 15 (20.0%) |

CHC, community health center; DEA, Drug Enforcement Administration; OUD, opioid use disorder; SUD, substance use disorder; VA, Veterans Affairs.

During Arizona's stay-at-home order, 78% of providers indicated that their clinic remained open while changing a few business practices to reduce patient COVID-19 risk, and 19% indicated that their clinic remained open without any major changes. Providers in other (non–OUD-focused) healthcare facilities were the most likely to report remaining open with no major changes (24% of 46 locations). Providers in stand-alone methadone clinics were the least likely to report remaining open during COVID-19 without making any major changes (7% or 1 of 14 clinics).

COVID-19 Accommodations

Nearly half (43%) of all providers were unaware of the allowed regulatory flexibilities during COVID-19. The vast majority of stand-alone methadone clinic providers reported being aware of them (86%), followed by providers in nonmethadone SUD treatment settings (64%) and those in other healthcare settings (46%). Among urban providers, a majority (64%) were aware of these regulatory changes compared with only 27% of rural providers.

Telehealth was the most frequently reported accommodation across providers and measured time periods. Before the onset of the pandemic, just over 30% of providers reported use of telehealth. At the time of survey completion, nearly 80% of providers reported the use of telehealth in the context of MOUD treatment. The next most common accommodation, buprenorphine induction through telehealth, increased from 15% of providers offering it before COVID-19 to 45% at the time of the survey.

Across the sample, multiday dosing increased from 3% before COVID-19 to 41% during the COVID-19 shutdown and fell to 23% at the time of the survey. This was the only accommodation to be substantially retracted after the COVID-19 shutdown period. The use of home delivery increased modestly from 28% before COVID-19 to 38% at the time of the survey. Off-site dispensing, license reciprocity, and additional services were not commonly implemented at any of the time points.

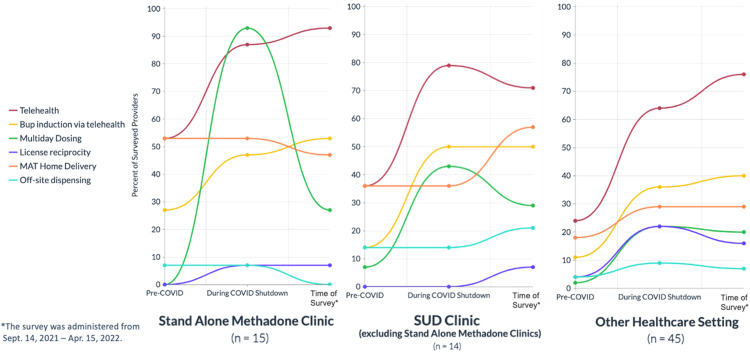

Practice setting was associated with implementation of federally allowed accommodations. Figure 1 depicts implementation patterns across the 3 practice settings of stand-alone methadone clinics, SUD clinics (excluding stand-alone methadone clinics), and other healthcare settings. Although a larger proportion of stand-alone methadone clinic providers implemented more accommodations, they also reported a larger average retraction of accommodations by the time of the survey. This included multiday dosing, home delivery, and off-site dispensing. By contrast, the average rates of implementation by providers in other healthcare facilities between the pre–COVID-19 and the shutdown periods were maintained or increased for almost every accommodation at the time of survey.

Figure 1.

Federally allowed methadone and buprenorphine accommodations implemented by Arizona providers before and during COVID-19 shutdown and at the time of survey by practice setting, Arizona 2022 (N=74).

Apr., April; Sept., September; SUD, substance use disorder.

Logistic Regression Results

The models in Table 2 present an examination of the odds of implementing each of the 5 types of accommodations among providers who did not already offer each service before COVID-19 across provider characteristics. Owing to the high collinearity between the medication type and practice setting variables, we examine each in separate models while controlling for patient limits and location (urban or rural). The most consistently influential factor in these analyses is the provider patient limit. Providers with higher patient limits (100 or 275 patients) were more likely to implement telehealth services, buprenorphine induction through telehealth, and license reciprocity than providers with lower patient limits (30 patients). Specifically, providers with higher patient limits were 3.5–4.2 times as likely to implement telehealth services (depending on which model specification is used), 5.4 times as likely to implement buprenorphine induction through telehealth, and 16.2–21.9 times as likely to implement license reciprocity as providers with lower patient limits. The only other statistically significant associations identified were that providers offering methadone were 11 times as likely to implement multiday dosing as providers not offering methadone as treatment, and providers operating in stand-alone methadone clinics were 32.7 times as likely to implement multiday dosing as providers operating within other healthcare facilities.

