Abstract

Objectives

Clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia (TI), is the medical behaviour of not initiating or intensifying treatment when recommended by clinical recommendations. To our knowledge, our survey is the first to assess TI around psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Methods

Eight hundred and twenty-five French rheumatologists were contacted via email between January and March 2021 and invited to complete an online questionnaire consisting of seven clinical vignettes: five cases (‘oligoarthritis’, ‘enthesitis’, ‘polyarthritis’, ‘neoplastic history’, ‘cardiovascular risk’) requiring treatment OPTImization, and two ‘control’ cases (distal interphalangeal arthritis, atypical axial involvement) not requiring any change of treatment—according to the most recent PsA recommendations. Rheumatologists were also questioned about their routine practice, continuing medical education and perception of PsA.

Results

One hundred and one rheumatologists completed this OPTI’PsA survey. Almost half the respondents (47%) demonstrated TI on at least one of the five vignettes that warranted treatment optimization. The complex profiles inducing the most TI were ‘oligoarthritis’ and ‘enthesitis’ with 20% and 19% of respondents not modifying treatment, respectively. Conversely, clinical profiles for which there was the least uncertainty (‘polyarthritis in relapse’, ‘neoplastic history’ and ‘cardiovascular risk’) generated less TI with 11%, 8% and 6% of respondents, respectively, choosing not to change the current treatment.

Conclusion

The rate of TI we observed for PsA is similar to published data for other chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, gout or multiple sclerosis. Our study is the first to show marked clinical inertia in PsA, and further research is warranted to ascertain the reasons behind this inertia.

Keywords: PsA, clinical inertia, therapeutic inertia, clinical vignettes, recommendations, treat-to-target, uncertainty, medical education

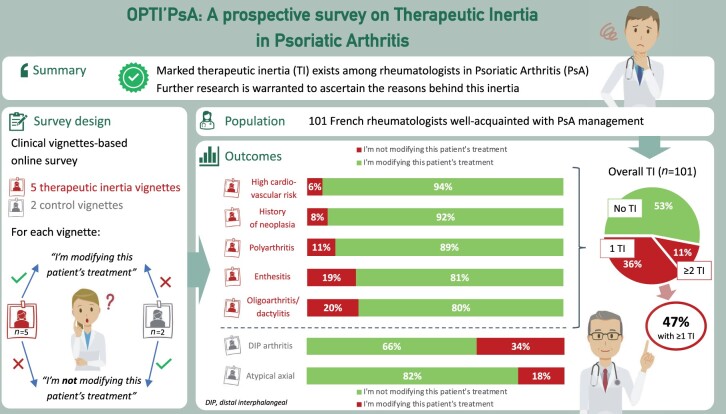

Graphical Abstract

Rheumatology key messages.

Therapeutic inertia (TI) impairs medical management and is mostly caused by physician behaviour.

Overall, 47% of 101 French rheumatologists demonstrated TI based on clinical vignettes in psoriatic arthritis.

Besides TI, decision uncertainty might also be due to heterogeneity of PsA phenotypes and comorbidities.

Introduction

PsA is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease managed by rheumatologists. Its prevalence is between 0.05 and 0.3% of the general population (0.1% in France, with an incidence of 8.4 per 100 000 person-years), regardless of gender, with a much higher frequency among patients with psoriasis, including nail involvement [1, 2]. Up to 40% of patients with psoriasis will develop PsA, usually within 5–10 years of the onset of skin disease [3]. PsA can present with axial involvement as observed in axial spondyloarthritis. However peripheral involvement of PsA is more frequent and heterogeneous: mono/oligoarticular, polyarticular, symmetrical or asymmetrical. Enthesitis and dactylitis are also often associated [4].

With growing recognition of the burden of the disease, and with the increasing number of therapeutic options, treatment strategies have evolved in recent years. European and international guidelines [5–8], as well as the recently updated French guidelines [9], support the use of a treat-to-target approach in PsA. Guidelines also support tight disease control [10]. However, implementation of the recommended approach in routine practice is low, leading to a general tendency for patients to be undertreated [11, 12].

Clinical inertia or therapeutic inertia (TI) is chiefly the medical behaviour of not initiating or intensifying, adapting or modifying a patient's management when current recommendations justify it in the absence of medico-economic barriers [13–16]. According to the literature, TI is measured by the deviation of management from therapeutic objectives of existing recommendations [13, 17–19]. TI is not necessarily detrimental, for example when a practitioner postpones initiation or intensification of treatment to a more appropriate time or in order to preserve a patient's quality of life [20]. However, TI can become detrimental by the repetition of these acts of under-treatment or non-treatment, i.e. when a physician's inertia behaviour is constant over time. In these situations of TI, the burden of disease can lead to irreversible or even fatal lesions—as seen in diabetes mellitus [21–23] and arterial hypertension [15, 24, 25].

