Abstract

Introduction

Injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT) with diacetylmorphine is an effective option for individuals previously considered non-responsive to opioid substitution treatment. Despite implementation in Canada and several European countries, relatively few eligible people choose to initiate iOAT. To better understand what encourages or deters prospective patients from initiating iOAT, the current study explores patients’ perceptions on iOAT and how these influence therapy initiation in practice.

Methods

We conducted 34 semi-structured interviews with individuals currently in or eligible for iOAT in two German outpatient iOAT clinics. Transcripts were analysed following qualitative content analysis, with development of inductive categories and use of consensual coding. For member checking, we consulted individuals with lived experiences prior to data collection and publication.

Results

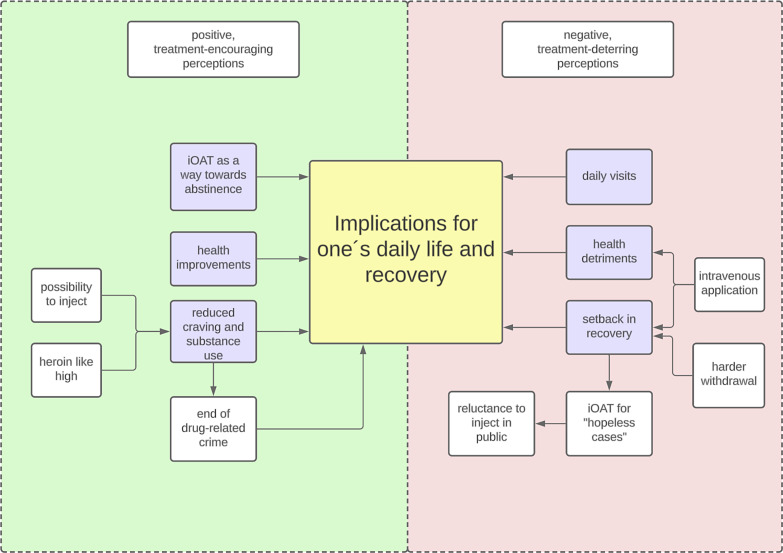

Participants based their choice to initiate iOAT on the perceived implications of the treatment on one’s daily life and individual recovery. Participants were encouraged to initiate iOAT due to the therapy’s perceived potential in reducing cravings and substance use, its positive health consequences, and due to the image of iOAT as a path towards abstinence. Regarding deterring perceptions, participants feared a profound impairment of daily life due to factors such as the daily visits to the clinic, were concerned about whether iOAT would sufficiently promote or even impede one’s recovery, and described negative health effects.

Conclusion

Perceptions found in this study profoundly influenced participants’ decisions on iOAT enrolment and contextualize the previous literature. The study reveals the dynamic coexistence of different perceptions about iOAT and sheds light on the inner-group stigmatization of iOAT. Practitioners and future research should acknowledge the complexities found in the current study in order to exploit the full potential of effective treatment modalities such as iOAT.

Keywords: Patient perspective, Opioid use disorder, Qualitative research, Injectable opioid agonist treatment

Introduction

Background

Opioid use disorder (OUD) and its consequences remain a major global health concern [1]. To date, opioid agonist treatment (OAT) is the most effective treatment for people living with OUD [2, 3]. While oral OAT (oOAT) with methadone or buprenorphine dominates treatment regimens, not all individuals living with OUD respond to these and novel treatment modalities have emerged [4, 5]. One of these is supervised injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT) with bolus injections of diacetylmorphine (DAM) or hydromorphone. In contrast to other injectable treatments (e.g., extended-release buprenorphine), iOAT provides a transient flooding rather than maximum stability of mu-receptor agonism. In iOAT, patients inject their medication in specialized outpatient clinics under the supervision of healthcare staff. The therapy is effective and suited particularly for individuals living with severe OUD who have not benefited sufficiently from oOAT [6, 7]. For this population, randomized controlled trials found iOAT to reduce street heroin use and improve treatment retention, health, and social functioning [8]. Considering these findings, iOAT has been implemented in Canada and several European countries for individuals for whom other forms of OAT had not been successful (see Table 1) [9].

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for iOAT

|

In all countries providing iOAT there are certain criteria which must be met to enrol in iOAT. These usually include: |

|

|

|

|

| In Germany, eligibility criteria for iOAT are: |

|

|

|

|

In Germany, DAM-based iOAT was made available to individuals living with therapy-refractory OUD in 2009 [10, 11]. While, for patients in oOAT, takeaway doses and pharmacy-based dispensing are available, this is not possible in iOAT due to the existing regulatory framework in Germany [12]. Despite its benefits, iOAT’s implementation and acceptance among individuals living with OUD remain limited in Germany. This has profound negative implications especially for those living with severe OUD who could benefit greatly from the treatment [13, 14].

Barriers to treatment seeking exist on multiple, interconnected levels. Informed by pertinent health behaviour theories, the current study examines the individual level to better understand what encourages or deters individuals living with OUD from initiating iOAT and to contribute to the successful implementation of the therapy in and beyond Germany.

