Abstract

Human CD1 is a family of nonpolymorphic major histocompatibility complex class I-like molecules capable of presenting mycobacterial lipids, including lipoarabinomannan (LAM), to double-negative (DN; CD4− CD8−) as well as CD8+ T cells. Structural similarities between LAM and the capsular polysaccharides of gram-negative bacteria led us to consider the latter as candidate CD1 ligands. We derived two CD1-restricted DN T-cell populations which proliferated to Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) antigen. One T-cell population also proliferated to proteinase K-treated Hib antigen, suggesting that it recognized a nonpeptide. Our work thus expands the universe of T cell antigens to include nonpeptides distinct from mycobacterial lipids and suggests a potential role for CD1-restricted T cells in immunity to Hib.

Human CD1 is a family of nonpolymorphic major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-like molecules (CD1a to CD1d) (4, 7, 15, 18). Although CD1 is encoded outside the MHC, its association with β2-microglobulin relates it structurally to MHC class I. CD1 molecules are expressed on immature thymocytes (19) and antigen-presenting cells (APC) including cytokine-activated macrophages (13), B cells (22, 23), and dermal dendritic cells (9). Recent studies have revealed that CD1 possesses the unique function of presenting nonpeptide antigen (Ag) to T cells (3, 17, 21, 24). A prototypic Ag presented in the context of CD1 is lipoarabinomannan (LAM), a mannose polymer substituted at one end with arabinose and at the other with a phosphatidic acid containing tubulostearic and palmitic acids. De-O-acylation of LAM totally abrogated T-cell responsiveness, suggesting that the lipid moiety was required for Ag recognition (21). Since gram-negative bacteria contain lipoglycans structurally analogous to LAM (2, 11, 14, 20), we sought to isolate CD1-restricted T cells which recognize antigens from Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), a representative gram-negative bacterium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antigens.

Hib strain 10211 (ATCC, Rockville, Md.) was grown on pyridoxal-supplemented chocolate agar (Becton Dickinson Microbiological Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Bacteria were scraped from 10 agar plates, pelleted at 1,000 × g, and probe sonicated in 4 ml phosphate-buffered saline at 50% power continuously for 5 min on ice. Sonicates were ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C, and the supernatants were filter (0.2-μm pore size) sterilized. Protein concentration, as determined by Micro BCA Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) was used to standardize the Ag dose. To prepare nonpeptide Ag, Hib sonicate was treated with proteinase K (0.7 mg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) for 30 min at 60°C and then heat inactivated for 10 min at 70°C.

MAbs.

Anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) used for immunodepletion were purchased from Immunotech (Westbrook, Maine) and Becton Dickinson (San Jose, Calif.), respectively. Anti-CD1 antibodies were as follows: P3 (murine immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]) (16), OKT6 (anti-CD1a) (19), BCD1b3.1 (anti-CD1b; provided by S. A. Porcelli), 10C3 (anti-CD1c) (15), and L161 (anti-CD1c; Immunotech). F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG-phycoerythrin (PE) was obtained from Caltag (San Francisco, Calif.). All other antibodies used in flow cytometry were purchased from Becton Dickinson.

Preparation of APC.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from a healthy donor were isolated by Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) density centrifugation and incubated for 72 h at 106/ml in complete medium (CM; RPMI 1640, 100 mM sodium pyruvate, 200 mM l-glutamate, 5 U of streptomycin-penicillin per ml) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 200 U of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; Genetics Institute, Cambridge, Mass.) per ml, and 100 U of interleukin-4 (IL-4; Schering Corp., Bloomfield, N.J.) per ml. Adherent cells were removed with 5 mM EDTA–phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.3) for 10 min at 37°C, irradiated with 5,000 rads, and stored in liquid nitrogen until used. CD1a, CD1b, and CD1c expression was confirmed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry.

