Abstract

There is a growing interest in the development of technologies to probe and direct in vitro cellular function for fundamental organoid and stem cell biology, functional tissue and metabolic engineering, and biotherapeutic formulation. Recapitulating many critical aspects of the native cellular niche, hydrogel biomaterials have proven to be a defining platform technology in this space, catapulting biological investigation from traditional two-dimensional (2D) culture into the 3D world. Seeking to better emulate the dynamic heterogeneity characteristic of all living tissues, global efforts over the last several years have centered around upgrading hydrogel design from relatively simple and static architectures into stimuli-responsive and spatiotemporally evolvable niches. Towards this end, advances from traditionally disparate fields including bioorthogonal click chemistry, chemoenzymatic synthesis, and DNA nanotechnology have been co-opted and integrated to construct 4D-tunable systems that undergo preprogrammed functional changes in response to user-defined inputs. In this Review, we highlight how advances in synthetic, semisynthetic, and bio-based chemistries have played a critical role in the triggered creation and customization of next-generation hydrogel biomaterials. We also chart how these advances stand to energize the translational pipeline of hydrogels from bench to market and close with an outlook on outstanding opportunities and challenges that lay ahead.

Keywords: Biomaterials, Hydrogels, Tissue Engineering, Drug Delivery, Synthetic Biology, Biofunctional, Bioresponsive

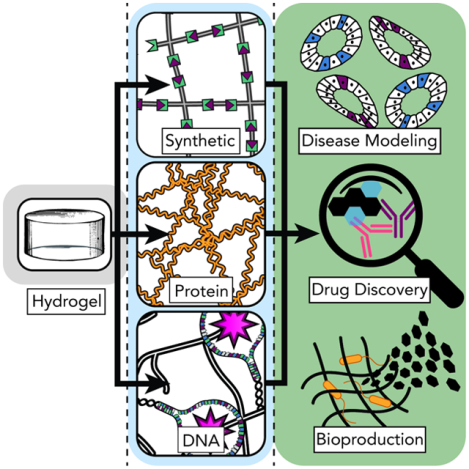

Graphical Abstract

eTOC:

Hydrogel biomaterials can directly impact different fields in biomedicine and beyond. Advances in the synthesis and modification of next-generation networks stem from the judicious (re)deployment of chemical and biochemical platforms, and the engineering of mechanisms to render these chemistries triggerable and modifiable in space and time. In this Review, we highlight these different chemistries – synthetic-, protein-, and DNA-based – and discuss how they stand push the field forward and energize the translation of biomaterials from bench to market and back.

1. Introduction

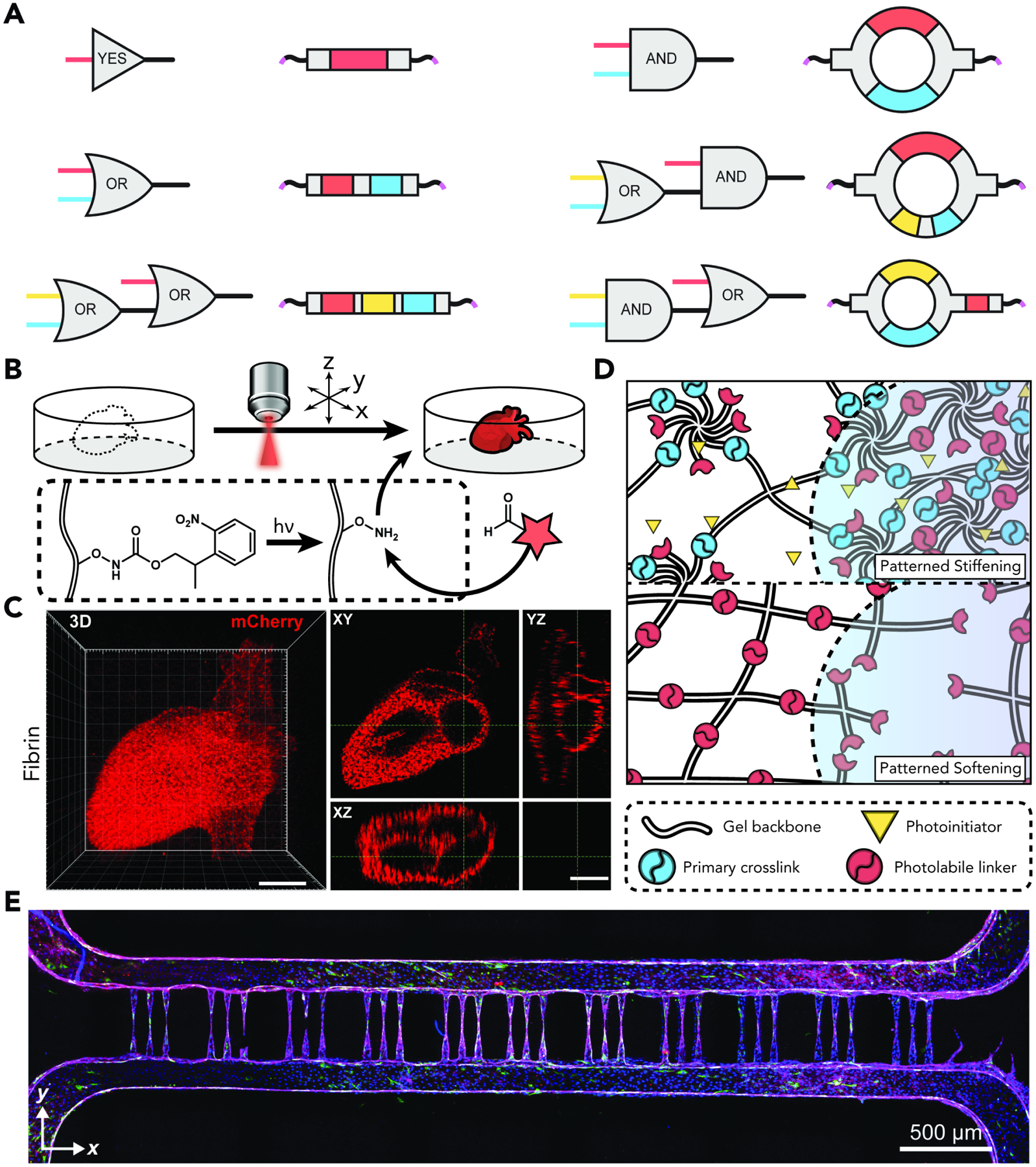

Historically, cellular biology has been interrogated in the context of two-dimensional (2D) cell culture milieux, comprised primarily of aphysiologically stiff substrates (e.g., glass, polystyrene dishes). While potentially revealing, such environments fail to mimic many essential aspects of the native cellular niche (e.g., dimensionality, viscoelasticity). Now intuitively recognized, many insights garnered through such experiments translate poorly, if at all, when moved to downstream in vivo studies. A second generation of investigation sought to leapfrog these shortcomings by exploiting hydrogels – water-swollen polymeric networks – for 3D cell encapsulation.1,2 Though these early efforts permitted extended cell culture in uniform materials with bulk characteristics closer to tissue than tissue-culture plastic, such constructs were static, monocellular, and isotropic. Recognizing that the tissue microenvironment is dynamically heterogenous in its physiochemical composition, cellular makeup, and structured architecture, the third and current generation of cell culture platforms has focused on biomaterials whose properties can be customized on demand, often in both 3D space and time (i.e., 4D), across a variety of scales.3 Towards this goal, materials scientists, chemists, and biologists have harnessed and driven diverse chemical and biological advances to engineer exquisitely modifiable and stimuli-responsive hydrogel biomaterials (Fig. 1).

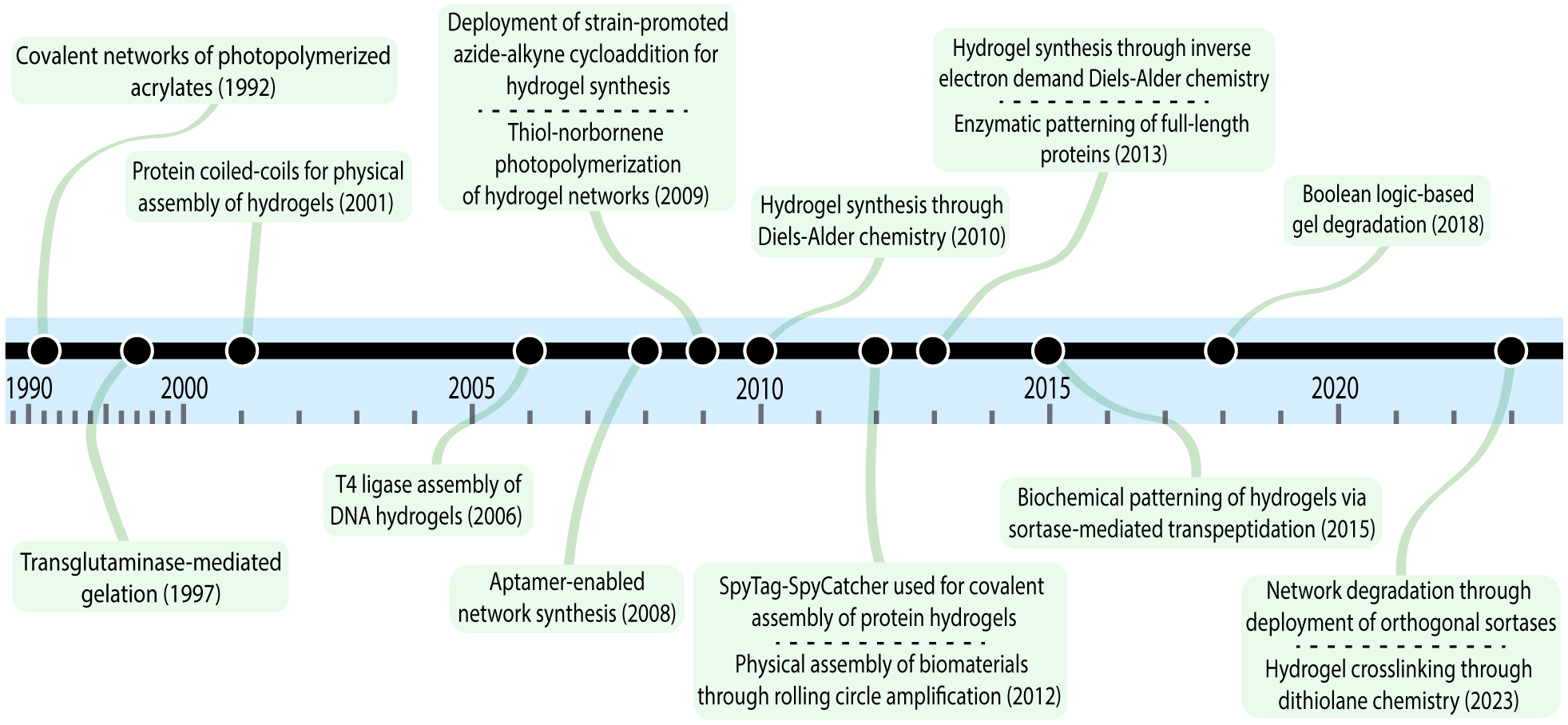

Figure 1. Key Milestones in the Deployment of New Chemistries for Hydrogel Biomaterial Synthesis.

Key milestones marking the first instance of the deployment of a particular chemistry for the synthesis of a hydrogel biomaterial.

Beyond spatial and/or temporal initiation of gelation, systems can be endowed with defined macroarchitecture, shape memory, reversible mechanics/viscoelasticity, and anisotropic biochemical signaling, all of which enable spatiotemporal control of cell fate and behavior. Clearly, this encoded dynamism holds immense potential for different fields within biomedicine.4,5 Importantly for biomaterial scientists and engineers, variable use cases call for dramatically different sets of properties. Within the same application space, developing a hydrogel matrix that seeks to capture bone tissue morphogenesis will require a resultant set of physicochemical properties that is qualitatively different than that geared for kidney or lung tissue engineering. Furthermore, moving our lens beyond tissue engineering proper, developing hydrogel matrices as therapeutic depots will also call for a substantially different set of design parameters; within this niche itself, whether a vehicle harbors synthetic drugs or living cells is another critical factor to consider.

As it stands, there is no shortage of problems to address, each requiring a bottom-up solution that is exquisitely tailored to meet it. (Bio)chemical advances – synthetic, semisynthetic, or biological in nature – are at the forefront of these exciting developments in biomaterials science. Through this Review, we will discuss the most common, most promising, and recently emerging reaction schemes to make and modify hydrogel biomaterials – including both those that proceed spontaneously and those that can be exogenously triggered – from polymeric, small-molecule, protein, DNA, and other biomolecular precursors. In drafting this Review, we found that charting the development of hydrogel biomaterial science and engineering was best tackled through the lens of understanding network crosslinking. By taking that as our starting point, we segmented the field into three main areas. Specifically, we looked at synthetic-organic networks and define those as hydrogels that are crosslinked through routine organic-type reactions. We also ventured beyond the fume hood and elaborated upon protein- and peptide-enabled chemistries that are themselves gaining much more traction as viable crosslinking strategies. Lastly, we expanded upon DNA-enabled methods and discuss how these have also gone from an academic curiosity into a full-fledged engineering platform, both for hydrogels and other materials. We then frame this discussion within the context of translational promise for these platform technologies and expand upon the challenges faced by hydrogel biomaterials en route to the clinic. It is our hope that this work will encourage researchers to probe new questions enabled by truly next-generation biomaterials and impress the notion that different chemical and biochemical platforms can be tuned and optimized to very particular applications at hand.

