Abstract

Internalin is a surface protein that mediates entry of Listeria monocytogenes EGD into epithelial cells expressing the cell adhesion molecule human E-cadherin or its chicken homolog, L-CAM, which act as receptors for internalin. After observing that entry of L. monocytogenes LO28 into S180 fibroblasts, in contrast to that of EGD, did not increase after transfection with L-CAM, we examined both the expression and the structure of internalin in strain LO28. We discovered a nonsense mutation in inlA which results in a truncated protein released in the culture medium. Mutations leading to release of internalin were also detected in clinical and food isolates. These results question the role of internalin as a virulence factor in murine listeriosis.

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive bacterium responsible for severe food-borne infections (7). It is able to induce its own uptake into nonphagocytic cells, such as intestinal epithelial cells, and to spread from cell to cell using an actin-based motility process (for a review, see reference 8). Several L. monocytogenes strains have been used to analyze these processes and their regulation. In our laboratory, L. monocytogenes LO28 (serovar 1/2c), originally isolated from the feces of a healthy pregnant woman, has been used to study actin-based motility and regulation of virulence factors and to establish a chromosomal map (15). Invasion genes were mainly studied for strain EGD (serovar 1/2a), which was the first L. monocytogenes strain to be isolated during an epidemic among laboratory animals (13). EGD and LO28 are fully virulent in the mouse model (1, 6).

EGD entry into mammalian cells is mediated by the bacterial surface proteins InlA (internalin) (5) and InlB (2; for a recent review, see reference 8), which are both necessary and sufficient for entry into various cultured cell lines, each having its own specificity. InlA is an 800-amino-acid protein required for entry into the epithelial cell line Caco-2 and other cell lines expressing the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin, which acts as a receptor for internalin (5, 10, 12). InlB mediates entry in many other cell lines; its receptor is unknown. Internalin contains two repeat regions, a leucine-rich repeat region (LRR) and a B-repeat region. The C-terminal part of internalin contains an LPXTG motif which mediates anchoring of the protein to the peptidoglycan. While internalin can be detected in culture supernatants, it is mainly associated with the bacterial surface, and our group has shown recently that the associated form of internalin promotes entry into cells (9).

In the course of a comparative study, the invasiveness of strain LO28 was compared to that of strain EGD in the mouse fibroblast line S180 and in an S180 derivative transfected with L-CAM, the chicken homolog of E-cadherin. In agreement with previous results (12), entry of EGD into fibroblasts expressing L-CAM was approximately 60-fold higher than entry into S180 cells. This was not the case for strain LO28, which entered both S180 and S180(L-CAM) cells poorly. This result prompted us to examine both the expression and the structure of internalin in strain LO28.

