Abstract

High smoking prevalence and low quit smoking rates among African American adults are well-documented, but poorly understood. We tested a transdisciplinary theoretical model of psychopharmacological-social mechanisms underlying smoking among African American adults. This model proposes that nicotine’s acute attention-filtering effects may enhance smoking’s addictiveness in populations unduly exposed to discrimination, like African American adults, because nicotine reduces the extent to which discrimination-related stimuli capture attention, and in turn, generate distress. During nicotine deprivation, attentional biases towards discrimination may be unmasked and exacerbated, which may induce distress and perpetuate smoking. To test this model, this within-subject laboratory experiment determined whether attentional bias toward racial discrimination stimuli was amplified by nicotine deprivation in African American adults who smoked daily. Participants (N=344) completed a computerized modified Stroop task assessing attentional interference from racial discrimination-related words during two counterbalanced sessions (nicotine sated vs. overnight nicotine deprived). The task required participants to quickly name the color of discrimination and matched neutral words. Word-Type (Discrimination vs. Neutral) × Pharmacological State (Nicotine Deprived vs. Sated) effects on color naming reaction times were examined. Attentional bias toward racial discrimination-related stimuli was amplified in nicotine deprived (reaction time to Discrimination minus neutral stimuli: M[95%CI]=34.69[29.62–39.76] ms; d=0.15) compared to sated (M[95%CI]=24.88[19.84–29.91] ms; d=0.11) conditions (Word-Type×Pharmacological State, p<.0001). The impact of nicotine deprivation on attentional processes in the context of adverse societal conditions merit consideration in future science and intervention addressing smoking in African American adults.

Keywords: Attentional bias, smoking, racial discrimination, nicotine, African American adults

Introduction

While the prevalence of smoking in sociodemographic majority groups, such as White adults, have substantially declined in recent decades, reductions in smoking among racial/ethnic minority groups have been far slower (Jamal et al., 2018). Current smoking prevalence was lower in African American vs. White U.S. adults in previous decades (NCCDPHP, 2014), yet recent estimates now find higher smoking prevalence in African American (14.4%) than White adults (13.3%; Cornelius et al., 2022). Given such trends, significant gains in reducing the tobacco-related disease epidemic are increasingly dependent on understanding and reducing smoking in racial/ethnic minority groups, such as African American individuals (NCCDPHP, 2014).

While understanding and preventing smoking initiation is important for all populations, identifying factors that perpetuate smoking and interfere with quitting are especially salient for African American persons. In 2013–2018, the prevalence of past-year sustained smoking cessation was lower in African American adults than most other racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. (Leventhal, Dai, & Higgins, 2022). This pattern occurred despite African American adults reporting more motivation to quit smoking, smoking fewer cigarettes per day, and initiating smoking later in young adulthood as compared to other racial/ethnic groups (Alexander et al., 2016; Jamal, 2016; Leventhal et al., 2022; Schoenborn et al., 2013). To explain this paradox, it has been hypothesized that structural and environmental factors that perpetuate smoking are disproportionately experienced by African American adults, such as intensive, targeted marketing, high density of tobacco retail outlets in majority African American neighborhoods, reduced access to smoking cessation services, and other social determinants (U.S. National Cancer Institute, 2017).

One key social determinant implicated in smoking in African American adults is the experience of discrimination (Kendzor et al., 2014; Landrine & Klonoff, 2000; Parker, Kinlock, Chisolm, Furr-Holden, & Thorpe, 2016). Research examining why discrimination is associated with smoking often considers tobacco use in a manner similar to other health risk behaviors and overlooks the fact that nicotine is an addictive substance that exerts powerful control over behavior by altering the psychobiological state of an individual. A transdisciplinary framework that identifies how the societal context interacts with nicotine’s psychopharmacological effects to render the drug more addictive for African American persons (and other populations who face societal stressors) could inform new solutions to tobacco-related health disparities affecting African American populations.

The current study tests a transdisciplinary model that synthesizes perspectives from psychopharmacology and the social determinants of health (Leventhal, 2016). This model leverages established psychopharmacological evidence that nicotine promotes attention-filtering processes and can suppress the instinctual and automatic propensity to quickly shift and maintain attention toward threatening stimuli (i.e., ‘attentional bias’; Asgaard, Gilbert, Malpass, Sugai, & Dillon, 2010; Evans & Drobes, 2009; Kassel & Shiffman, 1997). Previous work suggests that individuals abstaining from smoking frequently report increased distraction and fixation on negative-related stimuli (Kalman, 2002), and administration of nicotine (vs. placebo) after overnight smoking abstinence decreases attentional bias towards negative-related stimuli (Rzetelny et al., 2008). This phenomenon may be clinically relevant to smoking cessation, given evidence that individuals with a greater inability to disengage attention from negative affective stimuli demonstrate stronger associations between negative affect experienced during nicotine deprivation and smoking relapse risk (Etcheverry et al., 2016). Cues signaling the perception or experience of social stressors, such as racial discrimination, can be appraised as negative and threatening and may promote an attentional bias response (Salvatore & Shelton, 2007). Hence, it is plausible that attentional processing of racial discrimination cues may also be subject to psychopharmacological modulation by nicotine deprivation.