A key challenge in providing a comprehensive review and perspective of the field lies in its variety. Given the breadth of the hydrogel biomaterials space and the numerous strategies that have been developed for the creation and post-synthetic modification of networks, we categorize past efforts based on the nature of the assembly (i.e., covalent vs non-covalent crosslinking) and the extent of user control that it affords (i.e., spontaneous vs. triggerable modulation). In so doing, we hope to systematically delineate the relative advantages and disadvantages of each platform in as mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive a method as possible.

2. Chemical Synthesis of Hydrogel Biomaterials

Biomaterials science has greatly benefitted from the co-opting of chemistries initially deployed for different applications and then re-purposed for materials development. These manifold reaction platforms have proven to be largely agnostic with respect to the nature of the underlying material, enabling assembly of networks from a wide variety of starting reactants. Broadly, hydrogel materials can be synthetic, naturally derived, or a hybrid of the two. Synthetic hydrogels are made up of polymer chains that are synthetic themselves, including polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA). Lacking in biological epitopes in their base form, such materials are bioinert at best – a feature which may or may not be advantageous depending on the use-case being considered. Regardless, synthetic networks are readily modifiable, providing a “blank slate” upon which to engineer biological functionality.6 Alternatively, naturally derived networks consist of biopolymers in the form of polysaccharides (e.g., hyaluronic acid, chitosan, dextran, among others), proteins (e.g., fibrin, collagen, silk fibroin), or DNA. Innately endowed with biocompatibility, naturally derived networks can be sourced directly or recombinantly synthesized.7 Such off-the-shelf networks (e.g., Matrigel®, Geltrex™) promote desirable cellular functions including adhesion, spreading, and dynamic matrix remodeling. However, batch-to-batch variability presents obstacles to widespread and reproducible deployment. An alternative strategy to address this pitfall is to produce these networks in a pristine sequence-specific manner, such as is enabled through recombinant protein expression or DNA assembly via enzymatic, solid-phase, or biological replication-based methods.

Beyond the underlying material, an important design consideration – the focus of this review – is the reaction platform through which the hydrogel is formed, particularly whether the network is held intact through covalent or non-covalent bonds. Furthermore, some material-forming chemistries proceed spontaneously, leading to gelation upon simple mixing of the constituent macromers in solution. Other platforms undergo triggered formation, in that they typically require the action of an extraneous stimulus (e.g., temperature, pH, light) or a combination thereof to initiate the underlying gelation chemistry.

2.1. Spontaneous Hydrogel Formation

Given their simplicity and relative ease of onboarding, hydrogel formation chemistries that proceed spontaneously have become a cornerstone of recent biomaterials research. Classically, these platforms lead to network formation directly upon mixing of the constituent macromers in solution, proving most useful for applications such as cellular or biomolecule encapsulation into scaffolds for tissue engineering and drug delivery.

2.1.1. Spontaneous Gel Formation via Covalent Reaction

2.1.1.1. Synthetic Organic-Based

Owing to their high degree of tunability, crosslinking schemes that exploit synthetic organic reaction have propelled the field of hydrogel biomaterials forward to a largely unparalleled degree (Table 1). In fact, through rational modification of the starting macromers and employed gelation chemistry, reaction kinetics, network microarchitecture, and material mechanics/viscoelasticity can be exquisitely controlled. Since these chemistries have been profiled extensively in previous reviews,8,9 we limit our survey to only the most broadly used and recently developed platforms.

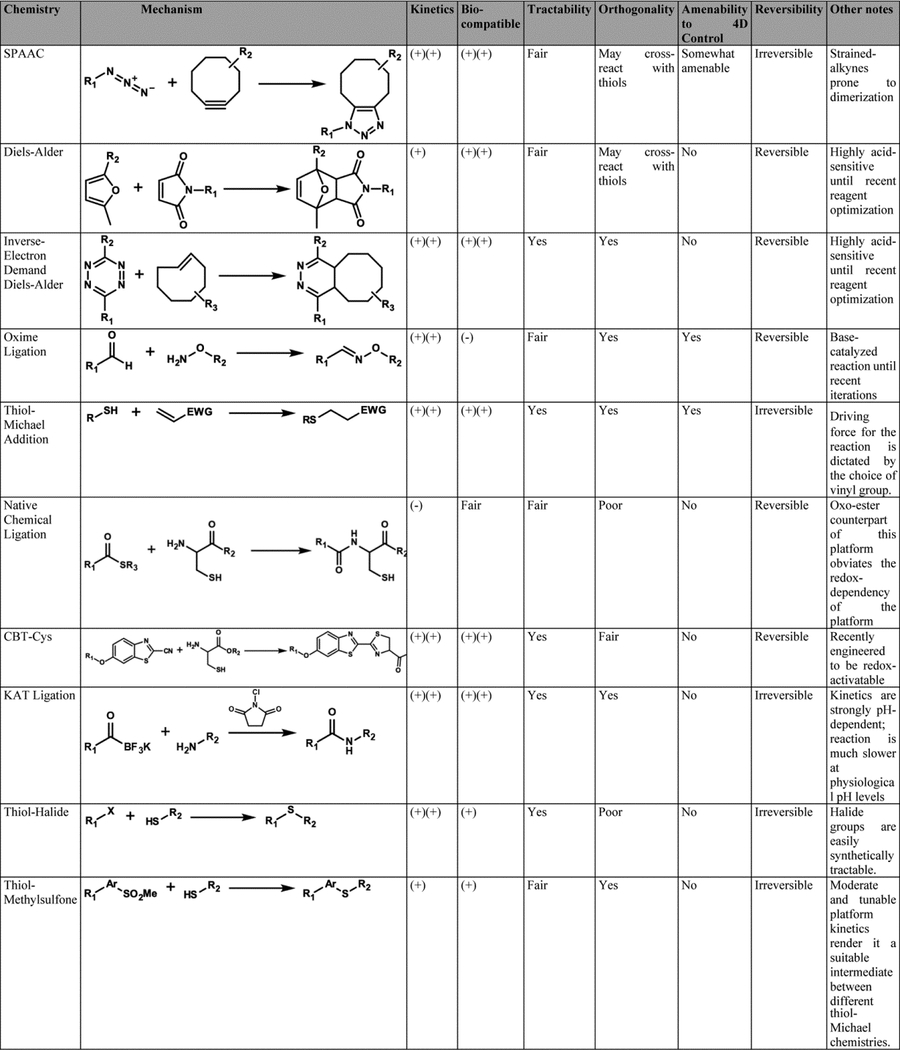

Table 1. Comparison of Chemical Platforms for Hydrogel Synthesis.

Widely used synthetic assembly schemes are compared based on their kinetic profile, biocompatibility, tractability, orthogonality, amenability to spatiotemporal control, and reversibility.

|

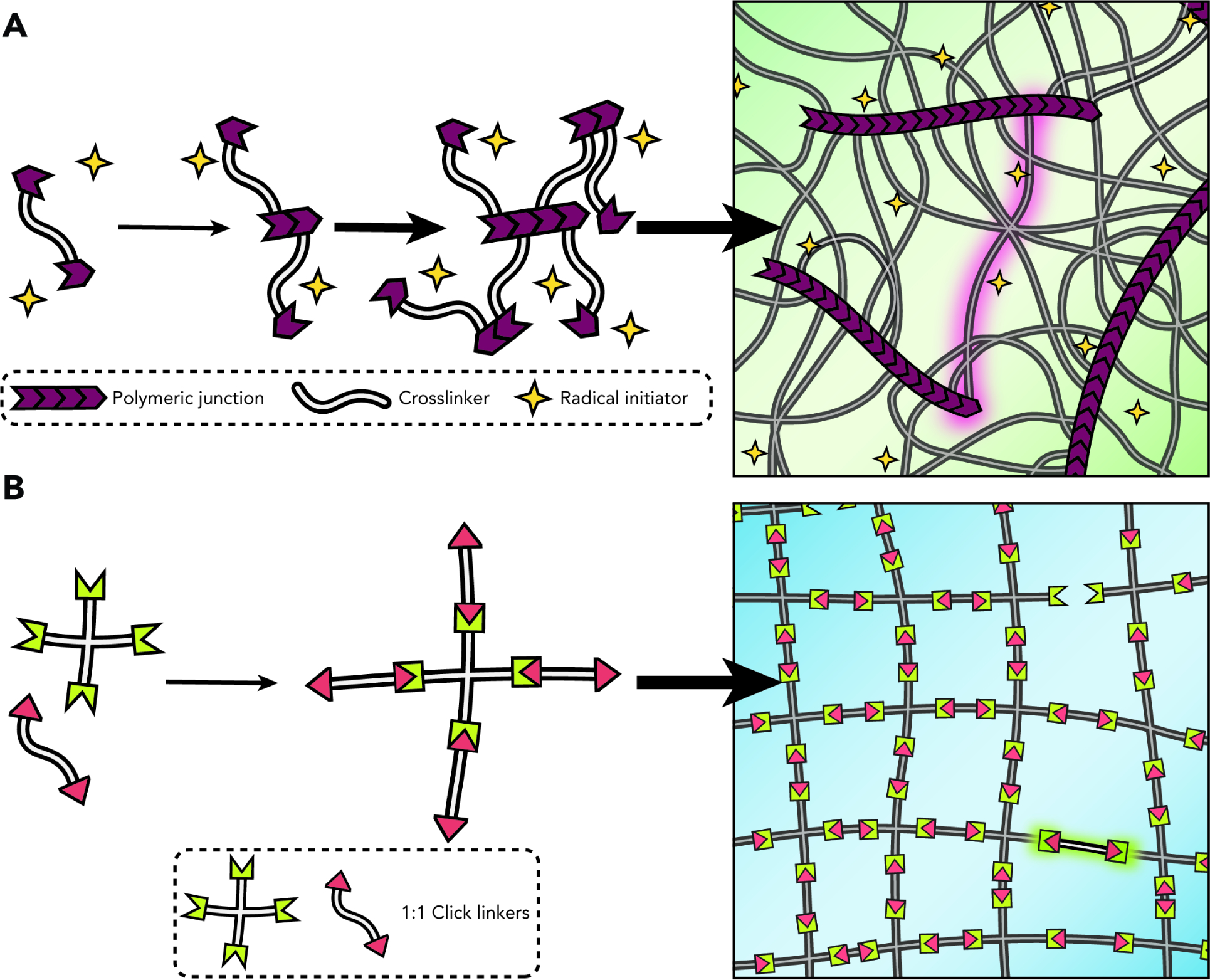

Step-growth polymerizations have become the most prominent synthetic crosslinking chemistries, whereby complementary reactive groups react specifically in a one-to-one manner. Directly contrasting most chain-growth chemistries in which reaction is propagated through active chemical radicals, such step chemistries generally proceed in a radical-free manner and lead to a more uniform hydrogel microstructure (Fig. 2). Not only does this hold immediate implications for the creation of more structurally sound therapeutic depots or extracellular matrix mimics, it also translates directly to adjacent avenues such as bioprinting where ultimate network integrity is predicated on the platform chemistry deployed.10 Lastly, many step chemistries can be considered “click”11 – a designation that is limited to reactions that are specific, high yielding, generate non-toxic products, and proceed in aqueous or otherwise benign solvents.

Figure 2. Chain-Growth vs. Step-Growth Chemistries for Hydrogel Network Synthesis.

(A) Radical-initiated chain-growth crosslinking results in a molecularly undefined and spatially heterogenous network.

(B) Click chemistry-mediated step-growth networks spontaneously form more homogenous and well-defined mesh structures, typically without the need for initiators.

Strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) represents a now-classic example of a click platform that has been co-opted successfully for the generation of hydrogel networks. Developed by the Bertozzi group as a non-toxic alternative to the conventional copper-catalyzed cycloaddition (CuAAC),12 ring-induced strain encoded within the alkyne moiety drives the reaction forward under physiological conditions and without the metal catalyst. Additionally, modifications to the strained-alkyne structure can directly modulate resultant kinetics and thereby accommodate use-cases with different gelation time requirements. Owing to its limited cross reaction with chemical moieties on natural biomolecules, the platform found use in and heralded an era of “bioorthogonal click chemistry”.13 Given its potential, it was subsequently co-opted for the cytocompatible synthesis of hydrogel biomaterials. Towards that end, DeForest and Anseth were the first to employ it for the synthesis of cell-laden hydrogels, using multi-armed PEG chains end-functionalized with azide groups and peptide chains capped with DIFO3 cyclooctyne moieties.14 SPAAC is now broadly used for hydrogel synthesis for a range of applications; for instance, the Haag group harnessed this platform for engineering PEG-based networks crosslinked with acid-labile benzacetal groups, thereby enabling cell capture and subsequent triggered release over a cytocompatible pH range.15 Additionally, SPAAC-based PEG networks have also shown promise as injectable embolic agents; for example, the Zhong group synthesized routine PEG-based matrices and successfully injected these in the auricular central artery of rabbits, enabling fast-flow blockage without the need for invasive surgical interventions.16 Promisingly, these gels demonstrated good cytocompatibility and degraded over the span of two days, a timespan which can be shortened or extended based on ultimate crosslinker design.

