Abstract

This study investigates the potential determinants of capital flight from BRICS countries. We use the residual method to estimate capital flight and employ GMM testing approach. We find a surge in the volume of capital flight from BRICS especially in the aftermath of global financial crisis. The empirical results suggest that, past values of the capital flight, real GDP growth rates, exchange rate depreciation, unemployment rate, business confidence index and financial stability indicator as significant factors causing resident capital outflows from BRICS nations. These findings call for an effective policy framework by the fiscal and monetary authorities.

Keywords: Capital flight, Exchange rate, Interest rate, GDP, Financial liberalization

1. Introduction

Capital is considered the engine of economic growth and the most crucial factor responsible for the development of modern societies. The underdeveloped and developing countries suffer the most in case of insufficiency of capital. To create more capital, they have to reduce consumption, which becomes quite impossible in the case of these countries where the rate of consumption is already at a subsistent minimum rate. Therefore, the developing countries in search of capital, borrow from the developed countries which ultimately leads to a rise in external debts resulting in economic crises. Several Asian, African, and Latin American countries borrowed capital heavily from abroad during the 1970s and 1980s. The liberalization processes which started in the late 1980s, led to the relaxation of restrictions and controls on foreign trade and investment. This resulted in a gush of capital from developed countries to developing and emerging countries. Consecutively, scarce capital available in the developing countries also moved to the rich and developed countries, which resulted in capital flight [1].

Capital flight has been a debatable topic of interest and concern for both academicians and policymakers alike, especially in developing countries. There are numerous definitions of capital flight. Capital flight is that portion of abnormal capital outflows that result from future suspicions, fears, and anxiety about economic, financial, and political instabilities [2]. Therefore, domestic investors would tend to channel their funds to some safer havens motivated by a threat or fear of loss of wealth of domestically held assets [3]. has defined capital flight as the moving of property or resources abroad to reduce the loss of their financial wealth resulting from activities in their home country which are mainly government sanctioned. In general, it is associated with the shifting of capital, which is also referred to as resident capital outflow to developed countries. However, several studies argue that normal capital outflows1 should not be considered as capital flight ([2,4,5]). In the case of developed countries, the investors respond to the investment opportunities, while in developing countries they escape because of the persistent risks in the domestic economy [6]. Various studies ([[7], [8], [9], [10]]) have differentiated between the term capital outflow and capital flight by citing that capital flight is illegal flows, while capital outflow is legal flows. According to Ref. [11], currency smuggling, illegal transfers of electronic funds, over-invoicing, and under-invoicing of imports and exports respectively are also means of capital flight.

[12] hold that capital flight is also different from capital export as capital exports act according to the permissions by law. Capital exports do not endanger the economy while, on the contrary, capital flight impoverishes the economy by deteriorating the investment possibilities along with the prospects for further development [13]. Capital is relatively limited in the case of developing countries and on top of that, the transfer of assets creates an additional burden towards the development of these economies. Had it not been for capital flight, the assets could have increased productivity by becoming a part of the domestic economy. In general, it is observed that capital flight is stimulated by unfavorable conditions in a country, like in the case of political turmoil, currency instability, or high inflation. The capital outflow in such a case deters the home economy as it affects the entire financial system of the economy. Thus, the developing countries are the biggest sufferers unlike the developed countries; their financial system is not strong and stable enough to cope with a huge amount of capital flight. This in turn leads to an increase in foreign debts and also triggers the real capital outflow. In addition to that, capital flight erodes the tax base of the domestic economy. Therefore, it adversely impacts the quality as to evade high taxes, the wealthy citizens channel their funds abroad and the poor citizens as usual face the wrath of paying high taxes.

The objective of this study is to investigate the determinants of capital flight from BRICS countries. Considering the importance of capital as an engine of economic growth, the current work focuses on testing three important hypotheses in connection to the definition of capital flight credited to Ref. [2] which are as follows.

H1

Capital flight occurs due to macroeconomic instabilities.

H2

Capital flight is a resultant effect of political instabilities.

H3

Capital flight occurs due to financial instabilities.

BRICS constitute five emerging economies such as Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa which have been playing an important role as leading producers and exporters of goods and services. These countries share common characteristics of fast economic growth, large populations, and potential consumer markets, based on which they have been attracting a good number of investors worldwide. The combined economies of Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC) appear likely to become the largest global economic group by the middle of this century [14]. Despite the immense contribution of these economies to the global trade and economic order, many reports have claimed that capital has been moving from these economies to other havens in the last decade. In the presence of capital flight, a set of emerging nations such as BRICS might encounter a reduction in investment opportunities, lower business confidence, and intensify foreign debts. Therefore, the imperative research question of understanding is “What is the magnitude of capital flight that has siphoned from BRICS nations?” and “What factors are responsible for the exodus of these important resources from BRICS nations?”. In this direction, the current paper unfolds an imperative empirical research question to find a proper solution to robust capital management.

According to a report by Ref. [15], “a record $991 billion was siphoned in 2012 from the world's developing economies, an increase of almost 5 % from 2011.” It further stated that $6.6 trillion was siphoned out of the emerging economies to the developed ones. From this humongous amount, a major share of about $3 trillion was diverted from the BRICS group. According to the report, “China, the world's second-biggest economy, leads the way with an estimated $1.25 trillion leaving its borders illegally over the decade. Russia is the second biggest exporter of illicit money, India is fourth, Brazil seventh and South Africa is twelfth.” Because of its adverse impacts on the economy, it is imperative to understand the determinants of capital flight.

We contribute to the growing literature on international capital flows and finance in multiple ways. Firstly, this study focuses on BRICS nations, and a capital flight study like the present one has not received due attention from scholars. The reason for a study on BRICS is motivated by Ref. [16]. The paper posits that a few larger emerging market economies namely Brazil, Russia, India, and China set to grow more rapidly as compared to the G7 nations. Secondly, we estimate the unrecorded net capital relocated from BRICS nations. We use the broad measure of capital flight by employing the residual method [17]. Until recently, there have been many measures of estimating capital flight. Unlike the method of estimating capital flight proposed by Ref. [18], we have included net foreign equity and debt investments along with net foreign direct investments motivated by Refs. [1,19]. The residual approach of estimating capital flight which we employ in the current paper is more conservative and potentially robust as compared to the other conventional measures [1]. This method is more comprehensive because it captures all such items that cannot be reflected in the officially recorded capital flow information [20]. Because of its popularity, this method has also been recently used by many researchers [21,22].

Thirdly, we use variables representing economic, political stability uncertainty, and financial stability indicators in our analysis. Although the business confidence index remains a leading indicator for investment and growth in an economy [23] this variable is seldom used as a potential determinant among previous capital flight studies. We contribute to the nascent literature by explaining the possible linkage between business confidence and capital flight at large. By departing from the extant literature, we use all three types of variables representing economic, political, and financial stability in our investigation. Finally, the cross-country analysis helps develop policy prescripts on financial integration and measures discussed by the BRICS nations to reduce the magnitude of capital flight during its future summits. Additionally, the outcome of this work will assist in devising effective policy frameworks by fiscal and monetary authorities at local level to address these issues and prevent further capital flight.

