Abstract

After the recent hard attempts felt on a global scale, notably in the health sector, the steady efforts of scientists have been materialized in maybe one of the most expected findings of the last decades, i.e. the launching of the COVID-19 vaccines. Although it is not our goal to plead for vaccination, as the decision in this regard is a matter of individual choice, we believe it is necessary and enlightening to analyze how one's educational status interferes with COVID-19 vaccination. There are discrepancies between world states vis-à-vis their well-being and their feedback to crises, and from the collection of features that can segregate the states in handling vaccination, in this paper, the spotlight is on education. We are referring to this topic because, generally, researches converge rather on the linkage between economic issues and COVID-19 vaccination, while education levels are less tackled in relation to this. To notice the weight of each type of education (primary, secondary, tertiary) in this process, we employ an assortment of statistical methods, for three clusters: 45 low-income countries (LICs), 72 middle-income countries (MICs) and 53 high-income countries (HICs). The estimates suggest that education counts in the COVID-19 vaccination, the tertiary one having the greatest meaning in accepting it. It is also illustrated that the imprint of education on vaccination fluctuates across the country groups scrutinized, with HICs recording the upper rates. The heterogeneity of COVID-19 vaccination-related behaviors should determine health authorities to treat this subject differently. To expand the COVID-19 vaccines uptake, they should be in an ongoing dialogue with all population categories and, remarkably, with those belonging to vulnerable communities, originated mostly in LICs. Education is imperative for vaccination, and it would ought to be on the schedule of any state, for being assimilated into health strategies and policies.

Keywords: Primary education, Secondary education, Tertiary education, COVID-19 vaccination, Health strategies, LICs, MICs, HICs

1. Introduction

Health crises are disproportionately reflected in the countries of the world. Beyond the fact that they can involve some of the most destructive effects, even in economic terms, they also leave a strong trace on the psycho-emotional side of the population. Illness and human losses impinge on any community, and the more acute they are, the more pronounced the level of social turmoil. In the case of COVID-19 pandemic, the reality is quite bleak, considering the colossal number of deaths, all around the world [1,2]. Without specific vaccines, health systems would most likely collapse amid such an extremely critical situation [[3], [4], [5]]. Initially, these were available in the developed countries and later, in the emerging ones. HICs had faster access to vaccines, thanks to the equipment and resources they own; anyway, even if the involvement of governments, medical institutions and international organizations was intense, in order to ensure fair and generalized distribution of vaccines, at global level, there are large vaccination disparities, which led to additional measures, such as the introduction of the COVID-19 vaccination certificates [[6], [7], [8]]. Because of this, it is vital to identify the reasons why in certain places there are low inclinations towards vaccination, and, concurrently, to address the factors that contribute to such behaviors.

Time has proved that there are advantages that come along with the vaccination process, and it is worth mentioning here that, annually, the effectiveness of vaccines against various diseases means preventing millions of deaths worldwide [9]. For the coronavirus, it has been demonstrated that it can be inhibited by vaccination, which can also reduce the mortality rate [[10], [11], [12], [13]]. Although, frequently, the socio-economic determinants (income, living conditions, life quality) are linked to the presumption of being able to vaccinate, as the purchase of some vaccines implies costs, there are also cultural reasons that cause distictions between healthcare systems [14,15]. Vaccination is not embraced by everyone; a plenty of subjective and objective elements can influence it, and, in this research, we seek to spotligh on education. The dilemma arises, however, when it comes to vaccination coverage in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the scarcity of resources weakens aspects pertaining to public health. In addition, the precariousness of knowledge about vaccination makes the openness of parents towards it to be quite reduced, children imitating this behavior later, chiefly if there is no interest for education [16]. Without vaccination, socially disadvantaged communities, which are, usually, associated with a lower education, may suffer the most from contracting a disease [17]. Largely, the following trend was noted in the literature: higher levels of education contribute to greater vaccination rates, and in order to raise them even more, actions should be tailored to the features of the target groups and communities [18,19]. As a consequence, there is a need to intensify research aimed at analyzing the peculiarities of LMICs in terms of vaccination and at disseminating information about its drivers, predominantly among the population with poor education.

The relevance of the conditionalities between education and health cannot be questioned: first, because, in general, a population with a higher education level tends to be more focused on health monitoring, having at its disposal the means to maintain it adequately; then, better health allows people to increase their productive capacity, including by obtaining educational results that ease the access to better and well-paid jobs. Combined, they can bring more extensive benefits, such as a higher life expectancy, greater chances for professional success or the strengthening of social capital. The family beliefs can be transmitted from one generation to the next, and if some principles related to health protection are inoculated from childhood, as a panacea for a long life, this could mean a bigger probability of accepting the vaccination, regardless of the forms of the disease for which they are applied. However, these specifications blur their significance if we refer to deeply fragmented territories from a socio-economic or political point of view. Where people live on the edge of poverty, where armed conflicts are frequent, or where political regimes do not allow personal choices, the situation changes dramatically. Studying more countries, from various continents, can highlight strong COVID-19 vaccination-related inequalities, resulting from educational differences.

A wide space has been allocated to COVID-19 in the scientific journals, the researchers aiming to include many categories of countries or populations when discussing its many-sided implications, but as far as the liaison between COVID-19 vaccination and education is concerned, this aspect is rather narrow, geographically and demographically [[20], [21], [22]]. Furthermore, although the education is a key factor in public health systems, this was not broadly introduced in the COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, which led to impediments in drawing up policies to dynamize the vaccination process. Thus, to bring a new perspective, we assess the way in which the three levels of education (primary, secondary and tertiary) intertwine with COVID-19 vaccination in 45 LICs, 72 MICs and 53 HICs. By giving a larger spectrum to the research, specific geospatial measures can be extracted, which would allow public health officials and scientists to act closer where it is needed. The subsequent sections present these issues at length. The introduction is followed by the literature review; then, the methodological design is dispayed, accompanied by the related results of the study, and, finally, the discussion and conclusion parts come with offering several standpoints through which the detrimental effects of health crises can be mitigated.

2. Literature review

The literature on COVID-19 is extremely generous. The coronavirus and the pandemic have been approached from a multidisciplinary outlook to help specialists and the public at large to understand the various issues of this crisis. A straightforward exploration for COVID-19 vaccination in the Web of Science Core Collection shows an increase in research in all fields: whereas in 2020 there were 964 publications associated with COVID-19, in 2021 their volume grew to 8.817, and in 2022, to 15.679. Scholars often stressed the importance of information and awareness campaigns, the support of health workers, collective conscientiousness, ethical behaviors, trust in institutions, transparency, vaccination, to keep the pandemic under control [[23], [24], [25]]. Thus, according to Wake [26], the training of workers in the medical field is first needed; subsequently, community education and the compliance with the measures imposed by the authorities are paramount.

With the advent of the COVID-19 vaccines, it is appropriate to establish whether education can be seen as a driver in adopting vaccination. There are studies that draw attention to the role of education in the prevention of various diseases through vaccination. Refering to anti-tetanus vaccination among 417.473 adults in the United States, Rencken et al. [27] showed that this is the highest among those who have four or more years of university education. Other studies [28,29] highlight that educating patients generates positive links with vaccination for pneumococcal, influenza or hepatitis. Marfo et al. [30], based on the study of 1757 relevant reports from health sciences, extracted good practices that could be applied in Sub-Saharan Africa to increase human papillomavirus vaccination, among which education stands out.

Apart from how many cycles of education a person has attained, for the management of a pandemic, health education is also crucial, and in what follows, we present how this influenced COVID-19 vaccination, by referring to some analyses. Thus, in a research applied on 720 patients with chronic diseases in Zhejiang Province, in two rounds (the first round, unfolded before the medical education of these patients and, one year later, the second round, during which they benefited from health education related to Streptococcus pneumonia and influenza vaccination), Chen et al. [31] found out that learning generated an enhancement in vaccination rates against the two diseases. The greater one's health knowledge, the more profound their responsiveness for a medical problem. In this regard, Gala et al. [32], assessed the COVID-19 vaccination intention among 370 students from a University of Medicine (229 were not vaccinated against COVID-19) and it was outlined that over 80 % of those unvaccinated expressed their wish on this line for the upcoming six months. Furthermore, from another research [33], it emerged that 91.7 % of the students in a University in Japan embraced the idea of vaccination, the educational films made by the university in this direction having a positive impact [33]. Likewise, along with the approval of the COVID-19 vaccines for the young population, studies on this topic also appeared. For example, Willis [34] performed a research among young people aged between 12 and 15 years (N = 345), included in a health education program, and the results pointed out that 42 % of them did not oscillate at all to get vaccinated, 22 % hesitated a little, 21 % declared to be somewhat hesitant, and the remaining 15 % were very skeptical about COVID-19 vaccination. Even if COVID-19 vaccines have been tested and proved their efficacy as well when given to children over 5 years old, this is a subject that drew increased interest among parents. After conducting an online survey to observe the vaccination intention of 2054 Chinese parents in relation to their children, aged between 6 and 12 years, Tang et al. [35] concluded that 29.4 % of them hesitate to vaccinate their children, parents with higher education being likely to be more reserved when it comes to immunization through vaccination. This finding probably appears in the context in which it was discovered that the coronavirus does not cause serious symptoms among children and, due to the desire to make a thorough assessment on vaccines usage effects. Then, a work of Harris et al. [36] indicates that in the USA there is a noticeable gap between the COVID-19 vaccination of adults and children (in the age categories 5–11, respectively 12–17 years), with a higher absorption of the vaccines in the second age group, that of teenagers and, as a rule, under the circumstances when their parents were already vaccinated.

One of the problems that appeared once the COVID-19 vaccines were put into global circulation was the inability of some states to guarantee a framework in line with the general criteria for assigning doses, which does not induce discrimination by social condition, race or geographical location. In this sense, some studies have analyzed vulnerable minority groups. Thus, Ogueji et al. [37] examined a narrow sample of 35 Black people, aged between 21 and 58, from the USA and the UK, to see to what extent they felt the injustices in the health system, reflected in the absorption of COVID-19 vaccines; it turned out that more participants from the UK reported blockages related to historical factors, residence, uniform application of health policies or differentiated actions, compared to those from the USA [37]. Other researches identified racial disparities in relation to the acceptability of the COVID-19 vaccine. In this sense, McClaran's study [38], involving 487 White and Black Americans, shows that the availability of White Americans to get vaccinated is higher. Gaps in terms of vaccination were also registered among Black African-Americans, according to the results obtained by Ripon et al. [39], which highlight that 65 % of them were open to COVID-19 vaccination. This strengthens the role that health educators should have in this process.