Similar to SPAAC, Diels-Alder (DA) is another widely used chemistry for cell encapsulation, but with additional avenues for modification afforded through its innate reversibility. DA platforms employ two starting groups – diene- and dienophile-modified macromers – that undergo a 1:1 cycloaddition upon mixing. Broad application of the chemistry was initially limited because of its reliance on acidic conditions to drive the DA reaction forward. Specifically, the first report by the Shoichet group that showcased this chemistry necessitated the reaction of furan- and maleimide-end-functionalized precursors at a pH of 5.5 to enable gelation at reasonable time-scales, precluding their use as encapsulating networks for cell culture.17 However, by replacing the furan diene with a more electron-rich methylfuran, the group successfully side-stepped such acid-dependence to enable cytocompatible network assembly at a pH level of 7.4 on the order of minutes, and were able to encapsulate 5 different cancer cell lines, highlighting the portability of the system.18 Since these foundational reports, the relative ease of onboarding this platform from a synthesis standpoint, coupled with its aforementioned reversibility, have made it a staple in different biomaterial labs looking to recreate near-native cellular environments19 or develop new therapeutic delivery modalities.20,21

The inverse-electron demand Diels-Alder (IEDDA) reaction has been gaining significant traction as a bioorthogonal crosslinking chemistry since the publication of foundational reports deploying it for in vivo cellular labeling22 and endogenous epitope targeting.23 First utilized for biomaterial formation by the Anseth group as a synthetically more tractable24 platform than SPAAC,25 its reaction involves a tetrazine and an appropriate dienophile group (e.g., norbornene, trans-cyclooctene). Specifically, the first proof-of-concept for this chemistry in a hydrogel context relied on the reaction of PEG macromers end-functionalized with a benzylamino tetrazine with a dinorbornene synthetic peptide, and showed that the approach is highly suitable for network formation, cellular encapsulation, and potential post-synthetic patterning. Stemming from its promising and tunable kinetics, which are readily modulated by rationally introduced modifications to either the tetrazine or the dienophile, the chemistry is rapidly gaining widespread use as a workhorse chemistry in manifold chemical biology applications (reviewed here26,27) and as a viable hydrogel crosslinking strategy. Emblematic of the promise of the latter, the Vega group systematically investigated different ratios and multiple substitutions of the starting tetrazine or norbornene end-functionalized groups, and probed for downstream effects in their obtained hyaluronic acid networks. Their study showed direct and straightforward encoding of ultimate hydrogel mechanical properties through easily adjustable starting macromer concentrations, relative stoichiometry, and degree of substitution with photopatternable methacrylic anhydride moieties.28 The tetrazine-norbornene chemistry was also employed for the creation of hydrolytically-degradable alginate hydrogels, which was achieved through oxidation of the polymer backbone prior to gel crosslinking.29 By controlling this initial extent of oxidation (e.g., unoxidized vs. 5% oxidized), mechanical properties and degradation timescales could be exquisitely controlled by the user.

Oxime ligation30 is another commonly employed platform for the synthesis of hydrogel biomaterials. It involves the reaction of a hydroxylamine and a carbonyl (e.g., aldehyde, ketone), forming an oxime linkage and a water byproduct. Similar to DA, oxime ligation can be reversed with pH, making it suitable for the creation of dynamically switchable matrices. While early examples of this strategy were hampered by slow gelation times (on the order of hours) at physiological pH,31 the Becker group found that tuning pH and the aniline catalyst concentration can yield gelation in seconds.32 This newfound tunability enabled pristine control over network mesh size and modulus based on selected gelation parameters.33 There are now multiple successful reports of oxime-crosslinked hydrogels, such as for the creation of HA-based vitreous substitutes34 and the culture of tumor spheroids.35

Thiol-involved reactions also represent a very common route towards hydrogel biomaterial synthesis. In fact, thiols can react with a number of different chemical groups and are found natively on proteins (i.e., cysteine amino acids), making thiol-based reactions uniquely suited for applications interfacing materials and polypeptides.36 The most prominent example of such “thiol-X” reactions is the thiol-ene platform,37 which involves the reaction of a thiol group with an alkene. Classically, the thiol-ene reaction is radical-mediated via photochemical or thermal initiation. While triggering gelation is important given the ensuant spatiotemporal control – a topic discussed at length in a subsequent section – propagating free radicals can be cytotoxic and non-specifically reactive, making such strategies much less attractive for applications that require interfacing with living cells. A powerful workaround is the adoption of a thiol-ene reaction that harnesses the reaction of a thiol with more electron-deficient alkenes (e.g., maleimides, vinyl-sulfones). Referred to as thiol-Michael additions,38 these reactions are typically base- or nucleophile-catalyzed, and progress through anion-propagation rather than through a free radical. Given these relative advantages, in addition to their powerful kinetics and resultant product stability, such reactions have been widely used as a thiol-involved reaction for the creation of biomaterials. As a result, they have been widely applied for the crosslinking of a variety of hydrogels developed for post-surgical implants,39 stem cell encapsulation and maintenance,40 lineage specification,41 among others.

Less employed but still worthy of note as a synthetic crosslinking platform is “native chemical ligation”,42 which enabled the Messersmith group to generate PEG-based gels from multi-armed macromers functionalized with either an N-terminal cysteine or a thioester,43 with follow-up work establishing the system’s suitability for pancreatic islet cell encapsulation.44 A subsequent report by the group sought to eliminate the crosslinking chemistry’s dependence on reducing conditions, leading to an oxo-ester-mediated reaction rather than the more common thioester.45

Still more synthetic organic-based reaction schemes are being developed for spontaneous hydrogel formation, promisingly including the luciferin-inspired cyanobenzothiazole-cysteine (CBT-Cys) reaction,46 potassium acyltrifluoroborate (KAT) ligation,47 and alternative thiol-X reactions (e.g., thiol-halide,48 thiol-epoxy,49 thiol-methylsulfone50).

Summarily, multiple click-type platforms have now been developed for the covalent synthesis of gels. Since each has comparative advantages with regards to different metrics such as kinetics, reversibility and temperature-dependence, the decision to deploy one or the other should ultimately be made on a use-case basis.

2.1.1.2. Protein-Based

Protein-enabled chemistries harness platforms evolved by nature to genetically encode recognition and reactivity (Table 2). While protein-based interactions are predominantly non-covalent, there exist an increasing number of schemes enabling covalent network formation, most generally based on split-fragment reconstitution.51 A quintessential example is the SpyTag-SpyCatcher system, developed by the Howarth lab through splitting the fibronectin-binding domain of Streptococcus pyogenes prior to rational fragment engineering.52 Reconstitution is highly energetically favorable upon splitting; protein-protein ligation occurs rapidly through the formation of an isopeptide bond between the Lysine 31 on the SpyCatcher protein and Aspartate 230 on a short SpyTag peptide. In their seminal work, the Arnold and Tirrell groups exploited SpyTag/SpyCatcher repeating motifs interspaced by telechelic elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) to engineer fully protein-based covalently assembled networks.53 Subsequent work by Li employed the self-same strategy to synthesize protein networks based on globular domains (GB) rather than the telechelic elastin, showcasing the versatility of fragment reconstitution-based approaches with respect to different forms of protein folds.54 Moreover, this system was also co-opted by the Niemeyer group to assemble flow biocatalysis hydrogel units; after expressing the two tetrameric enzymes dehydrogenase (LbADH) and glucose-1-dehydrogenase (GDH) as genetic fusions with either SpyTag or SpyCatcher, component mixing led to hydrogel bioreactor formation at near-quantitative yields without expensive co-factors.55

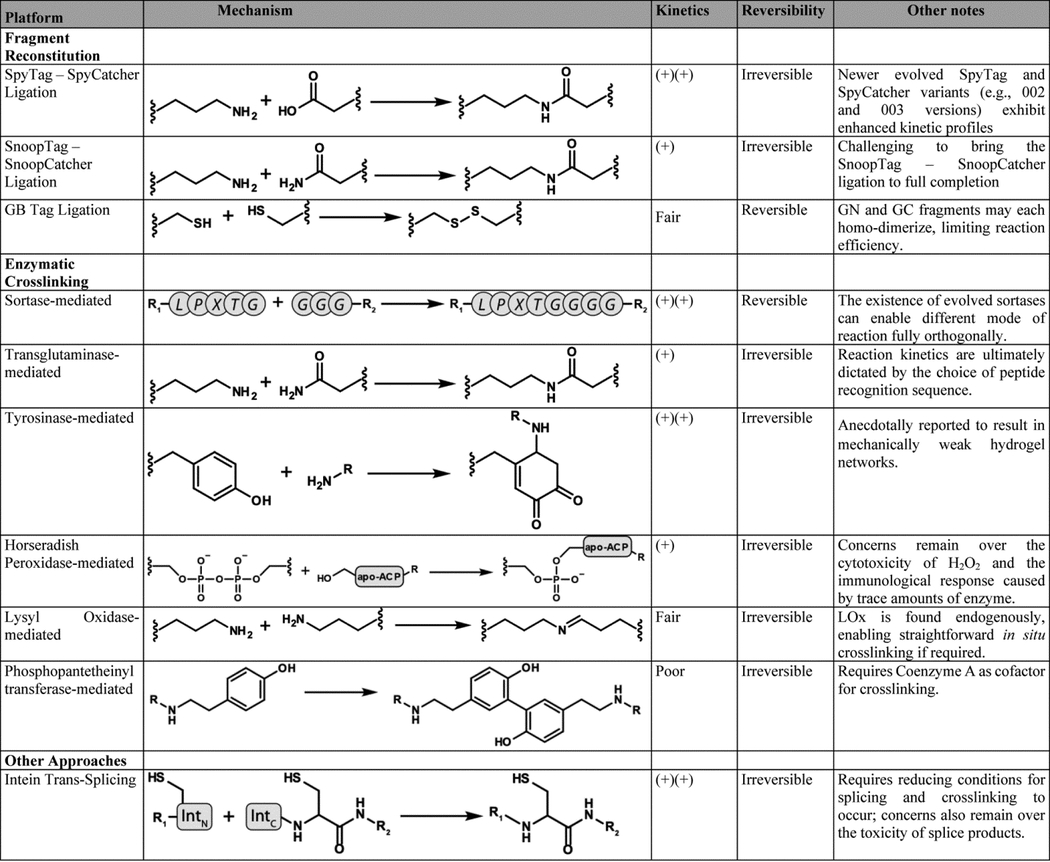

Table 2. Comparison of Protein-Enabled Approaches for Hydrogel Synthesis.

Widely used protein-enabled assembly schemes are compared based on their kinetic profile and reversibility. Additional notes regarding the platform are provided when appropriate.

|

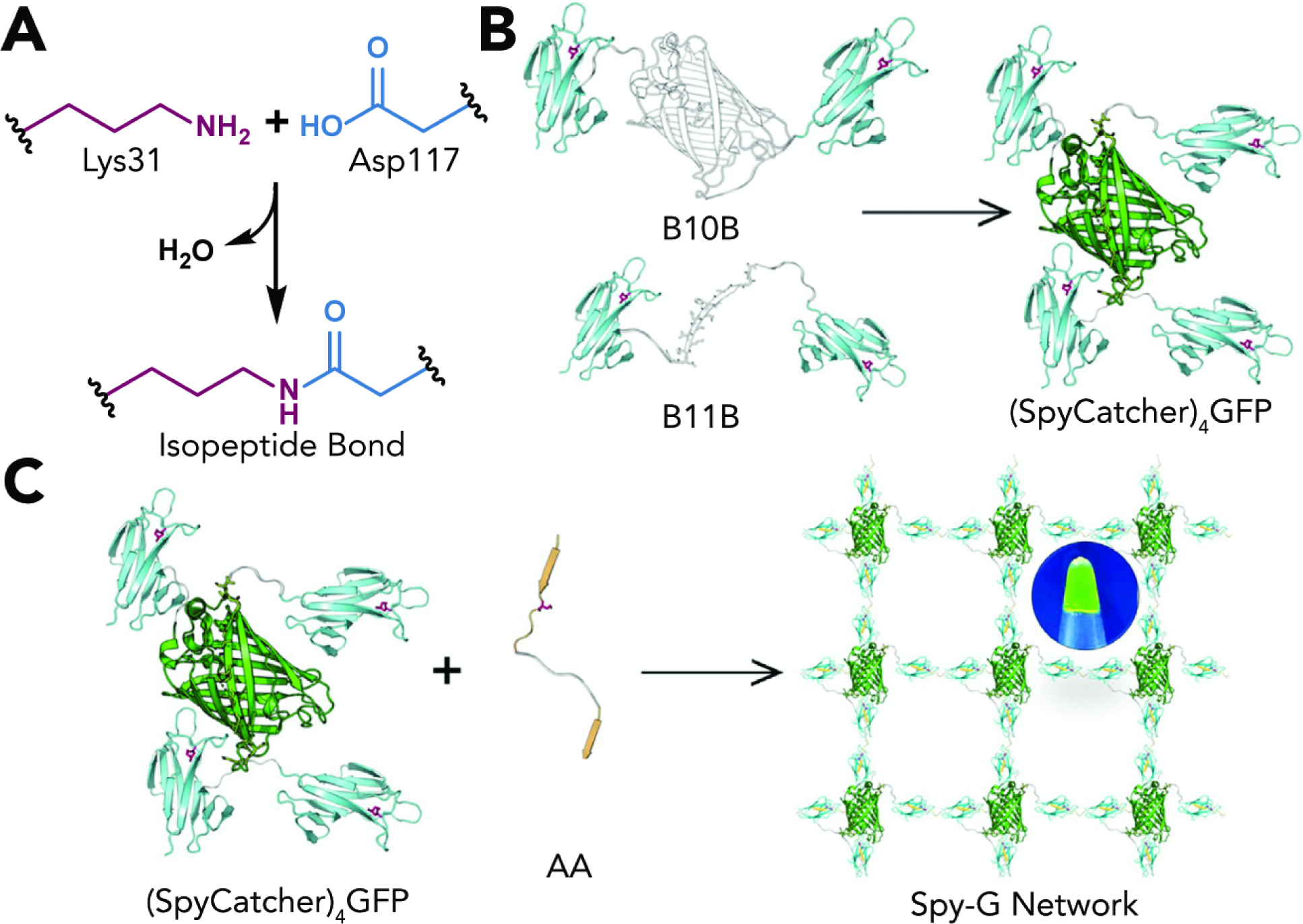

A related strategy uses proteins that are artificially split and maintain a high thermodynamic driving force for spontaneous reconstitution. A prominent example of this approach is demonstrated by the Sun group, who supplement a SpyTag- and SpyCatcher-based strategy with split GFP reconstitution to create highly tunable protein-based networks, analogous to synthetic hydrogels formed via step-growth polymerization of multifunctional macromers (Fig. 3).56

Figure 3. Hydrogel Synthesis through SpyTag-SpyCatcher Ligation and Split GFP Reconstitution.