Cytokine-activated PBMC containing 20% monocytes (105/sample) were resuspended in Hanks balanced salt solution–1% bovine serum albumin (FACS [fluorescence-activated cell sorting] buffer); 100-μl cell suspensions were stained with 0.3 μg of unlabeled monoclonal antibodies to CD1a, CD1b, and CD1c per ml for 45 min on ice. P3 was used as an IgG1 isotype control. Cells were washed with FACS buffer and then stained with 2 μl of PE-conjugated F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG. 7-Amino actinomycin D (Calbiochem) was used as a dead cell discriminator; 5,000 to 10,000 live events per sample were analyzed with a FACStar Plus flow cytometer and Lysis II software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, Calif.). T cells were analyzed similarly except that they were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate- or PE-conjugated antibodies for 30 min.

Isolation of T-cell populations.

To prepare autologous CD1+ APC, PBMC were resuspended to 2 × 106/ml in CM supplemented with 20% FCS, GM-CSF (400 U/ml), and 200 IL-4 (U/ml). Cell suspensions were plated at 100 μl/well in a 96-well round-bottom plate for 24 h and then irradiated with 5,000 rads. Hib Ag was then added at 1 μg/ml (final protein concentration), and double-negative (DN; CD4− CD8−) T cells (see below) were added at 104 to 105 per well to give a final culture volume of 200 μl. After 72 h of culture, autologous APC and Ag were replenished. Heterologous APC and fresh Ag were again added after 72 h and every 2 weeks thereafter. Between Ag stimulations, IL-2 (10 U/ml; Schiaparelli, Columbia, Md.) was added, and cells were split every 3 to 4 days to maintain near confluency. CD4+ T-cell populations derived by coculturing nondepleted peripheral blood leukocytes with irradiated autologous PBMC in the presence of Hib Ag. T-cell subclones were isolated at limiting dilution, using 105 heterologous CD1+ APC per well.

Proliferation assays.

T cells were plated in triplicate at a concentration of 104/well in the presence of 105 heterologous, irradiated (5,000 rads) PBMC containing 20% CD1+ monocytes per well. Assays were performed in 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates in 200 μl of CM–2% pooled human serum–8% FCS. Hib Ag was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. In blocking experiments, cells were cultured in the presence of anti-CD1 MAbs at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml or 1:400 ascites fluid. Wells were pulsed with 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine during the last 4 h of a 72-h incubation period. Cells were harvested onto glass fiber filters, and tritiated thymidine incorporation was measured by scintillation counting (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, Calif.).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Autologous APC were prepared by treating blood monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4 to induce expression of CD1. Substantial surface expression of all three CD1 gene products was detected in these induced monocytes. By flow cytometry, the frequencies of CD1+ monocytes were 8.5, 6.3, and 10.6% (anti-CD1a, anti-CD1b, and anti-CD1c, respectively; 0.6% for isotype control staining). The mean fluorescence intensity units were 272, 95, and 83, respectively (11 for isotype control staining). Thus, comparable expression levels of the different CD1 isoforms is achieved by this induction method.

Healthy donor lymphocytes were depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in order to prepare a population enriched for CD1-restricted T cells. These DN T cells were cocultured with Hib Ag-pulsed CD1+ APC and then screened for both Hib Ag reactivity and CD1 restriction by a standard proliferation assay in the presence of blocking antibodies specific for CD1a, CD1b, or CD1c. Forty-six T-cell cultures were obtained from four different donors and analyzed. Most of these were unstable in passage and therefore incompletely characterized. Fifteen T-cell lines had demonstrable anti-Hib nonpeptide activity, distributed among all four donors. This observation supports the interpretation that T cells reactive with Hib nonpeptides are a common trait in independent human donors.