There is a sizeable disproportionality vis-à-vis the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines among the world's populations, which is produced by a plurality of predictors. Thus, Chen et al. [40] studied the vaccination intention on a sample of 3195 people from China and concluded that 76.5 % of the respondents would like to be immunized with internal vaccines, and in the case of 74.9 % there are certain fears related to possible side effects. Pursuing the same goal, but conducting a research focused on 350 respondents from Vietnam, in mid-2021, Nguyen & Nguyen [41] found that the level of high mistrust in vaccines is largely due to information obtained from social media. In addition to this remark, Rahman et al. [42] suggest, at least as far as the EU-27 is concerned, the following factors that have major implications on vaccination decisions: the correctness of the information received in relation to the advance of medical research, the involvement of doctors, governance reliance, age, education level, and so forth. Then, according to the study of Liu et al. [43], carried out on 13 MICs of Europe, the administration of vaccine vials at longer intervals can lead to lower rates of COVID-19 deaths, with a need to grant priority to the population aged over 60; if reference is made to the distance of 4 weeks, by slightly extending it, more people can receive the first dose of vaccine earlier, which could ensure a reduction of the risks related to the disease, but it is also recommended to include other parameters when the optimal vaccination intervals are evaluated. Furthermore, Pronkina et al. [44] found out that, until December 2021, the lowest vaccination rates in Europe were in post-Soviet countries, most likely due to institutional factors (e.g., social capital). However, looking inside some states, even if they were not under this regime, there is a heterogeneity in their decision allied to COVID-19 vaccination (for instance, East Germany has more reduced levels of vaccination compared to the West, history framing this difference up to a certain point). Along with these considerations, it was plainly pointed out, on a fairly comprehensive scale (150 countries), that the greater the welfare, the larger the leaning towards vaccination [45]. So, the patterns of COVID-19 vaccination can appear as a result of a number of elements, and Chen [46] illustrates that the full speed vaccination prototype influences the most the COVID-19 spread and deaths. The decrease in the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths can be attributed to vaccination, income and education, as Cengiz et al. [47] revealed; specifically, they inventoried the situation of COVID-19 vaccination in the cities of Turkey and established that, both in the case of women and men who have a secondary education or who have interrupted their studies at a certain moment, there is a reluctance to vaccinate, while among those who followed university studies, there is a positive correlation with this, the per capita income leading to the registration of the same trend [47]. As a whole, analyzing case fatality rates for COVID-19, Nuhu et al. [48] reported the highest average in South America and the lowest in Oceania; the Africa sub-region has the smallest scores in terms of vaccination, Human Development Index (HDI) and preparedness for countering the pandemic.

Other investigations related to COVID-19 vaccination were carried out from manifold angles, covering various social groups [[49], [50], [51], [52]] or territories [[53], [54], [55], [56], [57]]. Therefore, in Africa, a continent with a large population, beyond a cumbersome management of vaccination campaigns, supplementary incentives are needed to consider all social categories, those related to age or place of origin [58]. Still, the trend encountered at country level in terms of COVID-19 cases or deaths most likely influences the intention to vaccinate, along with the performance of governments proven along the way [59]. As far as LICs are concerned, the issue of ensuring equity in obtaining the necessary vaccination vials has often been raised. Watson et al. [60] conclude that if, in the poor countries, the vaccination coverage rate of 20 %, established by COVAX, had been reached by the end of 2021, then around 45 % of COVID-19 deaths could have been prevented [60].

Groups in delicate situations (refugees, people living in peripheral communities, those who do not have any source of income or access to information) should be identified and supported constantly. Thus, we can draw attention to the study of Rego et al. [61], which presents the case of Kenya, a country where, according to a survey developed on a sample of 11.569 households, the refusal to be vaccinated decreased over the course of a few months (from 24 % in February 2021 to 9 % in October of the same year). Just like Kenya, Zimbabwe, a low-income country, does not have favorable conditions to deploy the entire arsenal required to completely benefit from vaccination programs; its different social problems (poor education, poverty, weak health system and so forth) have made the Zimbabwean society unwilling to absorb new discoveries in the matter of vaccines, as Muridzo et al. [62] emphasized. Therefore, individualized strategies in territories where there is an asymmetrical distribution in terms of HDI shall be put into practice to increase vaccination coverage, as it is outlined in the case of 196 provinces in Peru, which were analyzed by Al-kassab-Córdova et al. [63]; they identify a direct link between the HDI and the COVID-19 vaccination rate. However, there are also deviations from this tendency, to have a large coverage of vaccination, in the conditions of a high HDI. In this regard, the situation of Chile is described by Castillo et al. [64]; here, although there were not few COVID-19 cases and deaths and the HDI is rather modest, there was a pragmatic involvement of the academic environment and of the government, which advocated for the induction of a culture beneficial to vaccination that would bear fruit in a short period and ensure milestones for the consolidation of a long-term health governance [64]. In opposition to this “culture of vaccine acceptability”, the so-called “culture of vaccine rejectability” was also brought to light. This aspect was captured by Inayat [65], in the case of Pakistan, where the intervention of several specialists, including (medical) anthropologists, would be needed to shape vaccination.

By eliminating the indecision to vaccinate, the foundations for fading pandemic might be formed, and in this sense, Ouyang et al. [66] highlighted that a combined effort is required to increase the desire for vaccination, mainly where social networks, health knowledge and trust in the mass media are altered. Beyond the factors mentioned so far, COVID-19 vaccination can also be influenced by those referring to political orientations, conspiracy theories, religiosity [67], financial resources, health insurance, age, race, gender [68], confidence in the efficacy of vaccines [69]. An evidence in terms of education is that people who hold a higher education degree are more prone to vaccination.

Corroborating some issues presented in this section with the main purpose of the paper, in the following, we illustrate where LICs, MICs and HICs are placed concerning the liaison between education and COVID-19 vaccination, and we verify which of the education levels matter the most to ensure a successful vaccination.

3. Methodological design

3.1. Study rationale

Vaccination-related behaviors can be shaped by a range of factors, a large part of them being mentioned in the previous section. Without neutralizing the others' importance in the COVID-19 vaccination, in this study we turn our attention to education, to determine if it plays a decisive role in this process, in a global perspective. First of all, we consider that education is the basis for positive changes in a society and it is also one of the pillars of progress. This can go-between a range of facets of the economy in general and of life in particular, but given the current need to find further drivers of the COVID-19 vaccination, the goal is to underscore the degree of reciprocity of education with it. Secondly, in relation to the health crisis, education can prove to be a crucial factor in how to respond to it. The paper presents the situation in 2021, when there was a strong worldwide mobilization for the vaccination, after the extremely harsh costs of the pandemic, recorded the year before. Then, even though there was the highest international demand for COVID-19 vaccines in 2021, in the case of LICs this was quite marginally covered, poor infrastructure or its absence being a main inhibitor in their distribution. In general, obstacles in the process to deliver vaccines are mostly attributed to the quality of governance, the endowment with resources and the involvement of international bodies.

3.2. Sample size and description of variables

The spatial discrepancies regarding the COVID-19 vaccination led us to focus on identifying some predictors that could have a greater significance on it, and to see how they are mirrored at the level of different categorized countries: LICs, MICs and HICs, grouped by the World Bank after their GNI [70]. Because health and education are basic sectors of any economy, as a natural consequence, we wondered how much education matters in the COVID-19 vaccination process. Thus, as it emerged from the literature review part, the HDI [71] was rather introduced to explain how it fits with vaccination intentions [63,64]. Nevertheless, considering that, in our study, 170 states are incorporated (45 LICs, 72 MICs and 53 HICs), and that they have distinctive features, the integration of education on the three dimensions (primary, secondary and tertiary) can better separate what kind of measures and policies are required to be applied to generate a wider and impartial coverage of COVID-19 vaccines. The countries in the sample are specified in Appendix 1. The dependent variable is COVID-19 vaccination rate and the main explanatory variables are the levels of education, which are classified according to ISCED [72] as: basic, intermediate and advanced (namely primary, secondary and tertiary education). Primary education is the first phase of formal education, offering fundamental reading, writing and math skills; the secondary one prepares students either for higher education or for the labor market, and the tertiary one involves attending universities, colleges, vocational schools, covering advanced professional training. The values of educational attainment indicators fluctuate from 0 to 100 and they are calculated as a percentage of the population with a certain form of education; superior values show a higher degree of people with the respective education. The other independent variables take into account factors of a socio-economic or health nature: GDP/capita, elderly population (65+), comorbidities, COVID-19 vaccination certificates (dummy variable, with scores of 1 if the countries required COVID-19 vaccination passes and 0 otherwise), stringency index (associated with the governments’ response to COVID-19 and assessed on a scale of 0–100, where 100 means a pronounced rigor of intervention measures). COVID-19 deaths can underline the severity of the crisis in a country, while the age and the chronic diseases (comorbidities) can shape the vaccination process, as well as the GDP. In the part dedicated to the results, the determinism of these variables on COVID-19 vaccination is presented.

3.3. Data sources and statistical procedure

Statistics have been extracted from several international databases, freely available for those interested, such as (Table 1).

Table 1.

Indicators integrated in the study.

| Indicators | Data sources |

|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccination rates & COVID-19 deaths |

Worldometer [1], Our World in Data [2], WHO [73], Mathieu et al., 2021 [74] |

| Primary, secondary and tertiary education (%) | World Bank [75] |

| Stringency index (scaled between 0 and 100, with 100 meaning the highest strictness for applying government's measures to respond to COVID-19) | Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker - Hale et al., 2021 [76] |

| GDP (expressed in PPP), elderly (65+) and comorbidities | World Bank/World Developmet Indicators [77] |

With the purpose of investigating which of these indicators better interfere with COVID-19 vaccination, correlation analysis, OLS type regressions and a panel model are employed, 2021 monthly data for COVID-19 deaths, COVID-19 cases and COVID-19 vaccination being taken into account. As we have already specified, the spotlight is on this year because at that time, a special interest was shown to speed up the vaccination process and to have, overall, a large coverage across countries. The comparison of the three groups of countries in terms of the indicators selected for the analysis allows to design specific measures that lead to the mitigation of the gaps. To visualize the distribution of the main variables of the research (education and COVID-19 vaccination) and to identify possible outliers, correlation plots and boxplots are developed. To perform the empirical analysis, STATA and JASP (version 0.16) [78] programs are used.

4. Results

Considering that the keywords of our research refer to education and COVID-19 vaccination, in this section, we focus on underlinig how they interact at the level of the three groups of countries: LICs, MICs and HICs.