The Importance of Perceptions

In addition to the larger structural contexts in which OAT is provided, there is growing interest in perceptions towards treatment as individual-level factors influencing the initiation of OAT [15–19]. These perceptions primarily regard patients’ beliefs about a treatment’s positive and negative effects and about how perceived attributes of the treatment coincide with individuals’ concepts of recovery. Although seldom discussed explicitly, this is in line with several, partly overlapping health behaviour theories (e.g., the health belief model or the theory of planned behaviour). These posit that individuals’ beliefs and perceptions about a treatment significantly influence their choices to initiate or continue a particular health intervention and provide a useful basis to explore the relationship between perceptions and treatment seeking [20].

Regarding iOAT, studies on patients’ perceptions have focused on those that encourage treatment initiation. Individuals unresponsive to oOAT were motivated to start iOAT as a result of perceived benefits such as the reduction of street heroin use and criminal activities, achieving stability and normality, improving their health status, and having a dependable source of safe opioids [21–25]. While this is comparable to studies on oOAT, recent qualitative enquiries additionally found perceptions of the ineffectiveness of oOAT and the option to inject as encouraging for iOAT initiation [26, 27]. Although less extensively studied, there are some data that represent perceptions that deter enrolment in iOAT. These include procedural aspects such as the daily supervised application as well as individuals’ fears of exacerbating their OUD and not seeing their goals of recovery reflected in iOAT [24, 27, 28].

These findings, however, might not be easily transferable to iOAT in Germany due to variations in social and healthcare contexts, including the limited [28] or uncertain [27] time-frame of the programmes studied in the past. Furthermore, as most studies have focused on either positive or negative aspects, it remains questionable how encouraging and deterring perceptions interact and might hinder iOAT engagement in practice. When studies did explore both positive and negative perceptions on iOAT, they did so either in a highly theoretical setting where iOAT was not a realistic option for participants [24] or focused solely on people currently engaged in iOAT [27].

To enrich the current evidence base for the initiation of iOAT, we investigated the perceptions of people currently in or eligible for DAM treatment in two German outpatient iOAT clinics and how these influence iOAT initiation in practice. Leveraging the benefits of qualitative research [29], which remains scarce in studies on iOAT [9], we followed an exploratory, patient-centred approach guided by the research question What encourages or deters People living with OUD from initiating iOAT?

By delving into patients’ experiences and perspectives, we aim to shed light on the complexities and significance of individual-level perceptions that influence iOAT initiation. Our findings can contribute to the development of targeted interventions that address misconceptions and bolster positive attitudes towards iOAT, ultimately improving the care for individuals living with severe OUD.

Materials and Methods

The data for this article stem from a qualitative interview study with individuals currently in or eligible for iOAT, which investigated their perspectives on iOAT. Inclusion criteria for the interview study were purposefully broad to encompass a wide range of experiences. They included individuals currently receiving OAT who fulfilled German eligibility criteria for iOAT [10] and were capable to provide informed consent. The research was approved by the ethics committee of Landesärztekammer Baden-Württemberg, file number F-2022-002.

Based on the research aim and prior studies in health services research, Authors 1, 3, and 4 developed semi-structured interview guides. Specifically, we conducted an extensive (although non-systematic) literature review on various aspects of OAT, including patient perceptions, treatment initiation, and barriers to care. The key issues derived from prior research and the extensive clinical experience of several members of the research team were instrumental in shaping the overall structure and content of the interview guide. Furthermore, a focus group including both individuals living with OUD and professionals providing psychosocial support in the Berlin clinic was conducted prior to data collection. During the focus group, the study’s purpose and interview guides were discussed to ensure that the terms and methodology used were non-judgemental, of relevance, and feasible. As this research was inspired by community-based participatory research principles, it included such active discussion with community stakeholders in different stages of the research process to foster positive social change [30].

Recruitment

Participants for the interview study were recruited from two German outpatient iOAT clinics. One clinic, located in Berlin, provides care to 350 patients in oOAT and 103 in iOAT. The other, located in Stuttgart, attends to 260 patients in oOAT and 140 in iOAT. Drawing on the concept of information power [31], we set an initial number of participants to 16 in iOAT and 12 in oOAT (see Table 2). Stratified by age and self-assigned gender to reflect the respective clinics’ clientele, eligible individuals were sampled randomly and invited to participate in the study by the clinics’ staff. Sampled individuals were provided with information about the study and, after clarifying questions, provided written consent. Recruitment was continued until no new themes emerged in the interviews. Throughout this process, we aimed for a deep and nuanced understanding of participants’ experiences rather than exhaustive sampling or definitive saturation. We continuously evaluated the adequacy of the sample size accordingly and finally included 23 participants currently in iOAT. We included only 11 individuals currently in oOAT (of which four had ever received iOAT) in the study because it was not possible to recruit more.

Table 2.

Initially planned and actual number of participants

| Initially planned number of participants | Actual number of participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 28 | 34 |

| Currently in iOAT | 16 | 23 |

| Currently in oOAT, never having been in iOAT | 8 | 7 |

| Currently in oOAT, previously having been in iOAT | 4 | 4 |

Data Collection

Interviews were held in private rooms in the respective clinics between May and August of 2022 at a time convenient for the participants. Interviews were conducted by Author 1, a female medical student trained in qualitative research who was unknown to participants prior to data collection and not involved in their medical care. Before all interviews, Author 1 again explained the study’s purpose, her position, and confidentiality protocols. It was stressed that participation was voluntary and that the decision to take part was independent of participants’ care. Upon written and oral consent, Author 1 audio-recorded the interviews and took field notes. All interviews started with an open question inviting participants to reflect upon their initiation of iOAT and/or oOAT. For this study, all participants in oOAT were asked if and why they would or would not (re)enrol in iOAT. For the complete interview guide, see online supplementary material 1 (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000535416). Interviews ranged from 18 to 61 (mean 32) minutes. After the interviews, participants were debriefed (including an invitation to contact Author 1 for any further thoughts or to obtain transcripts of their interviews) and provided with a compensation of EUR 20. The compensation was self-financed by the research team and was regularly discussed to mitigate potential conflicts of interest arising from this arrangement.

Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim assisted by NVivo transcription software. Author 1 verified the accuracy of each transcript by comparing it to the audio-recordings and de-identified the texts. De-identified transcripts were imported into MaxQDA software (2022) for systematic coding. All data were analysed in German, quotations presented in this article were translated using the forward-backward translation technique by bilingual academics to ensure concurrent validity. Data analysis followed qualitative content analysis in a structured-thematic approach [32, 33], which commenced alongside data collection. It proceeded through the subsequent steps:

Familiarization with the material (repeated close reading and identification of emergent commonalities and differences), inductive establishment of major categories, e.g., “iOAT initiation”

Derivation of subcategories, e.g., on perceptions influencing participants’ treatment initiation

Repeated testing, modification, and revision of the category system including independent coding and discussion of 20% of the transcripts

Coding of the entire material with the finalized category system

Building Analytic Rigour

Author 1 led data analysis and kept a log of all analytical reflections and methodological decisions to facilitate critical reflexivity. To enhance rigour, intersubjective validation was sought throughout the research process. In regular meetings, Author 1 discussed emerging themes and analytical approaches with variable members of the research team. The researchers involved in participants’ medical care only reviewed de-identified illustrative quotes. During the verification meetings, discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached. Furthermore, Author 1 presented the project in all its stages at interdisciplinary interpretation groups and colloquia. To ensure that the interpretations we made aligned with informed lived experiences, we discussed the manuscript for this article with individuals living with OUD. We adhered to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies [34] and provide further information regarding our methods in online supplementary material 2.

Results

Of the 34 cisgender participants, 22 were male and 12 female aged 31 to 59 (mean of 43) years. 31 participants held both positive and negative perceptions and all perceptions reported here were mentioned by participants from both study sites. We present a joint analysis of accounts provided by participants currently in iOAT and oOAT but differentiate in illustrative quotations’ identification (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Key to the presentation of our results

|

Key to identification of quotations: |

|

1–34: participant number |

|

a: participants currently in iOAT |

|

b: participants currently in oOAT, never having received iOAT |

|

c: participants currently in oOAT, having received iOAT in the past |

|

Categories are described as: |

|

Many and most when present in over half of transcripts |

|

Several when present in more than a quarter but less than half of transcripts |

|

Some when present in less than a quarter of transcripts |

The following results are derived from the major category “iOAT initiation.” While some participants initiated iOAT due to factors such as probation conditions, most explained their choice to enrol as a consequence of iOAT’s perceived implications for one’s daily life and individual recovery. In total, three positive, treatment-encouraging and three negative, treatment-deterring perceptions emerged from our analysis as subcategories (Fig. 1). Participants were encouraged to initiate iOAT by the therapy’s perceived potential to reduce craving and substance use, its positive health implications, and the view of iOAT as a path towards abstinence. Regarding factors deterring from iOAT initiation, participants condemned daily clinic visits, perceived iOAT to insufficiently promote or even impede one’s recovery, and feared negative health implications.

Fig. 1.

Relationships between the subcategories guiding this study as described by participants.

Perceived Implications for One’s Daily Life and Recovery Encouraging iOAT Initiation

Many participants initiated treatment because they expected iOAT to improve their daily life and facilitate the reestablishment of social roles and functioning. Participant 7.a describes that in iOAT

… you can really get your life back if you want to. You don’t have to wake up in the morning thinking, “Oh God, how am I going to get the money I need today? How do I get it? Where am I going to get it?” You, you’re just rid of it. It’s just gone and – Yes, that changes your whole life. You can get back into programs again, you can collaborate better in case management, and you can also offer your capacity to work again.

iOAT’s Potential to Reduce Craving and Substance Use

Most participants attributed iOAT’s positive effects on daily life and recovery to the therapy’s potential to reduce craving and the use of licit and illicit substances. Several participants traced the reduction of craving to the (heroin-like) high produced by DAM. Reflecting upon his treatment initiation, 3.a says that

… of course, I did wish a bit that it would have an effect. I mean, that is exactly what is not the case with pola(midone) and meta(done).

Additionally, injecting was seen as an end itself to reduce craving and served as a reason to initiate iOAT for many participants. Emphasizing unsuccessful attempts in oOAT, 6.a states:

6.a: I was quite sure. If anything, it’s this (iOAT). This will work.

Interviewer: Why was that?

6.a: Well, because you-because you can inject it.

Several participants further connected the reduction of craving and substance use in iOAT to the therapy’s potential to end drug-related crime. For 8.a, who felt unsatisfied with the treatment and continued drug-related crime during oOAT

… that was actually the reason why I went into the diamorphine program. Because when you steal, you always get caught, and then you go back to jail.

iOAT’s Positive Health Consequences

Beyond the factors of reduced cravings and the end of drug-related crime as positively influencing one’s daily life and recovery, most respondents reported iOAT’s positive health consequences to encourage enrolment. This regarded aspects such as pain management:

I’m also a pain patient. I have (…) all kinds of things. My knees are f*ed up. Um, I’m kind of curious to see if it (iOAT) could make my life a little better somehow, take away the pain for once. And, uh, also make me a little more stable mentally (23.b).