(A) SpyCatcher and SpyTag react spontaneously upon mixing and form an isopeptide bond between Lys31 on SpyCatcher and Asp117 on SpyTag.

(B) Star-like proteins bearing reactive 4 reactive SpyCatchers physically assemble through spontaneous reconstitution of split GFP. Adapted with permission from Yang et al.47 Copyright 2020, Elsevier.

(C) Covalent crosslinking of 4-arm star-like protein macromers with difunctional SpyTag reagents yields a “Spy-G” hydrogel. Reproduced with permission from Yang et al.47 Copyright 2020, Elsevier.

Moving forward, the main limiting factor in developing networks with added functionality lies in the availability of amenable split protein pairs. Indeed, newer splits are continuously being evolved to hold better kinetic and thermodynamic assembly profiles57 or reaction orthogonal to existing systems.58 However, as our understanding of protein design develops,59 we anticipate that the development of computationally generated de novo proteins60 will expand the palette of genetically encoded click-type chemistries that can induce gelation, both alone and in tandem with other orthogonal pairs.

Though relatively underexplored in biomaterials science, another potentially powerful approach exploits inteins to assemble protein-based networks. Inteins consist of autocatalytic protein processing domains that assemble, link their concomitant flanking “extein” proteins, and excise themselves out without the need for an exogenous cofactor or catalyst.61 While harnessed extensively in the protein-protein ligation and semisynthesis sphere, inteins hold exciting potential towards the creation of entirely protein-based covalent materials. One example was demonstrated by the Chen group, who expressed trimeric CutA proteins as Nostoc Punctiforme (Npu) intein fusions to rapidly generate pH- and temperature-stable networks for enzyme encapsulation.62 A growing library of orthogonal and well-behaved intein pairs63 with robust reaction profiles may enable hydrogel assembly with increasing levels of biological functionality.

2.1.2. Spontaneous Gel Formation via Non-Covalent Reaction

2.1.2.1. Synthetic Organic-Based

While covalent linkage of macromolecular precursors yields stably persistent hydrogels, utilization of non-covalent reaction schemes to create hydrogel networks uniquely affords network dynamism; physically assembled gels can be formed and modified in a user-directed fashion, often including in response to applied shear.64,65

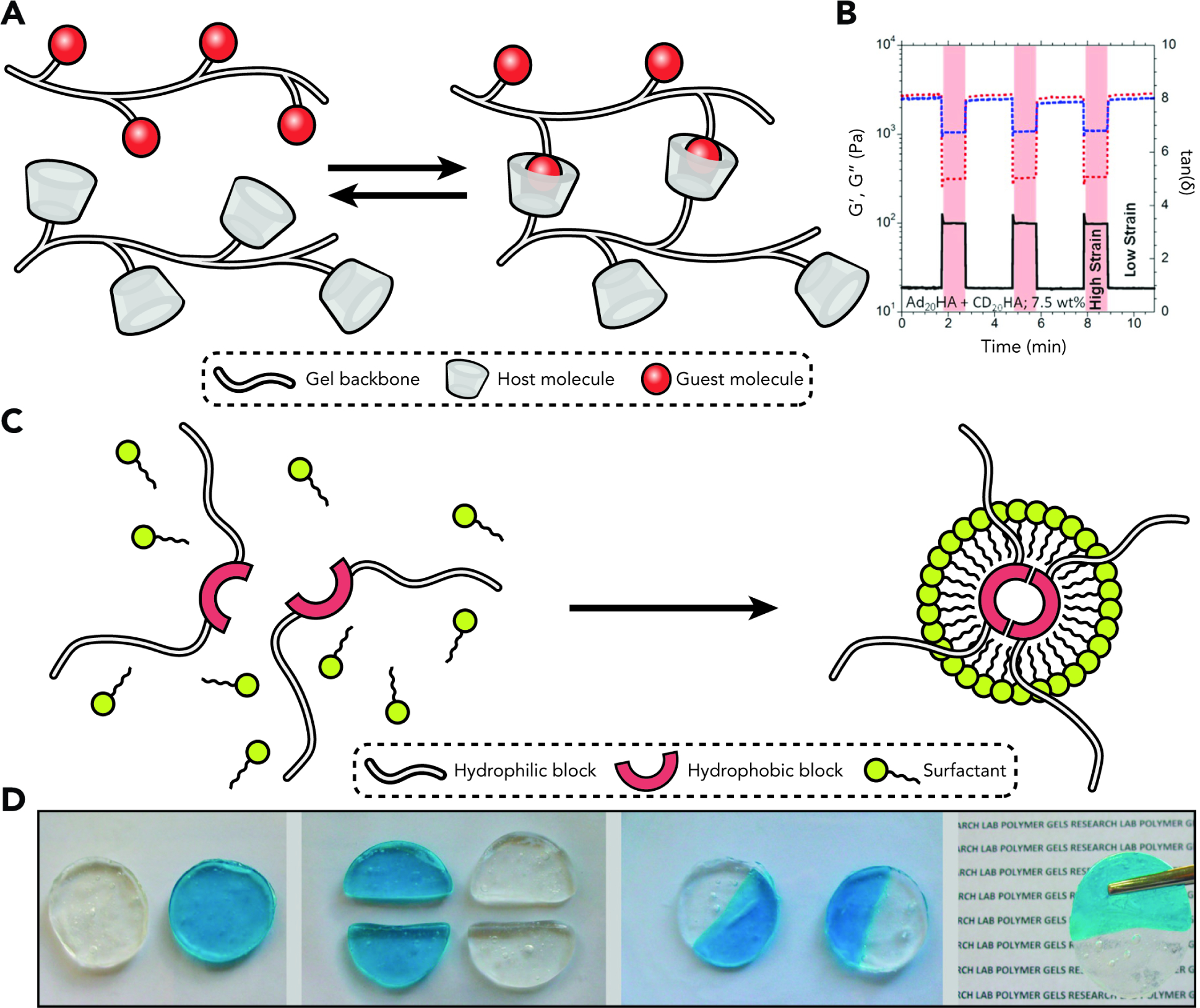

A widespread example of non-covalent synthetic reactions utilized for biomaterial formation is that of host-guest chemistries – a supramolecular chemistry in which structural relationships define the assembly of two species – best typified by a cyclodextrin host and a concomitant guest molecule. A notable early application of a host-guest gelation strategy was demonstrated by the Stoddard group, physically assembling a poly(acrylic acid) network through cyclodextrin/azobenzene interaction,66 whereupon the trans-azobenzene isomer – but not the UV-light generated cis form – sets into the hydrophobic cyclodextrin cavitand. The Burdick group extensively characterized hyaluronic acid (HA)-based networks physically crosslinked through a cyclodextrin host and an adamantane guest (Fig. 4ab).67 Variation in starting macromer concentration, chemical modifications to adamantane, as well as the host-to-guest molar ratio, enabled broad macroscopic tunability including erosion rate, shape memory, and gel stiffness. The group also exploited the effects of adamantane-cyclodextrin complexation on the affinity of HA towards encapsulated small-molecules, enabling the tunable and sustained release of model small-molecule drugs.68

Figure 4. Assembly of Non-Covalently Linked Hydrogel Networks through Host-Guest Chemistry and Hydrophobic-Hydrophobic Interactions.

(A) Host-guest chemistries enable the formation of physically and reversibly crosslinked hydrogels.

(B) Demonstration of self-healing properties of a host-guest crosslinked hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel. White and red regions represent cyclic deformation at 0.5% and 250%, respectively. Storage and loss modulus are recovered after each cycle. Reproduced with permission from Rodell et al.56 Copyright 2013, The American Chemical Society.

(C) Gel fragments formed by hydrophobic association undergo physical grafting when placed in direct contact. Reproduced with permission from Tuncaboylu et al.62 Copyright 2011, The American Chemical Society.

Beyond cyclodextrin host-based physical networks, a newer generation of non-covalent gels exploits curcubit[n]uril (CB[n]) as host. While not yet as widespread as cyclodextrins in pharmaceutical formulations,69 CB[n] hosts offer wider tunability and high affinities towards specific guest molecules, wherein binding usually occurs at or near the diffusion limit.70 The Webber group extensively characterized CB[7] host-based PEG hydrogel formulations, where the expanded host-guest affinity range afforded orders-of-magnitude changes in macroscopic properties (e.g., stress relaxation, solute release).71 These elevated affinities have made possible the use of supramolecular chemical methods of hydrogel assembly to “home in” on a target location within the body to deliver a therapeutic payload. The Webber lab has successfully demonstrated that, provided spatial localization of a host-modified hydrogel in a specific tissue, intravenously delivered guest-functionalized therapeutics will preferentially accumulate at the host site and yield site-specific drug targeting.72

Hydrogels can also be physically assembled through hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions. For example, the Okay group demonstrated the assembly of physically tough, highly stretchable, and self-healing hydrogels through copolymerization of large hydrophobic monomers (i.e., stearyl methacrylate, dodocyl acrylate) with a hydrophilic acrylamide monomer in a micellar solution of sodium dodecyl sulfate with sodium chloride (Fig. 4cd).73 While the conditions necessary for network assembly (e.g., required surfactant, macromer interface hydrophobicity) are not the most suitable for bio-focused applications, the study highlighted the promise of tuning and optimizing hydrophobic-hydrophobic associations to control resultant macroscopic properties of physically crosslinked hydrogels. Specifically, alkyl side chain length on the hydrophobic monomer and surfactant concentration were both found to crucially impact self-healing efficiency.74

Trends in non-covalent assembly schemes closely mirror those observed in chemical crosslinking methodologies, whereupon newer systems with increased breadth of tunability and applicability are continuously being developed.

2.1.2.2. Protein-Based

Protein-enabled chemistries permitting non-covalent gelation are numerous and well-characterized compared to their covalent counterparts. Many interactions proceed through biorecognition, wherein complementary polypeptide sequences recognize and assemble into a thermodynamically favorable structure that yields a physically stabilized network (Fig. 5a).

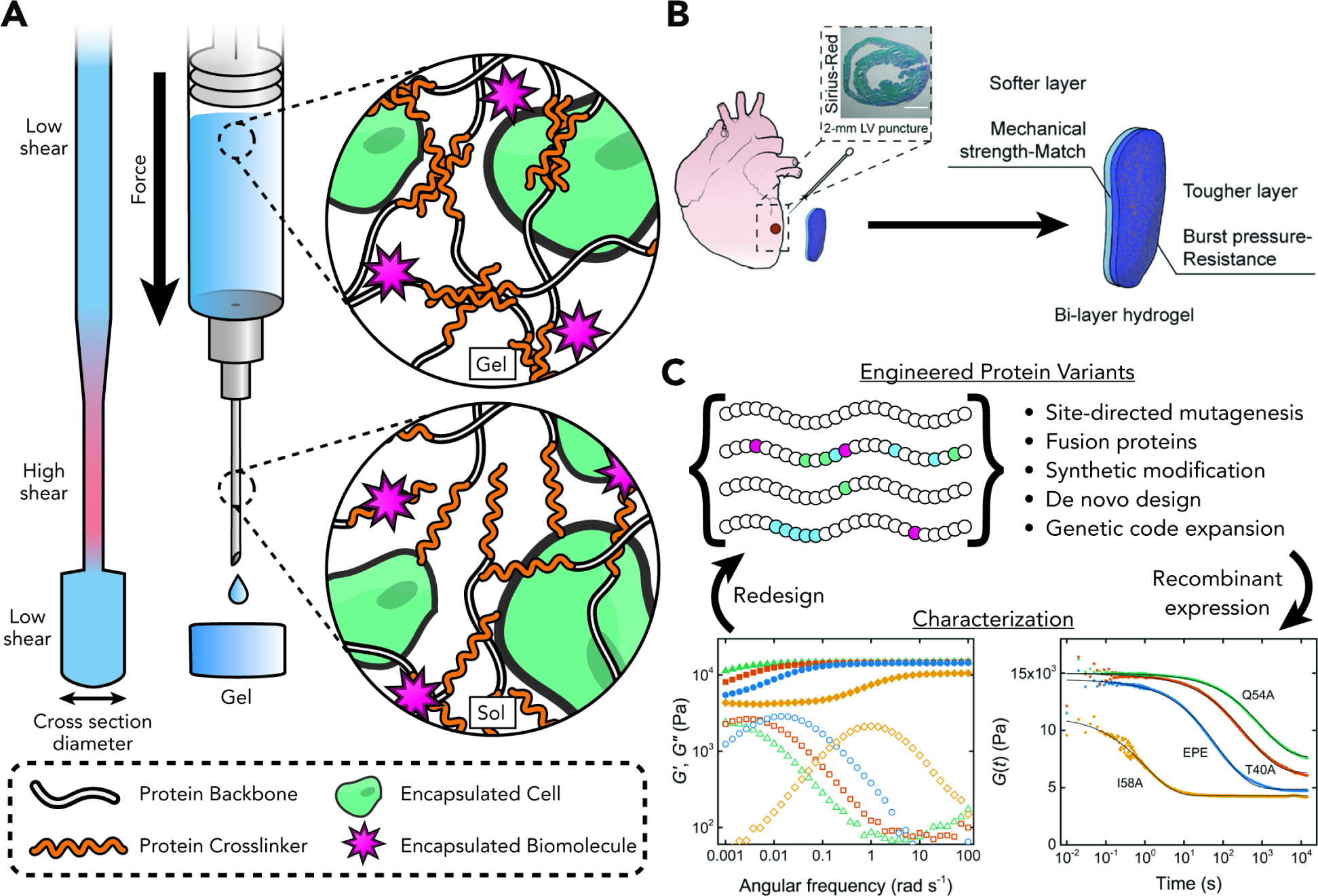

Figure 5. Injectable and Printable Recombinant Protein Hydrogels.

