Abstract

Immunization with Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate polysaccharide vaccines has dramatically reduced Hib disease worldwide. As in other populations, nasopharyngeal carriage of Hib declined markedly in Aboriginal infants following vaccination, although carriage has not been entirely eliminated. In this study, we describe the genetic characteristics and the carriage dynamics of longitudinal isolates of Hib, characterized by using several typing methods. In addition, carriage rates of nonencapsulated H. influenzae (NCHi) are high, and concurrent colonization with Hib and NCHi is common; we also observed NCHi isolates which were genetically similar to Hib. There is a continuing need to promote Hib immunization and monitor H. influenzae carriage in populations in which the organism is highly endemic, not least because of the possibility of genetic exchange between Hib and NCHi strains in such populations.

Prior to the implementation of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccination, Hib was a major cause of invasive disease in the Northern Territory of Australia. Incidence rates of invasive H. influenzae disease in children under 5 years of age from mid-1985 to mid-1988 were 529/100,000 in the Aboriginal population and 92/100,000 in the non-Aboriginal population, and 87.5% of these cases were caused by Hib (10). In a longitudinal study of otitis media in Aboriginal infants living in a remote community (1992 to 1994), first nasopharyngeal acquisition of respiratory bacteria (H. influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis) was predictive of early onset of otitis media (20). Of H. influenzae strains carried in the nasopharynx of Aboriginal infants, nonencapsulated strains predominated; the ratio of nonencapsulated H. influenzae (NCHi) to Hib-positive swabs was approximately 6.6 to 1. Prior to the introduction of the Hib conjugate capsular polysaccharide vaccine to this community in mid-1993, the cumulative incidence of nasopharyngeal carriage of Hib in the infants under study was at least 42.8% by age 6 months (12 of 28 infants, with up to eight swabs collected from each infant) (19). These rates fell during the first 6 months of vaccine use and reached zero in 1994 (none of 88 swabs collected from 15 infants to the age of 6 months), with no change in carriage of NCHi and non-type b encapsulated strains. Subsequently Hib carriage rates in infants in the same population have risen; this is of potential concern (21).

The polysaccharide capsule of H. influenzae is synthesized by enzymes encoded at the capsulation locus (cap). cap is approximately 17 to 18 kb in size and is organized into three functionally distinct regions (14) as in all capsulated H. influenzae serotypes (17). Approximately 98% of all type b strains actually contain two directly repeated copies of the 17- to 18-kb segment (13). In such strains, cap lies between copies of an insertion sequence-like element, IS1016, allowing regulation of the number of copies of cap and hence the level of capsule production (14) after homologous recombination. Increased capsule production may provide a selective advantage in certain situations (15). Alternatively, if there is selection against capsule, there would be an advantage for strains in which multiple copies of the 17- to 18-kb segment at the cap locus have been reduced to a single copy. The single-copy locus is also subject to loss (32).

Encapsulated H. influenzae strains have been classified by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis into two highly divergent phylogenetic divisions, designated I and II (25). Most invasive strains cluster in division I (strains of serotypes a through e), while less virulent strains of serotypes a, b, and f cluster in division II. The increased virulence of division I Hib strains worldwide has been attributed to the deletion of a specific sequence (IS-bexA) from the tandemly duplicated capsule locus (Fig. 1) (16). Loss of this region inhibits recombination and is believed to maintain the tandem configuration of cap with high levels of capsule production (3).

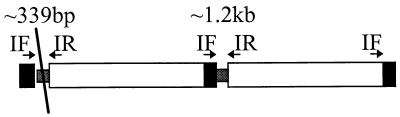

FIG. 1.

Example of the IS-bexA deletion in a phylogenetic division I Hib strain with a duplication at cap. The diagonal line indicates the location of the IS-bexA deletion. PCR amplification using primers denoted IF and IR resulted in a strong product of approximately 339 bp which relates to the truncated region and a lighter product (PCR is preferential to smaller products) of 1.2 kb relating to the complete form of the IS1016 bridge region.

Nevertheless, nonencapsulated Hib mutants arise at frequencies of 0.1 to 0.3% (12) and have been reported in several studies (4, 6, 11, 22, 32). Indeed, NCHi isolates are more adherent to buccal mucosa than capsulated forms (18), suggesting that capsule loss is a means of maintaining mucosal colonization (12). Immune pressure following Hib conjugate vaccination or past infection would also select against capsulated forms (4), raising the possibility that the widespread use of the Hib conjugate vaccine could lead to an increase in nonencapsulated mutants. Moreover, if vaccination levels fall in the community, it is also possible that nonencapsulated Hib variants can revert to the capsular form and cause new outbreaks of invasive Hib disease. Hence, it is important to characterize H. influenzae strains in populations where the organism is endemic to determine the relationship, if any, between NCHi and Hib.