Furthermore, several participants perceived iOAT to reduce the risk for contracting infectious diseases and develop abscesses. They highlighted the positive implications of quitting the injection of adulterated street drugs and substitutes not suited for injection. 15.a initiated iOAT

… because I always injected my (oral) substitute intravenously, and that’s not really what it’s for, right? And I also got really scared at some point. I just thought, like, that something could happen. So that I could maybe also croak (die) or something. Right. And then I heard about the diamorphine program and so on, and then I discussed it with my wife. And even she thought it was better that here I can just inject everything clean, sterile, and with experts.

iOAT as a Path towards Abstinence

Aspiring to cease all opioid use including OAT, some participants currently in iOAT perceived DAM as a comparatively good way towards complete abstinence, which heavily influenced their decision to enrol. 12.a, reflecting upon his goal to end substitution, describes DAM as the

… best possibility there is right now for junkies or for addicts to get away from it at all.

And 2.a states that

… the withdrawal from pills is really hard and I think that will- I think, I don’t know. But I think that won’t be so hard with the diamorphine.

Perceived Implications for One’s Daily Life and Recovery Deterring from iOAT Initiation

Many participants feared iOAT to negatively impact one’s daily life and participation in mainstream society. Especially participants currently in oOAT felt that people in iOAT

… don’t do anything anymore. So, in their life they really only have the diamorphine and then going home. Diamorphine, then going home. Yes, like no real life anymore (29.b).

Daily Visits to the Clinic

Several participants explained iOAT’s negative implications in relation to the daily visits to the clinic. Participants saw this as profoundly impeding their daily life by depriving them of personal freedom and a sense of normalcy. 28.b is interested in utilizing iOAT

… from time to time but not every day. Never.

She explicates:

Because of going to work. We’re told that it shouldn’t be a problem, but I don’t want to have to rush to the doctor’s first. And I just don’t feel good when I have to follow some schedule. And, no, I- somehow, I can’t reconcile that with myself. (…) I want to be able to start my day normally at home and then go to work normally and go home again or whatever one does then. And not always have to reckon with the doctor as well.

Furthermore, participants held negative perceptions of daily visits due to a social environment they connected to the use of street drugs. 22.a hesitated to initiate iOAT

… because of the people here. I don’t want to see them every day- I didn’t want to see them anymore.

Similarly, 9.a initially did not want to start iOAT and avoids other patients

… because I’m not cured, I can- Yes, when someone puts heroin or something on the table, it’s hard to say no, especially when you have to deal with people like that every day.

iOAT Not Promoting or Impeding Recovery

While participants conveyed varying concepts of “recovery,” many felt that recovery is insufficiently promoted in iOAT. 31.c, who discontinued iOAT and does not want to re-initiate it, criticizes that iOAT

… is just supposed to make people high. Well, it-somehow there is no other way, they go there, inject and then it’s “stop”, but somehow it doesn’t go any further. There’s nothing else beyond that, eh, or something, it’s just there for people to shut down. Without any other reasons somehow.

Beyond a lack of actively promoting recovery, some participants viewed iOAT as a setback in their recovery. They mainly connected this to the intravenous application. 32.c, who dropped out of iOAT, says that he would go back on DAM in oral form but that injecting

… is a point that bothered me. That’s just as if I had taken a step back again. And back to being, well, the druggie who only uses.

Likewise, 13.a explains a lack of interest in iOAT with fears among people living with OUD

… that they will then just relapse because of the needle.

Even in participants who stated that they have overcome their initial reservations and no longer associate iOAT with the use of street heroin, the perception of iOAT as a setback remains prevalent. 10.a, for instance, conceals being in iOAT from her parents because

… they wanted me to get out of the (methadone) program sometime and not, like they think, fall even more into another substitution.

For some participants, considering iOAT as a way “more into substitution” was reinforced by the perception that withdrawing from DAM is harder than from oOAT. 21.a hesitated to initiate iOAT due to the fear

… that you just really become dependent and then maybe you can’t get out anymore. That then it’s just a – like kind of a one-way street. (…) So, I think it’s really difficult to – more difficult than from other things to come off from.

For several participants, the image of iOAT negatively influencing one’s recovery led to the perception that iOAT is a treatment option of last resort or, as 34.a states, a therapy for

… hopeless cases.

Perceiving iOAT as profoundly different from oOAT, participants such as 26.b feel as though iOAT should be only available to individuals

… who are just not treatable anymore.

When asked if she ever thought about starting iOAT, 26.b explains:

I thought about taking it, but, like I said, I’m 36 and I- well, I thought to myself, “this is something for older patients, who already have like a long history of taking drugs.” So, I always thought that, I thought that this is for people who just don’t want to do any more therapies, who have already said “I don’t want to detox and I just accepted it.” And I kept saying to myself “I’m still too young. I still want to, maybe I do want to do therapy. Maybe something will change in my life.”