Against this backdrop, we study the determinants of capital flight in the BRICS countries by drawing a sample from the period 1997 through 2017. For the empirical analysis, first, we follow one step system GMM method. Furthermore, the GMM approach overcome the problem of downward bias associated with the involvement of a lagged component of the dependent variable as a regressor as compared to the conventional OLS approach. By selecting a set of suitable instrumental variables, this approach is capable of reducing the econometric issue of endogeneity [1]. Second, we employ, Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) estimators to overcome the econometric problems namely autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity and provide a robustness of the GMM estimates. Additionally, the outcome of the FGLS approach is expected to be reliable in the presence of cross-sectional dependency in the model [24]. The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the literature on capital flight. Section 3 describes the theoretical framework and the trends of capital flight are presented in Section 4. Section 5 outlines data and methodology and Section 6 discusses the empirical results and implications of the findings. We conclude the study in the final Section and provide recommendations for future research.

2. Review of literature

Numerous studies have focused on the study of capital flight and its determinants, mostly in the case of developing countries. The most common determinants of capital flight discussed widely are macroeconomic variables such as inflation rate, interest rate differentials, and external borrowing to name a few [8]. studied the determinants of capital flight in low-income Sub-Saharan African countries during 1970-76 and found that capital flight is positively and significantly influenced by external borrowing. The study further suggested that external debt plays an important role in stimulating capital flight. Similar results have been obtained by other researchers such as [25] in their study of capital flight in the Philippines during 1970–1999 [26]. in their study on China during 1993–2003, used innovative accounting techniques and established that change in capital flight is significantly influenced by external debt changes in China. Further, they also established an inverse relationship of capital flight with that rise in foreign investors’ business confidence and growth in real GDP.

[27] investigated the determinants of capital flight in Kenya during 1971–2004 using the OLS technique and also found that external borrowing is the most significant factor. Furthermore, they found other important determinants influencing capital flight in Kenya such as real economic growth, real exchange rate, financial development, and inflation rate. The outcome of their study suggested transparency and accountability on the part of the Government of Kenya to facilitate the management of external borrowings in the country [28]. in their study on Bangladesh and its capital flight during 1973–1999 registered political stability as one of the most important determinants of capital flight. They also found other variables such as higher interest rate differentials, corporate income taxes, and lower GDP growth rates which significantly influence capital flight. In another study conducted in Malaysia by Ref. [29] during 1970–1996, it was found that external borrowing and currency depreciation led to an increase in capital flight. On the other hand, foreign direct investments (FDI) and real GDP growth led to a decrease in capital flight. Likewise [30], studied the determinants responsible for capital flight in China during 1999–2008. The results were quite similar to the studies conducted earlier and additionally, they discovered the role of institutional factors as an important determinant of capital flight.

2.1. Recent review of literature

| Authors' | Coverage | Model | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [31] | 1981–2015; Sub-Saharan Africa |

ARDL | Major causes of capital flight are economic growth rate and external debt. |

| [32] | 1971–2011; Trinidad and Tobago |

OLS and GMM | Capital flight is caused by interest rate differential, GDP growth, lagged external debt and excess liquidity. |

| [33] | 1973–2013; Bangladesh |

OLS | Major causes of capital flight are current account surplus, interest rate differentials, FDI flows, foreign reserves and external debt. |

| [34] | 1986–2015; Ghana |

ARDL | In both long and short run, capital flight is reduced by higher domestic real interest, financial development, real GDP growth rate and good governance. |

| [35] | 1992–2012; Malaysia |

Cointegration and VAR | Major causes of capital flight are CPI, GDP, interest rate and exchange rate. |

| [36] | 2000–2013; Jordan |

OLS | Major causes of capital flight are previous capital flight, external debt, taxes and economic openness. |

| [37] | 1980–2010; Malaysia |

ARDL | Capital flight in the long run is significantly and positively influenced by financial crisis and political risk. |

Note: ARDL: Autoregressive-Distributed Lag; OLS: Ordinary Least Squares; GMM: Generalized Method of Moments; VAR: Vector-autoregression.

Source: Author's Compilation

It is evident from the review of the literature that most of the recent studies focus on the developing and emerging countries. From the studies, it can be witnessed that external borrowing, external public debt, political risk, inflation rate, and interest rate differentials are the most significant determinants of capital flight. Most of the research did not incorporate macroeconomic, political stability, and financial stability indicators which is the major research gap in the existing literature on international capital flows.

3. Theoretical framework

Mainly, two theories are associated with capital flight, namely, the investment-diversion theory and the debt-driven theory. According to the investment-diversion theory, political and macroeconomic instability in developing countries encourages some of the corrupt leaders and wealthy people to drain the funds of the country to developed countries. The funds that could have been utilized by the home economy are transferred to the developed nations for earning higher interest and availing better investment opportunities. This leads to an insufficiency of funds in the home economy which hampers economic growth, employment opportunities, and the level of investment. Due to these adverse conditions, the countries to revive the economy, borrow funds from abroad which leads to indebtedness and external dependency.

On the other hand, according to the debt-driven theory when a country is under external debt, it leads to capital flight. According to the theory, external debt is responsible for capital flight, which in turn can lead to fiscal crisis, devaluation of the exchange rate, and crowding out of domestic capital ([38]; 39)). The theory posits that in the long run, the external debt can hurt the exchange rate if it is not used for generating repayment in terms of foreign exchange. The present analysis of BRICS nations focuses on the macro-economic, political, and financial instabilities as the primary reason for capital flight confirming investment-diversion theory to be more applicable in this case. Following the definition credited to Ref. [2], we estimate the regression equation represented as Eqn. (1):

| (1) |

where CFGDPit is the ratio of capital flight (CF) to gross domestic product (GDP), and CFGDPit-1 denotes lagged term of CF. MEit represents the matrix of macroeconomic variables namely, annual GDP growth rate (GDPGR), change in exchange rates (ΔEXRATE), unemployment rate (UNEMRATE), and Business confidence index (BCI). PSit is a vector of political stability index and FSit variables includes the matrix of financial stability indicators namely liquid assets to deposits and short term funding (LNLADSTF) and Bank Z score (LNZSCORE). The term μt is an unobserved time-specific effect whereas νi represents unobserved country specific effect and, φit is a zero mean random disturbance term with variance σv2. The choice of all independent variables included in our analysis is based on the theoretical relevance, and availability of the data.