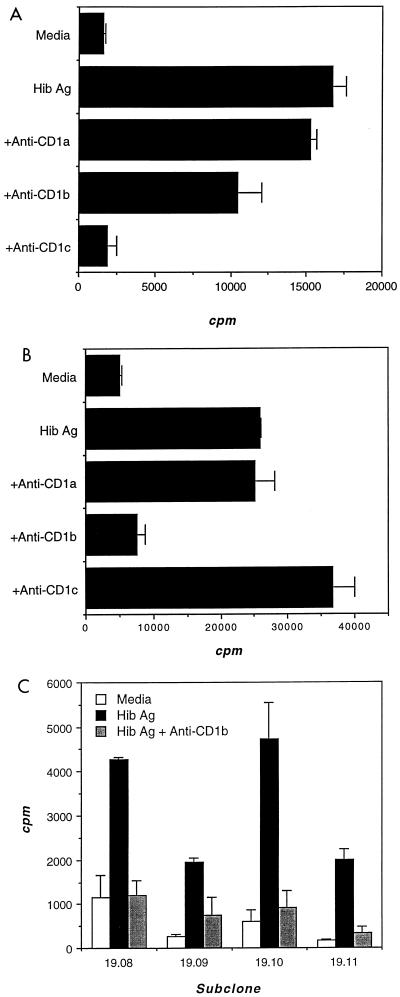

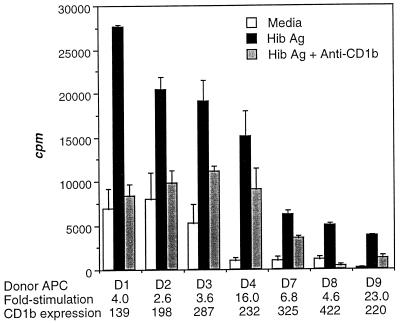

Two T-cell populations, Hib16 and Hib19, proliferated well to Hib Ag and were selected for more detailed study (Fig. 1). Ag-specific proliferation of Hib16 was blocked 98% by anti-CD1c MAb (Fig. 1A), whereas that of Hib19 was blocked 88% by anti-CD1b MAb (Fig. 2B). In addition, four Hib19 subclones proliferated to Hib Ag in a CD1b-restricted manner (Fig. 1C). CD1+ APC derived from several unrelated donors also supported Ag-specific and CD1b-restricted proliferation of Hib19, indicating further that Ag recognition was not MHC restricted (Fig. 2). Although the human CD1 molecule is strictly nonpolymorphic, we found that CD1+ APC differed in the ability to support both Ag-specific and background proliferation of Hib19. This ability was unrelated to their level of expression of CD1b (Fig. 2), which suggested either that the CD1–T-cell receptor (TCR) interaction was modulated by a polymorphic molecule or that the levels of putative costimulatory molecules differed among the APC tested (5).

FIG. 1.

Hib Ag-specific, CD1-restricted proliferation of Hib16 (A) and Hib19 (B) T-cell populations and of Hib19 T-cell clones (C). T cells were cocultured with irradiated CD1+ APC and Hib Ag in the presence of blocking antibodies specific for CD1a, CD1b, or CD1c. During the last 4 h of a 72-h incubation, cultures were pulsed with tritiated thymidine, the cellular incorporation of which was determined by scintillation counting and expressed as counts per minute.

FIG. 2.

Hib Ag-specific, CD1b-restricted proliferation of Hib19 T cells. Hib19 T cells were cocultured with irradiated CD1+ APC (isolated from seven unrelated donors [D1 to D4 and D7 to D9]) and Hib Ag in the presence of CD1b blocking antibodies. Proliferation was measured as for Fig. 1. The fold stimulation and mean fluorescence intensity of CD1 expression are indicated for each donor.

The phenotypes of Hib16 and Hib19 T-cell populations and subclones were determined by two-color flow cytometry. Both T-cell populations lacked expression of CD4. Although both T-cell populations expressed variable levels of CD8dim, they contained a large fraction which were DN. CD56 was expressed on 90 and 31% of Hib16 and Hib19 T cells, respectively. The expression of CD56, a natural killer (NK) cell marker, on both T-cell populations parallels the expression of NK1.1 on a significant fraction of mouse CD1-restricted T cells (6). Although the role of CD56 in CD1-restricted T-cell responses has not been addressed, the CD4− CD8−/dim CD56+ phenotype of Hib16 and Hib19 nevertheless indicated they were not conventional T-helper cells. Finally, Hib16 expressed predominantly (94%) TCRαβ. Whereas only 68% Hib19 expressed TCRαβ (the remainder expressed TCRγδ), four Hib19 subclones expressed exclusively TCRαβ. This finding argues that the Ag reactivity and CD1 restriction of Hib19 (Fig. 1B and C) required expression of the TCRαβ heterodimer. Thus, the phenotypes of both Hib16 and Hib19 mirrored those of other mycobacterium-specific, CD1-restricted T-cell populations (3, 17, 21, 24).

