Abstract

Research on tokenism has mostly focused on negative experiences and career outcomes for individuals who are tokenized. Yet tokenism as a structural system that excludes larger populations, and the meso-level cultural foundations under which tokenism occurs, are comparatively understudied. We focus on these additional dimensions of tokenism using original data on the creation and long-term retention of postcolonial literature. In an institutional environment in which the British publishing industry was consolidating the production of non-U.S. global literatures written in English, and readers were beginning to convey status through openness in cultural tastes, the conditions for tokenism emerged. Using data on the emergence of postcolonial literature as a category organized through the Booker Prize for Fiction, we test and find for non-white authors (1) evidence of tokenism, (2) unequal treatment of those under consideration for tokenization, and (3) long-term retention consequences for those who were not chosen. We close with a call for more holistic work across multiple dimensions of tokenism, analyses that address inequality across and within groups, and a reconsideration of tokenism within a broader suite of practices that have grown ascendent across arenas of social life.

Keywords: tokenism, inequality, culture, media, awards

Research on tokenism has generally focused on individual-level effects, such as negative psychological and career outcomes (e.g., Jackson, Thoits, and Taylor 1995; Kanter 1977) and their sociodemographic variations (e.g., Wingfield 2013; Yoder 1991; Zimmer 1988). Complimentary to this are two comparatively understudied dimensions of tokenism. First, less empirical attention has been paid to tokenism as a structural system in which lower-status nondominant group members are pitted against each other for limited slots, and how in that system the incorporation of a few of those individuals may obscure underlying inequalities (Chang et al. 2019; Kerry 1960; Laws 1975). And second, less attention has been paid to how the underlying cultural foundations of any given context affect both who is tokenized and how (Turco 2010; Williams 1991). In this article we focus on these structural and cultural dimensions of tokenism to better understand the processes by which some members of underrepresented groups are let in for tokenistic representation, and what happens to would-be entrants who are kept out.

Our case is the consolidation of (non-U.S.) global literatures written in English into the category of postcolonial fiction, as institutionalized through the Booker Prize for Fiction (Anand and Jones 2008). Our data are built from archival submission lists of all nominations under consideration for the Prize from the years 1983 through 1996—the core period in which the market for postcolonial literature was created and consolidated through the Booker Prize (Huggan 1997; Ponzanesi 2014)—and the long-term retention (or lack thereof) for all nominated novels across those years. This institutional environment created the conditions under which a particular configuration of tokenism emerged and solidified over the long-term for non-white authors writing in English from around the world. 1

In what follows, we first trace the history of tokenism from its origins in social movements circles into the social sciences, and then to its more general applications to art and media fields. We explain how the underlying features of these fields, coupled with shifts toward cultural openness as a status marker, created the generic conditions under which tokenism might emerge. We then explain how this operates within the meso-level cultural foundations of our case, the British publishing industry in the second half of the twentieth century. To summarize our findings, within the awards system of the Booker Prize, we test for and find evidence of tokenism, as well as its long-term consequences. In brief, while a small pool of non-white authors quickly become the most celebrated of this era, this belies that in general, non-white authors were given fewer chances to succeed than were white authors, and there were relatively consistent ceilings and floors on how many non-white authors could simultaneously shortlist for the prize, which is exceedingly unlikely to have occurred by chance alone. Non-white authors were ultimately pitted against each other for long-term retention in ways that other identity groups of authors were not. For non-white authors, having one’s book come out in a prize cycle when a different non-white author wins the Booker costs the “losing” author citations, global library holdings, appearances on syllabi, entries in literary encyclopedias, and attention among readers. In closing we suggest ideas for future connections and research, and bring our findings into conversation with larger shifts toward conspicuously celebrating, performing, or showcasing diversity in ways that may obscure underlying inequalities.

Tokenism In Social Scientific Research

In both citation and orientation, social scientific research on tokenism overwhelmingly traces back to Kanter (1977). In Kanter’s framework, individuals who are tokenized contend with heightened visibility, the exaggeration of differences between themselves and the majority group, and expectations to fit constrained social roles based on sociodemographic stereotyping. These experiences lead to a variety of stressors and delimited opportunities for career advancement, including workplace-related depression, anxiety, and stress (Jackson et al. 1995), lack of workplace support (Taylor 2010), increased demands (Ghosh and Barber 2021), low job satisfaction, and affective commitment (King et al. 2010).

The consequences of being tokenized are well established in the literature and have been found in sites as varied as finance (Roth 2004), technology (Alegria 2019; Campero and Fernandez 2019), medicine (Floge and Merril 1986), mining (Rolston 2014), law (Wallace and Kay 2012), and policing (Gustafson 2008). Within the same basic framework, the most influential update to Kanter (1977) shows that being subject to tokenism is not only conditioned on being few in numbers but also on one’s identity markers (Williams 1992; Yoder 1991; Zimmer 1988) and the specific intersections of those identity markers (Alegria 2019; Alfrey and Twine 2017; Wingfield 2013). These productive improvements of Kanter’s framework maintain her original social-psychological focus on the “individual-level outcomes of being a token” (Watkins, Simmons, and Umphress 2019:339, emphasis added).

Although social scientific study of tokenism leans heavily on the individual-level outcomes of being included-yet-tokenized, in line with the origins of the concept and its more popular understanding, tokenism can generally be defined as situations and settings that include the following conditions: (1) individuals from lower-status nondominant groups are subject to different criteria for inclusion than are dominant group members, and (2) are subject to different treatment, valuation, and evaluation when included, such that (3) the number of included lower-status nondominant group members are kept small while their excluded nondominant counterparts suffer penalties from being kept out.

We believe that in line with this definition, two central dimensions of tokenism have been comparatively understudied: that (1) the inclusion of tokenized individuals relationally works to structurally exclude outsiders more generally, and (2) the cultural foundations under which tokenism occurs affect both who is tokenized and the shape that tokenism takes. We discuss these issues in detail in the following sections, with the former in relation to how it may operate in the domains of culture, media, and awards more generally, and the latter in relation to the specifics of our case.

The Structural Underpinnings of Tokenism

In its original evocation in social movements circles following Brown v. Board of Education, tokenism was a structural critique of the greater systemic exclusion that occurs when a select few from an underrepresented group are included and celebrated for tokenistic representation. As the lawyer and civil rights icon Constance Baker Motley (1963:225) warned, tokenism operates as “the successor to ‘separate but equal,’” presenting, in the words of labor organizer A. Phillip Randolph, a “thin veneer of acceptance masquerading as democracy” (Kerry 1960:1). Writing in the Cleveland Call and Post, William O. Walker (1960:2) explained that tokenism occurs when “companies employing thousands of workers . . . hire eight to ten Negroes and then cry from the mountain top about how liberal their employment policies are.” 2 This critique was imported into social scientific theorizing by the feminist social psychologist Judith Long Laws (1975:51–52), who saw tokenism “as an institution” that “has advantages both for the dominant group and for the individual who is chosen to serve as Token,” as tokenism structurally works to “restrict the flow of outsiders into the dominant group.” Kanter (1977) cites Laws (1975) three times in her foundational article, yet the analysis of tokenism as a larger relational system—which looks to how tokenism preserves structural inequalities, and particularly for those large numbers of lower-status nondominant group members who are excluded by tokenistic systems—was lost in the literature that built off Kanter’s formulation. We believe that the generic features of award systems and long-term cultural consecration in art and media may make these contexts particularly susceptible to tokenism, for three reasons.

First, because art and media generally operate as “winner-take-all” (Caves 2000) or “winner-take-most” (Thompson 2010) industries, the consequences of tokenism may be atypically harsh and measurable. For example, prizes, awards, and long-term artistic consecration are, almost by definition, inequality-generating processes (English 2009; Ginsburgh and Weyers 2014; Karpik 2010; Rossman and Schilke 2014). By awarding individuals as categorically above or superior to groups, they create “discontinuity out of continuity” (Bourdieu 1984:117), generating “a ‘lasting’ boundary between the greats and all the others” (Schmutz 2018:67–68) by separating “the chosen from the rest” (Accominotti 2021:11), who will quickly “drop into the dust bin of history” (Bourdieu 1993:106). Tokenism requires more than just the elevation of individuals above groups, but the elevation of one or a few lower-status nondominant group members above others is at least one precondition of a structural understanding of tokenism, and creative industries may more regularly produce generic forms of these arrangements.