The current model purports that nicotine suppresses the extent to which racial discrimination stimuli capture attention, are distracting, and in turn, generate distress. Nicotine may function as a temporary pharmacologic buffer against the adverse psychological effects of discriminatory social environments. For groups who frequently encounter racial discrimination, such as African American persons, this mechanism could increase the motivational value and addictiveness of smoking. Removal of this buffer after stopping smoking may result in an unmasking and exacerbation of one’s attentional bias toward discrimination cues. Hence, nicotine deprivation could potentially increase vulnerability to the attention-capturing effects of discrimination-related stimuli. This effect could interfere with quality of life by amplifying reactions to discrimination cues during acute states of nicotine abstinence that are either externally enforced (e.g., during work hours when smoking is not allowed, waking after overnight) or part of cessation attempts. The increased distraction and attentional interference by daily experiences of racial discrimination or reminders of such experiences during acute nicotine deprivation could increase motivation to resume smoking. When discrimination-induced attentional capture during nicotine deprivation heightens motivation to smoke, these states may be especially likely to elicit smoking reinstatement behavior among African American individuals. This is because neighborhoods with large populations who identify as African American may be saturated with smoking-related cues from targeted marketing and opportunities to purchase cigarettes in local neighborhoods that are densely populated with tobacco retailers (U.S. National Cancer Institute, 2017).

To test the above-mentioned model, this laboratory study of adult African Americans who smoke cigarettes examined if attentional bias toward racial discrimination stimuli differed between nicotine deprived and nicotine sated conditions. A computerized modified Stroop task (Ben-Haim et al., 2016) was used, which instructed participants to quickly name the color of racial discrimination and matched neutral words presented in varying colors. When a word’s meaning automatically captures attention, individuals become temporarily distracted away from the focal task of color identification. Consequently, the difference in color identification response times between discrimination-related and neutral word trials reflects the magnitude of attentional bias towards racial discrimination-related stimuli. We hypothesized that attentional bias towards racial discrimination-related stimuli would be potentiated in nicotine deprived vs. nicotine sated pharmacological states.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were African American non-treatment seeking individuals who smoked cigarettes daily (N=344) recruited from Los Angeles, CA, USA during 2013–2017 via advertisements announcing a study on reasons people smoke cigarettes. Inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) 18 years of age or older; (2) self-reported Non-Hispanic African American; (3) daily cigarette smoking for ≥2 years; (4) currently smoking ≥10 cigarettes per day. Exclusion criteria included: (1) current DSM-IV non-nicotine substance dependence determined by a structured clinical interview described below (to prevent non-nicotine substance withdrawal during study sessions, which required no use of psychoactive drugs within 24 hours of study sessions); (2) breath carbon monoxide (CO) levels < 10 ppm at intake (to exclude those over-reporting their smoking); (3) desire to substantially cut down or quit smoking in the next 30 days while participating in the study; (4) weekly use of anxiolytic medications and/or current use of anti-depressant, psychostimulant, or anti-psychotic drugs (because these drugs may modulate the psychopharmacological effects of nicotine deprivation); (5) daily use of non-cigarette tobacco products or nicotine replacement therapy (non-daily use permitted); (6) color blindness (due to inability to complete the modified Stroop task). Participants completed informed consent and were compensated $200. The University of Southern California Institutional Review Board approved the protocol.

Data source, sample size determinations, and availability of study materials

The current manuscript reports results of a tack-on experiment to a parent study on individual differences in tobacco withdrawal phenotypes in African American individuals (Leventhal et al., 2022). We added the racial discrimination Stroop measure into the parent study protocol midstream into data collection. Sample size for the current study was determined based on how many participants were still needed to meet study accrual goals for the parent study. Access to the study protocol, data, and statistical analysis code is available upon request to the corresponding author. This study was not preregistered.

Procedures

After an initial phone screening to determine preliminary eligibility, participants attended a baseline session involving informed consent, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Research Edition substance use disorder module in order to determine study eligibility (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams; 2002), and completing demographic and smoking history measures. Participants then attended two counterbalanced experimental sessions beginning approximately at 12:00 PM; one session was conducted after overnight (i.e., 16-hour) nicotine deprivation and one after smoking as usual (nicotine sated condition). The procedures at both experimental sessions were identical with the following exception: in the nicotine sated condition, participants were instructed to smoke as they normally would prior to their visit and were required to smoke one of their own cigarettes at the beginning of the laboratory session (to standardize for smoking recency and ensure participants were nicotine sated at testing). For the nicotine deprived condition, participants were instructed not to smoke after 8:00 PM the night before their visit. Participants were also instructed to avoid alcohol and use of any other psychoactive substances prior to sessions, except for caffeine, which participants were instructed to use according to their typical patterns.

Upon arrival (in the nicotine deprived condition) or after smoking their preferred brand of cigarette (in the nicotine sated condition), CO and breath alcohol assessments were conducted. Participants were required to biochemically confirm deprivation from alcohol (BrAC = 0.000) and, on the nicotine deprived condition, confirm nicotine deprivation (CO≤9 ppm) to continue the session. Those with CO >9 ppm at their deprived session (n=27) were considered non-deprived and rescheduled for a second attempt to complete their session on another day. Participants who did not meet CO criteria for nicotine deprivation at their second attempt were discontinued from further participation (n=2). Next, participants completed self-report measures of smoking urges and nicotine withdrawal symptomatology at a single time-point as a manipulation check. Participants then completed the modified Stroop task that served as the primary outcome of this study.