Presenting the results cumulatively, for the total sample, we obtain the estimates from Table 2. A vaccination rate of 49.25 has been reached, until the end of 2021. Education, on the three dimensions, has a decreasing average from primary (72.280), to secondary (46.497) and, then, to tertiary (18.377). The mean for GDP/capita was 19.427,52 USD, with a Max. of 116.935,6 USD and a Min. of 661,240 USD; for COVID-19 deaths, the mean is 1033.02, with a Max. of 6070.97 and a Min. of 3.101. The mean for the stringency index is 58.33, with a Max. of 87.96 and a Min. of 6.48.

Table 2.

Mean (M), Minimum (Min.), Maximum (Max.) and Std. Deviation (SD) for entire sample (LICs, MICs and HICs).

| COVID-19 vaccination | ED_ PRIMARY | ED_ SECONDARY |

ED_ TERTIARY | Comorbidities | GDP/capita | Elderly (65+) | COVID-19 deaths | Stringency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 49.257 | 72.2809 | 46.4973 | 18.3779 | 18.774 | 19427.52 | 8.898 | 1033.025 | 58.333 |

| Min. | 0.040 | 5.201 | 0.000 | 0.961 | 7.300 | 661.240 | 1.144 | 3.101 | 6.480 |

| Max. | 98.990 | 100.00 | 97.3997 | 60.6895 | 42.700 | 116935.6 | 27.049 | 6070.97 | 87.960 |

| SD | 27.724 | 28.8698 | 28.847 | 28.494 | 6.857 | 20071.60 | 6.291 | 1132.776 | 18.604 |

For capturing the dissimilarities between the three clusters of countries regarding COVID-19 vaccination and education, we also present below an inventory of descriptive statistics and correlation plots. Thus, Table 3 illustrates the situation in the case of LICs, MICs and HICs.

-

A).

When it comes to LICs, it can be noticed that the average value of COVID-19 vaccination is 16.540, a Min. of 0.040 being registered by Burundi and a Max. of 57.330 by Rwanda. Among the levels of education, the highest mean is found in primary education (38.823), with a Min. of 5.871 (Haiti) and a Max. of 97.972 (Kyrgyzstan), followed by secondary education (M = 16.400), with a Max. value for Kyrgyzstan (88.370) and a Min. value for Benin (1.100); then, the lowest percentages have tertiary education (M = 5.771; Max. of 22.870 for Tajikistan; Min. of 0.287 for Zambia);

-

B).

For MICs, the mean of COVID-19 vaccination is 50.746, with a Min. of 2.960 in the case of Cameroon and a Max. of 92.330 for Cuba. In terms of education, a similar trend to LICs is registered, more precisely with the highest levels for primary education and the lowest for tertiary education. This is not at all surprising because, irrespective of the category they belong to, states usually have compulsory primary education, school dropout rates being higher when it comes to secondary education; concerning tertiary education, there is the likelihood that the more developed a country is, the more the population show interest in following the university cycle. However, MICs have better values in relation to LICs for the variables integrated in the study;

-

C).

Within the HICs, the highest values are found for all the indicators of the analysis, the average of COVID-19 vaccination being 73.709, the Min. of 39.570 being associated with the Bahamas and the Max. of 98.990 with the United Arab Emirates. In HICs, tertiary education has the uppermost rates, which is explainable if we think about both to the quality of life and the opportunities that the labor markets offer to graduates of this form of education.

Table 3.

M, min., max. And SD for LICs, MICs and HICs.

| COVID-19 vaccination | ED_ PRIMARY |

ED_ SECONDARY |

ED_ TERTIARY |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| M | 16.540 | 38.823 | 16.400 | 5.771 | |

| A). LICs | Min. | 0.040 | 5.871 | 1.100 | 0.287 |

| Max. | 57.330 | 97.972 | 88.370 | 22.870 | |

| SD | 15.770 | 23.106 | 17.548 | 5.164 | |

| Valid | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | |

| M | 50.746 | 75.842 | 48.206 | 17.446 | |

| B). MICs | Min. | 2.960 | 5.201 | 9.297 | 0.199 |

| Max. | 92.330 | 100.000 | 97.400 | 60.690 | |

| SD | 21.872 | 23.132 | 23.623 | 13.378 | |

| Valid | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | |

| M | 73.709 | 95.672 | 70.019 | 30.346 | |

| C)· HICs | Min. | 39.570 | 61.796 | 24.206 | 10.813 |

| Max. | 98.990 | 100.000 | 90.941 | 51.765 | |

| SD | 11.641 | 6.349 | 16.893 | 10.891 |

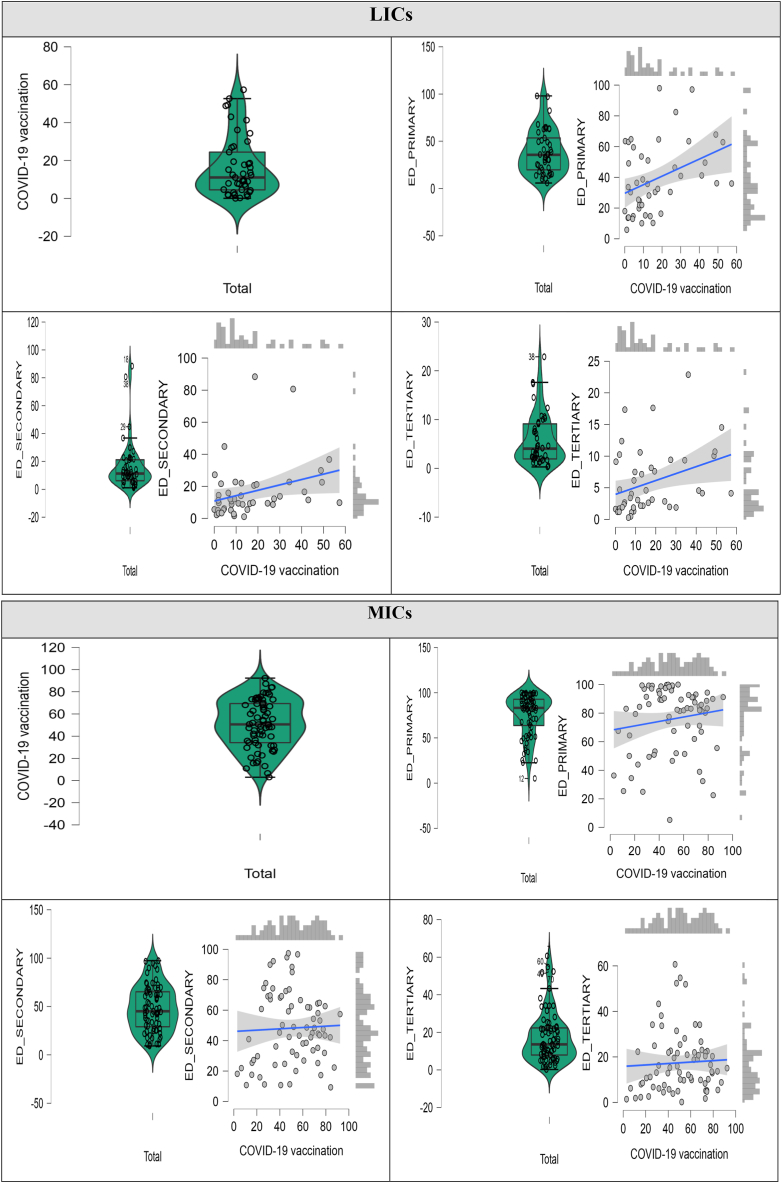

Addendum to these statistics, we display, next, correlation plots related to the groups of states under observation. However, to better monitor the differences in terms of the two key elements of the study, in Appendix 2, we represent the positioning of the first ten countries from the upper hierarchy, as well as the last ten ones from the lower hierarchy, accompanied by the corresponding boxplots and scatter plots.