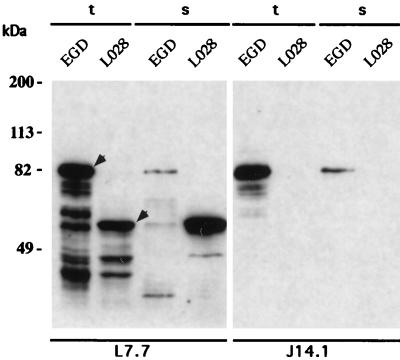

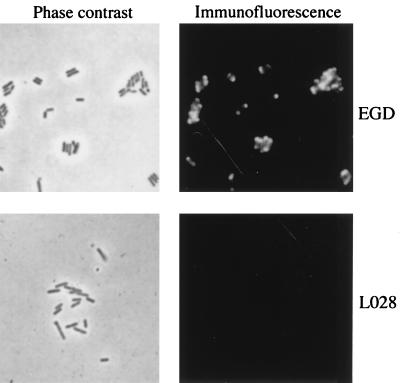

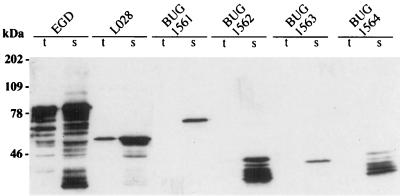

The presence of internalin in LO28 was analyzed in total cell extracts and in culture supernatants by using two internalin-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), i.e., L7.7, which is specific for the LRR, and J14.1, which is specific for the C-terminal part of internalin (Fig. 1) (11). The amounts of internalin detected in total extracts with MAb L7.7 were similar for both strains, strongly suggesting that expression of the inlA gene in LO28 was similar to that in EGD. However, the apparent molecular weight of the protein was clearly lower than that of EGD internalin, raising the possibility that LO28 internalin was either degraded or truncated. Moreover, a larger quantity of internalin was detected in LO28 culture supernatants than in EGD supernatants. Taken together, these results suggested that LO28 InlA could be released in the supernatant due to the absence of a cell wall anchoring motif. This hypothesis was supported by two observations: (i) in Western blot analysis of total extracts, LO28 internalin could not be detected with MAb J14.1 (Fig. 1), and (ii) LO28 internalin could not be detected on the bacterial surface by immunofluorescence staining with MAb L7.7 under conditions where EGD internalin could be detected (Fig. 2). The structure of the inlA gene was thus examined.

FIG. 1.

Western blot analysis of internalin in strains LO28 and EGD. The presence of internalin in sonicated total protein extracts (t) and culture supernatants (s) was analyzed, using an LRR-specific MAb, L7.7, and a C-terminus-specific MAb, J14.1 (11). The amount of material loaded corresponds to 10 μg of protein from bacteria harvested in exponential phase (A600 = 0.5). The estimated molecular masses for the LO28 and EGD internalins (indicated by arrowheads) are 60 and 80 kDa, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Detection of internalin on the bacterial surface by immunofluorescence. Cells of strains LO28 and EGD were harvested at the end of the log phase (A600 = 0.8) and labelled with the LRR-specific MAb L7.7 (11). Internalin was revealed by a Texas red-labelled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody (Biosys). Bacteria were visualized by phase-contrast microscopy and immunofluorescence staining.

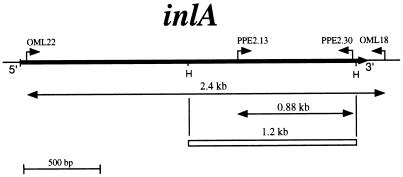

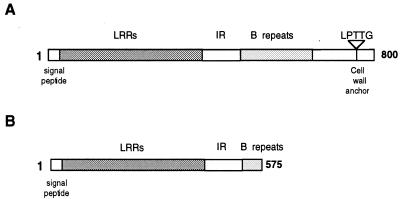

On the basis of Southern blots and PCR experiments, the inlA genes had been considered identical in length in strains EGD and LO28 (3, 5, 14). To confirm these results, a specific PCR amplification of LO28 and EGD chromosomal DNAs was performed with primers OML18 and OML22, which flank inlA in EGD (Fig. 3). Amplification of both DNAs resulted in the production of a 2.4-kb fragment corresponding to the expected size for inlA. HindIII digestion of these PCR products yielded the same three fragments of 1.2, 1.0, and 0.2 kb, suggesting that LO28 and EGD inlA genes are identical in size. This result did not exclude, however, the possibility of a nonsense mutation in LO28 inlA. To address this issue, we decided to clone the LO28 inlA gene and examine its nucleotide sequence. An 881-bp PCR fragment corresponding to the central part of inlA in EGD was used as a probe to clone, by colony hybridization under high-stringency conditions, the LO28 inlA gene from a HindIII chromosomal fragment library constructed in pUC18. Four clones harboring the same 1.2-kb fragment were obtained. The inserts of two of them were totally sequenced. The four silent mutations previously identified during a survey study of inlA polymorphism in several L. monocytogenes strains were detected (14). Moreover, we found, compared to EGD inlA (5), 10 additional single point mutations in LO28 inlA and a deletion of an adenine at position 1637. This frameshift mutation leads to the creation of a nonsense codon, TAA, for position 1729, generating an open reading frame encoding a 63-kDa protein lacking a cell wall anchor (Fig. 4). This result is in complete agreement with the apparent molecular weight of the protein detected by Western blotting and mainly present in the culture supernatant (Fig. 1).

FIG. 3.

The inlA gene. Primers OML18 (5′-TCTCCTTGATTCTAG-3′), OML22 (5′-AAAAAACGATATGTATG-3′), PPE2.13 (5′-CTTACCTAGTTATACAAA-3′), and PPE2.30 (5′-TTCATTGTACTTGTTGTG-3′) were used for specific inlA PCR amplification. The two HindIII restriction sites of inlA (H) are indicated. The amplified DNA fragments are shown. The sequenced DNA fragment (1.2 kb) is represented by an open rectangle.

FIG. 4.

Structural organization of InlA in strains EGD (A) and LO28 (B). LRRs, leucine-rich repeats; IR, interrepeats.