The negative image of iOAT and the people receiving it influenced some respondents’ reluctance towards the supervised injection. 18.a connects her initial resistance to start iOAT to

… this obvious or, I don’t know, that, that it’s really a fact that you’re a junkie or, I don’t know, that you really can’t avoid hiding it anymore.

Similarly, 17.a explains that he did not want to enrol at first, because

… you are not alone. Other people are around you. The other patients. And the people from the clinic, and everybody sees that and everything.

iOAT’s Negative Health Consequences

A further aspect voiced by many participants regarded iOAT’s negative health consequences. Firstly, psychological side-effects such as psychoses, apathy, and depressions were a common concern. As 27.b explicates:

I don’t want that stuff (DAM), especially since a lot of people get depressed from it. And I have a tendency to depression anyway and that’s why that is simply out of the question for me.

Secondly, physiological consequences deterred many participants from enrolling. These included acute incidences such as convulsions, respiratory depression, and cardiac arrest, but mainly regarded long-term effects of injecting. 24.b states that:

I scary diamorphine. I scary because (…) I have very big problems with legs, with the vein. I already have had an operation because of the bad injection. So I scary. I don’t want, I scary.

Likewise, 19.a reflects that

… injecting is just, even if it’s a solution that is meant to be injected, ramming something into your veins simply can’t be good.

Discussion

This study explored perceptions of iOAT and their impact on treatment initiation in two German outpatient iOAT clinics. Our findings complement previous studies in several ways and contribute to the growing international literature on patients’ perspectives on OAT. One main result is that considerations of initiating treatment were guided by iOAT’s perceived positive and negative implications for one’s daily life and individual recovery. Reinforcing the consistency and transferability of our results, this resonates with findings about the initiation of other OAT [15–19] and with health behaviour theory [35].

The treatment-encouraging perceptions found in the current study align with earlier quantitative and qualitative enquiries on motivations to enter iOAT. Despite the highly variable contexts studied in the past, our research echoes findings on iOAT’s perceived benefits (e.g., the reduction of street heroin use and criminal activities, stabilizing effects, improved health status, and the ability to safely inject opioids) to encourage treatment initiation [21–24, 26, 27]. These motivations closely align with the demonstrated benefits of iOAT in clinical trials [8], underlining the practical relevance of evidence-based education on available OUD treatment [16, 36].

Regarding treatment-deterring perceptions, our results concur with findings from the UK [27], Australia [24], and Belgium [28] in which people living with OUD were reluctant to start iOAT due to the daily supervised application. Procedural factors such as daily visits are known to jeopardize the initiation and maintenance of both oOAT [37] and iOAT [12, 38]. Supplementing iOAT with oral medications can reduce the frequency of visits to the clinic [39]. However, individuals often initiate iOAT particularly because they were not satisfied in oOAT. This questions whether supplementing iOAT with oral substitutes can sufficiently address the negative perceptions related to repeated visits to the clinic and requires practical solutions, e.g., regarding take-home arrangements and flexible dosing policies [40, 41]. This could also assist in combating the negative perception of “having no life anymore” and insufficient engagement in society when in iOAT. Concerningly, this finding resonates with recent qualitative enquiries on iOAT [25, 27].

Furthermore, many participants reported that coexisting encouraging and deterring perceptions produce ambiguity towards treatment initiation. In general, our findings support the past proposition that individuals living with OUD initiate and stay in OAT despite negative perceptions if a treatment’s perceived benefits outweigh them [42]. Conversely, our interviews suggest that people do not enter iOAT because the perceived detriments remain or, in the case of individuals discontinuing iOAT, begin to outweigh the benefits. It would be worthwhile to further investigate how prospective patients who might benefit from iOAT weigh perceived attributes in their decision to initiate treatment. Perhaps quantitative measures could unravel abstract cost-benefit analyses in order to better understand and support individuals in their treatment-seeking journey.

Additionally, perceptions of iOAT’s effect on one’s recovery profoundly influenced treatment initiation but were highly variable among participants in the current study. Interpretations of recovery ranged from complete abstinence from opioids to a more controlled use of illicit substances including heroin. Moreover, recovery encompassed general improvements in health and social functioning as well as specific aspects of daily living such as employment or reconnecting with family. Contrasting concepts of recovery are common [26] and neither the literature on OUD [43] nor iOAT [9] has been able to clearly define the term. In the clinical practice, acknowledging patients’ diverse interpretations of recovery is indispensable for meeting individual needs and aspirations. Our findings highlight the necessity to collaboratively establish realistic treatment and recovery expectations for individuals who could benefit from iOAT and how the treatment can assist them to reach these.

Similarly, contrasting perceptions on iOAT’s health implications featured prominently in our interviews and warrant further scrutiny. While positive health outcomes and side effects such as respiratory depression are known in iOAT [8], there are no data supporting perceptions such as DAM causing severe psychiatric symptoms [44] – rather, the reverse seems to apply [45]. Effects attributed to a substitute by those receiving it are not necessarily related to the substance in question [46]. To adequately respond to individuals’ concerns upon treatment initiation and facilitate informed shared decision-making in iOAT, it must be resolved which perceived health implications can be backed by evidence. And for those effects that cannot be explained, it is crucial to understand how perceptions of them arise.