According to studies, TI affects 30–70% of physicians caring for patients with chronic diseases [16, 26]. TI was initially studied in diabetes mellitus [21–23], hypertension [15, 24, 25], certain chronic inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS) [19, 26–28] gout [29–31] and, more recently, psoriasis [32–34].

Reasons for TI can be classified into three categories: those due to the physician (time constraints, under-assessment of patients' needs, concern about a patient's ability to be compliant, lack of up-to-date knowledge, lack of experience, etc.), those due to the patient (denial of the disease, apprehension from a change in treatment, fear of adverse effects, feeling of failure in the face of the chronic nature of the disease, loss of confidence) or those due to the health care system (lack of registry, delay in appointments, lack of communication between the different stakeholders in a patient’s management) [17, 32]. Whilst TI is a complex behaviour, physician-related factors are considered its main contributors [18, 27].

In order to assess the level of TI in PsA and to understand, without stigma, the reasons that lead a physician–patient pair to not follow recommendations relating to disease-modifying treatments [18], we initiated this quantitative and qualitative study with a population of French rheumatologists.

Methods

Scientific committee

A Scientific Committee consisting of five French rheumatologists (three university hospital based-consultants, one hospital consultant, one practitioner with mixed practice—private and hospital-based) first met in September 2020 to analyse existing literature, share their expertise and experiences, and reflect on a method for evaluating TI in PsA management.

Clinical vignettes

A clinical vignette methodology has been shown to be useful in the evaluation of care processes in real-world clinical practice [35]; its value has been reported in several surveys and studies on TI [19, 26, 36]. It consists of asking healthcare professionals to position themselves in different clinical situations in order to evaluate their behaviour. This type of survey is not related to controlled trial and there is no need for ethics committee approval.

Seven clinical cases illustrating common situations in clinical practice, and reflecting the polymorphous nature of PsA, were designed by the Scientific Committee (Supplementary Data S1 and S2, available at Rheumatology online). All committee members wrote at least one vignette each (two members wrote two each), which were then shared and discussed together during a face-to-face meeting, and amended where necessary for clarity and consistency. Members have made the decision by consensus to consider individual vignettes either for ‘treatment modification’ or for ‘no treatment modification’:

five clinical cases that would require treatment optimization according to current recommendations: profile ‘enthesitis’; profile ‘oligoarthritis/dactylitis’; profile ‘polyarthritis’; profile ‘high cardiovascular risk’; profile ‘neoplastic history’;

two ‘control’ clinical cases that would not require treatment adaptation according to current recommendations: profile ‘distal interphalangeal (DIP) arthritis/nail involvement’; profile ‘atypical axial involvement’.

For each vignette, the following two answers were proposed: ‘I modify the treatment’ or ‘I do not modify the treatment’, without further indications. The treatment modification could therefore be of any sort. The Scientific Committee defined TI as the absence of adaptation or modification of treatment when the clinical situation required it according to the 2019 EULAR [37] and/or 2018 SFR [38] recommendations.

Practice and perceptions questionnaire

In addition to the seven clinical vignettes, rheumatologists were asked to answer a series of 17 closed questions to collect information on their mode of medical practice, their sources of continuing medical education (CME), and their practice and perceptions regarding the management of PsA.

In line with previous studies published on the subject [26, 32], the aim of these additional questions—which did not mention the term ‘inertia’—was to identify possible explanatory factors for TI.

Recruitment of participants

Between January and March 2021, 825 French rheumatologists were contacted via email by the research company APLUSA and invited to complete an online questionnaire (Supplementary Data S3, available at Rheumatology online). To be eligible, they had to manage a minimum of five patients with PsA in their practice. The objective was to include 100 rheumatologists of varying practice types—(i) hospital, (ii) private practice, and (iii) mixed practice—in order to analyse the attitudes of each subpopulation. Recruitment was stratified into groups and balanced by practice type (1:1:1). Active participants gave their signed informed consent and were paid a participation fee by APLUSA.

Data analysis

The results were described by their numbers and percentages for the qualitative variables, and by their means, medians and ranges for the quantitative variables. Statistical adjustment took into account the national distribution of French rheumatologists (hospital-based 32%, private practice 41% and mixed practice 22%) [39].

A univariate statistical analysis was performed according to Student’s t-test for quantitative variables, and according to the χ2 test for qualitative variables at the significance threshold of P ≤ 0.05. The data review was completed by subgroup analyses according to TI attitude (at least one inertia facing the five vignettes requiring optimization of treatment). A linear discriminant multivariate analysis was performed on the entire data set to predict an individual's position in a predefined class (group) based on their responses to the questionnaire.