Second, art and media operate as public-facing, project-based work in which the sociodemographic identities of creators are treated as highly salient. For example, race-based valuation, evaluation, and classification are found across creative industries, including in music (Grazian 2005; de Laat and Stuart 2023), film and television (Erigha 2021; Friedman and O’Brien 2017; Yuen 2016), fashion (Mears 2010), art (Buchholz 2022; Rawlings 2001), museum curatorship (Aparicio 2022; Banks 2021), dance (Robinson 2021), comedy (Jeffries 2017), radio (Chávez 2021; Garbes 2022), cuisine (Gualtieri 2022), and literature (Chong 2011; Saha and van Lente 2022). More substantively, in the restaurant industry, critics rely on different logics of evaluation for “ethnic” versus “classic” cuisines (Gualtieri 2022); in Hollywood, “racial valuations” are deployed in profit forecasting for films with black directors and casts (Erigha 2021); and in the classification processes for music, race “acts as a master category that overrides other feature values” when musicians engage in category blending (van Venrooij, Miller, and Schmutz 2022:575). For art and media there is also a general belief that, unlike in say pet grooming or accounting, “representation matters.” 3 We believe that the centrality of identity in art and media and the public-facing nature of the work create conditions in which, to the degree that diversity is valued, the “showcasing” of diversity (Shin and Gulati 2011) may also occur.

Third, in their public statements, creators from underrepresented groups who work in art and media report experiencing tokenism, in which a limited number of “slots” means one’s success is more zero-sum with the failures of other excluded group members than it is for those from dominant groups. As the comic Eliza Skinner explained of being a woman in comedy, “If you have a show with seven comics, a lot of times [club bookers] want to make sure they have at least one woman. They could have three women or four women, [but] they don’t. They try to have one” (Jeffries 2017:168). Making a similar observation regarding fiction, while remarking on her career as an editor, Toni Morrison (1994:133) noted that “the market only receives one or two” black authors at the same time. In his autobiography, Chester Himes (1972:201) concurred, writing that “The powers that be have never admitted but one black at a time into the arena of fame.” In his analysis of the book market, So (2020:11) cites the same phenomenon, noting that the “valorization of a handful of black authors” occurs “at the expense of acquiring books from many different black authors.” Or, as a white editor-in-chief critically explained the numerical minimum of tokenism, book publishing has always been a “playground for the landed gentry,” with authors like “[James] Baldwin and [Ralph] Ellison allowed in just to make the whole thing look more presentable” (Childress and Nault 2019:130–31; see also Ramsby and Ramsby 2022). Outside of the U.S. context, the artist and writer Olu Oguibe (2004:xii) explained his cynicism about tokenism in the global art market in similarly structural terms, noting that the gatekeepers in the field are

careful to ensure that no undue number of . . . “global native[s]” . . . have the opportunity to circulate at any one time. . . . In effect, their “discovery” is scrupulously managed and promotion firmly and methodically rationed to avoid an influx. . . . Unbeknownst to the natives, they are constantly lodged in a hidden battle against one another for the few, predetermined places and opportunities designated for them on the contemporary art stage.

That creators from underrepresented groups perceive themselves to be directly pitted against each other in ways that members of the dominant group are not serves as further validation for the empirical study of tokenism in these domains, particularly given that elevating individuals above groups is the point of artistic consecration. Evidence for tokenism would only be found, however, if individuals from lower-status nondominant groups faced different constraints than individuals from dominant groups. This may take the form of those few tokenized individuals from lower-status nondominant groups experiencing some advantages (as in Laws 1975), while still having their inclusion be provisional or limited to a certain number of “slots,” and being in direct competition for artistic retention with each other in ways that dominant group members are not. In its original social movements framework, accusations of tokenism presumed intent, but the presence or absence of tokenism as a relational structural system can be measured as tokenism has traditionally been studied in the social sciences, which is through differential constraints, experiences, and outcomes.

The Cultural Foundations Of Tokenism

The cultural foundations under which tokenism occurs should be central in describing which lower-status nondominant group members are subjected to tokenism and the shape that tokenism takes (Turco 2010; Williams 1991). In Turco’s (2010) case, the leveraged buyout industry, white women and racially minoritized women and men are all members of lower-status nondominant groups, yet because in this industry institutionalized images of the ideal worker conflict with motherhood, women face greater consequences from tokenism than do non-white men. While tokenism is more generally a relationally structural system in which lower-status nondominant group members are kept out, who is tokenized and the shape that tokenism takes is culturally contingent, and “endogenous to the local cultural context” (Turco 2010:907). In what follows we first discuss limited expansion of the high-status “literary” canon through prizes and awards, followed by the specific cultural foundations of our case—the mid- to late-twentieth-century British book publishing industry and the creation of “postcolonial fiction” through the Booker Prize for Fiction.

Diversifying the Global Field

Although far from totalizing or egalitarian, the mid-to-late twentieth century saw both an internationalization and a racial diversification of the global fields for art and literature (Buchholz 2022; Casanova 2004; Santana-Acuña 2020), at least in their higher-status and more “artistic” sectors. As Mel Watkins exclaimed in The New York Times Book Review in 1969, “Black [had become] good. Black is Beautiful. Black is . . . marketable!” (Watkins 1969:3). With the “rising prestige of African American literature in general and its expanding place within the university curriculum in particular” (English 2009:245), an opening of the literary canon along racial (Corse and Griffin 1997; Manshel 2023) and international lines emerged as a deliberate institutional practice (Lauter 1991; Nishikawa 2021), with the diversification of literary prize-winners in particular serving as “a good indicator of this recognition” (Sapiro 2016:91). As So (2020:131) notes, “the category of the literary prize winner” had “increasingly [become] a mechanism to promote multiculturalism,” such that since the 1980s, non-white authors have been statistically overrepresented among fiction and poetry award-winners (Grossman, Young, and Spahr 2021; Spahr and Young 2020).

Importantly, however, this opening up of the canon and reliance on prizes as a tool to promote multiculturalism belies substantial inequalities along racial lines in global English-language book publishing (Childress 2017; Childress and Nault 2019; Chong 2011; McGrath 2019; Saha and van Lente 2022; So 2020). Because the celebration of difference at the very top of the market does not seem to trickle down through the rest of the market, even among racially nondominant award-winners, success is seen as conditional and provisional (Kanter 1977). As the novelist Kiese Laymon explained of such provisional acceptance, “we finally see . . . people who look like us who are getting opportunities,” but they may not “get three, and four, and five, and six opportunities as some other people do” (Klein 2021).

Notably, an institutional context in which there is rising prestige for a limited sector of highbrow, non-white award-winners has been mirrored in shifting tastes among both the donor class that funds literary nonprofit publishers (Sinykin 2023) and the “reading class” that consumes fiction for pleasure (Griswold, McDonnell, and Wright 2005). More generally, higher-social-status consumers moved to cultural openness—and cultural openness to difference in particular (Chan 2019; van Eijck and Lievens 2008)—as a form of elite status-signaling (Bennett et al. 2009; Peterson 2005; Peterson and Kern 1996; Sherman 2017). Yet within this shift to cultural openness there is still an underlying snobbery in tastes (Jarness and Friedman 2017; Johnston and Baumann 2009; Lena 2019; Warde and Gayo-Cal 2009). This snobbery is reflected in a variety of ways: (1) by being more culturally open at the level of genres while being more restrictive of objects within those genres (Childress et al. 2021); (2) by shoring up concerns about moral character through the consumption of “authentic” lowbrow culture (Hahl, Zuckerman, and Kim 2017; see also Fine 2006); and (3) by investing in multicultural capital (Bryson 1996) or cosmopolitan capital (Prieur and Savage 2013) through the consumption of higher-status non-white or internationally “exotic” cultural forms.

In summary, we believe that tokenism may occur under macro-level conditions in which there is rising institutional prestige for a small number of non-white authors through literary prizes and awards, while higher-educated readers are simultaneously signaling their status and moral worth through cultural openness to difference that prioritizes objects that are higher status, honored, and consecrated as “authentic” or legitimate. However, it is the meso-level specifics of any site within the global literary field that dictates the form and shape of who is tokenized, and how.

British Publishing, the Booker Prize, and the Formation of Postcolonial Literature

In a dataset constructed by Rutherford and Levitt (2020:622), Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart appears on more English-language university syllabi than any other novel. However, Achebe is one of only three “non-Western” novelists (along with Salman Rushdie and Jamaica Kincaid) who are above the median using this measure of institutional retention. Both Things Fall Apart and this gap in institutional retention of global, non-white authors are rooted in cultural foundations that emerged in the post-war period of British publishing.

