Summary

Background

The sequential anti-osteoporotic treatment for women with postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO) is important, but the order in which different types of drugs are used is confusing and controversial. Therefore, we performed a network meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of available sequential treatments to explore the most efficacious strategy for long-term management of osteoporosis.

Methods

In this network meta-analysis, we searched the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to September 19, 2023 to identify randomised controlled trials comparing sequential treatments for women with PMO. The identified trials were screened by reading the title and abstract, and only randomised clinical trials involving sequential anti-osteoporotic treatments and reported relevant outcomes for PMO were included. The main outcomes included vertebral fracture risk, the percentage change in bone mineral density (BMD) in different body parts, and all safety indicators in the stage after switching treatment. A frequentist network meta-analysis was performed using the multivariate random effects method and evaluated using the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA). Certainty of evidence was assessed using the Confidence in the Network Meta-Analysis (CINeMA) framework. This study is registered with PROSPERO: CRD42022360236.

Findings

A total of 19 trials comprising 18,416 participants were included in the study. Five different sequential treatments were investigated as the main interventions and compared to the corresponding control groups. The intervention groups in this study comprised the following treatment switch protocols: switching from an anabolic agent (AB) to an anti-resorptive agent (AR) (ABtAR), transitioning from one AR to another AR (ARtAAR), shifting from an AR to an AB (ARtAB), switching from an AB to a combined treatment of AB and AR (ABtC), and transitioning from an AR to a combined treatment (ARtC). A significant reduction in the incidence of vertebral fractures was observed in ARtC, ABtAR and ARtAB in the second stage, and ARtC had the lowest incidence with 81.5% SUCRA. ARtAAR and ABtAR were two effective strategies for preventing fractures and improving BMD in other body parts. Especially, ARtAAR could improve total hip BMD with the highest 96.1% SUCRA, and ABtAR could decrease the risk of total fractures with the highest 94.3% SUCRA. Almost no difference was observed in safety outcomes in other comparisons.

Interpretation

Our findings suggested that the ARtAAR and ABtAR strategy are the effective and safe sequential treatment for preventing fracture and improving BMD for PMO. ARtC is more effective in preventing vertebral fractures.

Funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170900, 81970762), the Hunan Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and the Hunan Province High-level Health Talents "225" Project.

Keywords: Sequential, Anti-osteoporotic treatments, Postmenopausal osteoporosis, Fractures, Bone mineral density

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Many guidelines recommend sequential treatments for patients with osteoporosis (OP). However, there is uncertainty and hesitation surrounding the optimal sequential order of administering anti-resorptive agents (AR) and anabolic agents (AB). We systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to September 19, 2023 and identified randomised controlled trials comparing sequential treatments for women with PMO. We subsequently identified original studies with the following search terms: “postmenopausal osteoporosis”, “sequential treatment” and “randomised controlled trial” in combination with the terms “diphosphonate”, “bisphosphonate”, “alendronate”, “risedronic acid”, “risedronate”, “ibandronic acid”, “ibandronate”, “zoledronic acid”, “zoledronate”, “raloxifene hydrochloride”, “raloxifene”, “tibolone”, “denosumab”, “teriparatide”, “abaloparatide”, “romosozumab”, “blosozumab”, etc.

Added value of this study

Based on 19 trials and 18,293 participants, we found that sequential treatment transitioning from one AR to another AR (ARtAAR) and treatment switching from AB to AR (ABtAR) are the effective and safe strategies for preventing fracture and improving BMD for PMO. Treatment transitioning from an AR to a combined treatment (ARtC) is more effective in preventing vertebral fractures.

Implications of all the available evidence

The ARtAAR and ABtAR strategy are the effective and safe sequential treatment for preventing fracture and improving BMD for PMO. Global health-care providers, policy makers, and the general public should be aware of the high prevalence of OP. More efforts should be made to explore the order of the sequential osteoporotic treatment and deciding effectively sequential strategies in the early stages of the disease.

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a systemic skeletal disease characterised by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration in bone tissue, all of which increase bone fragility and risk of bone fracture.1 The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported that 9.9 million American women aged 50 and older suffered from OP in 2010,2 and this number is expected to increase to 13.2 million by 2030.3 Data indicate that 20–30% of patients die within a year after developing hip fracture,4 and the direct annual cost of treating osteoporotic fractures is estimated to be in the range of USD 5000–6500 billion.5 A large number of patients with OP have a long survival duration following the initial diagnosis and require long-term treatment.6 The currently used treatments have poor clinical outcomes in some patients. Indeed, some still experience multiple fractures or loss of bone mineral density (BMD).6

Currently, many guidelines recommend sequential treatments for patients with OP.7, 8, 9 However, there is uncertainty and hesitation surrounding the optimal sequential order of administering anti-resorptive agents (AR) and anabolic agents (AB). The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis (ESCEO) and the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) guidelines seems to support initiating anti-osteoporotic treatment with AB and following by AR.10,11 However, the recommendation of sequential treatment order in Chinese guidelines is still unclear.

Confronted with multiple sequential options, it is difficult to perform head-to-head randomised controlled trials (RCTs) between every two sequential regimens to determine the optimal treatment.12 Only one meta-analysis suggested that, unlike monotherapy, sequential treatments may increase BMD.12 Considering the inevitability of sequential treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO) and the intricacy associated with sequential regimens, there is a need to search for reliable evidence to guide the clinical selection of different sequential treatments. Here, we conducted a network meta-analysis (NMA) and revealed the differences in efficacy and safety among all types of sequential therapeutic regimens and their ranking probabilities, providing guidance framework for the rational use of drugs in OP treatment.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This study is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statements extension.13,14 All analyses were performed according to the Cochrane Handbook recommendations. The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022360236), and no ethical approval was required for this study.

Investigated interventions

We compared the effectiveness of sequential treatments involving the switch from AR to AB or another AR (ARtAB or ARtAAR), from AB to AR or another AB (ABtAR or ABtAAB), from a single agent to the combination treatment of AB and AR (ARtC or ABtC), or from combination treatment to a single agent (CtAB or CtAR).

Outcomes measures

The primary outcomes of interest were vertebral fracture risk and percentage change in total hip BMD. Secondary outcomes were other fracture risks, BMD changes and safety. Safety outcomes of interest included the incidence of adverse events (AEs) such as all on-treatment events.15,16 Tolerability was defined as discontinuation due to AEs. The sequential treatment approach was divided into two stages based on the switch of therapeutic regimen. The first therapy interval was named as the stage one or the first stage, during which patients receive monotherapy. Subsequently, there is a change and conversion in the type of regimens, leading to the second therapy interval, which was referred as the stage two or the second stage.

Data sources and search

We searched the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library for randomised controlled trials from inception to September 19, 2023. The search terms are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Additional studies were identified by searching the reference lists of the retrieved systematic reviews and clinical guidelines in ClinicalTrials.gov registry (www.clinicaltrials.gov), and through a manual screening of grey literature in Google Scholar and public repositories.

Eligibility criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included: (1) population: PMO (the reporting of sex and gender adhere to SAGER guidelines); (2) intervention: sequential treatments; (3) control: administration with a single anti-osteoporotic agent, including monotherapy with AR (MonoAR), monotherapy with AB (MonoAB); (4) reported one or more results of interest; and (5) study design: RCTs evaluated as evidence I. Studies that met any of the following criteria were excluded: (1) secondary osteoporosis due to androgen deprivation, cancer, or other metabolic factors; (2) non-sequential therapy; (3) non-RCTs or trials without the outcomes of interest; (4) dose or duration of pharmacological intervention not recommended by authoritative guideline.

