Abstract

Eukaryal tRNA splicing endonucleases use the mature domains of pre-tRNAs as their primary recognition elements. However, they can also cleave in a mode that is independent of the mature domain, when substrates are able to form the bulge–helix–bulge structure (BHB), which is cleaved by archaeal tRNA endonucleases. We present evidence that the eukaryal enzymes cleave their substrates after forming a structure that resembles the BHB. Consequently, these enzymes can cleave substrates that lack the mature domain altogether. That raises the possibility that these enzymes could also cleave non-tRNA substrates that already have a BHB. As predicted, they can do so, both in vitro and in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Accuracy in tRNA splicing is essential for the formation of functional tRNAs, and hence for cell viability. In both Archaea and Eukarya the specificity of splicing resides in recognition of tRNA precursors by tRNA splicing endonucleases (Belfort and Weiner, 1997; Trotta and Abelson, 1999). Archaeal tRNA splicing endonucleases cleave pre-tRNAs only using an RNA structure comprised of two bulges of three nucleotides each (where cleavage occurs) separated by four base pairs. This structure, called the bulge–helix–bulge (BHB) (Figure 1A, 2) (Daniels et al., 1985; Diener and Moore, 1998), functions independently of the part of the molecules that constitutes the mature tRNA, so we refer to this type of recognition of the cleavage sites as being the mature-domain independent mode. In contrast, eukaryal tRNA splicing endonucleases require interaction with the mature tRNA domain for orientation, so we refer to that recognition as the mature-domain dependent mode (Mattoccia et al., 1988; Reyes and Abelson, 1988).

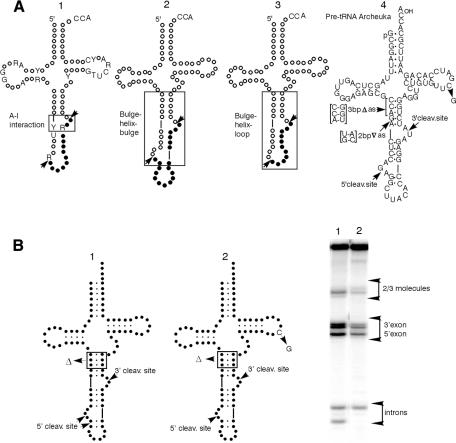

Fig. 1. (A) The A-I interaction. A conserved purine residue in the intron three nucleotides from the 3′ cleavage site (molecule 1, R in box) must pair with a pyrimidine in the anticodon loop 6 nucleotides upstream of the 5′ cleavage site (molecule 1, Y in box) to form the A-I (for anticodon–intron) interaction (Baldi et al., 1992). BHB (molecule 2). Two bulges of three nucleotides each (where cleavage occurs) rigidly separated by four base pairs (Daniels et al., 1985; Diener and Moore, 1998). BHL (molecule 3). A three-nucleotide 3′ site bulge, a four base-pair helix and a loop containing the 5′ site. Pre-tRNAArcheuka and its variants (molecule 4). The hybrid pre-tRNA molecule pre-tRNAArcheuka is a substrate for both the eukaryal and archaeal endonucleases. It consists of two regions derived from yeast pre-tRNAPhe [nucleotides (nt) 1–31 and nt 38–76] joined by a 25 nt insert that corresponds to the BHB motif of the archaeal pre-tRNATrp. It has a typical eukaryal mature domain with cleavage sites located at the prescribed distance from the reference elements and a correctly-positioned A-I base pair, all of which should ensure correct recognition by the eukaryal endonuclease when the enzyme operates in the mature-domain dependent mode. In addition, the presence of the BHB motif confers substrate characteristics that are recognizable by the eukaryal enzyme when it operates in the mature-domain independent mode. (B) A substrate cleaved in both the mature-domain dependent and the mature domain independent modes. Products of digestion by the Xenopus tRNA splicing endonuclease. Molecule 1, pre-tRNAArcheuka 3bpΔas; molecule 2, pre-tRNAArcheuka 3bpΔas, C56G.

Recognition of pre-tRNAs by eukaryal tRNA splicing endonucleases normally requires the mature tRNA domain, as well as a base-pair, called the anticodon–intron (A-I) pair (Figure 1A, 1), which is formed between nucleotides in the anticodon loop and the intron (Baldi et al., 1992). The A-I pair must be at a fixed distance from the mature domain for cleavage to occur and cleavage near this base pair generates the 3′ splice site. An independent cleavage event, also at a fixed distance from the mature domain (usually at a purine), generates the 5′ splice site.