Due to labor shortages in the wake of the second World War, the British Nationality Act of 1948 allowed unfettered movement into and out of England for over 700 million colonial subjects of the Commonwealth. 4 A boom in art and culture in London was fueled by migration from South Asia, Africa, and the early Windrush generation of Caribbean migrants into the metropole (Walmsley 1992). In the London book publishing industry in particular, as summarized by Griswold (1987:1085), the “British intelligentsia were eager to incorporate their exotic brethren from a dying empire into the mainstream of English culture.”

This first wave of what would be known as “commonwealth literature” was fueled by publishers such as Faber & Faber, Hutchinson’s “New Authors” series, Oxford University Press’s “Three Crowns” series, Heinemann Educational’s “African Writers” series, Longman’s “Drumbeat” series, and the BBC’s “Caribbean Voices” radio program, which “functioned like a publishing house” (Low 2002:29). This investment in “diversity capital” (Banks 2022) secured reputational accolades for British publishers, but by the mid-1970s and early 1980s the market floundered, as the two financial sources propping it up declined. First, British library sales, which had become “the successors of the old upper class patrons” for the British publishing industry (Dempsey 1969:59), decreased during the recession of the mid-1970s. And second, in the collapse of the British colonial empire, the international market for educational books in English, which had propped up this cosmopolitan infrastructure, also declined. Cheap paperback copies of Things Fall Apart sold to the African educational market, for example, had generated one-third of the total revenue for Heinemann’s “African Writers” series (Kalliney 2013; Low 2012).

Yet the transition from “commonwealth literature” to “postcolonial literature” did not so much involve a shift in publishers or publishing arrangements as it involved a shift in international relations and market focus. First, the term “commonwealth literature” had become associated with increasingly outmoded colonial relationships, as between 1944 and 1997, the British colonial empire decreased from 40 states with 760 million non-English subjects to 12 states with 168,000 non-English subjects (Strongman 2002:xii). Second, with a decline of state sponsorship at home and abroad, what had been “commonwealth literature” needed a new market. Publishers found one in marketing what was soon to become postcolonial literature as a “luxury commodity for the British educated middle-classes,” the appreciation for which emerged as “a mark of discernment” (Donnelly 2015:49, 142; see also Bejjit 2019). Central to these developments were the field configuring effects of the Booker Prize for Fiction (Anand and Jones 2008).

Founded in 1968, the Booker Prize is a “cultural institution of incomparable significance” (Atlas 1997:38) that is “widely regarded today as one of the world’s top literary prizes” (Huggan 2002:107). Modeled after the French Prix Goncourt, the original English-language Booker was intended to drum up interest and promote “serious” fiction in the United Kingdom at a time when the book trade was in relative decline (Huggan 2002; Squires 2004). It did so by consolidating global literature written in English that was not from the United States, as a countermove against the rising global dominance of U.S. publishers (Kalliney 2013; Strongman 2002; Todd 1996).

In its first 13 years the prize awarded several (of what would come to be understood as) postcolonial authors (e.g., V.S. Naipaul, Nadine Gordimer, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala), but the consolidation of postcolonial literature as a category really took root with Salman Rushdie’s 1981 Booker win for Midnight’s Children. This moment was “a major catalyzing force behind the emergence of a postcolonial literary era” (Huggan 1997:413), as Rushdie’s win quickly led to “postcolonial literature . . . becom[ing] a much sought-after commodity” (Ponzanesi 2014:72). 5 Like “commonwealth literature,” the category of “postcolonial literature” was both “highly ambiguous” (Hiddleston 2009:2) and “strategically malleable” (Huggan 2002:110). It was implicitly operationalized to mean “writers from elsewhere,” vaguely defined as anyone who was not from the United States or the combination of English national origin, living in England, and white (Manferlotti 1995). 6

As a result, “elsewhere” included everyone from Nigerian and Indian nationals (e.g., Ben Okri, Anita Desai) to non-white Londoners (e.g., Kazuo Ishiguro, Timothy Mo), “the English abroad” (e.g., J. M. Coetzee, Doris Lessing), and at times, British, non-English writers (the “original” colonial and postcolonial British subjects, some argued). This consolidation was desirable to publishers as it “created the impression of a group by gathering together under a single label authors who had nothing, or very little, in common” (Casanova 2004:120). As Kazuo Ishiguro remarked of the influence of Salman Rushdie’s Booker Prize win on the formation of postcolonial literature and on his own career, “Everyone was suddenly looking for other Rushdies . . . [and] because I had this Japanese face and this Japanese name [my first novel] was being covered at the time” (Vorda and Herzinger 1991:134–35).

Although the category of what counted as “postcolonial” was flexible, it traded in the marketing of an “authentic marginality” (Spivak 1993:63, see also Brouillette 2007; Huggan 2002), such that it “implicitly and explicitly confirmed the idea of racial authenticity as a measure of literary and cultural achievement” (Eversley 2004:xii; see also Fine 2006; Grazian 2005). 7 And while both the Booker Prize (as a cultural institution) and middle-class English readers accrued a “powerful” amount of cultural capital through their conveyance of a “multicultural consciousness” (Anand and Jones 2008:1056; Kalliney 2013), it was a “cosmetic multiculturalism” (Nayar 2018:27) centered around the “commerce of an ‘exotic’ commodity catered to the Western literary market” (Eakin 1995:1; Huggan 1997). As a result, central to the Booker’s reputation as one of the literary world’s “most prestigious awards” is also the prize’s “postcolonial cachet” (Ponzanesi 2014:58).

Yet despite “critics confusing cause for effect” in claiming the Booker prize was recognizing “the existence of a ‘new’ literature” (Casanova 2004:12), it was ultimately the field-configuring effects of the Booker Prize itself that led to “the construction of postcolonial fiction as a coherent market category” (Anand and Jones 2008:1054). 8 As part of a broader cultural movement in which “ethnicity is in” and “consumption of the Other is all the rage” (Sharma, Hutnyk, and Sharma 1996:1), in English-language fiction, postcoloniality had become a “generative and saleable feature” (Brouillette 2007:7) that operated as part of a “booming ‘otherness industry’” (Ponzanesi 2014:14). Yet, “the Booker Prize, even as it has expanded public awareness of the global dimensions of English-language literature, has paradoxically narrowed this awareness to a handful of internationally recognised postcolonial writers” (Huggan 2002:119), such that “the appreciation of postcolonial literature” is limited to a curated “handful of authors . . . who are selected as spokespeople for their nations” (Ponzanesi 2014:14). Or, in another word, tokenism.

Hypotheses

Our hypotheses examine how the work of non-white authors circulated within the awards system of the Booker Prize and the wider literary field during the consolidation of global literatures written in English into the category of postcolonial fiction. Our hypotheses test for (1) the presence of tokenism, (2) the unequal treatment of individuals competing for tokenized positions, and (3) the long-term consequences of a tokenistic system for those not chosen for representation.

Prizing Otherness

Our data come from a period in which literary prizes emerged as a central tool to promote multiculturalism (Corse and Griffin 1997; English 2009; Grossman et al. 2021; Lauter 1991; Nishikawa 2021; Sapiro 2016), leading to, at least in the United States, “the valorization of a handful of black authors” (So 2020:11, emphasis added). For the British publishing industry, promoting the work of “writers from elsewhere” (Manferlotti 1995) emerged as a countermove against the rising global dominance of U.S. publishers (Kalliney 2013; Strongman 2002; Todd 1996), and as a mark of “discernment” and “diversity capital” (Banks 2022) for publishers and the “British educated middle-class” (Donnelly 2015:49). Under the canopy of this cultural context, and given that tokenism, “as an institution,” can “have advantages both for the dominant group and for the individual who is chosen to serve as Token” (Laws 1975:51–52), our first hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1a: Non-white authorship predicts both shortlisting for and winning the Booker Prize.

Given the particular cultural context of our data, that is, during an emerging “booming ‘otherness industry’” (Ponzanesi 2014:14), we believe there may have been a scramble to create the next “postcolonial star-author” (Nayar 2018). This leads to Hypothesis 1b:

Hypothesis 1b: Non-white authors are more likely to make the shortlist on their first nomination than are white authors.