Study selection

Two reviewers (YXH, YYM) independently screened the extracted literature to identify potentially relevant studies based on pre-formulated inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussions with a third author (JMC), who was not involved in the screening of studies. The original authors were contacted for clarification where necessary, and those of abstract-only studies were contacted for details when needed.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (YXH, JMC) independently extracted data and entered them into a standardised Excel file. The following data were extracted from each study: first author, year of publication, country, study design, interventions, dose and interval of comparisons and controls, trial duration, and outcomes. Multi-arm trials were divided into pairwise groups according to the requirements of the meta-analysis. For studies with two or more stages, we included only the first two stages and excluded the third or subsequent stages. Similarly, for studies with multiple arms and varying doses, we only included the arm that adhered to the recommended dose as per the provided instructions.11,17 Consensus was achieved by discussion with a third reviewer (YYM) when there was disagreement between the two reviewers.

Assessment of the risk of bias

The overall risk of bias was assessed according to the following seven categories: random sequence generation (selection bias); allocation concealment (selection bias); blinding of participants and staff (performance bias); blinding of the outcome assessment (detection bias); incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); and selective reporting (reporting bias).18

Grading quality of evidence

The quality of evidence for primary and secondary outcomes was assessed based on six aspects: risk of bias, heterogeneity, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. All six aspects constitute the methodology of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE), and is assessed using the Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis framework (CINeMA). The quality of evidence was classified as very low, low, moderate, or high.19,20

Statistical analysis

The risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for dichotomous variables, while mean differences (MDs) and 95% CIs were calculated for continuous variables. For data with different units, we calculated standard mean differences (SMDs) and 95% CIs.21 When dichotomous outcome data were missing, it was assumed that participants who dropped out after being randomly assigned did not experience any events, including fractures, adverse reactions, etc.22 For continuous outcome data, we just analysed data on participants who had completed the study.22,23

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC Statistics/Data Analysis StataCorp, TX, USA). NMA within frequentist framework was conducted using mvmeta package. Global inconsistency across different designs of treatment comparisons in the network obtained by a design-by-treatment model was assessed based on p-value.24 The potential inconsistencies between the direct and indirect evidence within the network were evaluated by using the loop-specific approach and identified local inconsistencies by using the node-splitting technique.25 If there was inconsistency in multiple comparisons, the NMA will be not applicative.26 Given that heterogeneity in all treatment comparisons was comparable and that correlation caused by multi-arm trials, the random effects model was adopted. Intervention ranking was conducted by analyzing the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA). Publication bias was assessed by visually inspecting a funnel plot and through the Egger’s test. If publication bias was identified, meta-trim with the fill-and-trim method was used to correct possible publication bias.27,28 All tests were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered significant unless otherwise stated.

Ethics

All data used in this NMA is publicly available, ethics committee approval or patient consent for publication was not needed.

Role of the funding source

All authors had full access to all the data in this study, and responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The funder of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

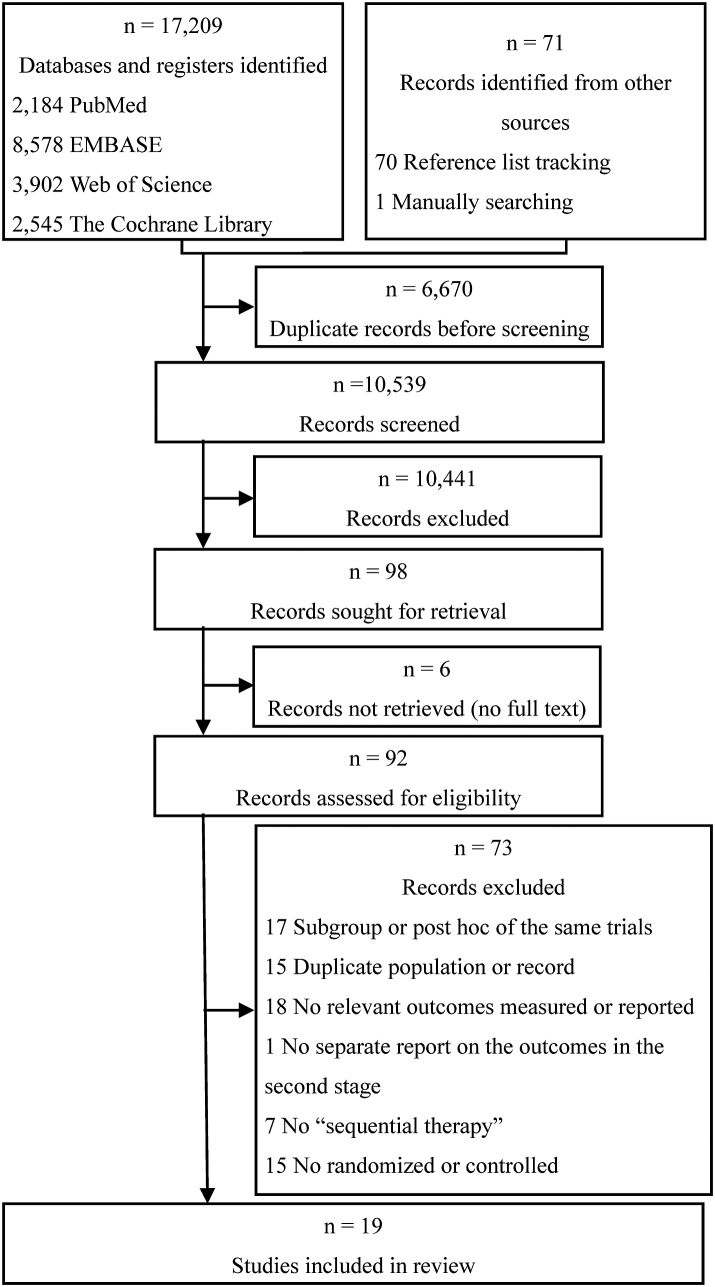

Of the 17,209 records initially identify during the search, we excluded 6670 duplicate records and 10,520 records which did not match the inclusion criteria as determined from their titles and abstracts. Finally, 19 trials29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 in 27 publications29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 were included after reading the full text (Fig. 1). Studies excluded from the full-text assessment are presented in Supplementary Table S2. The third stage of two trials31,41 were excluded according to the previous regulations.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram.

Five therapeutic regimens (ABtAR, ARtAAR, ARtAB, ABtC, ARtC) were recorded as sequential treatments. And two non-sequential treatments with a single agent (MonoAR, MonoAB) were observed in the included trials.

