Abstract

Cardiac arrest is the leading cause of death in the more economically developed countries. Ventricular tachycardia associated with myocardial infarct is a prominent cause of cardiac arrest. Ventricular arrhythmias occur in 3 phases of infarction: during the ischemic event, during the healing phase, and after the scar matures. Mechanisms of arrhythmias in these phases are distinct. This review focuses on arrhythmia mechanisms for ventricular tachycardia in mature myocardial scar. Available data have shown that post-infarct ventricular tachycardia is a reentrant arrhythmia occurring in circuits found in the surviving myocardial strands that traverse the scar. Electrical conduction follows a zigzag course through that area. Conduction velocity is impaired by decreased gap junction density and impaired myocyte excitability. Enhanced sympathetic tone decreases action potential duration and increases sarcoplasmic reticular calcium leak and triggered activity. These elements of the ventricular tachycardia mechanism are found diffusely throughout scar. A distinct myocyte repolarization pattern is unique to the ventricular tachycardia circuit, setting up conditions for classical reentry. Our understanding of ventricular tachycardia mechanisms continues to evolve as new data become available. The ultimate use of this information would be the development of novel diagnostics and therapeutics to reliably identify at-risk patients and prevent their ventricular arrhythmias.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the leading cause of death in more economically developed countries. The generally accepted definition of SCD, attributed to the World Health Organization, is sudden unexpected death either within 1 hour of symptom onset for witnessed events, or within 24 hours of having been observed alive and symptom-free for unwitnessed events. SCD incidence rates in the US have been estimated at 76 per 100,000 person-years.1 Similar levels have been reported in Europe and Australia, with slightly lower incidence reported for Asia.2 SCD deaths exceed those for all other individual diseases and account for more years of potential life lost than all individual conditions other than accidental deaths.1

In layperson or public discussions, these deaths are often called “heart attacks,” which generates public confusion because it is also the generally accepted lay term for acute myocardial infarction (MI). In reality, SCD more often occurs as a result of lethal ventricular arrhythmias that may be connected to ischemia and acute MI but just as frequently result from chronic ischemic heart disease.3,4 Reproducibly, over the last four decades, autopsy studies have shown that approximately 90% of witnessed SCD victims, when autopsied, have coronary artery disease, and one-half to two-thirds have evidence of prior MI with mature scar.2–6 In these patients, the sequence of events generally starts with the MI at some remote time point. The infarct heals, leaving an arrhythmogenic substrate where fibrotic scar intermingles with surviving myocyte bundles. Cardiac arrest occurs months or years later when a ventricular arrhythmia originating in this healed scar causes circulatory collapse and death. Ventricular arrhythmias during ischemia, infarct healing, and after scar stabilization are distinct.5 In this review, we focus on the arrhythmic substrate and mechanisms relevant to ventricular tachycardia (VT) occurring in chronic infarction after the MI scar has matured. For interest in the acute phase arrhythmias, during ischemia or infarction, readers are referred to reviews by Cascio et al. or Rubart et al.6,7 For a review of subacute phase arrhythmias, days after infarction, a recent review by Ciaccio covers data relevant to that mechanism.8

Time course of healing after MI.

Immediately after MI, cellular necrosis occurs over several hours, eliciting a robust inflammatory response. In humans and large mammals, acute inflammation peaks over 3–10 days and disappears by 4–5 weeks post-infarction.9–12 Inflammatory cell signaling causes fibroblast recruitment, myofibroblast conversion, and fibrotic matrix formation. Fibrosis onset is 3–10 days after the onset of infarction, and the fibrotic scar matures over 4–5 weeks.9–12 In the mature scar, low levels of chronic inflammation and fibrotic matrix remodeling persist indefinitely.9–12

Based on these events, the post-MI substrate can be characterized by 3 phases: an acute phase, minutes to hours after MI, when the dead and dying myocytes are structurally intact, and the reparative responses are starting; a subacute phase, hours to days post-MI, when the inflammatory and reparative responses are fully operational but fibrosis is not a prominent part of the substrate, and a chronic or mature phase, beyond one month, when the substrate is generally stable.9–12

The time course of infarct healing is reflected both in the etiology of sudden death and incident arrhythmias. In the subacute phase, sudden death is more often from recurrent ischemia or myocardial rupture.3 The arrhythmia substrate is evolving, and documented arrhythmia mechanisms include reentry, automaticity, and triggered activity.13 After scar maturation, arrhythmias are the primary cause of sudden death,3 and these arrhythmias are dominantly reentrant in nature.14–17

Basic Arrhythmia Mechanisms.

Macroscopic arrhythmia mechanisms include abnormal automaticity, triggered activity, and reentry. Abnormal automaticity occurs in myocytes that normally would be electrically quiescent and hold a stable resting membrane potential until activated by neighboring cells. With abnormal automaticity, those cells have progressive loss of resting potential until the activation threshold of an inward current is reached. The inward current generally comes from activation of l-type calcium channels because the cardiac sodium channel is inactivated during slow depolarization of the membrane voltage. Activation of the inward current generates an action potential (AP). Repetition of this process causes a sustained arrhythmia.

Triggered activity starts with either an early or delayed afterdepolarization. Early afterdepolarizations occur during the AP when reactivation of sodium or calcium channels overwhelms repolarization and generates a secondary depolarization within the AP. Early afterdepolarizations generally occur with AP prolongation. They can also occur in normal or shortened APs if sarcoplasmic reticular calcium release is sufficiently robust to activate inward current through the sodium-calcium exchanger.18 Delayed afterdepolarizations occur after completion of repolarization. Abnormal calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum during diastole activates the sodium-calcium exchanger, generating an inward current when calcium is extruded from the cell. In the case of either early or delayed afterdepolarizations, a triggered beat occurs if the depolarization is of sufficient force to activate depolarizing sodium or calcium channels to generate an AP. For more in-depth review of these mechanisms, please see a recent review by Antzelevitch.19

Automaticity and triggered activity are achievable in individual cells, but reentry exists within a mass of myocardial tissue. Normal electrical activation of the myocardium proceeds in an orderly, unidirectional fashion from the excitation source through the myocardial mass until all tissue is activated. The time delay from activation to repolarization in the cardiac AP creates a zone of refractory tissue behind the activation wavefront, preventing the impulse from doubling back on itself. Intracardiac reentry becomes possible if a portion of the myocardium is initially shielded from the activation wavefront and then becomes excitable so that the impulse has the possibility of doubling back through this region and setting up a circuit of continuous cardiac activation. For reentry to continue, each portion of the circuit must recover excitability before the activation wavefront reaches that area. Thus, sustaining a reentrant circuit requires a balanced interplay between the conduction velocity (CV) and the refractory period, which is more likely to occur in electrically and structurally heterogeneous tissue. The mechanism of post-infarct VT under most circumstances is considered reentry based on reliable initiation, termination, resetting, entrainment with programmed stimulation, and prevention with ablation of the circuit.20–25

Initiation of an arrhythmia with programmed stimulation (a pacing protocol that includes initial steady-state pacing followed by a series of premature beats) is generally considered specific for reentry as an extrastimulus-paced beat initiates reentry by entering the circuit at a point where one limb is excitable, and the other limb is refractory.26 Similarly, extrastimulus pacing is able to terminate reentry arrhythmias by activating tissue ahead of the reentry wavefront, rendering it unexcitable and thus terminating the tachycardia.27 Wellens et al. applied these principles in 1972 to conclude that post-infarct VT was a reentrant arrhythmia. They described the results of five patients, four of whom had evidence of prior myocardial infarction, where VT was reliably induced with premature extrastimuli following a steady state ventricular pacing drive train.28 Other investigators questioned the validity of reentry as the mechanism for VT. Denes and colleagues in 1976 published their findings on seventeen patients with recurrent VT and determined VT could not be reliably initiated with burst pacing or extrastimuli pacing, which they concluded suggested a mechanism other than reentry.29 Further clouding the picture was evidence that triggered arrhythmias could also be induced with programmed stimulation,30,31 suggesting that initiating VT with programmed stimulation was insufficient proof of reentry as the mechanism for post-infarct VT. Josephson et al. in 1978 provided further support that reentry is the primary mechanism for VT in a human heart.32 In their report of three patients with structural heart disease and recurrent sustained VT, they showed the following: (1) extrastimuli pacing induced monomorphic VT, (2) endocardial mapping during VT identified a physical circuit with continuous electrical activation that spanned the VT cycle length, (3) pacing into the identified circuit altered the tachycardia, and (4) VT termination coincided with the cessation of the continuous activity through the circuit. Proof of reentry as a cause of post-infarct VT was established in reports by Gallagher, Guiraudon, Josephson, and others showing that surgical removal of the mapped VT circuit eliminated the arrhythmia.33–35 More recent work has refined this concept by showing that ablation of a critical isthmus within the circuit can also eliminate VT (Figure 1).36 Although these data do not rule out abnormal automaticity or triggered activity as mechanisms of post-infarct VT initiation and occasionally of VT continuation, they do establish reentry within specific electrical circuits as the arrhythmia mechanism for the majority of VTs occurring in healed infarct scars.