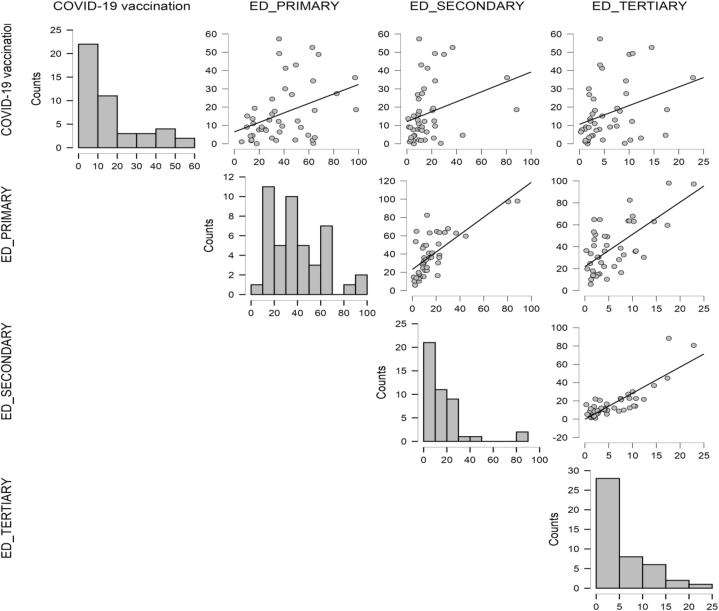

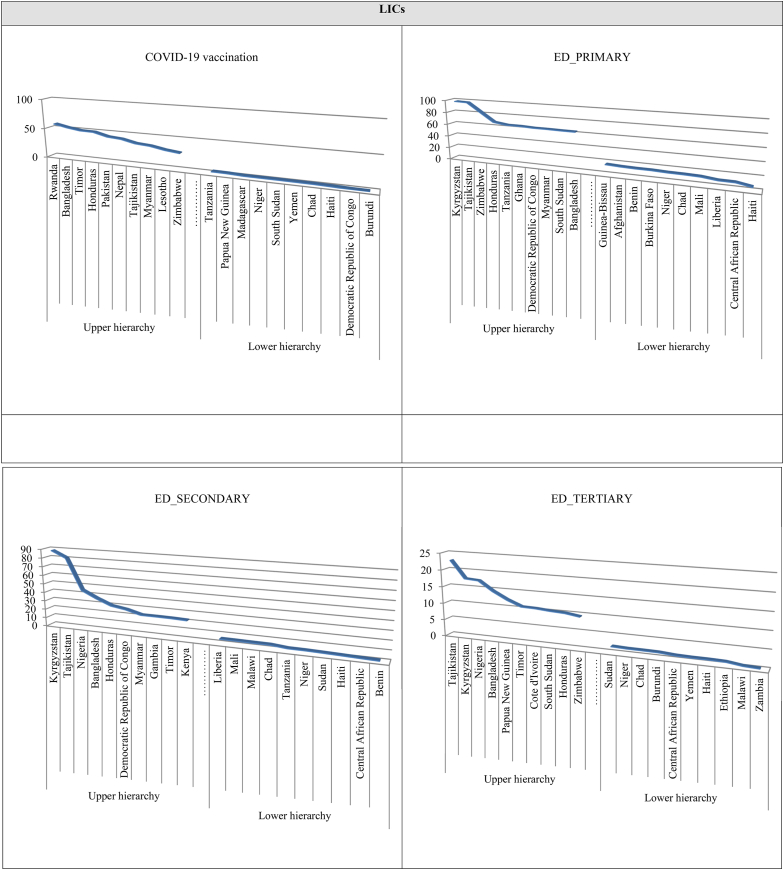

Considering the 45 LICs, the best rankings regarding COVID-19 vaccination have Rwanda (57.33), Bangladesh (52.64), Timor (49.33) and Honduras (48.85). The lower hierarchy is occupied by countries where the vaccination rate is below 2 %: Burundi (0.04), the Democratic Republic of Congo (0.24), Haiti (1.07), Chad (1.69), Yemen (1.83) and South Sudan (2 %). With reference to education, it can be observed that at the primary level, the leaders are: Kyrgyzstan (97.972), Tajikistan (97.158), Zimbabwe (82.452), Honduras (67.823), while at the opposite end stand Haiti (5.871), the Central African Republic (10.119) and Liberia (10.318). Secondary education has the biggest rates in Kyrgyzstan (88.370), followed by Tajikistan (80.669), the next ranked country, Nigeria, registering much lower values (44.858); the lower hierarchy, with scores below 3 %, is held by Benin (1.10), the Central African Republic (1.640), Haiti (2.260) and Sudan (2.80). As regards tertiary education, it has much lower values compared to the first two ISCED levels of education, namely: in the higher hierarchy are positioned Tajikistan (22.870), Kyrgyzstan (17.622), Nigeria (17.345), Bangladesh (14.530), Papua New Guinea (12.374), and in the lower hierarchy are Zambia (0.287), Malawi (0.488), Ethiopia (1.092), and Yemen (1.202). A better visualization of the trends recorded in terms of COVID-19 and education within LICs is captured in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Correlation plots for COVID-19 vaccination and education in LICs.

Hence, most LICs have vaccination rates of up to 20 %, above this percentage there is a significant narrowing of the analyzed units. Also, if we look at the education, in LICs it is found that primary one is more dispersed, its fluctuation margins being wider, compared to higher education, where only a part of the population follows it. For the secondary education, the so-called “outliers” can be distinguished (Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, both with rates above 80 %), most states concentrating up to the 20 % threshold.

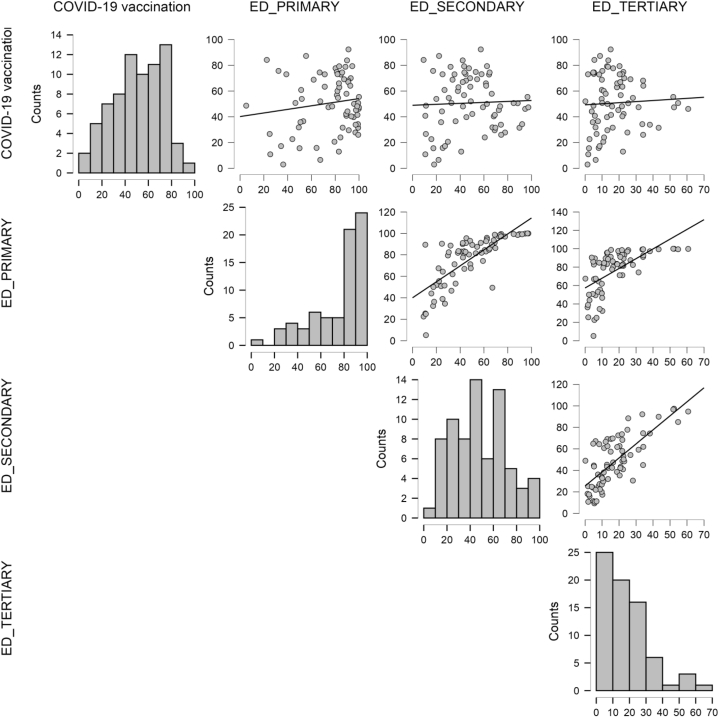

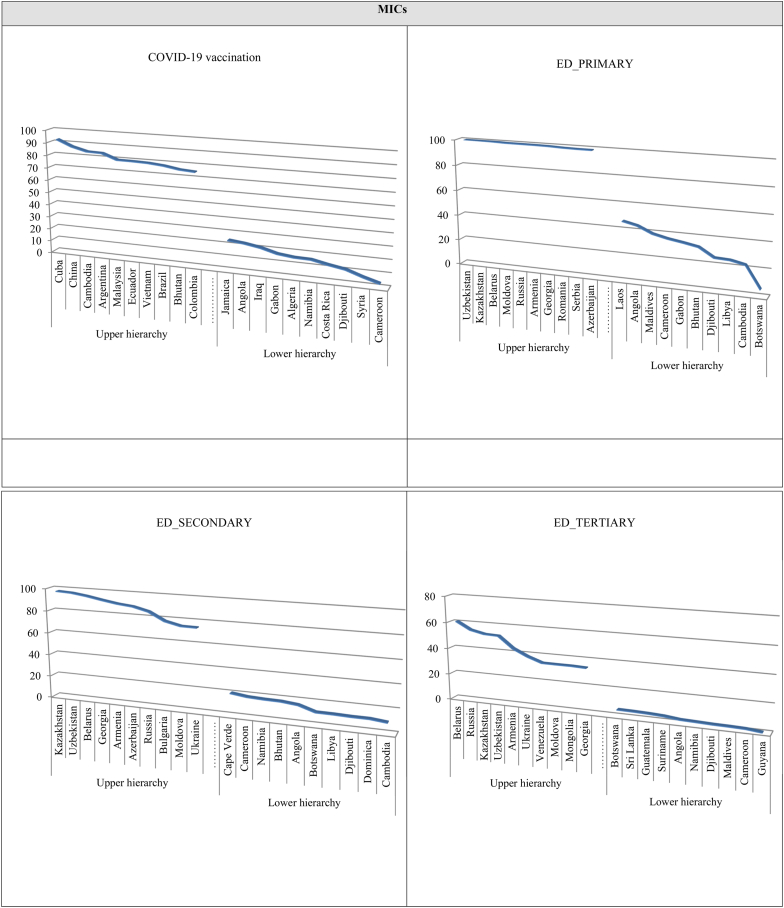

Moving on to the second group of countries in our analysis, MICs, they are differentiated in the direction of COVID-19 vaccination as follows: in the upper hierarchy is Cuba (92.33), China (87.24), Cambodia (84.16), Argentina (83.79), Malaysia (79.33), Ecuador (79.20), and in the lower hierarchy we find Cameroon (2.96), Syria (6.54), Djibouti (10.87), Costa Rica (12.99). Dividing education on the three levels, we get: the first ten MICs, out of the 72 under examination, have percentages of over 98 % when it comes to primary education (Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Moldova, Russia, Armenia, Georgia, Romania, Serbia, Azerbaijan), contrasting strongly with the states in the lower hierarchy, which have scores below 25 % (Libya: 24.90, Cambodia: 22.51), and, suddenly, the next value drops to 5.20 (Botswana); leaders in secondary education are Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Belarus and Georgia, with values over 90 %, and in the opposite, with scores around 10 %, are Djibouti, Dominica and Cambodia; in tertiary education, Belarus (60.689), Russia (54.755), Kazakhstan (52.382) and Uzbekistan (51.932) stand out, with percentages over 50.

We also present the correlation plots for MICs (Fig. 2), in which it is clear that most states exceed 40 % in terms of COVID-19 vaccination and that, although, for the reasons specified previously, there are fewer people in a country that follows tertiary education compared to primary education, there is a tendency to adjust the balance towards vaccination as education improves.

Fig. 2.

Correlation plots for COVID-19 vaccination and education in MICs.