The two modes of substrate recognition are characterized by two distances. In the mature-domain independent mode the helix of the BHB sets the distance between the two bulges; in the mature-domain dependent mode the distance is fixed relative to reference in the mature domain.

While the subunit structures of the eukaryal and archaeal enzymes differ significantly (Trotta and Abelson, 1999), as do the superficial structures of the cleavage sites, we have demonstrated that both the Xenopus and yeast tRNA splicing endonucleases can operate in the mature-domain independent mode, characteristic of Archaea (Fabbri et al., 1998). The results reported in this paper explain why the eukaryal endonucleases retain the ability to operate in the mature-domain independent mode when their natural substrates do not have a BHB.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The artificial substrate pre-tRNAArcheuka contains both a mature domain and a BHB (Figure 1A, 2). The eukaryal enzymes cleave the substrate with a two base-pair insert in the anticodon stem, 2bp∇as (Figure 1A, 4), only in the mature-domain independent mode (Fabbri et al., 1998). The sites of cleavage by the eukaryal enzyme are fixed by recognition of local BHB structure rather than by reference to the mature domain.

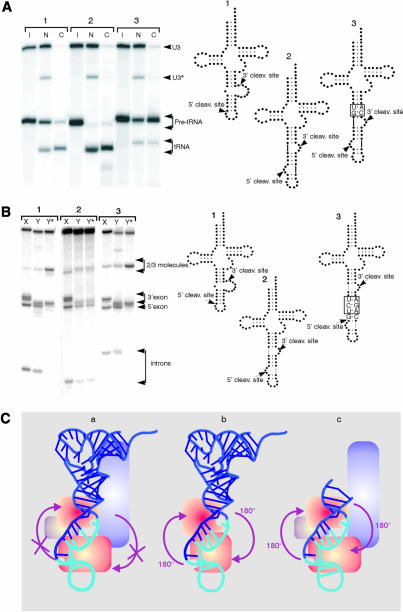

The Xenopus laevis endonuclease can also cleave in vivo in the mature-domain independent mode. When pre-tRNAArcheuka and pre-tRNAArcheuka 2bp∇as were injected into Xenopus oocyte nuclei, both substrates were spliced and ligated. The size of the mature tRNAArcheuka 2bp∇as, which is four bases longer than mature wild-type tRNAPhe, indicates that the Xenopus enzyme cleaves in the mature-domain independent mode in vivo just as it does in vitro (Figure 2A). The substantial amounts of each precursor exported before cleavage probably results from saturation of nuclear retention (Arts et al., 1998; Lund and Dahlberg, 1998).

Fig. 2. (A) The Xenopus endonuclease can cleave in vivo in the mature-domain independent mode. Low amounts of 32P-labeled RNAs corresponding to pre-tRNAPhe (1); pre-tRNAArcheuka (2) and pre-tRNAArcheuka2bp∇as (3) were injected into nuclei of Xenopus oocytes and 2 h later the intracellular distribution of the injected primary pre-tRNA transcripts and of the mature tRNAs were determined by analysis of total nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) RNAs. The injected precursor RNAs in the cytoplasm probably resulted from inefficient nuclear retention. I, input. (B) The yeast endonuclease mutant sen2-3 cleaves pre-tRNAArcheuka at both sites. Molecule 1, pre-tRNAPhe; molecule 2, pre-tRNAArcheuka; molecule 3, pre-tRNAArcheuka 3bp∇BHB, C8G, G24C. X, Xenopus laevis; Y, yeast S. cerevisiae wild type; Y* yeast S. cerevisiae sen2-3. The sen2-3 preparation was contaminated with a 3′ exonucleolytic activity that partially degraded the 3′ end of the precursor, reducing the size of the 3′ half product. The sequences of the products of the intron excision reaction have been verified by fingerprinting (data not shown). In the sen2-3 mutant, one residue in loop L7, Gly292, is changed to Glu (Trotta and Abelson, 1999). Loop 7 contains a histidine residue that is absolutely conserved in all tRNA endonucleases, and that probably acts as a general base by deprotonating the nucleophile 2′-hydroxyl group (Trotta and Abelson, 1999). The residues on loop 7 immediately surrounding the conserved histidine residue are not conserved among the tRNA endonucleases. We suggest that these residues have a role in the restructuring of the 5′ cleavage site in the eukaryal enzymes. (C) Comparison of models of enzyme-substrate interaction. (a) Pre-tRNAArcheuka Eukaryal enzyme (Trotta and Abelson, 1999). (b) Pre-tRNAArcheuka Archaeal enzyme (Trotta and Abelson, 1999). (c) BHB Eukaryal enzyme. A proposal for loss of symmetry during evolution of the intron excision reaction. In Archaea, the recognition element in pre-tRNA is the BHB, which has pseudo-two-fold symmetry (Diener and Moore, 1998; Trotta and Abelson, 1999). Since the endonuclease does not bind to the mature domain of pre-tRNA, the enzyme is oriented in such a way that both active sites can cleave either of the intron–exon junctions (b). The primary recognition element of the eukaryal endonuclease, on the other hand, is the asymmetrically located mature domain of pre-tRNA; interaction with that domain imposes an orientation of the enzyme on the substrate, so that each active site is specific to one or the other intron–exon junctions. In the absence of a mature domain, as with the mini-BHB (Fabbri et al., 1998), the eukaryal enzyme is free to recognize pseudo-two-fold symmetric elements in the substrate, so that both active sites in the enzyme can bind to either junction (c). However, when a substrate has both a mature domain and a symmetric BHB, as in pre-tRNAArcheuka, the eukaryal endonuclease can interact with the mature domain, and the added energy of this binding would be likely to orient the enzyme (a). We propose that during evolution, once endonucleases were able to recognize the mature domain, the need for a symmetric BHB recognition site diminished; however, the active sites of the eukaryal enzymes were maintained, allowing them to cleave pre-formed BHB structures. Because the orientation of the two cleavage sites in the enzyme remained constant, the eukaryal pre-tRNAs had to maintain the ability to form a BHB-like structure upon binding the eukaryal enzyme; part of that requirement is seen in the A-I base pairing rule and in the BHL.