Results

Profile of respondents

Between 21 January and 4 March 2021, 101 rheumatologists responded to the online questionnaire giving a response rate of 12% (Supplementary Data S4 and S5, available at Rheumatology online). The characteristics of the respondents are detailed in Table 1. The majority were male (60%), aged between 46 and 60 years (45%), with exclusively hospital-based (34%), exclusively private (33%) or mixed (34%) practice, and an average experience of 23 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents

| Characteristic | Value (n = 101) |

|---|---|

| Age, % | |

| ≤45 years | 24 |

| 46–60 years | 45 |

| >60 years | 32 |

| Gender F/M, % | 40/60 |

| Distribution by type of practice, % | |

| Exclusively hospital-based | 34 |

| Exclusively private | 33 |

| Mixed practice | 34 |

| Duration of practice, mean; median (range), years | 23; 26 (2–41) |

| Region, % | |

| Hauts de France/Grand Est/Bourgogne-Franche Comté | 14 |

| Île-de-France | 26 |

| Auvergne Rhône Alpes/PACA | 34 |

| Occitanie/Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 15 |

| Bretagne/Normandie/Centre Val de Loire/Pays de Loire | 12 |

| Participation in international, national and regional conferences over the last 2 years, % | |

| Attended at least one of the three types of conference | 91 |

| Followed up communications on PsA from at least one of the three types of conference | 72 |

| Did not attend or follow communications at any of the three types of conference | 3 |

PACA: Provence–Alpes–Côte d’Azur.

Level of therapeutic inertia

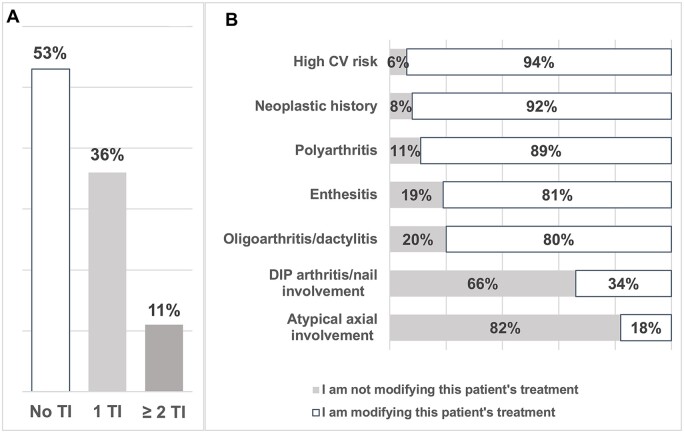

Overall, 47% of responding rheumatologists demonstrated TI at least once out of the five vignettes that warranted a treatment adjustment or modification according to the previously stated recommendations. In detail, 7% demonstrated TI twice, 3% three times and 1% five times (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Therapeutic inertia in relation to psoriatic arthritis patient profiles in clinical vignettes. (A) Overall results (n = 101): distribution of participants according to the number of vignettes in which they demonstrated TI. (B) Results per clinical vignette (n = 101) according to the five profiles requiring a change in treatment (assessment of TI): ‘enthesitis’; ‘oligoarthritis/dactylitis’; ‘polyarthritis’; ‘high CV risk’; ‘neoplastic history’; and the two profiles not requiring a change in treatment (controls): ‘atypical axial involvement’; ‘DIP arthritis/nail involvement’. TI: therapeutic inertia; CV: cardiovascular; DIP: distal interphalangeal joints

The vignette profiles that induced the most inertia were: profile ‘oligoarthritis/dactylitis’ and profile ‘enthesitis’, with 20% and 19% of respondents, respectively, not modifying treatment (Fig. 1B). Conversely, vignettes ‘polyarthritis’, ‘neoplastic history’ and ‘high cardiovascular risk’ generated fewer TIs with 11%, 8% and 6% of respondents, respectively, saying that they would not change treatment.

For the control vignettes, 34% and 18% of rheumatologists surveyed said they would change treatment of vignettes ‘DIP arthritis/nail involvement’ and ‘atypical axial involvement’, respectively, even though the description did not justify treatment modification according to current recommendations.

Rheumatologists' practices and perceptions of PsA management

Almost all surveyed rheumatologists declared themselves ‘comfortable’ with the management of PsA (99% of total or overall agreement) (Supplementary Data S6, available at Rheumatology online).

According to these rheumatologists, they were familiar with the French (2018 SFR) and European (2019 EULAR) recommendations (90% of total or overall agreement), they agreed with them (89% of total or overall agreement), recommendations were applied as often as possible (87% of total or overall agreement), and they considered that a delay in management was detrimental to a patient's prognosis (93% of total or overall agreement).