(A) Shear-thinning behavior of the physical network and superior biocompatibility of many recombinant protein-based hydrogels make them attractive targets for injectable therapies and extrusion-based bioprinting applications. As these materials are pushed through narrow passages, increased shear stress cause reversible liquefication, carrying along any cellular or biochemical cargo.

(B) A burst-resistant bi-layer patch uses two engineered variants of a shear-thinning leucine zipper-based hydrogel. The inner layer imitates the mechanical properties of softer native heart tissue, while the outer layer provides structural stability. Burst resistance of the was modulated by recombinant introduction of mussel foot protein domains Mefp3 and Mefp5 into the leucine zipper crosslinker, generating a chimeric set with an array of mechanical properties. Adapted with permission from Jiang et al.68 Copyright 2022 Wiley-VCH.

(C) Recombinant protein hydrogels uniquely allow iterative and high-throughput screening of physicochemical and biological properties through classic and next-generation protein engineering techniques. Plots adapted with permission from Dooling and Tirrell.67 Copyright 2016 The American Chemical Society.

Seminal work by the Tirrell and Kopeček groups established the coiled-coil motif as a widely used biorecognition module and crosslink of protein hydrogels75 and hybrid synthetic-protein networks.76 As their name implies, coiled-coils are constituted of two or more alpha-helix motifs that recognize and assemble into a supercoil maintained by hydrophobic interactions at the interface.77 Coiled-coil-based networks constitute most protein-enabled physical assembly chemistries, with coil domains from distinct protein origins deployed for the design of a variety of networks. This prompted a suite of investigations into the molecular engineering principles underpinning coiled-coil folding to elucidate how systematic primary sequence variation scales and translates into macroscopic changes at the network scale.78,79 Emblematic of the strategy, a recent study by the Zhong group makes use of a recombinantly produced coiled-coil crosslinked hydrogel to engineer bi-layer cardiac patches capable of supporting cardiomyocyte proliferation, fibrosis reduction, and increased blood pumping capacity in two separate murine disease models (Fig. 5b).80

Beyond coiled-coil biorecognition, the Heilshorn group introduced the “mixing-induced, two-component hydrogel” (MITCH) system for the creation of mechanically soft and fully recombinant scaffolds, originally to encapsulate, maintain, and differentiate neural stem cells.81 MITCH systems are physically assembled from a seven-repeat WW domain from C43 (C7) and a cognate nine-repeat proline-rich sequence (P9), with heterologously expressed C7 and P9 reacting with 1:1 stoichiometry from liquid precursors to form a stable gel. In contrast to other protein-based biorecognition chemistries that either may not structurally hold under native physiological conditions or may cross-react with endogenous epitopes present on cell surfaces, the MITCH system deploys two sequences that are normally absent from the extracellular matrix. In spite of their simplicity – containing both a tryptophan rich WW sequence and a cognate proline peptide sequence – the two components assemble with good selectivity to enable gelation in the presence of living cells. Further molecular- and sequence-level characterization and understanding of this system82 led to expanded uses in the stem cell culture niche, including delivery of adipocyte-derived stem cells83 and as a gel-phase ink for bioprinting.84

The Burdick lab pioneered a hybrid synthetic protein-based “Dock-and-Lock” (DnL) hydrogel consisting of two parts: 1) the RIIa subunit of cAMP-dependent kinase A, engineered heterologously as a telechelic protein (recombinant docking and dimerization domain, or rDDD), and 2) the anchoring domain of A-kinase anchoring protein (AD), achieved via solid-phase peptide synthesis and end-functionalized on a star-PEG macromer.85 Upon mixing, the multivalent AD domains “lock” into the protein dimerization “dock”. The resultant physical crosslinks that form enable the construction of a self-healing, shear-thinning, and ultimately injectable construct. In a subsequent report, this system was used successfully as an injectable drug delivery vehicle for interleukin-10 to treat obstructive neuropathy in a mouse model.86

The Kiick group harnessed the heparin-binding capability of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) proteins to non-covalently synthesize hydrogels.87 Specifically, multi-arm PEG macromers end-functionalized with heparin motifs formed hydrogels when mixed with VEGF proteins. These networks only eroded when the VEGF protein was pulled down by a presented VEGF receptor. While there have not been many examples following up on this strategy, it does highlight the potential promise of protein-polysaccharide interactions (or other forms of molecular biorecognition) in the design of therapeutically relevant hydrogels, particularly in microenvironments with a rich set of different signaling factors present.

Physical networks stabilized through protein-protein interactions hold benefit for the encapsulation and maintenance of cells given their biocompatibility. Their mechanics also result in desirable properties such as self-healing and injectability. An often-underappreciated aspect, however, is their direct amenability to systematic interrogation and evolution through sequence optimization (Fig. 5c). While previous efforts have mainly focused on site-directed mutagenesis – which has admittedly resulted in powerful gains in performance – we expect the field to be energized by the emergence and widespread adoption of de novo protein design59 and genetic code expansion.88 The former approach can generate large numbers of possible sequences to be tested for expression yields and bioactivity, and the latter can move outside of a purely biochemical space to access added degrees of functionality with a pristine regioselectivity beyond the capacity of stochastic modification. As these tools are codified, we predict many advances in biomaterial design and synthesis will become possible.

2.1.2.3. DNA-Based

DNA biopolymers are being increasingly employed to enable new frontiers in nanotechnology and materials science.89 Beyond its role as a genetic blueprint, DNA sequence encodes for rich structural and functional information driven through well-understood hydrogen-bond-driven base-pairing that is readily co-opted for exquisitely user-definable and controllable material development. The effects of sequence variation often scale up and result in macroscopic changes, allowing tunable mechanics and stimulus-responsiveness to be engineered through standard molecular biology methods. Moreover, the material stability of DNA in many biological contexts renders it highly useful as a crosslink in applications requiring long-term construct integrity. As a result, DNA-crosslinked gels have matured within less than two decades from an academic curiosity into an established area of biomaterial development.90

Early landmark examples have successfully exploited the governing dynamics of DNA-DNA interaction to create materials. In an early report, the Liu group synthesized networks from tri-functional Y DNA starting reactants via formation of intermolecular i-motifs,91 bypassing the need for an enzymatic trigger for the process, but leading to networks that were not stable at physiological conditions. Follow-up work established DNA hybridization of compatible “sticky” ends as a viable and potentially highly versatile approach for network synthesis.92 By mixing tri-functionalized Y DNA precursors and di-functionalized DNA linkers, the group engineered physical networks upon mixing endowed with enhanced stimulus-responsiveness and mechanical stability. The Willner group also successfully harnessed DNA self-assembly for the creation of pH-responsive DNA-based networks endowed with robust shape memory by supplementing the i-motifs with DNA duplex units generated through the usage of adenosine-rich sequences. Their networks underwent preprogrammed and reversible sol-gel transitions, whereby gelation would occur at a pH level of 5 and network dissociation at a level of 8.93

2.2. Triggered Hydrogel Formation

As described prior, the biomaterials field is benefitting from an expanding armamentarium of spontaneous assembly schemes for network creation. While important in a host of application spaces, these platforms often become inadequate when more nuanced control over hydrogel formation is necessary. For instance, hydrogel implants stand to benefit from spatiotemporal control over network formation. Building triggerability into gelation allows for these problems to be addressed and stands to buttress the immediate bench-to-bedside translatability of hydrogel biomaterials.94

Broadly, creating triggerable systems can proceed by two different methods: through the engineering of gating mechanisms (e.g., molecular “cages”) into reactions that otherwise would proceed spontaneously, or alternatively deploying a reaction scheme that a priori requires an exogenously delivered catalyst. These stratagems will be expounded upon in detail, and applications where they have proven a strong fit highlighted.

2.2.1. Triggered Gel Formation via Covalent Reaction

2.2.1.1. Synthetic Organic-Based

Engineering gating mechanisms is of broad interest to chemists, biologists, and material scientists given the potentially afforded spatial and/or temporal control over reaction initiation and extent.95 While click chemistries have proven essential in the engineering of new networks, reactions typically proceed rapidly upon mixing, hampering more nuanced use-cases where added control over the spatiotemporal aspects of gelation is essential. As such, efforts have been poured into taking otherwise-spontaneous step-growth chemistries and engineering gating mechanisms to control their initiation and/or progression through different triggers. Potential engineered stimuli are manifold and ultimately depend on the context of the application.

A common trigger is redox-based initiation, whereupon introduced oxidants or reductants can actuate hydrogel formation from redox-sensitive macromers.96 Thermally triggered gelation is also a viable strategy;97 while non-ideal for a number of biological applications involving temperature-intolerant mammalian cells, thermal actuation of gelation is useful for drug delivery platform creation. Lastly, pH can serve as a hydrogelation stimulus but is again typically precluded from applications involving live cell encapsulation.98 Though these stimuli can afford temporal control over network formation, as well as a route to uniformly modulate hydrogel properties post-synthesis, their ability to be controlled in space is limited.99 Moreover, their applicability is hampered when minimal cellular interference is required.

Photoreactions, which can spatiotemporally dictate gelation based on when/where light is shone onto a sample, offer exciting advances in targeted hydrogel formation. This partially explains the earlier widespread adoption of photoradical-mediated chain-growth systems (e.g., acrylates, methacrylates) (Fig. 2a).

While now less employed for cell encapsulation stemming from concerns over formation of cytotoxic free radicals100 and heterogeneous network structures,101 their reagent availability, ease-of-preparation and use, along with the control they afford in both triggering gelation and modifying formed networks makes photopolymerization a suitable candidate for the creation of permissive 3D scaffolds. Specifically, the combination of this chain-growth platform with a gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) starting material was highly synergistic, as it led to the creation of networks that were amenable to cellular encapsulation and maintenance102 as well as relatively easy photo-enabled post-synthetic modification. This galvanized reports generating hybrid-gelatin networks from methacrylated starting macromers, such gelatin-gellan gum, -PEG, -HA, and -silk fibroin.

Another popular photochemistry is the radical-mediated thiol-norbornene platform, initially developed by the Anseth group103 for the step-growth polymerization of PEG-based hydrogels. The reaction takes place between norbornene end-functionalized macromers and thiol-terminated crosslinkers. Requiring a lower initiator and active radical concentration than typical vinyl-based chain-growth chemistries, the reaction minimizes radical-induced damage to encapsulated cells or tethered biological moieties such as proteins. Additionally, it can proceed orders of magnitude faster than a chain-growth driven reaction and is not susceptible to oxygen inhibition. The platform was co-opted by multiple groups who applied it successfully to different base materials such as HA and gelatin.104

In looking to move photocrosslinking beyond radical-mediated chemistries, many labs have identified innovative ways to take step-growth chemistries previously considered uncontrollable and engineer photo-gating mechanisms into them, side-stepping radical-related cytotoxicity concerns. Towards this end, SPAAC was successfully rendered two- and three-photon activatable by the Popik and Bjerknes groups through inactivation of its strained alkyne group with a photocaging cyclopropenone group,105 paving the way for SPAAC hydrogel formation and biomolecule derivatization in deep-tissue. Upon photo-uncaging with near-infrared light, the alkyne group is liberated from its cyclopropenone “cage” to enable SPAAC reactivity. Oxime ligation was also successfully gated through photochemistry: our lab previously caged the alkoxyamine with a cytocompatible UV light-labile 2-(2-nitrophenyl)propyloxycarbonyl (NPPOC) group, such that the photo-liberated alkoxyamine could react with a cognate aldehyde and enable photocrosslinking for hydrogel formation and patterned biomolecule immobilization.106 The Barner-Kowollik group also recently red-shifted photocaged oxime ligation (λ = 625 nm) through generation of an aldehyde from a furan precursor molecule in the presence of a photosensitizer, enabling transdermal initiation of photocrosslinking through a 0.5 cm thick phantom mimic.107

Lastly, harnessing the [4+4]-photodimerization of anthracene has been shown by the Forsythe group to be a viable method to trigger network formation in the presence of cells.108 Eliminating the need for two distinct reagents typical to click-based platforms, the group end-functionalized PEG macromers with anthracene moieties and induced network gelation via cytocompatible visible light (λ = 400–500 nm) illumination. While earlier reports had demonstrated network formation using anthracene dimerization, requisite cytotoxic UV light were not suitable for cell encapsulation. To overcome this limitation, the group installed electron-rich substituents (e.g., triazole, benzyltriazole) to red-shift anthracene absorbance, resulting in a synthetically tractable (one form of macromer required rather than two) and cytocompatible network synthesis scheme.

Owing to the powerful synergies proffered by incorporating photoresponsiveness into bioorthogonal crosslinking chemistries, there has been a remarkable recent uptick in novel platforms that are phototriggerable.109,110 While not all of these have yet been deployed in the context of hydrogel assembly, they are uniquely suited for many applications.

2.2.1.2. Protein-Based

Beyond recognition and assembly of cognate pairs, protein-based platforms can act as enzymatic catalysts for the crosslinking of network precursors bearing the appropriate peptide substrate sequences. In fact, while thermal, redox, or light initiation triggers are well suited for certain applications, their usage can be sub-optimal when full bioorthogonality is desired. Given the prevalence of enzymes in all living organisms, their use as a highly bioorthogonal crosslinking reagent is potentially a powerful strategy (Table 2).