Ceilings on Opportunity

Quickly and more frequently bestowing awards on a limited number of individuals from lower-status nondominant groups may be a first sign of tokenism, or it may be an acknowledgment of superior talent, a celebration of difference, or a redressing of past wrongs. Put another way, in isolation, Hypotheses 1a and 1b cannot differentiate between celebrating difference and diversity showcasing (Shin and Gulati 2011), such as when tokenized individuals are thrust forward to “serve as ‘proof’ that the [dominant] group does not discriminate against such people” (Zimmer 1988:65; see also Kanter 1977). This latter form of tokenism is not uncommon, as seen in the racial staging (and sometimes photoshopping) of pictures in college brochures (Leong 2021; Pippert, Essenburg, and Matchett 2013), when firms increase diversity in their most visible locations in response to discrimination lawsuits (Knight, Dobbin, and Kalev 2022), or when music festival organizers put non-white acts in “prominent, visible” locations on the poster for their “aesthetic value” and the reputational kudos they hope to secure (de Laat and Stuart 2023:1526, 1535). To differentiate which of these processes is occurring requires further evidence.

If diversity is being celebrated, we would predict that a rising population of non-white authors under consideration for the prize should correspond with a rise in the awarding of non-white authors, such that the numerator and denominator are related to each other. If, however, tokenism is occurring, a rising tide of nominations of non-white authors would not lift all boats, as the tokenizing diversity “slot” has already been filled:

Hypothesis 2a: As the number of nominated books by non-white authors increases, the likelihood of non-white authors making the shortlist does not increase.

A celebration of diversity or belief in superior talent would also suggest that non-white authors may get more chances to be successful than do white authors. In contrast, in a tokenism framework in which non-white authors are restricted to an artificial ceiling and floor of representation, they would be treated as more disposable and replaceable, as artistic quality is treated as if it is derived from “racial authenticity” rather than from individual talent (Eversley 2004:xii). For Hypothesis 2b we formally test author Kiese Laymon’s concern that authors from racially nondominant groups get fewer chances to succeed than do white authors:

Hypothesis 2b: Non-white authors receive fewer repeat nominations without being shortlisted than do white authors.

Long-Term Consecration

So far, our hypotheses have focused on how tokenism operates within an awards system. We now turn to long-term literary consecration as potentially resulting from tokenism within that awards system. Central to a structural understanding of tokenism is that individuals from lower-status nondominant groups are directly pitted against each other for career success in ways that individuals from dominant groups are not. This cornerstone of tokenism is reflected in Ponzanesi’s (2014:4) question about the Booker Prize more generally, asking, “whether the attribution of prestigious literary prizes to postcolonial authors widens the palette of aesthetic reception or narrows the appreciation of postcolonial literature to a handful of authors.” This is formalized as Hypothesis 3:

Hypothesis 3: Books by non-white authors that come out in the same year that a different non-white author wins the Booker Prize suffer long-term consecration penalties compared to books by non-white authors that come out in a year when a white author wins the Booker Prize.

Data And Methods

Data

Our data consist of all submissions to the Booker Prize for Fiction from the years 1983 through 1996, as procured from the original submission lists housed at the Booker Archives at the Oxford Brookes Library in England. The Booker is awarded annually in a three-step process that starts with (1) private nominations, from which (2) a shortlist of (usually) six novels is constructed and publicly announced, and then (3) a winner is declared. In the first stage, to be considered, books must be nominated by their publishers. To be eligible, the nomination must be a book-length work of fiction that is published in that year’s prize cycle and written in English by a citizen of the United Kingdom, Commonwealth countries, Ireland, or Zimbabwe. 9 The Booker is administered by a committee that includes an author, a literary agent, three publishers, a bookseller, a librarian, and two representatives from Booker. Each year, this committee selects five judges, which includes the Chair, and “usually an academic, a critic or two, a writer or two and the man in the street [who is usually a celebrity]” (Goff 1989:18). In the years of our data, this “expert opinion regime” (Karpik 2010) included 70 different total judges. 10

There is a 20-year embargo on the release of prize materials to researchers. Submission lists from 1983 to 1992 were originally secured by Brian Moeran (see Childress, Rawlings, and Moeran 2017), with the 1993 through 1996 lists secured in 2017 by Childress. 1982 to 1996 is the key period in which the category of postcolonial literature was institutionalized through the Booker Prize. This period of institutionalization is bookended by Salman Rushdie’s 1981 win for Midnight’s Children and Arundhati Roy’s 1997 win for The God of Small Things, by which point there was “an entire already primed commercial network . . . around the globe [that] was simply activated . . . [including] a full-blown media offensive which advertised Roy as the new jewel in the crown from India” (Ponzanesi 2014:73). Submission lists prior to 1983 were not archived, meaning data for 1982 are not available. From 1983 to 1996, an average of 122 books were nominated for consideration each year (N = 1,701), with the proportion of books by non-white authors that were submitted nearly tripling during the period (from about 1/25th of all submissions in the earlier years to about 1/8th of all submissions in the later years).

For Hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3, the level of analysis is the book, meaning authors can have multiple books in the dataset during the period. For Hypotheses 1b and 2b, each author has one observation, such that we can track shortlisting and nominations across authors’ careers during the entire period.

Variables Used in Models

Dependent variables

The dependent variable for Hypotheses 1a and 2a is shortlisting for the Booker Prize. For Hypothesis 1b, the dependent variable is dichotomously constructed as first timer, that is, an author whose book was shortlisted the first time they were nominated. Hypothesis 2b predicts a count variable constructed as the number of times an author is nominated without shortlisting—that is, how many times an author can fail to shortlist for the prize while still having their new book nominated by their publisher. For Hypothesis 3, long-term retention is measured across five indices: global library retention (from WorldCat), presence on global syllabi (from the Open Syllabus Project), appearances across seven literary encyclopedias, academic citations across books and articles (from Google Scholar), and the number of popular reviews on GoodReads as a measure of popular retention (because sales data for this era are not available). 11 We estimate that for Booker novels, each GoodReads review may equate to around 14 sales. 12

Independent variables

For Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 2b, the key predictor is non-white authorship. 13 For Hypothesis 2a, the key predictor is an interaction term between non-white authorship and the composition of the pool in which they are competing (i.e., the percent of nominations for authors who are not white). The key predictor for Hypothesis 3 is an interaction term between non-white authorship and years in which a non-white author won the Booker prize. We also include author identity categories and their same-year interaction terms for other categories of authors (i.e., English, Irish/Scottish/Welsh, white authors in/from non-European countries, and women) to test if there is a wider same-year effect.

Controls for Hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3 include author gender; if the publisher is a conglomerate, and if at time of submission they had offices in the Bloomsbury district of London; if the novel has no women as main characters; if the main character(s) are not residents, immediate emigres, or travelers from European countries (postcolonial main character); and if the story is primarily set in a non-European location (postcolonial setting). 14 Hypothesis 3 measures long-term retention, so we also control for shortlisting, include an other prizes variable for winning nine other literary prizes, and if the novel was turned into a movie or serialized television show (IMDB; for the importance of media conversion for long-term retention, see Caves 2000; English 2009).

Controls for models related to Hypotheses 1b and 2b include the number of novels written during the period (publications), the author’s age at time of the first nomination, if they were/are a woman, and year of first nomination. Descriptive statistics for all variables used in the models are reported in Appendix Table A1.

Models

We test the hypotheses using several statistical models. To account for the longitudinal data structure, we estimated all models using clustered standard errors. Models testing Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 2a can be written in terms of a linear logit model:

| (1) |

where is the probability of novel i shortlisting, winning the Booker Prize, or shortlisting on that author’s first nomination; is a baseline predicted logit when all covariates are zero; t indexes the prize year; indicates if book i was written by a non-white author; and controls are contained in Thus, tests Hypothesis 1a, and tests for Hypotheses 1b and 2a. Models testing Hypothesis 1b, which as with 2b switch the unit of analysis to the author-level, capture temporal effects through first nomination year. Models testing Hypothesis 2b take the same general form as those testing 2a but are Poisson in their functional form.

Due to overdispersion in the counts that gauge the long-term retention of each novel, models testing Hypothesis 3 use negative binomial regression. These models take the following linear form:

| (2) |

where is one of the five measures of long-term retention of novel i; is an indicator variable for when novel i was written by a postcolonial author; and is the indicator variable for when novel i was published in the same year’s prize cycle in which a postcolonial author won the Booker Prize. Thus, the interaction term tests the hypothesis that novels by postcolonial authors published in the same year in which a postcolonial author won the Booker Prize will suffer long-term penalties in terms of retention. To account for the alternative hypothesis that the same penalties are levied across any number of other identity categories (e.g., women authors), we also include the main effects of these categories and their interaction terms with years when members of each identity group won the Booker Prize. We do not surmise that no penalties exist for any other group, but we do maintain that the penalty for postcolonial authors will be robust to the inclusion of possible conflating factors and will be more pronounced than other possible penalties. Control variables are contained in Zi .