Nevertheless, respondents generally agreed that there were certain difficulties inherent to this disease: difficult-to-achieve treatment goals (74% of total or overall agreement); disease polymorphism making it difficult to assess effectiveness of a treatment (72% of total or overall agreement); and treatment options quickly exhausted (53% of total or overall agreement). Also, a significant proportion reported using an assessment score (DAS, disease activity index for psoriatic arthritis [DAPSA], minimal disease activity [MDA]) on a daily basis (69% of total or overall agreement) (Supplementary Data S7, available at Rheumatology online).

Factors explaining therapeutic inertia

To identify factors that might explain TI in PsA, an analysis of responses was performed between the two subgroups of respondents who demonstrated TI on at least one vignette (n = 47) and those who did not demonstrate TI on any vignette (n = 54) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of rheumatologists according to their level of therapeutic inertia

| Total (n = 101) | At least 1 TI (n = 47) | No TI (n = 54) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice, % | ||||

| Exclusively hospital-based | 34 | 21 | 44 | <0.05 |

| Exclusively private | 33 | 47 | 20 | <0.05 |

| Mixed practice | 34 | 32 | 35 | NS |

| Duration of practice, years | 23 | 25 | 21 | <0.05 |

| Number of managed patients, mean | ||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 134 | 122 | 145 | NS |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 61 | 56 | 66 | NS |

| Osteoarthritis | 407 | 483 | 340 | <0.05 |

| Time to access an appointment, mean; median (range), days | 52.5; 45 (2–180b) | 36.0; 30 (2–150b) | 67.0; 60 (10–180b) | <0.05 |

| Participation in international, national and regional conferences, % | ||||

| Attended at least one of the three types of conference | 91 | 87 | 94 | NS |

| Followed up communications from at least one of the three types of conference | 72 | 81 | 65 | NS |

| Did not attend or follow the communications at any of the three types of conferences | 3 | 6 | 0 | NS |

Characteristics of the two subgroups of respondents who demonstrated TI on at least one vignette (n = 47) and those who did not demonstrate TI (n = 54).

P-value for inter-group difference with TI attitude vs no TI.

There was no significant difference between the max values. NS: not significant; TI: therapeutic inertia.

Univariate analysis

In a univariate analysis, TI was significantly more frequent in rheumatologists with an exclusive private practice: 47% in the ‘at least one TI’ group vs 20% in the ‘no TI’ group (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 2). Conversely, respondents with an exclusive hospital-based practice were more likely to modify treatment when necessary: 44% in the ‘no TI’ group vs 21% in the ‘at least one inertia’ group (P ≤ 0.05).

Rheumatologists more inclined to TI were more experienced (25 vs 21 years; P ≤ 0.05), had a greater number of patients with osteoarthritis (483 vs 340; P ≤ 0.05), and had a shorter mean time for patients to access a consultation appointment than their colleagues who did not demonstrate TI (36 vs 67 days; P ≤ 0.05).

Regarding other criteria (self-declaration), such as physician gender, average consultation time, knowledge of management recommendations, number of PsA patients, participation in national or international congresses, or reading of scientific articles on PsA, there was no significant difference between the subgroups ‘at least one TI’ and ‘no TI’.

Linear discriminant analysis

The error rate was 15%, meaning that 85% of rheumatologists were well distributed according to this predictive model. A total of 11 criteria distinguished rheumatologists who demonstrated TI on at least one vignette (n = 47) from those who did not demonstrate TI on any vignette (n = 53) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Inertia/non-inertia predictive model by linear discriminant analysis

| Non-inerts | Inerts | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I agree with the French (SFR 2018) and/or European (EULAR 2019) recommendations regarding the management of psoriatic arthritis ≥9 | × | 0.0005 | |

| 2 | Time to access a consultation appointment ≥90 days | × | 0.0017 | |

| 3 | For patients with psoriatic arthritis, teleconsultation can be an alternative to face-to-face follow-up ≥7 | × | 0.0012 | |

| 4 | Number of patients with osteoarthritis ≥500 | × | 0.0035 | |

| 5 | In psoriatic arthritis, a delay in management has a negative effect on patient's prognosis ≥9/10 | × | 0.0047 | |

| 6 | Number of patients with psoriatic arthritis ≤40 | × | 0.0087 | |

| 7 | Presence of comorbidities—rarely (cause of inertia) | × | 0.0114 | |

| 8 | Lack of time in consultation—very rarely (cause of inertia) | × | 0.0203 | |

| 9 | Fear that the new treatment will be less well tolerated than the current treatment—frequently (cause of inertia) | × | 0.0317 | |

| 10 | Attended and followed the communications of any International Congress | × | 0.0325 | |

| 11 | Interest level for osteoarthritis ≥9/10 | × | 0.0964 |

SFR: Société Française de Rhumatologie.