The Griffith lab first pioneered the use of transglutaminase to crosslink synthetic networks with macromers bearing appropriate recognition sequences.111 Transglutaminase, a Ca2+-dependent enzyme, catalyzes a transamidation reaction between the carboxamide side-chain of glutamine and the amine group found on lysines, releasing ammonia as a byproduct. This early work demonstrated network formation within a couple of hours from PEG macromers functionalized with either a glutamine residue or a lysine-phenylalanine dipeptide sequence. While highly promising, the relatively slow gelation placed limitations on encapsulation efficiency and uniformity. This strategy, however, laid the groundwork for a slew of follow-up research broadening the enzymatic toolset and optimize reaction parameters (e.g., substrate recognition, crosslinking kinetics). The Messersmith group, for instance, rationally designed substrates with high transglutaminase specificity to enable faster gel assembly kinetics.112 Subsequent work from different groups expanded the palette of available crosslinking enzymes with substrate recognition sequences of their own: these include horseradish peroxidase (HRP), phosphopantetheinyltransferase (PPTase), tyrosinase, lysyl oxidase, and sortase A.113 Highlighting the promise of bioorthogonal enzymatic crosslinking, the Hwang group recently employed a tyrosinase-mediated reaction to form protective nanofilm hydrogels from monophenol-modified glycol chitosan and HA in the presence of pancreatic beta cells to regulate blood glucose in a type 1 diabetes mouse model.114

Enzymatic crosslinking has also proven to be particularly well suited in the design and engineering of DNA-based hydrogel materials. In fact, routine enzymes in molecular biology applications have been co-opted to create hydrogels and other material structures from branched chain DNA. This was first exemplified by the Luo group, who harnessed T4 ligase to covalently assemble branched DNA structures (X, Y, and T motifs) into hydrogels.115 Combining enzymatic crosslinking with DNA as starting material has made possible the design of wholly novel topologies and network structures. An interesting example is the generation of hydrogels solely from pristine plasmid DNA rather than more complicated branched DNA structures. After digestion by appropriate restriction enzymes and generation of sticky ends, crosslinking through the action of a ligase leads to gelation, and in so doing solves many issues associated with material costs, synthetic intractability, and severe stoichiometric dependence.116 Building on enzymatic synthesis even further, the Walther group117 deployed a strategy whereby two antagonistic enzymes (i.e., urease, esterase) act in an autonomous feedback loop to regenerate a DNA hydrogel from sol to gel continuously, driven by ambient pH levels. This enabled biomaterial creation with a distinct lag-time and lifetime under closed system conditions.

2.2.1.3. DNA-Based

While the molecular engineering of DNA has enabled spontaneous gelation from nucleotide-modified polymeric macromers, relatively simple modification to the involved reaction motifs can turn DNA-enabled platforms into chemically triggerable systems (Fig. 6a). Emblematic of this approach is the use of aptamers, which are short nucleic acid sequences that are designed and engineered to bind to a particular target or family of targets. They can best be conceptualized as the nucleic acid-counterpart to protein-based antibodies, and their deployment as a material chemistry can confer several benefits. For instance, in the case of DNA aptamers, constructs can be readily synthesized through routine and economical solid-phase synthesis. Moreover, aptamers are often endowed with robust stability under different solution conditions, rendering them particularly useful as base material for material crosslinks and tethers for different cargos. Lastly, it is theoretically both straightforward and rapid to generate aptamers for a wide variety of targets spanning different biochemical classes through a now-optimized combinatorial method known as SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment).118 A foundational example of harnessing aptamers as a material chemistry for hydrogels was demonstrated by the Tan group, where starting polyacrylamide-based macromers were end-modified with linear strands of nucleic acids and yielded network formation upon introduction of an exogenous DNA molecule, termed LinkerAdap.119 While this was engineered to hybridize both strands of the starting macromers, it also includes an aptamer sequence for adenosine. Subsequently, introducing LinkerAdap into solution kickstarts a sol-gel transition, whereas adding adenosine will destabilize and degrade the network. This foundational example led to a flurry of downstream work that sought to apply DNA crosslink engineering for highly-sensitive therapeutic delivery and biosensing applications.120 For instance, the Wang group exploited the straightforward engineering of an anti-Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) and incorporated it into routinely synthesized PEG-DA hydrogel matrices.121 When gelation occurs in the presence of encapsulated PDGF, this platform can serve as a robust and synthetically tractable drug release strategy that uses affinity interactions rather than bulk material degradation to deliver its payload. Promisingly, the kinetics of the release can be dictated by controlling the degree of aptamer incorporation, wherein higher-affinity networks containing more anti-PDGF aptamers led to a slower release, while lower aptamer content led to faster release.

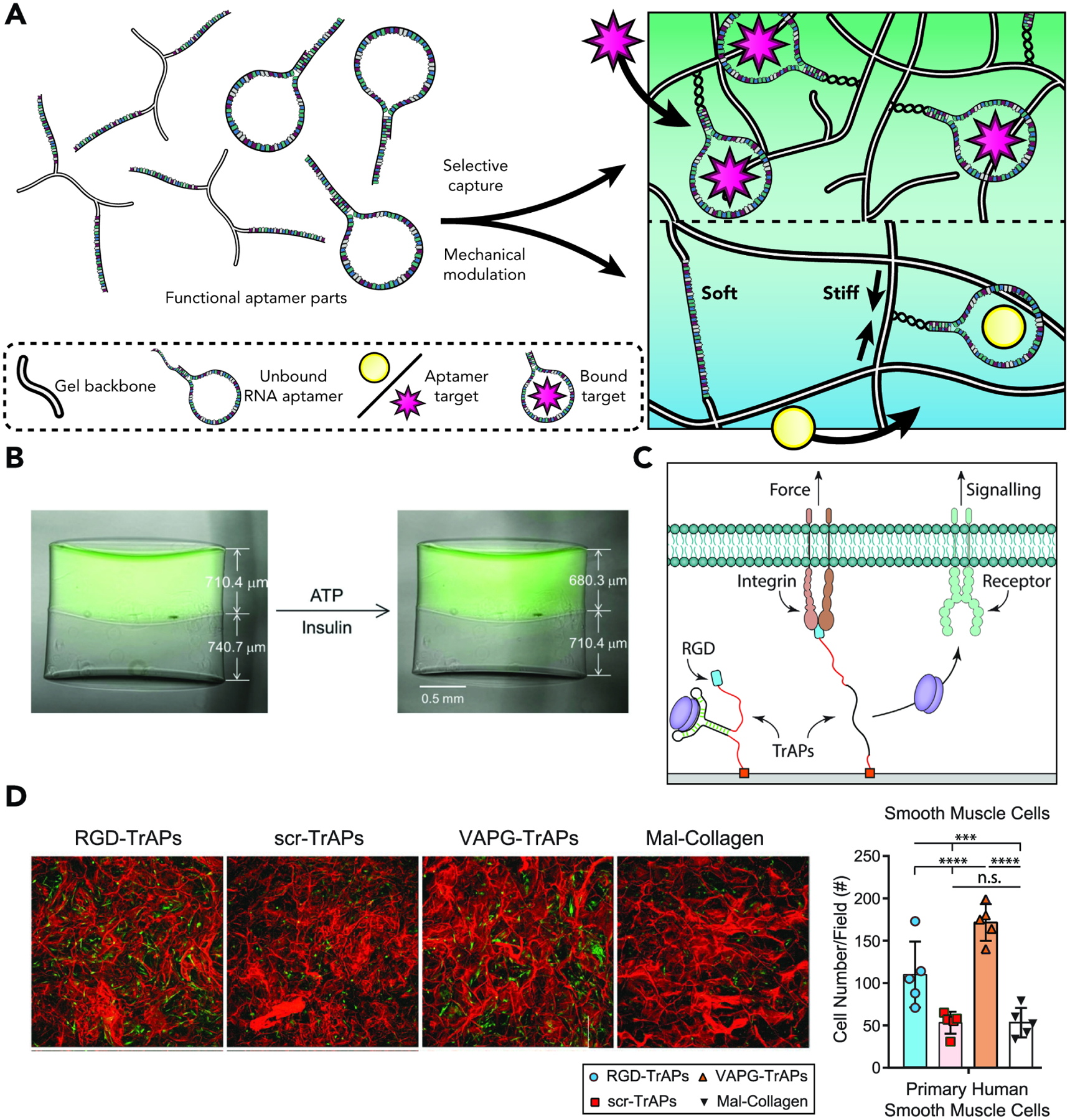

Figure 6: Engineering Dynamic Biomaterials through Aptamer Biology.

(A) When incorporated into a hydrogel backbone, aptamers in an extended initial state can lead to macroscopic-level changes in network mechanical properties through basic biorecognition and cognate target capture.

(B) Layered hydrogels are synthesized such that the top hydrogel (fluorescent green) is crosslinked through ATP-binding extended state aptamers and the bottom hydrogel is crosslinked through insulin-binding extended state aptamers. When exposed to the appropriate cognate molecule (ATP in the top and insulin in the bottom network), conformational changes in the aptamer crosslink lead to significant network volume decrease. Image reproduced with permission from Bae et al.122 Copyright 2018, Wiley-CVH.

(C) Aptamers can be engineered as force-mediated release systems. Traction Force Activated Payloads (TrAPs) are designed such that an aptamer bound to a target molecule is also linked to an RGD motif that recognizes force-responsive integrin motifs. Upon local mechanosensing or application of a force stimulus, unfolding of the aptamer leads to target molecule release.

(D) TrAPs enable selective activation of growth factors in 3D collagen scaffolds by Primary Human Smooth Muscle Cells. Extent of release and variation between different cell types is due to the relative expression of different adhesion receptors. Images for (C) and (D) reproduced with permission from Stejskalova et al.123 Copyright 2019, Wiley-CVH.

Aptamers can be deployed for applications that go beyond triggered payload release. One recent example of this was in fact demonstrated by the Murphy group;122 cDNA-bound (thus initially extended) aptamers were incorporated as network crosslinks in a synthetic gel backbone, and the target motif binding capacity of these was co-opted to effect substantial volume decreases in the hydrogel (Fig. 6b). They were able to show the applicability of this system both with ATP- and insulin-binding aptamers – up to a 40% volume decrease could be obtained in the case of the former and 15% in the case of the latter. This strategy is exciting as it can theoretically go much farther beyond these proofs-of-concept, limited only by the development of appropriate aptamer motifs that recognize relevant targets. Another powerful example by the Almquist lab showcased the deployment of aptamers as a force-responsive motif for the release of target payloads, rather than the usual scheme of “bind-to-release”.123 Specifically, the group developed “Traction Force Activated Payloads” – TrAPs – such that an aptamer motif was linked to both a cargo-of-interest (e.g., different growth factors) and an RGD motif that binds to cell membrane integrins. Deployment of an integrin-binding motif imparts force-responsiveness to the construct, such that local applied forces lead to payload release (Fig. 6cd). This biomimetic approach was inspired by the Large Latent Complex that natively controls the release of the transforming growth factor family. Excitingly, it bypasses the need for any exogenous trigger and relies on the nuances of cellular communication within the matrix to guide growth factor delivery.

2.2.2. Triggered Gel Formation via Non-Covalent Reaction

2.2.2.1. Synthetic Organic-Based

Early examples of triggerable gelation of physical networks have relied on small molecule introduction. For example, alginate polymers have historically lent themselves well to physical network assembly,124 as the introduction of divalent cation – most typically Ca2+ – leads to the formation of ionic bridges between different chains and subsequent gelation. However, given the crucial role calcium plays in biological signaling and cell-cell communication, this method falls short of creating truly bioorthogonal systems.

Beyond the now-classic calcium-alginate gels, recent reports outlining triggered assembly of physically crosslinked networks have been relatively few, albeit powerful given the dynamism that they can encode for and the relative ease with which desired downstream properties can be achieved. For example, the Rowan group demonstrated that the thermal gelation of polyisocyanopeptide chains can yield non-covalent network formation.125 Polyisocyanopeptides rely on a non-traditional beta-helical architecture stabilized by a supportive hydrogen-bonded network. Upon heating to 37 °C, the polymer fibers bundle into a stiff hydrogel, which can be further stress-stiffened – a highly desirable property that is almost always beyond the capacity of synthetic networks – in the presence of living cells in order to closely mimic cytoskeletal viscoelasticity over time. Moreover, the synthetic nature of these chains allows for the routine introduction of different epitopes for biochemical signal presentation, or alternatively modification of starting materials to enable pristine user control over downstream properties such as ultimate stiffness and stress relaxation. A more recent example by the Zhu and He groups outlines the use of the Hofmeister effect in order to trigger PVA network formation and modulate its properties.126 By varying ion type and concentration (thereby dictating whether salting-in or salting-out is occurring), the team induced hydrogelation through systematic control of PVA aggregation state, as well as encode for the hydrogel’s starting mechanics. Moreover, the ions only trigger gelation and do not play a role in maintaining network integrity, which means they can be dialyzed out post-assembly and do not stand to hamper applications that require subsequent interfacing with living cells.