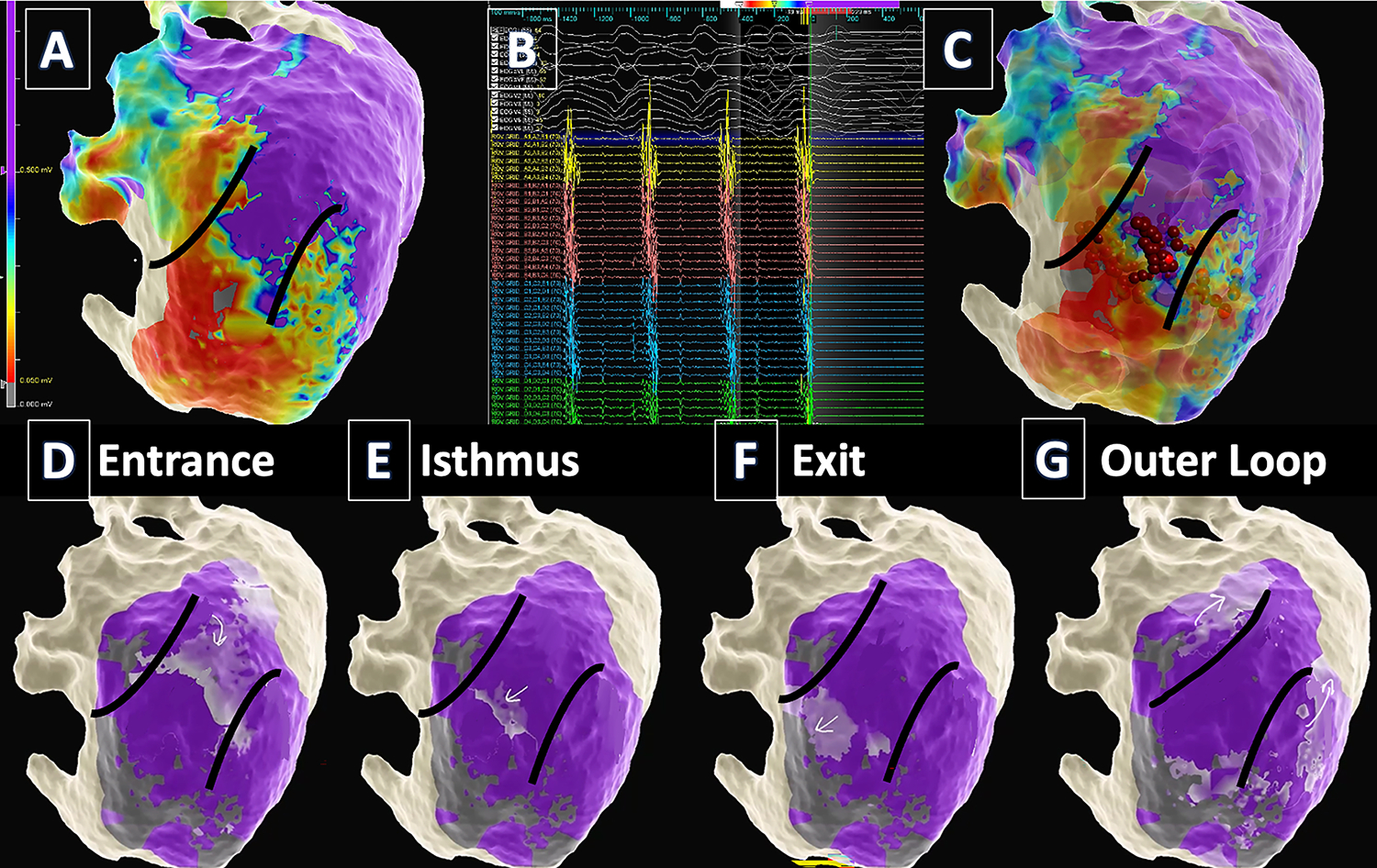

Figure 1:

VT mapping and ablation in a patient with prior anterior MI. (TOP) A. Epicardial voltage mapping identified a large anteroseptal scar extending from the base to apex. Myocardium with normal bipolar voltage is purple. Dense scar is red and borderzone is blue-yellow-orange. B. VT critical isthmus was identified when contact of the catheter with myocardium “bump” terminated the VT. C. Ablation (red dots) in the isthmus rendered the patient non-inducible. (BOTTOM) Activation mapping during VT identified a “figure of 8” circuit with entrance (D), isthmus (E), exit (F), and outer loop (G) on the epicardial surface. The lighter purple region marked with the arrows is the activation wavefront. Darker purple is live myocardium, and gray is dense scar. Arrows denote the circuit.

Abnormal automaticity and triggered activity from surviving subendocardial Purkinje fibers may play an important role in acute myocardial infarction. Prior work in 24-hour infarct models in dogs supports both triggered activity from DAD,37 but also automaticity based on the inability to suppress the inducible VT with overdrive pacing nor accelerate the VT with faster drive trains.38 Metabolic acidosis and ATP depletion result in substantial electrophysiologic changes, including depolarization of the resting membrane potential and AP duration (APD) shortening. In addition, Ca2+ overload in the Purkinje fibers leads to triggered activity, and automaticity manifests secondary to myocardial stretch. However, even in the acute MI setting, re-entry plays a prominent role secondary to heterogeneous conduction and repolarization of myocardial tissue in the border of infarct and non-infarcted/ischemic territory.5,39,40

While case reports have detailed triggered activity as the mechanisms for VT in patients with a chronic MI,41 as determined by reproducible initiation with atrial and ventricular stimulation with a long pause followed by a short coupling interval between subsequent beats, computational modeling and invasive electrophysiologic studies in humans with chronic MI consistently support reentry as the primary mechanisms for the maintenance of VT.42

Anatomy of the VT circuit.

The physical location of post-infarct VT circuits was initially investigated in VT surgeries that reported VT elimination after aneurysm and/or endocardial scar resection. These results established that a critical part of the circuit was in either the aneurysm or surrounding endocardial tissue. Later endocardial mapping and VT ablation procedures localized VT circuits to the infarct scar or the border area where scar is interspersed with surviving myocardial tissue, commonly referred to as the borderzone.15,45 Elimination of VT by limited scope ablation (as few as one ablation lesion can in some circumstances eliminate all VT from individual patients) at the mapped sites confirmed that VT exists in identifiable circuits that are finite in number and confined in space.14

Fenoglio compared histology in tissues harvested from mapped VT sites and non-VT infarct scar tissues.46 They evaluated patients with medically refractory VT and prior MI undergoing VT ablation surgery. The surgical procedure included VT induction, activation mapping, resection of tissues, and confirmation of success with repeated attempts at VT induction. They found no differences in the pattern or content of fibrosis or appearance of surviving myocytes when comparing VT sites to infarcted areas that were not associated with VT. In both VT and non-VT scar tissues, they found extensive fibrosis with surviving myocyte bundles randomly distributed throughout the scar tissue. Myocyte bundles were present in all resected tissues; both thick (>100 μm) and thin (<100 μm) bundles were observed, and they appeared randomly distributed throughout the tissues. Myocytes with essentially normal appearance were observed, as were myocytes with degenerative changes, vacuolations, and large inclusions. There were no measurable differences in histological characteristics comparing tissues from patients with successful and unsuccessful VT ablation surgeries or between VT and remote sites within the same patient. Bolick et al. later confirmed that surviving myocyte bundles occur diffusely throughout scar in both VT and arrhythmia-free patients.47

In a series of publications, de Bakker et al. provided a more detailed assessment of the anatomical features of the VT circuit.16,17 In an initial study of patients with drug-refractory VT, chronic ischemic heart disease, and prior MI, they used activation mapping with a 64-electrode basket to locate the VT circuits.16 Distance between electrodes was 1.2 cm, giving an endocardial surface area between 4 adjacent electrodes of 1.4 cm2. Either earliest systolic activation or continuous electrical activation through diastole was considered evidence of VT circuit location. In total, they mapped 139 VTs and found that 105 had focal activation within the space of 4 adjacent electrodes. The behavior of these VTs led the authors to conclude that they were micro-reentry within that small volume of tissue. In addition, they mapped 31 VTs with circuits that extended beyond four adjacent electrodes but were still contained within one segment of the borderzone. They called these localized reentrant VTs. They only found 3 VTs that were macro-reentrant, with activation around the infarct scar. In a second study, they reported on 47 VTs and found that approximately half were focal and the remainder were macro-reentrant.48 In addition to activation mapping, the latter paper also used entrainment pacing to verify reentry in the focal VTs. In 2 additional studies, de Bakker et al. evaluated tissues extracted from either mapped VT circuit locations17 or infarcted papillary muscles taken from hearts harvested at transplantation.49 In both VT circuits and papillary muscles (not obviously associated with VT), they consistently found surviving strands of myocardium interspersed with fibrotic tissue similar to the results reported by Fenoglio. In a meticulous analysis of histology sections, they were able to trace through connections of surviving myocytes to construct hypothetical VT circuits with what they described as a “zigzag route of activation” through branching and merging myocyte bundles separated by fibrotic tissue. Comparing their reports of patients with and without VT, it was notable that these zigzag circuits could be found in all infarcted tissues, not just verified VT circuits.

Pogwizd et al. used activation mapping to characterize VTs in 10 patients.15 They used needle plunge electrodes for 3D characterization of the myocardial tissue. Their electrode spacing was approximately 500 μm. They found five macro-reentrant and five focal VTs. All of the macro-reentrant VTs involved mid-myocardial pathways. They did not further characterize the mechanism of the focal tachycardias to distinguish micro-reentry from other mechanisms. On histological analysis, they found that each patient had a solid core of fibrosis that was a barrier to conduction with a complex three-dimensional pattern of fibrosis intermingling with surviving myocytes that extended out from the core for a variable distance (typically less than 1 cm, but up to 3 cm). The exit site of macro-reentrant VT typically occurred in this peri-infarct or borderzone region. Myocytes in this region were sometimes noted to be hypertrophic, and other times were unremarkable in morphology. In particular, the sites of 2 focal VTs were available for analysis, and both contained thickened subendocardial tissue interspersed with fibrosis, small endocardial muscle bundles, and Purkinje fibers. These histological findings were not unique to the VT sites and were noted in other resected tissues from the same patients.

More recent work by Tung et al. used simultaneous endocardial and epicardial activation mapping to assess activation patterns in 44 post-infarct VTs.50 Like Pogwizd’s report, Tung noted that almost all mapped VT circuits had a mid-myocardial component, and only three were truly contained to one surface (2 endocardial, 1 epicardial).

A weakness of these data is the limited proof of VT circuit location. Other than the de Bakker work in Langendorff-perfused human hearts extracted at the time of transplantation, the other human data used activation mapping as the primary proof of VT circuit location. Some but not all confirmed that a critical element of the VT circuit was in the extracted tissues by noting the loss of inducibility after resection or ablation. Entrainment pacing was rarely used to verify circuit location. This limited proof of VT circuit location was often necessary to maintain patient safety, but it needs to be kept in mind when evaluating these studies. Taken as a whole, these data support the concept of a physical VT circuit encompassed of surviving strands of myocytes in a fibrous scar matrix. The connections between cells are such that the circuit follows a zigzag course through the scar. Comparison of several histological parameters between VT circuits and scar unassociated with VT has consistently failed to identify any distinct histological signature to specifically identify the VT circuits.

Electrical conduction in the VT circuit and throughout healed scar.