H. influenzae uses further means for antigenic variation to promote survival. Most bactericidal and opsonizing antibodies targeted against membrane proteins of H. influenzae are strain specific (34). Hence, variation in outer membrane antigens is an effective means to escape antibody-dependent defense mechanisms. The genetic diversity of outer membrane proteins of NCHi is much greater than that of Hib (23, 24). This may reflect the dominant role of capsular polysaccharide in Hib as an antigenic determinant of strain structure, or it may be due to lateral genetic transfers in NCHi, with more of a barrier to such transfers in Hib due to encapsulation. Indeed, one hypothesis to account for the clonality of Hib, supported by experimental data (33), is that the capsule acts as a barrier to exogenous DNA (24). Nevertheless, acapsular mutants of Hib could use mechanisms similar to those used by NCHi to avert host immune pressures against newly exposed surface antigens.

The P2 gene of H. influenzae encodes the major outer membrane protein P2, with typical transmembrane domains and extracellular loops; this porin is an important target of the host immune response (9). Hib strains have highly conserved P2 sequences (23), unlike NCHi strains (2). A study of four P2 sequences from Hib (23) demonstrated that two strains were identical in P2 type to the MinnA strain, a frequent and virulent Hib strain in the United States, and that another strain differed by only one nucleotide in loops 4 to 6 of the P2 porin. The H. influenzae Rd strain has 94% amino acid identity to MinnA through loops 4 to 6 (H. influenzae Rd accession no. 1573092).

The coexistence of Hib and NCHi and high endemicity in this population (20) warranted a detailed molecular characterization of local isolates. PCR ribotyping, highly discriminatory for NCHi, revealed a particular ribotype (PRT 1) that is common among both NCHi and Hib isolates. Further analysis showed that NCHi-PRT 1 isolates are diverse whereas Hib-PRT 1 isolates seem clonal. The evolutionary relationships between encapsulated and nonencapsulated forms of PRT 1 isolates, and vaccine implications, are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Community and subjects.

The longitudinal study of otitis media in Aboriginal infants undertaken over the 1992-to-1994 period has been reported previously (20). Briefly, with ethical approval, 41 Aboriginal infants at a remote island community, representing 85% of the appropriate age cohort, were monitored from birth to examine the relationship between bacterial colonization of the nasopharynx and the onset of otitis media. Nasopharyngeal and ear discharge swabs were regularly collected from the infants.

The Hib conjugate polysaccharide vaccine, PRP-OMP (Pedvax HIB; Merck Sharp & Dohme), was introduced to the community in mid-1993. It was administered to infants at 2, 4, and 6 months; older infants and children under 5 years of age were included in a catch-up program.

Isolates.

Microbiological methods were as described previously (20). Briefly, nasopharyngeal swabs were smeared for Gram staining and frozen in 1.0 ml of transport broth. Thawed broth was mixed, and 10-μl aliquots were cultured on 7% chocolate agar and chocolate agar plus bacitracin, vancomycin, and clindamycin. From most swabs there was a heavy growth of H. influenzae, and four colonies were sampled from each plate, taking care to select any colonies that were morphologically distinct. Isolates of H. influenzae were identified by their requirement for X and V factors. Hib organisms were recognized by their agglutination with antisera against the type b capsular antigen, while NCHi organisms were recognized by their lack of agglutination reaction against the capsular antigens, a to f (Phadebact; KaroBio Diagnostics AB, Huddinge, Sweden). NCHi and Hib isolates were collected prior to and during the Hib vaccination period (1992 to 1994 and in 1996).

Amoxicillin MIC.

The MIC of amoxicillin against each isolate was determined by Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). The procedure was as recommended by the manufacturer and the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS), with one exception. Chocolate agar (Oxoid) was used to test the NCCLS-recommended H. influenzae reference strain ATCC 49247 and was used in place of the recommended Haemophilus test medium. The reference strain, ATCC 49247, which has an acceptable ampicillin MIC range of 2 to 8 μg/ml, consistently gave results in this range when the amoxicillin MIC was determined by using chocolate agar. The ampicillin equivalent MIC breakpoints to zone diameter interpretive standards for H. influenzae species are ≥4 μg/ml for resistant and ≤1 μg/ml for sensitive (26).

DNA preparation.

Total chromosomal DNA was initially extracted from single colonies of H. influenzae as described previously (29) but more recently by lysis of bacteria embedded in agarose at the bottom of microtiter wells followed by extraction with proteinase K (8).

Molecular characterization of the isolates. (i) Long PCR ribotyping.

The technique has been described previously (30). Briefly, approximately 100 ng of DNA was amplified in a 20-μl reaction mixture consisting of PC2 buffer (1), 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 4 pmol each of 16SG primer and 5S primer, and 0.12 μl of Taq-Pfu (15 U of Taq polymerase and 2.5 U of Pfu DNA polymerase in 16 μl). Each mixture was overlaid with 50 μl of liquid paraffin and cycled 25 times at 94°C for 10 s and 68°C for 8 min. To the resulting PCR product, 1.5 U of HaeIII was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Restriction fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer (4 mM Tris acetate, 0.2 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide/ml and photographed by using Polaroid 667 film and a 300-nm transilluminator. The resulting patterns were compared visually. PCR ribotyping using the enzyme ApoI (4 U per reaction mixture, incubated at 37°C for 14 h) was also performed.