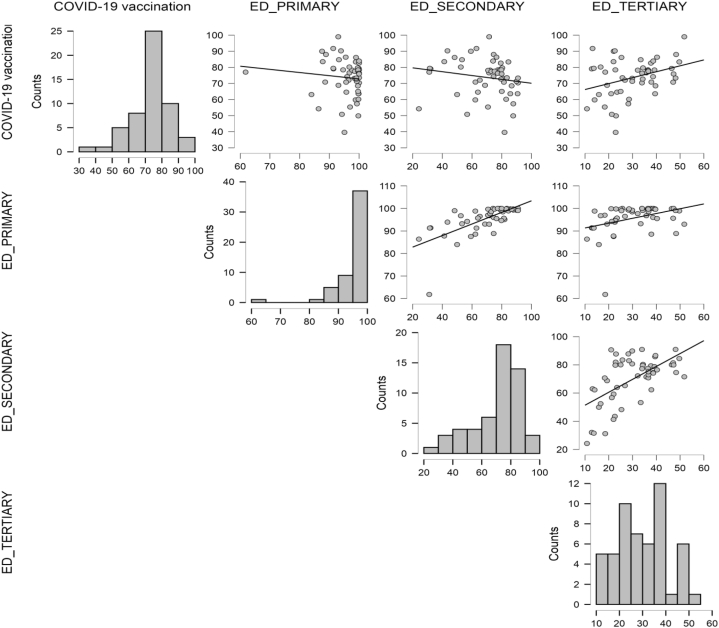

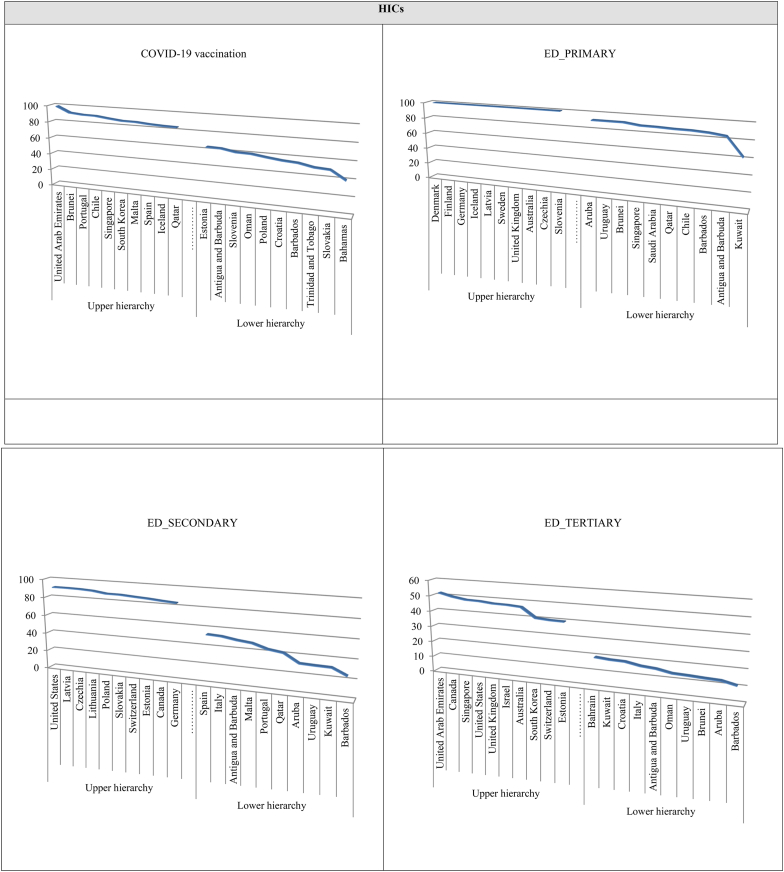

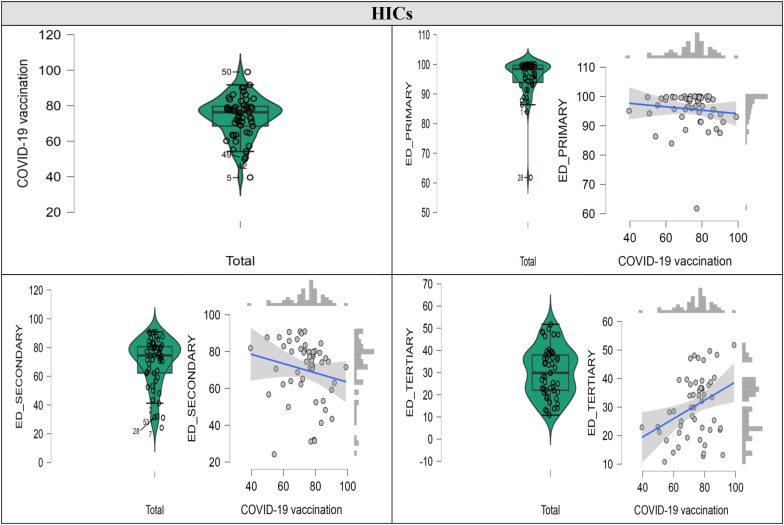

With reference to HICs, it is noted that the first five positions in the upper hierarchy are occupied by the United Arab Emirates, Brunei, Portugal, Chile and Singapore, and in the lower hierarchy, with values over 39 %, are the Bahamas, Slovakia, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados and Croatia. Primary education is very consolidated, with percentages of 100 %, in Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Latvia, Sweden and the United Kingdom, and in the lower hierarchy we find Kuwait, Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Chile, Qatar, Saudi Arabia. Secondary education has the highest levels (over 90 %) in the United States, Latvia and Czechia and the lowest ones in Barbados (24.205), Kuwait (31.196) and Uruguay (31.510). Regarding tertiary education, values of over 45 % are registered in Australia (46.452), Israel (47.073), the United Kingdom (47.243), the United States (48.089), Singapore (48.317), Canada (49.667) and the United Arab Emirates (51.765), these countries being placed in the upper hierarchy; on the other side, there are Barbados (10.813), Aruba (12.824) and Brunei (13.170).

Exploring the correlation plots in Fig. 3, one can discern that even if the lowest percentage regarding education is recorded in the tertiary sector, there is a propensity that the more educated people are, the more they are aware of the usefulness of vaccination, filtering the credible information about it and its significance for health. Therefore, it is not by chance that the upward trend of tertiary education can be distinguished in relation to the COVID-19 vaccination.

Fig. 3.

Correlation plots for COVID-19 vaccination and education in HICs.

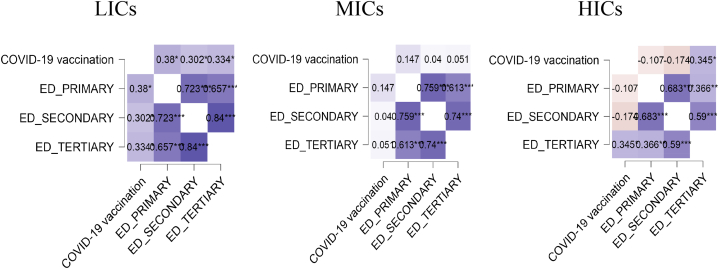

A systematically illustration of the Pearson's coefficients pertaining to COVID-19 and the three levels of education in LICs, MICs and HICs is rendered in Fig. 4, where more intense blue color means a stronger linkage between variables. As we stated before, in the case of HICs, a greater inclination towards vaccination is obvious as the level of education increases. In LICs, the population mainly has primary or secondary education and, as such, those who are vaccinated against COVID-19 belong largely to these categories; it should also be mentioned that in all groups of countries, although tertiary education is attended by the fewest people, its relationship with COVID-19 vaccination is a noticeable one.

Fig. 4.

Pearson's r heatmap for LICs, MICs and HICs.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The variables included in the analysis were subjected to OLS regression and the results are outlined in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6. The three components of education (primary, secondary and tertiary) are presented separately. Thus, Table 4 highlights the regression estimates and it is observed that they are positive for the considered indicators; in the case of COVID-19 vaccination, their values increased constantly throughout the year 2021; in relation to primary educational attainment, the coefficients lead to a slight improvement in the months of March, April and May, after which they decrease, but remain positive. There was probably a higher concern for vaccination as soon as the countries came into possession of the vials necessary to immunize the population, intense actions in this regard manifesting, particularly, in the first part of 2021.

Table 4.

Primary education & COVID-19 vaccination.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccination (t-1) | 0.145a (.040) | 0.456a (.106) | 0.345a (.106) | 0.576a (.056) | 0.680a (.027) | 0.809a (.023) | 0.897a (.029) | 0.935a (.024) | 0.952a (.016) | 0.952a (.019) | 0.974a (.019) | 0.969a (.012) |

| ED_PRIMARY | 0.143a (.265) | 0.206a (.356) | 0.207b (.356) | 0.272a (.223) | 0.337a (.096) | 0.189a (.063) | 0.112b (.067) | 0.150a (.052) | 0.139c (.035) | 0.108c (.040) | 0.134c (.039) | 0.123c (.025) |

| Comorbidities | 0.292a (.335) | 0.118c (.335) | 0.185b (.450) | 0.175c (.271) | 0.208c (.117) | 0.174c (.080) | 0.190c (.090) | 0.188c (.071) | 0.183b (.047) | 0.242c (.046) | 0.222a (.054) | 0.196a (.035) |

| Certificates | 0.210b (.129) | 0.307a (.129) | 0.370b (.175) | 0.312a (.110) | 0.321a (.046) | 0.305a (.032) | 0.323a (.036) | 0.318c (.028) | 0.228c (.019) | 0.219c (.022) | 0.238b (.021) | 0.222c (.012) |

| GDP/capita | 0.338c (.157) | 0.327c (.157) | 0.359c (.011) | 0.287c (.131) | 0.318a (.057) | 0.276b (.041) | 0.315c (.046) | 0.257c (.036) | 0.238b (.022) | 0.266a (.027) | 0.275a (.027) | 0.294a (.014) |

| Elderly (65+) | 0.124b (.180) | 0.061a (.180) | 0.135a (.243) | 0.074a (.147) | 0.143c (.063) | 0.121a (.043) | 0.062c (.048) | 0.124c (.038) | 0.116c (.025) | 0.122c (.029) | 0.086b (.029) | 0.091b (.017) |

| COVID-19 deaths (t-1) | 0.158a (.055) | 0.184a (.055) | 0.176a (.075) | 0.127a (.050) | 0.071a (.022) | 0.111c (.015) | 0.134b (.019) | 0.129a (.015) | 0.112c (.010) | 0.032b (.013) | 0.114c (.013) | 0.116a (.019) |

| Stringency (t-1) | 0.058a (.242) | 0.209c (.242) | 0.042b (.326) | 0.048c (.215) | 0.069b (.095) | 0.102c (.064) | 0.038b (.073) | 0.136c (.055) | 0.096c (.037) | 0.092c (.033) | 0.078a (.041) | 0.028a (.012) |

| Constant | −1.20 (.786) | −1.54 (.768) | −1.67 (.405) | −2.71 (.654) | −0.89 (.299) | −1.47 (.255) | −1.36 (.878) | −1.11 (.952) | −1.15 (.202) | −1.28 (.049) | −1.47 (.412) | −1.13 (.142) |

| F-statistic | 4.322 | 6.8324 | 22.725 | 65.464 | 67.557 | 68.953 | 67.540 | 68.920 | 69.045 | 69.085 | 69.051 | 69.399 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.147 | 0.234 | 0.519 | 0.763 | 0.794 | 0.797 | 0.796 | 0.797 | 0.798 | 0.798 | 0.797 | 0.798 |

| Range of VIF value | 1.053 2.806 |

1.138 2.796 |

1.205 2.721 |

1.485 2.998 |

1.547 3.019 |

1.535 3.437 |

1.588 2.803 |

1.677 2.720 |

1.736 3.851 |

1.700 3.684 |

1.632 3.265 |

1.595 2.803 |

a, b, c are associated with 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance level.

Table 5.