Factors relevant to electrical conduction in the heart include cellular excitability and connectivity. Excitability is predominately determined by the status of the cardiac sodium channels. Sodium current density can be affected by sodium channel expression and localization, numerous factors that affect channel gating, and the resting membrane potential (RMP) that affects channel availability. Cellular connectivity is affected by connexin expression, phosphorylation status and localization, physical disruptions from fibrosis, and three-dimensional conduction issues like source-sink mismatch where surviving myocardial strands in the borderzone connect to the greater myocardial mass.51

Critical factors in assessing electrical conduction within VT circuits include precise identification of the circuit and consideration of the three-dimensional nature of cardiac conduction. As noted above, the majority of mapped and measured VT circuits are small relative to the overall size of the scar. Both de Bakker et al. and Pogwizd et al. found that VT circuits were generally confined to an area less than approximately 1.4 cm2 of endocardial surface area. Considering that small area in the context of the overall scar size, the probability of randomly biopsied scar tissues containing VT circuits is likewise small, suggesting that literature reporting anatomic or physiological findings in unmapped scar are most likely reporting general scar properties that could play a role in VT mechanism but are very unlikely to be unique to the VT circuit.

Measurement of CV is simple in concept (movement of the electrical signal in distance per unit time) but complicated in the complex three-dimensional fibrotic substrate that is the infarct scar. Correct measurement of CV requires knowledge of both speed and direction of activation.52 In practice, this can be done reliably with optical mapping in ex vivo perfused tissue wedges where stimulation is local, direct propagation from the site of stimulation is observed, and conduction is measured close to the site of stimulation before three-dimensional spread can play a role. CV measurement can be performed in vivo using similar methods, but much of the published literature on in vivo CV does not use these validated methods. A common practice in the literature is to measure CV from surface activation maps, but this requires an assumption that conduction is direct from one marked point to the next along the mapped surface rather than from activation of both surface points from deeper layers. Another difficulty with in vivo mapping is correctly identifying local activation time in what is often a fractionated, low-voltage signal (Figure 2). In addition, CV in vivo is often reported with the source of stimulation remote to the site of measurement, either by mapping during sinus rhythm or with remote, single site ventricular pacing (e.g., from an ICD lead), making it probable that midmyocardial or subsurface conduction is affecting electrical activation timing on the surface.

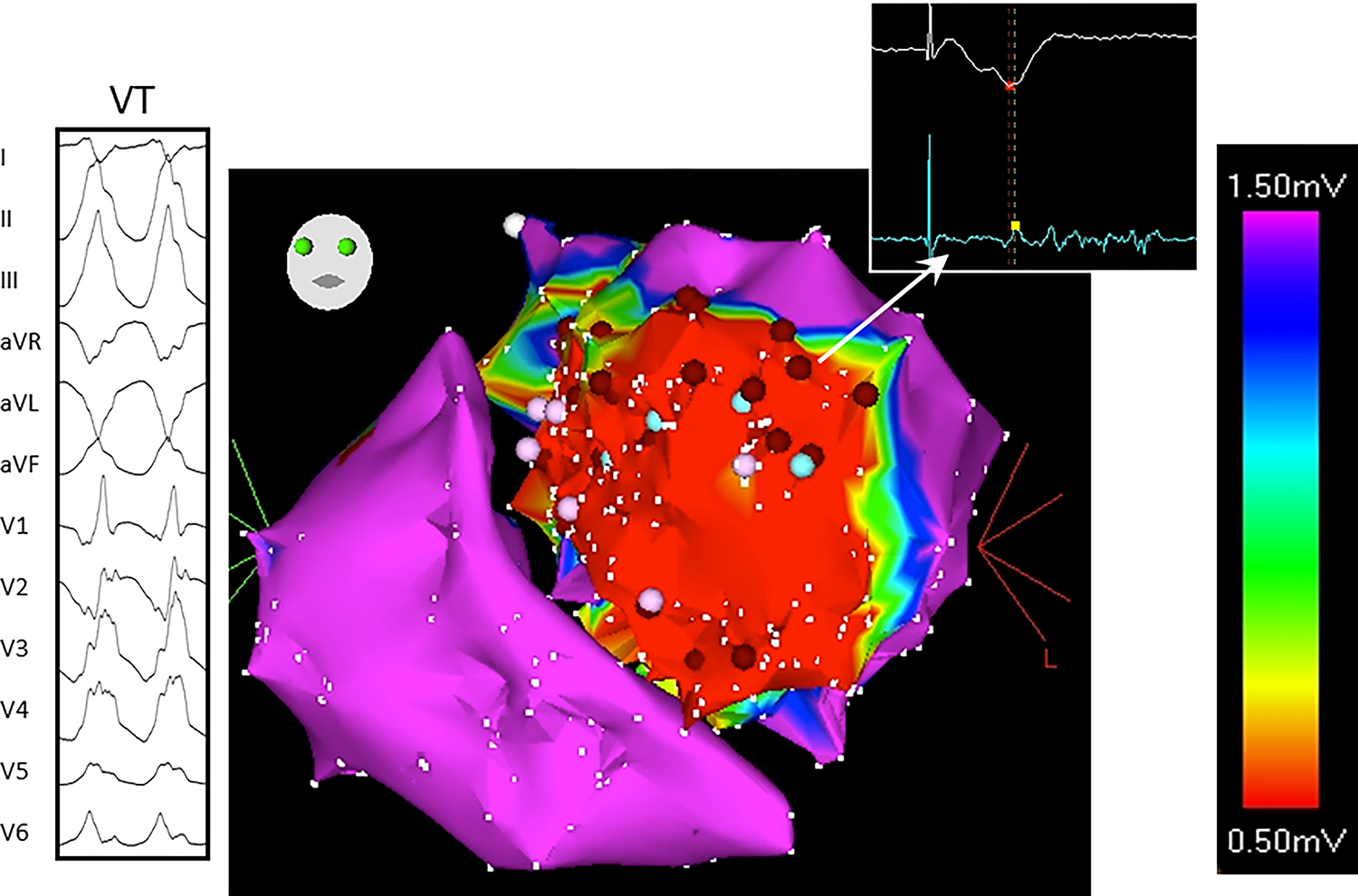

Figure 2:

Typical low voltage, fractionated electrogram recorded from scarred myocardium during VT. The twelve-lead ECG of the VT and bipolar electrogram from the ablation catheter are shown in the left and right insets respectively. The catheter is placed at the site within scarred myocardium where the VT was ultimately ablated. The ablation electrogram shows a low amplitude, split and fractionated electrogram often seen in scar, both at successful and unsuccessful ablation sites. Complexity of this signal illustrates the difficulty in assigning a local activation time for either activation mapping or conduction velocity calculation.

Direct measurement of CV in human post-infarct VT circuits has not yet been performed in a way that is compliant with the above-mentioned standards. However, several studies have looked at factors relevant to CV that can be extrapolated to a hypothesis about CV within the VT circuit and throughout post-MI healed scar.53

Throughout the history of VT investigation, a persistent belief has been that bipolar electrogram characteristics indicative of heterogeneous or slow conduction could identify VT circuits. Kienzle evaluated sinus rhythm electrograms because several electrogram characteristics (split, late, or fractionated potentials) were suspected of identifying VT circuits.54 They studied 13 patients undergoing VT ablation surgery for medically refractory sustained VT. All patients had a history of healed MI. They performed sinus rhythm electrogram mapping followed by VT induction and activation mapping to determine the VT site prior to resection. They found that split, late, and fractionated electrograms were widely distributed throughout the scarred myocardium, occurring equally at VT sites and remote borderzone sites. Their data indicated that sinus rhythm electrograms commonly thought to identify sites at risk for VT were, in fact, not unique to VT circuits. Later studies by Nayyar, Baldinger, and Irie have confirmed the observation that low voltage, split, late, or fractionated electrograms are diffusely present in scarred myocardium and not specific for VT circuits.55–57

Smith et al. performed histological and immunohistochemical analyses in human infarct scar tissues not mapped for VT circuits. They observed profoundly diminished and lateralized connexin 43 (Cx43) expression, suggesting that poor connectivity, and thus conduction slowing, exists throughout the scar.58 In a follow-up study, Peters et al. reported that gap junctional surface area was reduced in healed infarct scar and in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.59 Kostin et al. expanded this observation to non-ischemic and inflammatory cardiomyopathies. They concluded that reduced and lateralized Cx43 was a typical feature of myocardial remodeling in ischemic, non-ischemic, or inflammatory cardiomyopathy.60 Of critical importance in considering the VT mechanism, these investigators found decreased Cx43 and discontinuous conduction in regions of scar not associated with VT,49,58 suggesting that conduction abnormalities are diffusely present in healed infarct scar.

Kawara et al. studied 11 failing human hearts extracted at the time of transplantation; 8 were Langendorff-perfused, and 3 had epicardial sheets of tissue extracted and superfused. Four had coronary disease, 1 had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and 6 had non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy.61 The epicardial sheet superfusion tested conduction in 2 dimensions, and Langendorff perfusion gave the ability to assess conduction in 3 dimensions. Each prep was paced with a drive CL of 600 ms and single extra-stimuli at increasingly shorter coupling until the refractory period was reached. The main readout was activation time of either tissue or heart. In all experimental preps of multiple disease types, the authors noted that cardiac activation time was inversely proportional to coupling interval. The relationship between coupling interval and conduction time was accentuated in areas of fibrosis. The authors did not identify the source of conduction delay, but they speculated 4 possibilities: an increase in pathlength, presumably from areas of transient conduction block at faster pacing rates; change from longitudinal to transverse conduction; change in wavefront curvature at faster pacing rates; or true decremental conduction with reduced conduction velocity at faster rates. Saumarez et al. reported a similar relationship between fibrosis content and conduction delay in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.62

Animal studies have filled in some of the gaps in knowledge left by human work. Kelemen et al. compared VT circuits to infarcted myocardium unassociated with VT in a porcine model of healed anterior infarction.63 The model was previously validated by Sasano et al. to reproduce infarct pathology, functional remodeling, and VT characteristics previously reported in humans.64,65 Kelemen et al. reported decreased Cx43 mRNA, both within the VT circuit and in scarred myocardium not associated with VT. They then looked at the functional effects of this reduction in Cx43. They noted electrogram fractionation throughout all scarred myocardium in vivo and decreased and heterogeneous conduction in all myocardial scar tissue with optical mapping ex vivo.

Greener et al. reported decreased Cx43 total protein, phosphorylation, and intercalated disk localization in healed myocardial scar using the same porcine model.66 Greener connected these Cx43 alterations to post-infarct VT mechanism by showing that gene transfer-induced increases in Cx43 improved local CV and reduced VT inducibility.