4. Trend analysis and some Stylized facts

The capital flight from BRICS nations shows a volatile trend (Fig. 1). The highest ever capital flight recorded in the case of Brazil was in the year 2014 (to the tune of $256.847 billion); in the case of Russia it was in the year 2013 (to the tune of $130.847 billion); in the case of India it was in the year 2012 (to the tune of $179.512 billion); in the case of China it was in the year 2015 (to the tune of $421.134 billion); and in the case of South Africa it was in the year 2012 (to the tune of $50.852 billion). Our estimate shows that the capital flight from Brazil totaled $.89.272 billion; from India, the magnitude of capital flight was around $47.870, and from South Africa to the tune of $21.531 billion. The countries namely Russia and China exhibit a negative value of capital flight during the study period.

Fig. 1.

Trend of Capital flight in the BRICS.

Source: Authors' estimates based on data from World Bank

The ostensible steep rise in capital flight was evident during the 2008 global financial crisis period which involved threats of holding domestic assets, financial turmoil, insecurity, and repression. Except, for South Africa, all BRIC nations show a greater magnitude of flight of capital during the East Asian crisis of 1997–98.

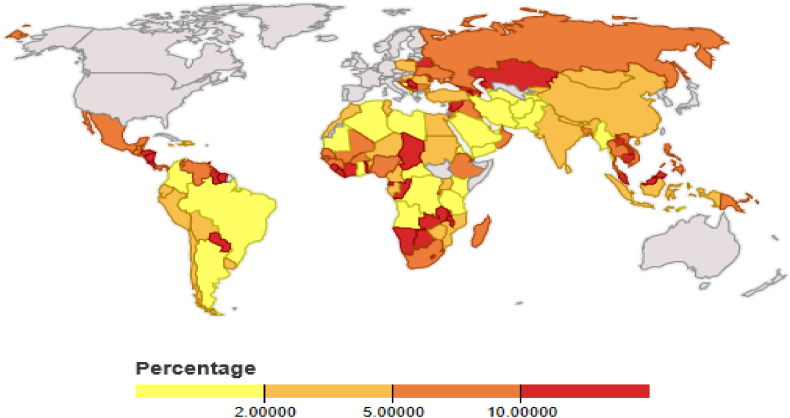

We also report the total average illicit financial flows (calculated by summing up the illicit hot money narrow outflows and trade mis invoicing outflows collected from the Global Financial Integrity, 2015 report for the period 2004–2013) by the top ten developing nations of the world (see Fig. 2). It is interesting to note that BRICS nations are among the top ten nations from where there is a huge outflow of illicit finance as compared to other developing economies of the world. In Fig. 3, we present the ratio of illicit financial flows as a proportion to GDP from all developing nations of the world reported for the period 2003–2014. Among the BRICS nations, the ratio of illicit financial flow to GDP in Russia and South Africa is represented by orange color in Fig. 3 with a value of 7.471 %, and 6.543 % respectively. The ratio of illicit financial flows as a proportion to GDP in India, and China (represented by a dark yellow color in Fig. 3) are reported to be 3.753 %, and 2.714 % respectively. The percentage of illicit financial flows from Brazil is reported to be at a moderate level with a value of 1.329 % and is represented by a light yellow color in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Illicit Financial Outflows from a list of Developing Nations.

Source: Global Financial Integrity Report, 2015

Fig. 3.

Ratios of illicit financial flows to GDP for developing countries.

Source: Global Financial Integrity Report, 2015

5. Data and methodology

5.1. Data

The present analysis is subject to the availability of the secondary data. The historical data is collected for the BRICS nations from the year 1997 through the year 2017. We considered seven important variables in our analysis namely capital flight represented as a proportion to GDP, annual GDP growth rate, change in exchange rate, unemployment rate, liquid assets to deposits and short-term funding, bank Z score, business confidence indices, and political stability indices.2 The data for the present analysis is sourced from the World Bank, IMF, and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

5.2. Model and methodology

The existing studies suggest four major methods of measuring capital flight3 i.e. [1], The World Bank (1985) residual method [2,39] Dooley's residual method ([[40], [41], [42]]) [3]; Hot money measure of Cuddington [4,43] trade mis invoicing method [44]. World Bank and Dooley's residual methods include the effect of the determinants such as foreign direct investments, current account deficits, government deficits, external debt, and change in reserves accounting to capital flight. This measure only captures changes in the stock of capital flight subject to legal measurement errors [45].

The hot money measure includes the ‘errors and omissions’ and private short-term capital figures from the balance of payments identities. This method provides an understatement of capital flight since it excludes long-term capital flows and unrecorded outflows are not captured [46]. Moreover, the argument that developing countries would have no outflow of short-term capital in the normal course of business is not convincing ([45,47]).

The Trade misinvoicing method implies comparing export-import data furnished by domestic trading partners with official domestic trade data. The divergence between official domestic exports to the world (adjusted for shipping and insurance) and the world's imports from a domestic country is defined as export misinvoicing. Similarly, the difference between official figures of domestic imports from the world and the world's exports to the domestic country (adjusted for shipping and insurance) is attributed to import misinvoicing. If official figures on domestic imports were greater than the adjusted figures for the world's exports to domestic countries, it would indicate import over-invoicing. However, the major criticism against this measure is that it would be wrong to equate misinvoicing per se with capital flight [46]. Besides, it emphasizes only the trade identities and therefore is a narrow measure of capital flight.4

We follow the [39] residual method which is a conservative yet broad measure of capital flight. Hence, we estimate capital flight as:

| CF = ΔED + NFI – CAD – ΔR (1) |

Where CF implies capital flight and ΔED denotes a net change in the stock of gross external debt. NFI refers to net foreign investment inflow which includes net foreign direct investment and net foreign portfolio investment. CAD denotes the current account deficit and ΔR is the change in the levels of official foreign reserves.

The extant literature shows that several variables compel private investors to decide to reallocate their capital from domestic to foreign assets. Firstly, we employ the One-Step System GMM approach in a dynamic panel framework. Secondly, we also use the feasible generalized least square (FGLS) regression approach in a static panel framework5 for the robustness of the dynamic regression results. The rationale of using this method is because of the notable reasons [1]. The FGLS approach is most applicable when the number of cross-sectional units (N) is less than the time series components (T). The estimates required large time series components since we are estimating variance parameters for each panel [2]. The conventional OLS approach might produce biased and inconsistent estimates in the presence of simultaneity problems. Furthermore, when the heteroscedasticity problems are existing in the data the OLS estimates are no longer efficient, although unbiased. To overcome this problem, it is advisable to use the generalized least square estimation to achieve efficient outcomes. Based on the previous studies and availability of data, we specify the following model in a dynamic panel framework:

| (2) |

| (3) |

The aforementioned Eqn. (2) represents equation in level and Eqn. (3) shows equation in first difference (difference GMM estimator) where both equations are a part of system GMM testing approach. In Eqn. (2) and Eqn. (3), CF refers to capital flight from the i country at time period t; CFi,t-1 is the lagged term of the capital flight representing capital flight trap; α is the constant term; denotes the coefficient of the auto-regression; z is the set of explanatory variables considered in the analysis; is the unobserved country specific effect; is the unobserved time specific effect; and is the random disturbance term of the model.