Secondary education & COVID-19 vaccination.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccination (−1) | 0.146a (.040) | 0.456a (.107) | 0.343a (.059) | 0.570a (.057) | 0.674a (.027) | 0.809a (.023) | 0.899a (.029) | 0.939a (.024) | 0.951a (.016) | 0.957a (.019) | 0.971a (.019) | 0.970a (.012) |

| ED_SECONDARY | 0.343c (.056) | 0.420b (.076) | 0.411b (.061) | 0.395b (.050) | 0.413c (.033) | 0.403c (.038) | 0.409b (.044) | 0.407b (.035) | 0.424b (.023) | 0.418b (.027) | 0.405c (.025) | 0.431b (.018) |

| Comorbidities | 0.115c (.169) | 0.104c (.229) | 0.059c (.179) | 0.177c (.141) | 0.198c (.065) | 0.160c (.047) | 0.117c (.044) | 0.217c (.077) | 0.186c (.070) | 0.248c (.037) | 0.221c (.069) | 0.206c (.052) |

| Certificates | 0.211a (.337) | 0.325c (.454) | 0.367b (.355) | 0.342c (.274) | 0.364c (.120) | 0.314c (.048) | 0.317c (.060) | 0.326c (.036) | 0.326c (.018) | 0.222c (.030) | 0.235c (.015) | 0.222c (.011) |

| GDP/capita | 0.364c (.157) | 0.399c (.213) | 0.295 (.165) | 0.320c (.131) | 0.283a (.065) | 0.347a (.042) | 0.328c (.051) | 0.245 (.111) | 0.237 (.112) | 0.217 (.054) | 0.214 (.059) | 0.205 (.074) |

| Elderly (65+) | 0.144c (.128) | 0.074c (.174) | 0.259c (.138) | 0.084c (.110) | 0.125c (.058) | 0.134c (.039) | 0.073c (.013) | 0.120 (.052) | 0.115c (.037) | 0.089 (.064) | 0.145 (.089) | 0.133 (.062) |

| COVID-19 deaths (t-1) | 0.062c (.242) | 0.086c (.328) | 0.081b (.257) | 0.127c (.215) | 0.069a (.097) | 0.071c (.066) | 0.133c (.081) | 0.129c (.067) | 0.111c (.028) | 0.154 (.067) | 0.115 (.254) | 0.115 (.075) |

| Stringency (t-1) | 0.075c (.181) | 0.026c (.245) | 0.043c (.192) | 0.054c (.149) | 0.042 (.066) | 0.118 (.075) | 0.034c (.063) | 0.130c (.022) | 0.098b (.037) | 0.089c (.038) | 0.077 (.065) | 0.032c (.022) |

| Constant | −0.42 (.801) | −0.87 (.419) | −1.85 (.289) | −2.25 (.138) | −1.07 (.312) | −0.42 (.256) | −1.15 (.314) | −1.14 (.449) | −1.19 (.108) | −0.23 (.099) | −0.38 (.715) | −1.08 (.318) |

| F-statistic | 4.387 | 6.745 | 22.828 | 64.047 | 65.798 | 64.738 | 65.266 | 67.469 | 68.125 | 68.748 | 68.154 | 68.363 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.150 | 0.232 | 0.520 | 0.759 | 0.767 | 0.759 | 0.762 | 0.773 | 0.787 | 0.789 | 0.777 | 0.789 |

| Range of VIF value | 1.054 3.095 |

1.140 3.109 |

1.201 3.063 |

1.459 3.015 |

1.533 3.032 |

1.524 3.437 |

1.583 4.046 |

1.680 3.055 |

1.735 3.792 |

1.701 3.653 |

1.637 3.205 |

1.602 3.012 |

a, b, c are associated with 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance level.

Table 6.

Tertiary education & COVID-19 vaccination.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccination (−1) | 0.144a (.040) | 0.464a (.107) | 0.347a (.059) | 0.558a (.058) | 0.667a (.027) | 0.811a (.023) | 0.902a (.029) | 0.907a (.090) | 0.951a (.016) | 0.952a (.019) | 0.970a (.019) | 0.975a (.012) |

| ED_TERTIARY | 0.631c (.055) | 0.713c (.075) | 0.591c (.060) | 0.653b (.051) | 0.636c (.022) | 0.569c (.019) | 0.545c (.169) | 0.599c (.078) | 0.619c (.026) | 0.609c (.029) | 0.634c (.022) | 0.622b (.021) |

| Comorbidities | 0.179c (.133) | 0.168b (.182) | 0.209b (.129) | 0.276b (.102) | 0.259c (.044) | 0.236c (.057) | 0.194c (.037) | 0.140c (.058) | 0.178b (.054) | 0.238c (.049) | 0.221c (.042) | 0.227c (.038) |

| Certificates | 0.227c (.335) | 0.319c (.450) | 0.363c (.352) | 0.325c (.280) | 0.345c (.121) | 0.309c (.035) | 0.306b (.036) | 0.135c (.017) | 0.127c (.014) | 0.122c (.036) | 0.135c (.011) | 0.128b (.014) |

| GDP/capita | 0.274c (.153) | 0.317b (.207) | 0.285b (.156) | 0.490b (.126) | 0.241b (.057) | 0.126b (.041) | 0.223b (.045) | 0.291b (.021) | 0.370c (.019) | 0.138 (.062) | 0.186 (.049) | 0.367 (.032) |

| Elderly (65+) | 0.286c (.129) | 0.193c (.175) | 0.252c (.139) | 0.194c (.113) | 0.096c (.048) | 0.098c (.022) | 0.302c (.021) | 0.117c (.039) | 0.158c (.032) | 0.206c (.049) | 0.057 (.079) | 0.065 (.089) |

| COVID-19 deaths | 0.154c (.243) | 0.074c (.329) | 0.077c (.257) | 0.106c (.220) | 0.063c (.098) | 0.104c (.055) | 0.039c (.042) | 0.160c (.089) | 0.144c (.081) | 0.122c (.063) | 0.115c (.025) | 0.118c (.030) |

| Stringency | 0.097c (.179) | 0.219c (0.242) | 0.043b (.189) | 0.058b (.149) | 0.142c (.066) | 0.109b (.065) | 0.072c (.073) | 0.078c (.018) | 0.105c (.037) | 0.091c (.037) | 0.072c (.023) | 0.033c (.021) |

| Constant | −1.17 (.826) | −1.82 (.447) | −1.81 (.299) | −2.71 (.185) | −0.99 (.213) | −1.37 (.889) | −1.12 (.622) | −0.87 (.195) | −1.19 (.168) | −1.27 (.628) | −1.39 (.576) | −1.09 (.297) |

| F-statistic | 4.285 | 6.706 | 22.838 | 60.143 | 61.756 | 61.240 | 69.862 | 75.636 | 76.694 | 78.956 | 78.144 | 78.215 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.146 | 0.230 | 0.520 | 0.747 | 0.743 | 0.741 | 0.761 | 0.788 | 0.798 | 0.790 | 0.797 | 0.799 |

| Range of VIF value | 1.0570 2.5554 |

1.138 2.603 |

1.193 3.868 |

1.461 3.925 |

1.541 2.605 |

1.530 3.441 |

1.587 4.024 |

1.529 3.718 |

1.742 3.765 |

1.706 3.629 |

1.641 3.212 |

1.607 2.779 |

a, b, c are associated with 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance level.

Countries with small vaccination rates had also lower education levels. In general, primary education explains between 0.11 and 0.33 of the vaccination percentage globally. A possible reason of these relationships is the fact that less educated people had a lower awareness of the beneficial effects of the COVID-19 vaccines and against this backdrop, the hesitation and refusal to be vaccinated can amplify. When poor education is combined with reduced income, this can render a narrower aperture to the vaccine. In addition, some people are likely to not believe in the clinical trials carried out for the production of vaccines. Subsequently, the results for secondary educational attainment are emphasized in Table 5.

People with secondary education, at least high school, have a higher probability of getting vaccinated against COVID-19 than those with a lower level of education. An average education degree was repeatedly associated with vaccination acceptance, the effect of this type of education being ample (0.34–0.43 for primary education versus 0.11–0.33 for primary education). Those with secondary education have more knowledge about life and the impact of medicine, and they are more concerned about the consequences of the coronavirus crisis for themselves and their families. This is why their confidence in the COVID-19 vaccines might be higher, in relation to those who have only primary education.

In terms of tertiary education, the values obtained are encapsulated in Table 6 and they show its weight on COVID-19 vaccination. Increased compliance with vaccination schedules among the better educated population was felt throughout the months of 2021. Thus, higher education can be considered a predictor for a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccines. The citizens with higher education may seek more data before deciding to vaccinate themselves and their children, and they may also be more trustful in medicine, knowing better how to differentiate credible sources of information from altered ones.

The coefficients accentuate that education is linked to COVID-19 vaccination rate, a stronger interconditionality of it being established with the higher levels of education.

Ultimately, the estimates of the panel regression model are presented in Table 7 and these should be noted: for primary educational attainment, the coefficient for all sample is 0.265 (p < .05); the same trend is observed for LICs (0.066), MICs (0.166) and HICs (0.435); when it comes to secondary education, the coefficients are also positive (0.414 for all panels, 0.226 for LICs, 0.444 for MICs and 0.603 for HICs), they being higher than those obtained for primary education. This demonstrates that with the expansion of education, the predilection towards vaccination could improve. For the third indicator, tertiary education, the values are illustrative: the entire sample (0.672), LICs (0.299), MICs (0.697) and HICs (0.756), all capturing the special meaning of it for the countries around the world.

Table 7.

Primary, secondary and tertiary education & COVID-19 vaccination in LICs, MICs and HICs (panel model).

| LICs | MICs | HICs | All | LICs | MICs | HICs | All | LICs | MICs | HICs | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccination (−1) | 0.803a (.029) | 0.830a (.018) | 0.714a (.021) | 0.807a (.016) | 0.805a (.029) | 0.829a (.018) | 0.716a (.020) | 0.801a (.016) | 0.793a (.029) | 0.830a (.018) | 0.717a (.020) | 0.802a (.018) |

| ED_PRIMARY | 0.066c (.066) | 0.166c (.080) | 0.435b (.100) | 0.265c (.061) | ||||||||

| ED_SECONDARY | 0.226c (.052) | 0.444c (.072) | 0.603b (.116) | 0.414c (.047) | ||||||||

| ED_TERTIARY | 0.299c (.045) | 0.697b (.039) | 0.756c (.138) | 0.672b (.039) | ||||||||

| Comorbidities | 0.132c (.187) | 0.057c (.112) | 0.765b (.138) | 0.246b (.089) | 0.015c (.185) | 0.252c (.112) | 0.829b (.136) | 0.243c (.089) | 0.098b (.186) | 0.057b (.112) | 0.840b (.137) | 0.263c (.089) |

| Certificates | 0.104c (.046) | 0.101c (.042) | 0.975a (.235) | 0.371c (.036) | 0.097c (.049) | 0.102c (.042) | 1.065a (.231) | 0.374c (.042) | 0.013c (.047) | 0.214c (.042) | 0.870a (.234) | 0.364b (.036) |

| GDP/capita | 0.021b (.070) | 0.264b (.077) | 0.697a (.120) | 0.327a (.040) | 0.024c (.075) | 0.067c (.077) | 0.746a (.123) | 0.335a (.042) | 0.006c (.070) | 0.164b (.077) | 0.721a (.118) | 0.311a (.041) |