Measures

Demographic and Smoking Characteristics.

To describe the overall sample, an author-created questionnaire assessed demographics and the Smoking History Questionnaire (SHQ) measured smoking characteristics (i.e., cigs/day, preference for mentholated cigarettes) at the baseline session. The Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND) was administered to determine the severity of nicotine dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991).

Tobacco Exposure and Withdrawal Symptoms.

As a manipulation check, CO values and self-report measures of nicotine withdrawal symptoms and urges to smoke were administered to determine whether these outcomes that are typically sensitive to nicotine deprivation manipulation (Aguirre, Madrid, & Leventhal, 2015; Bello et al., 2015) were affected by the study manipulation described above. The 10-item Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU; Cox et al., 2001) assessed intention and urge to smoke experienced “right now” (e.g., “I have an urge for a cigarette.”) on 6-point Likert scales, which were averaged to generate a mean composite. A variant of the 11-item Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS; Hughes & Hatsukami, 1986) evaluated withdrawal symptoms experienced “so far today” (i.e., craving, irritability, anxiety, concentration problems, restlessness, impatience, hunger, cardiovascular and autonomic activation, drowsiness, and headaches) on 6-point Likert scales. A mean score across items was computed.

Modified Stroop Task.

Participants were instructed that they would be presented with words one at a time, with the font displayed in varying colors on a computer monitor, and that their task was to indicate the color of the word as quickly and as accurately as possible while ignoring the meaning of the words by pressing one of three colored buttons (i.e., red, green, blue) on the keyboard. Words including 13 racial discrimination-related words (e.g., segregation, racist) and 13 neutral words (e.g., information, across) matched for length and usage frequency (Francis & Kucera, 1967) were displayed. The specific words, word length, use frequency, and participants’ mean response times are reported in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 in the online supplement.

We assessed the “Stroop effect”—tendency to experience difficulty (conflict or interference) naming a physical color when it is used to spell the name of a different color or word (the incongruity effect; Stroop, 1935)—by comparing the mean response time on racial discrimination-related word trials with mean response time on neutral-matched trials, which served as the primary outcome of the study. Before the experimental trials, participants were presented with a practice block of 42 trials where they were asked to identify the color for a string of letters (e.g., MMMMMMMMMM) with corrective feedback (tone sounded for error responses). Following the practice trials, 78 experimental trials with corrective feedback were presented in two blocks in a fixed sequential sequence. Block 1 had 39 neutral-matched word trials (all 13 neutral words presented once in each of the 3 colors). Block 2 had 39 racial discrimination-related word trials (13 words presented in each color). The order of the word-color combinations within each block was randomly assigned for each participant. The blocked sequential format was chosen based on prior work showing that carry-over interference effects from trial to trial can suppress Stroop effects in mixed formats and are mitigated in blocked formats when the valanced stimulus follows the neutral stimulus block (Waters, Sayette, Franken, & Schwartz, 2005). As in prior modified Stroop task research (Waters et al. 2003), we structured the task in a fixed order, such that the neutral stimulus block appeared prior to the salient (discrimination) stimulus block for all participants and in both deprived and sated conditions. This ordering prevents block-to-block carryover effects that can suppress Stroop effects, which we felt outweighed concerns resulting from not counterbalancing presentation of blocks, such as confounding with fatigue effects that can be addressed via sensitivity analyses. See Ben-Haim et al., 2016 and Rohsenow & Niaura, 1999 for similar arguments in emotional Stroop task and drug cue reactivity studies, respectively.

For each trial, the word was presented, and responses were permitted until the correct colored-key was pressed or until 3000 ms elapsed and was then followed by a blank screen for 500–1000 ms before the next trial. Participants had a 10 second break in between the neutral and discrimination-related word blocks. Participants were tested individually on a laboratory computer with a high resolution and the words presented at the monitor’s center. Response time was recorded within millisecond resolution and stimuli were presented electronically using E-Prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Data Analysis

Preliminary analyses involved calculating descriptive statistics for demographics and cigarette smoking characteristics. We utilized paired sample t-tests as a manipulation check to assess whether the nicotine deprived vs. nicotine sated conditions impacted each tobacco withdrawal symptom (i.e., urges to smoke and composite withdrawal symptoms) and report internal consistency estimates of each study outcome by pharmacological state (Cronbach αs; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of Pharmacological Manipulation on Tobacco Withdrawal Outcomes in Overall Sample

| Measures | Nicotine Deprived Condition |

Nicotine Sated Condition |

Contrast |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | α | M (SD) | α | t | d | |

|

| ||||||

| Carbon Monoxide (ppm)a | 4.57 (2.17) | - | 16.72 (8.36) | - | −27.62 | −1.49† |

| Smoking Urgeb | 3.05 (1.24) | 0.92 | 1.29 (1.33) | 0.95 | 24.25 | 1.32† |

| Nicotine Withdrawal Symptomsc | 1.66 (1.12) | 0.89 | 0.83 (0.81) | 0.83 | 15.05 | 0.81† |

|

| ||||||

| Stroop Task Reaction Time (ms) | M (SE) | M (SE) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Racial Discrimination Words | 807.54 (6.77) | 798.86 (6.77) | ||||

| Neutral-Matched Words | 772.84 (6.77) | 773.99 (6.77) | ||||

Note: N = 344.