A final aspect that has to date not sufficiently been considered is the multifaceted stigmatization of iOAT and the individuals receiving it within populations of those living with OUD, which acts as a substantial barrier to treatment engagement [47]. Participants’ accounts of iOAT as a treatment for “hopeless cases” resonate with medical and policy perspectives of iOAT as an exceptional “last resort” [48] suitable only for a “minority group of patients” meeting strict eligibility criteria [49, 50]. However, this is neither supported by medical evidence nor an established consensus. Mixed views about who qualifies for iOAT prevail among individuals living with OUD [24, 51] and in academic discourses [52]. Despite currently not being a first-line treatment, it is imperative to clearly communicate that iOAT is not a therapy exclusively for “hopeless cases.” Otherwise, inner- and inter-group stigmatization might impede its expansion indefinitely [53]. Evidence on effective stigma reduction in OAT is scarce [18]. Nevertheless, community engagement and educational campaigns among individuals living with OUD, healthcare providers, and the broader public would likely aid to challenge the misconceptions found in this study and promote a more supportive environment for individuals considering iOAT [54]. Overall, our findings underscore that efforts to successfully implement iOAT must target individual perceptions, programme characteristics, and structural factors alike [12, 55, 56]. We invite future research to further explore the psychological and social factors that mediate between perceptions and health behaviours in OAT.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is its study population. By including people who discontinued iOAT, we add perspectives on potential re-enrolment which were not considered in previous research. Additionally, because all participants were eligible for iOAT, our study can address real-life situations. Furthermore, by focusing on persons currently in treatment, we can “filter out” perceptions influencing the initiation of OAT in general and specifically examine iOAT.

Including only individuals currently in treatment might limit transferability to those out of care. There is, however, a considerable overlap between in- and out-of-treatment populations and several participants had previously transitioned out of both oOAT and iOAT into phases of abstinence and/or to the use of street drugs before re-initiating therapy. We thus assume that, to a certain extent, the participants in this study can speak to experiences of individuals currently not in treatment. Transferability is further supported by the coherence of perceptions reported in Stuttgart and Berlin and the overlap we found with results from international studies. Yet, because iOAT is currently only available in urban areas in Germany, the transferability to rural settings remains questionable.

The study population currently in oOAT was underrepresented compared to participants currently in iOAT, which might bias our results towards positive perceptions. However, since quantitative analyses were not our aim and participants currently in iOAT were able to express negative perceptions about treatment, the importance of differing sample sizes is minimized. Additionally, although underrepresented, the sample size of individuals in oOAT in this study corresponds to those common in qualitative research [57]. Another possible bias stems from the influence of socially desirable responding. Despite highlighting that there are no right or wrong answers, the interviewer not being professionally active in addiction medicine and avoidance of leading questions, the social desirability effect presumably influenced participants’ responses in interviews and during member checking. Additionally, all interview data are prone to recall biases and accounts of iOAT initiation lying in the past were likely influenced by subsequent experiences.

While enhancing the reach of this research, the decision to present our results in English brings certain limitations. Some subtle meanings and cultural elements may have been altered or lost during the translation process. This could potentially affect the richness and depth of the data. To minimize this risk and produce an English version that closely aligns with the original German data, we deployed forward-backward translation and discussed all decisions during the translation process within and outside of the research team [58]. Finally, we exclusively conducted interviews, and additional qualitative methods (particularly ethnographic work) might have enriched the conclusions reached in this study.

Conclusions

iOAT’s perceived implications for one’s daily life and recovery profoundly shape decisions about treatment initiation. Thus, the complex interaction of positive and negative, often conflicting perceptions must be considered in efforts to adequately expand iOAT and avoid compounding stigma. Our findings can inform public health campaigns and medical professionals’ daily practice alike. Simultaneously, we encourage further exploration and point to several avenues for future research. Only by addressing questions about the ambivalences found in the current study can we accurately present available options upon treatment initiation and achieve the best possible outcome for each individual.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in this study for sharing their time and experiences with us. We also thank Paula Tigges for her research assistance during independent coding.

Statement of Ethics

We conducted our research in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of Landesärztekammer Baden-Württemberg (file number F-2022-002). All participants gave their informed written and verbal consent to participate in the study. We can provide additional information on our application and approval upon request.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships, which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Zoe Friedmann: financial and non-monetary stipend from Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes (scholarship programme from the German government).

Annette Binder: member of Deutsche Gesellschaft für Suchtforschung und Suchttherapie e.V. (German Society for Addiction Research and Addiction Therapy); medical residency in addiction medicine at Medical University Hospital Tuebingen.

Hans-Tilmann Kinkel: medical head and director of an outpatient clinic for addiction medicine (Praxiskombinat Neubau Berlin); speaker’s fees from Accente BizzComm GmbH, AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, and GILEAD Sciences GmbH; conference travel and attendance fees from GILEAD Sciences GmbH.

Claudia Kühner: psychologist at an outpatient clinic for addiction medicine (Schwerpunktpraxis für Suchtmedizin Stuttgart).

Andreas Zsolnai: medical head and director of an outpatient clinic for addiction medicine (Schwerpunktpraxis für Suchtmedizin Stuttgart).

Inge Mick: senior physician in general adult psychiatry (including care for addictive behaviours) at Charité Berlin.