| Elderly (65+) | 0.008b (.182) | 0.025b (.085) | 0.409a (.068) | 0.198c (.060) | 0.023c (.180) | 0.103c (.089) | 0.496a (.072) | 0.189c (.049) | 0.043c (.182) | 0.124c (.083) | 0.485c (.074) | 0.194c (.037) |

| COVID-19 deaths(t-1) | 0.071a (.035) | 0.138c (.047) | 0.171a (.031) | 0.132a (.014) | 0.170a (.035) | 0.041c (.035) | 0.165a (.031) | 0.124a (.014) | 0.185a (.036) | 0.038c (.019) | 0.163a (.031) | 0.123a (.014) |

| Stringency (t-1) | 0.034a (.089) | 0.023a (.078) | 0.076c (.143) | 0.072a (.062) | 0.033b (.090) | 0.128a (.078) | 0.161c (.141) | 0.071a (.062) | 0.047a (.088) | 0.120b (.079) | 0.141b (.139) | 0.081a (.062) |

| Constant | −0.201 (.572) | −1.191 (.590) | −2.955 (.178) | −1.530 (.239) | −0.115 (.745) | −0.160 (.632) | −2.822 (.682) | −1.471 (.113) | −0.120 (.726) | −0.179 (.590) | −2.769 (.182) | −1.429 (.458) |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.721 | 0.740 | 0.740 | 0.569 | 0.720 | 0.741 | 0.737 | 0.568 | 0.723 | 0.740 | 0.737 | 0.569 |

| Countries | 45 | 72 | 53 | 170 | 45 | 72 | 53 | 170 | 45 | 72 | 53 | 170 |

| N | 540 | 864 | 636 | 2040 | 540 | 864 | 636 | 2040 | 540 | 864 | 636 | 2040 |

| Breusch Pagan LM test | 86.82 (.000) | 65.308 (.000) | 47.324 (.000) | 43.56 (.000) | 85.856 (.000) | 82.039 (.000) | 59.804 (.000) | 45.53 (.000) | 88.599 (.000) | 64.931 (.000) | 58.124 (.000) | 44.70 (.000) |

a, b, c are associated with 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance level.

The presented results underscore that the dynamics of COVID-19 vaccination process are influenced by various factors, education being one of them. However, it is expected that the sample size of each country group would shape the vaccination coefficients (e.g., if most countries are part of the MICs, this may cause larger oscillations regarding the vaccination process). Conversely, the problems regarding the costs of the vaccine, special storage conditions, the shortcomings in human capital, the medical infrastructure, economic issues, and so forth, created gaps between countries and group of countries, which lead to strong fluctuations in terms of vaccination, even though by mid-2021, the COVID-19 vaccines were distributed in such a way as to cover as many territories as possible on different continents.

5. Discussions

Irrespective of the range of diseases for which they are administered, vaccines can give the grounds for an effective management of the health systems, especially in the case of pandemics. Thus, taking into account the major role that vaccination plays globally, the current research evaluated the impact of education on the COVID-19 vaccination among 45 LICs, 72 MICs and 53 HICs worldwide. The results underlined that the vaccination rate of the population is greater in HICs, followed by MICs and LICs, and the propensity to have an upward trend of vaccination with the increase in the level of education was highlighted. These findings are not necessarily unexpected, since education is associated with the knowledge process which, intrinsically, leads to a higher degree of awareness in terms of pertinent evaluation, based on scientific arguments, of the risks arising from contracting a virus of such magnitude. Instead, due to lack of data, interest and misinformation, a rather low vaccination rate can be reached. Therefore, education should prevail and, in addition, measures should be taken to strengthen trust in the institutions and organizations that develop and manage the implementation of healthcare strategies [79]. Besides the people included in a form of education, beneficiaries of medical information could also be the elderly, who may not have access to the novelties in the field, remarkably in the nations where digitalization is not fully integrated. Thus, a regular dialogue with doctors is imperative in such contexts. Moreover, the states where citizens have a lower level of education should be the target of future efforts and educational interventions related to vaccination, this impacting the adults, but also their responsiveness when it comes to the vaccination of their children. Preferably, more resources should be given by governments for prevention methods of various diseases among the vulnerable groups.

Due to financial considerations, there was a spatial heterogeneity, which was more pronounced between LICs and HICs. For these reasons, additional legislation was needed so that it could provide the access to vaccination of the groups at higher risk [80]. Then, the educational campaigns are indicated in order to insure that individuals have the capacity to understand medical information [52]. People with higher education accept easier to receive vaccines, and this due to the medical knowledge they possess, the wider access to relevant information sources, and the full awareness of their importance for health.

Education influences vaccination behaviors, our study emphasizing that people with superior education have more chances to consider vaccination in comparison with those that had low-grade education; this means that it is indispensable to elaborate educational programs that could enhance the consciousness regarding vaccination, in general. People with poor education might be more inclined to deny science but, during global crises, it seems that there is nothing more valuable than supporting the scientific community, at all levels, to suitably identify solutions to overcome them. Thus, where there is a strong trust in science, there could also be a high level of education, which is expected to be positively linked to the vaccination rate. It can also be stated that the strategies to broadcast the information and the raise of the level of accepting the vaccination should start both from the concerns about COVID-19 and the sensitive aspects pertaining to the beliefs of the people. Building trust takes time, but this may lead to reduced vaccine hesitancy in different contexts. Moreover, the vaccination campaigns on a larger scale call for a particular attention to existing perceptions related to the needs of communities. The leaders should also play a weighty and active role. Supplementary, they should find new trustful information locally and share it in a manner that can assure that vaccination is safe, and they should also adapt their strategies to spatial peculiarities.

Once the pandemic started, we have been concerned with finding out the consequences of certain components (e.g., globalization, governance) on COVID-19 vaccination [81,82], and this time we focused on education, thus, expanding the analysis framework. Even though the COVID-19 pandemic seems to be over, the topic related to vaccination still arouses interest, considering that humanity will face various challenges over time, including sanitary ones, and the lessons from the past and present can be useful in the management of upcoming crises. One of these lessons aims at a more pronounced scientific leaning towards the study of vulnerable groups (people from war zones, refugees, homeless people and so forth) who, in the context of crises, find themselves even more helpless and at a risk for their lives. In other researches, we will try to cover the issues faced by these groups during crises, whatever their nature.

6. Conclusions

The diversity of the countries’ features, together with those related to human behaviors, lead to a mixture of spatial prototypes when it comes to COVID-19 vaccination. Thus, there are states with a large population, but where the education level is low and which mostly also have a low socio-economic status, just as there can be countries with solid educational foundations, despite a wide range of problems. However, the lack of resources cannot justify the outright refusal of a vaccine that proved to be effective, especially if it is free of costs. In vulnerable communities, the vaccination campaigns need to be stronger and bolder, in order to conduct to informed decisions. Equally, the negative reactions cannot be hidden or negated as they are part of the process of vaccination and, therefore, they imply that the people should be educated both about the disease that the vaccination prevents and the complications that may occur. In line with these, there is a need for policies that can overtake the structural barriers of the health systems away from the immunization and to find solutions to improve the vaccination rate, mainly for the high-risk demographic groups. The communication initiatives should consider the efforts to promote the vaccines through reliable informational sources, mainly among those that manifest a lower interest in vaccination. The ensuing manifold implications are: first, they represent a valuable way to fill in the loopholes and to correct disinformation; second, through public education there should be explanations of how vaccines work, using a simple terminology.

On the whole, the lower vaccination rates were encountered in LICs and MICs. The differences in comparison with the HICs are due, among other factors, to the education of the population. Educational status influences health behaviors: on the one hand, people with lesser education may not have the appropriate know-how about COVID-19 and the role of vaccination, and on the other hand, this can also imply a lower social interaction with the specialists, which would translate into a lack of adequate information regarding the prevention of illnesses, deepening the hesitation towards vaccination. Furthermore, for those states where informational technologies are not implemented at a large scale, there is a need for supplementary efforts in order to bring the information as close as possible to the citizens and to generate, thus, a greater spatial coverage of COVID-19 vaccination. Considering that people with primary and secondary education could be more reluctant in conjunction with this process, the actions taken by the public healthcare authorities should focus mainly on these groups, to provide the right and pertinent information, that can shed light on both the benefits and risks of vaccination.

Authors’ contributions

The authors contributed equally to the elaboration of this study.

Data availability

The data can be obtained from: Worldometer; Our World in Data; World Health Organization; Mathieu et al. (2021); Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker database (Oxford University) - Hale et al. (2021); World Bank (World Development Indicators).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dan Lupu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ramona Tiganasu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

We, Dan Lupu and Ramona Tiganasu, authors of the article ‘Does education influence COVID-19 vaccination? A global view’

declare that- we have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

- ED_PRIMARY

Primary education

- ED_SECONDARY

Secondary education

- ED_TERTIARY

Tertiary education

- HDI

Human Development Index

- HICs

High-income countries

- ISCED

International Standard Classification of Education

- LICs

Low-income countries

- LMICs

Low and middle-income countries

- MICs

Middle-income countries

- WHO

World Health Organization

Contributor Information

Dan Lupu, Email: dan.lupu@uaic.ro.

Ramona Tiganasu, Email: ramona.frunza@uaic.ro.