Results

Prizing Otherness

Table 1 shows results from logistic regression models predicting shortlisting for and winning the Booker Prize. In support of Hypothesis 1a, across all models non-white authorship predicts shortlisting and winning. In addition to the statistical significance of the effect, its magnitude is also substantively significant. Books by non-white authors have over seven times the likelihood of shortlisting compared to other books (OR: 7.68; p < 0.05). In turn, a book by a non-white author has over 10 times the likelihood of winning the Booker prize compared to other books (OR: 10.51; p < 0.01). In addition to the focal effect, a book being published by a conglomerate press (OR: 1.92; p < 0.01) or having no women as main characters (OR: 2.94; p < 0.001) also predict shortlisting for the prize. No other significant predictors beyond non-white authorship predict winning.

Table 1.

Shortlisting and Winning

| Shortlist | Win | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Hypothesis 1a | ||||

| Non-white Author | 3.336***

(1.144) |

7.685*

(6.927) |

4.488**

(2.574) |

10.268**

(9.158) |

| Hypothesis 2a | ||||

| Non-white Pool Composition | .697 (2.788) |

|||

| Non-white Author x Pool Composition | .000 (.000) |

|||

| Controls | ||||

| Woman Author | 1.630 (.467) |

1.271 (.839) |

||

| Conglomerate | 1.923**

(.442) |

1.622 (.834) |

||

| Bloomsbury | 1.508 (.382) |

1.638 (.857) |

||

| Postcolonial Setting | .868 (.291) |

.798 (.419) |

||

| Postcolonial Main Character | 1.445 (.542) |

.319 (.313) |

||

| No Women Main Characters | 2.938***

(.908) |

1.849 (1.248) |

||

| Constant | .045***

(.006) |

.011***

(.005) |

.007***

(.002) |

.003***

(.002) |

| N | 1,696 | 1,686 | 1,696 | 1,686 |

Note: Coefficients are in odds-ratios. Robust standard errors (clustered by author) are in parentheses.

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

Hypothesis 1b stated that non-white authors are more likely to shortlist on their first nomination than are white authors. Results from Table 2 support Hypothesis 1b. Controlling for gender, age, and first year of nomination, compared to white authors, the odds of non-white authors shortlisting on their first nomination are 4.8 to 1 (p < 0.01). Results from Hypotheses 1a and 1b show that some non-white authors are being quickly elevated for prizes during this period.

Table 2.

Shortlisting on First Nomination

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1b | ||

| Non-white Author | 4.377**

(2.031) |

4.825**

(2.296) |

| Controls | ||

| Woman Author | .801 (.370) |

|

| Age | 1.007 (.015) |

|

| First Nomination Year | .907 (.057) |

|

| Constant | .020***

(.005) |

.028***

(.026) |

| N | 966 | 896 |

Note: Coefficients are in odds-ratios. Robust standard errors (clustered by author) are in parentheses.

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

Ceilings on Opportunity

Hypothesis 2a predicted that as the number of nominated books by non-white authors increases, the overall likelihood of shortlisting for non-white authors would not increase. In Model 2 of Table 1 we formally model Hypothesis 2a with an interaction between non-white authorship and non-white composition of the pool. From a technical perspective, we cannot affirm a null hypothesis (i.e., we can only reject or fail to reject), but the implication of a failure to reject in this case is that we have no support for the alternative, that is, the effect of non-whiteness on shortlisting is a function of the racial composition of the pool in any given year (coeff.: 0.00000422, p: 0.213).

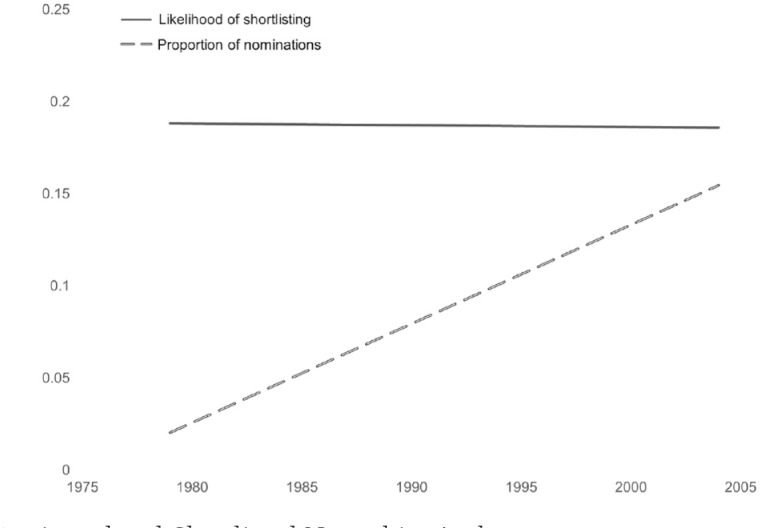

To investigate the chances the shortlist would contain at least one non-white author in 13 of 14 years, and no more than one non-white author in 10 of 14 years, we ran a simulation using information on the racial composition of the pool of nominees to estimate the probability of a non-white author being shortlisted for the Booker by chance alone during this period. In only 0.003 percent of one million simulated datasets does at least one non-white candidate appear on the shortlist in as many years as actually occurred, and in less than 0.15 percent of simulated datasets does no more than one non-white candidate appear on the shortlist in as many years as actually occurred (see the Appendix for more details). In short, while it is not unusual to observe a shortlist containing a single non-white author in any given year, it is extremely unlikely that this particular configuration would appear as often as it did by chance alone. Yet as shown in Figure 1, the tendency to shortlist a single non-white author was a persistent feature of the award process in the quarter century spanning 1980 through 2004, during which time the shortlist contained a single non-white author in 19 out of 25 years.

Figure 1.

Nominated and Shortlisted Non-white Authors

Hypothesis 2b predicted that non-white authors are given fewer opportunities to “fail” than are white authors. In short, non-white authors receive fewer repeat nominations without having been shortlisted than do white authors. As seen in Table 3, we find support for Hypothesis 2b both in bivariate association and when controlling for gender, age, number of publications, and year of first nomination. Authors who published more novels during the period are more likely to be repeat nominees without having been shortlisted than are those who published fewer novels, as are authors who are younger at the time of their first nomination compared to those who are older. In addition to non-white authorship independently predicting fewer nominations without shortlisting, in models not reported (available upon request), non-white authorship is also operating through number of publications, with non-white authors, on average, having one fewer novel published over the period compared with white authors, with other variables held at their means. Put another way, non-white authors may be doubly disadvantaged when receiving repeat nominations: for reasons beyond the scope of this article, they publish less than white authors (a precondition for being nominated), and even when controlling for their lower output, they still receive fewer nominations without having been shortlisted than do white authors. Results from Hypotheses 2a and 2b thus suggest distinct ceilings on opportunity for non-white authors.

Table 3.