(ii) P2 typing.

The region of the P2 gene corresponding to loops 4 to 6 of the P2 protein was amplified in a reaction mix (final volume of 25 μl) containing approximately 100 ng of dNTP template DNA, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 25 pmol of P2L4 and P2L6 primers (31), 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 U of Taq polymerase in a reaction buffer (Bresatec). After 30 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s, PCR products were purified from 0.8% agarose gels by using Bandpure (Progen) as instructed by the manufacturer. Cycle sequencing was performed in both directions with radioactively labeled primers P2L4 and P2L6, using an AmpliCycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer) as instructed by the manufacturer. Each sequencing reaction was cycled 30 times at 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s. The DNA was separated on a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel as described by Sambrook et al. (27).

(iii) PCR fingerprinting.

Isolates were PCR fingerprinted by using primers directed to enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) sequences as described by van Belkum et al. (36). The PCR mix was as described for P2 typing except that primers ERIC 1R (ATGTAAGCTCCTGGGGATTCAC) (35) and ERIC 2 (AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG) (35) were used. Samples were cycled 35 times at 94°C for 1 min, 25°C for 1 min, and 74°C for 4 min, followed by a final 10-min incubation at 74°C.

(iv) Confirmation of serotype and detection of capsule genes by PCR.

All NCHi and Hib isolates were subjected to PCR as described for P2 typing, using primers directed to the bexA region (H1 and H2) and the type b-specific region (b1 and b2) (5). The reaction mix, which was as described for P2 typing except for the primers, was cycled 25 times at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final 10-min incubation at 72°C. A 343-bp product (37) with primers H1 and H2 confirmed capsulation, and generation of a 480-bp product with primers b1 and b2 indicated a type b capsule (5). A positive reaction with primers b1 and b2 and a negative reaction with primers H1 and H2 would be expected for a type b nonencapsulated mutant.

(v) Detection of the IS-bexA deletion.

Isolates which had the IS-bexA deletion generated a 339-bp product by PCR across the IS1016/bexA region, as described by Kroll et al. (16). The PCR mix was as described for P2 typing except that primers IF (ATTAGCAAGTATGCTAGTCTAT) from IS1016 and IR (CAATGATTCGCGTAAATAATGT) from bexA (16) were used. Samples were cycled 30 times at 95°C for 1 min, 42°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s.

(vi) Southern blotting and hybridization.

Approximately 1 μg of chromosomal DNA extracted from H. influenzae isolates was digested with the restriction enzyme EcoRI (Pharmacia) as instructed by the manufacturer. DNA restriction fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, transferred to a positively charged membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham) in 0.4 M NaOH, and neutralized in 2× SSC (0.3 M NaCl, 30 mM trisodium citrate) substantially as described in reference 27.

Approximately 100-ng aliquots of pU038 (kindly provided by E. R. Moxon’s laboratory), IS1016 (PCR products, as described by St. Geme et al. [32], using Hib DNA as a template), and EcoRI-digested pBR322 (Pharmacia) probes were prepared by random primer labeling with [α-32P]dATP, using a Gigaprime DNA labeling kit (Bresatec). Plasmid pU038 contains a complete set of cap genes from Hib and an IS1016 element cloned into pBR322. Blots were prehybridized for 4 h at 65°C before addition of the labeled probes. The prehybridization mixture contained 0.3 M NaCl, 20 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5% nonfat skim milk powder, and 0.5 mg of herring sperm DNA per ml. Hybridization was for 16 h at 65°C, and posthybridization washes were at 65°C with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate–0.1× SSC. Membranes were then exposed to Kodak X-Omat AR film.

RESULTS

Characterization of Hib isolates by molecular typing.

Hib was cultured from nasopharyngeal swabs collected from 20 of the 41 (48.8%) infants in the longitudinal study between 1992 and 1994 (20). In 1996, 6 (30%) of 20 infants monitored to age 6 months in the same community were Hib colonized; all six were under 4 months of age and either had received the first dose only at 2 months of age or were too young for vaccination. Eight Hib isolates collected from these infants were compared with one colony from each of 39 available Hib-positive swabs collected from the 20 infants between 1992 and 1994.

Serotyping of Hib isolates was confirmed by PCR using primers for type b-specific sequences (b1 and b2) (5); all 47 Hib isolates gave positive results. In addition, primers H1 and H2, directed to bexA, were used to identify encapsulation genes (37).

All Hib isolates had the IS-bexA deletion.

PCR across the IS-bexA deletion generates a PCR fragment that is diagnostic (Fig. 1). This approach detected the IS-bexA mutation in all 47 Hib isolates, suggesting that the isolates have the multiple-copy cap locus characteristic of strains in phylogenetic division I; they are thus potentially invasive (6).