Anter et al. evaluated CV during VT in a similar porcine model.67 They mapped macro-reentrant VT circuits and noted heterogeneous conduction. In the outer limb of the VT circuit, conduction was within the normal range. CV slowed at the entrance to the protected isthmus, improved to near normal within the isthmus, and slowed slightly at the exit site between the isthmus and outer loop. They did not report CV in scar unassociated with VT for comparison.

Myocyte excitability has been minimally investigated in humans with post-infarct VT. de Bakker et al. evaluated APs in microelectrode recordings of superfused VT circuit tissues ex vivo.16 They found that approximately half of the evaluated myocytes had normal APs, but the remaining myocytes had reduced RMPs and slow AP upstroke velocities.

No other study has evaluated cellular electrophysiology in myocytes extracted from VT circuits. The only other data on the electrophysiology of human borderzone myocytes comes from tissues not mapped for VT circuits. Dangman et al. reported data on a single patient with post-infarct VT.68 In microelectrode recordings of superfused tissues, they found reduced RMP, AP upstroke velocity, and AP amplitude throughout scarred myocardium in that patient. In a study of 12 patients, Spear et al. reported multiple AP morphologies.69 In 3 patients, they noted entirely normal APs, with normal RMP, AP upstroke velocity, and AP amplitude. In 6 patients, they noted “slow response” APs with depolarized RMP, reduced AP amplitude, and slow depolarization consistent with l-type calcium current as the driver. Two patients had an intermediate phenotype.69 In the Spear report, all patients had heart failure, 11 of 12 had healed MI, but only 3 of 12 had any history of VT.

In the porcine infarct model, Kelemen et al. compared myocytes isolated from healed infarct regions with mapped VT circuits to healed infarct with no VT association.63 They found no difference between cells in the two regions for RMP, AP upstroke velocity, or IK1 (the potassium current responsible for RMP). However, compared to normal myocytes, myocytes isolated from VT and non-VT scarred myocardium had depolarized RMP and reduced AP upstroke velocity consistent with impaired excitability in the myocytes isolated from chronic scar.

No other animal data are available from animals with chronic infarcts and mapped VT circuits. Kimura et al. and Myerburg et al. reported depolarized RMP, decreased AP amplitude, and AP upstroke velocity in infarct border in cats 2–6 months post-MI.70,71 Litwin et al. found decreased l-type calcium current and sodium-calcium exchanger current in border zone myocytes isolated eight weeks after infarction in rabbits.72 Pinto et al. and Aimond et al. also noted decreased calcium current in chronically infarcted cats and rats, respectively.73,74

Overall, these studies show that both myocyte connectivity and electrical excitability are likely impaired in healed scar. Reduced gap junction connectivity occurs diffusely throughout the scar and appears to be a common feature of diseased myocardium from a variety of causes. Reduced cellular excitability may be more regional, with some reports of normal resting membrane potential and electrical activation within scar. Gene transfer studies established a connection between Cx43 alterations and VT mechanism. Cellular excitability has not been conclusively studied in healed scar, so its role in VT mechanism is incompletely known.

Repolarization heterogeneity in the VT circuit.

Unique to de Bakker’s initial study of mapped VT circuits in humans was a report of AP characteristics from microelectrode recordings of human VT circuit tissues.16 Half of the evaluated myocytes had normal APs, but the remaining myocytes had reduced resting membrane potentials, slow upstroke velocities, shortened AP amplitudes, and longer refractory periods. Unfortunately, no subsequent investigation of VT circuit cellular electrophysiology has been performed in humans to expand on this finding.

The only other human data on the repolarization properties of borderzone myocytes comes from tissues not mapped for VT circuits. Dangman et al. reported data on their single patient with post-infarct VT.68 In microelectrode recordings of superfused tissues, they found marked dispersion of APDs between infarcted and adjacent borderzone myocytes. Spear et al. reported longer APDs in their three patients with normal myocyte excitability (427±47 ms infarcted muscle vs. 301±74 ms normal myocardium). They did not report average APD from cells in tissues with impaired excitability.69

To expand on these limited human data, Kelemen et al. used their porcine infarct-VT model to compare ion channel expression and electrical function in mapped VT circuits to infarcted myocardium unassociated with VT and to uninfarcted myocardium.63 They found three different expression patterns: (1) transcripts that had unchanged expression at all three sites, (2) transcripts that were uniformly altered at scar sites relative to uninfarcted myocardium, and (3) transcripts with uniquely altered gene expression in the VT circuit. There were no differences between the three sites for the cardiac sodium channel α-subunit (SCN5A), the α-subunit of the rapid component of the delayed rectifier current IKr (KCNH2), and potassium channel β-subunits KCNE1, and KCNE2, suggesting that these were unaffected by infarction. Transcripts that were uniformly changed across all scar sites included increases in the sodium-calcium exchange pump (NCX1), and decreases in connexin 43 gap junction channel (GJA1), the α-subunit of the slow delayed rectifier current IKs (KCNQ1), the α-subunit of the l-type calcium channel (CACNA1C), and the sarcoplasmic reticular calcium pump (SERCA2a), indicating that these were common properties of scarred myocardium but not unique to the VT circuits. The potassium channel β-subunits KCNE3 and KCNE4 were upregulated only at VT sites. The α-subunit of the inward rectifier current IK1 (KCNJ2) was decreased throughout the scar but more so at VT sites (Figure 3).

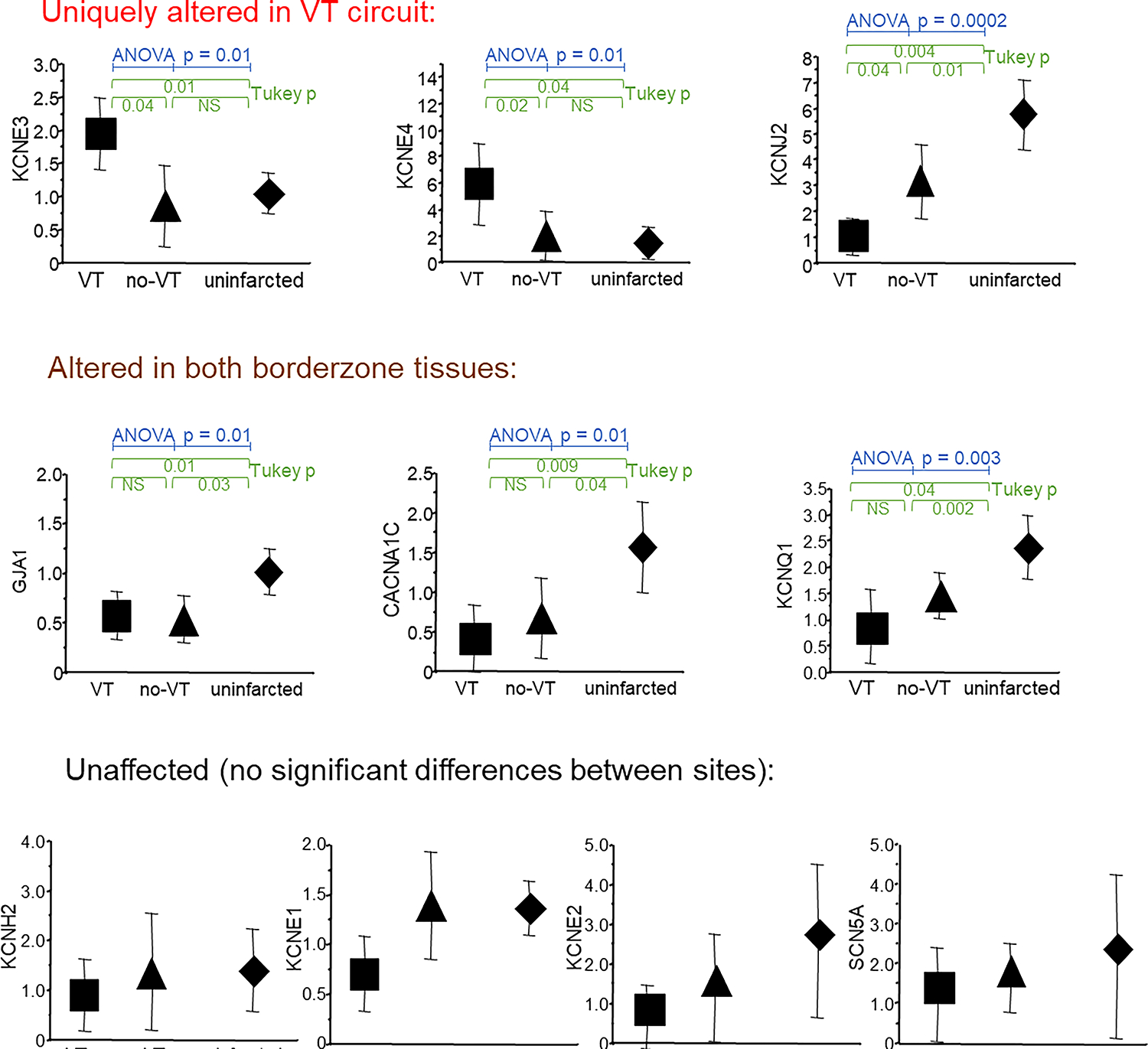

Figure 3:

Comparison of mRNA expression of ion channels and connexin43 at the mapped VT site (square), scarred myocardium unassociated with any VT (triangle) and uninfarcted basal lateral myocardium (diamond). (Adapted with permission from Kelemen et al.63)

To identify unique functional elements of VT circuits, Kelemen et al. assessed conduction and repolarization in vivo, ex vivo with optical mapping, and in vitro with patch clamp studies. Again, they compared VT circuit properties to non-VT scarred myocardium in animals with VT and to scarred myocardium in animals that never had any VT. In the VT circuits, they found a consistent pattern of short APDs adjacent to long APDs, both in vivo and, with optical mapping, ex vivo in perfused myocardial tissue wedges (Figure 4). In addition to static changes in APD for adjacent tissues within the VT circuits, they also reported rate adaptive behavior; the areas with short APDs maintained conduction after an abrupt change in pacing cycle length from 400 to 250 ms, and the adjacent regions with long APDs had temporary conduction delay or block when pacing switched to the faster cycle length. They noted that this behavior created classic conditions for reentry, reported initially by Schmitt and Erlanger in strips of normal turtle ventricular tissues.75, but never previously noted in post-infarct VT circuits. Patch clamp of isolated myocytes from the VT circuit region of VT animals showed APD and IKs heterogeneities consistent with KCNE3 and KCNE4 effects on KCNQ1.76–78 KCNE3 expression increased IKs giving shorter APD, and KCNE4 decreased IKs, prolonging APD.