Times Nominated without Shortlisting

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 2b | ||

| Non-white Author | −.245**

(.077) |

−.155*

(.078) |

| Controls | ||

| Publications | .053***

(.008) |

|

| Woman Author | −.006 (.054) |

|

| Age | −.010***

(.002) |

|

| First Nomination Year | −.043***

(.006) |

|

| Constant | .402***

(.027) |

.940***

(.114) |

| N | 966 | 896 |

Note: Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

Long-Term Consecration

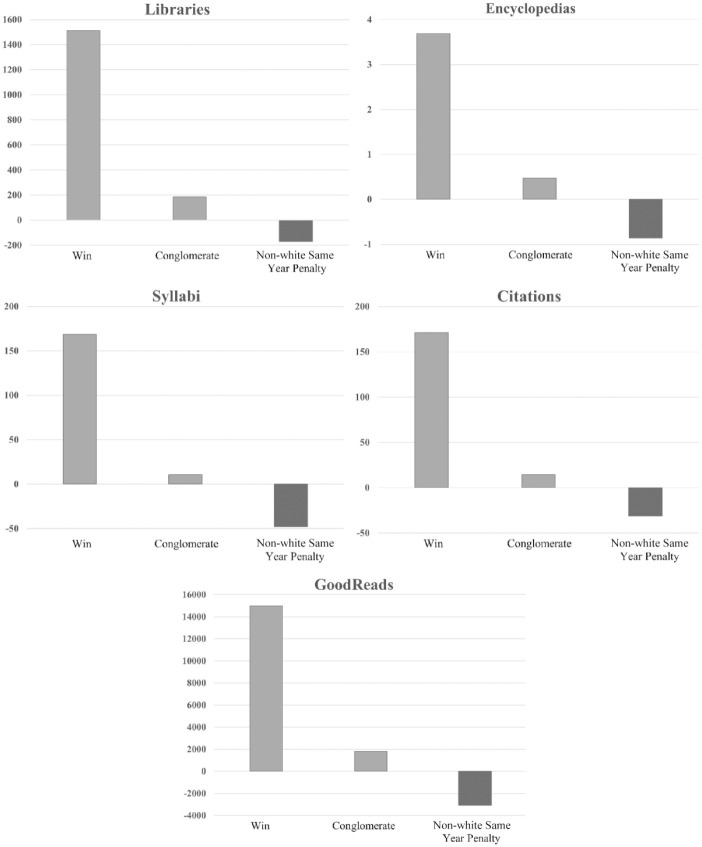

Hypothesis 3 predicted that tokenism pits non-white authors against each other for long-term consecration, such that the long-term retention of one non-white author comes at the expense of other non-white authors being comparatively forgotten. We look at the long-term consecration of non-white authors who were nominated and formally considered for, but did not win, the Booker Prize across five indices—library holdings, encyclopedia entries, assignment in syllabi, citations, and consumer reviews. We compare authors whose books were released in an annual prize cycle when a different non-white author won the Booker Prize to those whose books were released in a prize cycle when a non-white author did not win the Booker Prize.

Table 4 presents results for Hypothesis 3, finding significant effects of a same-year penalty for non-white authors across all five indices, in bivariate models and with the full suite of controls. Notably, this effect only occurs for non-white authors: English authors, Irish/Scottish/Welsh authors, white colonial authors, and women authors do not experience same-year penalties. Long-term literary retention is also predicted by having been shortlisted for the Booker Prize, a novel having been published with a conglomerate press, having won other literary prizes, having been turned into a movie or show, and the publisher having offices in London’s Bloomsbury district (in four of five indices). We also find main retention effects for authors associated with the postcolonial literature category, including non-white authors (across all five measures), white colonial authors (across four of five measures), and Irish/Scottish/Welsh authors (across three of five measures).

Table 4.

Same-Year Books by Non-white Authors

| Libraries | Encyclopedias | Syllabi | Citations | GoodReads | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| Hypothesis 3 | ||||||||||

| Non-white Author | .361**

(.127) |

.492*

(.230) |

.959***

(.107) |

1.588***

(.308) |

2.037***

(.350) |

3.876***

(.543) |

1.701***

(.227) |

2.466***

(.297) |

.325 (.437) |

2.042***

(.525) |

| Non-white Win Years | .044 (.062) |

−.039 (.105) |

.097 (.070) |

.344**

(.122) |

.430 (.426) |

.723 (.528) |

.037 (.224) |

.434 (.331) |

−.361 (.344) |

.370 (.361) |

| Non-white x Win Years | −.549*

(.230) |

−.449*

(.201) |

−.477*

(.241) |

−.528*

(.209) |

−2.276***

(.628) |

−2.172***

(.504) |

−.838*

(.359) |

−.820**

(.316) |

−2.368***

(.616) |

−1.707*

(.712) |

| Controls | ||||||||||

| White English Author | .127 (.238) |

.529 (.324) |

.956*

(.398) |

.252 (.259) |

1.391**

(.432) |

|||||

| White English Win Years | −.023 (.122) |

.249 (.138) |

1.099*

(.534) |

.508 (.332) |

.442 (.405) |

|||||

| White English x Win Years | −.172 (.106) |

−.132 (.122) |

.015 (.302) |

.024 (.215) |

.175 (.406) |

|||||

| Irish/Scottish/Welsh Author | .121 (.237) |

.748*

(.320) |

1.171**

(.435) |

.399 (.254) |

1.295**

(.445) |

|||||

| Irish/Scottish/Welsh Win Years | −.094 (.145) |

.314 (.166) |

.514 (.592) |

.518 (.408) |

1.285*

(.508) |

|||||

| Irish/Scottish/Welsh x Win Years | .198 (.202) |

.330 (.208) |

1.524*

(.649) |

.717 (.401) |

1.321 (.816) |

|||||

| Colonial White Author | .376 (.252) |

1.162***

(.327) |

1.883***

(.534) |

1.185**

(.346) |

1.664**

(.491) |

|||||

| Colonial White Win Year | .049 (.154) |

.489**

(.176) |

.818 (.587) |

.380 (.381) |

.237 (.461) |

|||||

| Colonial White x Win Year | −.146 (.229) |

−.091 (.259) |

−.698 (.612) |

−.524 (.465) |

−.949 (.658) |

|||||

| Woman Author | .219*

(.107) |

.061 (.132) |

.241 (.252) |

−.040 (.208) |

−.117 (.240) |

|||||

| Woman Win Year | .043 (.084) |

.140 (.099) |

.023 (.215) |

.134 (.179) |

.753*

(.361) |

|||||

| Woman x Win Year | −.005 (.111) |

.086 (.127) |

.786*

(.389) |

.160 (.275) |

−.680 (.527) |

|||||

| Conglomerate | .528***

(.063) |

.395***

(.076) |

1.171***

(.175) |

.842***

(.136) |

1.238***

(.205) |

|||||

| Bloomsbury | .149*

(.075) |

.255**

(.084) |

.550**

(.199) |

.339*

(.160) |

.110 (.231) |

|||||

| Postcolonial Setting | .098 (.086) |

−.020 (.105) |

.311 (.255) |

.305 (.261) |

−.491 (.282) |

|||||

| Postcolonial Main Character | −.114 (.105) |

.056 (.137) |

−.800**

(.279) |

−.529*

(.232) |

.212 (.324) |

|||||

| No Women Main Characters | .050 (.068) |

−.082 (.079) |

−.423*

(.189) |

−.223 (.132) |

−.068 (.198) |

|||||

| Other Prizes | .465***

(.088) |

.348**

(.115) |

1.292***

(.235) |

1.111***

(.220) |

.832*

(.388) |

|||||

| IMDB | 1.003***

(.108) |

.525***

(.089) |

2.115***

(.313) |

1.317***

(.197) |

2.827***

(.322) |

|||||

| Shortlisted | 1.165***

(.091) |

.997***

(.086) |

1.077***

(.084) |

.915***

(.084) |

2.721***

(.541) |

2.326***

(.244) |

2.253***

(.301) |

1.895***

(.201) |

2.496***

(.588) |

2.675***

(.449) |

| Constant | 5.790***

(.057) |

5.118***

(.278) |

.066 (.063) |

−1.316***

(.368) |

1.461***

(.223) |

−2.031**

(.770) |

2.177***

(.143) |

.408 (.463) |

6.797***

(.239) |

2.980***

(.687) |

| N | 1,681 | 1,670 | 1,681 | 1,670 | 1,681 | 1,670 | 1,681 | 1,670 | 1,681 | 1,670 |

Note: Robust standard errors (clustered by author) are reported in parentheses.

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

Cultural markets—and long-term retention in particular—are winner-take-most-markets, so the magnitudes of these effects are noteworthy. Figure 2 graphs the retention effects of winning the Booker, publishing with a conglomerate press, and the penalty for non-white authors publishing in the same year that a different non-white author wins. Overall, on average, the same-year penalty costs non-white authors 184 global library holdings, appearance in slightly less than one literary encyclopedia, appearances on 49 global syllabi, 30 citations, and over 3,000 ratings on GoodReads. In summary, results from Hypothesis 3 suggest significant long-term retention penalties for non-white authors whose books come out in years in which another non-white author is awarded.

Figure 2.

Same-Year Race Penalty

Alternative Accounts

One alternative account for our findings in relation to Hypothesis 3 may be that the Booker’s centrality in constructing the category of postcolonial fiction caused the field to be particularly reactive to its decisions for some authors and not others, thereby producing a same-year penalty for non-white authors.