We report the results of the System GMM estimators [48]. show that the results of the system GMM testing procedure are expected to provide better finite sample properties, improve the precision of the model in terms of root mean squared error, and reduce the small sample bias [49] than the difference GMM testing procedure. Additionally, the difference GMM testing approach provides inefficient inferences if the sample size is small [50]. Therefore, reporting the results of the System GMM estimator is a kind of robustness of the baseline results that incorporate the FGLS regression.

The GMM testing procedure provides asymptotically efficient results having the least set of statistical assumptions. The motivation for choosing the GMM estimator is dictated based on the following reasons [1]. The number of cross-sectional units (N) should be greater than the time series components (T) to employ the GMM approach. However, there is no hard and fast rule to apply this information criterion. Many studies have also used (T > N) criteria while employing the GMM estimator ([49,[51], [52], [53]]; 55)) [2]. This testing procedure reduces potential endogeneity, cross-sectional dependence, and heteroscedasticity and produces robust standard errors [49]. [3] The GMM estimator takes into account the cross-country variations [4]. System GMM estimator results provide robustness and reduce biases that are associated with the difference GMM estimator.

6. Empirical results and analysis

In this section, we present the results of our empirical analysis. Before applying any panel technique, the statistical properties of the variables are checked to establish a dynamic relationship between the variables. The empirical analysis starts with the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix among the variables under consideration. Table 1 describes the summary and correlation statistics of the variables, i.e. CFGDP, GDPGR, ΔEXRATE, UNEMRATE, BCI, POLSTAB, LNLADSTF, LNZSCORE of BRICS nations for the period 1997 to 2017.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

| Variables | Mean | S.D | Skewness | Kurtosis | Normality Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.453 | 7.713 | −1.233 | 5.903* | 24.51 (0.000) | |

| 5.520 | 23.797 | −2.003 | 8.956* | 43.18 (0.000) | |

| 0.879 | 3.318 | 3.358 | 22.038* | 0.000 (0.000) | |

| 10.234 | 9.203 | 1.304 | 3.199* | 17.63 (0.000) | |

| 99.207 | 9.209 | −9.409 | 91.367* | 0.000 (0.000) | |

| −0.490 | 0.483 | −0.355 | 2.036 | 12.56 (0.001) | |

| 3.221 | 0.696 | −0.236 | 1.863 | 21.70 (0.000) | |

| 2.677 | 0.411 | 0.650 | 6.945* | 18.22 (0.000) |

Note: CFGDP = Capital Flight to GDP; GDPGR = Annual Gross Domestic Product growth rate; ΔEXRATE = Change in Exchange Rate; UNEMRATE= Unemployment Rate; BCI= Business Confidence Index; POLSTAB = Political Stability Index; LNLADSTF= Liquid assets to deposits and short term Funding; LNZSCORE = Bank Z SCORE. Normality test is conducted using D'Agostino et al. (1990) and Royston [1991c] as it offers asymptotic standard errors with corrections for sample size. Values in the parenthesis are p values.

Source: Author's computation

From the above Table 1, we summarize the variables based on certain statistics. The mean of all the variables is positive except POLSTAB. The standard deviation for all variables is low except GDPGR. The low values of the standard deviation in Table 1 show that the observations are less deviated as compared to the mean values. The positive skewness values of the variables namely ΔEXRATE, UNEMRATE, and LNZSCORE imply that the distribution of these variables is skewed to the right as compared to the normal distribution. The kurtosis value of the variables such as CFGDP, GDPGR, ΔEXRATE, UNEMRATE, BCI, and LNZSCORE is greater than 3. Hence, it is clear that the distribution of all these variables (i.e. greater than 3) is leptokurtic. We employ the [54,55] Normality test which offers asymptotic standard errors with corrections for sample size and is preferred over the Jarque-Bera Normality test. The statistically significant values of all the variables suggest that these variables are non-normally distributed. Furthermore, the correlation matrix is reported in Table 2. The insignificant values of the correlation coefficient indicate less possibility of multicollinearity problem6 existing among the independent variables considered in Eqn [1].

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

| Variables | LNZSCORE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||||

| −0.355 | 1 | |||||||

| 0.049 | −0.452 | 1 | ||||||

| 0.394 | −0.221 | −0.041 | 1 | |||||

| −0.108 | −0.006 | 0.012 | 0.023 | 1 | ||||

| 0.333 | −0.264 | −0.123 | 0.531 | −0.060 | 1 | |||

| −0.135 | −0.094 | 0.074 | −0.169 | −0.071 | 0.242 | 1 | ||

| 0.191 | −0.037 | −0.172 | 0.302 | −0.023 | 0.278 | −0.416 | 1 |

Note: Variables as defined in Table 1.

Source: Author's computations

We report the unit root test results in an unbalanced panel setup [56]. shows that GMM estimators might produce biased results if the data are non-stationary. Therefore, we employ the Fisher type [57] unit root test (which incorporates both the Augmented Dickey Fuller test (ADF) and Phillips Perron (PP) test) which is appropriate for the unbalanced panel data. The value of the inverse chi-squared (P) statistic is presented in Table 3 which suggests that all variables considered in the model are stationary when no time trend component is used. We use the dynamic panel regression model to analyze the determinants of capital flight from BRICS nations. The result of the FGLS approach is reported in Table 4. It is very evident from the literature that capital flight from an economy is due to economic, political, and financial uncertainties ([2,45,58]).

Table 3.

Panel unit root test statistics.

| Variables |

ADF |

PP |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No trend | Trend | No trend | Trend | |

| 22.678** | 23.373* | 22.678** | 23.373* | |

| 176.905* | 144.821* | 176.905* | 144.821* | |

| 32.627* | 17.412*** | 32.627* | 17.412*** | |

| 17.295*** | 9.121 | 17.295*** | 9.121 | |

| 35.955* | 44.171* | 35.955* | 44.171* | |

| 75.839* | 58.613* | 75.839* | 58.613* | |

| 16.189*** | 26.346* | 16.189*** | 26.346* | |

| 18.615** | 21.577** | 18.615** | 21.577** | |

Note: Variables as defined in Table 1. The values of inverse chi-squared (P) statistic are being reported in the table, which necessitates the number of panels to be finite. * and ** denotes rejection of the null hypothesis that shows all panels contain unit root and accepts alternative hypothesis that at least one panel is stationary at 1 % and 5 % level of significance respectively.

Source: Author's computation

Table 4.