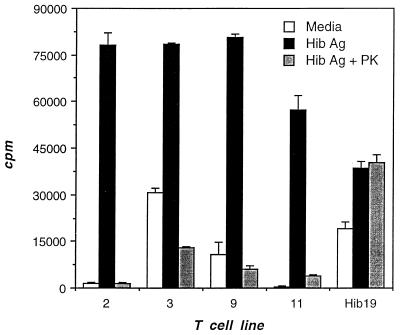

To determine whether the Ag to which Hib16 and Hib19 reacted was a nonpeptide, proteinase K-treated Hib Ag was tested in a proliferation assay. Proteinase K-treated Hib Ag was shown to be devoid of protein Ag by two criteria. First, Hib Ag proteins resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized with Coomassie blue stain disappeared after treatment with proteinase K (data not shown). Second, to ensure that small immunogenic peptides did not persist, proteinase K-treated Hib Ag was tested for the ability to stimulate several CD4+, MHC class II-restricted, Hib Ag-specific T-cell populations. All of nine CD4+ T-cell populations which proliferated specifically to Hib Ag failed to proliferate to proteinase K-treated Hib Ag (data for four representative populations are shown in Fig. 3). In contrast, proteinase K treatment did not affect the proliferative response of Hib19 to Hib Ag (Fig. 3), indicating that the Ag was a nonpeptide.

FIG. 3.

Validation that proteinase K-treated Hib Ag lacks immunogenic peptides. Hib19 was tested for the ability to respond to Hib Ag and to proteinase K (PK)-treated Hib Ag. Validation that proteinase K-treated Hib Ag lacked immunogenic peptides was achieved by using Hib Ag-specific CD4+ T-cell lines (2, 3, 9, and 11) derived from the same donor. Proliferation was measured as for Fig. 1.

Since Hib expresses neither LAM nor mycolic acids, we have speculated that either of two lipoglycan Ags, lipo-oligosaccharide (12) and the capsular polysaccharide (capPS) (1, 8) may be presented by CD1. LAM is structurally related to the capPS of several gram-negative bacteria, including Hib (2, 14), groups A to C of Neisseria meningitidis (2), and several K serotypes of Escherichia coli (11, 20). What is not generally appreciated about capPS is that they are naturally lipidated, a modification responsible for anchoring these highly charged molecules into bacterial outer membranes (2). Like LAM, capPS are substituted with a phosphatidic acid containing palmitic acid. This structural similarity between LAM and capPS led us to propose that palmitic acid anchors into the hydrophobic groove of CD1 diverse covalently attached polysaccharides for direct recognition by T cells (10). Accordingly, we hypothesized that CD1-restricted T cells play an important role in host immunity to encapsulated bacteria by virtue of their ability to recognize capPS. Although only mycobacterium-reactive CD1-restricted T cells have been identified to date, the demonstration here that CD1-restricted T cells can recognize Hib Ag suggests a role for CD1 Ag presentation in the immune response to gram-negative bacteria. Future studies designed to identify the Hib Ag and the immunological roles of these CD1-restricted T cells should provide novel insights into antibacterial immunity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AI38545 and CA 12800, the UCLA Medical Scientist Training Program, the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, and The Gustavus and Louise Pfeiffer Research Foundation.