A high level of agreement (≥9/10) with the French (SFR 2018) and 2018 EULAR recommendations for the management of PSA and a delay in access to a consultation appointment ≥90 days were factors of lower TI. A large number of patients followed for osteoarthritis, a low number of patients followed for PsA, and, conversely, the fear that a new treatment would be poorly tolerated were factors for a higher TI. A strong belief in patient harm if management was delayed and high attendance at international conferences were associated with TI in our model.

Explanations provided by respondents

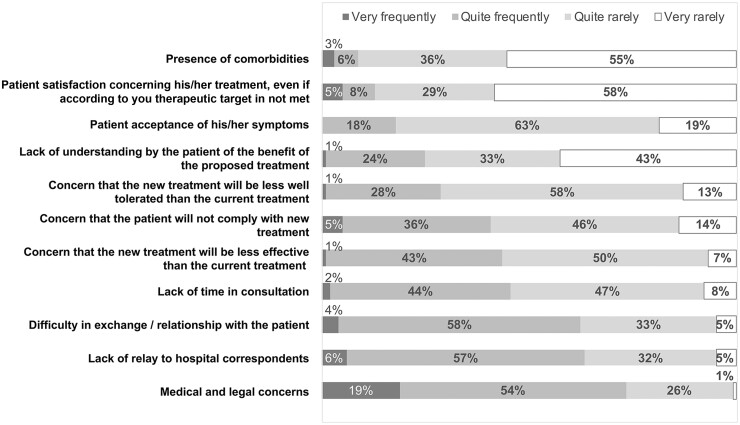

Our questionnaire identified some perceived causes of TI: comorbidities (72% ‘completely agree’ or ‘somewhat agree’), patient satisfaction with current treatment even if the objective set with the rheumatologist was not achieved (63% ‘completely agree’ or ‘somewhat agree’), and patient acceptance of (residual) symptoms (62% ‘completely agree’ or ‘somewhat agree’) were the main reasons reported. On the other hand, several elements were not considered by respondents as factors affecting TI: medical/legal fears (9% ‘completely agree’ or ‘mostly agree’); lack of hospital support (13% ‘completely agree’ or ‘mostly agree’); difficulty in the exchange with the patient (18% ‘completely agree’ or ‘mostly agree’) or lack of time in the patient consultation (25% ‘completely agree’ or ‘mostly agree’) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Factors for not changing the treatment of inadequately controlled PsA patients. Frequency of different reasons. Perceived causes of TI declared by respondants for not changing treatment in patients with poorly controlled PsA. TI: therapeutic inertia

Discussion

In our survey of 101 French rheumatologists of varying practice type on the management of PsA, the level of TI observed was 47%: 36% for one clinical vignette out of five, and 11% for at least two clinical vignettes out of five. In a univariate analysis, the level of TI was related to treating patients from an exclusively private practice, a slightly longer duration of practice, a greater number of patients followed for osteoarthritis, and a shorter average time to access a consultation appointment. In a linear discriminant multivariate analysis, type of practice and experience were no longer explanatory of TI. By contrast, lower adherence to guidelines, low number of managed patients with PsA, fear that a new treatment would be poorly tolerated and also, surprisingly, a strong belief in patient harm if management was delayed, and participation in international congresses were factors for a higher TI.

The 47% of TIs observed in our study on PsA are in the average range of that observed in other chronic diseases: 30–50% in diabetes [21, 40], 37–46% in hypertension [25, 41], 36% in plaque psoriasis [32], 40–60% in gout [29–31] or 60% in MS [26]. Our study is, to our knowledge, the first to look at TI in PsA. However, our results echo those of a recent study [42] that showed, in an observational cohort of 116 PsA patients, that 40 (34%) of them did not have a treat-to-target strategy implemented. This lack of implementation was due to physicians neglecting the patient-reported outcomes components and placing too much emphasis on the ‘objective’ components of the scores.

The profiles that generated the least number of TIs in our study were those for which there was the most certainty: comorbidities and polyarticular involvement; in contrast, the more complex profiles such as dactylitis, oligoarthritis and enthesitis generated more TI. This could be explained by the difficulty in objectively assessing the severity of joint involvement in these latter situations despite the existence of recommendations in, for example, enthesitis, dactylitis and nail involvement [43]. The level of uncertainty, but also a physician’s lower risk-taking profile, has been observed as a factor of TI in the management of other conditions, such as MS [19].