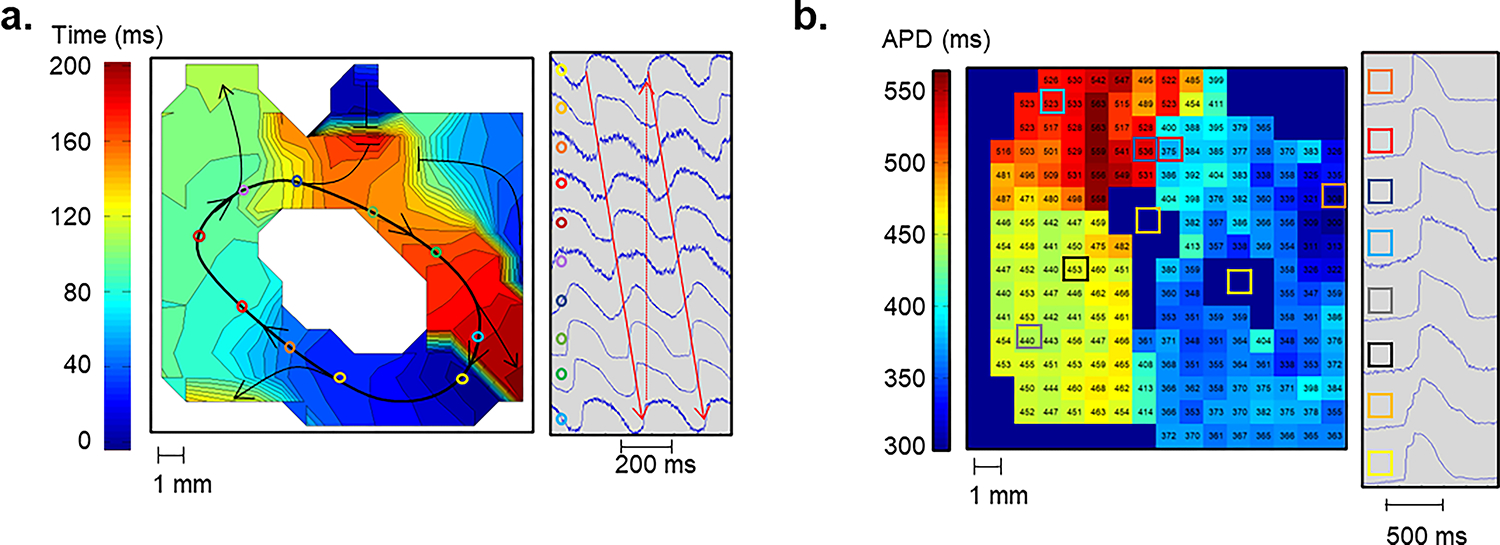

Figure 4:

Complete VT circuit observed during optical mapping with a voltage sensitive dye in a perfused myocardial scar tissue wedge. (A) An isochronal map showing activation of a complete VT circuit is shown. The colored circles indicate locations on the activation map where example pixels at right were located. The white central region had 2:1 activation and did not participate in the VT. (B) An APD map during 1000 ms fixed rate pacing of the full VT circuit tissue from panel A. The colored boxes show locations on the APD map, for example electrograms at right. All observed VT circuits had a tract of tissue with short APDs in contact with a tract of tissue with long APDs. This APD pattern was only seen in optical maps of complete VT circuits. (Adapted with permission from Kelemen et al.63)

Callans and Donahue looked for a similar APD pattern in a small human study of 6 patients with post-infarct VT undergoing VT mapping and ablation.79 They assessed activation-recovery intervals (ARIs), a surrogate for APD obtained from unipolar electrograms.80 They found a similar pattern of short ARIs adjacent to long ARIs at VT circuit sites. In 4 of the studied patients, VT terminated with the delivery of the first ablation lesion located at the site of the shortest ARI. Aronis et al. reported on action potential duration restitution (APDR) in non-infarcted myocardium among 22 patients with ischemic VT compared to normal controls using genetic and computational modeling. They found that myocardial remodeling in ischemic VT patients had steeper APDR suggesting this as an influencing mechanism for the increased arrhythmogenic propensity.81

Autonomic Control of Ventricular Myocardial Electrophysiology.

Ventricular myocardial electrophysiology is under tight autonomic control. All or nearly all ventricular cardiomyocytes interact directly with sensory, sympathetic, and parasympathetic nerves, and autonomic regulation occurs on a beat-to-beat basis.82,83 Sympathetic innervation of the ventricles originates from post-ganglionic neurons within the sympathetic chain, primarily the stellate and middle cervical ganglia, via cardiac nerve branches. Sympathetic nerves directly innervate the ventricular myocardium and ganglionated plexus (GP). Sympathetic nerve terminals within the ventricular myocardium release neurotransmitters, primarily norepinephrine and Neuropeptide Y (NPY), which bind to beta-adrenergic and NPY receptors on the ventricular myocardium, ultimately leading to enhanced ventricular cardiomyocyte excitability, APD shortening, and increased amplitude of the calcium transient. Intrinsic heterogeneity in sympathetic innervation patterns and cardiomyocyte ion channel distribution (e.g., apical-basal gradients in the slow inward rectifying potassium channel, IKs) ensure optimal control of ventricular myocardial depolarization and repolarization patterns, particularly during sympathetic stress.84

Parasympathetic innervation of the myocardium originates primarily from post-ganglionic cholinergic neurons residing within ganglionated plexuses in epicardial fat pads. Parasympathetic innervation of the ventricles is uniform across the ventricles.85,86 The neurotransmitters acetylcholine (ACh) and vasoactive intestinal peptide are released from cholinergic terminals to, among other actions, increase APD primarily via muscarinic ACh receptors on the ventricular myocytes.82

Structural and functional autonomic remodeling in the chronically infarcted ventricle.

Enhanced cardiac sympathetic tone and neurohormonal remodeling are central features of chronic MI.82,87–91 Structural and functional alterations occur in sensory, sympathetic, and parasympathetic nerves in the heart. In addition, intramyocardial nerve remodeling interacts with the above-mentioned features of chronically infarcted myocardium to amplify arrhythmogenic potential (Figure 5).

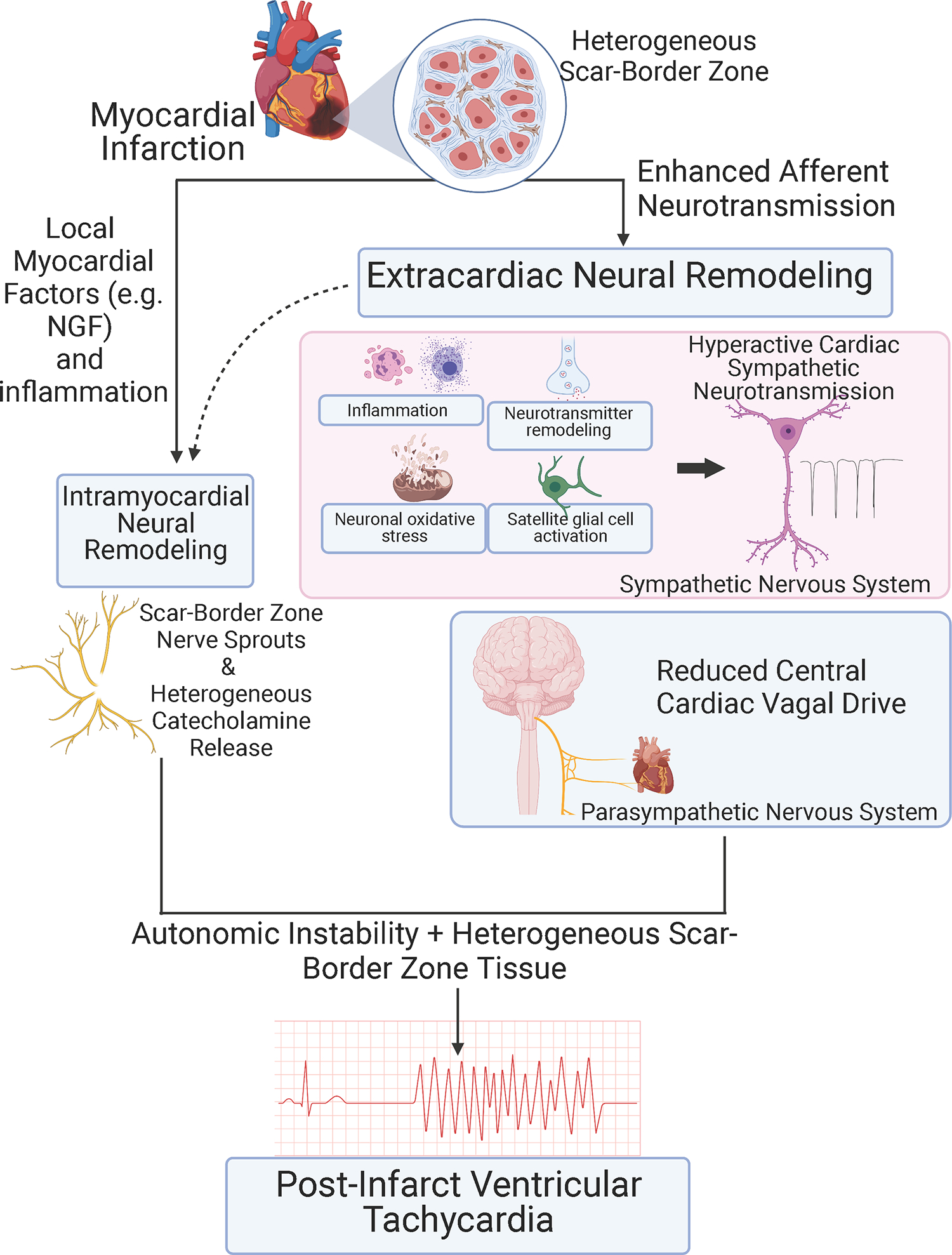

Figure 5:

Schematic showing identified autonomic mechanisms in post-infarct VT. Autonomic instability is the imbalance between sympathetic (proarrhythmic) and parasympathetic (antiarrhythmic) signaling.