Determinants of capital flight.

| One Step System GMM Approach | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A |

Panel B |

Panel C |

||||

| Variables | Coefficients | P values | Coefficients | P values | Coefficients | P values |

| 11.118 | 0.012 | 8.682 | 0.032 | 20.184 | 0.002 | |

| 0.544 | 0.000 | 0.538 | 0.000 | 0.521 | 0.000 | |

| −0.139 | 0.000 | −0.135 | 0.000 | −0.140 | 0.000 | |

| −0.644 | 0.000 | −0.644 | 0.000 | −0.649 | 0.000 | |

| 0.099 | 0.107 | 0.096 | 0.136 | 0.079 | 0.230 | |

| −0.099 | 0.023 | −0.073 | 0.066 | −0.079 | 0.044 | |

| −0.334 | 0.762 | 1.275 | 0.277 | |||

| −1.748 | 0.029 | |||||

| −1.694 | 0.148 | |||||

| Autocorrelation | ||||||

| [1] order | −1.909 | (0.056) | −1.994 | (0.046) | −2.056 | (0.039) |

| [2] order | −1.151 | (0.249) | −1.149 | (0.251) | −1.218 | (0.223) |

| Sargan Test | ||||||

| 171.446 | (0.219) | 179.881 | (0.364) | 177.244 | (0.376) | |

Note: CFGDPi,t-1 = lagged value of the Capital Flight to GDP. Rest of the variables are same as defined in Table 1.

Source: Author's computations.

To understand the impact of the macroeconomic uncertainties, we incorporate the variables that best represent the state of the macroeconomy (see Panel A, Table 4, Table 5). Most of the variables that affect the movement of normal capital flows are also applicable to the episodes of capital flight with equal force [59]). Political instabilities and uncertainties affect the institution's economic policies and long-term decisions on economic growth. Keeping this in view, we include the political stability indicator as a crucial determinant of capital flight in our analysis (Panel B, Table 4, Table 5) [59]. explain about two types of political instabilities i.e. regime instability and political violence. Regime instabilities can be explained as a change in the government either constitutionally or unconstitutionally. Various forms of changes in the regime type (i.e. democratic, autocratic, etc.) may have different impacts on future policies and their outcomes. Different political parties hold different political ideologies. It is evident that when there is a regime shift, different interest groups forming the government join the office, which increases the uncertainty about future fiscal policies. On the other hand, political violence refers to any situation that causes political unrest paving the way for crime, increase in terrorism, assassinations, riots, strikes, etc. Such type of political instabilities will lead to a political business cycle. Previous literature also discusses the impact of political instability on capital flight ([60,61]; and [62]).

Table 5.

Determinants of capital flight.

| Panel Feasible Generalized Least Square Regression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A |

Panel B |

Panel C |

||||

| Variables | Coefficients | P values | Coefficients | P values | Coefficients | P values |

| 7.291 | 0.238 | 7.881 | 0.182 | 16.544 | 0.119 | |

| −0.092 | 0.005 | −0.081 | 0.012 | −0.084 | 0.012 | |

| −0.246 | 0.376 | −0.200 | 0.481 | −0.182 | 0.492 | |

| 0.253 | 0.000 | 0.207 | 0.002 | 0.167 | 0.044 | |

| −0.067 | 0.279 | −0.059 | 0.320 | −0.072 | 0.284 | |

| 2.170 | 0.193 | 2.454 | 0.218 | |||

| −1.311 | 0.252 | |||||

| −0.894 | 0.597 | |||||

| Statistics | ||||||

| 36.36 | 0.000 | 38.24 | 0.000 | 35.53 | 0.000 | |

Source: Author's computation

In our analysis, we have included certain indicators which represent the financial stability of an economy. Financial stability is explained as the overall strength of the financial system and institutions resilient to economic shocks and smoothly fulfill all the basic functions such as risk management, intermediation of financial funds, and the arrangement of payments. Previous literature holds the weakness of the financial systems as the major cause of the crises of the past. In alignment with this view, the third-generation crisis models identify the domestic banking system among the main factors of the crises of the 1990s [[63], [64], [65]]. argue that crises are associated with the liquidity problem. Countries associated with weak financial structures face a liquidity crunch. Furthermore, sudden changes in the market sentiments expose the balance sheet of these firms. Such liquidity problems cause substantial capital withdrawal in the form of capital flight aggravating the crisis [66]. proposes a portfolio balance model and shows that capital flight may occur because of a liquidity crunch in an open economy even if there is no shift in the underlying fundamentals. Motivated by these studies, we consider financial stability indicators as important factors contributing substantially to capital flight (see Panel C, Table 4, Table 5). The results of the One-step System GMM approach and FGLS are reported in Table 4, Table 5 respectively.

We present the results of the One-step System GMM in Table 4. We find positive and statistically significant values of capital flight trap on the current values of the capital flight. Our results are in congruence with the recent literature ([32,67]). Therefore, it is evidenced that the lagged capital flight positively influences the present capital flight from these nations and is self-reinforcing and creating a vicious cycle. The sign of the coefficient of the variable CFGDPi,t-1 does not change when the POLSTAB variable is included in Panel B and financial stability indicators are included in Panel C.

The GDPGR denotes growth rates of gross domestic product (GDP) in current prices which measures the rate of growth of domestic production taking place in an economy. The growth rate of GDP is one of the crucial factors discussed in capital flight studies. Nevertheless, the sign of the coefficient of the GDP growth rates with the capital flight is controversial and unclear [19]. Previous studies find a negative relationship between economic growth inducing capital flight ([68,69]). In contrast, an increase in GDP raises incomes and profits resulting the investors siphoning their funds offshore [70]. The reason for the positive relationship between the GDP growth rates and capital flight is attributed to capital account liberalization and portfolio diversification. We find a negative relationship between the real GDP growth rates with the capital flight. Our finding is in accord with the past literature ([68,69]). The sign of the coefficient of the variable GDPGR remains unchanged when the POLSTAB and Financial stability variables were included in the Panels B and C respectively.

ΔEXRATE refers to a change in domestic currency concerning one US dollar expressed in nominal terms. The capital flight literature suggests a negative relationship between exchange rate and capital flight. This is because a possible impending domestic currency depreciation erodes the value of domestic assets prompting the investors to switch to foreign assets ([43,71,72]). We find a negative and statistically significant coefficient of the variable ΔEXRATE. Depreciation of the domestic currency erodes the value of domestic assets faster as compared to the assets held abroad. Therefore, resident investors would prefer to channel their funds to countries with stable exchange rates to protect their assets against a loss. Our results are in contrast with the previous findings of [19], who find that REER is an insignificant factor influencing capital flight for Eastern European nations. By employing ARDL approach [28], also probed the factors affecting the capital flight from Bangladesh for the period 1973 to 1999. The authors also find an insignificant impact of the real exchange rate on capital flight. The results of Panel A remain similar when POLSTAB variable is included in the Panel B and financial stability variables are included in Panel C.