Some substrates are cleaved in both modes. Pre-tRNAArcheuka 3bpΔas (Figure 1B), which has a three base-pair deletion in the anticodon stem, is cleaved in both modes. In this case, the two modes yield distinct product sizes, and both are observed. Two introns are visible in Figure 1B, lane 1. One of the products is not produced in the C56G mutant reflecting the inability of the enzyme to cleave a substrate that cannot form a normal mature domain in the mature-domain dependent mode.

We now propose that the orientation of the substrate in the active site of the eukaryal enzyme requires the formation of a structure that resembles a BHB; the A-I pair would play a pivotal role in this process, as it represents the closing base pair of one of the bulges. This model predicts that recognition of the mature tRNA domain by a eukaryal tRNA splicing endonuclease allows subsequent formation of a BHB-like cleavage structure.

In addition to the A-I pair (Baldi et al., 1992), other relics of the archaeal world provide insight into the mechanism of the eukaryal cleavage reaction. Some eukaryal pre-tRNAs present motifs that resemble the BHB. The sequence of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome shows that tRNA genes corresponding to three isoacceptor species (Leu, Tyr, Ile) contain introns (The C.elegans Sequencing Consortium, 1998). The nematode pre-tRNAs present a motif which we call BHL (Figure 1A, 3), which resembles the BHB in that it has the 3′ site bulge and the four base-pair helix but the 5′ site is in a loop rather than in bulge. These three intron-containing pre-tRNAs of C. elegans are cleaved correctly by both yeast and Xenopus endonucleases, as well as the Parascaris equorum tRNA splicing endonuclease, but not by the archaeal enzyme (data not shown). Thus, the only truly universal substrate is an RNA with a BHB (Fabbri et al., 1998).

Because they can both cleave the BHB, the archaeal and eukaryal endonucleases are likely to have identical dispositions of active sites, a feature conserved since their divergence from a common ancestor (Trotta and Abelson, 1999; Fabbri et al., 1998) (Figure 2C). We suggest that the mature-domain dependent mode arose through specialization of the subunits of the eukaryal enzyme.

We propose that the eukaryal enzymes possess a mature-domain dependent 5′ site restructuring activity (Di Nicola et al., 1997). Such an activity would be required for the last steps of substrate recognition by the eukaryal enzymes, recapitulating the recognition process of their archaeal counterparts. The 5′ site restructuring activity is not needed to cleave the BHB because it already has a correctly structured 5′ site; however, the activity is responsible for improving the efficiency of cleavage at the 5′ site in BHL (P. Fruscoloni, M. Zamboni, M.I. Baldi and G.P. Tocchini-Valentini, manuscript in preparation). The Ascaris enzyme also has a mature-domain dependent 5′ restructuring activity, but it differs from that of Xenopus because it is unable to restructure a typical eukaryal pre-tRNA such as yeast pre-tRNAPhe (P. Fruscoloni, M. Zamboni, M.I. Baldi and G.P. Tocchini-Valentini manuscript in preparation).