Table 2.

Odds of Implementing Different Types of MOUD Accommodations Over COVID-19 Time Periods, Among MOUD Providers Who Had Not Already Implemented Accommodation Before COVID-19, Arizona 2021

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation type | Telehealth | Buprenorphine induction through telehealth | Multiday dosing | License reciprocity | Home delivery | |||||

| Covariates | ||||||||||

| Higher patient limit (100 or 275) (ref category: patient limit=30) | 3.5a (2.3) | 4.2* (3.0) | 5.4** (3.1) | 5.4** (3.1) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.3) | 16.2* (17.7) | 21.9** (24.4) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.1) |

| Rural provider (ref category: urban provider) | 0.25a (0.20) | 0.24a (0.20) | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.2 (0.85) | 0.77 (0.63) | 0.63 (0.49) | 0.35 (0.41) | 0.26 (0.31) | 1.9 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.6) |

| Provider offering methadone (ref category: provider does not offer methadone) | 0.95 (0.68) | — | 1.6 (0.96) | — | 11*** (7.2) | — | 0.49 (0.36) | — | 0.46 (0.40) | — |

| Stand-alone methadone clinic (ref category: other healthcare facility) | — | 0.61 (0.63) | — | 0.94 (0.73) | — | 32.7** (36.2) | 0.20a (0.19) | — | 0.67 (0.80) | |

| SUD clinic (excluding stand-alone OTPs) (ref category: other healthcare facility) | — | 0.53 (0.47) | — | 1.2 (0.89) | — | 3.4a (2.3) | 0.17 (0.20) | — | 1.7 (1.5) | |

| Constant | 1.13 (0.55) | 1.23 (0.59) | 0.25** (0.13) | 0.29* (0.14) | 0.22** (0.11) | 0.26** (.13) | 0.04** (0.04) | 0.05** (0.05) | 0.22* (0.13) | 0.18** (0.11) |

| Number of observations (number of providers who had not already implemented examined accommodation) | 50 | 50 | 63 | 63 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 53 | 53 |

Note: Boldfaces indicate statistical significance (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

Two models are presented for each outcome owing to the high collinearity between the medication-type variable and the practice-setting variables. The coefficients presented are in the form of ORs with corresponding SEs below in parentheses.

p<0.10.

MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder; OTP, opioid treatment program; SUD, substance use disorder.

Multilevel Model Results

Models shown in Table 3 report the association of provider characteristics with accommodation implementation. The FIT model (Model #1) outcomes suggest that the modeling approach is appropriate for this outcome, meaning that the average trajectory of change in the proportion of relevant accommodations implemented is best characterized by a curvilinear function. Model #2 (methadone treatment) indicates that methadone providers were more likely to reduce the proportion of relevant accommodations implemented, meaning that they did not sustain them. This difference is substantive, with a 17-percentage point gap (on average) between methadone and nonmethadone providers by the time of the survey. Providers with higher patient limits were more likely to implement a larger proportion of relevant accommodations over time. This difference was also substantive and statistically significant.

Table 3.

Proportion of Relevant MOUD Accommodations Implemented Over COVID-19 Time Periods by MOUD Provider Characteristics, Arizona 2021 (N=74)

| Characteristic | FIT (Model 1) | Methadone treatment (Model 2) | Practice setting (Model 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | 0.33*** (0.05) | 0.33*** (0.05) | 0.32*** (0.05) |

| Time period squared | −0.11*** (0.02) | −0.11*** (0.02) | −0.11*** (0.02) |

| Covariate intercept effects | |||

| Higher patient limit (100 or 275) (ref category: patient limit=30) | — | 0.064 (0.06) | 0.054 (0.06) |