The unemployment rate has attracted much attention as a factor determining the capital outflows from many economies [73]. introduced relative wage rates into a neoclassical trade model and found that a rise in unemployment is due to the exodus movement of capital. The increase in unemployment is due to the capital outflow which reduces the supply of capital goods. By using panel data over the period 2000 through 2004 for a sample of 52 IMF member countries [74], show that for the full sample period, outward foreign direct investment flows are negatively associated with the unemployment rate and outward portfolio investment flows are positively correlated with the rate of unemployment [75]. confirms a positive relationship between FDI outflows and the unemployment rate. The author also concludes that capital outflows deteriorate the level of employment in the domestic labor market [76]. using the time series data from the period 1983 through 2014 find a positive relationship between unemployed labor and capital flight in Pakistan. In alignment with the previous empirical studies, we find a positive but statistically insignificant parameter of the variable UNEMRATE on capital flight. An increase in the unemployment rate in BRICS nations implies social unrest and exhibits policy paralysis among these nations. Moreover, a rise in unemployed labor might also lead to a reduction in personal income that persuades labor and capital migration to the country of emigration. Our results are consistent throughout all the panels (i.e. Panel A, B, and C) and faithful to the previous literature.

The business confidence index (BCI) is an indicator that evaluates the viewpoint of entrepreneurs about the prospects of their enterprises and opinions related to the current performance of the economy. The higher value of the BCI index implies high confidence, which helps to strengthen the morale of economic agents in the domestic economy. Therefore, based on the theoretical expectation we find a negative and statistically significant value of BCI on capital flight (See Panels A, B, and C). It is clear from the empirical exercise that the economic viewpoint of the entrepreneurs also affects their investment decisions and returns.

We use POLSTAB in our analysis to discern the impact of political stability on capital flight. The political stability index is a governance indicator that captures the perceptions based on the probability of politically motivated violence and/or instabilities because of terrorism activities, social upheavals, riots, political unrest, religious disturbances, armed conflicts, destabilization of the government, etc. Political instability results in anxiety, fear, and panic about an uncertain future and business, which push domestic investors to put their capital offshore to some safer havens ([28,[77], [78], [79]]). In congruence with this theoretical explanation, we derive a statistically insignificant coefficient of the variable POLSTAB on capital flight. We find similar results in all the two specifications (see Panel B and Panel C).

The role of financial development contributing to resident capital outflow from a nation has not received due attention in many capital flight studies. For instance Ref. [8], opines that the development of the financial sector might cause a decline in capital flight only when there are a lot of opportunities for investors to diversify their portfolio. On the other hand, liberalization of financial markets and deregulation of capital flows would motivate capital flight as long as risk-adjusted returns are higher overseas. There are several ways of measuring the financial development of an economy [80]. measure the financial development of an economy using demand deposits. The authors find a negative and statistically significant effect of demand deposits on capital flight. Similarly [81], use M2 as a proportion of GDP as a proxy of financial depth but did not find any relationship between financial depth and capital flight. Following the definition of [2], we use financial instability variables also as factors responsible for resident capital outflows. The financial sector of an economy is expected to be stable when it erodes persisting financial imbalances occurring from unforeseen events.

Financial instabilities in any economy can lead to crises, stock market crashes, hyperinflation, bank runs, and hyperinflation [82]. also holds capital flight to be a source of financial instability, since worried depositors tend to withdraw their capital causing the banking sector to fail. We use two important financial stability indicators in our analysis. The variable LNLADSTF is represented as the ratio of easily convertible liquid assets to deposits plus short-term funding. Liquid assets comprise cash and the outstanding amount payable by the banks, advances and loans to the banks, cash collaterals, reverse repos, and trading securities. Deposits take into account total customer deposits in the form of demand, fixed and term deposits, and short-term borrowing including money market instruments such as certificates of deposits and miscellaneous deposits). Since this indicator explains the liquidity aspect of the banking sector, we expect that greater access to convertible liquid assets would tend to reduce capital flight. This will help preserve financial stability and enhance investors’ confidence in the banking sector. We find a negative and statistically significant value of the coefficient LNLADSTF (see Panel C).

We include LNZSCORE variable as another proxy of financial stability which measures banks' solvency risk. The z-score is calculated as the ratio of equity capital plus return as a percentage of assets to the standard deviation of return on assets. A rise in the value of z-score indicates a lower probability of insolvency. Past studies used the z-score as an important proxy to measure bank stability (see Refs. [[83], [84], [85]]). We also expect a negative relationship between Bank Z score and capital flight. Going by the theoretical linkage, we find a negative but statistically insignificant coefficient of the variable LNZSCORE. In other words, an increase in the bank solvency level reduces the capital moving abroad and boosts domestic investors’ confidence in the financial banking system (see Panel C).

We performed the model diagnostic check for the baseline regression and the robustness check results. The AR tests help to detect the serial correlation in the first order and second order. Although, we find the AR [1] test statistic to be significant in all the cases indicating serial correlation in the first difference of the disturbance term, however, AR [2] detects no autocorrelation in level. Therefore, we confirm that all the models of our analysis are free from the problem of serial correlation. The Sargan test helps identify about the correct specification of the instruments considered in the model. We find Sargan test statistics to be insignificant in all the models which suggests that the instruments are exogenous and valid. Therefore, all our models pass the post-model diagnostic check criteria.

We also carried out a robustness check of the dynamic panel regression by employing the FGLS regression in a static panel framework. We find only two variables namely UNEMRATE and GDPGR as significant variables influencing the capital flight variable. We find that capital flight from the BRICS nations is primarily because of the high level of unemployment rate in these economies while an increase in domestic activity in these economies retains capital from moving abroad.

7. Conclusion and policy implications

The persistence of capital flight has raised the concerns of the policy formulators and its control has become the utmost priority, especially for a group of capital-scarce nations such as BRICS. The post-financial liberalization marked the growth of foreign investment inflows but exposed the economy to exchange rate shocks and capital flight. In response to the current findings, this study merits the requirement of effective policies to arrest capital flight from BRICS nations. BRICS countries need to maintain their GDP growth rates because it influences domestic investors and provides them with better platforms for investment. Additionally, relaxation in investment guidelines will boost the business confidence of the investors and employment generation will restore social stability. Our results also suggest that sound financial and banking sectors in the BRICS nations can retain the residents' investors' funds to move out and simultaneously allure further foreign capital flows. Interestingly, we did not find any significant impact of the political stability index on capital flight. The present findings regarding determinants indicate that the policies must focus on growth-oriented activities, maintaining macroeconomic stability, and boosting investors' confidence by optimizing interest rates on lending. The economic development objectives of the several governments of this trade union remain unrealizable without the self-reliance of residents’ capital.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the World Development Indicators (2019).

Links: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#

Funding

There is no funding available for this study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ashis Kumar Pradhan: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Padmaja Bhujabal: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft. Narayan Sethi: Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Capital outflow is an outcome of residents aiming for portfolio diversification strategies or else domestic commercial banks who intend to acquire or extend foreign deposit holdings [47]).

Private credit as a percentage of GDP, broad money supply, foreign aid inflow, and corporate tax are also important variables that might influence capital flight but we cannot include these variables in our model because of the following reasons. We have considered the financial instability indicators and, therefore dropped financial deepness indicators such as Private credit as a percentage of GDP, and broad money supply. Further, the non-availability of data on other determinants of capital flight for the study period restricts the inclusion of more number of independent variables in the model as it will reduce the degrees of freedom.