Our model predicts the existence of mutants of the eukaryal enzyme that lack the 5′ restructuring activity. Such mutants would be unable to cleave a eukaryal pre-tRNA at the 5′ site, but could cleave at the 3′ site. More importantly, these restructuring mutants should cleave precursors that already have a BHB.

The yeast endonuclease is an αβγδ heterotetramer (Trotta et al., 1997). Homology relationships and other evidence suggest that two subunits of the enzyme, Sen2p and Sen34p, contain distinct active sites, one for the 5′ site, the other for the 3′ site. The mutant sen2-3 is defective in cleavage of the 5′ site (Ho et al., 1990); Figure 2B shows that sen2-3 extracts cleaves the 3′ but not the 5′ site of yeast pre-tRNAPhe. The same extract, however, cleaves pre-tRNAArcheuka at both sites (Figure 2B). Thus, sen2-3 cleaves the 3′ but not the 5′ sites in substrates lacking a BHB, as would be expected if it lacked the mature-domain dependent 5′ site restructuring activity. This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that pre-tRNAArcheuka 3bp ∇BHB, a substrate that can interact with the enzyme only in the mature-domain dependent mode, is cleaved only at the 3′ site (Figure 2B).

It is unlikely that the lack of cleavage at the 5′ site of pre-tRNAPhe results simply from inactivation of the catalytic site since the mutated amino acid is not near this site, based on the crystal structure of the enzyme (Li et al., 1998). Moreover, pre-tRNAArcheuka, which has a BHB, is cleaved at both sites even though its mature domain should prevent binding of the sen34 active site to the 5′ site (Figure 2B). Unfortunately, expression of a sen2-3 and sen34 double mutant enzyme is very likely to be lethal, making production of a doubly mutated enzyme impossible.

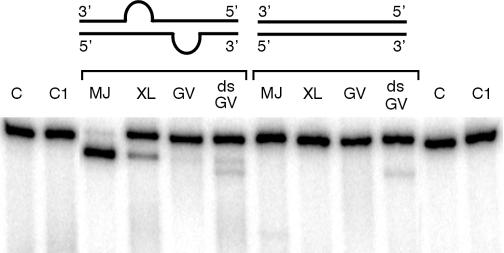

The ability of the eukaryal enzyme to recognize and cleave independently of the mature domain creates the possibility for cleavage of non-tRNA substrates (Figure 3). If the eukaryal endonuclease can recognize and cleave substrates in the mature-domain independent mode, any RNA that contains a BHB structure should be able to serve as a substrate. Such a target could be generated in mRNA by adding a suitable RNA oligonucletide.

Fig. 3. Cleavage of a non-tRNA molecule by the Xenopus endonuclease. Profilin I mRNA duplexes (cartoon) consisting of 32P-labeled sense strand and cold antisense strand (0.6 nM) were incubated with Methanococcus jannaschii endonuclease (MJ for 30 min at 65°C); Xenopus laevis endonuclease (XL for 90 min at 25°C); germinal vesicles extract (GV for 90 min at 25°C). The reacted RNA was treated as described (Mattoccia et al., 1988; Baldi et al., 1992; Fabbri et al., 1998) and analyzed in 8M urea polyacrylamide gels. Two fragments are generated from profilin I mRNA (417 nts and 53 nts). The gel shows only the larger fragment. Unrelated 32P-labeled dsRNA (low specific activity) was added where indicated (the concentration was 300× that of the profilin I duplex). C, duplex containing the BHB; C1, full duplex.

Figure 3 shows that the archaeal and eukaryal enzymes cleave mouse profilin 1 mRNA (Widada et al., 1989), when the RNA is complexed with another oligoribonucleotide forming a BHB. This cleavage occurs in a BHB-dependent manner because fully double-stranded molecules (Figure 3) and molecules presenting an insertion of three base pairs in the helix of the BHB are not cleaved (data not shown). Figure 3 shows that cleavage also occurs in extracts of germinal vesicles (GV extracts). Again, cleavage is BHB-dependent. However, cleavage in this extract occurred only in the presence of a 100-fold excess of unrelated double stranded RNA (dsRNA). Pre-tRNAArcheuka, on the contrary, is cleaved at high efficiency (data not shown). An explanation for these differences is the presence in GV extracts of adenosine deaminases (ADARs) that convert adenosines to inosines within dsRNA (Bass and Weintraub, 1988), thereby causing the RNA duplex to fall apart, disrupting the BHB structure. Presumably, at low concentration of dsRNA, ADARs deaminate the substrate and, as a result of the increased single-stranded character of the molecule, the BHB is destroyed.