| Rural provider (ref category: urban provider) | — | 0.003 (0.07) | 0.007 (0.07) |

| Provider offering methadone (ref category: provider does not offer methadone) | — | 0.044 (0.06) | — |

| Stand-alone methadone clinic (ref category: other healthcare facility) | — | — | 0.10 (0.07) |

| SUD clinic (excluding stand-alone methadone clinics) (ref category: other healthcare facility) | — | — | 0.05 (0.07) |

| Covariate effect on slopea | |||

| Higher patient limit (100 or 275) | — | 0.11** (0.03) | 0.11** (0.03) |

| Rural provider | — | −0.053 (0.04) | −0.49 (0.04) |

| Provider offering methadone | — | −0.10** (0.04) | — |

| Stand-alone methadone clinic | — | — | −0.14** (0.04) |

| SUD clinic (less methadone clinics) | — | — | −0.032 (0.04) |

| Constant | 0.17*** (0.03) | 0.12* (0.05) | 0.11* (0.05) |

| Random effects | |||

| Intercept | 0.038* | 0.034* | 0.030* |

| Time | 0.010* | 0.06* | 0.005* |

| Residual | 0.026* | 0.026* | 0.026* |

| Covariance | −0.008 | −0.005 | −0.003 |

| Number of observations | 222 | 222 | 222 |

| Deviance (−2 log likelihood) | −9.13 | −30.6 | −33.5 |

| BIC | 28.7 | 39.6 | 47.6 |

Note: Boldfaces indicate statistical significance (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

These variables interacted with the linear time variable.

MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder; SUD, substance use disorder.

Model #2 (practice setting) indicates that stand-alone methadone clinic providers reported a moderately higher, statistically significant level of accommodation implementation during the pre–COVID-19 time period than providers in other treatment settings. This difference was 12 percentage points higher, on average, than reported by providers in other settings. From these different baseline values, the slope of change over time was statistically significant and negative for providers in stand-alone methadone clinics relative to the positive slope of other healthcare providers. This means that providers in stand-alone methadone clinics implemented more relevant accommodations than those in other settings before COVID-19, maintained a higher average proportion of implemented accommodations during the COVID-19 shutdown period, but then reduced accommodations more substantially than providers in non–stand-alone methadone SUD clinics and other healthcare facilities. In terms of sustained changes, at the time of the survey, providers who were not operating in stand-alone methadone clinic settings reported accommodation implementation levels of 11 percentage points higher than the average proportion implemented by providers in methadone clinics. Differences in the trajectories of accommodations implementation between rural and urban providers were not found to be statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the impact of federal regulatory policy change on methadone and buprenorphine medical practices and therefore patient access is a challenging task, requiring careful analysis specific to setting and regulated treatment while controlling for particular confounds. This study attempted to model a method of assessing the impact of federal regulatory flexibilities on methadone and buprenorphine during COVID-19 and at the time of the survey, up to 2 years after the Arizona COVID-19 shutdown.

Although extant studies suggest that regulatory changes are associated with accommodation implementation, this study suggests that this is not the case in Arizona—at least among this sample of providers and especially when considering practice settings. Our findings support 2 additional and more nuanced perspectives on how policy flexibilities affected (or did not) MOUD medical practice during a pandemic. By controlling for confounds and comparing relevant treatment accommodations over time with more precision, we found that the regulatory changes are simply not enough to produce a substantive or sustained impact on provider accommodations implementation. Setting-specific practice change interventions (stand-alone methadone clinic, nonmethadone SUD clinic, other healthcare settings) will need to be implemented and studied for impact on MOUD treatment practice changes. Implementation frameworks would suggest that both outer setting factors, such as regulatory policy, and inner setting factors, such as those studied here, are likely interactive and together influence implementation of new treatment practices and patient accommodations.30 Understanding implementation challenges is especially important as the federal government plans additional patient-centered regulatory changes to MOUDs.24

A useful point of comparison is our Arizona patient interview study, the largest existing survey of patient experiences with methadone and buprenorphine during COVID-19 (n=131).18 Just as the interview study demonstrated that accommodations were generally not experienced by patients beyond telehealth, this reported study of provider medical practices suggests that many treatment accommodations were not implemented or, if implemented, were not sustained, with the exception of telehealth. The limited MOUD treatment accommodations in Arizona are counter to both federal policy intention and patient preference, especially for multiday dosing.