Subtyping of Hib clones.

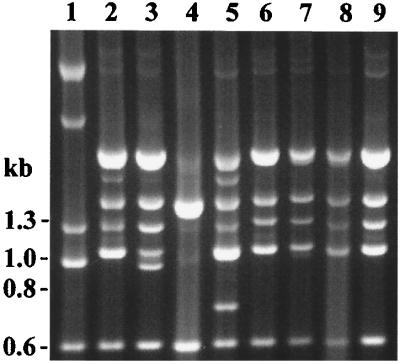

One colony from each of the 47 Hib-positive swabs was analyzed by PCR ribotyping. All Hib isolates from the community and the reference strain MinnA typed as Hib-PRT 1. These results are illustrated in Fig. 2 and summarized in Table 1.

FIG. 2.

PCR ribotype patterns of representative isolates of H. influenzae (HaeIII digest). Lane 1, Hib MinnA; lane 2, Hib-PRT 1 (608-1); lane 3, NCHi-PRT 1 (855-1); lane 4, Hib-PRT 2 (Hib isolated from a Darwin infant). This photograph was digitized with Deskscan II software and annotated with Corel Photopaint.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of H. influenzae isolatesa

| Group | Isolate no. | Infant | Examination dateb | ERIC type | β-Lactamase production | Amoxicillin MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992–1994 Hib isolates | 2-1 | 903 | 07-Jan.-92 | B | NTc | NT |

| 12-1 | 904 | 25-Mar.-92 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 14-2 | 904 | 20-May-92 | A | + | >256 | |

| 17-3 | 904 | 27-Oct.-92 | A | + | >256 | |

| 38-1 | 907 | 08-Sept.-92 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 46-2 | 908 | 05-Jan.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 50-1 | 909 | 24-Mar.-92 | A | − | 0.125 | |

| 60-1 | 911 | 14-Apr.-92 | A | + | >256 | |

| 61-3 | 911 | 18-June-92 | A | + | >256 | |

| 68-1 | 913 | 20-May-92 | B | − | NT | |

| 77-3 | 914 | 02-Dec.-92 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 125-1 | 923 | 21-July-92 | A | + | >256 | |

| 130-1 | 923 | 07-Jan.-93 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 309-1 | 923 | 04-Mar.-93 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 134-4 | 924 | 29-Oct.-92 | A | + | >256 | |

| 137-1 | 925 | 21-July-92 | A | + | >256 | |

| 143-2 | 926 | 01-Dec.-92 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 154-1 | 928 | 05-Jan.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 403-1 | 928 | 27-May-93 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 363-1 | 931 | 28-Apr.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 171-1 | 934 | 02-Dec.-92 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 274-1 | 934 | 10-Feb.-93 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 304-1 | 935 | 03-Mar.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 347-4 | 935 | 01-Apr.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 397-1 | 935 | 26-May-93 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 602-4 | 938 | 04-Oct.-93 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 619-3 | 938 | 08-Oct.-93 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 497-3 | 943 | 10-Aug.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 579-1 | 943 | 20-Sept.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 608-1 | 947 | 05-Oct.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 653-4 | 947 | 20-Oct.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 714-1 | 947 | 30-Nov.-93 | A | + | >256 | |

| 910-1 | 947 | 04-May-94 | B | − | 0.19 | |

| 585-1 | 950 | 21-Sept.-93 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 598-4 | 950 | 28-Sept.-93 | B | − | 0.19 | |

| 604-1 | 950 | 04-Oct.-93 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 640-1 | 950 | 19-Oct.-93 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 617-4 | 950 | 08-Oct.-93 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 707-4 | 950 | 30-Nov.-93 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 1996 Hib isolates | 0-1 | A36 | 02-Dec.-96 | A | − | 0.38 |

| 387-1 | A37 | 16-Oct.-96 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 918-1 | A29 | 27-Aug.-96 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 928-1 | A29 | 15-Oct.-96 | B | − | 0.25 | |

| 938-4 | A33 | 09-July-96 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 945-1 | A33 | 24-July-96 | B | − | 0.38 | |

| 474-1 | A47 | 04-Sept.-96 | A | + | >256 | |

| 507-1 | A21 | 22-Apr.-96 | A | − | 0.25 | |

| NCHi isolates | 273-1 | 932 | 10-Feb.-93 | D | NT | NT |

| 475-2 | 944 | 28-July-93 | E | NT | NT | |

| 520-1 | 944 | 24-Aug.-93 | E | NT | NT | |

| 855-1 | 938 | 21-Mar.-94 | F | NT | NT | |

| 871-3 | 938 | 04-Apr.-94 | F | NT | NT |

All strains were PRT 1.

Day-month-year.

NT, not tested.