We thank S. Stenger for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson P, Smith D H. Isolation of the capsular polysaccharide from culture supernatant of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Infect Immun. 1977;15:472–477. doi: 10.1128/iai.15.2.472-477.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakere G, Lee A L, Frasch C E. Involvement of phospholipid end groups of group C Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharides in association with isolated outer membranes and in immunoassays. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:691–695. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.691-695.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckman E M, Porcelli S A, Morita C T, Behar S M, Furlong S T, Brenner M B. Recognition of a lipid antigen by CD1-restricted alpha beta+ T cells. Nature. 1994;372:691–694. doi: 10.1038/372691a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckman E M, Brenner M B. MHC class I-like, class II-like and CD1 molecules: distinct roles in immunity. Immunol Today. 1995;16:349–352. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behar S M, Porcelli S A, Beckman E M, Brenner M B. A pathway of costimulation that prevents anergy in CD28− T cells. B7-independent costimulation of CD1-restricted T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:2007–2018. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bendelac A, Lantz O, Quimby M E, Yewdell J W, Bennink J R, Brutkiewicz R. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268:863–865. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabi F, Bradbury A. The CD1 system. Tissue Antigens. 1991;37:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1991.tb01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crisel R A, Baker R S, Dorman D E. Capsular polymer of Haemophilus influenzae, type b. Structural characterization of the capsular polymer of strain Eagan. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4926–4930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elder J T, Reynolds N J, Cooper K D, Griffiths C E, Hardas B D, Bleicher P A. CD1 gene expression in human skin. J Dermatol Sci. 1993;6:206–213. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(93)90040-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairhurst R M, Wang C X, Sieling P A, Modlin R L, Braun J. The role of CD-1 restricted T cells in antibody to T cell-independent antigens. Immunol Today. 1998;19:257–259. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotschlich E C, Fraser B A, Nishimura O, Robbins J B, Liu T Y. Lipid on capsular polysaccharides of gram-negative bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:8915–8921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inzana T J. Electrophoretic heterogeneity and interstrain variation of the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:492–499. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasinrerk W, Baumruker T, Majdic O, Knapp W, Stockinger H. CD1 molecule expression on human monocytes induced by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Immunol. 1993;150:579–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuo J S, Doelling V W, Graveline J F, McCoy D W. Evidence for the covalent attachment of phospholipid to the capsular polysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:769–773. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.769-773.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin L H, Calabi F, Lefebrve F A, Bilsland C A, Milstein C. Structure and expression of the human thymocyte antigens CD1a, CD1b, and CD1c. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9189–9193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panchamoorthy G, McLean J, Modlin R L, Morita C T, Ishikawa S, Brenner M B, Band H. A predominance of the T cell receptor Vgamma2/Vdelta2 subset in human mycobacteria-responsive T cells suggests germline gene-encoded recognition. J Immunol. 1991;147:3360–3369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porcelli S, Morita C T, Brenner M B. CD1b restricts the response of human CD4−CD8− T lymphocytes to a microbial antigen. Nature. 1992;360:593–597. doi: 10.1038/360593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porcelli S A. The CD1 family: a third lineage of antigen-presenting molecules. Adv Immunol. 1995;59:1–98. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinherz E L, Kung P C, Goldstein G, Levey R H, Schlossmann S F. Discrete stages of human intrathymic differentiation: analysis of normal thymocytes and leukemic lymphoblasts of T-cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:1588–1592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt M A, Jann K. Phospholipid substitution of capsular (K) polysaccharide antigens from Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal infections. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1982;14:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sieling P A, Chatterjee D, Porcelli S A, Prigozy T I, Mazzaccaro R J, Soriano T, Bloom B R, Brenner M B, Kronenberg M, Brennan P J, Modlin R L. CD1-restricted T cell recognition of microbial lipoglycan antigens. Science. 1995;269:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.7542404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Small T N, Knowles R W, Keever C, Kernan N A, Collins N, O’Reilly R J, Dupont B, Flomenberg N. M241 (CD1) expression on B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1987;138:2864–2868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith M E F, Thomas J A, Bodmer W F. CD1c antigens are present in normal and neoplastic B-cells. J Pathol. 1988;156:169–177. doi: 10.1002/path.1711560212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomssen H, Ivanyi J, Espitia C, Arya A, Londei M. Human CD4−CD8− alpha beta+ T-cell receptor T cells recognize different mycobacteria strains in the context of CD1b. Immunology. 1995;85:33–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]