We have four reasons to believe this alternative account does not explain our findings. First, under this alternative account, all groups of authors who were included in the category of postcolonial fiction (e.g., most centrally, white authors in former colonies, but also British, non-English authors) would face same-year penalties, but they do not. Put simply, we find a race effect and not a postcolonial author effect, nor do we find a same-year penalty for any other category of author. Second, this alternative explanation for Hypothesis 3 leaves our other findings unexplained (Hypotheses 2a and 2b, in particular), whereas tokenism explains both our prize process findings and our long-term retention findings. Third, our findings triangulate with how cultural creators from nondominant groups have described their experiences of tokenism in media industries (e.g., Eliza Skinner, Toni Morrison, Chester Himes, Olu Oguibe; although see also Tina Fey [2011:81], Joel Kim Booster [Wilstein 2021], and Samuel L. Jackson [Yuen 2016:54]). Individuals are of course not always able to accurately narrate their structural experiences, but our findings align with first-person experiences described across media industries.

Fourth, if same-year/same-category penalties in long-term retention of fiction more generally exist, we should find evidence for it in other prizes and awards. 15 To test for this, we look at the Orange Prize for Fiction (now known as the Women’s Prize for Fiction), which was launched to great fanfare in 1996 as a women’s-only prize to compete against the Booker. In contrast to the Booker, which is retrospectively understood as fomenting the category of postcolonial fiction, the Orange Prize is specifically earmarked for women authors, meaning a same-year penalty for women authors in its inaugural year should occur under this alternative account. First, we confirmed that the Orange Prize drove long-term retention for its inaugural winner, Helen Dunmore’s A Spell of Winter (which was also nominated for the Booker, but did not make the shortlist): compared to the median woman-authored novel in our data, A Spell of Winter has over three times as many library holdings (374 versus 195), 12 times as many citations (24 versus 2), five times as many encyclopedia appearances (5 versus 1), 100 times more GoodReads ratings (1,294 versus 13), and appears in four more syllabi (4 versus 0). Yet across all five of these retention indices, we find no same-year penalty for the women authors in our data in 1996. 16 These results are unexplainable from the framework of this alternative account, but they are easily explainable from a tokenism framework given that, as we will discuss (and as seen in models associated with Hypothesis 3), authors were not tokenized for being women during this period in British publishing.

A second alternative account is that our findings for Hypotheses 1a and 2a are explained by non-white authors facing higher barriers to nomination. We ran a t-test for review scores on GoodReads between novels by non-white and white authors and found no perceived quality differences (Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.8214). Yet, even if this alternative account were correct, it could still not explain our findings for Hypothesis 3, unless there were (by chance) also quality differences only in books by non-white authors in “on” and “off” years from a different non-white author winning, which we can also rule out (Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.2681). More generally, given that publishers are capped on the number of novels they can submit per prize cycle and those nominations are kept private (there is even a 20-year archival embargo on them), it is unlikely publishers would submit any books they believed to be of lesser quality.

Discussion

Research on tokenism has overwhelmingly focused on individual-level outcomes for those who are included but tokenized. We complement this research by directly focusing on tokenism as a structural system that excludes wider populations. We show that both the macro-level conditions of creative industries more generally, and the meso-level specifics of our case, create the conditions under which tokenism emerged. In this framework, we view tokenism as a measurable outcome of structural and cultural conditions that involves individuals from tokenized nondominant groups facing differently enabled and constrained trajectories for success than do individuals from non-tokenized groups. We also show the long-term consequences of tokenism for lower-status nondominant group members who were left out. Specifically, we find that the tokenization of a small number of non-white authors was coupled with the marginalization and exclusion of many more non-white authors—a finding in line with the origins of the concept within social movement organizing. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to statistically confirm longstanding critiques of tokenism in media systems using longitudinal, consecration-level data.

In our case, as a countermove against the rising dominance of U.S. publishers and due to the rising prestige of producing and consuming (perceived) authentic non-whiteness among the higher-status, educated classes, a particular form of tokenism emerged. Much like Mora’s (2014) findings on the making of a “Hispanic” identity category in the United States, within the umbrella label of postcolonial literature a pan-ethnic, pan-racial, pan-national, and pan-continental lumping of groups took shape based on shared language and relationship to a receding colonial empire. The category of postcolonial fiction also included white authors (in non-European former colonies, and at times also the British, non-English), but tokenism only occurred for non-white authors. It is in this cultural context of flattened non-whiteness that the success of an author from India writing about India draws interest to the work of a novelist who had grown up in Surrey, England, because of his (according to the author) “Japanese face” and “Japanese name” (Vorda and Herzinger 1991:134–35). In this formulation, women were not so much tokenized as they were “edged out” (Tuchman and Fortin 1989), as the domestic novel (in both senses of the word) was marginalized as passé and in creative decline (Strongman 2002). 17

The broader cultural foundations of the context also affected the shape this tokenism took. Like similar “highbrow” sectors across creative industries, the consolidation of a category through an awards system generated winner-take-all and winner-take-most outcomes (Caves 2000; Rossman and Schilke 2014; Thompson 2010), such that, as Laws (1975:51–52) notes, some “advantages” were conferred both for “the dominant group and for the individual who is chosen to serve as Token.” While this does not mean that non-white literary prize-winners were free from constrained social roles or the exaggeration of differences (see Rushdie 1992:61–70), the creation of a few non-white “postcolonial star-author[s]” (Nayar 2018:140) also came with global celebrity, wealth, and long-term literary acclaim (Brouillette 2007; Huggan 2002; Ponzanesi 2014). Yet, as has long been claimed by underrepresented creators within tokenistic media systems, non-white authors were “lodged in a hidden battle against one another for the few” slots available to them (Oguibe 2004:xii).

We see this work as contributing to several literatures. First, for work on organizations, work, and occupations, we believe that a multi-level approach that looks to the micro-level experiences of the tokenized and the meso- and macro-level consequences of tokenism as a structural system of exclusion is a useful path forward. Building off prior work (Turco 2010; Williams 1991), we believe this may also involve a more robust “cultural turn” in research on tokenism that more systematically looks to how different institutional contexts affect who is tokenized and how, as well as the shape that tokenism takes. More generally, we believe that research on tokenism has been somewhat narrowly oriented, reducing extensions and connections that could be made. For example, our findings on the privileging of a small and elite segment of an otherwise lower-status nondominant group may be commensurate with findings by Monk, Esposito, and Lee (2021) that the racial income penalty for perceived attractiveness flips for black and white women at the very top of the distribution. That is, for lower-status nondominant groups facing tokenism, there may be greater inequality within groups that does little to resolve the median level of inequality between groups; this may be a testable hypothesis for future research (Monk 2022).

We believe one reason the literature on tokenism has focused on individuals who are included-yet-tokenized is that included individuals are more locatable. Unlike identifying the one or two women working at the fire station and asking them about their experiences, there are different (and perhaps more significant) methodological challenges to identifying what happened to people not hired into a job, not admitted into a program, or not consecrated as worthy of institutional memory. Doing so likely requires longitudinal data that track people across career layers to avoid left-censoring on career success and inclusion (Lena and Lindemann 2014; Reilly 2017). These types of data, however, could be useful in identifying the occurrence of tokenism versus other processes (Chang et al. 2019).

For example, as women slowly break into the coaching ranks in the National Football League, researchers could compare teams with one woman coach at Time 1 versus those with no women coaches. The first research question could be if teams with one woman coach at Time 1 are more likely to employ two women coaches at Time 2 than teams with no women coaches at Time 1 are to employ one woman coach at Time 2. If not, this may suggest that tokenism is present within the system. Given that NFL coaches are recruited from lower levels of coaching (e.g., college, smaller semi-professional leagues, and intern and assistant positions), one could then establish the population from which women NFL coaches are being drawn, and confirm that at the NFL level, women coaches are not proportionality represented from the lower ranks. If they are proportionately represented, this may be a sign against tokenism occurring, whereas if underrepresented or overrepresented, this may be a second sign of tokenism occurring. From this “thin description” (Spillman 2014), researchers could then transition to qualitative data, capturing not only the experiences of women NFL coaches (the included-but-tokenized, as in the traditional approach) but also women football coaches who could have been selected for those tokenized slots but were not (who are otherwise typically invisible in research designs). The very masculinized cultural foundations under which American football operates could also lead to unexpected combinatory effects of tokenism on which women are included-yet-tokenized versus not, as based on different combinations of gender, race, and sexuality (Logan 2010; Pedulla 2014). We believe that moving forward, this type of multipronged research design is achievable and necessary.