In our study, the presence of ‘control’ vignettes, inspired by other equivalent studies [26, 36], was not intended to measure the tendency to overtreat. Similarly, this method allowed us to limit excessive iteration of unbalanced patients in the questionnaire. This would, therefore, guarantee robustness of the TI measurement due to the absence of a difference in intervention on the control vignettes. Analysis of responses to these two control vignettes showed that there was no difference between the ‘inert’ and ‘non-inert’ respondents who expressed their wish to modify the treatment—contrary to the recommendations—in 40% and 43% of cases, respectively.

Regarding the frequency of reasons for not changing treatment, even in cases where PsA was insufficiently controlled, respondents cited the presence of comorbidities, a patient's relative satisfaction with their treatment, and a patient's acceptance of symptoms. This result might reflect the good quality of the doctor–patient relationship. The mention of comorbidities as the most frequent reason for not modifying treatment may seem to contradict the fact that vignettes ‘high cardiovascular risk’ and ‘neoplastic history’ generated the least number of TIs in our study. This could be explained by the undoubted urgency of stopping treatment because of neoplasia, whereas the process of adapting treatment according to more latent, chronic comorbidities may generate difficulties conducive to TIs (or uncertainty). Comorbidities can, therefore, be both a driving force and a brake on TI. Some clinical situations in PsA raise the question not strictly related to TI but to decision uncertainty, and this is independent of the personality or behavioural psychology of the physician, but rather linked to PsA phenotypes.

The rheumatologist respondents overwhelmingly declared themselves comfortable in the management of PsA and aware of the SFR and/or EULAR recommendations for management, which is in line with the perception, perhaps erroneous, in another study of 132 rheumatologists, 98% of whom were aware of the EULAR/T2T recommendations [44]. Importantly, in this study, regarding the reality of physician’s knowledge vs how well they implement guideline recommendations, these appeared to be misaligned, with only 50–67% actually complying with recommendations. The same has been observed in the management of rheumatoid arthritis [45].

French rheumatologists have identified certain difficulties inherent in the management of PsA, i.e. therapeutic objectives are felt to be difficult to achieve, treatment efficacy is felt to be difficult to evaluate and there are limited therapeutic options. In our study, we saw self-assessment by respondents who considered they agree with guideline recommendations. It is surprising that the rheumatologists perceived a ‘limited therapeutic offer’ in PsA as many therapeutic options have appeared in recent years with indications according to the PsA subtype. Indeed, recommendations from SFR and EULAR include new therapeutic options (e.g. apremilast, anti-IL-17 antibodies and anti-IL-23 antibodies) which, therefore, should be known to rheumatologists.

Furthermore, this assumption calls into question recognition and alleged use of the DAS, DAPSA or MDA activity scores.

We saw that 97% of respondents attended and/or followed communications presented during at least one international, national or regional conference in the 2 years prior to the study (Supplementary Data S8, available at Rheumatology online). CME would, therefore, be achieved by respondents, although this assumption may be biased by the high level of interest in PsA declared a priori by respondents.

The main limitation of our study lies in its declarative nature and the biases inherent in this type of survey. Observational studies with external validation of practice types would be useful to confirm these results. The random effect of the occurrence of TIs was discussed, but seems to be limited because the vignettes that generated the most inertia were the first ones proposed, thus ruling out a potential ‘fatigue’ effect by respondents when completing the questionnaire. Some vignettes were deliberately longer or more detailed to reflect current clinical practice. Finally, the clinical vignettes included elements of clinical history and context that may have generated differences in interpretation—and therefore in response—from one physician to another. Indeed, some PsA phenotypes can also generate uncertainty, as recognized with enthesitis that can contribute to TI.

Nevertheless, we feel that the relatively large size of our sample of respondents, its representativeness in terms of types of practice and geographical distribution in our country (Supplementary Data S5, available at Rheumatology online) and its pragmatic approach by clinical vignettes [19, 26, 36, 46] allow us to draw certain conclusions.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first national study conducted on TI in PsA, and the first quantitative study in rheumatology that sheds new light on the frequency of this behaviour with possible explanations. Our findings raise the question of the true implementation of guideline recommendations in clinical practice and the reasons for TI in PsA [47, 48].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The survey was conducted by APLUSA, a market research firm specializing in healthcare, with editorial support from an independent medical publishing and communications agency (Medical Education Corpus). English proofreading was completed by A-Z Medical Writing.

Contributor Information

Frédéric Lioté, Université Paris Cité, UFR de Médecine, Paris, France; Rheumatology Department & INSERM U1132 Bioscar, Viggo Petersen Centre, Lariboisière Hospital, Paris, France.