Funding Sources

The study was self-financed by the research team and did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

Zoe Friedmann, Hans-Tilmann Kinkel, Andreas Zsolnai, Claudia Kühner, and Inge Mick conceptualized the current study. Zoe Friedmann, Annette Binder, and Inge Mick led data analysis. Zoe Friedmann prepared the original draft for this article, which was revised and edited by all authors. All authors approved the final manuscript. Contributions following CRediT: Zoe Friedmann – conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis (lead), investigation (lead), methodology, project administration (lead), visualization (lead), writing – original draft preparation (lead), and writing – review and editing; Annette Binder – methodology, formal analysis, supervision, visualization, and writing – review and editing; Hans-Tilmann Kinkel – conceptualization (lead), project administration, resources, supervision, and writing – review and editing; Andreas Zsolnai – conceptualization, resources, and writing – review and editing; Claudia Kühner – conceptualization, project administration, resources, and writing – review and editing; and Inge Mick – conceptualization, validation, supervision (lead), and writing – review and editing. Research support: Paula Tigges – formal analysis and validation.

Funding Statement

The study was self-financed by the research team and did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. Anonymized data can be made available from the corresponding author Z.F. upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. UNODC . World drug report 2022. United Nations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M, Vecchi S. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(10):Cd004147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strang J, Volkow ND, Degenhardt L, Hickman M, Johnson K, Koob GF, et al. Opioid use disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bell J. Pharmacological maintenance treatments of opiate addiction. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(2):253–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nordt C, Vogel M, Dey M, Moldovanyi A, Beck T, Berthel T, et al. One size does not fit all-evolution of opioid agonist treatments in a naturalistic setting over 23 years. Addiction. 2019;114(1):103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Timko C, Schultz NR, Cucciare MA, Vittorio L, Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: a systematic review. J Addict Dis. 2016;35(1):22–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bell J, Belackova V, Lintzeris N. Supervised injectable opioid treatment for the management of opioid dependence. Drugs. 2018;78(13):1339–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strang J, Groshkova T, Uchtenhagen A, van den Brink W, Haasen C, Schechter MT, et al. Heroin on trial: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials of diamorphine-prescribing as treatment for refractory heroin addiction. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(1):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haines M, O’Byrne P. Injectable opioid agonist treatment: an evolutionary concept analysis. Res Nurs Health. 2021;44(4):664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roy M, Bleich S, Hillemacher T. Diamorphingestützte substitution. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2016;84(03):164–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bundesärztekammer . Richtlinie der Bundesärztekammer zur Durchführung der substitutionsgestützten Behandlung Opioidabhängiger. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Friedmann Z, Kinkel H-T, Kühner C, Zsolnai A, Mick I, Binder A. Supervised on-site dosing in injectable opioid agonist treatment-considering the patient perspective. Findings from a cross-sectional interview study in two German cities. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schäffler F, Foot E. Vier Jahre Diamorphinvergabe in der Regelversorgung - bestandsaufnahme aus Konsumenten- und Expertenperspektive: eine qualitativ-heuristische Studie. Akzeptanzorientierte Drogenarbeit/Acceptance-Oriented Drug Work. 2014;11:131–47. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bühring P. Diamorphingestützte substitutionsbehandlung: die tägliche spritze. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(1–2). A-16-A-19. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cioe K, Biondi BE, Easly R, Simard A, Zheng X, Springer SA. A systematic review of patients’ and providers’ perspectives of medications for treatment of opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;119:108146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hall NY, Le L, Majmudar I, Mihalopoulos C. Barriers to accessing opioid substitution treatment for opioid use disorder: a systematic review from the client perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liberman AR, Bromberg DJ, Azbel L, Rozanova J, Madden L, Meyer JP, et al. Decisional considerations for methadone uptake in Kyrgyz prisons: the importance of understanding context and providing accurate information. Int J Drug Pol. 2021;94:103209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Madden E, Prevedel S, Light T, Sulzer SH. Intervention stigma toward medications for opioid use disorder: a systematic review. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56(14):2181–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sharp A, Carlson M, Howell V, Moore K, Schuman-Olivier Z. Letting the sun shine on patient voices: perspectives about medications for opioid use disorder in Florida. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;123:108247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ratz T, Lippke S. 8.06 - health behavior change. In: Asmundson GJG, editor. Comprehensive clinical psychology. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2022. p. 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sell L, Zador D. Patients prescribed injectable heroin or methadone – their opinions and experiences of treatment. Addiction. 2004;99(4):442–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nosyk B, Geller J, Guh DP, Oviedo-Joekes E, Brissette S, Marsh DC, et al. The effect of motivational status on treatment outcome in the North American Opiate Medication Initiative (NAOMI) study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111(1–2):161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Groshkova T, Metrebian N, Hallam C, Charles V, Martin A, Forzisi L, et al. Treatment expectations and satisfaction of treatment-refractory opioid-dependent patients in RIOTT, the Randomised Injectable Opiate Treatment Trial, the UK’s first supervised injectable maintenance clinics. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(6):566–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nielsen S, Sanfilippo P, Belackova V, Day C, Silins E, Lintzeris N, et al. Perceptions of injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT) among people who regularly use opioids in Australia: findings from a cross-sectional study in three Australian cities. Addiction. 