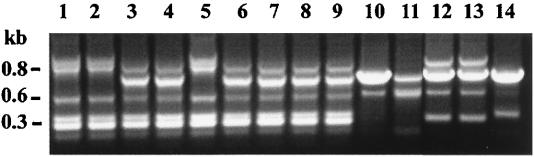

The same isolates were typed by PCR fingerprinting using primers directed at ERIC sequences (35, 36). Among the 47 Hib-PRT 1 isolates, two distinct ERIC PCR fingerprinting patterns, A and B, were observed at similar frequencies (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

ERIC PCR fingerprinting patterns of H. influenzae. Lanes 1, 2, and 5, Hib-PRT 1/ERIC A; lanes 3, 4, and 6 to 9, Hib-PRT 1/ERIC B; lane 10, NCHi-PRT 1/ERIC D; lane 11, NCHi-PRT 1/ERIC E; lanes 12 and 13, NCHi-PRT 1/ERIC F; lane 14, Hib-PRT 2/ERIC C (Hib isolated from a Darwin infant). The image was digitally acquired by using Bio-Rad GelDoc 1000 and annotated with Corel Draw.

Dynamics of Hib colonization.

Hib was cultured on more than one occasion from 10 infants in the 1992–1994 study and 2 infants examined in 1996. Periods of Hib detection in these infants varied from 2 weeks to 8 months. ERIC PCR fingerprinting demonstrated that five infants in the 1992–1994 longitudinal study carried ERIC types A and B at separate times, suggesting that there was sequential colonization with different Hib strains or potentially dual carriage with only one ERIC type detected (data summarized in Table 1).

β-Lactamase production and amoxicillin resistance.

Of 38 Hib isolates from 1992 to 1994 tested, 20 were amoxicillin sensitive, with MICs from 0.125 to 0.5 μg/ml. For 18 amoxicillin-resistant isolates, MICs were greater than 256 μg/ml. Of eight Hib isolates from 1996, one was amoxicillin resistant (MIC > 256 μg/ml) and the remainder were amoxicillin sensitive, with MICs from 0.25 to 0.38 μg/ml. All resistant isolates were β-lactamase producers.

Correlation of ERIC pattern with β-lactamase production.

Among the Hib isolates available for testing, all ERIC type B isolates were non-β-lactamase producers and 18 (81.8%) of 21 ERIC type A isolates were β-lactamase producers. This association suggests that β-lactamase production is chromosomally controlled in these isolates.

NCHi isolates exhibited the Hib PCR ribotype.

Previously, NCHi isolates from 10 infants of the 41 enrolled in the study were PCR ribotyped. Among 432 NCHi isolates recovered from 141 nasopharyngeal and ear discharge swabs, 46 different PCR ribotypes were detected (28). The marker PCR ribotype for the common Hib clone (Hib-PRT 1) was also detected among the nonencapsulated population, and we refer to these isolates as NCHi-PRT 1. The NCHi-PRT 1 strain was cultured from the nasopharynx or ear discharge of 3 of the 10 infants.

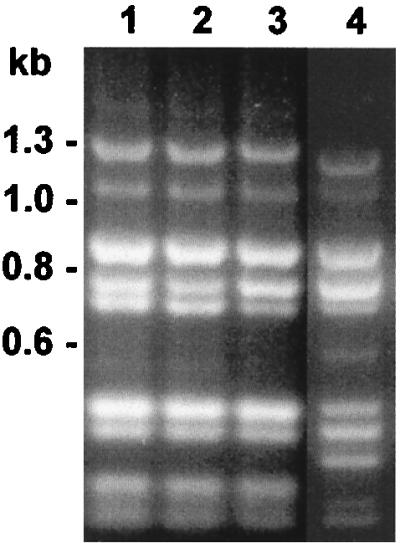

To further explore the associations of the PRT 1 pattern (generated by HaeIII) in nonencapsulated and type b isolates, we measured restriction fragment length polymorphisms in rRNA operons, using ApoI. Although rRNA operons of NCHi were polymorphic for internal ApoI sites (Fig. 4, lanes 1 to 5), all NCHi-PRT 1 isolates and several Hib-PRT 1 isolates tested were identical by ApoI PCR ribotype patterns (Fig. 4, lanes 6 to 9). These results preclude the possibility of chance identity of NCHi-PRT 1 and Hib-PRT 1 restriction patterns, using HaeIII within the rRNA operons.

FIG. 4.

ApoI PCR ribotype patterns of H. influenzae. Lane 1, NCHi 621-1 (HaeIII PRT 4); lane 2, NCHi 473-22 (HaeIII PRT 3); lane 3, NCHi 413-1 (HaeIII PRT 51); lane 4, NCHi 521-1 (HaeIII PRT 2); lane 5, NCHi 599-4 (HaeIII PRT 17); lane 6, NCHi 273-1 (HaeIII PRT 1); lane 7, NCHi 855-1 (HaeIII PRT 1); lane 8, Hib MinnA (HaeIII PRT 1); lane 9, Hib 608-1 (HaeIII PRT 1). The image was digitally acquired by using Bio-Rad GelDoc 1000 and annotated with Corel Draw.