Breath carbon monoxide (parts per million).

Score on Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (10 items; range of mean score 0–5)

Score on Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (11 items; range of mean score 0–5)

Response Time (milliseconds)

α = Cronbach’s alphas used to reflect internal consistency estimates for each measure. Cohen’s d = Effect size used to indicate the standardized difference between two means.

p <.0001.

Per prior research (Oliver & Drobes, 2015), we created a multilevel dataset for our primary analysis in which each of the participant’s 78 experimental trials on the modified Stroop task were treated as individual observations nested within participants. The response time outcome provided 53,664 data points (78 observations × 2 abstinence states × 344 participants) analyzed in multilevel linear regression models that included independent, fixed effects of pharmacological state (nicotine deprived vs. nicotine sated), word type (racial discrimination-related vs. neutral-matched), and the word type × pharmacological state interaction term with the response time for each trial serving as the dependent variable. Random intercepts were utilized in models and within-subject variables (i.e., condition, word type) were treated as fixed effects; additional models were also conducted by treating within-subject variables as random effects, which exhibited no significant differences from initial models (significant values were relatively consistent across both models). Primary analyses were limited to trials with correct responses (error trials constituted 4.99% of the total trials; n of total trials = 2,678). Based on a previous study (Bertsch, Böhnke, Kruk, & Naumann, 2009), participant’s individual response times below or exceeding overall sample mean response times +/−2 SDs (≤ 166.50 ms or ≥ 1,496.42 ms) were identified as outliers (n trials=2,309) and removed from the dataset, which left a final analytic sample of 48,677 trials.

Significant interaction effects were followed by simple effect analyses that assessed word type effects within each pharmacological state condition and then assessed pharmacological state effects within each word type condition. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore the robustness of results and are described in greater detail in the Results section (see online supplement content). Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24 (IBM Corp., 2020) with an alpha level set to 0.05 two-tailed; effect sizes for fixed effects were reported using unstandardized regression coefficients as suggested in prior work (Lorah et al., 2018) and Cohen’s ds (Hedges, 2007).

RESULTS

Study Sample

Among individuals who completed an intake session (N=520), 478 (92.9%) consented to participate and were eligible. Of these, 83 (17.4%) did not complete both experimental visits. Of the remaining 395, Stroop task data was unavailable for 51 participants due to data saving errors, data backup failures, or not completing the task during sessions (see online supplement Figure 1 for ns by non-participation reason).

The analytic sample (N=344) was 65.9% male sex with a mean age of 51.10 years (SD=10.4). Participants reported, on average, moderate nicotine dependence levels on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (5.93[SD=1.8]), smoking daily for 30.5 years (SD=11.6), and currently smoking 14.8 (SD=7.5) cigarettes per day; 61% smoked mentholated cigarettes. 63% of participants reported an annual income of less than $15,000, approximately 48.7% had a high school diploma or GED or lower level of educational attainment, and 45.3% were currently unemployed.

Check of Pharmacological Manipulation

To determine whether participants complied with instructions to either avoid smoking for 16 hours (deprived) or continue smoking (sated) on the respective study visits, we compared outcomes indicative of nicotine exposure across conditions. Breath carbon monoxide (CO; a biomarker of recent smoking) was reduced and urge to smoke and nicotine withdrawal symptoms were increased during nicotine deprived (vs. sated) sessions (see Table 1).

Attentional Bias Toward Racial Discrimination-Related Stimuli, by Pharmacological State