2021;116(6):1482–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mayer S, Boyd J, Fairbairn N, Chapman J, Brohman I, Jenkins E, et al. Women’s experiences in injectable opioid agonist treatment programs in Vancouver, Canada. Int J Drug Pol. 2023;117:104054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mayer S, Fowler A, Brohman I, Fairbairn N, Boyd J, Kerr T, et al. Motivations to initiate injectable hydromorphone and diacetylmorphine treatment: a qualitative study of patient experiences in Vancouver, Canada. Int J Drug Pol. 2020;85:102930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Riley F, Harris M, Poulter HL, Moore HJ, Ahmed D, Towl G, et al. “This is hardcore”: a qualitative study exploring service users’ experiences of Heroin-Assisted Treatment (HAT) in Middlesbrough, England. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Demaret I, Litran G, Magoga C, Deblire C, Dupont A, Roubaix J, et al. Why do heroin users refuse to participate in a heroin-assisted treatment trial? Heroin addiction and related clinical problems. 2014. Epub ahead of print, March 22, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fountain J. Understanding and responding to drug use: the role of qualitative research. Office for official publications of the European communities Luxembourg; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vaughn LM, Jacquez F. Participatory research methods – choice points in the research process. J Participatory Res Methods. 2020;1(1):2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schreier M. Ways of doing qualitative content analysis: disentangling terms and terminologies. Forum Qual Sozialforschung/Forum Qual Soc Res. 2014;15(1). [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kuckartz U, Rädiker S. Qualitative inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, praxis, computerunterstützung. Beltz Juventa; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Archambault L, Goyer MÈ, Sabetti J, Perreault M. Implementing injectable opioid agonist treatment: a survey of professionals in the field of opioid use disorders. Drugs Educ Prev Pol. 2022;30(4):434–42. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Frank D, Mateu-Gelabert P, Perlman DC, Walters SM, Curran L, Guarino H. It’s like “liquid handcuffs”: the effects of take-home dosing policies on Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) patients’ lives. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marchand K, Palis H, Guh D, Lock K, MacDonald S, Brissette S, et al. A multi-methods and longitudinal study of patients’ perceptions in injectable opioid agonist treatment: implications for advancing patient-centered methodologies in substance use research. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;132:108512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bell J, Waal RV, Strang J. Supervised injectable heroin: a clinical perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(7):451–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oviedo-Joekes E, MacDonald S, Boissonneault C, Harper K. Take home injectable opioids for opioid use disorder during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic is in urgent need: a case study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Pol. 2021;16(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ellefsen R, Wüsthoff LEC, Arnevik EA. Patients’ satisfaction with heroin-assisted treatment: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Muthulingam D, Bia J, Madden LM, Farnum SO, Barry DT, Altice FL. Using nominal group technique to identify barriers, facilitators, and preferences among patients seeking treatment for opioid use disorder: a needs assessment for decision making support. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;100:18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hooker SA, Sherman MD, Lonergan-Cullum M, Nissly T, Levy R. What is success in treatment for opioid use disorder? Perspectives of physicians and patients in primary care settings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;141:108804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dürsteler-MacFarland KM, Fischer DA, Mueller S, Schmid O, Moldovanyi A, Wiesbeck GA. Symptom complaints of patients prescribed either oral methadone or injectable heroin. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38(4):328–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schäfer I, Eiroa-Orosa FJ, Verthein U, Dilg C, Haasen C, Reimer J. Effects of psychiatric comorbidity on treatment outcome in patients undergoing diamorphine or methadone maintenance treatment. Psychopathology. 2010;43(2):88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dürsteler-MacFarland KM, Stohler R, Moldovanyi A, Rey S, Basdekis R, Gschwend P, et al. Complaints of heroin-maintained patients: a survey of symptoms ascribed to diacetylmorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(3):231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McCradden MD, Vasileva D, Orchanian-Cheff A, Buchman DZ. Ambiguous identities of drugs and people: a scoping review of opioid-related stigma. Int J Drug Pol. 2019;74:205–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fischer B, Oviedo-Joekes E, Blanken P, Haasen C, Rehm J, Schechter MT, et al. Heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) a decade later: a brief update on science and politics. J Urban Health. 2007;84(4):552–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Farrell M, Hall W. Heroin-assisted treatment: has a controversial treatment come of age? Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(1):3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mielau J, Vogel M, Gutwinski S, Mick I. New approaches in drug dependence: opioids. Curr Addict Rep. 2020;8(2):298–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fischer B, Chin AT, Kuo I, Kirst M, Vlahov D. Canadian illicit opiate users’ views on methadone and other opiate prescription treatment: an exploratory qualitative study. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37(4):495–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Haasen C, Verthein U, Eiroa-Orosa FJ, Schäfer I, Reimer J. Is heroin-assisted treatment effective for patients with no previous maintenance treatment? Results from a German randomised controlled trial. Eur Addict Res. 2010;16(3):124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schwartz RP, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Mitchell SG, Peterson JA, Reisinger HS, et al. Attitudes toward buprenorphine and methadone among opioid-dependent individuals. Am J Addict. 2008;17(5):396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Watson E. The mechanisms underpinning peer support: a literature review. J Ment Health. 2019;28(6):677–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Silva TC, Andersson FB. The “black box” of treatment: patients’ perspective on what works in opioid maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Pol. 2021;16(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Englander H, Gregg J, Levander XA. Envisioning minimally disruptive opioid use disorder care. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;38(3):799–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Epstein J, Santo RM, Guillemin F. A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(4):435–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. Anonymized data can be made available from the corresponding author Z.F. upon reasonable request.