The included trials were published from 2003 to 2021 and comprised 18,416 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 40 to 7180. The mean age of the participants was 71.2 years, the median follow-up time was 12 months for the second stage. Four trials35,42,43,45 had more than two groups. All patients received basal supplements of oral calcium and vitamin D. Two trials34,47 included combination treatments. The full description and characteristics of the studies are presented in Table 1 and supplemented by Supplementary Table S3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all studies and included arms.

| Author (year) | Country | Design (arm) | Sample (n) of study | Mean age (year) | Intervention |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First stage | Category | Duration (months) | Second stage | Category | Duration (months) | |||||

| Iwamoto (2003) | Japan | 2 | 40 | 71.1 | Cyclical etidronate orally | AR | 12 | Alendronate 5 mg daily orally | AR | 6 |

| Cyclical etidronate | AR | 12 | Cyclical etidronate | AR | 6 | |||||

| Ascott-Evans (2003) | South Africa | 2 | 144 | 57.3 | HRT | AR | At least 12 | Alendronate 10 mg daily orally | AR | 12 |

| HRT | AR | At least 12 | Placebo | PLA | 12 | |||||

| Michalska' (2005) | Czech Republic | 3 | 99 | 65.2 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | At least 36 | Raloxifene 60 mg daily orally | AR | 12 |

| Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | At least 36 | Placebo | PLA | 12 | |||||

| Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | At least 36 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | 12 | |||||

| Gonnelli (2006) | Italy | 2 | 60 | 71.1 | AR | AR | At least 12 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 12 |

| AR | AR | At least 12 | Previous antiresorptive treatment | AR | 12 | |||||

| Adami (2008) | Italy | 2 | 380 | 66.9 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 12 | Raloxifene 60 mg day orally | AR | 12 |

| Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 12 | Placebo | PLA | 12 | |||||

| Cosman (2008) | USA | 2 | 42 | 67.0 | Raloxifene 60 mg day orally | AR | At least 12 | PTH (1–34) 25 mg daily sc | AB | 12 |

| Raloxifene 60 mg day orally | AR | At least 12 | Raloxifene 60 mg day orally | AR | 12 | |||||

| Eastell (2009) | UK | 2 | 634 | 69.2 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 12 | Raloxifene 60 mg day orally | AR | 12 |

| Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 12 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 12 | |||||

| Kendler (2009) | Canada | 2 | 504 | 67.6 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | At least 6 | Denosumab 60 mg once every 6 months sc | AR | 12 |

| Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | At least 6 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | 12 | |||||

| Cosman (2009) | USA | 4 | 198 | 68.4 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | At least 20 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally; teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AR combined AB | 18 |

| Raloxifene 60 mg day orally | AR | At least 20 | Raloxifene 60 mg day orally; teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | Combined AR with AB | 18 | |||||

| Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | At least 20 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 18 | |||||

| Raloxifene 60 mg day orally | AR | At least 20 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | ABA | 18 | |||||

| Muschitz (2013) | Austria | 3 | 125 | 71.0 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 9 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally; teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | Combined AR with AB | 9 |

| Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 9 | Raloxifene 60 mg day orally; teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | Combined AR with AB | 9 | |||||

| Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 9 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 9 | |||||

| Bonnick (2013) | USA | 2 | 246 | 71.3 | Alendronate 10 mg daily or 70 mg once weekly | AR | At least 36 | Odanacatib 50 mg once weekly sc | AR | 24 |

| Alendronate 10 mg daily or 70 mg once weekly | AR | At least 36 | Placebo | PLA | 24 | |||||

| Recknor (2013) | USA | 2 | 833 | 66.7 | Bisphosphonate daily or weekly | AR | At least 1 | Denosumab 60 mg once every 6 months sc | AR | 12 |

| Bisphosphonate daily or weekly | AR | At least 1 | Ibandronate 150 mg once monthly orally | AR | 12 | |||||

| Leder (2015) | USA | 2 | 94 | 65.9 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 24 | Denosumab 60 mg once every 6 months sc | AR | 24 |

| Denosumab 60 mg once every 6 months sc | AR | 24 | Teriparatide 20 μg daily sc | AB | 24 | |||||

| Cosman (2016) | USA | 2 | 7180 | 70.8 | Romosozumab 210 mg once monthly sc | AB | 12 | Denosumab 60 mg once every 6 months sc | AR | 12 |

| Placebo | PLA | 12 | Denosumab 60 mg once every 6 months sc | AR | 12 | |||||

| Miller (2016) | USA | 2 | 643 | 69.0 | Bisphosphonate orally | AR | At least 24 | Denosumab 60 mg once every 6 months sc | AR | 12 |

| Bisphosphonate orally | AR | At least 24 | Zoledronic acid 5 mg once a year iv | AR | 12 | |||||

| Saag (2017) | USA | 2 | 4093 | 74.3 | Romosozumab 210 mg once monthly sc | AB | 12 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | At least 12 |

| Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | 12 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | At least 12 | |||||

| Bone (2018) | USA | 2 | 1645 | 68.5 | Abaloparatide 80 mg daily sc | AB | 18 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | 24 |

| Placebo | PLA | 18 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | 24 | |||||

| McClung (2018) | USA | 7 | 471 | 66.7 | Alendronate 70 mg once weekly orally | AR | 12 | Romosozumab 140 mg once monthly sc | AB | 12 |

| Romosozumab 210 mg once monthly sc | AB | 12 | Romosozumab 210 mg once monthly sc | AB | 12 | |||||

| Romosozumab 210 mg once monthly sc | AB | 24 | Denosumab 60 mg once every 6 months sc | AR | 12 | |||||

| Romosozumab 210 mg once monthly sc | AB | 24 | Placebo | PLA | 12 | |||||

| Placebo | PLA | 24 | Denosumab 60 mg once every 6 months sc | AR | 12 | |||||

| Hagino (2021) | Japan | 2 | 985 | 81.5 | Teriparatide 56.5 μg once weekly sc | AB | 18 | Alendronate | AR | 12 |

| Alendronate | AR | 18 | Alendronate | AR | 12 | |||||

AR: anti-resorptive agent; AB: anabolic agent; PLA: placebo; sc: subcutaneous injection; iv: intravenous injection; More details were listed in Supplementary Data (Supplementary Table S3).

Efficacy

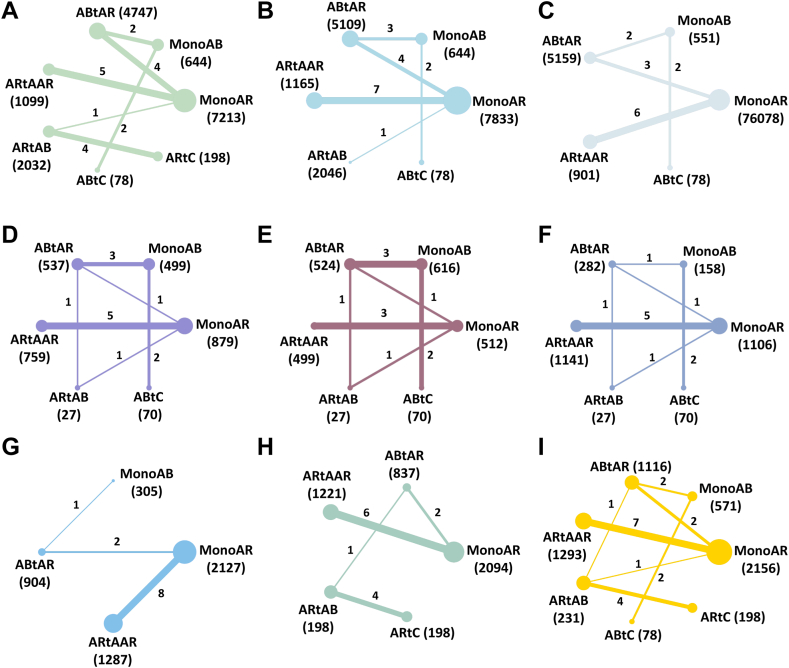

All network plots of the pre-determined outcomes were starry or radiate (Fig. 2). Both direct and indirect evidence demonstrated consistency and heterogeneity across the analysis, indicating robustness and reliability of the findings.