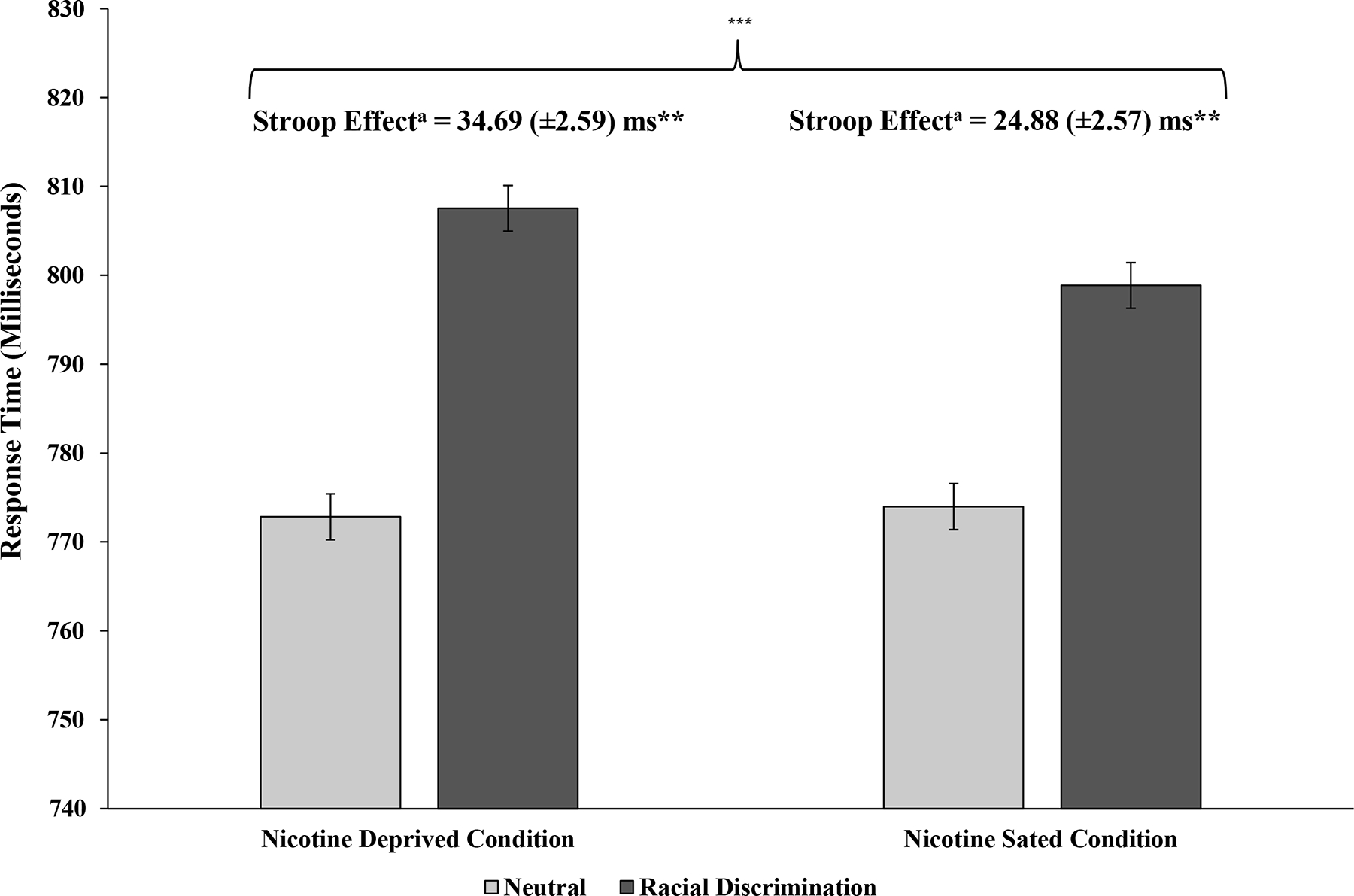

M (±SE) response times for discrimination-related and neutral word trials, by pharmacological state, are reported in Table 1 and Figure 1. A main effect of word type was observed (F[1, 48,333.45]=266.190; p<.0001; d = 0.13), such that participants were, on average, 29.74 (95% CI=26.17, 33.31) milliseconds (ms) slower to name the color of racial discrimination-related (vs. neutral-matched) words, collapsed across nicotine deprived and sated conditions. A main effect of pharmacological state was also observed, with slower response times during nicotine deprived (vs. sated) conditions, collapsed across word types (F[1, 48,356.58]=3.91; p = .04; d = 0.02). A significant word type × pharmacological state interaction was found (F[1, 48,330.79]=7.25; p=.007) driven by a significantly larger difference in response times to racial discrimination-related (vs. neutral) words in the nicotine deprived condition (difference: M=34.69 ms, 95% CI=29.62, 39.76; p<.0001; d = 0.15) than the corresponding difference in reaction times between discrimination-related and neutral words observed in the nicotine sated condition (difference: M=24.88 ms, 95% CI=19.84, 29.91; p<.0001; d = 0.11; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean (±SE) Response Times for Racial Discrimination-Related and Neutral-Matched Word Trials, by Pharmacological State

Note. N=344. aStroop effects = Mean Response Time on Racial Discrimination-Related Trials – Mean Response Time on Neutral-Matched Trials. **Significant Stroop effect (Discrimination-related vs. neutral-matched difference) within respective study condition. ***Significant difference in magnitude of Stroop effects by pharmacological state (p = .007; word type × pharmacological state interaction).

Sensitivity Analyses to Test the Influence of Non-Specific Processes on Study Findings.

Additional sensitivity analyses found that nicotine deprivation-induced potentiation of attentional bias towards racial discrimination-related stimuli largely generalized across most discrimination-neutral word pairs and was not driven by one or two specific word pairs (Online Supplement Table 3). Furthermore, the primary word type × pharmacological state interactions were robust after removing outlier responses (online supplement Figure 2) or removing error responses (online supplement Figure 3). Analyses of order of completion of deprived and sated conditions found that the word type × pharmacological state interaction was stronger when participants completed the sated condition prior to the deprived condition (i.e., deprivation-induced augmentation of attentional bias toward discrimination-related stimuli becomes stronger during the second visit).

Because discrimination-related trials always followed neutral trials, the word type or word type × pharmacological state effects could be confounded with non-specific processes that accrue with successive trial completion (regardless of the semantic content of the word presented), such as within-session fatigue, boredom, or other effects, which could possibly also be altered by nicotine deprivation. To address this, sensitivity analyses were conducted with Stroop task data including only the last 13 neutral trials and the first 13 discrimination trials. Results were consistent with our primary analysis (see online supplement Figure 4), indicating that response slowing on discrimination-related vs. neutral trials and the potentiation of this effect by nicotine deprivation was driven by processing the semantic content of the words.

DISCUSSION

This study provides new evidence that the propensity to automatically allocate attention toward stimuli associated with racial discrimination is amplified by acute nicotine deprivation, particularly among African American adults who smoke cigarettes daily. These findings cohere with findings that smoking abstinence may increase attentional distraction toward general negative-related stimuli (Kalman, 2002; Etcheverry et al., 2016) and extend them to a socially-salient category of aversive stimuli. The effect demonstrated here might reflect the unmasking of nicotine’s acute attention-filtering properties that help suppress the instinct to automatically attend and react to threatening stimuli.