Arnaud Constantin, Rheumatology Department, Pierre-Paul Riquet Hospital, Toulouse, France; Université Toulouse III—Paul Sabatier & INSERM, 1291 Infinity, Toulouse, France.

Étienne Dahan, Rheumatology Department, UF 6501, Hautepierre Hospital, CHU Strasbourg, France.

Jean-Baptiste Quiniou, Amgen, Boulogne-Billancourt, France.

Aline Frazier, Rheumatology Department & INSERM U1132 Bioscar, Viggo Petersen Centre, Lariboisière Hospital, Paris, France.

Jean Sibilia, Rheumatology Department, National Reference Centre for Rare Systemic Auto-immune Diseases East-South-West (RESO), CHU Strasbourg, France; Molecular Immuno-Rhumatology Laboratory, GENOMAX platform, INSERM UMR-S1109, Faculty of Medicine, Interdisciplinary Thematic Institute (ITI) of Precision Medicine of Strasbourg, Transplantex NG, Federation of Translational Medicine of Strasbourg (FMTS), University of Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Rheumatology online.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This study received institutional but non-interventional support from Amgen.

Disclosure statement: F.L.: Amgen, Biogen, Celgene, Fresenius Kabi, Janssen, Lilly, Mylan-Viatris, Nordic Pharma, Sandoz. E.D.: Amgen, Celgene, Lilly, Janssen, Abbvie, Arthrex. J.B.Q.: Amgen employee. A.F.: Abbvie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Chugai, Fresenius Kabi, UCB, Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, Lilly, Janssen. A.C.: Abbvie, Amgen, Biogen, BMS, Fresenius Kabi, Janssen, Lilly, Medac, MSD, Mylan-Viatris, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, UCB. F.L., A.C., E.D., J.B.Q., A.F., J.S.: PI, co-PI, conference and expertise fees from Amgen. The 101 participating physicians received a participation fee from APLUSA, based on a contract validated by the Conseil National de l’Ordre des Médecins (CNOM).