The unexpected structure of internalin in strain LO28 led us to analyze the structure of internalin in 26 other L. monocytogenes strains, including 14 clinical strains and 12 food isolates (Table 1). Four strains expressed truncated forms of internalin, with apparent molecular masses of 40, 45, 47, and 75 kDa (Fig. 5). Three of them (BUG 1562, BUG 1563, and BUG 1564) were food isolates, and one (BUG 1561) was a clinical isolate responsible for a case of septicemia. For all four, the protein was detected only in the culture supernatants and could not be detected on the bacterial surface by immunofluorescence (data not shown). From this preliminary epidemiological study, it appears that truncation of internalin is not a rare event. This result was unexpected since the inlA gene regions encoding the LRR and B-repeat regions had been shown to be genetically conserved (14). However, we had noticed several years ago that the capacity of LO28 to invade Caco-2 cells was much lower than that of EGD (4). Furthermore, like LO28, the four strains that secreted internalin failed to show enhanced invasion in L-CAM-transfected fibroblasts compared to that in nontransfected fibroblasts (Table 2). Taken together these data suggest that the low level of entry of LO28 into Caco-2 cells and L-CAM-transfected fibroblasts is due to the absence of surface-associated internalin. Whether the low level of entry is due to the soluble form of internalin, to an InlB-mediated mode of entry, or to another factor, such as another member of the internalin family, is not known.

TABLE 1.

L. monocytogenes strains used in this study

| Straina | Serovar | Source and specific property |

|---|---|---|

| EGD | 1/2a | Mackaness (1962) |

| LO28 (Bof 343) | 1/2c | Vicente et al. (1985) |

| CLIP 42398 (BUG 1573) | 4b | French epidemic, 1993 |

| CLIP 63713 BUG 1559 | 4b | French epidemic, 1995 |

| CLIP 61634 (BUG 1574) | 1/2a | Clinical isolate, 1995; septicemia |

| CLIP 62416 (BUG 1575) | 4b | Clinical isolate, 1995; septicemia |

| CLIP 63869 (BUG 1576) | 4b | Clinical isolate, 1995; septicemia |

| CLIP 64419 (BUG 1577) | 1/2b | Clinical isolate, 1995; meningitis |

| CLIP 66572 BUG 1560 | 4b | Clinical isolate, 1995; meningitis |

| CLIP 67325 (BUG 1578) | 1/2b | Clinical isolate, 1995; perinatal form |

| CLIP 61657 (BUG 1579) | 1/2a | Clinical isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 62624 (BUG 1580) | 1/2a | Clinical isolate, 1995; meningitis |

| CLIP 63976 (BUG 1581) | 4b | Clinical isolate, 1995; perinatal form |

| CLIP 64966 (BUG 1582) | 4b | Clinical isolate, 1995; perinatal form |

| CLIP 67086 (BUG 1561) | 1/2c | Clinical isolate, 1995; septicemia |

| CLIP 67989 (BUG 1583) | 4b | Clinical isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 61523 (BUG 1584) | NDb | Food isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 62177 (BUG 1585) | ND | Food isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 64846 (BUG 1652) | 1/2a | Food isolate, 1995; meat |

| CLIP 66462 (BUG 1586) | ND | Food isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 68314 (BUG 1587) | ND | Food isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 68942 (BUG 1588) | ND | Food isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 61842 (BUG 1589) | ND | Food isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 64467 (BUG 1590) | ND | Food isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 64920 (BUG 1563) | 1/2c | Food isolate, 1995; dairy product |

| CLIP 68091 (BUG 1591) | ND | Food isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 68454 (BUG 1592) | ND | Food isolate, 1995 |

| CLIP 69373 (BUG 1564) | 3a | Food isolate, 1995; fish |

CLIP refers to the Pasteur Institute collection, and BUG and Bof are the Cossart laboratory collection names. Strains indicated in bold letters secrete internalin (this work).

ND, not determined.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of internalin in food and clinical isolates. The presence of internalin in total cell extracts (t) and culture supernatants (s) from the indicated strains was analyzed with the LRR-specific MAb L7.7 (11). The amount of material loaded corresponds to 200 μl of cultures containing bacteria in stationary phase (A600 = 1.4).

TABLE 2.