The unstandardized and standardized effect estimates reflect small magnitudes of attentional bias and differences by pharmacological state. This could mean that the clinical significance of the results may be modest. We caution against such interpretations. While the interference effect may be small, African American persons may experience exposure to discrimination on a highly frequent basis. Hence, the cumulative effect of repeated instances of interference from discrimination when deprived from nicotine could be substantial. Additionally, the emotional Stroop task does not have robust reliability due its reliance on difference in reaction times (Dresler et al., 2012). Hence, it is difficult to draw strong inferences from quantitative effect size estimates from this research.

Sensitivity analyses also showed that differences in attentional bias toward discrimination words by pharmacological state were not accounted for by within-session fatigue or impacted by outliers. Results also found that the main results generalized to trials including error responses and across most discrimination-related words displayed in the task. Order of completion analyses found that deprivation-induced augmentation of attentional bias toward discrimination-related stimuli was stronger during the second visit as qualified by a three-way interaction of pharmacological state, word type, and order. It is possible that this is a chance finding given that this effect was not hypothesized. If we were to have conducted correction for multiple testing to control type-I error of all tests, the primary 2-way interaction ps<.0001 would remain significant but this three-way interaction with order would not remain statistically significant. While we did not hypothesize such order effects, we would have anticipated the opposite pattern because participants tend to improve performance on the Stroop task with additional practice as they become able to consciously override their instinct to process the meaning of words and instead focus on the words’ color (Dulaney & Rogers, 1994). Practice effects would presumably suppress effects of experimental manipulations on attentional bias. However, the direction of the three-way interaction effect was opposite to practice-induced effect dissipation. After participants already completed the task once on their first visit, difference in attentional bias between deprived and sated conditions widened during the second visit. If it is not merely a type-I error, this effect could indicate that deprivation-induced augmentation of attentional bias toward discrimination may endure across time and repeated exposure to discrimination-related stimuli.

In a reductionist view, this study merely represents a specific application of a generalizable psychopharmacological phenomenon. We expect that a properly designed experiment will show nicotine-induced alteration of attentional bias with any tailored, highly relevant stimulus that is perceived as threatening in a particular population. For example, studies examining attentional bias towards general negative affect valence words (e.g., upset, distressed) or those related to specific threatening categories (e.g., earthquake, hurricane) might show exacerbation by nicotine deprivation. What makes the results of the study significant is: (1) the threatening stimulus utilized in this experiment is highly salient to the societal milieu; and (2) the population studied faces staggering tobacco-related health disparities (Fu et al., 2008; Parker, Horowitz, & Mahl, 2016; Parker et al., 2016).

Nicotine’s putative capability to reduce attention directed toward cues that signal racial discrimination may be of value to groups who frequently encounter discrimination, such as African American populations. While some discrimination is overt, discriminatory cues can also be subtle, such as microaggressions—verbal or nonverbal slights or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostility toward persons of a marginalized group. At minimum, discriminatory cues are distracting or annoying. At maximum, discrimination is distressing and traumatic. Racial discrimination is pervasive. Nicotine may provide a temporary and controllable pharmacological reprieve from discrimination and other societal stressors that may otherwise be unavoidable or unrelenting (Parker, Kinlock, et al., 2016). Consequently, abstaining from smoking may be unduly stressful and difficult to maintain for groups, such as African American persons, whose social environments are saturated with racial discrimination. Prior studies have shown that the frequency of experiencing discrimination is associated with the severity of nicotine dependence and motivation to smoke to enhance mood and cognition (Kendzor et al., 2014). The current study suggests a pharmacological mechanism potentially underlying such associations. There could be substantial impact of such mechanisms on smoking behavior for African American individuals who may be bombarded with smoking-related stimuli and access to cigarettes due to targeted marketing of cigarettes to African American populations (U.S. National Cancer Institute, 2017).

Study limitations warrant consideration. First, the words used here denoted universal concepts to ensure that participants would associate the study stimuli with discrimination (see online supplement Table 3). Exposure to these discrimination-related stimuli does not simulate exposure to actual discriminatory experiences that minority groups face in the real world. Second, this study focused on African American adults who smoke and omitted a comparison group. While the findings were clear in this sample, it is unclear whether nicotine-induced alteration of attentional bias toward discrimination-related cues is observed in White adults who smoke or other minoritized populations. Third, nicotine deprivation was experimentally manipulated over a short duration of time (16 hours) and not part of a self-motivated quit attempt, thus, our findings may not generalize to those making quit attempts. However, tobacco withdrawal during experimentally manipulated nicotine deprivation may be representative of withdrawal during smoking cessation, which suggests potential generalizability of the current findings (Strong et al., 2011). Fourth, like many modified Stroop task studies, it is unclear whether the effect observed in this study is mediated by pure cognitive attentional disruption or emotional mechanisms of distress that interfered with color naming. While both mechanisms are clinically important, it is of scientific interest to disaggregate these component processes in future research. Fifth, future work is warranted to compare effects of nicotine deprivation on attentional processing of discrimination-related words with attentional processing of other threatening stimuli.