Our results indicate that the formation of a BHB is an obligate step in cleavage by the eukaryal endonucleases and explain why the eukaryal endonucleases retain the ability to operate in the mature-domain independent mode when their natural substrates do not have a BHB.

METHODS

Pre-tRNAs were synthesized as described (Mattoccia et al., 1988; Baldi et al., 1992; Fabbri et al.,1998). Templates for the synthesis of the profilin I mRNA molecules were constructed by PCR. The PCR templates were the full-length molecules. One primer contained the T7 promoter. Conditions for PCR, transcription by T7 RNA polymerase, and endonuclease assays were as described (Mattoccia et al., 1988; Baldi et al., 1992; Fabbri et al., 1998). Duplex RNAs were prepared as described (Bass and Weintraub, 1988).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to E. Mattoccia for continuous discussion and help with the figures. We thank J. Dahlberg for continuous encouragement and help with the manuscript; W. Witke for mouse profilin I cDNA; R. Haselkorn for critical reading of the manuscript, G. Deidda for help with the PCR and J. Abelson for the sen2-3 mutant. We thank A. Sebastiano for secretarial assistance, and G. Di Franco for technical assistance. Financial support was provided by: EC Contract BIO4-98-0189; Progetto Finalizzato ‘Biotecnologie’ (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche); Programma Biotecnologie MURST-CNR Legge 95/95 5%; Programma Biomolecole per la Salute Umana MURST-CNR Legge 95/95 5%; Progetto Strategico ‘Basi Fondamentali della Post Genomica’ (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche).

REFERENCES

- Arts G.-J., Kuersten, S., Romby, P., Ehresmann, B. and Mattaj, I.W. (1998) The role of exportin-t in selective nuclear export of mature tRNAs. EMBO J., 17, 7430–7441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi M.I., Mattoccia, E., Bufardeci, E., Fabbri, S. and Tocchini-Valentini, G.P. (1992) Participation of the intron in the reaction catalyzed by the Xenopus tRNA splicing endonuclease. Science, 255, 1404–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass B.L. and Weintraub, H. (1988) An unwinding activity that covalently modifies its double-stranded RNA substrate. Cell, 55, 1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfort M. and Weiner, A. (1997) Another bridge between kingdoms: tRNA splicing in Archaea and Eukaryotes. Cell, 89, 1003–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels C.J., Gupta, R. and Doolittle, W.F. (1985) Transcription and excision of a large intron in the tRNA Trp gene of an archaebacterium, Halobacterium volcanii.J. Biol. Chem., 260, 3132–3134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nicola E. et al. (1997) The eucaryal tRNA splicing endonuclease recognizes a tripartite set of RNA elements. Cell, 89, 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener J.L. and Moore, P.B. (1998) Solution structure of a substrate for the archaeal pre-tRNA splicing endonucleases: The bulge-helix-bulge motif. Mol. Cell, 1, 883–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri S. et al. (1998) Conservation of substrate recognition mechanisms by tRNA splicing endonucleases. Science, 280, 284–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.K., Rauhut, R., Vijayraghavan, U. and Abelson, J. (1990) Accumulation of pre-tRNA splicing ‘2/3’ intermediates in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant. EMBO J., 9, 1245–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Trotta, C.R. and Abelson, J.N. (1998) Crystal structure and evolution of a transfer RNA splicing enzyme. Science, 280, 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E. and Dahlberg, J.E. (1998) Proofreading and aminoacylation of tRNAs before export from the nucleus. Science, 282, 2082–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoccia E., Baldi, M I., Gandini Attardi, D., Ciafrè, S. and Tocchini-Valentini, G.P. (1988) Site selection by the tRNA splicing endonuclease of Xenopus laevis. Cell, 55, 731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes V.M. and Abelson, J. (1988) Substrate recognition and splice site determination in yeast tRNA splicing. Cell, 55, 719–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium (1998) Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science, 282, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta C.R. and Abelson, J. (1999) tRNA splicing: An RNA world add-on or an ancient reaction? In Gesteland, R.F., Cech, T.M., Atkins, J.F. (eds), The RNA World. 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 561–583.

- Trotta C.R. et al. (1997) The yeast tRNA splicing endonuclease: A tetrameric enzyme with two active site subunits homologous to the archaeal tRNA endonucleases. Cell, 89, 849–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widada J.S., Ferraz, C. and Liautard, J.P. (1989) Total coding sequence of profilin cDNA from Mus musculus macrophage. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]