For a detailed discussion on estimation methods of capital flight, see [6].

For a critical analysis of trade misinvoicing method, see [70].

We also estimated the determinants of capital flight from the BRICS nations using the Fixed effects and Random effects models. However, the post-diagnostic results confirmed the presence of serial correlation and cross-sectional dependence in these models. The results are with the authors and will be provided on request.

We have also estimated the Variance inflation factor to check the degree of multicollinearity. The mean value of the VIF is found to be 1.53 which also confirms less possibility of perfect linear relationship among the explanatory variables.

Contributor Information

Ashis Kumar Pradhan, Email: ashiskumarprdhn@gmail.com.

Padmaja Bhujabal, Email: padmaja.1806@gmail.com.

Narayan Sethi, Email: nsethinarayan@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Pradhan A.K., Hiremath G.S. The capital flight from India: a case of missing woods for trees? Singapore Econ. Rev. 2020;65(2):365–383. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kindleberger C.P. Capital Flight and Third World Debt, DR Lessard and J Williamson. Institute for International Economics; Washington D.C.: 1987. Capital flight-A historical perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein G.A., editor. Capital Flight and Capital Controls in Developing Countries. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter I. Capital Flight and Third World Debt. 1987. The mechanisms of capital flight; pp. 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deppler M., Williamson M. Capital flight: concepts, measurement, and issues. Staff studies for the world economic outlook. 1987;39:58. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ajayi M.S.I. International Monetary Fund; 1997. An Analysis of External Debt and Capital Flight in the Severely Indebted Low Income Countries in Sub-saharan Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper W.H., Hardt J.P., amp; Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division . Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress; 2000, March. Russian Capital Flight, Economic Reforms, and US Interests: an Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ndikumana L., Boyce J.K. Public debts and private assets: explaining capital flight from Sub-Saharan African countries. World Dev. 2003;31(1):107–130. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Q.V., Rishi M. Corruption and capital flight: an empirical assessment. Int. Econ. J. 2006;20(4):523–540. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forgha N.G. Capital flight, measurability and economic growth in Cameroon: an econometric investigation. International Review of Business Research Papers. 2008;4(2):74–90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wujung V.A., Mbella M.E. Capital flight and economic development: the experience of Cameroon. Economics. 2016;5(5):64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onodugo V.A., Kalu I.E., Anowor O.F., Ukweni N.O. Is capital flight healthy for Nigerian economic growth? An econometric investigation. J. Empir. Econ. 2014;3(1):10–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosarev A., Grigoryev L. Bureau of Economic Analysis; 2000. Capital Flight: Scale and Nature. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng H.F., Gutierrez M., Mahajan A., Shachmurove Y., Shahrokhi M. A future global economy to be built by BRICs. Global Finance J. 2007;18(2):143–156. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Global Financial Integrity, Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2004-2013, 2015. https://gfintegrity.org/report/illicit-financial-flows-from-developing-countries-2004-2013/. Kar, D., & Spanjers, J. (2015). Illicit financial flows from developing countries: 2004-2013. Global Financial Integrity, 1-10.

- 16.O’neill J., Building better global economic BRICs (2001) Available at: https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/archive/archive-pdfs/build-better-brics.pdf.No.

- 17.World Bank . World Bank; Washington D.C: 1985. World Development Report. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyce J.K., Ndikumana L. Political Economy Research Institute University of Massachusetts; 2012. Rich Presidents of Poor Nations: Capital Flight from Resource-Rich Countries in Africa.http://concernedafricascholars.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/caploss01-ndiku-14th.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brada J.C., Kutan A.M., Vuksic G. Capital flight in the presence of domestic borrowing: evidence from Eastern European economies. World Dev. 2013;51:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yalta A.Y. Capital flight: Conceptual and methodological issues. Hacettepe Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi. 2009;27(1):73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dachraoui H., Sebri M., Dwedar M.M. Natural resources and illicit financial flows from BRICS countries. Biophysical Economics and Sustainability. 2021;6:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basher S., Mamun A., Bal H., Hoque N., Uddin M. Does capital flight tone down economic growth? Evidence from emerging Asia. Journal of Financial Economic Policy. 2023;15(4/5):444–484. [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Jongh J., Mncayi P. An econometric analysis on the impact of business confidence and investment on economic growth in post-apartheid South Africa. Int. J. Econ. Finance Stud. 2018;10(1):115–133. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau C.K., Gozgor G., Mahalik M.K., Patel G., Li J. Introducing a new measure of energy transition: Green quality of energy mix and its impact on CO2 emissions. Energy Econ. 2023;122 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beja E., Jr. Ateneo de Manila University; Quezon City: 2007. Capital Flight and Economic Performance: Growth Projections for the Philippines. MPRA Paper No. 4885. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ljungwall C., Wang Z. Why is capital flowing out of China? China Econ. Rev. 2008;19(3):359–372. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kipyegon L. Doctoral dissertation, Kenyatta University; 2004. Determinants of Capital Flight from kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alam I., Quazi R. Determinants of capital flight: an econometric case study of Bangladesh. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2003;17(1):85–103. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrigan J., Mavrotas G., Yusop Z. On the determinants of capital flight: a new approach. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2002;7(2):203–241. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheung Y.W., Qian X. Capital flight: China's experience. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2010;14(2):227–247. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anetor F.O. Macroeconomic determinants of capital flight: evidence from the Sub-Saharan African countries. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. 2019;8(1):40–57. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salandy M., Henry L. Determinants of capital flight from beautiful places: the case of small open economy of Trinidad and Tobago. J. Develop. Area. 2018;52(4):85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uddin M.J., Yousuf M., Islam R. Capital flight affecting determinants in Bangladesh: an econometric estimation. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management. 2017;8(1):233–248. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forson R., Obeng K.C., Brafu-Insaidoo W. Determinants of capital flight in Ghana. Journal of Business and Enterprise Development. 2017;7:151–180. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auzairy N.A., Fun C.S.F.S., Ching T.L., Li S.B., Fung C.S.F.S. Dynamic relationships of capital flight and macroeconomic fundamentals in Malaysia. Geografia: Malaysian Journal of Society and Space. 2017;12(2) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-basheer A.B., Al-Fawwaz T.M., Alawneh A.M. Economic determinants of capital flight in Jordan: an empirical study. Eur. Sci. J. 2016;12(4):322–334. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liew S.L., Mansor S.A., Puah C.H. Macroeconomic determinants of capital flight: an empirical study in Malaysia. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016;10(13):2526–2534. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Onodugo V.A., Kalu I.E., Anowor O.F., Ukweni N.O. Is capital flight healthy for Nigerian economic growth? An econometric investigation. J. Empir. Econ. 2014;3(1):10–24. [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Bank . World Bank; Washington D.C: 1985. World Development Report. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dooley M.P. Country-specific risk premiums, capital flight and net investment income payments in selected developing countries. International Monetary Fund Departmental Memorandum. 1986;17 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dooley M.P. In: Capital Flight and the Third World Debt. Lassard Donald R., Williamson John., editors. Institute for International Economics; Washington, DC: 1987. Comment on the definition and magnitude of recent capital flight, by Cumby, Robert and Richard Levich. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dooley M.P. Capital flight: a response to differences in financial risks. Int. Monetary Fund Staff Pap. 1988;35:422–436. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuddington J.T. Princeton University Press; New Jersey: 1986. Capital Flight: Estimates, Issues, and Explanations. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyrie M.E., Nelson J.A., Pak S.J. Capital movement through trade misinvoicing: the case of Africa. J. Financ. Crime. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider B., Measuring Capital Flight: Estimates and Interpretations, Overseas Development Institute, London, 2003. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.876.2035&rep=rep1&type=pdf. No volumme Number for this.