Appendix 1. The groups of countries analyzed

| LICs | MICs | HICs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | Albania | North Macedonia | Antigua and Barbuda |

| Bangladesh | Algeria | Panama | Aruba |

| Benin | Angola | Paraguay | Australia |

| Burkina Faso | Argentina | Peru | Austria |

| Burundi | Armenia | Philippines | Bahamas |

| Central African Republic | Azerbaijan | Romania | Bahrain |

| Chad | Belarus | Russia | Barbados |

| Congo | Belize | Serbia | Belgium |

| Cote d'Ivoire | Bhutan | South Africa | Brunei |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Bolivia | Sri Lanka | Canada |

| Ethiopia | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Suriname | Chile |

| Gambia | Botswana | Syria | Croatia |

| Ghana | Brazil | Thailand | Cyprus |

| Guinea-Bissau | Bulgaria | Tunisia | Czechia |

| Haiti | Cambodia | Turkey | Denmark |

| Honduras | Cameroon | Ukraine | Estonia |

| Kenya | Cape Verde | Uzbekistan | Finland |

| Kyrgyzstan | China | Venezuela | France |

| Lesotho | Colombia | Vietnam | Germany |

| Liberia | Costa Rica | Greece | |

| Madagascar | Cuba | Hong Kong | |

| Malawi | Djibouti | Hungary | |

| Mali | Dominica | Iceland | |

| Mauritania | Dominican Republic | Ireland | |

| Mozambique | Ecuador | Israel | |

| Myanmar | Egypt | Italy | |

| Nepal | El Salvador | Japan | |

| Niger | Fiji | Kuwait | |

| Nigeria | Gabon | Latvia | |

| Pakistan | Georgia | Lithuania | |

| Papua New Guinea | Grenada | Luxembourg | |

| Rwanda | Guatemala | Malta | |

| Senegal | Guyana | Netherlands | |

| Sierra Leone | India | New Zealand | |

| Somalia | Indonesia | Norway | |

| South Sudan | Iran | Oman | |

| Sudan | Iraq | Poland | |

| Tajikistan | Jamaica | Portugal | |

| Tanzania | Jordan | Qatar | |

| Timor | Kazakhstan | Saudi Arabia | |

| Togo | Kosovo | Singapore | |

| Uganda | Laos | Slovakia | |

| Yemen | Libya | Slovenia | |

| Zambia | Malaysia | South Korea | |

| Zimbabwe | Maldives | Spain | |

| Mauritius | Sweden | ||

| Mexico | Switzerland | ||

| Moldova | Taiwan | ||

| Mongolia | Trinidad and Tobago | ||

| Montenegro | United Arab Emirates | ||

| Morocco | United Kingdom | ||

| Namibia | United States | ||

| Nicaragua | Uruguay | ||

Appendix 2. COVID-19 vaccination and education levels (primary, secondary and tertiary) in LICs, MICs and HICs

Boxplots and scatter plots for COVID-19 vaccination and education

References

- 1.Worldometers . 2022. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic.https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ available at: [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Bank . 2022. Our World in Data.https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations available at: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) OECD Health Policy Studies. OECD Publishing; Paris: 2023. Ready for the next crisis? Investing in health system resilience. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuzior A., Kashcha M., Kuzmenko O., Lyeonov S., Brożek P. Public health system economic efficiency and COVID-19 resilience: frontier DEA analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19(22) doi: 10.3390/ijerph192214727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Burden of Disease 2021 Health Financing Collaborator Network Global investments in pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: development assistance and domestic spending on health between 1990 and 2026. Lancet Global Health. 2023 Mar;11(3):e385–e413. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veldwijk J., van Exel J., de Bekker-Grob E.W., Mouter N. Public preferences for introducing a COVID-19 certificate: a discrete choice experiment in The Netherlands. Appl. Health Econ. Health Pol. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s40258-023-00808-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortiz-Millán G. COVID-19 health passes: practical and ethical issues. Bioethical Inquiry. 2023;20:125–138. doi: 10.1007/s11673-022-10227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamon Q., Govindin Ramassamy K., Rahis A.C., Guignot L., Tzourio C., Montagni I. Persistence of vaccine hesitancy and acceptance of the EU covid certificate among French students. J. Community Health. 2022;47:666–673. doi: 10.1007/s10900-022-01092-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization (Who) Immunization coverage. 2022. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage

- 10.Zhang J.J., Dong X., Liu G.H., Gao Y.D. Risk and protective factors for COVID-19 morbidity, severity, and mortality. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023;64(1):90–107. doi: 10.1007/s12016-022-08921-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kackos C.M., Surman S.L., Jones B.G., Sealy R.E., Jeevan T., Davitt C.J.H., Pustylnikov S., Darling T.L., Boon A.C.M., Hurwitz J.L., Samsa M.M., Webby R.J. mRNA vaccine mitigates SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023;11(1) doi: 10.1128/spectrum.04240-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson O.J., Barnsley G., Toor J., Hogan A.B., Winskill P., Ghani A.C. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022;22(9):1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toubasi A.A., Al-Sayegh T.N., Obaid Y.Y., Al-Harasis S.M., AlRyalat S.A.S. Efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines: a network meta-analysis. J. Evid. Base Med. 2022 Sep;15(3):245–262. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12492. Epub 2022 Aug 23. PMID: 36000160; PMCID: PMC9538745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillon M., Kergall P. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination intentions and attitudes in France. Publ. Health. 2021;198:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartscher A.K., Seitz S., Siegloch S., Slotwinski M., Wehrhöfer N. Social capital and the spread of COVID-19: insights from European countries. J. Health Econ. 2021;80 doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukusa L.A., Ndze V.N., Mbeye N.M., Wiysonge C.S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of educating parents on the benefits and schedules of childhood vaccinations in low and middle-income countries. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14(8):2058–2068. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1457931. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich J.A., Miech E.J., Bilal U., Corbin T.J. How education and racial segregation intersect in neighborhoods with persistently low COVID-19 vaccination rates in Philadelphia. BMC Publ. Health. 2022;22:1044. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonander C., Ekman M., Jakobsson N. Vaccination nudges: a study of pre-booked COVID-19 vaccinations in Sweden. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022;309 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steens A., Stefanoff P., Daae A., Vestrheim D.F., Riise Bergsaker M.A. High overall confidence in childhood vaccination in Norway, slightly lower among the unemployed and those with a lower level of education. Vaccine. 2020;38(29):4536–4541. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humer E., Jesser A., Plener P.L., Probst T., Pieh C. Education level and COVID-19 vaccination willingness in adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. 2023;32(3):537–539. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01878-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schäfer M., Stark B., Werner A.M., Mülder L.M., Heller S., Reichel J.L., Schwab L., Rigotti T., Beutel M.E., Simon P., Letzel S., Dietz P. Determinants of university students' COVID-19 vaccination intentions and behavior. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-23044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J.D., Ackerman M.S., Laspra B., Polino C., Huffaker J.S. Public attitude toward Covid-19 vaccination: the influence of education, partisanship, biological literacy, and coronavirus understanding. Faseb. J. 2022;36(7) doi: 10.1096/fj.202200730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang X., Hwang J., Su M.H., Wagner M.W., Shah D. Ideology and COVID-19 vaccination intention: perceptual mediators and communication moderators. J. Health Commun. 2022;27(6):416–426. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2022.2117438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rughiniș C., Vulpe S.N., Flaherty M.G., Vasile S. Vaccination, life expectancy, and trust: patterns of COVID-19 and measles vaccination rates around the world. Publ. Health. 2022;210:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon S., Goh H., Matchar D., Sung S.C., Lum E., Shao Wei Lam S., Guek Hong Low J., Chua T., Graves N., Ong M. Multifactorial influences underpinning a decision on COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers: a qualitative analysis. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18:5. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2085469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wake A.D. Knowledge, attitude, practice, and associated factors regarding the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), pandemic. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020;13:3817–3832. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S275689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rencken C.A., Dunsiger S., Gjelsvik A., Amanullah S. Higher education associated with better national tetanus vaccination coverage: a population-based assessment. Prev. Med. 2020;134 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altay M., Ateş İ., Altay F.A., Kaplan M., Akça Ö., Özkara A. Does education effect the rates of prophylactic vaccination in elderly diabetics? Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016;120:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redfield J.R., Wang T.W. Improving pneumococcal vaccination rates: a three-step approach. Fam. Med. 2000;32(5):338–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marfo E.A., King K.D., Adjei C.A., MacDonald S.E. Features of human papillomavirus vaccination education strategies in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Publ. Health. 2022;213:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y., Gu W., He B., Gao H., Sun P., Li Q., Chen E., Miao Z. Impact of a community-based health education intervention on awareness of influenza, pneumonia, and vaccination intention in chronic patients. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1959828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gala D., Parrill A., Patel K., Rafi I., Nader G., Zhao R., Shoaib A., Swaminath G., Jahoda J., Hassan R., Colello R., Rinker D. Factors impacting COVID-19 vaccination intention among medical students. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18:1. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2025733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakamoto M., Ishizuka R., Ozawa C., Fukuda Y. Health information and COVID-19 vaccination: beliefs and attitudes among Japanese university students. PLoS One. 2022;17(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willis D.E., Presley J., Williams M., Zaller N., McElfish P.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among youth. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(12):5013–5015. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1989923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang S., Liu X., Jia Y., Chen H., Zheng P., Fu H., Xiao Q. Education level modifies parental hesitancy about COVID-19 vaccinations for their children. Vaccine. 2023;41(2):496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris J., Mauro C., Morgan T., de Roche A., Zimet G., Rosenthal S. Factors impacting parental uptake of COVID-19 vaccination for U.S. children ages 5–17. Vaccine. 2023;41(20):3151–3155. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogueji I., Demoko Ceccaldi B., Okoloba M., Maloba M., Adejumo A., Ogunsola O. Black people narrate inequalities in healthcare systems that hinder COVID-19 vaccination: evidence from the USA and the UK. J. Afr. Am. Stud. 2022;26:297–313. doi: 10.1007/s12111-022-09591-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McClaran N., Rhodes N., Xuejing Yao S. Trust and coping beliefs contribute to racial disparities in COVID-19 vaccination intention. Health Commun. 2022;37(12):1457–1464. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2035944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ripon R.K., Motahara U., Alam A., Ishadi K.S., Sarker S. A meta-analysis of COVID-19 vaccines acceptance among Black/African American. Heliyon. 2022;8(12) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen M., Li Y., Chen J., Wen Z., Feng F., Zou H., Fu C., Chen L., Shu Y., Sun C. An online survey of the attitude and willingness of Chinese adults to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(7):2279–2288. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1853449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen D.V., Nguyen P.H. Social media and COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy: mediating role of the COVID-19 vaccine perception. Heliyon. 2022;8(9) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahman I., Austin A., Nelson N. Willingness to COVID-19 vaccination: empirical evidence from EU. Heliyon. 2023;9(5) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y., Pearson C., Sandmann F., Barnard R., Kim J.H., Flasche S., Jit M., Abbas K. Dosing interval strategies for two-dose COVID-19 vaccination in 13 middle-income countries of Europe: health impact modelling and benefit-risk analysis. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2022;17 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pronkina E., Berniell I., Fawaz Y., Laferrère A., Mira P. The COVID-19 curtain: can past communist regimes explain the vaccination divide in Europe? Soc. Sci. Med. 2023;321 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coccia M. Improving preparedness for next pandemics: Max level of COVID-19 vaccinations without social impositions to design effective health policy and avoid flawed democracies. Environ. Res. 2022;213 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y.T. Effect of vaccination patterns and vaccination rates on the spread and mortality of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy and Technology. 2023;12(1) doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2022.100699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]