2.2.2.2. Protein-Based

Most triggerable protein-enabled stratagems result in the formation of covalent networks, as seen when applying traditional enzyme-assembly methodologies or photocrosslinking of constituent residues. There are, however, some interesting examples of protein-based physical network assembly. An enzyme otherwise routinely used in molecular biology – phi29 polymerase – has been successfully applied for the physical assembly of DNA-based networks in a process termed rolling circle amplification (RCA).127 Best conceptualized as an isothermal alternative to polymerase chain reactions (PCRs), RCA avoids the damages caused to biomolecules induced by cyclical heating and cooling, which are otherwise necessary in the case of routine PCRs. It does so by starting with a small (25–35 nucleotides) circular strand of DNA as starting material for subsequent amplification. Moreover, given that RCAs can occur at physiological temperatures, they can be deployed in the presence of living systems. This makes them ideal for the non-covalent assembly of a variety of networks through DNA chain entanglement or sequence hybridizations.128,129

2.2.2.3. DNA-Based

While most DNA-crosslinked hydrogels have been limited to synthetic schemes that proceed spontaneously in a relatively uncontrollable manner, recent efforts have sought to gate or guide DNA self-assembly into macroscopic networks. Early attempts to trigger gelation were primarily focused on the introduction of Ag+ ions to form duplex bridges between DNA chains.130 However, other have sought to bypass the use of cytotoxic Ag+ triggers and engineer more sophisticated spatiotemporal control into the process. Towards that end, the Willner and Fan groups reported a DNA hydrogel synthesis that is triggered by the introduction of a DNA initiator in a method they termed a “clamped” hybridization chain reaction.131 As its name indicates, the stratagem relies on introducing a “clamp” into a DNA hybridization chain reaction, a process through which stable DNA fragments assemble only upon exposure to an initiator molecule. This kickstarts a series of amplification events, with ultimate amplicon size varying inversely with the size of the initiator used, in an isothermal and enzyme-free fashion.132 Classical hybridization chain reactions occur with two starting hairpin structures and an initiator molecule to kickstart successive assembly and amplification events. In a powerful example showcasing the promise of DNA molecular engineering, simple modification of one of the starting hairpins to incorporate a repeat palindromic sequence leads to a cyclical self-assembly scheme with intermediate three- and four-arm junctions to ultimately form a DNA hydrogel, with the small initiator linker operating as stimulus for the ensuing sol-gel transition. A subsequent report by the Li and Zuo labs harnessed this system for the capture of circulating tumor cells (Fig. 7).133 Keeping the main set-up of the system relatively unchanged, the groups engineered a bi-block initiator-aptamer molecule that recognizes specific receptors on tumor cell surfaces. Upon aptamer-receptor binding, the initiator strand is “revealed”, leading to hydrogelation in the presence of the circulating hairpin structures. This “cloaks” tumor cells with minimal damage, allowing for subsequent quantification and potential single-cell analysis.

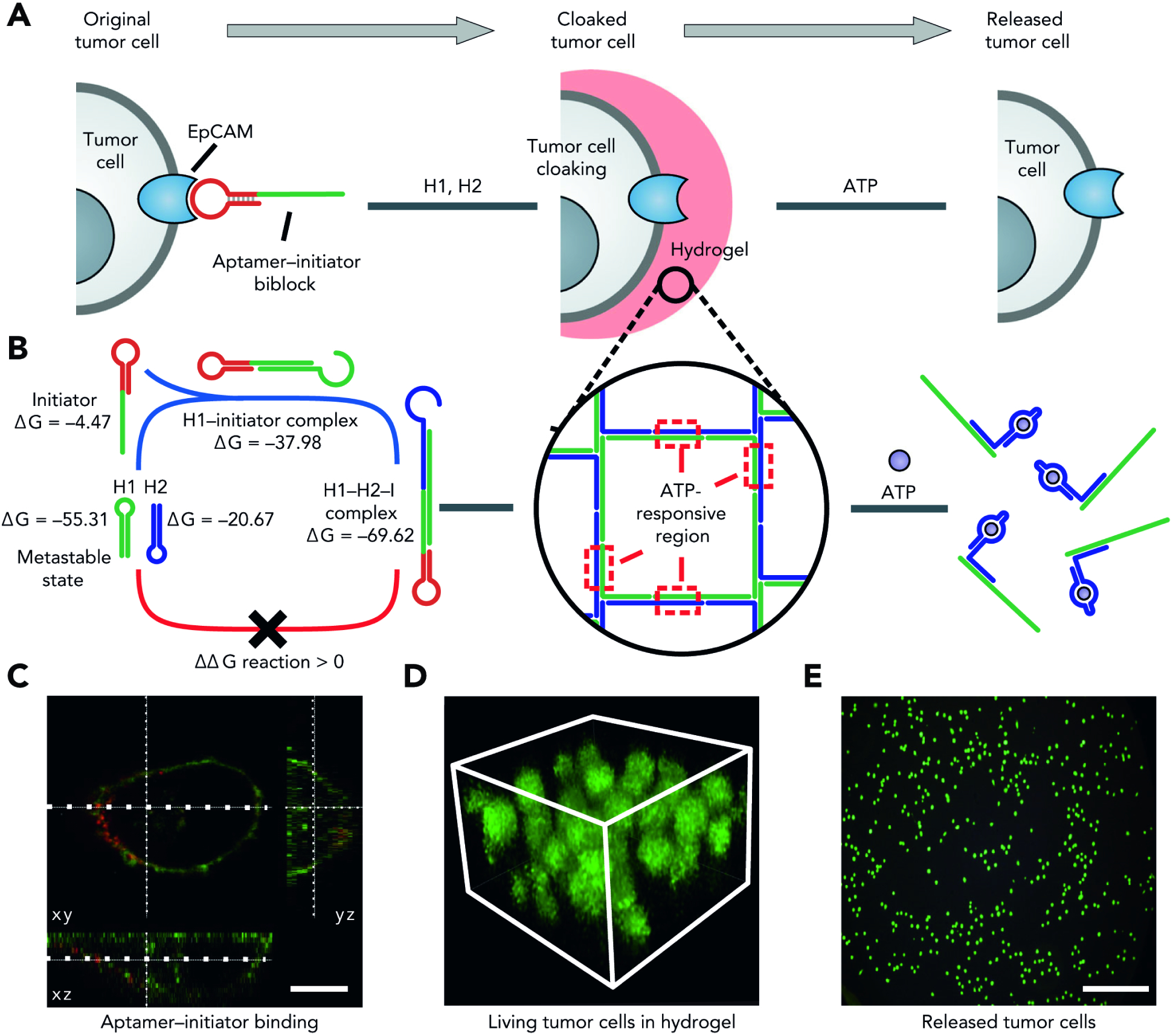

Figure 7. Aptamer-Enabled Targeting and Capture of Circulating Tumor Cells.

A) Aptamer-initiator bi-block constructs are designed to specifically bind to epithelial cell adhesion molecules (epCAMs) which are highly expressed on the membranes of tumor cells. Following binding, biblocks containing an initiator trigger the formation of an encapsulating DNA hydrogel. Post-encapsulation, ATP can be used to effect a conformational change within the ATP-responsive aptamer to destroy the gel, leading to tumor cell release.

B) H1 and H2 – which are step-look-structured – are in a metastable state because of the protective effects of long stems in their secondary structures. In the presence of the initiator, the hybridization reaction is triggered leading to hydrogel assembly.

C) Confocal microscopic imaging showing aptamer-initiator biblock binding to the cell surface membrane. Scale bar: 10 μm.

D) Multilayered cells can be found encapsulated within the DNA hydrogel when stained with FDA dyes. Stack height: 40 μm.

E) Cells disperse in solution upon ATP-triggered release. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Image reproduced with permission from Ye et al.118 Copyright 2020, Springer Nature.

3. Post-synthetic Modification of Hydrogel Biomaterials

As highlighted above, a growing toolbox of externally triggered and spontaneously proceeding reactions has birthed a wide method collection to fabricate hydrogel biomaterials. An equally as if not more important thrust focuses on developing chemical methodologies that post-synthetically modulate hydrogel properties. This would enable the field to go beyond encoding an initial set of biochemical and biomechanical parameters for a hydrogel matrix and to create constructs that can be customized on demand, potentially even in 4D. Engineering controllable dynamism into such systems would make possible longitudinal interrogation and/or control of biology, ideally in ways that capture all possible timescales of interest throughout space. In the ensuing section, we will survey different modalities that have been used to post-synthetically modify networks, with an eye towards rendering these chemistries more user-controllable.

3.1. Spontaneous Hydrogel Modification

Key to engineering evolvable networks is the identification and deployment of methodologies that modify hydrogels post-assembly.

3.1.1. Spontaneous Gel Modification via Covalent Reaction

3.1.1.1. Synthetic Organic-Based

Synthetic schemes offer different avenues for spontaneous modification post-assembly. A first category to that effect adopts off-stoichiometric ratios during the initial network formation step; by maintaining an excess of a particular reactant, biological epitopes functionalized with the appropriate handle could later be immobilized with temporal (and sometimes spatial) control. This presents a very straightforward approach that minimizes biomaterial design complexity; most often, a “mixed mode” approach can be adopted whereby one chemistry is used for network formation and another for post-synthetic modification. As one illustrative use-case, networks formed by a tetrazine-norbornene platform, for instance, can routinely be assembled such that excess norbornene groups are presented throughout the hydrogel. Biological epitopes harboring reactive thiols can then be introduced and photo-clicked in through an orthogonal thiol-ene chemistry.25 Another example along the same line of thought was presented by the Chen group; in this report, the base platform used for network assembly was DA chemistry, and excess maleimide was left unreacted for post-synthetic patterning.134 It is important to note that such “mixed mode” methods do not necessarily always hinge on stoichiometric manipulation of starting reactants, elegant as this approach may be. Orthogonal chemical handles can be introduced into the starting macromers such that they do not influence initial network synthesis but instead present avenues for later biochemical modification. An example of this method was presented by DeForest and Anseth;135 in that report, SPAAC was used to assemble PEG hydrogels with chemically orthogonal vinyl moieties incorporated into the starting materials and subsequently presented throughout the network. These reactive ene groups served as pendants for the later introduction and patterning of different classes of biological epitopes including small molecules and bioactive peptides through thiol-ene photochemistry. As can be seen from the examples above, owing to the diversity of chemical approaches developed for hydrogel synthesis and modification, there exist no shortage of platforms that can prove amenable to mixed approaches, where one chemistry is geared towards assembly and another tailored towards biochemical or biomechanical modification.

Another exciting development in evolvable hydrogel networks is the deployment of covalent-adaptable networks, which combine the mechanical integrity and stability of chemically crosslinked systems with the stress relaxation and enhanced viscoelasticity of physical assemblies.136–138 By occupying this intermediate niche between the two modes of crosslinking, biomaterial scientists have been able to tap into synergies unobtainable from either strategy alone and turn the reversibility of some of these base reactions (e.g., the previously touched upon DA and oxime ligation schemes) – typically thought to be a drastic weakness – into an exploitable property. Nevertheless, early iterations of these reconfigurable networks were not suited to the needs of the biomaterials science and engineering community; in fact, the landmark report outlining the use of DA chemistry (with furan and maleimide as starting macromers) for the generation of a so-called “re-mendable” material only did so at a transition temperature of 120°C,139 which was the only transition point at which the “adaptability” of the chemistry could be accessed. A similar early landmark paper deploying hydrazone chemistry for the generation of adaptable polyethylene oxide (PEO) matrices only showed network reconfiguration within reasonable timescales at a transition pH level of 4, well below the useful range for cell studies; the linkages would break at apparent pH levels less than 4, and would reform when above that cut-off.140 While powerful proofs-of-concept, rational changes had to be incorporated into the base chemistries used if this approach was to prove useful for pursuits in tissue engineering.141 Towards that end, the first report detailing the use of a covalent-adaptable network for the encapsulation and maintenance of a cell population was presented by the Anseth group, who did so through the deployment of a hydrazone transimination platform.142 A rapid screen of reactivities of two different aldehydes – one aliphatic and the other an arylaldehyde – with a methylhydrazine partner showed that both approaches could be viable candidates. In fact, both reaction pairs led to gelation and response profiles within reasonable timescales, and both approaches enabled the encapsulation of C2C12 myoblast cells. Since then, multiple dynamic covalent methodologies have proven useful in addition to the traditional DA143,144 and oxime ligation145 workhorses; among these chemistries are hydrazone,146 thioester exchange,147 hindered urea bond148, boronate transesterification,149 among others still. Interestingly, dynamic covalent chemistries can also be used in “mixed mode” approaches provided their reaction profiles and necessary solution conditions are compatible and amenable to multiplexability. One method to affect this was presented by the Anderson group, whose report used diol exchange of two kinetically distinct phenylboronic acid derivatives, 4-carboxyphenylboronic acid and o-aminomethylphenylboronic acid. In so doing, the authors were able to access highly nuanced mechanical and viscoelastic property ranges by mere tuning of the starting concentrations of either acid, and achieved response profiles beyond the reach of either acid alone.150 Another method is to deploy two dynamic platforms that are fully orthogonal; a recent example of this is provided by Fustin group, who in an interpenetrating network setting were able to combine Schiff base chemistry in one hydrogel and metal-ligand coordination in another.151

3.1.1.2. Protein-Based

The advent of orthogonal protein pairs has been highly enabling for the covalent post-synthetic modification of hydrogels constituted of different base materials. The fragment reconstitution-based toolkits mentioned previously have been deployed to great effect for network modulation across many synthetic platforms. To implement this strategy, the Li group photochemically crosslinked SpyCatcher-containing motifs into an underlying tandem elastomeric protein network. With these moieties in place, different “SpyTagged” fusions were swollen in to covalently decorate the gel with a host of proteins (i.e., fluorescent proteins, as well as cell-adhesive TNfn3 domain derived from type III fibronectin).152 The Sun group also harnessed this approach successfully to decorate mussel foot protein-3 (Mfp-3) hydrogels displaying SpyCatcher motifs, enabling post-gelation incorporation of SpyTagged protein.153 The West group took this blueprint further: by photochemically crosslinking different amounts of SpyTag within PEG-diacrylate hydrogels, they could specify the concentration of tethered SpyCatcher fusion proteins.154