ERIC PCR fingerprinting of the NCHi-PRT 1 isolates.

In contrast to the conserved patterns of rRNA operons of NCHi-PRT 1 isolates, ERIC PCR fingerprints were more diverse; among five NCHi-PRT 1 isolates cultured from three infants, three different ERIC PCR patterns were observed (Fig. 3 and Table 1). This result suggests that other loci have diverged to a greater degree than the ribosomal operons in NCHi.

Like NCHi, the NCHi-PRT 1 isolates lacked genes for capsulation.

To identify remnant cap sequences, 11 NCHi-PRT 1 isolates and at least 2 representative isolates of the 45 other NCHi PCR ribotypes identified to date were amplified by using primers to the bexA region (H1 and H2) and the type b-specific region (b1 and b2). None of the NCHi isolates generated a product with these primers. To confirm this result, genomic digests of selected NCHi and Hib isolates were probed with pU038, a probe containing capsule gene sequences, an IS1016 sequence, and a portion of pBR322 (32). We found that only Hib strains hybridized to cap sequences in pU038; NCHi strains which showed any hybridization with this probe also demonstrated the same pattern of hybridization when probed with IS1016 or pBR322 alone and hence were scored as negative for cap sequences. Thus, none of the NCHi-PRT 1 isolates or other selected NCHi isolates contain detectable remnant capsule sequences.

P2 gene sequences are highly conserved in Hib isolates, unlike in the NCHi-PRT 1 isolates.

P2 genes of several Hib-PRT 1 isolates were sequenced through loops 4 to 6 of the P2 gene. The Hib-PRT 1 nucleotide sequences differed by two bases from the MinnA strain sequence, with translated regions identical to those in MinnA (accession no. J03359). Furthermore, the P2 sequence of a Hib-PRT 1 isolate from 1996 was identical with that of earlier Hib-PRT 1 isolates collected in 1992 to 1994; this finding supports a high level of P2 conservation among Hib isolates.

In contrast, the P2 gene sequence of one NCHi-PRT 1 isolate differed markedly from that of Hib-PRT 1. The P2 protein of NCHi is subject to immune pressure (38) and, as a result, demonstrates a great deal of heterogeneity among strains. We previously reported that the NCHi-PRT 1 isolate in question had the same P2 sequence as an NCHi-PRT 25 isolate; this was most likely a result of horizontal gene transfer (31).

DISCUSSION

Hib continues to circulate in the community under study.

The PRP-OMP Hib vaccine was introduced to the community in this study in mid-1993 for children under 5 years of age. Although infant carriage of Hib fell dramatically, it was not eliminated. Since early 1996, Hib has been isolated several times from infants under 6 months of age who were not fully immunized. We speculate that a reservoir of Hib is maintained in older children and adults which will be depleted only when herd immunity levels are sufficient to decrease the number of carriers below the critical level needed to maintain transmission to immunologically naive individuals.

Dynamics of Hib carriage.

Hib carriage is a dynamic process. ERIC typing split the Hib isolates into two groups in this study, with the apparent replacement of one variant by the other during several episodes of Hib carriage. With available data, we cannot decide whether the two variants of Hib were transmitted, and thus carried together, taking turns as the dominant strain, or whether there were separate episodes of colonization in infants who do not develop a strong immune response to the Hib polysaccharide capsule following natural exposure.

Amoxicillin-resistant, β-lactamase-producing Hib strains did not appear to have a selective advantage over amoxicillin-sensitive strains in this population, even though amoxicillin is commonly used in the community. Proportions of amoxicillin-resistant and -sensitive isolates did not change dramatically during the study; 7 (46.6%) of 15 Hib isolates from 1992 were amoxicillin resistant, compared to 10 (41.6%) of 24 in 1993 (numbers of Hib isolates in 1994 to 1996 were small). Furthermore, during Hib carriage, strain turnover was more often from an amoxicillin-resistant strain to an amoxicillin-sensitive strain (four of five episodes) than the converse.

Coexistence of β-lactamase-producing and -nonproducing strains.

From 1992 to 1994, β-lactamase-producing and -nonproducing strains coexisted in this population in relatively stable proportions, with no increase in amoxicillin-resistant strains and no evidence of transposition of β-lactamase genes to sensitive strains. This balance may be ecological in origin, with complementary adaptations of β-lactamase-positive and -negative strains; it is also possible that the genes are chromosomally determined and therefore less mobile than plasmid- carried genes. Furthermore, lateral movement of genes as in NCHi (for example, the P2 gene [31]) may be hindered in Hib, either because the capsule may act as a barrier to exogenous DNA or because of restriction-modification systems (24).

Possible explanations for the existence of Hib and NCHi with the same PCR ribotype.