Limitations notwithstanding, results from this study could open new avenues for investigating how societal factors transect with the psychobiological effects of addictive behaviors to underpin health disparities. Disparities in addiction to other drugs besides nicotine is prominent (Burlew et al. 2021). Hence, investigating whether other drugs of abuse may modify responses to societal stressors would be of interest and predicted to operate differently across drugs with different effects on attentional processes (e.g., cocaine versus alcohol). If the findings were replicated, extended, and generalized to other contexts, they could inform paradigms for addiction treatments for minority populations. For example, the heightened psychological vulnerability that people who face discrimination experience in the short term when trying to quit could be a critical topic of discussion between African American patients and their providers during smoking cessation counseling (Webb Hooper et al., 2013; Webb Hooper, Carpenter, Payne, & Resnicow, 2018). Additionally, clinicians should be aware that the experience of discrimination could be especially bothersome, distracting, and distressing during smoking cessation for African American patients; hence, clinicians should be attuned to assess and address these topics during cessation treatment. Additionally, future research of whether use of products that impact nicotine satiety alter responses to discrimination-related cues might be useful. Indeed, a recent study found that electronic nicotine delivery systems reduced cigarettes smoked per day and carcinogen exposure in African American persons (Pulvers et al., 2020). Furthermore, combination interventions that include psychosocial support that bolsters coping strategies for dealing with aversive societal experiences combined with pharmacological support could be useful to test for improving quit rates in African American populations. These approaches alongside other transdisciplinary, multi-layered research and intervention approaches may be well-suited for counteracting expanding tobacco-related health disparities facing African Americans and other minoritized populations.

Supplementary Material

Public Health Significance:

This study indicates that cues linked with racial discrimination may be more distracting to African American adults who smoke cigarettes after they stop smoking. Clinicians treating this population should be aware that the acute psychological effects of discrimination could be heightened during quit smoking attempts or other periods when smoking is not possible.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from the American Cancer Society (grant number RSG-13–163-01), National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant numbers K08-DA025041; K24–048160; T32 DA016184), and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (grant number DGE-1418060). Funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. None of the authors report a conflict of interest related to submission of this manuscript. Hypotheses and results of this manuscript were presented at the 24th annual scientific meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco in Baltimore, Maryland. Access to the study protocol, data, and statistical analysis code is available upon request to the corresponding author. This study was not preregistered.