References

- 1. Lukas C. Épidémiologie du rhumatisme psoriasique. Rev Rhum Monogr 2020;6773:243–325. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pina Vegas L, Sbidian E, Penso L. et al. Epidemiologic study of patients with psoriatic arthritis in a real-world analysis: a cohort study of the French health insurance database. Rheumatology 2021;60:1243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mease PJ, Armstrong AW.. Managing patients with psoriatic disease: the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Drugs 2014;74:423–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGonagle D. Enthesitis: an autoinflammatory lesion linking nail and joint involvement in psoriatic disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smolen JS, Braun J, Dougados M. et al. Treating spondyloarthritis, including ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:6–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coates LC, Soriano ER, Corp N. et al. ; GRAPPA Treatment Recommendations domain subcommittees. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2022;18:465–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tucker LJ, Ye W, Coates LC.. Novel concepts in psoriatic arthritis management: can we treat to target? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2018;20:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perruccio AV, Got M, Li S. et al. Treating psoriatic arthritis to target: defining the psoriatic arthritis disease activity score that reflects a state of minimal disease activity. J Rheumatol 2020;47:362–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wendling D, Hecquet S, Fogel O. et al. 2022 French Society for Rheumatology (SFR) recommendations on the everyday management of patients with spondyloarthritis, including psoriatic arthritis. Joint Bone Spine 2022;89:105344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coates LC, Moverley AR, McParland L. et al. Effect of tight control of inflammation in early psoriatic arthritis (TICOPA): a UK multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:2489–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dures E, Shepperd S, Mukherjee S. et al. Treat-to-target in PsA: methods and necessity. RMD Open 2020;6:e001083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lebwohl MG, Kavanaugh A, Armstrong AW. et al. US perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: patient and physician results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) survey. Am J Clin Dermatol 2016;17:87–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB. et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:825–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Connor PJ, Sperl-Hillen JM, Johnson PE. et al. Clinical inertia and outpatient medical errors. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES eds. Advances in patient safety: from research to implemtation. Vol. 2: concepts and methodology. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US; ), 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okonofua EC, Simpson KN, Jesri A. et al. Therapeutic inertia is an impediment to achieving the Healthy People 2010 blood pressure control goals. Hypertension 2006;47:345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mohan AV, Phillips LS.. Clinical inertia and uncertainty in medicine. JAMA 2011;306:383; author reply 383–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scheen AJ. Inertia in clinical practice: causes, consequences, solutions. Rev Med Liege 2010;65:232–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simon D. Therapeutic inertia in type 2 diabetes: insights from the PANORAMA study in France. Diabetes Metab 2012;38(Suppl 3):S47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saposnik G, Sempere AP, Raptis R. et al. Decision making under uncertainty, therapeutic inertia, and physicians’ risk preferences in the management of multiple sclerosis (DIScUTIR MS). BMC Neurol 2016;16:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lebeau J-P, Cadwallader J-S, Aubin-Auger I. et al. The concept and definition of therapeutic inertia in hypertension in primary care: a qualitative systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Okemah J, Peng J, Quiñones M.. Addressing clinical inertia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Adv Ther 2018;35:1735–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grant RW, Cagliero E, Dubey AK. et al. Clinical inertia in the management of Type 2 diabetes metabolic risk factors. Diabet Med 2004;21:150–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paul SK, Klein K, Thorsted BL. et al. Delay in treatment intensification increases the risks of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2015;14:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Hickey EC. et al. Inadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive population. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gil-Guillén V, Orozco-Beltrán D, Pérez RP. et al. Clinical inertia in diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in primary care: quantification and associated factors. Blood Press 2010;19:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saposnik G, Montalban X, Selchen D. et al. Therapeutic inertia in multiple sclerosis care: a study of canadian neurologists. Front Neurol 2018;9:781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saposnik G, Montalban X.. Therapeutic inertia in the new landscape of multiple sclerosis care. Front Neurol 2018;9:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Almusalam N, Oh J, Terzaghi M. et al. Comparison of physician therapeutic inertia for management of patients with multiple sclerosis in Canada, Argentina, Chile, and Spain. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e197093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goossens J, Lancrenon S, Lanz S. et al. GOSPEL 3: management of gout by primary-care physicians and office-based rheumatologists in France in the early 21st century – comparison with 2006 EULAR recommendations. Joint Bone Spine 2017;84:447–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maravic M, Hincapie N, Pilet S. et al. Persistent clinical inertia in gout in 2014: an observational French longitudinal patient database study. Joint Bone Spine 2018;85:311–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perez Ruiz F, Sanchez-Piedra CA, Sanchez-Costa JT. et al. Improvement in diagnosis and treat-to-target management of hyperuricemia in gout: results from the GEMA-2 transversal study on practice. Rheumatol Ther 2018;5:243–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Halioua B, Corgibet F, Maghia R. et al. Therapeutic inertia in the management of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020;34:e30–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Halioua B, Zetlaoui J, Pain E. et al. Perception of therapeutic inertia by patients with psoriasis in France. Int J Dermatol 2020;59:e245–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Melin A, Sei J-F, Corgibet F. et al. ; The Fédération Française de Formation Continue et d’Evaluation en Dermatologie-Vénéréologie. Therapeutic Inertia in the Management of Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis in Adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol 2021;101:adv00475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pham T, Roy C, Mariette X. et al. Effect of response format for clinical vignettes on reporting quality of physician practice. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saposnik G, Mamdani M, Montalban X. et al. Traffic lights intervention reduces therapeutic inertia: a randomized controlled trial in multiple sclerosis care. MDM Policy Pract 2019;4:2381468319855642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A. et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:700–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wendling D, Lukas C, Prati C. et al. 2018 update of French Society for Rheumatology (SFR) recommendations about the everyday management of patients with spondyloarthritis. Joint Bone Spine 2018;85:275–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. DREES. Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques. Démographie des professionnels de santé. https://drees.shinyapps.io/demographie-ps/ (14 January 2022, date last accessed).

- 40. Shah BR, Hux JE, Laupacis A. et al. Clinical inertia in response to inadequate glycemic control: do specialists differ from primary care physicians? Diabetes Care 2005;28:600–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beaney T, Schutte AE, Tomaszewski M. et al. ; MMM Investigators. May Measurement Month 2017: an analysis of blood pressure screening results worldwide. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e736–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gazitt T, Elhija MA, Haddad A. et al. Implementation of the treat-to-target concept in evaluation of psoriatic arthritis patients. J Clin Med 2021;10:5659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ. et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1060–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gvozdenović E, Allaart CF, van der Heijde D. et al. When rheumatologists report that they agree with a guideline, does this mean that they practise the guideline in clinical practice? Results of the International Recommendation Implementation Study (IRIS). RMD Open 2016;2:e000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Batko B, Korkosz M, Juś A. et al. Management of rheumatoid arthritis in Poland – where daily practice might not always meet evidence-based guidelines. Arch Med Sci 2021;17:1286–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P. et al. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA 2000;283:1715–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dougados M. Treat to target in axial spondyloarthritis: from its concept to its implementation. J Autoimmun 2020;110:102398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Coates LC, Helliwell PS.. Treating to target in psoriatic arthritis: how to implement in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:640–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.