There are several explanations for the existence of Hib and NCHi with the same PCR ribotype. Horizontal transfer of ribosomal operons is unlikely, as up to six different operons (as found in the H. influenzae Rd genome [7]) would have to be transferred. Second, convergent evolution of rRNA operons of two otherwise diverse H. influenzae organisms is also unlikely. The third and simpler explanation is that PRT 1 exists in both capsulated and nonencapsulated forms because of either uptake or loss of capsule DNA. The loss of capsule DNA seems more plausible, as reduction of the number of copies of cap is a well-recognized phenomenon (32) and the lack of capsule gene remnants indicates that all copies were deleted. Divergence of NCHi-PRT 1 strains at other loci can be explained in terms of the selective pressure on loci such as P2 once the capsular selective constraint was removed.

NCHi-PRT 1 isolates existed prior to the vaccination era.

If the NCHi-PRT 1 isolates were derived from Hib, capsule loss cannot be attributed to vaccine pressure, as NCHi-PRT 1 isolates were collected prior to the introduction of vaccination. Long-term coexistence of both forms may depend on complementary selective advantages. For example, NCHi may be better adapted for mucosal colonization, whereas Hib may resist phagocytosis or desiccation more effectively (12, 16).

Diversity of NCHi genome relative to Hib.

NCHi strains circulating in this community are highly diverse. We observed 46 different PCR ribotypes colonizing 10 infants over a 2- to 24-month period (28), and some of these types could be split further by P2 typing and random amplification of polymorphic DNA (31). Others have observed changes in the NCHi P2 gene in real time as a result of immunological pressure (38). In contrast, Hib appears to have a clonal population structure (24). In this study, the majority of Hib isolates in this community had the same PCR ribotype as the common MinnA strain. Furthermore, a representative local Hib isolate had an amino acid sequence identical to that of MinnA through loops 4 to 6 of P2, and the type A ERIC PCR fingerprint pattern in local Hib isolates differed only slightly from that of the MinnA strain.

In this situation where H. influenzae is highly endemic, characterized by a small population size (approximately 1,100) and carriage rates of H. influenzae in infants of virtually 100%, we may expect that NCHi strains are under a greater immunological selection pressure for variation in order to maintain endemicity, compared to typical Western settings. In addition, concurrent colonization with multiple strains is common in this population, which would provide sufficient opportunity for genetic recombination between strains.

Wider implications.

The observation that Hib is still circulating in the community is a cause for concern. If Hib vaccination levels fall, existing Hib clones could spread more widely. It is also theoretically possible that the uptake of capsule gene sequences by potentially invasive clones during concurrent carriage of Hib and NCHi strains could generate new Hib strains and cause a recurrence of Hib disease. However, we believe that it is unlikely that a new Hib variant could establish itself, even in a partially immunized population, when it also has to compete with existing strains. Nevertheless, there is a continuing need to promote Hib immunization and monitor H. influenzae carriage, particularly in areas where the organism is highly endemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Medical Research and the Public Health Research and Development Committee of the National Health and Medical Research Council Committee (Australia).