Fig. 2.

Network of all outcomes in the second stage. The width of the lines is proportional to the number of trials comparing each pair of treatments. The size of the nodes is proportional to the number of randomised participants. A: Incidence of vertebral fractures; B: Incidence of non-vertebral fractures; C: Incidence of total fractures; D: The percentage change of lumbar spine BMD; E: The percentage change of femoral neck BMD; F: The percentage change of total hip BMD; G: Incidence of adverse events; H: Incidence of serious adverse events; I: Tolerability. MonoAR: monotherapy with an anti-resorptive agent; MonoAB: monotherapy with an anabolic agent; ABtAR: treatment switching from an anabolic agent to an anti-resorptive agent; ARtAAR: treatment switching from an anti-resorptive agent to another anti-resorptive agent; ARtAB: treatment switching from an anti-resorptive agent to an anabolic agent; ABtC: treatment switching from an anabolic agent to the combined treatment of anti-resorptive and anabolic agent; ARtC: treatment switching from anti-resorptive agent to the combined treatment of anti-resorptive and anabolic agent; BMD: bone mineral density.

Incidence of fractures

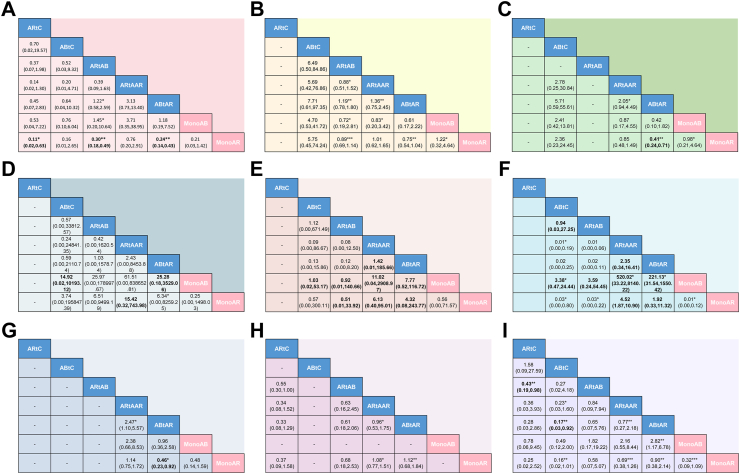

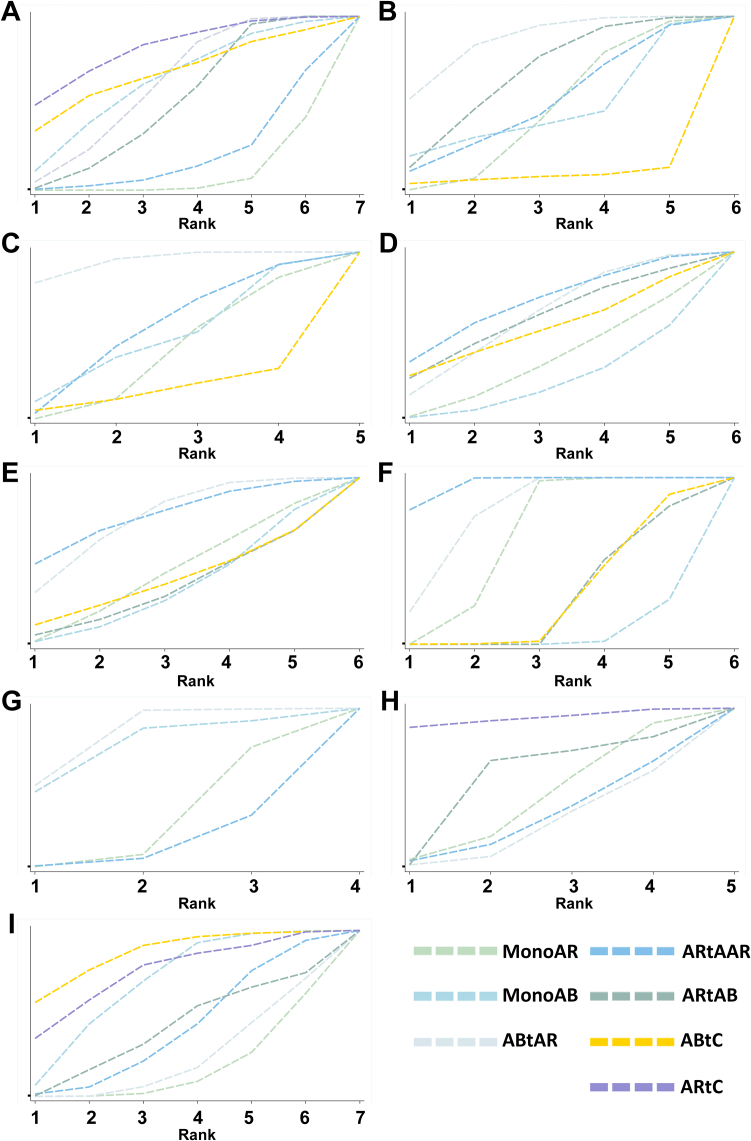

For assessing vertebral fracture risk, 14 trials involving seven different interventions and a combined participant population of 15,586 were included. The included population of MonoAR, MonoAB, ABtAR, ARtAAR, ARtAB, ABtC and ARtC were 7213, 644, 4747, 1099, 2032, 78 and 198 (Fig. 2A). The ABtAR vs. MonoAR, ARtAAR vs. MonoAR, ARtAB vs. MonoAR, ABtAR vs. MonoAB, ABtC vs. MonoAB, ARtAB vs. ARtC group involved 4, 5, 1, 2, 2, 4 trials (Fig. 2A). Analysis of the estimated effects revealed that the intervention ARtC exhibited a significantly lower risk of vertebral fractures compared to other interventions (Fig. 3A). Compared with the MonoAR group, ARtC, ABtAR, and ARtAB were more effective in reducing the incidence of vertebral fractures (ARtC: RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.02–0.63, low certainty of evidence; ARtAB: RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.18–0.49, moderate; ABtAR: RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.14–0.43, moderate), and ARtC was the best treatment (SUCRA 81.5%) for preventing vertebral fractures in stage two (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 3.