Conversely, telehealth was broadly implemented and maintained. Although the causal relationship with federal regulatory flexibility is not entirely clear, for Arizona providers, the change is likely due to Arizona's legislative action to assure payment parity for telehealth across healthcare settings.45 Fiscal policy such as this is likely yet another important outer setting factor that should be understood for the extent to which it might influence accommodations, especially with multiday dosing of methadone.46

Limitations

This study is limited by our small survey sample size and the inability to calculate a response rate given the multiple recruitment efforts to achieve a survey sample. The experience with multiple recruitment efforts was sufficiently puzzling that we initiated an examination of the sample drawn from the DEA and SAMHSA lists using a telephone survey to confirm its accuracy and utility as a source for study sampling now and in the future. We found that only 307 providers in the originally drawn sample from the DEA/SAMHSA listing were located and confirmed as MOUD providers.47 This implies that our response rate was about 24.3%. Furthermore, even our provider colleagues in the Arizona MOUD Extension for Community Health Outcomes and other associations could not estimate the population of MOUD providers. Finally, when posing the challenge of sufficient sampling for practice-based MOUD survey research to other survey researchers, we learned that ours is not the only state where MOUD provider survey research is highly challenging.33

In addition, there is a likelihood that our sample is influenced by a self-selection bias where providers sampled through social recruitment methods might be more likely to respond to a survey about methadone and buprenorphine accommodations if they had a particular perspective or implementation experience.48 Although we cannot estimate the magnitude of this bias in our analyses, our findings here likely overstate the degree to which providers in Arizona implemented accommodations. This consideration may explain, in part, the disjuncture between the accommodations offered as reported by providers and the much lower levels of accommodations actually experienced by Arizona MOUD patients in our patient interview study.18 That said, the trends and associations revealed within this sample are instructive and useful because they point the way toward future methods and research questions to explore in multistate policy implementation studies of methadone and buprenorphine medical practice, especially if we can achieve larger provider survey response samples.

CONCLUSIONS

The recent federal regulatory changes are not sufficient to produce a substantive or sustained impact on provider accommodations, especially with regard to methadone medical treatment and stand-alone methadone clinic settings. Studies of MOUD medical treatment practice change interventions developed for specific treatment setting types are highly recommended.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Beth E. Meyerson: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Keith G. Bentele: Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Benjamin R. Brady: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Nick Stavros: Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Danielle M. Russell: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Arlene N. Mahoney: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Irene Garnett: Writing – review & editing. Shomari Jackson: Writing – review & editing. Roberto C. Garcia: Writing – review & editing. Haley B. Coles: Writing – review & editing. Brenda Granillo: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Gregory A. Carter: Writing – review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the leadership and guidance of the Drug Policy Research and Advocacy Board, a transdisciplinary, statewide group of medication for opioid use disorder providers; people on medication for opioid use disorder; people with lived/living drug use experience; harm reduction organizations; payers; and university researchers. We thank the members of the Drug Policy Research and Advocacy Board for their guidance and commitment to this study, and we thank the providers who took the time to respond to this survey.

This study was supported by grants from the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts and the Vitalyst Health Foundation.