- 46.Eggerstedt H., Hall R.B., Wijnbergen S.V. Measuring capital flight: a case study of Mexico. World Dev. 1995;23:211–232. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hermes N., Lensink R. The magnitude and determinants of capital flight: the case for six sub-Saharan African countries. Economist. 1992;140:515–530. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blundell R., Bond S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 1998;87(1):115–143. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahman M.M., Rana R.H., Barua S. The drivers of economic growth in South Asia: evidence from a dynamic system GMM approach. Journal of Economic Studies. 2019;46(3):564–577. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levine R., Loayza N., Beck T. Financial intermediation and growth: causality and causes. J. Monetary Econ. 2000;46(1):31–77. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akram N. Empirical examination of debt and growth nexus in South Asian countries. Asia Pac. Dev. J. 2014;20(2):29–52. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chakravarty D., Mandal S.K. Estimating the relationship between economic growth and environmental quality for the BRICS economies-a dynamic panel data approach. J. Develop. Area. 2016;50(5):119–130. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahapatra S.S., Sinha M., Chaudhury A.R., Dutta A., Sengupta P.P. Handbook of Research on Military Expenditure on Economic and Political Resources. IGI Global; 2018. Defense expenditure and economic performance in SAARC countries; pp. 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- 54.D'Agostino R.B., Belanger A.J., D'Agostino R.B., Jr. A suggestion for using powerful and informative tests of normality. Am. Statistician. 1990;44:316–321. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Royston P. sg3.5: comment on sg3.4 and an improved D'Agostino test. Stata Technical Bulletin 3: 23–24. Reprinted in Stata Technical Bulletin Reprints. 1991;1:110–112. (College Station, TX: Stata Press) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bond S.R. Dynamic panel data models: a guide to micro data methods and practice. Portuguese Econ. J. 2002;1(2):141–162. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi I. Unit root tests for panel data. J. Int. Money Finance. 2001;20(2):249–272. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hasnul A.G., Masih M. Role of instability in affecting capital flight magnitude: An ARDL bounds testing approach. 2016 https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/72086/1/MPRA_paper_72086.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 59.Le Q.V., Zak P.J. Political risk and capital flight. J. Int. Money Finance. 2006;25(2):308–329. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alesina A., Tabellini G. External debt, capital flight and political risk. J. Int. Econ. 1989;27(3–4):199–220. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tornell A., Velasco A. The tragedy of the commons and economic growth: why does capital flow from poor to rich countries? J. Polit. Econ. 1992;100(6):1208–1231. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhattacharya R. Capital flight under uncertainty about domestic taxation and trade liberalization. J. Dev. Econ. 1999;59(2):365–387. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chang R., Velasco A. Cambridge, Mass., National Bureau of Economic Research; 1998. Financial Crises in Emerging Markets: A Canonical Model. NBER Working Paper No. 6606. June; also published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chang R., Velasco A. Cambridge, Mass., National Bureau of Economic Research; 1998. The Asian Liquidity Crisis. NBER Working Paper No. 6796. (November) [Google Scholar]

- 65.Radelet S., Sachs J. NBER Working Paper Series No. 6680; 1998. The Onset of the East Asian Financial Crisis. (August) [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guha S. Financial integration, capital flight and the IMF. Indian Econ. Rev. 2005:37–64. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Asongu S.A., Nting R.T., Osabuohien E.S. One bad turn deserves another: how terrorism sustains the addiction to capital flight in Africa. J. Ind. Compet. Trade. 2019;19(3):501–535. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pastor M Jr. Capital flight from Latin America. World Dev. 1990;18:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nyoni T.S. In: External Debt and Capital Flight in SubSaharan Africa. Ajayi S.I., Khan M.S., editors. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund; 2000. Capital flight from tanzani. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cerra V., Rishi M., Saxena S.C. Robbing the riches: capital flight, institutions, and debt. J. Dev. Stud. 2008;44:1190–1213. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dornbusch R. New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1986. Inflation, Exchange Rates and Stabilization. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Conesa E.R. Inter-American Development Bank; Washington D.C: 1987. The Causes of Capital Flight from Latin America. Mimeo. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eckel C. Labor market adjustments to globalization: unemployment versus relative wages. N. Am. J. Econ. Finance. 2003;14(2):173–188. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lin M.Y., Wang J.S. Capital outflow and unemployment: evidence from panel data. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2008;15(14):1135–1139. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Polat B. Capital outflows and unemployment: a panel analysis of OECD countries. Applied Economics and Finance. 2016;3(4):73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tabassum S., Quddoos A., Yaseen M.R., Sardar A. The relationship between capital flight, labor migration and economic growth. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2017;6(4):594. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lessard D.R., Williamson J. Institute for International Economics; Washington D.C.: 1987. The Problem and Policy Responses. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fatehi K., Gupta M. Political instability and capital flight: an application of event study methodology. Int. Exec. 1992;34(5):441–461. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lensink R., Hermes N., Murinde V. Capital flight and political risk. J. Int. Money Finance. 2000;19(1):73–92. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lensink R N Hermes, Murinde V. The effect offinancial liberalization on capital flight in African economies. World Dev. 1998;26:1349–1368. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Collier P., Hoeffler A., Pattillo C. Flight capital as a portfolio choice. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2001;15:55–79. [Google Scholar]

- 82.McLeod D. Capital Flight. The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. 2002 https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc1/CapitalFlight.html [Google Scholar]

- 83.Demirgüç-Kunt A., Enrica Detragiache E., Tressel T. Banking on the principles: compliance with basel core principles and Bank soundness. J. Financ. Intermediation. 2008;17(4):511–542. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Laeven L., Levine R. Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. J. Financ. Econ. 2009;93(2):259–275. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Čihák M., Hesse H. Islamic banks and financial stability: an empirical analysis. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2010;38(2–3):95–113. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the World Development Indicators (2019).

Links: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#