Network league of outcomes including efficacy and safety in the second stage. Comparison among groups should be read from left to right. Efficacy and safety estimates are located at the intersection between the column-defining treatment and the row-defining treatment. For changes in BMD, data are presented as the MD (95% CI), and data above 0 favour the treatment closer to the outside in corresponding quarter area. For other outcomes, data are presented as the RR (95% CI), and data below 1 favour the treatment closer to the outside in corresponding quarter area. The certainty of the evidence (according to confidence in network meta-analysis [CINeMA]) is displayed as footnotes. A: Incidence of vertebral fractures; B: Incidence of non-vertebral fractures; C: Incidence of total fractures; D: The percentage change of lumbar spine BMD; E: The percentage change of femoral neck BMD; F: The percentage change of total hip BMD; G: Incidence of adverse events; H: Incidence of serious adverse events; I: Tolerability. MonoAR: monotherapy with an anti-resorptive agent; MonoAB: monotherapy with an anabolic agent; ABtAR: treatment switching from an anabolic agent to an anti-resorptive agent; ARtAAR: treatment switching from an anti-resorptive agent to another anti-resorptive agent; ARtAB: treatment switching from an anti-resorptive agent to an anabolic agent; ABtC: treatment switching from an anabolic agent to the combined treatment of anti-resorptive and anabolic agent; ARtC: treatment switching from anti-resorptive agent to the combined treatment of anti-resorptive and anabolic agent; BMD: bone mineral density; MD: mean deviation; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; CINeMA: Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis framework. ∗Low certainty of evidence; ∗∗Moderate certainty of evidence; ∗∗∗High certainty of evidence.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative rank plot for efficacy and safety outcomes. The rank indicates the probability to be the best treatment, the second best, and so on, among the different interventions under evaluation. A larger SUCRA score indicates high efficacy of the intervention. A: Incidence of vertebral fractures; B: Incidence of non-vertebral fractures; C: Incidence of total fractures; D: The percentage change of lumbar spine BMD; E: The percentage change of femoral neck BMD; F: The percentage change of total hip BMD; G: Incidence of adverse events; H: Incidence of serious adverse events; I: Tolerability. MonoAR: monotherapy with an anti-resorptive agent; MonoAB: monotherapy with an anabolic agent; ABtAR: treatment switching from an anabolic agent to an anti-resorptive agent; ARtAAR: treatment switching from an anti-resorptive agent to another anti-resorptive agent; ARtAB: treatment switching from an anti-resorptive agent to an anabolic agent; ABtC: treatment switching from an anabolic agent to the combined treatment of anti-resorptive and anabolic agent; ARtC: treatment switching from anti-resorptive agent to the combined treatment of anti-resorptive and anabolic agent; SUCRA: surface under the cumulative ranking curve; BMD: bone mineral density.

In our analysis, we included a total of 14 trials reporting the occurrence of non-vertebral fractures in the second stage and encompassing a participant population of 16,615 individuals. The MonoAR, MonoAB, ABtAR, ARtAAR, ARtAB and ABtC group included 7833, 644, 5109, 1165, 2046 and 78 patients. The comparison between ABtAR and MonoAR, ARtAAR and MonoAR, ARtAB and MonoAR, ABtAR and MonoAB, ABtC and MonoAB involved 4, 7, 1, 3, 2 trials (Fig. 2B). Results indicated that ABtAR was the most effective regimen in reducing non-vertebral fractures with the biggest SUCRA of 86.0% (Fig. 4B), although it was not significantly different with other interventions (Fig. 3B).

In total, 12 trials (five interventions; 13,040 participants) reported the incidence of total fractures. The number of patients in the MonoAR, MonoAB, ABtAR, ARtAAR, ABtC group were 6078, 551, 5159, 901 and 78 (Fig. 2C). The included trials between ABtAR and MonoAR, ARtAAR and MonoAR, ABtAR and MonoAB, ABtC and MonoAB were 3, 6, 2, 2 (Fig. 2C). The total fracture risk in the ABtAR group was lower than the MonoAR (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.24–0.71; moderate) (Fig. 3C). The data revealed that ABtAR was best suited to reduce total fractures (SUCRA: 94.3%) (Fig. 4C).

Change percentage of BMD

In the second stage, 2577 participants from 11 trials were enrolled for further analysis of lumbar spine BMD. The included population of MonoAR, MonoAB, ABtAR, ARtAAR, ARtAB, and ABtC were 879, 499, 537, 759, 27 and 70 (Fig. 2D). The ABtAR vs. MonoAR, ARtAAR vs. MonoAR, ARtAB vs. MonoAR, ABtAR vs. MonoAB, ABtC vs. MonoAB, ARtAB vs. ABtAR group involved 1, 5, 1, 3, 2, 1 trial (Fig. 2D). The estimated effects indicated that ARtAAR was more effective in improving lumbar spine BMD with 15.42 percent change, compared with MonoAR (95% CI 0.32–743.98, very low) (Fig. 3D). Compared with MonoAB, the ABtC and ABtAR group also had a higher improvement in lumbar spine BMD (ABtC: MD 14.92, very low; MonoAB: MD 25.28, very low) (Fig. 3D). SUCRA cumulative probability indicated that ARtAAR caused the most significant change in lumbar spine BMD with the maximum SUCRA of 69.4% (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 2E shows the results of the NMA for percent BMD change in femoral neck based on 9 trials (six interventions) and 2064 participants. The MonoAR, MonoAB, ABtAR, ARtAAR, ARtAB and ABtC group included 512, 616, 524, 499, 27 and 70 patients. The comparison between ABtAR and MonoAR, ARtAAR and MonoAR, ARtAB and MonoAR, ABtAR and MonoAB, ABtC and MonoAB, ARtAB and ABtAR involved 1, 3, 1, 3, 2, 1 trial. In general, ARtAAR was superior to other treatments in improving femoral neck BMD with 77.3% probability according to SUCRA cumulative sorted results (Fig. 4E), the comparisons with ABtAR, MonoAB, MonoAR also showed significant differences (ABtAR: MD 1.42, 95% CI 0.01–185.66, very low; MonoAB: MD 11.02, 95% CI 0.04–2908.97, very low; MonoAR: MD 6.13, 95% CI 0.40–95.01, very low) (Fig. 3E).

Nine trials collected data on total hip BMD change, including six interventions and 2600 participants. The MonoAR, MonoAB, ABtAR, ARtAAR, ARtAB and ABtC group included 1106, 158, 282, 1141, 27 and 70 patients (Fig. 2F). The comparison between ABtAR and MonoAR, ARtAAR and MonoAR, ARtAB and MonoAR, ABtAR and MonoAB, ABtC and MonoAB, ARtAB and ABtAR involved 1, 5, 1, 1, 2, 1 trial (Fig. 2F). It was estimated that ARtAAR increased the percent change in total hip BMD by approximately 4.52 (95% CI 1.87–10.90, very low) compared to MonoAR, by 520.02 (95% CI 33.22–8140.22, low) compared to MonoAB, by 2.35 (95% CI 0.34–16.41, very low) compared to ABtAR (Fig. 3F). The comparisons between all sequential treatments and MonoAB, ABtAR and MonnoAR, ABtC and ARtAB both had significantly difference (ABtC vs. MonoAB: MD 3.38, low; ARtAB vs. MonoAB: MD 3.59, very low; ABtAR vs. MonoAB: MD 221.13, low; ABtAR vs. MonoAR: MD 1.92, very low; ABtC vs. ARtAB: MD 0.94, very low). ARtAAR improved total hip BMD with the highest 96.1% probability.

Safety

Adverse events

Ten trials (three interventions, 4590 participants) which reported AEs in the second stage were included. The included population of MonoAR, MonoAB, ABtAR, ARtAAR were 2127, 305, 904 and 1287 (Fig. 2G). The ABtAR vs. MonoAR, ARtAAR vs. MonoAR, ABtAR vs. MonoAB group involved 2, 8 and 1 trials (Fig. 2G). The incidence of stage two AEs was lowest in the ABtAR group (SUCRA 83.2%) compared with the ARtAAR and monotherapy groups (Fig. 4G).