Declaration of interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amato L, Davoli M, Perucci CA, Ferri M, Faggiano F, Mattick RP. An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(4):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen Y, Sharfstein JM. Confronting the stigma of opioid use disorder—and its treatment. JAMA. 2014;311(14):1393–1394. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brady BR, Gildersleeve R, Koch BD, Campos-Outcalt DE, Derksen DJ. Federally qualified health centers can expand rural access to buprenorphine for opioid users in Arizona. Health Serv Insights. 2021;14 doi: 10.1177/11786329211037502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haffajee RL, Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Goldstick JE. Characteristics of U.S. counties with high opioid overdose mortality and low capacity to deliver medications for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knudsen HK, Havens JR, Lofwall MR, Studts JL, Walsh SL. buprenorphine physician supply: relationship with state-level prescription opioid mortality. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173(suppl 1):S55–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lagisetty PA, Ross R, Bohnert A, Clay M, Maust DT. buprenorphine treatment divide by race/ethnicity and payment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):979–981. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goedel WC, Shapiro A, Cerdá M, Tsai JW, Hadland SE, Marshall BDL. Association of racial/ethnic segregation with treatment capacity for opioid use disorder in counties in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen HB, Siegel CE, Case BG, Bertollo DN, DiRocco D, Galanter M. Variation in use of buprenorphine and methadone treatment by racial, ethnic, and income characteristics of residential social areas in New York City. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2013;40(3):367–377. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9341-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peavy KM, Darnton J, Grekin P, et al. Rapid implementation of service delivery changes to mitigate COVID-19 and maintain access to methadone among persons with and at high-risk for HIV in an opioid treatment program. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(9):2469–2472. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02887-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andraka-Christou B. Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in the use of medications for opioid use disorder. Health Aff (Millwood) 2021;40(6):920–927. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2015. Federal guidelines for opioid treatment programs.https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep15-fedguideotp-federal-guidelines-for-opioid-treatment-programs.pdf Published January. Accessed January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 12.GovInfo . GovInfo; Washington, DC: 2008. Public law no: 110-425 (10/15/2008) - Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008.https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-110publ425 Published October 15. Accessed January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2015. Federal guidelines for opioid treatment programs. HHS Publication No. PEP15-FEDGUIDEOTP.https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/pep15-fedguideotp.pdf Accessed May 23, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walley AY, Cheng DM, Pierce CE, et al. methadone dose, take home status, and hospital admission among methadone maintenance patients. J Addict Med. 2012;6(3):186–190. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182584772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figgatt MC, Salazar Z, Day E, Vincent L, Dasgupta N. Take-home dosing experiences among persons receiving methadone maintenance treatment during COVID-19. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;123 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith CB. A Users’ guide to ‘juice bars’ and ‘liquid handcuffs’: fluid negotiations of subjectivity, space and the substance of methadone treatment. Space Cult. 2011;14(3):2–19. doi: 10.1177/1206331211412238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank D, Mateu-Gelabert P, Perlman DC, et al. It's like ‘liquid handcuffs”: The effects of take-home dosing policies on methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) patients’ lives. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18:88. doi: 10.1186/s12954-021-00535-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyerson BE, Bentele KG, Russell DM, et al. Nothing really changed: arizona patient experience of methadone and buprenorphine access during COVID. PLoS One. 2022;17(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghose R, Forati AM, Mantsch JR. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on opioid overdose deaths: a spatiotemporal analysis. J Urban Health. 2022;99(2):316–327. doi: 10.1007/s11524-022-00610-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. Arizona Statewide Prevention Needs Assessment. https://www.azahcccs.gov/Resources/Downloads/Grants/ArizonaSubstanceAbusePreventionNeedsAssessment.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- 21.States’ COVID-19 public health emergency declarations and mask requirements. National Academy for State Health Policy. https://nashp.org/states-covid-19-public-health-emergency-declarations/. Updated June 13, 2023. Accessed June 30, 2023.

- 22.United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). FAQs: Provision of Methadone and Buprenorphine for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in the COVID-19 Emergency; 2020 [online]: https://tinyurl.com/sxbcnh3.

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2018. Use of telemedicine while providing medication assisted treatment (MAT)https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/medication_assisted/telemedicine-dea-guidance.pdf Published May 15. Accessed January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). COVID-19: CMS allowing audio-only calls for OTP therapy, counseling and periodic assessments; 2020 [online]: https://tinyurl.com/y89gobl7. Accessed May 19, 2020.