References

- Aguirre CG, Madrid J, & Leventhal AM (2015). Tobacco withdrawal symptoms mediate motivation to reinstate smoking during abstinence. Journal of abnormal psychology, 124(3), 623–634. 10.1037/abn0000060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander LA, Trinidad DR, Sakuma KL, Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Clanton MS, Moolchan ET, & Fagan P (2016). Why We Must Continue to Investigate Menthol’s Role in the African American Smoking Paradox. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 18 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S91–S101. 10.1093/ntr/ntv209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgaard GL, Gilbert DG, Malpass D, Sugai C, & Dillon A (2010). Nicotine primes attention to competing affective stimuli in the context of salient alternatives. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology, 18(1), 51–60. 10.1037/a0018516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello MS, Pang RD, Cropsey KL, Zvolensky MJ, Reitzel LR, Huh J, & Leventhal AM (2015). Tobacco Withdrawal Amongst African American, Hispanic, and White Smokers. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 18(6), 1479–1487. 10.1093/ntr/ntv231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Haim MS, Williams P, Howard Z, Mama Y, Eidels A, & Algom D (2016). The Emotional Stroop Task: Assessing Cognitive Performance under Exposure to Emotional Content. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE, (112), 53720. 10.3791/53720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch K, Böhnke R, Kruk MR, & Naumann E (2009). Influence of aggression on information processing in the emotional stroop task--an event-related potential study. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 3, 28. 10.3389/neuro.08.028.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlew K, McCuistian C, & Szapocznik J (2021). Racial/ethnic equity in substance use treatment research: the way forward. Addiction science & clinical practice, 16(1), 50. 10.1186/s13722-021-00256-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, & Homa DM (2022). Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 71(11), 397–405. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, & Christen AG (2001). Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 3(1), 7–16. 10.1080/14622200020032051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresler T, Ehlis AC, Hindi Attar C, Ernst LH, Tupak SV, Hahn T, Warrings B, Markulin F, Spitzer C, Löwe B, Deckert J, & Fallgatter AJ (2012). Reliability of the emotional Stroop task: an investigation of patients with panic disorder. Journal of psychiatric research, 46(9), 1243–1248. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulaney CL, & Rogers WA (1994). Mechanisms underlying reduction in Stroop interference with practice for young and old adults. Journal of experimental psychology. Learning, memory, and cognition, 20(2), 470–484. 10.1037//0278-7393.20.2.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DE, & Drobes DJ (2009). Nicotine self-medication of cognitive-attentional processing. Addiction biology, 14(1), 32–42. 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etcheverry PE, Waters AJ, Lam C, Correa-Fernandez V, Vidrine JI, Cinciripini PM, & Wetter DW (2016). Attentional bias to negative affect moderates negative affect’s relationship with smoking abstinence. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 35(8), 881–890. 10.1037/hea0000338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, & Williams J Structured clinical interview for DSM-IVTR axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP). 2002. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Francis WN, & Kucera H (1967). Computational analysis of present-day American English. Providence, RI: Brown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fu SS, Kodl MM, Joseph AM, Hatsukami DK, Johnson EO, Breslau N, Wu B, & Bierut L (2008). Racial/Ethnic disparities in the use of nicotine replacement therapy and quit ratios in lifetime smokers ages 25 to 44 years. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 17(7), 1640–1647. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, & Fagerström KO (1991). The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British journal of addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV (2007). Effect Sizes in Cluster-Randomized Designs. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 32(4), 341–370. 10.3102/1076998606298043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, & Hatsukami D (1986). Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Archives of general psychiatry, 43(3), 289–294. 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 27.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, & Graffunder CM (2016). Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2005–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 65(44), 1205–1211. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, Homa DM, Babb SD, King BA, & Neff LJ (2018). Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 67(2), 53–59. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6702a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman D (2002). The subjective effects of nicotine: methodological issues, a review of experimental studies, and recommendations for future research. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 4(1), 25–70. 10.1080/14622200110098437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, & Shiffman S (1997). Attentional mediation of cigarette smoking’s effect on anxiety. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 16(4), 359–368. 10.1037//0278-6133.16.4.359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Reitzel LR, Rios DM, Scheuermann TS, Pulvers K, & Ahluwalia JS (2014). Everyday discrimination is associated with nicotine dependence among African American, Latino, and White smokers. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 16(6), 633–640. 10.1093/ntr/ntt198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, & Klonoff EA (2000). Racial discrimination and cigarette smoking among Blacks: findings from two studies. Ethnicity & disease, 10(2), 195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM (2016). The Sociopharmacology of Tobacco Addiction: Implications for Understanding Health Disparities. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 18(2), 110–121. 10.1093/ntr/ntv084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Conti DV, Ray LA, Baurley JW, Bello MS, Cho J, Zhang Y, Pester MS, Lebovitz L, Budiarto A, Mahesworo B, & Pardamean B (2022). A genetic association study of tobacco withdrawal endophenotypes in African Americans. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology, 30(5), 673–681. 10.1037/pha0000492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Dai H, & Higgins ST (2022). Smoking Cessation Prevalence and Inequalities in the United States: 2014–2019. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 114(3), 381–390. 10.1093/jnci/djab208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorah J (2018). Effect size measures for multilevel models: Definition, interpretation, and TIMSS example. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 6(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver JA, & Drobes DJ (2015). Cognitive manifestations of drinking-smoking associations: preliminary findings with a cross-primed Stroop task. Drug and alcohol dependence, 147, 81–88. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker K, Horowitz J, & Mahl B (2016). On views of race and inequality, blacks and whites are worlds apart. Social Trends, Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Parker LJ, Kinlock BL, Chisolm D, Furr-Holden D, & Thorpe RJ Jr (2016). Association Between Any Major Discrimination and Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adult African American Men. Substance use & misuse, 51(12), 1593–1599. 10.1080/10826084.2016.1188957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychology Software Tools, Inc. [E-Prime 3.0]. (2016). Retrieved from https://support.pstnet.com/.

- Pulvers K, Nollen NL, Rice M, Schmid CH, Qu K, Benowitz NL, & Ahluwalia JS (2020). Effect of Pod e-Cigarettes vs Cigarettes on Carcinogen Exposure Among African American and Latinx Smokers: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open, 3(11), e2026324. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, & Niaura RS (1999). Reflections on the state of cue-reactivity theories and research [see comment]. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 94(3), 343–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzetelny A, Gilbert DG, Hammersley J, Radtke R, Rabinovich NE, & Small SL (2008). Nicotine decreases attentional bias to negative-affect-related Stroop words among smokers. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 10(6), 1029–1036. 10.1080/14622200802097514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore J, & Shelton JN (2007). Cognitive costs of exposure to racial prejudice. Psychological science, 18(9), 810–815. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01984.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, & Peregoy JA (2013). Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2008–2010. Vital and health statistics. Series 10, Data from the National Health Survey, (257), 1–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Leventhal AM, Evatt DP, Haber S, Greenberg BD, Abrams D, & Niaura R (2011). Positive reactions to tobacco predict relapse after cessation. Journal of abnormal psychology, 120(4), 999–1005. 10.1037/a0023666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of experimental psychology, 18(6), 643. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. National Cancer Institute. (2017) A Socioecological Approach to Addressing Tobacco-Related Health Disparities. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph 22. NIH Publication No. 17-CA-8035A. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Waters AJ, Shiffman S, Sayette MA, Paty JA, Gwaltney CJ, & Balabanis MH (2003). Attentional bias predicts outcome in smoking cessation. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 22(4), 378–387. 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AJ, Sayette MA, Franken IH, & Schwartz JE (2005). Generalizability of carry-over effects in the emotional Stroop task. Behaviour research and therapy, 43(6), 715–732. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb Hooper M, Larry R, Okuyemi K, Resnicow K, Dietz NA, Robinson RG, & Antoni MH (2013). Culturally specific versus standard group cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation among African Americans: an RCT protocol. BMC psychology, 1(1), 15. 10.1186/2050-7283-1-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb Hooper M, Carpenter K, Payne M, & Resnicow K (2018). Effects of a culturally specific tobacco cessation intervention among African American Quitline enrollees: a randomized controlled trial. BMC public health, 18(1), 123. 10.1186/s12889-017-5015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.