Ten trials (five interventions, 4350 participants) reported the incidence of serious AEs. The included population of MonoAR, ABtAR, ARtAAR, ARtAB and ARtC were 2094, 837, 1221, 198 and 198 (Fig. 2H). The ABtAR vs. MonoAR, ARtAAR vs. MonoAR, ARtAB vs. ABtAR, ARtC vs. ARtAB group involved 2, 6, 1 and 4 trials (Fig. 2H). The data showed that ARtC (SUCRA 93.8%) had a lower incidence, followed by ARtAB, MonoAR, ARtAAR, and ABtAR (Fig. 4H).

Tolerability

In total, 15 trials with seven interventions and 5365 participants reported tolerability. The included population of MonoAR, MonoAB, ABtAR, ARtAAR, ARtAB, ABtC and ARtC were 2156, 571, 1116, 1293, 231, 78 and 198 (Fig. 2I). The ABtAR vs. MonoAR, ARtAAR vs. MonoAR, ARtAB vs. MonoAR, ABtAR vs. MonoAB, ABtC vs. MonoAB, ARtAB vs. ABtAR, ARtC vs. ARtAB group involved 2, 7, 1, 2, 2, 1 and 4 trials (Fig. 2I). Analysis results of SUCRA cumulative probability revealed that ABtC (SUCRA 86.2%) had the lowest proportion of discontinuations (Fig. 4I).

Overall outcomes of the whole stage

In the whole stage, ABtAR was more valuable in avoiding all fractures and improved femoral neck BMD, ABtC could maintain the BMD of lumbar spine and total hip, which has reference significance for patients with severe osteoporosis who need to plan sequential treatment from the beginning. More details were supplemented in Supplementary Table S4.

Evaluation of evidence quality

Global and local inconsistency

No global and local inconsistency of other outcomes was observed (p < 0.05), which means the reliability of all results and applicability of this NMA. The assessment of inconsistency for each outcome is reported in Supplementary Tables S5 and S6.

Public bias

Supplementary Figures S1–S9 and Table S7 in the Supplement show the funnel plots and the p-value of Eggers’ test for all outcomes. Partial funnel plots of outcomes were symmetrical except for the incidence of vertebral fractures and total fractures, the percent change in lumbar spine BMD and total hip BMD. In Eggers’ test, the p-value for the occurrence of vertebral fractures was less than 0.05 (p = 0.019). The results did not change after the meta-trim test.

Quality of evidence

The certainty of the evidence for each outcome, as measured by CINeMA, varied from high to very low (overall, sixteen comparisons scored high or moderate results). Most comparisons involving ARtAB, ABtAR, and ARtAAR were rated low or higher, and comparisons involving ARtC and ABtC were rated very low. The risk of bias (RoB) chart for all included studies is shown in Supplementary Figure S10. In contrast, the contribution of low, moderate, or high RoB comparisons is shown in Supplementary Figures S11–S19. Complete information on CINeMA is described in Supplementary Tables S8–S16.

Discussion

Monotherapy options for PMO have increased considerably in the past 20 years. Although effective, relatively safe, and affordable monotherapies are available,56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 the sequential and combination treatment of patients needs to be looked at and the best regimens identified. We summarised all results in the Table 2. Our study suggested that ABtAR and ARtAAR were almost associated with all significant fracture reduction and BMD improvement compared with non-sequential regimens after treatment switching. Combination treatment after AB was more effective in the lumbar spine, because it could improve the percentage change of BMD in this part and reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures. ARtAB reduced non-vertebral fractures and improved the lumbar spine BMD compared with non-sequential regimens. Based on NMA, ARtC ranked the first in decreasing the incidence of vertebral fractures in the second stage, although the unavailability of data on other outcomes made it difficult for us to fully understand the efficacy of this regimen.

Table 2.

Sorted table bases on SUCRA value for all outcomes in the second stage.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence of fractures | |||||||

| VFs | ARtC | ABtC | MonoAB | ABtAR | ARtAB | ARtAAR | MonoAR |

| NVFs | ABtAR | ARtAB | ARtAAR | MonoAR | MonoAB | ABtC | – |

| TFs | ABtAR | ARtAAR | MonoAB | MonoAR | ABtC | – | – |

| Percentage change of BMD | |||||||

| LS | ARtAAR | ABtAR | ARtAB | ABtC | MonoAR | MonoAB | – |

| FN | ARtAAR | ABtAR | MonoAR | ABtC | MonoAB | ARtAB | – |

| TH | ARtAAR | ABtAR | MonoAR | ABtC | ARtAB | MonoAB | – |

| Safety indicators | |||||||

| AEs | ABtAR | MonoAB | MonoAR | ARtAAR | – | – | – |

| Serious AEs | ARtC | ARtAB | MonoAR | ARtAAR | ABtAR | – | – |

| Tolerability | ABtC | ARtC | MonoAB | ARtAAR | ARtAB | ABtAR | MonoAR |

VFs: vertebral fractures; NVFs: non-vertebral fractures; TFs: total fractures; LS: lumbar spine; FN: femoral neck; TH: total hip; AEs: adverse events; MonoAR: monotherapy with an anti-resorptive agent; MonoAB: monotherapy with an anabolic agent; ABtAR: treatment switching from an anabolic agent to an anti-resorptive agent; ARtAAR: treatment switching from an anti-resorptive agent to another anti-resorptive agent; ARtAB: treatment switching from an anti-resorptive agent to an anabolic agent; ABtC: treatment switching from an anabolic agent to the combined treatment of anti-resorptive and anabolic agent; ARtC: treatment switching from anti-resorptive agent to the combined treatment of anti-resorptive and anabolic agent.

The available safety data indicated that all comparisons had no significant difference. Compared with ARtAB, ARtC were associated with lower odds of discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events, similar results also appeared in the comparison between ABtC and ABtAR. In fact, the combination treatments in the second stage would not lead to lower participants compliance. By SUCRA probabilities, the sequential treatments least likely to be associated with discontinuation because of adverse events were ARtC and ABtC.

Our study has suggested the relative efficacy of all available sequential anti-osteoporosis treatments for PMO. In clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF) emphasised that therapy with combination or sequential use of anti-fracture medications may be warranted for patients with recent fractures and/or very low BMD (e.g., T-score < −3.0).8 The BHOF document summarised that the order in which anti-fracture agents can significantly influence the BMD and fracture outcomes. An AB administered following AR has demonstrably less impact on BMD and more bone loss than if the anabolic is administered first.41,67, 68, 69, 70 This can also be explained from the perspective of bone microstructure. ABs have the potential to restore or even enhance the rate of bone remodeling during the early stages. Upon discontinuation of AB administration or reaching their regulatory limit, the subsequent utilization of sequential ARs demonstrates a deceleration in bone remodeling, resulting in a reduced rate of bone volume decline and microstructural deterioration. This phenomenon elucidates how ARs effectively sustain elevated levels of BMD and minimise the incidence of fractures.71,72 This explanation seems plausible. Studies have demonstrated that ARs do not restore bone volume or repair microstructural deterioration in the initial stage, resulting in irreversible deficits caused by rapid remodeling imbalance. This initial treatment appears to have a “blunted” response, which inhibits its effect on the remodeling recovery following sequential ABs.72 This may explain the acceleration in bone loss when treatment is switched from ARs to ABs.46,73 This has been a controversial point widely discussed in the literature; thus, more studies are needed to address this issue. In addition, there are limited indications for combining two antiresorptive treatments. Although our evidence suggests its effectiveness compared to non-sequential treatments.