Cardiac sensory afferent nerves are considered to be essential pathways for the transmission of cardiac nociception to the central nervous system. Cardiac afferent neurotransmission via sensory afferent nerve fibers expressing the TRPV1 channel is enhanced in the chronically infarcted ventricle.92,93 Chemical depletion of TRPV1 afferents reduces ventricular fibrosis, heterogeneous conduction, and ventricular arrhythmogenesis,92 implicating enhanced afferent neurotransmission in arrhythmia vulnerability and structural remodeling after MI.

Neural remodeling is mechanistically linked to VT.

Sympathetic nerve regeneration (nerve sprouting) post-MI modulates electrophysiologic function in the scar borderzone and has been associated with post-infarct VT.90,94,95 Increases in sympathetic nerve density have been reported in infarcted human hearts resected at transplantation and in both dog and pig models of chronic MI.90,94,95 Intervention to increase nerve sprouting in the infarcted dog heart caused increased ventricular arrhythmia and sudden death incidence.94 Although not studied directly, enhanced arrhythmogenesis is likely via the actions of IKs which shortens the APD. This, coupled with enhanced intracellular calcium, may lead to triggered activity. Sympathetic stimulation in the infarcted pig heart caused heterogeneous activation delay and functional conduction block in the infarct borderzone.90 Sympathetic stimulation in humans with healed infarcts and in the pig infarct model caused heterogeneous repolarization with regions showing APD shortening abutting regions showing APD prolongation in scar border myocardium.90,96 In a mouse model, high-resolution microstructure and functional mapping in post-infarct mouse hearts showed that altered electrical responses to sympathetic stimulation aligned directly with altered sympathetic nerve terminal distribution.97 Taken together, these data suggest that heterogeneously distributed sympathetic nerves in the borderzone interact with heterogeneous scar border conduction, fibrosis, and repolarization to produce conditions permissive for reentrant VT circuits (Figure 5).

The basis for parasympathetic dysfunction in chronic MI is thought to be attenuation of the central parasympathetic drive to the heart.98 Enhanced afferent neurotransmission via vagal afferents may underlie this phenomenon. Ventricular parasympathetic nerve terminals are preserved in the post-infarct heart, but the loss of central vagal drive decreases parasympathetic activity, limiting protective vagal effects on the ventricular myocardium.98

Extracardiac neural remodeling following MI.

Structural sympathetic neural remodeling in chronic MI extends beyond the heart. Post-ganglionic neurons within the stellate ganglia have structural and functional remodeling.87,89,99 In stellate ganglia from patients with cardiomyopathy and electrical storm, stellate ganglia show signs of inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial degeneration and glial cell activation.89 Structural and functional remodeling of stellate ganglion neurons have been reported in the pig chronic infarct model.87,99 Neuronal size is increased, and numbers of neurons staining positive for tyrosine hydroxylase and neuropeptide y are increased. Neuron density is unchanged. Additionally, remodeling of neurons within the parasympathetic and sensory nervous systems (e.g., nodose and dorsal root ganglia) has been reported. 98,100,101 The net result is enhanced destabilizing autonomic influences on the heart that promote VT/VF.

Neuromodulation to treat post-infarct VT.

The contributions of autonomic neural mechanisms to both initiation and maintenance of post-infarct VT suggest neuromodulation as an important therapeutic strategy (Fig 5).82,102 Established post-infarct pharmacotherapy includes beta-adrenergic receptor blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and aldosterone receptor blocking drugs. Beta blockade is a form of direct neuromodulation. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or aldosterone receptor blockers are known to affect autonomic neurons beyond the heart in addition to their direct effects on the myocardium.

More aggressive clinical strategies to reduce excessive cardiac sympathetic signaling target the stellate ganglion or sympathetic chain by either surgical excision,103,104 anesthetic blockade,105,106 or radiofrequency ablation.107 Additional strategies, including axonal modulation of the sympathetic chain using electrical techniques, are currently under development.108–110 Thoracic epidural anesthesia has demonstrated clinical efficacy in controlling post-infarct electrical storm and has been incorporated into several treatment algorithms to manage VT.

Modulation of parasympathetic signaling to the heart is primarily achieved by vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), which has shown promise in large animal studies of post-infarct VT111. While clinical use of VNS is being studied for heart failure (ANTHEM PIVOTAL study),112 the viability of chronic VNS as a therapeutic strategy for adverse cardiac remodeling and post-infarct VT remains unclear.

The importance of clinical neuromodulation for managing post-infarct (and other forms of) VT is underscored by its inclusion in the recent ACC/AHA/HRS guidelines for the management of ventricular arrhythmias.113

Summary

As discussed in this review, the post-infarct VT mechanism includes several factors ubiquitous throughout myocardial scar tissue, and repolarization heterogeneity unique to VT circuits. Autonomic and local nerve remodeling contributes to the mechanism at several levels: hypersympathetic tone-induced PVCs, withdrawal of parasympathetic tone, and potentially neural structural remodeling. The physical VT circuit is composed of connected myocytes coursing through scar tissue adjacent to remodeled sympathetic nerves. The fibrous tissue within the scar creates areas of fixed conduction block and a zig-zag course of myocytes that increases the pathlength for potential reentrant circuits. Decreased gap junction communication from altered Cx43 expression, localization, and phosphorylation slows CV. Reduced RMP, slower AP upstroke and reduced l-type calcium current impair cellular excitability, further reducing CV. Instability in the RMP increases the probability of automatic rhythms. Increased sympathetic tone and reduced l-type calcium current shorten repolarization time. These elements are present throughout scarred myocardium, appearing in randomly collected tissue samples, scar tissues unassociated with VT, and in mapped and extracted VT circuit tissues. Specific to the VT circuit is a pattern of repolarization heterogeneity created by KCNE3- and KCNE4-induced alterations in IKs. KCNE3 increases IKs and shortens repolarization time; KCNE4 decreases IKs, delaying repolarization. Adjacent tracts of myocytes with shorter repolarization time in one tract and longer repolarization time in the other tract sets up the conditions for classical reentry.

Considering all of these factors together suggests mechanisms for initiation and maintenance of VT within the scar. Afterdepolarizations from enhanced sympathetic tone or automatic beats from unstable membranes could generate a triggering PVC. When an appropriately timed PVC arrives at the junction between two tracts of myocytes with KCNE3 and KCNE4-induced repolarization heterogeneities, the PVC will find the later repolarization tract still refractory, and it will continue propagating in the tract with earlier repolarization. Propagation in the VT circuit is slowed by impaired cellular excitability and connectivity in addition to the zig-zag course of conduction, giving time for the return limb of the circuit to recover excitability and reentry to continue. Although KCNE3 and KCNE4 expression appears so far to be a unique property of post-infarct VT circuits, the basic reentrant behavior is not different from the accepted paradigm of myocardial reentry first proposed by Schmitt and Erlanger.75

An appealing aspect of this post-infarct VT mechanism is the compatibility with the observation that even in patients highly susceptible to VT, it is still a relatively rare event. If only fixed elements of tissue discontinuities and slow conduction were present, VT would be expected to occur frequently because these factors are continually present. Adding the functional element of heterogeneous repolarization requires a precisely timed premature beat to activate the VT circuit, giving VT events the rarity observed in clinical practice. These anatomic and physiologic features of chronic infarct scar, in general, and the VT circuit tissues, in particular, should be useful in developing next generation diagnostics and therapeutics to improve care of affected patients.

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported by grants from the NIH – NHLBI: HL134185 and HL167185 (JKD), HL159001 and HL162717 (OAA), a Bassick Family Foundation grant from the Worcester Foundation for Biomedical Research and a Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Award.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- Ach

acetylcholine

- AP

action potential

- APD

action potential duration

- APDR

action potential duration restitution

- ARI

activation-recovery interval

- CV

conduction velocity

- Cx43

connexin 43

- GP

ganglionic plexus

- MI

myocardial infarction

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- RMP

resting membrane potential

- SCD

sudden cardiac death

- VNS

vagus nerve stimulation

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

Footnotes

Disclosures: JKD has filed a patent for intellectual property owned by the UMass Chan Medical School in the area of repolarization heterogeneity in VT. JC reports honoraria from Abbott. OAA has filed a patent for intellectual property owned by University of California Regents in the areas of catheter ablation and neuromodulation. OAA reports honoraria from Biosense Webster.

Literature Cited:

- 1.Bridges C, Burkman J, Malekan R, Konig S, Chen H, Yarnall C, Gardner T, Stewart A, Stecker M, Patterson T and Stedman H. Global cardiac-specific transgene expression using cardiopulmonary bypass with cardiac isolation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1939–1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berdowski J, Berg RA, Tijssen JG and Koster RW. Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: Systematic review of 67 prospective studies. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pouleur AC, Barkoudah E, Uno H, Skali H, Finn PV, Zelenkofske SL, Belenkov YN, Mareev V, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau JL, Maggioni AP, Kober L, Califf RM, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA and Solomon SD. Pathogenesis of sudden unexpected death in a clinical trial of patients with myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, or both. Circulation. 2010;122:597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinhaus DA, Vittinghoff E, Moffatt E, Hart AP, Ursell P and Tseng ZH. Characteristics of sudden arrhythmic death in a diverse, urban community. Am Heart J. 2012;163:125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janse MJ and Wit AL. Electrophysiological mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias resulting from myocardial ischemia and infarction. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:1049–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cascio WE, Yang H, Muller-Borer BJ and Johnson TA. Ischemia-induced arrhythmia: the role of connexins, gap junctions, and attendant changes in impulse propagation. J Electrocardiol. 2005;38:55–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubart M and Zipes DP. Mechanisms of sudden cardiac death. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2305–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciaccio EJ, Anter E, Coromilas J, Wan EY, Yarmohammadi H, Wit AL, Peters NS and Garan H. Structure and function of the ventricular tachycardia isthmus. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19:137–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes JW, Borg TK and Covell JW. Structure and mechanics of healing myocardial infarcts. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:223–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fishbein MC, Maclean D and Maroko PR. The histopathologic evolution of myocardial infarction. Chest. 1978;73:843–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lodge-Patch I The ageing of cardiac infarcts, and its influence on cardiac rupture. Br Heart J. 1951;13:37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallory GK, White PD and Salcedo-Salgar J. The speed of healing of myocardial infarction: a study of the pathologic anatomy in seventy-two cases. Am Heart J. 1939;18:647–671. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinto JM and Boyden PA. Electrical remodeling in ischemia and infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:284–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothman S, Hsia H, Cossu S, Chmielewski I, Buxton A and Miller J. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of postinfarction ventricular tachycardia: long-term success and the significance of inducible nonclinical arrhythmias. Circulation. 1997;96:3499–3508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pogwizd S, Hoyt R, Saffitz J, Corr P, Cox J and Cain M. Reentrant and focal mechanisms underlying ventricular tachycardia in the human heart. Circulation. 1992;86:1872–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Bakker J, van Capelle F, Janse M, Wilde A, Coronel R, Becker A, Dingemans K, van Hemel N and Hauer R. Reentry as a cause of ventricular tachycardia in patients with chronic ischemic heart disease: electrophysiologic and anatomic correlation. Circulation. 1988;77:589–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Bakker J, Coronel R, Tasseron S, Wilde A, Opthof T, Janse M, van Capelle F, Becker A and Jambroes G. Ventricular tachycardia in the infarcted, Langendorff-perfused human heart: role of the arrangement of surviving cardiac fibers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1594–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burashnikov A and Antzelevitch C. Reinduction of atrial fibrillation immediately after termination of the arrhythmia is mediated by late phase 3 early afterdepolarization-induced triggered activity. Circulation. 2003;107:2355–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antzelevitch C and Burashnikov A. Overview of Basic Mechanisms of Cardiac Arrhythmia. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2011;3:23–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mines GR. On dynamic equilibrium in the heart. J Physiol. 1913;46:349–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mines GR. On circulating excitations in heart muscles and their possible relation to tachycardia and fibrillation. Trans Roy Soc Can. 1914;8:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wit AL and Cranefield PF. Reentrant excitation as a cause of cardiac arrhythmias. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:H1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Josephson ME, Horowitz LN, Farshidi A and Kastor JA. Recurrent sustained ventricular tachycardia. 1. Mechanisms. Circulation. 1978;57:431–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wellens HJ, Duren DR and Lie KI. Observations on mechanisms of ventricular tachycardia in man. Circulation. 1976;54:237–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mines G On dynamic equilibrium in the heart. J Physiol. 1913;46:349–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durrer D, Schoo L, Schuilenburg RM and Wellens HJ. The role of premature beats in the initiation and the termination of supraventricular tachycardia in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Circulation. 1967;36:644–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wellens HJ. Value and limitations of programmed electrical stimulation of the heart in the study and treatment of tachycardias. Circulation. 1978;57:845–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wellens HJ, Schuilenburg RM and Durrer D. Electrical stimulation of the heart in patients with ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1972;46:216–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Denes P, Wu D, Dhingra RC, Amat-y-Leon R, Wyndham C, Mautner RK and Rosen KM. Electrophysiological studies in patients with chronic recurrent ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1976;54:229–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wit AL and Cranefield PF. Triggered activity in cardiac muscle fibers of the simian mitral valve. Circ Res. 1976;38:85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cranefield PF and Aronson RS. Initiation of sustained rhythmic activity by single propagated action potentials in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers exposed to sodium-free solution or to ouabain. Circ Res. 1974;34:477–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Josephson ME, Horowitz LN and Farshidi A. Continuous local electrical activity. A mechanism of recurrent ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1978;57:659–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallagher JJ, Oldham HN, Wallace AG, Peter RH and Kasell J. Ventricular aneurysm with ventricular tachycardia. Report of a case with epicardial mapping and successful resection. Am J Cardiol. 1975;35:696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guiraudon G, Fontaine G, Frank R, Escande G, Etievent P and Cabrol C. Encircling endocardial ventriculotomy: a new surgical treatment for life-threatening ventricular tachycardias resistant to medical treatment following myocardial infarction. Ann Thorac Surg. 1978;26:438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harken AH, Josephson ME and Horowitz LN. Surgical endocardial resection for the treatment of malignant ventricular tachycardia. Ann Surg. 1979;190:456–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevenson WG, Khan H, Sager P, Saxon LA, Middlekauff HR, Natterson PD and Wiener I. Identification of reentry circuit sites during catheter mapping and radiofrequency ablation of ventricular tachycardia late after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1993;88:1647–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Sherif N, Gough WB, Zeiler RH and Mehra R. Triggered ventricular rhythms in 1-day-old myocardial infarction in the dog. Circ Res. 1983;52:566–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.le Marec H, Dangman KH, Danilo P Jr. and Rosen MR. An evaluation of automaticity and triggered activity in the canine heart one to four days after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1985;71:1224–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carmeliet E Cardiac ionic currents and acute ischemia: from channels to arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:917–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sattler SM, Skibsbye L, Linz D, Lubberding AF, Tfelt-Hansen J and Jespersen T. Ventricular Arrhythmias in First Acute Myocardial Infarction: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Interventions in Large Animal Models. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiesfeld AC, Crijns HJ, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Gilst WH and Lie KI. Triggered activity as arrhythmogenic mechanism after myocardial infarction: clinical and electrophysiologic study of one case. Clin Cardiol. 1992;15:689–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arevalo H, Plank G, Helm P, Halperin H and Trayanova N. Tachycardia in post-infarction hearts: insights from 3D image-based ventricular models. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie E, Mayer K, Capps MF, Barth AS, Love CJ, Coronel R and Ashikaga H. Mechanism of spontaneous initiation of ventricular fibrillation in patients with implantable defibrillators. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31:2415–2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roelke M, Garan H, McGovern BA and Ruskin JN. Analysis of the initiation of spontaneous monomorphic ventricular tachycardia by stored intracardiac electrograms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Chillou C, Lacroix D, Klug D, Magnin-Poull I, Marquie C, Messier M, Andronache M, Kouakam C, Sadoul N, Chen J, Aliot E and Kacet S. Isthmus characteristics of reentrant ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fenoglio JJ Jr., Pham TD, Harken AH, Horowitz LN, Josephson ME and Wit AL. Recurrent sustained ventricular tachycardia: structure and ultrastructure of subendocardial regions in which tachycardia originates. Circulation. 1983;68:518–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolick D, Hackel D, Reimer K and Ideker R. Quantitative analysis of myocardial infarct structure in patients with ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1986;74:1266–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Bakker JM, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ, van Hemel NM, Hauer RN, Defauw JJ, Vermeulen FE and Bakker de Wekker PF. Macroreentry in the infarcted human heart: the mechanism of ventricular tachycardias with a “focal” activation pattern. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:1005–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Bakker J, van Capelle F, Janse M, Tasseron S, Vermeulen J, de Jonge N and Lahpor J. Slow conduction in the infarcted human heart. ‘Zigzag’ course of activation. Circulation. 1993;88:915–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tung R, Raiman M, Liao H, Zhan X, Chung FP, Nagel R, Hu H, Jian J, Shatz DY, Besser SA, Aziz ZA, Beaser AD, Upadhyay GA, Nayak HM, Nishimura T, Xue Y and Wu S. Simultaneous Endocardial and Epicardial Delineation of 3D Reentrant Ventricular Tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:884–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciaccio EJ, Coromilas J, Wit AL, Peters NS and Garan H. Source-Sink Mismatch Causing Functional Conduction Block in Re-Entrant Ventricular Tachycardia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cantwell MJ, Sharma S, Friedmann T and Kipps TJ. Adenovirus vector infection of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. 1997;88:4676–4683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aronis KN, Ali RL, Prakosa A, Ashikaga H, Berger RD, Hakim JB, Liang J, Tandri H, Teng F, Chrispin J and Trayanova NA. Accurate Conduction Velocity Maps and Their Association With Scar Distribution on Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients With Postinfarction Ventricular Tachycardias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13:e007792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kienzle MG, Miller J, Falcone RA, Harken A and Josephson ME. Intraoperative endocardial mapping during sinus rhythm: relationship to site of origin of ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1984;70:957–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nayyar S, Wilson L, Ganesan A, Sullivan T, Kuklik P, Young G, Sanders P and Roberts-Thomson KC. Electrophysiologic features of protected channels in late postinfarction patients with and without spontaneous ventricular tachycardia. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2018;51:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baldinger SH, Nagashima K, Kumar S, Barbhaiya CR, Choi EK, Epstein LM, Michaud GF, John R, Tedrow UB and Stevenson WG. Electrogram analysis and pacing are complimentary for recognition of abnormal conduction and far-field potentials during substrate mapping of infarct-related ventricular tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:874–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Irie T, Yu R, Bradfield JS, Vaseghi M, Buch EF, Ajijola O, Macias C, Fujimura O, Mandapati R, Boyle NG, Shivkumar K and Tung R. Relationship between sinus rhythm late activation zones and critical sites for scar-related ventricular tachycardia: systematic analysis of isochronal late activation mapping. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:390–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith J, Green C, Peters N, Rothery S and Severs N. Altered patterns of gap junction distribution in ischemic heart disease. An immunohistochemical study of human myocardium using laser scanning confocal microscopy. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:801–821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peters NS, Green CR, Poole-Wilson PA and Severs NJ. Reduced content of connexin43 gap junctions in ventricular myocardium from hypertrophied and ischemic human hearts. Circulation. 1993;88:864–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kostin S, Rieger M, Dammer S, Hein S, Richter M, Klovekorn WP, Bauer EP and Schaper J. Gap junction remodeling and altered connexin43 expression in the failing human heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;242:135–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawara T, Derksen R, de Groot JR, Coronel R, Tasseron S, Linnenbank AC, Hauer RN, Kirkels H, Janse MJ and de Bakker JM. Activation delay after premature stimulation in chronically diseased human myocardium relates to the architecture of interstitial fibrosis. Circulation. 2001;104:3069–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saumarez RC and Grace AA. Paced ventricular electrogram fractionation and sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and other non-coronary heart diseases. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kelemen K, Greener ID, Wan X, Parajuli S and Donahue JK. Heterogeneous repolarization creates ventricular tachycardia circuits in healed myocardial infarction scar. Nat Commun. 2022;13:830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sasano T, Kelemen K, Greener ID and Donahue JK. Ventricular tachycardia from the healed myocardial infarction scar: validation of an animal model and utility of gene therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:S91–S97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deneke T, Muller KM, Lemke B, Lawo T, Calcum B, Helwing M, Mugge A and Grewe PH. Human histopathology of electroanatomic mapping after cooled-tip radiofrequency ablation to treat ventricular tachycardia in remote myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:1246–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greener ID, Sasano T, Wan X, Igarashi T, Strom M, Rosenbaum DS and Donahue JK. Connexin43 gene transfer reduces ventricular tachycardia susceptibility after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1103–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anter E, Tschabrunn CM, Buxton AE and Josephson ME. High-Resolution Mapping of Postinfarction Reentrant Ventricular Tachycardia: Electrophysiological Characterization of the Circuit. Circulation. 2016;134:314–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dangman KH, Danilo P Jr., Hordof AJ, Mary-Rabine L, Reder RF and Rosen MR. Electrophysiologic characteristics of human ventricular and Purkinje fibers. Circulation. 1982;65:362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spear JF, Horowitz LN, Hodess AB, MacVaugh H, III EN. Cellular electrophysiology of human myocardial infarction. 1. Abnormalities of cellular activation. Circulation. 1979;59:247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Myerburg RJ, Bassett AL, Epstein K, Gaide MS, Kozlovskis P, Wong SS, Castellanos A and Gelband H. Electrophysiological effects or procainamide in acute and healed experimental ischemic injury of cat myocardium. Circ Res. 1982;50:386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kimura S, Bassett AL, Gaide MS, Kozlovskis PL and Myerburg RJ. Regional changes in intracellular potassium and sodium activity after healing of experimental myocardial infarction in cats. Circ Res. 1986;58:202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Litwin S and Bridge J. Enhanced Na(+)-Ca2+ exchange in the infarcted heart. Implications for excitation-contraction coupling. Circ Res. 1997;81:1083–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pinto J, Yuan F, Wasserlauf B, Bassett A and Myerburg R. Regional gradation of L-type calcium currents in the feline heart with a healed myocardial infarct. J Cardiovasc Electrophys. 1997;8:548–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aimond F, Alvarez J, Rauzier J, Lorente P and Vassort G. Ionic basis of ventricular arrhythmias in remodeled rat heart during long-term myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:402–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmitt FO and Erlanger J. Directional differences in the conduction of the impulse through heart muscle and their possible relation to extrasystolic and fibrillary contractions. Am J Physiol. 1928;87:326–347. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bendahhou S, Marionneau C, Haurogne K, Larroque MM, Derand R, Szuts V, Escande D, Demolombe S and Barhanin J. In vitro molecular interactions and distribution of KCNE family with KCNQ1 in the human heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schroeder BC, Waldegger S, Fehr S, Bleich M, Warth R, Greger R and Jentsch TJ. A constitutively open potassium channel formed by KCNQ1 and KCNE3. Nature. 2000;403:196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grunnet M, Jespersen T, Rasmussen HB, Ljungstrom T, Jorgensen NK, Olesen SP and Klaerke DA. KCNE4 is an inhibitory subunit to the KCNQ1 channel. J Physiol. 2002;542:119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Callans DJ and Donahue JK. Repolarization heterogeneity in human post infarct ventricular tachycardia. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2022:8:713–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen PS, Moser KM, Dembitsky WP, Auger WR, Daily PO, Calisi CM, Jamieson SW and Feld GK. Epicardial activation and repolarization patterns in patients with right ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 1991;83:104–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aronis KN, Prakosa A, Bergamaschi T, Berger RD, Boyle PM, Chrispin J, Ju S, Marine JE, Sinha S, Tandri H, Ashikaga H and Trayanova NA. Characterization of the Electrophysiologic Remodeling of Patients With Ischemic Cardiomyopathy by Clinical Measurements and Computer Simulations Coupled With Machine Learning. Front Physiol. 2021;12:684149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shivkumar K, Ajijola OA, Anand I, Armour JA, Chen PS, Esler M, De Ferrari GM, Fishbein MC, Goldberger JJ, Harper RM, Joyner MJ, Khalsa SS, Kumar R, Lane R, Mahajan A, Po S, Schwartz PJ, Somers VK, Valderrabano M, Vaseghi M and Zipes DP. Clinical neurocardiology defining the value of neuroscience-based cardiovascular therapeutics. J Physiol. 2016;594:3911–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fukuda K, Kanazawa H, Aizawa Y, Ardell JL and Shivkumar K. Cardiac innervation and sudden cardiac death. Circ Res. 2015;116:2005–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mantravadi R, Gabris B, Liu T, Choi BR, de Groat WC, Ng GA and Salama G. Autonomic Nerve Stimulation Reverses Ventricular Repolarization Sequence in Rabbit Hearts. Circulation Research. 2007;100:e72–e80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ardell JL, Rajendran PS, Nier HA, KenKnight BH and Armour JA. Central-peripheral neural network interactions evoked by vagus nerve stimulation: functional consequences on control of cardiac function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1740–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamakawa K, So EL, Rajendran PS, Hoang JD, Makkar N, Mahajan A, Shivkumar K and Vaseghi M. Electrophysiological effects of right and left vagal nerve stimulation on the ventricular myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H722–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ajijola OA, Yagishita D, Reddy NK, Yamakawa K, Vaseghi M, Downs AM, Hoover DB, Ardell JL and Shivkumar K. Remodeling of stellate ganglion neurons after spatially targeted myocardial infarction: Neuropeptide and morphologic changes. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2015;12:1027–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gardner RT, Ripplinger CM, Myles RC and Habecker BA. Molecular Mechanisms of Sympathetic Remodeling and Arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ajijola OA, Hoover DB, Simerly TM, Brown TC, Yanagawa J, Biniwale RM, Lee JM, Sadeghi A, Khanlou N, Ardell JL and Shivkumar K. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and glial cell activation characterize stellate ganglia from humans with electrical storm. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e94715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ajijola OA, Lux RL, Khahera A, Kwon O, Aliotta E, Ennis D, Fishbein MC, Ardell JL and Shivkumar K. Sympathetic Modulation of Electrical Activation In Normal and Infarcted Myocardium: Implications for Arrhythmogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312:H608–H621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tapa S, Wang L, Francis Stuart SD, Wang Z, Jiang Y, Habecker BA and Ripplinger CM. Adrenergic supersensitivity and impaired neural control of cardiac electrophysiology following regional cardiac sympathetic nerve loss. Scientific reports. 2020;10:18801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoshie K, Rajendran PS, Massoud L, Mistry J, Swid MA, Wu X, Sallam T, Zhang R, Goldhaber JI, Salavatian S and Ajijola OA. Cardiac TRPV1 afferent signaling promotes arrhythmogenic ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. JCI Insight. 2020;5:e124477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang HJ, Wang W, Cornish KG, Rozanski GJ and Zucker IH. Cardiac sympathetic afferent denervation attenuates cardiac remodeling and improves cardiovascular dysfunction in rats with heart failure. Hypertension. 2014;64:745–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cao JM, Chen LS, KenKnight BH, Ohara T, Lee MH, Tsai J, Lai WW, Karagueuzian HS, Wolf PL, Fishbein MC and Chen PS. Nerve sprouting and sudden cardiac death. Circulation Research. 2000;86:816–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cao JM, Fishbein MC, Han JB, Lai WW, Lai AC, Wu TJ, Czer L, Wolf PL, Denton TA, Shintaku IP, Chen PS and Chen LS. Relationship between regional cardiac hyperinnervation and ventricular arrhythmia. Circulation. 2000;101:1960–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vaseghi M, Lux RL, Mahajan A and Shivkumar K. Sympathetic stimulation increases dispersion of repolarization in humans with myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1838–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhu C, Rajendran PS, Hanna P, Efimov IR, Salama G, Fowlkes CC and Shivkumar K. High-resolution structure-function mapping of intact hearts reveals altered sympathetic control of infarct border zones. JCI Insight. 2022;7:e153913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Salavatian S, Hoang JD, Yamaguchi N, Lokhandwala ZA, Swid MA, Armour JA, Ardell JL and Vaseghi M. Myocardial infarction reduces cardiac nociceptive neurotransmission through the vagal ganglia. JCI Insight. 2022;7:e155747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ajijola OA, Wisco JJ, Lambert HW, Mahajan A, Stark E, Fishbein MC and Shivkumar K. Extracardiac neural remodeling in humans with cardiomyopathy. Circulation Arrhythmia and electrophysiology. 2012;5:1010–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Beaumont E, Southerland EM, Hardwick JC, Wright GL, Ryan S, Li Y, KenKnight BH, Armour JA and Ardell JL. Vagus nerve stimulation mitigates intrinsic cardiac neuronal and adverse myocyte remodeling postmyocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gao C, Howard-Quijano K, Rau C, Takamiya T, Song Y, Shivkumar K, Wang Y and Mahajan A. Inflammatory and apoptotic remodeling in autonomic nervous system following myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mehra R, Tjurmina OA, Ajijola OA, Arora R, Bolser DC, Chapleau MW, Chen P-S, Clancy CE, Delisle BP, Gold MR, Goldberger JJ, Goldstein DS, Habecker BA, Handoko ML, Harvey R, Hummel JP, Hund T, Meyer C, Redline S, Ripplinger CM, Simon MA, Somers VK, Stavrakis S, Taylor-Clark T, Undem BJ, Verrier RL, Zucker IH, Sopko G and Shivkumar K. Research Opportunities in Autonomic Neural Mechanisms of Cardiopulmonary Regulation. JACC: Basic to Translational Science. 2022;7:265–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ajijola OA, Lellouche N, Bourke T, Tung R, Ahn S, Mahajan A and Shivkumar K. Bilateral Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation for the Management of Electrical Storm Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;59:91–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bourke T, Vaseghi M, Michowitz Y, Sankhla V, Shah M, Swapna N, Boyle NG, Mahajan A, Narasimhan C, Lokhandwala Y and Shivkumar K. Neuraxial modulation for refractory ventricular arrhythmias: value of thoracic epidural anesthesia and surgical left cardiac sympathetic denervation. Circulation. 2010;121:2255–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fudim M, Boortz-Marx R, Ganesh A, Waldron NH, Qadri YJ, Patel CB, Milano CA, Sun AY, Mathew JP and Piccini JP. Stellate ganglion blockade for the treatment of refractory ventricular arrhythmias: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017;28:1460–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Meng L, Tseng CH, Shivkumar K and Ajijola O. Efficacy of Stellate Ganglion Blockade in Managing Electrical Storm: A Systematic Review. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;3:942–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hayase J, Patel J, Narayan SM and Krummen DE. Percutaneous stellate ganglion block suppressing VT and VF in a patient refractory to VT ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24:926–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hadaya J, Buckley U, Gurel NZ, Chan CA, Swid MA, Bhadra N, Vrabec TL, Hoang JD, Smith C, Shivkumar K and Ardell JL. Scalable and reversible axonal neuromodulation of the sympathetic chain for cardiac control. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022;322:H105–h115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]