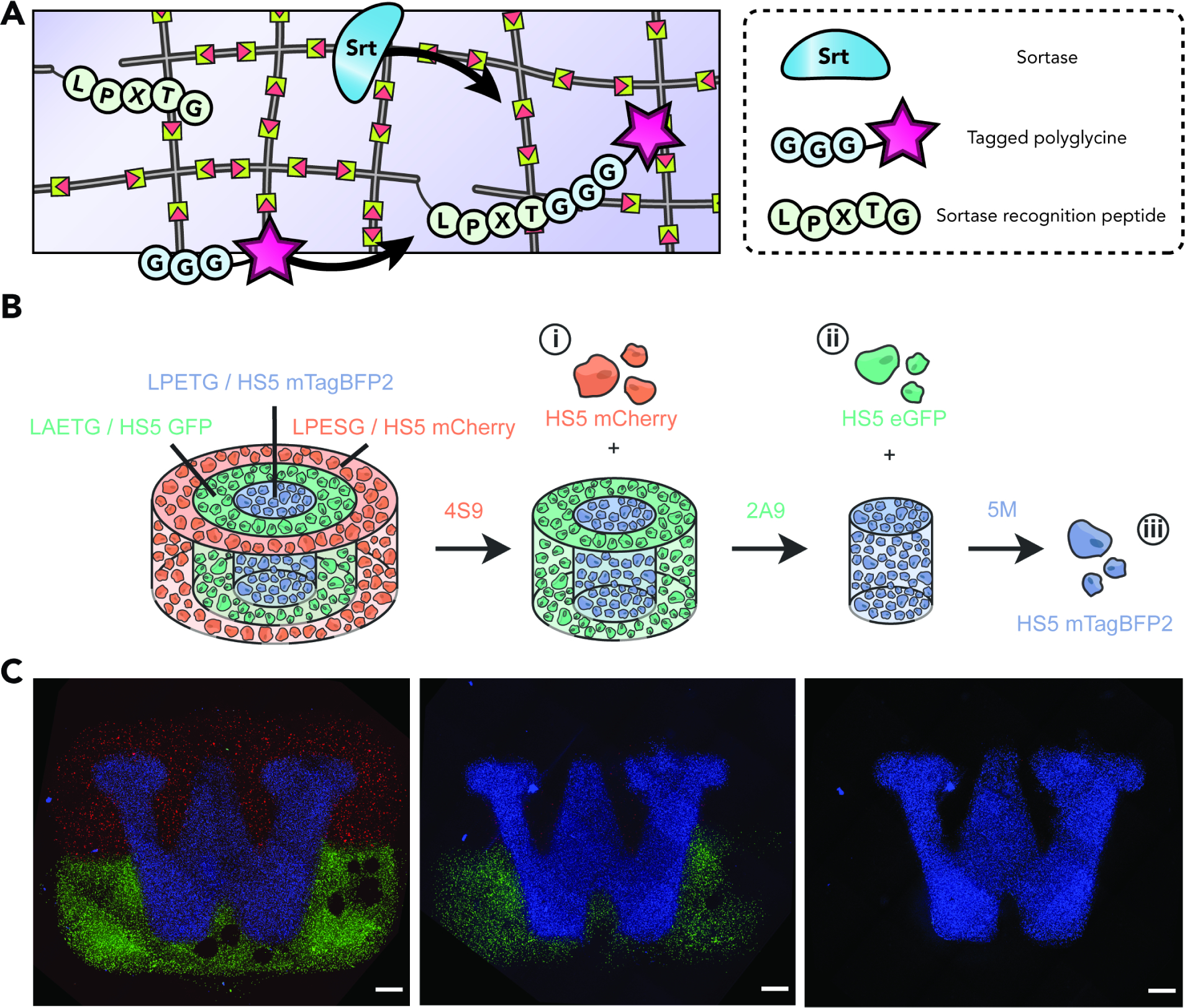

Beyond fragment reconstitution, enzymes can also be co-opted for the post-synthetic modification of networks, particularly in cases where bioorthogonality and maintenance of native bioactivity levels are essential. The Griffith lab pioneered the use of sortase-mediated transpeptidation to post-synthetically decorate hydrogel matrices. Specifically, a PEG hydrogel assembled through Michael-type chemistry was decorated with epidermal growth factor (EGF) via sortase (Fig. 7a).155 Beyond biochemical immobilization, their group also demonstrated sortase-enabled degradation of PEG networks, demonstrating gains in biocompatibility of the enzyme to the encapsulated cells when compared to more standard proteolytic gel degradation methods.156 In the same vein, the Lin group also employed sortase to control network crosslinking density.157 In order to do so, they exploited the inherent reversibility of sortase reactions to impart cyclical stiffening or unidirectional softening, based on the design of the constituent crosslinkers. Moreover, taking advantage of recently engineered sortases that were evolved to recognize orthogonal peptide substrates, our lab recently demonstrated the ability to spatially control degradation and cell recovery from multimaterial biomaterials158 (Fig. 8bc). Applications such as these highlight the extent to which genetic encodability can result in highly nuanced material responsiveness.

Figure 8. Sortase-mediated Gel Functionalization and Multimaterial Degradation.

(A) Sortase selectively ligates polyglycine-tagged cargo onto LPXTG-containing peptide sequences covalently bound to the polymer network.

(B) Harnessing evolved sortases’ ability to recognize orthogonal peptide motifs found within crosslinkers comprising different gel regions, staged material degradation and accompanying cellular release can be achieved; for example, with eSrtA(4S9), then eSrtA(2A9), then eSrtA-5M. Adapted with permission from Bretherton et al.125 Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH.

(C) Sequential sortase treatment enables user-defined control over cell-laden multimaterial degradation. Maximum intensity projections of the University of Washington logo, comprised of cells constitutively expressing one of three fluorescent proteins, are shown prior to degradation (left), following treatment with eSrtA(4S9) treatment (center), and following eSrtA(2A9) treatment (right). Scale bars = 1 mm. Reproduced with permission from Bretherton et al.125 Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH.

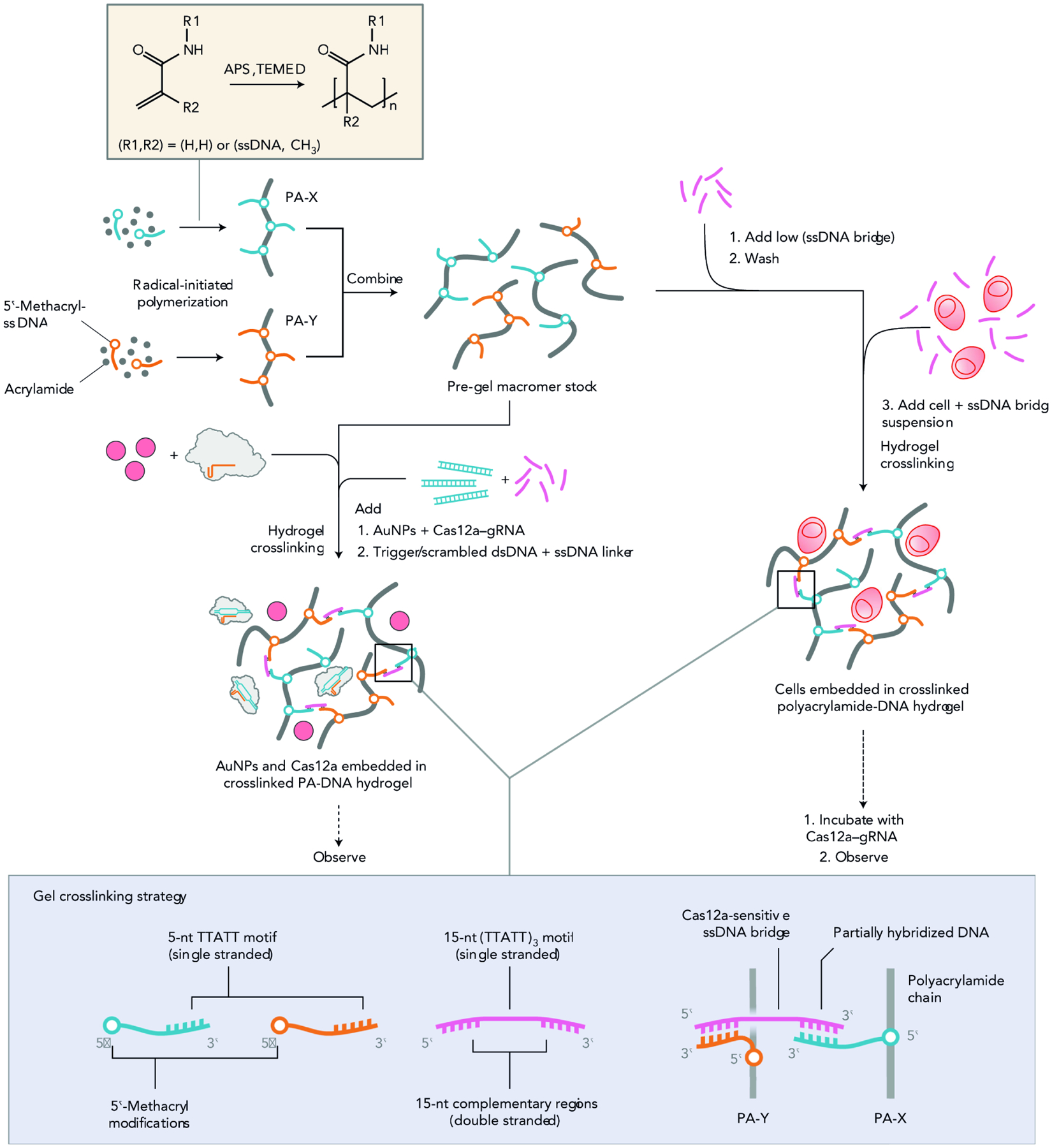

In a non-classical example showcasing protein-enabled network modification, the Collins group have engineered hydrogel networks with integrated nucleic acid crosslinks that cleave in response to the action of Cas12a nuclease proteins (Fig. 9).159,160 Based on the material design adopted, the group successfully demonstrated release of cargo tethered to the network through pendant DNA, bulk degradation of the network when crosslinked through appropriate DNA substrates, actuation of an electronic fuse, as well as co-opting the material for paper diagnostics endowed with remote signaling capacities. We expect recent advances in triggering CRISPR activity to further next-generation responsive materials development.

Figure 9. Design and Synthesis of Cas-Reponsive Hydrogel Networks.

Methacryl-functionalized DNA is incorporated into polyacrylamide chains (PA-X, PA-Y) during starting macromer polymerization. This enables different routes to gel actuation and response modes. In one example, shown on the left, the Cas12a–gRNA is added to the gel precursor with the nanoparticle cargo, before the addition of dsDNA cues and ssDNA crosslinker. In another example, shown on the right, cell encapsulation is triggered through the addition of a small amount of ssDNA bridge crosslinker to the macromers mixed in solution. This thickens the pre-gel solution and minimizes losses incurred during the washing step. More ssDNA linker is then added at the same time as the cells to fully crosslink the hydrogels. Finally, the experiment is initiated by exposing the gels to gRNA-complexed Cas12a and dsDNA. Additional details of the crosslinking strategy (bottom of the panel): the two ends of the DNA bridge hybridize with distinct ssDNA anchors incorporated into polyacrylamide macromers, while the central AT-rich portion remains single-stranded and sensitive to Cas12a collateral activity. Reproduced with permission from Gayet et al.127 Copyright 2020, Springer Nature.

3.1.2. Spontaneous Gel Modification via Non-Covalent Reaction

3.1.2.1. Synthetic Organic-Based

The earliest and arguably most robust example of a non-covalent method to confer modifiability into hydrogels is heparin, either chemically tethered via synthetic coupling, encapsulated, or included as a network crosslink.161 Heparin is a linear polysaccharide group that was initially deployed to reduce biomaterial-induced thrombogenesis following blood contact given its anticoagulant activity. However, it was soon discovered to preferentially bind to a wide host of growth factors,162 rendering it particularly useful for controlled the release of protein therapeutics and regenerative medicine applications.163,164 However, in spite of its relative simplicity, routine usage of heparin has been hampered by its broad binding capabilities; its biorecognition is not limited to a singular cognate partner. Instead, it recognizes a wide family of growth factors that harbor a heparin-binding motif, which would likely complicate its use in vivo.

Moving beyond the broad recognition capacity of chemically immobilized/encapsulated heparin would require more judicious design or identification of target-specific docking sites that can enable the stimulus-responsive and precise release of encapsulated drugs upon analyte sensing i.e. a more precise form of molecular biorecognition. An early example of this is the coumermycin-inducible release of drugs in loaded polyacrylamide hydrogels presented by the Weber group.165 In fact, the group chemically conjugated a bacterially produced Gyrase B protein subunit – which harbors a very strong affinity to coumermycin – to nitrolotriacetic acid-modified polyacrylamide via Ni2+ chelation. Introducing the coumarin-based antibiotic coumermycin leads to Gyrase B homodimerization, polymer crosslinking, and subsequent network assembly. Subsequent addition of the competitive antibiotic novobiocin, however, leads to dimer dissociation and resultant network degradation. This was used successfully for the encapsulation of a VEGF protein during encapsulation and controlled release, which could be tuned by varying the relative concentrations of the different parameters at play. Given the simplicity of the platform as well as its reliance on commonly used and FDA-approved antibiotics – rendering potential downstream translation all the more promising – the group built upon their strategy further by porting it into a more bioinert PEG-based network crosslinked through Michael-type chemistry,166 applying it for the release a Hepatitis B vaccine,167 and exploiting its amenability for pharmacological regulation to build a cell growth-supporting matrix.168,169

3.1.2.2. Protein-Based