- 25.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2020. Notice of proposed rule making to 42 CFR Part 8. SAMHSA proposes update to federal rules to expand access to opioid use disorder treatment and help close gap in care.https://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/20221213/update-federal-rules-expand-access-opioid-use-disorder-treatment PublishedAccessed February 15, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madden EF, Christian BT, Lagisetty PA, Ray BR, Sulzer SH. Treatment provider perceptions of take-home methadone regulation before and during COVID-19. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;228 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treitler PC, Bowden CF, Lloyd J, Enich M, Nyaku AN, Crystal S. Perspectives of opioid use disorder treatment providers during COVID-19: adapting to flexibilities and sustaining reforms. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;132 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen OK, Steiger S, Snyder H et al. Outcomes associated with expanded take-home eligibility for outpatient treatment with medications for opioid use disorder: a mixed methods analysis. medRxiv. Posted online December 13, 2021. 10.1101/2021.12.10.21267477. [DOI]

- 29.Krawczyk N. The National Academies of Science Engineering Medicine; Washington, DC: 2022. Lessons learned from COVID-19 and regulatory change in the wake of necessity.https://www.nationalacademies.org/documents/embed/link/LF2255DA3DD1C41C0A42D3BEF0989ACAECE3053A6A9B/file/D3E063A30D9D988E5EB95D66B10AABA47900519FC319 Accessed June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ. A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(2):194–205. doi: 10.1037/a0022284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirchner JE, Smith JL, Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Proctor EK. Getting a clinical innovation into practice: an introduction to implementation strategies. Psychiatry Res. 2020;283 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly CJ, Young AJ. Promoting innovation in healthcare. Future Healthc J. 2017;4(2):121–125. doi: 10.7861/futurehosp.4-2-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brady B, Meyerson BE, Bentele KG. Flying blind: survey research among methadone and buprenorphine providers in Arizona. Surv Methods Insights Field. 2023;2:1–9. https://surveyinsights.org/?p=17985 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Opioid treatment program directory. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://dpt2.samhsa.gov/treatment/directory.aspx. Accessed August 9, 2022.

- 35.Dillman DA. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 1978. Mail and Telephone Surveys: The Total Design Method. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agley J, Meyerson BE, Eldridge LA, et al. Exploration of pharmacist comfort with harm reduction behaviors: cross-sectional latent class analysis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2022;62(2):432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2021.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter GA, Meyerson BE, Rivers P, et al. Living at the confluence of stigmas: PrEP awareness and feasibility among people who inject drugs in two predominantly rural states. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(10):3085–3096. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyerson BE, Agley JD, Jayawardene W, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a proposed pharmacy-based harm reduction intervention to reduce opioid overdose, HIV and hepatitis C. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16(5):699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon C, Vincent L, Coulter A, et al. The methadone manifesto: treatment experiences and policy recommendations from methadone patient activists. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(suppl 2):S117–S122. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaffe JH, O'Keeffe C. From morphine clinics to buprenorphine: regulating opioid agonist treatment of addiction in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(2):S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00055-3. (suppl) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morrill R, Cromartie J, Hart G. Metropolitan, urban, and rural commuting areas: toward a better depiction of the United States settlement system. Urban Geogr. 1999;20(8):727–748. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.20.8.727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorders. 21 U.S.C. 823; 42 U.S.C. 257a, 290bb-2a, 290aa(d), 290dd-2, 300x-23, 300x-27(a), 300y-11. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/07/08/2016-16120/medication-assisted-treatment-for-opioid-use-disorders. Published August 7, 2016. Accessed July 19, 2023.

- 43.Singer J, Willett J. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2003. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 44.These counties were Coconino, Cochise, Gila, Graham, Maricopa, Mohave, Navajo, Pima, Pinal, Yavapai, and Yuma.

- 45.Telehealth; Health Care Providers; Requirements, H.B. 2454, Arizona State Legislature (2021), https://legiscan.com/AZ/text/HB2454/id/2391998. Accessed June 2022.

- 46.Bowser D, Bohler R, Davis MT, Hodgkin D, Frank RG, Horgan CM. Health Affairs; Bethesda, MD: 2023. New methadone treatment regulations should be complemented by payment and financing reform.https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/new-methadone-treatment-regulations-should-complemented-payment-and-financing-reform Published June 1. Accessed June 15, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyerson BE, Treiber D, Bonderant K, et al. Dialing for doctors: Secret shopper study to identify MOUD providers in Arizona, 2022 (In review). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Heckman JJ. In: Econometrics. Eatwell J, Milgate M, Newman P, editors. Palgrave Macmillan London; London, United Kingdom: 1990. Selection bias and self-selection. [Google Scholar]