We see our work as also contributing to emergent trends in the sociology of culture, and the study of media industries more broadly. First, culture scholars are increasingly sensitive to the interaction of categories and classification systems with sociodemographic difference, and the resulting effects on inequality (Gualtieri 2022; de Laat and Stuart 2023; Mears 2010; van Venrooij et al. 2022). As Erigha (2019, 2021) shows, “racial valuations” operate through an interaction between creators’ racial identities and the genre categories their works are slotted into. We show that in the construction of the category of postcolonial literature through the Booker Prize (Anand and Jones 2008), non-white authors end up pitted against each other for long-term consecration, despite the category encompassing multiple groups of authors. Extending Erigha’s framework, we believe that in tokenizing systems, racial valuations (or gendered evaluations, and so on) may be more relationally determined than are valuations for dominant groups (Wingfield 2013). For example, a mid-career superstar from a lower-status nondominant group may cause new entrants from the same nondominant group to be valued less because the “slot” for success is already filled. Alternatively, for tokenized groups sequestered into discrete genres, a rising tide may more forcefully lift all boats (i.e., in the wake of a superstar’s success, the genre and all those participating in it become fashionable), just as a falling star from a lower-status nondominant group may more forcefully drag down the entire solar system of nondominant group members as the entire category recedes from attention. That racial valuation may co-occur with hyper-relational valuation is, we believe, worthy of further study.

We believe our work also points to the limitations of prizes and awards as tools to diversify cultural fields, despite efforts to use them this way (Corse and Griffin 1997; English 2009; Grossman et al. 2021; Lauter 1991; Nishikawa 2021; Sapiro 2016). Although in our data non-white authors disproportionately shortlist for and win the Booker prize (and over the period also make up a bigger share of the nominations), in a supplementary analysis we find that publishers who were regularly submitting to the Booker prize did not increase the share of novels they published by non-white authors. 18 As such, to the degree that publishers were engaging in “prize-seeking” (Rossman and Schilke 2014), this was only a nomination strategy and stopped short of being an actual publication strategy that changed the overall composition of the field. 19 Alternative approaches to prizes may be more effective in creating broader change. For example, Ginsburgh and Weyers (2014) propose avoiding a final ranking with a single winner at the top and instead awarding all “short listers” equally. As artistic creation is a group endeavor (Becker 1982; Farrell 2003), others have proposed that prizes, awards, and government grants should be awarded to artistic collectives and groups, rather than individual artists and projects (Kalliney 2013; Rogers 2020). By moving “up” a level from individuals to groups, both strategies may have the latent effect of decreasing tokenism.

In closing, we note that the celebration of difference and signaling aesthetic appreciation for the otherwise marginalized has risen as a mark of social status among some segments of the population (Bryson 1996; Fine 2006; Fridman and Ollivier 2004; Hahl et al. 2017; Igarashi and Saito 2014; Lizardo 2005; Prieur and Savage 2013). Yet only slightly under the surface of this appreciation of difference is a more conventionally exclusionary hierarchy of tastes (Childress et al. 2021; Jarness and Friedman 2017; Johnston and Baumann 2009; Lena 2019; Sherman 2017; Warde and Gayo-Cal 2009). Simultaneously, within organizations and organizational fields there seems to be an increase in the “staging” (Thomas 2018) or “showcasing” (Shin and Gulati 2011) of diversity in ways that may be more surface level or merely presentational than they initially appear (Accominotti, Khan, and Storer 2018; Kang et al. 2016; Knight et al. 2022). We suspect tokenism might be “of a type,” and one form within a wider suite of comparable phenomena. From corporate boardrooms and colleges (Berrey 2015; Pippert et al. 2013) to everyday interactions on city streets, a conspicuous “gloss” or “façade” of cosmopolitanism (Anderson 2011:163, 291; Calhoun 2002; Tissot 2015) has grown ascendant across otherwise disparate arenas of social life. To be clear, the underlying reasons for these apparent similarities may be diffuse and conditioned on the local cultural context (e.g., to avoid external criticism, for profitability, as a signal of mimetic legitimacy, or as a sign of moral, cosmopolitan, or socially tolerant cultural capital, to name a few). Exploring proposed and elided mechanisms for similar phenomena across disparate cases may present an important step forward for research on tokenism and the continued prevalence of inequalities more broadly.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Naveen Ahmed, Damian Canagasuriam, Walid Fattah, Dawn Hall, Michelle Kang, Michèle Lamont, Neda Maghbouleh, Brian Moeran, Dave O’Brien, Craig Rawlings, Pat Reilly, Adam Slez, and the G7 Economic Sociology Working Group at University of Toronto. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the University of British Columbia, the University of California-Santa Barbara Culture Workshop, the Harvard University Culture and Social Analysis Workshop, and the Economic Sociology Seminar at MIT Sloan. All mistakes are our own.

Biography

Clayton Childress is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at University of British Columbia. His work on culture, taste, decision-making, and meaning-making has been published in American Sociological Review, American Journal of Sociology, Social Forces, Sociological Science, Poetics, and other venues. He is the author of Under the Cover: The Creation, Production, and Reception of a Novel, which won the 2018 Mary Douglas Award for Best Book in the Sociology of Culture.

Jaishree Nayyar is a student at the University of Ottawa Faculty of Law. She is interested in racialized and gendered tokenism and workplace discrimination in technology, law, and medicine.

Ikee Gibson is a graduate student in the Department of Sociology at University of Toronto. His research is on culture and networks, work, social groups, identity, and inequality.

Appendix

Simulation

In addition to estimating the models associated with Hypothesis 2a, we conducted a simulation that allowed us to calculate the probability of observing 13 or more years of non-white representation on the shortlist for the Booker Prize if non-white authors were selected from the pool of nominees by chance alone. For each iteration of the simulation, we treat the racial composition of the pool of nominees in each year between 1983 and 1996 as a random draw from a uniform distribution with a lower bound of 0.03 and an upper bound of 0.13. These bounds correspond to the minimum and maximum share of the nominee pool composed of non-white authors over the course of the period in question. Using this information, we then treat the number of non-white authors who were shortlisted in a given year as a random draw from a binomial distribution, with the simulated value of racial composition serving as the probability of a non-white author being shortlisted by chance alone. Repeating this process one million times, we find fewer than 30 instances in which non-white candidates were represented in at least 13 years, providing unambiguous support for the idea that the process of selecting non-white authors for the shortlist was extremely unlikely to have been driven by chance alone (less than a 1 in 30,000 chance).

Looking more closely at the results of the simulation, we find that the discrepancy between the observed and simulated data was overwhelmingly driven by the fact that we observe fewer years with an all-white shortlist than we would expect by chance alone. Indeed, the number of years without a non-white author on the shortlist (i.e., one) is just one-ninth of the expected value derived from the simulation. We find results of this magnitude in less than 0.003 percent of simulated datasets, suggesting the number of years with an all-white shortlist is significantly lower than we would expect by chance alone. The tendency to systematically avoid all-white shortlists is offset by a tendency to shortlist a single non-white author, as evidenced by the fact that the number of years with a single non-white author (i.e., 10) is roughly 2.4 times the average number observed in the simulation. We find results of this magnitude in less than 0.15 percent of simulated datasets, suggesting that the number of years with a single non-white author on the shortlist is also significantly higher than we would expect by chance alone.

It may be tempting to imagine that the propensity to shortlist a single non-white author per year is little more than a byproduct of “rounding up,” but we note that systematic rounding has no place in a chance process. This is especially true when considering a process related to the allocation of individuals belonging to a marginalized group. To the extent that judges felt compelled to avoid the large number of all-white shortlists that we would expect by chance alone, they are engaging in a form of tokenism. While the token authors tend to benefit insofar as they receive the prestige that comes with being shortlisted for (and then winning) the Booker Prize, this type of tokenism can also work to the detriment of non-white authors more generally, as we show in our main analyses.

Table A1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tables 1 & 4 | |||||

| Shortlist | 1,702 | .05 | .22 | 0 | 1 |

| Win | 1,702 | .01 | .09 | 0 | 1 |

| Libraries | 1,702 | 382.50 | 490.90 | 0 | 3740 |

| Encyclopedias | 1,702 | 1.34 | 1.77 | 0 | 7 |

| Syllabi | 1,702 | 11.50 | 73.40 | 0 | 2224 |

| Citations | 1,702 | 17.50 | 67.50 | 0 | 1274 |

| GoodReads | 1,702 | 1348.90 | 10877.30 | 0 | 341100 |

| Non-white Author | 1,696 | .08 | .27 | 0 | 1 |

| White English Author | 1,696 | .60 | .49 | 0 | 1 |

| Irish/Scottish/Welsh Author | 1,696 | .18 | .38 | 0 | 1 |