We are grateful to Mary Deadman and E. Richard Moxon’s laboratory for kindly providing pU038 and Patricia E. Moor for providing the MinnA strain. We also thank Tania Shelby-James, Mark Mayo, and the remainder of the Ear Team of the Menzies School of Health Research for collection and identification of isolates, Jan Bell and Susan Hutton for helpful discussion, and the families involved in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes W M. PCR amplification of up to 35-kb DNA with high fidelity and high yield from lambda bacteriophage templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2216–2220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell J, Grass S, Jeanteur D, Munson R S. Diversity of the P2 protein among nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae isolates. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2639–2643. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2639-2643.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corn P G, Anders J, Takala A K, Kayhty H, Hoiseth S K. Genes involved in Haemophilus influenzae type b capsule expression are frequently amplified. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:356–364. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falla T J, Crook D W M, Anderson E C, Ward J I, Santosham M, Eskola J, Moxon E R. Characterization of capsular genes in Haemophilus influenzae isolates from H. influenzae type b vaccine recipients. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1075–1076. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falla T J, Crook D W M, Brophy L N, Maskell D, Kroll J S, Moxon E R. PCR for capsular typing of Haemophilus influenzae. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2382–2386. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2382-2386.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falla T J, Dobson S R M, Crook D W M, Kraak W A G, Nichols W W, Anderson E C, Jordens Z J, Slack M P E, Mayon-White D, Moxon E R. Population-based study of non-typable Haemophilus influenzae invasive disease in children and neonates. Lancet. 1993;341:851–854. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)93059-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, FitzHugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L-I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardiner D, Hartas J, Currie B, Mathews J D, Kemp D J, Sriprakash K S. Vir typing: a long-PCR typing method for group A streptococci. PCR Methods Appl. 1995;4:288–293. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.5.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haase E M, Campagnari A A, Sarwar J, Shero M, Wirth M, Cumming C U, Murphy T F. Strain-specific and immunodominant surface epitopes of the P2 porin protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1278–1284. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1278-1284.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanna J N. The epidemiology of invasive Haemophilus influenzae infections in children under five years of age in the Northern Territory: a three-year study. Med J Aust. 1990;152:234–240. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb120916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoiseth S K, Gilsdorf J R. The relationship between type b and nontypable Haemophilus influenzae isolated from the same patient. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:643–645. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoiseth S K, Connelly C J, Moxon E R. Genetics of spontaneous, high-frequency loss of b capsule expression in Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1985;49:389–395. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.389-395.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoiseth S K, Moxon E R, Silver R P. Genes involved in Haemophilus influenzae type b capsule expression are part of an 18-kilobase tandem duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1106–1110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.4.1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroll J S, Loynds B M, Moxon E R. The Haemophilus influenzae capsulation gene cluster: a compound transposon. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1549–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroll J S, Moxon E R. Capsulation and gene copy number at the cap locus of Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:859–864. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.859-864.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroll J S, Moxon E R, Loynds B M. An ancestral mutation enhancing the fitness and increasing the virulence of Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:172–176. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroll J S, Zamze S, Loynds B, Moxon E R. Common organisation of chromosomal loci for production of different capsular polysaccharides in Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3343–3347. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3343-3347.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampe R M, Mason E O, Jr, Kaplan S L, Umstead C L, Yow M D, Feigin R D. Adherence of Haemophilus influenzae to buccal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1982;35:166–172. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.1.166-172.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leach A J. Ph.D. thesis. Sydney, Australia: University of Sydney; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leach A J, Boswell J B, Asche V, Nienhuys T G, Mathews J D. Bacterial colonization of the nasopharynx predicts very early onset and persistence of otitis media in Australian Aboriginal infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:983–989. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199411000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leach A J, Shelby-James T M, Morris P S, Mathews J D. Abstracts of the International Conference on Acute Respiratory Infections, Canberra, Australia. 1997. Impact of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate vaccine on Hib carriage in Aboriginal infants, abstr. W4F. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhlemann K, Balz M, Aebi S, Schopfer K. Molecular characteristics of Haemophilus influenzae causing invasive disease during the period of vaccination in Switzerland: analysis of strains isolated between 1986 and 1993. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:560–563. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.560-563.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munson R J, Bailey C, Grass S. Diversity of the outer membrane protein P2 gene from major clones of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1797–1803. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musser J M, Kroll J S, Moxon E R, Selander R K. Clonal population structure of encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1837–1845. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1837-1845.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musser J M, Kroll J S, Moxon E R, Selander R K. Evolutionary genetics of the encapsulated strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7758–7762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 4th ed.; approved standard. Vol. 17. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith-Vaughan H C, Kemp D J, Leach A J, Sriprakash K S, Shelby-James T M, Nienhuys T, Kemp K, Mathews J D. Presented at the 6th International Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media, Fort Lauderdale, Fla. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith-Vaughan H C, Leach A J, Shelby-James T M, Kemp K, Kemp D J, Mathews J D. Carriage of multiple ribotypes of non-encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae in Aboriginal infants with otitis media. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;116:177–183. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800052419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith-Vaughan H C, Sriprakash K S, Mathews J D, Kemp D J. Long PCR-ribotyping of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1192–1195. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1192-1195.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith-Vaughan H C, Sriprakash K S, Mathews J D, Kemp D J. Nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae in Aboriginal infants with otitis media: prolonged carriage of P2 porin variants and evidence for horizontal P2 gene transfer. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1468–1474. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1468-1474.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.St. Geme J W, III, Takala A, Esko E, Falkow S. Evidence for capsule gene sequences among pharyngeal isolates of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:337–342. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stuy J H. Transfer of genetic information within a colony of Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:1–4. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.1-4.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Alphen L, Jansen H M, Dankert J. Virulence factors in the colonization and persistence of bacteria in the airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:2094–2100. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Belkum A, Bax R, Peerbooms P, Goessens W H F, van Leeuwen N, Quint W G V. Comparison of phage typing and DNA fingerprinting by polymerase chain reaction for discrimination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:798–803. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.798-803.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Belkum A, Duim B, Regelink A, Moller L, Quint W, van Alphen L. Genomic DNA fingerprinting of clinical Haemophilus influenzae isolates by polymerase chain reaction amplification: comparison with major outer-membrane protein and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Med Microbiol. 1994;41:63–68. doi: 10.1099/00222615-41-1-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Ketel R J, de Wever B, van Alphen L. Detection of Haemophilus influenzae in cerebrospinal fluids by polymerase chain reaction DNA amplification. J Med Microbiol. 1990;33:271–276. doi: 10.1099/00222615-33-4-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogel L, Duim B, Geluk F, Eijk P, Jansen H, Dankert J, van Alphen L. Immune selection for antigenic drift of major outer membrane protein P2 of Haemophilus influenzae during persistence in subcutaneous tissue cages in rabbits. Infect Immun. 1996;64:980–986. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.980-986.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]