There is paucity of direct comparative trials which are needed to confirm indirect comparisons obtained through NMA. On the other hand, the risk of bias in the available trials was judged to be low. The fact that the attrition rates in the sequential treatment arms and monotherapy groups were similar is nevertheless reassuring that dropout is less likely to lead to important bias in the assessment of efficacy or adverse events. Risk of bias was high or unclear for random sequence generation (57.9%), and incomplete outcome data (5.3%). No public bias, global and local inconsistency was reported.

To our knowledge, this study is the first and most comprehensive data synthesis on sequential treatments for women with PMO. Our findings provide robust evidence supporting the use of rational medication in clinical sequential treatment practices. The present results will serve as a valuable reference for guiding decision-making for patients, caregivers, clinicians, guideline developers, and policymakers. This analysis lies in the pre-planned parallel comparison of the incidence of fractures as primary outcomes in a homogeneous group of participants.

Despite the success demonstrated, this study had several limitations. First, the included studies have some differences in specific types, dosage and duration of agents and adjuvants, which may affect the results of this study. Second, almost all outcomes include less direct studies, mainly due to limited RCTs for sequential treatments. Some comparisons rely on indirect evidence and are based on assumptions of unverifiable consistency, limiting the reliability of the results. According to CINeMA, the comparisons are rated as low or very low quality, which restricts the interpretation of these results.

Certainly, individualised treatment for osteoporosis must be valued. The severity of osteoporosis, reaching a treatment goal, and responding to treatment failure are important factors determining the treatment sequence in the individual patient. We also need a comprehensive consideration with its cost and benefits when selecting specific drugs for sequential treatments.74 Therefore, more cost-effectiveness studies are urgently needed to assist and guide clinical physicians in rational medication arrangement.

In summary, in our analysis among women with PMO, ABtAR and ARtAAR can reduce the incidence of fractures and improve the BMD, ABtC just protect lumbar spine part, the data of ARtC and ARtAB need to be further supplied. This analysis, as well as future studies replicating these findings, may inform clinical practice as well as guidelines and policies with regards to sequential treatment of osteoporosis.

Contributors

HDZ and YXH were responsible for the conceptualisation and were actively involved in planning the methodology. YXH contributed to the formal analysis, investigation, project administration, visualisation and writing of the original draft. HXW, JI, LL, YHB, FX, HLJ and YW provided critical advice. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript. HDZ, YYM and JMC accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data and responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding authors had final responsibility for the final decision.

Data sharing statement

Data are presented in the current manuscript, its Supplementary Materials, or within the manuscripts or appendices of the included studies.

Declaration of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170900, 81970762), the Hunan Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and the Hunan Province High-level Health Talents "225" Project.