Entry of EGD and of bacterial strains secreting internalin into L-CAM-transfected fibroblasts

| Strain | S180(L-CAM)/S180 ratioa |

|---|---|

| EGD | 60 ± 18 |

| LO28 | 3.3 ± 1.7 |

| BUG 1561 | 1.6 ± 0.7 |

| BUG 1562 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| BUG 1563 | 1.1 ± 0.6 |

| BUG 1564 | 2.0 ± 1.5 |

Ratio of the percentage of bacterial entry into S180(L-CAM) fibroblasts to that into nontransfected S180 fibroblasts. Invasion assays were performed by a slight modification of the method of Mengaud et al. (12) with a multiplicity of infection of approximately 15 bacteria per cell.

The role of internalin in listeriosis has not been completely elucidated. Since LO28 is fully virulent in the mouse model (1), the data presented here suggest that internalin is not absolutely critical for virulence in mice and/or that its function may be redundant with those of other proteins. One may note that most in vivo experiments have been performed with the mouse model. In this model, some aspects of human listeriosis, such as meningitis or meningoencephalitis, cannot be easily reproduced. Whether internalin plays a role in these clinical forms or whether it is one of the many factors participating in listeriosis remains to be thoroughly investigated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Reini Hurme and Marc Lecuit for helpful discussions and Shaynoor Dramsi and Violaine David for help with the immunofluorescence experiments. We thank Christine Jacquet and Jocelyne Rocourt (Centre National de Référence des Listeria) for the gift of the L. monocytogenes clinical and food isolates.

This work received financial support from the European Economic Community (grant BMH4-CT-0659), DRET (DGA 97-069), and the Pasteur Institute. Hélène Bierne is on the INRA staff.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cossart P, Vicente M F, Mengaud J, Baquero F, Perez-Diaz J C, Berche P. Listeriolysin O is essential for virulence of Listeria monocytogenes: direct evidence obtained by gene complementation. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3629–3636. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3629-3636.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dramsi S, Biswas I, Maguin E, Braun L, Mastroeni P, Cossart P. Entry of L. monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of InlB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:251–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dramsi S, Dehoux P, Lebrun M, Goossens P L, Cossart P. Identification of four new members of the internalin multigene family of Listeria monocytogenes EGD. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1615–1625. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1615-1625.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dramsi S, Kocks C, Forestier C, Cossart P. Internalin-mediated invasion of epithelial cells by Listeria monocytogenes is regulated by the bacterial growth state, temperature and the pleiotropic activator, prfA. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:931–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaillard J-L, Berche P, Frehel C, Gouin E, Cossart P. Entry of L. monocytogenes into cells is mediated by internalin, a repeat protein reminiscent of surface antigens from gram-positive cocci. Cell. 1991;65:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90009-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaillard J L, Berche P, Sansonetti P. Transposon mutagenesis as a tool to study the role of hemolysin in the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1986;52:50–55. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.50-55.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray M L, Killinger A H. Listeria monocytogenes and listeric infections. Bacteriol Rev. 1966;30:309–382. doi: 10.1128/br.30.2.309-382.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ireton K, Cossart P. Host pathogen interactions during entry and actin-based movement of Listeria monocytogenes. Annu Rev Genet. 1997;31:113–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lebrun M, Mengaud J, Ohayon H, Nato F, Cossart P. Internalin must be on the bacterial surface to mediate entry of Listeria monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:579–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecuit M, Ohayon H, Braun L, Mengaud J, Cossart P. Internalin of Listeria monocytogenes with an intact leucine-rich repeat region is sufficient to promote internalization. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5309–5319. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5309-5319.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Mackaness G B. Cellular resistance to infection. J Exp Med. 1962;116:381–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mengaud J, Lecuit M, Lebrun M, Nato F, Mazie J-C, Cossart P. Antibodies to the leucine-rich repeat region of internalin block entry of Listeria monocytogenes into cells expressing E-cadherin. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5430–5433. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5430-5433.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mengaud J, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Mège R M, Cossart P. E-cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of Listeria monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Cell. 1996;84:923–932. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray E G D, Webb R E, Swann M B R. A disease of rabbits characterized by a large mononuclear leucocytosis, caused by a hitherto undescribed bacillus Bacterium monocytogenes (n. sp.) J Pathol Bacteriol. 1926;29:407–439. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P, Berche P. The inlA gene required for cell invasion is conserved and specific to Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiology (Reading) 1996;142:173–180. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vicente M F, Baquero F, Perez-Diaz J C. Cloning and expression of the Listeria monocytogenes haemolysin in E. coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;30:77–79. [Google Scholar]