Footnotes

Translation: For the Chinese translation of the abstract see Supplementary Materials section.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102425.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Eastell R. Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):736–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803123381107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright N.C., Looker A.C., Saag K.G., et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curry S.J., Krist A.H., Owens D.K., et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brauer C.A., Coca-Perraillon M., Cutler D.M., Rosen A.B. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1573–1579. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rashki Kemmak A., Rezapour A., Jahangiri R., Nikjoo S., Farabi H., Soleimanpour S. Economic burden of osteoporosis in the world: a systematic review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2020;34:154. doi: 10.34171/mjiri.34.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langdahl B. Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis with bone-forming and antiresorptive treatments: combined and sequential approaches. Bone. 2020;139 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ACOG Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines–Gynecology Management of postmenopausal osteoporosis: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 2. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139(4):698–717. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeBoff M.S., Greenspan S.L., Insogna K.L., et al. The clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33(10):2049–2102. doi: 10.1007/s00198-021-05900-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid I.R., Billington E.O. Drug therapy for osteoporosis in older adults. Lancet. 2022;399(10329):1080–1092. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camacho P.M., Petak S.M., Binkley N., et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2020 update. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(Suppl 1):1–46. doi: 10.4158/GL-2020-0524SUPPL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanis J.A., Cooper C., Rizzoli R., Reginster J.Y. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(1):3–44. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4704-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lou S., Lv H., Wang G., et al. The effect of sequential therapy for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine. 2016;95(49) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutton B., Salanti G., Caldwell D.M., et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777–784. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fink H.A., MacDonald R., Forte M.L., et al. Long-term drug therapy and drug discontinuations and holidays for osteoporosis fracture prevention: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(1):37–50. doi: 10.7326/M19-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J., Zhang Q., Yan G., Jin X. Denosumab compared to bisphosphonates to treat postmenopausal osteoporosis: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):194. doi: 10.1186/s13018-018-0865-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eastell R., Rosen C.J., Black D.M., Cheung A.M., Murad M.H., Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society∗Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1595–1622. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-00221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins J.P., Altman D.G., Gøtzsche P.C., et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkins D., Best D., Briss P.A., et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikolakopoulou A., Higgins J.P.T., Papakonstantinou T., et al. CINeMA: an approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Crescenzo F., D'Alò G.L., Ostinelli E.G., et al. Comparative effects of pharmacological interventions for the acute and long-term management of insomnia disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2022;400(10347):170–184. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furukawa T.A., Barbui C., Cipriani A., Brambilla P., Watanabe N. Imputing missing standard deviations in meta-analyses can provide accurate results. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(1):7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krahn U., Binder H., König J. A graphical tool for locating inconsistency in network meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dias S., Welton N.J., Caldwell D.M., Ades A.E. Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2010;29(7–8):932–944. doi: 10.1002/sim.3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shim S.R., Kim S.J., Lee J., Rücker G. Network meta-analysis: application and practice using R software. Epidemiol Health. 2019;41 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2019013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alimoradi Z., Abdi F., Gozal D., Pakpour A.H. Estimation of sleep problems among pregnant women during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adami S., San Martin J., Muñoz-Torres M., et al. Effect of raloxifene after recombinant teriparatide [hPTH(1-34)] treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(1):87–94. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0485-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ascott-Evans B.H., Guanabens N., Kivinen S., et al. Alendronate prevents loss of bone density associated with discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(7):789–794. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bone H.G., Cosman F., Miller P.D., et al. ACTIVExtend: 24 months of alendronate after 18 months of abaloparatide or placebo for postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(8):2949–2957. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonnick S., De Villiers T., Odio A., et al. Effects of odanacatib on BMD and safety in the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women previously treated with alendronate: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):4727–4735. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cosman F., Crittenden D.B., Adachi J.D., et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1532–1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cosman F., Nieves J.W., Zion M., Barbuto N., Lindsay R. Effect of prior and ongoing raloxifene therapy on response to PTH and maintenance of BMD after PTH therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(4):529–535. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cosman F., Wermers R.A., Recknor C., et al. Effects of teriparatide in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis on prior alendronate or raloxifene: differences between stopping and continuing the antiresorptive agent. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(10):3772–3780. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eastell R., Nickelsen T., Marin F., et al. Sequential treatment of severe postmenopausal osteoporosis after teriparatide: final results of the randomized, controlled European Study of Forsteo (EUROFORS) J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(4):726–736. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonnelli S., Martini G., Caffarelli C., et al. Teriparatide's effects on quantitative ultrasound parameters and bone density in women with established osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(10):1524–1531. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagino H., Sugimoto T., Tanaka S., et al. A randomized, controlled trial of once-weekly teriparatide injection versus alendronate in patients at high risk of osteoporotic fracture: primary results of the Japanese Osteoporosis Intervention Trial-05. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(11):2301–2311. doi: 10.1007/s00198-021-05996-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwamoto J., Takeda T., Ichimura S., Uzawa M. Early response to alendronate after treatment with etidronate in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Keio J Med. 2003;52(2):113–119. doi: 10.2302/kjm.52.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kendler D.L., Roux C., Benhamou C.L., et al. Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal women transitioning from alendronate therapy. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(1):72–81. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leder B.Z., Tsai J.N., Uihlein A.V., et al. Denosumab and teriparatide transitions in postmenopausal osteoporosis (the DATA-Switch study): extension of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1147–1155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61120-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McClung M.R., Brown J.P., Diez-Perez A., et al. Effects of 24 months of treatment with romosozumab followed by 12 months of denosumab or placebo in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density: a randomized, double-blind, phase 2, parallel group study. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(8):1397–1406. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michalská D., Stepan J.J., Basson B.R., Pavo I. The effect of raloxifene after discontinuation of long-term alendronate treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(3):870–877. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller P.D., Pannacciulli N., Brown J.P., et al. Denosumab or zoledronic acid in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis previously treated with oral bisphosphonates. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(8):3163–3170. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muschitz C., Kocijan R., Fahrleitner-Pammer A., Lung S., Resch H. Antiresorptives overlapping ongoing teriparatide treatment result in additional increases in bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(1):196–205. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Recknor C., Czerwinski E., Bone H.G., et al. Denosumab compared with ibandronate in postmenopausal women previously treated with bisphosphonate therapy: a randomized open-label trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(6):1291–1299. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318291718c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saag K.G., Petersen J., Brandi M.L., et al. Romosozumab or alendronate for fracture prevention in women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1417–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leder B.Z., Mitlak B., Hu M.Y., Hattersley G., Bockman R.S. Effect of abaloparatide vs alendronate on fracture risk reduction in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(3):938–943. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leder B.Z., Tsai J.N., Uihlein A.V., et al. Two years of denosumab and teriparatide administration in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (The DATA Extension Study): a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(5):1694–1700. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McClung M.R., Bolognese M.A., Brown J.P., et al. A single dose of zoledronate preserves bone mineral density for up to 2 years after a second course of romosozumab. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(11):2231–2241. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05502-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McClung M.R., Grauer A., Boonen S., et al. Romosozumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(5):412–420. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McClung M.R., Lewiecki E.M., Geller M.L., et al. Effect of denosumab on bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone turnover: 8-year results of a phase 2 clinical trial. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):227–235. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller P.D., Hattersley G., Riis B.J., et al. Effect of abaloparatide vs placebo on new vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(7):722–733. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mori S., Hagino H., Sugimoto T., et al. Sequential therapy with once-weekly teriparatide injection followed by alendronate versus monotherapy with alendronate alone in patients at high risk of osteoporotic fracture: final results of the Japanese Osteoporosis Intervention Trial-05. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34(1):189–199. doi: 10.1007/s00198-022-06570-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsai J.N., Uihlein A.V., Lee H., et al. Teriparatide and denosumab, alone or combined, in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: the data study randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9886):50–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60856-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Choo Y.W., Mohd Tahir N.A., Mohamed Said M.S., Li S.C., Makmor Bakry M. Cost-effectiveness of denosumab for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Malaysia. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33(9):1909–1923. doi: 10.1007/s00198-022-06444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Händel M.N., Cardoso I., von Bülow C., et al. Fracture risk reduction and safety by osteoporosis treatment compared with placebo or active comparator in postmenopausal women: systematic review, network meta-analysis, and meta-regression analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 2023;381 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hiligsmann M., Maggi S., Veronese N., Sartori L., Reginster J.Y. Cost-effectiveness of buffered soluble alendronate 70 mg effervescent tablet for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in Italy. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(3):595–606. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05802-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang Q., Zhang F., Zhu B., Zhang H., Han L., Liu X. Comparative efficacy between monoclonal antibodies and conventional drugs in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a network meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(2):1693–1702. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin S.Y., Hung M.C., Chang S.F., Tsuang F.Y., Chang J.Z., Sun J.S. Efficacy and safety of postmenopausal osteoporosis treatments: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Med. 2021;10(14):3043. doi: 10.3390/jcm10143043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luo M.H., Zhao J.L., Xu N.J., et al. Comparative efficacy of Xianling Gubao Capsules in improving bone mineral density in postmenopausal osteoporosis: a network meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.839885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Migliorini F., Maffulli N., Colarossi G., Eschweiler J., Tingart M., Betsch M. Effect of drugs on bone mineral density in postmenopausal osteoporosis: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):533. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02678-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moshi M.R., Nicolopoulos K., Stringer D., Ma N., Jenal M., Vreugdenburg T. The clinical effectiveness of denosumab (Prolia®) for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women, compared to bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM), and placebo: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2023;112(6):631–646. doi: 10.1007/s00223-023-01078-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seeto A.H., Tadrous M., Gebre A.K., et al. Evidence for the cardiovascular effects of osteoporosis treatments in randomized trials of post-menopausal women: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Bone. 2023;167 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2022.116610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang W.Y., Chen L.H., Ma W.J., You R.X. Drug efficacy and safety of denosumab, teriparatide, zoledronic acid, and ibandronic acid for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(17):8253–8268. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202309_33586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei F.L., Gao Q.Y., Zhu K.L., et al. Efficacy and safety of pharmacologic therapies for prevention of osteoporotic vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women. Heliyon. 2023;9(2) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boonen S., Marin F., Obermayer-Pietsch B., et al. Effects of previous antiresorptive therapy on the bone mineral density response to two years of teriparatide treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):852–860. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haas A.V., LeBoff M.S. Osteoanabolic agents for osteoporosis. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2(8):922–932. doi: 10.1210/js.2018-00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller P.D., Delmas P.D., Lindsay R., et al. Early responsiveness of women with osteoporosis to teriparatide after therapy with alendronate or risedronate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(10):3785–3793. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Obermayer-Pietsch B.M., Marin F., McCloskey E.V., et al. Effects of two years of daily teriparatide treatment on BMD in postmenopausal women with severe osteoporosis with and without prior antiresorptive treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(10):1591–1600. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leder B.Z. Optimizing sequential and combined anabolic and antiresorptive osteoporosis therapy. JBMR Plus. 2018;2(2):62–68. doi: 10.1002/jbm4.10041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ramchand S.K., Seeman E. Reduced bone modeling and unbalanced bone remodeling: targets for antiresorptive and anabolic therapy. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2020;262:423–450. doi: 10.1007/164_2020_354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsai J.N., Nishiyama K.K., Lin D., et al. Effects of denosumab and teriparatide transitions on bone microarchitecture and estimated strength: the DATA-Switch HR-pQCT study. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(10):2001–2009. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yu G., Tong S., Liu J., et al. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of sequential treatment for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34(4):641–658. doi: 10.1007/s00198-022-06626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.